1. Introduction

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are rapidly improving machines’ ability to process and understand visual data [

1]. In addition, AI also promote progress in fields like robotics and education [

2]. These developments are creating new opportunities to support accessible human-computer interaction, especially for individuals with disabilities [

3]. One of the main objectives of assitive technology is supporting individuals with upper-limb impairments [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This group includes people with limb amputations, neuromuscular disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, spinal cord injuries, and congenital limb differences. All of which can significantly hinder the use of conventional input devices like the mouse or keyboard.

According to [

9], as of 2019, there were approximately 552.45 million people living with traumatic amputations. Additionally, nearly 33,000 people in the U.S. are currently living with ALS, and that number is projected to reach 36,000 by 2030 [

10]. These conditions make it difficult or nearly impossible for individuals to use a computer mouse. However, the ability to move the head and eyes is often retained, even in individuals living with severe disabilities; therefore, computer interfaces based on head or eye movement are commonly employed as alternative input methods.

Recognizing this issue, many researchers have proposed solutions to support people with disabilities in accessing and interacting with computers effectively. Chen [

11] invented a head-controlled computer mouse for people with disabilities using tilt sensors. This system includes two tilt sensors embedded in a headset to detect head position: one sensor detects horizontal movement to control the mouse left or right, while the other detects vertical movement to move the mouse up or down. A touch switch was also designed to allow users to gently tap their cheek to perform a click action. Some studies [

12,

13] employed a dual-axis accelerometer to control the mouse. Another approach used a combination of a gyro sensor and an optical sensor to perform clicking actions [

14]. Additionally, Pereira et al. [

15] developed a system for people with disabilities to control a computer mouse. This system includes a camera, computer software, and a target mounted on the front of a cap worn on the user's head, simulating cursor movements. Lin et al. [

16] combined eye tracking and head gestures, using a light source mounted on the user. These methods have demonstrated particularly fast and accurate results. However, they all rely on sensor devices. This increases deployment costs, making it difficult for users in low-income areas or those without access to advanced technology. Furthermore, installing and calibrating sensors often requires a certain level of technical skill, which not all users may possess. Additionally, wearing sensor devices on the head for extended periods can cause discomfort, neck fatigue, or a sense of heaviness, negatively affecting the user experience.

In addition to solutions that utilize specialized sensors, using standard RGB cameras such as built-in webcams on laptops has also become a promising approach. With the rapid advancement of computer vision algorithms, RGB cameras not only help reduce deployment costs but also offer a more convenient and accessible contactless mouse control experience. Earlier solutions used classic computer vision techniques such as template matching [

17,

18], or color-based segmentation [

19,

20], presented a "camera mouse" system that uses a timer for left-click, a technique later known as 'dwell click', and eye blinking for right-click. Previous studies [

4,

21] combined head motion with voice commands to trigger mouse clicks. In another direction, [

22] used a camera to analyze head orientation for cursor control, integrating eye blinks to execute commands. Recently, many solutions rely on deep learning to directly map visual input to screen coordinates [

23,

24] or to predict facial landmarks and expressions for interaction control [

6,

8,

25].

While many approaches have been proposed to help individuals with disabilities control computers using camera input, most still suffer from response latency, primarily due to noisy visual input and inefficient signal processing filters. Furthermore, recent systems typically rely on a limited set of input modalities and support only a few discrete facial gestures (e.g., smiling, mouth opening, eyebrow raising), which restricts flexibility and user engagement [

6,

8]. These expressive gestures can also interfere with precise cursor control, as they are not always distinguishable from involuntary facial movements during natural interaction. Moreover, many existing systems treat input modalities in isolation and lack flexible multimodal integration. A promising direction is to incorporate contextual cues, such as using visual detection of mouth opening to validate voice commands, in order to reduce false positives. However, this form of cross-modal verification remains underutilized in prior work [

4,

26].

To overcome these limitations, we propose a novel hands-free control system, namely 3-Modal Human-Computer Interaction (3M-HCI), that integrates three input modalities: head movement with facial expressions, voice commands, and eye gaze. A new adaptive filtering mechanism is introduced to suppress signal noise while maintaining low-latency responsiveness. Furthermore, the mapping strategy from input signals to cursor movements is redefined to improve accuracy. In addition, cross-modal information is used to enhance the system’s overall reliability and precision.

The main contribution of this work is the development of a low-cost, responsive hands-free interface that enables individuals with upper-limb disabilities to interact with computers using head movements, facial expressions, voice commands, and eye gaze. The proposed system is lightweight and customizable, designed to run efficiently even on low-end hardware. By ensuring compatibility with standard hardware, the system improves access and interaction for users with motor impairments. To evaluate the system, two types of tests were conducted: (a) functional tests under various technical and environmental conditions, and (b) user evaluations to assess usability, responsiveness, and perceived effectiveness.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the system architecture and input modalities.

Section 3 outlines the materials used and the evaluation methodology.

Section 4 presents experimental results and discussions. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and suggests future research.

2. System Architecture

The 3-Model Human-Computer Interaction (3M-HCI) system employs a callback-based architecture that fundamentally separates processing logic from user interface components, ensuring optimal performance, maintainability, and scalability. The core processing pipeline operates independently in separate threads, with results delivered to the GUI for display. To achieve maximum efficiency, the system implements a multi-threaded architecture within a single process, with mechanisms for safe thread coordination and termination. By using primarily I/O-bound operations, the system maintains significantly lower resource overhead compared to existing solutions.

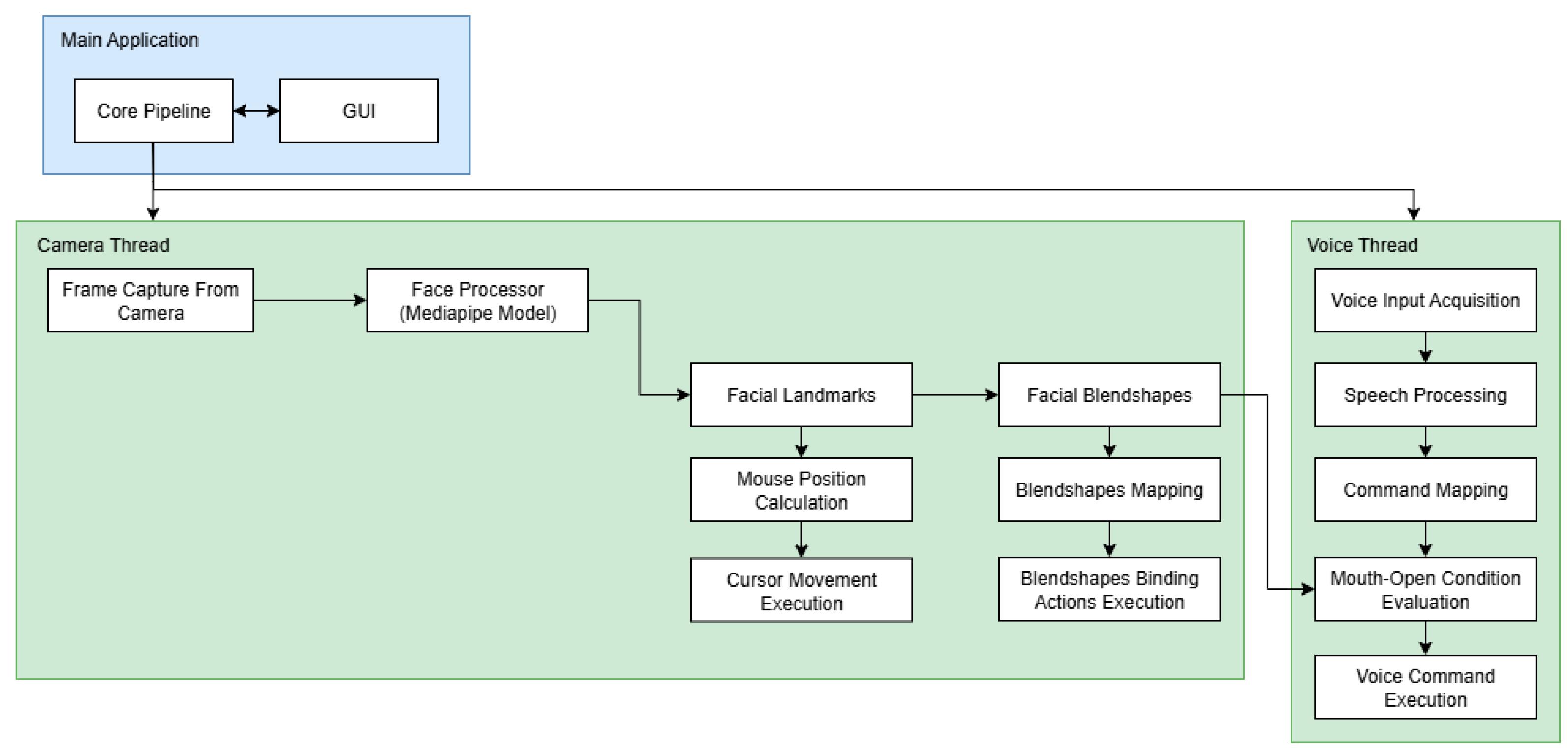

The main processing pipeline operates through synchronous and asynchronous callbacks as illustrated in Figure 1. The computer vision thread continuously captures frames from the camera input. Through the callback mechanism, each frame is delivered to the face processor module. The face processor offers two processing modes: the IMAGE mode processes each frame separately and synchronously, while the smooth mode handles frames asynchronously. Upon successful processing, the extracted facial landmarks and blendshape data are forwarded through the pipeline to calculate and execute mouse movements as well as keyboard actions.

Figure 1.

The core processing pipeline of the system.

Figure 1.

The core processing pipeline of the system.

The voice processor functions as an independent module running in its own dedicated thread. It captures microphone input and processes it through its recognition engine to identify pre-configured voice commands. To enhance user experience and prevent false activations from external audio sources, the system incorporates an intelligent gating mechanism that cross-references facial expression data from the face processor module before executing voice commands.

This architecture demonstrates significant optimization advantages compared to existing solutions like Google Project Gameface [

6], which utilizes a busy-waiting pipeline that tightly couples GUI and processing components. Google's implementation continuously captures and processes images at extremely high frequencies (sub-millisecond intervals), resulting in substantial resource consumption and redundant frame processing. In contrast, our event-driven approach with controlled frame rates delivers superior resource efficiency while maintaining real-time responsiveness. The detailed implementation of each module is described in the subsequent sections.

2.1. Video Processing Module

2.1.1. Face Processing

The Face Processing modules’ main function is to detect and track the user’s face and return facial landmarks, eye gaze, and expressions, which makes them the most critical component in the entire system pipeline. The face processing algorithm must meet several requirements: it should be fast, deliver high accuracy, and ideally operate efficiently without requiring a GPU.

