1. Introduction

Motion is a fundamental quality of sensory input. In vision, despite diverse evolutionary trajectories across different species, from insects and cephalopods to vertebrates, visual systems have converged on fundamentally similar mechanisms of motion processing [

1,

2]. However, motion is not exclusive to vision; it is also a hallmark the tactile sensory system, with considerable behavioural relevance for both animals and humans. Everyday interactions such as object manipulation and haptic exploration involve relative motion between the skin and surfaces [

3]. For example, discerning roughness and smoothness, identifying material properties (e.g. metal vs. wood) or recognising object shapes requires dynamic contact through palpation and movement. Reading Braille depends on lateral movement of the fingertips to interpret sequences of raised dots. Tactile motion processing underpins fine motor control and precise object manipulation [

4,

5]. Yet, the perceptual and computational mechanisms underlying tactile motion remain incompletely understood.

Two principal sources of information for tactile motion have been identified in the literature [

5,

6]. The first relies on the sequential activation of mechanoreceptors at different skin locations as an object or stimulus moves across the skin – such as when an insect crawls along the arm. This includes apparent tactile motion, typically studied experimentally using discrete, pulsed stimuli delivered in succession to separate skin sites[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The second source involves skin deformation cues, particularly shear and stretch, which arise during sliding contact or friction. These deformations can convey directional information [

15], potentially through recruitment of distinct afferent populations, such as slowly adapting type II (SA2) units, which are sensitive to stretch and contribute to motion direction perception [

16].

At the level of periphery, slowly adapting type I (SA1) afferents convey high-resolution spatial information about contact location [

4,

17,

18]. The spatiotemporal pattern of their population activity is thought to encode motion direction and speed with acuity comparable to human perceptual performance [

18]. Rapidly adapting type I (RA1) afferents may also contribute to motion encoding via spatiotemporal patterns, though with lower spatial precision due to their larger receptive fields [

18]. SA2 afferents, previously mentioned, respond to skin stretch and support motion direction perception through their tuning to deformation patterns [

15,

16].

Here, I investigate a third and less explored mechanism for tactile motion: the perception of motion across fingers induced by asynchronous, continuous streams of vibrotactile input delivered to two fingertips simultaneously. Unlike prior studies that typically rely on either (a) sequential, pulsed stimulations delivered to multiple discrete skin sites [

7,

9,

11,

14,

19], or (b) physical sliding stimuli that engage friction-induced skin deformation [

5,

6], this paradigm involves two spatially fixed but temporally dynamic inputs. The stimulation does not involve skin movement or high spatial acuity, but rather evokes motion percepts through temporal phase differences between inputs to two fingerpads.

Fingertips are among the most densely innervated tactile regions in mammalian and human body [

20], and are primary organs for active exploration [

3]. This work uses continuous amplitude-modulated vibrations known to predominantly recruit rapidly adapting type II (RA2) afferents – i.e., Pacinian corpuscles – which are sensitive to high-frequency vibratory energy and exhibit large receptive fields [

21,

22,

23]. Unlike SA1 and RA1 afferents, RA2 units are less sensitive to fine spatial features but can detect remote vibratory events across skin and even bone. Notably, the stimuli here are delivered over the entire fingertip pad, eliminating reliance on fine spatial localisation and instead leveraging temporal synchrony or asynchrony across digits. This approach is analogous in principle to mechanisms found in certain arthropods, such as chelicerates, which detect and localise remote vibratory sources using their paired appendages [

24]. Similarly, humans may infer motion direction or location of a remote source by comparing asynchronous vibratory input across fingerpads [

25] – effectively extending tactile spatial perception beyond the point of contact.

In this study, I first formalise the physical basis for detecting the location and direction of a remotely moving vibration source, and how such stimuli can be simulated through asynchronous amplitude-modulated input to two fingertips. I then present a series of psychophysical experiments characterising human perceptual performance in detecting the direction of such inferred motion, revealing a novel mode of tactile motion perception that operates independently of spatial acuity or physical surface movement.

2. Materials and Methods

Vibrotactile stimulation is a versatile method for conveying spatiotemporal information through the skin and has been widely employed in both fundamental research and haptic technology applications [

26]. Arrays of tactors delivering temporally staggered pulses have been used to generate apparent motion across body surfaces such as between hands, along the arm, or across the back, simulating a moving tactile stimulus without physical displacement [

8,

12,

19,

26,

27]. While such paradigms rely on discrete bursts or pulses with differences in stimulus onset timing across spatially distinct sites to evoke motion percepts, the current study employs continuous amplitude-modulated waveforms with controlled phase offsets, enabling investigation of motion perception from contentious, distributed, phase-coded signals in the absence of distinct onsets or spatial displacement.

To model the stimuli generated by a remotely vibrating source, such as a mobile phone on a table, we consider a point source emitting a sinusoidal carrier wave

, where

and

denote the amplitude and carrier frequency of vibration, respectively. As this vibration propagates through the substrate – e.g., the table – approximately as a plane wave, it undergoes attenuation due to dissipation, scattering, and absorption. This attenuation typically follows an exponential decay with distance:

where

is the attenuation coefficient (dependent on medium properties and frequency), and

d is the distance from the source.

When the source moves relative to a fixed point, the amplitude at that point changes with time due to the variation in distance. These changes are proportional to the radial component of the source’s motion. In the special case of periodic movement at a frequency

, the received signal envelope at a fixed remote point with time-varying distance

is itself periodic, and the received signal can be written as:

where

is the delay due to propagation over distance

, and

is the Doppler shift caused by the source’s motion. Both parameters

and

depend on the wave propagation speed in the medium, which is determined by its stiffness and density (e.g., ∼5790 ms

-1 in stainless steel, and ∼3960 ms

-1 in hard wood).

For distances on the order of a meter or less, corresponds to sub-millisecond or nanosecond delays, well below biologically plausible detection thresholds. Moreover, assuming slow motion of source relative to wave propagation speed, and , the Doppler shift is negligible. Henceforth, I assume and .

2.1. Motion Direction Estimation via Two Touch Points

When a sensor (e.g., a fingertip) is placed at a fixed point (hereafter a ‘touch point’), the direction of source movement along the radial axis (toward or away from the touch point) can be inferred from temporal changes in the vibration envelope. However, a single touch point provides no information about the tangential component of the motion. To recover trajectory information, at least two touch points positioned at distinct spatial locations are required (

Figure 1).

