1. Introduction

Adequate postoperative pain control following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR) of the shoulder is essential for patient rehabilitation, functional recovery, and early restoration of range of motion [

1]. As a result, the inter-scalene brachial plexus block (ISB) has become the conventional modality for postoperative pain control [

2].

Single-shot ISB is widely utilized for peri-operative analgesia in shoulder surgery; however, it is frequently associated with adverse events such as dyspnea, hoarseness, inadequate anesthetic effect, and dizziness [

3]. Additionally, its analgesic efficacy typically diminishes approximately 24 hours post-procedure [

4,

5]. To manage ongoing pain after ISB subsides, intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA) is commonly administered. Nonetheless, IV-PCA frequently induces significant adverse effects—particularly postoperative nausea and vomiting [

6,

7]—leading to patient discomfort, premature discontinuation, inadequate pain relief, and increased healthcare costs.

To extend analgesic coverage beyond the limited duration of ISB without encountering the adverse effects associated with IV-PCA, clinicians have explored alternative strategies such as the intra-operative suprascapular nerve block (I-SSNB) [

8,

9]. Previous comparative studies indicate that I-SSNB alone might be insufficient, with many patients still requiring supplemental opioid rescue medications; however, combining I-SSNB with ISB seems to improve early postoperative pain control [

10]. Recent studies also suggest that I-SSNB can mitigate the “rebound” pain observed after the analgesic effects of ISB dissipate [

1].

Given its potential to avoid IV-PCA-related adverse events, it is clinically meaningful to ascertain whether I-SSNB alone can provide analgesic efficacy comparable to that achieved when combined with IV-PCA. Thus, the present study was specifically designed to evaluate if standalone I-SSNB can effectively control postoperative pain without necessitating the additional use of IV-PCA, thereby minimizing patient discomfort and associated complications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

