1. Introduction

In the face of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, the world is reminded of the critical importance of the humoral immune response. The humoral immune response, which is part of the adaptive immune response alongside the T-cell mediated responses, is mediated by B cells [

1]. Naive B cells express IgM or IgD on their surface, serving as receptors for antigen recognition. After immunization or infection, activated naive B cells undergo class switching recombination (CSR), which involves a change in the heavy-chain constant (C) region to another isotype. This results in a change of the B-cell surface antibodies from IgM/IgD to secretable IgG, IgE or IgA [

2]. CSR is guided by cytokines, T-cell help, antigen presentation, B-cell receptor engagement and transcription factors. These signals determine the eventual antibody isotype, customizing the effector function of the antibody, enhancing its ability to eliminate the specific pathogen that induced the response [

3,

4]. Activated B cells can also undergo another process known as somatic hypermutation (SHM), which involves introducing mutations in the variable (V) region of the heavy and light chain of the immunoglobulin. This process leads to the production of antibodies with increased affinity and avidity for their target antigen [

5].

The significance of antibodies is further underscored by their status as a key output of vaccination, with most vaccines relying on the generation of protective antibodies to confer immunity against infectious diseases [

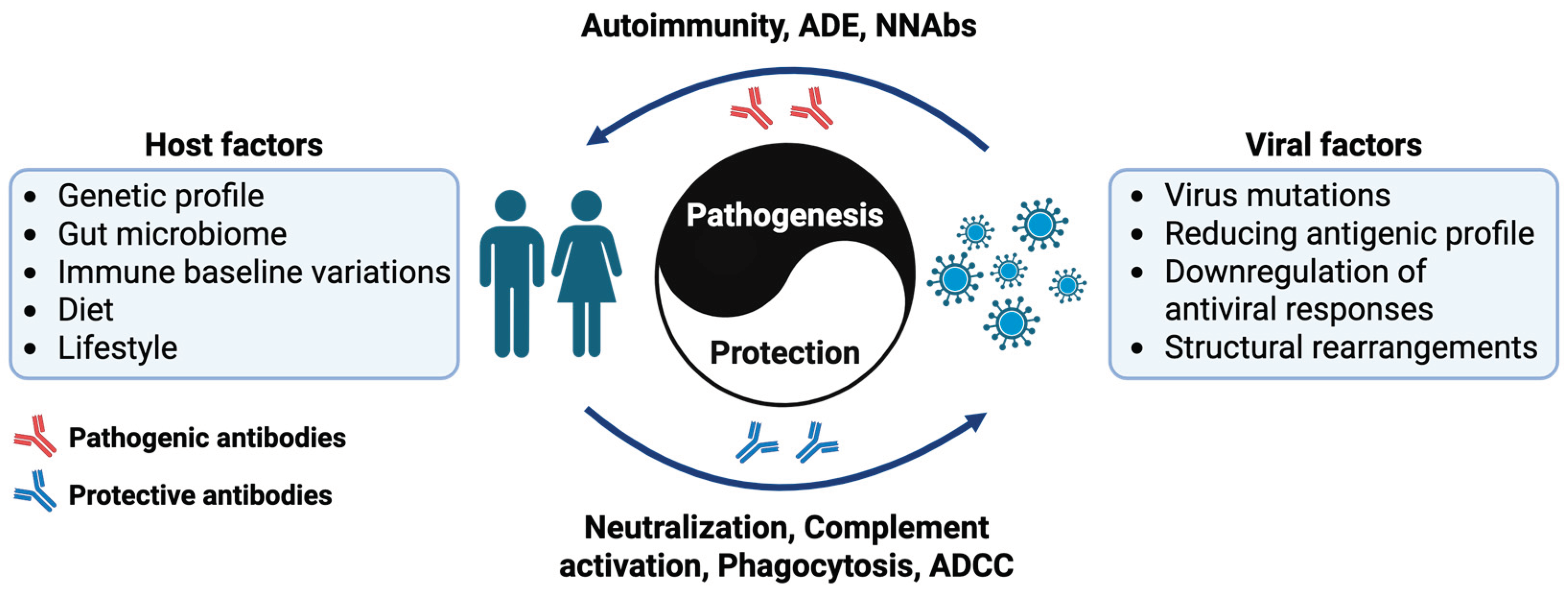

6]. The emphasis on eliciting robust antibody responses through vaccination highlights the critical importance of these molecules in preventing infection and disease. However, the complex relationship between antibodies and pathogens is a double-edged sword [

7]. On one hand, antibodies can provide life-saving immunity against deadly diseases. On the other hand, they can also contribute to immune evasion, antibody-dependent enhancement of infection, and autoimmune disorders [

7] (

Figure 1). Despite these challenges, advances in antibody engineering and technology have opened up new avenues for the development of antibody-based therapies, offering hope for the prevention and treatment of emerging infectious diseases [

8]. This review will delve into the intricate world of antibodies, exploring their role in immune protection, their potential pitfalls, and the exciting possibilities for harnessing their power to combat the growing threat of emerging pathogens.

2. Role of Antibodies in Emerging and Re-Emerging Infections

Antibodies play an important role in the immune response against emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Their functions extend beyond simple neutralization, encompassing mechanisms such as complement activation, phagocytosis, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). Depending on the pathogen, some antibodies confer long-term immunity, while others wane over time, affecting reinfection susceptibility and vaccine efficacy [

9]. While antibodies are primarily protective, under certain circumstances, they contribute to disease pathology. These pathogenic effects arise due to unintended immune activation, molecular mimicry, or immune complex formation, leading to complications such as autoimmune diseases, antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of infection, and ineffective immune responses due to antigenic variation. Understanding these mechanisms will be crucial for mitigating the risks associated with antibody-based therapies and vaccines, and aids in the future development of safer and more effective treatments.

2.1. Protective Role of Antibodies in Infectious Diseases

2.1.1. Neutralization

Neutralization is one of the primary mechanisms by which antibodies confer protection against pathogens. The process of neutralization involves antibodies binding to viruses, blocking their ability to attach to host cells [

10]. This type of neutralization is termed "steric hindrance", where the physical presence of the antibody blocks viral entry points [

10,

11]. Another significant mechanism is through either the induction or blocking of conformational changes on the virus, rendering the virus non-infectious [

11,

12]. These conformational changes can either directly block the virus's ability to interact with host cell receptors or expose the virus to other components of the immune system, such as complement proteins, which can further inactivate the virus [

11]. Antibodies can also facilitate the aggregation of viruses, making it more difficult for the viruses to navigate to and infect host cells [

10,

13]. This aggregation also makes it easier for immune cells to recognize and eliminate the virus. In this process, antibodies act as opsonins which mark the viruses for downstream destruction [

14]. In addition, antibodies can also block endosomal cleavage or endosomal receptor binding. This is critical for viruses that enter endosomes. In an in-direct context of neutralization, antibodies can block viral egress, leading to the accumulation of virus progenies at the surface of the infected cells [

12].

