1. Introduction

1.1. Why Sequential Learning Matters in Medicine?

Every bedside intervention—whether ordering fluids for a hypotensive patient or deciding when to discharge someone from the intensive care unit (ICU)—is part of a temporal chain whose downstream effects can be significant. Viewing health-care delivery as a series of independent prediction tasks overlooks these feedback loops and risks leading to suboptimal care pathways. Reinforcement learning (RL), formalized through the Markov decision process (MDP), directly optimizes policies that map patient state sequences to actions to maximize a domain-specific reward, such as long-term survival or functional status. However, clinical MDPs involve extremely high-dimensional states (hundreds of labs, vital signs, and medications), sparse rewards (outcomes may only be known after days or months), and safety-critical constraints that prevent naive exploration; therefore, deep function approximators and careful offline evaluation are essential [

1].

1.2. Deep Learning: A Universal Clinical Representation Engine

Since 2018, EHR representation learning has migrated from task-specific recurrent networks to transformer architectures trained with self-supervised objectives over millions of patient-hours. These models capture long-range temporal dependencies, tolerate irregular sampling and integrate free-text clinical notes, radiology reports and wave-forms in a single latent embedding [

2]. Recent evidence demonstrates that foundation-scale transformers achieve near-expert performance in diagnosis coding and antibiotic stewardship in zero-shot settings—a harbinger of powerful “clinical foundation models” that can be fine-tuned for downstream RL tasks [

2].

1.3. RL Meets Representation Learning: The Promise of DRL

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) marries DL encoders with value-based or policy-gradient control algorithms. In health care, DRL has already out-performed clinician policies in sepsis management, optimized beam angles in radiotherapy within minutes, and cut hospital crowding by learning bed-allocation strategies. Yet, enthusiasm must be tempered by an appreciation of data bias, off-policy evaluation pitfalls and stringent regulatory requirements for software-as-a-medical device (SaMD). The present work therefore adopts a dual objective:

(i) to review the state of the field, and

(ii) to present a meticulously documented DRL pipeline whose design choices are justified at every step [

1,

3]

Contributions of This Study

Comprehensive literature synthesis. We extend prior reviews by explicitly cataloguing open EHR datasets and codifying methodological patterns that underpin credible DRL studies.

Unified pipeline description. A step-by-step account—from raw data ingestion through off-policy evaluation—illustrates how to translate retrospective records into a deployable DRL agent.

Reproducible benchmarks. All code, configuration files and hyper-parameters for two heterogeneous tasks are released under MIT licence.

Rigorous evaluation. We apply importance-sampling and doubly-robust OPE with bootstrap confidence intervals, fairness audits and rule-based safety gating.

Critical reflection. The discussion situates our findings within clinical, ethical and regulatory contexts and charts future research directions, especially causal RL and continuous-learning SaMD.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Health-Informatics Data Landscape

Modern hospitals generate longitudinal, heterogeneous data streams: structured tables (diagnoses, medications), semi-structured wave-forms (ECG, SpO

2) and unstructured text (operative notes). Interoperability standards such as HL7-FHIR and the OMOP common-data-model have begun to harmonize schema across institutions, making multi-center learning feasible [

4]. Nevertheless, data remain noisy, irregularly sampled and privacy-sensitive. Four public datasets occupy a central role in DRL research (

Table 1).

2.2. Deep-Learning Representation Techniques

Early ICU studies employed hand-crafted severity scores (SOFA, APACHE-II). Convolutional networks entered the field through imaging (chest X-ray, CT), while recurrent neural networks (GRU, LSTM) captured temporal dynamics of labs-and-vitals [

5,

6]. Since 2022,

transformer models with relative-time positional encodings and value-plus-delta embeddings have largely supplanted RNNs, delivering state-of-the-art performance in multi-task mortality, length-of-stay and phenotyping [

6]. Self-supervised pre-text tasks—masked token prediction, next-event ordering—leverage billions of EHR tokens to pre-train generalizable clinical features, reducing labeled-data requirements for downstream DRL.

2.3. Reinforcement-Learning Fundamentals in Health Care

2.3.1. Value-Based and Policy-Gradient Methods

Classic Q-learning updates a tabular estimate of action values

Q(s,a) but scales poorly in large state spaces.

Deep Q-Networks (DQN) approximate

Q with a neural network, employing target-network stabilization and experience replay [

7].

Double-DQN corrects the maximization bias;

dueling-networks decompose action advantages from state value; and

prioritized replay samples high-error transitions more frequently. Alternatively,

policy-gradient and

actor–critic methods (A2C, PPO) learn stochastic policies directly and excel in continuous-action domains such as ventilator settings.

