1. Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a condition characterized by an imbalance in bone remodeling, caused by decreased osteoblast activity and increased osteoclast activity.[

1,

2,

3] As a common chronic health issue among the elderly, OP has become a serious global problem.[

4] Impaired bone remodeling not only underlies the pathology of OP but is also increasingly recognized as a significant public health problem.[

5,

6] Currently, treatments for OP include calcitonins, vitamin K analogs, and so on.[

7] Nonetheless, many agents can negatively impact a patient’s health. For example, vitamin K analogs have been reported to cause side effects such as stomach upset, abdominal pain, skin itching, and edema.[

8] In recent years, there are increasing interest in active compounds sourced from natural products, attributed to their low toxicity and positive safety profiles [

6]; He et al. found that natural Chinese medicines offer therapeutic anabolic and anticatabolic advantages for treating OP.[

9]

The therapeutic potential of flavonoids was being investigated more and more in the promotion of osteogenic differentiation.[

10]

Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal.) Iljinskaja (

C.paliurus), a traditional Chinese and medicinal plant, belongs to the genus

Cyclocarya in the family Juglandaceae and has survived since the glacial century.[

11] It is widely distributed in regions such as Jiangxi, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Anhui, Fujian, Taiwan, typically growing in mountainous areas at altitudes ranging from 420 to 2500 meters.[

12] The leaves of

C.paliurus are known for their therapeutic properties, including heat-clearing, pain-relieving, and treatment of persistent ringworm.[

12,

13] Flavonoids are among the primary active compounds found in these leaves.[

14] These compounds are also abundant in various plant-based foods, such as vegetables and herbs. [

15,

16] Bellavia reported that flavonoids exert protective effects against osteoporosis by influencing the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of cells involved in bone homeostasis.[

1] Despite the broad spectrum of biological activities attributed to flavonoids, such as scavenging free radicals, lowering blood glucose levels, inhibiting liver cancer, and enhancing immune function; however, there is no reference regarding CPF’s effects on MC3T3-E1 cells’ osteogenic proliferation and differentiation. Considering CPF’s pharmacological potential, more study on its osteogenic effects should be done.

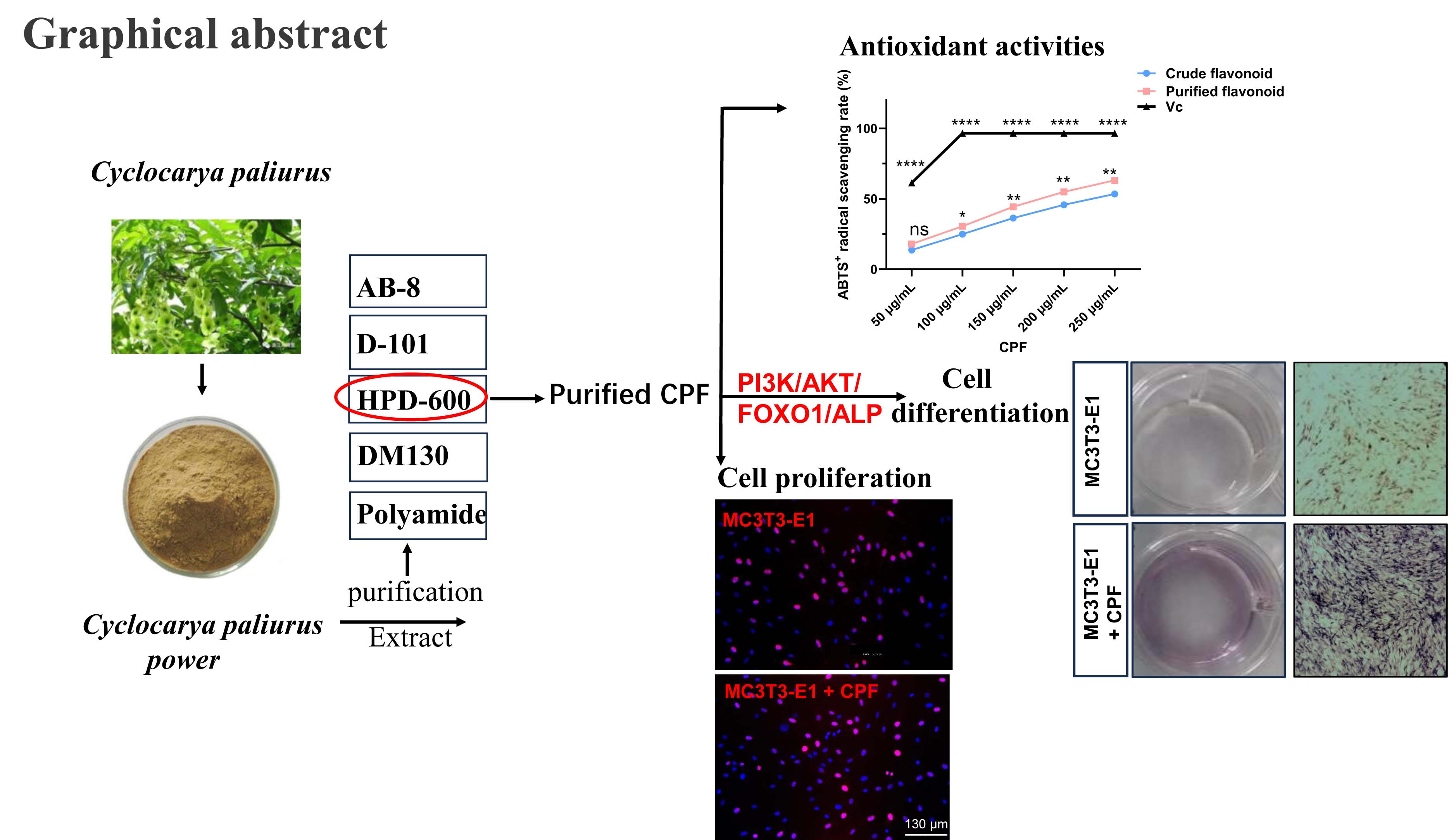

In this study, we compared the efficiency of five different resins (HPD-600, AB-8, D-101, DM130, and Polyamide) for purifying CPF. Resins are widely used in the pharmaceutical industry for the separation, extraction and purification of chemical components from Chinese herbal medicines.[

