1. Introduction

Latent heat polynyas, such as Terra Nova Bay (TNB) in the Ross Sea, are sites of intense sea ice production driven by cold katabatic winds descending from the Antarctic continent. The continuous loss of heat from the ocean surface to the cold atmosphere promotes rapid sea ice formation, accompanied by brine rejection, which plays a crucial role in water mass formation and ocean mixing [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Dynamic interactions between wind, waves, and ice within these polynyas contribute to substantial ocean-atmosphere heat exchanges, often exceeding 500 W/m² during winter. This enhanced flux can be attributed to the generation of sea foam and spray by wave breaking, which has been shown to significantly increase heat exchange [

5,

6]. Consequently, this process accelerates ice growth and the associated brine production. At the same time, the presence of ice slows down wave growth and promotes damping of short wind waves, leading to a reduction of wave steepness and thus wave breaking intensity [

7]. Overall, ocean–atmosphere heat exchange, sea ice formation and wind-wave processes in polynyas are a result of several mutual interactions that are only poorly understood and not taken into account in models. A better understanding of the spatial extent of sea foam coverage in areas of sea ice formation is a critical prerequisite for formulating better parametrizations of wave breaking in presence of sea ice and thus for improving estimates of ice production and enhancing the performance of spectral wave and weather models.

The foam generated by breaking waves has been shown to modify the spectral properties of the ocean surface, resulting in enhanced reflectance across the visible (VIS), near-infrared (NIR), and shortwave infrared (SWIR) parts of spectrum [

8,

9]. This facilitates remote detection of whitecaps using optical imagery from photographs, videos (e.g. [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]) and satellite radiometers (e.g. [

15,

16,

17]). It has been demonstrated that foam significantly increases the reflectance of the sea surface due to the strong scattering of light by bubble conglomerates, even if the size of individual whitecaps is smaller than the pixel size of the image [

8,

18]. As a result, the presence of whitecaps not only enables the identification of regions with enhanced wave breaking activity [

19], but can also lead to the misinterpretation of satellite reflectance data—particularly at lower spatial resolutions—when used to assess water quality or sea ice concentration [

20,

21]. Therefore, identifying areas of active wave breaking is crucial not only for improving our understanding of wave dynamics and air-sea interaction processes, but also for ensuring the accurate interpretation of ocean color and sea ice products derived from satellite observations.

In the majority of approaches, whitecaps are detected in high resolution images, acquired from various platforms, using brightness thresholding techniques optimized through analysis of the reflectance contrast between foam and water, often supported by derivative-based metrics [

11,

13,

16,

17]. Most existing studies on whitecap detection and their dynamics have focused on ice-free marine environments. In latent heat polynyas, where active sea ice formation occurs, the presence of frazil ice—consisting of small, randomly oriented ice crystals suspended within the upper ocean layer or floating at the surface—increases the overall brightness of the surface [

22]. This additional optical signal can mimic or obscure the radiative signatures typically associated with whitecaps. Additionally, the optical contrast between foam and water is reduced under low-light conditions typical of polar regions [

23]. Therefore, methods developed and calibrated for open-water conditions may not be directly applicable in ice-affected environments.

To date, the only study that has examined the spatial distribution of whitecaps in a coastal polynya is that of Herman and Bradtke [

7], in which energy dissipation due to whitecapping was simulated using a spectral wave model. The model incorporated spatial information on frazil streaks derived from Sentinel-2 satellite data for selected polynya events. The resulting spatial patterns of wave breaking showed a marked reduction in whitecapping associated with the presence of frazil ice. For one of the polynya cases, model-derived whitecap coverage was compared with estimates obtained from high-resolution WorldView-2 imagery. The high degree of agreement between the two highlights the potential of high-resolution satellite observations as a valuable source of data for calibrating and validating wave models in ice-affected regions. Given that the severe winter conditions prevailing in polar regions significantly limit the feasibility of in situ observations, satellite remote sensing serves as a crucial tool for investigating ocean–ice–atmosphere interactions in these environments.