Previous systems [

4] have typically used the Dlib library [

27], the Haar Cascade algorithm [

28], or custom-built CNNs for face detection and tracking [

23,

24,

29]. Recent systems [

6,

8] increasingly adopt MediaPipe [

30] due to its superior performance and the wide range of built-in features it provides. We compare several lightweight face processing algorithms. All algorithms below were evaluated on a single laptop with a Ryzen 5 5500U CPU, 12 GB RAM, and AMD Radeon Vega 7 integrated graphics to ensure consistent performance comparison. The result can be found in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Face processing algorithm comparison.

Table 1.

Face processing algorithm comparison.

Algorithm/

Library |

Number

of

Landmarks |

Detection Time

(second) |

Detection Rate1

|

Facial Expression |

Iris

Tracking |

| Dlib [27] |

68 |

0.036 |

0.78 |

Some facial expressions can be computed manually2

|

No |

| Mediapipe [30] |

478 |

0.0037 |

1 |

52 built-in blendshapes |

Yes |

| Haar Cascade [28] |

0 |

0.0056 |

0.65 |

No |

No |

| MTCNN [31] |

5 |

0.215 |

1 |

No |

No |

| YuNet [32] |

5 |

0.026 |

0.93 |

No |

No |

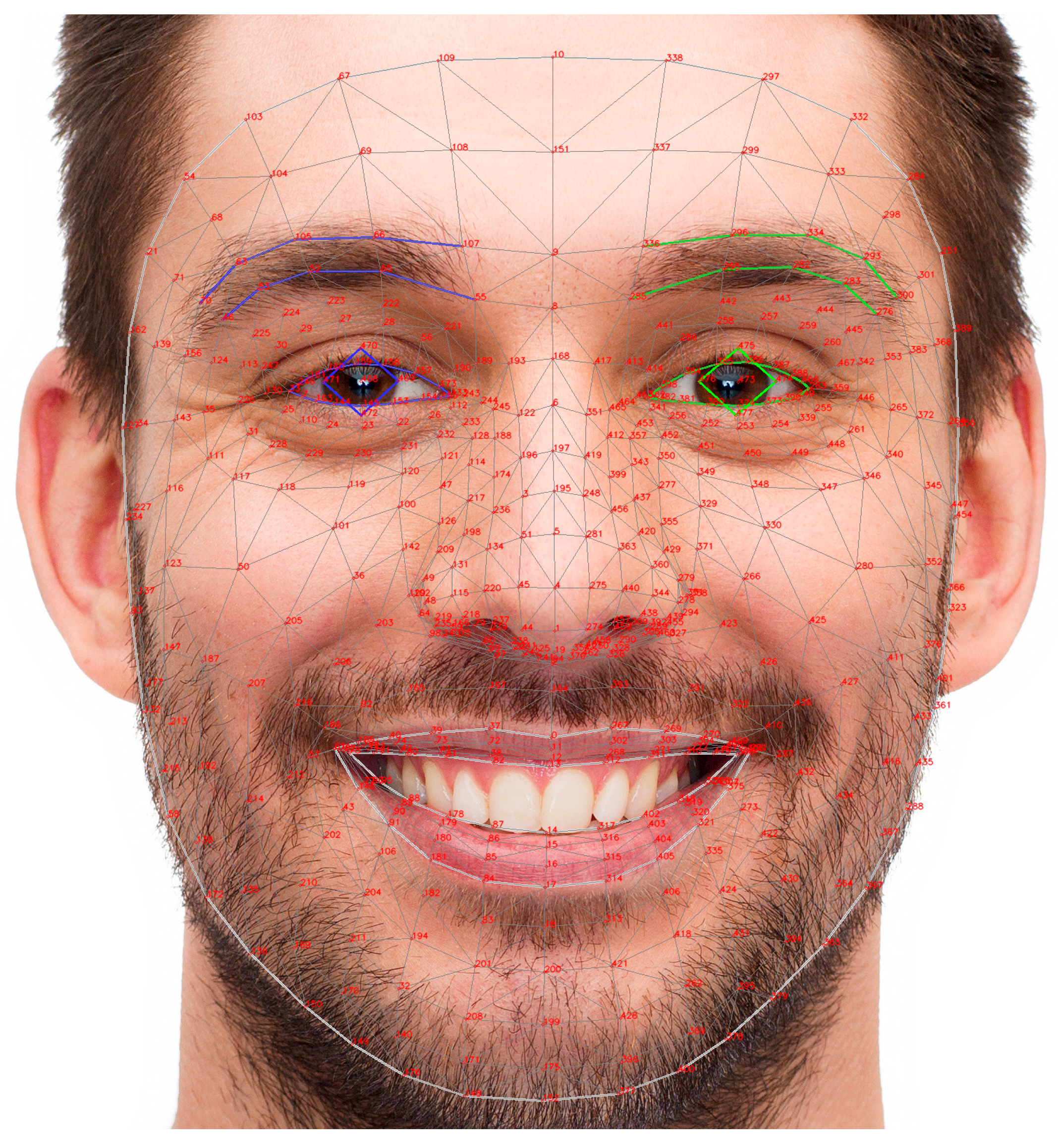

Based on the comparison results shown in the table above, we decided to use MediaPipe as the core tool for developing our system. MediaPipe [

30] provides 478 facial landmarks (

Figure 2), including key regions such as the eyes, eyebrows, mouth, nose, and jawline, which are essential for precise facial expression analysis.

Figure 2.

Mediapipe 478 landmarks. Each landmark point corresponds to a specific part of the face.

Figure 2.

Mediapipe 478 landmarks. Each landmark point corresponds to a specific part of the face.

2.1.2. Mapping Feature to Mouse Coordinate

Camera-based head-mouse systems typically use landmarks such as the nose tip [

4,

8], forehead [

6], or mouth [

19] as anchors. However, landmark instability during facial expressions can introduce unwanted cursor drift. For example, raising an eyebrow, as seen in Google’s Project GameFace, can shift the forehead anchor, while actions like nose sneer or performing gestures such as “mouse left” and “mouse right” can alter the nose tip position, leading to unintentional pointer movement. A simple way to mitigate this issue is to avoid using facial expressions that can distort the anchor points altogether. Therefore, our solution is to use the two inner eye corners (medial canthi) as anchor points instead. After thorough testing, we found that the medial canthi remain stable across various facial expressions. Therefore, we chose them as reliable reference points for pointer movement (

Figure 3). The movement vector formed by tracking these two inner eye corners is then converted into mouse pointer movement signals.

Formally, let

PL = (

XL, YL) and

PR = (

XR, YR) be the coordinates of the left and right medial canthus, respectively. We computed the midpoint at frame t:

Finally, we have cursor displacement vector

Vt:

Figure 3.

Two inner eye corners (p133 and p362 in Mediapipe).

Figure 3.

Two inner eye corners (p133 and p362 in Mediapipe).

Displacement vector Vt serves as the raw cursor moving signal in our system.

2.1.3. Adaptive Movement Signal Filtering and Acceleration

With signals measured from sensors or cameras (since a camera itself is a type of sensor), there is always some noise present in the data. To eliminate this noise, we apply filtering techniques. Depending on the characteristics of the signal, different filtering methods can be used, such as: i) for signals with significant “salt-and-pepper” noise, a median filter can be applied to remove outliers; ii) for signals affected by Gaussian noise, a low-pass filter or a Gaussian filter may be used.

In our specific case, the movement signals extracted from facial landmarks often contain Gaussian noise. This causes the cursor movement to appear jittery. To address this issue, some systems use a simple region-based technique, where a virtual window is overlaid on the user’s face and the cursor only moves when the tracked landmark crosses the boundary of this window [

4]. Additionally, previous systems have applied low-pass filters as a basic solution to smooth the pointer motion [

8,

17]. A more optimized approach is to use a Hamming filter, which offers better frequency response characteristics [

6].

Although these techniques help smooth the cursor movement, they can also affect the pointer speed and responsiveness. Conventional low-pass filters have a fixed cutoff frequency, which creates a trade-off between smoothness and responsiveness. If the cutoff is too low, the cursor becomes stable but sluggish; if it is too high, unwanted jitter may persist. To address this limitation, we employed the 1€ filter [

33], an adaptive filter that dynamically adjusts its cutoff frequency according to the signal's speed. This allows the system to remain smooth during slow movements while still being responsive during rapid changes. Note that, instead of applying the 1€ filter directly to the

x and

y coordinates separately, we apply the 1€ filter to the cursor displacement magnitude to get the smoothing factor

α. This approach avoids the issue of having different cutoff frequencies on each axis, which could cause asynchronous pointer behavior.

We define

to be the cursor displacement magnitude, and using 1€ filter to get the smoothing factor:

After that, we calculate the filtered displacement vector, using adaptive smoothing factor

:

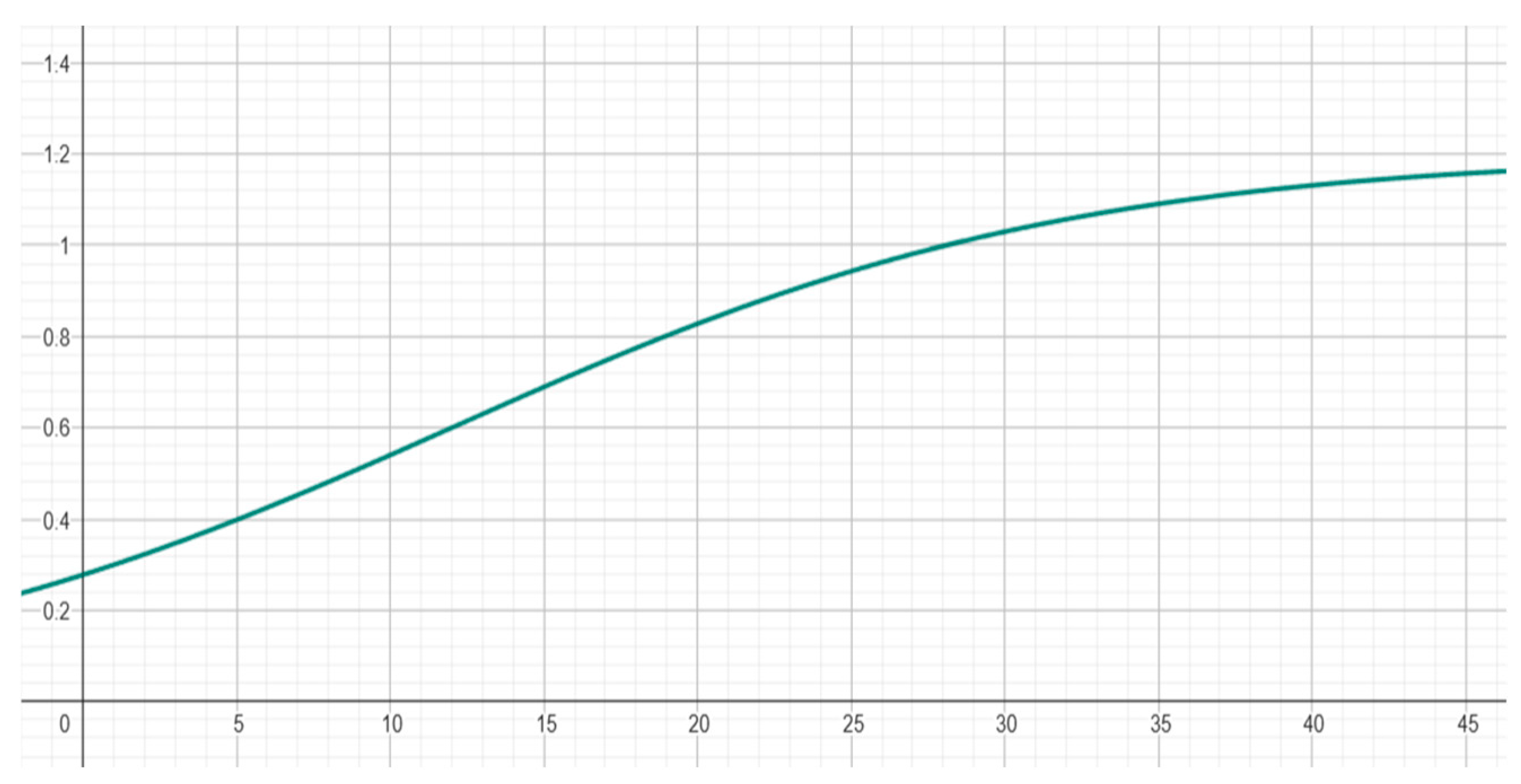

Finally, we apply a pointer acceleration function to improve the responsiveness and usability of the system. This allows small head movements to result in fine cursor control, while larger or faster movements produce quicker pointer displacement, enhancing both precision and efficiency. Pointer acceleration is typically based on sigmoid functions. Previous work [

6,

34,

35,

36] has demonstrated that sigmoid-based pointer acceleration achieves smoother transitions between precise and rapid movements, while avoiding excessive jitter or drift. It also improves ergonomics and precision of the system. We adopted the following function:

Where: K controls the maximum gain, determining how fast the pointer can move at high speeds; slope defines the steepness of the transition between low and high gain; larger values make the transition sharper; offset sets the inflection point on the input axis, i.e., the point at which the gain starts to increase significantly.

In our system, we set K = 1.2, slope = 0.1, and offset = 12. The resulting acceleration curve is illustrated in Figure 4, showing a smooth transition from low to high gain as input speed increases.

Figure 4.

Acceleration curve.

Figure 4.

Acceleration curve.

2.1.4. Mapping Facial Expressions to Mouse and Keyboard Actions

Early studies employed sensors [

11,

14] or dwell-click mechanisms [

20], combined with a limited set of simple actions or expressions [

4,

19] to trigger mouse events. More recent approaches have shifted toward using more intuitive and user-friendly expressions such as smiling, raising eyebrows, or opening the mouth to enhance usability and reduce fatigue [

4,

6,

8]. However, these systems typically utilize only a small number of facial expressions [

4,

8], as some expressions have been reported to be difficult to perform or maintain and may cause facial fatigue. In addition, certain expressions can be easily confused with one another, reducing the reliability of the input [

6,

25].

A straightforward way to address this issue is to use only easily recognizable and distinguishable facial expressions that are less likely to be confused with others. However, this approach inherently limits the number of distinct actions the system can support. To overcome this limitation, we introduce a priority-based triggering mechanism, which favors less distinguishable expressions over more easily recognizable ones when multiple expressions are detected simultaneously. By using this mechanism, our system supports a wider range of actions compared to existing systems (Table 2), while also reducing false positives and confusion.

Table 2.

Comparison of our system with facial expression control interfaces.

Table 2.

Comparison of our system with facial expression control interfaces.

| System |

#Facial

Expression |

Mouse Control |

Keyboard Control |

System Control |

Triggering

Mechanism |

| EMKEY [19] |

1 |

- |

- |

x |

Predefined

Threshold |

| CameraMouseAI [22] |

2 |

x |

- |

- |

User-Defined Threshold |

| Project Gameface [23] |

8 |

x |

x |

- |

User-Defined Threshold |

| Zelinskyi et al. [33] |

8 |

x |

- |

- |

Predefined

Threshold |

| 3M-HCI (Ours) |

13 |

x |

x |

x |

User-Defined Threshold with Priority |

Moreover, in our system, we also utilized directional eye gaze (left, right, up, down) as a form of expressive input, similar to facial expressions.

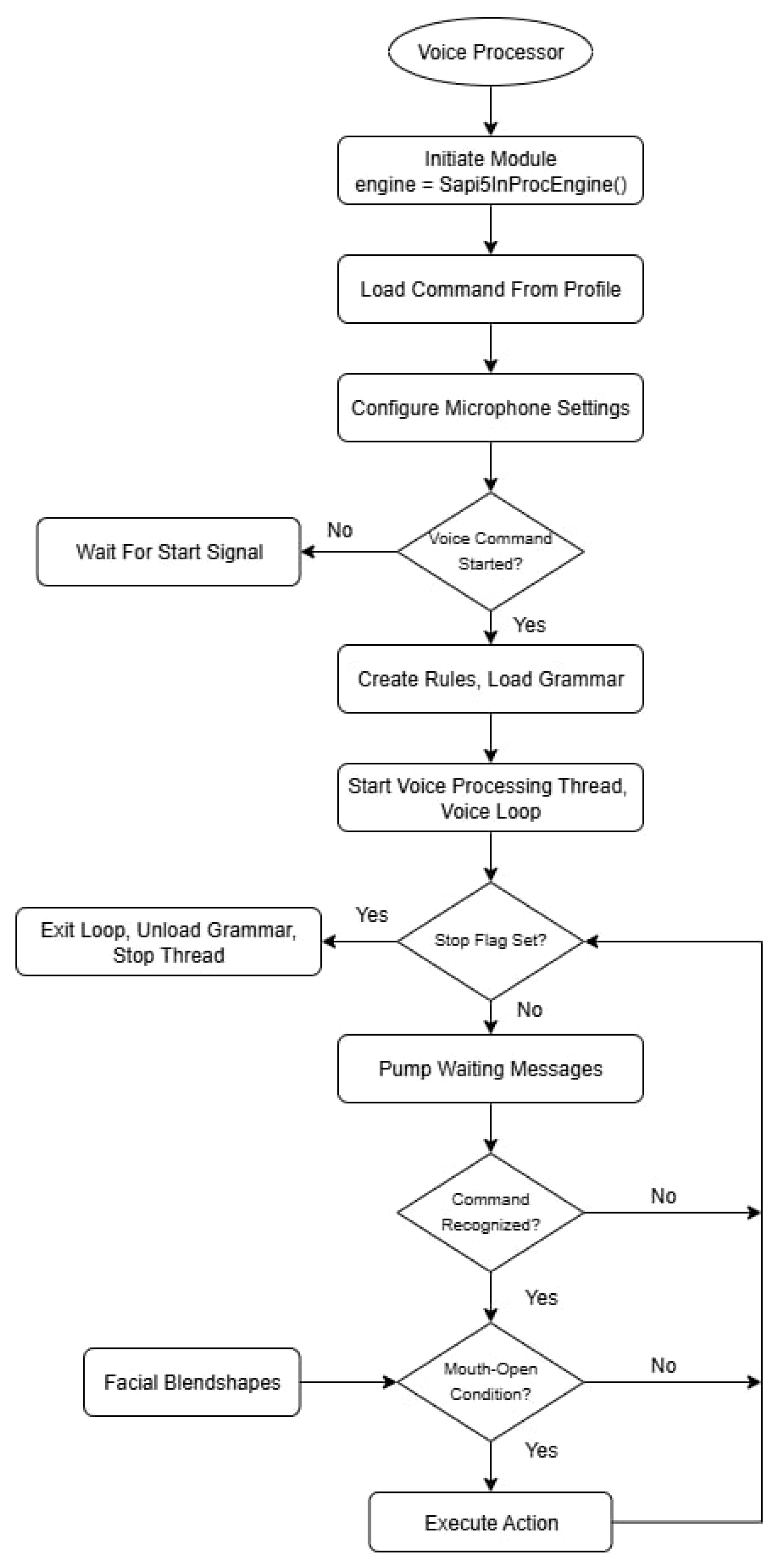

2.2. Voice Processing Module

The Voice Processing Module utilizes command recognition to handle basic interactive instructions and accessibility controls. It serves as a complementary input method to the facial expression control system, providing users with multiple interaction modalities. The module should use a pretrained model, support offline functionality, and offer high processing speed. To meet these criteria, we employ Microsoft’s native Speech API (SAPI5) [

37] via the Dragonfly library. SAPI5 delivers consistent performance and low latency, with all processing performed locally. This ensures that the feature operates without requiring an internet connection, thereby enhancing privacy and system reliability.

Figure 5 illustrates the general execution flow of the speech recognition module.

Figure 5.

Voice Processor Architecture.

Figure 5.

Voice Processor Architecture.

The Voice Processor Module creates a self-contained, thread-safe service that listens for user-defined voice commands. When a command is recognized by the SAPI5 engine, it executes the corresponding keyboard or mouse action via the pyautogui. Furthermore, it interfaces with other modules within the application, allowing voice commands to modify their behavior. This multimodal approach also enhances the user experience. For instance, by implementing a check to see if the user's mouth is open during command recognition, the system can avoid misinterpreting external ambient sounds as commands, leading to more reliable activation. Voice commands can also be used to dynamically adjust mouse movement speed, enabling users to fine-tune control in real time without relying on manual input.

3. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the development environment and the methodology used to evaluate the performance and usability of our multimodal interaction system. The evaluation comprises two types of tests. The first is an experimental test designed to examine system stability and responsiveness under various environmental and hardware conditions, including different CPU generations, operating systems, lighting environments, and background noise. The purpose is to determine the minimum requirements necessary for smooth operation. The second test involves task-based usability testing, in which users are asked to perform a series of predefined actions such as cursor movement and target selection. Objective performance metrics, including latency, accuracy, jitterness, and task completion time, are recorded and compared across systems. In addition, we conducted a short survey to collect subjective feedback from participants who had experienced all three systems, with the results presented in

Section 4.This approach allows for a comprehensive analysis of both technical efficiency and user experience.