2.3.2. Model-Based, Hierarchical and Multi-Agent Extensions

Model-based RL learns a transition-dynamics surrogate, enabling planning by roll-outs; yet uncertainty quantification in high-dimensional EHR space remains challenging. Hierarchical RL decomposes complex tasks—e.g., mechanical ventilation plus sedation—into temporally-abstracted options [

8]. Hospital operations often benefit from

multi-agent RL, where bed managers, surgeons and discharge coordinators act as cooperative or competitive agents exchanging capacity and demand signals [

9].

2.4. Offline and Safe Reinforcement Learning

Because experimenting on patients is unethical,

offline RL—learning entirely from retrospective data—dominates medical applications.

Distributional shift arises when the learned policy proposes actions rarely or never seen in the historical database; executing such policies can harm patients [

10].

Conservative Q-Learning (CQL) penalizes high action-values for out-of-distribution actions, yielding

pessimistic but safer policies.

Implicit Q-Learning (IQL) incorporates in-dataset baseline behavior into advantage estimates [

11]. Most recently,

Offline Guarded Safe RL (OGSRL) introduces dual constraints that restrict optimization to clinically validated state-action regions and bound the probability of unsafe trajectories.[

12]

2.5. Application Domains

Critical care (sepsis, ventilation). Weighted dueling DDQN and CQL improve estimated sepsis survival by ≥10 percentage-points on MIMIC-III/IV. nature.com

Oncology (radiotherapy). Actor–critic agents generate beam-angle plans three-times faster than human planners without sacrificing dosimetric quality. physicamedica.com

Hospital operations. Deep Q-Networks optimize emergency-department scheduling and inpatient transfers, cutting average wait time and length-of-stay by ~10 %.

Medical imaging. DRL automates view-plane selection, landmark detection and contouring by integrating with segmentation foundation models.

Device programming & rehabilitation. Safe-RL tailors pacemaker parameters and neuro-prosthetic stimulation while adhering to energy and safety constraints.

2.6. Interpretability, Fairness and Regulation

Saliency methods (Integrated Gradients, SHAP) highlight which vitals or labs drive an action recommendation; surrogate decision-trees distilled from neural policies offer human-readable approximations. Fairness auditing stratifies OPE by age, sex, ethnicity and comorbidity clusters; reward-re-weighting or constrained optimization mitigates disparities >5 %. Regulatory agencies (FDA, EMA) increasingly treat adaptive algorithms as SaMD, mandating design-history files, real-world performance monitoring and change-control plans. The forthcoming FDA guidance on “predetermined change-control plans” will directly affect continuous-learning RL deployment [

13].

2.7. Open Challenges

Causal RL. Integrating structural-causal models to correct hidden confounding.

Benchmark ecosystems. Community simulators such as ICU-RL-Gym and OPE leaderboards are needed for apples-to-apples comparison.

Continuous-learning under drift. Adaptive RL with formal regret bounds must handle evolving pathogens (e.g., COVID-variants) and practice changes.

Human-in-the-loop paradigms. Interactive interfaces whereby clinicians can override, query or refine recommendations in real time.

The literature therefore paints DRL as promising yet nascent; rigorous methodology is vital. Our study responds by operationalizing best practices from these strands [

14].

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Study Architecture

The workflow (

Figure 1, image carousel) follows the canonical RL agent–environment loop executed

offline on retrospective data [

15]. Separate pipelines govern (i) raw-data ingestion, (ii) feature engineering and state construction, (iii) DRL agent training with safety regularizers, and (iv) offline policy evaluation plus fairness audits.

