Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Machine learning techniques applied in bird detection are categorised and mapped, highlighting trends in lightweight models and edge compatibility.

- Dataset types, collection methods, and preprocessing techniques used in training detection models are reviewed.

- IoT architectures and communication protocols are evaluated, identifying strengths and limitations in cloud-based systems.

- An analysis of bird repellence methods and their integration with intelligent detection systems is provided.

- Key challenges are identified, and future research directions for building scalable, adaptive bird management systems are proposed

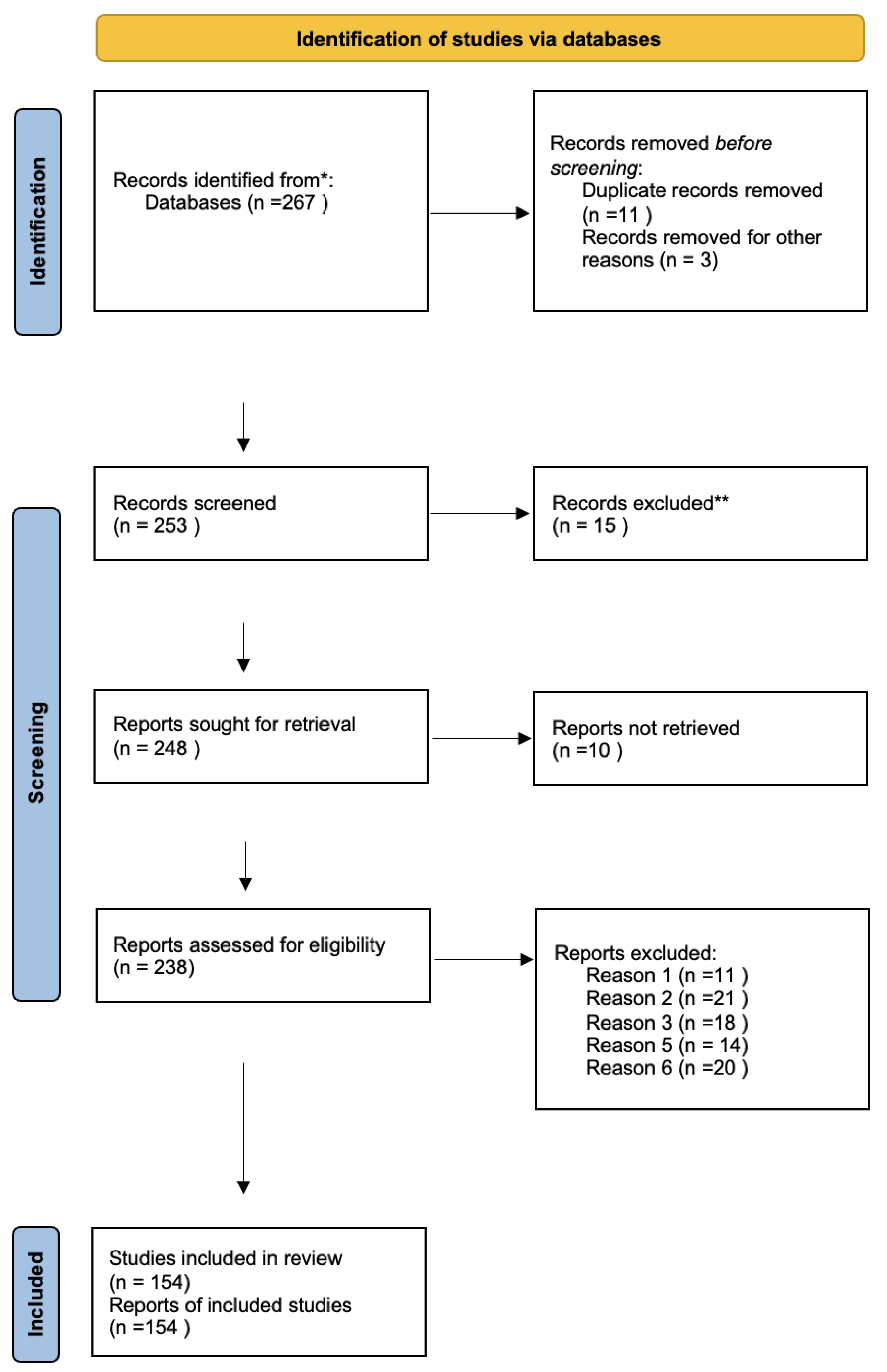

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification

- "Machine Learning + Bird Detection"

- "Machine Learning + Bird Repellence"

- "Computer Vision + Bird Detection"

- “Acoustic Bird Detection”

- "IoT + Bird Repellence"

- "Artificial Intelligence + Bird Detection + Repellence"

