1. Introduction

Most human cancers arise from epithelial tissues. Epithelial cells exhibit remarkable plasticity and under proper stimulating cues, can undergo a reversible process known as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (1). Through EMT, epithelial cells shed their epithelial characteristics such as cell polarity and cell-cell junctions, and acquire the properties of mesenchymal cells such as enhanced motility, invasiveness, and resistance to apoptosis. Various pro-EMT signaling pathways (e.g., TGFβ) induce the expression of key EMT-driving transcription factors (EMT-TFs), mainly SNAI1/2, ZEB1/2, and TWIST, which repress epithelial genes and activate mesenchymal genes, resulting in variable extent of EMT (1). Single-cell gene expression analyses revealed that EMT is a nearly universal phenomenon in major types of human carcinomas (2). EMT reprograms global gene expression and signaling networks, endows cancer cells with increased migratory and invasive capacities, survival, and immune suppression, thus facilitating metastatic spreading and therapy resistance (3). Cancer cells undergoing a partial EMT critically contribute to metastasis formation (4-6). EMT also promotes resistance to chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy (3, 7). Due to its prevalence and prominent role in cancer, EMT has emerged as a potential therapeutic target of prime interest. Two recent studies showed that the embryonic factor netrin-1 exhibited pro-EMT activities, and blocking netrin-1 with a monoclonal antibody inhibited EMT, increased the proportion of epithelial cells, reduced metastasis, and potentiated therapy efficacy in mouse models of skin squamous cell carcinoma and endometrial adenocarcinoma (8, 9). These studies validate the clinical significance of targeting EMT. However, there are still very few pharmacological approaches available to suppress EMT or destruct cancer cells that have undergone EMT. No therapeutic interventions that specifically target EMT are used in clinical oncology practice. The molecular mechanisms by which EMT induces diverse malignant properties remain inadequately understood. Moreover, EMT-stimulated malignant phenotypes are manifold, making it challenging to target cancer cells exhibiting EMT. Uncovering key regulatory mechanisms underlying EMT-associated phenotypes will help develop anti-EMT therapeutic strategies.

The evolutionarily conserved Hippo signal transduction pathway was originally characterized in fruit fly. The core of the Hippo pathway in mammals consists of a kinase cascade in which the protein kinases MST1/2 (Hippo in fly) phosphorylate and activate the LATS1/2 kinases, which then phosphorylate the main downstream effectors–the YAP/TAZ transcriptional coactivators, causing their cytoplasmic retention and consequent inactivation (10). Hippo signaling activity is tightly regulated by a wide range of signals (10, 11). When Hippo signaling (i.e., the kinase cascade) is inactive, YAP/TAZ are hypo-phosphorylated and localize in the nucleus where they interact with the TEAD transcription factors to activate their target genes. WWC1 (KIBRA) was identified as a key upstream activator component of the Hippo signaling pathway in fly in vivo (12-14). Loss of WWC1 phenocopied loss of canonical Hippo signaling in Drosophila. Biochemically, WWC1 is a multi-domain scaffold protein (15), and acts as an organizer by interacting with LATS1/2, Merlin (NF2), SAV1, and multiple other components in the Hippo pathway to form supramolecular complexes/condensates, which facilitate phosphorylation and activation of LATS1/2 (12-14, 16-20). The Hippo pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating organ size, tissue growth, regeneration, and fibrosis. Although genetic alterations in the core components of the Hippo pathway are rare, dysregulation of Hippo signaling and hyperactivation of YAP/TAZ are pervasive in human cancer, which transcriptionally drive cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and survival, leading to tumor development, metastasis, and therapy resistance (21, 22). Such malignant phenotypes largely mimic those induced during EMT. In addition, activation of YAP/TAZ in cancer cells exerts complex effects on immune responses (23). LATS1/2 deletion in mouse cancer cells enhanced anti-tumor adaptive immunity and led to tumor destruction (24). On the contrary, YAP activation in cancer cells promoted the recruitment of immunosuppressive type II (M2) macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), generating an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (25-27). Moreover, YAP/TAZ activation in human cancer cells directly upregulated the expression of immune checkpoint PD-L1 (CD274, B7-H1) to cause T-cell exhaustion and immune evasion (28-32).

In the present study, we uncovered that WWC1 was a direct target for transcriptional repression by EMT-TFs, and thus was inherently downregulated by EMT. Repression of WWC1 impaired LATS activation, leading to constitutive activation of YAP. Therefore, EMT may represent a non-genetic mechanism for YAP activation in carcinomas. Pharmacological blockade of TEAD-YAP abrogated multiple EMT-enhanced malignant phenotypes without morphologically reversing EMT, suggesting that EMT activates YAP, and active YAP in turn mediates diverse EMT-associated phenotypes. YAP activation also induced B7 family immune checkpoints VSIR (VISTA, B7-H5) and PD-L2 (CD273, B7-DC) (33), conferring resistance to effector T cells. Overall, the study suggests that EMT promotes new malignant properties and immune evasion by activating YAP, and highlights YAP as an attractive target for therapeutic intervention of cancer cells exhibiting EMT.

2. Results

2.1. WWC1 Is a Direct Transcriptional Target of ZEB Transcription Factors and Is Downregulated During EMT

ZEB and SNAIL families of EMT-TFs directly repress a large number of epithelial-enriched genes for EMT induction. To characterize EMT-associated phenotypes, we sought to identify new important genomic targets of EMT-TFs. We analyzed ChIP-seq data of ZEB1 genomic binding in mesenchymal triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell line MDA-MB-231 (34). Robust binding of ZEB1 was observed at the proximal promoter and intron 1 of WWC1 (

Figure 1A), which encodes a key upstream activating component of the Hippo pathway. A specific E-box motif (5′-CACCTG), the consensus binding sequence for ZEB, was present at the center of both ZEB1 binding peaks, suggesting that the binding is direct. The ReMap database consists of a large-scale integrative analysis of all public ChIP-seq data for various transcriptional regulators in a wide variety of cell types (35). Based on the ReMap data, ZEB1/2 displayed binding to the WWC1 locus in multiple human cell lines (

Figure 1B). Weaker binding of SNAI2 at this genomic region (mostly in intron 1 of WWC1) was also detected. The data suggest that WWC1 is a direct genomic target of EMT-TFs ZEB and SNAIL.

ZEB and SNAIL generally act as transcriptional repressors and repress the expression of many epithelial genes during EMT. Given their binding at the

WWC1 locus, we determined if WWC1 expression was regulated by EMT. TGFβ is a potent EMT inducer and can upregulate multiple EMT-TFs (1). TGFβ induces particularly robust molecular and phenotypic changes characteristic of EMT in NMuMG mouse mammary epithelial cells and A549 human lung cancer cells (36). We treated NMuMG cells with TGFβ, and found that WWC1 expression was substantially downregulated (

Figure 1C). We previously established an EMT cell model, DCIS-Sna-ER, which stably expressed inducible SNAI1 in MCF10DCIS.com transformed human basal breast epithelial cells (37). Induction of SNAI1 potently repressed the expression of WWC1 and the canonical epithelial marker CDH1 (E-cadherin) (

Figure 1D). Since WWC1 was downregulated by EMT, we investigated if its expression correlated with epithelial/mesenchymal markers in 1,673 established human cell lines in the DepMap datasets. Expression of WWC1 strongly correlated with epithelial markers CDH1 and EPCAM, and inversely with ZEB1/2 (

Figure 1E), suggesting that WWC1 is highly expressed in epithelial cells and downregulated in EMT/mesenchymal cells. Collectively, the results suggest that WWC1 is transcriptionally repressed by EMT. As WWC1 is a direct target of EMT-TFs, its downregulation is an inherent feature of EMT.