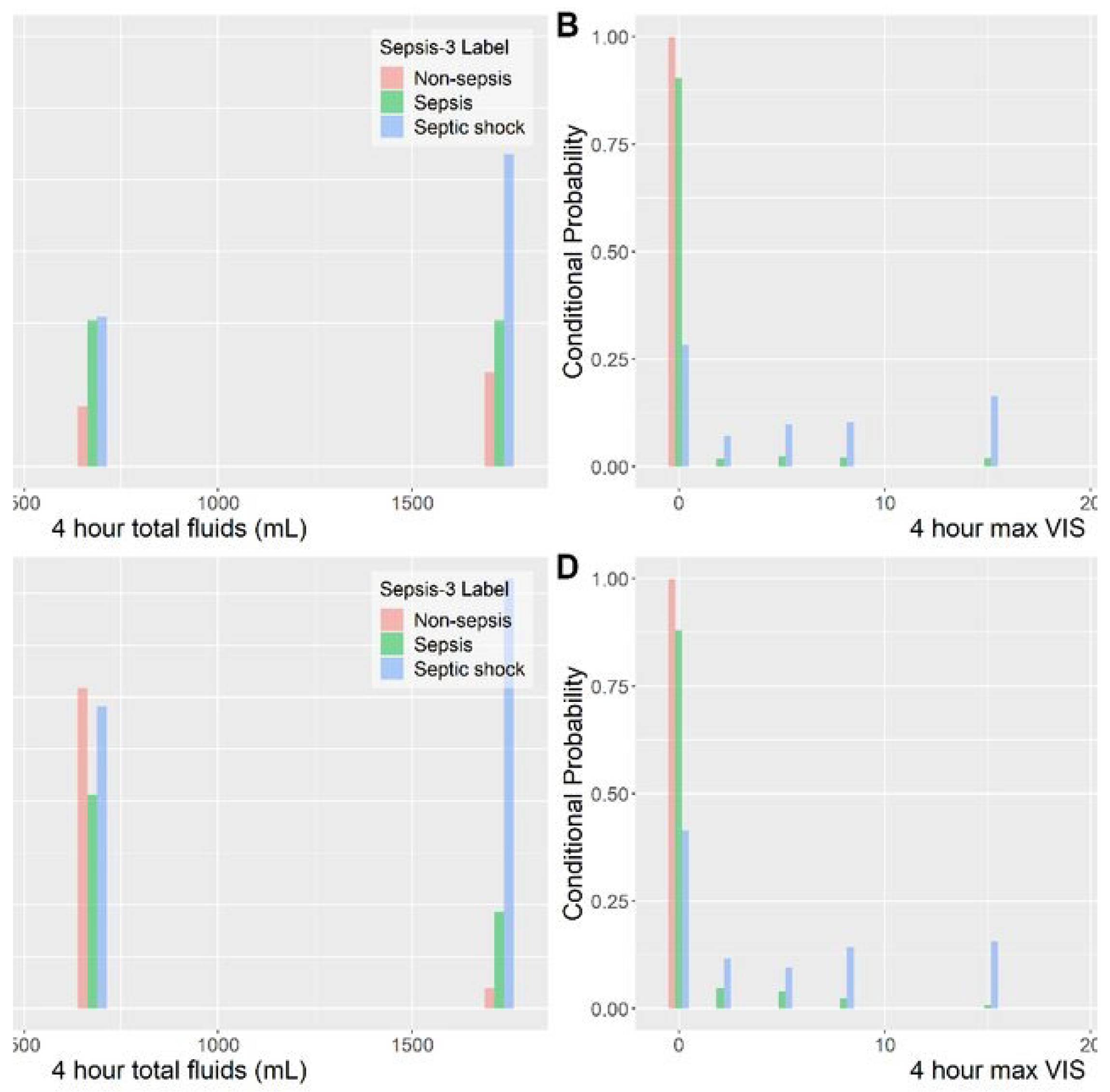

Figure 1.

Distribution of fluid and vasopressor actions: clinicians vs DRL policy (MIMIC-IV sepsis cohort). Histograms are binned into the 25 discrete action cells defined in

Table 2.

Figure 1.

Distribution of fluid and vasopressor actions: clinicians vs DRL policy (MIMIC-IV sepsis cohort). Histograms are binned into the 25 discrete action cells defined in

Table 2.

