1. Introduction

Charge-transfer (CT) can be described as a molecular interaction in which an electron-rich donor molecule transfers its partial electron density to an electron-poor acceptor, forming a non-covalent complex [

1,

2]. Charge-transfer complexes (CTCs) between strong π-acceptors such as 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ) and electron-rich molecules have long been studied for their structural and optical properties [3-7]. The electron donation from a donor molecule’s highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) into the

π* acceptor levels or lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of DDQ leads to new low-energy transitions [

8]. Strong donors such as aromatic amines (e.g. 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP)) [

6] or aromatic

π-systems (e.g. fluorene, naphthalene, and perylene) [

9,

10] are known to form stoichiometrically 1:1 CT complexes with DDQ [

11]. In many cases CT complexes adopt face-to-face

π–π stacking geometries that facilitate π-electron overlap [

12]. This interaction often leads to new optical and/or electronic properties, such as visible light or near-infrared (NIR) absorption, and plays an important role in various fields, including materials science, photochemistry, polymer chemistry and supramolecular crystal design [

2,

13,

14].

Light-induced polymerization has become an enabling technology in advanced materials (coatings, 3D printing, additive manufacturing and electronics) due to its rapid curing, requirement of low-energy and solvent-free processing [15-18]. In particular, cationic photopolymerization offers advantages such as oxygen-insensitivity and low shrinkage, making it an attractive method [

15,

19]. Traditional cationic photoinitiators (e.g. onium salts) can readily generate strong acids under UV irradiation [

20,

21]. However, the limited penetration and high energy of UV light restrict the use of standalone onium salts for industrial applications [

22,

23].

To overcome this problem, researchers have sought new strategies to sensitize cationic systems to visible light. Several dyes have been utilized as photosensitizers to shift the onium salts’ activation into the visible or NIR region [

24,

25]. Alternatively, CTCs have emerged as intrinsically light-harvesting photoinitiators. In these systems, a ground-state association between an electron-rich donor and an acceptor (such as a DDQ or onium salt) creates a complex with red-shifted absorption. Upon irradiation, the CTC can undergo intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) to generate radical ion pairs, ultimately producing acidic species (or radicals) that can trigger polymerization [

17,

26].

CTCs have been previously utilized as efficient photoinitiators for cationic polymerizations, effectively extending photoactivation into the visible regime. For example, photoredox catalysts and CT pairs have been used to initiate ring-opening polymerizations of epoxides and cationic polymerizations of vinyl ethers [

27,

28]. Especially, cyclohexene oxide (CHO) and vinyl ethers are well-known cationically polymerizable monomers that can be activated by photo-generated acids or radical cations [

28,

29]. These findings motivate the use of CTCs as “dye-free” photoinitiating systems in polymer synthesis.

