Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

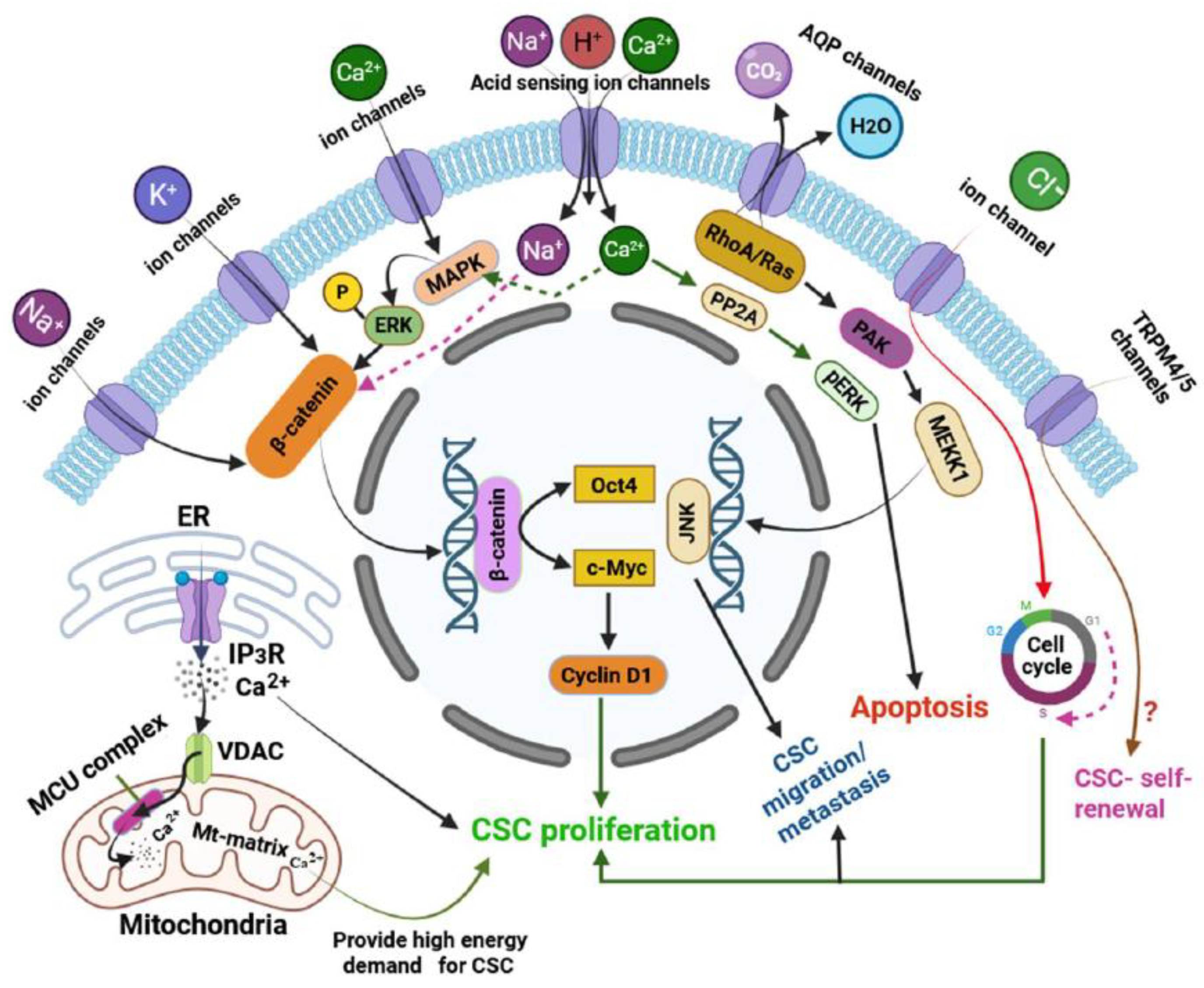

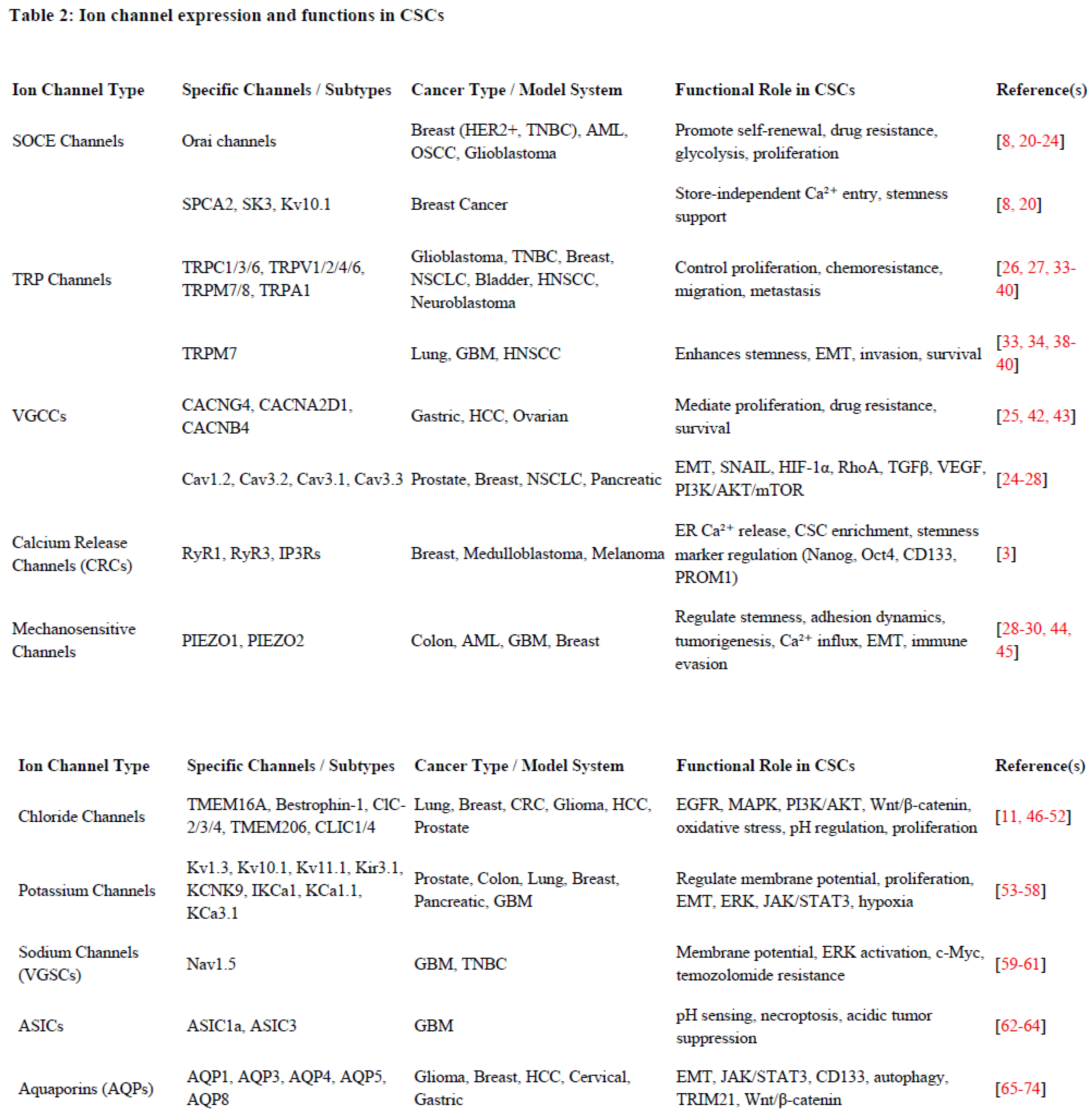

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

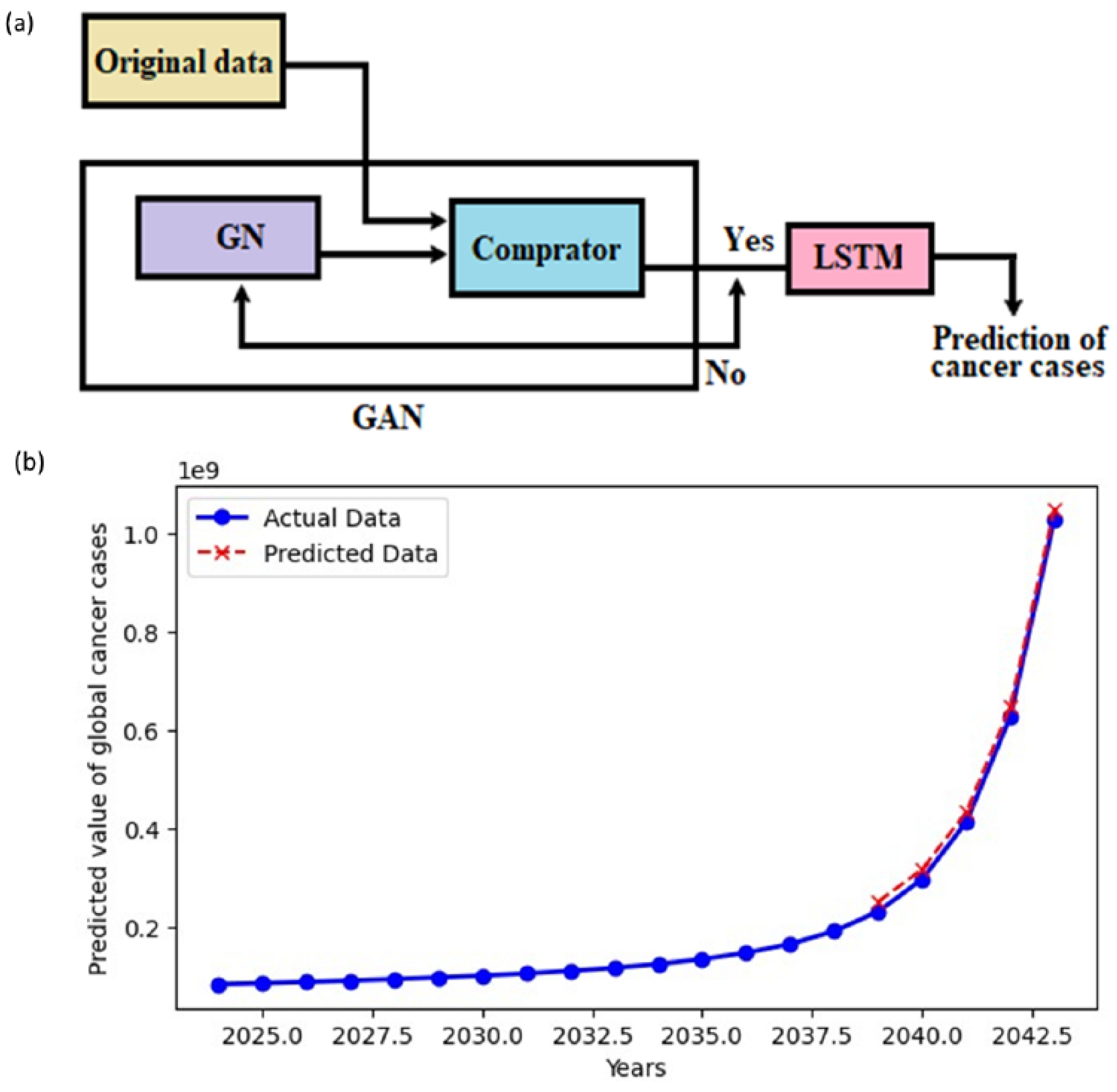

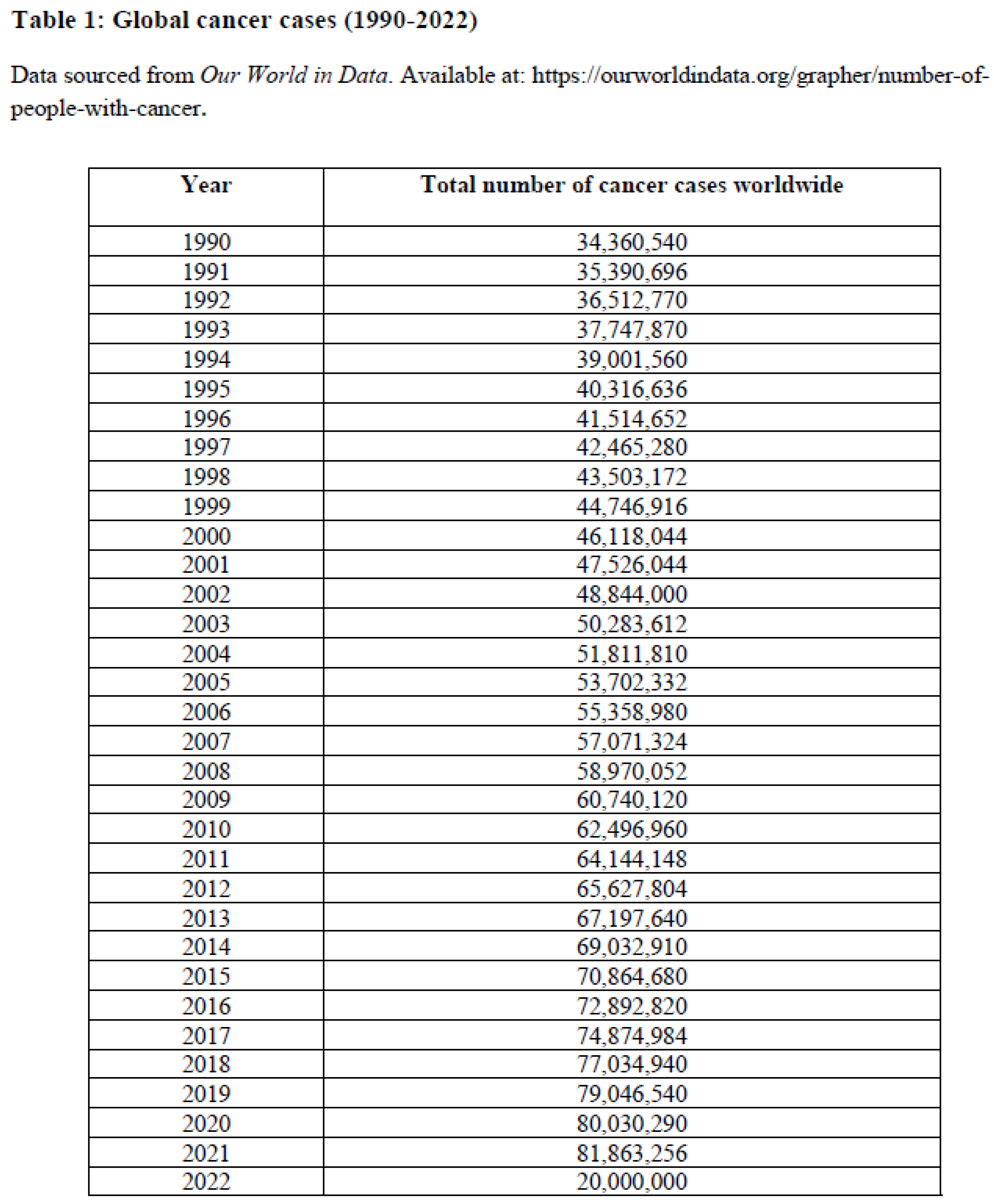

2. AI-Based Generative Prediction of Near-Future Global Cancer Cases

3. Ion Channel Expression Profiles and Their Functions in CSCs

4. Calcium Ion Channels and Their Functions

4.1. SOCE Channels and Their Functions

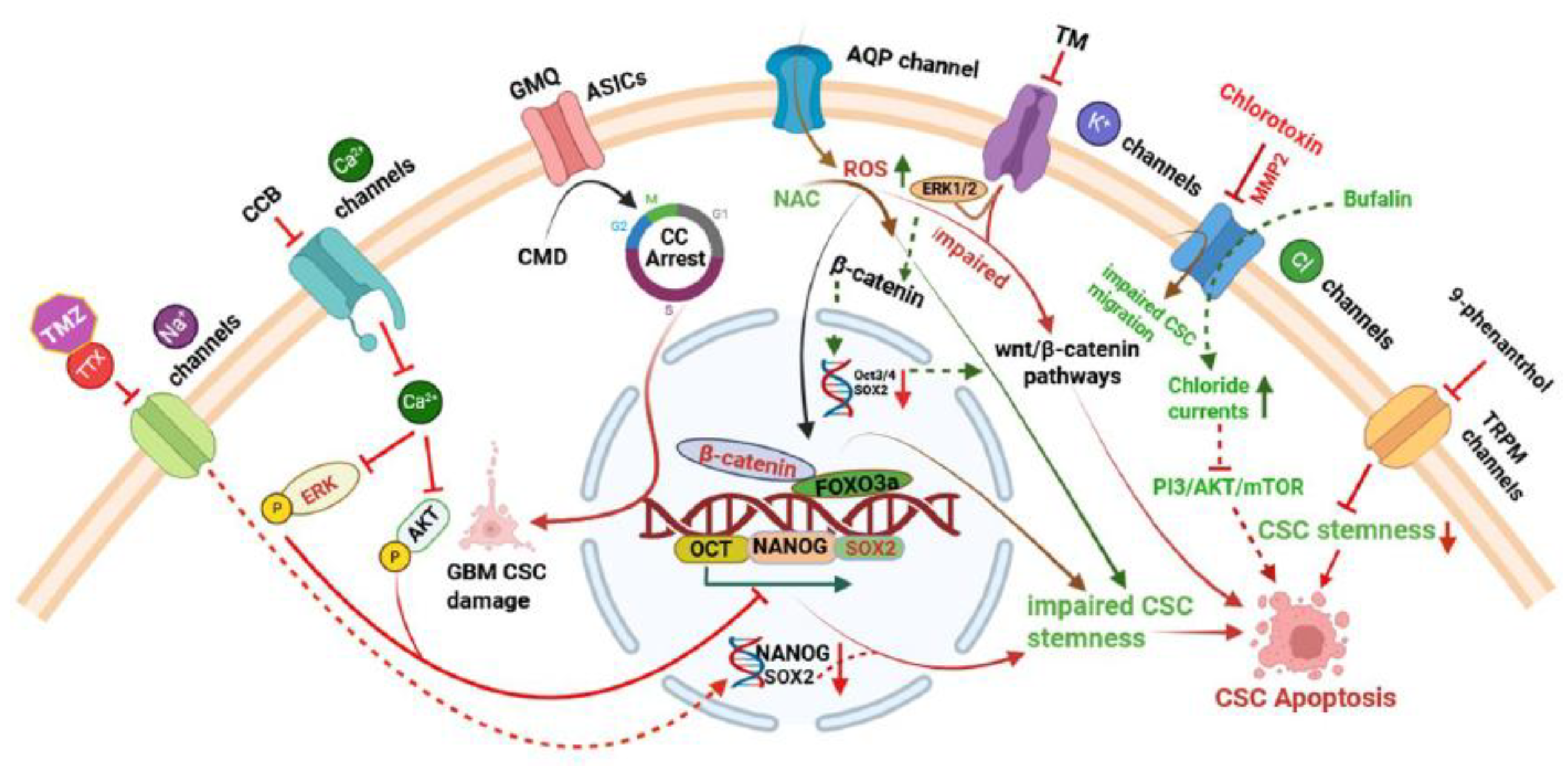

4.2. TRP Channels and Their Functions

4.3. VGCCs and Their Functions

4.4. Ca2+ Release Channels (CRCs)

5. Mechanosensitive Channels and Their Functions

6. Chloride Channels and Their Functions

7. Potassium (K⁺) Channels and Their Functions

8. Sodium (Na⁺) Channels and Their Functions

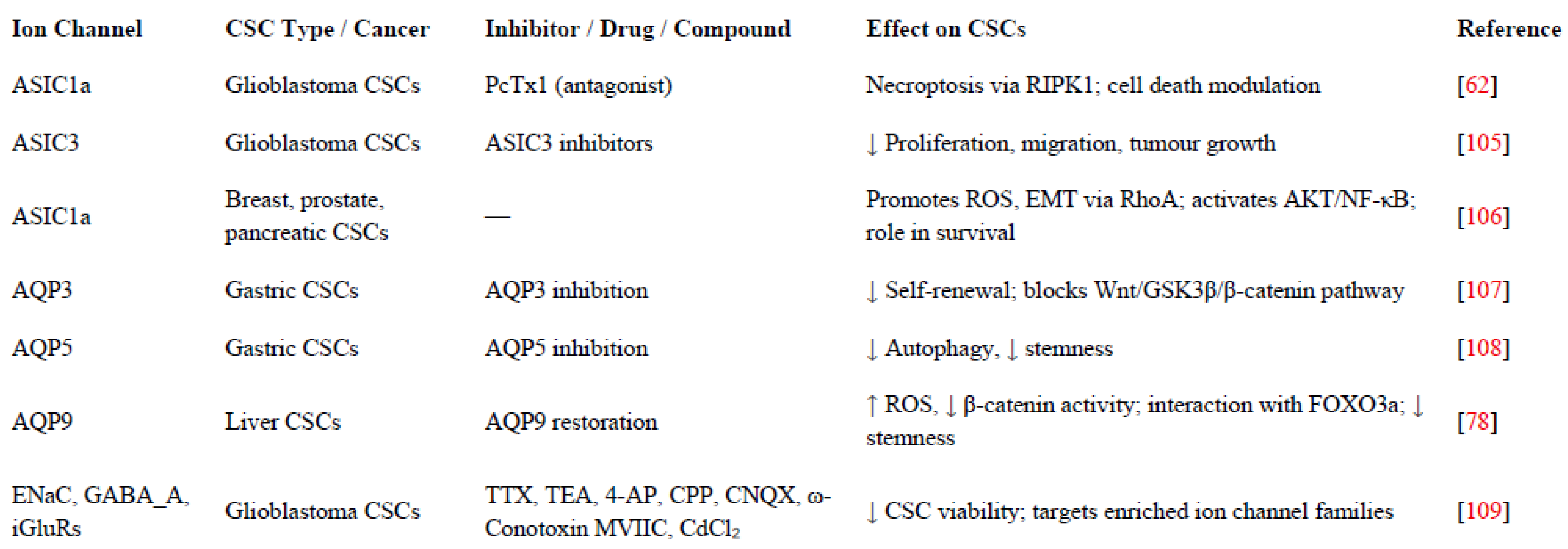

9. ASICs and Their Functions

10. AQPs or Water Channels and Their Functions

10.1. Intracellular Organelles Ion Channels and Their Functions

11. Interplay Between Ion Channels and Epigenetic Control in CSCs

12. Ion Channel-Targeted Therapies in CSCs

13. Challenges and Strategies in Ion Channel Research for CSCs

14. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

References

- Lobo NA, Shimono Y, Qian D, Clarke MF. The biology of cancer stem cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007; 23:675-99. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs E. The tortoise and the hair: slow-cycling cells in the stem cell race. Cell. 2009 May 29;137(5):811-9. [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly D, Buchanan P. Calcium channels and cancer stem cells. Cell Calcium. 2019 Jul; 81:21-28. [CrossRef]