17] Compared to traditional adsorbents, resins have several advantages, including high selectivity, large adsorption capacity, easy desorption, and strong resistance to contamination.[

18] To optimize the separation and extraction conditions, the resins were selected based on key parameters that influence their performance. The best to purify CPF was determined by using HPD-600 macroporous resin. Additionally, cell proliferation assays, extracellular alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity assays, and osteogenic differentiation assays were conducted to evaluate the effects of CPF on mouse embryo osteoblast precursor (MC3T3-E1) cells. The expression of osteogenic proteins, such as ALP, was assessed to further investigate CPF’s effect on MC3T3-E1 cells. Furthermore, the effects of CPF on PI3K-AKT-FoxO signaling pathway were studied.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Selection of 5 Different Resins for CPF Extraction

The adsorption capacity of different resin types can vary significantly under identical conditions, and it has been reported that resin polarity is closely correlated with adsorption performance.[

19] CPF was purified by testing four different kinds of macroporous resins (HPD-600, AB-8, D-101, and DM130) and a polyamide resin. As shown in

Table 1, the static adsorption-desorption characteristics of resins was used to identify five different resins for the purification of CPF.

As shown in Table1, the results indicated that HPD-600 macroporous resin had the optimal extraction efficiency to purify CPF with an adsorption rate of 77.401 ± 0.50% and a desorption rate of 92.544 ± 0.68%, compared with the resins of AB-8, D-101, DM130 resins and a polyamide resin. Therefore, HPD-600 was selected the optimal resin to purify CPF due to the superior binding and elution properties. The results were the same with the results of Saraswaty et al, who reported that fractionation using HPD-600 resin significantly enhanced the antioxidant activity of

Gnetum gnemon L. seed hard shell extract.[

20] HPD-600 macroporous resin was identified as the optimal to purify CPF in this study, and five chemical compositions of CPF by HPLC might well be isoquercetin, quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside, kaempferol-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside, quercetin and kaempferol with the content of 2.37%, 1.94%, 15.77%, 4.86% and 2.64%, respectively[

21].

2.2. The Ideal Adsorption-Resolution Parameters by Adsorption and Resolution Tests

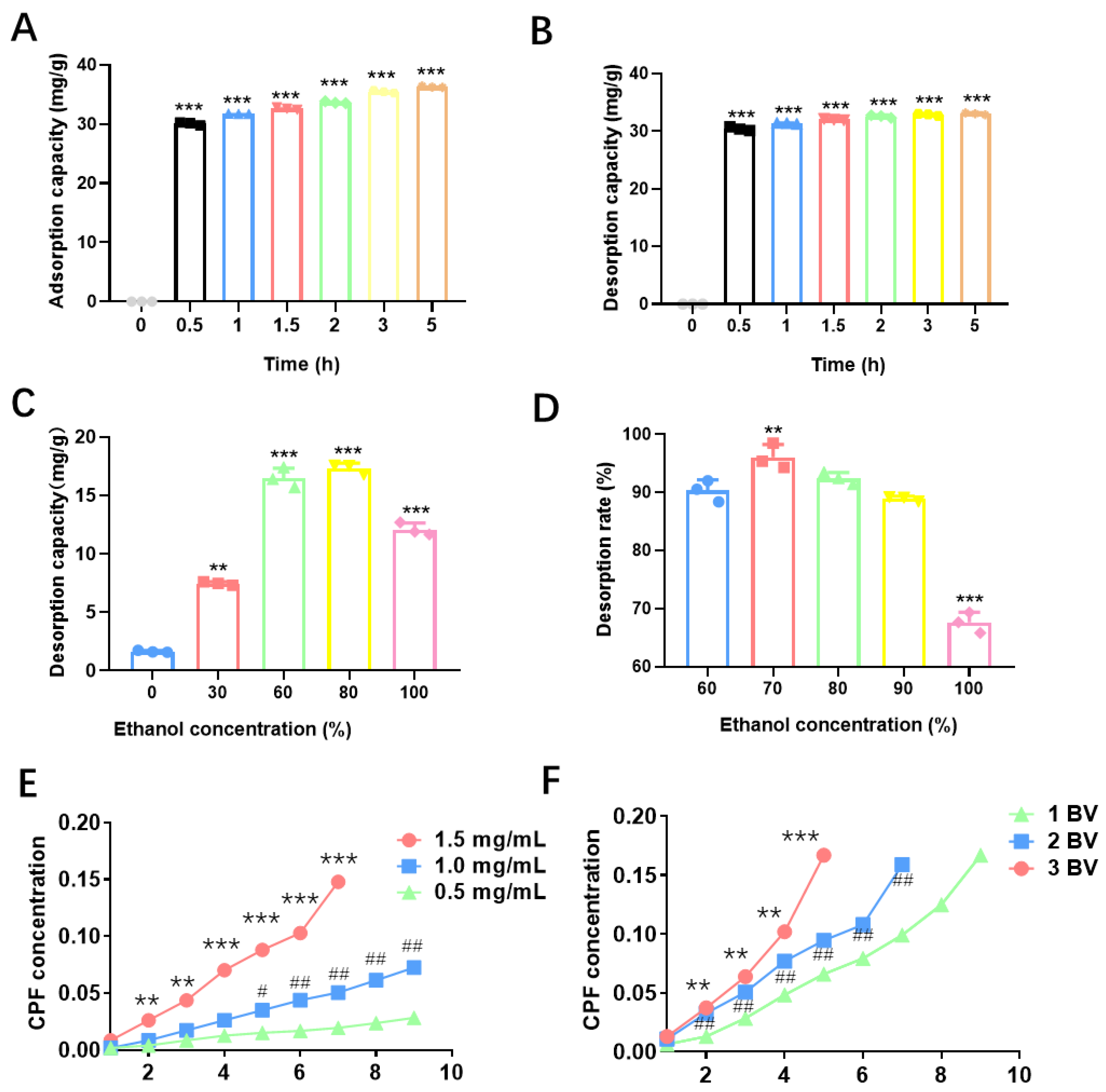

The static adsorption capacity using HPD-600 macroporous resin to purify CPF was shown in

Figure 1A. The adsorption rate of CPF rose rapidly during the first 0.5 h, reaching its maximum capacity, with equilibrium attained after around 5 h.