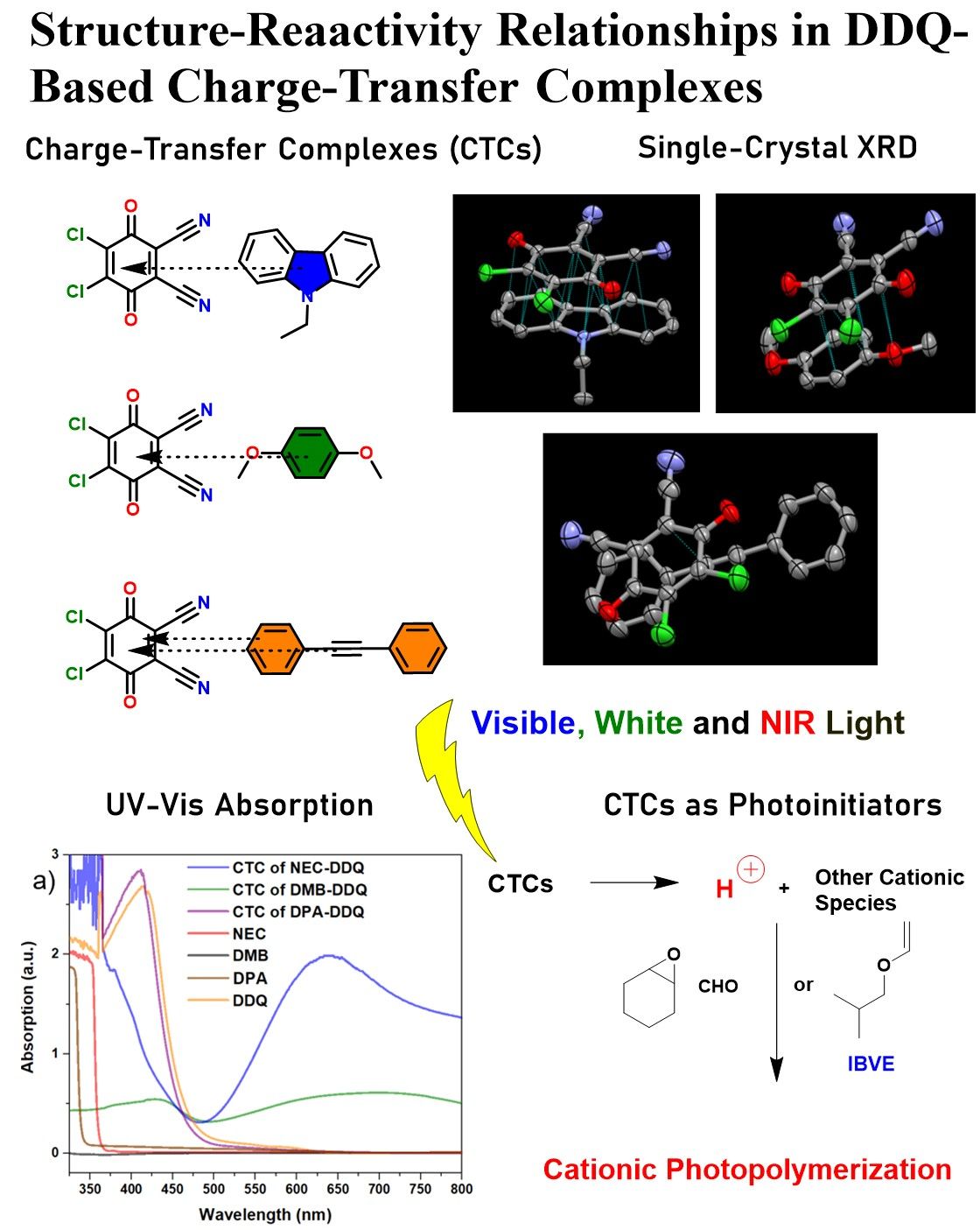

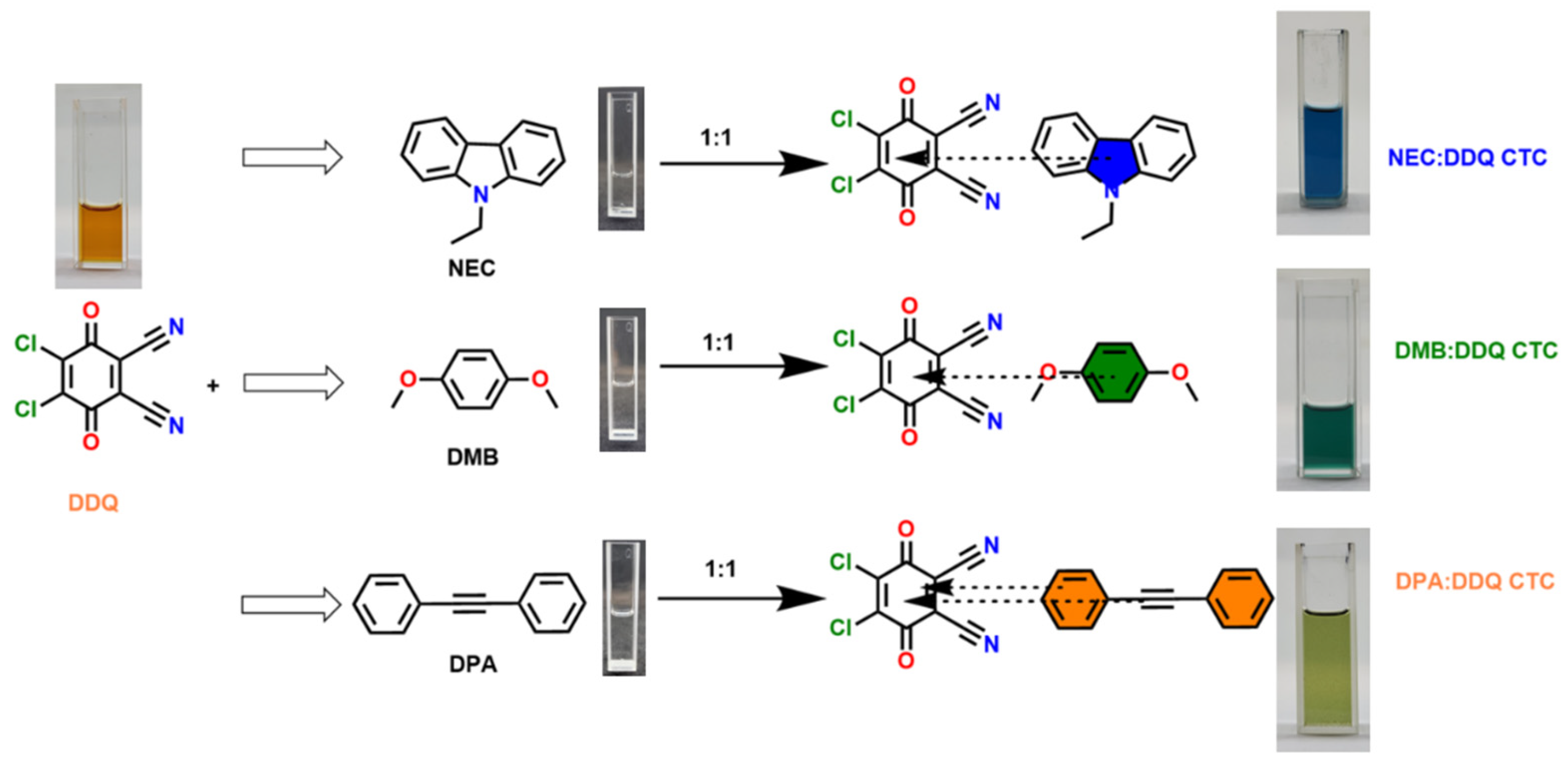

In this study, we combine single-crystal X-ray analysis, UV–vis, NMR spectroscopy, DFT analysis, and cationic photopolymerization results to explore structure–reactivity relationships in three different DDQ-based CTCs. We focus on three donor types: N-ethylcarbazole (NEC) and p-dimethoxybenzene (DMB) as relatively strong π-donors, and diphenylacetylene (DPA) as a relatively weaker π-donor. We report the crystal structures of these CT complexes, analyze their charge-transfer absorptions by conducting UV-Vis spectroscopy, check the chemical shifts in NMR, investigate the electronic states through DFT studies, and then test each CT complex as a photoinitiator for cationic polymerization of CHO, isobutyl vinyl ether (IBVE), and ε-caprolactone (ECL) under visible, white and NIR wavelengths. The data reveal clear correlations: stronger donors and favorable stacking geometries lead to larger CT band intensities and more efficient photopolymerization initiation, whereas weak donor or mismatched geometry gives weak CT absorption resulting in no efficient photoinitiation, thus, no photopolymerization. These results provide insight into how molecular structure controls the light-induced reactivity of DDQ-based CT complexes.

2. Materials and Methods

2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ) (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), 9-ethylcarbazole (N-ethylcarbazole) (Sigma-Aldrich, 97%), 1-4-dimethoxybenzene (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%), Diphenylacetylene (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), Methanol (Technical Grade), Dichloromethane Sigma-Aldrich, 99%), Chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%) and Tetrahydrofuran (THF) (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%), Deuterated Chloroform (CDCl3) and Deuterated Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) were used without further purification. Cyclohexene oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), Isobutyl vinyl ether and -caprolactone (Sigma-Aldrich, 97%) were initially mixed overnight with calcium hydride (Sigma-Aldrich, 95%) under nitrogen atmosphere and then distilled under vacuum prior to use.

2.1. Preparation of Charge-Transfer Single-Crystals for Structure Determination

The synthesized CT complexes (NEC: DDQ, DMB: DDQ and DPA: DDQ) were obtained by mixing a saturated solution of equimolar amounts of DDQ (0.227 g, 1 mmol) dissolved in 1 mL of THF, with three separate solutions of NEC (0.195g, 1 mmol), DMB (0.138 g, 1 mmol) and DPA (0.178g, 1 mmol) dissolved in 1 mL THF. Upon mixing, the solutions turned to blue, green and greenish-orange, respectively. The single crystals of CT complexes were obtained by allowing THF solvent to evaporate slowly at room temperature for over a week.

2.2. Measurements and Characterization

Gel permeation chromatography measurements were performed on a TOSOH EcoSEC GPC system equipped with an auto sampler system, a temperature-controlled pump, a column oven, a refractive index (RI) detector, a purge and degasser unit and TSKgel superhZ2000, 4. 6mm ID x 15 cm x 2 cm column. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) was used as an eluent at flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1 at 40°C. The GPC system was calibrated with polystyrene (PS) standards having narrow molecular-weight distributions. GPC data were analyzed using Eco-SEC Analysis software.

UV–visible spectra were recorded with a Shimadzu UV-1601 double-beam spectrometer equipped with a 50 W halogen lamp and a deuterium lamp which can operate between 250 nm - 900 nm.

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu IR Spirit-X Compact using ATR technique (QATR-S). 64 scans were averaged.

1H NMR spectra were recorded using deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) or deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) as solvent with tetramethyl silane as an internal standard at 500 MHz, using Agilent VNMRS 500 spectrometer at 25oC.

Delta OHM Quantum radiophotometer was used to measure the light intensity of all the photoreactors.

2.3. Photopolymerization Experiments

For all the photopolymerization experiments, 1 mL of CHO (~10 mmol), 1 mL of IBVE (~8 mmol) and 1 mL of ECL (~9 mmol) were separately added to CTC (NEC: DDQ, DMB: DDQ and DPA: DDQ) prepared by mixing DDQ (0.25 mmol) and corresponding material (0.25 mmol) inside a test tube and degassed. Then, the test tubes were irradiated either using visible light LEDs (nominal light at 405 nm with ~100 mW/cm

2 intensity), using white LEDs (nominal light at 470-630 nm) or an incandescent lamp emitting at NIR region (700-1100 nm ~190 mW/cm

2 intensity) for 8h. Following irradiation, all the solutions were precipitated into 20-fold (by volume) technical grade methanol. After centrifuging at 5000 rpm for 10 mins and decanting the solvent, the precipitates were dried under vacuum. Video demonstrating the sudden color changes when THF vacuum for 24h. Photos of photoreactors and precipitates can be found in the Supporting Information (

Figures S1 and S2), respectively. Video of the addition of orange-colored THF solution of DDQ to colorless THF solutions of NEC and DMB inside UV cuvettes can be found in the Supporting Information (Video S1).

2.4. X-Ray Crystallography

Single crystal X-ray diffraction measurements were performed at room temperature, using a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer equipped with Photon I CMOS detector and graphite monochromated Mo-K radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å), in the ϕ and ω scans mode. A semi empirical absorption correction was carried out using SADABS. Data collection, cell refinement, and data reduction were done with the SMART and SAINT programs [

30,

31]. Unit-cell dimensions were obtained from least-squares refinement of the setting angles of 24 reflections obtained in the range 5o < 2θ < 25

o. The structures were solved by direct methods using SIR97[

32] and refined by full-matrix least-squares methods using the program SHELXL97[

33]. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic thermal parameters, whereas H-atoms were placed in idealized positions and allowed to refine riding on the parent C atom. Molecular graphics were prepared using Mercury v4.2.0 [

34] and Olex2 v.1.5 software [

35].

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Single Crystal X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

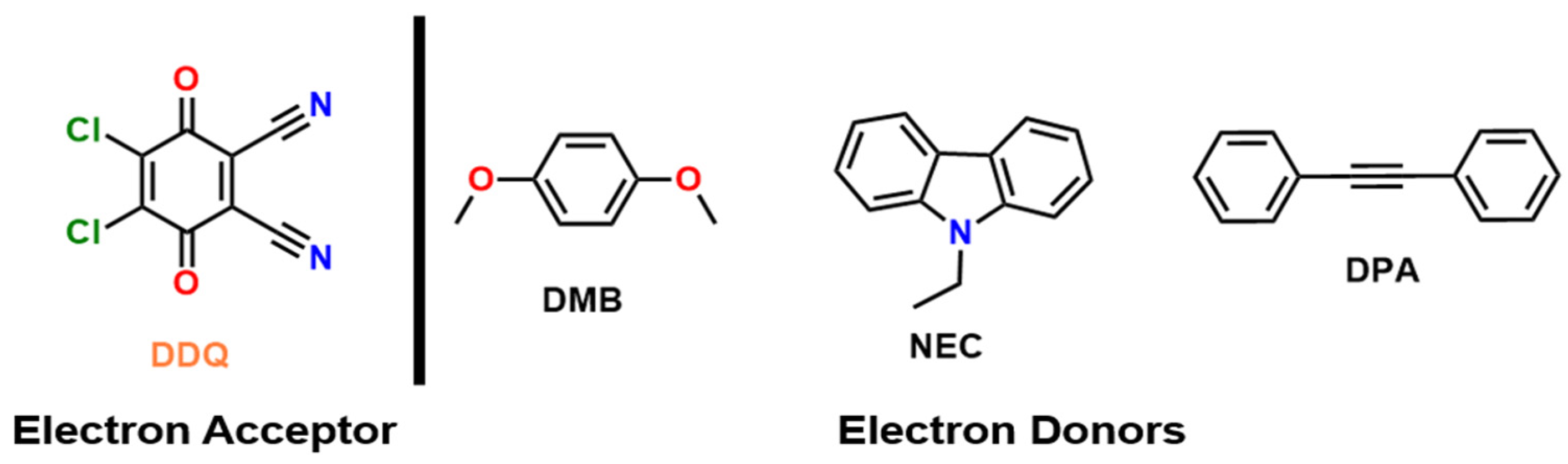

Chemical structures of the electron acceptor and the electron donors used in this study are depicted in

Scheme 1. The cocrystals of NEC-DDQ and DMB-DDQ grew in flat, straight rod-like shapes with a dark blue-green color. On the other hand, DPA-DDQ cocrystal grew in plate-like shape with a light-orange to green color. While NEC-DDQ and DMB-DDQ have monoclinic unit cells (P 1 21/c 1 space group), the unit cell of DPA-DDQ system is triclinic (P -1 space group). The crystal packing of all the cocrystals are shown in

Figure 1. The crystal structure information for the cocrystals is depicted in

Table 1. Additional crystallographic information regarding experimental details is provided in

Tables S1−S3 of the Supporting Information.