In the earlier study, preliminary results from our method for detecting breaking waves in high-resolution panchromatic imagery were introduced, although the method was applied under a limited range of wave development conditions and without a full discussion of the methodology. Building on this previously applied approach, and motivated by the consistency observed between modelled and satellite-derived whitecap coverage, the present study provides a comprehensive description, rationale, and performance assessment of the detection method under a broader range of conditions. The approach takes advantage of specific lighting conditions—namely, low solar elevation and the alignment of sunlight with the dominant wind direction—which cause steep waves within frazil streaks to cast visible shadows, allowing them to be identified in the imagery. Using additional fragments of the same WorldView-2 (WV2) panchromatic image and multispectral data, this study expands the spatial and environmental context of the analysis, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of the detection algorithm’s performance across varying wind, ice, and fetch conditions. We compare algorithm performance using alternative contrast metrics and evaluate the robustness and limitations of the proposed approach. Finally, we discuss the potential implications of unresolved subpixel-scale wave activity on reflectance values observed at medium spatial resolutions.

4. Discussion

This study discusses a method for detecting wave breakers in ice-affected environment and applies it to investigate the spatial variability of wave breaking intensity in a coastal polynya, using high-resolution optical imagery. The use of optical satellite data in polar regions is often constrained by low solar elevation and frequent cloud cover. However, we show that the availability of very high spatial resolution imagery (on the order of tens of centimeters) enables the extraction of valuable information even from single scenes. These snapshots provide unique insights into poorly understood processes such as wave development and wave-ice interactions under conditions of strong wind forcing and limited fetch [

7]. Mapping the spatial distribution of whitecaps between frazil ice streaks also facilitates the evaluation of their potential impact on surface reflectance at different spatial resolutions—an important consideration for applications such as the automated detection of frazil ice streaks [

28] or the retrieval of bio-optical properties from ocean color data [

21].

The proposed detection algorithm takes advantage of specific illumination conditions, i.e. the low solar elevation and the alignment of sunlight with the dominant wave propagation direction. These conditions enhance the visibility of steep wave features through shadowing effects, especially within frazil streaks. Such lighting scenarios are typical for Terra Nova Bay during September and October between 19:00 and 22:00 UTC, when visible-light imaging becomes feasible while winter conditions persist and the polynya remains intermittently open. The algorithm employs a directional filter to derive a contrast index, specifically designed to minimize false detections of frazil ice at streak boundaries being misclassified as breaking wave crests. Compared to Haralick's general curvature model, used successfully with Sentinel-2 data for ice-free conditions [

17], the proposed filter demonstrates improved robustness and reduced sensitivity to image noise. When using the HGC-based contrast index, the number of false detections along frazil streak boundaries is considerably higher, requiring additional object filtering based on a priori knowledge of wave propagation direction. However, even with wave direction constraints applied, such filtering does not fully eliminate false positives—especially in areas where frazil streaks are discontinuous or have irregular boundaries. In contrast, the directional filter inherently accounts for the dominant wave direction, which simplifies the overall detection process and reduces the need for post-processing.

Empirical relationships between whitecap coverage and wind speed reported by numerous researches (see reviews in [

44,

45]) suggest that under very strong winds—approaching 30 m/s, as observed during the analyzed TNBP event—whitecap coverage (

W) would range from 1% to nearly 100%, typically exceeding 10%. However, our results indicate

W values below 4% (see

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), with local increases up to 30% (

Figure 10a) in limited areas. This discrepancy likely results from regional factors unique to coastal polynyas, which differ significantly from conditions in the open ocean or other coastal zones. First, the formation of frazil ice in the water column increases effective viscosity. Second, the fetch in TNB is severely constrained by the coastal topography and the presence of sea ice. These two factors jointly limit wave development and breaking intensity, even under strong wind forcing. These findings are supported by previous observations [

28] and are consistent with results from spectral wave model simulations that incorporate observed frazil coverage and are tailored to the same polynya event [

7].

