Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

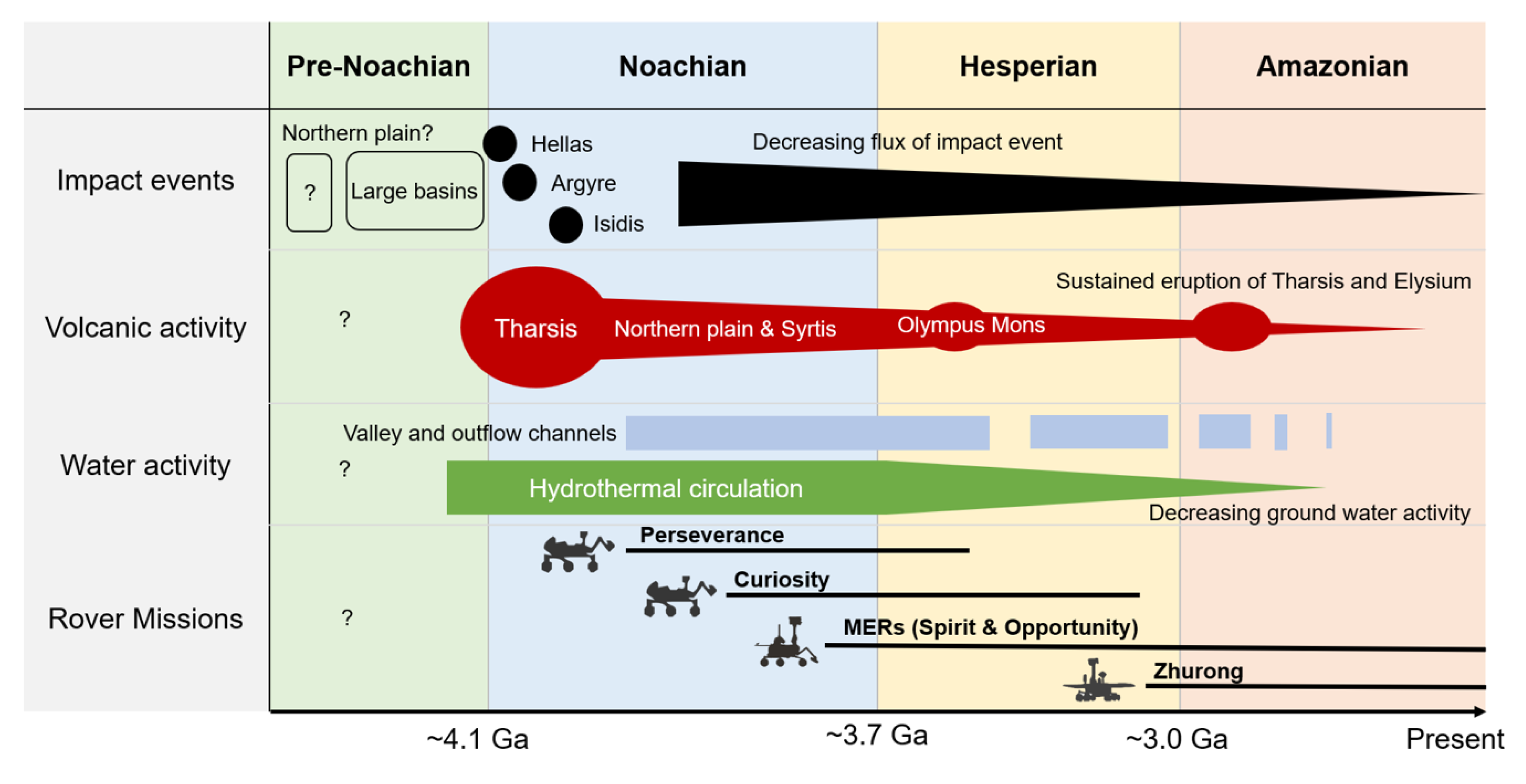

1. Introduction

2. Developing LIBS for Another Planet

2.1. Advantages and Challenges for LIBS on Mars

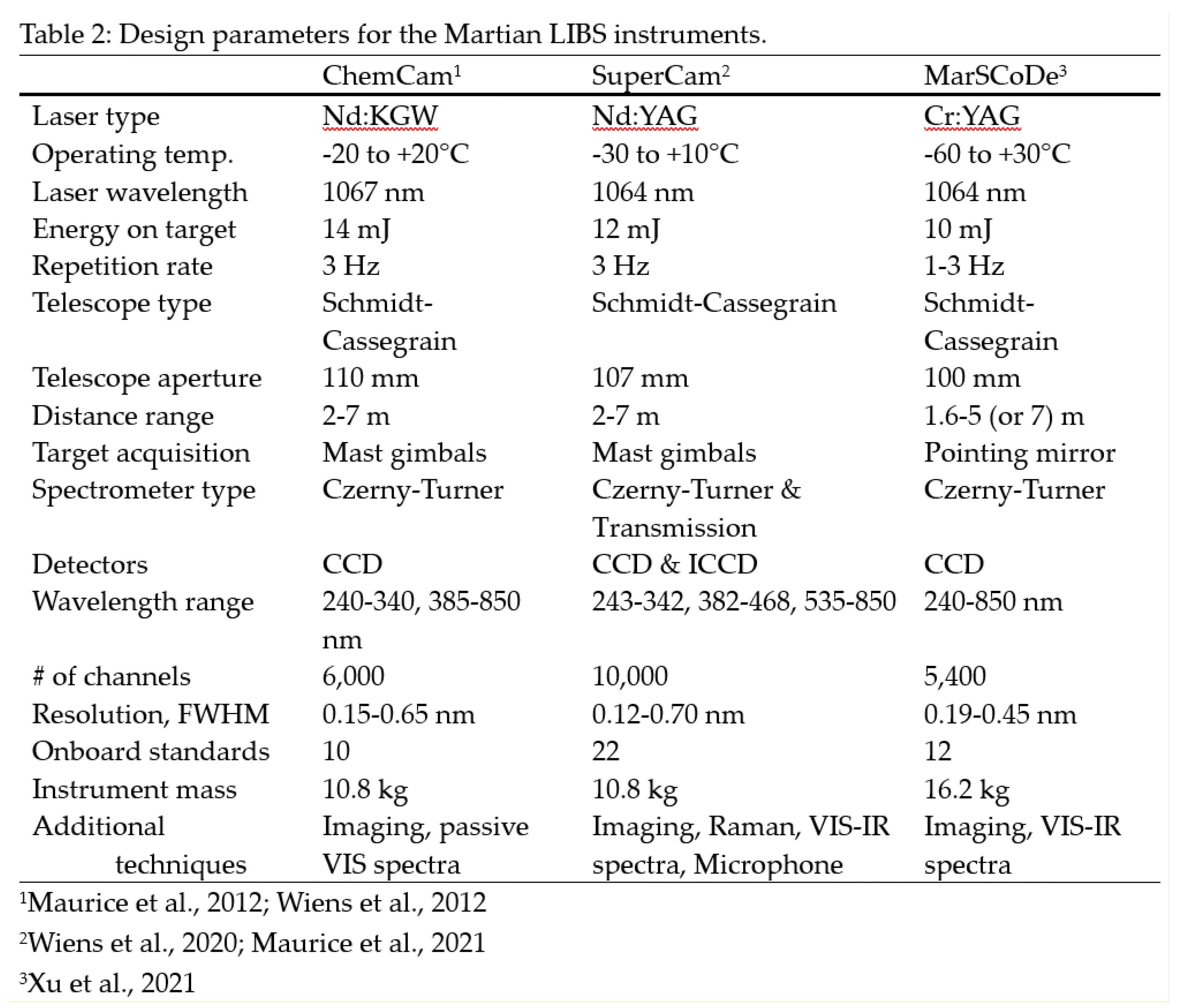

2.2. Instrument Designs

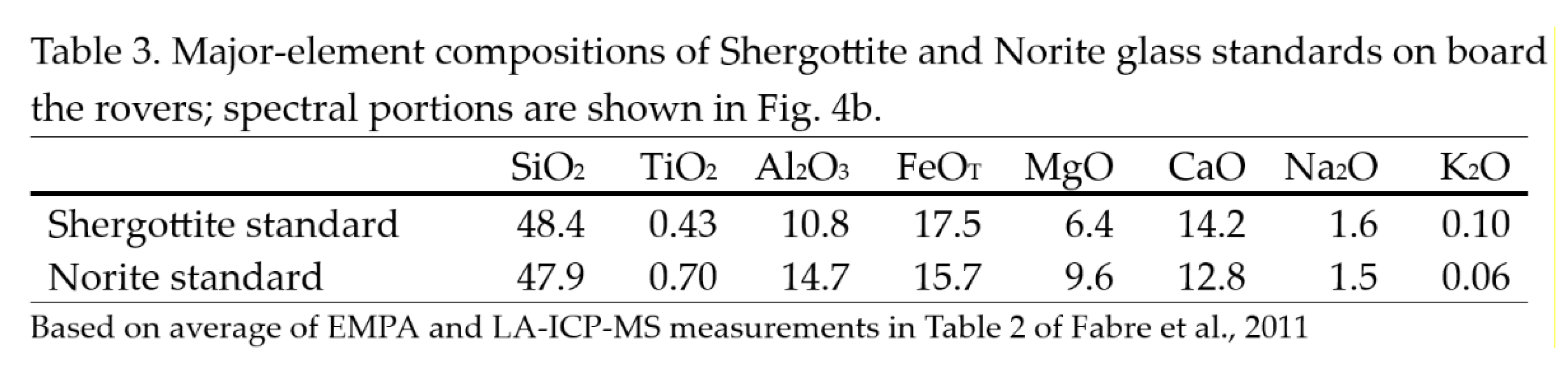

2.3. Data Processing and Calibrations

3. Highlights from Three Mars Missions

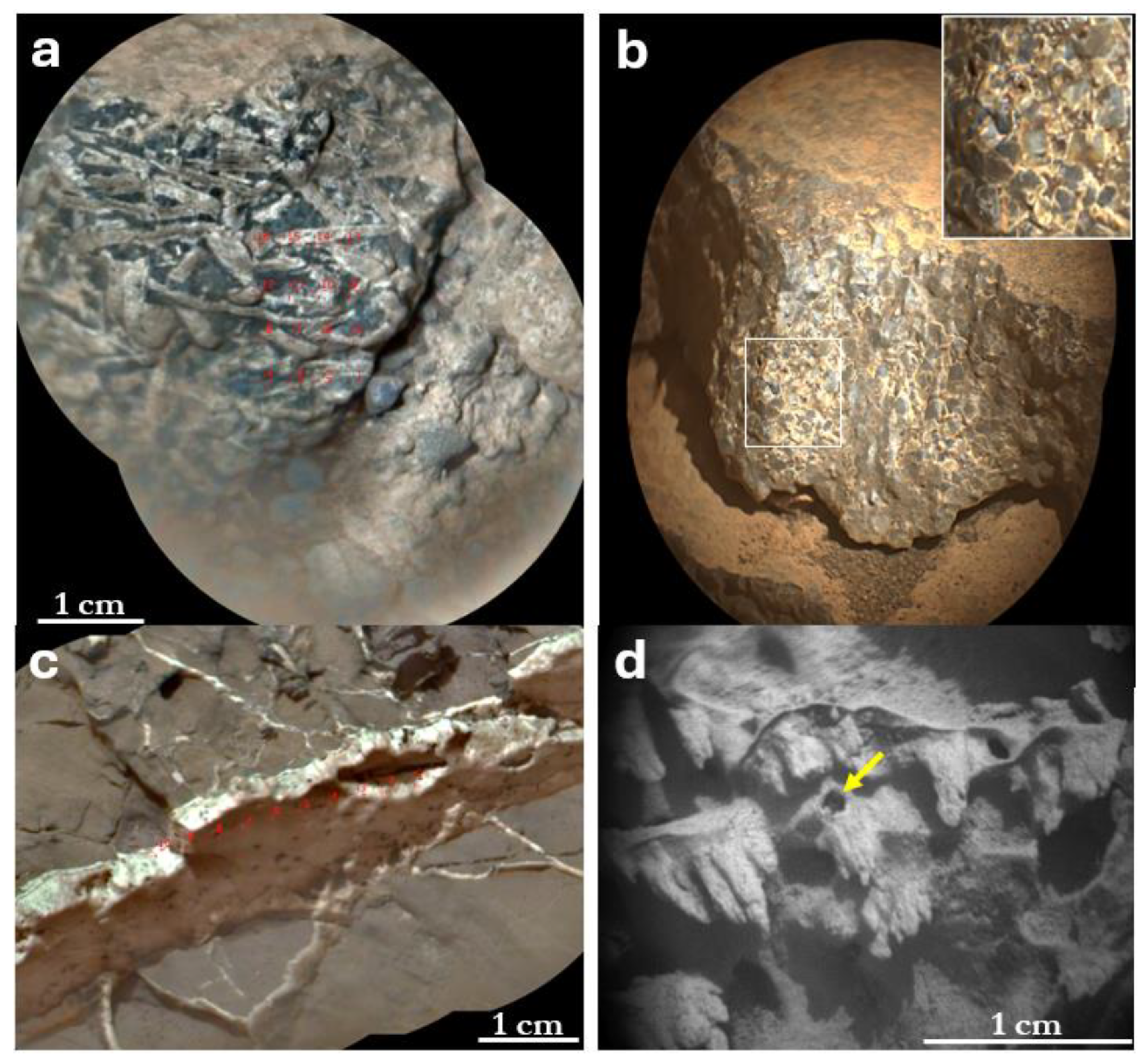

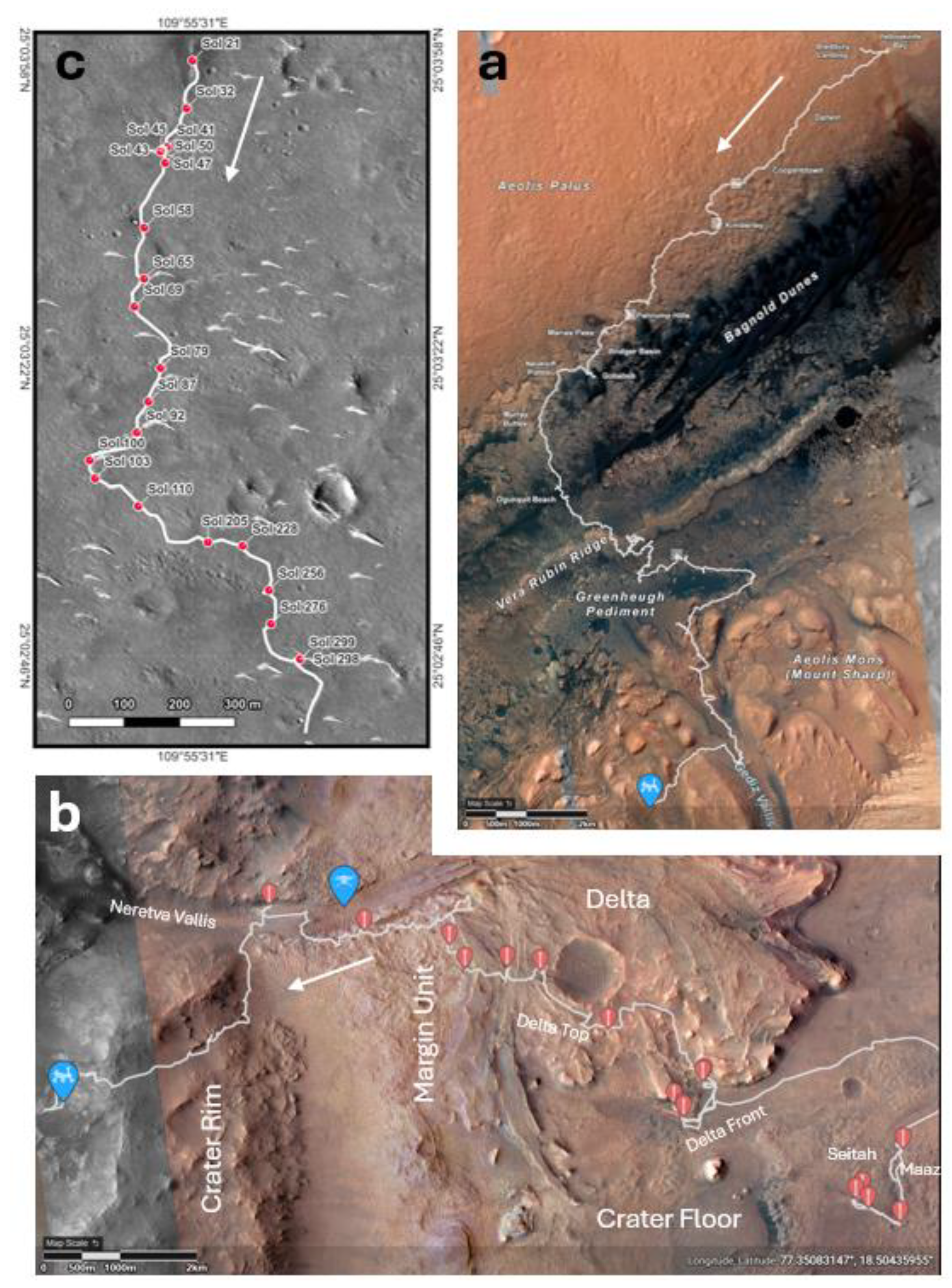

3.1. LIBS Discoveries in an Ancient Lakebed: ChemCam in Gale Crater

3.2. Exploration of Jezero Crater: SuperCam on Perseverance

3.3. Exploration of Utopia Planitia: MarSCoDe on the Zhurong rover

3.4. Synthesis: Comparison of All Mars Compositions

4. Summary and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two dimensional |

| APXS | Alpha particle x-ray spectrometer |

| CCD | Charge coupled device |

| CIA | Chemical index of alteration |

| CNES | Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (France) |

| CNSA | China National Space Administration |

| C-T | Czerny-Turner |

| CWL | Continuous-wave laser |

| EMPA | Electron microprobe analyzer |

| FWHM | Full width at half maximum |

| HCP | High-calcium pyroxene |

| ICCD | Intensified charge coupled device |

| IR | Infrared |

| LA-ICP-MS | Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer |

| LCP | Low-calcium pyroxene |

| LIBS | Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy |

| MVA | Multivariate analysis |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration (USA) |

| PMEC | Probabilistic major-element calibration |

| RMI | Remote Micro-Imager |

| TAR | Transverse aeolian ridge |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VBF | Vastitas Borealis Formation |

| VISIR | Visible and infrared |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

Appendix A

| Figure | Credit |

| 1a | NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS |

| 1b | NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS |

| 1c | CNSA/NAOC/GRAS (Ground Res. & Application System) |

| 2a | LANL; rover mast inset: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS |

| 2b | LANL |

| 2c | SITP/NAOC |

| 3 | NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS; inset: NASA/JPL-Caltech/LANL/CNES/IRAP |

| 6a | NASA/JPL-Caltech/LANL/CNES/IRAP/MSSS/ASU |

| 6b | NASA/JPL-Caltech/LANL/CNES/IRAP |

| 6c | NASA/JPL-Caltech/LANL/CNES/IRAP/MSSS/ASU |

| 6d | CNSA/NAOC/GRAS |

| 8a | NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/ESA |

| 8b | NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/ESA |

| 8c | CNSA/NAOC/GRAS |

References

- Anderson, R.B.; Clegg, S.M.; Frydenvang, J.; Wiens, R.C.; McLennan, S.; Morris, R.V.; Ehlmann, B.; Dyar, M.D. Improved accuracy in quantitative laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy using sub-model partial least squares. Spectrochim. Acta B 2017, 129, 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.B.; Forni, O.; Cousin, A.; Wiens, R.C.; Clegg, S.M.; Frydenvang, J.; Gabriel, T.S.J.; Ollila, A.; Schroeder, S.; Beyssac, O.; Gibbons, E.; Vogt, D.S.; Clavé, E.; Manrique, J.-A.; Legett, C., IV; Pilleri, P.; Newell, R.T.; Sarrao, J.; Maurice, S.; Arana, G.; Benzerara, K.; Bernardi, P.; Bernard, S.; Bousquet, B.; Brown, A.J.; Alverez-Llamas, C.; Chide, B.; Cloutis, E.; Comellas, J.; Connell, S.; Dehouck, E.; Delapp, D.M.; Essunfeld, A.; Fabre, C.; Fouchet, T.; Garcia-Florentino, C.; Garcia-Gomez, L.; Gasda, P.; Gasnault, O.; Hausrath, E.; Lanza, N.L.; Laserna, J.; Lasue, J.; Lopez, G.; Madariaga, J.M.; Mandon, L.; Mangold, N.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Nachon, M.; Nelson, A.E.; Newsom, H.; Reyes-Newell, A.L.; Robinson, S.; Rull, F.; Sharma, S.; Simon, J.I.; Sobron, P.; Torre Fernandez, I.; Udry, A.; Venhaus, D.; McLennan, S.M.; Morris, R.V.; Ehlmann, B. Post-landing major element quantification using SuperCam laser induced breakdown spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta B 2021. [CrossRef]

- Arvidson, R.E. Aqueous history of Mars as inferred from landed mission measurements of rocks, soils, and water ice. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2016, 121, 1602–1626. [CrossRef]

- Beck, P.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Fau, A.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Lasue, J.; Cousin, A.; Schröder, S.; Maurice, S.; Rapin, W.; Wiens, R.C.; Ollila A.M.; Dehouck, E.; Mangold, N.; Garcia, B.; Schwartz, S.; Goetz, W.; Lanza, N. Detectability of carbon with ChemCam LIBS: distinguishing sample from Mars atmospheric carbon, and application to Gale crater. Icarus 2023, 408. [CrossRef]