3.1. Development Platform

We used two different laptops during the development process to ensure stable software performance under varying hardware conditions. The first laptop was equipped with a Ryzen 5 5500U CPU, 12 GB RAM, AMD Radeon Vega 7 integrated graphics, a built-in 720p 30fps camera, and an integrated microphone. The second laptop featured an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-13650HX CPU, 16 GB RAM, a dedicated NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU with 8 GB DDR6 VRAM, a built-in 720p 15fps camera, and an integrated microphone.

The system was developed through iterative prototyping, combined with regular internal testing and feedback from university instructors and experts with experience in assistive technologies. This feedback loop allowed us to continuously improve the system while keeping it accessible and practical. To implement our application, we chose Python as the primary programming language due to its extensive ecosystem, cross-platform compatibility, and active developer community. Python also simplifies rapid prototyping and integration with computer vision and audio processing tools, which are central to our system. The key Python libraries utilized include: i) OpenCV for video capture and preprocessing; ii) Mediapipe for extracting facial landmarks and facial expression analysis; iii) Customtkinter for building modern and customizable graphical user interfaces (GUIs); iv) dragonfly2 for a voice control framework that maps spoken commands to computer actions; v) pyautogui for accessing the mouse and keyboard functionalities; and vi) numpy for efficient numerical computations.

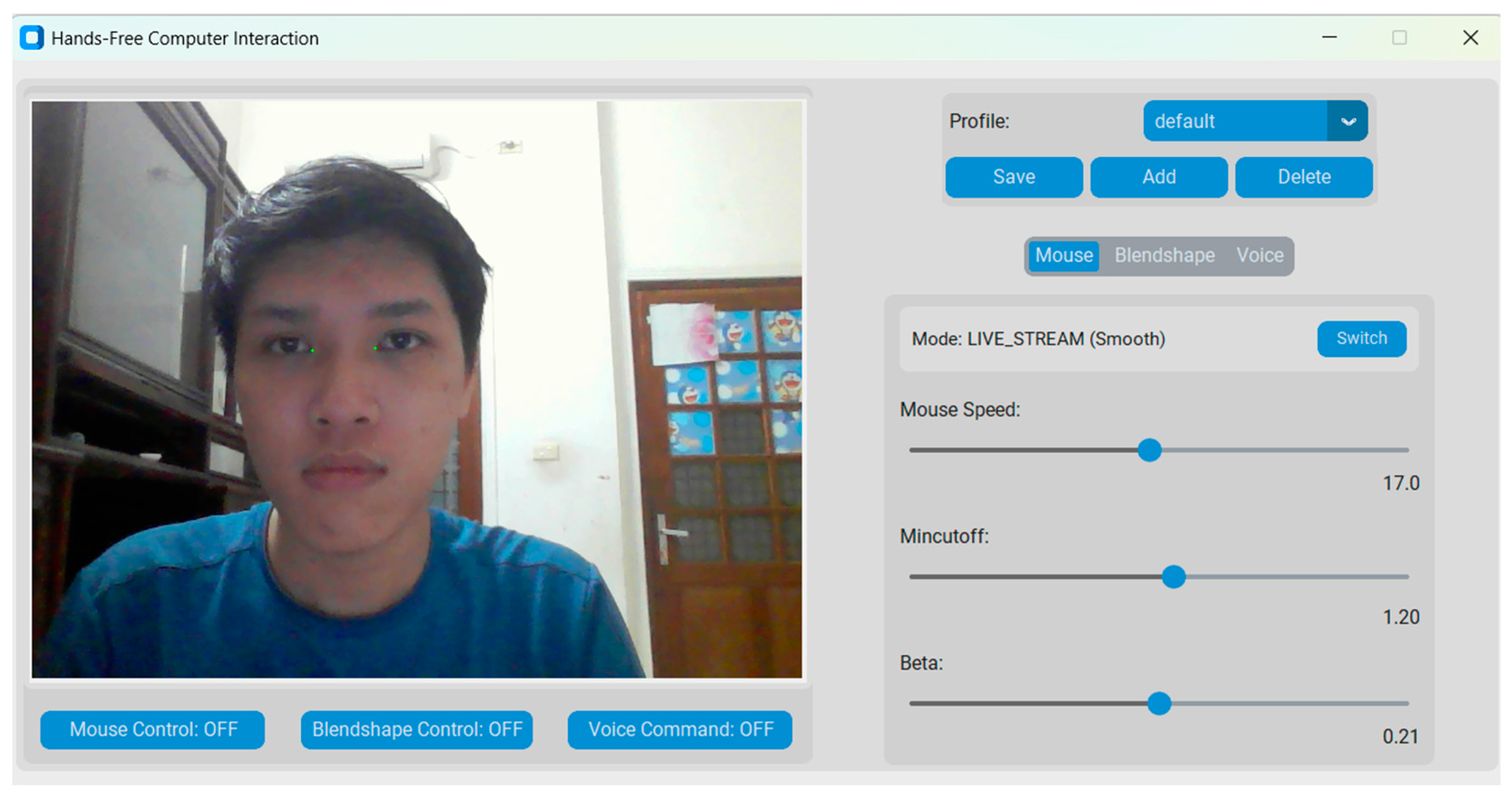

Figure 6.

3M-HCI Graphical User Interfaces built with Customtkinter.

Figure 6.

3M-HCI Graphical User Interfaces built with Customtkinter.

3.2. Testing Methodology

Following the evaluation of methodology proposed in [

4], we assess the minimum operating requirements of our system under various environmental and technical conditions, such as lighting, background noise, and hardware configurations, as follows: a) different environmental lighting conditions; b) more than one face detected by the camera; c) background noise; and d) different hardware and software features of the computer. In addition to these tests, we also conduct a task-based usability testing with existing systems, in order to highlight the effectiveness of the improvements proposed in our study: a) jitterness; b) responsiveness (task completion time); and c) accuracy.

Before performing the tasks, participants were given time to freely explore and adjust the mouse control system to ensure maximum comfort. They were instructed to select two facial expressions of their choice and assign them to left and right click actions, based on what they found most intuitive and easy to perform. Once these settings were configured, participants received clear instructions on how to interact with the testing application.

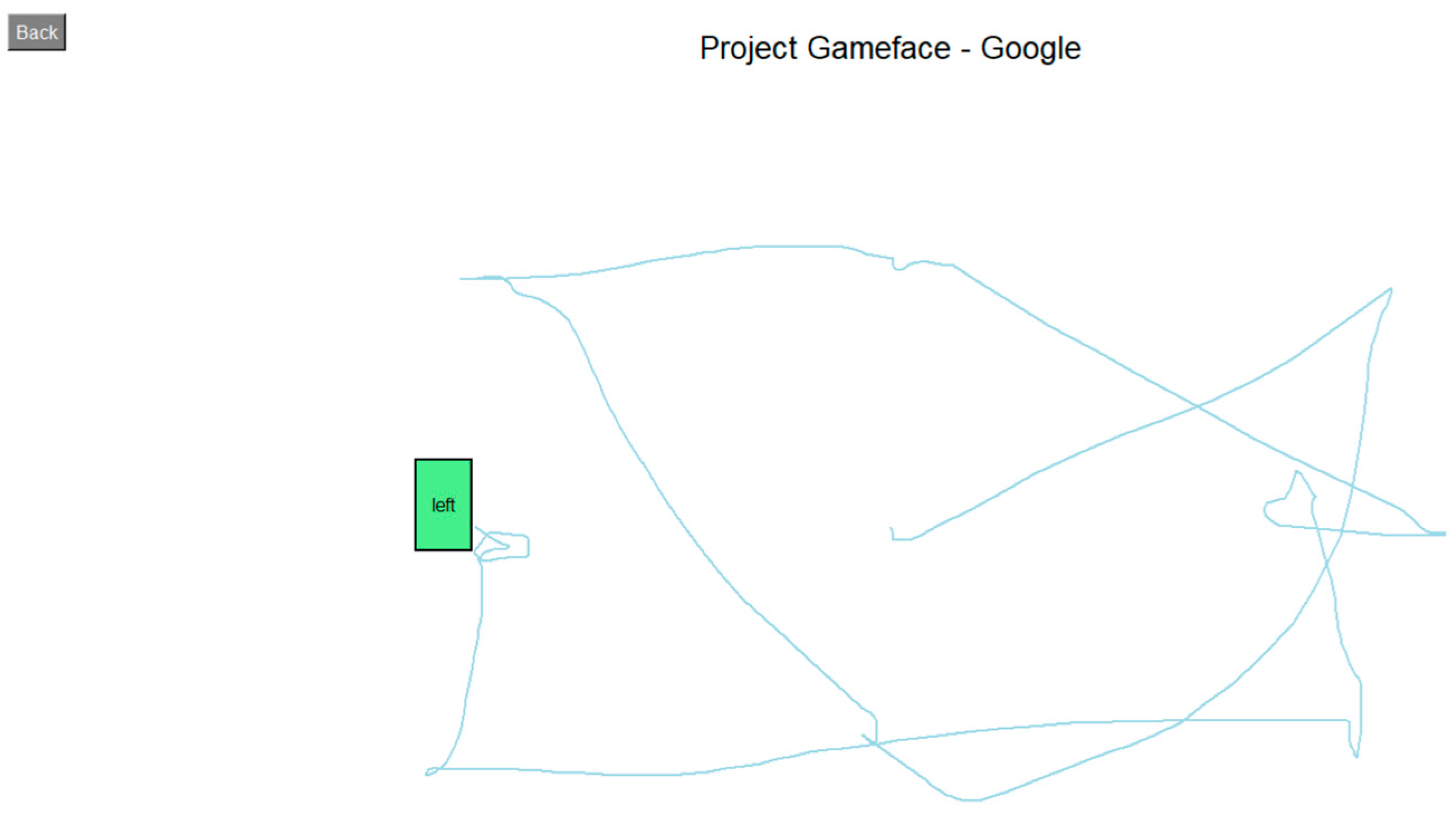

The first task involved a sequence-based interaction test, where users were required to move the cursor to predefined targets on the screen, perform either a left or right click as instructed, and proceed to the next target (Figure 7). This process continued until all targets were completed. The task was used to assess accuracy and responsiveness, based on metrics such as completion time and cursor deviation.

Figure 7.

Moving and clicking task.

Figure 7.

Moving and clicking task.

The second task required users to keep their head still for a fixed duration while the system was running. This allowed us to measure unintended cursor movement or drift, providing insight into the system’s stability when idle.

Finally, a short post-test survey was conducted to gather subjective feedback from users who had experienced all three systems (Table 3). All questions are evaluated on a numeric rating scale from 1 (Very Bad) to 10 (Excellent). The results of this evaluation, as well as the code and configurations used in the testing application, are available in our public GitHub repository.

Table 3.

List of survey questions.

Table 3.