2.1.2. Activation of the Complement System

The complement system is an integral component of the innate immune response, consisting of over 50 proteins that interact in a highly regulated manner to combat infections [

15]. Activation of the complement system occurs via three primary pathways: the classical pathway, the lectin pathway, and the alternative pathway, all of which converge at the formation of C3 convertases that cleave C3 molecules into C3a and C3b, leading to downstream immune effector functions such as opsonization, inflammation, and pathogen lysis [

14,

15].

The classical pathway is the most common pathway mediated by antibodies (both IgM and IgG). When these antibodies bind to specific antigens on the surface of a pathogen, they form antigen-antibody complexes that serve as molecular platforms for the binding of the C1 complex. The activation of the C1 complex leads to a cascade of events that ultimately results in the cleavage of C3 into C3a and C3b, amplifying the complement cascade and initiating key immune processes such as recruitment of inflammatory cells, opsonization of pathogens, and formation of the membrane attack complex [

16]. These processes enhance pathogen clearance and bridge innate and adaptive immunity [

16].

While complements are generally protective against infectious agents, it is worthwhile to note that complements have also been implicated in the modulation of ADE of flavivirus infections [

17]. A comprehensive review of this phenomenon was previously published by Byrne and Talarico [

18].

2.1.3. Antibody-Mediated Phagocytosis

Another protective mechanism of antibodies is through antibody-mediated phagocytosis, in which antibodies act as opsonins to enhance the recognition and uptake of pathogens by immune cells such as macrophages and neutrophils [

14]. This process is initiated when antibodies interact with the Fc receptors (FcRs) expressed on the surface of the immune cells. This interaction triggers downstream signaling pathways that promote the engulfment of antibody-coated particles. Among the key FcRs, Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) are known to mediate phagocytosis. FcγRs are classified into several classes in humans, including FcγRI (CD64), FcγRIIa (CD32a), FcγRIIb (CD32b), FcγRIIc (CD32c) FcγRIIIa (CD16a) and FcγRIIIb (CD16b), which differ in their affinity for IgG and their ability to mediate inflammatory or anti-inflammatory responses. Except for FcγRIIb and FcγRIIIb, all other FcγRs contain intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine based activating motifs (ITAM). Instead, FcγRIIb contains the immunoreceptor tyrosine based inhibitory motifs (ITIM) and FcγRIIIb is a decoy receptor and lacks intracellular signalling motifs [

19,

20].

The balance between activating and inhibitory FcγRs determines the immune outcome, with activating receptors promoting phagocytosis and inflammation, and inhibitory receptors limiting excessive inflammation [

21]. Additionally, FcγRs are involved in various effector functions, including antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and cytokine production. Dysregulation of FcγRs-mediated pathways has also been linked to autoimmune diseases [

22] such as: systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), first described by Hargraves in 1948 [

23], who observed neutrophils engulfing nuclear material (LE cells), indicating immune complex formation mediated by autoantibodies; rheumatoid arthritis (RA), initially reported by Waaler in 1940 [

24], who identified rheumatoid factor (RF), an autoantibody binding the Fc region of IgG, causing immune complex-driven joint inflammation; and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, first described by Davies et al. in 1982 [

25], who discovered autoantibodies targeting neutrophil cytoplasmic components, activating neutrophils and subsequently causing vascular injury.

Interestingly, it was reported recently that other host factors could affect FcγRs function. In an animal model of rheumatoid arthritis, it was determined that Dectin-1, a C-type lectin receptor, enhances the binding of IgG to the low-affinity FCγRIIb. This interaction reprograms the monocytes, ultimately causing an inhibition of osteoclastogenesis [

26]. Other factors, such as sialylation, could also impact the functions of antibodies and their binding to the FcRs [

27]. The role of sialylation of antibodies in the context of infectious diseases has been comprehensively reviewed by Irvine and Alter [

28].

2.1.4. Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytoxicity (ADCC)

Antibodies can also participate in the elimination of virus-infected cells through a mechanism known as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), which leverages the immune system's effector cells. During viral infections, antibodies bind to viral antigens on the surface of infected cells and immune cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils which recognize these antibody-coated targets through their surface FcRs. This triggers a response that ultimately leads to the infected cell's death [

29]. Specifically, NK cells express FcγRIIIa that binds to the Fc region of IgG antibodies, inducing the release of cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzymes [

30]. This mechanism is crucial in controlling viral infections, including influenza, which is notorious for its high mutation rate in the viral glycoprotein, hemagluttinin (HA) [

31]. Notably, it was reported that ADCC-mediating antibodies targeting a specific 14 amino acid fusion peptide sequence at the N-terminus of the HA2 subunit are able to induce ADCC against a wide range of influenza viruses [

32,

33]. Interestingly, the binding affinity between the antibodies and FcγRIII on NK cells determines the strength of ADCC. Recently, it was reported that afucosylation of broadly neutralizing antibodies targeting human immunodeficieny virus (HIV)-1 envelope glycoprotein potentiates activation and degranulation of NK cells, marked by the increased in CD107

+IFNγ

+ cells. It was also reported that afucosylated antibodies could overcome the inhibitory signals in exhausted PD-1

+ and TIGIT

+ NK cells, leading to their activation [

34]. This exemplifies the importance of gaining a greater understanding of glycosylation on antibodies function in human diseases [

35].

2.2. Pathogenic Role of Antibodies in Infectious Diseases

2.2.1. Autoimmunity and Autoantibodies

Autoimmunity can arise when viral infections induce immune responses that mistakenly target host tissues, through mechanisms such as autoantibody production, molecular mimicry, bystander activation, and epitope spreading [

36].

Autoantibodies generated during infections can be transient, resolving after clearance of the pathogen, or persist long-term, leading to chronic autoimmune conditions [

36]. For example, autoantibodies against interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) generated during SARS-CoV-2 infection can persist, exacerbating long COVID and severe acute respiratory syndrome by impairing host immune responses [

37]. Clinical studies indicate that the presence and higher titers of anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies correlate significantly with severe or critical COVID-19 cases, suggesting their potential role as biomarkers for predicting disease severity [

38]. These autoantibodies can functionally neutralize IFN-γ by effectively inhibiting its signaling pathways, which phosphorylate STAT1, thereby impairing critical antiviral defenses and exacerbating disease outcomes [

38].