- Beck, P.; Dehouck, E.; Beyssac, O.; Bernard, S.; Mandon, L.; Royer, C.; Clavé, E.; Forni, O.; Pineau, M.; Francis, R.; Mangold, N.; Bedford, C.; Broz, A.; Cloutis, E.A.; Johnson, J.; Poulet, F.; Fouchet, T.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Pilorget, C.; Schröder, S.; Rapin, W.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Gabriel, T.J.; Arana, G.; Madariaga, J.M.; Wiens, R.C.; Maurice, S.; Clegg, S.; Gasnault, O.; Cousin, A.; the SuperCam team SuperCam detection of hydrated silica in Jezero crater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2025, 656, . [CrossRef]

- Bedford, C.C.; Bridges, J.C.; Schwenzer, S.P.; Wiens, R.C.; Rampe, E.; Frydenvang, J.; Gasda, P.J. Alteration trends and geochemical source region characteristics preserved in the fluviolacustrine sedimentary record of Gale crater, Mars. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2019 246, 234-266. [CrossRef]

- Bedford, C.C.; Ravanis, E.; Clavé, E.; Wiens, R.C.; Forni, O.; Jones, A.; Royer, C.; Garczynski, B.; Beck, P.; Connell, S.; Beyssac, O.; Mandon, L.; Cousin, A.; Horgan , B. Investigating the origin and variable diagenetic overprint of the Margin Unit in Jezero crater, Mars, with SuperCam. J. Geophys, Res. Planets 2025a, in preparation.

- Bedford, C.C.; Wiens, R.C.; Horgan, B.H.N.; Klidaras, A.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Udry, A.; Alwmark, S.; Herd, C.D.K.; Ravanis, E.; Treiman, A.; Johnson, J.; Cousin, A.; Dehouck, E.; Beck, P., Simon, J. Geological diversity in the Jezero crater rim investigated with SuperCam: insights into impact processes on Mars. 56th Lunar Planet. Sci. 2025b, 2495, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2025/pdf/2495.pdf.

- Bosak, T.; Shuster, D.L.; Scheller, E. L.; Siljeström, S.; Zawaski, M. J.; Mandon, L.; Simon, J. I.; Weiss, B. P.; Stack, K. M.; Mansbach, E. N.; Treiman, A. H.; Benison, K. C.; Brown, A. J.; Czaja, A. D.; Farley, K. A.; Hausrath, E. M.; Hickman-Lewis, K.; Herd, C. D.; Johnson, J. R.; Mayhew, L. E.; Minitti. M. E.; Williford, K. H.; Wogsland, B. V.; Zorzano, M.-P.; Allwood, A. C.; Amundsen, H. E. F.; Bell, J. F., III; Benzerara, K.; Bernard, S.; Beyssac, O.; Buckner, D. K.; Cable, M.; Calef, F., III; Caravaca, G.; Catling, D. C.; Clavé, E.; Cloutis, E.; Cohen, B. A.; Cousin, A.; Fáiren, A.; Flannery, D. T.; Fornaro, T.; Forni, O.; Fouchet, T.; Gibbons, E.; Gomez, F.; Gupta, S.; Hand, K. P.; Hurowitz, J. A.; Kalucha, H.; Pedersen, D. A. K.; Lopes Reyes, G.; Maki, J. N.; Maurice, S.; Nuñez, J. I.; Randazzo, N.; Rice, J. W., Jr.; Royer, C.; Sephton, M. A.; Sharma, S.; Steele, A.; Tate, C. D.; Uckert, K.; Udry, A.; Wiens, R. C.; Williams, A.; other members of the Mars 2020 Science Team Astrobiological potential of rocks acquired by the Perseverance rover at a sedimentary fan front in Jezero crater, Mars. AGU Advances 2024, 5, e2024AV001241. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, T.; Dyar, M. D.; Mahadevan, S. Proximal methods for calibration transfer. Chemometrics 2017, 31, . [CrossRef]

- Bowden, D.L.; Bridges, J.C.; Cousin, A.; Rapin, W.; Semprich, J.; Gasnault, O.; Forni, O.; Gasda, P.; Das, D.; Payré, V.; Sautter, V.; Bedford, C.C.; Wiens, R.C.; Pinet, P.; Frydenvang, J. Askival: An altered feldspathic cumulate sample in Gale crater. Met. Planet. Sci. 2022, 101 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.H.; Head, J.W., III Geologic History of Mars, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 294, 3-4, 185-203, . [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ren, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Q; Chen, W. Probabilistic multivariable calibration for major elements analysis of MarSCoDe Martian laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy instrument on Zhurong rover. Spectrochimica Acta B 2022a, 197, . [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, C.; Dong, J.; Rao, W. Rock abundance and erosion rate at the Zhurong landing site in southern Utopia Planitia on Mars. Earth Spa. Sci. 2022b, 9(8), . [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Forni, O.; Cousin, A.; Pilleri, P.; Gasnault, O.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Ren, X; Li, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Shu, R. Quality index for Martian in-situ laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy data. Spectrochim. Acta B 2024a, . [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Caravaca, G.; Loche, M.; Chide, B.; Kurfis-Pal, B.; Zhang, J.; Cousin, A.; Forni, O.; Guo, L.; Lasue, J.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Luo, Y.; Ren, X; Xu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, R.; Kereszturi, A.; Maurice, S.; Li, C. Unexpected Aeolian Buildup Illustrates Low Modern Erosion Along Zhurong Traverse on Mars. 55th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2024b, 1308, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2024/pdf/1308.pdf.

