Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Historical Context of Armed Conflict and High Levels of Violence in Latin America and the Caribbean (LA&C) (Last 25 Years)

2.1. Conflicts in North America and the Caribbean

2.1.1. Conflicts in Central America

2.1.2. Conflicts in South America

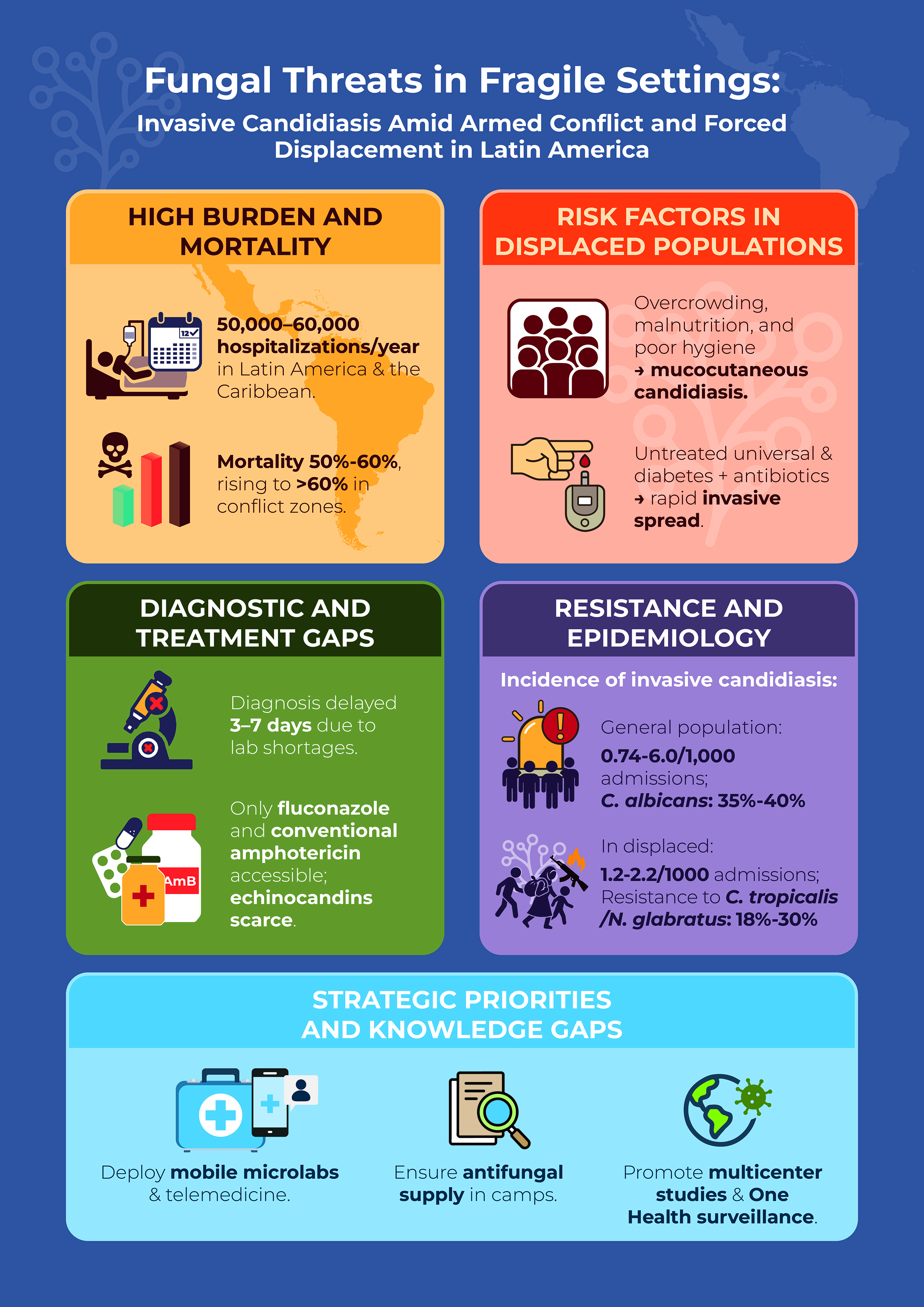

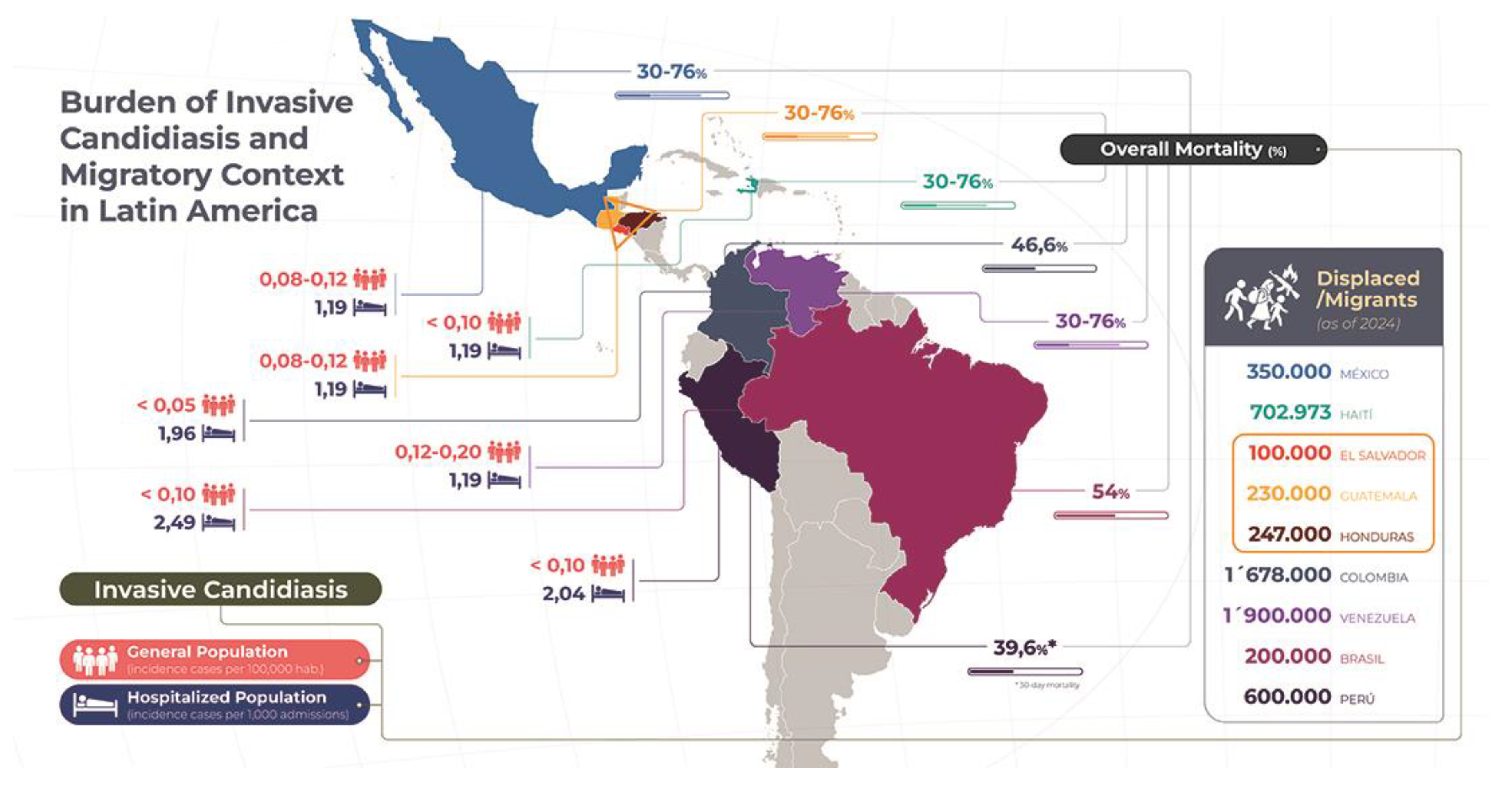

3. Epidemiology and Burden of IC Disease in LA&C

- Delay in diagnosis: the speed with which candidemia is detected varies depending on the fungal species. While C. albicans can be detected in an average of 35 hours, N. glabratus requires up to 80 hours, which significantly delays the start of effective antifungal treatment [74].

- Age and clinical status at admission: a high APACHE II score and a diagnosis of septic shock are negative prognostic factors. On average, patients who die from candidemia are around 60 years old [79].

Epidemiology, Disease Burden in the Context of Armed Conflict and High Violence

4. Factores Risk Factors for IC in the General Population and in Contexts of Forced Displacement in LA&C

4.1. Health Conditions and Risk of Fungal Infection in Migrant and Displaced Populations

4.1.1. Socio-Environmental Conditions and Social Determinants

- Overcrowding and informal settlements: in contexts such as Venezuelan refugee camps in Colombia and Haitian migrant settlements in the Dominican Republic, it is common for families to live in extremely small spaces (less than 5 m² per person). These overcrowded conditions not only make privacy and hygiene difficult but also increase body moisture and skin maceration, promoting the development of fungal infections. In a recent survey, 28% of adult women in these environments reported intertriginous or vulvovaginal candidiasis [156]. An institutional report (2019–2020) on Mexico's southern border with Guatemala revealed that Central American migrants housed in shelters without adequate ventilation showed a high prevalence of skin infections. Microbiological field studies found that 33% of cases with interdigital rashes tested positive for Candida, mainly C. parapsilosis, highlighting how the tropical climate, combined with poor hygiene, increases susceptibility to these infections [157].

