Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

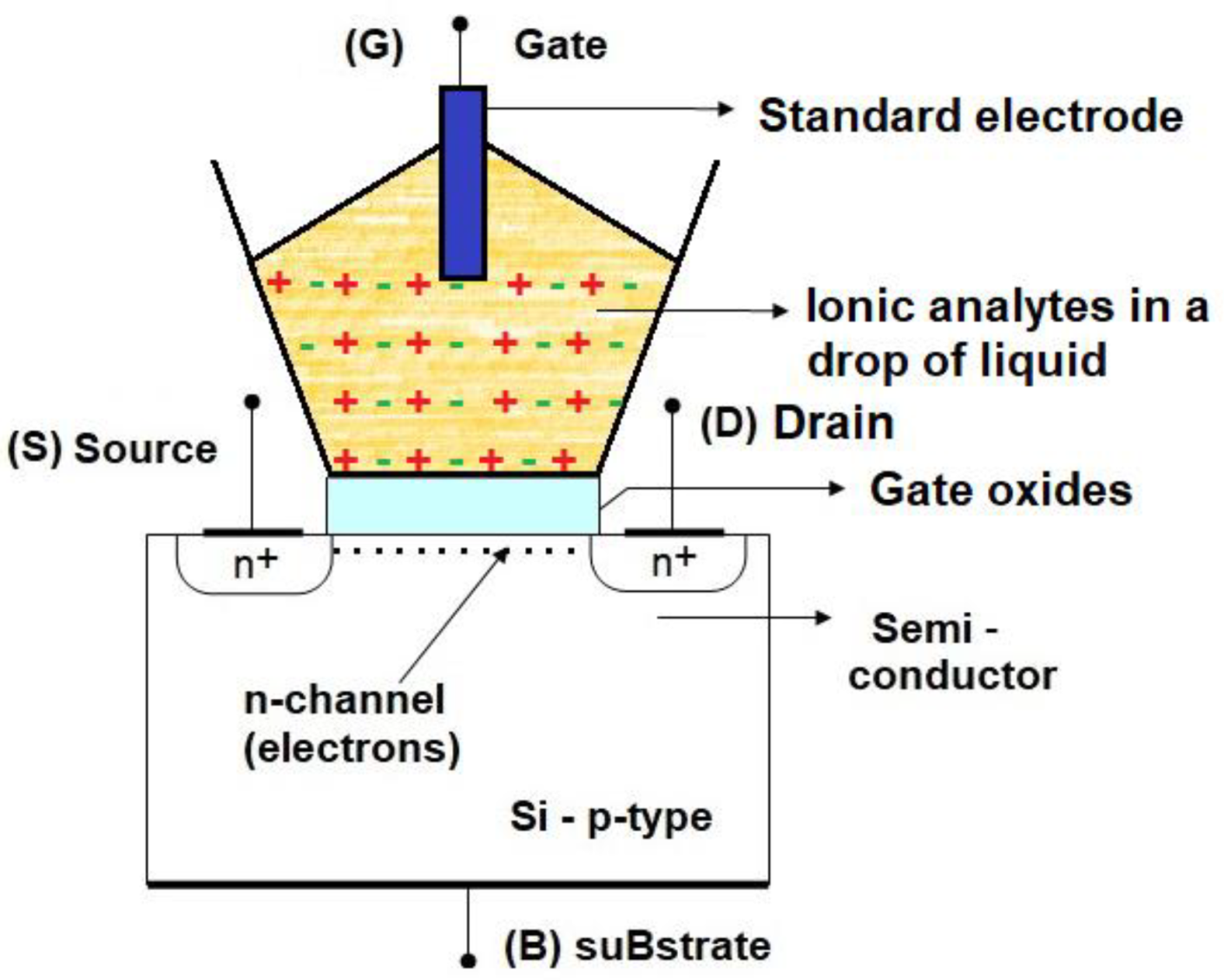