- Clark, B.C.; Baird, A.K.; Rose, H.J., Jr.; Priestley, T., III; Keil, K.; Castro, A.J.; Kelliher, W.C.; Rowe, C.D.; Evans, P.H. Inorganic analyses of Martian surface samples at the Viking landing sites. Science 1976, 194, 1283-1288. [CrossRef]

- Clavé, E.; Gaft, M.; Motto-Ros, V.; Fabre, C.; Forni, O.; Beyssac, O.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Bousquet, B. Extending the potential of Plasma Induced Luminescence spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta B 2021, 177, 106111. [CrossRef]

- Clavé, E.; Benzerara, K.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Forni, O.; Royer, C.; Mandon, L.; Beck, P.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Beyssac, O.; Cousin, A.; Bousquet, B.; Wiens, R. C.; Maurice, S.; Dehouck, E.; Schröder, S.; Gasnault, O.; Mangold, N.; Dromart, G.; Bosak, T.; Bernard, S.; Udry, A.; Anderson, R.B.; Arana, G.; Brown, A.J.; Castro, K.; Clegg, S.M.; Cloutis, E.; Fairén, A.G.; Flannery, D.T.; Gasda, P.J.; Johnson, J.R.; Lasue, J.; Lopez-Reyes, G.; Madariaga, J.M.; Manrique, J.A.; Le Mouélic, S.; Núñez, J.I.; Ollila, A.M.; Pilleri, P.; Pilorget, C.; Pinet, P.; Poulet, F.; Veneranda, M.; Wolf, Z.U.; the SuperCam team Carbonate Detection with SuperCam in Igneous Rocks on the floor of Jezero Crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2023, 128, . [CrossRef]

- Clavé E.; Forni, O.; Royer, C.; Mandon, L.; Dehouck, E.; Mangold, N.; Bedford, C.; Udry, A.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Schroder, S.; Aramendia, J.; Brown, A.; Benison, K.; Bernard, S.; Cardarelli, E.; Coloma, L.; Connell, S.; Johnson, J.; Loche, M.; Lopez-Reyes, G.; Madariaga, J.M.; Manrique, J.A.; Maurice, S.; Meslin, P.-Y.; le Mouelic, S.; Ollila, A.M.; Pilorget, C.; Rammelkamp, K.; Seel, F.; Simon, J.; Wolf, U.; Zastrow, A.; Clegg, S.; Gasnault, O.; Cousin, A.; Wiens, R.C.; the SuperCam Team Diverse aqueous processes recorded in the carbonate-rich rocks in Jezero Crater. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2025, submitted.

- Clegg, S.M.; Wiens, R.C.; Misra, A.K.; Sharma, S.K.; Lambert, J.; Bender, S.; Newell, R.; Nowak-Lovato, K.; Smrekar, S.; Dyar, M.D.; Maurice, S. Planetary geochemical investigations by Raman-LIBS spectroscopy (RLS). Spectrochim. Acta 2014, 68, 925-936. [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S.M.; Wiens, R.C.; Anderson, R.B.; Forni, O.; Frydenvang, J.; Lasue, J.; Pilleri, A.; Payre, V.; Boucher, T.; Dyar, M.D.; McLennan, S.M.; Morris, R.V.; Graff, T.G.; Mertzman, S.A.; Ehlmann, B.L.; Bender, S.C.; Tokar, R.L.; Belgacem, I.; Newsom, H.; McInroy, R.E.; Martinez, R.; Gasda, P.; Gasnault, O.; Maurice, S. Recalibration of the Mars Science Laboratory ChemCam instrument with an expanded geochemical database. Spectrochim. Acta B 2017, 129, 64-85. [CrossRef]

- Comellas, J.M.; Sharma, S.K.; Gasda, P.J.; Cousin, A.; Essunfeld, A.; Mayhew, L.E.; Fryer, P.; Sun, L.; Brown, A.J.; Acosta-Maeda, T.E.; Dehouck, E.; Veneranda, M.; Connell, S.; Cloutis, E.; Ollila, A.; Lanza, N.; Lopez-Reyes, G.; Clavé, E.; Manrique-Martinez, J.A.; Poulet, F.; Johnson, J.; Fouchet, T.; Clegg, S.; Delapp, D.; Sheridan, A.; Maurice, S.; Wiens , R.C. Serpentinization in Jezero Crater: Comparing SuperCam Mars Data to Terrestrial Serpentinites. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2025, in preparation.

- Cousin, A.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Wiens, R.C.; Rapin, W.; Mangold, N.; Fabre, C.; Gasnault, O.; Forni, O.; Tokar, R.; Lasue, J.; Vaniman, D; Ollila, A.; Schroeder, S.; Sautter, V.; Blaney, D.; Le Mouelic, S.; Nachon, M.; Dromart, G.; Newsom, H.; Maurice, S.; Dyar, M.D.; Lanza, N.; Clark, B.; Clegg, S.; Goetz, W.; the MSL Science Team Compositions of coarse and fine particles in martian soils at Gale: A window into the production of soils. Icarus 2015, 249, 22-42. [CrossRef]

- Cousin, A.; Dehouck, E.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Bridges, N.; Ehlmann, B.; Williams, A.; Stein, N.; Schroeder, S.; Rapin, W.; Sautter, V.; Payré, V.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Pinet, P. Geochemistry of the Bagnold Dune Field as observed by ChemCam, and comparison with other Aeolian deposits at Gale crater. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 122 2017a. [CrossRef]

- Cousin, A.; Sautter, V.; Payré, V.; Forni, O.; Mangold, N.; Gasnault, O.; Le Deit, L.; Johnson, J.; Maurice, S.; Salvatore, M.; Wiens, R.C.; Gasda, P.; Rapin, W. Classification of igneous rocks analyzed by ChemCam at Gale crater, Mars. Icarus 2017b, 288, 265-283. [CrossRef]

- Cousin, A.; Sautter, V.; Fabre, C.; Dromart, G.; Montagnac, G.; Drouet, C.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Gasnault, O.; Beyssac, O.; Bernard, S.; Coutis, E.; Forni, O.; Beck, P.; Fouchet, T.; Johnson, J.R.; Lasue, J.; Ollila, A.M.; De Parseval, P.; Gouy, S.; Caron, B.; Madariaga, J.M.; Arana, G.; Madsen, M.B.; Laserna, J.; Moros, J.; Manrique, J.A.; Lopez-Reyes, G.; Rull, F.; Maurice, S.; Wiens R.C. SuperCam calibration targets on board the Perseverance rover: Fabrication and quantitative characterization. Spectrochimica Acta B 2022, . [CrossRef]

- Cousin, A.; Meslin, P-Y.; Forni, O.; Beyssac, O.; Clavé, E.; Hausrath, E.; Beck, P.; Bedford, C.; Sullivan, R.; Schröder, S.; Dehouck, E.; Johnson, J.; Vaughan, A.; Martin, N.; Chide, B.; Lasue, J.; Gasnault, O.; Fouchet, T.; Pilleri, P.; Udry, A.; Poblacion, I.; Arana, G.; Madariaga, J.; Clegg, S.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C. Soil diversity at Jezero crater and Comparison to Gale crater, Mars. Icarus 2025, 425. [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, S.; Hardgrove, C.; Gasda, P.; Calef, F.; Gengl, H.; Rapin, W.; Frydenvang, J.; Nowicki, S.; Thompson, L.; Wiens, R.C.; Newsom, H.; Gabriel, T. Constraints on the hydration and distribution of high-silica layers in Gale crater using LIBS geochemistry and active neutron measurements. JGR Planets 2020. [CrossRef]

- David, G.; Dehouck, E.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Rapin, W.; Cousin, A.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Lasue, J.; Mangold, N.; Beck, P.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Berger, G.; Fabre, C.; Pinet, P.; Clark, B.C.; Lanza, N.L. Evidence for amorphous sulfates as the main carrier of soil hydration in Gale crater, Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL098755. [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, E.; Cousin, A.; Mangold, N.; Frydenvang, J.; Gasnault, O.; Forni, O.; Rapin, W.; Gasda, P.J.; Bedford, C.; Caravaca, G.; David, G.; Lasue, J.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Rammelkamp, K.; Fox, V.K.; Bennett, K.A.; Bryk, A.; Lanza, N.L.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C. In situ geochemical characterization of the clay-bearing Glen Torridon region of Gale crater, Mars, using the ChemCam instrument. J. Geophysical Research, Planets 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, E.; Forni, O.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Beck, P.; Mangold, N.; Royer, C.; Clavé, E.; Beyssac, O.; Johnson, J. R.; Mandon, L.; Poulet, F.; Le Mouélic, S.; Caravaca, G.; Kalucha, H.; Gibbons, E.; Dromart, G.; Gasda, P.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Schroeder, S.; Udry, A.; Anderson, R. B.; Clegg, S.; Cousin, A.; Gabriel, T. S.; Lasue, J.; Fouchet, T.; Pilleri, P.; Pilorget, C.; Hurowitz, J.; Núñez, J.; Williams, A.; Russell, P.; Simon, J. I.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R. C.; the SuperCam Team Overview of the bedrock geochemistry and mineralogy observed by SuperCam during Perseverance’s delta front campaign. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2023, 2862, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2023/pdf/2862.pdf.

- Dehouck, E.; Forni, O.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Beck, P.; Mangold, N.; Beyssac, O.; Royer, C.; Clavé, E.; Johnson, J. R.; Mandon, L.; Poulet, F.; Udry, A.; Lopez-Reyes, G.; Caravaca, G.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R. C.; Stack, K. M.; Anderson, R. B.; Bernard, S.; Bosak, T.; Broz, A. P.; Castro, K.; Clegg, S. M.; Cousin, A.; Dromart, G.; Farley, K. A.; Fouchet, T.; Frydenvang, J.; Gabriel, T.S.J.; Gasda, P.; Gibbons, E.; Horgan, B. H. N.; Hurowitz, J. A.; Kalucha, H.; Lasue, J.; Le Mouélic, S.; Madariaga, J. M.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Nachon, M.; Nuñez, J. I.; Pilleri, P.; Pilorget, C.; Rice, J. W., Jr; Russell, P. S.; Schröder, S.; Shuster, D. L.; Siebach, K. L.; Simon, J. I.; Weiss, B. P.; Williams, A. J.; the SuperCam Team Chemostratigraphy And Mineralogy Of The Jezero Western Fan As Seen By The SuperCam Instrument: Evidence For A Complex Aqueous History And Variable Alteration Conditions. Tenth Int’l. Conf. on Mars, Pasadena, 2024, 3364, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/tenthmars2024/pdf/3364.pdf.

- Ding, L.; Zhou, R.; Yu, T.; Gao, H.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.-Y.S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Bao, G.; Deng.; Z, Huang, L.; Li, N.; Cui, X.; He, X.; Jia, Y.; Yuan, B.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Wu, F.; Xu, Q.; Lu, H.; Richter, L.; Liu, Z.; Niu, F.; Qi, H.; Li, S.; Feng, W.; Yang, C.; Chen, B.; Dang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xing, H.; Wang, G.; Niu, L.; Xu, P.; Wan, W.; Di, K. Surface characteristics of the Zhurong Mars rover traverse at Utopia Planitia. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15(3), 171-176, . [CrossRef]

- Dromart, G.; Le Deit, L.; Rapin, W.; Gasnault, O.; Le Mouelic, S.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Mangold, N.; Rubin, D.; Lasue, J.; Maurice, S.; Pinet, P.; Wiens, R.C. Deposition and erosion of the light-toned yardang unit of Mt. Sharp, Gale crater, Mars Science Laboratory Mission. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2020, 554. [CrossRef]

- Duan, T.; Anand, A.; Ding, D. Y.; Thai, K. K.; Basu, S.; Ng, A.; Schuler, A. NGBoost: Natural gradient boosting for probabilistic prediction. In International conference on machine learning 2020 (November, pp. 2690-2700). PMLR.

- Dyar, M.D.; Tucker, J.M.; Humphries, S.; Clegg, S.M.; Wiens, R.C.; Lane, M.D. Strategies for Mars remote laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy analysis of sulfur in geological samples. Spectrochim. Acta B 2010 66, 39-56. [CrossRef]

- Dyar, M.D.; Ytsma, C.R.; Lepore, K. Geochemistry by Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy on the Moon: Accuracy, Detection Limits, and Realistic Constraints on Interpretations. Earth Spa. Sci. 2024 11, . [CrossRef]

- Ece, O.I.; Ercan, H.U. Global occurrence, geology and characteristics of hydrothermal-origin kaolin deposits. Minerals 2024, 14, 353. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.H.; Bridges, J.C.; Wiens, R.C.; Anderson, R.; Dyar, M.D.; Fisk, M.; Thompson, L.; Gasda, P.; Filiberto, J.; Schwenzer, S.P.; Blaney, D.; Hutchinson, I. Basalt-trachybasalt samples from Gale crater, Mars. Met. Planet. Sci. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ehlmann, B.; Mustard, J.; Murchie, S.; Bibring J.-P.; Meunier A.; Fraeman A.A.; Langevin Y. Subsurface water and clay mineral formation during the early history of Mars. Nature 2011, 479, 53–60, . [CrossRef]

- Ehlmann, B.; Edwards, C.S. Mineralogy of the Martian surface. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2014 42, . [CrossRef]

- Fabre, C.; Maurice, S.; Cousin, A.; Wiens, R.C.; Forni, O.; Sautter, V.; Guillaume, D. Onboard calibration igneous targets for the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover and the Chemistry Camera Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy instrument. Spectrochim. Acta B 2011, 66, 280-289. [CrossRef]

- Farley, K.A.; Williford, K.H.; Stack, K.M.; Bhartia, R.; Chen, A.; de la Torre, M.; Hand, K.; Goreva, Y.; Herd, C.D.K.; Hueso, R.; Liu, Y.; Maki, J.N.; Martinez, G.; Moeller, R.C.; Nelessen, A.; Newman, C.E.; Nunes, D.; Ponce, A.; Spanovich, N.; Willis, P.A.; Beegle, L.W.; Bell, J.F., III; Brown ,A.J.; Hamran, S.-E.; Hurowitz, J.A.; Maurice, S.; Paige, D.A.; Rodriguez-Manfredi, J.A.; Schulte, M.; Wiens, R.C. Mars 2020 mission overview. Spa. Sci. Rev. 2021, 216, 142. [CrossRef]