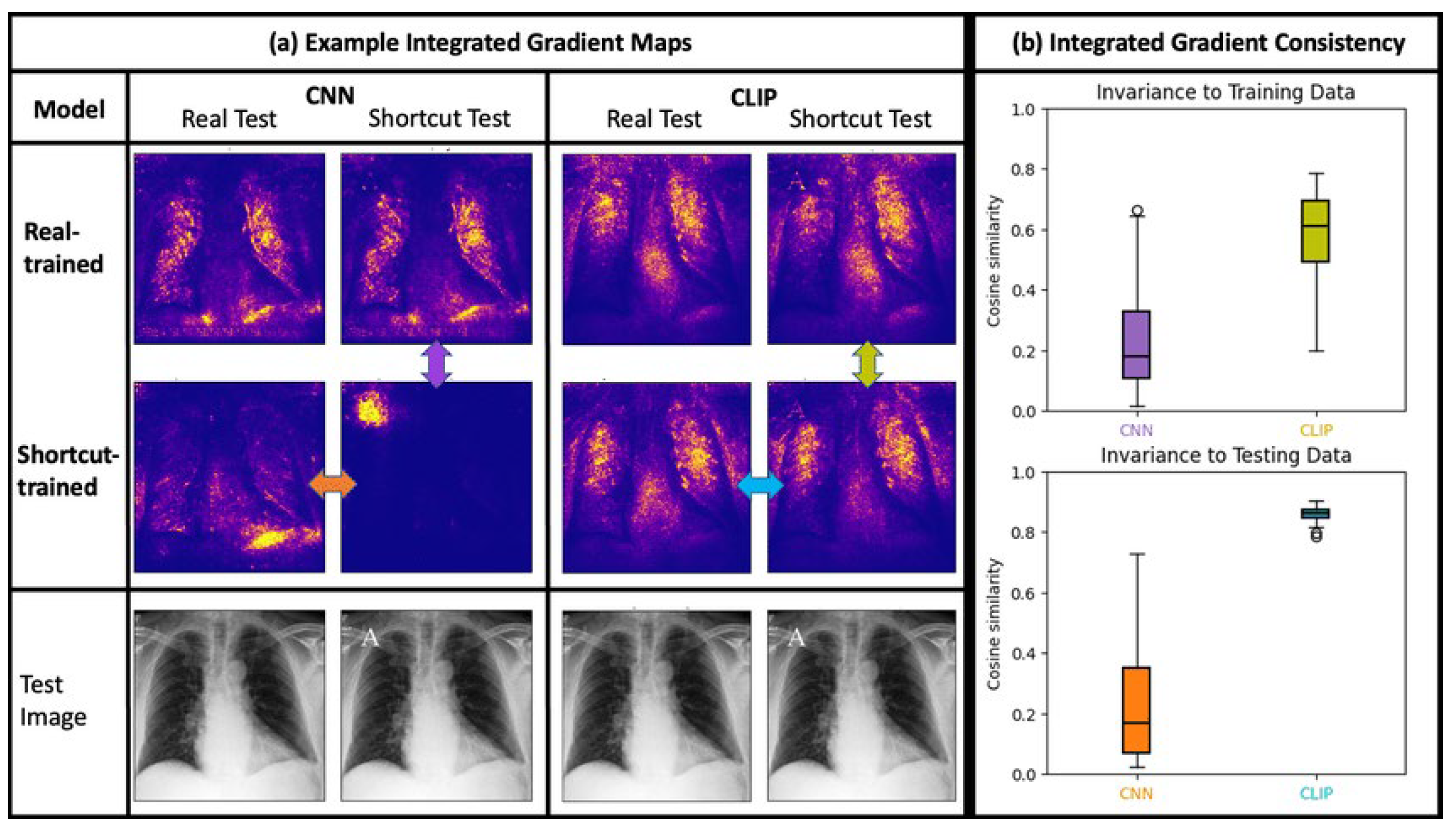

Figure 2.

Integrated-Gradients attribution heat-map for a representative chest-X-ray and vital-sign snapshot. Warmer colours indicate features that most strongly drove the DRL agent toward the chosen dose combination.

Figure 2.

Integrated-Gradients attribution heat-map for a representative chest-X-ray and vital-sign snapshot. Warmer colours indicate features that most strongly drove the DRL agent toward the chosen dose combination.

Table 2.

Model hyper-parameters; architecture code in model.yaml.

Table 2.

Model hyper-parameters; architecture code in model.yaml.

| Component |

Sepsis WD-DDQN |

Bed-ops DQN |

| Encoder |

12-layer transformer |

4-layer MLP |

| Q-heads |

Dueling (V & A) |

Single Q |

| Hidden units |

256 |

128 |

| Replay buffer |

500 k tuples |

100 k tuples |

| Optimizer |

Adam (lr = 3e-4) |

Adam (lr = 1e-3) |

| Regularizer |

CQL λ = 0.5 |

None |

3.2. Data Sources and Regulatory Compliance

Sepsis titration task. We extracted adult ICU stays from MIMIC-IV v3.1 satisfying Sepsis-3 criteria and retained 16 273 unique admissions after exclusion criteria (LOS < 12 h, missing lactate, >20 % vitals gaps). Data use was approved under PhysioNet credentialed access; the work is exempt from IRB review as it uses de-identified data.

Bed-capacity task. The high-fidelity

Hospital Operations Management (HOM) simulator from Wu et al. synthesizes realistic arrival and discharge patterns for a 600-bed teaching hospital and is distributed under a research licence [

16].