Figure 1B presents the static desorption capacity using HPD-600 macroporous resin to purify CPF. Desorption occurred rapidly within the first 0.5 h, and as time progressed, the desorption curve gradually plateaued, reflecting a slower change in desorption capacity.

To determine the optimal ethanol concentration for CPF elution, dynamic adsorption experiments were conducted using ethanol concentrations of 30%, 60%, 80%, and 100%. As shown in

Figure 1C, 80% ethanol demonstrated the best elution performance, followed by 60% and 100%. In contrast, distilled water and 30% ethanol exhibited poor elution efficiency. The optimal flow rate was defined as the rate at which CPF leakage appeared latest.

Figure 1F shows the leakage profiles at flow rates of 1 BV/h, 2 BV/h, and 3 BV/h. The leakage points were observed at approximately 9 BV for 1 BV/h, 7 BV for 2 BV/h, and 5 BV for 3 BV/h. Based on these data, the corresponding adsorption capacities were calculated to be 175 mg, 135 mg, and 78 mg, respectively. Although 1 BV/h resulted in the highest adsorption capacity, it was inefficient due to the lengthy processing time. Conversely, 3 BV/h led to early breakthrough and poor adsorption, and a flow rate of 2 BV/h was identified as optimal, balancing adsorption efficiency and operational feasibility.

As shown in

Figure 1E, when the injection of CPF was 0.5, 1.0, and1.5 mg/mL, the corresponding adsorption capacities were 93 mg, 141 mg, and 135 mg, respectively. Although 1.5 mg/mL yielded slightly lower adsorption than 1.0 mg/mL, the shorter breakthrough time made it less favorable. Thus, 1.0 mg/mL was determined to be the optimal injection concentration, providing the highest adsorption with good time efficiency.

The polarity of ethanol strongly influences its elution capacity for flavonoids.[

22]

Figure 1D illustrated that the desorption rate of CPF was evaluated with ethanol concentrations of 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% Using HPD-600 macroporous resin.

Figure 1E further showed the effect of ethanol concentration on dynamic desorption. Among all tested concentrations, 70% ethanol exhibited the best desorption performance, with faster elution and a higher desorption rate. These results showed the optimal purification conditions for CPF were determined as follows: 70% ethanol as the eluent, 2 BV/h as the flow rate, and 1.0 mg/mL as the feed concentration. Under these optimized conditions, CPF purity reached 69.76% after three rounds of purification, and its antioxidant capacity was significantly enhanced CPF purified with HPD-600 macroporous resin thus demonstrated excellent purification efficiency and high commercial value. Wang et al. also reported that the adsorption/desorption features illustrated that HPD-600 was the best choice for purifying ASTFs from EAS among the six tested resins.[

23]