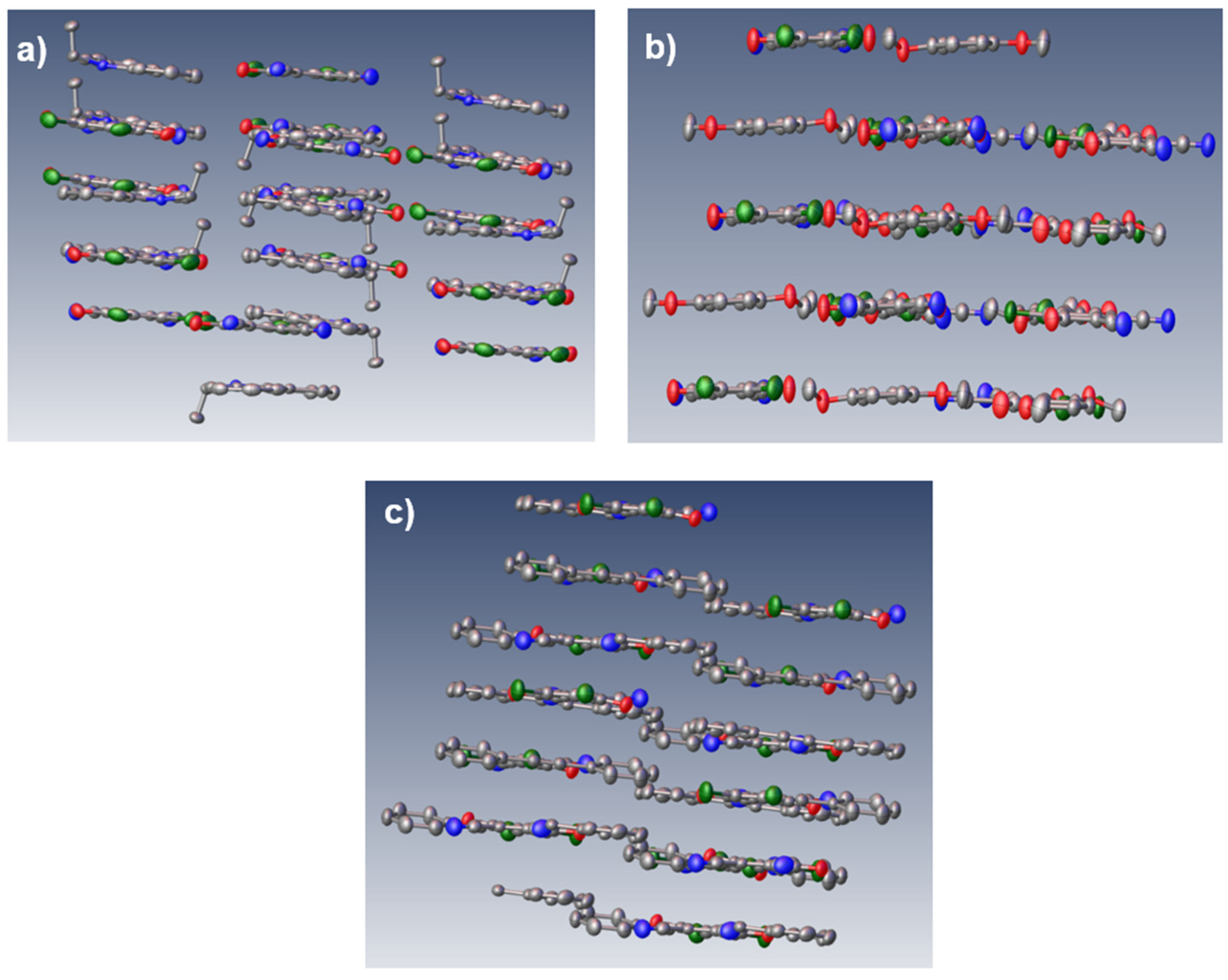

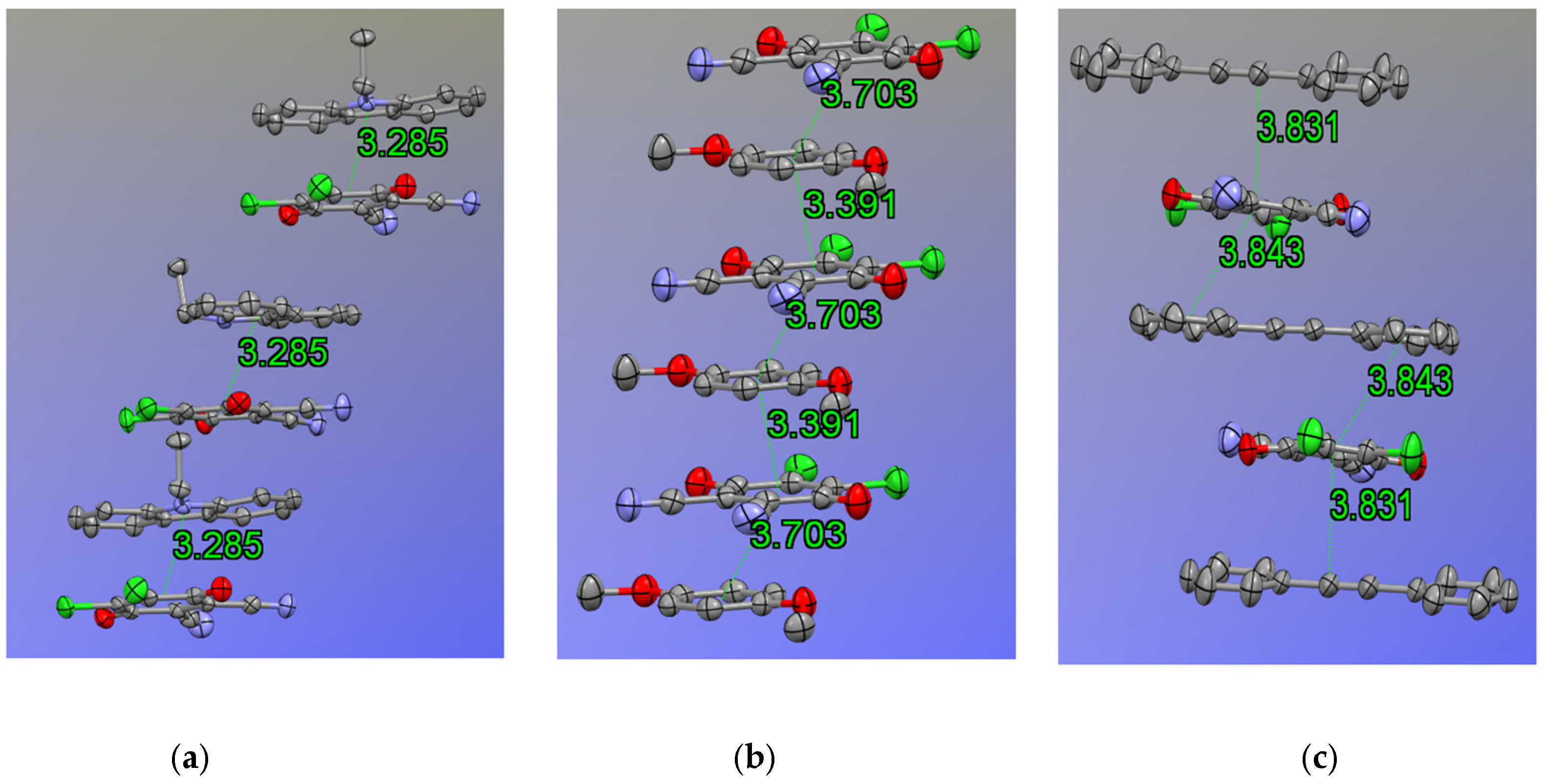

Single crystal X-ray analysis confirms that all donor complexes adopt alternating D–A stacks with π–π interactions dominating the crystal packing (

Figure 2). All the cocrystals have 1:1 donor-acceptor stoichiometry and display mixed donor−acceptor stacking in alternating columns (

Figure 3).

Scheme 2 summarizes the CT-interactions of the studied compounds. The donor aromatic plane is nearly co-planar with the DDQ quinone plane in each case. In particular, NEC–DDQ and DMB-DDQ cocrystals form essentially co-facial π-stacks in accordance with the previously observed carbazole–DDQ complexes [

36,

37]. The rings lie face-to-face or with only slight offset above the DDQ ring, giving centroid–centroid distances of 3.28 Å (

Figure 3a) and 3.39 Å (

Figure 3b), respectively. By contrast, DPA–DDQ complex has a pronounced slipped geometry: the linear diphenylacetylene lies nearly orthogonal to DDQ, with only one phenyl ring overlapping the quinone (

Figure 3c). This large offset (with a shift distance of 2.07 Å) increases the D–A separation and reduces π-overlap. Thus, strong donors favor close co-facial stacking, whereas DPA adopt less effective π–π contacts. In DPA-DDQ cocrystal, another weak -stacking occurs between DDQ’s phenyl unit and DPA’s carbon-carbon triple bond with a distance of 3.59 Å and a parallel alignment. This was previously observed in other DDQ-containing CT complexes.

Table 2 depicts π–π stacking distances and geometries.