- Farley, K.A.; Stack Morgan, K.M.; Shuster, D.L.; Horgan, B.H.N.; Tarnas, J.D.; Simon, J.I. Sun, V.Z.; Scheller, E.L.; Moore, K.R.; McLennan, S.M.; Vasconcelos, P.M.; Wiens, R.C.; Treiman, A.H.; Mayhew, L.E.; Beyssac, O.; Kizovski, T.V.; Tosca, N.J.; Hurowitz, J.A.; Allwood, A.C.; Williford, K.H.; Crumpler, L.S.; Beegle, L.W.; Bell, J.F., III; Ehlmann, B.L.; Liu, Y.; Maki, J.N.; Schmidt, M.E.; Amundsen, H.E.F.; Bhartia, R.; Bosak, T.; Brown, A.J.; Clark, B.C.; Cousin, A.; Forni, O.; Gabriel, T.S.J.; Goreva, Y.; Gupta, S.; Hamran, S.-E.; Herd, C.D.K.; Hickman-Lewis, K.; Johnson, J.R.; Kah, L.C.; Kelemen, P.B.; Kinch, K.B.; Mandon, L.; Mangold, N.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Rice, M.S.; Russell, P.S.; Sharma, S.; Siljestrom, S.; Steele, A.; Wadhwa, M.; Weiss, B.P.; Williams, A.J.; Wogsland, B.V.; Willis, P.A.; Acosta-Maeda, T.A.; Beck, P.; Benzerara, K.; Bernard, S.; Burton, A.S.; Cardarelli, E.L.; Chide, B.; Clavé, E.; Cloutis, E.A.; Cohen, B.A.; Czaja, A.D.; Debaille, V.; Dehouck, E.; Fairen, A.G.; Flannery, D.T.; Fleron, S.Z.; Fouchet, T.; Frydenvang, J.; Garczynski, B.J.; Gibbons, E.F.; Hausrath, E.M.; Hayes, A.G.; Henneke, J.; Jorgensen, J.L.; Kelly, E.M.; Lasue, J.; Le Mouelic, S.; Madariaga, J.M.; Maurice, S.; Merusi, M.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Milkovich, S.M.; Million, C.C.; Moeller, R.C.; Nunez, J.I.; Ollila, A.M.; Paar, G.; Paige, D.A.; Pedersen, D.A.K.; Pilleri, P.; Pilorget, C.; Pinet, P.C.; Royer, C.; Sautter, V.; Schulte, M.; Sephton, M.A.; Sharma, S.K.; Sholes, S.F.; Spanovich, N.; St. Clair, M.; Tate, C.D.; Uckert, K.; VanBommel, S.J.; Zorzano, M.-P.; Yanchilina, A.G.; Rice, J.W., Jr. Aqueously altered igneous rocks on the floor of Jezero crater, Mars. Science 2022, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abo2196. [CrossRef]

- Forni, O.; Gaft, M.; Toplis, M.; Clegg, S.M.; Sautter, V.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Mangold, N.; Gasnault, O.; Sautter, V.; Le Mouelic, S.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Nachon, M.; McInroy, R.E.; Ollila, A.M.; Cousin, A.; Bridges, J.C.; Lanza, N.L.; Dyar, M.D. First detection of fluorine on Mars: Implications on Gale crater’s geochemistry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42. [CrossRef]

- Forni, O.; Bedford, C.C.; Royer, C.; Liu, Y.; Wiens, R.C.; Udry, A.; Dehouck, E.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Beyssac, O.; Beck, P.; Gabriel, T.S.; Gasnault, O.; Manelski, H.T.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Johnson, J.R.; Schröder, S.; Pilleri, P.; Nachon, M.; Debaille, V.; Ollila, A.M.; Cousin, A.; Maurice, S.; Clegg, S.M. Nickel-Copper Deposits On Mars: Origin And Formation. Tenth Int’l. Conf. on Mars 2024, Pasadena, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/tenthmars2024/pdf/3131.pdf.

- Forni, O.; Rapin, W.; Sklute, E.C.; Gasda, P.; Loche, M.; Hughes, E.B.; Schröder, S.; Rammelkamp, K.; Gasnault, O.; Lanza, N.L. Elemental sulphur deposit and its related enrichments as viewed by ChemCam. 56th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2025 1476, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2025/pdf/1476.pdf.

- Fouchet, T.; Reess, J.-M.; Montmessin, F.; Hassen-Khodja, R.; Nguyen-Tuong, N.; Humeau, O.; Jacquinod, S.; Lapauw, L.; Parisot, J.; Bonafous, M.; Bernardi, P.; Chapron, F.; Jeanneau, A.; Collin, C.; Zeganadin, D.; Nibert, P.; Abbaki, S.; Montaron, C.; Blanchard, C.; Arslanyan, V.; Achelhi, O.; Colon, C.; Royer, C.; Hamm, V.; Beuzit, M.; Poulet, F.; Pilorget, C.; Mandon, L.; Forni, O.; Cousin, A.; Gasnault, O.; Pilleri, P.; Dubois, B.; Quantin, C.; Beck, P.; Beyssac, O.; Le Mouelic, S.; Johnson, J.R.; McConnochie, T.H.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C. The SuperCam Infrared Spectrometer for the Perseverance rover of the Mars 2020 mission. Icarus 2022, 373, 114773. [CrossRef]

- Frydenvang, J.; Gasda, P.J.; Hurowitz, J.A.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Wiens, R.C.; Newsom, H.E.; Bridges, J.; Maurice, S.; Fisk, M.; Elhmann, B.; Watkins, J.; Stein, N.; Clegg, S.M.; Lanza, N.; Mangold, N.; Cousin, A.; Anderson, R.B.; Payré, V.; Rapin, W.; Vaniman, D.; Morris, R.V.; Blake, D.; Gupta, S.; Sautter, V.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Bedford, C.; Edwards, P.; Rice, M.; Kinch, K.M.; Milliken, R.; Gellert, R.; Thompson, L.; Clark, C.B.; Edgett, K.S.; Sumner, D.; Fraeman, A.; Madsen, M.B.; Mitrofanov, I.; Jun, I.; Calef, F.; Vasavada, A.R. Diagenetic silica enrichment and late-stage groundwater activity in Gale crater, Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Frydenvang, J.; Mangold, N.; Wiens, R.C.; Fraeman, A.A.; Edgar, L.A.; Fedo, C.; L’Haridon, J.; Bedford, C.; Gupta, S.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Bridges, J.; Clark, B.C.; Rampe, E.B.; Maurice, S.; Gasnault, O.; Forni, O.; Gasda, P.J.; Lanza, N.L.; Ollila, A.M.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Payré, V.; Calef, F.; Salvatore, M.; House, C. The chemostratigraphy of Murray formation bedrock and role of diagenesis at Vera Rubin Ridge in Gale crater, Mars, as observed by the ChemCam instrument. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2020, 125, e2019JE006320. [CrossRef]

- Frydenvang, J.; Nikolajsen, K.W.; Dehouck, E.; Gasda, P.J.; Clegg, S.M.; Bryk, A.B.; Edgar, L.A.; Rapin, W.; Forni, O.; Cloutis, E.; Fraeman, A.A.; Vasavada, A.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Gasnault, O.; Lanza, N.L. Geochemical variations observed by the ChemCam instrument as the Curiosity rover transitioned from clay-mineral to sulfate-mineral rich regions on Aeolis Mons in Gale crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2025, in preparation.

- Gabriel, T.S.J.; Forni, O.; Anderson, R.B.; Manrique, J.-A.; Vogt, D.; Gasda, P.; Schröder, S.; Ollila, A.; Cousin, A.; Udry, A.; Frydenvang, J.; Beyssac, O.; Clavé, E.; Clegg, S.M.; Delapp, D.; Gasnault, O.; Legett, C.; Maurice, S.; Pilleri, P..; Wiens, R.C.; the SuperCam Instrument Team Machine Learning Trace Element Quantification for SuperCam Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) and Implications for Rocks and Return Samples from Jezero Crater, Mars. Spectrochim. Acta B 2025, submitted.

- Garczynski, B.J.; Horgan, B.H.N.; Johnson, J.R.; Rice, M.S., Mandon, L.; Chide, B.; Bechtold, A.; Beck, P.; Bell, J.F.; Dehouck, E.; Fairén, A.G.; Gómez, F.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Paar, G.; Sephton, M.A.; Simon, J.I.; Traxler, C.; Vaughan, A.; Wiens, R.C.; Bertrand, T.; Beyssac, O.; Brown, A.J.; Cardarelli, E.L.; Cloutis, E.A.; Duflot, L.; Flannery, D.T.; Gasda, P.; Hayes, A.G.; Herd, C.D.K.; Kah, L.; Kinch; Lanza, N.; Merusi, M.; Million, C.C.; Núñez, J.I.; Ollila, A.M.; Royer, C.; St. Clair, M.; Tate, C.; Yanchilina, A. Rock coatings as evidence for late surface alteration on the floor of Jezero crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2025, in revision.

- Gasda, P.J.; Haldeman, E.B.; Wiens, R.C.; Rapin, W.; Bristow, T.F.; Bridges, J.C.; Schwenzer, S.P.; Clark, B.; Herkenhoff, K.; Frydenvang, J.; Lanza, N.L.; Maurice, S.; Clegg, S.; Delapp, D.M.; Sanford, V.L.; Bodine, M.R.; McInroy, R. In situ detection of boron by ChemCam on Mars. Geophys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 44. [CrossRef]

- Gasda, P.; Anderson, R.B.; Cousin, A.; Forni, O.; Clegg, S.M.; Ollila, A.M.; Lanza, N.; Lamm, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Maurice, S.; Gasnault, O.; Beal, R.; Reyes-Newell, A.; Delapp, D. Quantification of manganese in ChemCam Mars and laboratory spectra using a multivariate model. Spectrochim. Acta B 2021, 181. [CrossRef]

- Gasda, P.J.; Lanza, N. L.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Lamm, S. N.; Cousin, A.; Anderson, R.; Forni, O.; Swanner, E.; L’Haridon, J.; Frydenvang, J.; Thomas, N.; Stein, N.; Fischer, W. W.; Hurowitz, J.; Sumner, D.; Rivera-Hernández, F.; Crossey, L.; Ollila, A.; Essunfeld, A.; Newsom, H. E.; Clark, B.; Wiens, R. C.; Gasnault, O.; Clegg, S. M.; Maurice, S.; Delapp, D.; Reyes-Newell, A. Manganese-rich sandstones as an indicator of ancient oxic lake water conditions in Gale crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2024, 129, e2023JE007923. [CrossRef]

- Gellert, R.; Clark, B.C., III; the MSL and MER Science Teams In situ compositional measurements of rocks and soils with the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer on NASA’s Mars rovers. Elements 2015, 11, 39-44. [CrossRef]

- Golombek, M.P.; Grant, J.A.; Crumpler, L.S.; Greeley, R.; Arvidson, R.E.; Bell, J.F., III; Weitz, C.M.; Sullivan, R.; Christensen, P.R.; Soderblom, L.A.; Squyres, S.W. Erosion rates at the Mars Exploration Rover landing sites and long-term climate change on Mars, J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2006, 111, E12S10. [CrossRef]

- Grotzinger, J.P.; Crisp, J.; Vasavada, A.R.; Anderson, R.C.; Baker, C.J.; Barry, R.; Blake, D.F.; Conrad, P.; Edgett, K.S.; Ferdowski, B.; Gellert, R.; Gilbert, J.B.; Golombek, M.; Gomez-Elvira, J.; Hassler, D.M.; Jandura, L.; Litvak, M.; Mahaffy, P.; Maki, J.; Meyer, M.; Malin, M.C.; Metrofanov, I.; Simmonds, J.J.; Vaniman, D.; Welch, R.V.; Wiens, R.C. Mars Science Laboratory Mission and Science Investigation, Spa. Sci. Rev. 2012, 170, 5-56. [CrossRef]

- Grotzinger, J.P.; Gupta, S.; Rubin, D.M.; Schieber, J.; Sumner, D.Y.; Stack, K.M.; Vasavada, A.R.; Arvidson, R.E.; Calef, F. III; Edgar, L.; Fischer, W.F.; Grant, J.A.; Kah, L.C.; Lamb, M.P.; Lewis, K.W.; Mangold, N.; Minitti, M.E.; Palucis, M.; Rice, M.; Siebach, K.; Williams, R.M.E.; Yingst, R.A.; Blake, D.; Blaney, D.; Conrad, P; Crisp, J.; Dietrich, W.E.; Dromart, G.; Edgett, K.S.; Ewing, R.C.; Gellert, R.; Griffes, J.; Hurowitz, J.A.; Kocurek, G.; Mahaffy, P.; Malin, M.C.; McBride, M.J.; McLennan, S.M.; Mischna, M.; Ming, D.; Milliken, R.; Newsom, H.; Oehler, D.; Parker, T.J.; Vaniman, D.; Wiens, R.C.; Wilson, S.A. Deposition, exhumation, and paleoclimate of an ancient lake deposit, Gale crater, Mars. Science 2015, 350, aac7575. [CrossRef]

- l’Haridon, J.; Mangold, N.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Johnson, J.R.; Rapin, W.; Forni, O.; Cousin, A.; Payré, V.; Dehouck, E.; Nachon, M.; Le Deit, L.; Gasnault, O.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C. Chemical variability in mineralized veins observed by ChemCam on the lower slopes of Mount Sharp in Gale Crater, Mars. Icarus 2018, 311, 69-86. [CrossRef]

- Head, J.W.; Mustard, J.F.; Kreslavsky, M.A.; Milliken, R.E.; Marchant, D.R. Recent ice ages on Mars. Nature 2003, 426(6968), 797-802. [CrossRef]

- Horgan, B.H.N.; Anderson, R.B.; Dromart, G.; Amador, E.S.; Rice, M.S. The mineral diversity of Jezero crater: Evidence for possible lacustrine carbonates on Mars. Icarus 2020 339, . [CrossRef]

- Hurowitz, J.A.; Tice, M.M.; Allwood, A.C.; Cable, M.L.; Hand, K.P.; Murphy, A.E.; Uckert, K.; Bell, J.F., III; Bosak, T.; Broz, A.P.; Clave, E.; Cousin, A.; Davidoff, S.; ,Dehouck, E.; Farley, K.A.; Gupta, S.; Hamran, S-E; Hickman-Lewis, K.; Johnson, J.R.; Jones, A.J.; Jones, M.W.M.; Jørgensen, P.S.; Kah, L.C.; Kalucha, H.; Kizovski, T.V.; Klevang, D.A.; Liu, Y.; McCubbin, F. M.; Moreland, E.L.; Paar, G.; Paige, D.A.; Pascuzzo, A.C.; Rice, M.S.; Schmidt, M.E.; Siebach, K.L.; Siljeström, S.; Simon, J.I.; Stack, K.M.; Steele, A.; Tosca, N.J.; Treiman, A.H.; VanBommel, S.J.; Wade, L.A.; Weiss, B.P.; Wiens, R.C.; Williford, K.H.; Barnes, R.; Barr, P.A.; Bechtold, A.; Beck, P.; Benzerara, K.; Bernard, S.; Beyssac, O.; Bhartia. R.; Brown, A.J.; Caravaca, G.; Cardarelli, E.L.; Cloutis, E.A.; Fairén, A.G.; Flannery, D.T.; Fornaro, T.; Fouchet, T.; Garczynski, B.; Goméz, F.; Hausrath, E.M.; Heirwegh, C.M.; Herd, C.D.K.; Huggett, J.E.; Jørgensen, J.L.; Li, A.Y.; Maki, J.N.; Mandon, L.; Mangold. N.; Manrique-Martinez, J.A.; Martínez-Frias, J.; Núñez, J.I.; O’Neil, L.P.; Orenstein, B.J.; Phelan, N.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Russell, P.; Schulte, M.D.; Scheller, E.; Sharma, S.; Shuster, D.L.; Srivastava, A.; Wogsland, B.V.; Wolf, Z.U. Redox-Driven Mineral and Organic Associations in Jezero Crater, Mars, Science 2025, accepted.