2.2. EMT Blocks LATS and Causes Constitutive Activation of YAP

WWC1 is important for the activation of Hippo signaling. Loss or depletion of WWC1 inhibits the LATS kinase, leading to hypo-phosphorylation and hence activation of YAP. Because EMT markedly downregulated WWC1, we asked if EMT could activate YAP. Serum contains lysophosphatidic acid that inhibits LATS, and serum starvation activates LATS to phosphorylate YAP (38). We treated NMuMG cells with or without TGFβ for EMT induction, followed by serum starvation. Western blotting analysis with antibodies recognizing YAP Ser127 phosphorylation (a LATS phosphorylation site) showed that YAP was barely phosphorylated in NMuMG cells in regular media (

Figure 2A). When NMuMG cells were serum-starved, YAP became strongly phosphorylated (

Figure 2A), demonstrating that serum starvation potently activates LATS. By contrast, when TGFβ-treated NMuMG cells were under serum starvation, YAP remained hypo-phosphorylated (

Figure 2A). The results suggest that TGFβ-induced EMT prevents LATS activation by serum starvation.

LATS-mediated phosphorylation promotes cytoplasmic retention of YAP. We investigated YAP subcellular localization in EMT cells under serum starvation. When NMuMG cells were cultured in regular media, YAP was mostly nuclear (

Figure 2B). Upon serum starvation, YAP was mostly exported to the cytoplasm (

Figure 2B), consistent with LATS activation and YAP phosphorylation. TGFβ treatment induced EMT-like morphological changes (e.g., cell elongation), and YAP was localized in the nucleus (

Figure 2B). However, when the TGFβ-treated NMuMG cells were under serum starvation, YAP still remained primarily nuclear (

Figure 2B). The YAP subcellular localization patterns are consistent with its phosphorylation states (

Figure 2A). Taken together, the results suggest that LATS kinase activation by stress signals is blocked in cells having undergone EMT, resulting in constitutive YAP hypo-phosphorylation and nuclear localization even under stress conditions.

2.3. EMT Activates YAP Target Gene Expression

WWC1 is an upstream activator of Hippo signaling and is required to inhibit YAP activity. EMT potently downregulated WWC1 expression, and led to persistent hypo-phosphorylation and nuclear localization of YAP. Active YAP acts as a transcriptional coactivator for the TEAD transcription factors to activate target gene expression. YAP and TAZ form liquid-liquid phase-separated condensates to promote gene transcription (39-41). Nuclear localization alone does not indicate their full transcriptional activation. Therefore, we determined if EMT could upregulate YAP target gene expression. In a TGFβ-induced EMT model, YAP signature targets CTGF and CYR61 exhibited low basal expression in mouse NMuMG cells in regular media, despite nuclear localization of YAP; upon EMT induction by TGFβ, their expression was strongly upregulated (

Figure 3A). When the EMT cells were under serum starvation, expression of CTGF and CYR61 was not downregulated and remained high (

Figure 3A). Similarly, in a SNAI1-induced EMT model, EMT markedly upregulated representative YAP target genes, including AXL, CTGF, CYR61, and GLI2, in human breast carcinoma cells in media with or without serum (

Figure 3B). Interestingly, for another group of YAP target genes (e.g., AMOTL2, anti-apoptotic BCL2 and BCL2L1), their basal expression was quite high, and serum starvation significantly repressed their expression (

Figure 3C), suggesting that their basal expression is attributed to YAP activation, and Hippo signaling is intact and responsive to serum starvation; Following EMT induction, expression of these genes did not increase, but was sustained when cells were further under serum starvation (

Figure 3C), suggesting that EMT totally blocks serum starvation-stimulated LATS activation. Overall, the results support that EMT prevents LATS activation, leading to constitutive YAP activation and high expression of YAP target genes. In line with this notion, expression of CTGF and CYR61 strongly correlated with mesenchymal markers in 1,673 human cell lines (

Figure S1). Together, the results suggest that EMT potently activates YAP target gene expression.

2.4. Repression of WWC1 Is Key to Activating YAP by EMT

We first took a pharmacological approach to verify that elevated expression of YAP target genes during EMT was indeed due to YAP activation. In the SNAI1-induced EMT model, upregulation of AXL during EMT was largely abrogated by treatment with TEAD-YAP inhibitor verteporfin (42) (

Figure 4A). CD44 is often considered a cancer stem cell marker and its expression is induced by EMT (43). CD44 was recently identified as a direct target gene of YAP (44). Upregulation of CD44 during EMT was also blocked by verteporfin (

Figure 4A). The results suggest that YAP activation causes the upregulation of its target genes during EMT.

Proper Hippo signaling requires intact apical cell junctions and polarity (45, 46), which are part of epithelial characteristics. Such epithelial structures are disrupted during EMT, presumably impairing Hippo signaling and activating YAP. We next asked if repression of WWC1 was critical for YAP activation by EMT. The highly mesenchymal Hs578T TNBC cells were often used as a stable EMT cell model. Based on DepMap gene expression, Hs578T cells exhibit very little expression of WWC1 but high expression of many YAP target genes (indicative of YAP activation). We infected Hs578T cells with lentiviruses inducibly expressing exogenous WWC1. Induction of WWC1 did not cause evident morphological changes (i.e., mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition), but substantially downregulated many YAP target genes (e.g., CTGF, CYR61) (

Figure 4B). Taken together, the results suggest that induction of YAP target genes in EMT/mesenchymal cells is largely mediated by active YAP, and repression of WWC1 is a key mechanism underlying YAP activation by EMT.

2.5. EMT-Stimulated Cellular Phenotypes Are Attributed to YAP Activation

Both EMT and YAP drive many overlapping cellular phenotypes. As EMT activates YAP transcriptional function, we determined if EMT-stimulated cell motility and invasiveness were attributed to YAP activation. In a Transwell-based cell migration assay, SNAI1-driven EMT boosted cell migration through a porous membrane, which however was substantially suppressed by treatment with TEAD-YAP inhibitor CA3 (47) or MGH-CP1 (48) (

Figure 4C). In a Transwell-based cell invasion assay in which the porous membrane was pre-coated with a layer of extracellular matrix (ECM) protein mixture, TGFβ stimulated A549 lung cancer cell invasion through ECM, and treatment with CA3 or MGH-CP1 suppressed the pro-invasion effects of TGFβ (

Figure 4D). The results suggest that EMT-enhanced cell motility and invasiveness are dependent on YAP activation.