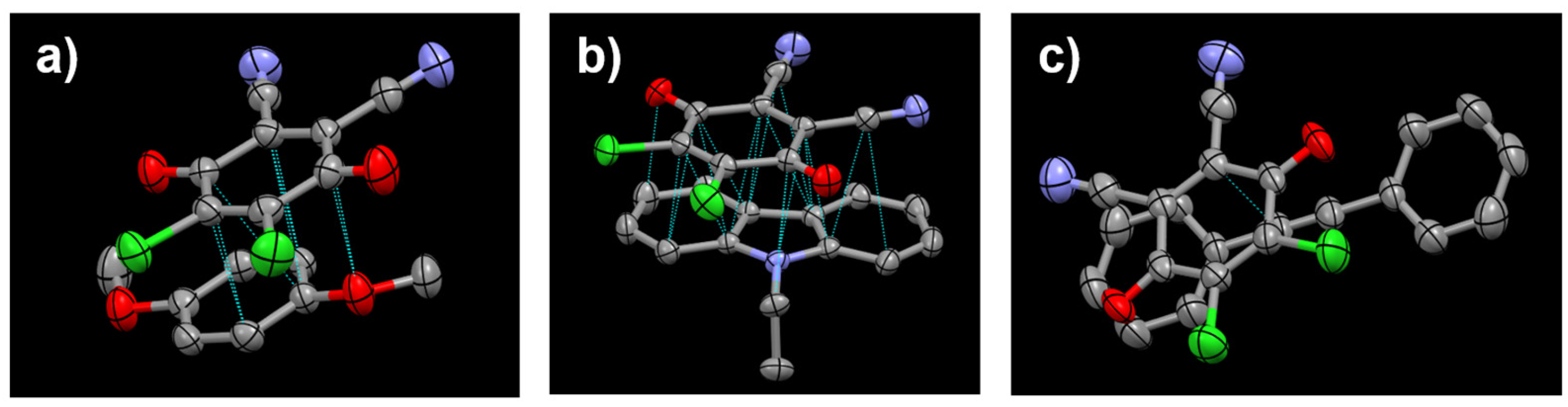

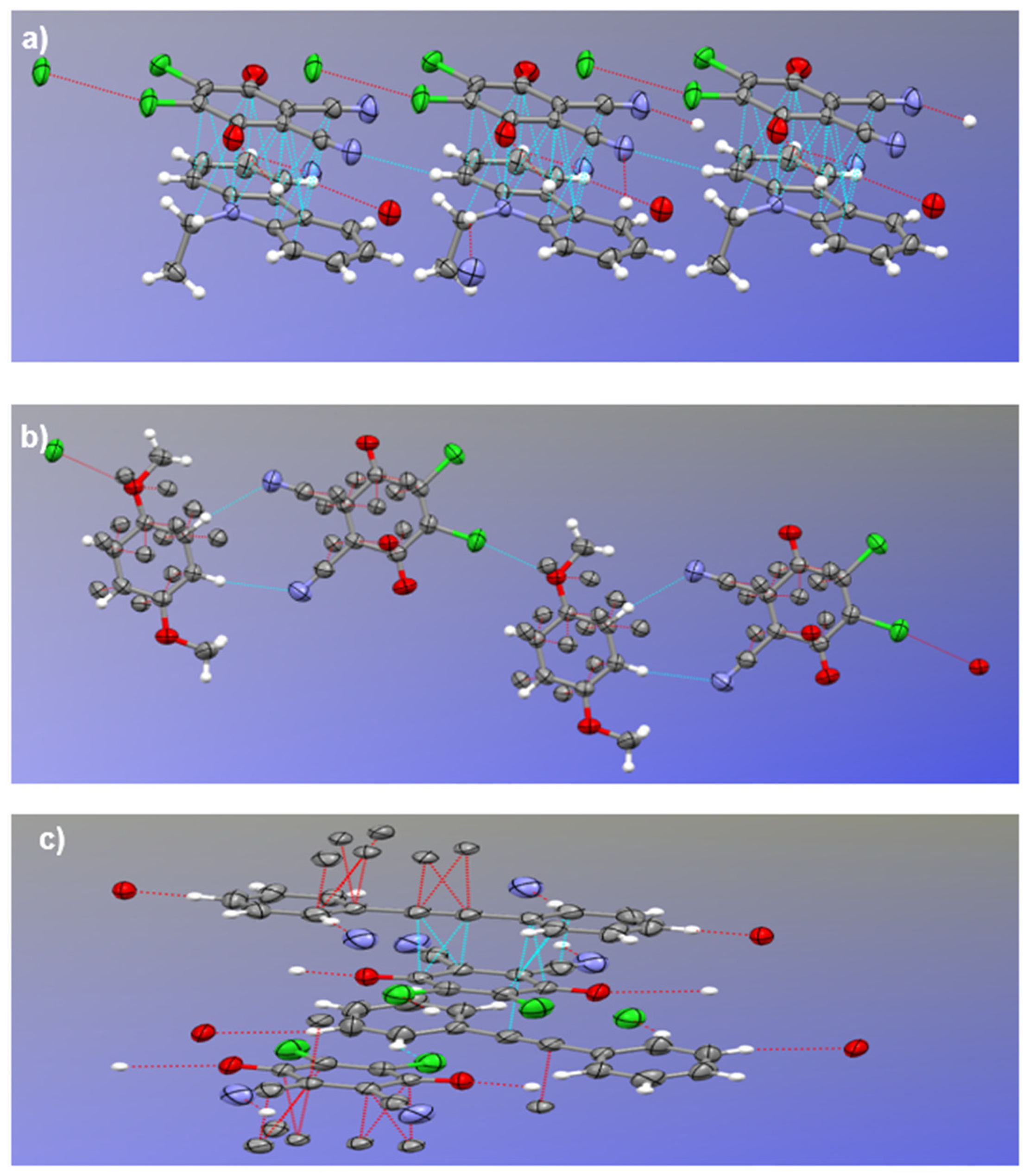

All the crystal lattices are further stabilized by weak non-covalent bonds including hydrogen bonding (

Figure 4), Cl---Cl and Cl---O interactions. In NEC-DDQ cocrystal, a weak hydrogen bonding between DDQ’s quinone group (C18=O2) and NEC’s aromatic (phenyl) hydrogen (C5-H5) with a distance of 2.57 Å and an angle of 160

o is present (

Figure 4a). Another weak hydrogen bonding is present in NEC-DDQ cocrystal between DDQ’s cyano group’s nitrogen (C21-N2) and aromatic (phenyl) hydrogen (C12-H9A) with a distance of 2.72 Å and an angle of 135.1

o. Similarly, DMB-DDQ cocrystal’s lattice is stabilized by weak hydrogen bonding occurring between DDQ’s quinone (C12-O2) and DMB’s aliphatic hydrogen (C7-H6B) with a distance of 2.53 Å and an angle of 131.5

o (

Figure 3b). Another weak hydrogen bonding in DMB-DDQ cocrystal occurs between DDQ’s cyano group’s nitrogen (C15-N2) and DMB’s aromatic hydrogen (C1-H1) with a distance of 2.71 Å and an angle of 167.2

o. Furthermore, the crystal lattices of NEC-DDQ and DMB-DDQ pairs are further stabilized by weak non-covalent Cl---Cl (Cl2-Cl2) and Cl---O (Cl3-O2) interactions with distances of 3.27 Å and 3.00 Å, respectively (

Figure 4a,b) and was previously observed in other DDQ-containing crystals [

38,

39]. In DPA-DDQ cocrystal, weak hydrogen bonding is present between DDQ’s cyano group’s nitrogen (C15-N1) and aromatic hydrogen (C6-H6) with a distance of 2.7 Å and an angle of 172

o. Another weak hydrogen bonding is present between DDQ’s quinone group (C20=O2) and aromatic hydrogen (C3-H8) with a distance of 2.51 Å and an angle of 154.6

o (

Figure 4c). DPA-DDQ cocrystal’s lattice is further stabilized by Cl---H (Cl1-H5) interaction 2.86 Å and an angle of 153.0

o.