- Limited access to drinking water and sanitation: in the Northern Triangle of Central America (Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala), recent studies have shown that more than 40% of informal settlements do not have a continuous supply of chlorinated water. This limitation prevents adequate hand and surface hygiene, creating conditions conducive to the proliferation of yeasts in the environment. Such microenvironments become potential reservoirs for infections such as cutaneous and vulvovaginal candidiasis [158]. In Bolivia, data collected between 2018 and 2019 in rural areas inhabited by returning migrants showed that only 35% of homes had adequate latrines. This deficiency in basic sanitation increases the environmental microbial load and favors fungal colonization of the skin and moist areas of the body, especially in crowded conditions and hot climates [159].

- Malnutrition and immune deficiency: an internal epidemiological surveillance report conducted between 2018 and 2019 among the displaced population in the department of Arauca, Colombia, revealed that 42% of children and 28% of pregnant women suffered from acute or chronic malnutrition. In this context, 30% of children with oral candidiasis showed signs of malnutrition, and within this group, 18% developed candidemia within less than ten days [160,161]. The lack of essential micronutrients—such as vitamins A and D and zinc—impairs both cellular and humoral immunity, promoting the transition of Candida from superficial colonization to systemic infection. This risk is exacerbated in displaced adults with irregular access to basic nutritional supplements [160].

4.1.2. Prevalent Comorbidities in Migrants and Displaced Persons

- HIV/AIDS: according to an institutional report for the period 2018–2019, the prevalence of HIV among Venezuelan migrants settled in Colombia was 3.2%, of whom 45% were not receiving antiretroviral treatment and had CD4 counts below 200 cells/µL. In this cohort, 38% developed oral candidiasis, and 12% developed esophageal candidiasis during the first year of follow-up [162]. A retrospective analysis conducted after the 2010 earthquake in Haitian displacement camps revealed that many people were living with HIV patients in advanced stages of the disease and without access to antiretroviral therapy. In this group, 55% were diagnosed with recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis, and 12% had candidemia, which was associated with a 65% mortality rate due to the lack of timely diagnosis and effective antifungal drugs [163].

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus: in agricultural export plantations in Central America, studies conducted among migrant workers showed a prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes of 16%. Of this group, 30% had candidal vulvovaginitis and 8% developed complicated forms of cutaneous candidiasis, including infected ulcers [119,120]. Similarly, an internal epidemiological surveillance report on displaced indigenous communities in Peru documented that 14% of older adults had uncontrolled diabetes (fasting glucose greater than 126 mg/dL). In these patients, interdigital candidiasis occurred in 27% of cases, and an RR of 2.8 (95% CI: 1.6–4.9) was estimated for the development of disseminated candidiasis after hospitalization [164].

- Tuberculosis and co-infections: in camps for displaced persons located in the border areas between Venezuela and Colombia, a prevalence of tuberculosis (TB) of 350 cases per 100,000 inhabitants has been documented, with a high frequency of HIV/TB co-infection. This combination increases the risk of IC. A retrospective study conducted in Bogotá revealed that 22% of patients with TB/HIV coinfection developed candidemia, with an associated mortality rate of 58% [165]. On the other hand, a descriptive study in Guatemala observed that, in co-infected individuals, the presence of extrapulmonary TB—particularly in its peritoneal or gastrointestinal forms—caused damage to the digestive mucosa, facilitating the translocation of Candida spp. into the body. As a result, 14% of these patients developed intra-abdominal candidiasis [166].

4.1.3. Exposure to Iatrogenic Factors

- Use of antibiotics in mobile clinics and shelters: between 2019 and 2020, in mobile clinics providing medical care to Nicaraguan migrants in Mexican territory, it was observed that 78% of patients with fever were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as ceftriaxone or carbapenems, without prior blood cultures. This practice was associated with the onset of mucocutaneous candidiasis in 26% of cases and candidemia in approximately 5%, although significant underreporting is presumed due to the lack of diagnostic laboratories in these settings [167]. The widespread empirical use of antibiotics without proper assessment of the risk of fungal infection has contributed to the disruption of normal microbiota, facilitating the overgrowth of Candida spp.

- Use of invasive devices in border hospitals: an internal surveillance report from 2020, based on data from migrant reception units in Tapachula (Mexico–Guatemala region), found that 42% of patients hospitalized for sepsis required CVC insertion. Among these patients, 12% developed candidemia, which corresponds to a significantly elevated risk (OR 3.5; 95% CI: 2.0–6.1). Furthermore, due to a lack of specialized personnel, protocols for early catheter removal are not properly implemented, prolonging exposure to fungal biofilm and increasing the likelihood of invasive infections [168].

4.1.4. Demographic and Vulnerability Factors

- Age and gender: an epidemiological surveillance study in Colombia (2018–2019), focusing on displaced children, revealed that 18% of newborns from temporary shelters developed oral candidiasis in their first week of life. This finding was related to low birth weight (less than 2,500 g) and maternal malnutrition, conditions that are common in contexts of forced displacement [160]. On the other hand, a study on reproductive health in migrant women (2019) found that 34% of women living in border settlements experienced episodes of vulvovaginal candidiasis in the last year, mainly linked to malnutrition, pregnancy, and limited access to adequate gynecological services [169].

- Ethnicity and inequalities: in displaced Guaraní indigenous communities in Paraguay, the rate of cutaneous candidiasis was almost three times higher than that observed in nearby urban populations. This difference has been attributed to difficulties in accessing adequate health services and language barriers that limit timely care [170]. Similarly, an internal report on Haitian migrants in the Dominican Republic reported that 46% of adults with HIV developed oral candidiasis, compared to 28% of the non-migrant population. Language barriers and experiences of discrimination contribute significantly to delays in diagnosis and treatment [171].

4.1.5. Environmental and Occupational Conditions

- Agricultural work and environmental exposure: among Central American migrants employed on sugar cane plantations in Guatemala, a 15% prevalence of skin colonization by C. parapsilosis has been identified, which is associated with repeated contact with humid environments and contaminated surfaces, such as wet soil and stagnant water [172]. On the other hand, an epidemiological surveillance report conducted in fruit-growing areas in Peru found that 22% of migrant workers of Peruvian and Bolivian origin developed interdigital candidiasis. This condition could be related to repeated exposure to insecticides, which alter the normal microbial flora of the skin [173].

- Climate and microenvironments: according to an epidemiological surveillance report, climatic conditions in coastal areas of Central America—characterized by humidity levels above 80% and constant temperatures around 28°C—are favorable for the growth of yeast on the skin and mucous membranes. In Honduras, migrants traveling along routes near the coast were found to have intertriginous candidiasis in 31% of cases, a figure considerably higher than the 12% reported among those traveling along mountainous routes [174].

5. Diagnosis of IC in LA&C: Barriers and Diagnostic Methods in Resource-Limited Settings

5.1. Barriers and Limitations in the Diagnosis of Candidiasis

5.1.1. Infrastructure and Logistics

- Lack of local laboratories: mobile health centers and small shelters are not equipped with adequate biosafety facilities or protocols for mushroom cultivation. As a result, samples must be sent to reference laboratories, which are often located far away. This involves transportation without a cold chain, which increases the risk of contamination or decreases the viability of the fungi, reducing crop yields to less than 50% [9,12].

5.1.2. Human Resources and Training

- High turnover of volunteer staff: in NGOs operating in camps, constant staff turnover prevents continuity in the use of protocols and hinders the transfer of specialized knowledge. Although there are no exact figures, this recurring problem has been documented in border environments [111,190,191,192].

5.1.3. Costs and Availability of Reagents

- Scarce and expensive basic reagents: in many countries in the Andean region and the Caribbean, essential reagents such as KOH 10% solutions and Gram stains must be imported, which increases the cost of each test by approximately USD 5–10. This is a difficult expense for mobile clinics with limited resources to bear [111,176,180,189,193].

- Limited access to state-of-the-art testing: serological tests such as BDG or molecular methods such as qPCR are not covered by public health systems and are only offered in reference laboratories, usually located in capital cities. This situation forces patients to travel long distances to access these diagnostics [9,117,176,194].

5.1.4. Social and Cultural Limitations

- Distrust of the healthcare system: many displaced persons have been victims of violence or discrimination, which generates mistrust of medical services and reduces their willingness to participate in procedures such as blood tests. Although there are no specific data on candidiasis, reproductive health studies show that more than 40% of displaced populations avoid going to official centers for this reason [12,41,125,142,192].

- Language and communication barriers: in Haitian refugee shelters in the Dominican Republic and also in Venezuelan indigenous communities, a lack of fluency in Spanish hinders communication with healthcare personnel. Qualitative studies indicate that up to 30% of consultations are postponed or interrupted due to language problems or a lack of interpreters [11,131,192,195,196].

5.2. Recommendations for Strengthening Diagnosis in Areas of Forced Displacement

5.2.1. Optimization of Low-Cost Methods

- Technical training in KOH: it is recommended to train local staff through weekly workshops focused on the processing and interpretation of exudates using 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH 10%). The implementation of this strategy in areas with limited resources has been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy [106,180,189,195,197].