EMT confers resistance to apoptosis and certain chemotherapy drugs, whereas YAP is known to activate anti-apoptotic genes and promote cell survival. Therefore, we tested if EMT-conferred chemoresistance was mediated by YAP. ABT-737 is a potent BH3 mimetic inhibitor of BCL2 and BCL2L1, and induces apoptosis (49-51). Camptothecin is a topoisomerase I inhibitor that causes DNA damage and apoptosis (52), and its cytotoxicity is suppressed by increased BCL2 expression (53). Under serum starvation conditions, A549 cancer cells were sensitive to ABT-737 and camptothecin (

Figure 4E). Treatment with TGFβ rendered A549 cells resistant to these compounds (

Figure 4E). However, co-treatment with verteporfin re-sensitized these cells to ABT-737 and camptothecin (

Figure 4E). The transcriptional activity of YAP depends on the bromodomain protein BRD4, a co-activator (54). Treatment with JQ1, a small-molecule inhibitor of BRD4 (55), also overcame TGFβ-induced resistance to ABT-737 and camptothecin (

Figure 4E). The results suggest that YAP critically contributes to EMT-induced apoptosis resistance and chemoresistance.

It was previously reported that TGFβ-induced EMT led to increased cell size and cellular protein content by activation of the mTOR pathway (56). There exist extensive crosstalks between the mTOR and Hippo pathways, and YAP can activate mTOR (57). Therefore, we investigated if EMT increased cell sizes via YAP. Following TGFβ treatment, A549 and NMuMG cells became enlarged (

Figure 4F). Verteporfin treatment reversed the cell size increases in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 4F), suggesting that YAP activity is required for EMT-induced cell size growth.

We further validated that suppression of EMT-stimulated cellular phenotypes by pharmacological inhibition of YAP was not due to possible reversal of EMT. When NMuMG and A549 cells were treated with TGFβ, typical EMT-like morphological changes were observed, and the epithelial marker CDH1 was downregulated (

Figure S2). When these EMT cells were further treated with various TEAD-YAP inhibitors for one day, they maintained the mesenchymal-like morphology, and CDH1 levels were not restored (

Figure S2), suggesting that under the experimental settings, pharmacological inhibition of TEAD-YAP does not overtly reverse TGFβ-driven EMT. Therefore, pharmacological blockade of TEAD-YAP suppresses EMT-associated cellular phenotypes without reversing the EMT state.

2.6. YAP Activation Induces Immune Checkpoints and Suppresses T Cell Effector Function.

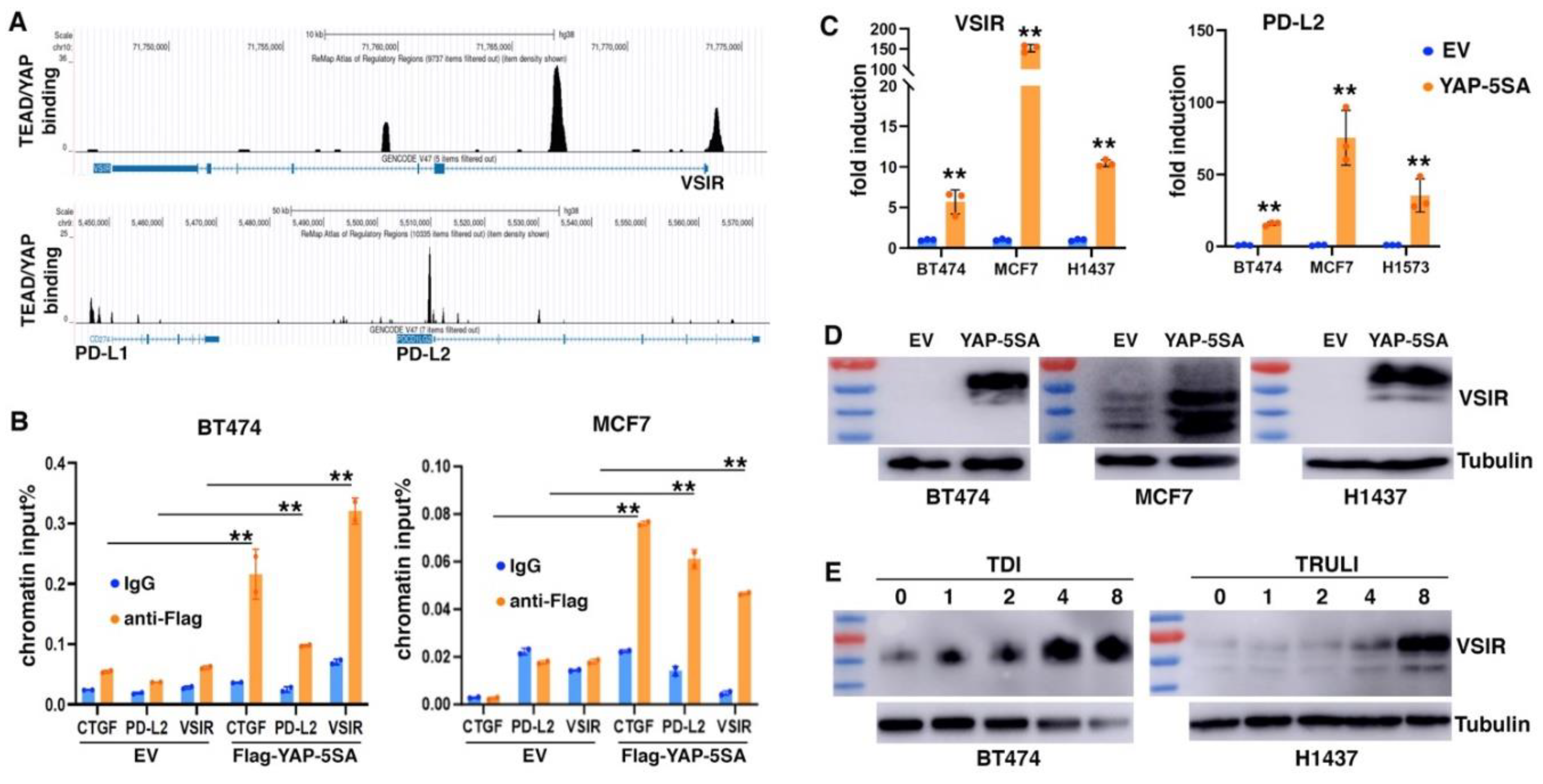

Immune suppression is increasingly recognized as a critical EMT function. We asked if YAP activation might contribute to EMT-mediated impact on tumor immune responses. We mined the ChIP-seq data of YAP and TEAD4 in MDA-MB-231 cells (SRA: SRP055170; GEO: GSE66081) (58) and identified their evident genomic binding at two members of B7 family of immune checkpoints (33): VISTA (VSIR) and PD-L2 (PDCD1LG2). ReMap ChIP-seq data confirmed the strong binding of TEAD1/4 and YAP at the promoter and intron 1 of VSIR as well as at the promoter of PD-L2 in a variety of cancer cells (

Figure 5A). Weak binding of TEAD and YAP was also found at the 5’ region of PD-L1 (CD274) (

Figure 5A), which was previously reported as a YAP/TAZ target gene (28-32). To validate YAP binding at VSIR and PD-L2, we transduced BT474 and MCF7 epithelial breast cancer cells with lentiviruses expressing Flag-tagged YAP-5SA (an active form of YAP) (59), and performed ChIP assay with anti-Flag antibodies or IgG antibody control. Significant binding of Flag-YAP was detected at CTGF (positive control), VSIR and PD-L2 (

Figure 5B), confirming that VSIR and PD-L2 are direct genomic target genes of YAP.