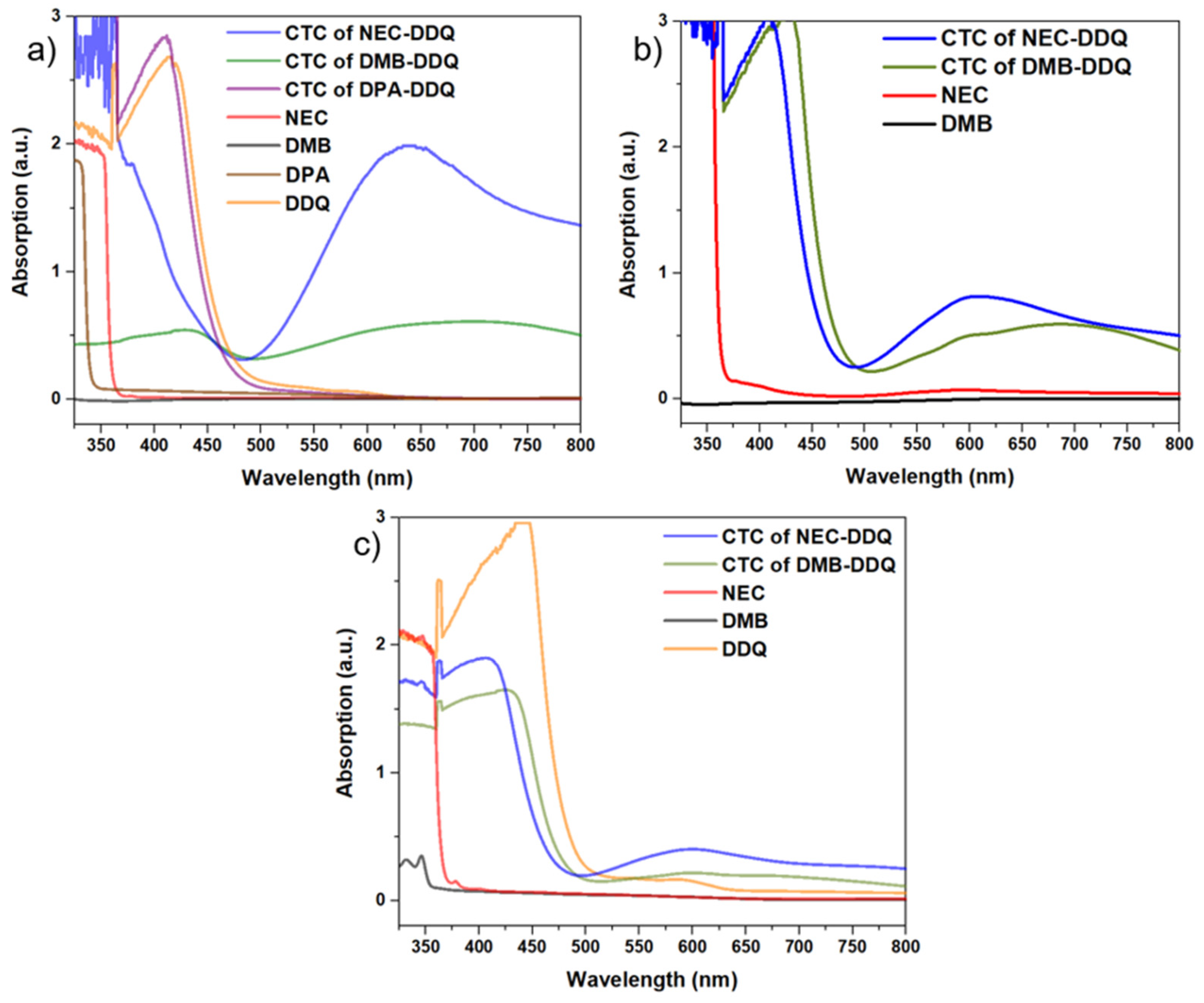

3.2. UV-Vis Investigation of CT Complexation

The formation of charge-transfer complexes (CTCs) is known to result in a distinct color change, resulting in an intense bathochromic shift in the UV-Vis spectrum [

27,

40,

41]. Thus, UV-Vis spectrophotometry was employed to further evidence the CTC complexations involving electron donors and DDQ (

Figure 5). As the solvent polarity plays a critical role in modulating the interaction between donor and acceptor molecules [

42], the influence of solvent polarity on CTC formation was systematically investigated using dichloromethane (DCM), tetrahydrofuran (THF) and acetonitrile (ACN) solvents. In this context, DCM, owing to its low polarity, proved to be the most effective solvent, facilitating CTC formation even at relatively low concentrations and displaying pronounced bathochromic shifts (

Figure 5a). ACN, possessing the highest polarity, resulted in less pronounced shifts in similar concentrations of CT-pairs (

Figure 5b). When DDQ is added to THF solvent a significant color change (from light orange to red) is attributed to THF’s ability to make

n-π* complexations through the lone pair electrons of oxygen with the benzene ring of DDQ, reducing CTC formation between the electron donors and DDQ [

43]. Thus, significantly more concentrated THF solutions of electron donor and DDQ was used to be able to observe comparable spectral changes (

Figure 5c).

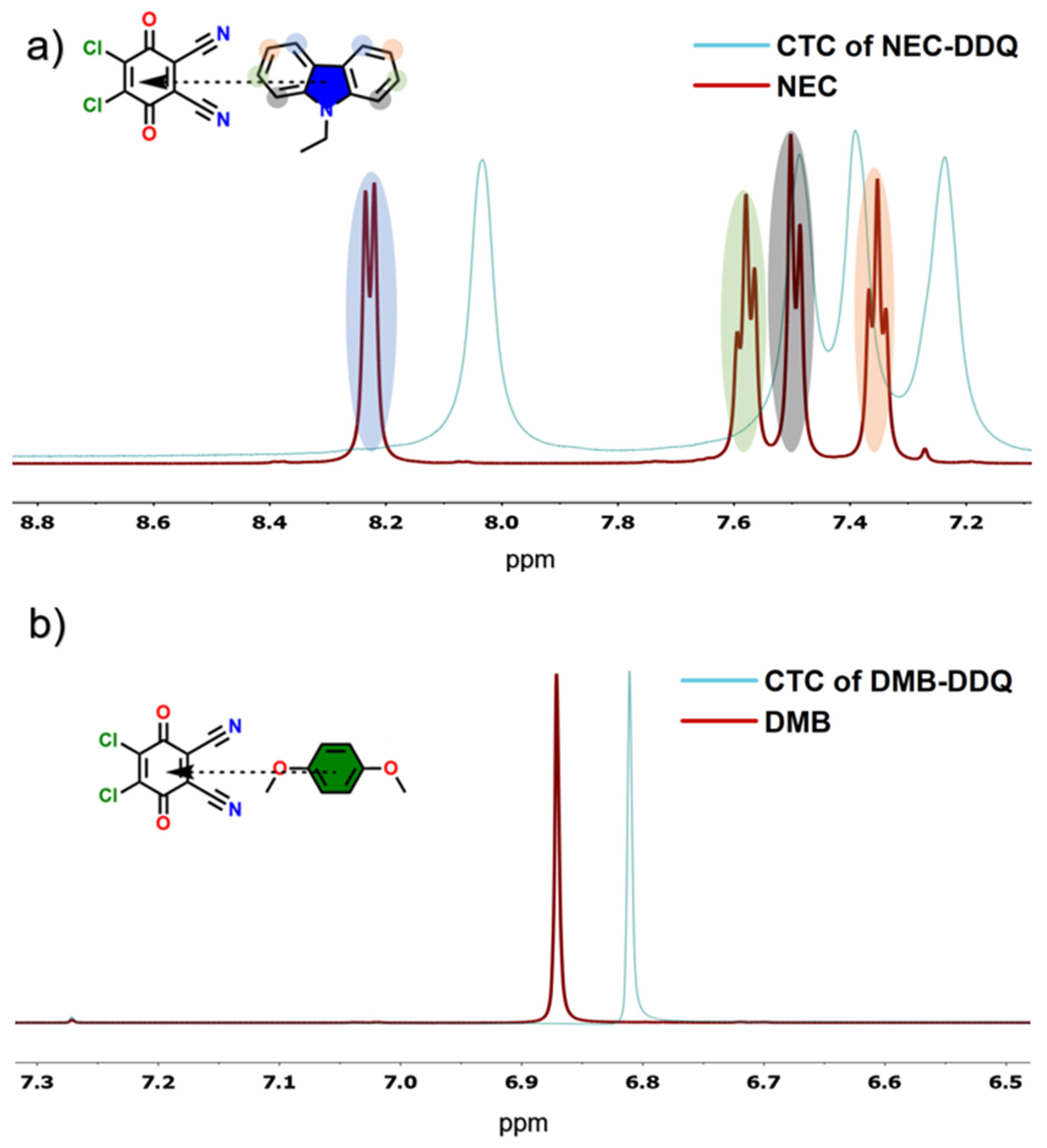

3.3. NMR Investigation of CT Complexation

Following UV-Vis spectroscopy, NMR spectroscopy was utilized to elucidate the charge-transfer complexations between electron donors and DDQ. These interactions induce notable alterations in the electron densities of the participating molecules, which are detectable by NMR spectroscopy [

44]. Initially, the

1H NMR spectra of DMB and NEC were recorded in CDCl

3 (

Figure 6) and in DMSO-d

6 (

Figure S3). High polarity of DMSO was found to significantly inhibit CTC formation, likely due to strong solvent-solute interactions that hinder effective π–π stacking between the electron-rich and electron-deficient species [

45]. Consequently, CDCl

3, a less polar solvent, was selected to facilitate the CTC formation. The resulting CT complexations were evident in the NMR spectra. As the concentration of DDQ increased a systematic upfield shift was observed for characteristic protons in both DMB (

Figure 6a) and NEC (

Figure 6b). In the

1H spectrum of NEC, aromatic protons located near the center of the CTC geometry exhibited more pronounced chemical shift changes compared to those on the molecular periphery, consistent with their greater involvement in the complexation process.

3.4. Photocationic Polymerization Using CTCs

Photoinitiated cationic polymerization of the above-mentioned monomers were investigated under different wavelengths. Due to the high solubility of all three CTCs in the monomers (CHO, IBVE and ECL) and the weaker CT bands observed in UV-Vis using dilute solutions of CT pairs, all the photopolymerization attempts were done as bulk systems (no solvent). Accordingly, to a negligible amount of CTC single crystals (less than 0.1 mmol), 10 mmol of monomer (~1 mL) was added and the mixture was irradiated on separate batches under visible LEDs, white-light LEDs or NIR emitting incandescent lamp for 8h. The resultant mixtures were precipitated into methanol and dried under vacuum for gravimetric determination (monomer conversion) and spectroscopic characterization (

1H NMR spectroscopy. NEC-DDQ and DMB-DDQ CT pairs successfully initiated the cationic polymerization of both CHO and IBVE under three different wavelength regions (visible, white and NIR). No ECL polymerization was observed using any CT pair. Control experiments conducted in the absence of light or any CTC photoinitiator resulted in no monomer conversion, demonstrating the crucial role of CT pairs (NEC and DMB) and light for successful polymerization. All the photopolymerization results are tabulated in

Table 3.

The monomer conversions achieved using NEC-DDQ and DMB-DDQ are generally in close correlation. The conversions percentages are comparable to previously obtained conversions using CTCs, with slightly on the lower side compared to onium salts [

26,

46]. DPA-DDQ CT pair did not yield any polymer under any wavelength irradiation, due to its weak -stacking resulting in no PET. Looking at the trend in the molecular weights of the polymers, NEC-DDQ tends to produce higher Mn polymeric species. This result can be attributed to the slightly stronger face-to-face stacking observed in NEC-DDQ pair, compared to DMB-DDQ, leading to a larger number of active centers. In accordance with the UV-Vis spectra the monomer conversions tend to increase with the lower wavelength irradiation (NIR to visible) as the absorptions are much higher in the visible region. Overall, the dispersity (Ɖ) values in the range of ~2-3.9 are typical for uncontrolled cationic polymerizations, which were previously observed by our research group, utilizing other CTC photoinitiators for the cationic polymerizations of these monomers [

19,

20].

