Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 03B05, 97E30, 97E60

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives of This Article

1.1.1. First Objective

1.1.2. Second Objective

1.2. Relevant Aspects of the STA

2. Basic Notions on Propositional Calculus and Set Theory

2.1. Propositional Calculus

2.2. Set Theory

. The set

. The set  to which all the elements in the universal set considered that do not belong to S belong is called the complement set of S. Note that the “double complementation” of any set S makes it possible to obtain S once more: S =

to which all the elements in the universal set considered that do not belong to S belong is called the complement set of S. Note that the “double complementation” of any set S makes it possible to obtain S once more: S =

3. Four Types of Propositions Using Set Theory

3.1. Universal Affirmative Categorical Propositions

2 ⊆

2 ⊆  1

1

3.2. Universal Negative Categorical Propositions

2 ; S2 ⊆

2 ; S2 ⊆  1

1

3.3. Particular Affirmative Categorical Propositions

3.4. Particular Negative Categorical Propositions

2) ⊆

2) ⊆  2 ; (S1 ∩

2 ; (S1 ∩  2) ⊆ S1

2) ⊆ S1

4. Using SPC to Formulate Different Categorical Propositions

4.1. Using SPC Symbols to State a Universal Affirmative Categorical Proposition

2 ⊆

2 ⊆  1

1

1 and

1 and  2 are the following:

2 are the following: 1

1

2

2

2 and

2 and  1 is the following:

1 is the following: 2 ⊆

2 ⊆  1

1

i.

i.4.2. Using the SPC Symbols to Express a Universal Negative Categorical Proposition

2;

2;  1

1

2 and

2 and  1 are the following:

1 are the following: 2

2

1

1

4.3. Using the SPC Symbols to Express a Particular Affirmative Categorical Proposition

9).

9). 9.

9.4.4. Using the SPC Symbols to Express a Particular Negative Categorical Proposition

2) ⊆

2) ⊆  2 ; (S1 ∩

2 ; (S1 ∩  2) ⊆ S1

2) ⊆ S1

2) ⊆

2) ⊆  2 and (S1 ∩

2 and (S1 ∩  2) ⊆ S1 are the following:

2) ⊆ S1 are the following: 2) ⊆ S2

2) ⊆ S2

2) ⊆ S1

2) ⊆ S1

4.5. A SPC Resource Not Used in This Article

17) and (x ∈

17) and (x ∈  17

17  17)).

