Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

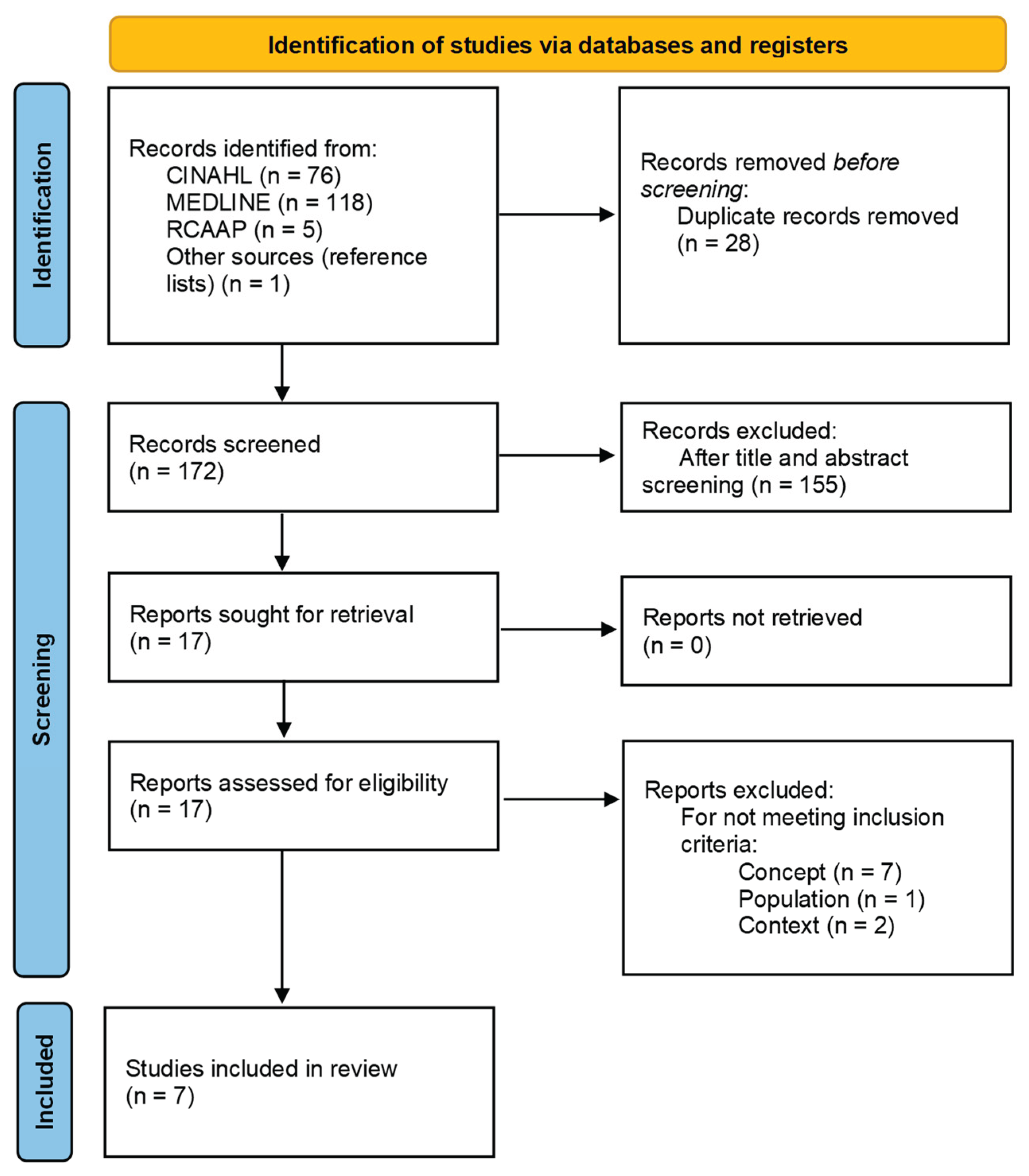

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Comprehensive Analysis

2.5. Reporting the Results

3. Results

Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PACU JBI RCAAP OSA PRISMA-ScR PCC QCRI PRISMA PCA etCO2 USA |