2.3. Antioxidant Activities

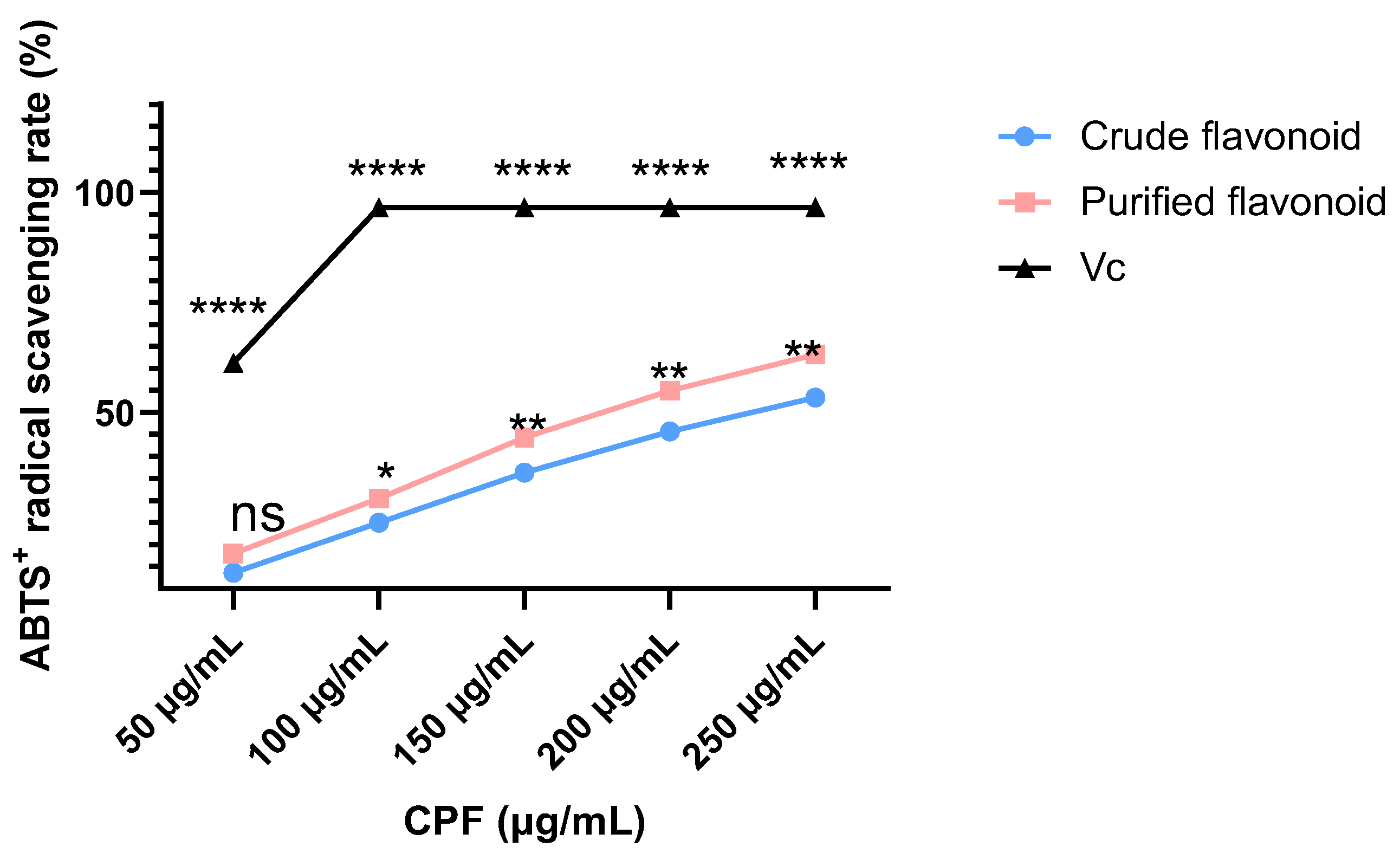

In the reaction system, ABTS⁺ radicals are stably generated through auto-oxidation, producing a characteristic blue-green color. Antioxidants can reduce ABTS⁺ radicals, resulting in a loss of color intensity. When flavonoids or other free radical scavengers are introduced into the system, the solution’s color gradually lightens or even disappears. [

24] The scavenging activity of purified CPF against ABTS⁺ radicals was evaluated based on the degree of color change. As shown in

Figure 2, crude CPF, purified CPF, and ascorbic acid (Vc) all exhibited concentration-dependent ABTS⁺ radical scavenging activity. Purified CPF showed slightly higher scavenging activity than crude CPF, although both were significantly lower than that of Vc. At CPF concentrations of 0.05 to 0.25 mg/mL, CPF displayed scavenging activity ranging from 17.98 ± 0.54% to 63.17 ± 0.85%. The IC₅₀ value of purified CPF for ABTS⁺ radical scavenging was calculated to be 0.185 mg/mL, indicating strong antioxidant capacity at higher concentrations, consistent with previous studies that CPF exhibit excellent ABTS⁺ radical scavenging activity. Given its potent antioxidant properties, CPF holds promise as a natural antioxidant for applications in the food, medical, and cosmetic industries. Given the promising antioxidant performance of CPF, we next investigated its biological effects on MC3T3-E1 cells.

2.4. The Effects of CPF on the Capacity of Cell Viability, Cell Proliferation, and Cell Differentiation in MC3T3-E1 Cells

The osteoblast precursor cell line MC3T3-E1 was produced from mouse calvaria. [

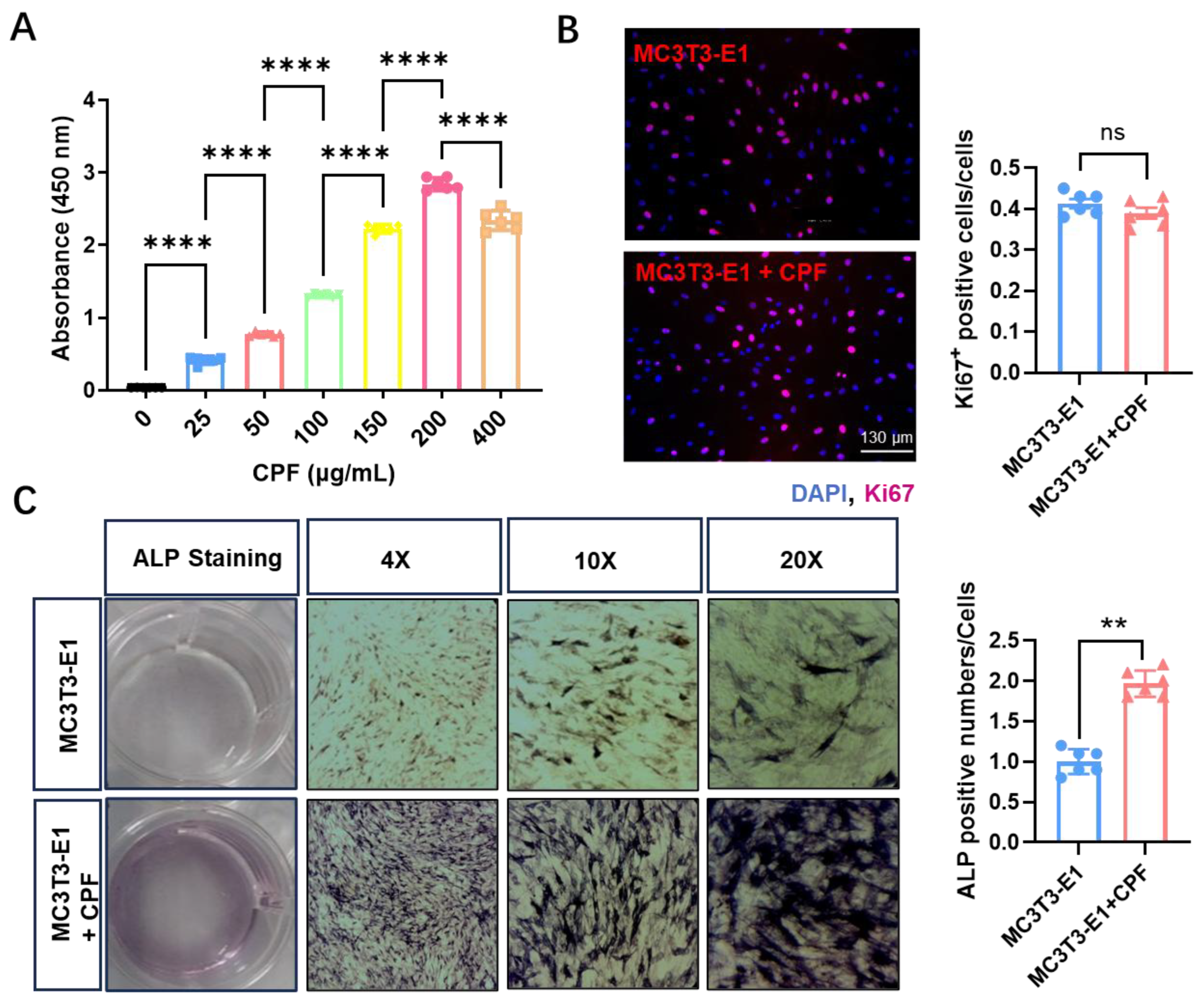

25] MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured with CPF concentrations of 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL. As shown in