Molecular mimicry, which depends on structural similarity between viral antigens and host proteins, is mediated by cross-reactive antibodies produced by the B cells during the infection. A notable example is Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), where antibodies generated against EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) cross-react with similar epitopes found on host myelin proteins. This cross-reactivity results in autoreactive B cell activation and production of pathogenic autoantibodies, contributing to autoimmune pathology such as multiple sclerosis (MS) [

39]. In fact, molecular mimicry between EBNA1 and other CNS proteins such as anoctamin-2 (ANO2) [

40], alpha-B crystallin (CRYAB) [

41] and myelin basic protein (MBP) [

42] has also been described.

It was also recently reported that children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), develop a unique immune response following SARS-CoV-2 infection, targeting a distinct domain within the viral nucleocapsid protein that bears sequence similarity to the self-protein SNX-8 [

43]. Likewise, arboviruses like Zika virus (ZIKV) and dengue virus (DENV) have also been implicated in autoimmunity through the production of autoantibodies and molecular mimicry [

44]. For instance, ZIKV neutralizing antibodies have been shown to cross-react with neuronal membrane gangliosides in ZIKV-associated GBS cases, suggesting that molecular mimicry is a potential mechanism used by ZIKV to cause neurological damage [

45]. In these GBS patients, autoantibodies against host glycolipids were detected [

45]. Similarly in DENV, it was reviewed by Zhou et al. (2024) that molecular mimicry could lead to the production of autoantibodies targeting platelets, endothelial cells and coagulatory factors, ultimately affecting thrombocytopenia and plasma leakage during severe dengue [

44].

Bystander activation describes the non-specific stimulation of immune cells during infection, which can inadvertently activate autoreactive B and T cells. Chronic cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection exemplifies this mechanism by persistent immune activation, potentially leading to autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [

46]. In COVID-19 patients, bystander activation of polyclonal autoreactive B cells has been reported. Activation leads to the production of a broad range of autoantibodies, albeit none of the elevated autoantibodies were associated with disease severity [

47]. Likewise, infection with either SARS-CoV-2 or Influenza, led to an expansion of CCR6

+CXCR3

- bystander memory B cells (MBCs) alongside the CCR6

+CXCR3

+ virus-specific MBCs in the lungs of the infected animals. These bystander MBCs differ in their origin and transcriptional programs and elicit antibodies that are non-specific and offer no protection [

48]. The role of such bystander cells in the context of infection should be further studied.

Epitope spreading refers to the progressive diversification of immune responses, initially targeting a limited antigenic site and subsequently extending to other epitopes within the same or different antigens. For example, in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, initial immune responses may broaden over time, contributing to autoimmune manifestations like cryoglobulinemia and Sjögren’s syndrome [

49]. Interestingly, in the context of EBV infection, Sattarnezhad and team hypothesized intramolecular epitope spreading as a mechanism to increase the breadth of antibody responses against GlialCAM, potentially increasing its potential to cause harm[

50]. In mice, injections with EBNA1 peptides of different length elicited cross-reactive antibodies to dsDNA, different from the cross-reactive epitope [

50,

51].

2.2.2. Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE)

ADE occurs when non-neutralizing or sub-neutralizing antibodies facilitate viral attachment (extrinsic ADE) or entry (intrinsic ADE) into host cells, paradoxically worsening the infection [

52,

53]. This phenomenon has been extensively studied in the context of Flavivirus infections, such as dengue virus (DENV). Antibodies generated against one serotype of DENV can bind but fail to neutralize a different serotype, forming immune complexes that interact with FcγRs on monocytes, macrophages, or dendritic cells. This process enhances viral uptake and replication, leading to severe disease manifestations like dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome [

54]. Clinically, this mechanism can significantly increase disease severity and contribute to severe complications such as myocarditis, characterized by elevated cardiac enzymes, arrhythmias, heart failure, and increased mortality risk [

55]. In a clinical setting, patients experiencing antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue infection demonstrated notably higher levels of inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP), prolonged prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), as well as an increased requirement for intensive care unit admission and longer hospital stays [

55]. Furthermore, related viruses can induce cross-reactive antibodies that may impact the outcome of infection caused by other viruses within the same viral family. For example, it was reported that the presence of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) neutralizing antibodies was associated with an increased presence of DENV symptomatic infection compared to asymptomatic infection, with the symptomatic infection also lasting for a longer duration [

56]. Likewise, in a separate study, vaccination with a single dose of inactivated Vero cell-derived JEV vaccine, led to production of antibodies capable of enhancing DENV infection at sub-neutralizing levels [

57]. Interestingly, pre-exisiting immunity to JEV SA14-14-2 vaccination, provided protection against Zika virus (ZIKV) in a lethal mouse model [

58]. However, the presence of antibodies to both DENV and West Nile virus (WNV) was found to enhance ZIKV infection [

59,

60]. These examples show that ADE is a complex and dynamic phenomenon that needs to be better understand, particularly in the context of viral infection and vaccine development.

Nevertheless, ADE has also been observed in other viral infections, including those caused by coronaviruses. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some studies suggested that antibodies generated against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein might enhance viral entry under certain conditions. These effects are mediated through FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIa expressed on immune cells, which bind to antibody-virus complexes and facilitate endocytosis [

61]. While evidence of ADE in SARS-CoV-2 infection remains limited and controversial, it raises concerns about the design of vaccines and monoclonal antibody therapies, particularly in populations previously exposed to the virus or related coronaviruses [

15,

61].

Beyond flaviviruses and coronaviruses, ADE has been demonstrated for other viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [

62], measles virus [

63], and Ebola virus [

64] and Alphaviruses [

65,

66]. The underlying mechanisms of ADE differ among viruses, but they generally involve FcR-mediated viral entry and increased inflammatory responses leading to tissue damage [

67]. Understanding the molecular determinants of ADE is essential to designing safer vaccines and therapeutic antibodies that avoid this adverse immune phenomenon. Moreover, vaccine designs should focus on eliciting robust neutralizing antibody responses while reducing non-neutralizing antibodies. Careful selection of antigens, coupled with the optimization of vaccine formulations and consideration of immune responses in diverse populations, including those with pre-existing immunity to related viruses will be crucial in the development of safer and more effective vaccines against viruses where ADE is a concern [

68]. This is especially important in regions with high prevalence of viral infections and limited access to healthcare resources.