List of survey questions.

| Question |

Description |

| Q1 |

Does it take a lot of time to master the application? |

| Q2 |

Is the response of left/right mouse click fast? |

| Q3 |

Is the cursor movement responsive? |

| Q4 |

Is it difficult to click the left/right mouse button? |

| Q5 |

Is it difficult to move the cursor precisely? |

| Q6 |

Is it difficult to move the cursor vertically? |

| Q7 |

Is it difficult to move the cursor horizontally? |

| Q8 |

Does moving the cursor cause fatigue? |

| Q9 |

Do you think this mouse system can be applied for people with disabilities? |

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Robustness Testing Under Environmental and Hardware Variations

We evaluate the system’s functionality and performance under varied lighting, multiple faces, and different hardware and operating systems, as well as identify the minimum hardware and environmental requirements necessary for stable operation.

4.1.1. Lighting Condition Test

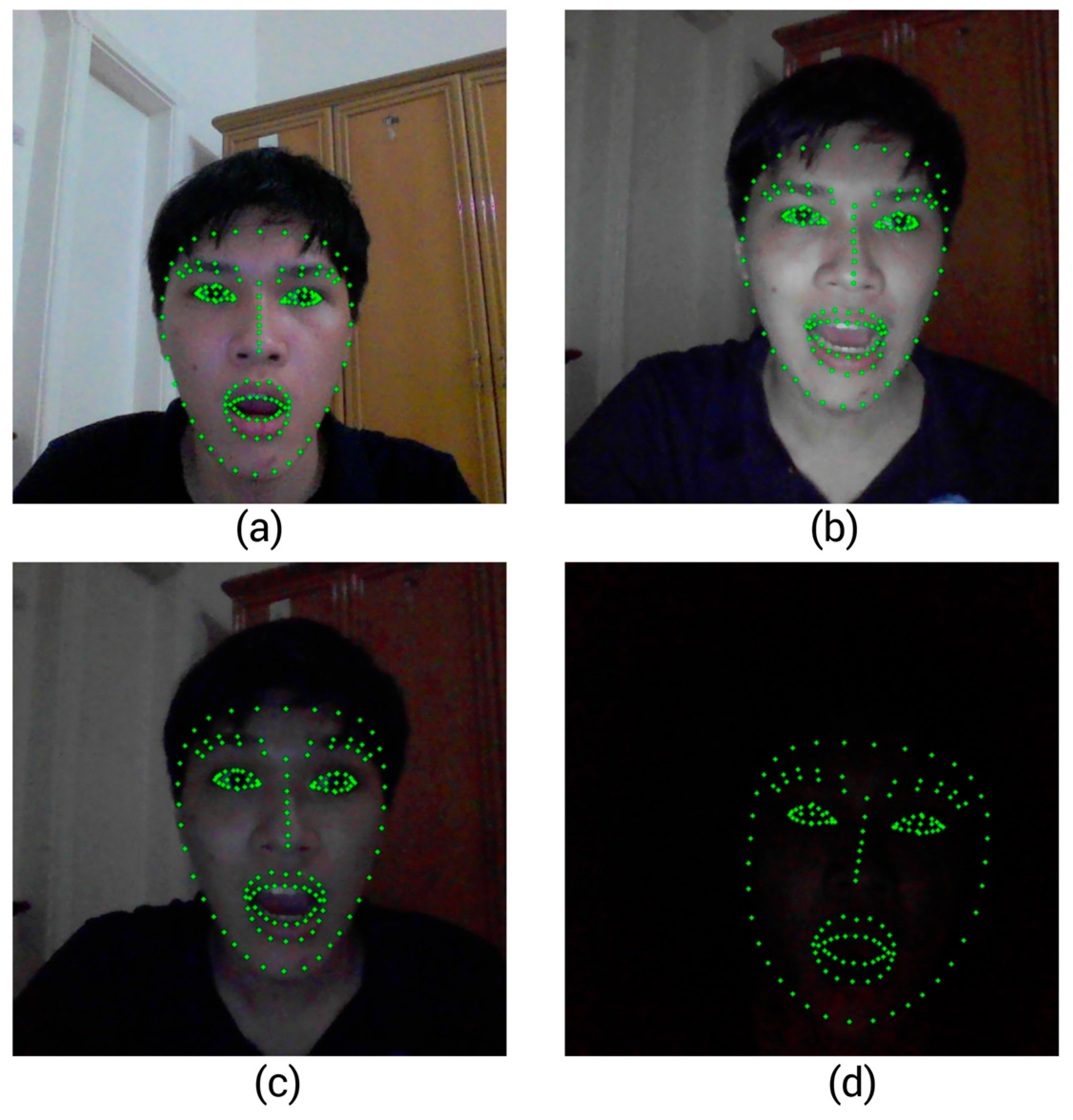

To assess the robustness of 3M-HCI under real-world usage, we conducted experiments in four different lighting environments, with corresponding results shown in Figure 8 (a–d). In each scenario, we visualized the 147 facial landmarks used by MediaPipe Face Mesh to detect expressions, enabling a detailed qualitative assessment of detection stability under varying illumination conditions. From our experiments, we can conclude that:

Bright Environment (Figure 8a, 8b): Whether in a brightly lit room or a dim room with high screen brightness, the system performed flawlessly. Facial landmarks were immediate and accurate. Mouse control operated smoothly without any jitter or delay. This represents the optimal environment for system usage.

Dim Room with Medium Screen Brightness (Figure 8c): Under significantly darker conditions, where only moderate screen brightness was present, the system remained functional. Facial landmarks still worked, but occasional instability in mouse movement was observed. The system was still usable with minor degradation.

Near-total Darkness with Low Screen Brightness (Figure 8d): In the most extreme case, with no external light and very low screen brightness, the system struggled. Although the Mediapipe framework could still detect the facial landmarks. However, the detection was inconsistent and unreliable. Landmarks often flickered or were lost entirely, making interaction with the system ineffective in this condition

Figure 8.

Mediapipe facial landmarks detection in different light conditions.

Figure 8.

Mediapipe facial landmarks detection in different light conditions.

From the experiments above, we conclude that the most critical factor for the system's performance is the clarity of the captured facial image. While ambient lighting conditions have a limited impact on the overall outcome, ensuring a well-defined face is essential. Notably, MediaPipe demonstrated impressive robustness. It was able to detect facial landmarks even in extremely low-light scenarios where the human eye struggles to distinguish facial features.

4.1.2. Multiple Faces in a Frame

This test evaluates Mediapipe’s behavior when multiple faces appear in the frame. When configured to detect only a single face, Mediapipe selects the one it detects with the highest confidence. In practice, this is often the face closest to the camera, which typically belongs to the user. However, the most confidently detected face is not always the intended user’s face, especially in dynamic or crowded environments. Our experiments show that when two faces are present in the frame, Mediapipe may occasionally select the one farther from the camera, which disrupts the system’s operation.

A simple strategy to address this issue is to enable Mediapipe’s multi-face detection mode. In this configuration, the system detects all visible faces and compares them to the face identified in the previous frame, selecting the one with the most consistent position or landmark pattern. While this improves the accuracy of user tracking in multi-face scenarios, it also introduces a higher computational load, which may reduce real-time performance, particularly on lower-end devices. For this reason, we did not adopt this approach in our implementation, as it caused noticeable lag during runtime, making the interaction experience less smooth and responsive.

4.1.3. Background Noise

In contrast to previous systems that relied solely on voice recognition, making them vulnerable to ambient noise and unintended speech, 3M-HCI integrates a mouth-open detection mechanism using facial landmarks. To evaluate its robustness, we conducted a test scenario where two people held a conversation near the system. While earlier studies [

4] reported performance degradation due to microphone sensitivity and background noise, our method was unaffected. Since voice commands in our system are only executed when the user’s mouth has been recently detected as open, environmental noise or nearby conversations had no impact on command triggering. This approach significantly reduces false positives and enhances reliability in shared or noisy environments.

However, this feature relies on the system’s ability to consistently detect the user’s full face. If the face is partially occluded, out of frame, or poorly lit, the mouth-open detection may fail to activate, thus preventing valid voice commands from being registered. Ensuring a clear and stable view of the user's face is therefore essential for maintaining the robustness of this mechanism.

4.1.4. Different Hardware and Software Features of the Computer

We evaluated the software performance across different machines and conducted a comparative analysis of three applications: 3M-HCI, Project GameFace, and CameraMouseAI. The results are summarized in Table 4 below:

Table 4.

Software performance on different laptops.

Table 4.

Software performance on different laptops.

| Laptop |

CPU |

RAM |

OS |

Overall

Performance |

Computational

Cost (3M-HCI) |

Computational

Cost [6] |

Computational

Cost [7] |

| Dell Inspiron 15 3530 |

Intel Core i7-1355U |

16GB |

Windows 11 |

Excellent |

12.7% |

15.1% |

26.7% |

| Dell XPS 13 9360 |

Intel Core i7-7660U |

16GB |

Windows 10 |

OK. The microphone takes time to boot |

49.9% |

60.3% |

Unable to run |

| Dell G15 5530 |

Intel Core i7-13650HX |

16GB |

Windows 11 |

Excellent |

10.7% |

23% |

8.5% |

| Lenovo ThinkPad T480 |

Intel Core i5-8350U |

8GB |

Windows 11 |

OK. The program is a bit laggy |

52.8% |

57.7% |

31.2% |

| Dell Precision 7510 |

Intel Core i7-6820HQ |

16GB |

Windows 10 |

Excellent |

37.9% |

41.5% |

18.8% |

| MSI GF63 Thin 11UD |

Intel Core i7-11800H |

16GB |

Windows

11 |

OK. The microphone takes time to boot |

19.7% |

28.3% |

Unable to run |

| Dell Inspiron 16 5620 |

Intel Core i5-1240P |

16GB |

Windows 11 |

Excellent |

6.1% |

20.56% |

16.2% |

| HP Laptop 16-d0xxx |

Intel Core i5-11400H |

8GB |

Windows 11 |

Excellent |

24.7% |

19.1% |

11.05% |

| ASUS TUF Gaming F15 |

Intel Core i5-10300H |

16GB |

Windows 11 |

Some commands cannot be recognized. |

41.88% |

47.37% |

23.4% |

| MSI Modern 15 |

AMD Ryzen 5 5500U |

12GB |

Windows 11 |

Voice command runs badly. |

34.6% |

47.4% |

17.2% |

Compared to other applications, our software runs efficiently and stably. Despite integrating voice commands, our system still consumes fewer computational resources than Google's solution. CameraMouseAI exhibits lower computational cost than ours, likely because it is a simpler tool, supporting only 2–3 basic mouse actions.

Based on Table 4, we recommend the following minimum system requirements: Windows 10 or higher, a CPU equivalent to Intel Core i5-10th Gen or above, no dedicated GPU is required, a functional camera and microphone, and at least 8GB of RAM. These are very lightweight requirements, making the system compatible with nearly all modern laptops.