Let

and

denote two such points. The envelopes of vibration received at these two locations can, in principle, be used to infer the moment-by-moment position of a moving source in 2D. However, the reconstruction is ambiguous: any trajectory and its mirror reflection across the line connecting the two touch points (the touch-point axis) yields identical vibration patterns. This is illustrated in

Figure 1A.

In 3D, ambiguity increases: all trajectories that are rotationally symmetric around the touch-point axis produce indistinguishable vibration profiles at the two points. That is, any trajectory that can be rotated about this axis into another remains perceptually equivalent at the touch points, leading to infinite number of trajectories that create an identical vibration pattern at the two touch points and .

2.1.1. In-Phase Vibrations

As discussed, a periodic source movement with frequency

f results in a periodic amplitude modulation at each touch point. If the envelopes at

and

vary together over time – i.e., they are monotonic transformations of one another under a strictly increasing odd function – they are said to be ‘in phase’. For example, consider a trajectory confined to a plane perpendicular to the touch-point axis (

Figure 1B). The closest and farthest positions on the trajectory to

are identical to those to

. Let

denote the instantaneous orthogonal distance from the touch-point axis to the source trajectory at any moment

t, and let

be the perpendicular distance from touch point

to the plane of the trajectory. The amplitude at each touch point is given by:

and the derivative:

This shows that the envelope at each touch point changes in the same direction (increasing or decreasing together), confirming they are in phase. Additionally, one can show:

which is a strictly increasing function of

, again confirming phase alignment.

2.1.2. Anti-Phase Vibrations

Two waveforms are

anti-phase if their envelopes exhibit a phase difference of

, such that when one increases, the other decreases. This occurs when the envelopes are related through a negatively proportional transformation under a strictly increasing odd function. In this case, the perceived direction of motion alternates across each half-cycle, creating a bouncing or bidirectional trajectory. Perceptually, such out-of-phase vibration patterns may give rise to

bistable motion perception, wherein the ambiguous temporal dynamics support two competing interpretations, each of which corresponding to motion in opposite directions, that may alternate spontaneously over time. Examples of out-of-phase configurations are shown in

Figure 1D and E.

2.2. Circular Motion of a Vibrating Source

Consider a point source moving along a circular trajectory with radius

and constant tangential velocity

v (

Figure 1C). The frequency of motion is

Let

T be a touch point located at polar coordinates

relative to the centre of the circular path

O. The received vibration at time

t is given by:

where

is the source amplitude,

is the carrier frequency, and

is the attenuation coefficient of the medium. The

envelope of the received vibration is the time-varying function:

which oscillates at frequency

f, between a minimum of

and a maximum of

.

Extension to 3D:

In three dimensions, the equation for the received signal becomes:

where

is the elevation of the touch point

T relative to the trajectory plane denoted by

P, and

is the inclination angle in spherical coordinates (

Figure 1C).

Phase Differences from Geometry

Let

P denote the plane of circular trajectory, centred at

O. Consider two touch points,

and

, with projections

and

onto plane

P. Without loss of generality, let the coordinates of the two touch points be

and

, respectively. According to Eq.

9, the received vibrations at the two touch points are:

Thus, the envelope phase difference between the two points is

.

Assume that the projected points and the centre of the circular path

O lie on a straight line (

Figure 1D). Then, if

O lies

between and

(i.e.,

) the envelopes of the vibrations are

anti-phase (

Figure 1D and E). Conversely, if

O lies

outside the segment connecting

– i.e.,

,– the envelopes are

in phase.

For simplicity, hereafter, we focus on the 2D symmetric case where the centre of the circular trajectory lies on the perpendicular bisector of the segment connecting the two touch points and , such that . In this configuration, the two touch points are equidistant from the centre, resulting in envelopes of vibration with equal amplitude range. This condition facilitates visualisation and analysis of in-phase and out-of-phase conditions in a two-dimensional geometry.

2.3. Experimental Procedure

Three psychophysical experiments were conducted to investigate vibrotactile motion direction discrimination using a common two-alternative forced-choice (2-AFC) discrete trial paradigm. In this experiment, participants reported the perceived direction of vibro-tactile motion (left vs. right) generated by two amplitude-modulated vibrations delivered simultaneously to the index and middle fingertips of the right hand (see details below). All experimental procedures were approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC) and conducted in accordance with approved guidelines.

2.3.1. Participants

A total of 26 participants (12 female, age range: 19–34, 1 left-handed) took part across the three experiments. All were undergraduate or graduate students at Monash University. Each experiment involved distinct participant groups. All participants provided written informed consent prior to the experiment.

2.3.2. Vibro-Tactile Stimulation

In all experiments, vibrotactile stimuli were delivered simultaneously to the index and middle fingertips of the right hand using two miniature solenoid transducers (PMT-20N12AL04-04, Tymphany HK Ltd; 4 Ω, 1 W, 20 mm diameter) mounted 5 cm apart on a vibration-isolated pad. Stimuli were generated in MATLAB (MathWorks Inc.) at a sampling rate of either 48 kHz or 192 kHz, and output through a Creative Sound Blaster Audigy Fx 5.1 sound card (model SB1570). The peak-to-peak amplitude of the output waveform was set to 1.98 V. The shape and curvature of the transducer matched the size and contour of adult fingertips [

28]. The base (carrier) frequency of the vibrations was

. Although this frequency is within the audible range, we verified during pilot testing that the stimuli were not audible to participants and could only be perceived via touch. Amplitude modulation (AM) was applied to generate low-frequency envelopes, with each trial containing 3 modulation cycles. The modulation amplitude was set well above detection threshold, and pilot testing confirmed that even halving the amplitude had negligible effects on performance in the motion discrimination task.

In all experiments, sinusoidal envelopes were used due to their mathematical and physical properties. Sinusoids are fundamental in Fourier decomposition and are the only waveforms that preserve their shape under summation with others of the same frequency. Sinusoidal modulation mimics natural oscillatory signals (e.g., wind, light, and sound waves) and implies motion with varying velocity, similar to pendular or spring-mass dynamics.