Figure 3A, cell viability was improved with increasing CPF concentrations, peaking a maximum at 200 μg/mL. However, when the concentration exceeded this level, a slight decline in viability was observed. The quantity of crystal produced is directly related to the number of viable cells as determined by MTT assays. [

26] These results suggest that CPF, at concentrations up to 200 μg/mL, did not exhibit cytotoxicity and is therefore suitable for use in subsequent cell-based assays. To assess the effect of CPF on cell proliferation, Ki67 immunofluorescence staining was performed.[

27] As shown in

Figure 3B, after 24 h of incubation, the expression of Ki67

+ cells was not affected by CPF treatment. These results indicated that CPF enhanced cell viability at a concentration of 200 μg/mL, not affecting cell proliferation by Ki67 staining, consistent with that most flavonoids do not significantly affect proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells.[

28] This supports the notion that CPF, like many other flavonoids, is non-toxic to osteoblast precursor cells at effective concentrations.[

5]

A natural flavonoid-rich extract, and its role in osteoblast differentiation, renewal, and maintenance is essential for identifying novel therapeutic targets in the treatment of skeletal disorders.[

29] The results revealed that CPF enhanced osteogenic differentiation by ALP staining in

Figure 3C. Specifically, CPF treatment markedly increased the proportion of ALP-positive osteoblasts, indicating its ability to promote osteoblast maturation. This observation aligns with previous studies that 7,8-dihydroxyflavone improved trabecular bone microarchitecture, reduced bone loss, and exerted regulatory effects on bone remodeling.[

30] Similarly, Song et al showed that 3,4’-dihydroxyflavone enhanced osteogenic differentiation of eADSCs through activation of the ERK signaling pathway.[

31]

2.5. The Mechanism How CPF Regulated MC3T3-E1 Cells Differentiations

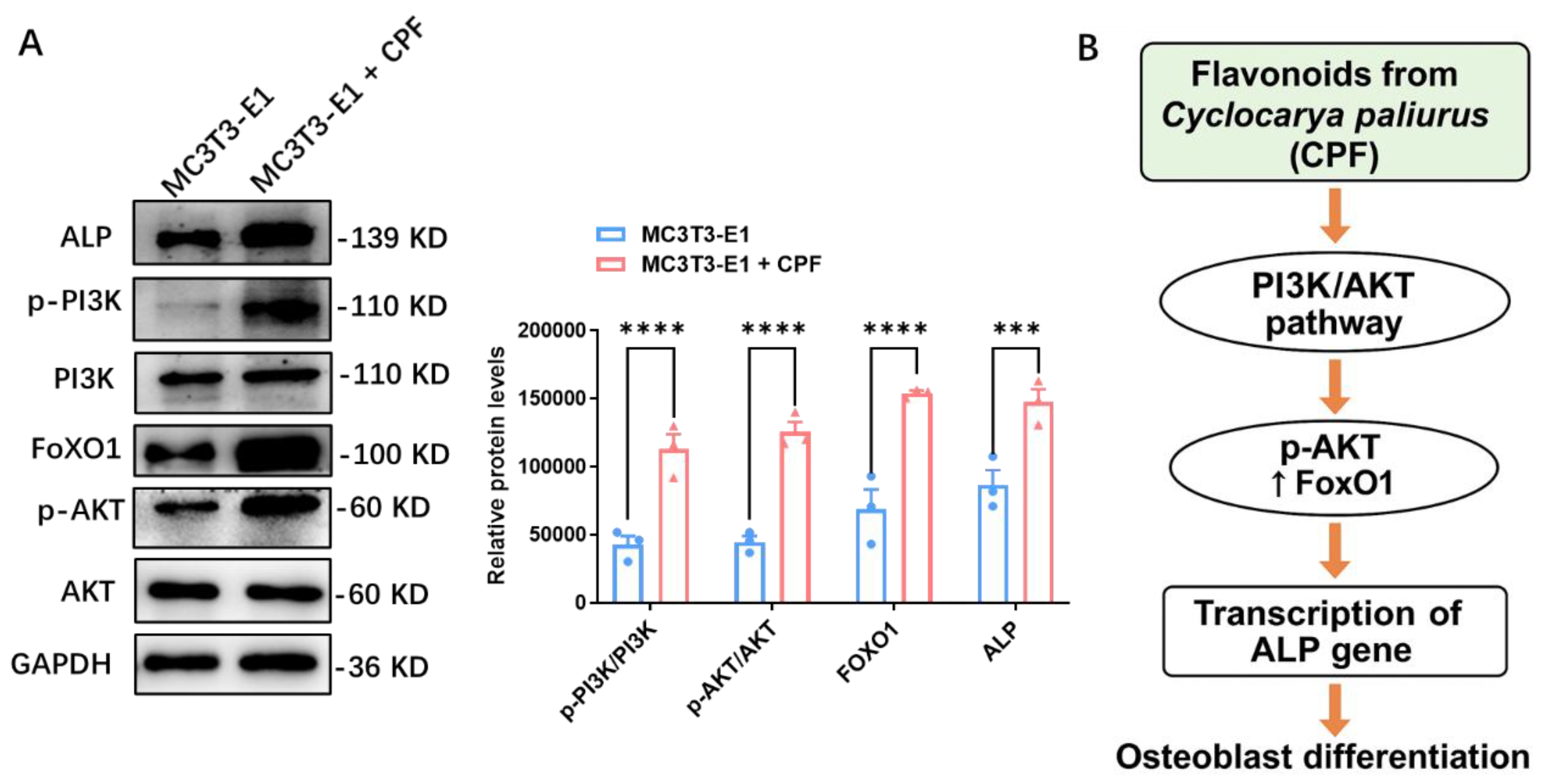

To further elucidate the underlying mechanism, the effect of CPF on the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway was assessed by Western blot analysis on day 7 of osteogenic induction. The expression levels of key osteogenic-related proteins, including ALP, p-PI3K/PI3K, FOXO1, and p-AKT/AKT, were evaluated.