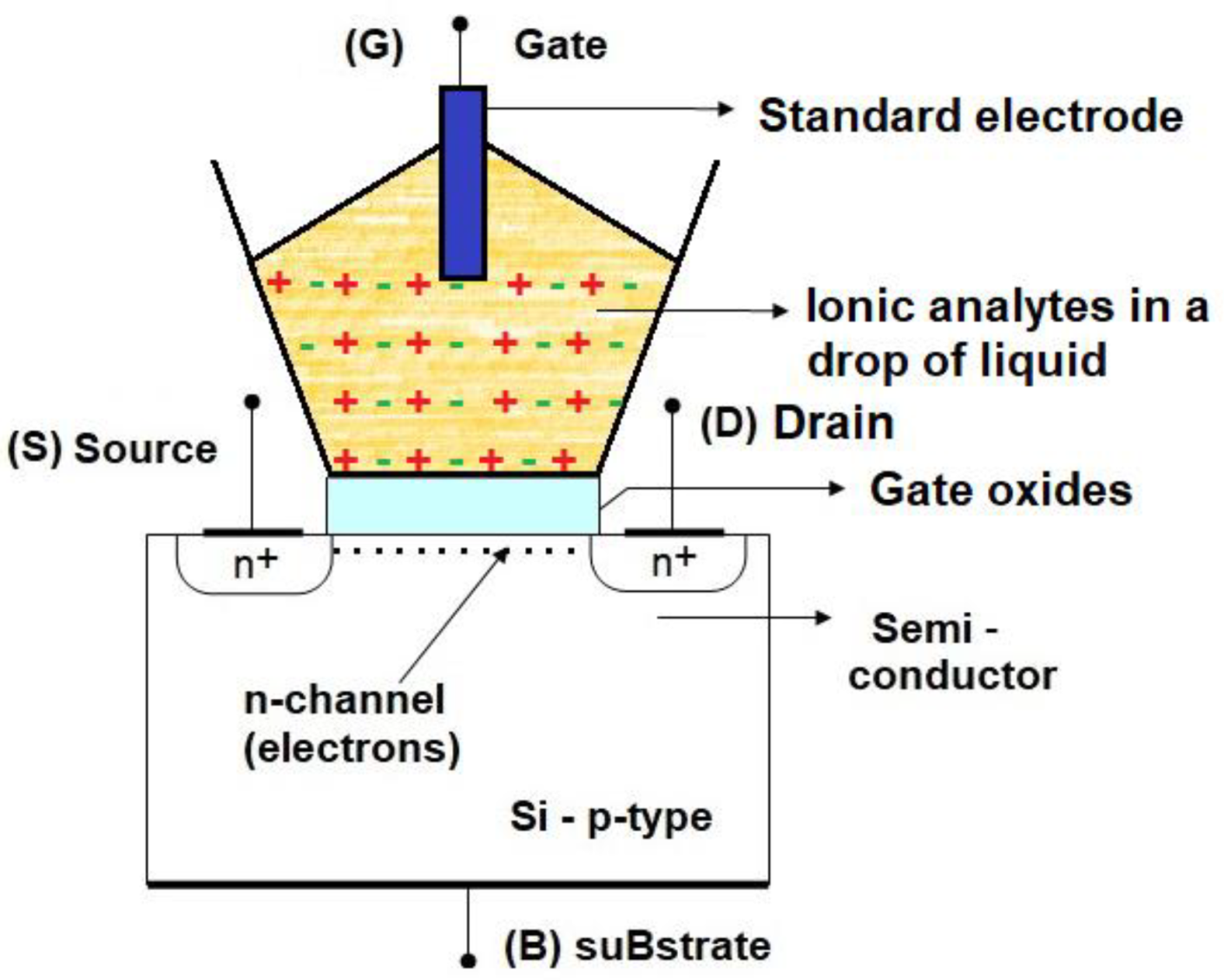

2. ISFET Work Principle and Technological Challenges

2.1. From ISFET Theory to Materials Motivation