2.2. Screening

2.3. Eligibility

2.4. Inclusion

3. Computer Vision-Based Detection

3.1. Datasets

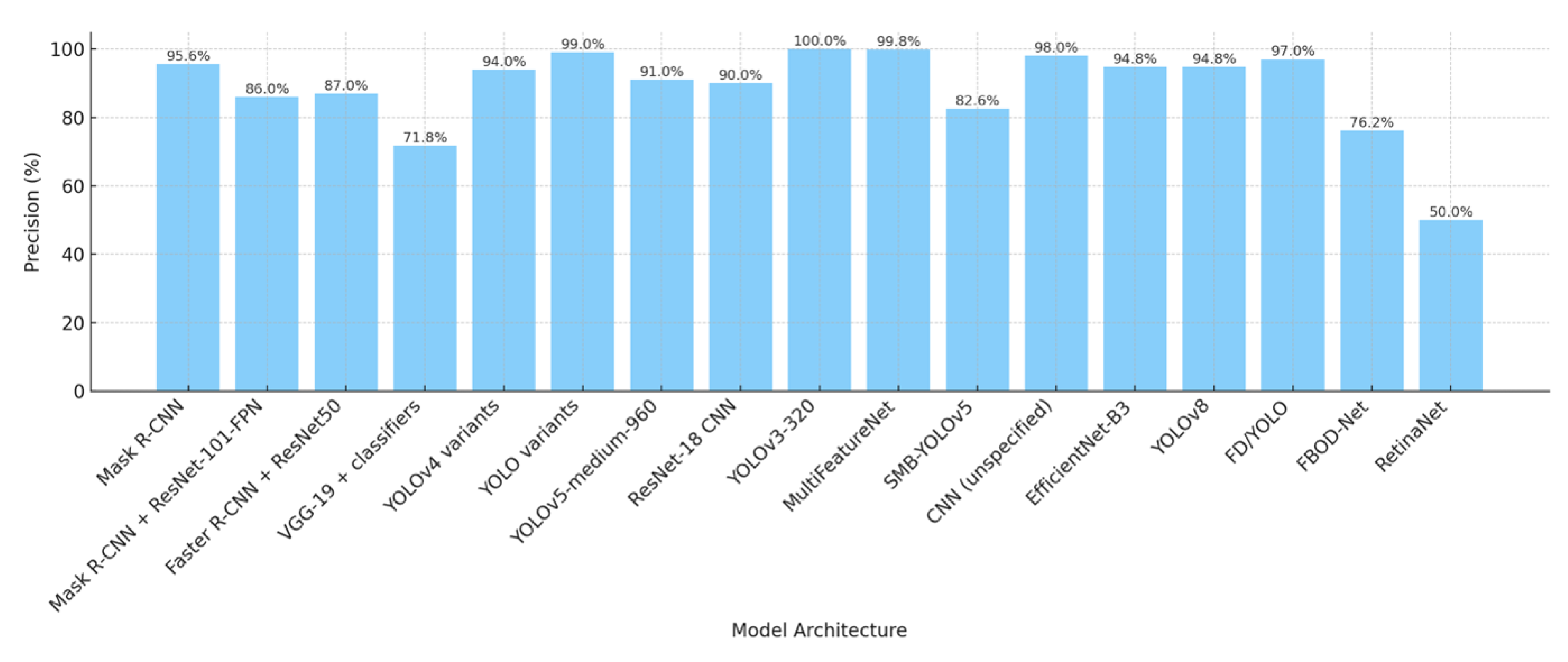

3.2. Machine Learning Models

4. Acoustic-Based Detection

| Study Focus | Hardware Used | Approach | Detection Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of BirdNET for detecting two bird species [78] | AudioMoth | BirdNET (CNN-based) | Precision: 92.6% (Coal Tit), 87.8% (Short-toed Treecreeper) |

| Bird sound Classification [48] | No mention found | Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | Accuracy: 74% |

| Vineyard protection from birds [79] | Raspberry Pi 3B, microphone | Two-phase: SVM and CNN | Accuracy: 96% |

| BirdCLEF 2021 challenge [80] | No mention found | CNN-based ensemble | F1 score: 0.6780 |

| Birdsong detection on IoT devices [81] | STM32 Nucleo H743ZI2 MCU | ToucaNet and BarbNet (CNN-based) | AUC: 0.925 (ToucaNet), 0.853 (BarbNet) |

| Acoustic bird repellent system [82] | Arduino Nano 33 BLE, microphone | DenseNet201 (CNN) | Accuracy: 92.54% |

| Avian pest deterrence [83] | Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense, XIAO ESP32S3 | Conv1D neural network | Accuracy: 92.99% |

| Bird song recognition on IoT devices [84] | ARM Cortex-M microcontrollers | Various CNN and Transformer models | Accuracy: >90% for best models |

| Avian diversity monitoring [85] | Autonomous Recording Units (ARUs) | BirdNET (ResNet-based) | mAP: 0.791 for single-species recordings |

| Monitoring Eurasian bittern [78] | AudioMoth | BirdNET and Kaleidoscope Pro | Accuracy: 93.7% (BirdNET), 98.4% (Kaleidoscope Pro) |

| Passive acoustic monitoring of bird communities [86] | SM4 Wildlife Acoustics ARUs | CNN (ResNet50) | mAP: 0.97 |

| Detecting novel bird species and individuals [87] | No mention found | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | FPI: 1.6%, FNI: 0.9% (species detection) |

| Birdcall identification on embedded devices [77] | Jetson Nano | CNN-based multi-model network | Accuracy: 84.9% |

| Endangered birds monitoring [88] | ARM Cortex M3 micro-controller | Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) | No mention found |

| Bird species monitoring and song classification [49] | 5G IoT-based system, ESP32-S3 MCUs | Various CNNs (EfficientNet, MobileNet) | Accuracy: >70% for best models |

| Evaluation of acoustic recorders and BirdNET [89] | AudioMoth, Swift Recorder, SM3BAT, SM Mini | BirdNET (not specified) | Accuracy: 96% |

| Bird audio detection [90] | No mention found | Lightweight CNN | Accuracy: 86.42% |

| Acoustic monitoring of avian species [91] | AviEar (IoT-based wireless sensor node) | No clear mention found | Precision: 99.6%, Recall: 95% |

5. Connectivity

- Wi-Fi - This enables high-speed data transfer and has been applied in several studies. However, it has a limited range and high power consumption, making it unsuitable for large-scale, battery-powered networks.

- LoRa (Long Range, Low Power) – This has also been used and is ideal for IoT applications in agriculture and environmental monitoring due to its long range and low power needs. However, the low data rate make it less suitable for applications requiring high-resolution image or video transmission.

- Cellular Networks (4G/LTE, 5G) – This has been used to provides seamless connectivity, especially for mobile IoT devices. However, high cost and energy consumption make it impractical for many large-scale IoT applications.