Figure 4A,B illustrated that CPF treatment led to increased protein expression of ALP, p-PI3K/PI3K, FOXO1, and p-AKT/AKT. Importantly, CPF enhanced osteogenic differentiation with no effect on cell proliferation, supporting its role as a differentiation-promoting rather than proliferation-inducing agent. This is consistent with the finding that Calycosin prevented IL-1β-induced damage in articular chondrocytes by regulating the PI3K/AKT/FOXO1 pathway.[

32] Moreover, FoxO1 is the critical target of puerarin in inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption.[

33] While Lai et al reported that 6-OH-flavone enhances osteoblastic differentiation by activating the AKT, ERK1/2, and JNK pathways.[

28] Together, these findings highlight the potential of flavonoids in regulating osteogenesis.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of CPF

C. paliurus leaves were ground, air-dried. To remove interfering components, such as lipophilic substances, petroleum ether was used to extract the dried leaf powder (40 mesh) for 24 h.[

34] Then, using an enzymolysis ultrasonic-assisted extraction procedure, crude CPF was produced; the best result was determined by combining PlackettBurman and BoxBehnken experimental designs.[

21,

26] A rotary evaporator was used to concentrate the extract at 55 C in a vacuum. The purified CPF was finally obtained by centrifugation and filtration of the concentrated sample, followed by vacuum freeze-drying at −40 °C.

3.2. The Static Adsorption-Desorption Characteristics of 5 Different Resins

3.2.1. Measurement of Resins Adsorption Rate

One gram of each of the five different pre-treated resins was added to CPF solution. The mixtures were sealed and placed on a shaking bed at 25 °C and 110 rpm for 24 h to allow adsorption. The adsorption capacity (Q, mg/g) and adsorption rate (E, %) were calculated using the following equations:

where:

C0 is the initial concentration of flavonoids in the extract of total flavonoids of C.paliurus leaves (mg/mL)

C1 is the amount of flavonoids in the extract after adsorption (mg/mL);

V1 is the volume of adsorbent (mL)

W is the mass of resin (g)

3.2.2. Measurement of Resin Resolution Rate

The five different resins were first rinsed with distilled water to remove any residual extract from their surfaces. Next, each resin sample was placed in a 50 mL conical flask, and 10 mL of 60% ethanol was added. The flasks were covered with plastic wrap and placed on a shaker at 25°C and 110 rpm for 24 h to promote desorption. The desorption rate (D, %) was calculated using the following equation:

where:

C2 is the concentration of flavonoids in the resolving solution (mg/mL)

V2 is the amount of the resolving solution (mL)

Q is the adsorption amount of resin (mg/g)

3.3. CPF Purification Using HPD-600 Macroporous Resin

3.3.1. Static Adsorption Capacity Test

In this test, 1 g of HPD-600 resin and 10 mL of CPF solution were added to a 50 mL conical flask. Then, to make adsorption easier, the flask was put on a shaker at 25℃ and a speed of 110 rpm. The quantity of adsorption was calculated at specific time intervals (0,0.5,1,1.5,2,3,and 5 h). The static adsorption curves are shown in

Figure 2A.

3.3.2. Static Desorption Capacity Test

Then, 1 g of the resin was added to a 50 mL conical flask, and 10 mL of 60% ethanol was added. The flask was shaken at 25 °C and 110 rpm to commence desorption. At different times of 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, and 5 h, the concentration of CPF in the ethanol solution was measured, and the desorption capacity (mg/g) was computed as follows

. The results are shown in

Figure 2B.

3.3.3. Effect of Different Ethanol Concentration on the Desorption Capacity and Rate

One gram of HPD-600 resin was weighed, washed with distilled water to remove any residual extract, dried. Subsequently, 10 mL of ethanol at different concentrations (0%, 30%, 60%, 80%, and 100%) was added to a 50 mL conical flask containing the resin. The flask was set on a shaker at 25 °C and 110 rpm to initiate desorption. The desorption capacities and rate at different ethanol concentrations are shown in

Figure 2C,D.

3.3.4. The Dynamic Adsorption Effects on CPF Injection Rate

HPD-600 resin was wet-packed into a column. A CPF solution (1.5 mg/mL) was added to the column at different flow rates of 1 BV/h, 2 BV/h, and 3 BV/h. Effluent was collected for each bed volume (BV) to monitor CPF leakage. The dynamic adsorption is illustrated at varying flow rates in

Figure 2E.

3.3.5. The Dynamic Adsorption Effects on CPF Inlet Mass Concentration

HPD-600 resin was wet-packed into a column. CPF solutions at concentrations of 0.5 mg/mL, 1 mg/mL, and 1.5 mg/mL were loaded at a constant flow rate of 2 BV/h.

Figure 2F illustrates that inlet CPF concentration influences dynamic adsorption.

3.4. Antioxidant Activities

CPF was dissolved in 0.05、0.10、0.15、0.20、and 0.25 mg/mL ethanol at different concentrations. Two milliliters of both crude and purified CPF solutions were transferred into separate test tubes. For each tube, 32 mL of ultrapure water, 2.0 mL of ABTS

+ solution, and 8.0 mL of 1.0 mg/mL potassium persulfate solution were added and then incubated in the dark for 6 min before measuring the absorbance at 734 nm. In the control group, the CPF solution was replaced with 80% ethanol.

where:

A0 is the absorbance of the control.

Ai is the absorbance of sample solution.