- Chen K, Huang YH, Chen JL. Understanding and targeting cancer stem cells: therapeutic implications and challenges. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013 Jun;34(6):732-40. [CrossRef]

- Batlle E, Clevers H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med. 2017 Oct 6;23(10):1124-1134. [CrossRef]

- Clevers H. The cancer stem cell premises, promises and challenges. Nat Med. 2011 Mar;17(3):313-9. [CrossRef]

- Li GR, Deng XL. Functional ion channels in stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2011 Mar 26;3(3):19-24. [CrossRef]

- Jardin I, Lopez JJ, Sanchez-Collado J, Gomez LJ, Salido GM, Rosado JA. Store-operated Calcium entry and its implications in cancer stem cells. Cells. 2022 Apr 13;11(8):1332. [CrossRef]

- Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, CaceresCortes J, Minden M, Paterson B, Caligiuri MA and Dick JE: A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 367: 645-648, 1994.

- Bonnet D and Dick JE: Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med 3: 730-737, 1997.

- Cheng Q, Chen A, Du Q, Liao Q, Shuai Z, Chen C, Yang X, Hu Y, Zhao J, Liu S, Wen GR, An J, Jing H, Tuo B, Xie R, Xu J. Novel insights into ion channels in cancer stem cells (Review). Int J Oncol. 2018 Oct;53(4):1435-1441.

- Ertas YN, Abedi Dorcheh K, Akbari A, Jabbari E. Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery to Cancer Stem Cells: A Review of Recent Advances. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021 Jul 5;11(7):1755. [CrossRef]