2.2. ISFET Particular Technology

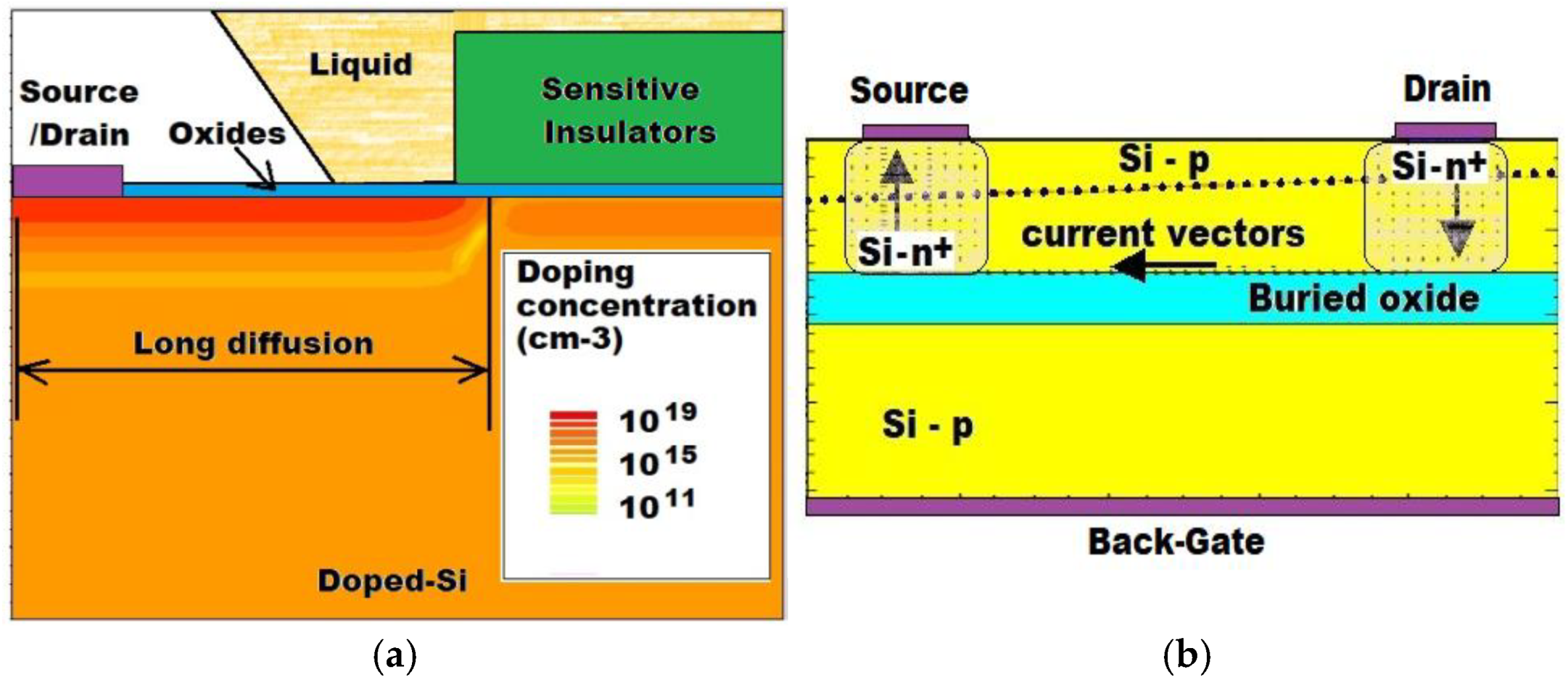

3. Nano-Structured