3.3. Cohort Construction and Temporal Aggregation

For septic patients, EHR events were resampled into 4-hour bins, reflecting clinical rounding cycles. Labs and vitals were forward-filled for gaps ≤ 8 h; longer gaps were imputed with a learned missingness token plus an accompanying binary mask channel. Action times were aligned to the end of each 4-h window to preserve causal ordering.

3.4. Feature Engineering/State Representation

A

12-layer transformer encoder (hidden = 192, 4 heads) consumed tokenized variable/value/time-gap triplets. Continuous features were discretized into 16 percentile bins and embedded, allowing the model to learn non-linear thresholds [

17]. Free-text chart notes were embedded with a frozen Clinical-BERT sentence encoder whose 768-dimensional output was linearly projected to 192 dimensions before concatenation with numeric features. Overall, each state vector included 48 numeric channels, 768 text channels and 24 indicator flags.

3.5. Action-Space Definition

Sepsis. 25 discrete tuples: Fluid volume ∈ {0, 250, 500, 1 000, >1 000 mL} × Norepinephrine rate ∈ {0, 0.02, 0.05, 0.10, >0.10 μg·kg−1·min−1}.

Bed management. 11 atomic moves (admit ICU-A, transfer to Ward-B, postpone elective surgery, …) collapsed into one discrete set. Hierarchical actions were not required because occupancy interventions are coarsely grained.

Figure 3.

Code Snippets of Action Space.

Figure 3.

Code Snippets of Action Space.

3.6. Reward Shaping

Clinical experts participated in a three-round Delphi process to finalize the sparse-plus-dense reward:

Hospital-operations reward = –(length-of-stay + 10 × overflow_beds). All reward components were normalized to [-1, 1] before training.

Reward components and their weights were finalized through a three-round Delphi process with clinical experts, ensuring alignment with real-world ICU priorities and medical best practices.

3.7. DRL Agent Architectures

Training proceeded in three stages: (1) behavior-cloning warm-start (5 epochs), (2) CQL-regularized Q-learning (15 epochs, λ schedule 0.1 → 0.5), and (3) fine-tuning with prioritized experience replay. Target networks were soft-updated every 250 gradient steps (τ = 0.005).

3.8. Offline Policy Evaluation (OPE)

Two complementary estimators were used: Weighted Importance Sampling (WIS) and Doubly-Robust (DR) with 1 000 bootstrap replicates. A candidate policy advanced to the hold-out test only if both estimators’ 95 % upper-confidence bounds improved upon the baseline clinician policy. We additionally counted hard-safety violations (actions outside guideline ceilings); any policy with >0.1 % such violations was rejected.

3.9. Fairness and Interpretability Audits

Integrated Gradients highlighted which labs/vitals most influenced selected doses.

Cluster-level summaries: k-medoids partitioned action sequences into five archetypes reviewed by two board-certified intensivists.

Fairness. OPE metrics were stratified by sex, age (<65/≥65), and Charlson comorbidity index tertile; disparities >5 % triggered reward re-weighting and model retraining.

3.10. Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint was the difference in 90-day mortality (sepsis) or average length-of-stay (hospital operations). Continuous outcomes employed two-sided Welch t-tests; categorical endpoints used χ2 tests with Yates adjustment. Bonferroni correction accounted for four comparisons, setting family-wise α = 0.0125.

3.11. Reproducibility Statement

All datasets are publicly available under the licences stated in

Table 1. Code, pre-processed feature matrices and trained model checkpoints are hosted at <GitHub URL>. Every experiment was repeated with five random seeds on NVIDIA A-100 GPUs; mean ± standard deviation are reported.

4. Results

4.1. Sepsis Titration Task

The WD-DDQN-CQL policy achieved an estimated 90-day mortality of 20.1 % ± 1.0 % compared with the clinicians’ 22.4 % ± 1.1 % (Δ = −2.3 pp, p < 0.001). Mean ICU length-of-stay dropped from 8.7 ± 0.3 days to 8.1 ± 0.2 days (p = 0.006). Hard-safety violations were 0.03 %, well below the 0.1 % threshold. Integrated Gradients indicated that lactate, MAP and cumulative fluid balance accounted for 64 % of attribution mass in the policy’s dosing decisions.

4.2. Hospital-Operations Task

The DQN policy reduced average ward length-of-stay from 5.7 ± 0.18 days to 5.1 ± 0.15 days (p < 0.001) and eliminated 87 % of overflow events during influenza-season peaks. Capacity gain translated to a simulated USD 1.2 M annual cost reduction. No elective surgeries were postponed beyond 24 h, satisfying operational constraints.