We next determined if expression of VSIR and PD-L2 was regulated by YAP. Overexpression of YAP-5SA in MCF7 and BT474 cells as well as H1437 and H1573 lung cancer cells robustly upregulated VSIR and PD-L2 RNA expression (

Figure 5C). We further verified VSIR induction by YAP-5SA by immunoblotting. Human VSIR protein has a predicted molecular weight around 34 kDa, but migrates at 55-70 kDa in SDS-PAGE due to glycosylation (60). There was little basal expression of VSIR in BT474, MCF7, and H1437 cells, but transduction with YAP-5SA markedly induced VSIR protein expression (

Figure 5D). The induced VSIR proteins were highly glycosylated (~70 kDa) in BT474 and H1437 cells, while less glycosylated in MCF7 cells (

Figure 5D). Moreover, we investigated potential VSIR induction by activation of endogenous YAP. TDI-011536 (61) and TRULI (62) are related potent LATS inhibitors, and both prevent YAP phosphorylation by LATS. We treated BT474 and H1437 cells with these compounds and observed dose-dependent induction of VSIR (

Figure 5E). The results suggest that YAP activation directly induces VSIR and PD-L2 expression.

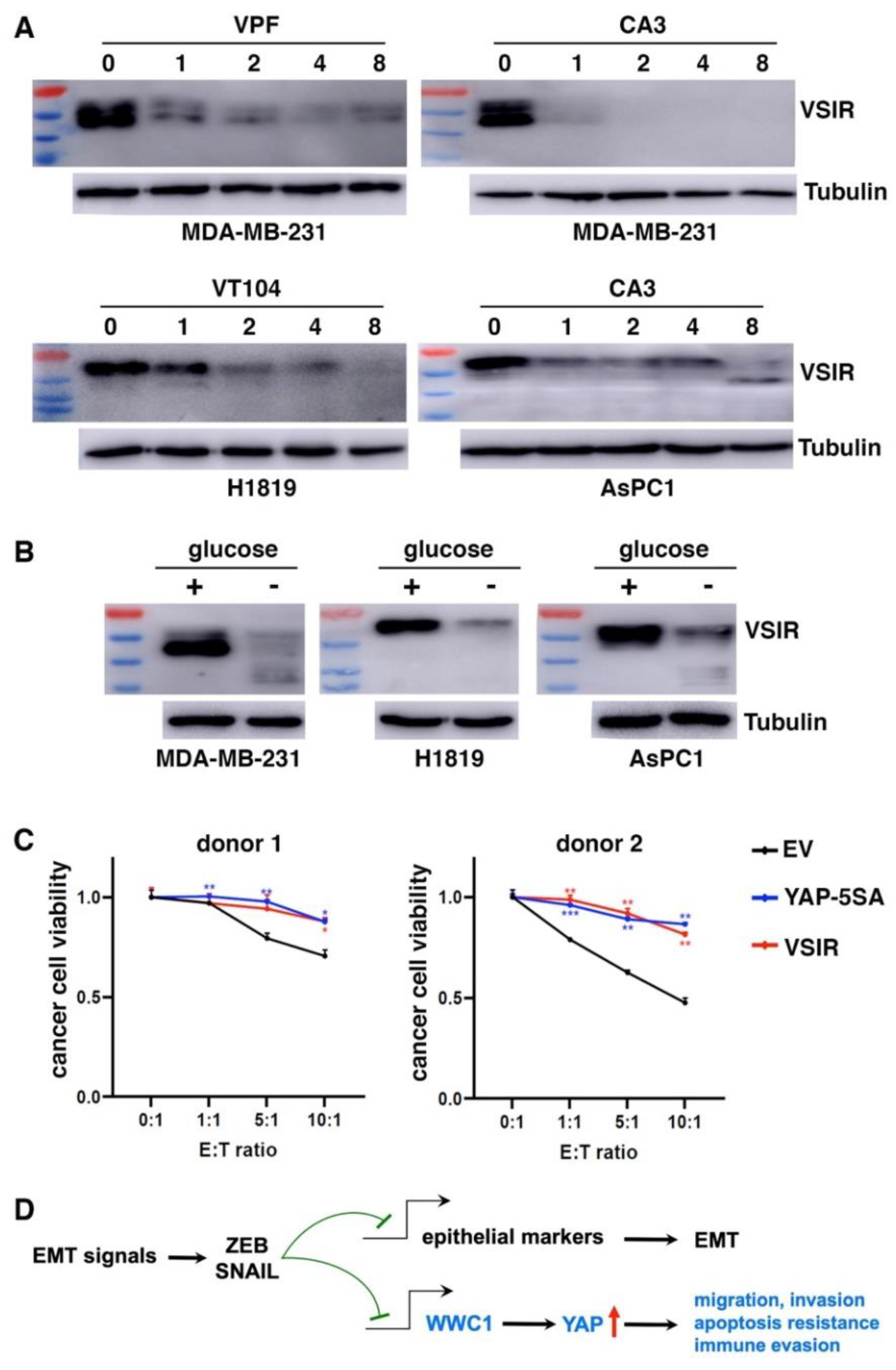

We further determined if high VSIR expression in certain cancer cells was driven by endogenous YAP. Consistent with YAP activation by EMT, MDA-MB-231 mesenchymal cancer cells exhibited high basal expression of VSIR proteins (

Figure 6A). H1819 lung cancer and AsPC1 pancreatic cancer cells also exhibited high YAP activity (evidenced by high expression of YAP target genes) and high VSIR expression (

Figure 6A). We treated these cells with TEAD-YAP inhibitors verteporfin, CA3, and VT104 (63). YAP inhibition downregulated VSIR in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 6A). In addition to pharmacological inhibition of YAP, stress signals such as glucose starvation cause YAP phosphorylation and inactivation (64, 65). When cultured in glucose-free media, MDA-MB-231, H1819, and AsPC1 cells all showed markedly downregulated VSIR protein expression (

Figure 6B). These results suggest that YAP activation is required for high VSIR expression in mesenchymal or YAP-activated cancer cells.

As YAP activation induces multiple immune checkpoints, we asked if it conferred resistance to CD8⁺ T cell–mediated cytotoxicity. We cocultured increasing numbers of activated human HLA-A2⁻ CD8⁺ T cells with control, YAP-5SA- or VSIR-overexpressing BT474 cancer cells. YAP activation or VSIR overexpression increased cancer cells’ resistance to T cell-mediated destruction (

Figure 6C). Taken together, YAP activation induces immune checkpoints and enables cancer cells to resist effector T cells.