4.2. Empirical Task-Based Test

We conducted a pilot user study involving eight participants to empirically evaluate the usability, responsiveness, and precision of the proposed 3M-HCI system in real-world interaction scenarios. All participants provided informed consent prior to the study. The objective of this test was to assess how effectively users could perform common cursor-based tasks using hands-free input, in comparison with traditional mouse input and two baseline systems: Project GameFace and CameraMouseAI. Each participant was asked to complete a set of target selection and click tasks under identical conditions across all systems. Key performance metrics, including pointer accuracy, latency, jitter, and number of successful clicks, were recorded. Additionally, a post-test survey was conducted to capture user satisfaction and perceived usability. The findings from this pilot study provide preliminary insights into the practical viability and comparative advantages of our system in assistive computing contexts.

4.2.1. System Accuracy

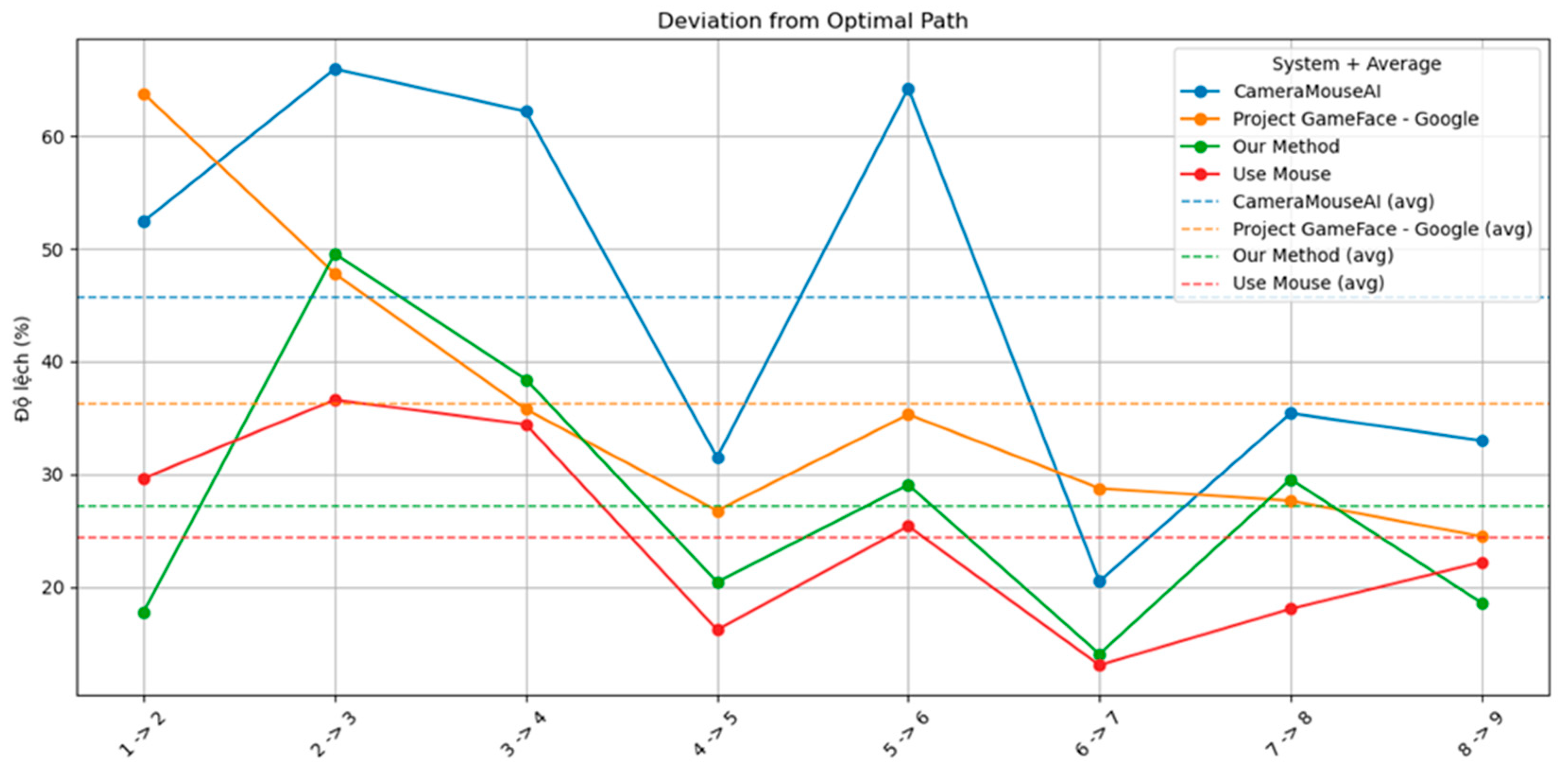

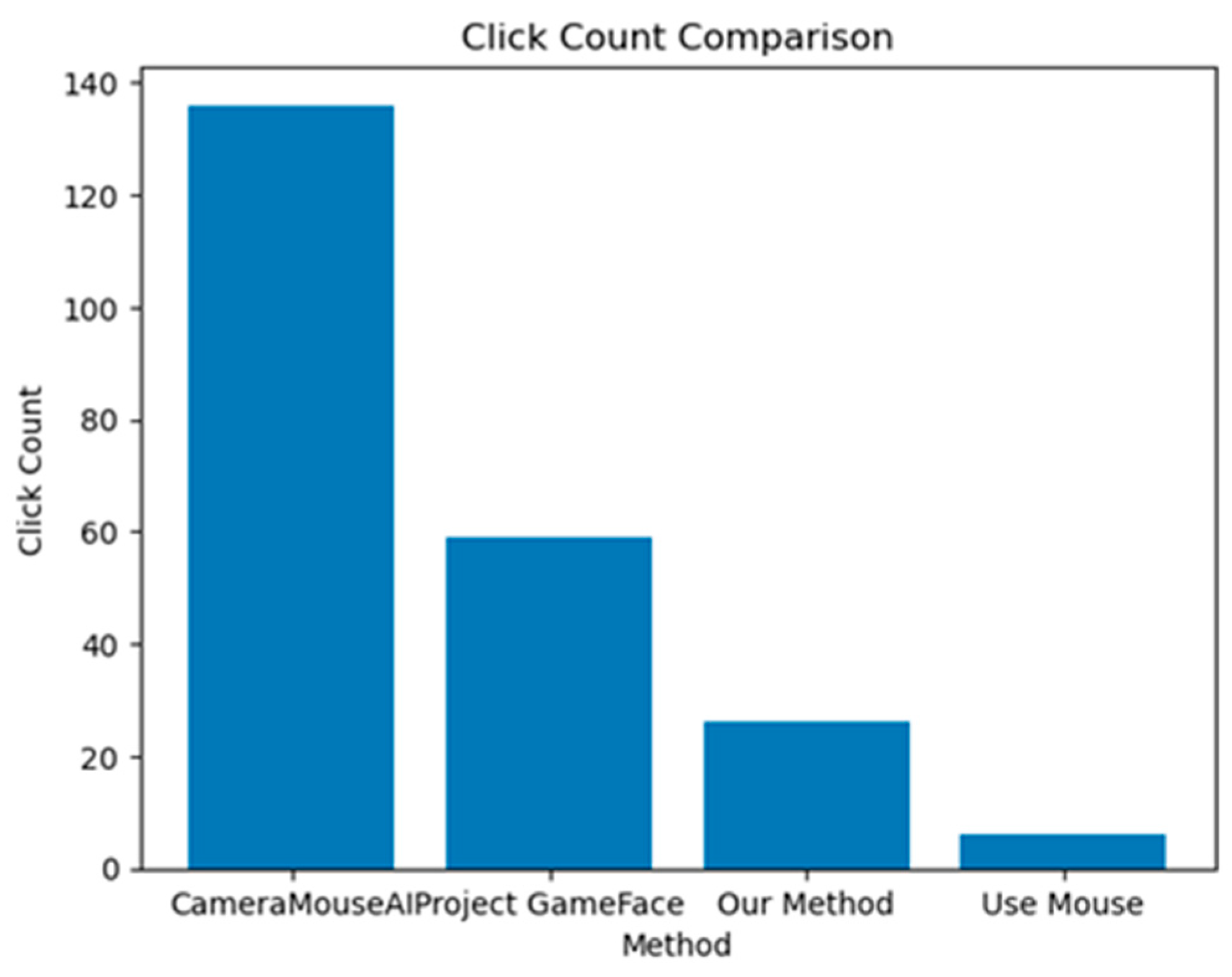

We measured the system’s accuracy by calculating the deviation of four systems (CameraMouseAI, Project GameFace - Google, Our Method (3M-HCI), and Normal Mouse) from the optimal path (straight path) to the target, along with the number of clicks required to complete the task. The results are presented in Figure 9 and Figure 10 below.

Figure 9.

Deviation from Optimal Path.

Figure 9.

Deviation from Optimal Path.

Figure 10.

Number of clicks.

Figure 10.

Number of clicks.

Overall, our system demonstrated higher accuracy compared to CameraMouseAI and Project GameFace. Overshooting was not observed in our system, in contrast to CameraMouseAI, where it occurred frequently during cursor movement. Regarding the clicking mechanism, both CameraMouseAI and Project Gameface experienced unintended cursor movement during facial expression activation, leading to incorrect clicks. Our system did not encounter this issue due to a more optimal selection of anchor points.

