Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biology and Genetics of Lipoprotein(a)

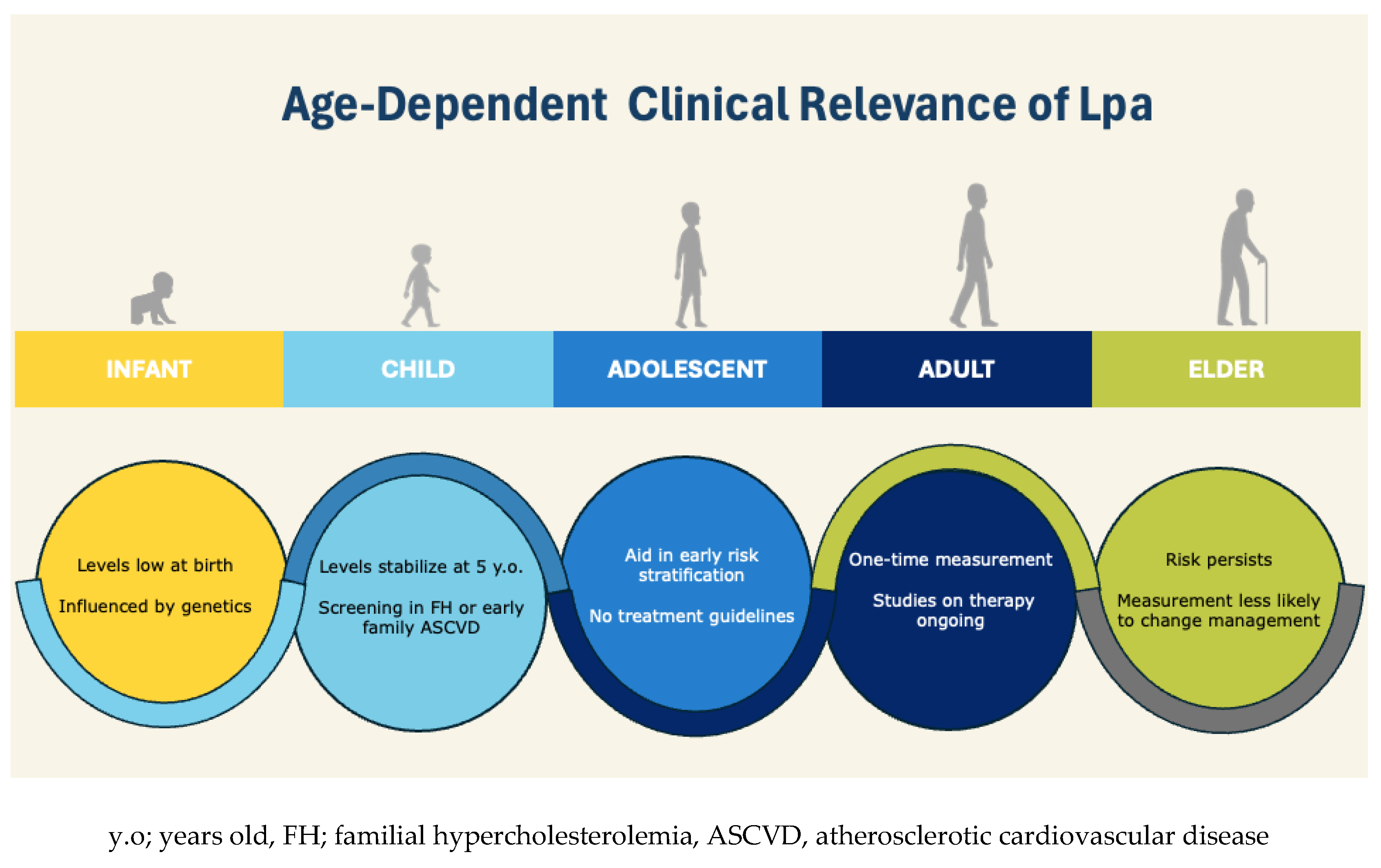

3. Lp(a) Expression and Measurement over the Lifespan

Children and Adolescents

Adults and Elders

Population Variations

4. Risk-Stratification According to Age