A comparison between the spatial distribution of whitecap fraction derived from satellite imagery and that obtained from model simulations (see

Figure S5 in Supplementary materials for [

7]) reveals generally consistent patterns. Some discrepancies remain, however, and given the limited understanding of wave breaking physics in both ice-free and ice-affected conditions, it is reasonable to assume that these discrepancies can be attributed both to the limitations of the algorithm developed in this work, and to the limitations of whitecapping parameterizations used in models. It must be also noted that the whitecap fraction cannot be directly obtained from the results of spectral wave model outputs—it is estimated from the simulated wave energy dissipation with highly simplified, empirical formulae that introduce additional uncertainty to the analysis [

7]. On the remote sensing side, the accuracy of satellite-derived whitecap fraction depends on the chosen contrast measure and threshold value.

Sensitivity analysis within the testing subarea (Ca) shows that threshold values between 2 and 3 effectively identify the same prominent wave crests (also visible in the NIR bands). Lowering the threshold leads to a widening of detected crest areas, approximately doubling the total breaker coverage, while introducing only a moderate increase in misclassifications of features that deviate from the direction of the wave crest. The lack of reliable validation data for whitecap fraction under ice-affected conditions limits our ability to adequately calibrate the proposed algorithm. For this reason, no calibration of the proposed algorithm against model outputs, or vice versa, was performed; instead, the comparison was used solely to evaluate the plausibility of spatial patterns in both datasets.

It should also be noted that the proposed algorithm tends to underestimate whitecap coverage in open water and may overestimate it within frazil ice bands. In open water, this underestimation stems from the algorithm’s limited ability to detect whitecaps that form on short waves obscured by adjacent long and steep waves. In such cases, insufficient illumination in shaded areas of dark water prevents these features from being detected. Additionally, the imposed minimum object size (requiring at least three contiguous pixels to be classified as a potential breaker) may lead to underdetection in areas of open-water dominated by short waves. Conversely, in wide frazil streaks, the algorithm may overstate whitecap presence, because it identifies all steep wave crests exhibiting strong brightness and associated shadows as breakers, even if they do not correspond to actual breaking events. Furthermore, in areas undergoing ice transformation, where image texture changes abruptly, the algorithm may generate numerous false positives. Such areas should be identified beforehand and excluded from the analysis.

Despite the limitations discussed above, the method reliably captures spatial variability in whitecaps coverage in response to changing environmental conditions. For example, it reflects suppression of wave breaking with increasing frazil ice concentration, and a general increase in breaker activity with stronger wind forcing and longer fetch. The satellite-derived whitecap patterns also reveal less intuitive phenomena, such as intensified breaker activity in the northern subarea, where relatively weaker winds act over shorter distances (

Figure 8 and

Figure S6). This pattern is also present in model outputs [

7] and highlights the significant role of frazil ice distribution and fetch geometry in modulating wave dynamics. Additionally, thanks to the high spatial resolution of the WorldView-2 imagery (0.5-2.0 m), the proposed method allows for the identification of localized effects, such as wind sheltering by icebergs or coastal topography, on breaker distribution. These factors typically remain unresolved in simulations based on wind fields derived from coarser-resolution atmospheric models such as AMPS. Collectively, these observations underscore the complexity of wave–ice interactions in coastal polynyas and demonstrate that whitecap coverage (

W) cannot be adequately parameterized as a simple function of wind speed alone. Instead,

W in ice-affected environments depends on a combination of factors, including frazil ice concentration, fetch geometry, wave directionality, and small-scale topographic effects. This highlights the need for more sophisticated approaches when representing whitecapping processes in such regions.