2.2.3. Non-Neutralizing Antibodies (NNAbs)

Non-neutralizing antibodies (NNAbs) represent a subset of antibodies that play essential roles in the immune defense system. These antibodies contribute to immune protection by coordinating responses that complement the actions of neutralizing antibodies, providing a multifaceted strategy for controlling pathogens.

A significant function of NNAbs is antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP). This mechanism involves the opsonization of pathogens or infected cells by NNAbs, effectively marking them for engulfment by phagocytic cells such as macrophages and neutrophils [

69]. The Fc regions of NNAbs bind to FcRs on phagocytes, enabling the internalization and degradation of immune complexes. ADCP has been identified as a crucial protective mechanism in various infections, including HIV, where NNAbs help control viral replication and restrict the spread of the virus [

70].

Additionally, NNAbs play crucial roles in vaccine-induced immunity. The RV144 HIV vaccine trial identified NNAbs as correlates of protection, highlighting their ability to reduce viral loads and transmission via FcR-mediated functions. Such findings emphasize the importance of eliciting NNAbs through vaccine strategies, complementing neutralizing antibody responses [

70].

Beyond these effector functions, NNAbs are involved in modulating immune responses by enhancing antigen presentation by dendritic cells. Immune complexes formed by NNAbs bind to Fc receptors (FcRs) on dendritic cells, facilitating the uptake, processing, and subsequent presentation of antigens to T cells [

69]. This interaction not only promotes dendritic cell maturation but also enhances adaptive immune responses, bridging innate and adaptive immunity. Moreover, pre-existing antibodies elicited by HIV infections have shown cross-reactivity with glycosylated epitopes on SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins [

71]. Antibodies initially targeting HIV envelope glycoproteins have also demonstrated cross-reactivity with influenza virus hemagglutinin due to conserved glycan structures, suggesting potential protective roles against diverse pathogens through glycan-based interactions [

71]. Such observations emphasize the role of NNAbs in infectious disease outcomes and vaccine strategy design.

NNAbs can also mediate detrimental effects through ADE. At sub-neutralizing levels, NNAbs can bind to viral antigens without effectively preventing viral entry. This binding forms virus-antibody complexes that interact with FcγRs on immune cells including monocytes, macrophages, or dendritic cells. These interactions facilitate increased internalization of viruses, enhancing viral replication within these cells [

15]. Furthermore, NNAbs can trigger complement activation, leading to inflammation and tissue damage. Such mechanisms have been notably observed in viral infections like dengue virus, highlighting a critical risk factor in vaccine development [

15].

3. Factors Influencing Antibody-Mediated Immunity

Pathogens employ various immune evasion strategies to circumvent detection and elimination by the host's immune system. These mechanisms ensure their survival, persistence, and ability to establish long-term infections.

3.1. Viral-Based Factors

Pathogens employ various strategies to evade host immune system. Pathogens like Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 undergo frequent mutations in their surface proteins, allowing them to evade antibody recognition. For example, mutations in the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 enable the viruses to escape neutralizing antibodies [

15]. This mechanism is also prominent in influenza virus, which undergoes antigenic drift and shift in its hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins [

72]. Similarly, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) continuously mutates its envelope glycoprotein (gp120), creating a moving target for the immune system and thwarting the development of effective neutralizing antibodies [

73]. This may lead to prolonged or severe disease and increases the transmission of these viruses. As such, it is important that researchers are actively monitoring pathogen evolution, which will help in predicting the emergence of new strains and inform vaccine development.

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) achieve immune evasion by entering a latent state during which they minimize their antigenic profile. In latency, EBV expresses a limited set of viral proteins, such as EBNA-1 and LMP-2, avoiding detection by host antibodies and cytotoxic T cells [

74]. Another mechanism utilized by EBV, employs the viral protein BGLF5 to degrade host RNA and inhibit the expression of key antiviral molecules. This reduces the efficiency of antigen presentation and neutralizing antibody production, enabling the virus to evade both innate and adaptive immunity [

74].

Pathogens can also directly interfere with antibody-mediated responses. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) encodes glycoproteins such as gE and gI, which form a complex that binds to the Fc region of IgG. This Fc-binding activity prevents the interaction of IgG with FcRs on phagocytes, effectively neutralizing antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis [

75].

It is also possible for viruses to protect key epitopes from antibody recognition through glycan shielding or structural rearrangements. HIV is a prominent example, as it incorporates a dense glycan shield over its envelope protein, preventing antibody binding to conserved epitopes [

76]. Additionally, structural rearrangements in the spike protein of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, conceal receptor-binding domains during specific stages of the viral life cycle, reducing antibody access [

77].

3.2. Host-Based Factors

The duration and effectiveness of antibody responses vary among individuals due to genetic differences [

78,

79], immune history [

80,

81,

82], and co-existing conditions [

83]. Some individuals generate long-lasting protective antibodies, while others exhibit rapid waning, influencing susceptibility to reinfection and vaccine efficacy [

83]. Factors such as HLA haplotypes, Fc receptor polymorphisms [

84], and baseline inflammation levels [

85] can modulate the quality and persistence of antibody responses. Interestingly, in a recent report on how immune history could affect antibody responses, Lv et al. demonstrated that in mice, antibodies raised against pre-2009 H1N1 strains can significantly affect both anti-HA and anti-NA antibody responses when these animals were exposed to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 strain [

82].

Gut microbiome, which participates in immune system development and function, can affect the quality and magnitude of the host’s humoral responses to an infection [

86]. Dybiosis, which is an imbalance in the gut microbiome, compromises immune function and this could substantially reduce the effectiveness of antibody responses. Consequently, future research should prioritize modulating host microbiome to bolster immune function for better vaccine efficacy [

87].

Non-genetic factors such as diet, lifestyle, previous infection history and vaccination status can also influence antibody-mediated immunity [

82,

88,

89,

90]. For example, nutritional deficiencies in vitamin D and zinc have been linked to impaired B cell function and suboptimal vaccine responses [

91]. Immune imprinting, rooted from the fundamentals of immunological memory, can impact vaccination-induced antibody responses, especially against viruses that undergo rapid evolution (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) [

90]. Additionally, chronic infections involving tuberculosis or helminth infestations can skew immune responses toward a regulatory phenotype, affecting vaccine efficacy and antibody durability [

92,

93]. Adequate rest, effective stress management, regular physical activity, avoidance of smoking, moderation in alcohol consumption, and minimal exposure to environmental pollutants are crucial factors that further influence the immune system's functionality. Understand these interactions is critical for developing strategies for enhancing immune resilience and improving vaccine outcomes.