- Johnson, J.R.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Bell, J.F., III; Wiens, R.C.; Maurice, S.; Gasnault, O. Progress on iron meteorite detections by the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover. 51st Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2020, 1136, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2020/pdf/1136.pdf.

- Lanza, N.L.; Wiens, R.C.; Arvidson, R.E.; Clark, B.C.; Fischer, W.W.; Gellert, R.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Hurowitz, J.A.; McLennan, S.M.; Morris, R.V.; Rice, M.S.; Bell, J.F., III; Berger, J.A.; Blaney, D.L.; Bridges, N.T.; Calef, F. III; Campbell, J.L.; Clegg, S.M.; Cousin, A.; Edgett, K.S.; Fabre, C.; Fisk, M.R.; Forni, O.; Frydenvang, J.; Hardy, K.R.; Hardgrove, C.; Johnson, J.R.; Lasue, J.; Le Mouelic, S.; Malen, M.C.; Mangold, N.; Martin-Torres, J.; Maurice, S.; McBride, M.J.; Ming, D.W.; Newsom, H.E.; Schroeder, S.; Thompson, L.M.; Treiman, A.H.; VanBommel, S.; Vaniman, D.T.; Zorzano, M.-P. Oxidation of manganese in an ancient aquifer, Kimberley formation, Gale crater, Mars. Geophys Res. Letters 2016, 43, 7398-7407. [CrossRef]

- Lasue J.; Wiens, R.C.; Clegg, S.M.; Vaniman, D.T.; Joy, K.H.; Humphries, S.; Mezzacappa, A.; Melikechi, N.; McInroy, R.E.; Bender, S. Laser induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) for lunar exploration. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2012, 117, E01002. [CrossRef]

- Lasue, J.; Clegg, S.M.; Forni, O.; Cousin, A.; Wiens, R.C.; Lanza, N.; Mangold, N.; Le Deit, L.; Fabre, C.; Gasnault, O.; Maurice, S.; Blaney, D.; Johnson, J.R.; Le Mouelic, S.; Berger, J.; Payré, V.; Nachon, M.; Goetz, W. Observation of > 5 wt. % zinc at the Kimberley outcrop, Gale crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2016, 121, 338–352. [CrossRef]

- Lasue, J.; Cousin, A.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Wiens, R.C.; Gasnault, O; Rapin, W.; Schroeder, S.; Ollila, A.; Fabre, C.; Mangold, N.; Berger, G.; Le Mouelic, S.; Dehouck, E.; Forni, O.; Maurice, S.; Anderson, R.; Bridges, N.; Clark, B.; Clegg, S.M.; d’Uston, C.; Goetz, W.; Johnson, J.; Lanza, N.; Madsen, M.B.; Melikechi, N.; Mezzacappa, A.; Newsom, H.; Sautter, V.; Martin-Torres, J.; Zorzano, M.P.; the MSL Science Team Martian eolian dust probed by ChemCam. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45. [CrossRef]

- Lasue, J.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Cousin, A.; Forni, O.; Anderson, R.; Beck, P.; Clegg, S.M.; Dehouck, E.; Frydenvang, J.; Gasda, P.; Gasnault, O.; Hausrath, E.; Le Mouelic, S.; Maurice, S.; Pilleri, P.; Rapin, W.; Wiens, R.C.; the SuperCam Team Comparison of dust between Gale and Jezero. 53rd Lunar Planet Sci. Conf. 2022, 1758. https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2022/pdf/1758.pdf.

- Le Deit, L.; Anderson, R.B.; Blaney, D.L.; Clegg, S.M.; Cousin, A.; Dromart, G.; Fabre, C.; Fisk, M.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Lanza, N.; Lasue, J.; Le Mouelic, S.; Mangold, N.; Maurice, S.; McLennan, S.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Nachon, M.; Payre, V.; Rapin, W.; Rice, M.; Sautter, V.; Schroeder, S.; Stack, K.M.; Sumner, D.; Wiens, R.C. The potassic sedimentary rocks in Gale crater, Mars, as seen by ChemCam on board Curiosity. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2016, 121. [CrossRef]

- Legett, C., IV; Newell, R.T.; Reyes-Newell, A.L.; Nelson, A.E.; Bernardi, P.; Bener, S.C.; Forni, O.; Venhaus, D.M.; Clegg, S.M.; Ollila, A.M.; Pilleri, P.; Sridhar, V.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C. Optical calibration of the SuperCam instrument body unit spectrometers. Applied Optics 2022, 61, 2967. [CrossRef]

- Leveille, R.J.; Cousin, A; Lanza, N.; Ollila, A.; Wiens, R.C.; Mangold, N.; Forni, O.; Bridges, J.; Berger, G.; Clark, B.; Fabre, C.; Siebach, K.; Anderson, R.B.; Grotzinger, J.; Leshin, L.; Maurice, S. Chemistry of fracture-filling raised ridges in Yellowknife Bay, Gale crater: Windows in to past aqueous activity and habitability on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2014, 119, 2398-2415. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ling, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Fu, X.; Qiao, L.; Liu, P.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Xin, Y.; Shi, E.; Cao, H.; Tian, S.; Wan, S.; Bai, H.; Liu, J. Aqueous alteration of the Vastitas Borealis Formation at the Tianwen-1 landing site. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3(1), 280 . [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, R.; Rao, W.; Cui, X.; Geng, Y.; Jia, Y.; Huang, H.; Ren, X.; Yan, W.; Zeng, X.; Wen, W.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Fu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Dong, J.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Zuo, W.; Su, Y.; Kong, D.; Zhang, H. Geomorphic contexts and science focus of the Zhurong landing site on Mars. Nat. Astron. 2022, 6(1), 65-71 . [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qin, X.; Ren, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, X.; Wu, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ouyang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Head, J.W.; Li, C. Martian dunes indicative of wind regime shift in line with end of ice age. Nature 2023, 620(7973), 303-309, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, W.; Qi, H.; Ren, X.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Yan, Z; Liu, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z; Li, C.; Shu, R. Development and Testing of the MarSCoDe LIBS Calibration Target in China’s Tianwen-1 Mars Mission. Spa. Sci. Rev. 2023, 219(5), 43. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y. Y. S.; Pan, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y.; Wan, W.; Zou, Y. Zhurong reveals recent aqueous activities in Utopia Planitia, Mars. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8(19), . [CrossRef]

- Lodders, K.; Fegley, B., Jr. The Planetary Scientist’s Companion. Oxford University Press 1998, 400 pp.

- Lopez-Reyes, G.; Manrique, J.-A.; Clavé, E.; Ollila, A.; Beyssac, O.; Pilleri, P.; Bernard, S.; Dehouck, E.; Veneranda, M.; Sharma, S.K.; Nachon, M.; Aramendia, J.; Forni, O.; Rull, F.; Acosta-Maeda, T.; Brown, A.; Angel, S.M.; Castro, K.; Cloutis, E.; Coloma, L.; Comellas, J.; Delapp, D.; Jakube, R.; Julve-Gonzalez, S.; Kelly, E.; Madariaga, J.M.; Montagnac, G.; Poblacion, I.; Schröder, S.; Reyes-Rodriguez, I.; Wolf, Z.U.; Maurice, S.; Gasnault, O.; Clegg, S.; Cousin, A.; Wiens, R.C.; the SuperCam Raman Working Group; the SuperCam Operations Team SuperCam Raman activities at Jezero crater, Mars: Observational strategies, data processing, and mineral detections during the first 1000 sols. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2025, submitted.

- Luo, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Shu, R. Alkali trace elements observed by MarSCoDe LIBS at Zhurong landing site on Mars: Quantitative analysis and its geological implications. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2024, 129(7), . [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Ren, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Hu, G.; Han, S.; Shu, R. Quantification and geological implications of manganese, barium, and copper observed by MarSCoDe LIBS at Zhurong landing site on Mars. Icarus 2025, submitted.

- Madariaga, J.M.; Aramendia, J.; Arana, G.; Gomez-Nubla, L.; Fdez-Ortiz de Vallejuelo, S.; Castro, K.; Garcia-Florentino, C.; Maguregui, M.; Torre-Fdez, I.; Manrique, J.A.; Lopez-Reyes, G.; Moros, J.; Cousin, A.; Maurice, S.; Ollila, A.M.; Wiens, R.C.; Rull, F.; Laserna, J.; Garcia-Baonza, V.; Madsen, M.; Forni, O.; Lasue, J.; Clegg, S.M.; Robinson, S.; Bernardi, P.; Cais, P.; Martinez-Frias, J.; Beck, P.; Bernard, S.; Bernt, M.H.; Cloutis, E.; Beyssac, O.; Drouet, C.; Dubois, B.; Dromart, G.; Fabre, C.; Gasnault, O.; Gontijo, I.; Johnson, J.R.; Medina, J.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Montagnac, G.; Sautter, V.; Sharma, S.K.; Veneranda, M.; Willis, P.A. Homogeneity assessment of the SuperCam calibration targets. Chimica Acta 2022, 1209. [CrossRef]

- Malin, M.C.; Edgett, K.S. Sedimentary rocks of early Mars. Science 2000, 290, 1927-1937, . [CrossRef]

- Mandon, L.; Forni, O.; Mangold, N.; Wiens, R.C.; Manelski, H.; Wolf, U.; Dehouck, E.; Beck, P.; Beyssac, O.; Barnes, J.R.; Jones, A.; Johnson, R.; Garczynski, B.; Clavé, E.; Bedford, C.; Schroeder, S.; Royer, C.; Udry, A.; Cousin, A.; Bell, J.F., III Diagenetically altered fine sediments at Neretva Vallis, Mars. In preparation 2025. (use LPSC abstract if not published in time).

- Manelski, H.T.; Wiens, R.C.; Schröder, S.; Hansen, P.B.; Bousquet, B.; Clegg, S.; Martin, N.D.; Nelson, A.E.; Martinez, R.K.; Ollila, A.M.; Cousin, A. LIBS Plasma Diagnostics with SuperCam on Mars: Implications for Quantification of Elemental Abundances. Spectrochim. Acta B 2024, 222, . [CrossRef]

- Mangold, N.; Thompson, L.; Forni, O.; Fabre, C.; Le Deit, L.; Wiens, R.C.; Williams, A.; Williams, R.; Anderson, R.B.; Blaney, D.L.; Calef, F.; Cousin, A.; Clegg, S.M.; Dromart, G.; Dietrich, W.; Edgett, K.S.; Fisk, M.; Gasnault, O.; Gellert, R.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Kah, L.; Le Mouelic, S.; McLennan, S.M.; Maurice, S.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Newsom, H.; Palucis, M.; Rapin, W.; Sautter, V.; Stack, K.; Sumner, D.; Yingst, A. Composition of conglomerates analyzed by the Curiosity rover: Implications for Gale crater crust and sediment sources. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2016, 121, 353-387. [CrossRef]

- Mangold, N.; Williams, A.; Clegg, S.; Gasnault, O.; Forni, O.; Ming, D.; Gellert, R; McLennan, S.; Cousin, A.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Wiens, R.C.; Sumner, D.; Sautter, V.; Schmidt, M.E.; Fisk, M. Classification scheme for sedimentary and igneous rocks in Gale crater, Mars. Icarus 2017, 284, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Mangold, N.; Dehouck, E.; Fedo, C.; Forni, O.; Achilles, C.; Bristow, T.; Frydenvang, J.; Gasnault, O.; L’Haridon, J.; Le Deit, L.; Maurice, S.; McLennan, S.M.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Morrison, S.; Newsom, H.E.; Rampe, E.; Rivera-Hernandez, F.; Salvatore, M.; Wiens, R.C. Chemical alteration of fine-grained sedimentary rocks at Gale crater. Icarus 2019, 321, 619-631. [CrossRef]

- Mangold, N.; Gupta, S.; Gasnault, O.; Dromart, G.; Tarnas, J.D.; Sholes, S.F.; Horgan, B.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Brown, A.J.; Le Mouelic, S.; Yingst, R.A.; Bell, J.F.; Beyssac, O.; Bosak, T.; Calef, F., III; Ehlmann, B.L.; Farley, K.A.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Hickman-Lewis, K.; Holm-Alwmark, S.; Kah, L.C.; Martinez-Frias, J.; McLennan, S.M.; Maurice, S.; Nunez, J.I.; Ollila, A.M.; Pilleri, P.; Rice, J.W., Jr.; Rice, M.; Simon, J.I.; Shuster, D.L.; Stack, K.M.; Sun, V.Z.; Treiman, A.H.; Wiess, B.P.; Wiens, R.C.; Williams, A.J.; Williams, N.R.; Williford, K.H.; the Mars 2020 Science Team Evidence for a delta-lake system and ancient flood deposits at Jezero crater, Mars, from the Perseverance rover. Science 2021, 10.1126/science.abl4051.