Post-Anesthesia Care Unit Joanna Briggs Institute Open Access Scientific Repositories of Portugal Obstructive Sleep Apnea Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews Population/Concept/Context Qatar Computing Research Institute Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews e Meta-Analyses Patient Controlled-Analgesia End-tidal Carbon Dioxide Concentration United States of America |

Appendix A. Search Strategy

| Search | Search terms | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | nurs*[Title/Abstract] | 546,738 |

| #2 | "Postanesthesia Nursing"[MeSH Terms] OR "Nurses"[MeSH Terms] OR "Nursing"[MeSH Terms] | 338,351 |

| #3 | "nurs*"[Title/Abstract] OR "Postanesthesia Nursing"[MeSH Terms] OR "Nurses"[MeSH Terms] OR "Nursing"[MeSH Terms] | 696,705 |

| #4 | "capno*"[Title/Abstract] OR "respiratory monitoring"[Title/Abstract] OR "carbon dioxide"[Title/Abstract] OR "end tidal carbon dioxide"[Title/Abstract] OR "respiratory assessment"[Title/Abstract] OR "respiratory complications"[Title/Abstract] | 76,533 |

| #5 | "Capnography"[MeSH Terms] OR "blood gas monitoring, transcutaneous"[MeSH Terms] OR "Carbon Dioxide"[MeSH Terms] OR "Pulmonary Ventilation"[MeSH Terms] OR "signs and symptoms, respiratory"[MeSH Terms] | 322,554 |

| #6 | "capno*"[Title/Abstract] OR "respiratory monitoring"[Title/Abstract] OR "Carbon Dioxide"[Title/Abstract] OR "end tidal carbon dioxide"[Title/Abstract] OR "respiratory assessment"[Title/Abstract] OR "respiratory complications"[Title/Abstract] OR "Capnography"[MeSH Terms] OR "blood gas monitoring, transcutaneous"[MeSH Terms] OR "Carbon Dioxide"[MeSH Terms] OR "Pulmonary Ventilation"[MeSH Terms] OR "signs and symptoms, respiratory"[MeSH Terms] | 366,211 |

| #7 | "Postanesthesia"[Title/Abstract] OR "Recovery"[Title/Abstract] OR "Postoperative"[Title/Abstract] OR "PACU"[Title/Abstract] OR "Post anesthesia care unit"[Title/Abstract] OR "Immediate postoperative"[Title/Abstract] | 1,188,357 |

| #8 | "Postoperative Period"[MeSH Terms] OR "Postoperative Care"[MeSH Terms] OR "Recovery Room"[MeSH Terms] | 122,244 |

| #9 | "Postanesthesia"[Title/Abstract] OR "Recovery"[Title/Abstract] OR "Postoperative"[Title/Abstract] OR "PACU"[Title/Abstract] OR "Post anesthesia care unit"[Title/Abstract] OR "Immediate postoperative"[Title/Abstract] OR "Postoperative Period"[MeSH Terms] OR "Postoperative Care"[MeSH Terms] OR "Recovery Room"[MeSH Terms] | 1,244,717 |

| #10 | ("nurs*"[Title/Abstract] OR ("Postanesthesia Nursing"[MeSH Terms] OR "Nurses"[MeSH Terms] OR "Nursing"[MeSH Terms])) AND ("capno*"[Title/Abstract] OR "respiratory monitoring"[Title/Abstract] OR "Carbon Dioxide"[Title/Abstract] OR "end tidal carbon dioxide"[Title/Abstract] OR "respiratory assessment"[Title/Abstract] OR "respiratory complications"[Title/Abstract] OR ("Capnography"[MeSH Terms] OR "blood gas monitoring, transcutaneous"[MeSH Terms] OR "Carbon Dioxide"[MeSH Terms] OR "Pulmonary Ventilation"[MeSH Terms] OR "signs and symptoms, respiratory"[MeSH Terms])) AND ("Postanesthesia"[Title/Abstract] OR "Recovery"[Title/Abstract] OR "Postoperative"[Title/Abstract] OR "PACU"[Title/Abstract] OR "Post anesthesia care unit"[Title/Abstract] OR "Immediate postoperative"[Title/Abstract] OR ("Postoperative Period"[MeSH Terms] OR "Postoperative Care"[MeSH Terms] OR "Recovery Room"[MeSH Terms])) | 277 |