For a given phase difference

, the two sinusoidally modulated vibrations were defined as:

To avoid any response bias or cues about motion direction arising from differences in initial envelope amplitude, vibration onset was set to one of the two isoamplitude points where the envelopes were identical. For non-zero

, these occur at

and

, with the corresponding envelope amplitudes of

and

, respectively (

Figure 2C). Since cosine is an even function, the envelope magnitudes are identical for

and

. At each of these onset points, the envelopes have opposite slopes – one rising and the other falling – corresponding to opposite directions of motion along the circular trajectory. On each trial, one of these two onset points was selected at random with equal probability, ensuring that initial envelope phase provided no reliable cue about motion direction.

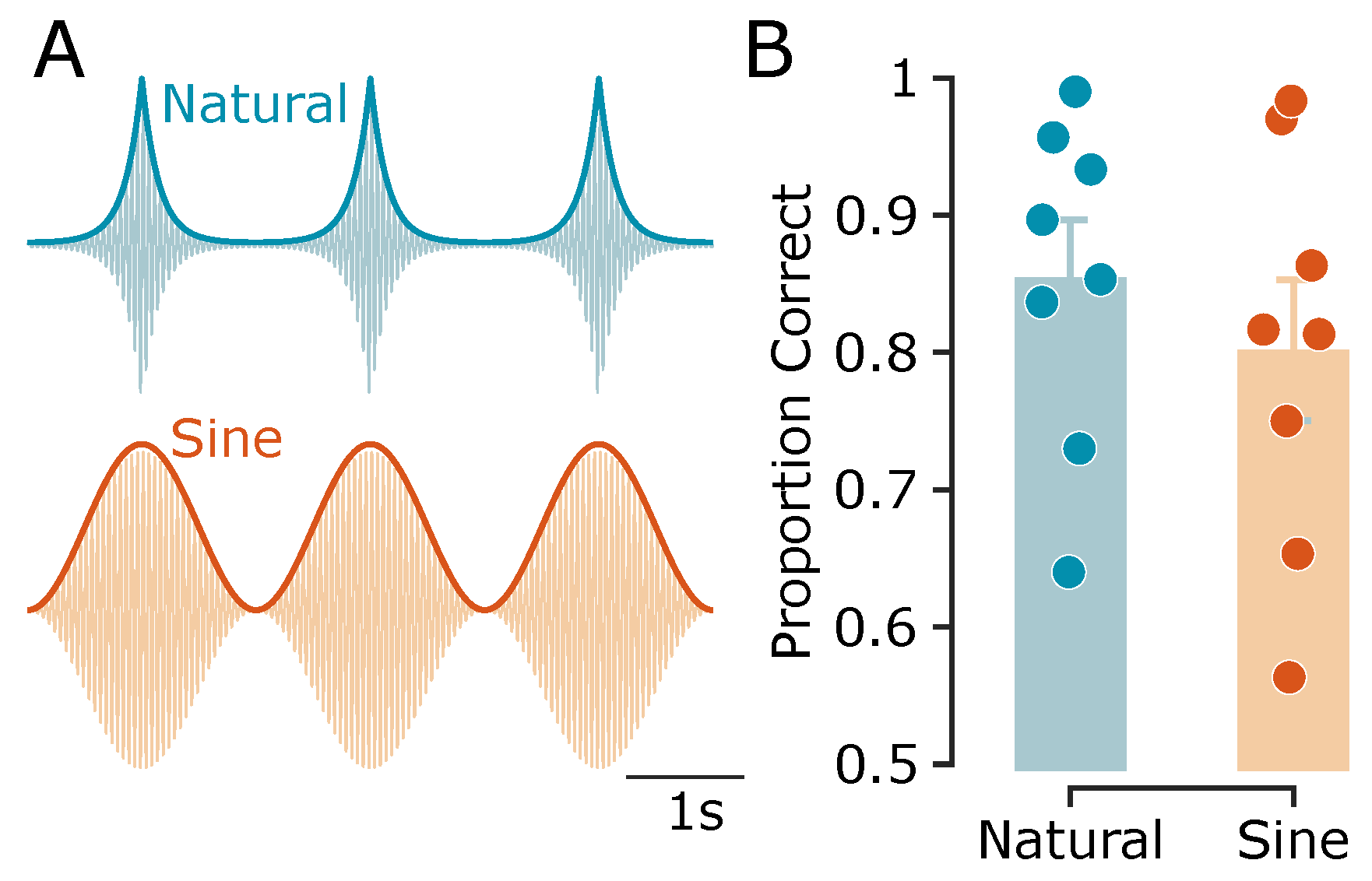

In Experiment 1, we additionally included stimuli with exponentially decaying envelopes to simulate more realistic, physically plausible patterns of vibration propagation. The envelopes were derived from Eq.

10, using fixed parameters

, and

:

These stimuli were also initiated at one of the two isoamplitude points selected randomly on each trial, consistent with the sinusoidal condition.

2.4. Motion Direction Discrimination Task

Participants performed a discrete-trial two alternative forced-choice (2-AFC) task to judge the perceived direction of vibrotactile motion. On each trial, two amplitude-modulated vibrations were delivered simultaneously to the index and middle fingertips of the right hand. Participants were instructed to gently rest their fingertips on the transducers without applying force (

Figure 2). The two transducers were spaced 5 cm apart on a vibration-isolated pad, arranged such that vibrations from one transducer were not perceptible at the other. Participants rested their arm on the chair armrest with their wrist comfortably supported on a padded surface aligned with the stimulation platform. They were instructed to maintain a stable hand posture throughout each session. All participants reported clear perception of the envelope modulation, and pilot testing confirmed that the stimulus amplitude was well above detection threshold.

The task was self-paced, with all responses made via keyboard. On each trial, a pair of vibrations with a specific envelope phase difference was presented for three cycles (e.g., 6 s at an envelope frequency of 0.5 Hz). Participants reported the perceived motion direction (leftward or rightward) by pressing the corresponding arrow key with their left hand. There was no time limit for responses, and participants could respond at any moment during or after stimulation.