- Zigbee - Very low power consumption, low cost, well-suited for mesh networks in local IoT setups. Shorter range compared to LoRa and Cellular, not suitable for high-data applications like images or videos

6. IoT Implementation Architectures

6.1. Cloud-Based Architectures

6.2. Edge Computing

- Microcontrollers (ESP32, ATmega328, etc.) – These low-power devices are ideal for lightweight processing tasks but struggle with deep-learning models due to limited computational capacity [97].

- Single-board computers (Raspberry Pi, Jetson boards) – More powerful than microcontrollers and are commonly used in edge-based implementations, these devices can handle more complex computations but consume more power and are more costly [30].

- FPGA-based solutions – While highly efficient for real-time processing, FPGA implementations are less common due to their complexity and cost. Deploying machine learning models at the edge requires balancing of performance, power efficiency, and resource constraints. The reviewed studies explored several optimisation strategies:

- Lightweight models – MobileNet and optimized YOLO variants are frequently used due to their efficiency in object detection tasks.

- Transfer learning – Adapting pre-trained models allows for reduced computational overhead while maintaining high accuracy [98].

- Model compression – Techniques such as pruning and quantization help shrink models to fit within resource-limited devices [99].

- Pruning and quantization – Reducing model complexity without significantly impacting accuracy.

- Power-saving techniques – Using sleep modes and efficient RAM allocation in microcontrollers.

- Local data processing – Minimizing the need for network communication to save power.

7. Bird Repellence Methods

8. Discussion

8.1. Challenges in Bird Detection and Repellence Systems

8.1.1. Detecting small and distant birds with high accuracy:

8.1.2. Environmental Variability and Real-time Adaptation:

8.1.3. Energy Efficiency and Computational Constraints on Edge Devices:

8.1.4. Managing Data Collection, Storage, and Transmission:

8.1.5. Reducing False Positives and Enhancing Species-Specific Identification:

8.2. Opportunities with AI in Bird Detection

8.2.1. Deploying Low-Power, AI-Driven Edge Computing Solutions:

8.2.2. Multi-Sensor Fusion for Enhanced Detection Accuracy:

8.2.3. Adaptive AI Models for Self-Learning and Context Awareness:

8.2.4. Energy-Efficient Model Optimization for Scalability:

8.3. Future Research Directions

- Developing ultra-lightweight, high-accuracy AI models – Improving TinyML capabilities to maintain performance while reducing computational demands.

- Enhancing automated data collection and labelling – Creating standardized, open-source datasets for training and benchmarking bird detection models.

- Designing self-learning AI models – Implementing on-device adaptation to reduce reliance on cloud retraining and improve real-time responsiveness.

- Exploring AI-driven, species-specific repellence techniques – Using behavior-based deterrence strategies that dynamically adapt to different bird species.

- Integrating bird detection into broader smart agriculture and urban management systems – Ensuring AI-driven bird monitoring complements existing environmental and precision farming technologies.

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| ARU | Autonomous Recording Unit |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| VAE | Variational Autoencoder |

| DTW | Dynamic Time Warping |

| MCU | Microcontroller Unit |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| TinyML | Tiny Machine Learning |

| Wi-Fi | Wireless Fidelity |

| LoRa | Long Range |

| BLE | Bluetooth Low Energy |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

References

- M. Tech Scholar and A. Professor, “Artificial Intelligence Based Birds and Animal Detection and Alert System,” 2022. [Online]. Available: www.ijcrt.org.

- D. Mpouziotas, P. Karvelis, and C. Stylios, “Advanced Computer Vision Methods for Tracking Wild Birds from Drone Footage,” Drones, vol. 8, no. 6, Jun. 2024, 10.3390/drones8060259.

- K. Shim, A. Barczak, N. Reyes, and N. Ahmed, “Small mammals and bird detection using IoT devices,” in Int. Conf. Image and Vision Computing New Zealand, IEEE, 2021, 10.1109/IVCNZ54163.2021.9653430.

- A. Aumen, G. Gagliardi, C. Kinkead, V. Nguyen, K. Smith, and J. Gershenson, “Influence of the Red-Billed Quelea Bird on Rice Farming in the Kisumu, Kenya Region,” in IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conf., pp. 64–71, Oct. 2024, 10.1109/GHTC62424.2024.10771535.

- C. Huang, K. Zhou, Y. Huang, P. Fan, Y. Liu, and T. M. Lee, “Insights into the coexistence of birds and humans in cropland through meta-analyses of bird exclosure studies, crop loss mitigation experiments, and social surveys,” PLoS Biol., vol. 21, no. 7, Jul. 2023, 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002166.

- A. Mirugwe, J. Nyirenda, and E. Dufourq, “EPiC Series in Computing Automating Bird Detection Based on Webcam Captured Images using Deep Learning,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://news.mongabay.com/2017.

- A. Pruteanu, N. Vanghele, D. Cujbescu, M. Nitu, and I. Gageanu, “Review of Effectiveness of Visual and Auditory Bird Scaring Techniques in Agriculture,” in Eng. for Rural Development, vol. 22, pp. 275–281, 2023, 10.22616/ERDEV.2023.22.TF056.

- H. Agossou, E. P. S. Assede, P. J. Dossou, and S. H. Biaou, “Effect of bird scaring methods on crop productivity and avian diversity conservation in agroecosystems of Benin,” Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci., vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 527–542, Jul. 2022, 10.4314/IJBCS.V16I2.2.

- H. González, A. Vera, and D. Valle, “Design of an Artificial Vision System to Detect and Control the Presence of Black Vultures at Airfields,” in Proc. Int. Conf. on Augmented Intelligence and Sustainable Systems (ICAISS), IEEE, pp. 589–597, 2022, 10.1109/ICAISS55157.2022.10010861.