| #11 | #10 FILTERS: English, Portuguese, Spanish |

255 |

| #12 | #10 FILTERS: English, Portuguese, Spanish; Adult: 19+ years |

118 |

| Search | Search terms | Results |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | TI nurs* OR AB nurs* | 624,190 |

| S2 | (MH "Nurses+") OR (MH "Perianesthesia Nursing") OR (MH "Perioperative Nursing") | 254,721 |

| S3 | S1 OR S2 | 719,008 |

| S4 | TI capno* OR AB capno* OR TI “respiratory monitoring” OR AB “Respiratory monitoring” OR TI “carbon dioxide” OR AB “carbon dioxide” OR TI “end tidal carbon dioxide” OR AB “end tidal carbon dioxide” OR TI “respiratory assessment” OR AB “respiratory assessment” OR TI “respiratory complications” OR AB “respiratory complications” | 9,641 |

| S5 | (MH "Capnography") OR (MH "Carbon Dioxide") OR (MH "Signs and Symptoms, Respiratory+") OR (MH "Blood Gas Monitoring, Transcutaneous") | 44,729 |

| S6 | S4 OR S5 | 50,121 |

| S7 | TI “postanesthesia” OR AB “postanesthesia” OR TI “recovery” OR AB “recovery” OR TI “postoperative” OR AB “postoperative” OR TI PACU OR AB PACU OR TI “post anesthesia care unit” OR AB “post anesthesia care unit” OR TI “immediate postoperative” OR AB “immediate postoperative” | 212,894 |

| S8 | (MH "Post Anesthesia Care Units") OR (MH "Post Anesthesia Care") OR (MH "Postoperative Care") OR (MH "Anesthesia Recovery") OR (MH "Postoperative Period") | 42,008 |

| S9 | S7 OR S8 | 234,949 |

| S10 | S3 AND S6 AND S9 | 205 |

| S11 | S10 (Limited to English, Portuguese, and Spanish languages) | 197 |

| S12 | S10 (Limited to English, Portuguese, and Spanish languages; age group: all adults) | 74 |

| Search | Search terms | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | capnografia AND enfermagem | 5 |

Appendix B. Data Extraction from the Studies

| Study | Reference Number, First Author’s Surname, Year of Publication, Country | Type of study | Objetive(s) | Population | Context | Concept (Barriers and Facilitators use of capnography for respiratory monitoring by nurses in Phase I PACU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | [24] Hutchison et al. (2008), United States of America (USA) | Randomized prospective study | Determine whether capnography used in isolation is more sensitive than pulse oximetry (with assessment of respiratory rate through observation or auscultation) | 54 adult patients following orthopedic surgery, monitored for respiratory depression using capnography by nurses | PACU and general nursing care unit |

Barriers: - Capnography requires more time from professionals to be implemented; - Nurses perceived greater difficulty in patient adherence due to limitations in daily activities, such as walking in the postoperative period. Facilitators: - Educating patients to facilitate their adherence to monitoring (for example, about the importance of the cannula and the meaning of the alarms); - The alarm produced by the capnography monitor led to a quicker response from nurses; - Allowed early identification of changes in respiratory function. |

| S2 | [25] McCarter et al. (2008), USA | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional study | Evaluate the effectiveness of monitoring in the postoperative period in patients with opioid PCA | 634 adult postoperative patients receiving PCA with opioids, monitored with capnography by nurses | Postoperative period (Phase I and Phase II) |