4. Conclusions

Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases highlight the importance of antibodies in the immune response, acting as a double-edge sword with both protective and pathogenic functions. As reviewed, numerous factors affect the overall antibody functions and understanding these mechanisms is required for the development of effective antibody-based immunotherapies and vaccines.

Antibodies hold promise as immunotherapeutics against infectious diseases, but to fully unleashed their potential, we would need to better understand how to design and engineer them to promote protective capabilities, while reducing pathogenic effects. To achieve these, there is a need to further develop nanobodies [

94], design bioengineered antibody fragments [

95], and improve vaccine development, such as designing mosaic nanoparticles for enhanced protective immune responses [

96]. Additionally, future advancements in antibody development should leverage artificial intelligence and machine learning to optimize design, discovery, and engineering of novel antibodies [

97]. Advancements in this area will improve our readiness to combat emerging health threats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.-M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, J.H., F.-M.L. and Y.-W.K.; visualization, F.-M.L. and Y.-W.K.; supervision, F.-M.L.; project administration, F.-M.L.; funding acquisition, F.-M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Singapore National Medical Council (NMRC), Open-Fund Young Investigator Research Grant (OF- YIRG) (Grant No. MOH-001259-01), the TRipartite Programme in Infectious Diseases Research For New Discoveries and TreatmENT (TRIDENT) (Grant No. TP24_P1), and core funds through the Biomedical Research Council (BMRC), A*STAR, Central Research Fund (CRF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this review article.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Singapore National Medical Council (NMRC), Open-Fund Young Investigator Research Grant (OF- YIRG) (Grant No. MOH-001259-01), the TRipartite Pro-gramme in Infectious Diseases Research For New Discoveries and TreatmENT (TRIDENT) (Grant No. TP24_P1), and core funds through the Biomedical Research Council (BMRC), A*STAR, Central Research Fund (CRF, UIBR) Award.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADCC |

Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity |

| ADCP |

Antibody-Dependent Cellular Phagocytosis |

| ADE |

Antibody-Dependent Enhancement |

| ANO2 |

Anoctamin-2 |

| APTT |

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time |

| BGLF5 |

EBV Ribonuclease Protein |

| CD107 |

Lysosomal-Associated Membrane Protein 1 |

| CD16a |

FcγRIIIa |

| CD16b |

FcγRIIIb |

| CD32a |

FcγRIIa |

| CD32b |

FcγRIIb |

| CD32c |

FcγRIIc |

| CD64 |

FcγRI |

| CMV |

Cytomegalovirus |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| CRYAB |

Alpha-B Crystallin |

| CSR |

Class Switching Recombination |

| CXCR3 |

C-X-C Chemokine Receptor Type 3 |

| DENV |

Dengue Virus |

| dsDNA |

Double-Stranded DNA |

| EBNA1 |

Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigen 1 |

| EBV |

Epstein-Barr Virus |

| FcγR |

Fc Gamma Receptor |

| FcγRI |

Fc Gamma Receptor I |

| FcγRIIa |

Fc Gamma Receptor IIa |

| FcγRIIb |

Fc Gamma Receptor IIb |

| FcγRIIc |

Fc Gamma Receptor IIc |

| FcγRIIIa |

Fc Gamma Receptor IIIa |

| FcγRIIIb |

Fc Gamma Receptor IIIb |

| FcRs |

Fc Receptors |

| GBS |

Guillain-Barré Syndrome |

| GlialCAM |

Glial Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| gp120 |

Glycoprotein 120 |

| HA |

Hemagglutinin |

| HA2 |

Hemagglutinin Subunit 2 |

| HCV |

Hepatitis C Virus |

| HCMV |

Human Cytomegalovirus |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HLA |

Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| HSV |

Herpes Simplex Virus |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon-Gamma |

| IgA |

Immunoglobulin A |

| IgD |

Immunoglobulin D |

| IgE |

Immunoglobulin E |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| IgM |

Immunoglobulin M |

| ITAM |

Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-Based Activation Motif |

| ITIM |

Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-Based Inhibitory Motif |

| JEV |

Japanese Encephalitis Virus |

| MBP |

Myelin Basic Protein |

| MBCs |

Memory B Cells |

| MIS-C |

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children |

| MS |

Multiple Sclerosis |

| NNAbs |

Non-Neutralizing Antibodies |

| NK |

Natural Killer |

| PD-1 |

Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PT |

Prothrombin Time |

| RA |

Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| RSV |

Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SHM |

Somatic Hypermutation |

| SLE |

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

| SNX8 |

Sorting Nexin 8 |

| STAT1 |

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1 |

| TIGIT |

T Cell Immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM Domains |

| WNV |

West Nile Virus |

| ZIKV |

Zika Virus |

References

- Bonilla, F.A.; Oettgen, H.C. Adaptive immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010, 125, S33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.K. B Cells. In Basics of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant; Springer: 2023; pp. 87-120.