- A. Albanese and D. Brunelli, “Pest detection for Precision Agriculture based on IoT Machine Learning application.” Unpublished.

- A. S. Pillai, S. U. Ajay Sathvik, N. B. Sai Shibu, and A. R. Devidas, “Monitoring Urban Wetland Bird Migrations using IoT and ML Techniques,” in IEEE 9th Int. Conf. for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), 2024, 10.1109/I2CT61223.2024.10543277.

- B. Cardoso, C. Silva, J. Costa, and B. Ribeiro, “Internet of Things Meets Computer Vision to Make an Intelligent Pest Monitoring Network,” Appl. Sci. (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 18, Sep. 2022, 10.3390/app12189397.

- L. Bruggemann, B. Schutz, and N. Aschenbruck, “Ornithology meets the IoT: Automatic Bird Identification, Census, and Localization,” in 7th IEEE World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), pp. 765–770, Jun. 2021, 10.1109/WF-IoT51360.2021.9595401.

- M. Yuliana, I. C. Fitrah, and M. Z. S. Hadi, “Intelligent Bird Detection and Repeller System in Rice Field Based on Internet of Things,” in IEEE Int. Conf. on Communication, Networks and Satellite (COMNETSAT), pp. 615–621, 2023, 10.1109/COMNETSAT59769.2023.10420717.

- D. Mpouziotas, P. Karvelis, and C. Stylios, “Advanced Computer Vision Methods for Tracking Wild Birds from Drone Footage,” Drones, vol. 8, no. 6, Jun. 2024, 10.3390/drones8060259.

- S. Sethu Selvi, S. Pavithraa, R. Dharini, and E. Chaitra, “A Deep Learning Approach to Classify Drones and Birds,” in MysuruCon 2022 - IEEE 2nd Mysore Sub Section Int. Conf., 2022, 10.1109/MysuruCon55714.2022.9972589.

- Y. C. Chen, J. F. Chu, K. W. Hsieh, T. H. Lin, P. Z. Chang, and Y. C. Tsai, “Automatic wild bird repellent system that is based on deep-learning-based wild bird detection and integrated with a laser rotation mechanism,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, Dec. 2024, 10.1038/s41598-024-66920-2.

- S. Phetyawa, C. Kamyod, T. Yooyatiwong, and C. G. Kim, “Application and Challenges of an IoT Bird Repeller System As a result of Bird Behavior,” in Int. Symp. on Wireless Personal Multimedia Communications (WPMC), pp. 323–327, 2022, 10.1109/WPMC55625.2022.10014932.

- F. A. Abdulla, Q. Y. Yusuf, S. M. Almosawi, M. Sadeq, and S. Baserrah, “Bird Hazard Mitigation System (BHMS): Review, design, and implementation,” IET Conf. Proc., vol. 2022, no. 26, pp. 301–306, 2023, 10.1049/ICP.2023.0541.

- K. Srividya, S. Nagaraj, B. Puviyarasi, T. S. Kumar, A. R. S. Rufus, and G. Sreeja, “Deeplearning Based Bird Deterrent System for Agriculture,” in Proc. of the 2021 4th Int. Conf. on Computing and Communications Technologies (ICCCT), pp. 555–559, 2021, 10.1109/ICCCT53315.2021.9711779.

- D. K. Amenyedzi et al., “System Design for a Prototype Acoustic Network to Deter Avian Pests in Agriculture Fields,” Agriculture (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 1, Jan. 2025,10.3390/agriculture15010010.

- X. Mao et al., “Domain randomization-enhanced deep learning models for bird detection,” Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2021,10.1038/s41598-020-80101-x.

- S. Kumar, H. K. Kondaveeti, C. G. Simhadri, and M. Yasaswini Reddy, “Automatic Bird Species Recognition using Audio and Image Data: A Short Review,” in Proc. IEEE InC4 2023 - 2023 IEEE Int. Conf. on Contemporary Computing and Communications, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023, 10.1109/InC457730.2023.10262973.

- A. Kempelis, A. Romanovs, and A. Patlins, “Using Computer Vision and Machine Learning Based Methods for Plant Monitoring in Agriculture: A Systematic Literature Review,” in 2022 63rd Int. Sci. Conf. on Information Technology and Management Science of Riga Technical University, ITMS 2022 - Proc., Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, 10.1109/ITMS56974.2022.9937119.

- Y. Wang et al., “Bird Object Detection: Dataset Construction, Model Performance Evaluation, and Model Lightweighting,” Animals, vol. 13, no. 18, Sep. 2023, 10.3390/ani13182924.

- P. Anusha and K. Manisai, “Bird Species Classification Using Deep Learning,” in 2022 Int. Conf. on Intelligent Controller and Computing for Smart Power, ICICCSP 2022, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, 10.1109/ICICCSP53532.2022.9862344.

- N. M. Jyothi et al., “AI Model for Bird Species Prediction with Detection of Rare, Migratory and Extinction Birds using ELM Boosted by OBS,” in Winter Summit on Smart Computing and Networks, WiSSCoN 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023, 10.1109/WiSSCoN56857.2023.10133844.

- M. U. Khan et al., “SafeSpace MFNet: Precise and Efficient MultiFeature Drone Detection Network,” Nov. 2022, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2211.16785.

- A. A. Ahmed and B. Nyarko, “Smart-Watcher: An AI-Powered IoT Monitoring System for Small-Medium Scale Premises,” in 2024 Int. Conf. on Computing, Networking and Communications, ICNC 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024, pp. 139–143, 10.1109/ICNC59896.2024.10556297.