3. Discussion

3.1. EMT Represents a Non-Genetic Mechanism Activating YAP in Cancer

YAP is pervasively activated in human cancer, however, genetic alterations in the core components of the Hippo signaling pathway are rare. WWC1 is a scaffold protein that integrates multiple Hippo pathway components into biological complexes/condensates, and is critical for the activation of Hippo signaling. In this study, WWC1 is identified as a direct transcriptional target of EMT-TFs. EMT inherently represses WWC1 expression, thus deactivating Hippo signaling and constitutively activating YAP even in the absence of mutations. Because restoration of WWC1 in mesenchymal cells by exogenous expression was sufficient to inactivate YAP (

Figure 4B), downregulation of WWC1 is a critical mechanism by which EMT activates YAP. Therefore, EMT represents a non-genetic mechanism underlying YAP activation. As the occurrence of EMT is prevalent in human carcinomas (2), most tumors are expected to contain a subpopulation of malignant cells that exhibit EMT and YAP activation. It was previously reported that overexpression of YAP/TAZ or knockdown of WWC1 promoted EMT (66-70). Therefore, EMT can be induced by diverse signaling events (inactivation of Hippo signaling is one of them), and following EMT, YAP is activated and in turn maintains the EMT state by a feed-forward loop.

3.2. YAP Mediates EMT-Stimulated Malignant Phenotypes

EMT is accompanied by acquisition of manifold malignant phenotypic changes in cancer cells, but the underlying molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood. It has been challenging to directly target EMT or simultaneously target its diverse phenotypes. Here we uncovered that the EMT process intrinsically inhibits Hippo signaling, leading to constitutive YAP activation. The YAP-dependent transcriptional program promotes a variety of cellular traits that are strikingly similar to those induced during EMT. Indeed, we found that pharmacological inhibition of YAP largely abolished EMT-stimulated cell migration/invasion, apoptosis resistance, and cell size growth, without evident reversal of EMT, supporting that YAP is a key common mediator for EMT-associated diverse phenotypes (

Figure 6D). Identification of a common molecular pathway underlying EMT-associated multiple malignant properties is desirable for developing new therapeutic approaches. TEAD-YAP inhibitors may effectively overcome EMT’s contributions to malignant progression and drug resistance.

3.3. The EMT-YAP Axis Drives Immune Evasion

Since the initial discovery of EMT’s role in immunosuppression (71), emerging evidence has revealed that EMT induces immune evasion through multiple mechanisms (72), including upregulation of PD-L1 expression (73). Meanwhile, YAP/TAZ activation in human cancer cells directly induced PD-L1 expression, leading to T-cell exhaustion (28-32). This study further uncovered that activation of YAP induces expression of PD-L2 and VSIR. PD-L1/L2 are PD-1 ligands and targets of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. In adaptive immune response, tumor-engaged effector T cells secrete interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), which induces PD-L1/L2 expression on tumor cells (74-76). While PD-L1 dampens T cell cytotoxicity, its expression in this scenario is also a surrogate marker of preexisting adaptive immunity. Therefore, tumor PD-L1 expression has often been used as one of the predictive biomarkers for sensitivity to immunotherapy targeting PD-1/PD-L1. However, PD-L1 as a predictive biomarker has limitations. An analysis of FDA-approved immunotherapies found that PD-L1 was predictive in less than 30% of cases (77). Because PD-L1 can be induced by diverse mechanisms other than IFN-γ signaling, its expression driven by oncogenic pathways (e.g., YAP activation) does not reflect preexisting T cell immunity and is not a suitable biomarker for immunotherapy response.

VSIR is also a B7 family immune checkpoint molecule expressed in multiple immune cell types (esp. those of the myeloid lineage) and tumor cells (78). DepMap gene expression data show that among a large panel of established human cell lines, VSIR is broadly expressed in human cancer cells, including various types of solid tumors. VSIR expression in tumor cells suppresses T cell proliferation in vitro and tumor infiltration in vivo (79). Several VSIR-binding proteins have been reported. Recently, LRIG1 was identified as an inhibitory receptor for VSIR to suppress T-cell immune responses (80). LRIG1 is highly expressed on activated tumor-specific CD8+ T cells, and the VSIR-LRIG1 signaling axis inhibits T cell proliferation, survival, and effector function (80). Overall, YAP may induce multiple immune checkpoint proteins in cancer cells to inhibit T-cell antitumor activity and enable immune escape. Of note, induction of such immune checkpoints by YAP may be context/species-dependent. We transduced several murine carcinoma cell lines with lentiviral YAP-5SA but failed to induce these immune checkpoint proteins. It was reported previously that YAP activation unexpectedly enhanced anti-tumor immunity (24); it is possible that LATS1/2 deletion in mouse tumor cell models (B16, SCC7, and 4T1) in that study did not upregulate the immune checkpoints.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 improve antitumor T cell responses and patient survival. However, the overall response rate to these immunotherapies is still low. YAP-activated human tumor cells likely resist anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy due to the expression of additional immune checkpoint proteins. Indeed, combinatorial treatment with anti-VSIR and anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 antibodies achieved synergistic therapeutic efficacy in syngeneic murine tumor models (81-84). Inclusion of VSIR blockade in combinatorial immunotherapies may help overcome resistance to current ICIs in YAP-activated cancer cells. The immune checkpoint inhibitor CA-170 has dual targeting activities against PD-L1/L2 and VSIR (85) and may be effective for targeting tumors with YAP activation. Administration of TEAD-YAP inhibitors downregulates immune checkpoint expression in YAP-activated tumors and may also enhance their responses to ICIs.

4. Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Treatment. NMuMG, Hs578T, and A549 (from ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin. DCIS-Snai1-ER cells were previously established (37) and were maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 5% horse serum. Recombinant human TGFβ1 protein (R&D SYSTEMS, 7754-BH), 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma, H6278), Verteporfin (TargetMol, T3112), MGH-CP1 (TargetMol, T9032), CA3 (Sigma, SML2647), VT104 (TargetMol, T67872), JQ-1 (TargetMol, T2110), ABT-737 (Apexbio, A8193), TRULI (Cayman Chemical, 36623), TDI-011536 (TargetMol, T60144).

Antibodies. Immunofluorescence: YAP (D8H1X) XP Rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling, 14074). Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 488 (Invitrogen, A32731). Western blotting: Phospho-YAP (S127) Antibody (Cell Signaling, 4911), VSIR/VISTA antibody (Cell Signaling, 64953), E7 anti-β tubulin (DSHB), Mouse Anti-E-Cadherin (BD Biosciences, 610181), Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Antibody, Human Serum Adsorbed and Peroxidase-Labeled (LGC, 074-1806), Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Antibody, Human Serum Adsorbed and Peroxidase-Labeled (LGC, 074-1516).

RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and real-time PCR. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and purity were measured by nano-drop. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) reverse transcriptase (NEB, M0253). Real-time PCR was then performed with PowerUp SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems, A25741). Relative mRNA expression was calculated using the comparative ΔΔCt method and normalized to β-actin levels. Primers:

| Gene |

Forward Primer |

Reverse Primer |

| Mouse β-actin |

GTCGTCGACAACGGCTCC |

TTCCCACCATCACACCCTGG |

| Mouse WWC1 |

AGTCGATGTCTGCACCACTG |

GATTGTACCAGCGCGTTGAC |

| Mouse CTGF |

ACCGCAAGATCGGAGTGTG |

TCCAGGCAAGTGCATTGGT |

| Mouse CYR61 |

ACCCTTCTCCACTTGACCAG |

TTAGCGCAGACCTTACAGCA |

| Human β-actin |

GGATTCCTATGTGGGCGACGA |

GCGTACAGGGATAGCACAGC |

| Human WWC1 |

CAGGTGCAGACAGGCAAAGAT |

TGCCTGCCTTTGCTTGTAGA |

| Human CTGF |

GCTTACCGACTGGAAGAC |

ACTTGATAGGCTTGGAGATT |

| Human CYR61 |

AAGGGGCTGGAATGCAACTT |

TTGGGGACACAGAGGAATGC |

| Human AXL |

CAGAGGTGCTAATGGACATAG |

CGGTGGACAAGGAAGAGAG |

| Human GLI2 |

GTTCGAGCAGCTCAAGAAGG |

GGCTCAGCATGGTCACCTC |

| Human AMOTL2 |

AGGAGGCTGCAAGACTTCAA |

CAGCTTCTCTTGCTCCTGCT |

| Human ARHGEF17 |

CCGCCTTGGTTTTGAACAGG |

GCTGTTGCAGACCCATACCT |

| Human BCL2 |

CTTTGAGTTCGGTGGGGTCA |

CCGTACAGTTCCACAAAGGC |

| Human BCL2L1 |

CTGACATCCCAGCTCCACAT |

GTGGATGGTCAGTGTCTGGT |

| Human CRY1 |

CAGGTTGTAGCAGCAGTGGA |

GACTAGGACGTTTCCCACCA |

| Human LATS2 |

TCATCCACCGAGACATCA |

CCACACCGACAGTTAGAC |

| Human PTPN14 |

GTTCACGTCCAGTGTGGTGA |

AGCAGTTGAGGGAGTTGACG |

| Human TEAD1 |

GATGATGCTGGGGCTTTTTA |

GCCATTCTCAAACCTTGCAT |

| Human CD44 |

CCTGCCCAATGCCTTTGATG |

CAGGGACTGTCTTCGTCTGG |

| Human CDH1 |

TTACTGCCCCCAGAGGATGA |

TGCAACGTCGTTACGAGTCA |

| Human VSIR |

CCCATCCTCCTCCCAGGATA |

GCCGGGGTTTTCAATCCCTT |

| Human PD-L2 |

CAAGTGAGGGACGAAGGACAG |

GACGTTTGGCCAGGATACTTCT |

Immunofluorescence. Cells were seeded on coverslips and treated with TGFβ or mock-treated for 2 days, followed by serum starvation for 1 day. Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100. Coverslips were then incubated with anti-YAP antibody overnight at 4°C followed by secondary antibody incubation for 1 hour at 37°C. Coverslips were mounted on slides and visualized under a fluorescence microscope.

Western blotting. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing 2% SDS and boiled for 20 min. Cell lysates were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels before being transferred onto Immobilon-P PVDF Membrane (Millipore, IPVH00010). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 hour and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Following washes with 1x TBST, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour. Signals were detected using SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, 34580).

ChIP assay. At least 5 × 10

6 cells were collected and crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min, followed by quenching with 125 mM glycine. Cells were then resuspended in cell lysis buffer and nuclei lysis buffer. Chromatin was sheared to 200–500 bp fragments on ice using a Bioruptor disruptor (Diagenode, Denville, NJ). Sheared chromatin was incubated overnight with Flag antibody (Sigma, F1804) and protein A/G magnetic beads (Medchemexpress, HY-K0202) rotating at 4°C. After extensive washing, crosslinks were reversed, and DNA was purified using a PCR purification kit and subjected to real-time PCR as described above. ChIP PCR primers:

| Gene |

Forward Primer |

Reverse Primer |

| CTGF |

CTCTTCGCACCACTCCTGAT |

CAGTGGACAGAACAGGGCAA |

| PD-L2 |

TGTTCAAGCGATGGGACGAA |

GATGTGGGGCTGAACACTCA |

| VSIR |

CTAAGCTCACGCCCTGTCAT |

CTGTGGCACCCTCAGATGTT |

Transwell migration and invasion assay. Materials: Matrigel Growth Factor Reduced Basement Membrane Matrix (Corning, 356231), 6.5 mm Transwell with 8.0 µm Pore Polycarbonate Membrane Insert (Costar, 3422). Cells were treated with or without TGFβ/4-HT for 2 days, resuspended in serum-free media and seeded into transwell inserts containing TGFβ/4HT and YAP-TEAD inhibitors. Inserts were placed into lower chambers containing media supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated for 24 hours. Non-migrated cells were removed with cotton swabs, while migrated cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS and stained with Crystal Violet. For invasion assay, chambers were pre-coated with Matrigel matrix before cell seeding.

Flow cytometry. At least 1x106 cells per group were collected and resuspended in pre-cold PBS. Cell size was determined by forward scatter using BD Accuri C6 Plus Flow Cytometer.

Human T cell cytotoxicity assay. Naïve CD8⁺ T cells were isolated from leukapheresis-derived blood of healthy donors obtained from LifeSouth Community Blood Centers (Gainesville, FL), using the EasySep Human Naïve CD8⁺ T Cell Isolation Kit (Stemcell, 19258). The isolated cells were activated with Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher, 11161D) at a 1:1 bead-to-cell ratio in the presence of 100 IU/mL IL-2 and 5 ng/mL IL-7 (R&D Systems). After 48 hours of incubation, beads and cytokines were removed. Activated CD8⁺ T cells were co-cultured with pre-seeded tumor cells at effector-to-target (E:T) ratios of 1:1, 5:1, and 10:1. Following a 24-hour incubation, non-adherent T cells were removed by washing with PBS. Remaining adherent tumor cells were stained with 2μM Calcein-AM (AAT Bioquest, 22003) and quantified to assess viability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joachim Kremerskothen (University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany) for providing the WWC1 expression constructs. YAP (5SA) cDNA was a gift from Dr. Rod Bremner (Addgene plasmid # 174170). The project was in part supported by the University of Florida Health Cancer Center Pilot Grant MOO-FY22-03.

References

- S. Lamouille, J. Xu, R. Derynck, Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15, 178-196 (2014).