- Dalerba P, Cho RW and Clarke MF: Cancer stem cells: models and concepts. Annu Rev Med 58: 267-284, 2007.

- Shiozawa Y, Nie B, Pienta KJ, Morgan TM and Taichman RS:Cancer stem cells and their role in metastasis. Pharmacol Ther 138: 285-293, 2013.

- Takebe N, Miele L, Harris PJ, Jeong W, Bando H, Kahn M, Yang SX, Ivy SP. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015 Aug;12(8):445-64. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Li M, Xu J, Cheng W. The modulation of ion channels in cancer chemo-resistance. Front Oncol. 2022 Aug 10; 12:945896. [CrossRef]

- Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y. Ion channels in cancer: Are cancer hallmarks oncochannelopathies? Physiol Rev (2018) 98(2):559–621. [CrossRef]

- Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y. Ion channels and the hallmarks of cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2010 Mar;16(3):107-21. [CrossRef]

- Lu CK, Reddy P, Wang D, Nie and Ning Y Multi-Label Clinical Time-Series generation via conditional GAN, in IEEE transactions on knowledge and data engineering. (2024) 36 (4):1728-1740. [CrossRef]

- Zhuo D, Lei Z, Dong L, Chan AML, Lin J, Jiang L, Qiu B, Jiang X, Tan Y, Yao X. Orai1 and Orai3 act through distinct signalling axes to promote stemness and tumorigenicity of breast cancer stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024; 13;15(1):256. [CrossRef]