- M. D. S. Antariksa et al., “Design and Development of Smart Farming System for Monitoring and Bird Pest Control Based on Raspberry Pi 4 with Implementation of YOLOv5 Algorithm,” in ICADEIS 2023 - Int. Conf. on Advancement in Data Science, E-Learning and Information Systems: Data, Intelligent Systems, and the Applications for Human Life, Proceeding, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023, 10.1109/ICADEIS58666.2023.10270906.

- D. Acharya et al., “Using deep learning to automate the detection of bird scaring lines on fishing vessels,” Biol Conserv, vol. 296, Aug. 2024, 10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110713.

- H. Alqaysi, I. Fedorov, F. Z. Qureshi, and M. O’nils, “A temporal boosted yolo-based model for birds detection around wind farms,” J Imaging, vol. 7, no. 11, Nov. 2021, 10.3390/jimaging7110227.

- M. G. Dorrer and A. E. Alekhina, “Solving the problem of biodiversity analysis of bird detection and classification in the video stream of camera traps,” in E3S Web of Conf., EDP Sciences, Jun. 2023, 10.1051/e3sconf/202339003011.

- J. Hentati-Sundberg et al., “Seabird surveillance: Combining CCTV and artificial intelligence for monitoring and research,” Remote Sens Ecol Conserv, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 568–581, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, Y. Liu, Z. Wang, and J. Lu, “Research on Airport Bird Recognition Based on Deep Learning,” in 2022 IEEE 22nd Int. Conf. on Communication Technology (ICCT), IEEE, Nov. 2022, pp. 1458–1462, 10.1109/ICCT56141.2022.10072560.

- P. Marcoň et al., “A system using artificial intelligence to detect and scare bird flocks in the protection of ripening fruit,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 12, Jun. 2021, 10.3390/s21124244.

- Z. Sun, Z. Hua, H. Li, and H. Zhong, “Flying Bird Object Detection Algorithm in Surveillance Video Based on Motion Information,” Jan. 2023, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2301.01917.

- N. Said Hamed Alzadjail, S. Balasubaramainan, C. Savarimuthu, and E. O. Rances, “A Deep Learning Framework for Real-Time Bird Detection and Its Implications for Reducing Bird Strike Incidents,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 17, Sep. 2024, 10.3390/s24175455.

- D. Harini, K. B. Sri, M. M. Durga, and O. V. Brahmaiah, “Crow Detection in Peanut Field Using Raspberry Pi,” in 2023 9th Int. Conf. on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems, ICACCS 2023, pp. 260–266, 2023, 10.1109/ICACCS57279.2023.10112813.

- S. A. Al-Showarah and S. T. Al-Qbailat, “Birds Identification System using Deep Learning,” [Online]. Available: www.ijacsa.thesai.org.

- Q. Song et al., “Benchmarking wild bird detection in complex forest scenes,” Ecol Inform, vol. 80, May 2024, 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102466.

- F. Samadzadegan, F. D. Javan, F. A. Mahini, and M. Gholamshahi, “Detection and Recognition of Drones Based on a Deep Convolutional Neural Network Using Visible Imagery,” Aerospace, vol. 9, no. 1, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Lin, J. Wang, and L. Ji, “An AI-based Wild Animal Detection System and Its Application,” Biodiversity Information Science and Standards, vol. 7, Sep. 2023, 10.3897/biss.7.112456.

- F. Zhao, R. Wei, Y. Chao, S. Shao, and C. Jing, “Infrared Bird Target Detection Based on Temporal Variation Filtering and a Gaussian Heat-Map Perception Network,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 11, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Kondaveeti, K. S. Sanjay, K. Shyam, R. Aniruth, S. C. Gopi, and S. V. S. Kumar, “Transfer Learning for Bird Species Identification,” in ICCSC 2023 - Proc. of the 2nd Int. Conf. on Computational Systems and Communication, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Kondaveeti et al., “Bird Species Recognition using Deep Learning,” in 2023 3rd Int. Conf. on Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing, AISP 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. T. Somoju and E. Sateesh, “Identification of Bird Species Using Deep Learning,” 2022. [Online]. Available: www.ijrti.org.

- C. Chalmers, P. Fergus, S. Wich, and S. N. Longmore, “Modelling Animal Biodiversity Using Acoustic Monitoring and Deep Learning,” [Online]. Available: https://www.xeno-canto.org/.

- J. Segura-Garcia et al., “5G AI-IoT System for Bird Species Monitoring and Song Classification,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 11, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Sanae, A. Kazutoshi, and U. Norimichi, “Distant Bird Detection for Safe Drone Flight and Its Dataset,” [MVA Organization], 2021.

- B. Kellenberger, T. Veen, E. Folmer, and D. Tuia, “Deep Learning Enhances the Detection of Breeding Birds in UAV Images,” EGU21, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Mehta, F. Dadboud, M. Bolic, and I. Mantegh, “A Deep Learning Approach for Drone Detection and Classification Using Radar and Camera Sensor Fusion,” in 2023 IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium, SAS 2023 - Proceedings, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhaoguo, Z. Zhenhua, and W. Yi, “Performance Assessment and Optimization of Bird Prevention Devices for Transmission Lines Based on Internet of Things Technology,” Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences, vol. 9, no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Rafa, Z. M. Al-Qfail, A. Adil Nafea, S. F. Abd-Hood, M. M. Al-Ani, and S. A. Alameri, “A Birds Species Detection Utilizing an Effective Hybrid Model,” in 2024 21st International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals and Devices, SSD 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024, pp. 705–710. [CrossRef]