Children and Adolescents

Adults

Elders

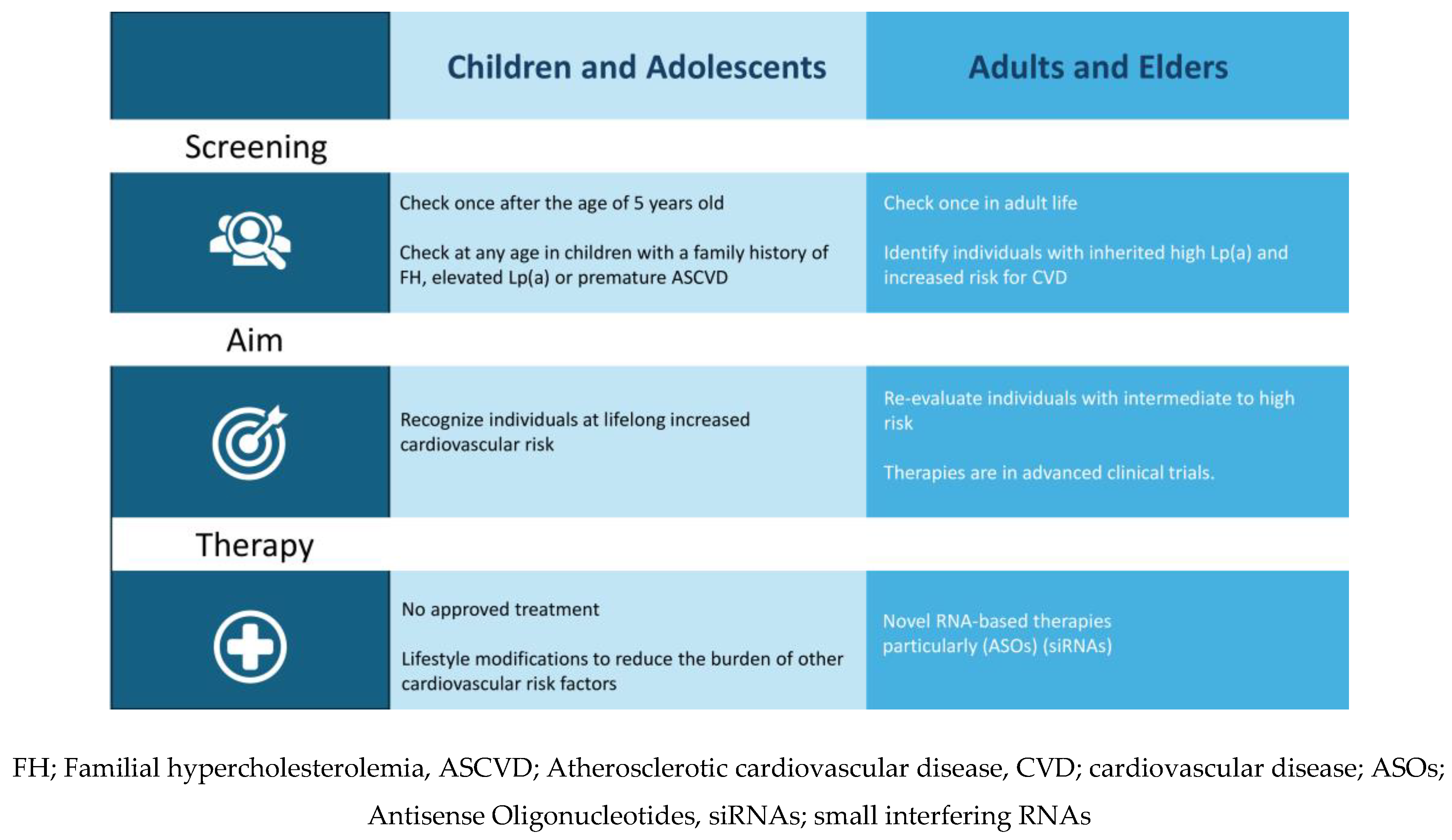

5. Screening

Children and Adolescents

Adults and Elders

6. Therapy

Lifestyle Modifications and Current Pharmacological Options

Novel Treatments

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs)