3.5. Effect of CPF on MC3T3-E1 Cytotoxicity

MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded at a density of 1×10

5/mL and cultured for 2 h. Following cell attachment, the cells were divided into seven treatment groups, which inculded one blank control group and six CPF treatment groups, each consisting of six replicate wells. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After incubation, 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 4 h, removed the supernatant, then added 150 μL of DMSO. Following a 10-minute shaking period, absorbance was measured at 570 nm.[

35]

3.6. Effect of CPF on Osteogenic Proliferation in MC3T3-E1 Cells by Ki67 Staining

MC3T3-E1 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 20 min, then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min, and subsequently blocked with a blocking solution for 1 h. Then, the cells were treated with rabbit anti-Ki67 antibody (1:500, Invitrogen) and counterstained with DAPI. After staining, an anti-fade mounting medium was applied, and fluorescence images were taken for analysis.

3.7. Effect of CPF on Osteogenic Differentiation in MC3T3-E1 Cells by ALP Staining

MC3T3-E1 cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min and then washed three times with PBS. The BCIP/NBT staining solution was created by combining alkaline phosphatase coloring buffer, BCIP solution (300×), and NBT solution (150×) in the following ratio of 3 mL:10 μL:20 μL, respectively. Both control and CPF-treated (200 μg/mL) MC3T3-E1 cells were incubated with the staining solution for 30 minutes at 37 °C. After removing the solution, cells were washed with PBS, and ALP-stained cells were examined and imaged under a microscope.

3.8. The Mechanism How CPF Regulates Osteogenic Differentiation in MC3T3-E1 Cells

RIPA lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitor was used to extract total protein from both control and CPF-treated (200 µg/mL) MC3T3-E1 cells. Equal amounts of protein were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE gels and subsequently transferred onto PVDF membranes (Life Technologies) at 4 °C using a Bio-Rad transfer system (Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h, incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, and subsequently treated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were taken using an chemiluminescence kit (ECL,Amersham Biosciences).

3.9. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed with 3 to 5 replicates. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 9 (GraphPad Software). For comparisons between two groups, an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used (P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant).

4. Conclusions

In summary, five types of resins (HPD-600, AB-8, D-101, DM130, and Polyamide) were compared for their efficiency in purifying CPF. HPD-600 macroporous resin was identified as the optimal choice. The best purification conditions were established as 70% ethanol elution at a flow rate of 2 BV/h with a CPF concentration of 1.0 mg/mL. Strong ABTS+ radical scavenging activity was shown by purified CPF, which also confirmed that CPF had an antioxidant potential. Moreover, CPF had no significant effect on MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation but significantly enhanced osteogenic differentiation, as evidenced by increased ALP staining and upregulation of ALP expression. CPF enhanced osteogenic differentiation by PI3K-AKT-FOXO1 signaling pathway. CPF may serve as a promising natural supplement for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.

Author Contributions

G.Z., R.X., Z.Y. and L.X. conceived and designed the experiments. G.Z. and R.X. performed data analysis. L.X. drafted the manuscript. Both G.Z. and L.X. contributed to manuscript review and editing, providing critical feedback and expertise.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Young Scholar Project of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (YFYPY202419) for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Bellavia, D. , Dimarco, E., Costa, V., Carina, V., De Luca, A., Raimondi, L., Fini, M., Gentile, C., Caradonna, F., and Giavaresi, G. (2021). Flavonoids in Bone Erosive Diseases: Perspectives in Osteoporosis Treatment. Trends Endocrinol Metab 32, 76-94. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Merchan, E.C. (2021). A Review of Recent Developments in the Molecular Mechanisms of Bone Healing. Int J Mol Sci 22. [CrossRef]

- Du, J. , Wang, Y., Wu, C., Zhang, X., Zhang, X., and Xu, X. (2024). Targeting bone homeostasis regulation: potential of traditional Chinese medicine flavonoids in the treatment of osteoporosis. Front Pharmacol 15, 1361864. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. , Wang, X., Sun, K., Guo, J., Zhao, J., Dong, Y., and Bao, Y. (2024). Onion (Allium cepa L.) Flavonoid Extract Ameliorates Osteoporosis in Rats Facilitating Osteoblast Proliferation and Differentiation in MG-63 Cells and Inhibiting RANKL-Induced Osteoclastogenesis in RAW 264.7 Cells. Int J Mol Sci 25. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.R. , Lee, Y.H., Bat-Ulzii, A., Chatterjee, S., Bhattacharya, M., Chakraborty, C., and Lee, S.S. (2023). Bioactivity, Molecular Mechanism, and Targeted Delivery of Flavonoids for Bone Loss. Nutrients 15. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, L.L. , Guimaraes-Lopes, V.P., Altoe, L.S., Sarandy, M.M., Melo, F., Novaes, R.D., and Goncalves, R.V. (2019). Plant Extracts in the Bone Repair Process: A Systematic Review. Mediators Inflamm 2019, 1296153. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L. (2025). Bone Diseases & Therapy.pdf. Innovations Tissue. Eng Regen Med. 2(1).

- Batteux, B. , Bennis, Y., Bodeau, S., Masmoudi, K., Hurtel-Lemaire, A.S., Kamel, S., Gras-Champel, V., and Liabeuf, S. (2021). Associations between osteoporosis and drug exposure: A post-marketing study of the World Health Organization pharmacovigilance database (VigiBase(R)). Bone 153, 116137. [CrossRef]

- He, J., Li, X., Wang, Z., Bennett, S., Chen, K., Xiao, Z., Zhan, J., Chen, S., Hou, Y., Chen, J., et al. (2019). Therapeutic Anabolic and Anticatabolic Benefits of Natural Chinese Medicines for the Treatment of Osteoporosis. Front Pharmacol 10, 1344. [CrossRef]

- Ming, L.G., Chen, K.M., and Xian, C.J. (2013). Functions and action mechanisms of flavonoids genistein and icariin in regulating bone remodeling. J Cell Physiol 228, 513-521. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Li, Y.-Y., Wu, X., Gao, Z.-Z., Liu, C., Zhu, M., Song, Y., Wang, D.-Y., Liu, J.-G., and Hu, Y.-L. (2014). Chemical constituents from Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal.) Iljinsk. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 57, 216-220. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. , Wang, W., Dong, C., Huang, L., Wang, H., Li, C., Nie, S., and Xie, M. (2018). Protective effect of flavonoids from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves against carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 119, 392-399. [CrossRef]