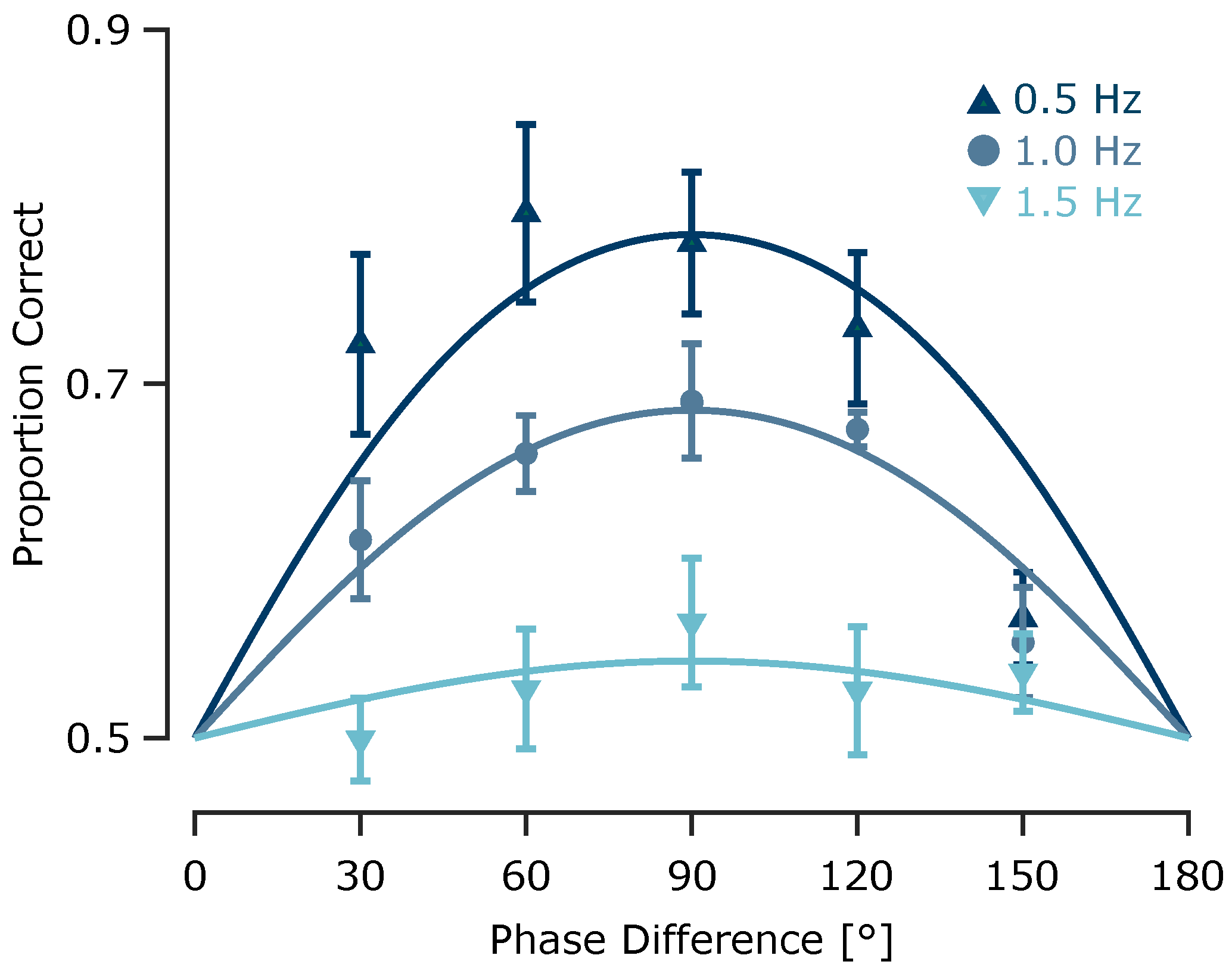

The specific phase differences and envelope modulation frequencies varied across the three experiments. In Experiment 1, we compared sinusoidal and exponential envelopes with phase differences of ±30°to ±150°(30° increments) at a fixed envelope frequency of 0.5 Hz. In Experiment 2, sinusoidal envelopes were used with phase differences ranging from -180° to 180° in 30°increments, tested at envelope frequencies of 0.5, 1, and 1.5 Hz. In Experiment 3, sinusoidal envelopes were tested at phase differences of 0°, ±30°, ±60°, ±90°, and 180° at a fixed frequency of 0.5 Hz, with participants additionally providing confidence ratings after each response by pressing a number key from “1” (no confidence) to “5” (absolute certainty). These ratings were linearly scaled to a 0–100% confidence range. Experimental conditions were presented in pseudo-random order across trials, with approximately 30 repetitions per condition.

2.5. Psychometric Modelling

To quantify sensitivity to phase differences at each modulation frequency, we modelled perceptual discrimination performance as a function of phase difference

using a nonlinear periodic-sigmoid psychometric function:

where

denotes the predicted proportion of correct responses at a given phase difference

, and

is a sensitivity parameter reflecting the steepness of the psychometric function. Higher

values indicate greater sensitivity to phase differences. This model captures the periodic geometry of the stimulus, predicting chance-level performance (

) at 0° and 180°, where the vibrations provide no directional cue. The sinusoidal form, combined with its single-parameter structure, avoids overfitting and reflects the hypothetised mechanism of motion perception based on phase-difference readout across spatially separated tactile sensors. The model was fit to group-averaged accuracy data using nonlinear least-squares regression, and the model performance (goodness-of-fit) was assessed using the coefficient of determination (

).

2.6. Probabilistic Model of Temporal Reference Detection and Cycle Disambiguation

Consider two AM vibrations wth phase difference

, which corresponds to a temporal lag

d between their envelopes:

where

f is the envelope modulation frequency. Let

and

denote the perceived moments of two consecutive salient reference points (e.g., peaks) of vibration 1, and let

denote the corresponding reference point of vibration 2 that occurs between

and

. These reference points are extracted from the envelopes of the amplitude-modulated vibrations. Hereafter, we focus on peak features, but the same logic applies to other amplitude landmarks (e.g., troughs or zero-crossings). Due to sensory noise and perceptual limits, each detected peak is assumed to lie within a temporal uncertainty window around the true peak time. For each reference point, I model the perceived time as being uniformly distributed within a window of width

w centred at the true peak. This uncertainty window depends on the perceptual threshold with which the envelope is extracted. For instance, assuming a sinusoidal envelope in Eq.