- S. Heo, N. Baumann, C. Margelisch, M. Giordano, and M. Magno, “Low-cost Smart Raven Deterrent System with Tiny Machine Learning for Smart Agriculture,” in Conference Record - IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Kellenberger, T. Veen, E. Folmer, and D. Tuia, “21 000 birds in 4.5 h: Efficient large-scale seabird detection with machine learning,” Remote Sens Ecol Conserv, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 445–460, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Lucia Kharisma, G. Purnama Insany, A. Rizki Firdaus, and D. Nasrulloh, “Overcoming the Impact of Bird Pests on Rice Yields Using Internet of Things Based YOLO Method,” International Journal of Engineering and Applied Technology, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 18–32, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Kondaveeti, K. S. Sanjay, K. Shyam, R. Aniruth, S. C. Gopi, and S. V. S. Kumar, “Transfer Learning for Bird Species Identification,” in ICCSC 2023 - Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computational Systems and Communication, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Liang, X. Zhang, J. Kong, Z. Zhao, and K. Ma, “SMB-YOLOv5: A Lightweight Airport Flying Bird Detection Algorithm Based on Deep Neural Networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 84878–8. 4892, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Mahmood, S. Gregori, J. Runciman, J. Warbick, H. Baskar, and M. Badr, “UAV Based Smart Bird Control Using Convolutional Neural Networks,” in Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, pp. 89–94. [CrossRef]

- P. Marcoň et al., “A system using artificial intelligence to detect and scare bird flocks in the protection of ripening fruit,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 12, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Ritti and J. Chandrashekhara, “Detecting Intended Target Birds and Using Frightened Techniques in Crops to Preserve Yield,” International Journal of Innovative Research in Engineering & Management, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 24–27, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Schiano, D. Natter, D. Zambrano, and D. Floreano, “Autonomous Detection and Deterrence of Pigeons on Buildings by Drones,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 1745– 1755, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. G. Weinstein et al., “A general deep learning model for bird detection in high resolution airborne imagery, Aug. 06, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhao, “Bird Movement Recognition Research Based on YOLOv4 Model,” in Proceedings - 2022 4th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Manufacturing, AIAM 2022, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, pp. 441–444. [CrossRef]

- Rutuja Aher, Prathamesh Gawali, Parag Kalbhor, Bhagyashree Mali, and Prof. N.V.Kapde, “Birdy: A Bird Detection System using CNN and Transfer Learning,” International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology, pp. 602–604, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Neeli, C. S. R. Guruguri, A. R. A. Kammara, V. Annepu, K. Bagadi, and V. R. R. Chirra, “Bird Species Detection Using CNN and EfficientNet-B0,” in 2023 International Conference on Next Generation Electronics, NEleX 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Upadhyay, S. K. Murthy, and A. A. B. Raj, “Intelligent system for real time detection and classification of aerial targets using CNN,” in Proceedings - 5th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems, ICICCS 2021, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., May 2021, pp. 1676–1681. [CrossRef]

- Dr. N. S. Sindhuri and Dr. R. Rajani, “Smart Bird Sanctuary Management Platform using Resnet50,” Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 4787–4791, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Chaurasia and B. D. K. Patro, “Real-time Detection of Birds for Farm Surveillance Using YOLOv7 and SAHI,” in 2023 3rd International Conference on Computing and Information Technology, ICCIT 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023, pp. 442–450. [CrossRef]

- H.-T. Vo, N. Thien, and K. C. Mui, “Bird Detection and Species Classification: Using YOLOv5 and Deep Transfer Learning Models,” [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/gpiosenka/100-.

- F. Mashuk, Samsujjoha, A. Sattar, and N. Sultana, “Machine learning approach for bird detection,” in Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks, ICICV 2021, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Feb. 2021, pp. 818–822. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen and Z. Zhang, “Optimization Research of Bird Detection Algorithm Based on YOLO in Deep Learning Environment,” https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219467825500597, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Shrestha, C. Glackin, J. Wall, and N. Cannings, “Bird Audio Diarization with Faster R-CNN,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 12891 LNCS, pp. 415–426, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Shrestha, C. Glackin, J.Wall, and N. Cannings, “Bird Audio Diarization with Faster R-CNN,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 12891 LNCS, pp. 415–426, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Dere and P. Aher, “AM-DRCN: Adaptive Migrating Bird Optimization-based Drift-Enabled Convolutional Neural Network for Threat Detection in Internet of Things,” in Proceedings of 5th International Conference on IoT Based Control Networks and Intelligent Systems, ICICNIS 2024, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024, pp. 1085–1091. [CrossRef]

- S. Pan, D. Zhao, and W. Zhang, “CNN-based Multi-model Birdcall Identification on Embedded Devices,” in Proceedings - 5th IEEE International Conference on Smart Internet of Things, SmartIoT 2021, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2021, pp. 245–251. [CrossRef]

- G. Bota, R. Manzano-Rubio, L. Catalán, J. Gómez-Catasús, and C. Pérez-Granados, “Hearing to the Unseen: AudioMoth and BirdNET as a Cheap and Easy Method for Monitoring Cryptic Bird Species,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 16, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Cinkler, K. Nagy, C. Simon, R. Vida, and H. Rajab, “Two-Phase Sensor Decision: Machine-Learning for Bird Sound Recognition and Vineyard Protection,” IEEE Sens J, vol. 22, no. 12, pp. 11393–11404, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Conde, K. Shubham, P. Agnihotri, N. D. Movva, and S. Bessenyei, “Weakly-Supervised Classification and Detection of Bird Sounds in the Wild. A BirdCLEF 2021 Solution,” Jul. 2021, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2107.04878.

- S. DIsabato, G. Canonaco, P. G. Flikkema, M. Roveri, and C. Alippi, “Birdsong Detection at the Edge with Deep Learning,” in Proceedings - 2021 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing, SMARTCOMP 2021, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Aug. 2021, pp. 9–16. [CrossRef]

- M. Durgun, “An Acoustic Bird Repellent System Leveraging Edge Computing and Machine Learning Technologies,” in 2023 Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications Conference, ASYU 2023, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. C. Lopes, R. Felício De Oliveira, V. Vicente, and G. Neto, “Towards an IoT-Based Architecture for Monitoring and Automated Decision-Making in an Aviary Environment.