Facilitators: - Increased nurse awareness of respiratory changes; - Increased effectiveness of nursing interventions to minimize respiratory discomfort related to PCA; - Increased nurse confidence due to effective monitoring; - Quick response from the team to prevent serious consequences; - Increased perceived patient safety during this period. |

| S3 | [26] Lakdawala et al. (2017), USA | Quality improvement project | Assess patients using the STOP-Bang screening tool; Compare high-risk and low-risk groups with respect to respiratory complications; Use and evaluate capnography in the postoperative period; Evaluate nurses' perception of the OSA care protocol; Assess patient satisfaction with the OSA care protocol. |

161 adult neuro-surgical patients screened for OSA using STOP-Bang, monitored with capnography by nurses | Preoperative unit, PACU, and neuro-surgery unit |

Barriers: - Nurses observed greater patient resistance to adherence to capnography devices due to discomfort caused by the cannula and the nuisance of the alarm; - Nurses needed more knowledge about problem-solving methods related to the use of capnography in patients with OSA, to improve interpretation skills and response to each situation, as well as the indications for capnography and monitoring techniques. Facilitators: - Capnography proved to identify early signs of respiratory depression (such as apnea and snoring episodes), allowing for quick intervention; - Need to educate patients on the importance of using the device to ensure safety, raising awareness about the significance of monitoring, promoting adherence. |

| S4 | [27] Jungquist et al. (2019), USA | Prospective observational study | Explore the effectiveness of using pulse oximetry, capnography, and minute ventilation to identify and anticipate opioid-induced respiratory depression in the post-anesthesia period | 60 adult patients in PACU after spine, neck, hip, or knee surgery, monitored by nurses for opioid-induced respiratory depression | PACU |

Barriers: - Nurses' perception of patient non-adherence, related to discomfort, mask removal for nursing care, and other activities like eating and speaking; - Need for nurse training to instigate a change in the monitoring paradigm, reflecting limited knowledge of the technique and indications for capnography. |

| S5 | [28] Scully (2019), USA | Quality im-provement project (with mixed method) | Identify undiagnosed and high-risk patients with OSA in the preoperative period using the STOP-Bang screening tool; Train PACU nurses to recognize hypoventilation through capnography and intervene to prevent respiratory complications; Implement Practice Recommendation number 10 from |

314 adult patients diagnosed with OSA, monitored by multidisciplinary team | PACU |

Facilitators: - Training for professionals (introduction to capnography and monitoring); - Increased confidence in using capnography helped stimulate critical thinking (by applying it to other patients beyond the OSA population); - Improvement in care quality and patient safety are driving forces behind change; - Regular communication of results (via audit) motivated the team and promoted the implementation process; |

| the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (screening for OSA and monitoring of etCO2 in patients with OSA) | - Promoting sustainability by involving training and raising nurse awareness to provide the best care, integrating capnography monitoring into clinical practice; - Allowed the nurse to intervene before respiratory complications occurred. |

|||||

| S6 | [29] Atherton et al. (2022), USA | Quantitative, descriptive-correlational, and longitudinal study | Evaluate the effectiveness of an educational program on ventilatory patterns using devices that assess dioxid carbon levels in postoperative patients | 176 nurses | PACU |

Facilitators: - After the educational program, nurses reported greater confidence and consequent security in using etCO2 and transcutaneous carbon dioxide monitoring and interpreting the values; - Prior knowledge and training with etCO2 monitoring. |

| S7 | [19] Potvin et al. (2022), France | Randomized, controlled, prospective study | Study the rate of patients with alveolar hypoventilation before tracheal extubation or removal of the laryngeal mask through continuous capnography monitoring in the PACU | 52 adult patients with endotracheal tube orlaryngeal mask, monitored by nurses | PACU |

Facilitators: - Nurse training facilitated the accurate interpretation of capnography results and the overall layout of monitoring systems; - Training should be coupled with a standardized respiratory monitory protocol to ensure effective use of capnography; - Standard monitoring, together with capnography, can improve patient safety by providing a comprehensive assessment of respiratory function, allowing early detection of respiratory complications. |