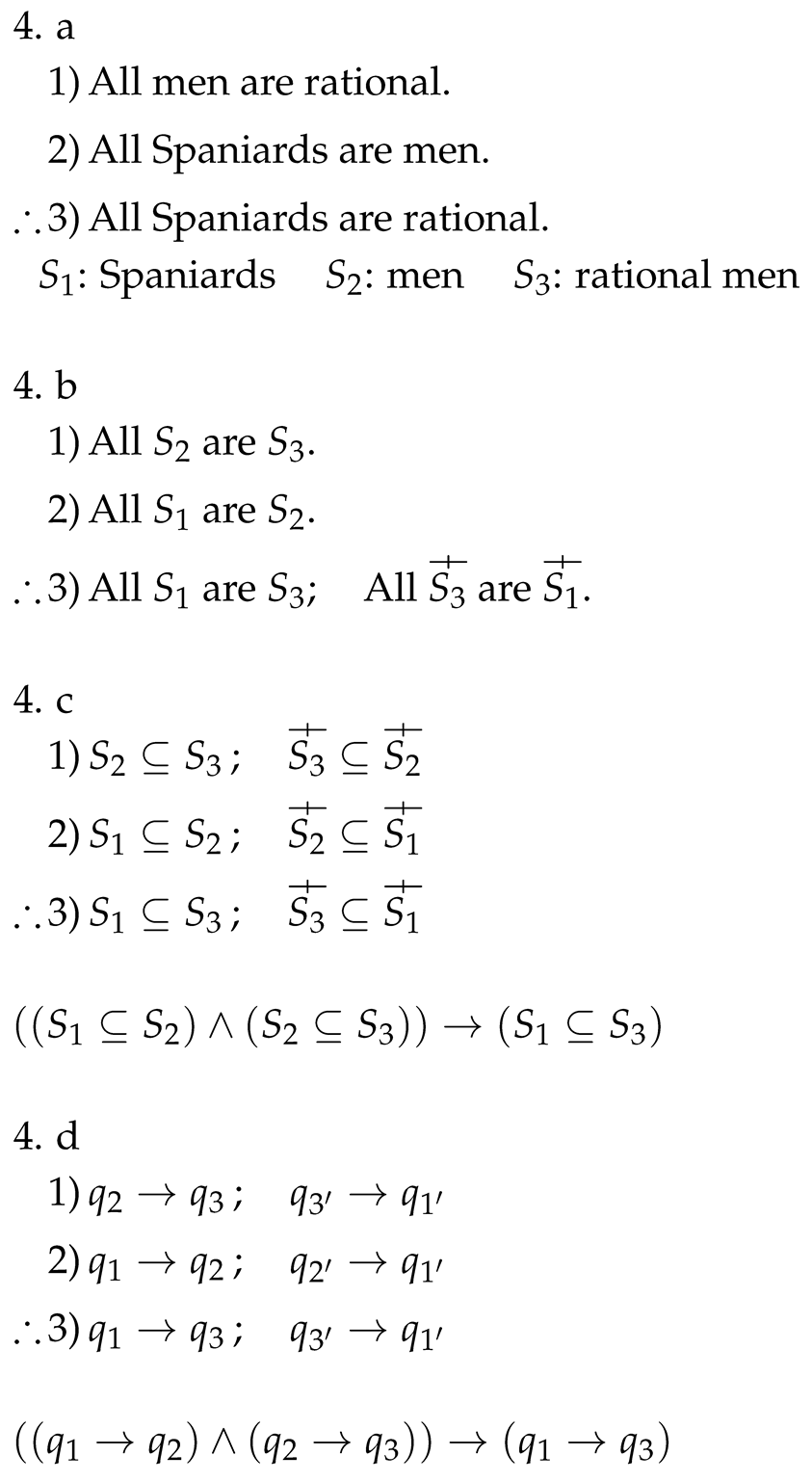

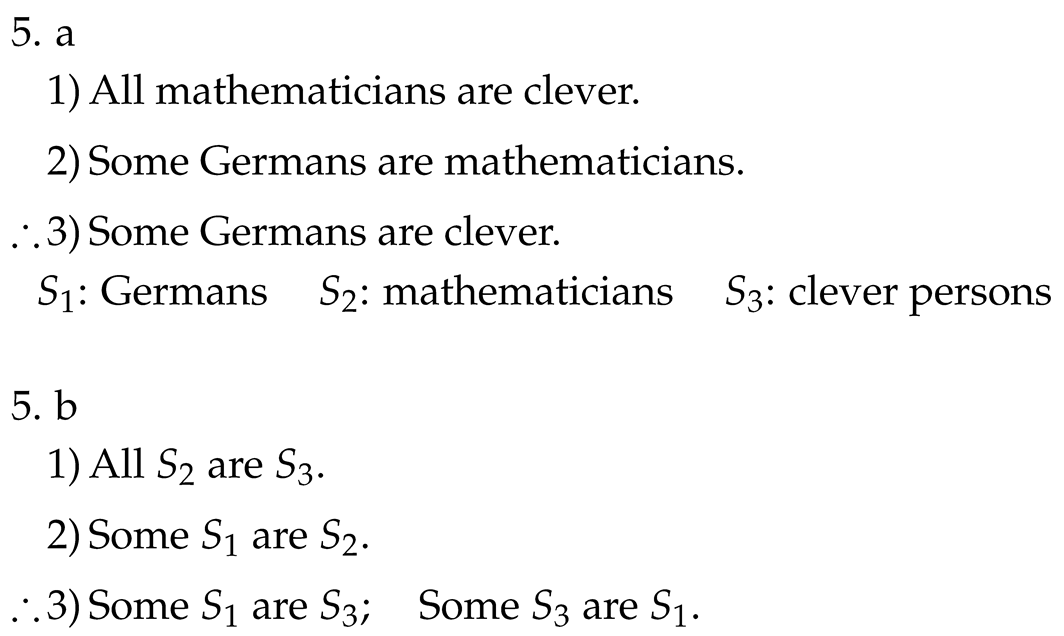

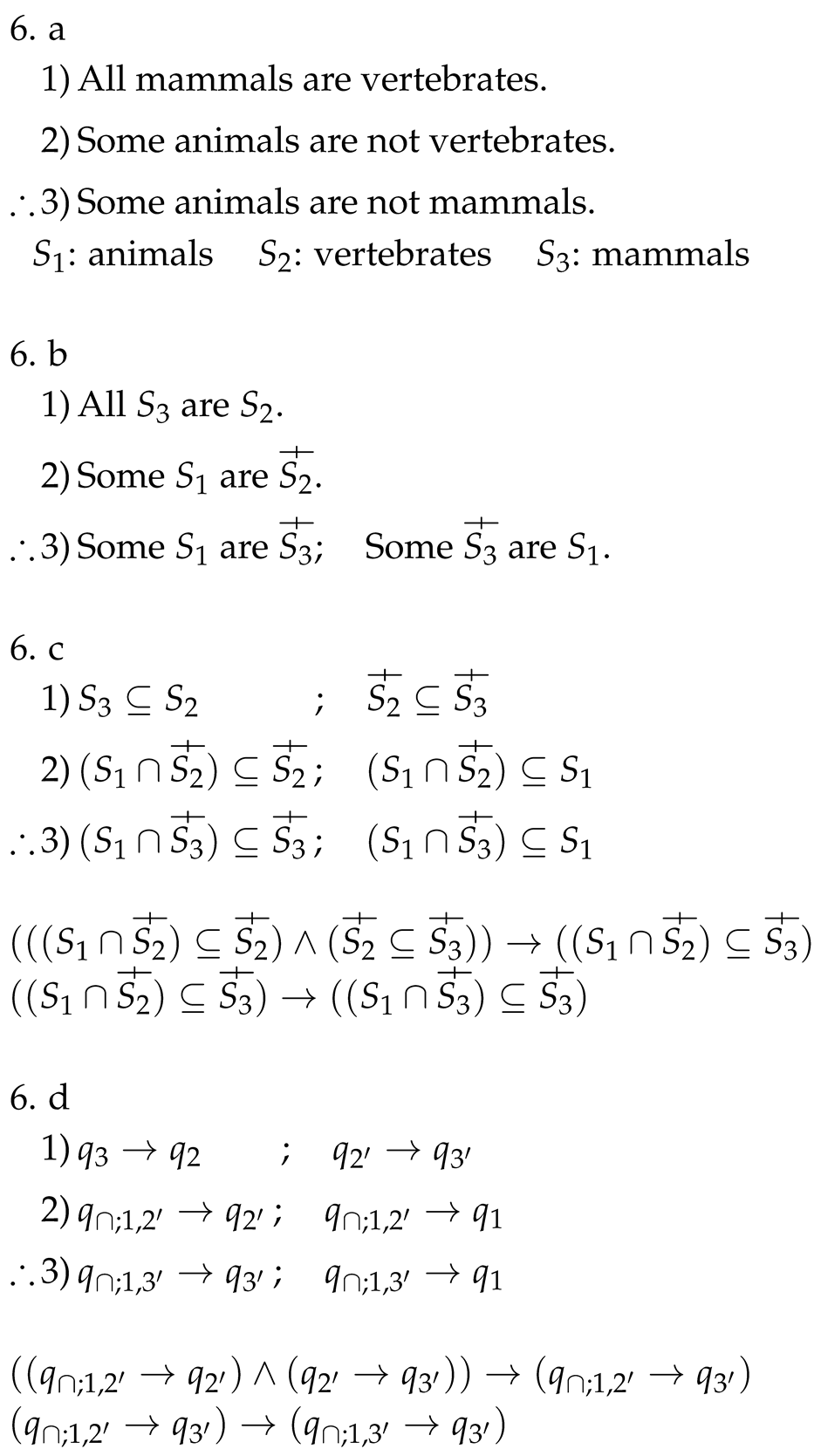

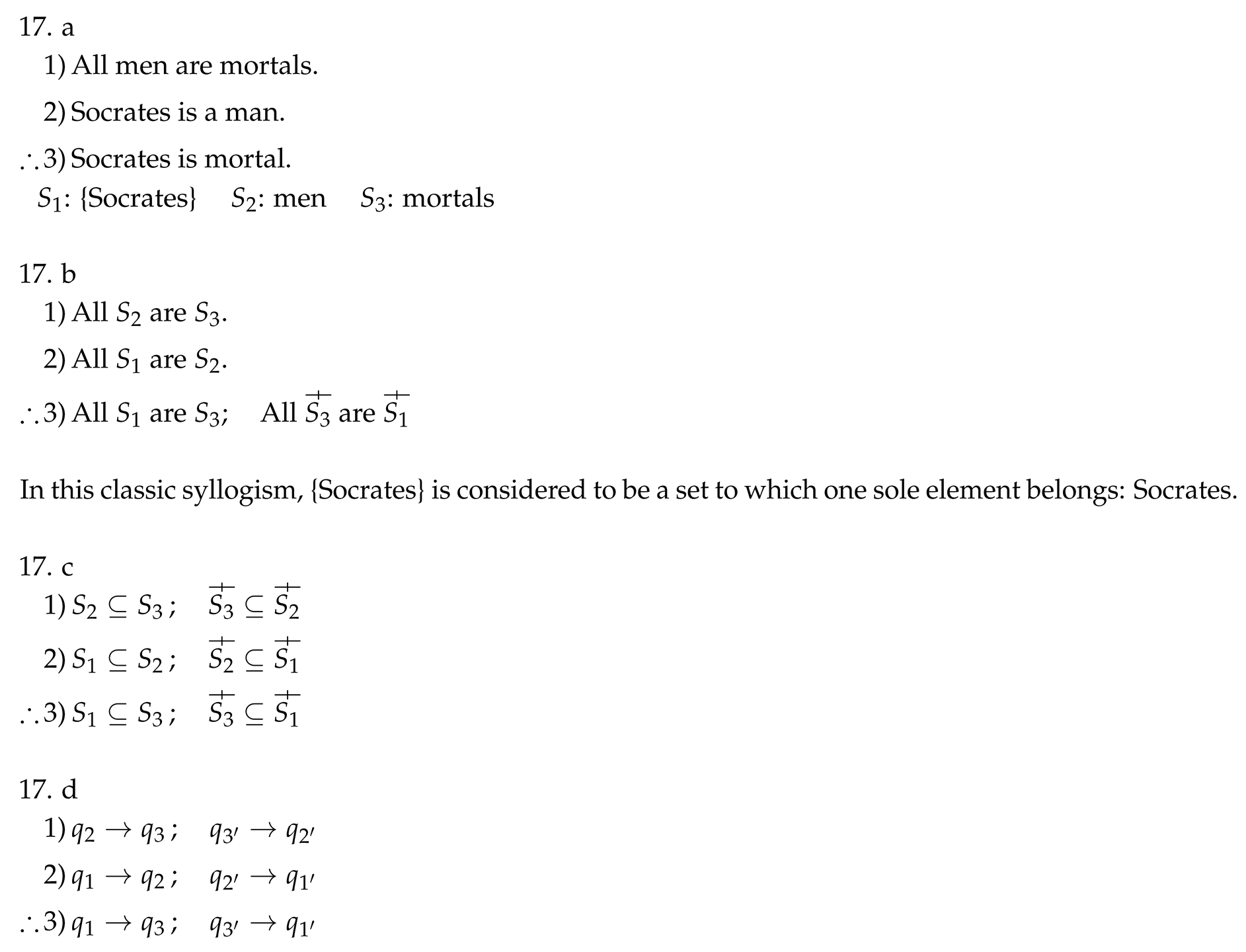

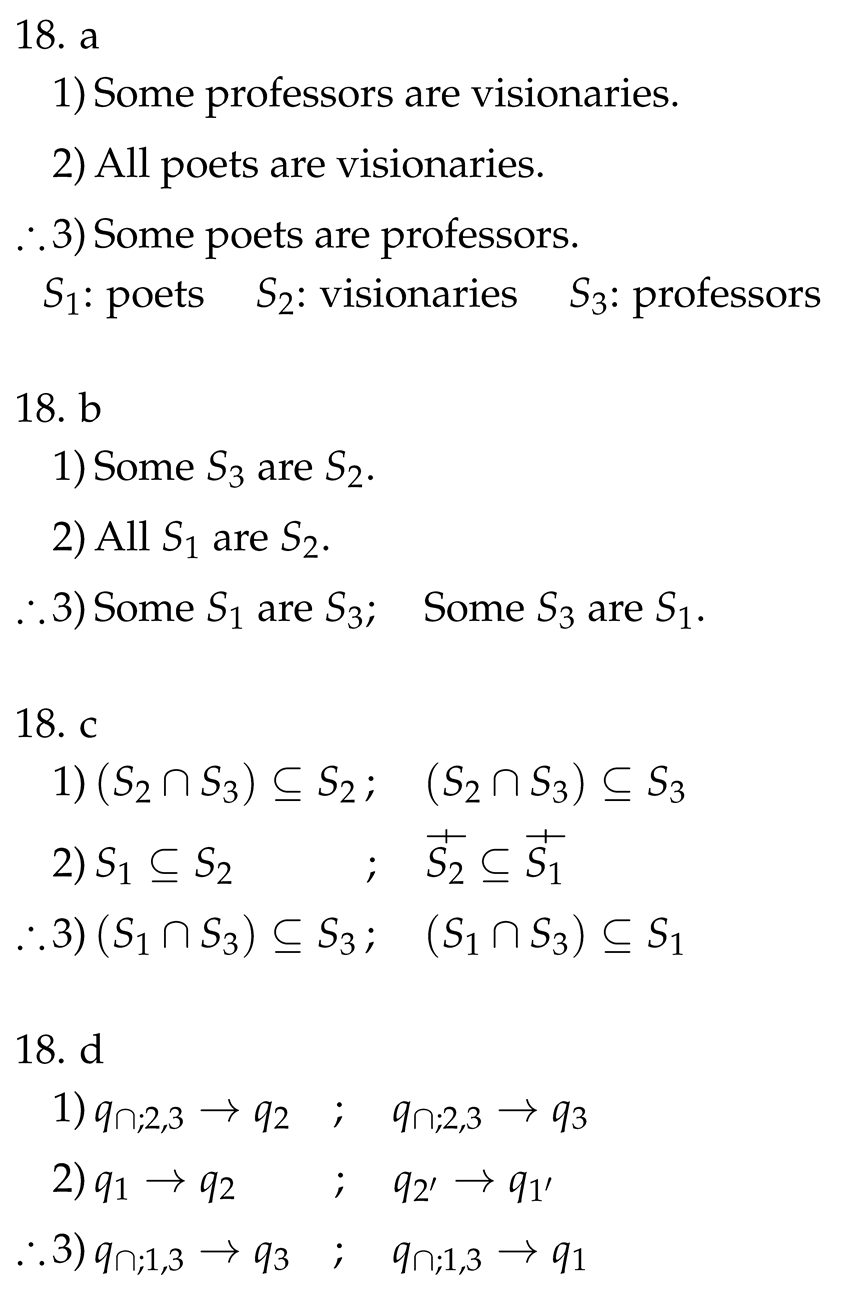

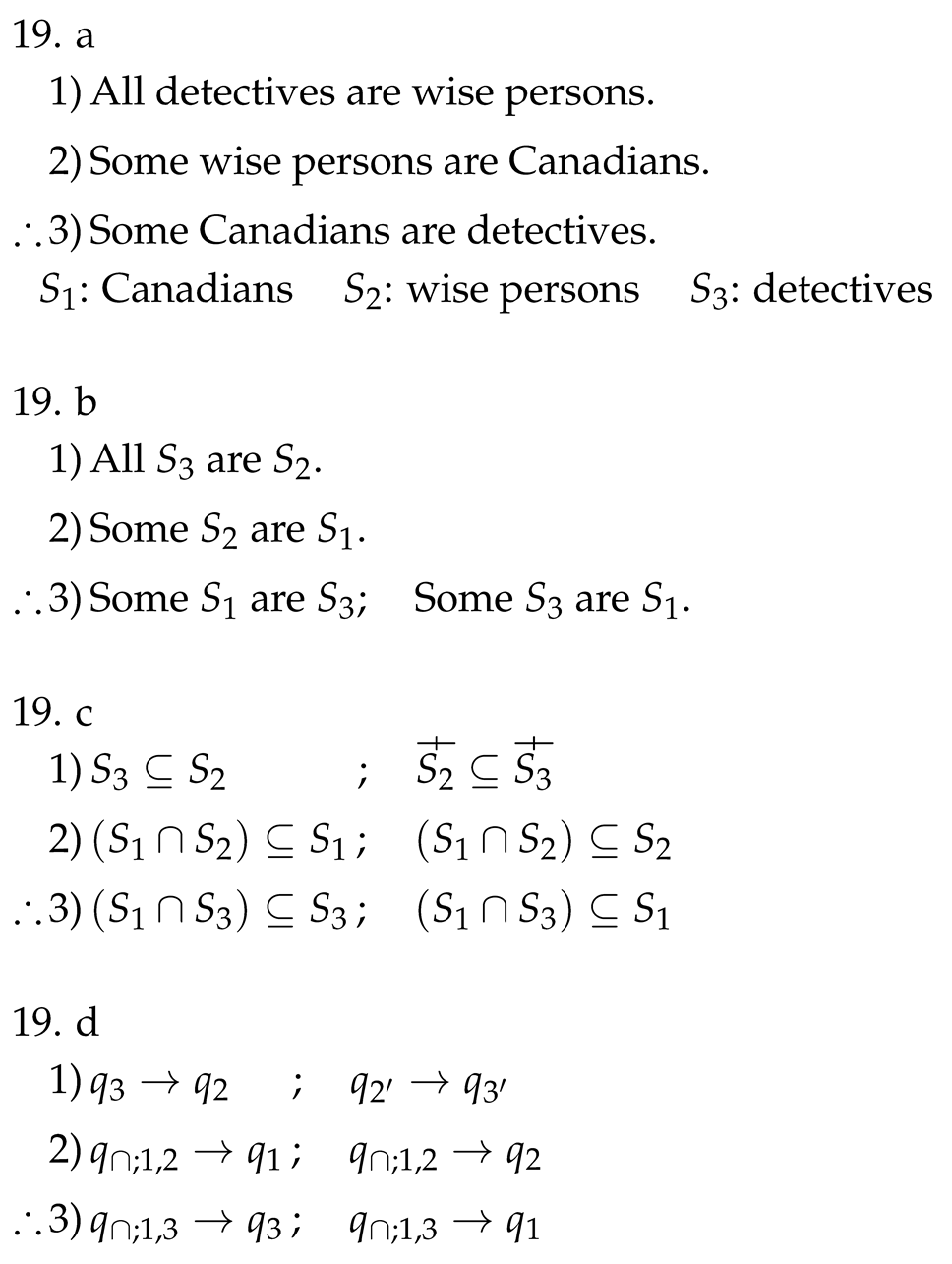