- Lewuillon C, Guillemette A, Titah S, Shaik FA, Jouy N, Labiad O, Farfariello V, Laguillaumie MO, Idziorek T, Barthélémy A, Peyrouze P, Berthon C, Tarhan MC, Cheok M, Quesnel B, Lemonnier L, Touil Y. Involvement of ORAI1/SOCE in human AML cell lines and primary cells according to ABCB1 Activity, LSC Compartment and Potential Resistance to Ara-C Exposure. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 May 16;23(10):5555. [CrossRef]

- Jardin I, Alvarado S, Jimenez-Velarde V, Nieto-Felipe J, Lopez JJ, Salido GM, Smani T, Rosado JA. Orai1α and Orai1β support calcium entry and mammosphere formation in breast cancer stem cells. Sci Rep. 2023 Nov 9;13(1):19471. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen A, Sung Y, Lee SH, Martin CE, Srikanth S, Chen W, Kang MK, Kim RH, Park NH, Gwack Y, Kim Y, Shin KH. Orai3 Calcium channel contributes to oral/oropharyngeal cancer stemness through the elevation of ID1 expression. Cells. 2023 Sep 7;12(18):2225. [CrossRef]

- Terrié E, Déliot N, Benzidane Y, Harnois T, Cousin L, Bois P, Oliver L, Arnault P, Vallette F, Constantin B, Coronas V. Store-operated Calcium channels control proliferation and self-renewal of cancer stem cells from glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Jul 8;13(14):3428. [CrossRef]

- Shiozaki A, Kurashima K, Kudou M, Shimizu H, Kosuga T, Takemoto K, Arita T, Konishi H, Yamamoto Y, Morimura R, Komatsu S, Ikoma H, Kubota T, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Cancer stem cells of hepatocellular carcinoma are suppressed by the voltage-gated Calcium channel inhibitor Amlodipine. Anticancer Res. 2023 Nov;43(11):4855-4864. [CrossRef]