- Manrique, J.A.; Lopez-Reyes, G.; Cousin, A.; Rull, F.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Madsen, M.B.; Madariaga, J.M.; Gasnault, O.; Aramendia, J.; Arana, G.; Beck, P.; Bernard, S.; Bernardi, P.; Bernt, M.H.; Beyssac, O.; Cais, P.; Castro, C.; Castro, K.; Clegg, S.; Cloutis, E.; Dromart, G.; Drouet, C.; Dubois, B.; Fabre, C.; Fernandez, A.; Garcia-Baonza, V.; Gontijo, I.; Johnson, J.; Laserna, J.; Lasue J.; Madsen, S.; Mateo-Marti, E.; Medina, J.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Montagnac, G.; Moros, J.; Ollila, A.M.; Ortega, C.; Prieto-Ballesteros, O.; Reess, J.M.; Robinson, S.; Rodriguez, J.; Saiz,, J.; Sanz, J,.A.; Sard, I.; Sautter, V.; Sobron, P.; Veneranda, M. SuperCam calibration targets: Design and development. Spa. Sci. Rev. 2020, 216, 138. [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.D.; Manelski, H.T.; Wiens, R.C.; Clegg, S.; Hansen, P.B.; Schröder; S.; Chide, B. LIBS Peak Broadening in Soils on Mars. 55th Lunar Planet Sci. Conf., 2024, 1151, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2024/pdf/1151.pdf.

- Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Saccoccio, M.; Barraclough, B.; Gasnault, O.; Forni, O.; Mangold, N.; Baratoux, D.; Bender, S.; Berger, G.; Bernardin, J.; Berthé, M.; Bridges, N.; Blaney, D.; Bouyé, M.; Cais, P.; Clark, B.; Clegg, S.; Cousin, A.; Cremers, D.; Cros, A.; DeFlores, L.; Derycke, C.; Dingler, B.; Dromart, G.; Dubois, B.; Dupieux, M.; Durand, E.; d’Uston, L.; Fabre, C.; Faure, B.; Gaboriaud, A.; Gharsa, T.; Herkenhoff, K.; Kan, E.; Kirkland, L.; Kouach, D.; Lacour, J.-L.; Langevin, Y.; Lasue, J.; Le Mouélic, S.; Lescure, M.; Lewin, E.; Limonadi, D.; Manhes, G.; Mauchien, P.; McKay, C.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Michel, Y.; Miller, E.; Newsom, H.E.; Orttner, G.; Paillet, A.; Pares, L.; Parot, Y.; Perez, R.; Pinet, P.; Poitrasson, F.; Quertier, B.; Sallé, B; Sotin, C.; Sautter, V;. Seran, H.; Simmonds, J.J.; Sirven, J.-B.; Stiglich, R.; Streibig, N.; Thocaven, J.-J.; Toplis, M.; Vaniman, D. The ChemCam Instruments on the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Rover: Science Objectives and Mast Unit. Spa. Sci. Rev. 2012, 170, 95-166. [CrossRef]

- Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Bernardi, P.; Cais, P.; Robinson, S.; Nelson, T.; Gasnault, O.; Reess, J.-M.; Deleuze, M.; Rull, F.; Manrique, J.-A.; Abbaki, S.; Anderson, R.B.; André, Y.; Angel, S.M.; Arana, G.; Battault, T.; Beck, P.; Benzerara, K.; Bernard, S.; Beyssac, O.; Bonafous, M.; Bousquet, B.; Boutillier, M.; Cadu, A.; Castro, K.; Chapron, F.; Chide, B.; Clark, K.; Clegg, S.; Cloutis, E.; Collin, C.; Cordoba, E.C.; Cousin, A.; Dameury, J.-C.; D’Anna, W.; Daydou, P.; Deflores, L.; Dehouck, E.; Delapp, D.; De Los Santos, G.; Donny, C.; Dromart, G.; Dubois, B.; Dufour, A.; Dupieux, M.; Egan, M.; Ervin, J.; Fabre, C.; Fau, A.; Fischer, W.; Forni, O; Fouchet, T.; Frydenvang, J.; Gauffre, S.; Gauthier, M.; Gharakanian, V.; Gilard, O.; Gontijo, I.; Gonzales, R.; Granena, D.; Grotzinger, J.; Khodja, R.H.; Heim, M.; Hello, Y.; Hervet, G.; Humeau, O.; Jacob, X.; Jacquinod, S.; Johnson, J.R.; Kouach, D.; Lacombe, G.; Lanza, N.; Lapauw, L.; Laserna, J.; Lasue, J.; Le Deit, L.; Le Mouelic, S.; Lecomte, E.; Lee, Q.-M.; Legett, C., IV; Leveille, R.; Lewin, E.; Lorenz, R.; Lucero, B.; Madariaga, J.M.; Madsen, S.; Madsen, M.; Mangold, N.; Manni, F.; Mariscal, J.-F.; Martinez-Frias, J.; Mathieu, K.; Mathon, R.; McCabe, K.P.; McConnochie, T.; McLennan, S.; Mekki, J.; Melikechi, N.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Michau, Y.; Michel, Y.; Michel, J.M.; Mimoun, D.; Misra, A.; Montagnac, G.; Montaron, C.; Montmessin, F.; Mousset, V.; Morizet, Y.; Murdoch, N.; Newell, R.T.; Newsom, H.; Nguyen Tuong, N.; Ollila, A.M.; Orttner, G.; Oudda, L.; Pares, L.; Parisot, J.; Parot, Y.; Perez, R.; Pheav, D.; Picot, L.; Pilleri P.; Pilorget, C.; Pinet, P.; Pont, G.; Poulet, F.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Quertier, B.; Rambaud, D.; Rapin, W.; Roucayrol, L.; Royer, C.; Ruellan, M.; Sandoval, B.F.; Sautter, V.; Schoppers, M.J.; Schroeder, S.; Seran, H.-C.; Sharma, S.K.; Sobron, P.; Sodki, M.; Sournac, A.; Sridhar, V.; Standarovski, D.; Storms, S.; Streibig, N.; Tatat, M.; Toplis, M.; Torre-Fdez, I.; Toulemont, N.; Velasco, C.; Venhaus, D.; Virmontois, C; Viso, M.; Willis, P.; Wong, K.W. The SuperCam instrument suite on the Mars 2020 rover: Science objectives and mast-unit description. Spa. Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 47. [CrossRef]

- McCanta, M.C.; Dobosh, P.A.; Dyar, M.D.; Newsom, H.E. Testing the veracity of LIBS analyses on Mars using the LIBSSIM program. Planet. Spa. Sci. 2013, . [CrossRef]

- McSween, H.Y.; Ruff, S.W.; Morris, R.V.; Bell, J.F. III; Herkenhoff, K.; Gellert, R.; Stockstill, K.R.; Tornabene, L.L.; Squyres, S.W.; Crisp, J.A.; Christensen, P.R.; McCoy, T.J.; Mittlefehldt, D.W.; Schmidt, M. Alkaline volcanic rocks from the Columbia Hills, Gusev crater,.

- Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2006, 111, E09S91. [CrossRef]

- Melikechi, N.; Mezzacappa, A.; Cousin, A.; Lanza, N.L.; Clegg, S.M.; Wiens, R.C.; Berger, G.; Maurice, S.; Bender, S.; Forni, O.; Delapp, D.; Lasue, J.; Gasnault, O.; Newsom, H.; Ollila, A.M.; Lewin, E.; Breves, E.A.; Dyar, M.D.; Frydenvang, J.; Blaney, D.; Clark, B.C.; the MSL Science Team Correcting for variable-target distances of ChemCam LIBS measurements using emission lines of martian dust spectra. Spectrochim. Acta B 2014, 96C, 51-60. [CrossRef]

- MEPAG Mars Scientific Goals, Objectives, Investigations, and Priorities: 2005, 31 p. white paper posted August, 2005 by the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG) at http://mepag.jpl.nasa.gov/reports/index.html.

- Meslin, P.-Y.; Gasnault, O.; Forni, O.; Schrӧder, S.; Cousin, A.; Berger, G.; Clegg, S.M.; Lasue, J.; Maurice, S.; Sautter, V.; Le Mouelic, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Fabre, C.; Goetz, W.; Bish, D.; Mangold, N.; Ehlmann, B.; Lanza, N.; Harri, A.-M.; Anderson, R.; Rampe, E.; McConnochie, T.H.; Pinet, P.; Blaney, D.; Léveillé, R.; Archer, D.; Barraclough, B.; Bender, S.; Blake, D.; Blank, J.G.; Bridges, N.; Clark, B.C.; DeFlores, L.; Delapp, D.; Dromart, G.; Dyar, M.D.; Fisk, M.; Gondet, B.; Grotzinger, J.; Herkenhoff, K.; Johnson, J.; Lacour, J.-L.; Langevin, Y.; Leshin, L.; Lewin, E.; Madsen, M.B.; Melikechi, N.; Mezzacappa, A.; Mishna, M.A.; Moores, J.E.; Newsom, H.; Ollila, A.; Perez, R.; Renno, N.; Sirven, J.-B.; Tokar, R.; de la Torre, M.; d’Uston, L.; Vaniman, D.; Yingst, A.; the MSL Science Team Soil diversity and hydration as observed by Chemcam at Gale crater, Mars. Science 2013, 341. [CrossRef]

- Meslin, P.-Y.; Forni, O.; Loche, M.; Fabre, S.; Lanza, N.; Gasda, P.; Treiman, A.; Berger, J.; Cousin, A.; Gasnault, O.; Rapin, W.; Lasue, J.; Mangold, N.; Dehouck, E.; Dromart, G.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R. C. Overview of secondary phosphate facies observed by ChemCam in Gale crater, Mars. EGU General Assembly 2022, EGU22-6613. [CrossRef]

- Mezzacappa, A.; Melikechi, N.; Cousin, A.; Wiens, R.C.; Lasue, J.; Clegg, S.M.; Tokar, R.; Bender, S.; Lanza, N.L.; Maurice, S.; Berger, G.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Dyar, M.D.; Boucher, T.; Lewin, E.; Fabre, C.; the MSL Science Team Application of distance correction to ChemCam LIBS measurements. Spectrochim. Acta B 2016 120, 19. [CrossRef]

- Minitti, M.E.; Kah, L.C.; Yingst, R.A.; Edgett, K.S.; Anderson, R.C.; Beegle, L.W.; Carsten, J.L; Deen, R.G.; Goetz, W.; Hardgrove, C.; Harker, D. E.; Herkenhoff, K.E.; Hurowitz, J.A.; Jandura, L.; Kennedy, M.R.; Kocurek, G.; Krezoski; Kuhn, S.R.; Limonadi, D.; Lipkaman, L.; Madsen, M.B.; Olson T.S.; Robinson, M.L.; Rowland, S.K.; Rubin, D.M.; Seybold, C.; Schieber, J.; Schmidt, M.; Sumner, D.Y.; Tompkins, V.V.; Van Beek, J.K.; Van Beek, T. MAHLI at the Rocknest sand shadow: Science and science-enabling activities, Journal of Geophysical Research Planets 2013, 118(11):2338-2360. [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.V.; Vaniman, D.T.; Blake, D.F.; Gellert, R.; Chipera, S.J.; Rampe, E.B.; Ming, D.W.; Morrison, S.M.; Downs, R.T.; Treiman, A.H.; Yen, A.S.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Achilles, C.N.; Bristow, T.F.; Crisp, J.A.; Des Marais, D.J.; Farmer, J.D.; Fendrich, K.V.; Frydenvang, J.; Graff, T.G.; Morookian, J.-M.; Stolper, E.M.; Schwenzer, S.P. Silicic volcanism on Mars evidenced by tridymite in high-SiO2 sedimentary rock at Gale crater. Proc. National Academy of Sciences 2016, www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1607098113. [CrossRef]

- Mustard, J.F.; Adler, M.; Allwood, A.; Bass, D.S.; Beaty, D.W.; Bell, J.F., III; Brinckerhoff, W.B.; Carr, M.; Des Marais, D.J.; Drake, B.; Edgett, K.S.; Eigenbrode, J.; Elkins-Tanton, L.T.; Grant, J.A.; Milkovich, S.M.; Ming, D.; Moore, C.; Murchie, S.; Onstott, T.C.; Ruff, S.W.; Sephton, M.A.; Steele, A.; Treiman, A. Report of the Mars 2020 Science Definition Team, 154 pp., posted July, 2013, by the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG) 2013, http://mepag.jpl.nasa.gov/reports/MEP/Mars_2020_SDT_Report_Final.pdf.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Origins,Worlds, and Life: A Decadal Strategy for Planetary Science and Astrobiology2023-2032. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nachon, M.; Clegg, S.M.; Mangold, N.; Schroeder, S.; Kah, L.C.; Dromart, G.; Ollila, A.; Johnson, J.; Oehler, D.; Bridges, J.; Le Mouelic, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Anderson, R.; Blaney, D.; Bell, J.F.; Clark, B.; Cousin, A.; Dyar, M.D.; Ehlmann, B.; Fabre, C.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Grotzinger, J.; Lasue, J.; Lewin, E.; Leveillé, R.; McLennan, S.; Maurice, S.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Rice, M.; Stack, K.; Vaniman, D.; Wellington, D.; the MSL Science Team Calcium sulfate veins characterized by the ChemCam instrument at Gale crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2014, 119, 1991-2016. [CrossRef]

- Nellessen, M.A.; Gasda, P.; Crossey, L.; Peterson, E.; Ali, A.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Hao, M.; Spilde, M.; Newsom, H.; Lanza, N.; Reyes-Newell, A.; Legett, S.; Das, D.; Delapp, D.; Yeager, C.; Labouriau, A.; Clegg, S.; Wiens, R.C. Boron adsorption in clay minerals: Implications for martian groundwater chemistry and boron on Mars. Icarus 2023, 401, . [CrossRef]

- Nellessen, M.A.; Newsom, H.E.; Scuderi, L.; Nachon, M.; Rivera-Hernandez, F.; Hughes, E.; Gasda, P.J.; Lanza, N.; Ollila, A.; Clegg, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Frydenvang, J.; Gasnault, O.; Maurice, S.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Cousin, A.; Rapin, W.; Lasue, J.; Forni, O.; L’Haridon, J.; Blaney, D.; Le Deit, L.; Anderson, R.; Essunfeld, A. Identification of Ca-sulfate cemented bedrock and mixed vein-bedrock features using statistical analysis of ChemCam shot-to-shot data. 56th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2025, 2358, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2025/pdf/2358.pdf.