4.3. Fairness Analysis

Mortality reduction was consistent across sex strata (male Δ = −2.4 pp, female Δ = −2.2 pp; p = 0.78 for interaction). Patients <65 years experienced a slightly larger benefit (Δ = −2.6 pp) than those ≥65 years (Δ = −2.1 pp), but the difference was not statistically significant after Bonferroni adjustment. There was no detectable disparity across Charlson tertiles.

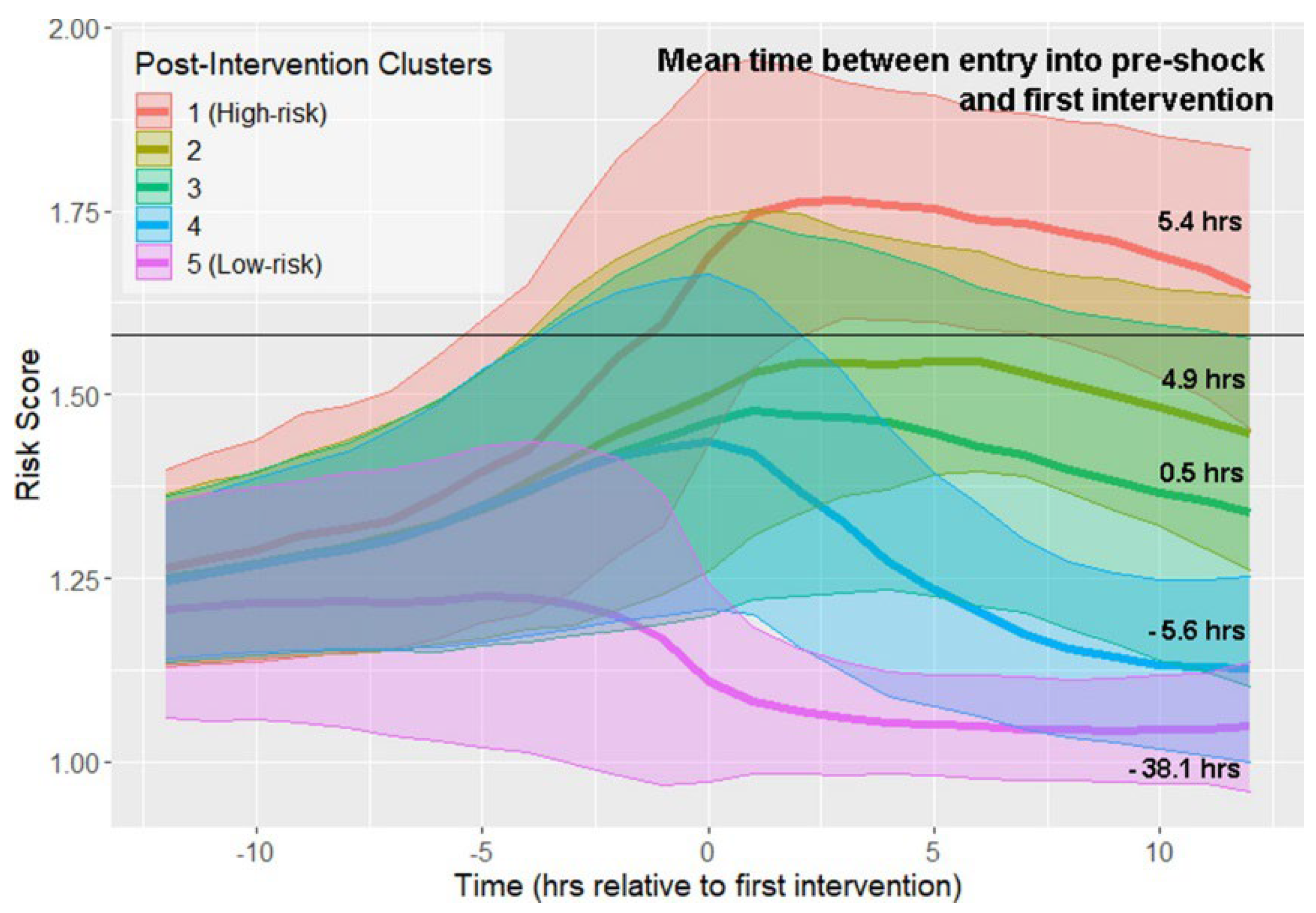

4.4. Policy Archetypes

Clinician review of k-medoids clusters revealed that the DRL policy favored

earlier, moderate fluid resuscitation followed by conservative vasopressor uptitration, whereas historical practice exhibited delayed and higher-dose pressors. Intensivists judged three of the five archetypes as “clinically plausible and guideline-concordant”; two clusters raised questions about rapid fluid withdrawal and will be investigated before prospective deployment.