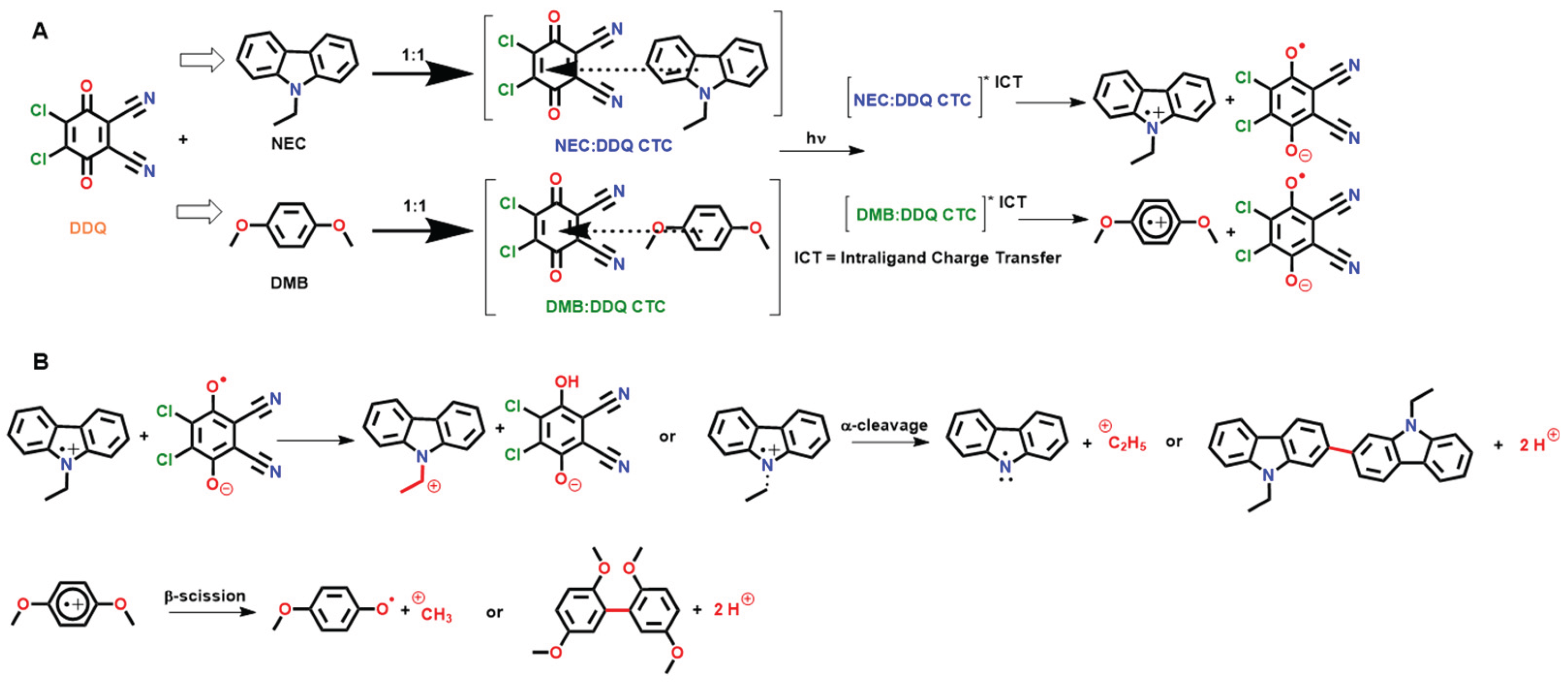

Plausible Mechanism for the Photocationic Polymerization

A plausible reaction mechanism is depicted in

Scheme 3. Accordingly, N-ethylcarbazole (NEC) and p-dimethoxybenzene (DMB) form ground-state CT complexes with the acceptor DDQ. In the concentrated solution (no solvent but only monomer), these donor–acceptor pairs co-facially stack, exhibiting intense CT absorption bands in the visible to NIR range. Upon irradiation with visible, white or NIR light, the CT complexes absorb a photon and undergoes intraligand charge transfer (ICT). This excitation prompts an electron transfer from the electron donor (NEC or DMB) to electron acceptor DDQ within the complex. The result is an electronically excited CT state that spontaneously separates into a radical ion pair, specifically, a donor radical cation and a DDQ radical anion. This photoinduced electron transfer (PET) is the crucial first step, creating the reactive ion pair that will initiate polymerization. Both NEC–DDQ and DMB–DDQ complexes show this behavior, whereas a weaker donor like diphenylacetylene (DPA) forms only a weak CT band and fails to generate ionic species resulting in no cationic photopolymerization (

Scheme 3A).

Upon photoexcitation, the donor radical cations (NEC

•+ or DMB

•+) and the acceptor radical anion (DDQ

•–) are formed in close proximity. NEC

•+ is a π-centered radical cation delocalized over the carbazole ring, with the positive charge largely on nitrogen, while DMB

•+ is an aromatic radical cation delocalized over the dimethoxybenzene ring. DDQ

•– is a resonance-stabilized semiquinone radical anion (

Scheme 3A).

In the next step (

Scheme 3B), the radical ion pair converts into an acidic species capable of initiating cationic chain-growth polymerization. The donor radical cation undergoes a fast-chemical reaction to generate a true cationic initiator (a Brønsted acid or a carbocation): NEC

•+ can fragment by α-cleavage of its N–C bond. The positive charge on the

N-ethylamino group induces cleavage of the N–CH

2- bond, ejecting a neutral carbazole radical and releasing an ethyl cation C

2H

5+.The ethyl cation is a potent Lewis-acidic species that can act like a proton in attacking monomers. An alternative path for NEC

•+ is dimerization: two NEC

•+ can couple at the 3- or 7-position, forming a bicarbazole and releasing by the release of two H

+ ions, as such reaction was previously observed in our research group when NEC was introduced to the powerful oxidizing agents such as bromine radical. A third path is the hydrogen abstraction of DDQ

•– from the ethyl unit of NEC

•+ resulting in DDQH and a N-ethyl cation that can also initiate cationic polymerization.

DMB•+ can undergo β-scission of an O–CH3 bond on the methoxy substituent. The result is a neutral 4-methoxyphenoxyl radical and a methyl cation (CH3+) as the leaving group. The methyl cation can act as a Brønsted superacid equivalent initiating cationic polymerization. In an alternative pathway, DMB•+ may undergo deprotonation at an aromatic ring carbon, ejecting an H⁺ and forming a resonance-stabilized radical. In either case, DMB•+ produces an acidic species: either CH3+ or H⁺.

DDQ•– radical anion helps facilitate acid formation and undergoes protonation by abstracting hydrogen from the donor radical cation or other trace donors. For instance, if NEC•+ releases an ethyl cation, the carbazole radical left behind can donate a hydrogen atom to DDQ•–, forming DDQH or its anion after electron rearrangement. DDQ•– may also eliminate a chloride: one of DDQ’s C–Cl bonds can cleave in the reduced state, expelling Cl-. The chloride anion can capture a proton (from donor or solvent) to yield HCl. The net outcome is the creation of a stable ion pair: a catalytically active cation C2H5+, CH3+ or H+ and a non-nucleophilic counter anion (e.g. Cl-, or the conjugate base of DDQ-H). This ion pair is analogous to a photo-generated onium acid in traditional photoinitiators.