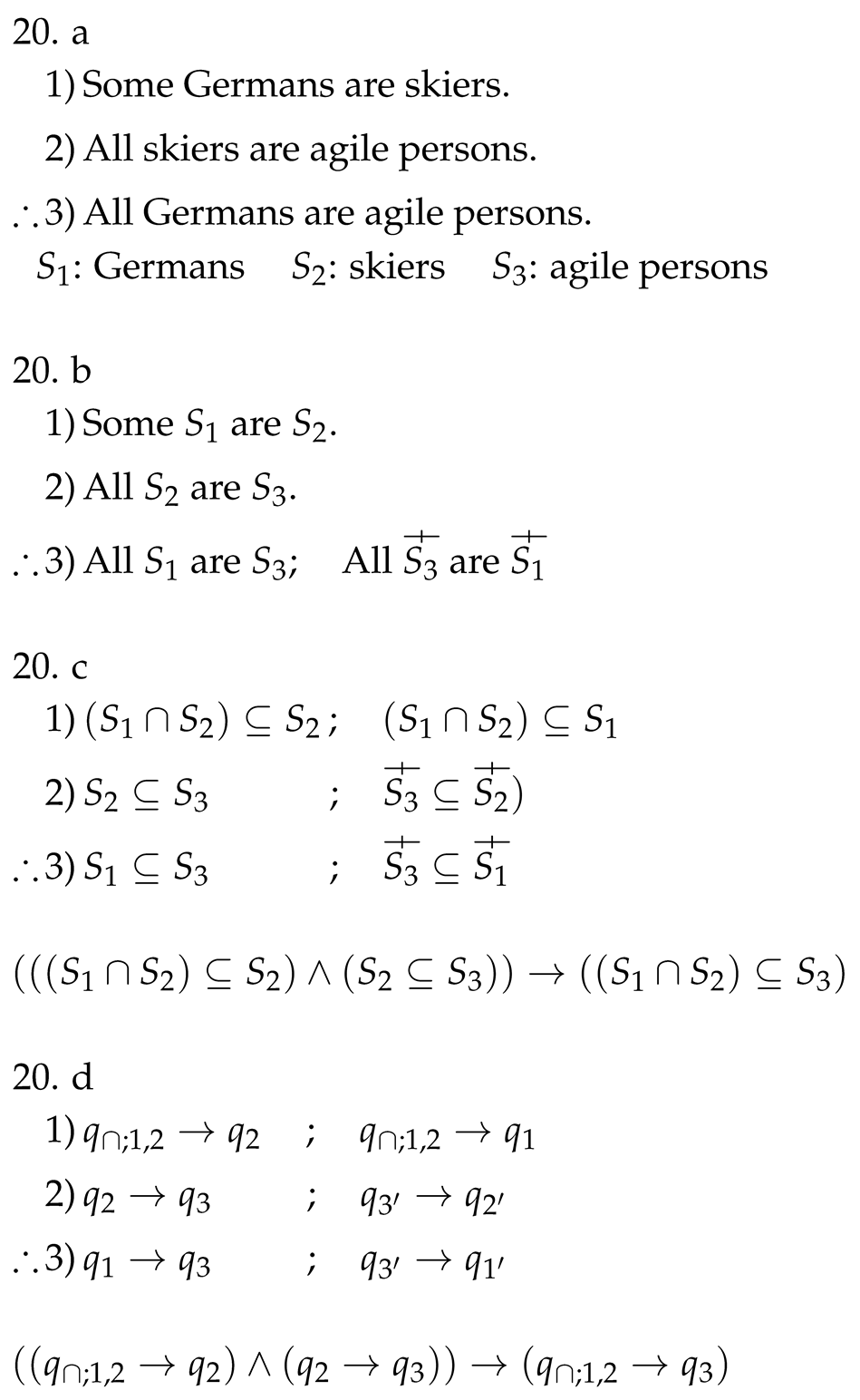

17)).5. Review of Notions Related to Categorical Syllogisms

6. Determining the Validity or Lack of Validity of Categorical Syllogisms

6.1. Additional Results on Set Theory and the SPC

6.2. How to Analyze Categorical Syllogisms

1,

1,  2 and

2 and  3 will also be used to refer to the complements of , and , respectively. Thus, for example, the universal negative categorical proposition “No are ” will be expressed as “All are