Small Interfering RNAs (siRNAs)

Oral Therapy – Muvalaplin

Future Directions – Gene Editing

7. Gaps in Evidence – Future Directions

Children and Adolescents

Elders

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| Lp(a) | Lipoprotein(a) |

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease |

| FH | Familial Hypercholesterolemia |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| ApoB | Apolipoprotein B100 |

| ApoA | Apolipoprotein A |

| KIV | Kringle IV |

| CNVs | Copy Number Variations |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| SNPs | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| MI | Myocardial Infraction |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| FMD | Flow-Mediated Dilation |

| IMT | Intima-Media Thickness |

| PWV | Pulse Wave Velocity |

| SEVR | Subendocardial Viability Ratio |

| ART | Assisted Reproductive Technologies |

| AVS | Aortic Valve Stenosis |

| PCSK9is | Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 Inhibitors |

| ASOs | Antisense Oligonucleotides |

| siRNAs | Small Interfering RNAs |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

References

- Kostner KM, Kostner GM. Lipoprotein (a): a historical appraisal. J Lipid Res 2016;58:1. [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur Heart J 2022;43:3925–46. [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG. Consensus and guidelines on lipoprotein(a) - Seeing the forest through the trees. Curr Opin Lipidol 2022;33:342. [CrossRef]

- Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic heart disease and familial hypercholesterolaemia. British Journal of Cardiology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Introduction to Lipids and Lipoproteins. Endotext 2024.

- Wu Z, Sheng H, Chen Y, et al. Copy number variation of the Lipoprotein(a) (LPA) gene is associated with coronary artery disease in a southern Han Chinese population. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014;7:3669.

- Kronenberg, F. Lipoprotein(a): from Causality to Treatment. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2024;26:75–82. [CrossRef]

- Luo D, Björnson E, Wang X, et al. Distinct lipoprotein contributions to valvular heart disease: Insights from genetic analysis. Int J Cardiol 2025;431. [CrossRef]

- Giussani M, Orlando A, Tassistro E, et al. Is lipoprotein(a) measurement important for cardiovascular risk stratification in children and adolescents? Ital J Pediatr 2024;50. [CrossRef]

- Pac-Kozuchowska E, Krawiec P, Grywalska E. Selected risk factors for atherosclerosis in children and their parents with positive family history of premature cardiovascular diseases: a prospective study. BMC Pediatr 2018;18. [CrossRef]

- Simony SB, Mortensen MB, Langsted A, et al. Sex differences of lipoprotein(a) levels and associated risk of morbidity and mortality by age: The Copenhagen General Population Study. Atherosclerosis 2022;355:76–82. [CrossRef]

- Berenson, GS. Bogalusa Heart Study: A long-term community study of a rural biracial (Black/White) population. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 2001;322:267–74. [CrossRef]

- Qayum O, Alshami N, Ibezim CF, et al. Lipoprotein (a): Examination of Cardiovascular Risk in a Pediatric Referral Population. Pediatr Cardiol 2018;39:1540–6. [CrossRef]

- Giammanco A, Noto D, Nardi E, et al. Do genetically determined very high and very low LDL levels contribute to Lp(a) plasma concentration? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2025;35. [CrossRef]

- de Boer LM, Wiegman A, van Gemert RLA, et al. The association between lipoprotein(a) levels and ischemic stroke in children: A case-control study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2024;71. [CrossRef]

- Nave AH, Lange KS, Leonards CO, et al. Lipoprotein (a) as a risk factor for ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2015;242:496–503. [CrossRef]

- Zawacki AW, Dodge A, Woo KM, et al. In pediatric familial hypercholesterolemia, lipoprotein(a) is more predictive than LDL-C for early onset of cardiovascular disease in family members. J Clin Lipidol 2018;12:1445–51. [CrossRef]

- Pederiva C, Capra ME, Biasucci G, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and family history for cardiovascular disease in paediatric patients: A new frontier in cardiovascular risk stratification. Data from the LIPIGEN paediatric group. Atherosclerosis 2022;349:233–9. [CrossRef]