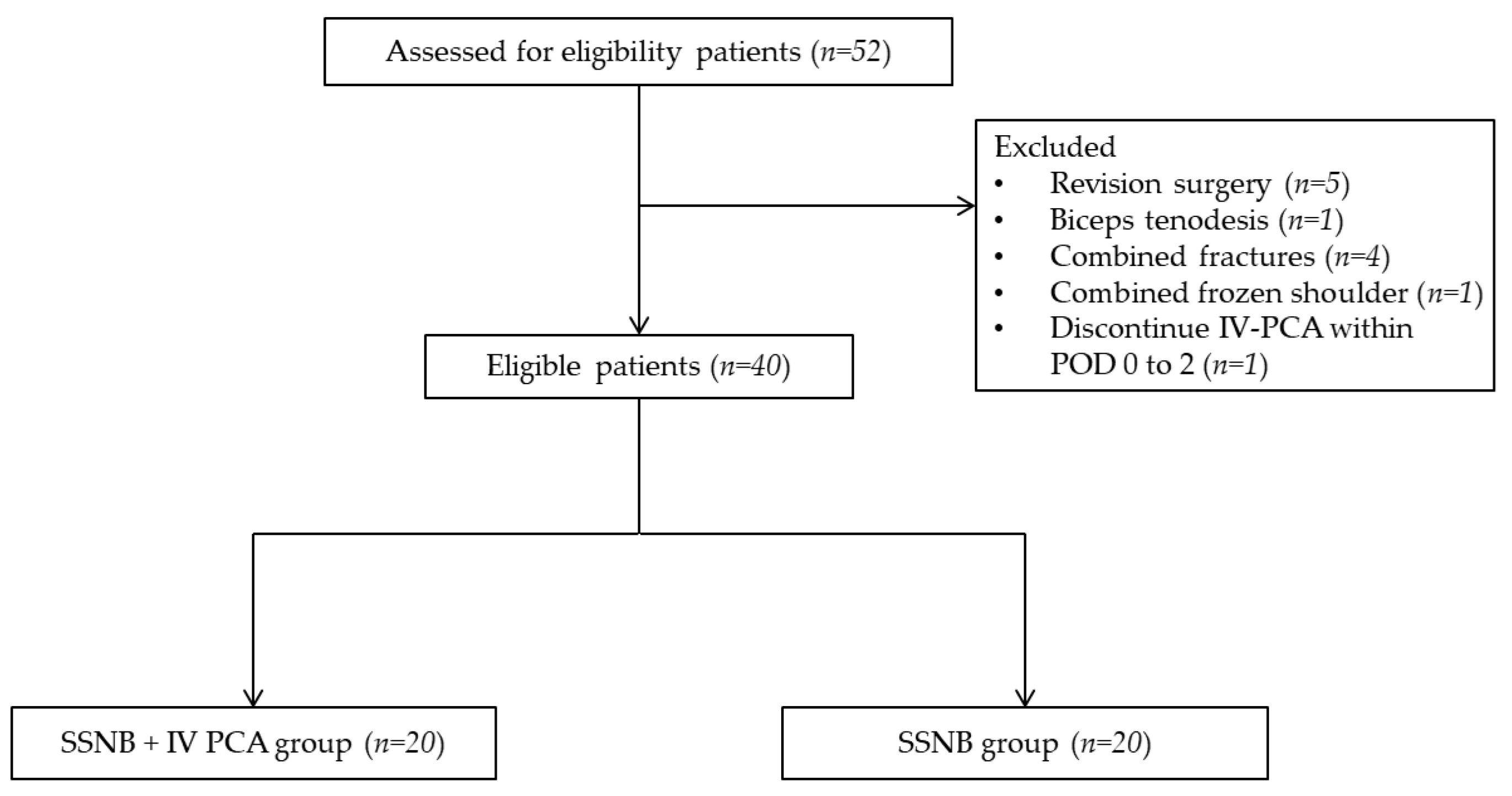

This retrospective cohort study was conducted following approval by the Institutional Review Board of Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB No. 2025-06-003), with a waiver of informed consent. Adult patients who underwent elective arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR) between December 2024 and May 2025 were reviewed. Patients who received intra-operative suprascapular nerve block (I-SSNB) in combination with inter-scalene brachial plexus block (ISB) for postoperative analgesia were eligible for inclusion. Based on the use of adjunctive intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA), patients were categorized into two groups: ISB + I-SSNB group and ISB + I-SSNB + IV-PCA group.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who underwent concomitant procedures involving the affected shoulder, such as revision surgery, biceps tenodesis, fracture fixation, or capsular release for frozen shoulder; and (2) patients who permanently discontinued IV-PCA due to systemic adverse effects—such as nausea or vomiting—within postoperative days 0 to 2. Patients who experienced such adverse effects but resumed PCA after anti-emetic treatment, or continued PCA with bolus-only suspension, were not excluded (

Figure 1).

2.2. Operative Technique of SSNB

All procedures were performed by the single orthopedic surgeon with subspecialty training in shoulder surgery, with patients placed in the beach-chair position under general anesthesia. A single-shot, ultrasound-guided interscalene brachial plexus block (ISB) was performed, followed by induction of general anesthesia; both procedures were conducted by an anesthesiologist.

After subacromial bursectomy, a Neviaser portal was established. With the arthroscope placed in the posterior portal to visualize the suprascapular notch, the superior transverse scapular ligament (STSL) was cut by arthroscopic scissor. Once a guide needle reached the posterior surface of the STSL, a 19-gauge FX Springwound Epidural Anesthesia Catheter (Perifix

®) was inserted via needle through the Neviaser portal and advanced approximately 1 cm beyond the posterior border of the STSL to prevent catheter displacement (

Figure 2). The catheter tip was positioned adjacent to the suprascapular nerve at the base of the suprascapular notch, and fixation was secured using 3-0 nylon tagging suture. Rotator cuff repair was subsequently performed using a standard suture-bridge technique.