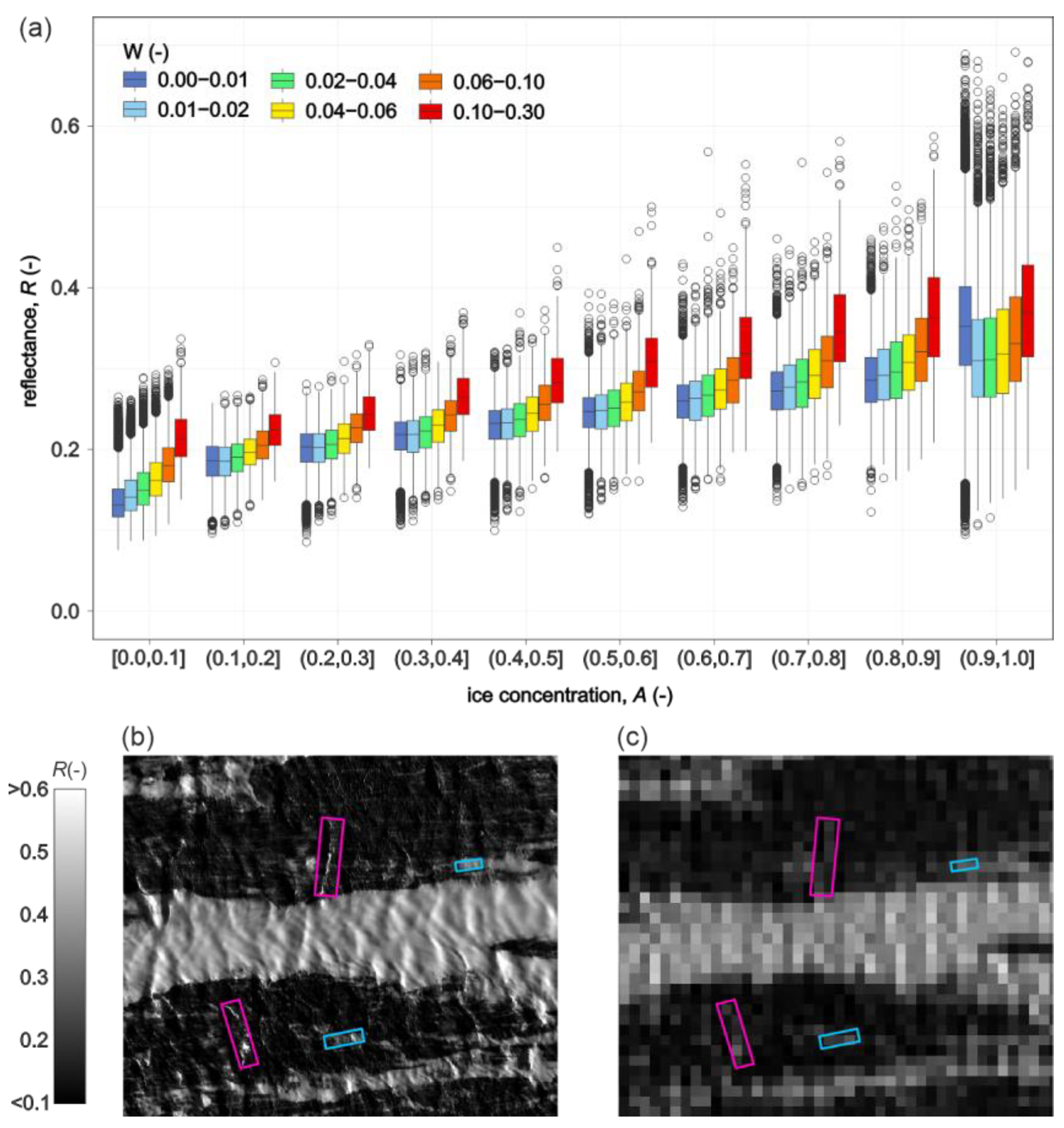

In ice-free oceanic waters, the reflectance of fresh whitecaps can exceed that of the background sea surface by up to an order of magnitude in the visible spectrum [