- Z. Huang et al., “TinyChirp: Bird Song Recognition Using TinyML Models on Low-power Wireless Acoustic Sensors,” Jul. 2024, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2407.21453.

- H. J. Al Dawasari, M. Bilal, M. Moinuddin, K. Arshad, and K. Assaleh, “DeepVision: Enhanced Drone Detection and Recognition in Visible Imagery through Deep Learning Networks,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 23, no. 21, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Morales et al., “Method for passive acoustic monitoring of bird communities using UMAP and a deep neural network,” Ecol Inform, vol. 72, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Ntalampiras and I. Potamitis, “Acoustic detection of unknown bird species and individuals,” CAAI Trans Intell Technol, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 291–300, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Sakhri et al., “Audio-Visual Low Power System for Endangered Waterbirds Monitoring,” in IFAC-PapersOnLine, Elsevier B.V., Jul. 2022, pp. 25–30. [CrossRef]

- M. Toenies and L. N. Rich, “Advancing bird survey efforts through novel recorder technology and automated species identification,” Calif Fish Game, vol. 107, no. 2, pp. 56–70, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Tsompos, V. F. Pavlidis, and K. Siozios, “Designing a Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network for Bird Audio Detection,” in 2022 Panhellenic Conference on Electronics and Telecommunications, PACET 2022, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Verma and S. Kumar, “AviEar: An IoT-based Low Power Solution for Acoustic Monitoring of Avian Species,” IEEE Sens J, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Elias, N. Golubovic, C. Krintz, and R. Wolski, “Where’s the bear?- Automating wildlife image processing using IoT and edge cloud systems,” in Proceedings - 2017 IEEE/ACM 2nd International Conference on Internet-of-Things Design and Implementation, IoTDI 2017 (part of CPS Week), Association for Computing Machinery, Inc, Apr. 2017, pp. 247–258. [CrossRef]

- J. Höchst et al., “Bird@Edge: Bird Species Recognition at the Edge,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 13464 LNCS, pp.69–86, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Höchst et al., “Bird@Edge: Bird Species Recognition at the Edge,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 13464 LNCS, pp. 69–86, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Teterja, J. Garcia-Rodriguez, J. Azorin-Lopez, E. Sebastian-Gonzalez, R. E. van der Walt, and M. J. Booysen, “An Image Mosaicing-Based Method for Bird Identification on Edge Computing Devices,” Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol. 750 LNNS, pp. 216–225, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Mahmud and A. N. Toosi, “Con-Pi: A Distributed Container-based Edge and Fog Computing Framework,” Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. C. C. Tavares and L. B. Ruiz, “Towards a Novel Edge to Cloud IoMT Application for Wildlife Monitoring using Edge Computing,” in 7th IEEE World Forum on Internet of Things, WF-IoT 2021, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Jun. 2021, pp. 130–135. [CrossRef]

- A. Manna, N. Upasani, S. Jadhav, R. Mane, R. Chaudhari, and V. Chatre, “Bird Image Classification using Convolutional Neural Network Transfer Learning Architectures,” [Online]. Available: www.ijacsa.thesai.org.

- N. Das, N. Padhy, N. Dey, A. Mukherjee, and A. Maiti, “Building of an edge enabled drone network ecosystem for bird species identification,” Ecol Inform, vol. 68, p. 101540, May 2022,. [CrossRef]

- M. Yuliana, I. C. Fitrah, and M. Z. S. Hadi, “Intelligent Bird Detection and Repeller System in Rice Field Based on Internet of Things,” in Proceeding - COMNETSAT 2023: IEEE International Conference on Communication, Networks and Satellite, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023, pp. 615–621. [CrossRef]

- M. O. Arowolo, F. T. Fayose, J. A. Ade-Omowaye, A. A. Adekunle, and S. O. Akindele, “Design and Development of an Energy-efficient Audio-based Repellent System for Rice Fields,” International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 82–94, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Published after 2020 | Published before 2020 |

| Describes machine learning models for bird detection/repellence | Focuses on traditional (non-ML) bird control methods |

| Involves IoT-based solutions (e.g., edge computing, smart sensors) | Lacks technical details on ML model architecture |

| Uses image/audio/video-based detection techniques | Used other detection techniques |

| Provides open or well-documented datasets | Uses proprietary or inaccessible datasets |

| Data Collection Method | Dataset Type | Preprocessing Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Image capture [3,29,30] | Custom | Annotation, resizing, OpenCV processing, frame subtraction, contour extraction |

| Video surveillance [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] | Custom | Frame extraction, annotation, background subtraction, noise removal, image scaling, data augmentation, classification |

| Video surveillance [39] | COCO | Frame extraction, data augmentation |

| Image collection [40,41] | Custom | Grayscale conversion, feature extraction, motion blur, contrast adjustment |

| Image collection [28,42] | Public datasets | Contrast enhancement, annotation |

| Image collection [43,44] | Multiple datasets | Frame difference, morphology, resizing, standardization |

| Image collection [45,46] | Kaggle dataset | Duplicate removal, cropping, resizing |

| Image collection [47] | CUB-200-2011 | Grayscale conversion, histogram analysis |

| Camera traps [48,49] | Custom | Annotation, conversion to TFRecords |

| Drone-mounted camera [50] | Custom | Patch division, data augmentation |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicle imagery [51] | Custom | Annotation, orthomosaic creation, orthomosaic division |

| Radar and camera [52] | Custom | Annotation, data fusion, feature extraction |

| Webcam feeds [6] | Custom | No mention found |

| Image and sensor data [53] | No mention found | Feature extraction, data fusion |