- Nesbitt, H.W.; Young, G.M. Early Proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistries of lutites. Nature 1984 299, 715-717, . [CrossRef]

- Ollila, A.M.; Newsom, H.E.; Clark, B., III; Wiens, R.C.; Cousin, A.; Blank, J.G.; Mangold, N.; Sautter, V.; Maurice, S.; Clegg, S.M.; Gasnault, O.; Forni, O.; Tokar, R.; Lewin, E.; Dyar, M.D.; Lasue, J.; Anderson, R.; McLennan, S.M.; Bridges, J.; Vaniman, D.; Lanza, N.; Fabre, C.; Melikechi, N.; Perrett, G.M.; Campbell, J.L.; King, P.L.; Barraclough, B.; Delapp, D.; Johnstone, S.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Rosen-Gooding, A.; Williams, J.; the MSL Science Team Trace element geochemistry (Li, Ba, Sr, and Rb) using Curiosity’s ChemCam: Early results for Gale crater from Bradbury Landing Site to Rocknest. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2014, 119, 255-285. [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, S.G.; Jessberger, E.K.; Huebers, H.-W.; Schroeder, S.; Rauschenbach, I.; Florek, S.; Neumann, J.; Henkel, H.; Klinkner , S. Miniaturized laser-induced plasma spectrometry for planetary in situ analysis – The case for Jupiter’s moon Europa. Adv. Spa. Res. 2011 48, 764-778. [CrossRef]

- Payre, V.; Fabre, C.; Cousin, A.; Sautter, V.; Wiens, R.C.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Lasue, J.; Ollila, A.; Rapin, W.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Maurice, S.; Nachon, M.; Le Deit, L.; Lanza, N.; Clegg, S.M. Alkali trace elements with ChemCam: Calibration update and geological implications of the occurrence of alkaline rocks in Gale crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2017, 122. [CrossRef]

- Payré, V.; Fabre, C.; Sautter, V.; Cousin, A.; Mangold, N.; Le Deit, L.; Forni, O.; Goetz, W.; Wiens, R.C.; Gasnault, O.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Lasue, J.; Rapin, W.; Clark, B.; Nachon, M.; Lanza, N.; Maurice, S. Copper enrichments in Kimberley formation, Gale crater, Mars: Evidence for a Cu deposit at the source. Icarus 2019, 321, 736-751. [CrossRef]

- Peret, L.; Gasnault, O.; Dingler, R.; Langevin, Y.; Bender, S.; Blaney, D.; Clegg, S.; Clewans, C.; Delapp, D.; Donny, C.; Johnstone, S.; Little, C.; Lorigny, E.; McInroy, R.; Maurice, S.; Mittal, N.; Pavri, B.; Perez, R.; Wiens, R.C.; Yana, C. Restoration of the autofocus capability of the ChemCam instrument onboard the Curiosity rover. SpaceOps Conference 2016, (AIAA 2016-2539). [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Ren, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Zeng, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.;Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, B.; Liu, D.; Guo, L.; Li, K.; Zeng, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, S.; Li, C.; Guo, Z. Modern water at low latitudes on Mars: Potential evidence from dune surfaces. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9(17). [CrossRef]

- Quantin-Nataf, C.; Dehouck, E.; Beck, P.; Bedford, C.; Mandon, L.; Beyssac, O.; Clave, E.; Forni, O.; Udry, A.; Mayhew, L.; Ravanis, E.; Cousin, A.; Wiens, R.C.; Horgan, B.; Simon, J.; Minitti, M.; Poulet, F. Alteration diversity observed in the inner part of Jezero Crater Rim. 56th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2025, 2189, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2025/pdf/2189.pdf.

- Rapin, W.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Laporte, D.; Chauviré, B.; Gasnault, O.; Schroeder, S.; Beck, P.; Bender, S.; Beyssac, O.; Cousin, A.; Dehouck, E.; Drouet, C.; Forni, O.; Nachon, M.; Melikechi, N.; Rondeau, B.; Mangold, N.; Thomas, N. Quantification of water content by laser induced breakdown spectroscopy on Mars. Spectrochim. Acta B 2017a 130, 82-100. [CrossRef]

- Rapin, W.; Bousquet, B.; Lasue, J.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Lacour, J.-L.; Fabre, C.; Wiens, R.C.; Frydenvang, J.; Dehouck, E.; Maurice, S.; Gasnault, O.; Forni, O.; Cousin, A. Roughness effects on the hydrogen signal in laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta B 2017b, 137, 13-22. [CrossRef]

- Rapin, W.; Ehlmann, B.L.; Dromart, G.; Schieber, J.; Thomas, N.H.; Fischer, W.W.; Fox, V.K.; Stein, N.T.; Nachon, M.; Clark, B.C.; Kah, L.C.; Thompson, L.; Meyer, H.A.; Gabriel, T.S.J.; Hardgrove, C.; Mangold, N.; Rivera-Hernandez, F.; Wiens, R.C.; Vasavada, A.R. An interval of high salinity in ancient Gale crater lake, Mars. Nat. Geosci. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rapin, W.; Dromart, G.; Clark, B.C.; Schieber, J.; Kite, E.S.; Kah, L.C.; Thompson, L.M.; Gasnault, O.; Lasue, J.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Gasda, P.J.; Lanza, N.L. Sustained wet–dry cycling on early Mars. Nature 2023, 620, 299–302. [CrossRef]

- Rapin, W.; Maurice, S.; Ollila, A.; Wiens, R.C.; Dubois, B.; Nelson, T.; Bonhomme, L.; Parot, Y.; Clegg, S.; Newell, R.; Ott, L.; Chide, B.; Payre, V.; Bedford, C.; Connell, S.; Manelski, H.; Schröder, S.; Buder, M.; Yana, C.; Bousquet, P. μLIBS: Developing a Lightweight Elemental Micro-Mapper for In Situ Exploration. 55th Lunar Planet Sci. Conf. 2024, 2670, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2024/pdf/2670.pdf.

- Rivera-Hernandez, F.; Sumner, D.Y.; Mangold, N.; Stack, K.M.; Forni, O.; Newsom, H.; Williams, A.; Nachon, M.; L’Haridon, J.; Gasnault, O.; Wiens, R.C.; Maurice, S. Using ChemCam LIBS data to constrain grain size in rocks on Mars: Proof of concept and application to rocks at Yellowknife Bay and Pahrump Hills, Gale crater. Icarus 2019, 321, 82-98. [CrossRef]

- Royer, C. ; Bedford, C.C. ; Johnson, J.R. ; Horgan, B. ; Broz, A. ; Forni, O.; Connell, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Mandon, L.; Kathir, B.S.; Hausrath, E.M.; Udry, A.; Madariaga, J.M.; Beck, P.; Dehouck, E.; Garczynski, B.; Manelski, H.; Klidaras, A.; Clavé, É.; Mayhew, L.; Núñez, J.; Cloutis, E.; Gabriel, T.; Anderson, R.; Ollila, A.; Clegg, S.; Stack, K.M.; Cousin, A.; Beyssac, O.; Simon, J.; Wolf, U.; Maurice, S. Intense alteration on early Mars revealed by high-aluminum rocks at Jezero Crater. Nature Earth and Environment 2024, 5, 671, . [CrossRef]

- Sallé, B.; Lacour, J.-L.; Vors, E.; Fichet, P.; Maurice, S.; Cremers, D.A.; Wiens, R.C. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy for Mars surface analysis: Capabilities at stand-off distance and detection of chlorine and sulfur elements. Spectrochim. Acta B 2004, 59, 1413-1422, . [CrossRef]

- Sallé, B.; Cremers, D.A.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Fichet, P. Evaluation of a compact spectrograph for in-situ and stand-off laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy analyses of geological samples on Mars missions. Spectrochim. Acta B 2005, 60, 805-815, . [CrossRef]

- Sautter, V.; Fabre, C.; Forni, O.; Toplis, M.; Cousin, A.; Ollila, A.M.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Mangold, N.; Le Mouelic, S.; Gasnault, O.; Lasue, J.; Berger, G.; Lewin, E.; Schmidt, M.; Pinet, P.; Baratoux, D.; Ehlmann, B.L.; Bridges, J.; Dyar, M.D.; Clark, B.; the MSL Science Team Igneous mineralogy at Bradbury rise: The first ChemCam campaign. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2014, 119, 30-46. [CrossRef]

- Sautter,, V.; Toplis, M.; Cousin, A.; Forni, O.; Wiens, R.C.; Fabre, C.; Gasnault, O.; Fisk, M.; Maurice, S.; Ollila, A.; Mangold, N.; Le Deit, L.; Beck, P.; Rapin, W.; Pinet, J.; Blank, J.; Clegg, S.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Dyar, M.D.; Newsom, H.; Bridges, N.; Lanza, N.; Le Mouelic, S.; Vaniman, D. In-situ evidence for continental crust on early Mars. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 605-609. [CrossRef]

- Sautter, V.; Toplis, M.J.; Beck, P.; Mangold, N.; Wiens, R.C.; Pinet, P.; Cousin, A.; Maurice, S.; Le Deit, L.; Hewins, R.; Gasnault, O.; Quantin, C.; Forni, O.; Newsom, H.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Wray, J.; Bridges, N.; Payre, V. Magmatic complexity on early Mars as seen through a combination of orbital, in situ, and meteorite data. Lithos 2016, 254-255, 36-52. [CrossRef]

- Scheller, E.L.; Ehlmann, B.L.; Hu, R.; Adams, D.J.; Yung, Y.L. Long-term drying of Mars by sequestration of ocean-scale volumes of water in the crust. Science 2021, 372, 56-62. [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, R.V.L.N.; Goswami, A.; Lohar, K.A.; Raha, B.; Rao, M.V.H.; Gowda, G.; Smaran, T.S.; Kumar, A.S.; Bhuvaneswari, S.; Umesh, S.B.; Sriram, K.V.; Prabkaran, B.; Rethika, T.; Pandey, H.; Malathi, S. Close-range in-situ LIBS (laser induced breakdown spectroscope) experiment aboard the Chandrayaan-3 Pragyaan rover: operations and initial results. 55th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2024, 1135, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2024/pdf/1135.pdf.

- Tanaka, K.L.; Skinner J.A., Jr,; Dohm, J.M.; Irwin III, R.P.; Kolb, E.J.; Fortezzo, C.M.; Platz, T.; Michael, G.G.; Hare, T.M. Geologic map of Mars. Scientific Investigations Map 2014, 3292, scale 1:20,000,000, pamphlet 43 pp. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. Planetary Crusts: Their Origin, Evolution, and Composition. Cambridge University Press 2009, 378 pp.

- Thomas, N.H.; Ehlmann, B.L.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Rapin, W.; Anderson, D.E.; Rivera-Hernandez, F.; Forni, O.; Schroeder, S.; Cousin, A.; Mangold, N.; Gellert, R.; Gasnault, O.; Wiens, R.C. Mars Science Laboratory observations of chloride salts in Gale crater, Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019 46. [CrossRef]

- Treiman, A.H.; Lanza, N.L.; VanBommel, S.; Berger, J.; Wiens, R.C.; Bristow, T.; Johnson, J.; Rice, M.; Hart, R.; McAdam, A.; Gasda, P.J.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Yen, A.S.; Williams, A.J.; Vasavada, A.R.; Vaniman, D.T.; Tu, V.M.; Thorpe, M.T.; Swanner, E.D.; Seeger, C.; Schwenzer, S.P.; Schröder, S.; Rampe, E.B.; Rapin, W.; Ralston, S.; Peretyazhko, T.S.; Newsom, H.E.; Morris, R.V.; Ming, D.W.; Loche, M.; Le Mouélic, S.; House, C.S.; Hazen, R.M.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Gellert, R.; Gasnault, O.; Fischer, W.W.; Essunfeld, A.L.; Downs, R.T.; Downs, G.W.; Dehouck, E.; Crossey, L.J.; Cousin, A.; Comellas, J.M.; Clark, J.V.; Clark, B.C. III, Chipera, S.; Caravaca, G.; Bridges, J.C.; Blake, D.F.; Anderson R.B. Manganese-Iron Phosphate Nodules at the Groken site, Gale Crater, Mars. Minerals 2023, 13, 1122. [CrossRef]

- Udry, A.; Ostwald, A.; Sautter, V.; Cousin, A.; Beyssac, O.; Forni, O.; Dromart, G.; Benzerara, K.; Nachon, M.; Horgan, B.; Mandon, L.; Clavé, E.; Dehouck, E.; Gibbons, E.; Alwmark, S.; Ravanis, E.; Wiens, R. C.; Legett, C.; Anderson, R.; Pilleri, P.; Mangold, N.; Schmidt, M.; Liu, Y.; Núñez, J. I.; Castro, K.; Madariaga, J. M.; Kizovski, T.; Beck, P.; Bernard, S.; Bosak, T.; Brown, A.; Clegg, S.; Cloutis, E.; Cohen, B.; Connell, S.; Crumpler, L.; Debaille, V.; Flannery, D.; Fouchet, T.; Gabriel, T. S. J.; Gasnault, O.; Herd, C. D. K.; Johnson, J.; Manrique, J. A.; Maurice, S.; McCubbin, F. M.; McLennan, S.; Ollila, A.; Pinet, P.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Royer, C.; Sharma, S.; Simon, J. I.; Steele, A.; Tosca, N.; Treiman, A.; the SuperCam team A Mars 2020 Perseverance SuperCam Perspective on the Igneous Nature of the Máaz formation at Jezero crater and link with Séítah, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2023, . [CrossRef]

- Udry, A.; Beyssac, O.; Forni, O.; Clave, E.; Bedford, C.; Beck, P.; Dehouck, E.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Motta, G.; Cousin, A.; Wiens, R.; Simon, J. I.; Poulet, F. Igneous compositions in the rim of Jezero crater using SuperCam data. 56th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2025, 1352, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2025/pdf/1352.pdf.

- Ullan, A.; Zorzano, M.-P.; Martın-Torres, F. J.; Valentın-Serrano, P.; Kahanpaa, H.; Harri, A.-M.; Gomez-Elvira, J.; Navarro, S. Analysis of the wind pattern and pressure fluctuations during one and a half Martian years at Gale Crater. Icarus 2017, 288, 78-87, . [CrossRef]

- Vaniman, D.; Dyar, M.D.; Wiens, R.C.; Ollila, A.; Lanza, N.; Lasue, J.; Rhodes, M.; Clegg, S.M. Ceramic ChemCam Calibration Targets on Mars Science Laboratory. Spa. Sci. Rev. 2012, 170, 229-255. [CrossRef]

- Vasavada, A.R. Mission Overview and Scientific Contributions from the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity Rover After Eight Years of Surface Operations. Spa. Sci. Rev. 2022, 218:14 . [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Di, K.; Peng, M.; Wang, Y.; ...Liu, C. Visual Localization and Topographic Mapping for Zhurong Rover in Tianwen-1 Mars Mission. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2025.