8,

9,

20]. This necessitates correction when reflectance is used, for example, to estimate biological productivity or derive surface properties. Similar optical effects must be considered in ice-affected environments such as coastal polynyas, where both sea ice and whitecaps co-exist and contribute to the observed signal. An analysis of reflectance values averaged over aggregated pixel sizes comparable to the spatial resolution of sensors like Landsat or Sentinel-2 reveals a consistent increase in mean reflectance with rising whitecap fraction, regardless of frazil coverage. Importantly, pixels partially covered by frazil ice and exhibiting elevated local whitecap fraction (

W > 0.1) show reflectance levels comparable to those observed for a 10–20% increase in ice coverage alone. As a result, pixels with limited ice cover but substantial whitecap presence may display reflectance values indistinguishable from those of genuinely ice-covered areas, thereby complicating automated sea ice classification. This is particularly relevant for algorithms that rely solely on broadband reflectance thresholds or unsupervised clustering, as they may produce false positives and introduce spatial biases in ice extent estimates or frazil streak tracking.

In summary, the results presented in this study confirm the utility of the proposed detection algorithm for mapping spatial variations in whitecap coverage under complex, ice-affected conditions, despite certain limitations and the absence of precise uncertainty estimates. The observed patterns, consistent with expected responses to changes in wind forcing, ice concentration, and fetch, support the robustness of the method. Although the algorithm was developed and tested using a single satellite scene acquired under specific illumination conditions, such conditions recur daily during the late winter period in Terra Nova Bay, making more systematic analyses feasible. This opens opportunities for investigating the dependence of whitecap coverage on multiple environmental factors, which may lead to improved parameterizations in spectral wave models [

7]. The insights gained using proposed algorithm are also likely relevant to other coastal polynyas, where lighting conditions do not support application of presented method. Furthermore, the presented approach could serve as a basis to collect datasets for training more advanced detection algorithms capable of overcoming current limitations, for instance, by inferring the presence of wave breaking features that remain hidden in shadowed regions of the water surface.

Figure 1.

(a) The Terra Nova Bay Polynya on satellite image (true color composite) gathered by Sentinel-2 on September 19, 2019 at 21:00 (Copernicus Sentinel data 2019); outlines of the analyzed subsets of high resolution data collected by WorldView-2 satellite are marked with the orange rectangles. (b) Wind conditions (direction denoted by arrows) simulated by the Antarctic Mesoscale Prediction System for the polynya event (9-hour forecasts from 12 UTC valid for 21 UTC).

Figure 1.

(a) The Terra Nova Bay Polynya on satellite image (true color composite) gathered by Sentinel-2 on September 19, 2019 at 21:00 (Copernicus Sentinel data 2019); outlines of the analyzed subsets of high resolution data collected by WorldView-2 satellite are marked with the orange rectangles. (b) Wind conditions (direction denoted by arrows) simulated by the Antarctic Mesoscale Prediction System for the polynya event (9-hour forecasts from 12 UTC valid for 21 UTC).

Figure 2.

WorldView-2 images (imagery © 2019 Maxar Technologies) in spectral bands: PAN (a), NIR1 (b) and NIR2 (c) for subset Ca and their enlarged parts.

Figure 2.

WorldView-2 images (imagery © 2019 Maxar Technologies) in spectral bands: PAN (a), NIR1 (b) and NIR2 (c) for subset Ca and their enlarged parts.

Figure 3.

Overall scheme of WV2 data processing.

Figure 3.

Overall scheme of WV2 data processing.

Figure 4.

Kernel of the convolutional filter used to highlight the boundaries of potential breakers using lighting conditions.

Figure 4.

Kernel of the convolutional filter used to highlight the boundaries of potential breakers using lighting conditions.

Figure 5.

Characteristics of objects detected as potential breakers using panchromatic image and both measures of contrast with different threshold values. Dashed lines indicate algorithm version without bilateral filtration.

Figure 5.

Characteristics of objects detected as potential breakers using panchromatic image and both measures of contrast with different threshold values. Dashed lines indicate algorithm version without bilateral filtration.

Figure 6.

Relationship between whitecap coverage (W) in 200 × 200 m blocks, derived using both measures of contrast with threshold value 3.0 without (a) and with (b) additional filtration of objects which orientation closely aligned with the wave propagation direction (deviation less than 45°), recognized as false alarms; colors show concentration of ice (A). Dashed lines indicate identity function.