References

- Ganter, M.T.; Blumenthal, S.; Dübendorfer, S.; Brunnschweiler, S.; Hofer, T.; Klaghofer, R.; Zollinger, A.; Hofer, C. The length of stay in the post-anaesthesia care unit correlates with pain intensity, nausea and vomiting on arrival. Perioper Med. 2014, 3, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Mourão, J.; Pereira, L.; Alves, C.; Andrade, N.; Cadilha, S.; Perdigão, L. Indicadores de segurança e qualidade em anestesiologia. Rev. Soc. Port. Anestesiol. 2018, 27, 23–27. [CrossRef]

- Jaensson, M.; Nilsson, U.; Dahlberg, K. Methods and timing in the assessment of postoperative recovery: a scoping review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 129, 92–103. [CrossRef]

- Mert, S. The significance of nursing care in the post-anesthesia care unit and barriers to care. Intensive Care Res. 2023, 3, 272-281. [CrossRef]

- Karcz, M.; Papadakos, P.J. Respiratory complications in the postanesthesia care unit: A review of pathophysiological mechanisms. Can J Respir Ther. 2013, 49, 21-29. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26078599/.

- Sampaio, A.; Bernardino, A.; Campos, A.C.; Eufrásio, A.; Almeida, A.L.; Raimundo, A.; et al. Manual de cuidados pós-anestésicos, 2017. Available from: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/84995558.pdf.

- Clifford, T.L. Phase I and phase II recovery. In Perianesthesia nursing care: A bedside guide for safe recovery; Stannard, D., Krenzischek, D., Duarte, O., Martins, O., Eds.; Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2016, pp. 19-22. Available from: https://books.google.pt/books?hl=pt-PT&lr=&id=2hzrDAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA19&dq=phase+I+and+phase+II+recovery+clifford&ots=El0k6Q2nLC&sig=DfKr7iEIBVYlcfG0eEIYijXSRTo&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=phase%20I%20and%20phase%20II%20recovery%20clifford&f=false.

- Dahlberg, K.; Brady, J.M.; Jaensson, M.; Nilsson, U.; Odom-Forren, J. Education, competence, and role of the nurse working in the PACU: An international survey. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021, 36, 224-331. [CrossRef]

- Eikermann, M.; Santer, P.; Ramachandran, S.K.; Pandit, J. Recent advances in understanding and managing postoperative respiratory problems. F1000Res. 2019, 8, 197. [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D.; Mosieri, C.; Kallurkar, A.; Pham, A.D.; Okada, L.K.; Kaye, R.J.; Cornett, E.M.; Fox, C.J.; Urman, R.D.; Kaye, A.D. Perioperative strategies for the reduction of postoperative pulmonary complications. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020, 34, 153-166. [CrossRef]

- Fink, R.J.; Mark J.B. Monitoração anestésica padrão e dispositivos. In Fundamentos de anestesiologia clínica; Barash, P.; Cullen, B.; Stoelting, R.; Cahalan, M.; Stock, M.; Ortega, R.; et al., Eds. Artmed Editora, Porto Alegre, 2017, pp. 277-297. Available from: https://books.google.pt/books?hl=pt-PT&lr=&id=LRcuDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=livro+anestesiologia+clinica&ots=6As0nnIfEP&sig=LUuMxn1tGjatPzupHHzcM36NvC4&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=livro%20anestesiologia%20clinica&f=false.

- Kerslake, I.; Kelly, F. Uses of capnography in the critical care unit. BJA Educ. 2017, 17, 178-183. [CrossRef]

- Chung, F.; Wong, J.; Mestek, M.L.; Niebel, K.H.; Lichtenthal, P. Characterization of respiratory compromise and the potential clinical utility of capnography in the post anesthesia care unit: a blinded observational trial. J Clin Monit Comput. 2020, 34, 541-551. [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Nagappa, M.; Wong, J.; Singh, M.; Wong, D.; Chung, F. Continuous pulse oximetry and capnography monitoring for postoperative respiratory depression and adverse events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2017, 125, 2019-2029. [CrossRef]

- Medtronic. Clinical society guidelines for Capnography monitoring, 2019. Available from: https://asiapac.medtronic.com/content/dam/covidien/library/emea/en/product/capnography-monitoring/18-emea-cs-guidelines-for-capnography-2922293.pdf.