- Wieczorek, M.A.; Broquet, A.; McLennan, S.M.; Rivoldini, A.; Golombek, M.; Antonangeli, D.; Beghein, C.; Giardini, D.; Gudkova, T.; Gyalay, S.; Johnson, C.L.; Joshi, R.; Kim, D.,; King, S.D.; Knapmeyer-Endrun, B.; Lognonné, P.; Michaut, C.; Mittelholz, A.; Nimmo, F.; Ojha, L.; Panning, M.P.; Plesa, A.-C.; Siegler, M.A.; Smrekar, S.E.; Spohn, T.; Banerdt, W.B. InSight Constraints on the Global Character of the Martian Crust. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2022, 127, . [CrossRef]

- Wiens, R.C. MSL Mars ChemCam LIBS spectra 4/5 RDR V1.0 [Dataset]. NASA Planetary Data System 2022, . [CrossRef]

- Wiens, R. C.; Maurice, S. Mars 2020 SuperCam bundle. In NASA planetary data system 2021, . [CrossRef]

- Wiens, R.C.; Cremers, D.A.; Blacic, J.D.; Ritzau, S.M.; Funsten, H.O.; Nordholt, J.E. Elemental and isotopic planetary surface analysis at stand-off distances using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy and laser-induced plasma ion mass spectrometry. 29th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 1998, 1633, https://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/LPSC98/pdf/1633.pdf.

- Wiens, R.C.; Maurice, S.; Barraclough, B.; Saccoccio, M.; Barkley, W.C; Bell, J.F., III; Bender, S.; Bernardin, J.; Blaney, D.; Blank, J.; Bouye, M.; Bridges, N.; Cais, P.; Clanton, R.C.; Clark, B.; Clegg, S.; Cousin, A.; Cremers, D.; Cros, A.; DeFlores, L.; Delapp, D.; Dingler, R.; D’Uston, C.; Dyar, M.D.; Elliott, T.; Enemark, D.; Fabre, C.; Flores, M.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Hale, T.; Hays, C.; Herkenhoff, K.; Kan, E.; Kirkland, L; Kouach, D.; Landis, D.; Langevin, Y.; Lanza, N.; LaRocca, F.; Lasue, J.; Latino, J.; Limonadi, D.; Lindensmith, C.; Little, C.; Mangold, N.; Manhes, G.; Mauchien, P.; McKay, C.; Miller, E.; Mooney, J.; Morris, R.V.; Morrison, L.; Nelson, T.; Newsom, H.; Ollila, A.; Ott, M.; Pares, L.; Perez, R.; Poitrasson, F.; Provost, C.; Reiter, J.W.; Roberts, T.; Romero, F.; Sautter, V.; Salazar, S.; Simmonds, J.J.; Stiglich, R.; Storms, S.; Streibig, N.; Thocaven, J.-J.; Trujillo, T.; Ulibarri, M.; Vaniman, D.; Warner, N.; Waterbury, R.; Whitaker, R.; Witt, J.; Wong-Swanson, B. The ChemCam Instruments on the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Rover: Body Unit and Combined System Performance. Spa. Sci. Rev. 2012, 170, 167-227. [CrossRef]

- Wiens, R.C.; Maurice, S.; Lasue, J.; Forni, O.; Anderson, R.B.; Clegg, S.; Bender, S.; Barraclough, B.L.; Deflores, L.; Blaney, D.; Perez, R.; Lanza, N.; Ollila, A.; Cousin, A.; Gasnault, O.; Vaniman, D.; Dyar, M.D.; Fabre, C.; Sautter, V.; Delapp, D.; Newsom, H.; Melikechi, N.; the ChemCam Team Pre-flight calibration and initial data processing for the ChemCam laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy instrument on the Mars Science Laboratory rover. Spectrochim. Acta B 2013, 82, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Wiens,, R.C.; Maurice, S.; Robinson, S.H.; Nelson, A.E.; Cais, P.; Bernardi, P.; Newell, R.T.; Clegg, S.M.; Sharma, S.K.; Storms, S.; Deming, J.; Beckman, D.; Ollila, A.M.; Gasnault, O.; Auden, E.; Anderson, R.B.; André, Y.; Angel, S.M.; Arana, G.; Beck, P.; Becker, J.; Benzerara, K.; Bernard, S.; Beyssac, O.; Borges, L.; Bousquet, B.; Boyd, K.; Caffrey, M.; Carlson, J.; Castro, K.; Celis, J.; Chide, B.; Clark, K.; Cloutis, E.; Cordoba, E.C.; Cousin, A.; Dale, M.; Deflores, L.; Delapp, D.; Deleuze, M.; Dirmyer, M.; Donny, C.; Dromart, G.; Duran, M.G.; Egan, M.; Ervin, J.; Fabre, C.; Fau, A.; Fischer, W.W.; Forni, O.; Fouchet, T.; Fresquez, R.; Frydenvang, J.; Gasway, D.; Gontijo, I.; Grotzinger, J.; Jacob, X.; Jacquinod, S.; Johnson, J.R.; Klisiewicz, R.A.; Lake, J.; Lanza, N. Laserna, J.; Lasue, J.; Le Mouelic, S.; Legett, C., IV; Leveille, R.; Lewin, E.; Lorenz, R.; Lorigny, E.; Love, S.P.; Lucero, B.; Madariaga, J.M.; Madsen, M.; Madsen, S.; Mangold, N.; Manrique, J.A.; Martinez, J.P.; Martinez-Frias, J.; McCabe, K.P.; McConnochie, T.H.; McGlown, J.M.; McLennan, S.M.; Melikechi, N.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Michel, J.M.; Mimoun, D.; Misra, A.; Montagnac, G.; Montmessin, F.; Mousset, V.; Murdoch, N.; Newsom, H.; Ott, L.A.; Ousnamer, Z.R.; Pares, L.; Parot, Y.; Pawluczyk, R.; Peterson, C.G.; Pilleri, P.; Pinet, P.; Pont, G.; Poulet, F.; Provost, C.; Quertier, B.; Quinn, H.; Rapin, W.; Reess, J.-M.; Regan, A.H.; Reyes-Newell, A.L.; Romano, P.J.; Royer, C.; Rull, F.; Sandoval, B.; Sarrao, J.H.; Sautter, V.; Schoppers, M.J.; Schroeder, S.; Seitz, D.; Shepherd, T.; Sobron, P.; Dubois, B.; Sridhar, V.; Toplis, M.J.; Torre-Fdez, I.; Trettel, I.A.; Underwood, M.; Valdez, A.; Valdez, J.; Venhaus, D.; Willis, P. The SuperCam Instrument Suite on the NASA Mars 2020 Rover: Body Unit and Combined System Tests. Spac. Sci. Rev. 2021a, 217, 4. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11214-020-00777-5.

- Wiens, R.C.; Blazon-Brown, A.; Melikechi, N.; Frydenvang, J.; Dehouck, E.; Clegg, S.M.; Delapp, D.; Anderson, R.B.; Cousin, A.; Maurice, S. Improving ChemCam LIBS Long-Distance Elemental Compositions Using Empirical Abundance Trends. Spectrochim. Acta B 2021b, 182. [CrossRef]

- Wiens, R.C.; Udry, A.; Beyssac, O.; Quantin-Nataf, C.; Mangold, N.; Cousin, A.; Mandon, L.; Bosak, T.; Forni, O.; McLennan, S.M.; Sautter, V.; Brown, A.; Benzerara, K.; Johnson, J.R.; Mayhew, L.; Maurice, S.; Anderson, R.B.; Clegg, S.M.; Crumpler, L.; Gabriel, T.S.J.; Gasda, P.; Hall, J.; Horgan, B.H.N.; Kah, L.; Legett, C., IV; Madariaga, J.M.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Ollila, A.M.; Poulet, F.; Royer, C.; Sharma, S.K.; Siljestrom, S.; Simon, J.I.; Acosta-Maeda, T.E.; Alvarez-Llamas, C.; Angel, S.M.; Arana, G.; Beck, P.; Bernard, S.; Bertrand, T.; Bousquet, B.; Castro, K.; Chide, B.; Clavé, E.; Cloutis, E.; Connell, S.; Frydenvang, J.; Gasnault, O.; Gibbons, E.; Gupta, S.; Hausrath, L.; Jacob, X.; Kalucha, H.; Kelly, E.; Knutsen, E.; Lanza, N.; Laserna, J.; Lasue, J.; Le Mouelic, S.; Leveille, R.; Lopez Reyes, G.; Lorenz, R.; Manrique, J.A.; Martinez-Frias, J.; McConnochie, T.; Melikechi, N.; Mimoun, D.; Montmessin, F.; Moros, J.; Murdoch, N.; Pilleri, P.; Pilorget, C.; Pinet, P.; Rapin, W.; Rull, F.; Schroeder, S.; Shuster, D.J.; Smith, R.J.; Stott, A.; Tarnas, J.; Turenne, N.; Veneranda, M.; Vogt, D.S.; Weiss, B.P.; Willis, P.; Stack, K.M.; Williford, K.H.; Farley, K.A.; the SuperCam Team Compositionally and density stratified igneous terrain in Jezero crater, Mars. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abo3399. [CrossRef]

- Williford, K.H.; Farley, K.A.; Horgan, B.; Garczynski, B.; Treiman, A.H.; Gupta, S.; Jones, A.J.; Siljeström, S.; Cardarelli, E.; Clavé, E.; Mayhew, L.; Osterhout, J.; Ravanis, E.; Stack, K.M.; Fagents, S.; Bedford, C.C.; Beyssac, O.; Bosak, T.; Bykov, S.V.; Flannery, D.; Fouchet, T.; Hand, K.P.; Jones, M.W.M.; Kah, L.; Klidaras, A.; Maki, J.; Mandon, L.; Mangold, N.; Mansbach, E.; McCubbin, F.M.; Simon, J.I.; Srivastava, A.; Tice, M.; Uckert, K.; Wiens, R.C.; Alwmark, S.; Aramendia, J.; Barnes, R.; Beck, P.; Bell, J.F., III; Bernard, S.; Bhartia, R.; Brown, A.J.; Broz, A.; Buckner, D.; Catling, D.; Cloutis, E.; Connell, S.; Corpolongo, A.; Cousin; Crumpler, L.; Czaja, A.; Dehouck, E.; Ehlmann, B.; Fornaro, T.; Forni, O.; Hamran, S.-E.; Haney, N.; Hickman-Lewis, K.; Hug, W.; Hurowitz, J.; Jakubek, R.; Johnson, J.; Koeppel, A.; Madariaga, J.M.; Martínez-Frías, J.; Núñez, J.I.; Orenstein, B.J.; Phua, Y.Y.; Pilorget, C.; Randazzo, N.; Royer, C.; Russell, P.; Scheller, E.; Schmitz, N.; Schröder, S.; Sephton, M.A.; Sharma, Sh.; Sharma, Su.; Shuster, D.; Sinclair, K.; Steele, A.; Tate, C.; Weiss, B.; Williams, A.; Wolf, Z.U.; Yingst , R.A. Carbonated ultramafic rocks in Jezero crater, Mars. Science 2025 accepted.

- Wolf, Z.U.; Madariaga, J.M.; Clegg, S.; Legett, C.; Arana, G.; Gabriel, T.S.J.; Poblacion, I.; Forni, O.; Gasnault, O.; Anderson, R.; Clavé, E.; Schröder, S.; Cousin, A.; Wiens , R.C. Chlorine in Jezero crater, Mars: Detections made by SuperCam. 56th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 2025, 2456. https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2025/pdf/2456.pdf.

- Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Du, J.; Liu, Z.; Yan, X.; Xu, R.; He, Z.; Lin, Y.; Zou, Y. Geological characteristics of China’s Tianwen-1 landing site at Utopia Planitia, Mars. Icarus 2021, 370. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Huang, J.; Kusky, T.; Head, J. W.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Yu, W.; Shi, Y.; Wu, B.; Qian, Y.; Huang, Q.; Xiao, X. Evidence for marine sedimentary rocks in Utopia Planitia: Zhurong rover observations. National Science Review 2023, 10(9), . [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Yan, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Kuang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yu, H.; Yang, F.; Liu, C.; Wang, T.; Li, C.; Jin, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, B.; Wan, W.; Chen, J.; Ni, S.; Ruan, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, Z.; Wan, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Shen, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, B.; Yuan, R.; Bao, T.; Shu, R. The MarSCoDe Instrument Suite on the Mars Rover of China’s Tianwen-1 Mission. Spa. Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 64. [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Qian, Y.; Xiao, L.; Michalski, J.R.; Lia, Y.; Wu, B.; Qiao, L. Geomorphologic exploration targets at the Zhurong landing site in the southern Utopia Planitia of Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2021, 576. [CrossRef]

- Yumoto, K.; Cho, Y.; Kameda, S.; Kasahara, S.; Sugita, S. In-situ measurement of hydrogen on airless planetary bodies using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta B 2023, 205. [CrossRef]

- Zastrow, A.M.; Glotch, T.D. Distinct Carbonate Lithologies in Jezero Crater, Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, X.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang Z.; Xu, W.; Shu, R.; Li, C. Volatile Elements Characterized by MarSCoDe in Materials at Zhurong Landing Site. The Astronomical Journal 2024, 168(4), 150. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Y. S.; Yu, J.; Wei, G.; Pan, L.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, C.; Qang, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, W.; Rao, Y.; Xu, W.; Sun, T.; Chen, F.; Zhang, B.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, S.; Li, X.-Y.; Yu, X.-W.; Qu, S.-Y.; Zhou, D.-S.; Wu, X.; Zeng, X.; Li, X.; Tang, H.; Liu, J. In situ analysis of surface composition and meteorology at the Zhurong landing site on Mars. National Science Review 2023, 10(6). [CrossRef]

| 1 | Wavelengths are given here and elsewhere in the paper as vacuum wavelengths, appropriate for Mars’ thin atmosphere. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).