| Model Architecture | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Mask R-CNN [29] | Accuracy: 96.3%, Prediction time: 1.61s | High accuracy for various object classes, including birds (95.6%) |

| Mask R-CNN with ResNet-101-FPN [17] | Precision: 0.86 with low recall | High precision |

| Faster R-CNN with ResNet50 [22,31] | Detection precision: 0.87 | Effective for BSL detection, performance varies by vessel and conditions |

| VGG-19 with various classifiers [40] | ANN Accuracy: 70.99%, Precision: 0.718, Recall: 0.71, F1 score: 0.708 | ANN outperformed other classifiers, high training time noted |

| YOLOv4 variants [16,32] | mAP: up to 94%, Recall: 96%, F1 score: 94% | Ensemble model showed best performance, challenges with small birds |

| Faster R-CNN with ResNet101 [48] | Accuracy: 96.71%, Sensitivity: 88.79% | High accuracy and sensitivity, challenges with smaller objects |

| YOLOv5 [30] | Processing speed: 0.78–0.8 FPS | Limited processing speed, detection range varies by environment |

| YOLO variants [33] | Precision: up to 0.99, Recall: up to 0.99 | YOLOv3-tiny with comparative modules performed best |

| CenterNet [50] | mAP: 66.72–72.13 | Performance varied with data augmentation, 6 FPS on GPU |

| SSD with MobileNet [39] | mAP: 78%, FPS: 89 | Improved performance with data augmentation |

| Custom CNN [55] | Detection Accuracy: 77%, Average Precision: 87% | Effective for raven detection, low inference latency |

| YOLOv5-medium-960 [34] | Precision: 0.91, Recall: 0.79, F1-score: 0.85 | High performance, real-time inference possible |

| ResNet-18 based CNN [56] | Precision: 90% at 90% recall (Royal Terns) | Varied performance across species, challenges with similar species |

| YOLOv3-320 [57] | 100% accuracy in tests | Perfect detection in controlled tests, real-world performance not specified |

| MultiFeatureNet variants [28] | Precision up to 99.8% for birds | High performance, especially MFNet-L for overall detection |

| MobileNetV2 [58] | Test Accuracy: 95%, Real-time Accuracy: 80% | High accuracy, outperformed other tested architectures |

| SMB-YOLOv5 [59] | Precision: 82.6%, Recall: 71.1%, mAP@50: 77.1% | Real-time detection at 24 FPS |

| CNN (unspecified) [60] | Accuracy: Over 98% | High accuracy, ResNet outperformed AlexNet and VGG |

| CNN (unspecified) [61] | Precision: 83.4–100% (varies by class) | High precision for bird and flock detection |

| YOLOv5, YOLOv7, RNN [52] | Accuracy: 98% (drones), 94% (birds) | High accuracy, challenges with false positives for birds |

| Faster R-CNN, SSD variants [6] | mAP: 92.3% (Faster R-CNN with ResNet152) | Faster R-CNN outperformed SSD models |

| YOLOv4-tiny [55] | mAP: 92.04%, FPS: 40 | Good balance of accuracy and speed |

| EfficientNet-B3 | Accuracy: 94.5%, F1-score: 0.91 | Robust classification performance, computationally efficient |

| YOLOv8 [53] | Precision: 94.8%, Recall: 89.5% | Improved real-time detection and accuracy |

| YOLO, ResNet100 [62] | YOLOv3 mAP: 57.9% (COCO test-dev) | Specific bird detection performance not reported |

| YOLOv4 [42] | Overall accuracy: 83%, mAP: 84% | Good performance, challenges with crowded backgrounds |

| Faster R-CNN [63] | mAP: 69.84% (overall) | Effective for pigeon detection, some false negatives |

| Fourier descriptors, YOLO [3] | FD: 83% accuracy, YOLO: 97% accuracy | YOLO more accurate but slower on Raspberry Pi |

| DCNN (unspecified) [47] | Overall accuracy: 80–90% | Competitive performance compared to other approaches |

| Various (Cascade RCNN, YOLO, etc.) [41] | mAP: 0.704 (Cascade RCNN with Swin-T) | Cascade RCNN performed best, challenges with small birds |

| ConvLSTM-PAN, LW-USN [37] | AP50: 0.7089 for FBOD-BMI | Outperformed YOLOv5l, challenges with higher IOU thresholds |

| FBOD-Net [38] | AP: 76.2%, 59.87 FPS | Outperformed several other models, good speed-accuracy balance |

| RetinaNet with ResNet-50 [64] | Recall: >65%, Precision: >50% (general model) | Improved performance with fine-tuning on local data |

| YOLOv4 [65] | Accuracy: 99.13%, 12 FPS | Outperformed Faster R-CNN and CNN in accuracy and speed |

| Technology | Data Transfer Speed | Power Consumption | Range | Cost | Suitability for Media (Image/Video) | Stability in Remote Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wi-Fi | High | High | Limited | Medium | High | Medium |

| LoRa | Low | Very Low | Very Long | Low | Poor | High |

| Cellular (4G/5G) | Very High | High | Very Long | High | Excellent | High |

| Zigbee | Moderate | Very Low | Short to Medium | Low | Poor | Medium |

| Integration Methods | Repellence Method Effectiveness Rating | Implementation Complexity | Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sound-based [30,101] | Moderate | Low | Low to Moderate |

| Sound-based [55] | High (77% detection accuracy) | Moderate | Low |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicle with ultrasonic [60] | High (>98% accuracy) | High | Low to Moderate |

| AI-triggered servo [57] | High (100% detection in tests) | Moderate | Low |

| Drone-based visual [63] | High (significant reduction in stay time) | High | Low |

| Sound-based [62] | No mention found | Moderate | Low |

| Lasers [17] | Moderate | Moderate | Low to Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).