3 will also be used to refer to the complements of , and , respectively. Thus, for example, the universal negative categorical proposition “No are ” will be expressed as “All are  2 ”. Likewise, the particular negative categorical proposition “Some are not ” will be expressed as “Some are

2 ”. Likewise, the particular negative categorical proposition “Some are not ” will be expressed as “Some are  2 ”. How the latter two propositions are expressed using, first, set theory symbols, and second, the SPC symbols will be reviewed below:

2 ”. How the latter two propositions are expressed using, first, set theory symbols, and second, the SPC symbols will be reviewed below: 2 ;

2 ;  2 ;

2 ;

2 ;

2 ;  2) ⊆

2) ⊆  2 ;

2 ;

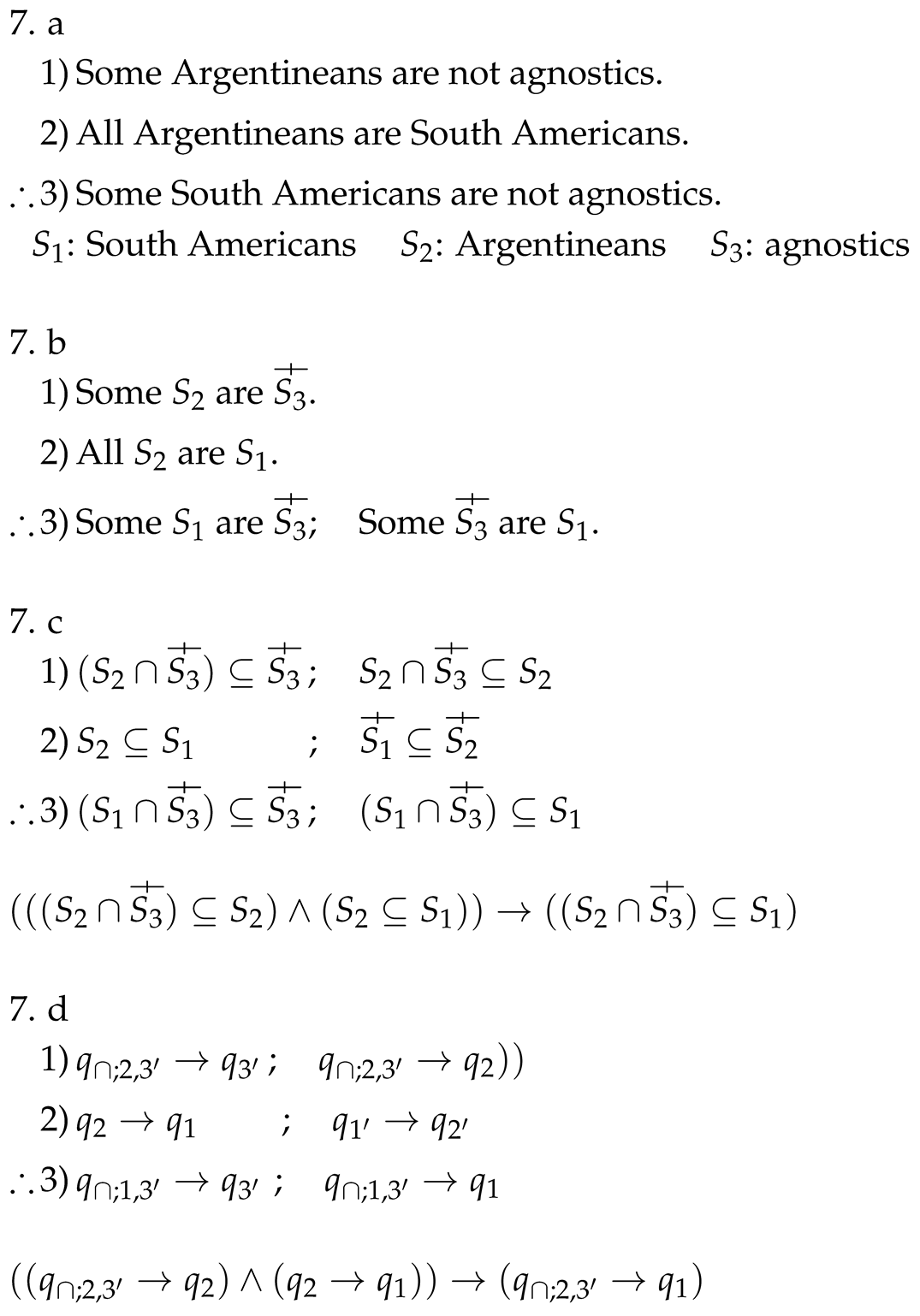

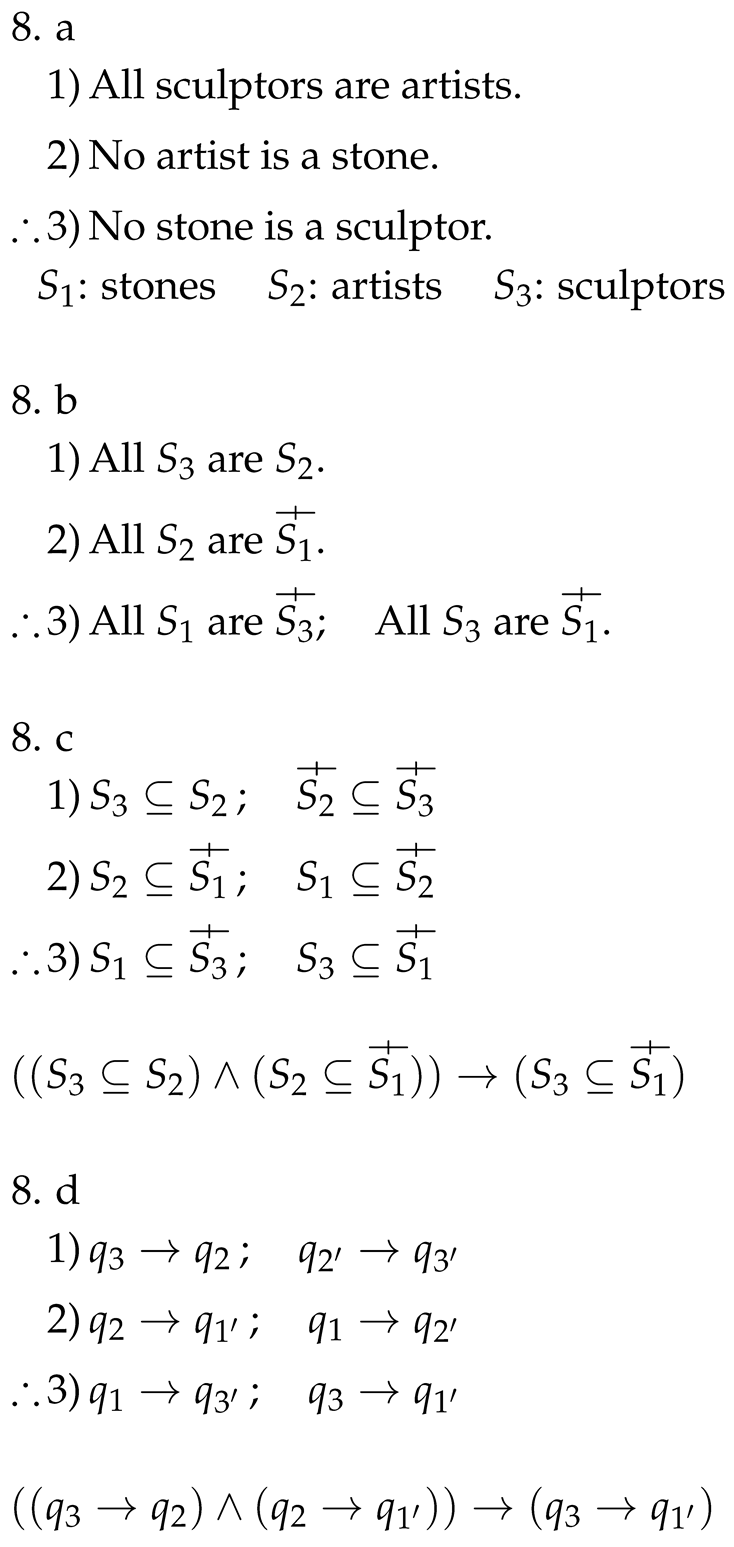

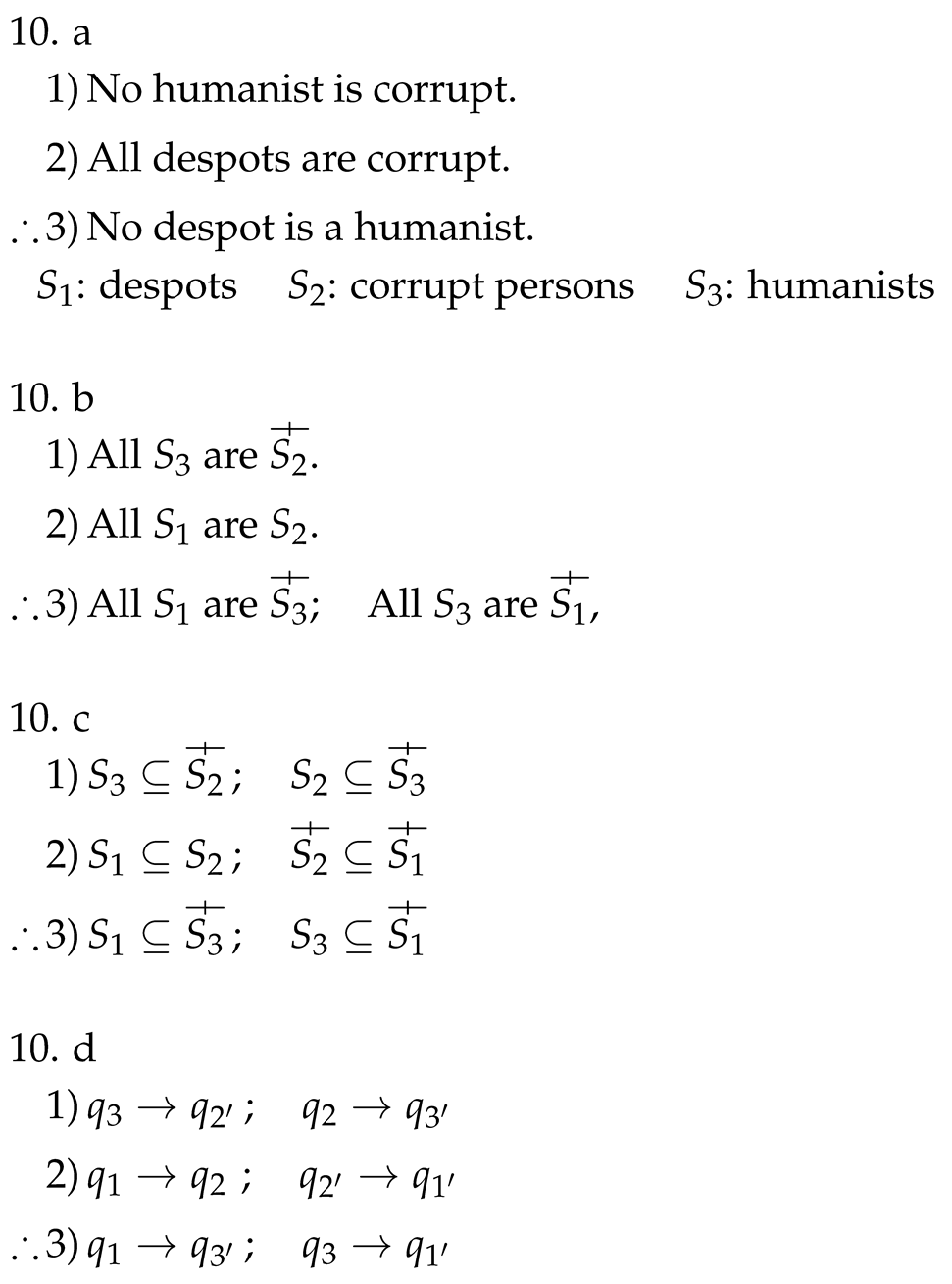

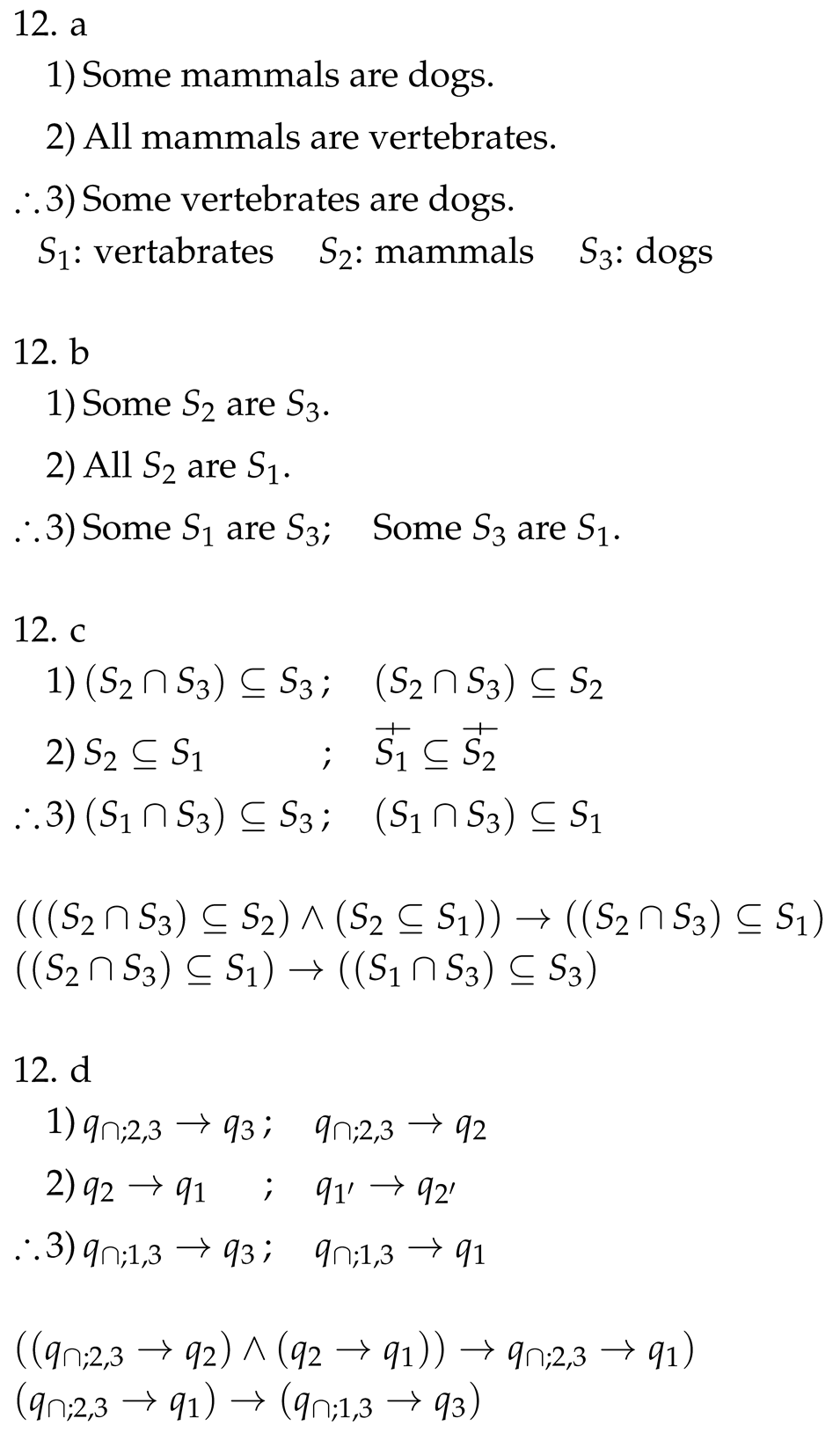

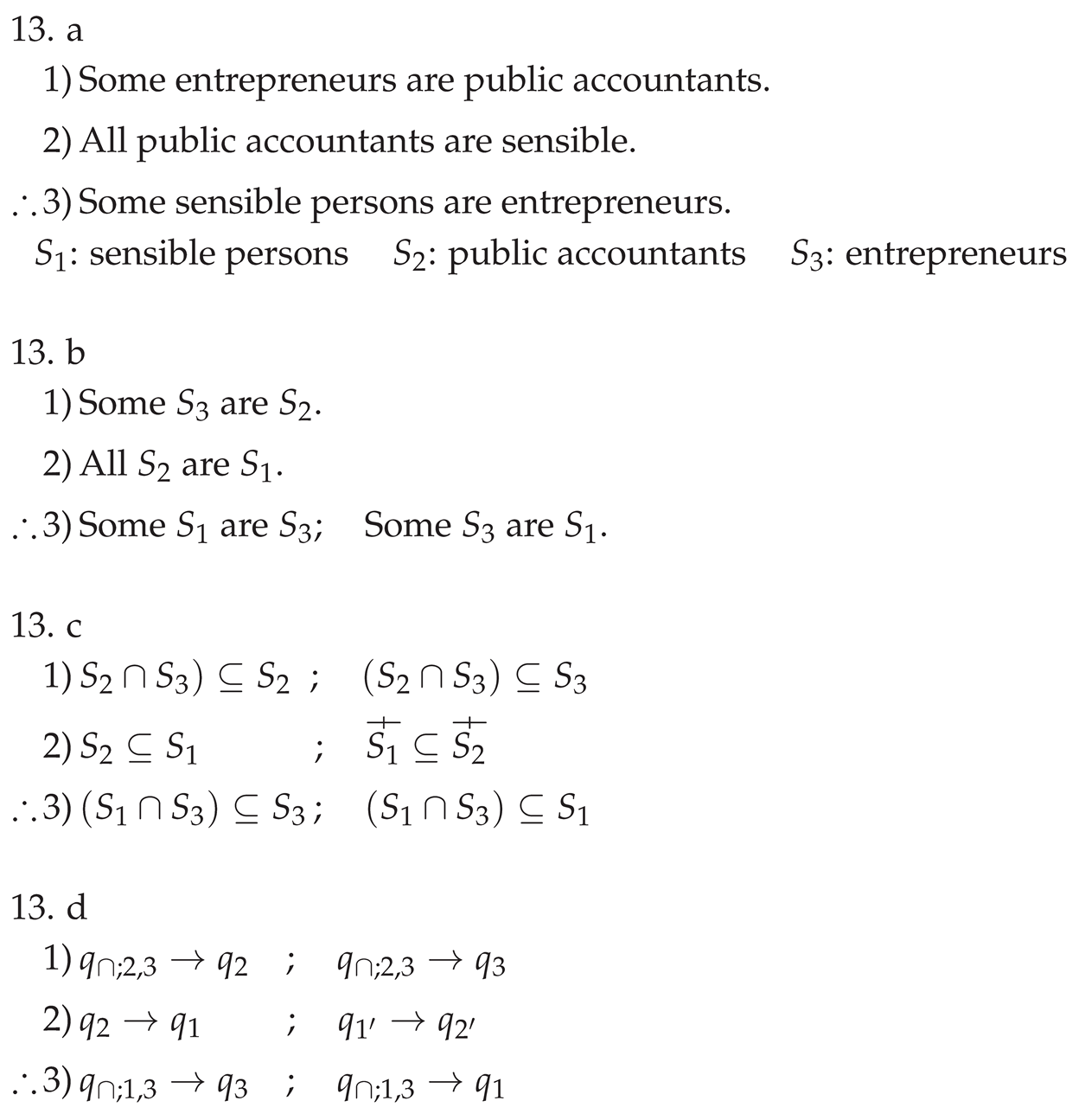

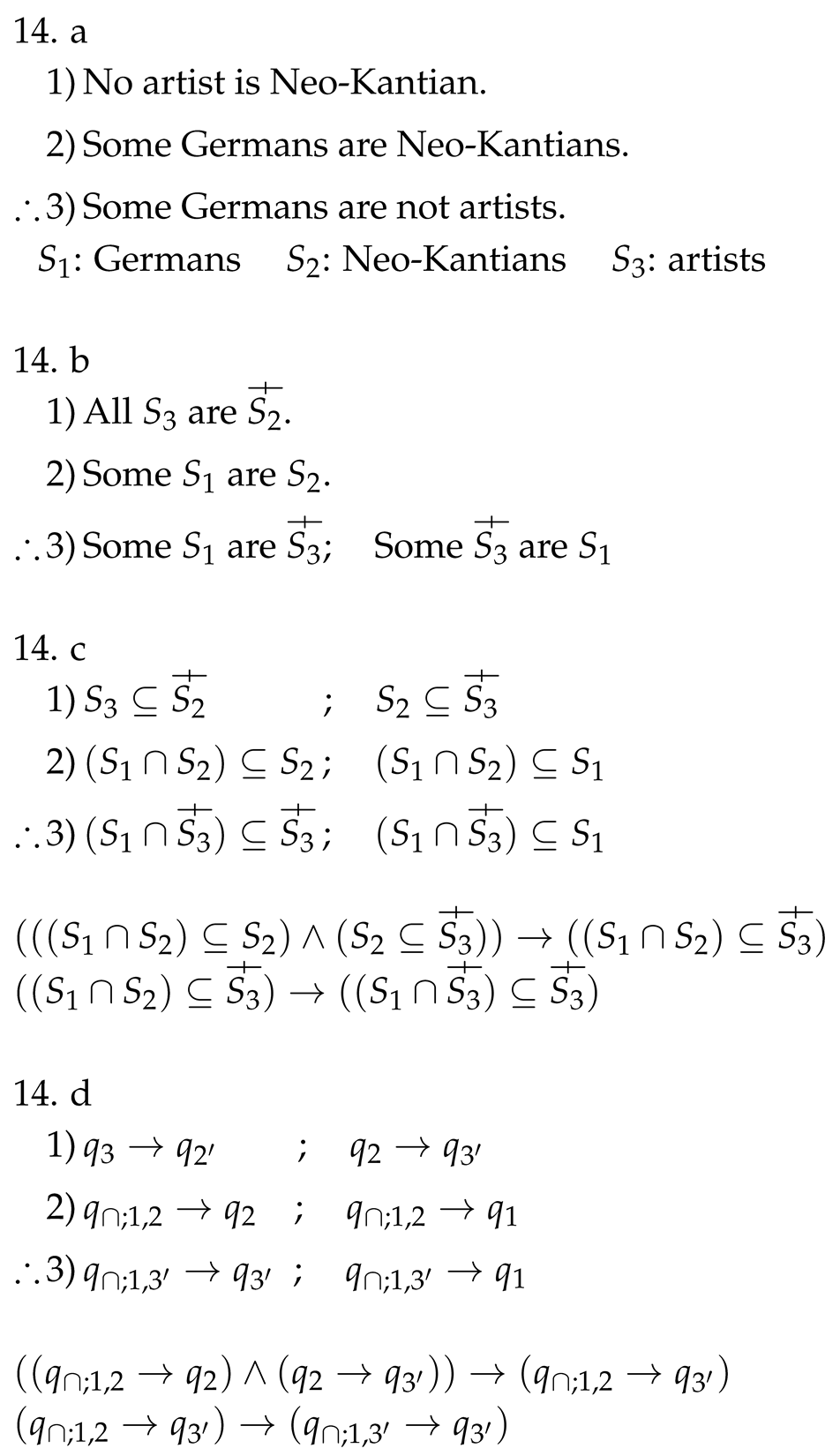

6.3. Determining the Validity, or Lack of Validity, of Diverse Categorical Syllogisms

| : oysters | : beings that can be madly in love | : fossils |

2.

2. 3 ; All S3 are

3 ; All S3 are  1.