2.3. Post-Operative Analgesic Protocol

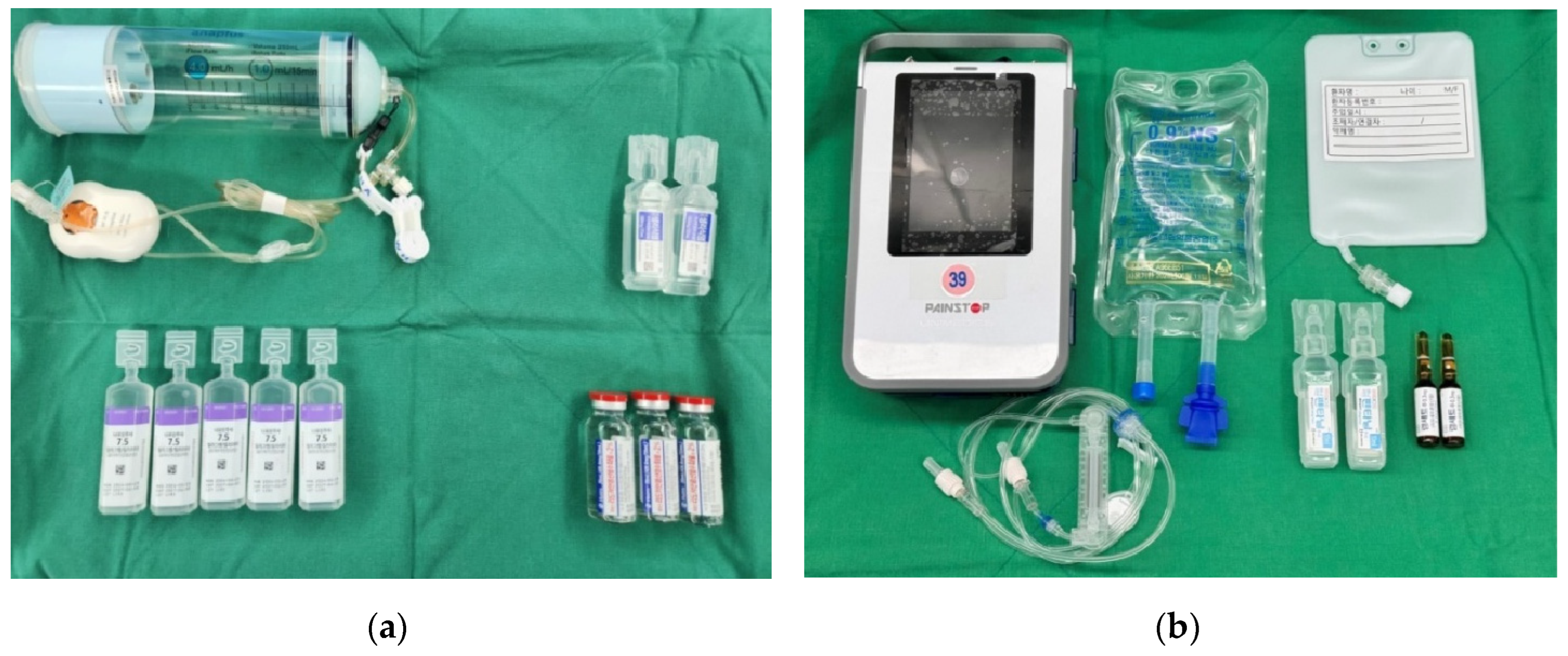

Immediately following arthroscopic surgery, a continuous I-SSNB infusion was initiated using an elastomeric pump. The infusion solution consisted of 60 mL of 2% lidocaine (20 mg/mL), 100 mL of 0.75% ropivacaine (7.5 mg/mL), and 40 mL of normal saline, yielding a total volume of 200 mL. This mixture was continuously infused at a rate of approximately 4.17 mL/h. Patients were instructed to self-administer a bolus dose by pressing a button on the pump in response to pain. The infusion system was refilled as needed and maintained until the morning of postoperative day (POD) 3 to maintain consistent pain relief.

In the I-SSNB + IV-PCA group, patients received a fentanyl-based intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA) regimen consisting of a continuous basal infusion at 1 µg·kg−1·h−1, a 15 µg bolus dose, and a 15-minute lockout interval. The device was maintained until the morning of POD 3, and patients were allowed to self-administer bolus doses for breakthrough pain. Intravenous pethidine (25 mg) was provided as rescue analgesia when the visual analogue scale (VAS) score was ≥ 4 upon patient request.