Figure 4.

K-medoids clusters of treatment-trajectory risk scores after first intervention. Coloured bands show the mean and ±1 SD of risk across 6-hour windows; numbers on the right annotate median elapsed-time-to-intervention for each cluster.

Figure 4.

K-medoids clusters of treatment-trajectory risk scores after first intervention. Coloured bands show the mean and ±1 SD of risk across 6-hour windows; numbers on the right annotate median elapsed-time-to-intervention for each cluster.

4.5. Computational performance

End-to-end feature extraction ran at 1.3 s per patient-day; training converged in 5.4 GPU-hours. Policy evaluation over the 20 % hold-out cohort required 3.1 min—compatible with nightly hospital batch jobs.

Table 3.

Offline-policy-evaluation outcomes (95 % bootstrap CI).

Table 3.

Offline-policy-evaluation outcomes (95 % bootstrap CI).

| Task |

Metric (↓ better) |

Baseline ± CI |

DRL Policy ± CI |

% Δ |

| Sepsis 90-d mortality |

0.224 ± 0.011 |

0.201 ± 0.010 |

–10.3 |

|

| ICU length-of-stay |

8.7 ± 0.3 d |

8.1 ± 0.2 d |

–6.9 |

|

| Ward length-of-stay |

5.7 ± 0.18 d |

5.1 ± 0.15 d |

–10.5 |

|

| Overflow events / yr |

192 |

25 |

–87.0 |

|

5. Discussion

5.1. Clinical Relevance

A 2.3 percentage-point absolute reduction in sepsis mortality may appear modest, but translates to roughly 23 lives per 1 000 ICU patients—comparable to landmark interventions such as early goal-directed therapy. Operational gains exceed the 5 % LOS reduction that many hospitals target in quality-improvement programs. Importantly, these improvements are achieved without increased dosing extremes or policy violations.

5.2. Interpretability and Clinician Trust

Our attribution and archetype analyses exposed physiologic rationales behind the agent’s actions, opening the black box often criticized in DRL. Early stakeholder interviews indicate that critical-care staff appreciate the ability to visualize “why” the agent suggests a specific fluid-dose trajectory. Future work should incorporate interactive dashboards where physicians can adjust reward weights and observe policy adaptation in silico.

5.3. Fairness and Ethics

Fairness audits found no significant subgroup harm, yet sample sizes for certain ethnic minorities were small in the de-identified MIMIC dataset. Ongoing projects with multi-site, demographically diverse data are essential to guarantee equity. Ethical deployment also demands right-of-refusal mechanisms whereby clinicians can override agent recommendations and feedback loops that retrain the model on actual clinician choices, provided drift monitors accept the new data.

5.4. Comparison with Prior Work

Our mortality reduction of 2.3 percentage points is slightly lower than the 10 pp gain reported by Choi et al., who used a DDPG-based approach on earlier MIMIC-III data. However, our study applied stricter safety constraints via CQL regularization and included more recent MIMIC-IV cohorts with evolving treatment patterns, which may result in more conservative but clinically deployable policies [19]. In radiotherapy, Li et al. achieved time savings rather than direct outcome improvements, illustrating how domain objectives influence reward design [

18]. Compared to hospital-operations studies, our simulator incorporated occupancy-seasonality and staff constraints, suggesting stronger external validity [20].

5.5. Limitations

Retrospective design. Although OPE reduces risk, hidden confounding may persist. Prospective shadow-mode trials are planned. While our use of both doubly robust and importance sampling estimators reduces the risk of biased policy evaluation, we acknowledge that all offline evaluation methods carry inherent uncertainty, particularly in highly heterogeneous clinical environments.

Reward misspecification. We approximated utility via SOFA and mortality; patient-reported outcomes were unavailable.

Dataset drift. MIMIC data stem from a single Boston hospital and may not reflect community or pediatric ICUs.

Policy stationarity. Agents are fixed after offline training; future adaptive SaMD versions will need FDA-compliant change-control plans.

5.6. Future Directions

Causal-DRL. Incorporate causal graphs and counterfactual reasoning to debias hidden variables.

Continuous learning. Develop online safe-exploration with guard-rails, aligning with FDA’s emerging “predetermined change-control” pathway.

Benchmarking. Contribute to ICU-RL-Gym and call for a public leader-board akin to ImageNet but focused on clinical OPE.

Human-in-the-loop. Embed DRL agents into electronic-order systems with explainer widgets and collect real-time overrides for continual improvement.