1. 2 ; S2 ⊆

2 ; S2 ⊆  3

3

2 ⊆

2 ⊆  1

1

3 ; S3 ⊆

3 ; S3 ⊆  1

1

3)) → (S1 ⊆

3)) → (S1 ⊆  3)

3) 3

and can be interpreted as “All are

3

and can be interpreted as “All are  3”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

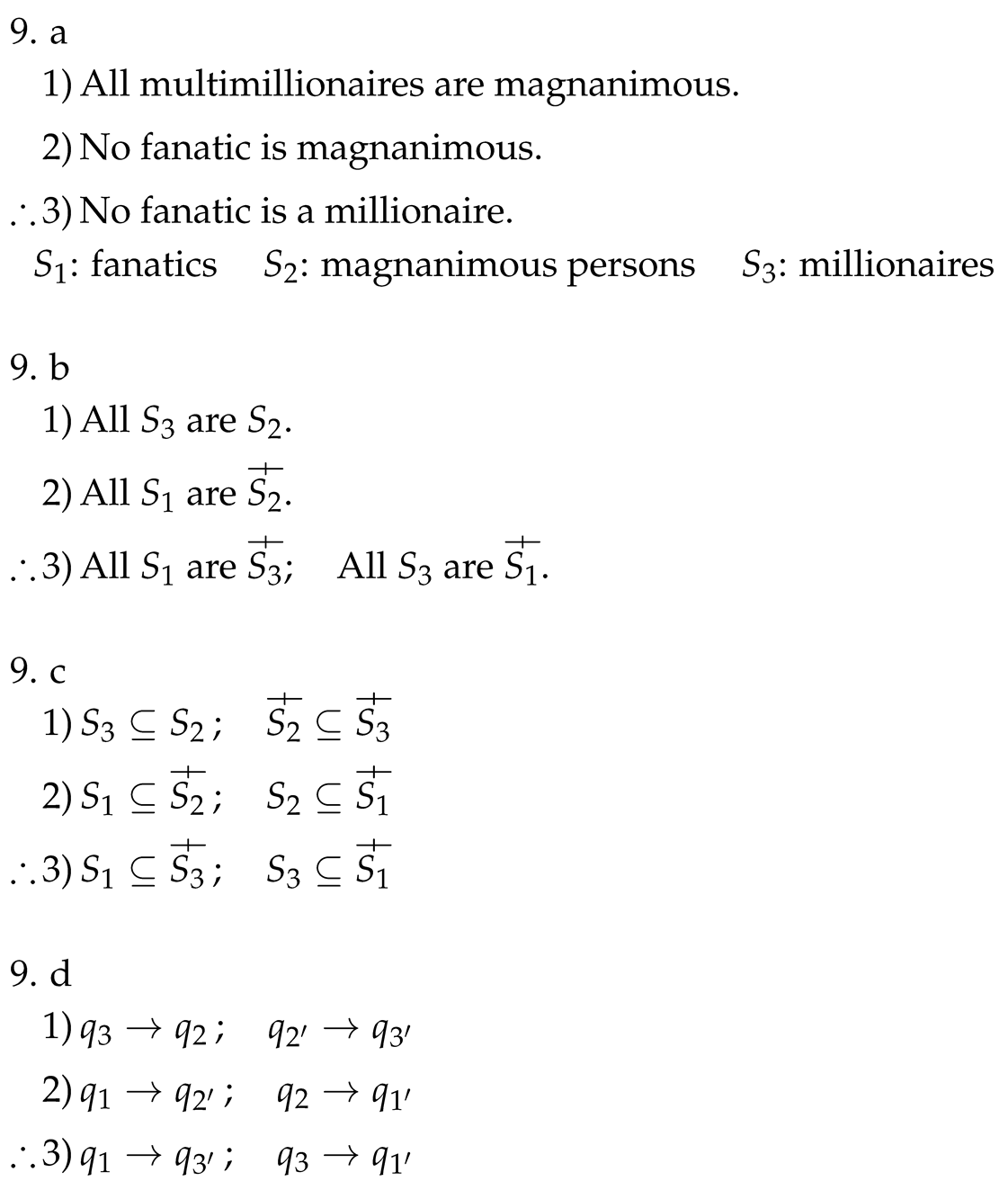

3”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.| : wealthy persons | : engineers | : pragmatic persons |

3⊆

3⊆  2

2

| : French persons | : intellectuals | : superstitious persons |

3.

3. 3; Some

3; Some  3 are S1.

3 are S1. 3 ; S3

3 ; S3  2

2

3)

3)  3 ; (S1

3 ; (S1  3) S1

3) S1

3)) → (S1 ∩ S2) ⊆

3)) → (S1 ∩ S2) ⊆  3

3

3) → (S1 ∩

3) → (S1 ∩  3) ⊆

3) ⊆  3

3

3) ⊆

3) ⊆  3 and can be interpreted as “Some are

3 and can be interpreted as “Some are  3

”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

3

”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

3) ⊆

3) ⊆  3 and can be interpreted as “Some are

3 and can be interpreted as “Some are  3 ”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

3 ”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

3 and can be interpreted as “Some

3 and can be interpreted as “Some  3 are ”, which is equivalent to “Some are

3 are ”, which is equivalent to “Some are  3

”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

3

”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

1 and can be interpreted as “All are

1 and can be interpreted as “All are  1”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

1”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

2

2  1). It was determined that the latter categorical syllogism is valid. Therefore, the syllogism considered in Example 9 is valid.

1). It was determined that the latter categorical syllogism is valid. Therefore, the syllogism considered in Example 9 is valid.

3) ⊆

3) ⊆  3

and can be interpreted as “Some are ”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

3

and can be interpreted as “Some are ”. Therefore, the syllogism is valid.

7. Discussion

References

- Skliar, O., Gapper, S. & Monge, R. E. (2024). A Structural Approach for the Concurrent Teaching of Introductory Propositional Calculus and Set Theory. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex. Translated and edited by G. V. Anrep. Oxford University Press.

- Boakes, R. A. (2023). Pavlov’s Legacy: How and What Animales Learn. Cambridge University Press.

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis. B. F. Skinner Foundation.

- Skinner, B. F. (1988). Recent Issues in the Analysis of Behavior: An Extended Edition. B. F. Skinner Foundation.

- Raven, J., & Raven, J. (2003). Raven Progressive Matrices. In R. S. McCallum (Ed.), Handbook of Nonverbal Assessment. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, pp. 223-237.

- Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. George Braziller.

- Copi, I. M., Cohen, C. & Rodych, V. (2019). Introduction to Logic, 15th ed. Routledge.

- Hurley, P. J. (2015), A Concise Introduction to Logic, 12th ed. Cengage Learning.

- Leary, C. C. & Kristiansen, L. (2015). A Friendly Introduction to Mathematical Logic. Milne Library.

- Goldrei, D. (2017). Classical Set Theory: For Guided Independent Study. Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Cunningham, D. W. (2016). Set Theory: A First Course. Cambridge University Press.

- Jech, T. J. (2013). Set Theory (The Third Millenium Edition). Springer.

- Devlin, K. (1993). The Joy of Sets: Fundamentals of Contemporary Set Theory. 2nd ed. Springer.

- Quine, W. V. (1952; 1982). Section 14. Categorical Statements, Methods of Logic, 4th ed. Harvard University Press, pp. 93-97.

- Deaño, A. (1978). Introducción a la lógica formal. Alianza.

- Skliar, O., Monge, R. E., & Gapper, S. (2015). Using Inclusion Diagrams as an Alternative to Venn Diagrams to Determine the Validity of Categorical Syllogisms. arXiv:1509.00926.

- Skliar, O., Gapper, S. & Monge, R. E. (2023). Classical Bivalent Logic as a Particular Case of Canonical Fuzzy Logic. arXiv:2303.05925.