In cases where IV-PCA–related side effects such as nausea or vomiting occurred, bolus administration was initially suspended while maintaining the basal infusion. If symptoms persisted, continuous infusion was also temporarily halted. Anti-emetic medications were administered as needed, and the decision to resume or discontinue IV-PCA was made according to the patient’s clinical condition and response to treatment.

Figure 3.

Post-operative analgesic preparation sets. (a) Components used for continuous intra-operative suprascapular nerve block (I-SSNB), including an elastomeric pump, local anesthetics (2% lidocaine, 0.75% ropivacaine), and normal saline. (b) Materials required for intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA), including the PCA device, fentanyl-based solution, ramosetron hydrochloride, IV lines and normal saline.

Figure 3.

Post-operative analgesic preparation sets. (a) Components used for continuous intra-operative suprascapular nerve block (I-SSNB), including an elastomeric pump, local anesthetics (2% lidocaine, 0.75% ropivacaine), and normal saline. (b) Materials required for intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA), including the PCA device, fentanyl-based solution, ramosetron hydrochloride, IV lines and normal saline.

2.4. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was rest-pain VAS at six predefined intervals: post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), 10 pm on the day of surgery, and 9 am on postoperative day (POD) 1 to POD 3. Secondary outcomes included cumulative rescue opioid consumption (converted to IV morphine equivalents), IV-PCA device events (pump alarm), postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test; categorical data were analysed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Python 3.10 (SciPy 1.11) and IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

40 patients met inclusion criteria with allocated to each group. Demographic and surgical characteristics did not differ significantly (

Table 1).