Figure 6.

Relationship between whitecap coverage (W) in 200 × 200 m blocks, derived using both measures of contrast with threshold value 3.0 without (a) and with (b) additional filtration of objects which orientation closely aligned with the wave propagation direction (deviation less than 45°), recognized as false alarms; colors show concentration of ice (A). Dashed lines indicate identity function.

Figure 7.

Relationship between whitecap fraction (W) and sea ice concentration (A) in 200 × 200 m blocks for the four analyzed subareas (a); colors show wind speed (U10). In subarea N, two groups of outliers are highlighted with ellipses: the red ellipse indicates possible overestimation due to changes in image texture over ice (illustrated in panels b and c), while the blue ellipse corresponds to low W values in open-water zones caused by sheltering effect (examples in panels d and e). Panels (b–e) show zoomed fragments of the panchromatic image with contours of detected breakers outlined in magenta. The image beneath shows the full extent of subarea N with the locations of the examples marked.

Figure 7.

Relationship between whitecap fraction (W) and sea ice concentration (A) in 200 × 200 m blocks for the four analyzed subareas (a); colors show wind speed (U10). In subarea N, two groups of outliers are highlighted with ellipses: the red ellipse indicates possible overestimation due to changes in image texture over ice (illustrated in panels b and c), while the blue ellipse corresponds to low W values in open-water zones caused by sheltering effect (examples in panels d and e). Panels (b–e) show zoomed fragments of the panchromatic image with contours of detected breakers outlined in magenta. The image beneath shows the full extent of subarea N with the locations of the examples marked.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of whitecap coverage (W) in the northermost N (a) and southernmost S (b) subareas. Grey rectangles indicate location of panchromatic image spots (shown in panels c and d), presenting whitecaps in open water areas in different wind and fetch conditions: (c) subset N, wind speed 24.5 m/s (d) subset S wind speed 32.2 m/s.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of whitecap coverage (W) in the northermost N (a) and southernmost S (b) subareas. Grey rectangles indicate location of panchromatic image spots (shown in panels c and d), presenting whitecaps in open water areas in different wind and fetch conditions: (c) subset N, wind speed 24.5 m/s (d) subset S wind speed 32.2 m/s.