- Stavnezer, J.; Schrader, C.E. IgH chain class switch recombination: mechanism and regulation. J Immunol 2014, 193, 5370–5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nothelfer, K.; Sansonetti, P.J.; Phalipon, A. Pathogen manipulation of B cells: the best defence is a good offence. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doria-Rose, N.A.; Joyce, M.G. Strategies to guide the antibody affinity maturation process. Curr Opin Virol 2015, 11, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, A.J.; Bijker, E.M. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat Rev Immunol 2021, 21, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, L.A. Pathogenic antibodies. Nat Immunol 2019, 20, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.M.; Hwang, Y.C.; Liu, I.J.; Lee, C.C.; Tsai, H.Z.; Li, H.J.; Wu, H.C. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. J Biomed Sci 2020, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slifka, M.K.; Amanna, I.J. Role of Multivalency and Antigenic Threshold in Generating Protective Antibody Responses. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klasse, P.J.; Sattentau, Q.J. Occupancy and mechanism in antibody-mediated neutralization of animal viruses. J Gen Virol 2002, 83, 2091–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantaleo, G.; Correia, B.; Fenwick, C.; Joo, V.S.; Perez, L. Antibodies to combat viral infections: development strategies and progress. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2022, 21, 676–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, D.R. Antiviral neutralizing antibodies: from in vitro to in vivo activity. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klasse, P.J. Neutralization of Virus Infectivity by Antibodies: Old Problems in New Perspectives. Advances in Biology 2014, 2014, 157895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boero, E.; Gorham, R.D., Jr.; Francis, E.A.; Brand, J.; Teng, L.H.; Doorduijn, D.J.; Ruyken, M.; Muts, R.M.; Lehmann, C.; Verschoor, A.; et al. Purified complement C3b triggers phagocytosis and activation of human neutrophils via complement receptor 1. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Smatti, M.K.; Ouhtit, A.; Cyprian, F.S.; Almaslamani, M.A.; Thani, A.A.; Yassine, H.M. Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE) and the role of complement system in disease pathogenesis. Mol Immunol 2022, 152, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricklin, D.; Hajishengallis, G.; Yang, K.; Lambris, J.D. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nature Immunology 2010, 11, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, A.B.; Bonnin, F.A.; López, E.L.; Polack, F.P.; Talarico, L.B. C1q modulation of antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection in human myeloid cell lines is dependent on cell type and antibody specificity. Microbes and Infection 2024, 26, 105378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, A.B.; Talarico, L.B. Role of the complement system in antibody-dependent enhancement of flavivirus infections. Int J Infect Dis 2021, 103, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Dopico, T.; Clatworthy, M.R. IgG and Fcγ Receptors in Intestinal Immunity and Inflammation. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamptey, H.; Bonney, E.Y.; Adu, B.; Kyei, G.B. Are Fc Gamma Receptor Polymorphisms Important in HIV-1 Infection Outcomes and Latent Reservoir Size? Front Immunol 2021, 12, 656894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravetch, J.V.; Bolland, S. IgG fc receptors. Annual review of immunology 2001, 19, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Poel, C.E.; Spaapen, R.M.; van de Winkel, J.G.J.; Leusen, J.H.W. Functional Characteristics of the High Affinity IgG Receptor, FcγRI. The Journal of Immunology 2011, 186, 2699–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargraves, M.M. Discovery of the LE cell and its morphology. Mayo Clin Proc 1969, 44, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waaler, E. On the occurrence of a factor in human serum activating the specific agglutintion of sheep blood corpuscles. 1939. Apmis 2007, 115, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, D.J.; Moran, J.E.; Niall, J.F.; Ryan, G.B. Segmental necrotising glomerulonephritis with antineutrophil antibody: possible arbovirus aetiology? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982, 285, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeling, M.; Pöhnl, M.; Kara, S.; Horstmann, N.; Riemer, C.; Wöhner, M.; Liang, C.; Brückner, C.; Eiring, P.; Werner, A.; et al. Immunoglobulin G-dependent inhibition of inflammatory bone remodeling requires pattern recognition receptor Dectin-1. Immunity 2023, 56, 1046–1063.e1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vattepu, R.; Sneed, S.L.; Anthony, R.M. Sialylation as an Important Regulator of Antibody Function. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 818736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, E.B.; Alter, G. Understanding the role of antibody glycosylation through the lens of severe viral and bacterial diseases. Glycobiology 2020, 30, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Román, V.R.; Murray, J.C.; Weiner, L.M. Chapter 1 - Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC). In Antibody Fc, Ackerman, M.E., Nimmerjahn, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, 2014; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.-X.; Xu, Z.-X.; Yu, L.-F.; Lu, Y.-P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Hou, Y.-B.; Li, J.-N.; Huang, S.; Song, X.; et al. Advances of research of Fc-fusion protein that activate NK cells for tumor immunotherapy. International Immunopharmacology 2022, 109, 108783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, U.; Chakrabarti, A.K.; Kanungo, S.; Dutta, S. Evolutionary dynamics of influenza A/H1N1 virus circulating in India from 2011 to 2021. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2023, 110, 105424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Tan, G.S.; Mullarkey, C.E.; Lee, A.J.; Lam, M.M.W.; Krammer, F.; Henry, C.; Wilson, P.C.; Ashkar, A.A.; Palese, P.; et al. Epitope specificity plays a critical role in regulating antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against influenza A virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 11931–11936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muralidharan, A.; Gravel, C.; Harris, G.; Hashem, A.M.; Zhang, W.; Safronetz, D.; Van Domselaar, G.; Krammer, F.; Sauve, S.; Rosu-Myles, M.; et al. Universal antibody targeting the highly conserved fusion peptide provides cross-protection in mice. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022, 18, 2083428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Taeye, S.W.; Schriek, A.I.; Umotoy, J.C.; Grobben, M.; Burger, J.A.; Sanders, R.W.; Vidarsson, G.; Wuhrer, M.; Falck, D.; Kootstra, N.A.; et al. Afucosylated broadly neutralizing antibodies enhance clearance of HIV-1 infected cells through cell-mediated killing. Communications Biology 2024, 7, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimmerjahn, F. Role of Antibody Glycosylation in Health, Disease, and Therapy. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, B.; Shirafkan, F.; Ripperger, K.; Rattay, K. The Role of Viral Infections in the Onset of Autoimmune Diseases. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastard, P.; Rosen, L.B.; Zhang, Q.; Michailidis, E.; Hoffmann, H.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Dorgham, K.; Philippot, Q.; Rosain, J.; Béziat, V.; et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science 2020, 370, eabd4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-K.; Yeo, K.-J.; Chang, S.-H.; Liao, T.-L.; Chou, C.-H.; Lan, J.-L.; Chang, C.-K.; Chen, D.-Y. The detectable anti-interferon-γ autoantibodies in COVID-19 patients may be associated with disease severity. Virology Journal 2023, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, T.V.; Brewer, R.C.; Ho, P.P.; Moon, J.S.; Jude, K.M.; Fernandez, D.; Fernandes, R.A.; Gomez, A.M.; Nadj, G.S.; Bartley, C.M.; et al. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengvall, K.; Huang, J.; Hellström, C.; Kammer, P.; Biström, M.; Ayoglu, B.; Lima Bomfim, I.; Stridh, P.; Butt, J.; Brenner, N.; et al. Molecular mimicry between Anoctamin 2 and Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 associates with multiple sclerosis risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 16955–16960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, O.G.; Bronge, M.; Tengvall, K.; Akpinar, B.; Nilsson, O.B.; Holmgren, E.; Hessa, T.; Gafvelin, G.; Khademi, M.; Alfredsson, L.; et al. Cross-reactive EBNA1 immunity targets alpha-crystallin B and is associated with multiple sclerosis. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadg3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jog, N.R.; McClain, M.T.; Heinlen, L.D.; Gross, T.; Towner, R.; Guthridge, J.M.; Axtell, R.C.; Pardo, G.; Harley, J.B.; James, J.A. Epstein Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA-1) peptides recognized by adult multiple sclerosis patient sera induce neurologic symptoms in a murine model. J Autoimmun 2020, 106, 102332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodansky, A.; Mettelman, R.C.; Sabatino, J.J., Jr.; Vazquez, S.E.; Chou, J.; Novak, T.; Moffitt, K.L.; Miller, H.S.; Kung, A.F.; Rackaityte, E.; et al. Molecular mimicry in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Nature 2024, 632, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, D.; Du, P. Zika and Dengue Virus Autoimmunity: An Overview of Related Disorders and Their Potential Mechanisms. Rev Med Virol 2025, 35, e70014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao-Lormeau, V.M.; Blake, A.; Mons, S.; Lastère, S.; Roche, C.; Vanhomwegen, J.; Dub, T.; Baudouin, L.; Teissier, A.; Larre, P.; et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet 2016, 387, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisetsky, D.S. Pathogenesis of autoimmune disease. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2023, 19, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Johnson, D.; Adekunle, R.; Heather, H.; Xu, W.; Cong, X.; Wu, X.; Fan, H.; Andersson, L.M.; Robertson, J.; et al. COVID-19 is associated with bystander polyclonal autoreactive B cell activation as reflected by a broad autoantibody production, but none is linked to disease severity. J Med Virol 2023, 95, e28134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregoire, C.; Spinelli, L.; Villazala-Merino, S.; Gil, L.; Holgado, M.P.; Moussa, M.; Dong, C.; Zarubica, A.; Fallet, M.; Navarro, J.M.; et al. Viral infection engenders bona fide and bystander subsets of lung-resident memory B cells through a permissive mechanism. Immunity 2022, 55, 1216–1233.e1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priora, M.; Borrelli, R.; Parisi, S.; Ditto, M.C.; Realmuto, C.; Laganà, A.; Centanaro Di Vittorio, C.; Degiovanni, R.; Peroni, C.L.; Fusaro, E. Autoantibodies and rheumatologic manifestations in hepatitis C virus infection. Biology 2021, 10, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattarnezhad, N.; Kockum, I.; Thomas, O.G.; Liu, Y.; Ho, P.P.; Barrett, A.K.; Comanescu, A.I.; Wijeratne, T.U.; Utz, P.J.; Alfredsson, L.; et al. Antibody reactivity against EBNA1 and GlialCAM differentiates multiple sclerosis patients from healthy controls. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025, 122, e2424986122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, K.; Jacques, S.; Gottlieb, P.; Villars, R.; Benito, M.-E.; Taylor, D.K.; Spatz, L.A. Expression of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1 (EBNA-1) in the mouse can elicit the production of anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm antibodies. Journal of Autoimmunity 2004, 23, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halstead, S.B.; O'Rourke, E.J.; Allison, A.C. Dengue viruses and mononuclear phagocytes. II. Identity of blood and tissue leukocytes supporting in vitro infection. J Exp Med 1977, 146, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, R.; Tripathi, S. Intrinsic ADE: The Dark Side of Antibody Dependent Enhancement During Dengue Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 580096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, J.E.; Bournazos, S. Fc-FcγR interactions during infections: From neutralizing antibodies to antibody-dependent enhancement. Immunological Reviews 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marisa, S.F.; Afsar, N.S.; Sami, C.A.; Hasan, M.I.; Ali, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Mohona, S.Q.; Ahmed, R.U.; Ehsan, A.; Baset, F. Dengue Myocarditis: A Retrospective Study From 2019 to 2023 in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Bangladesh. Cureus 2025, 17, e84371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.B.; Gibbons, R.V.; Thomas, S.J.; Rothman, A.L.; Nisalak, A.; Berkelman, R.L.; Libraty, D.H.; Endy, T.P. Preexisting Japanese encephalitis virus neutralizing antibodies and increased symptomatic dengue illness in a school-based cohort in Thailand. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011, 5, e1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Moi, M.L.; Takeshita, N.; Lim, C.K.; Shiba, H.; Hosono, K.; Saijo, M.; Kurane, I.; Takasaki, T. Japanese encephalitis vaccine-facilitated dengue virus infection-enhancement antibody in adults. BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Tarbe, M.; Zhou, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Q.; Shi, L.; et al. The pre-existing cellular immunity to Japanese encephalitis virus heterotypically protects mice from Zika virus infection. Sci Bull (Beijing) 2020, 65, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, R.; Beesetti, H.; Brown, J.A.; Ahuja, R.; Ramasamy, V.; Shanmugam, R.K.; Poddar, A.; Batra, G.; Krammer, F.; Lim, J.K.; et al. Dengue and Zika virus infections are enhanced by live attenuated dengue vaccine but not by recombinant DSV4 vaccine candidate in mouse models. eBioMedicine 2020, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, H.; Yeh, R.; Watts, D.M.; Mehmetoglu-Gurbuz, T.; Resendes, R.; Parsons, B.; Gonzales, F.; Joshi, A. Enhancement of Zika virus infection by antibodies from West Nile virus seropositive individuals with no history of clinical infection. BMC Immunol 2021, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Cheng, Y.; Ling, R.; Dai, Y.; Huang, B.; Huang, W.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y. Antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus. Int J Infect Dis 2020, 100, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krilov, L.R.; Anderson, L.J.; Marcoux, L.; Bonagura, V.R.; Wedgwood, J.F. Antibody-mediated enhancement of respiratory syncytial virus infection in two monocyte/macrophage cell lines. J Infect Dis 1989, 160, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polack, F.P. Atypical measles and enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease (ERD) made simple. Pediatr Res 2007, 62, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzmina, N.A.; Younan, P.; Gilchuk, P.; Santos, R.I.; Flyak, A.I.; Ilinykh, P.A.; Huang, K.; Lubaki, N.M.; Ramanathan, P.; Crowe, J.E., Jr.; et al. Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Ebola Virus Infection by Human Antibodies Isolated from Survivors. Cell Rep 2018, 24, 1802–1815.e1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lum, F.M.; Couderc, T.; Chia, B.S.; Ong, R.Y.; Her, Z.; Chow, A.; Leo, Y.S.; Kam, Y.W.; Rénia, L.; Lecuit, M.; et al. Antibody-mediated enhancement aggravates chikungunya virus infection and disease severity. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lidbury, B.A.; Mahalingam, S. Specific ablation of antiviral gene expression in macrophages by antibody-dependent enhancement of Ross River virus infection. J Virol 2000, 74, 8376–8381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saboowala, H. Exploring the recent findings on Virally induced Antibody Dependent Enhancement (ADE) and potential Mechanisms leading to this condition. 2022.