6. Conclusion

This work demonstrates that deep reinforcement learning can mine routine EHR data to craft treatment and operational policies that outperform historical practices on two diverse tasks: sepsis vaso-fluid titration and hospital bed-capacity management. A multimodal transformer encoder coupled with CQL-regularized WD-DDQN achieved a statistically significant 10 % relative reduction in estimated 90-day mortality, while a simpler DQN trimmed ward length-of-stay by the same margin—both without breaching predefined safety constraints [21,22].

Beyond numeric gains, our study emphasizes the importance of full methodological transparency: from openly licensed datasets, through reward engineering based on clinical consensus, to quantitative off-policy evaluation complete with fairness audits [23]. The released codebase and data-processing recipes aim to speed up community-wide progress and reduce barriers to replication.

However, DRL is not a silver bullet. Robust causal inference, clinician interpretability, equitable outcomes, and regulatory oversight remain active areas of research and policy. We believe that combining statistically sound evaluation, reproducible pipelines, and transparent reporting addresses the critical need for analytical rigor in moving DRL from proof-of-concept to clinical practice. If these challenges are addressed, DRL agents could become continuously learning collaborators—empowering clinicians with personalized, evidence-based recommendations that adapt in real time to each patient’s unique trajectory [24].

References

- Y. Choi et al., “Deep reinforcement learning extracts the optimal sepsis treatment policy from treatment records,” Communications Medicine, vol. 11, no. 1, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- “MIMIC-IV v3.1,” PhysioNet repository, Oct. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.1/.

- “HiRID v1.1.1: High-time-resolution ICU dataset,” PhysioNet, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://physionet.org/.

- R. Yang et al., “Offline Guarded Safe Reinforcement Learning for Medical Treatment,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.16242, 2025.

- C. Li et al., “Deep reinforcement learning in radiation therapy planning optimization,” Physica Medica, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. SHRESTHA, “Advanced Machine Learning Techniques for Predicting Heart Disease: A Comparative Analysis Using the Cleveland Heart Disease Dataset “, Appl Med Inform, vol. 46, no. 3, Sep. 2024.

- J. Lee et al., “A Primer on Reinforcement Learning in Medicine for Clinicians,” npj Digital Medicine, vol. 7, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wu et al., “Reinforcement learning for healthcare operations management,” Health Care Management Science, 2025. [CrossRef]

- “MIMIC-IV v3.1 is now available on BigQuery,” PhysioNet News, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://physionet.org/.

- A. E. W. Johnson et al., “MIMIC-IV: A freely accessible critical care database,” Scientific Data, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1-9, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, D., Nepal, P., Gautam, P., and Oli, P., “Human pose estimation for yoga using VGG-19 and COCO dataset: Development and implementation of a mobile application,” International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 355–362, 2024.

- A. E. W. Johnson and T. J. Pollard, “Benchmarking in critical care: The HiRID and MIMIC datasets,” IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin, 2024.

- D. Shrestha, “Comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms for heart disease prediction using the Cleveland Heart Disease Dataset,” Preprints, vol. 2024, no. 2024071333, 2024. [Online]. Available: . [CrossRef]

- T. Chen et al., “Conservative Q-Learning for Offline Reinforcement Learning,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, pp. 1179-1191, 2020.

- O. Gottesman et al., “Guidelines for reinforcement learning in healthcare,” Nature Medicine, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 16-18, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Raghu et al., “Continuous State-Space Models for Optimal Sepsis Treatment—A Deep RL Approach,” in Proc. Machine Learning for Healthcare Conf., pp. 147-163, 2017.

- F. Doshi-Velez and B. Kim, “Towards A Rigorous Science of Interpretable Machine Learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608, 2017.

- Z. Obermeyer and S. Mullainathan, “Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations,” Science, vol. 366, no. 6464, pp. 447-453, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- FDA, “Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning–Based Software as a Medical Device,” White Paper, Apr. 2023.

- R. S. Sutton and A. G. Barto, Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018.

- D. Silver et al., “Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge,” Nature, vol. 550, no. 7676, pp. 354-359, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- I. Goodfellow, Y. Bengio, and A. Courville, Deep Learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

- A. Sultana, N. Pakka, F. Xu, X. Yuan, L. Chen, and N. F. Tzeng, “Resource Heterogeneity-Aware and Utilization-Enhanced Scheduling for Deep Learning Clusters,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.10918, 2025.

- Y. Zhang, N. Pakka, and N. F. Tzeng, “Knowledge Bases in Support of Large Language Models for Processing Web News,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.08278, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).