- Rotary direct microscopy with calcofluor: several studies have shown that calcofluor is consistently more sensitive than KOH and sometimes comparable to more sophisticated diagnostic methods. Its usefulness as a rapid diagnostic technique makes it especially valuable in resource-limited environments. In this context, the possibility of sharing UV equipment between nearby camps is suggested to facilitate the assessment of mucocutaneous lesions. This strategy could be applied in countries such as Haiti to reduce the false negative rate [180,189,198,199].

5.2.2. Implementation of Simplified Algorithms

- Adapted use of the “modified Candida Score” in primary care: in community settings where state-of-the-art testing is not available, a simplified version of the “Candida Score” is proposed for initiating empirical treatment. In patients with fever without apparent source and at least three of the following criteria—recent antibiotic use, presence of CVC, and malnutrition—it is recommended to initiate FCZ if the KOH test is positive. If BDG is available, consider echinocandins when this marker is positive. Studies in ICUs in Latin America show that a score equal to or greater than 3 predicts candidemia with a sensitivity of 70% [117,188].

- Creation of multilingual visual guides: designing and distributing illustrative materials on clinical signs of candidiasis, translated into Spanish, Haitian Creole, and indigenous languages, can be key to improving recognition of the infection. Experiences in community health programs have shown that incorporating these guides improves early detection by 18% [7,12,189,200].

5.2.3. Surveillance and Reference Networks

- Development of collaborative networks for sample processing: it is proposed to implement a referral system between camps and laboratories located in nearby urban areas, ensuring the transport of samples under appropriate cold chain conditions. This measure, accompanied by regular exchanges of volunteer microbiologists, has proven effective: in Latin America, agreements between mobile units and universities reduced the analysis time for mycological samples from seven to three days [6,12,111,175,176,187].

- Strengthening tele-mycology networks: the use of technology to share diagnostic images (cultures, smears, lesions) in real-time via mobile networks or satellite connections can significantly improve diagnostic accuracy. Creating virtual links with regional mycology experts would enable constant supervision and technical support, with at least one specialist recommended for every 5,000 displaced persons [178,197,201,202,203].

5.2.4. Funding and Strategic Alliances

- Ensure donations of basic supplies: we propose coordinating with organizations such as GAFFI and PAHO to deliver essential supplies (KOH, dyes, culture media) to mobile clinics in border areas and hard-to-reach camps. Since 2019, these initiatives have made it possible to supply resources to more than 20 mobile units in Colombia and Peru, strengthening their diagnostic capacity [6,7,106,176,189,200,204]

- Formalize agreements with regional universities: emphasis is placed on the need to integrate essential diagnostics and strengthen national and hospital diagnostic networks. It is also proposed to establish biannual agreements with local universities for the provision of diagnostic supplies to reduce and lower transportation expenses and expand diagnostic coverage in remote areas [7,12,106,175,176,187,200].

6. Antifungal Treatment of IC in LA&C: Availability of Antifungals and Antifungal Resistance

- Restricted availability of essential antifungals: in most LA&C countries, access to antifungals is limited mainly to generic FCZ, due to its low cost and early inclusion in national essential medicines lists [10,193,206]. Although this drug is available, it is not the ideal option for candidemia in critically ill patients, as up to 50% of non-albicans isolates—such as N. glabratus, P. kudriavzevii, and C. auris—have reduced sensitivity or intrinsic resistance to FCZ.

- Suboptimal administration of D-AmB: in the absence of echinocandins, D-AmB is frequently used as an alternative. However, to ensure its safe use, constant monitoring of renal function and electrolyte balance is required, as well as continuous administration of intravenous fluids and potassium salts [207]. In hospitals with limited resources, such conditions are often inadequate. This has led many professionals to reduce doses as a precaution, especially when there is no access to ICUs or adequate laboratories. Additionally, D-AmB depends on a cold chain, which is challenging in hot environments with unstable power supplies.

- Increase in antifungal-resistant strains: during the C. auris outbreak in Venezuela, all isolates showed resistance to FCZ and VCZ, and 50% had high minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) against AmB [208]. Although echinocandins are considered the almost exclusive therapeutic resource in these cases, strains with reduced sensitivity to these drugs are beginning to be detected [65,217]. At the same time, N. glabratus shows increased resistance to azoles, and C. parapsilosis shows mutations associated with prolonged treatment with echinocandins [215,220,221,222]. In Brazil, clusters of FCZ-resistant C. parapsilosis have been documented [8,221,222,223], and in areas of armed conflict, the absence of surveillance and infection control facilitates their unnoticed spread.

- Incomplete treatments: the minimum duration of treatment for candidemia should be 14 days from the last negative blood culture, extending in the presence of metastatic foci [112,117,185]. In displacement settings, it is common for patients to discontinue treatment after one week due to continuous displacement or depletion of medications in centers, which increases the risk of relapse and promotes the development of resistance.

- Inequality in costs and access: while FCZ is relatively affordable, echinocandins and L-AmB are too expensive for most centers and are only available in private clinics. In countries such as Haiti and Venezuela, public systems lack these drugs, and NGOs rarely include them in their emergency supplies due to budget constraints [121,193,194,206]. This means that, in many refugee camps, optimal treatment for candidemia remains inaccessible.

- Lack of complementary critical support: effective management of IC goes beyond the provision of antifungal agents. It requires intensive care, surgical interventions to control foci (such as valve replacement in endocarditis or abscess drainage), as well as life support—dialysis in cases of renal failure or MV [106,176,185]. In conflict-affected areas, these resources are often lacking [194], meaning that even with adequate antifungal treatment, the outcome can be fatal due to the lack of comprehensive clinical support or access to interventions that remove the source of infection.

7. Access to Health Services and Antifungal Treatment in Areas of Conflict and High Violence in LA&C

- Forced internal migration and informal settlements: internally displaced persons and refugees living in temporary camps often have limited or no access to adequate healthcare services. In these contexts, cases of candidemia are rarely diagnosed or treated with antifungal medication, and deaths are often not officially reported [38,142,229].

- 2. Risks for patients and healthcare personnel: in areas of active violence, transfer to a medical center can pose a life-threatening risk (bombing, snipers, checkpoints). In conflicts such as the one in Syria, attacks on hospitals and healthcare personnel have been documented, interrupting essential treatments for severe mycoses [230].

8. Regional Perspective

8.1. Mexico

8.2. Haiti:

8.3. North Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras)

8.4. Colombia

8.5. Venezuela

8.6. Brazil

8.7. Peru

9. Recommendations for Future Research

- Quantify the prevalence of candidiasis (mucocutaneous and invasive) and its distribution by species, including resistance profiles.

- Identify specific risk factors of displacement, such as hygiene conditions, sanitary access barriers, and psychological stress.

- Evaluate interventions such as improved sanitation, educational programs, and the use of broad-spectrum antifungals in vulnerable populations [125].

- 1.

-

Multicenter prevalence studies

- Conduct cross-sectional studies in camps and shelters to quantify the prevalence of oral and vulvovaginal candidiasis, itemized by sociodemographic factors, nutritional status, and HIV co-infection [228].

- 2.

-

Species identification and antifungal profile

- Create mobile laboratories or partnerships with regional laboratories (for example, in hospitals of host cities) to differentiate species and perform MIC sensitivity tests on dilution medium [256].

- Establish a regional registry of isolates from migrants and displaced persons in LA&C, including genetic typing using MLST (multilocus sequence typing) [257].

- 3.

-

Study of risk factors associated with displacement

- 4.

-

Design clinical trials to evaluate preventive and therapeutic interventions

- Conduct a randomized study in patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis to compare short treatment regimens with FCZ versus topical therapy with azoles (miconazole), evaluating adherence and tolerance [260].

- 5.

-

Systematic monitoring in camp health care centers

- 6.

-

Integration of a One Health approach

- Establish partnerships with veterinarians and local bioresource centers to identify environmental reservoirs of Candida in temporary settlement sites [106].

Author Contributions

Funding

Statement of the Institutional Ethics Committee

Informed Consent Statement

Declaration of Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest:

References

- Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F, Alvarado-Matute T, Tiraboschi IN, Cortes J, Zurita J, et al. Epidemiology of Candidemia in Latin America: A Laboratory-Based Survey. [cited 2025 Jun 13]; Available from: www.plosone.org.

- Yapar N. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management Dovepress Epidemiology and risk factors for invasive candidiasis. 2014 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. [CrossRef]

- Falci DR, Pasqualotto AC. Clinical mycology in Latin America and the Caribbean: A snapshot of diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities. Mycoses [Internet]. 2019 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];62(4):368–73. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30614600/.

- Desai AN, Ramatowski JW, Marano N, Madoff LC, Lassmann B. Infectious disease outbreaks among forcibly displaced persons: An analysis of ProMED reports 1996-2016. Confl Health [Internet]. 2020 Jul 22 [cited 2025 Jun 13];14(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32704307/.

- Denning DW. Global incidence and mortality of severe fungal disease. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2024 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];24(7):e428–38. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38224705/.

- GAFFI. The burden of serious fungal infections in Latin America 5 https://life-slides-and-videos.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/LIFE+articles/Burden+of+serious+fungal+infections+in+Latin+America.pdf. 2021.

- GAFFI. Report on activities for 2015. [cited 2025 Jun 14]; 2016. Available from: https://gaffi.org/wp-content/uploads/GAFFI-2015-annual-report.pdf.