- Royal College of Anaesthetists. Chapter 4: Guidelines for the provision of anaesthetic services for postoperative care 2019. GPAS Editorial, 2019. Available from: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2020-02/GPAS-2019-04POSTOP.pdf.

- Broens, S.; Prins, S.; Kleer, D.; Niesters, M.; Dahan, A.; Velzen, M. Postoperative respiratory state assessment using the integrated pulmonary index (IPI) and resultant nurse interventions in the post-anesthesia care unit: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Monit Comput. 2021, 35, 1093-1102. [CrossRef]

- Wilks, C.; Foran, P. Capnography monitoring in the post anaesthesia care unit (PACU). J Perioper Nurs. 2021, 34, 29-35. [CrossRef]

- Potvin, J.; Etchebarne, I.; Soubiron, L.; Biais, M.; Roullet, S.; Nouette-Gaulain, K. Effects of capnometry monitoring during recovery in the post-anaesthesia care unit: a randomized controlled trial in adults (CAPNOSSPI). J Clin Monit Comput. 2022, 36, 379-385. [CrossRef]

- Wollner, E.; Nourian, M.M.; Booth, W.; Conover, S.; Law, T.; Lilaonitkul, M.; Gelb, A.W.; Lipnick, M.S. Impact of capnography on patient safety in high-and low-income settings: A scoping review. Br J Anaesth. 2020, 125, 88-103. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In JBI manual for evidence synthesis; Aromatis, E.; Munn, Z., Eds. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Int. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Sci. 2015, 53, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, R.; Rodriguez, L. Capnography and respiratory depression. Am J Nurs. 2008, 108, 35-39. [CrossRef]

- McCarter, T.; Shaik, Z.; Scarfo, K.; Thompson, L.J. Capnography monitoring enhances safety of postoperative patient-controlled analgesia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2008, 1, 28-35. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4115301/.

- Lakdawala, L.; Dickey, B.; Alrawashdeh, M. Obstructive sleep apnea screening among surgical patients: A quality improvement project. J Perianesth Nurs. 2018, 33, 814-821. [CrossRef]

- Jungquist, C.R.; Chandola, V.; Spulecki, C.; Nguyen, K.V.; Crescenzi, P.; Tekeste, D.; Sayapaneni, P.R. Identifying patients experiencing opioid-induced respiratory depression during recovery from anesthesia: The application of electronic monitoring devices. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2019, 16, 186-194. [CrossRef]

- Scully, K.R.; Rickerby, J.; Dunn, J. Implementation science: Incorporating obstructive sleep apnea screening and capnography into everyday practice. J Perianesth Nurs. 2020, 35, 7-16. [CrossRef]

- Atherton, P.; Jungquist, C.; Spulecki, C. An educational intervention to improve comfort with applying and interpreting transcutaneous CO2 and end-tidal CO2 monitoring in PACU. J Perianesth Nurs. 2022, 37, 781-786. [CrossRef]

- Sajith, B. Respiratory depression: A case study of a postoperative patient with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018, 22, 453-456. [CrossRef]

- Ruskin, K.J.; Bliss, J.P. Alarm fatigue and patient safety. Anesth Patient Saf Found. 2019, 34, 1-6. Available from: https://www.apsf.org/article/alarm-fatigue-and-patient-safety/.