11, the time intervals where the envelope deviates from the peak amplitude by less than a threshold value

correspond to durations satisfying

, which implies:

so that the total uncertainty window is:

Since the vibrations are periodic and have identical envelope shapes (with vibration 2 being a phase-shifted version of vibration 1), the reference point of vibration 2 is shifted by lag d. Similarly, is one cycle after , i.e., with an offset of T, where is the envelope modulation period. Without loss of generality, we assume , and align the reference points relative to zero and define their distributions as , and . Correct perception of motion direction depends on both (1) the reliability of judging the temporal order of salient reference points (e.g., peaks) and (2) disambiguation of within-cycle versus across-cycle intervals. For now, we focus on peak features, but the same logic applies to other amplitude landmarks (e.g., troughs or zero-crossings).

Based on these distributions, the two forms of perceptual inference are required to judge motion direction: first, the temporal order judgement, i.e. determining whether the peak of vibration 2 occurs after the peak of vibration 1 (). Second, the inter-peak interval discrimination, i.e., comparing whether the interval between and is shorter than the interval between and , i.e., testing whether .

The sections that follow formalise these probabilities and derive an analytical expression for the overall probability of a correct motion direction judgement.

2.6.1. Temporal Order Judgement

The first source of error arises from uncertainty in judging the temporal order of peaks. If the temporal lag

dis smaller than the uncertainty window

w, the perceived ordering of

and

may be incorrect. The probability that the peak of envelope 1 is perceived before that of envelope 2 (i.e., a correct temporal order judgement) is given by the integral of the joint distribution of

and

over the area

:

As

and

are mutually independent with uniform distributions,

is distributed triangularly over the interval

, yielding:

The case

guarantees correct order due to non-overlapping supports.

2.6.2. Across-Cycle Ambiguity and Inter-Peak Interval Discrimination

As

d increases and the uncertainty window extends into the next modulation cycle, another form of error emerges. This is when the uncertainty around

extends beyond the halfway point of the modulation period

T, the perceived peak of envelope 2 may fall closer in time to the

next peak of envelope 1 (denoted

) rather than the original one at

. This may result in an incorrect interval comparison, i.e.,

, thus misjudging the motion direction. Based on the mutually independent uniform distributions of

,

and

, the probability density function of

is a piece-wise quadratic function of the form:

The probability of avoiding this across-cycle confusion is:

. The probability is below 1 when

.

2.6.3. Joint Probability of Correct Motion Perception

Correct motion perception requires both correct temporal order identification of peaks, and correct across-cycle inter-peak interval discrimination. These two conditions are not independent, and their joint probability must be calculated conditionally. Let

. The joint probability of a correct response is:

Using the law of total probability over the distribution of

, the second term can be rewritten as:

where

is the conditional probability density function of

given

, defined as:

with

denoting the triangular probability density function of

, and the normalisation constant

as derived in Eq.

15. Thus, the joint probability becomes:

The conditioned probability

can be expressed as:

where

is the distribution of the difference between

and

, given

. The conditional distribution

, where:

so that the support length is

, at most

w. This leads to a trapezoidal distribution for

, from which we derive the cumulative probability:

The total probability of a correct decision is obtained by substituting this into Eq.

18. The full expression combines a triangular distribution for

, a trapezoidal distribution for

, and a conditional integration over all valid

. Though based on simple assumptions, this model predicts a non-linear psychometric curve that captures key features observed in our data, including asymmetries in performance consistent (e.g., better performance at 30° than at 150° phase lags in Experiment 2).

4. Conclusions

This study investigated how the tactile system extracts spatial information about object motion from temporally structured vibrations delivered to two fingertips. Across three experiments, I delivered pairs of amplitude-modulated vibrations – each comprising a 100 Hz carrier modulated by a low-frequency sinusoidal envelope – to simulate continuous tactile motion. By systematically varying the phase difference between the two envelopes, I quantified how inter-fingertip phase offsets influence perceived motion direction, response latency, and confidence.

Our findings confirmed that the direction of perceived motion is determined by the phase difference between the two vibrations and not by their absolute frequency or amplitude. Experiment 1 showed that sinusoidal envelope vibrations reliably elicited robust directional motion percepts, comparable to those evoked by natural patterns (e.g., exponential decay). Notably, [

12] found that gradually ramped vibrotactile stimuli produced stronger and smoother motion percepts than abrupt onsets, consistent with the use of continuous amplitude modulated vibrations in the present study to simulate naturalistic motion cues. Experiment 2 established that the upper frequency limit for reliable tactile motion discrimination lies below 1.5 Hz, nearly ten fold higher frequency threshold than those reported in earlier studies using similar stimuli [