- Guo J, Shan C, Xu J, Li M, Zhao J, Cheng W. New Insights into TRP Ion Channels in Stem Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jul 14;23(14):7766. [CrossRef]

- Santoni G, Nabissi M, Amantini C, Santoni M, Ricci-Vitiani L, Pallini R, Maggi F, Morelli MB. ERK phosphorylation regulates the Aml1/Runx1 splice variants and the TRP channels expression during the differentiation of glioma stem cell lines. Cells. 2021 Aug 10;10(8):2052. [CrossRef]

- Zhang N, Wu P, Mu M, Niu C, Hu S. Exosomal circZNF800 derived from glioma stem-like cells regulates glioblastoma tumorigenicity via the PIEZO1/Akt Axis. Mol Neurobiol. 2024 Sep;61(9):6556-6571. [CrossRef]

- Lebon D, Collet L, Djordjevic S, Gomila C, Ouled-Haddou H, Platon J, Demont Y, Marolleau JP, Caulier A, Garçon L. PIEZO1 is essential for the survival and proliferation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cancer Med. 2024 Jan;13(2): e6984. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Wang D, Li H, Lei X, Liao W, Liu XY. Identification of Piezo1 as a potential target for therapy of colon cancer stem-like cells. Discov Oncol. 2023 Jun 12;14(1):95. [CrossRef]

- Kar P, Nelson C, Parekh AB. Selective activation of the transcription factor NFAT1 by calcium microdomains near Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels. J Biol Chem. 2011 Apr 29;286(17):14795-803. [CrossRef]

- Samanta K, Kar P, Mirams GR, Parekh AB. Cachannel re-localization to plasma-membrane microdomains strengthens activation of Ca2+-dependent nuclear gene expression. Cell Rep. 2015 Jul 14;12(2):203-16. [CrossRef]

- Luanpitpong S, Rodboon N, Samart P, Vinayanuwattikun C, Klamkhlai S, Chanvorachote P, Rojanasakul Y, Issaragrisil S. A novel TRPM7/O-GlcNAc axis mediates tumour cell motility and metastasis by stabilising c-Myc and caveolin-1 in lung carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2020 Oct;123(8):1289-1301. [CrossRef]

- Liu K, Xu SH, Chen Z, Zeng QX, Li ZJ, Chen ZM. TRPM7 overexpression enhances the cancer stem cell-like and metastatic phenotypes of lung cancer through modulation of the Hsp90α/uPA/MMP2 signaling pathway. BMC Cancer. 2018 Nov 26;18(1):1167. [CrossRef]

- Xue C, Gao Y, Li X, Zhang M, Yang Y, Han Q, Sun Z, Bai C, Zhao RC. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose accelerate the progression of colon cancer by inducing a MT-CAFs phenotype via TRPC3/NF-KB axis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022 Jul 23;13(1):335. [CrossRef]

- So CL, Milevskiy MJG, Monteith GR. Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V and breast cancer. Lab Invest. 2020 Feb;100(2):199-206. [CrossRef]

- Che X, Zhan J, Zhao F, Zhong Z, Chen M, Han R, Wang Y. Oridonin Promotes Apoptosis and Restrains the Viability and Migration of Bladder Cancer by Impeding TRPM7 Expression via the ERK and AKT Signaling Pathways. Biomed Res Int. 2021 Jul 5; 2021:4340950. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Inoue K, Leng T, Guo S, Xiong ZG. TRPM7 channels regulate glioma stem cell through STAT3 and Notch signaling pathways. Cell Signal. 2014 Dec;26(12):2773-81. [CrossRef]

- Middelbeek J, Visser D, Henneman L, Kamermans A, Kuipers AJ, Hoogerbrugge PM, Jalink K, van Leeuwen FN. TRPM7 maintains progenitor-like features of neuroblastoma cells: implications for metastasis formation. Oncotarget. 2015 Apr 20;6(11):8760-76. [CrossRef]

- Chen TM, Huang CM, Hsieh MS, Lin CS, Lee WH, Yeh CT, Liu SC. TRPM7 via calcineurin/NFAT pathway mediates metastasis and chemotherapeutic resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 2022 Jun 29;14(12):5250-5270. [CrossRef]

- Wee S, Niklasson M, Marinescu VD, Segerman A, Schmidt L, Hermansson A, Dirks P, Forsberg-Nilsson K, Westermark B, Uhrbom L, Linnarsson S, Nelander S, Andäng M. Selective calcium sensitivity in immature glioma cancer stem cells. PLoS One. 2014 Dec 22;9(12): e115698. [CrossRef]

- Shiozaki A, Katsurahara K, Kudou M, Shimizu H, Kosuga T, Ito H, Arita T, Konishi H, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Otsuji E. Amlodipine and Verapamil, voltage-gated Ca2+ channel inhibitors, suppressed the growth of gastric cancer stem cells. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021 Sep;28(9):5400-5411. [CrossRef]

- Lee H, Kwon OB, Lee JE, Jeon YH, Lee DS, Min SH, Kim JW. Repositioning trimebutine maleate as a cancer treatment targeting ovarian cancer stem cells. Cells. 2021 Apr 16;10(4):918. [CrossRef]

- Yao M, Tijore A, Cheng D, Li JV, Hariharan A, Martinac B, Tran Van Nhieu G, Cox CD, Sheetz M. Force- and cell state-dependent recruitment of Piezo1 drives focal adhesion dynamics and calcium entry. Sci Adv. 2022 Nov 11;8(45): eabo1461. [CrossRef]

- So CL, Robitaille M, Sadras F, McCullough MH, Milevskiy MJG, Goodhill GJ, Roberts-Thomson SJ, Monteith GR. Cellular geometry and epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity intersect with PIEZO1 in breast cancer cells. Commun Biol. 2024 Apr 17;7(1):467. [CrossRef]

- Kim HJ, Lee PC, Hong JH. Chloride channels and transporters: roles beyond classical cellular homeostatic pH or ion balance in cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Feb 9;14(4):856. [CrossRef]

- Yan Y, Ding X, Han C, Gao J, Liu Z, Liu Y, Wang K. Involvement of TMEM16A/ANO1 upregulation in the oncogenesis of colorectal cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2022 Jun 1;1868(6):166370. [CrossRef]

- Olsen ML, Schade S, Lyons SA, Amaral MD, Sontheimer H. Expression of voltage-gated chloride channels in human glioma cells. J Neurosci. 2003 Jul 2;23(13):5572-82. [CrossRef]

- Zhou FM, Huang YY, Tian T, Li XY, Tang YB. Knockdown of Chloride channel-3 inhibits breast cancer growth In Vitro and In Vivo. J Breast Cancer. 2018 Jun;21(2):103-111. [CrossRef]