- Raitakari O, Kartiosuo N, Pahkala K, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in Youth and Prediction of Major Cardiovascular Outcomes in Adulthood. Circulation 2023;147:23–31. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen KE, Celermajer DS, Georgakopoulos D, et al. Impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation is an early event in children with familial hypercholesterolemia and is related to the lipoprotein(a) level. J Clin Invest 1994;93:50–5. [CrossRef]

- Lapinleimu J, Raitakari OT, Lapinleimu H, et al. High Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations Are Associated with Impaired Endothelial Function in Children. J Pediatr 2015;166:947-952.e2. [CrossRef]

- de Boer LM, Wiegman A, Kroon J, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and carotid intima-media thickness in children with familial hypercholesterolaemia in the Netherlands: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2023;11:667–74. [CrossRef]

- Helk O, Böck A, Stefanutti C, et al. Lp(a) does not affect intima media thickness in hypercholesterolemic children -a retrospective cross sectional study. Atherosclerosis Plus 2022;51:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki M, Magnussen CG, Juonala M, et al. Conventional and Mendelian randomization analyses suggest no association between lipoprotein(a) and early atherosclerosis: the Young Finns Study. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:470–8. [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch SE, Boer LM de, Revers A, et al. Association Between Lipoprotein(a) and Arterial Stiffness in Young Adults with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Med 2025;14:1611. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou-Legbelou K, Triantafyllou A, Vampertzi O, et al. Similar Myocardial Perfusion and Vascular Stiffness in Children and Adolescents with High Lipoprotein (a) Levels, in Comparison with Healthy Controls. Pulse (Basel) 2021;9:64–71. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Moran M, Gamboa-Gómez CI, Preza-Rodríguez L, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and Hyperinsulinemia in Healthy Normal-weight, Prepubertal Mexican Children. Endocr Res 2021;46:87–91. [CrossRef]

- Bacopoulou F, Apostolaki D, Mantzou A, et al. Serum Spexin is Correlated with Lipoprotein(a) and Androgens in Female Adolescents. J Clin Med 2019;8. [CrossRef]

- Oberhoffer FS, Langer M, Li P, et al. Vascular function in a cohort of children, adolescents and young adults conceived through assisted reproductive technologies—results from the Munich heARTerY-study. Transl Pediatr 2023;12:1619–33. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Moran M, Guerrero-Romero F. Low birthweight and elevated levels of lipoprotein(a) in prepubertal children. J Paediatr Child Health 2014;50:610–4. [CrossRef]

- Tipping RW, Ford CE, Simpson LM, et al. Lipoprotein(a) Concentration and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease, Stroke, and Nonvascular Mortality. JAMA 2009;302:412–23. [CrossRef]

- Mitsis A, Myrianthefs M, Sokratous S, et al. Emerging Therapeutic Targets for Acute Coronary Syndromes: Novel Advancements and Future Directions. Biomedicines 2024, Vol 12, Page 1670 2024;12:1670. [CrossRef]

- Cesaro A, Acerbo V, Scialla F, et al. Role of LipoprotEin(a) in CardiovascuLar diseases and premature acute coronary syndromes (RELACS study): Impact of Lipoprotein(a) levels on the premature coronary event and the severity of coronary artery disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2025;35. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Tang J, Shi Q, et al. Persistent lipoprotein(a) exposure and its association with clinical outcomes after acute myocardial infarction: a longitudinal cohort study. Ann Med 2025;57. [CrossRef]

- Patel AP, Wang M, Pirruccello JP, et al. Lp(a) (Lipoprotein[a]) Concentrations and Incident Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease New Insights from a Large National Biobank. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2021;41:465–74. [CrossRef]

- O’Toole T, Shah NP, Giamberardino SN, et al. Association Between Lipoprotein(a) and Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease and High-Risk Plaque: Insights From the PROMISE Trial. Am J Cardiol 2024;231. [CrossRef]

- Jackson CL, Garg PK, Guan W, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and coronary artery calcium in comparison with other lipid biomarkers: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Clin Lipidol 2023;17:538–48. [CrossRef]