4.2.2. System Responsiveness.

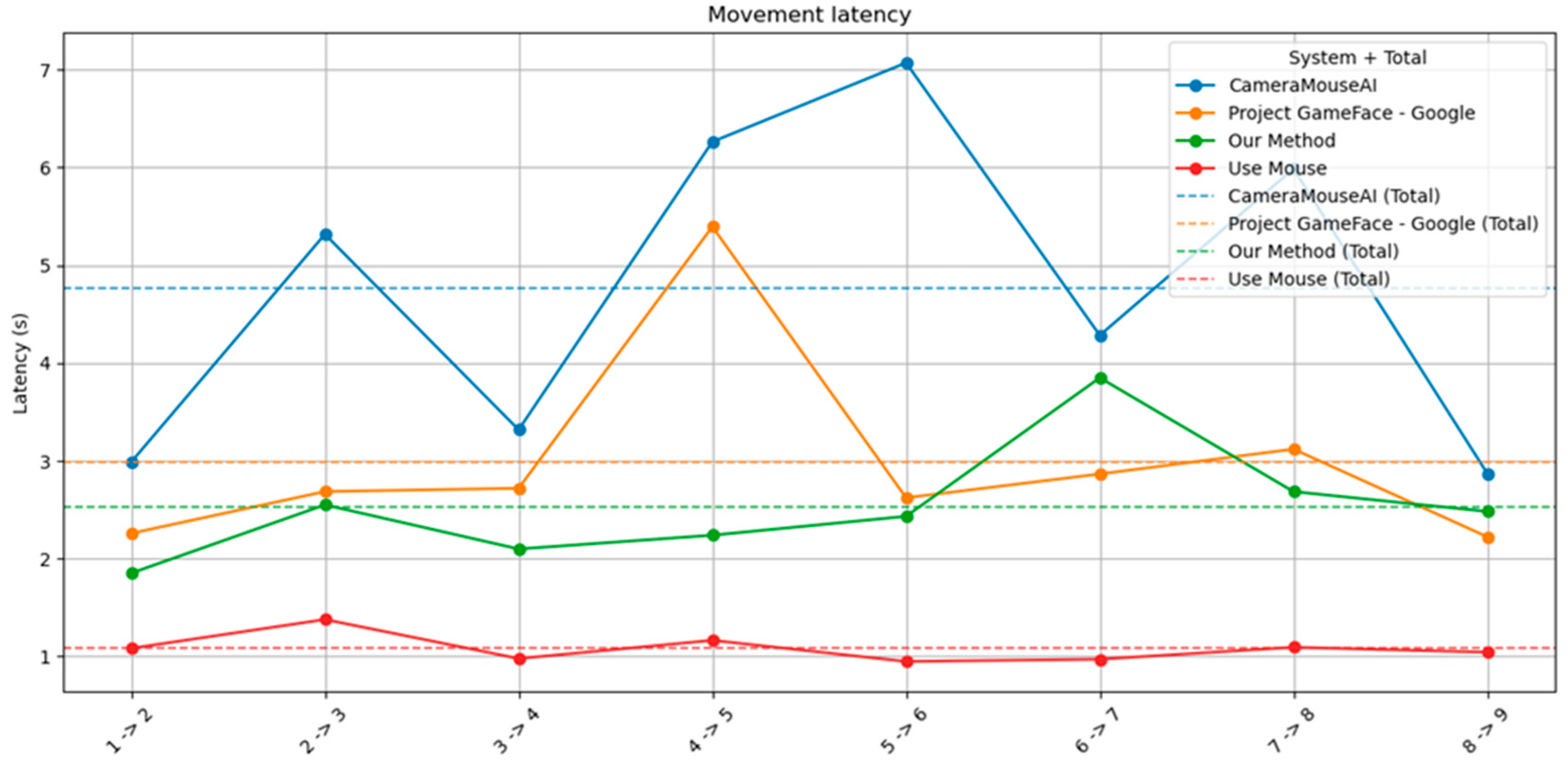

We also measured the time taken to complete the first task as an indicator of system responsiveness. The result is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Movement Latency.

Figure 11.

Movement Latency.

As shown in the figure, our method consistently outperformed both CameraMouseAI and Project GameFace in terms of movement latency. Across all target transitions (e.g., 1→2, 2→3, etc.), our system maintained latency values around 2 to 3 seconds, with minimal fluctuation. In contrast, CameraMouseAI exhibited the highest latency, with several spikes exceeding 6 seconds—most notably in the 5→6 transition. Project GameFace also showed relatively high latency, particularly during transitions 4→5 and 6→7.

Moreover, the total average latency of our system (green dashed line) is clearly lower than that of CameraMouseAI (blue dashed line) and Project GameFace (orange dashed line), indicating faster and more consistent performance. While traditional mouse input (red line) remains the fastest as expected, our method shows a strong balance between speed and usability, especially considering its hands-free nature.

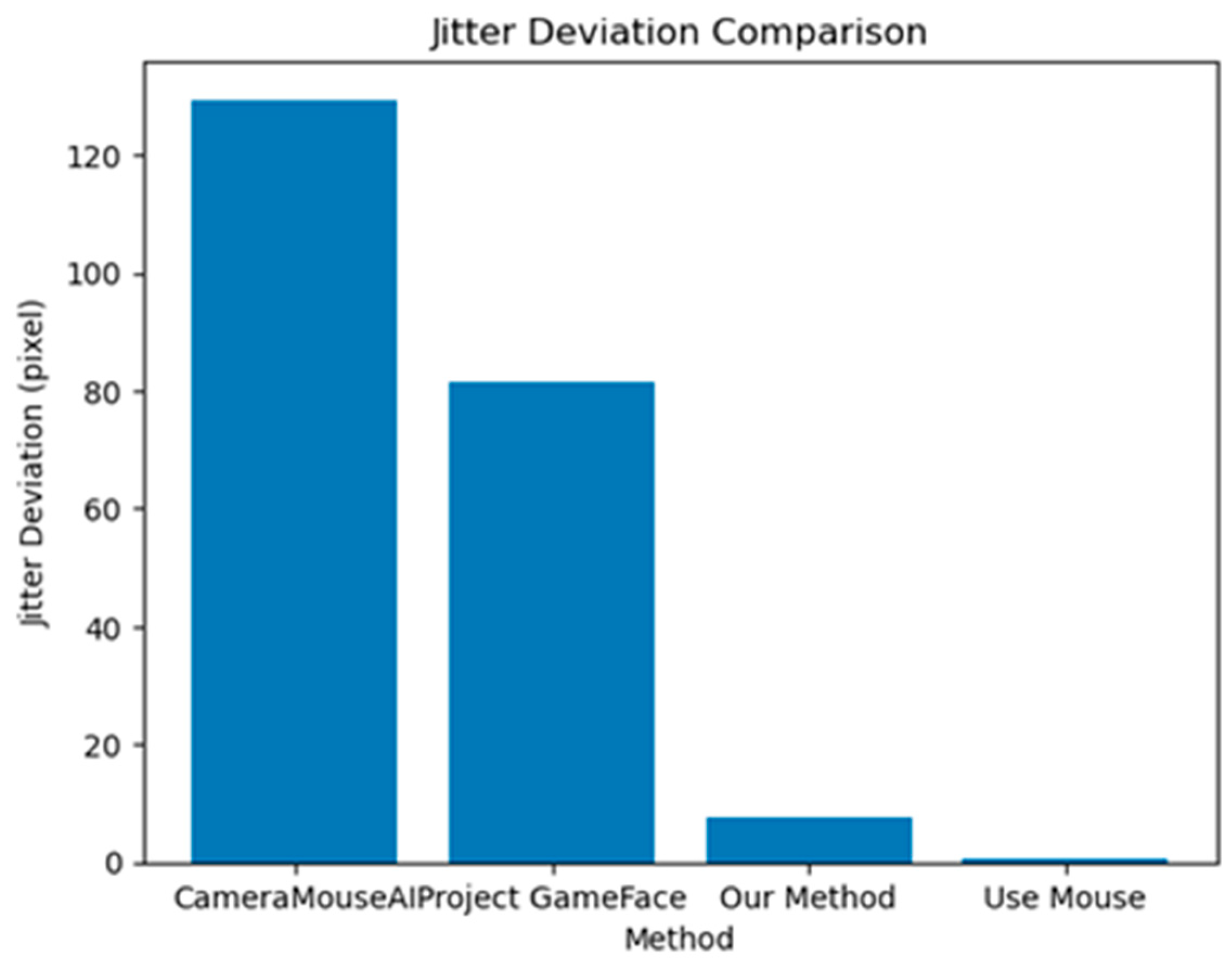

4.2.3. System Jitterness

As illustrated in Figure 12, our method achieved significantly lower jitter deviation compared to other hands-free systems. Specifically, the CameraMouseAI showed the highest instability with a jitter deviation of over 120 pixels, followed by Project GameFace with approximately 80 pixels. In contrast, our method maintained a low deviation of under 10 pixels, indicating stable and precise cursor control. As expected, traditional mouse usage yielded the lowest jitter, serving as a performance baseline.

This finding highlights the importance of incorporating adaptive filter algorithms and activation mechanisms in hands-free systems. By minimizing cursor jitter, our approach improves not only task precision but also user comfort and trust, which are critical for sustained use, especially among individuals with motor impairments.

Figure 12.

Jitter Deviation of Different Systems.

Figure 12.

Jitter Deviation of Different Systems.

4.3. Survey Results

The survey results provide insights into the subjective usability, responsiveness, and comfort of our system compared to existing solutions, including CameraMouseAI, Project GameFace, and traditional mouse control. We present the result below in Table 5.

Table 5.

Survey Results.

| Question |

Description |

CameraMouseAI |

Project GameFace |

3M-HCI (Ours) |

Mouse |

| Q1 |

Does it take a lot of time to master the application? |

3.5 ± 1.87 |

6.75 ± 1.98 |

7.25 ± 1.71 |

10.0 ± 0.0 |

| Q2 |

Is the response of left/right mouse click fast? |

3.5 ± 2.35 |

7.5 ± 1.58 |

8.25 ± 1.09 |

10.0 ± 0.0 |

| Q3 |

Is the cursor movement responsive? |

5.38 ± 2.06 |

6.62 ± 1.11 |

8.88 ± 0.6 |

10.0 ± 0.0 |

| Q4 |

Is it difficult to click the left/right mouse button? |

4 ± 2.55 |

6.25 ± 1.56 |

7 ± 1.87 |

10.0 ± 0.0 |

| Q5 |

Is it difficult to move the cursor precisely? |

3.5 ± 2.45 |

6.87 ± 1.17 |

8.37 ± 0.7 |

10.0 ± 0.0 |

| Q6 |

Is it difficult to move the cursor vertically? |

4.5 ± 2.18 |

7.5 ± 1.41 |

8.37 ± 0.86 |

10.0 ± 0.0 |

| Q7 |

Is it difficult to move the cursor horizontally? |

4.5 ± 2.18 |

7.5 ± 1.41 |

8.37 ± 0.86 |

10.0 ± 0.0 |

| Q8 |

Does moving the cursor cause fatigue? |

2.62 ± 1.93 |

7 ± 1.87 |

7.25 ± 1.79 |

9.87 ± 0.33 |

| Q9 |

Do you think this mouse system can be applied for people with disabilities? |

4 ± 3.53 |

7.12 ± 2.52 |

7.85 ± 2.71 |

7.75 ± 3.9 |

The results in the table indicate that our proposed 3M-HCI system achieved high subjective ratings across all categories. Notably, it received an average score of 8.25 ± 1.09 for the responsiveness of left/right mouse clicks and 8.88 ± 0.6 for overall cursor responsiveness, comparable to the traditional mouse and outperforming both CameraMouseAI and Project GameFace.

In terms of ease of use, participants reported that our system required relatively little time to master (7.25 ± 1.71), and clicking actions were less difficult (7 ± 1.87) compared to other hands-free systems. One contributing factor is that our system allows users to choose from multiple facial expressions for click activation. Since different users may find certain expressions easier or more natural to perform, this flexibility improves comfort and accessibility. Additionally, our system maintains cursor stability during facial expression recognition, avoiding unintended cursor jumps—an issue observed in other systems such as CameraMouseAI and Project GameFace. Precision and directional control (both vertical and horizontal) were also rated higher than alternatives, indicating more stable and accurate performance.