- Mo, J., Tong, Y., Ma, J., Wang, K., Feng, Y., Wang, L., Jiang, H., Jin, C., and Li, J. (2023). The mechanism of flavonoids from Cyclocarya paliurus on inhibiting liver cancer based on in vitro experiments and network pharmacology. Front Pharmacol 14, 1049953. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. , Jian, Y., Wu, Q., Wu, J., Sheng, W., Jiang, S., Shehla, N., Aman, S., and Wang, W. (2022). Cyclocarya paliurus (Batalin) Iljinskaja: Botany, Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol 285, 114912. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.M., Alekel, D.L., Ward, W.E., and Ronis, M.J. (2012). Flavonoid intake and bone health. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr 31, 239-253. [CrossRef]

- Nash, L.A., Sullivan, P.J., Peters, S.J., and Ward, W.E. (2015). Rooibos flavonoids, orientin and luteolin, stimulate mineralization in human osteoblasts through the Wnt pathway. Mol Nutr Food Res 59, 443-453. [CrossRef]

- Shen, D. , Labreche, F., Wu, C., Fan, G., Li, T., Dou, J., and Zhu, J. (2022). Ultrasound-assisted adsorption/desorption of jujube peel flavonoids using macroporous resins. Food Chem 368, 130800. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. , Dai, X., Zhang, J., Gao, S., and Lu, X. (2024). Guide for application of macroporous adsorption resins in polysaccharides purification. eFood 5. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. , Peng, S., Peng, M., She, Z., Yang, Q., and Huang, T. (2020). Adsorption and desorption characteristics of polyphenols from Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. leaves with macroporous resin and its inhibitory effect on alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase. Ann Transl Med 8, 1004. [CrossRef]

- Saraswaty, V. , Ketut Adnyana, I., Pudjiraharti, S., Mozef, T., Insanu, M., Kurniati, N.F., and Rachmawati, H. (2017). Fractionation using adsorptive macroporous resin HPD-600 enhances antioxidant activity of Gnetum gnemon L. seed hard shell extract. J Food Sci Technol 54, 3349-3357. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L. , Hu, W.-B., Yang, Z.-W., Hui, C., Wang, N., Liu, X., and Wang, W.-J. (2019). Enzymolysis-ultrasonic assisted extraction of flavanoid from Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal) Iljinskaja:HPLC profile, antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. Industrial Crops and Products 130, 615-626. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. , Song, Y., Wang, H., Fu, Y., Zhang, Y., and Pavlovna, K.I. (2022). Optimization of Flavonoid Extraction from Salix babylonica L. Buds, and the Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of the Extract. Molecules 27. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. , Su, J., Chu, X., Zhang, X., Kan, Q., Liu, R., and Fu, X. (2021). Adsorption and Desorption Characteristics of Total Flavonoids from Acanthopanax senticosus on Macroporous Adsorption Resins. Molecules 26. [CrossRef]

- Shang, X. , Tan, J.N., Du, Y., Liu, X., and Zhang, Z. (2018). Environmentally-Friendly Extraction of Flavonoids from Cyclocarya paliurus (Batal.) Iljinskaja Leaves with Deep Eutectic Solvents and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activities. Molecules 23. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Yin, C., Hu, L., Chen, Z., Zhao, F., Li, D., Ma, J., Ma, X., Su, P., Qiu, W., et al. (2018). MACF1 Overexpression by Transfecting the 21 kbp Large Plasmid PEGFP-C1A-ACF7 Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation and Bone Formation. Hum Gene Ther 29, 259-270. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L. , Ouyang, K.-H., Jiang, Y., Yang, Z.-W., Hu, W.-B., Chen, H., Wang, N., Liu, X., and Wang, W.-J. (2018). Chemical composition of Cyclocarya paliurus polysaccharide and inflammatory effects in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophage. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 107, 1898-1907. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L. , Lan, M., Liu, C., Li, L., Yu, Y., Wang, T., Liu, F., Wang, K., Liu, J., and Meng, Q. (2023). Immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat (ISLR) negatively regulates osteogenic differentiation through the BMP-Smad signaling pathway. Genes & Diseases. [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.H. , Wu, Y.W., Yeh, S.D., Lin, Y.H., and Tsai, Y.H. (2014). Effects of 6-Hydroxyflavone on Osteoblast Differentiation in MC3T3-E1 Cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014, 924560. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, P. , Jagadeesan, R., Sekaran, S., Dhanasekaran, A., and Vimalraj, S. (2021). Flavonoids: Classification, Function, and Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Bone Remodelling. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 12, 779638. [CrossRef]

- Xue, F. , Zhao, Z., Gu, Y., Han, J., Ye, K., and Zhang, Y. (2021). 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone modulates bone formation and resorption and ameliorates ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis. Elife 10. [CrossRef]

- Song, K. , Yang, G.M., Han, J., Gil, M., Dayem, A.A., Kim, K., Lim, K.M., Kang, G.H., Kim, S., Jang, S.B., et al. (2022). Modulation of Osteogenic Differentiation of Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells by Co-Treatment with 3, 4’-Dihydroxyflavone, U0126, and N-Acetyl Cysteine. Int J Stem Cells 15, 334-345. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. , Pan, X., Wu, J., Li, Y., and Nie, N. (2022). Calycosin prevents IL-1beta-induced articular chondrocyte damage in osteoarthritis through regulating the PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 pathway. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 58, 491-502. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., and Tang, X. (2024). FoxO1 as the critical target of puerarin to inhibit osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. J Pharm Pharmacol 76, 813-823. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L. , Ouyang, K.-H., Chen, H., Yang, Z.-W., Hu, W.-B., Wang, N., Liu, X., and Wang, W.-J. (2020). Immunomodulatory effect of Cyclocarya paliurus polysaccharide in cyclophosphamide induced immunocompromised mice. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 24. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H., Jiang, N., Xu, W., Zhang, Z., Yang, Y., Zhang, J., and Xu, H. (2022). Effect of flavonoids from Rhizoma Drynariae on osteoporosis rats and osteocytes. Biomed Pharmacother 153, 113379. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).