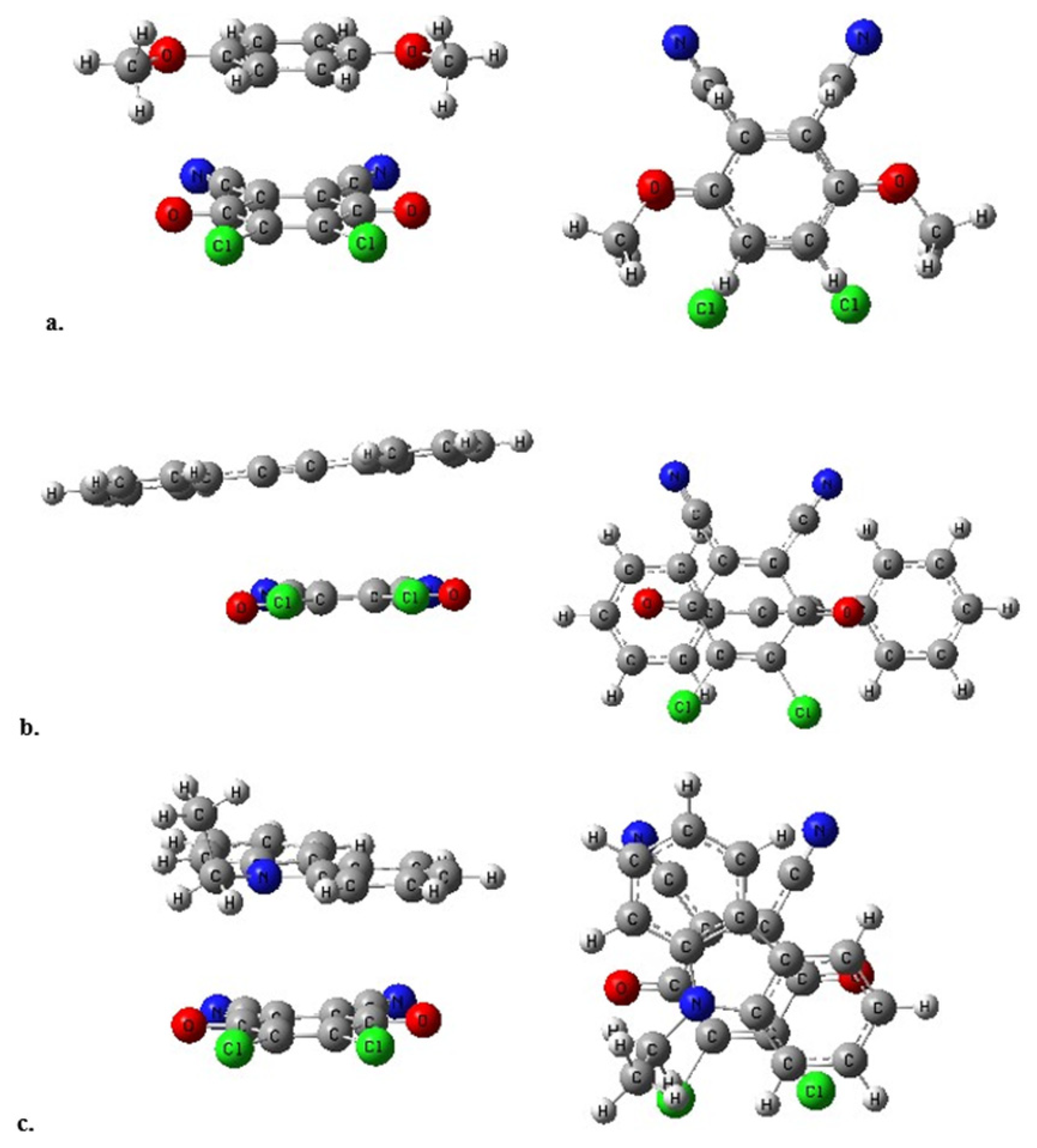

3.5. Computational Study

In order to obtain more insight into the structural and electronic states of DDQ-DMB, DDQ-DPA and DDQ-NEC interactions, the corresponding molecular complexes were modeled by using density functional theory (DFT). The geometries of organic molecules obtained with the B3LYP functional were determined to be in a good agreement with their experimental XRD structures [

47], that is why the geometry optimizations were carried out at B3LYP level of theory in 6-31+G(d,p) basis. All computations were performed in Gaussian ‘16 program package [

48]. The optimized geometries were shown in

Figure 7.

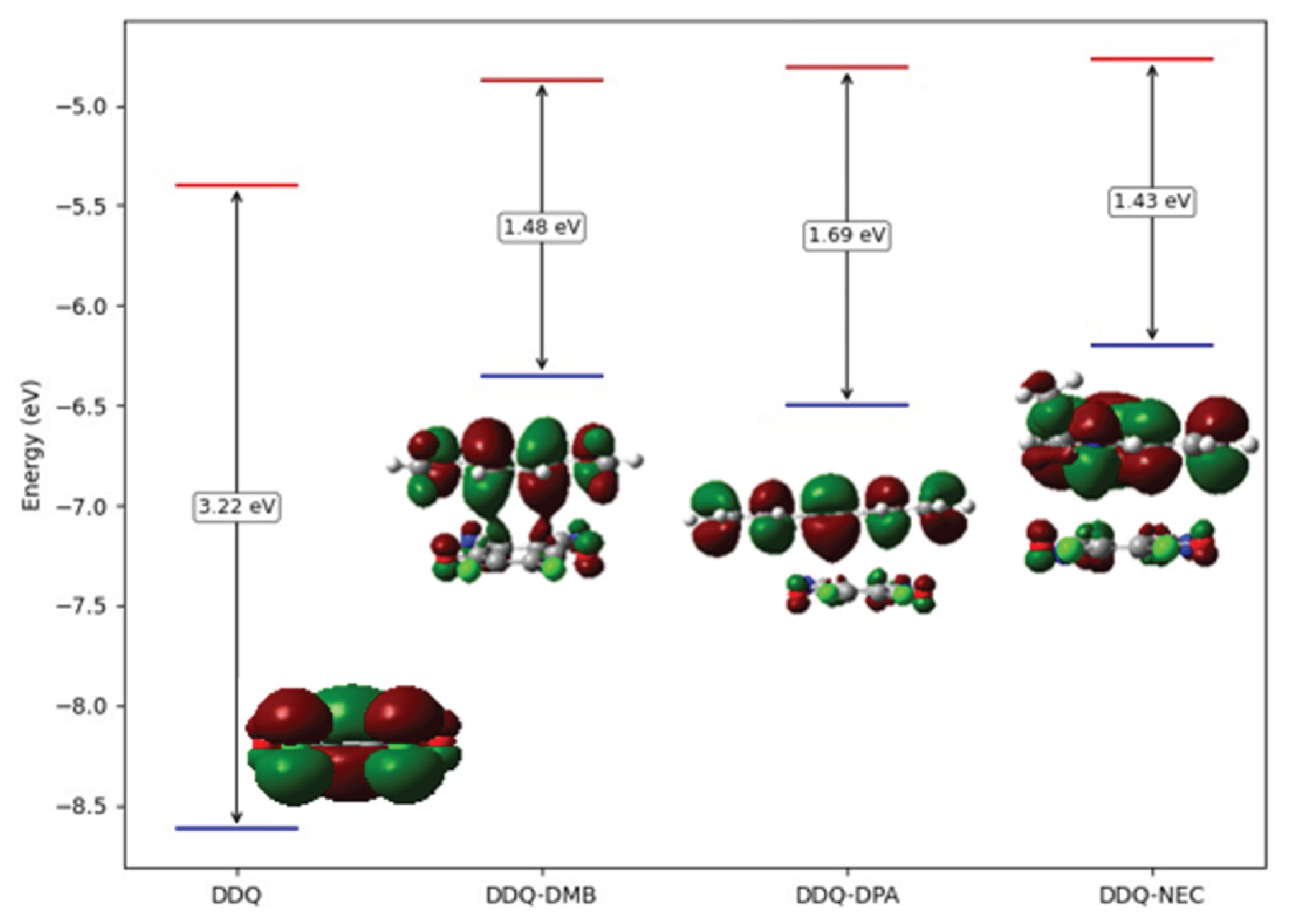

The stacked structures were confirmed for all structures. The interlayer spacings are all in 3.4-3.7 Å range. The spacings were predicted to be 3.5 Å in DDQ-DMB, 3.65 Å (average) in DDQ-DPA and 3.55 Å in DDQ-NEC complex. The frontier orbitals and the corresponding energy gaps were also shown in

Figure 8.

HOMO orbital was found localized on DMB, DPA and NEC in each molecular complex, in contrast, LUMO orbital was localized on DDQ unit in each case, that verifies the charge transfer complex structures between electron acceptor DDQ unit and electron donor DMB, DPA and NEC units. Upon comparison of the energy gaps, the weakest charge transfer interaction was predicted in DPA complex.

4. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this work is the first systematic study linking the structure of any CTC to its photoinitiation efficiency. By comparing the solid-state geometries obtained via SC-XRD, DFT calculations and photoinitiation activity of CT pairs, we demonstrate that tighter donor–acceptor stacking and higher donor HOMO energy correlate with stronger CT complexation and thus, higher photoinitiation rates. In contrast, the rigid DPA donor failed to transfer electron density efficiently to DDQ upon excitation, yielding no polymerization. These findings emphasize that both the electronic nature and spatial arrangement of the donor unit strongly influence the photochemical reactivity of the CT complex. The practical implication is that donor tuning offers a handle to control polymerization under mild irradiation conditions. This study demonstrates that by selecting donors with suitable redox properties and conjugation length, the absorption of the CT complex can be shifted to longer wavelengths, enabling photoinitiation even under NIR light. In our system, the more electron-rich NEC and DMB donors produced CT complexes that were active under relatively mild illumination, suggesting the potential to design effective NIR photoinitiators. At the same time, the failure of the ε-CL photopolymerization highlights the need to tailor the initiation system to the target monomer. Future research directions should build on these structure–reactivity insights, in particular, heterocyclic aromatics, extended π-systems, multi-donor molecules that can form strong CT interactions with DDQ or similar strong acceptors, in order to further red-shift the absorption and enhance photoactivity. Such studies are currently the focus of our research group.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: photos of the visible, white and NIR light photoreactors used in the photopolymerization experiments, respectively.; Figure S2: Photos of (left) dry PCHO precipitates obtained using DMB-DDQ CTC and (right) dry PIBVE precipitate obtained using NEC-DDQ CTC.; Figure S3: 1H-NMR spectra of the complexation between a) DMB and DDQ b) NEC and DDQ at various molar ratios in DMSO- d6 solvent. Table S1: Crystal Structure Report for NEC-DDQ CTC; Table S2: Crystal Structure Report for DMB-DDQ CTC; Table S3: Crystal Structure Report for DPA-DDQ CTC; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and H.C.K.; methodology, O.M., P.N., K.K. and H.C.K.; validation, K.K. and H.C.K.; formal analysis, K.K. and H.C.K.; investigation, K.K. and H.C.K.; data curation, K.K., P.N., B.S. and H.C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K. and H.C.K.; writing—review and editing, K.K., O.M. and H.C.K.; supervision, O.M., K.K. and H.C.K.; funding acquisition, K.K., P.N., O.M. and B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Turkish Council of Higher Education (YÖK) through project no TGA-2025- 46484. P.N. and O.M. thanks to the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK) under the BİDEB Co-Funded Brain Circulation program with a grant no: 121C351. Computing resources used in this work were provided by the National Center for High Performance Computing (UHeM) under grant number 1010722021.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goetz, K.P.; Vermeulen, D.; Payne, M.E.; Kloc, C.; McNeil, L.E.; Jurchescu, O.D. Charge-transfer complexes: new perspectives on an old class of compounds. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 3065–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharfar, M.; Hillier, A.C.; Mao, G. Charge-Transfer Complexes: Fundamentals and Advances in Catalysis, Sensing, and Optoelectronic Applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2406083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, S.; Chiavazza, E.; Ribotta, V.; Daniele, P.G.; Barolo, C.; Giacomino, A.; Vione, D.; Malandrino, M. Charge-transfer complexes of 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone with amino molecules in polar solvents. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 149, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldaroti, H.H.; Gadir, S.A.; Refat, M.S.; Adam, A.M.A. Charge-transfer interaction of drug quinidine with quinol, picric acid and DDQ: Spectroscopic characterization and biological activity studies towards understanding the drug-receptor mechanism. J Pharm Anal 2014, 4, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.T.; Ong, Y.K. Electrical properties of polyvinylpyridine — DDQ charge transfer complexes. Solid State Commun. 1986, 57, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varukolu, M.; Palnati, M.; Nampally, V.; Gangadhari, S.; Vadluri, M.; Tigulla, P. New Charge Transfer Complex between 4-Dimethylaminopyridine and DDQ: Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization, DNA Binding Analysis, and Density Functional Theory (DFT)/Time-Dependent DFT/Natural Transition Orbital Studies. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, M.L.; Blackstock, S.C. Nitrosamine/2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano- 1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ) Complexes and the Formation of Donor-Appended DDQ Chains in the Solid State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 11343–11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, S.; Khan, I.M. Charge transfer complexes: Emerging and promising colorimetric real-time chemosensors for hazardous materials. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottenberg, A.; Brandon, R.L.; Browne, M.E. Physical Properties of some Charge-transfer Complexes of 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyanobenzo-quinone. Nature 1964, 201, 1119–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.-L.; Zhou, C.-M.; Zhao, X.; Xu, J.-Y.; Jiang, X.-K. EPR Study on the Complex Formed by Charge-Transfer Process between Ground-state Acceptor 2, 3-Dicyano-5, 6-dichloro-1, 4-benzoquinone and Some Donors and on Cation Radical of Perylene (or Pyrene). Chin. J. Chem. 2001, 19, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhai, H.; Hu, P.; Jiang, H. The Stoichiometry of TCNQ-Based Organic Charge-Transfer Cocrystals. Crystals 2020, 10, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonari, M.S.; Rigin, S.; Lesse, D.; Timofeeva, T.V. Co-crystals of polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons and 9H-carbazole with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone acceptor: Varieties in crystal packing, Hirshfeld surface analysis and quantum-chemical studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1278, 134900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Zheng, L.; Xu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, F.; Wang, W.; Ou, C.; Dong, X. Organic Charge-Transfer Complexes for Near-Infrared-Triggered Photothermal Materials. Small Struct. 2023, 4, 2200220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, D.; Ngo, D.; Bui, A.; Pojman, J. Charge transfer complexes as dual thermal/photo initiators for free-radical frontal polymerization. Journal of Polymer Science 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietlin, C.; Schweizer, S.; Xiao, P.; Zhang, J.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Graff, B.; Fouassier, J.-P.; Lalevée, J. Photopolymerization upon LEDs: new photoinitiating systems and strategies. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 3895–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, K. A green and fast method for PEDOT: Photoinduced step-growth polymerization of EDOT. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, 182, 105464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaarslan, A.; Kaya, K.; Jockusch, S.; Yagci, Y. Phenacyl Bromide as a Single-Component Photoinitiator: Photoinduced Step-Growth Polymerization of N-Methylpyrrole and N-Methylindole. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202208845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, S.; Xu, J.; Boyer, C. Utilizing the electron transfer mechanism of chlorophyll a under light for controlled radical polymerization. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, K.; Kiliclar, H.C.; Yagci, Y. Photochemically generated ionic species for cationic and step-growth polymerizations. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 190, 112000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, K.; Kreutzer, J.; Yagci, Y. Diphenylphenacyl sulfonium salt as dual photoinitiator for free radical and cationic polymerizations. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2018, 56, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Jiang, F.; Crivello, J.V. Photosensitized Onium-Salt-Induced Cationic Polymerization with Hydroxymethylated Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 2369–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachet, B.; Lecompère, M.; Croutxé-Barghorn, C.; Burr, D.; L'Hostis, G.; Allonas, X. Highly reactive photothermal initiating system based on sulfonium salts for the photoinduced thermal frontal cationic polymerization of epoxides: a way to create carbon-fiber reinforced polymers. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 41915–41920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Szillat, F.; Fouassier, J.P.; Lalevée, J. Remarkable Versatility of Silane/Iodonium Salt as Redox Free Radical, Cationic, and Photopolymerization Initiators. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 5638–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehmel, B.; Brömme, T.; Schmitz, C.; Reiner, K.; Ernst, S.; Keil, D. NIR-Dyes for Photopolymers and Laser Drying in the Graphic Industry. In Dyes and Chromophores in Polymer Science; 2015; pp. 213–249.

- Schmitz, C.; Pang, Y.; Gülz, A.; Gläser, M.; Horst, J.; Jäger, M.; Strehmel, B. New High-Power LEDs Open Photochemistry for Near-Infrared-Sensitized Radical and Cationic Photopolymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4400–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Kaya, K.; Garra, P.; Fouassier, J.-P.; Graff, B.; Yagci, Y.; Lalevée, J. Sulfonium salt based charge transfer complexes as dual thermal and photochemical polymerization initiators for composites and 3D printing. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 4690–4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garra, P.; Fouassier, J.P.; Lakhdar, S.; Yagci, Y.; Lalevée, J. Visible light photoinitiating systems by charge transfer complexes: Photochemistry without dyes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2020, 107, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubo, T.; Iwatsuki, S.; Tamashita, Y. Studies on the Charge-Transfer Complex and Polymerization. XVII. React. Charg. -Transf. Complex Altern. Radic. Copolym. Vinyl Ethers Maleic Anhydride. Macromol. 1968, 1, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizal, G.; Yaḡci, Y.; Schnabel, W. Charge-transfer complexes of pyridinium ions and methyl- and methoxy-substituted benzenes as photoinitiators for the cationic polymerization of cyclohexene oxide and related compounds. Polymer 1994, 35, 2428–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker, S.; SAINT, S. Bruker AXS Inc. Madison, Wisconsin, USA 2002.

- APEX, B. SAINT, and SADABS. Bruker AXS Inc. Madison, WI, USA 2009.

- Altomare, A.; Burla, M.C.; Camalli, M.; Cascarano, G.L.; Giacovazzo, C.; Guagliardi, A.; Moliterni, A.G.G.; Polidori, G.; Spagna, R. SIR97: a new tool for crystal structure determination and refinement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1999, 32, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick G, M. SHELXL-97. Program for crystal structure refinement 1997.

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: from visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Yu, W.-T.; Hong, L.; Lin, X.-Y.; Yu, Z.-P. The Charge-Transfer Complex 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)carbazole-2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (1/1) (HEK-DDQ). Acta Crystallographica Section C 1996, 52, 2274–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QI, F.; DONG, X.; WENTAO, Y.; HONG, C.; JIAN, Z.; YURONG, M.; QINGSHAN, L. The charge transfer of HEK-DDQ and photoinduced charge transfer of HEK-TCNQ. Acta Chim. Sin. 1997, 55, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Lieffrig, J.; Jeannin, O.; Shin, K.-S.; Auban-Senzier, P.; Fourmigué, M. Halogen Bonding Interactions in DDQ Charge Transfer Salts with Iodinated TTFs. Crystals 2012, 2, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holthoff, J.M.; Weiss, R.; Rosokha, S.V.; Huber, S.M. “Anti-electrostatic” Halogen Bonding between Ions of Like Charge. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2021, 27, 16530–16542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, M.; Hu, J.; Wang, X.; Jie, J.; Guo, Q.; Chen, C.; Xia, A. Ultrafast Investigation of Intramolecular Charge Transfer and Solvation Dynamics of Tetrahydro[5]-helicene-Based Imide Derivatives. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nampally, V.; Palnati, M.K.; Baindla, N.; Varukolu, M.; Gangadhari, S.; Tigulla, P. Charge Transfer Complex between O-Phenylenediamine and 2, 3-Dichloro-5, 6-Dicyano-1, 4-Benzoquinone: Synthesis, Spectrophotometric, Characterization, Computational Analysis, and its Biological Applications. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 16689–16704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanikachalam, V.; Arunpandiyan, A.; Jayabharathi, J.; Ramanathan, P. Photophysical properties of the intramolecular excited charge-transfer states of π-expanded styryl phenanthrimidazoles – effect of solvent polarity. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 6790–6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Atak, F.B.; Yakuphanoglu, F. Synthesis and refractive index dispersion properties of the N,N′,N″-trinaphthylmethyl melamine–DDQ complex thin film. Opt. Mater. 2007, 29, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriessen, H.J.M.; Laarhoven, W.H.; Nivard, R.J.F. Nuclear magnetic resonance study of charge-transfer complexes of 1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, picric acid, and fluoranil with methoxy- and methyl-substituted benzenes and biphenyls. Indication of the structure of the complexes in solution. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2 1972, 861-868. [CrossRef]

- Inan, D.; Dubey, R.K.; Westerveld, N.; Bleeker, J.; Jager, W.F.; Grozema, F.C. Substitution Effects on the Photoinduced Charge-Transfer Properties of Novel Perylene-3,4,9,10-tetracarboxylic Acid Derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 4633–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, K.; Kreutzer, J.; Yagci, Y. A Charge-Transfer Complex of Thioxanthonephenacyl Sulfonium Salt as a Visible-Light Photoinitiator for Free Radical and Cationic Polymerizations. ChemPhotoChem 2019, 3, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odajima, T.; Ashizawa, M.; Konosu, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Mori, T. The impact of molecular planarity on electronic devices in thienoisoindigo-based organic semiconductors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 10455–10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01, Wallingford, CT, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).