Fatigue levels while using the system were moderate (7.25 ± 1.79), significantly better than CameraMouseAI (2.62 ± 1.93) and slightly better than Project GameFace (7 ± 1.87), showing the ergonomic advantages of our approach. Importantly, our system received the highest rating (7.85 ± 2.71) in terms of perceived applicability for people with disabilities, suggesting strong user confidence in its real-world assistive potential.

4.4. Limitations

Despite the overall positive results, several limitations were identified based on user feedback during testing. One notable issue was the lack of intuitive parameter tuning, as users found it difficult to adjust the minCutoff and beta values of the 1-Euro filter. This difficulty stems from the technical definitions of minCutoff and beta, making it challenging to grasp their impact on the filtering process. Consequently, this limitation significantly hinders accessibility and the ability to optimize the filter's performance. Another concern was microphone instability on low-end devices, where users reported delays in microphone initialization or instances where speech was not recognized, particularly during system startup or under constrained hardware conditions.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents 3M-HCI, a novel, low-cost, and hands-free human-computer interaction system that integrates facial expressions, head movements, eye gaze, and voice commands through a unified processing pipeline. The central contribution of 3M-HCI lies in its unified processing architecture, which integrates three key components: 1) a cross-modal coordination mechanism that synchronizes facial, vocal, and eye-based inputs to enhance reliability and reduce false triggers; 2) an adaptive signal filtering method that suppresses input noise while maintaining low-latency responsiveness; and 3) a refined input-to-cursor mapping strategy that improves control accuracy and minimizes jitter.

Although experimental results demonstrate that 3M-HCI outperforms several recent baseline models in both accuracy and responsiveness, the system still requires further refinement. User feedback revealed areas where usability and flexibility can be significantly improved, particularly in terms of parameter customization and robustness on low-end devices. We aim to simplify the tuning of the One Euro Filter by introducing a real-time interface that abstracts away low-level parameters like minCutoff and beta, allowing users to adjust the filter's responsiveness through more intuitive controls.

In this paper, the voice command component was not explored in depth. We selected a lightweight and general-purpose voice recognition module to ensure broad compatibility and minimal computational overhead. The primary design criteria were simplicity, low latency, and ease of integration. However, more advanced alternatives could be considered. For instance, integrating modern speech recognition frameworks such as OpenAI Whisper [

38] may offer improved robustness, especially in noisy environments. In addition, exploring non-speech voice command systems [

39] could further enhance responsiveness, particularly beneficial for gamers. Additionally, our system currently underutilizes eye input. While eye direction is used as a gesture trigger, the system does not yet leverage richer gaze data for pointer control or attention estimation. Enhancing eye-tracking integration could significantly improve precision and interaction depth, especially for users with limited facial mobility. This direction will be further investigated in our future work to improve the adaptability and inclusiveness of the system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.H.Q.; methodology, B.H.Q. and N.D.T.A.; software, B.H.Q. and N.D.T.A.; validation, B.H.Q., N.D.T.A., H.V.P., and B.T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.H.Q., H.V.P., and N.D.T.A.; writing—review and editing, B.T.T.; visualization, B.H.Q. and H.V.P.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the technical support from Human-Machine Interaction Lab (VNU-UET).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3M-HCI |

3-Modal Human-Computer Interaction |

| ALS |

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN |

Convolution Neural Network |

| CPU |

Central Processing Unit |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

| RAM |

Random Access Memory |

| RGB |

Red Green Blue |

| OS |

Operating System |

References

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2016), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, C.K.; Joseph, A. IEyeGASE: An Intelligent Eye Gaze-Based Assessment System for Deeper Insights into Learner Performance. Sensors 2021, 21(20), 6783. [CrossRef]

- Walle, H.; De Runz, C.; Serres, B.; Venturini, G. A Survey on Recent Advances in AI and Vision-Based Methods for Helping and Guiding Visually Impaired People. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12(5), 2308. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.; Zapata, M.; Valencia, K.; Vargas, V.; Ramos-Galarza, C. Low-Cost Human–Machine Interface for Computer Control with Facial Landmark Detection and Voice Commands. Sensors 2022, 22(23), 9279. [CrossRef]

- Zapata, M.; Valencia-Aragón, K.; Ramos-Galarza, C. Experimental Evaluation of EMKEY: An Assistive Technology for People with Upper Limb Disabilities. Sensors 2023, 23(8), 4049. [CrossRef]

- Project Gameface. Available online: https://blog.google/technology/ai/google-project-gameface/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- MacLellan, L.E.; Stepp, C.E.; Fager, S.K.; Mentis, M.; Boucher, A.R.; Abur, D.; Cler, G.J. Evaluating Camera Mouse as a computer access system for augmentative and alternative communication in cerebral palsy: a case study. Assist. Technol. 2024, 36(3), 217–223. [CrossRef]

- Karimli, F.; Yu, H.; Jain, S.; Akosah, E.S.; Betke, M.; Feng, W. Demonstration of CameraMouseAI: A Head-Based Mouse-Control System for People with Severe Motor Disabilities. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS 2024), Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–10 October 2024; pp. 124:1–124:6. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Hu, D.; Gu, S.; Xiao, S.; Song, F. The global burden of traumatic amputation in 204 countries and territories. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1258853. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Raymond, J.; Nair, T.; Han, M.; Berry, J.; Punjani, R.; Larson, T.; Mohidul, S.; Horton, D.K. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis estimated prevalence cases from 2022 to 2030, data from the National ALS Registry. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 2025, 26(3-4), 290-295. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L. Application of tilt sensors in human–computer mouse interface for people with disabilities. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2001, 9(3), 289–294. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Bhalla, A.; Kharad, S.; Yadav, D. Int. J. Recent Innov. Trends Comput. Commun. 2017, 5(5), 576–583.

- Ribas-Xirgo, L.; López-Varquiel, F. Accelerometer-Based Computer Mouse for People with Special Needs. J. Access. Des. All. 2017, 7, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, M.; Anumas, S.; Yoo, J. Head Mouse System Based on Gyro- and Opto-Sensors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Informatics, Yantai, China, 16–18 October 2010. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.A.M.; Bolliger Neto, R.; Reynaldo, A.C.; Luzo, M.C.M.; Oliveira, R.P. Development and evaluation of a head-controlled human-computer interface with mouse-like functions for physically disabled users. Clinics 2009, 64(10), 975–981. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-S.; Ho, C.-W.; Chan, C.-N.; Chau, C.-R.; Wu, Y.-C.; Yeh, M.-S. An Eye-Tracking and Head-Control System Using Movement Increment-Coordinate Method. Opt. Laser Technol. 2007, 39(6), 1218–1225. [CrossRef]

- Betke, M.; Gips, J.; Fleming, P. The Camera Mouse: Visual Tracking of Body Features to Provide Computer Access for People with Severe Disabilities. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2002, 10(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Su, M.C.; Su, S.Y.; Chen, G.D. A low-cost vision-based human-computer interface for people with severe disabilities. Biomed. Eng. Appl. Basis Commun. 2005, 17, 284–292. [CrossRef]

- Naizhong, Z.; Jing, W.; Jun, W. Hand-free head mouse control based on mouth tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computational Science and Education (ICCSE 2015), Cambridge, UK, 22–24 July 2015. [CrossRef]

- Arai, K.; Mardiyanto, R. Camera as Mouse and Keyboard for Handicap Person with Troubleshooting Ability, Recovery, and Complete Mouse Events. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2010, 1(3), 46–56.

- Ismail, A.; Al Hajjar, A.E.S.; Hajjar, M. A prototype system for controlling a computer by head movements and voice commands. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1109.1454. [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, D.; Kowalczyk, P. Head Movement Based Interaction in Mobility. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2017, 34, 653–665. [CrossRef]

- Abiyev, R.H.; Arslan, M. Head mouse control system for people with disabilities. Expert Syst. 2019, 37(1), e12398. [CrossRef]

- Rahmaniar, W.; Ma’Arif, A.; Lin, T.-L. Touchless Head-Control (THC): Head Gesture Recognition for Cursor and Orientation Control. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 1817–1828. [CrossRef]

- Zelinskyi, S.; Boyko, Y. Using Facial Expressions for Custom Actions: Development and Evaluation of a Hands-Free Interaction Method. Computer Syst. Inf. Technol. 2024, 4, 116-125. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yin, L.; Zhang, H. A real-time camera-based gaze-tracking system involving dual interactive modes and its application in gaming. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 15. [CrossRef]

- Dlib. Available online: https://dlib.net/python/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Viola, P.A.; Jones, M. Rapid Object Detection using a Boosted Cascade of Simple Features. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2001), Kauai, HI, USA, 8–14 December 2001; pp. 511–518. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Modi, N. A robust, real-time camera-based eye gaze tracking system to analyze users’ visual attention using deep learning. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 30, 409–430. [CrossRef]

- Mediapipe. Available online: https://ai.google.dev/edge/mediapipe/solutions/guide (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Qiao, Y. Joint Face Detection and Alignment Using Multitask Cascaded Convolutional Networks. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2016, 23, 1499–1503. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Peng, H.; Yu, S. YuNet: A Tiny Millisecond-level Face Detector. Mach. Intell. Res. 2023, 20, 656–665. [CrossRef]

- Casiez, G.; Roussel, N.; Vogel, D. 1 € Filter: A Simple Speed-based Low-pass Filter for Noisy Input in Interactive Systems. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’12), Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; pp. 2527–2530. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sidenmark, L.; Weidner, F.; Newn, J.; Gellersen, H. HeadShift: Head Pointing with Dynamic Control-Display Gain. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2025, 32(1), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Voelker, S.; Hueber, S.; Corsten, C.; Remy, C. HeadReach: Using Head Tracking to Increase Reachability on Mobile Touch Devices. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’20), Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 739:1–739:12. [CrossRef]

- Nancel, M.; Chapuis, O.; Pietriga, E.; Yang, X.-D.; Irani, P.P.; Beaudouin-Lafon, M. High-Precision Pointing on Large Wall Displays Using Small Handheld Devices. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '13), Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013; pp. 831–840. [CrossRef]

- SAPI5 (Dragonfly). Available online: https://dragonfly2.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2023), Baltimore, MD, USA, 23–29 July 2023, pp. 28492–28518.

- Harada, S.; Wobbrock, J.O.; Landay, J.A. Voice Games: Investigation Into the Use of Non-speech Voice Input for Making Computer Games More Accessible. In Proceedings of the 13th IFIP TC 13 International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (INTERACT 2011), Lisbon, Portugal, 5–9 September 2011; Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 6946, pp. 11–29. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).