- Peretti M, Raciti FM, Carlini V, Verduci I, Sertic S, Barozzi S, Garré M, Pattarozzi A, Daga A, Barbieri F, Costa A, Florio T, Mazzanti M. Mutual influence of ROS, pH, and CLIC1 membrane protein in the regulation of G1-S phase progression in human glioblastoma stem cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018 Nov;17(11):2451-2461. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri F, Bosio AG, Pattarozzi A, Tonelli M, Bajetto A, Verduci I, Cianci F, Cannavale G, Palloni LMG, Francesconi V, Thellung S, Fiaschi P, Mazzetti S, Schenone S, Balboni B, Girotto S, Malatesta P, Daga A, Zona G, Mazzanti M, Florio T. Chloride intracellular channel 1 activity is not required for glioblastoma development but its inhibition dictates glioma stem cell responsivity to novel biguanide derivatives. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022 Feb 8;41(1):53. [CrossRef]

- Setti M, Savalli N, Osti D, Richichi C, Angelini M, Brescia P, Fornasari L, Carro MS, Mazzanti M, Pelicci G. Functional role of CLIC1 ion channel in glioblastoma-derived stem/progenitor cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013 Nov 6;105(21):1644-55. [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga L, Cayo A, González W, Vilos C, Zúñiga R. Potassium Channels as a Target for Cancer Therapy: Current Perspectives. Onco Targets Ther. 2022 Jul 20; 15:783-797. [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri P, Mangino G, Fioretti B, Catacuzzeno L, Puca R, Ponti D, Miscusi M, Franciolini F, Ragona G, Calogero A. The inhibition of KCa3.1 channels activity reduces cell motility in glioblastoma derived cancer stem cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47825. [CrossRef]

- Lallet-Daher H, Roudbaraki M, Bavencoffe A, Mariot P, Gackière F, Bidaux G, Urbain R, Gosset P, Delcourt P, Fleurisse L, Slomianny C, Dewailly E, Mauroy B, Bonnal JL, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (IKCa1) regulate human prostate cancer cell proliferation through a close control of calcium entry. Oncogene. 2009 Apr 16;28(15):1792-806. [CrossRef]

- Guerriero C, Fanfarillo R, Mancini P, Sterbini V, Guarguaglini G, Sforna L, Michelucci A, Catacuzzeno L, Tata AM. M2 muscarinic receptors negatively modulate cell migration in human glioblastoma cells. Neurochem Int. 2024 Mar; 174:105673. [CrossRef]

- Shiozaki A, Konishi T, Kosuga T, Kudou M, Kurashima K, Inoue H, Shoda K, Arita T, Konishi H, Morimura R, Komatsu S, Ikoma H, Toma A, Kubota T, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Otsuji E. Roles of voltage-gated potassium channels in the maintenance of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Int J Oncol. 2021 Oct;59(4):76. [CrossRef]

- Lastraioli E. Focus on triple-negative breast cancer: Potassium channel expression and clinical correlates. Front Pharmacol. 2020 May 20; 11:725. [CrossRef]

- Bian Y, Tuo J, He L, Li W, Li S, Chu H, Zhao Y. Voltage-gated sodium channels in cancer and their specific inhibitors. Pathol Res Pract. 2023 Nov; 251:154909. [CrossRef]

- Giammello F, Biella C, Priori EC, Filippo MADS, Leone R, D’Ambrosio F, Paterno’ M, Cassioli G, Minetti A, Macchi F, Spalletti C, Morella I, Ruberti C, Tremonti B, Barbieri F, Lombardi G, Brambilla R, Florio T, Galli R, Rossi P, Brandalise F. Modulating voltage-gated sodium channels to enhance differentiation and sensitize glioblastoma cells to chemotherapy. Cell Commun Signal. 2024 Sep 9;22(1):434. [CrossRef]

- Djamgoz MBA. Stemness of Cancer: A study of triple-negative breast cancer from a neuroscience perspective. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2025 Feb;21(2):337-350. [CrossRef]

- Tian Y, Bresenitz P, Reska A, El Moussaoui L, Beier CP, Gründer S. Glioblastoma cancer stem cell lines express functional acid sensing ion channels ASIC1a and ASIC3. Sci Rep. 2017 Oct 20;7(1):13674. [CrossRef]

- Clusmann J, Franco KC, Suárez DAC, Katona I, Minguez MG, Boersch N, Pissas KP, Vanek J, Tian Y, Gründer S. Acidosis induces RIPK1-dependent death of glioblastoma stem cells via acid-sensing ion channel 1a. Cell Death Dis. 2022 Aug 12;13(8):702. [CrossRef]

- King P, Wan J, Guo AA, Guo S, Jiang Y, Liu M. Regulation of gliomagenesis and stemness through acid sensor ASIC1a. Int J Oncol. 2021 Oct;59(4):82. [CrossRef]

- Guan Y, Han J, Chen D, Zhan Y, Chen J. Aquaporin 1 overexpression may enhance glioma tumorigenesis by interacting with the transcriptional regulation networks of Foxo4, Maz, and E2F families. Chin Neurosurg J. 2023 Dec 6;9(1):34. [CrossRef]

- Huang YT, Zhou J, Shi S, Xu HY, Qu F, Zhang D, Chen YD, Yang J, Huang HF, Sheng JZ. Identification of estrogen response element in Aquaporin-3 gene that mediates estrogen-induced cell migration and invasion in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2015 Jul 29; 5:12484. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Wu G, Fu X, Xu S, Wang T, Zhang Q, Yang Y. Aquaporin 3 maintains the stemness of CD133+ hepatocellular carcinoma cells by activating STAT3. Cell Death Dis. 2019 Jun 13;10(6):465. [CrossRef]

- Liu YC, Yeh CT, Lin KH. Cancer stem cell functions in hepatocellular carcinoma and comprehensive therapeutic strategies. Cells. 2020 May 26;9(6):1331. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Liu L, Zhang Y, Jing H. Molecular mechanism of AQP3 in regulating differentiation and apoptosis of lung cancer stem cells through Wnt/GSK-3β/β-Catenin pathway. J BUON. 2020 Jul-Aug;25(4):1714-1720.

- Simone L, Pisani F, Binda E, Frigeri A, Vescovi AL, Svelto M, Nicchia GP. AQP4-dependent glioma cell features affect the phenotype of surrounding cells via extracellular vesicles. Cell Biosci. 2022 Sep 7;12(1):150. [CrossRef]

- Jang SJ, Moon C. Aquaporin 5 (AQP5) expression in breast cancer and its clinicopathological characteristics. PLoS One. 2023 Jan 27;18(1): e0270752. [CrossRef]

- Zhao R, He B, Bie Q, Cao J, Lu H, Zhang Z, Liang J, Wei L, Xiong H, Zhang B. AQP5 complements LGR5 to determine the fates of gastric cancer stem cells through regulating ULK1 ubiquitination. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022 Nov 14;41(1):322. Erratum in: J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022 Dec 13;41(1):342. doi: 10.1186/s13046-022-02557-1. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Song Y, Pan C, Yu J, Zhang J, Zhu X. Aquaporin-8 is a novel marker for progression of human cervical cancer cells. Cancer Biomark. 2021;32(3):391-400. [CrossRef]