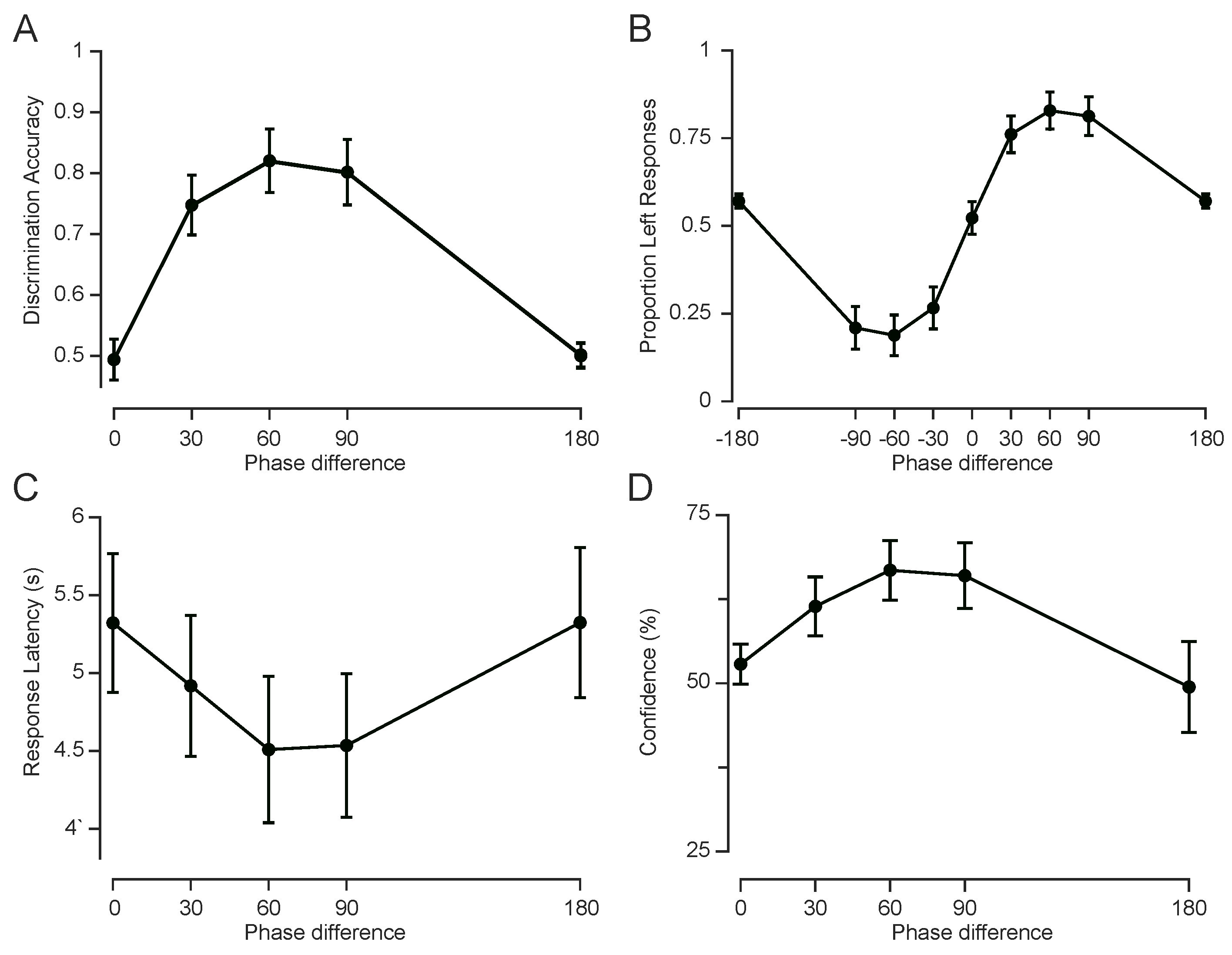

25]. Experiment 3 revealed systematic changes in confidence and reaction time with phase difference, with ambiguous conditions (0° and 180°) producing slower responses and lower confidence ratings. Importantly, although the 180° condition, despite producing the largest moment-by-moment amplitude differences between fingers, did not yield a consistent percept of direction, suggesting that motion perception depends on phase differences, not amplitude disparity.

Together, these results provide new insight into the computational basis of tactile motion perception. They support a mechanism in which tactile motion perception arises from the relative

phase differences between of temporally structured signals across skin locations, rather than from instantaneous amplitude differences or ‘energy shifts. Unlike prior studies of tactile synchrony detection, the present paradigm required spatial trajectory inference across inputs, revealing that

phase-based temporal integration, rather than amplitude contrast, underpins tactile motion perception. While Kuroki et al. [

25] demonstrated that humans can detect temporal asynchrony in AM tactile stimuli at higher modulation frequencies (up to 20 Hz) indicative of sensitivity to temporal structure, their task probed asynchrony detection, not motion inference. Drawing parallels to the visual system, they proposed that tactile perception may rely on both “phase-shift” and “energy-shift” mechanisms, analogous to first- and second-order motion processing in vision.

Notably, Kuroki et. al reported peak detection at a 180° phase difference. Yet in the current study, the same phase difference produced ambiguous motion percepts, reflected in lower confidence, slower responses, and inconsistent choices. This discrepancy likely reflects task-specific neural computations for synchrony detection and motion perception. Synchrony detection may rely on local temporal contrast or energy cues at single skin locations, whereas tactile motion perception requires spatial comparison and temporal integration across fingertips. The present results suggest that phase-based readout, rather than local amplitude difference, is central to tactile motion perception.

This dissociation highlights that motion perception depends on the integration of temporal phase relationships across space and time. As in the visual system, where distinct pathways support multiple forms of motion processing, the tactile system may also engage parallel mechanisms for temporal analysis. Phase-based computations appear specifically tuned for inferring motion trajectories, distinguishing them from those supporting synchrony detection. These findings reveal how the tactile system transforms temporally structured input into spatial motion percepts, and how the brain selectively engages distinct temporal codes based on perceptual goals.

Here, I proposed two complementary models of tactile motion perception; one based on global cross-correlation of vibration envelopes, and another relying on local temporal comparisons between salient features such as envelope peaks. While the cross-correlation model captures overall waveform similarity, the feature-based model formalises direction perception as a probabilistic judgement derived from uncertain detection of temporal landmarks within amplitude-defined windows. Notably, both models are applicable to conventional apparent motion paradigms, where discrete or pulsed stimuli with staggered onsets simulate movement. Although the inter-peak intervals in our stimuli (e.g., 167 ms for 30° and 500 ms or 90° at 0.5 Hz) exceed classical tactile temporal order judgement thresholds [

38], participants nonetheless exhibited robust directional performance and systematic confidence patterns. Notably, performance at 30° phase lag aligns with previously reported temporal order judgement thresholds (∼100 ms, [

38]), despite differences in stimulus type and parameters, suggesting that reliable direction perception can emerge without discrete onsets or overt spatial displacement. While supramodal attentional tracking could, in principle, support such judgements – e.g., by tracking salient events across time and space irrespective of sensory modality, – our model provides a tactile-specific alternative. It attributes direction perception to probabilistic comparisons between uncertain temporal landmarks (e.g., envelope peaks), detected within amplitude-defined integration windows. This framework captures This framework captures the non-linearity in psychometric curves, including both the reliable direction perception at shorter phase lags and the ambiguity at 180°, without invoking higher-level amodal mechanisms or cross-modal attentional strategies. Instead, it reflects constraints intrinsic to tactile processing, where perceptual uncertainty in temporal feature extraction shapes directional judgements.