- Bays DJ, Jenkins EN, Lyman M, Chiller T, Strong N, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Epidemiology of Invasive Candidiasis. Clin Epidemiol [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13];16:549–66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39219747/.

- Cortés JA, Ruiz JF, Melgarejo-Moreno LN, Lemos E V., Cortés JA, Ruiz JF, et al. Candidemia en Colombia. Biomédica [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 13];40(1):195–207. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-41572020000100195&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, Sprute R, Seidel D, Oliverio M, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. EClinicalMedicine [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38053535/.

- Plataforma R4V. Refugiados y migrantes de Venezuela | R4V https://www.r4v.info/es/refugiadosymigrantes [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.r4v.info/es/refugiadosymigrantes.

- Rodriguez Tudela JL, Cole DC, Ravasi G, Bruisma N, Chiller TC, Ford N, et al. Integration of fungal diseases into health systems in Latin America. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];20(8):890–2. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32619435/.

- IDMC. IDMC | GRID 2022 | 2022 Global Report on Internal Displacement [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2022/.

- ICRC. Latin America: Armed violence, conflict, internal displacement, migration and disappearances were main humanitarian challenges in 2021 | International Committee of the Red Cross [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/latin-america-armed-violence-conflict-internal-displacement-migration-disappearances.

- IDMC. 2024 Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID) | IDMC - Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2024/.

- UNICEF. Number of unaccompanied and separated children migrating in Latin America and the Caribbean hits record high. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/lac/en/press-releases/number-unaccompanied-children-migrating-latin-america-caribbean-hits-record-high.

- Caparini M DI. The Americas — Key general developments in the region. En: SIPRI Yearbook 2022: Arm Conflict and Conflict Management 2021. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute; 2022. 2022;77–81.

- Gousy N, Adithya Sateesh B, Denning DW, Latchman K, Mansoor E, Joseph J, et al. Fungal Infections in the Caribbean: A Review of the Literature to Date. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];9(12):1177. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/9/12/1177/htm.

- Bernal O, Garcia-Betancourt T, León-Giraldo S, Rodríguez LM, González-Uribe C. Impact of the armed conflict in Colombia: consequences in the health system, response and challenges. Confl Health [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];18(1):1–9. Available from: https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13031-023-00561-6.

- Izcara-Palacios SP. Violencia contra inmigrantes en Tamaulipas. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. 2012;93:3–24.

- UNHCR. UNHCR Dataviz Platform - Haiti: A multi-dimensional crisis leading to continued displacement [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://dataviz.unhcr.org/product-gallery/2024/10/haiti-a-multi-dimensional-crisis-leading-to-continued-displacement/.

- Restrepo-Betancur LF, Restrepo-Betancur LF. Migración en Sudamérica en los últimos treinta años. El Ágora USB [Internet]. 2021 Sep 17 [cited 2025 Jun 13];21(1):61–74. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1657-80312021000100061&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- UNHCR. El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras situation | Global Focus https://reporting.unhcr.org/el-salvador-guatemala-and-honduras-situation-global-report-2022 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/el-salvador-guatemala-and-honduras-situation-global-report-2022.

- UNHCR. Situación en Colombia | Enfoque global [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/colombia-situation.

- BID. Migración interna en Venezuela: en busca de oportunidades antes y durante la crisis https://publications.iadb.org/es/migracion-interna-en-venezuela-en-busca-de-oportunidades-antes-y-durante-la-crisis [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://publications.iadb.org/es/migracion-interna-en-venezuela-en-busca-de-oportunidades-antes-y-durante-la-crisis.

- ICRC. Armed violence in Mexico and Central America continues to cause large-scale suffering | International Committee of the Red Cross https://www.icrc.org/en/document/armed-violence-mexico-and-central-america-continues-cause-large-scale-suffering [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/armed-violence-mexico-and-central-america-continues-cause-large-scale-suffering.

- THE GUARDIAN. More than 500 Mexicans flee to Guatemala to escape cartel violence in Chiapas | Mexico | The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jul/30/mexico-chiapas-flee-to-guatemala [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jul/30/mexico-chiapas-flee-to-guatemala.

- THE TIME. The pilgrimage town that went to war when the drug cartels arrived https://www.thetimes.com/world/latin-america/article/a-town-that-went-to-war-local-feud-fuels-mexican-cartels-fight-for-control-fzqjmq302 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.thetimes.com/world/latin-america/article/a-town-that-went-to-war-local-feud-fuels-mexican-cartels-fight-for-control-fzqjmq302.

- WSJ. Haiti’s Beleaguered Government Launches Drones Against Gangs - WSJ https://www.wsj.com/world/americas/haiti-drones-gangs-fight-27e8341f [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.wsj.com/world/americas/haiti-drones-gangs-fight-27e8341f.

- ICRC. Haiti: Renewed clashes fuel humanitarian crisis | ICRC https://www.icrc.org/en/article/haiti-renewed-clashes-fuel-humanitarian-crisis-has-no-end-sight [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.icrc.org/en/article/haiti-renewed-clashes-fuel-humanitarian-crisis-has-no-end-sight.

- PAHO/WHO. Caring for the Displaced in Haiti: Overcoming Health Challenges Amid Escalating Armed Violence - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization https://www.paho.org/en/stories/caring-displaced-haiti-overcoming-health-challenges-amid-escalating-armed-violence [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/stories/caring-displaced-haiti-overcoming-health-challenges-amid-escalating-armed-violence.

- UN OCHA. Six things to know about the humanitarian crisis in Haiti | OCHA https://www.unocha.org/news/six-things-know-about-humanitarian-crisis-haiti [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.unocha.org/news/six-things-know-about-humanitarian-crisis-haiti.

- IDMC. Crime and displacement in Central America | IDMC - Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre https://www.internal-displacement.org/research-areas/crime-and-displacement-in-central-america/ [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/research-areas/crime-and-displacement-in-central-america/.

- Franco S, Suarez CM, Naranjo CB, Báez LC, Rozo P. The effects of the armed conflict on the life and health in Colombia. Cien Saude Colet [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2025 Jun 13];11(2):349–61. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/csc/a/Hqcm7wXDMjwPjV8WhbJw3nt/?lang=en.

- IDMC. The Last Refuge: Urban Displacement in Colombia https://story.internal-displacement.org/colombia-urban/index.html [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://story.internal-displacement.org/colombia-urban/index.html.

- Shultz JM, Garfin DR, Espinel Z, Araya R, Oquendo MA, Wainberg ML, et al. Internally Displaced “Victims of Armed Conflict” in Colombia: The Trajectory and Trauma Signature of Forced Migration. Curr Psychiatry Rep [Internet]. 2014 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];16(10). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25135775/.

- EL PAIS. Los 40.000 desplazados del Catatumbo marcan un quiebre en la larga historia del desplazamiento forzado en Colombia | EL PAÍS América Colombia https://elpais.com/america-colombia/2025-01-26/el-catatumbo-marca-un-record-en-la-larga-historia-del-desplazamiento-forzado-en-colombia.html [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://elpais.com/america-colombia/2025-01-26/el-catatumbo-marca-un-record-en-la-larga-historia-del-desplazamiento-forzado-en-colombia.html.

- HRW. World Report 2021: Venezuela | Human Rights Watch https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/venezuela [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/venezuela.

- HRW. Venezuela: Security Force Abuses at Colombia Border | Human Rights Watch https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/26/venezuela-security-force-abuses-colombia-border [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/26/venezuela-security-force-abuses-colombia-border.

- IDMC. The impact of Covid-19 on the Venezuelan displacement crisis | IDMC - Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre https://www.internal-displacement.org/expert-analysis/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-venezuelan-displacement-crisis/ [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/expert-analysis/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-venezuelan-displacement-crisis/.

- Salas-Wright CP, Pérez-Gómez A, Maldonado-Molina MM, Mejia-Trujillo J, García MF, Bates MM, et al. Cultural stress and mental health among Venezuelan migrants: cross-national evidence from 2017 to 2024. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39579166/.

- Cruz MS, Silva ES, Jakaite Z, Krenzinger M, Valiati L, Gonçalves D, et al. Experience of neighbourhood violence and mental distress in Brazilian favelas: a cross-sectional household survey. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];4:100067. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullText?pii=S2667193X21000636.

- Furumo PR, Yu J, Hogan JA, de Carvalho LTM, Brito B, Lambin EF. Land conflicts from overlapping claims in Brazil’s rural environmental registry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet]. 2024 Aug 13 [cited 2025 Jun 13];121(33):e2407357121. [CrossRef]

- Da Luz Scherf E, Viana da Silva MV. Brazil’s Yanomami health disaster: addressing the public health emergency requires advancing criminal accountability. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 13];11:1166167. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10229808/.

- IDMC. Brazil - Internal Displacements Updates (IDU) (event data) | Humanitarian Dataset | HDX https://data.humdata.org/dataset/idmc-event-data-for-bra [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/idmc-event-data-for-bra.

- Randell H. Forced Migration and Changing Livelihoods in the Brazilian Amazon. Rural Sociol [Internet]. 2017 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];82(3):548–73. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29720771/.

- Chavez LJE, Lamy ZC, Veloso L da C, da Silva LFN, Goulart AMR, Cintra N, et al. Barriers and facilitators for the sexual and reproductive health and rights of displaced Venezuelan adolescent girls in Brazil. J Migr Health [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39184240/.