- D. P. Cook, B. C. Vanderhyden, Transcriptional census of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer. Sci Adv 8, eabi7640 (2022). [CrossRef]

- A. Dongre, R. A. Weinberg, New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20, 69-84 (2019). [CrossRef]

- I. Pastushenko et al., Identification of the tumour transition states occurring during EMT. Nature 556, 463-468 (2018). [CrossRef]

- K. P. Simeonov et al., Single-cell lineage tracing of metastatic cancer reveals selection of hybrid EMT states. Cancer Cell 39, 1150-1162.e1159 (2021). [CrossRef]

- F. Lüönd et al., Distinct contributions of partial and full EMT to breast cancer malignancy. Dev Cell 56, 3203-3221.e3211 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D. Singh, H. R. Siddique, Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer progression: unraveling the immunosuppressive module driving therapy resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev 43, 155-173 (2024). [CrossRef]

- P. A. Cassier et al., Netrin-1 blockade inhibits tumour growth and EMT features in endometrial cancer. Nature 620, 409-416 (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Lengrand et al., Pharmacological targeting of netrin-1 inhibits EMT in cancer. Nature 620, 402-408 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zheng, D. Pan, The Hippo Signaling Pathway in Development and Disease. Dev Cell 50, 264-282 (2019). [CrossRef]

- S. Ma, Z. Meng, R. Chen, K. L. Guan, The Hippo Pathway: Biology and Pathophysiology. Annu Rev Biochem 88, 577-604 (2019). [CrossRef]

- J. Yu et al., Kibra functions as a tumor suppressor protein that regulates Hippo signaling in conjunction with Merlin and Expanded. Dev Cell 18, 288-299 (2010). [CrossRef]

- A. Genevet, M. C. Wehr, R. Brain, B. J. Thompson, N. Tapon, Kibra is a regulator of the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling network. Dev Cell 18, 300-308 (2010). [CrossRef]

- R. Baumgartner, I. Poernbacher, N. Buser, E. Hafen, H. Stocker, The WW domain protein Kibra acts upstream of Hippo in Drosophila. Dev Cell 18, 309-316 (2010). [CrossRef]

- J. Kremerskothen et al., Characterization of KIBRA, a novel WW domain-containing protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 300, 862-867 (2003). [CrossRef]

- L. Xiao, Y. Chen, M. Ji, J. Dong, KIBRA regulates Hippo signaling activity via interactions with large tumor suppressor kinases. J Biol Chem 286, 7788-7796 (2011). [CrossRef]

- T. Su, M. Z. Ludwig, J. Xu, R. G. Fehon, Kibra and Merlin Activate the Hippo Pathway Spatially Distinct from and Independent of Expanded. Dev Cell 40, 478-490.e473 (2017). [CrossRef]

- S. Qi et al., WWC proteins mediate LATS1/2 activation by Hippo kinases and imply a tumor suppression strategy. Mol Cell 82, 1850-1864.e1857 (2022).

- L. Wang et al., Multiphase coalescence mediates Hippo pathway activation. Cell 185, 4376-4393.e4318 (2022). [CrossRef]

- T. T. Bonello et al., Phase separation of Hippo signalling complexes. EMBO J 42, e112863 (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. M. Franklin, Z. Wu, K. L. Guan, Insights into recent findings and clinical application of YAP and TAZ in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 23, 512-525 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. Piccolo, T. Panciera, P. Contessotto, M. Cordenonsi, YAP/TAZ as master regulators in cancer: modulation, function and therapeutic approaches. Nat Cancer 4, 9-26 (2023). [CrossRef]

- I. Baroja, N. C. Kyriakidis, G. Halder, I. M. Moya, Expected and unexpected effects after systemic inhibition of Hippo transcriptional output in cancer. Nat Commun 15, 2700 (2024). [CrossRef]

- T. Moroishi et al., The Hippo Pathway Kinases LATS1/2 Suppress Cancer Immunity. Cell 167, 1525-1539.e1517 (2016).

- G. Wang et al., Targeting YAP-Dependent MDSC Infiltration Impairs Tumor Progression. Cancer Discov 6, 80-95 (2016). [CrossRef]

- X. Guo et al., Single tumor-initiating cells evade immune clearance by recruiting type II macrophages. Genes Dev 31, 247-259 (2017). [CrossRef]

- W. Kim et al., Hepatic Hippo signaling inhibits protumoural microenvironment to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 67, 1692-1703 (2018). [CrossRef]

- B. S. Lee et al., Hippo effector YAP directly regulates the expression of PD-L1 transcripts in EGFR-TKI-resistant lung adenocarcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 491, 493-499 (2017). [CrossRef]

- J. Miao et al., YAP regulates PD-L1 expression in human NSCLC cells. Oncotarget 8, 114576-114587 (2017). [CrossRef]

- M. H. Kim et al., YAP-Induced PD-L1 Expression Drives Immune Evasion in BRAFi-Resistant Melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res 6, 255-266 (2018). [CrossRef]

- H. J. Janse van Rensburg et al., The Hippo Pathway Component TAZ Promotes Immune Evasion in Human Cancer through PD-L1. Cancer Res 78, 1457-1470 (2018).

- P.C. Hsu et al., Inhibition of yes-associated protein down-regulates PD-L1 (CD274) expression in human malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Cell Mol Med 22, 3139-3148 (2018). [CrossRef]

- K. P. Burke, A. Chaudhri, G. J. Freeman, A. H. Sharpe, The B7:CD28 family and friends: Unraveling coinhibitory interactions. Immunity 57, 223-244 (2024). [CrossRef]

- N. Feldker et al., Genome-wide cooperation of EMT transcription factor ZEB1 with YAP and AP-1 in breast cancer. EMBO J 39, e103209 (2020). [CrossRef]

- F. Hammal, P. de Langen, A. Bergon, F. Lopez, B. Ballester, ReMap 2022: a database of Human, Mouse, Drosophila and Arabidopsis regulatory regions from an integrative analysis of DNA-binding sequencing experiments. Nucleic Acids Res 50, D316-D325 (2022). [CrossRef]

- K. A. Brown et al., Induction by transforming growth factor-beta1 of epithelial to mesenchymal transition is a rare event in vitro. Breast Cancer Res 6, R215-231 (2004). [CrossRef]

- A. K. Shenoy et al., Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition confers pericyte properties on cancer cells. J Clin Invest 126, 4174-4186 (2016). [CrossRef]

- F. X. Yu et al., Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell 150, 780-791 (2012). [CrossRef]

- D. Cai et al., Phase separation of YAP reorganizes genome topology for long-term YAP target gene expression. Nat Cell Biol 21, 1578-1589 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu et al., Phase separation of TAZ compartmentalizes the transcription machinery to promote gene expression. Nat Cell Biol 22, 453-464 (2020). [CrossRef]

- X. Hu et al., Nuclear condensates of YAP fusion proteins alter transcription to drive ependymoma tumourigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 25, 323-336 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu-Chittenden et al., Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes Dev 26, 1300-1305 (2012). [CrossRef]

- S. A. Mani et al., The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 133, 704-715 (2008). [CrossRef]

- A. K. H. Loe et al., YAP targetome reveals activation of SPEM in gastric pre-neoplastic progression and regeneration. Cell Rep 42, 113497 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. A. Tokamov et al., Apical polarity and actomyosin dynamics control Kibra subcellular localization and function in Drosophila Hippo signaling. Dev Cell 58, 1864-1879.e1864 (2023). [CrossRef]

- E. Martin, R. Girardello, G. Dittmar, A. Ludwig, New insights into the organization and regulation of the apical polarity network in mammalian epithelial cells. FEBS J 288, 7073-7095 (2021). [CrossRef]

- S. Song et al., A Novel YAP1 Inhibitor Targets CSC-Enriched Radiation-Resistant Cells and Exerts Strong Antitumor Activity in Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther 17, 443-454 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Q. Li et al., Lats1/2 Sustain Intestinal Stem Cells and Wnt Activation through TEAD-Dependent and Independent Transcription. Cell Stem Cell 26, 675-692.e678 (2020).