- Oliveira, A.E.C.; Machado, A.B.; Santos, E.D.; Almeida, E.B. Fadiga de alarmes e as implicações para a segurança do paciente. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018, 71, 3211-3216. [CrossRef]

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Population | Nurses |

| Concept | Barriers and facilitators to the use of capnography for respiratory monitoring |

| Context | Phase I PACU |

| Reference Number | First Author’s Surname, Year of Publication | Population | Context | Concept (Barriers and Facilitators use of capnography for respiratory monitoring by nurses in Phase I PACU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [24] | Hutchison et al. (2008) | 54 adult patients following orthopedic surgery, monitored for respiratory depression using capnography by nurses | PACU and general nursing care unit |

Barriers: - Capnography requires more time from professionals to be implemented; - Nurses perceived greater difficulty in patient adherence due to limitations in daily activities. Facilitators: - Educating patients to facilitate their adherence to monitoring; - The alarm produced by the capnography monitor led to a quicker response from nurses; - Allowed early identification of changes in respiratory function. |

| [25] | McCarter et al. (2008) | 634 adult postoperative patients receiving Patient Controlled-Analgesia (PCA), monitored with capnography by nurses | Postoperative period (Phase I and Phase II) |

Facilitators: - Increased nurse awareness of respiratory changes; - Increased effectiveness of nursing interventions to minimize respiratory discomfort related to PCA; - Increased nurse confidence due to effective monitoring; - Quick response from the team to prevent serious consequences; - Increased perceived patient safety during this period. |

| [26] | Lakdawala et al. (2017) | 161 adult neuro-surgical patients screened for OSA using STOP-Bang, monitored with capnography by nurses | Preoperative unit, PACU, and neuro-surgery unit |

Barriers: - Nurses observed greater patient resistance to adherence to capnography devices; - Nurses reported the need for increased knowledge on the use of capnography in patients with OSA. Facilitators: - Capnography proved to identify early signs of respiratory depression, allowing for quick intervention; - Need to educate patients on the importance of using the device to ensure safety and promote adherence. |

| [27] | Jungquist et al. (2019) | 60 adult patients in PACU after spine, neck, hip, or knee surgery, monitored by nurses for opioid-induced respiratory depression | PACU |

Barriers: - Nurses' perception of patient non-adherence, related to discomfort and mask removal for nursing care. - Need for nurse training due to limited knowledge of the technique and indications for capnography. |

| [28] | Scully (2019) | 314 adult patients diagnosed with OSA, monitored by multidisciplinary team | PACU |

Facilitators: - Training for professionals (introduction to capnography and monitoring); - Increased confidence in using capnography helped stimulate critical thinking (by applying it to other patients beyond the OSA population); - Improvement in care quality and patient safety drive change; - Regular communication of results (via audit) motivated the team and promoted the implementation process; - Promoting sustainability by involving training and raising nurse awareness to provide better care, integrating capnography monitoring into clinical practice; - Allowed the nurse to intervene early to prevent respiratory complications. |

| [29] | Atherton et al. (2022) | 176 nurses | PACU |

Facilitators: - The educational program increased nurses’ confidence and competence in using End-tidal Carbon Dioxide Concentration (etCO2) and transcutaneous carbon dioxide monitoring; - Prior knowledge and training with etCO2 monitoring. |

| [19] | Potvin et al. (2022) | 52 adult patients with endotracheal tube or laryngeal mask, monitored by nurses | PACU |

Facilitators: - Nurse training facilitated the accurate interpretation and the layout of monitoring systems; - Training should be accompanied by a standardized protocol; - Standard monitoring, together with capnography, can improve patient safety by allowing early detection of respiratory complications. |

| Hutchison et al. (2008) [24] |

McCarter et al. (2008) [25] |

Lakdawala et al. (2017) [26] |

Jungquist et al. (2019) [27] |

Scully et al. (2019) [28] |

Atherton et al. (2022) [29] |

Potvin et al. (2022) [19] |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BARRIERS | High workload | X | ||||||

| Perceived lack of patient adherence | X | X | X | |||||

| Lack of knowledge | X | X | ||||||

| FACILITATORS | Alarm sound | X | ||||||

| Patient education | X | X | ||||||

| Anticipating patient clinical instability | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Increased nurse confidence | X | X | ||||||

| Perception of enhanced safety | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Targeted nurse training | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Continuous improvement in care delivery | X | |||||||

| Effective communication and feedback | X | |||||||

| Promotion of sustainable practices | X | |||||||

| Prior knowledge and exposure | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).