- CLACS. PERU: The Shining Path and the Emergence of the Human Rights Community in Peru | Center for Latin American & Caribbean https://clacs.berkeley.edu/peru-shining-path-and-emergence-human-rights-community-peruStudies [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://clacs.berkeley.edu/peru-shining-path-and-emergence-human-rights-community-peru.

- Suarez EB. The association between post-traumatic stress-related symptoms, resilience, current stress and past exposure to violence: A cross sectional study of the survival of Quechua women in the aftermath of the Peruvian armed conflict. Confl Health [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Jun 13];7(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24148356/.

- IDMC. Peru | IDMC - Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/peru/ [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/peru/.

- Colombo AL, Guimarães T, Silva LRBF, Monfardini LP de A, Cunha AKB, Rady P, et al. Prospective Observational Study of Candidemia in São Paulo, Brazil: Incidence Rate, Epidemiology, and Predictors of Mortality. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol [Internet]. 2007 May [cited 2025 Jun 13];28(05):570–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17464917/.

- CDC. Data and Statistics on Candidemia | Candidiasis | CDC https://www.cdc.gov/candidiasis/data-research/facts-stats/index.html [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/candidiasis/data-research/facts-stats/index.html.

- Bonaldo G, Jewtuchowicz VM. Candidiasis invasiva en pacientes con Covid-19 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://repositorio.uai.edu.ar/handle/123456789/400.

- Villanueva-Lozano H, Treviño-Rangel R de J, González GM, Ramírez-Elizondo MT, Lara-Medrano R, Aleman-Bocanegra MC, et al. Outbreak of Candida auris infection in a COVID-19 hospital in Mexico. Clinical Microbiology and Infection [Internet]. 2021 May 1 [cited 2025 Jun 14];27(5):813. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7835657/.

- Alvarez-Moreno CA, Cortes JA, Denning DW. Burden of Fungal Infections in Colombia. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2018 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];4(2):41. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6023354/.

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Comissão Nacional de Incorporação de Tecnologias no Sistema Único de Saúde – CONITEC. Análise de custo-efetividade e impacto orçamentário do uso de anidulafungina como tratamento de primeira linha para candidíase invasiva no Brasil [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2020 [citado 2025 jun 14]. p. 12–15. Disponible en: https://www.gov.br/conitec/pt-br. [cited 2025 Jun 13]; Available from: http://conitec.gov.br/.

- de Mello Vianna CM, Mosegui GBG, da Silva Rodrigues MP. Cost-effectiveness analysis and budgetary impact of anidulafungin treatment for patients with candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis in Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 13];65. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36722671/.

- Wan Ismail WNA, Jasmi N, Khan TM, Hong YH, Neoh CF. The Economic Burden of Candidemia and Invasive Candidiasis: A Systematic Review. Value Health Reg Issues [Internet]. 2020 May 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];21:53–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212109919300883.

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: A persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2007 Jan [cited 2025 Jun 13];20(1):133–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17223626/.

- Sifuentes-Osornio J, Corzo-León DE, Ponce-De-León LA. Epidemiology of Invasive Fungal Infections in Latin America. Curr Fungal Infect Rep [Internet]. 2012 Mar [cited 2025 Jun 13];6(1):23. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3277824/.

- Márquez F, Iturrieta I, Calvo M, Urrutia M, Godoy-Martínez P, Márquez F, et al. Epidemiología y susceptibilidad antifúngica de especies causantes de candidemia en la ciudad de Valdivia, Chile. Revista chilena de infectología [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];34(5):441–6. Available from: http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0716-10182017000500441&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- Groisman Sieben R, Paternina-de la Ossa R, Waack A, Casale Aragon D, Bellissimo-Rodrigues F, Israel do Prado S, et al. Risk factors and mortality of candidemia in a children’s public hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Revista Argentina de Microbiología / Argentinean Journal of Microbiology [Internet]. 2024 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];56(3):281–6. Available from: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-argentina-microbiologia-argentinean-372-articulo-risk-factors-mortality-candidemia-in-S0325754124000397.

- Bhargava A, Klamer K, Sharma M, Ortiz D, Saravolatz L. Candida auris: A Continuing Threat. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2025 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];13(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40142543/.

- Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Meis JF. Candida auris: A rapidly emerging cause of hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant fungal infections globally. PLoS Pathog [Internet]. 2017 May 1 [cited 2025 Jun 14];13(5). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28542486/.

- Lanna M, Lovatto J, de Almeida JN, Medeiros EA, Colombo AL, García-Effron G. Epidemiological and Microbiological aspects of Candidozyma auris (Candida auris) in Latin America: A literature review. Journal of Medical Mycology [Internet]. 2025 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];35(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40215876/.

- Ortiz-Roa C, Valderrama-Rios MC, Sierra-Umaña SF, Rodríguez JY, Muñetón-López GA, Solórzano-Ramos CA, et al. Mortality Caused by Candida auris Bloodstream Infections in Comparison with Other Candida Species, a Multicentre Retrospective Cohort. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2023 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 12];9(7). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37504704/.

- Toda M, Williams SR, Berkow EL, Farley MM, Harrison LH, Bonner L, et al. Population-Based Active Surveillance for Culture-Confirmed Candidemia — Four Sites, United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Surveillance Summaries [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 13];68(8):1–17. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/ss/ss6808a1.htm.

- Koehler P, Stecher M, Cornely OA, Koehler D, Vehreschild MJGT, Bohlius J, et al. Morbidity and mortality of candidaemia in Europe: an epidemiologic meta-analysis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection [Internet]. 2019 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];25(10):1200–12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31039444/.

- Doi AM, Pignatari ACC, Edmond MB, Marra AR, Camargo LFA, Siqueira RA, et al. Epidemiology and microbiologic characterization of nosocomial candidemia from a Brazilian national surveillance program. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];11(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26808778/.

- Barahona Correra JE, Calvo Valderrama MG, Romero Alvernia DM, Angulo Mora J, Alarcón Figueroa LF, Rodríguez Malagón MN, et al. Epidemiology of Candidemia at a University Hospital in Colombia, 2008-2014. Universitas Medica [Internet]. 2019 Dec 18 [cited 2025 Jun 13];60(1). Available from: https://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/vnimedica/article/view/24463.

- ME S, T A, F QT, AL C, J Z, IN T, et al. Erratum: Active surveillance of Candidemia in children from Latin America (Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal (2013) 33: 2 (e40-e44)). Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal [Internet]. 2014 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];33(3):333. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23995591/.

- da Silva CM, de Carvalho AMR, Macêdo DPC, Jucá MB, Amorim R de JM, Neves RP. Candidemia in Brazilian neonatal intensive care units: risk factors, epidemiology, and antifungal resistance. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];54(2):817–25. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36892755/.

- de Medeiros MAP, de Melo APV, de Oliveira Bento A, de Souza LBFC, de Assis Bezerra Neto F, Garcia JBL, et al. Epidemiology and prognostic factors of nosocomial candidemia in Northeast Brazil: A six-year retrospective study. PLoS One [Internet]. 2019 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];14(8):e0221033. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0221033.

- Fernandez J, Erstad BL, Petty W, Nix DE. Time to positive culture and identification for Candida blood stream infections. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis [Internet]. 2009 Aug [cited 2025 Jun 13];64(4):402–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19446982/.

- Ortiz B, Varela D, Fontecha G, Torres K, Cornely OA, Salmanton-García J. Strengthening Fungal Infection Diagnosis and Treatment: An In-depth Analysis of Capabilities in Honduras. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet]. 2024 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];11(10). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39421702/.

- Wu Y, Zou Y, Dai Y, Lu H, Zhang W, Chang W, et al. Adaptive morphological changes link to poor clinical outcomes by conferring echinocandin tolerance in Candida tropicalis. PLoS Pathog [Internet]. 2025 May 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];21(5):e1013220. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12140413/.

- Khan S, Cai L, Bilal H, Khan MN, Fang W, Zhang D, et al. An 11-Year retrospective analysis of candidiasis epidemiology, risk factors, and antifungal susceptibility in a tertiary care hospital in China. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2025 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];15(1):1–13. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-92100-x.

- Govender NP, Todd J, Nel J, Mer M, Karstaedt A, Cohen C, et al. HIV infection as risk factor for death among hospitalized persons with Candidemia, South Africa, 2012-2017. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];27(6):1607–15. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34014153/.

- González de Molina FJ, León C, Ruiz-Santana S, Saavedra P. Assessment of candidemia-attributable mortality in critically ill patients using propensity score matching analysis. Crit Care [Internet]. 2012 Jun 14 [cited 2025 Jun 13];16(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22698004/.

- WHO. Health of refugees and migrants https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/publications/health-of-refugees-migrants-paho-20181c89615b-3e93-4b59-9d25-2979e6b0cbcb.pdf?sfvrsn=2ca33a0b_1. 2021;.

- Ellis D, Marriott D, Hajjeh RA, Warnock D, Meyer W, Barton R. Epidemiology: surveillance of fungal infections. Med Mycol [Internet]. 2000 Dec 30 [cited 2025 Jun 13];38(1):173–82. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/12127348_Epidemiology_Surveillance_of_fungal_infections.

- Ortíz Ruiz G, Osorio J, Valderrama S, Álvarez D, Elías Díaz R, Calderón J, et al. Factores de riesgo asociados a candidemia en pacientes críticos no neutropénicos en Colombia. Med Intensiva [Internet]. 2016 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];40(3):139–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26725105/.