- T. Oltersdorf et al., An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 435, 677-681 (2005). [CrossRef]

- M. Konopleva et al., Mechanisms of apoptosis sensitivity and resistance to the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 10, 375-388 (2006). [CrossRef]

- M. F. van Delft et al., The BH3 mimetic ABT-737 targets selective Bcl-2 proteins and efficiently induces apoptosis via Bak/Bax if Mcl-1 is neutralized. Cancer Cell 10, 389-399 (2006).

- E. J. Morris, H. M. Geller, Induction of neuronal apoptosis by camptothecin, an inhibitor of DNA topoisomerase-I: evidence for cell cycle-independent toxicity. J Cell Biol 134, 757-770 (1996). [CrossRef]

- M. I. Walton et al., Constitutive expression of human Bcl-2 modulates nitrogen mustard and camptothecin induced apoptosis. Cancer Res 53, 1853-1861 (1993).

- F. Zanconato et al., Transcriptional addiction in cancer cells is mediated by YAP/TAZ through BRD4. Nat Med 24, 1599-1610 (2018). [CrossRef]

- P. Filippakopoulos et al., Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 468, 1067-1073 (2010). [CrossRef]

- S. Lamouille, R. Derynck, Cell size and invasion in TGF-beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition is regulated by activation of the mTOR pathway. J Cell Biol 178, 437-451 (2007). [CrossRef]

- D. Honda, M. Okumura, T. Chihara, Crosstalk between the mTOR and Hippo pathways. Dev Growth Differ 65, 337-347 (2023). [CrossRef]

- F. Zanconato et al., Genome-wide association between YAP/TAZ/TEAD and AP-1 at enhancers drives oncogenic growth. Nat Cell Biol 17, 1218-1227 (2015). [CrossRef]

- J. D. Pearson et al., Binary pan-cancer classes with distinct vulnerabilities defined by pro- or anti-cancer YAP/TEAD activity. Cancer Cell 39, 1115-1134.e1112 (2021). [CrossRef]

- M. Emaldi et al., A functional role for glycosylated B7-H5/VISTA immune checkpoint protein in metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. iScience 27, 110587 (2024).

- N. R. Kastan et al., Development of an improved inhibitor of Lats kinases to promote regeneration of mammalian organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119, e2206113119 (2022). [CrossRef]

- N. Kastan et al., Small-molecule inhibition of Lats kinases may promote Yap-dependent proliferation in postmitotic mammalian tissues. Nat Commun 12, 3100 (2021). [CrossRef]

- T. T. Tang et al., Small Molecule Inhibitors of TEAD Auto-palmitoylation Selectively Inhibit Proliferation and Tumor Growth of. Mol Cancer Ther 20, 986-998 (2021). [CrossRef]

- W. Wang et al., AMPK modulates Hippo pathway activity to regulate energy homeostasis. Nat Cell Biol 17, 490-499 (2015). [CrossRef]

- J. S. Mo et al., Cellular energy stress induces AMPK-mediated regulation of YAP and the Hippo pathway. Nat Cell Biol 17, 500-510 (2015). [CrossRef]

- M. Overholtzer et al., Transforming properties of YAP, a candidate oncogene on the chromosome 11q22 amplicon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 12405-12410 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Q. Y. Lei et al., TAZ promotes cell proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition and is inhibited by the hippo pathway. Mol Cell Biol 28, 2426-2436 (2008). [CrossRef]

- S. W. Chan et al., A role for TAZ in migration, invasion, and tumorigenesis of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 68, 2592-2598 (2008).

- B. Zhao et al., TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev 22, 1962-1971 (2008). [CrossRef]

- S. Moleirinho et al., KIBRA exhibits MST-independent functional regulation of the Hippo signaling pathway in mammals. Oncogene 32, 1821-1830 (2013). [CrossRef]

- C. Kudo-Saito, H. Shirako, T. Takeuchi, Y. Kawakami, Cancer metastasis is accelerated through immunosuppression during Snail-induced EMT of cancer cells. Cancer Cell 15, 195-206 (2009). [CrossRef]

- S. O. Imodoye, K. A. Adedokun, EMT-induced immune evasion: connecting the dots from mechanisms to therapy. Clin Exp Med 23, 4265-4287 (2023). [CrossRef]

- L. Chen et al., Metastasis is regulated via microRNA-200/ZEB1 axis control of tumour cell PD-L1 expression and intratumoral immunosuppression. Nat Commun 5, 5241 (2014).

- K. Abiko et al., IFN-γ from lymphocytes induces PD-L1 expression and promotes progression of ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 112, 1501-1509 (2015). [CrossRef]

- M. Mandai et al., Dual Faces of IFNγ in Cancer Progression: A Role of PD-L1 Induction in the Determination of Pro- and Antitumor Immunity. Clin Cancer Res 22, 2329-2334 (2016). [CrossRef]

- A. Garcia-Diaz et al., Interferon Receptor Signaling Pathways Regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 Expression. Cell Rep 19, 1189-1201 (2017). [CrossRef]

- A. A. Davis, V. G. Patel, The role of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker: an analysis of all US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer 7, 278 (2019). [CrossRef]

- A. S. Martin et al., VISTA expression and patient selection for immune-based anticancer therapy. Front Immunol 14, 1086102 (2023). [CrossRef]

- K. Mulati et al., VISTA expressed in tumour cells regulates T cell function. Br J Cancer 120, 115-127 (2019). [CrossRef]

- H. M. Ta et al., LRIG1 engages ligand VISTA and impairs tumor-specific CD8. Sci Immunol 9, eadi7418 (2024). [CrossRef]

- J. Liu et al., Immune-checkpoint proteins VISTA and PD-1 nonredundantly regulate murine T-cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 6682-6687 (2015). [CrossRef]

- N. Mehta et al., An engineered antibody binds a distinct epitope and is a potent inhibitor of murine and human VISTA. Sci Rep 10, 15171 (2020). [CrossRef]

- T. K. Kim et al., PD-1H/VISTA mediates immune evasion in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest 134 (2024). [CrossRef]

- E. Schaafsma et al., VISTA Targeting of T-cell Quiescence and Myeloid Suppression Overcomes Adaptive Resistance. Cancer Immunol Res 11, 38-55 (2023). [CrossRef]

- P. G. Sasikumar et al., PD-1 derived CA-170 is an oral immune checkpoint inhibitor that exhibits preclinical anti-tumor efficacy. Commun Biol 4, 699 (2021). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).