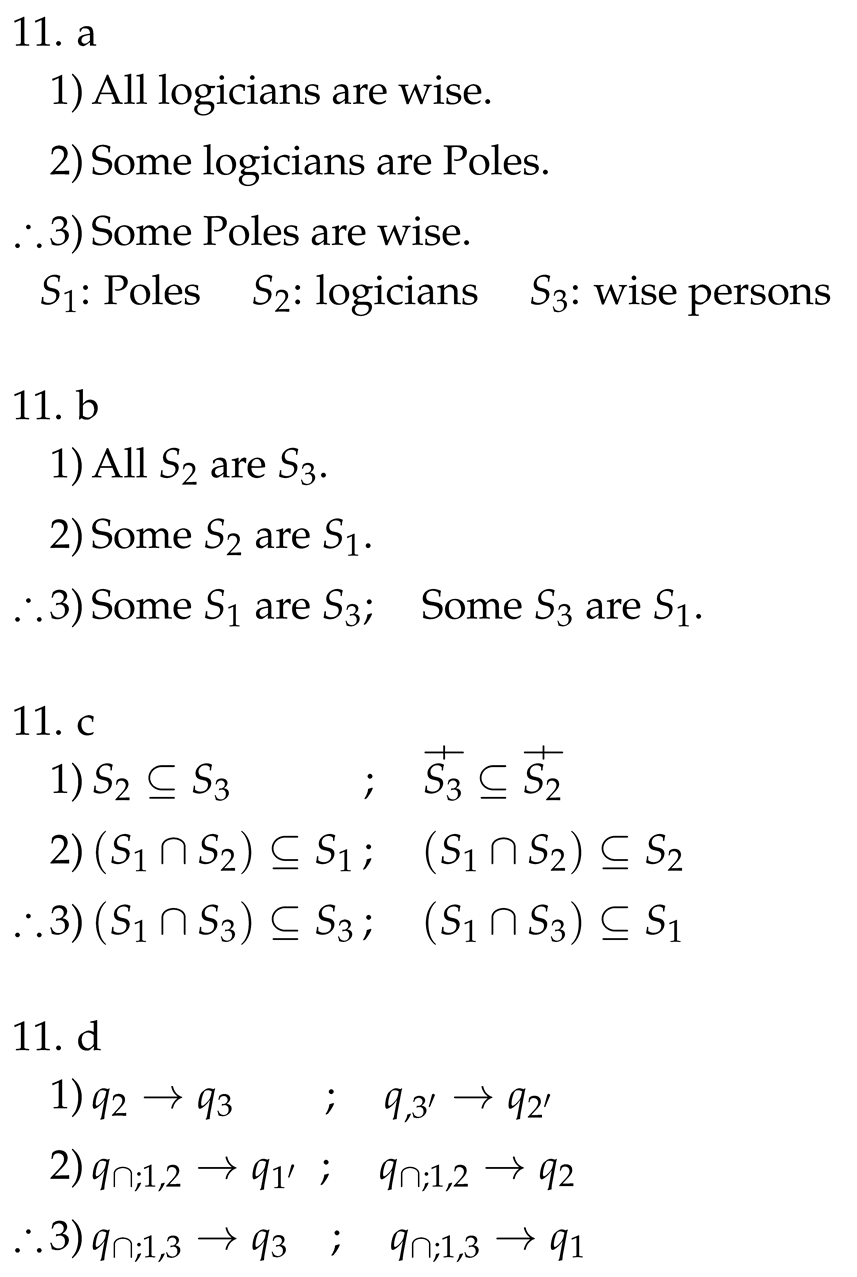

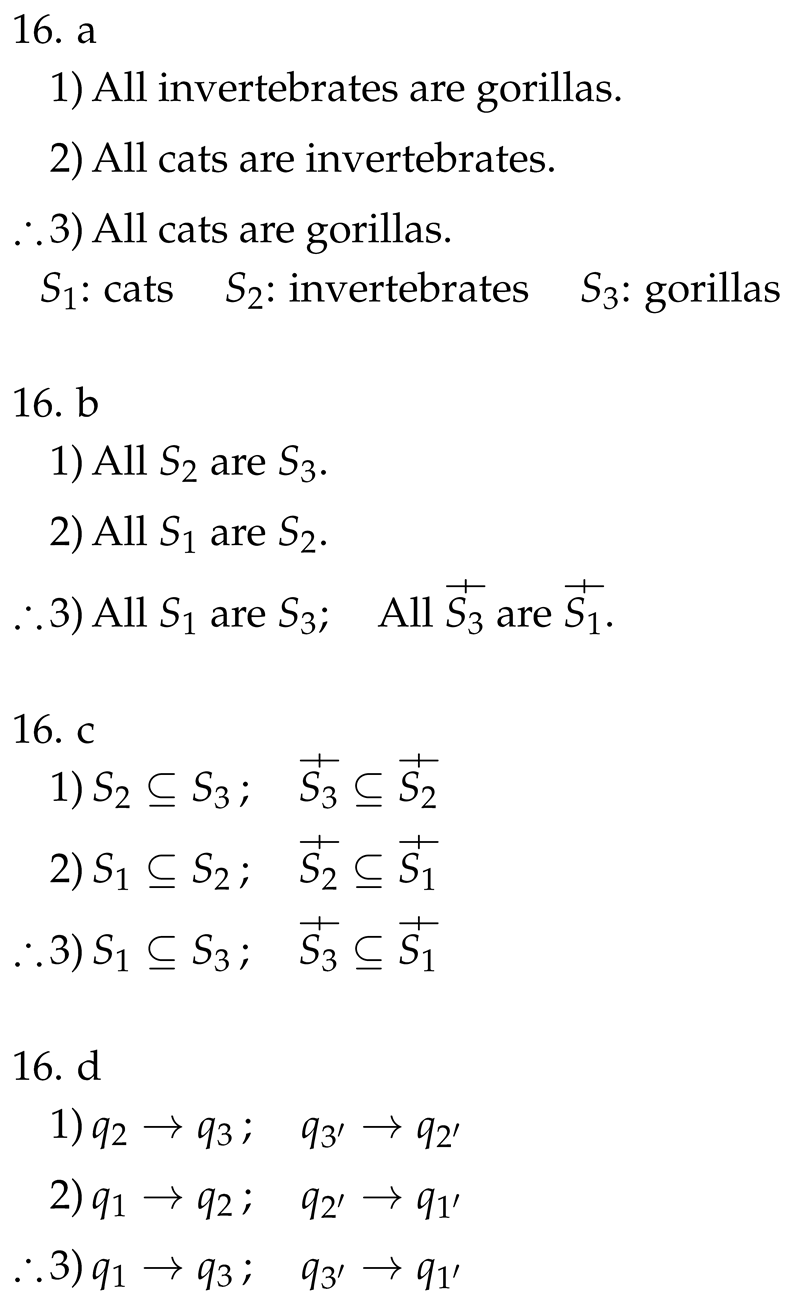

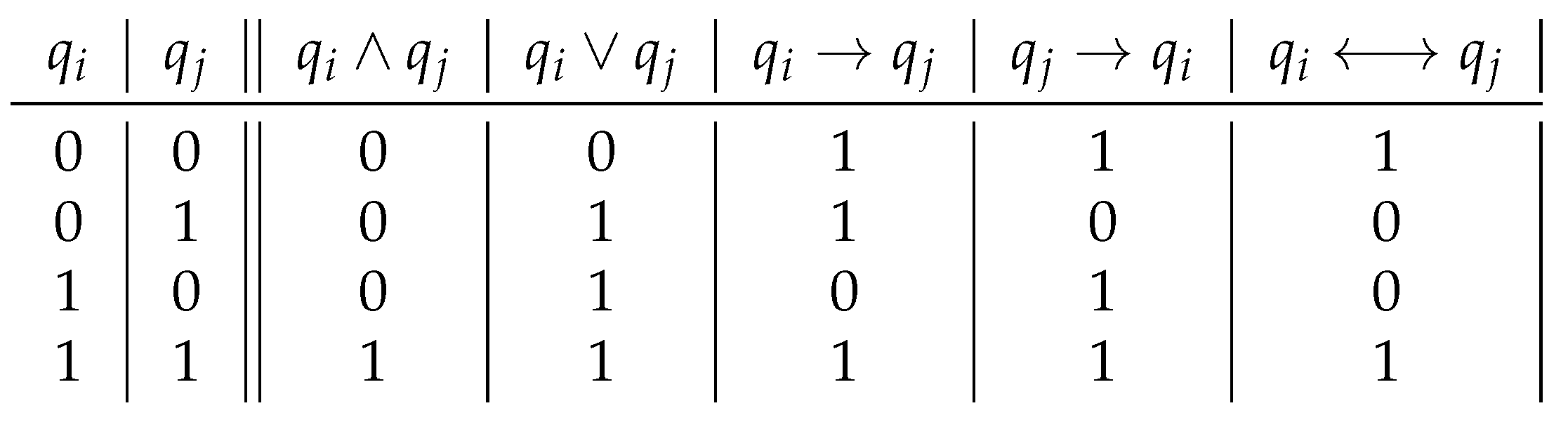

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

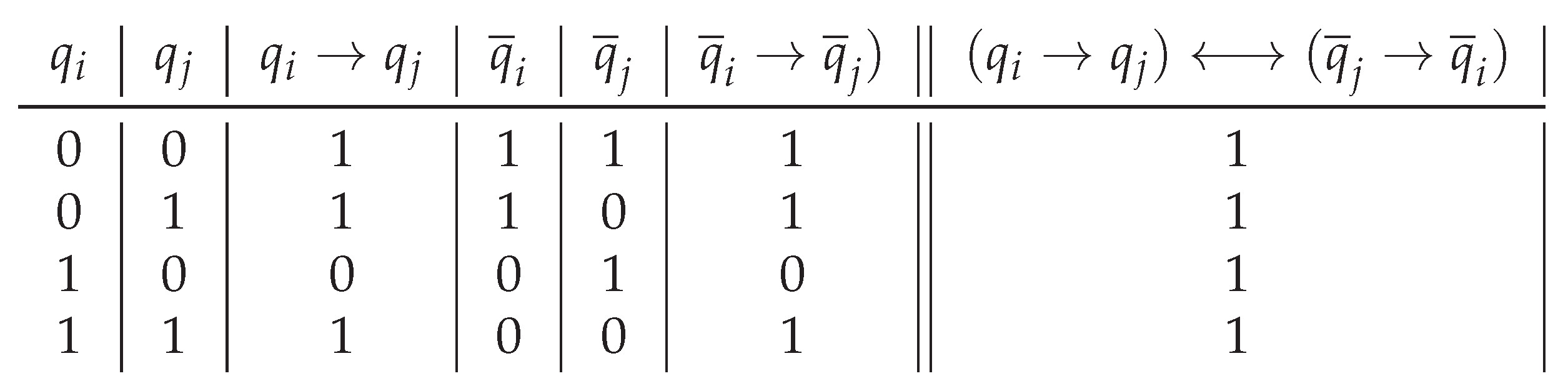

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).