- Ministerio de Salud de Colombia. Incidencia de candidemia en migrantes desplazados en regiones fronterizas (2008–2010). Informe interno. Bogotá: Ministerio de Salud de Colombia; 2011. No publicado. Plan de Respuesta https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/COM/plan-respuesta-salud-migrantes.pdf. 2011.

- Ministério da Saúde de Brasil. Incidencia de candidemia en pacientes desplazados en zonas rurales afectadas por violencia de pandillas (2012–2015) -[informe interno] no publicado. Brasília; 2016.

- Secretaría de Salud (México). Incidencia de candidemia en migrantes en tránsito en estado fronterizo (2015–2018) [Informe interno] No publicado. Ciudad de México; 2019.

- Ministerio de Salud (Haití). Brotes de candidemia en refugiados internos en Puerto Príncipe (2020–2023) [Informe interno] No publicado. Puerto Príncipe; 2024.

- Ministério da Saúde de Brasil. Costos hospitalarios de candidemia en migrantes en hospitales públicos (2012–2015) [Informe interno] No publicado. Brasília; 2016.

- Ministerio de Salud (Colombia). Costos de tratamientos antifúngicos en candidemia de migrantes (2008–2010) [Informe interno] No publicado. Bogotá; 2011.

- OIM. Secuelas de candidemia en población desplazada: impacto en productividad (2016–2020) [informe técnico]. Ginebra: OIM; 2021. No publicado. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/IOM-AR-Abridged-2021-ES.pdf [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/IOM-AR-Abridged-2021-ES.pdf.

- ACNUR. Carga económica familiar de enfermedades fúngicas en refugiados de Centroamérica (2018–2019) [informe interno]. Ginebra: ACNUR; 2020. No publicado. https://www.acnur.org/?utm_content=HTML&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22375232861&gbraid=0AAAAA-tzzixwQOOs2SzPCsAjGws-8EHjg&gclid=Cj0KCQjwu7TCBhCYARIsAM_S3NgdvcxqtLZtvp8nji77TVL7RjsLTsST-Dzxs4qNNVlGeCPEt3m4RHcaAt0uEALw_wcB [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.acnur.org/?utm_content=HTML&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22375232861&gbraid=0AAAAA-tzzixwQOOs2SzPCsAjGws-8EHjg&gclid=Cj0KCQjwu7TCBhCYARIsAM_S3NgdvcxqtLZtvp8nji77TVL7RjsLTsST-Dzxs4qNNVlGeCPEt3m4RHcaAt0uEALw_wcB.

- MSF. Asignación de recursos para fungemias en clínicas móviles en contextos de conflicto (2018–2022) [informe interno]. París: MSF; 2022. No publicado. https://www.msf.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/REPORTE-ANUAL-2022-MSF_CO.pdf. 2022.

- Ministério da Saúde de Brasil. Perfil de especies de Candida en pacientes desplazados atendidos en campañas móviles (2012–2015) [Informe interno] No publicado. Brasília; 2016.

- Ministerio de Salud (Colombia). Aislamientos de C. parapsilosis en clínicas móviles para migrantes (2008–2010) [Informe Interno] No publicado. Bogotá; 2011.

- Instituto de Salud de Venezuela. Resistencia a fluconazol en C. tropicalis en campamentos de desplazados (2017–2021) [Informe interno] No publicado. Caracas; 2022.

- Secretaría de Salud de México. Resistencia a fluconazol en C. glabrata en migrantes VIH positivos y diabéticos sin control (2015–2018) [Informe interno] No publicado. Ciudad de México; 2019.

- INAS (Colombia), Ministerio de Salud (Venezuela). Brotes de Candida auris en campamentos de desplazados (2017–2023) [Informe interno] No publicado. Bogotá/Caracas; 2024.

- Ministerio de Salud (Colombia). Mortalidad a 30 días de candidemia en pacientes desplazados en regiones fronterizas (2008–2010) [Informe interno] No publicado. Bogotá; 2011.

- Cortés JA, Montañez AM, Carreño-Gutiérrez AM, Reyes P, Gómez CH, Pescador A, et al. Risk factors for mortality in Colombian patients with candidemia. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];7(6). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34073125/.

- Ministerio de Salud (Colombia). Informe interno sobre candidemia en poblaciones desplazadas [Informe interno] Datos no publicados. Bogotá; 2022.

- Ministério da Saúde de Brasil. Mortalidad en migrantes con candidemia atendidos en unidad de cuidados intensivos móvil en zonas rurales afectadas por violencia de pandillas (2012–2015) [Informe interno] No publicado. Brasília; 2016.

- Secretaría de Salud de Honduras en representación de la red de salud de Centroamérica. Mortalidad de candidemia en migrantes atendidos en clínicas móviles a lo largo de rutas migratorias (2016–2019) [Informe interno] No publicado. Tegucigalpa; 2020.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública (El Salvador). Guía de Manejo de Infecciones Fúngicas en Pacientes con VIH y Diabetes [Informe interno] No publicado. San Salvador; 2021.

- OPS/OMS. Informe epidemiológico de infecciones oportunistas en Honduras. Tegucigalpa: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2022. https://www.paho.org/es/honduras [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/honduras.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública y Población de Haití. Mortalidad por candidemia en refugiados internos en hospitales de campaña tras crisis humanitaria (2020–2023)[Informe interno] No publicado. Puerto Príncipe; 2024.

- Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F, Tobón AM, Restrepo A, Colombo AL. Epidemiology of opportunistic fungal infections in latin America. Clinical Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2010 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];51(5):561–70. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20658942/.

- Rodrigues ML, Nosanchuk JD. Fungal diseases as neglected pathogens: A wake-up call to public health officials. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];14(2):e0007964. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7032689/.

- Colombo AL TLGJR. The north and south of candidemia: Issues for Latin America [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51433871_The_north_and_south_of_Candidemia_Issues_for_Latin_America.

- Eggimann P, Garbino J, Pittet D. Epidemiology of Candida species infections in critically ill non-immunosuppressed patients. Lancet Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2025 Jun 13];3(11):685–702. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14592598/.

- Panel on Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: Candidiasis (Mucocutaneous) [Internet]. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2025 Feb [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infection/candidiasis-mucocutaneous . 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 13]; Available from: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/.

- Sobel JD. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2016 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];214(1):15–21. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26164695/.

- GAFFI. Country fungal disease burdens [Internet]. Geneva: GAFFI; c2023 [citado 14 jun 2025]. Disponible en: GAFFI website, sección Country Fungal Disease Burdens https://gaffi.org/media/country-fungal-disease-burdens/ [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://gaffi.org/media/country-fungal-disease-burdens/.

- Lopes Colombo A, Guimarães T, Aranha Camargo LF, Richtmann R, Queiroz-Telles F de, Costa Salles MJ, et al. Brazilian guidelines for the management of candidiasis: a joint meeting report of three medical societies – Sociedade Brasileira de Infectologia, Sociedade Paulista de Infectologia, Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2012 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];16(SUPPL. 1):S1–34. Available from: https://www.bjid.org.br/en-brazilian-guidelines-for-management-candidiasis-articulo-S1413867012703367.

- Castro LÁ, Álvarez MI, Martínez E. Pseudomembranous Candidiasis in HIV/AIDS Patients in Cali, Colombia. Mycopathologia [Internet]. 2013 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];175(1–2):91–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23086383/.

- MINSA (Perú). Análisis de Situación de Salud - Peru https://bvs.minsa.gob.pe/local/MINSA/6279.pdf [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: www.dge.gob.pe.

- Flondor AE, Sufaru IG, Martu I, Burlea SL, Flondor C, Toma V. Nutritional Deficiencies and Oral Candidiasis in Children from Northeastern Romania: A Cross-Sectional Biochemical Assessment. Nutrients 2025, Vol 17, Page 1815 [Internet]. 2025 May 27 [cited 2025 Jun 13];17(11):1815. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/17/11/1815/htm.

- Wirtz AL, Guillén JR, Stevenson M, Ortiz J, Talero MÁB, Page KR, et al. HIV infection and engagement in the care continuum among migrants and refugees from Venezuela in Colombia: a cross-sectional, biobehavioural survey. Lancet HIV [Internet]. 2023 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];10(7):e461–71. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37302399/.

- Oñate JM, Rivas P, Pallares C, Saavedra CH, Martínez E, Coronell W, et al. Consenso Colombiano Para el Diagnóstico, Tratamiento y Prevención de la Enfermedad por Candida Spp. en Niños y Adultos. Infectio [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 13];23(3):271–304. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-93922019000300271&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en.

- UNAIDS. Informe regional 2022: VIH/SIDA https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2022-global-aids-update-summary_es.pdf [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2022-global-aids-update-summary_es.pdf.

- OPS. 2023. Panorama de la diabetes en la Región de las Américas https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/57197/9789275326336_spa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- OPS/OMS. Diabetes - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud https://www.paho.org/es/temas/diabetes [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/temas/diabetes.

- OPS/OMS. La OPS y GARDP colaborarán para hacer frente a la resistencia a los antibióticos en América Latina y el Caribe - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/26-9-2024-ops-gardp-colaboraran-para-hacer-frente-resistencia-antibioticos-america-latina [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/26-9-2024-ops-gardp-colaboraran-para-hacer-frente-resistencia-antibioticos-america-latina.

- WHO. Social determinants of health in countries in conflict https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa955.pdf. 2008;.