Central to the perception of the vibration-induced motion studied here is the brain’s ability to track dynamic changes in the envelopes of tactile signals and extract directional information from their relative timing. This sensory strategy has analogues across species: arachnids, for example, detect prey using complex vibration patterns transmitted through webs or substrates, relying on finely tuned mechanosensory systems that evolved independently from vertebrate touch [

24]. In mammalian glabrous skin, Meissner’s and Pacinian corpuscles are specialised for detecting vibration [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43], with Pacinian corpuscles implicated in encoding vibrotactile pitch in both mice and humans [

44,

45,

46,

47]. My previous work demonstrated that rodents can discriminate vibrations based on both amplitude and frequency using their whiskers [

34,

48,

49]. Neurons in primary somatosensory cortex integrate these features in a way that supports vibrotactile perception. The present study builds on these principles, showing that temporal features – specifically phase relationships – can be exploited to generate robust perceptions of tactile motion across fingertips. This supports the idea that tactile systems, across species and sensor types, flexibly encode both spectral and temporal properties of mechanical stimuli to extract high-level perceptual content.

A major challenge in studying somatosensation is the ability to deliver tactile stimuli with precise control and reproducibility. In freely moving animals, variations in posture, movement, and skin contact can significantly affect the quality and consistency of tactile stimulation, introducing variability in the sensory input and complicating the interpretation of neural responses. In humans, the elastic properties of the skin can lead to trial-by-trial differences in receptor activation due to subtle changes in pressure, tension, or contact geometry [

3]. These inconsistencies may engage different mechanoreceptor subtypes, potentially altering the percept and confounding behavioural measurements. To address these limitations, I developed a vibrotactile stimulation paradigm in which the perception of motion direction is determined not by low-level features of the individual vibrations – such as absolute amplitude or frequency – but by the phase relationship between them. This design enables consistent control over the critical perceptual variable (phase difference), even when some variability in contact conditions is unavoidable. As such, it offers a robust and generalisable framework for investigating tactile motion perception and related decision-making processes.

Finally, this paradigm provides a powerful tool for probing tactile decision-making and perceptual inference under controlled temporal structure, paralleling the role of random-dot motion in visual neuroscience. By dissociating low-level vibration attributes from high-level motion perception, it offers a flexible approach for linking somatosensory encoding with computational models of evidence accumulation and perceptual categorisation, in both human and animal research. By revealing how the brain transforms temporally structured input into coherent motion percepts across the skin, this work contributes to a deeper understanding of somatosensory processing and lays the groundwork for future research in touch-based interfaces, neuroprosthetics, and tactile cognition.

Figure 1.

Detecting the motion of a remote vibrating source through patterns of vibrations sensed at two touch points. A, and denote the two touch points. The trajectory on plane is the rotation of trajectory on plane P around the touch axis . The grey closed curve shows the mirror of the trajectory with respect to the touch axis . B, For any arbitrary trajectory on the plane P, when the touch axis is orthogonal to P, the vibrations from source S received at and are in-phase. and represent the distances of and from P respectively. and denote the distances from the source S to and respectively, and vary as S moves along the trajectory. C, A circular trajectory with radius , centred at O. denotes the projection of touch point T onto plane P. h, r and d denote the distances from T to P, O and S, respectively. is the angle between and . D, and denote the distances from the source S to and , respectively, and vary as S moves along the trajectory. and are the distances from O to and , respectively. E, An example of anti-phase vibrations, when the projection of the axis (dashed line) onto the trajectory plane P passes through O. F, The two-dimensional geometry. All conversions as in D.

Figure 1.

Detecting the motion of a remote vibrating source through patterns of vibrations sensed at two touch points. A, and denote the two touch points. The trajectory on plane is the rotation of trajectory on plane P around the touch axis . The grey closed curve shows the mirror of the trajectory with respect to the touch axis . B, For any arbitrary trajectory on the plane P, when the touch axis is orthogonal to P, the vibrations from source S received at and are in-phase. and represent the distances of and from P respectively. and denote the distances from the source S to and respectively, and vary as S moves along the trajectory. C, A circular trajectory with radius , centred at O. denotes the projection of touch point T onto plane P. h, r and d denote the distances from T to P, O and S, respectively. is the angle between and . D, and denote the distances from the source S to and , respectively, and vary as S moves along the trajectory. and are the distances from O to and , respectively. E, An example of anti-phase vibrations, when the projection of the axis (dashed line) onto the trajectory plane P passes through O. F, The two-dimensional geometry. All conversions as in D.

Figure 2.

Motion direction discrimination task. A, The index and middle fingers of the right hand were stimulated using a pair of solenoid transducers (upper panel, B), which delivered amplitude-modulated vibrations (lower panel, B). C, On each trial, the envelopes of the two vibrations had a phase difference . The vibrations began at one of two points where their envelope amplitudes were equal (indicated by dashed lines).

Figure 2.

Motion direction discrimination task. A, The index and middle fingers of the right hand were stimulated using a pair of solenoid transducers (upper panel, B), which delivered amplitude-modulated vibrations (lower panel, B). C, On each trial, the envelopes of the two vibrations had a phase difference . The vibrations began at one of two points where their envelope amplitudes were equal (indicated by dashed lines).

Figure 3.

Experiment 1: Naturalistic vs. sinusoidal vibration envelopes. A, Schematic representation of naturalistic (exponential) and sinusoidal vibrations, along with their envelopes (thick curves). For illustration purposes, a 20 Hz carrier frequency is shown; the actual carrier frequency used in the experiments was 100 Hz. B, Motion direction discrimination accuracy, shown as the proportion of correct trials for exponential and sinusoidal vibrations. Bars represent the average across subjects, with error bars indicating the standard error of the mean (SEM). Data points represent individual participants ().

Figure 3.

Experiment 1: Naturalistic vs. sinusoidal vibration envelopes. A, Schematic representation of naturalistic (exponential) and sinusoidal vibrations, along with their envelopes (thick curves). For illustration purposes, a 20 Hz carrier frequency is shown; the actual carrier frequency used in the experiments was 100 Hz. B, Motion direction discrimination accuracy, shown as the proportion of correct trials for exponential and sinusoidal vibrations. Bars represent the average across subjects, with error bars indicating the standard error of the mean (SEM). Data points represent individual participants ().