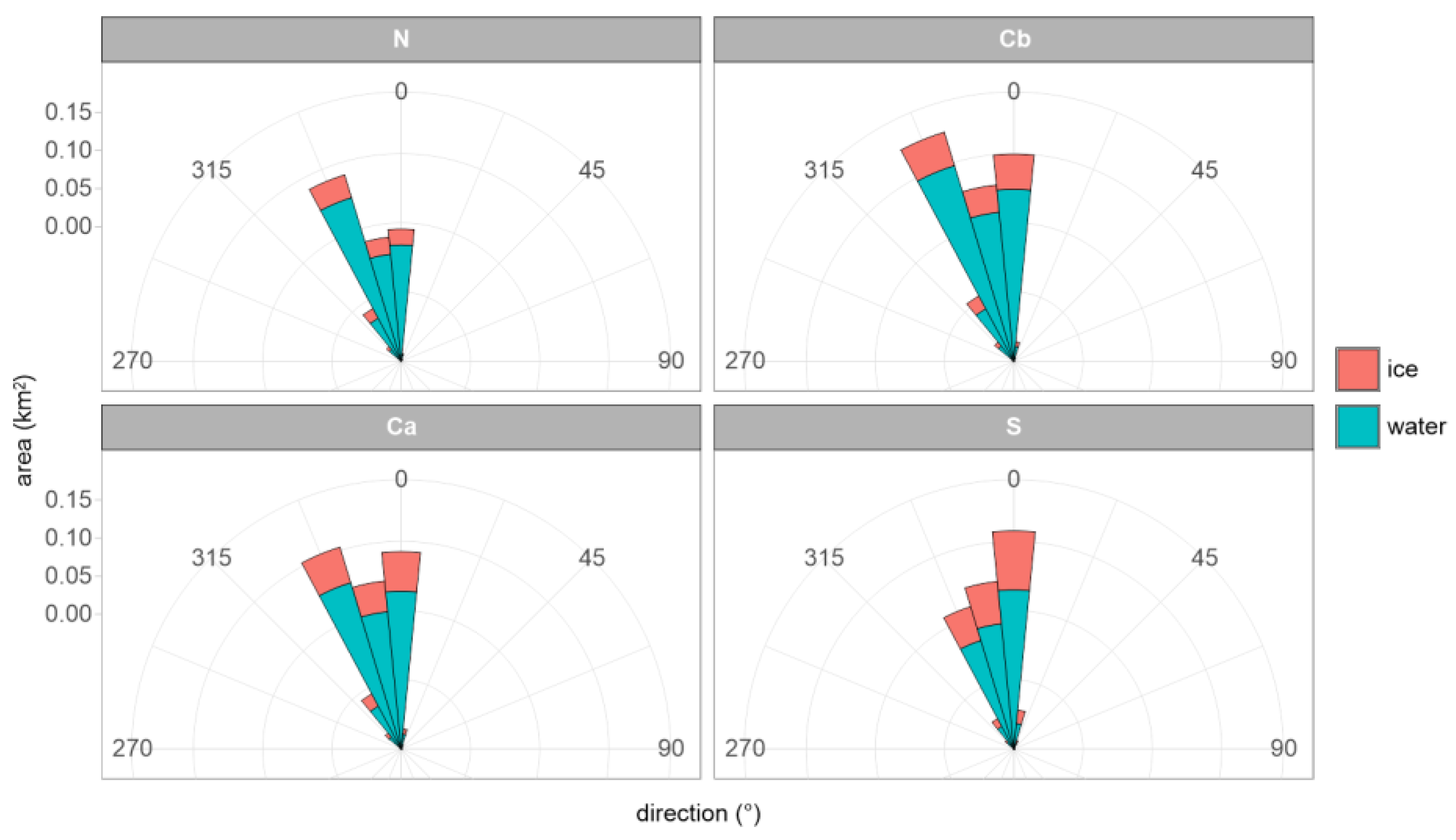

Figure 9.

Statistical distribution of crest orientation for individual objects identified as breakers in frazil ice streaks (red) and in the open water between them (blue). Orientation bins are defined in 12.5° intervals relative to true north. Frequencies are weighted by whitecaps surface area.

Figure 9.

Statistical distribution of crest orientation for individual objects identified as breakers in frazil ice streaks (red) and in the open water between them (blue). Orientation bins are defined in 12.5° intervals relative to true north. Frequencies are weighted by whitecaps surface area.

Figure 10.

(a) Box plots showing statistics of reflectance averaged over 15 × 15 m blocks (simulating lower-resolution satellite data) for different ice concentrations (A) and whitecap coverage (W). Circles, whiskers, boxes, and horizontal lines indicate, respectively: outliers, the range between the minimum and maximum non-outlier values, the interquartile range (IQR), and the median. (b-c) Subset of the WV2 panchromatic image at native resolution (b) and resampled to 15 m resolution (c). Polygons mark large whitecaps (magenta) and narrow frazil streaks (blue) which have a comparable effect on reflectance at coarser resolution.

Figure 10.

(a) Box plots showing statistics of reflectance averaged over 15 × 15 m blocks (simulating lower-resolution satellite data) for different ice concentrations (A) and whitecap coverage (W). Circles, whiskers, boxes, and horizontal lines indicate, respectively: outliers, the range between the minimum and maximum non-outlier values, the interquartile range (IQR), and the median. (b-c) Subset of the WV2 panchromatic image at native resolution (b) and resampled to 15 m resolution (c). Polygons mark large whitecaps (magenta) and narrow frazil streaks (blue) which have a comparable effect on reflectance at coarser resolution.