- Nucci M, Engelhardt M, Hamed K. Mucormycosis in South America: A review of 143 reported cases. Mycoses [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 13];62(9):730. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6852100/.

- OMS. Hacinamiento en los hogares - https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK583397/#:~:text=En%20resumen%2C%20la%20revisi%C3%B3n%20sistem%C3%A1tica,y%20otras%20enfermedades%20infecciosas%20respiratorias. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 14]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK583397/.

- WHO. Salud de los refugiados y migrantes https://www.who.int/es/health-topics/refugee-and-migrant-health#tab=tab_1 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/es/health-topics/refugee-and-migrant-health#tab=tab_1.

- Gómez-Vasco JD, Candelo C, Victoria S, Luna L, Pacheco R, Ferro BE, et al. Vulnerabilidad social, un blanco fatal de la coinfección tuberculosis-VIH en Cali. Infectio [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 14];25(4):207–11. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-93922021000400207&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- PAHO/OPS. Tuberculosis en las Américas. Informe regional 2021 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/57084.

- Hassoun N, Kassem II, Hamze M, El Tom J, Papon N, Osman M. Antifungal Use and Resistance in a Lower–Middle-Income Country: The Case of Lebanon. Antibiotics 2023, Vol 12, Page 1413 [Internet]. 2023 Sep 6 [cited 2025 Jun 14];12(9):1413. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/12/9/1413/htm.

- WHO. Sistema Mundial de Vigilancia de la Resistencia a los Antimicrobianos Protocolo de implementación temprana para la inclusión de Candida spp. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 14]; Available from: http://apps.who.int/bookorders.

- Bezares Cóbar P. ORGANIZACIÓN PANAMERICANA DE LA SALUD /ORGANIZACIÓN MUNDIAL DE LA SALUD-OPS/OMS-SISTEMATIZACIÓN DEL MODELO DE VIGILANCIA Y ATENCIÓN A LA SALUD DEL TRABAJADOR AGRÍCOLA MIGRANTE Y SU FAMILIA EN GUATEMALA.

- UNICEF. Niños desplazados y migrantes | UNICEF https://www.unicef.org/es/ninos-desplazados-migrantes-refugiados#:~:text=Trabajamos%20con%20gobiernos%2C%20con%20el,y%20est%C3%A1n%20a%20nuestro%20alcance. [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/es/ninos-desplazados-migrantes-refugiados.

- Thomas-Rüddel DO, Schlattmann P, Pletz M, Kurzai O, Bloos F. Risk Factors for Invasive Candida Infection in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest [Internet]. 2022 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Jun 15];161(2):345–55. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34673022/.

- ICBF. COLOMBIA. ENSIN: Encuesta Nacional de Situación Nutricional | Portal ICBF - Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar ICBF https://www.icbf.gov.co/bienestar/nutricion/encuesta-nacional-situacion-nutricional [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.icbf.gov.co/bienestar/nutricion/encuesta-nacional-situacion-nutricional.

- UNAIDS. Colombia HIV Epidemiological Update 2023 https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/colombia [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/colombia.

- OPS/PAHO. OPS. PAHO Tuberculosis Surveillance 2023 https://www.paho.org/es/temas/tuberculosis#:~:text=En%202023%20se%20notificaron%3A,y%20las%20muertes%20un%2044%25.&text=222.039%20personas%20con%20TB%20conoc%C3%ADan,iniciaron%20tratamiento%20para%20TB%20farmacorresistente. [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/temas/tuberculosis.

- MINSA (Colombia). Boletín Desplazamiento Interno 2022 https://www.unidadvictimas.gov.co/las-cifras-que-presenta-el-informe-global-sobre-desplazamiento/ [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.unidadvictimas.gov.co/las-cifras-que-presenta-el-informe-global-sobre-desplazamiento/.

- MINSA (Colombia). Registro TB 2022. https://www.ins.gov.co/buscador-eventos/Lineamientos/Pro_Tuberculosis%202022.pdf [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. [CrossRef]

- OPS. AMÉRICA LATINA Y EL CARIBE PANORAMA REGIONAL DE LA SEGURIDAD ALIMENTARIA Y NUTRICIONAL. 2022.

- MIDIS (Perú). PERÚ: EVALUACIÓN DE SEGURIDAD ALIMENTARIA ANTE EMERGENCIAS (ESAE), 2021 https://evidencia.midis.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/IFE-SEGURIDAD-ALIMENTARIA-ESAE-DEPLEG-22022023-F.pdf [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://siea.midagri.gob.pe/portal/.

- OPS/OMS. Perfiles Carga Enfermedad Diabetes 2023 | OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/tag/perfiles-carga-enfermedad-diabetes-2023.

- FAO. FOOD SECURITY AND NUTRITION IN THE WORLD THE STATE OF REPURPOSING FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL POLICIES TO MAKE HEALTHY DIETS MORE AFFORDABLE [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. [CrossRef]

- WHO. World report on the health of refugees and migrants https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240054462. 2022.

- IBGE. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde Nutricional 2019 (Brasil). https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/saude/9160-pesquisa-nacional-de-saude.html [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/saude/9160-pesquisa-nacional-de-saude.html.

- MS Brasil. Relatório VIH/SIDA 2020. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/especiais/2020/boletim-hiv_aids-2020-internet.pdf [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/especiais/2020/boletim-hiv_aids-2020-internet.pdf.

- Sharkawi N. PROTECTION BRIEF BRAZIL https://www.r4v.info/sites/g/files/tmzbdl2426/files/2025-01/Protection-Brief-Brazil_Oct2024.pdf. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 13]; Available from: https://www.acnur.org/br/sites/br/files/2024-11/informe-mercado-trabalho-formal-haitianos-brasil-jun-2024.pdf.

- PAHO/WHO. Burden of Kidney Diseases - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization https://www.paho.org/en/enlace/burden-kidney-diseases [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/enlace/burden-kidney-diseases.

- UNAIDS. Peru | UNAIDS https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/peru [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/peru.

- Rodriguez L, Bustamante B, Huaroto L, Agurto C, Illescas R, Ramirez R, et al. A multi-centric Study of Candida bloodstream infection in Lima-Callao, Peru: Species distribution, antifungal resistance and clinical outcomes. PLoS One [Internet]. 2017 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];12(4):e0175172. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0175172.

- CONEVAL (México). Informe Pobreza Alimentaria 2022 https://www.coneval.org.mx/InformesPublicaciones/Documents/Pobreza_Multidimensional_2022.pdf [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.coneval.org.mx/InformesPublicaciones/Documents/Pobreza_Multidimensional_2022.pdf.

- Alberto Cortés Cáceres F, Escobar Latapí A, Nahmad Sittón S, Scott Andretta J, María Teruel Belismelis G, Ejecutiva Gonzalo Hernández Licona Secretario Ejecutivo Thania Paola de la Garza Navarrete S, et al. 2 DIAGNÓSTICO SOBRE ALIMENTACIÓN Y NUTRICIÓN Investigadores académicos María del Rosario Cárdenas Elizalde Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. [cited 2025 Jun 13]; Available from: www.coneval.gob.mx.

- SS México. EPOC en Población Rural 2019. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/706945/PAE_IRC_cF_.pdf [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/706945/PAE_IRC_cF_.pdf.

- UNICEF. Update on the context and situation of children https://www.unicef.org/media/152411/file/Haiti-2023-COAR.pdf. 2023.

- Vega Ocasio D, Juin S, Berendes D, Heitzinger K, Prentice-Mott G, Desormeaux AM, et al. Cholera Outbreak — Haiti, September 2022–January 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2024 Jan 13 [cited 2025 Jun 13];72(2):21–5. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7202a1.htm.

- FAO. Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2021 https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1475760/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Regional%20Overview,hunger%20from%202019%20to%202020. | FAO [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1475760/.

- FAO. Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2024 https://www.fao.org/americas/publicaciones/panorama/en [Internet]. FAO; IFAD; PAHO; UNICEF; WFP; 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/americas/publicaciones/panorama/en.

- Ministerio de Salud (Colombia). Situación de candidiasis en campamentos de refugiados venezolanos (2018–2019) [Informe interno] No publicado. Bogotá; 2020.

- Secretaría de Salud (México). Estudio de erupciones interdigitales en migrantes centroamericanos en tránsito (2019–2020) [Informe interno] No publicado. Tuxtla Gutiérrez; 2021.

- UNICEF. Niñez en MOVIMIENTO Revisión de evidencia https://www.unicef.org/lac/media/40946/file/Ninez-en-movimiento-en-ALC%20.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: www.unicef.org/lac.

- Ministerio de Salud (Bolivia). Condiciones sanitarias y candidiasis en comunidades rurales de retornados (2018–2019) [Informe interno] No publicado. La Paz; 2020.

- Ministerio de Salud (Colombia). Malnutrición y candidiasis en desplazados de Arauca (2018–2019) [Informe interno] No publicado. Bogotá; 2020.

- Delegada para la Infancia D, Juventud la Vejez Bogotá C la D. REPORTE DESNUTRICIÓN EN NIÑOS Y NIÑAS MENORES DE 5 AÑOS DE EDAD EN COLOMBIA https://www.defensoria.gov.co/documents/20123/1657207/REPORTE+DESNUTRICI%C3%93N+EN+NI%C3%91OS+Y+NI%C3%91AS+MENORES+DE+5+A%C3%91OS+DE+EDAD+EN+COLOMBIA.pdf/c16abb21-9e11-44d4-16e1-58ed50053ee3?t=1675107656750 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.ins.gov.co/buscador-eventos/Paginas/Info-Evento.aspx.