- Zheng X, Li C, Yu K, Shi S, Chen H, Qian Y, Mei Z. Aquaporin-9, mediated by IGF2, suppresses liver cancer stem cell properties via augmenting ROS/β-Catenin/FOXO3a signaling. Mol Cancer Res. 2020 Jul;18(7):992-1003. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Garcia E, Paudel U, Noji MC, Bowman CE, Rustgi AK, Pitarresi JR, Wellen KE, Arany Z, Weissenrieder JS, Foskett JK. The mitochondrial Ca2+ channel MCU is critical for tumor growth by supporting cell cycle progression and proliferation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023 Jun 8; 11:1082213. [CrossRef]

- Tang S, Wang X, Shen Q, Yang X, Yu C, Cai C, Cai G, Meng X, Zou F. Mitochondrial Ca²⁺ uniporter is critical for store-operated Ca²⁺ entry-dependent breast cancer cell migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015 Feb 27;458(1):186-93. [CrossRef]

- Bong AHL, Robitaille M, Lin S, McCart-Reed A, Milevskiy M, Angers S, Roberts-Thomson SJ, Monteith GR. TMCO1 is upregulated in breast cancer and regulates the response to pro-apoptotic agents in breast cancer cells. Cell Death Discov. 2024 Oct 1;10(1):421. [CrossRef]

- Shen FF, Dai SY, Wong NK, Deng S, Wong AS, Yang D. Mediating K+/H+ transport on organelle membranes to selectively eradicate cancer stem cells with a small molecule. J Am Chem Soc. 2020 Jun 17;142(24):10769-10779. [CrossRef]

- Zheng J, Feng Y, Yuan C. Hsa_circ_0007905 as a modulator of miR-330-5p and VDAC1: Enhancing stemness and reducing apoptosis in cervical cancer stem cells. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2025 May;44(3):213-226. [CrossRef]

- Seoane J. Cancer: Division hierarchy leads to cell heterogeneity. Nature. 2017 Sep 14;549(7671):164-166. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien-Ball C, Biddle A. Reprogramming to developmental plasticity in cancer stem cells. Dev Biol. 2017 Oct 15;430(2):266-274. [CrossRef]

- Sun XX, Yu Q. Intra-tumor heterogeneity of cancer cells and its implications for cancer treatment. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015 Oct;36(10):1219-27. [CrossRef]

- Marusyk A, Polyak K. Tumor heterogeneity: causes and consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Jan;1805(1):105-17. [CrossRef]

- Kang Q, Peng X, Li X, Hu D, Wen G, Wei Z, Yuan B. Calcium Channel Protein ORAI1 Mediates TGF-β Induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Front Oncol. 2021 May 12; 11:649476. [CrossRef]

- Beck B, Lapouge G, Rorive S, Drogat B, Desaedelaere K, Delafaille S, Dubois C, Salmon I, Willekens K, Marine JC, Blanpain C. Different levels of Twist1 regulate skin tumor initiation, stemness, and progression. Cell Stem Cell. 2015 Jan 8;16(1):67-79. [CrossRef]

- He T, Wang C, Zhang M, Zhang X, Zheng S, Linghu E, Guo M. Epigenetic regulation of voltage-gated potassium ion channel molecule Kv1.3 in mechanisms of colorectal cancer. Discov Med. 2017 Mar;23(126):155-162.

- Herranz N, Pasini D, Díaz VM, Francí C, Gutierrez A, Dave N, Escrivà M, Hernandez-Muñoz I, Di Croce L, Helin K, García de Herreros A, Peiró S. Polycomb complex 2 is required for E-cadherin repression by the Snail1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 Aug;28(15):4772-81. [CrossRef]

- Luo M, Bao L, Xue Y, Zhu M, Kumar A, Xing C, Wang JE, Wang Y, Luo W. ZMYND8 protects breast cancer stem cells against oxidative stress and ferroptosis through activation of NRF2. J Clin Invest. 2024 Jan 23;134(6): e171166. [CrossRef]

- Bao L, Festa F, Freet CS, Lee JP, Hirschler-Laszkiewicz IM, Chen SJ, Keefer KA, Wang HG, Patterson AD, Cheung JY, Miller BA. The Human Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 Ion Channel Modulates ROS Through Nrf2. Sci Rep. 2019 Oct 1;9(1):14132. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D., Wu, R., Guo, Y. & Kong, A. N. regulation of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling: The role of epigenetics. Curr Opin Toxicol 1, 134–138, doi.org/10.1016/j.cotox.2016.10.008 (2016).

- Samanta K, Ahel I, Kar p; Deciphering of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced calpain activation in cancer progression and its therapeutic potential, Advances in Redox Research, 2025, 10024.

- K. Chen, P. Lu, N.M. Beeraka, O.A. Sukocheva, S.V. Madhunapantula, J. Liu, M. Y. Sinelnikov, V.N. Nikolenko, K.V. Bulygin, L.M. Mikhaleva, I.V. Reshetov, Y. Gu, J. Zhang, Y. Cao, S.G. Somasundaram, C.E. Kirkland, R. Fan, G. Aliev, Mitochondrial mutations and mitoepigenetics: focus on regulation of oxidative stress-induced responses in breast cancers, Semin. Cancer Biol. (2020) 30203–30210. S1044-579X.

- Arif T, Shteinfer-Kuzmine A, Shoshan-Barmatz V. Decoding cancer through silencing the mitochondrial gatekeeper VDAC1. Biomolecules. 2024 Oct 15;14(10):1304. [CrossRef]

- Shoshan-Barmatz V, Krelin Y, Shteinfer-Kuzmine A, Arif T. Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 as an emerging drug target for novel anti-cancer therapeutics. Front Oncol. 2017 Jul 31; 7:154. [CrossRef]

- Alnasser SM. Advances and Challenges in Cancer Stem Cells for Onco-Therapeutics. Stem Cells Int. 2023 Dec 6;2023:8722803. [CrossRef]

- Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F, Zdebik AA. Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels. Physiol Rev. 2002 Apr;82(2):503-68. [CrossRef]

- Lee H, Kim JW, Kim DK, Choi DK, Lee S, Yu JH, Kwon OB, Lee J, Lee DS, Kim JH, Min SH. Calcium channels as novel therapeutic targets for ovarian cancer stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Mar 27;21(7):2327. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Cruickshanks N, Yuan F, Wang B, Pahuski M, Wulfkuhle J, Gallagher I, Koeppel AF, Hatef S, Papanicolas C, Lee J, Bar EE, Schiff D, Turner SD, Petricoin EF, Gray LS, Abounader R. Targetable T-type Calcium Channels Drive Glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2017 Jul 1;77(13):3479-3490. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Zhao Y, Schwarz B, Mysliwietz J, Hartig R, Camaj P, Bao Q, Jauch KW, Guba M, Ellwart JW, Nelson PJ, Bruns CJ. Verapamil inhibits tumor progression of chemotherapy-resistant pancreatic cancer side population cells. Int J Oncol. 2016 Jul;49(1):99-110. [CrossRef]