- Kouvari M, Panagiotakos DB, Yannakoulia M, et al. Transition from metabolically benign to metabolically unhealthy obesity and 10-year cardiovascular disease incidence: The ATTICA cohort study. Metabolism 2019;93:18–24. [CrossRef]

- Man S, Zu Y, Yang X, et al. Prevalence of Elevated Lipoprotein(a) and its Association With Subclinical Atherosclerosis in 2.9 Million Chinese Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2025;85. [CrossRef]

- Pantelidis P, Oikonomou E, Lampsas S, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and calcific aortic valve disease initiation and progression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Res 2023;119:1641–55. [CrossRef]

- Wang HP, Zhang N, Liu YJ, et al. Lipoprotein(a), family history of cardiovascular disease, and incidence of heart failure. J Lipid Res 2023;64. [CrossRef]

- Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated lipoprotein(a) levels, LPA risk genotypes, and increased risk of heart failure in the general population. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:78–87. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Shemirani P, Chong M, Narula S, et al. Elevated Lipoprotein(a) and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: An Observational and Mendelian Randomization Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:1579–90. [CrossRef]

- Gaw A, Murray HM, Brown EA. Plasma lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] concentrations and cardiovascular events in the elderly: evidence from the prospective study of pravastatin in the elderly at risk (PROSPER). Atherosclerosis 2005;180:381–8. [CrossRef]

- Ariyo AA, Thach C, Tracy R. Lp(a) Lipoprotein, Vascular Disease, and Mortality in the Elderly. New England Journal of Medicine 2003;349:2108–15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Liu HH, Jin JL, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular death in oldest-old (≥80 years) patients with acute myocardial infarction: A prospective cohort study. Atherosclerosis 2020;312:54–9. [CrossRef]

- Bartoli-Leonard F, Turner ME, Zimmer J, et al. Elevated lipoprotein(a) as a predictor for coronary events in older men. J Lipid Res 2022;63:100242. [CrossRef]

- Simons LA, Simons J, Friedlander Y, et al. LDL-cholesterol Predicts a First CHD Event in Senior Citizens, Especially So in Those With Elevated Lipoprotein(a): Dubbo Study of the Elderly. Heart Lung Circ 2018;27:386–9. [CrossRef]

- Yang N, Zhang G, Li X, et al. Correlation analysis between serum lipoprotein (a) and the incidence of aortic valve sclerosis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:19318.

- Milionis HJ, Filippatos TD, Loukas T, et al. Serum lipoprotein(a) levels and apolipoprotein(a) isoform size and risk for first-ever acute ischaemic nonembolic stroke in elderly individuals. Atherosclerosis 2006;187:170–6. [CrossRef]

- Khoury M, Clarke SL. The Value of Measuring Lipoprotein(a) in Children. Circulation 2023;147:32–4. [CrossRef]

- collaboration S working group and EC risk, Hageman S, Pennells L, et al. SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: new models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Eur Heart J 2021;42:2439–54. [CrossRef]

- Arnett DK, Roger Blumenthal C-CS, Michelle Albert C-CA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:1376–414. [CrossRef]

- de Boer LM, Wiegman A, Swerdlow DI, et al. Pharmacotherapy for children with elevated levels of lipoprotein(a): future directions. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2022;23:1601–15. [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas S, Gordts PLSM, Nora C, et al. Statin therapy increases lipoprotein(a) levels. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2275–84. [CrossRef]

- Rivera FB, Cha SW, Linnaeus Louisse C, et al. Impact of Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 Inhibitors on Lipoprotein(a): A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression of Randomized Controlled Trials. JACC: Advances 2025;4. [CrossRef]

- Sahebkar A, Reiner Ž, Simental-Mendía LE, et al. Effect of extended-release niacin on plasma lipoprotein(a) levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Metabolism 2016;65:1664–78. [CrossRef]

- Nasoufidou A, Stachteas P, Karakasis P, et al. Treatment options for heart failure in individuals with overweight or obesity: a review. Future Cardiol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bytyçi I, Bytyqi S, Lewek J, et al. Management of children with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia worldwide: a meta-analysis. European Heart Journal Open 2025;5. [CrossRef]