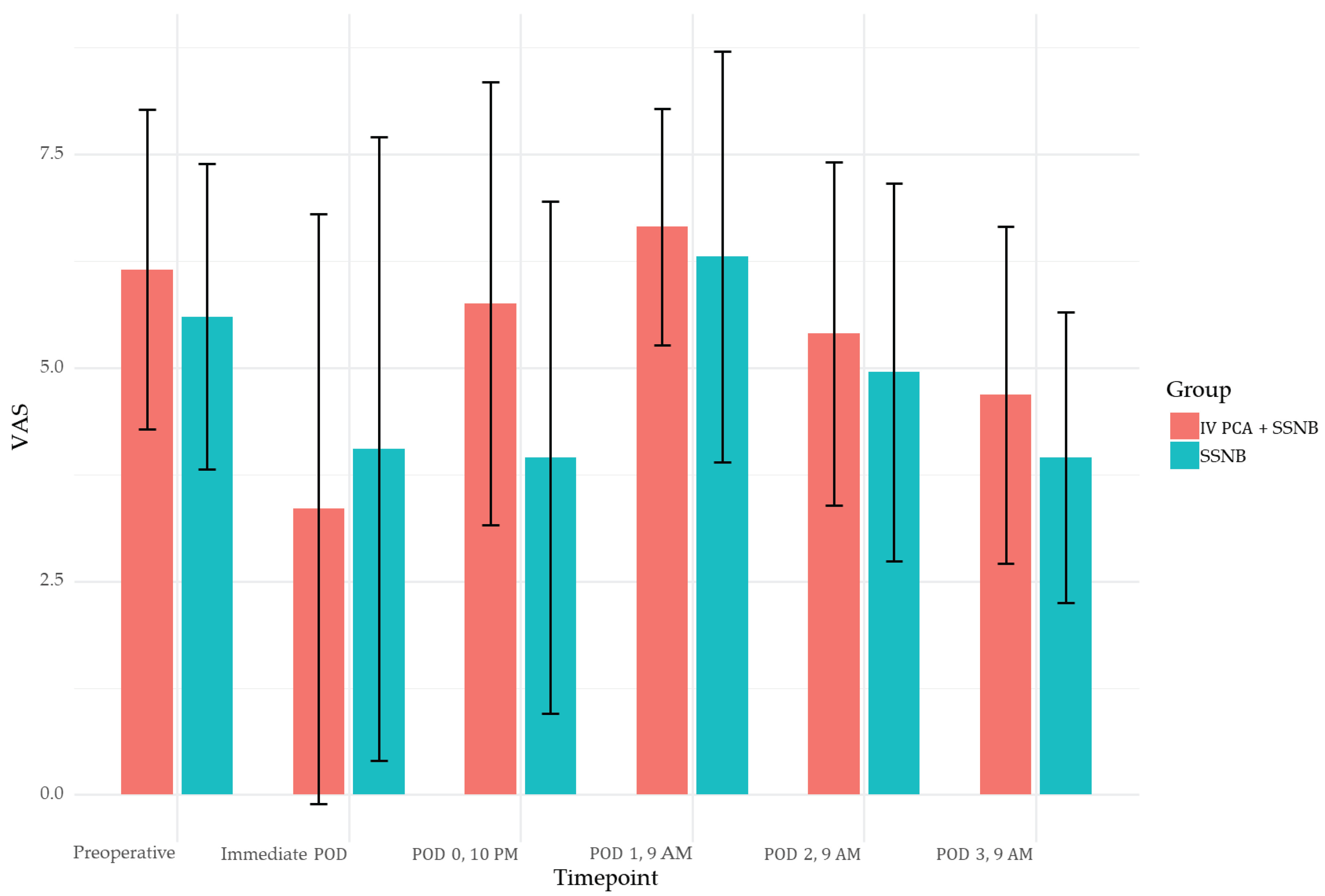

3.2. Pain Scores

Mean VAS values were comparable at all time-points, with no significant between-group differences. (

Table 2 and

Figure 4)

3.3. Opioid Consumption and Adverse Events

Cumulative rescue opioid consumption did not differ significantly between the combined IV-PCA and I-SSNB alone groups (0.80 ± 0.41 vs 0.55 ± 0.51 doses, P = 0.099) (

Table 3).

Three PONV episodes and four pump alarms were recorded exclusively in the IV-PCA + I-SSNB group. The pump alarms were attributed to either transient occlusion of the infusion line or minor technical malfunctions of the PCA device. All events were promptly resolved without necessitating discontinuation of PCA. No block-related complications were observed in either group (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

This study investigated whether the addition of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA) to intra-operative suprascapular nerve block (I-SSNB) could enhance postoperative pain control after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR). Our findings demonstrated that combining IV-PCA with I-SSNB did not result in superior analgesia compared to I-SSNB alone. Pain scores between the two groups were statistically comparable at all measured time points, and cumulative opioid rescue requirements did not differ significantly. Notably, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) occurred only in the I-SSNB + IV-PCA group, whereas no such adverse events were observed in patients who received I-SSNB alone.

These results are noteworthy given that IV-PCA has traditionally been employed to maintain consistent analgesia following sinlge-shot regional blocks such as interscalene or suprascapular nerve blocks [

11]. However, despite this theoretical advantage, patients in the I-SSNB + IV-PCA group did not experience better pain relief. Instead, the use of IV-PCA was associated with a greater incidence of systemic side effects, including nausea, vomiting, and urinary retention—adverse events that were entirely absent in the I-SSNB-only group. Such side effects may contribute to increased discomfort and reduced tolerance of postoperative care, even in the absence of clear analgesic benefit [

12].

Interestingly, although the differences were not statistically significant, pain scores in the I-SSNB-only group were numerically lower than those in the combination group at several postoperative time points. This trend raises important considerations: it is possible that opioid-related side effects contributed to increased discomfort or that inconsistent use of the PCA device may have limited its intended benefits. Additionally, systemic opioids may affect patients’ overall well-being and subjective pain perception negatively, despite their analgesic properties.

Given these findings, our study suggests that while I-SSNB alone may offer a comparable level of analgesia to the combined use of IV-PCA, it may not be sufficient to achieve optimal postoperative pain control in patients undergoing ARCR. Pain scores remained relatively elevated in both groups during the early postoperative period, indicating a need for further refinement of current analgesic strategies. Eliminating routine IV-PCA use may help reduce opioid-related adverse effects and simplify postoperative care, particularly in elderly or opioid-sensitive populations. Further research is warranted to establish more effective and tolerable analgesic strategies for ARCR.