Figure 4.

Experiment 2: Effect of envelope frequency on tactile motion perception. Motion direction discrimination performance as a function of phase difference, shown separately for each envelope frequency (indicated by colour). Data points represent across-subject averages (), with error bars indicating the standard error of the mean (SEM). Curves represent psychometric fits for each frequency condition.

Figure 4.

Experiment 2: Effect of envelope frequency on tactile motion perception. Motion direction discrimination performance as a function of phase difference, shown separately for each envelope frequency (indicated by colour). Data points represent across-subject averages (), with error bars indicating the standard error of the mean (SEM). Curves represent psychometric fits for each frequency condition.

Figure 5.

Experiment 3: Cognitive and metacognitive measures of tactile motion. A, Discrimination accuracy, measured as the proportion of correct responses, averaged across subjects (). For 0° and 180° phase differences, responses were pseudo-randomly labelled as correct or incorrect. B, Psychometric curves (choice likelihood) showing the proportion of “left” responses as a function of phase difference, averaged across subjects. C, Median reaction time (interval between stimulus onset and response), averaged across subjects, plotted as a function of phase difference. D, Average confidence ratings vs. phase differences. All error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Figure 5.

Experiment 3: Cognitive and metacognitive measures of tactile motion. A, Discrimination accuracy, measured as the proportion of correct responses, averaged across subjects (). For 0° and 180° phase differences, responses were pseudo-randomly labelled as correct or incorrect. B, Psychometric curves (choice likelihood) showing the proportion of “left” responses as a function of phase difference, averaged across subjects. C, Median reaction time (interval between stimulus onset and response), averaged across subjects, plotted as a function of phase difference. D, Average confidence ratings vs. phase differences. All error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

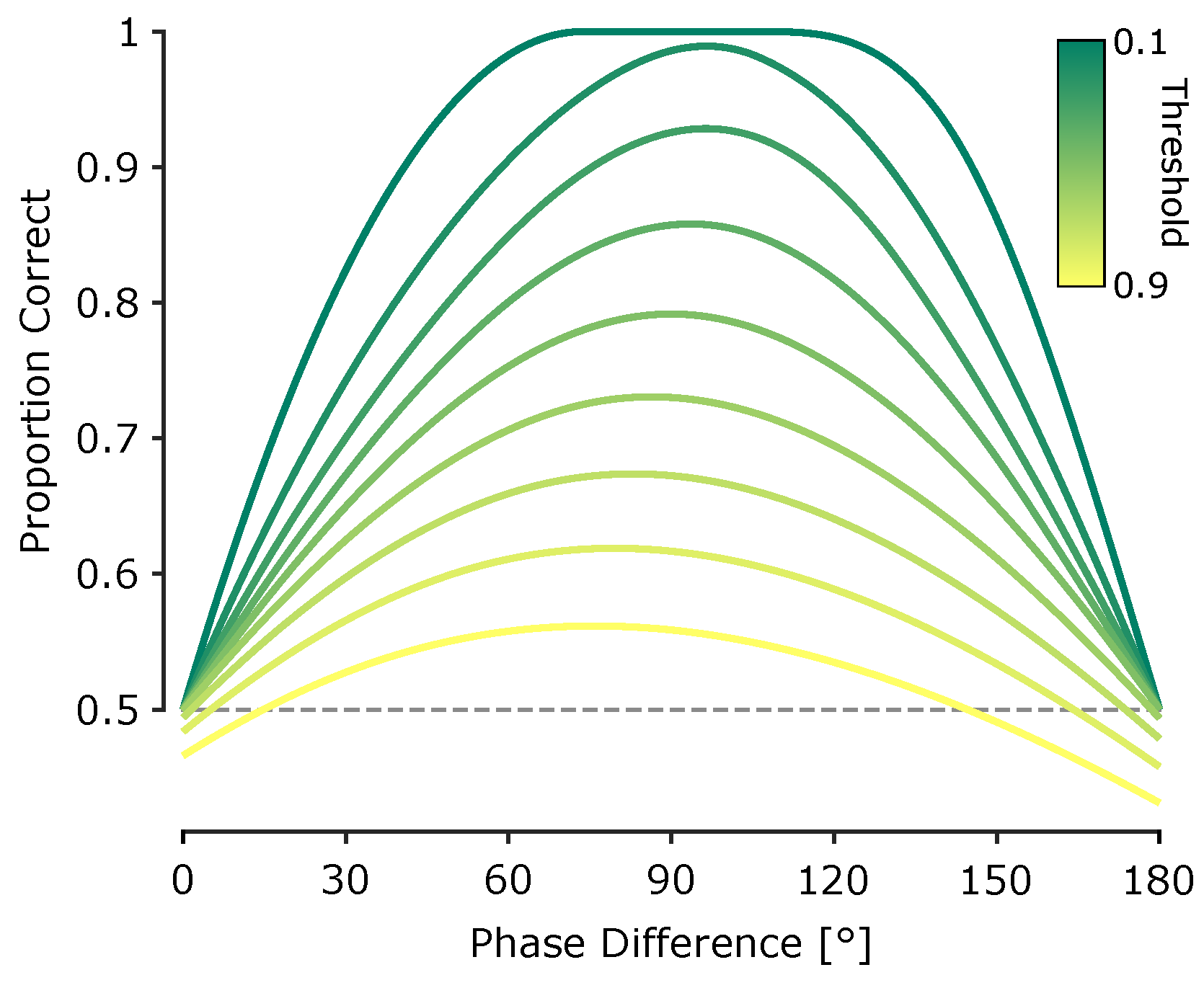

Figure 6.

Predicted direction discrimination performance from the probabilistic feature-based model. Model-predicted proportion of correct motion direction discrimination as a function of phase difference. Each trace corresponds to a different amplitude detection threshold (indicated by colour), expressed as a proportion of the peak envelope amplitude (from 0.1 to 0.9 in increments of 0.1).

Figure 6.

Predicted direction discrimination performance from the probabilistic feature-based model. Model-predicted proportion of correct motion direction discrimination as a function of phase difference. Each trace corresponds to a different amplitude detection threshold (indicated by colour), expressed as a proportion of the peak envelope amplitude (from 0.1 to 0.9 in increments of 0.1).