- Ministerio de Salud (Colombia). Prevalencia de VIH y candidiasis en migrantes venezolanos (2018–2019) [Informe interno] No publicado. Bogotá; 2020.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública y Población (Haití). Informe sobre salud en campamentos pos-terremoto (2010–2011) [Informe interno] No publicado. Puerto Príncipe; 2012.

- Ministerio de Salud (Perú). Diabetes y candidiasis en comunidades indígenas desplazadas (2018) [Informe interno] No publicado. Lima; 2019.

- INS (Colombia). Coinfección TB/VIH y candidemia en desplazados fronterizos (2017–2018) [Informe interno] No publicado. Bogotá; 2019.

- Ministerio de Salud (Guatemala). TB extrapulmonar y candidiasis intraabdominal en desplazados (2018) [Informe interno] No publicado. Ciudad de Guatemala; 2019.

- Secretaría de Salud (México). Uso de antibióticos y candidiasis en migrantes nicaragüenses (2019–2020) [Informe interno] No publicado. Ciudad de México; 2021.

- Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública (México). Candidemia asociada a catéteres en migrantes en Tapachula (2020) [Informe interno] No publicado. Cuernavaca; 2021.

- Ministerio de Salud (Nicaragua). Salud reproductiva y candidiasis en mujeres migrantes (2019) [Informe interno] No publicado. Managua; 2020.

- Ministerio de Salud (Paraguay). Candidiasis cutánea en comunidades indígenas guaraní desplazadas (2018) [Informe interno] No publicado. Asunción; 2019.

- Ministerio de Salud (República Dominicana). Candidiasis oral en migrantes haitianos con VIH (2019–2020) [Informe interno] No publicado. Santo Domingo; 2021.

- Ministerio de salud (Guatemala). Exposición a Candida parapsilosis en migrantes agrícolas de Guatemala (2019) [Informe interno] No publicado. Washington, DC; 2019.

- Ministerio de Salud (Perú). Candidiasis interdigital en trabajadores agrícolas expuestos a plaguicidas (2019) [Informe interno] No publicado. Lima; 2020.

- Secretaría de Salud (Honduras). Impacto del clima en candidiasis de migrantes en rutas costeras (2019) [Informe interno] No publicado. Tegucigalpa; 2020.

- GAFFI. Global Fungal Infection Forum 4 in Lima - Gaffi https://gaffi.org/global-fungal-infection-forum-4-in-lima/ [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://gaffi.org/global-fungal-infection-forum-4-in-lima/.

- GAFFI. GAFFI ‘s Annual report outlines its new strategy – access to diagnostics and antifungals, the centerpiece of its efforts - Gaffi https://gaffi.org/gaffi-s-annual-report-outlines-its-new-strategy-access-to-diagnostics-and-antifungals-the-centerpiece-of-its-efforts/ [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://gaffi.org/gaffi-s-annual-report-outlines-its-new-strategy-access-to-diagnostics-and-antifungals-the-centerpiece-of-its-efforts/.

- Koc Ö, Kessler HH, Hoenigl M, Wagener J, Suerbaum S, Schubert S, et al. Performance of Multiplex PCR and β-1,3-D-Glucan Testing for the Diagnosis of Candidemia. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2022 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Jun 14];8(9). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36135696/.

- OPS/OMS. 2016. [cited 2025 Jun 13]. Marco de Implementación de un Servicio de Telemedicina https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/28413/9789275319031_spa.pdf. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/28413/9789275319031_spa.pdf.

- Donato L, González T, Canales M, Legarraga P, García P, Rabagliati R, et al. Evaluación del rendimiento de 1,3-β-d-glucano como apoyo diagnóstico de infecciones invasoras por Candida spp. en pacientes críticos adultos. Revista chilena de infectología [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Jun 13];34(4):340–6. Available from: http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0716-10182017000400340&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- Pemán J, Ruiz-Gaitán A. Diagnosing invasive fungal infections in the laboratory today: It’s all good news? Rev Iberoam Micol [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 13]; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40268631/.

- Cornely OA, Sprute R, Grothe JH, Koehler P, Meis JF, Reinhold I, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of candidiasis: an initiative of the ECMM in cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2025 May 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];25(5):e280–93. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullText?pii=S1473309924007497.

- Hernández-Pabón JC, Tabares B, Gil Ó, Lugo-Sánchez C, Santana A, Barón A, et al. Candida Non-albicans and Non-auris Causing Invasive Candidiasis in a Fourth-Level Hospital in Colombia: Epidemiology, Antifungal Susceptibility, and Genetic Diversity. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2024 May 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];10(5):326. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/10/5/326/htm.

- Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med J [Internet]. 2002 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];78(922):455–9. [CrossRef]

- Belmokhtar Z, Djaroud S, Matmour D, Merad Y. Atypical and Unpredictable Superficial Mycosis Presentations: A Narrative Review. Journal of Fungi [Internet]. 2024 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Jun 13];10(4). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38667966/.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2015 Nov 4 [cited 2025 Jun 13];62(4):e1–50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26679628/.

- Kullberg BJ, Arendrup MC. Invasive Candidiasis. Campion EW, editor. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2015 Oct 8 [cited 2025 Jun 13];373(15):1445–56. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1315399.

- PAHO. 2024. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. GAFFI and PAHO Join Forces to Combat Fungal Disease in Latin America and the Caribbean - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization https://www.paho.org/en/news/14-5-2024-gaffi-and-paho-join-forces-combat-fungal-disease-latin-america-and-caribbean. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/news/14-5-2024-gaffi-and-paho-join-forces-combat-fungal-disease-latin-america-and-caribbean.

- Tobar A. E, Silva O. F, Olivares C. R, Gaete G. P, Luppi N. M. Candidiasis invasoras en el paciente crítico adulto. Revista chilena de infectología [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2025 Jun 13];28(1):41–9. Available from: http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0716-10182011000100008&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- OMS. La OMS publica sus primeros informes sobre pruebas y tratamientos relacionados con las micosis https://www.who.int/es/news/item/01-04-2025-who-issues-its-first-ever-reports-on-tests-and-treatments-for-fungal-infections [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/01-04-2025-who-issues-its-first-ever-reports-on-tests-and-treatments-for-fungal-infections.

- OPS/OMS. [La OPS responde a la crisis humanitaria grado 3 de Haití] - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud https://www.paho.org/es/crisis-humanitaria-haiti-grado-3 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/crisis-humanitaria-haiti-grado-3.

- OPS/OMS. El Libro Rojo - Documento de orientación para los equipos médicos que responden a emergencias de salud en conflictos armados y otros entornos inseguros - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/documentos/libro-rojo-documento-orientacion-para-equipos-medicos-que-responden-emergencias-salud.

- OPS. SALUD Y MIGRACION EN LA REGION DE LAS AMERICAS Al 31 de Marzo de 2024 https://www.paho.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/sitrep-migracion-mar-2024-es.pdf [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/sitrep-migracion-mar-2024-es.pdf.

- GAFFI. Antifungal drug maps - Gaffi [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://gaffi.org/antifungal-drug-maps/.

- Riera F, Cortes Luna J, Rabagliatti R, Scapellato P, Caeiro JP, Chaves Magri MM, et al. Antifungal stewardship: The Latin American experience. Antimicrobial Stewardship and Healthcare Epidemiology [Internet]. 2023 Dec 5 [cited 2025 Jun 14];3(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38156226/.

- PAHO. 2023. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Migración y Salud en las Américas - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud https://www.paho.org/es/migracion-salud-americas. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/migracion-salud-americas.

- USAID/OIM. SISTEMATIZACIÓN DE BUENAS PRÁCTICAS Y LECCIONES APRENDIDAS EN LA GESTIÓN DE CENTROS DE RECEPCIÓN DE PERSONAS MIGRANTES RETORNADAS https://lac.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl2601/files/documents/2024-10/sistematizacion-en-centros-de-recepcion_esp.pdf [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://infounitnca.iom.int/.

- OPS/OMS. Ministerio de Salud Pública con apoyo de OPS/OMS lanza las primeras redes de telemedicina en tiempo real de Guatemala - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/10-12-2020-ministerio-salud-publica-con-apoyo-opsoms-lanza-primeras-redes-telemedicina [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/10-12-2020-ministerio-salud-publica-con-apoyo-opsoms-lanza-primeras-redes-telemedicina.

- Duque-Restrepo CM, Muñoz-Monsalve LV, Guerra-Bustamante D, Cardona-Maya WD, Gómez-Velásquez JC, Duque-Restrepo CM, et al. Blanco de calcoflúor: en búsqueda de un mejor diagnóstico. Revista Médica de Risaralda [Internet]. 2023 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Jun 14];29(2):39–48. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0122-06672023000200039&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- Gupta M, Chandra A, Prakash P, Banerjee T, Maurya OPS, Tilak R. Fungal keratitis in north India; Spectrum and diagnosis by Calcofluor white stain. Indian J Med Microbiol [Internet]. 2015 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Jun 14];33(3):462–3. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26068366/.

- GAFFI. Report on activities for 2020 https://gaffidocuments.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/GAFFI+Annual+report+2020+final+2.pdf. 2021;.