- Reijman MD, Kusters DM, Groothoff JW, et al. Clinical practice recommendations on lipoprotein apheresis for children with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: An expert consensus statement from ERKNet and ESPN. Atherosclerosis 2024;392. [CrossRef]

- Gianos E, Duell PB, Toth PP, et al. Lipoprotein Apheresis: Utility, Outcomes, and Implementation in Clinical Practice: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2024;44. [CrossRef]

- Boffa MB, Koschinsky ML. Therapeutic Lowering of Lipoprotein(a). Circ Genom Precis Med 2018;11:e002052. [CrossRef]

- Burgess S, Ference BA, Staley JR, et al. Association of LPA Variants With Risk of Coronary Disease and the Implications for Lipoprotein(a)-Lowering Therapies: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:619–27. [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas S, Viney NJ, Hughes SG, et al. Antisense therapy targeting apolipoprotein(a): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 study. The Lancet 2015;386:1472–83. [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas S, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Gouni-Berthold I, et al. Lipoprotein(a) Reduction in Persons with Cardiovascular Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;382:244–55. [CrossRef]

- Cho L, Nicholls SJ, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Design and Rationale of Lp(a)HORIZON Trial: Assessing the Effect of Lipoprotein(a) Lowering With Pelacarsen on Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients With CVD and Elevated Lp(a). Am Heart J 2025;287:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Kosmas CE, Bousvarou MD, Tsamoulis D, et al. Novel RNA-Based Therapies in the Management of Dyslipidemias. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26. [CrossRef]

- Kaur G, Rosenson RS, Gencer B, et al. Olpasiran lowering of lipoprotein(a) according to baseline levels: insights from the OCEAN(a)-DOSE study. Eur Heart J 2025;46:1162–4. [CrossRef]

- Nissen SE, Ni W, Shen X, et al. Lepodisiran - A Long-Duration Small Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a). N Engl J Med 2025;392. [CrossRef]

- Nissen SE, Wang Q, Nicholls SJ, et al. Zerlasiran—A Small-Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a): A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024;332:1992–2002. [CrossRef]

- Study Details | A Study to Investigate the Effect of Lepodisiran on the Reduction of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Adults With Elevated Lipoprotein(a) - ACCLAIM-Lp(a) | ClinicalTrials.gov n.d. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06292013 (accessed June 20, 2025).

- Nicholls SJ, Nissen SE, Fleming C, et al. Muvalaplin, an Oral Small Molecule Inhibitor of Lipoprotein(a) Formation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023;330:1042–53. [CrossRef]

- Doerfler AM, Park SH, Assini JM, et al. LPA disruption with AAV-CRISPR potently lowers plasma apo(a) in transgenic mouse model: A proof-of-concept study. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2022;27:337–51. [CrossRef]

- Clinical trials in children, n.d. https://www.who.int/tools/clinical-trials-registry-platform/clinical-trials-in-children (accessed July 1, 2025).

- Ethical considerations for clinical trials on medicinal products conducted with minors Recommendations of the expert group on clinical trials for the implementation of Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use 2017.

- Gianos E, Duell PB, Toth PP, et al. Lipoprotein Apheresis: Utility, Outcomes, and Implementation in Clinical Practice: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sbrana F, Dal Pino B, Corciulo C, et al. Pediatrics cascade screening in inherited dyslipidemias: a lipoprotein apheresis center experience. Endocrine 2025;88. [CrossRef]

| Age | Stroke | MI | CAD | Atherosclerosis |

| Child | Bogalusa [12] | Bogalusa [12] Zawacki et al [17] LIPIGEN [18] |

de Boer LM et al [22] Young Finns [24] |

|

| Adolescent | Zawacki et al [17] | Young Finns [19] | ||

| Adult | Tipping [31] | Tipping [31] Wang [34] [35] |

PROMISE [36], ATTICA [38] | Jackson [37] |

| Elder | PROSPER [44] Ariyo [45] Milionis [50] |

Zhang [46] Bartoli [47] |

Simons [48] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).