Nonetheless, this study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design introduces a risk of selection bias and limits the ability to infer causality. Second, the sample size was relatively small, which may have reduced statistical power to detect subtle but clinically meaningful differences. Third, while we standardized the I-SSNB technique, anatomical variability and catheter positioning could have influenced block efficacy. Finally, functional outcomes and long-term pain relief were not assessed, leaving the durability and broader impact of each analgesic strategy unknown.

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes to growing evidence that targeted regional analgesia—when appropriately executed—may reduce the need for systemic opioids. Our findings support the clinical adoption of I-SSNB as a stand-alone modality for postoperative pain management in arthroscopic shoulder procedures.

5. Conclusions

In this retrospective study, we found that intraoperative suprascapular nerve block (I-SSNB) alone provided postoperative analgesia comparable to that achieved with the combined use of I-SSNB and intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA) in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR). Although both strategies were effective in reducing postoperative pain, the addition of IV-PCA did not result in superior analgesic outcomes and was associated with a higher incidence of systemic adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, and urinary retention—events that were not observed in the I-SSNB-only group. These findings suggest that the routine implementation of IV-PCA may be unnecessary when effective regional analgesia with I-SSNB is provided.

Nevertheless, absolute pain scores in both groups remained higher than expected during the early postoperative period, indicating that neither approach achieved fully satisfactory analgesia. This highlights the need for further efforts to improve postoperative pain control strategies—potentially through refinement of regional block techniques, optimization of infusion parameters, or the incorporation of adjunctive multimodal analgesia tailored to the demands of ARCR.

Future prospective, randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes and extended follow-up periods are warranted to validate these findings and to evaluate the long-term efficacy, safety, and functional outcomes of I-SSNB-focused analgesic protocols in arthroscopic shoulder surgery.

References

- Kim, J.Y., et al., Suprascapular Nerve Block Is an Effective Pain Control Method in Patients Undergoing Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 2021. 9(1): p. 2325967120970906.

- Warrender, W.J., et al., Pain Management After Outpatient Shoulder Arthroscopy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2017. 45(7): p. 1676-1686.

- Tanijima, M., et al., Adverse events associated with continuous interscalene block administered using the catheter-over-needle method: a retrospective analysis. BMC Anesthesiology, 2019. 19(1): p. 195.

- Abdallah, F.W., et al., Will the Real Benefits of Single-Shot Interscalene Block Please Stand Up? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 2015. 120(5): p. 1114-1129.

- Oh, J.H., et al., Comparison of Analgesic Efficacy between Single Interscalene Block Combined with a Continuous Intra-bursal Infusion of Ropivacaine and Continuous Interscalene Block after Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. cios, 2009. 1(1): p. 48-53.

- Hah, J.M., et al., Chronic Opioid Use After Surgery: Implications for Perioperative Management in the Face of the Opioid Epidemic. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 2017. 125(5): p. 1733-1740.

- Dinges, H.-C., et al., Side Effect Rates of Opioids in Equianalgesic Doses via Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 2019. 129(4): p. 1153-1162.

- Hussain, N., et al., Is Supraclavicular Block as Good as Interscalene Block for Acute Pain Control Following Shoulder Surgery? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 2020. 130(5): p. 1304-1319.

- Sun, C., et al., Suprascapular nerve block and axillary nerve block versus interscalene nerve block for arthroscopic shoulder surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine, 2021. 100(44): p. e27661.

- Singelyn, F.J., L. Lhotel, and B. Fabre, Pain Relief After Arthroscopic Shoulder Surgery: A Comparison of Intraarticular Analgesia, Suprascapular Nerve Block, and Interscalene Brachial Plexus Block. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 2004. 99(2): p. 589-592.

- Cho, N.S., J.H. Ha, and Y.G. Rhee, Patient-Controlled Analgesia after Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair:Subacromial Catheter Versus Intravenous Injection. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2007. 35(1): p. 75-79.

- Scoggin, J.F., et al., Subacromial and intra-articular morphine versus bupivacaine after shoulder arthroscopy. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery, 2002. 18(5): p. 464-468.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).