- Fraser SP, Grimes JA, Djamgoz MB. Effects of voltage-gated ion channel modulators on rat prostatic cancer cell proliferation: comparison of strongly and weakly metastatic cell lines. Prostate. 2000 Jun 15;44(1):61-76. [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro G, Grimaldi A, Chece G, Porzia A, Esposito V, Santoro A, Salvati M, Mainiero F, Ragozzino D, Di Angelantonio S, Wulff H, Catalano M, Limatola C. KCa3.1 channel inhibition sensitizes malignant gliomas to temozolomide treatment. Oncotarget. 2016 May 24;7(21):30781-96. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Goel HL, Xiong C, Goel S, Kumar A, Li R, Zhu LJ, Clark JL, Brehm MA, Mercurio AM. The calcium channel TRPC6 promotes chemotherapy-induced persistence by regulating integrin α6 mRNA splicing. Cell Rep. 2023 Nov 28;42(11):113347. [CrossRef]

- Comes N, Bielanska J, Vallejo-Gracia A, Serrano-Albarrás A, Marruecos L, Gómez D, Soler C, Condom E, Ramón Y Cajal S, Hernández-Losa J, Ferreres JC, Felipe A. The voltage-dependent K (+) channels Kv1.3 and Kv1.5 in human cancer. Front Physiol. 2013 Oct 10; 4:283. [CrossRef]

- Kang MK, Kang SK. Pharmacologic blockade of chloride channel synergistically enhances apoptosis of chemotherapeutic drug-resistant cancer stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008 Sep 5;373(4):539-44. [CrossRef]

- Balboni A, D’Angelo C, Collura N, Brusco S, Di Berardino C, Targa A, Massoti B, Mastrangelo E, Milani M, Seneci P, Broccoli V, Muzio L, Galli R, Menegon A. Acid-sensing ion channel 3 is a new potential therapeutic target for the control of glioblastoma cancer stem cells growth. Sci Rep. 2024 Sep 3;14(1):20421. [CrossRef]

- Gründer S, Vanek J, Pissas KP. Acid-sensing ion channels and downstream signalling in cancer cells: is there a mechanistic link? Pflugers Arch. 2024 Apr;476(4):659-672. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Wang Y, Wen J, Zhao H, Dong X, Zhang Z, Wang S, Shen L. Aquaporin 3 promotes the stem-like properties of gastric cancer cells via Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin pathway. Oncotarget. 2016 Mar 29;7(13):16529-41. [CrossRef]

- Gao P, Chen A, Tian H, Wang F, Wang N, Ge K, Lian C, Wang F, Zhang Q. Investigating the mechanism and the effect of aquaporin 5 (AQP5) on the self-renewal capacity of gastric cancer stem cells. J Cancer. 2024 Jun 11;15(13):4313-4327. [CrossRef]

- Pollak J, Rai KG, Funk CC, Arora S, Lee E, Zhu J, Price ND, Paddison PJ, Ramirez JM, Rostomily RC. Ion channel expression patterns in glioblastoma stem cells with functional and therapeutic implications for malignancy. PLoS One. 2017 Mar 6;12(3): e0172884. [CrossRef]

- Shi Q, Yang Z, Yang H, Xu L, Xia J, Gu J, Chen M, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liao Z, Mou Y, Gu X, Xie T, Sui X. Targeting ion channels: innovative approaches to combat cancer drug resistance. Theranostics. 2025 Jan 1;15(2):521-545. [CrossRef]

- Zheng X, Yu C, Xu M. Linking Tumor Microenvironment to Plasticity of Cancer Stem Cells: Mechanisms and Application in Cancer Therapy. Front Oncol. 2021 Jun 28; 11:678333. [CrossRef]

- Tan KK, Giam CS, Leow MY, Chan CW, Yim EK. Differential cell adhesion of breast cancer stem cells on biomaterial substrate with nanotopographical cues. J Funct Biomater. 2015 Apr 21;6(2):241-58. [CrossRef]

- Marjanovic ND, Weinberg RA, Chaffer CL. Cell plasticity and heterogeneity in cancer. Clin Chem. 2013 Jan;59(1):168-79. [CrossRef]

- Rao VR, Perez-Neut M, Kaja S, Gentile S. Voltage-gated ion channels in cancer cell proliferation. Cancers (Basel). 2015 May 22;7(2):849-75. [CrossRef]

- Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015 Mar 5;16(3):225-38. [CrossRef]

- Dallas ML, Bell D. Advances in ion channel high throughput screening: where are we in 2023? Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2024 ;19(3):331-337. [CrossRef]

- Hjelmeland AB, Wu Q, Heddleston JM, Choudhary GS, MacSwords J, Lathia JD, McLendon R, Lindner D, Sloan A, Rich JN. Acidic stress promotes a glioma stem cell phenotype. Cell Death Differ. 2011 May;18(5):829-40. [CrossRef]

- Patel AP, Tirosh I, Trombetta JJ, Shalek AK, Gillespie SM, Wakimoto H, Cahill DP, Nahed BV, Curry WT, Martuza RL, Louis DN, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Suvà ML, Regev A, Bernstein BE. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science. 2014 Jun 20;344(6190):1396-401. [CrossRef]

- Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D, Schier AF, Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol. 2015 May;33(5):495-502. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Gustafson P, Huo D. Bayesian adjustment for the misclassification in both dependent and independent variables with application to a breast cancer study. Stat Med. 2016 Oct 15;35(23):4252-63. [CrossRef]

- Clevers H. Modeling Development and Disease with Organoids. Cell. 2016 Jun 16;165(7):1586-1597. [CrossRef]

- Sun J, MacKinnon R. Cryo-EM Structure of a KCNQ1/CaM Complex Reveals Insights into Congenital Long QT Syndrome. Cell. 2017 Jun 1;169(6):1042-1050.e9. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Camacho A, Flores-Vázquez JG, Moscardini-Martelli J, Torres-Ríos JA, Olmos-Guzmán A, Ortiz-Arce CS, Cid-Sánchez DR, Pérez SR, Macías-González MDS, Hernández-Sánchez LC, Heredia-Gutiérrez JC, Contreras-Palafox GA, Suárez-Campos JJE, Celis-López MÁ, Gutiérrez-Aceves GA, Moreno-Jiménez S. Glioblastoma Treatment: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jun 29;23(13):7207. [CrossRef]

- Gründer S, Vanek J, Pissas KP. Acid-sensing ion channels and downstream signalling in cancer cells: is there a mechanistic link? Pflugers Arch. 2024 Apr;476(4):659-672. [CrossRef]

- Lastraioli E, Iorio J, Arcangeli A. Ion channel expression as promising cancer biomarker. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1848(10 Pt B):2685-702. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee A, Jana A, Bhattacharjee S, Mitra S, De S, Alghamdi BS, Alam MZ, Mahmoud AB, Al Shareef Z, Abdel-Rahman WM, Woon-Khiong C, Alexiou A, Papadakis M, Ashraf GM. The role of Aquaporins in tumorigenesis: implications for therapeutic development. Cell Commun Signal. 2024; 9;22(1):106. [CrossRef]

- Lavoie H, Gagnon J, Therrien M. ERK signalling: a master regulator of cell behaviour, life and fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020; 21(10):607-632. [CrossRef]

- Bortner CD, Gomez-Angelats M, Cidlowski JA. Plasma membrane depolarization without repolarization is an early molecular event in anti-Fas-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001 Feb 9;276(6):4304-14. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).