- Kotaki, T.; Nagai, Y.; Yamanaka, A.; Konishi, E.; Kameoka, M. Japanese Encephalitis DNA Vaccines with Epitope Modification Reduce the Induction of Cross-Reactive Antibodies against Dengue Virus and Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Dengue Virus Infection. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, M.Z.; Wiehe, K.; Pollara, J. Antibody-Dependent Cellular Phagocytosis in Antiviral Immune Responses. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr, L.M.; Su, B.; Moog, C. Non-Neutralizing Antibodies Directed against HIV and Their Functions. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanella, I.; Degli Antoni, M.; Marchese, V.; Castelli, F.; Quiros-Roldan, E. Non-neutralizing antibodies: Deleterious or propitious during SARS-CoV-2 infection? Int Immunopharmacol 2022, 110, 108943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Kam, Y.-W. Insights from Avian Influenza: A Review of Its Multifaceted Nature and Future Pandemic Preparedness. Viruses 2024, 16, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, D.R.; Poignard, P.; Stanfield, R.L.; Wilson, I.A. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Present New Prospects to Counter Highly Antigenically Diverse Viruses. Science 2012, 337, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Kong, W.; Yang, L.; Ding, Y.; Cui, H. Immunity and Immune Evasion Mechanisms of Epstein-Barr Virus. Viral Immunol 2023, 36, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenks, J.A.; Goodwin, M.L.; Permar, S.R. The roles of host and viral antibody fc receptors in herpes simplex virus (HSV) and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infections and immunity. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crispin, M.; Ward, A.B.; Wilson, I.A. Structure and immune recognition of the HIV glycan shield. Annual review of biophysics 2018, 47, 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.-J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelbrecht, E.; Rodriguez, O.L.; Lees, W.; Vanwinkle, Z.; Shields, K.; Schultze, S.; Gibson, W.S.; Smith, D.R.; Jana, U.; Saha, S.; et al. Germline polymorphism in the immunoglobulin kappa and lambda loci explain variation in the expressed light chain antibody repertoire. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posteraro, B.; Pastorino, R.; Di Giannantonio, P.; Ianuale, C.; Amore, R.; Ricciardi, W.; Boccia, S. The link between genetic variation and variability in vaccine responses: systematic review and meta-analyses. Vaccine 2014, 32, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garretson, T.A.; Liu, J.; Li, S.H.; Scher, G.; Santos, J.J.S.; Hogan, G.; Vieira, M.C.; Furey, C.; Atkinson, R.K.; Ye, N.; et al. Immune history shapes human antibody responses to H5N1 influenza viruses. Nat Med 2025, 31, 1454–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auladell, M.; Phuong, H.V.M.; Mai, L.T.Q.; Tseng, Y.Y.; Carolan, L.; Wilks, S.; Thai, P.Q.; Price, D.; Duong, N.T.; Hang, N.L.K.; et al. Influenza virus infection history shapes antibody responses to influenza vaccination. Nat Med 2022, 28, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; Teo, Q.W.; Lee, C.C.; Liang, W.; Choi, D.; Mao, K.J.; Ardagh, M.R.; Gopal, A.B.; Mehta, A.; Szlembarski, M.; et al. Differential antigenic imprinting effects between influenza H1N1 hemagglutinin and neuraminidase in a mouse model. J Virol 2025, 99, e0169524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigdelou, B.; Sepand, M.R.; Najafikhoshnoo, S.; Negrete, J.A.T.; Sharaf, M.; Ho, J.Q.; Sullivan, I.; Chauhan, P.; Etter, M.; Shekarian, T.; et al. COVID-19 and Preexisting Comorbidities: Risks, Synergies, and Clinical Outcomes. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Fcγ receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nature Reviews Immunology 2008, 8, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Lin, F.; Jiang, Z.; Tan, X.; Lin, X.; Liang, Z.; Xiao, C.; Xia, Y.; Guan, W.; Yang, Z.; et al. The impact of pre-existing influenza antibodies and inflammatory status on the influenza vaccine responses in older adults. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2023, 17, e13172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossouw, C.; Ryan, F.J.; Lynn, D.J. The role of the gut microbiota in regulating responses to vaccination: current knowledge and future directions. Febs j 2025, 292, 1480–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Thaiss, C.A.; Elinav, E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology 2017, 17, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, K.A.; Lim, A.I. Maternal-driven immune education in offspring. Immunological Reviews 2024, 323, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visalli, G.; Laganà, A.; Lo Giudice, D.; Calimeri, S.; Caccamo, D.; Trainito, A.; Di Pietro, A.; Facciolà, A. Towards a Future of Personalized Vaccinology: Study on Individual Variables Influencing the Antibody Response to the COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrynla, X.H.; Bates, T.A.; Trank-Greene, M.; Wahedi, M.; Hinchliff, A.; Curlin, M.E.; Tafesse, F.G. Immune imprinting and vaccine interval determine antibody responses to monovalent XBB.1.5 COVID-19 vaccination. Commun Med (Lond) 2025, 5, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranow, C. Vitamin D and the Immune System. Journal of Investigative Medicine 2011, 59, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSorley, H.J.; Maizels, R.M. Helminth infections and host immune regulation. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012, 25, 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.X.; Chen, J.X.; Wang, L.X.; Sun, J.; Chen, S.H.; Chen, J.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhou, X.N. Profiling B and T cell immune responses to co-infection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and hookworm in humans. Infect Dis Poverty 2015, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, S.S.; Moustafa, D.M.; ElBanna, S.A.; Nour El-Din, H.T.; Attia, A.S. Nanobodies in the fight against infectious diseases: repurposing nature's tiny weapons. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 40, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkalkhoran, S.; Grabowska, W.R.; Kashkoli, H.H.; Mirhassani, R.; Guiliano, D.; Dolphin, C.; Khalili, H. Bioengineering of Antibody Fragments: Challenges and Opportunities. Bioengineering (Basel) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.; Cohen, A.A.; Caldera, L.F.; Keeffe, J.R.; Rorick, A.V.; Adia, Y.M.; Gnanapragasam, P.N.P.; Bjorkman, P.J.; Chakraborty, A.K. Designed mosaic nanoparticles enhance cross-reactive immune responses in mice. Cell 2025, 188, 1036–1050.e1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musnier, A.; Dumet, C.; Mitra, S.; Verdier, A.; Keskes, R.; Chassine, A.; Jullian, Y.; Cortes, M.; Corde, Y.; Omahdi, Z. Applying artificial intelligence to accelerate and de-risk antibody discovery. Frontiers in Drug Discovery 2024, 4, 1339697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).