Oxides Used for Sensitive Layer Integration

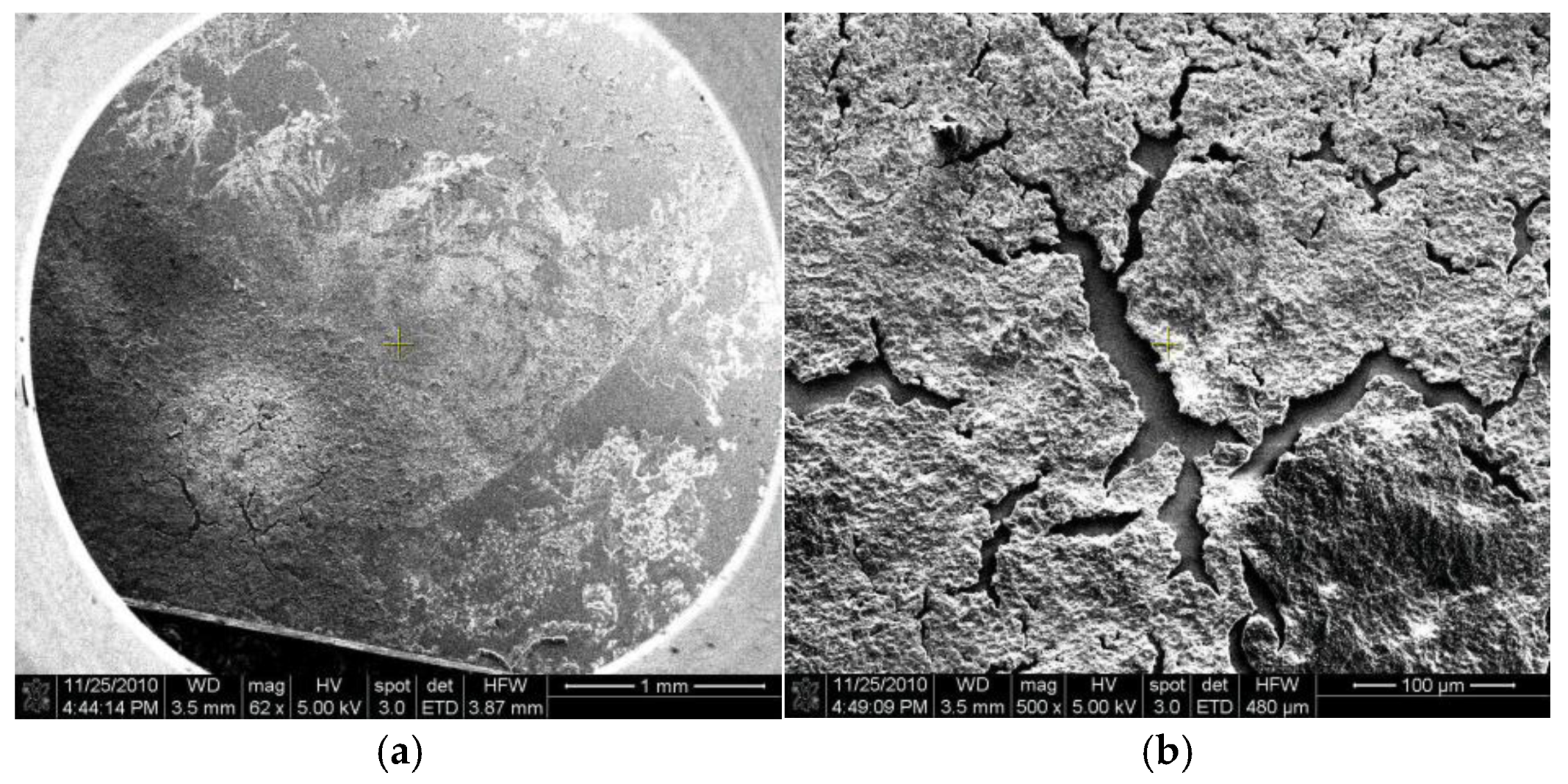

3.1. Porous Si on Si-Wafer

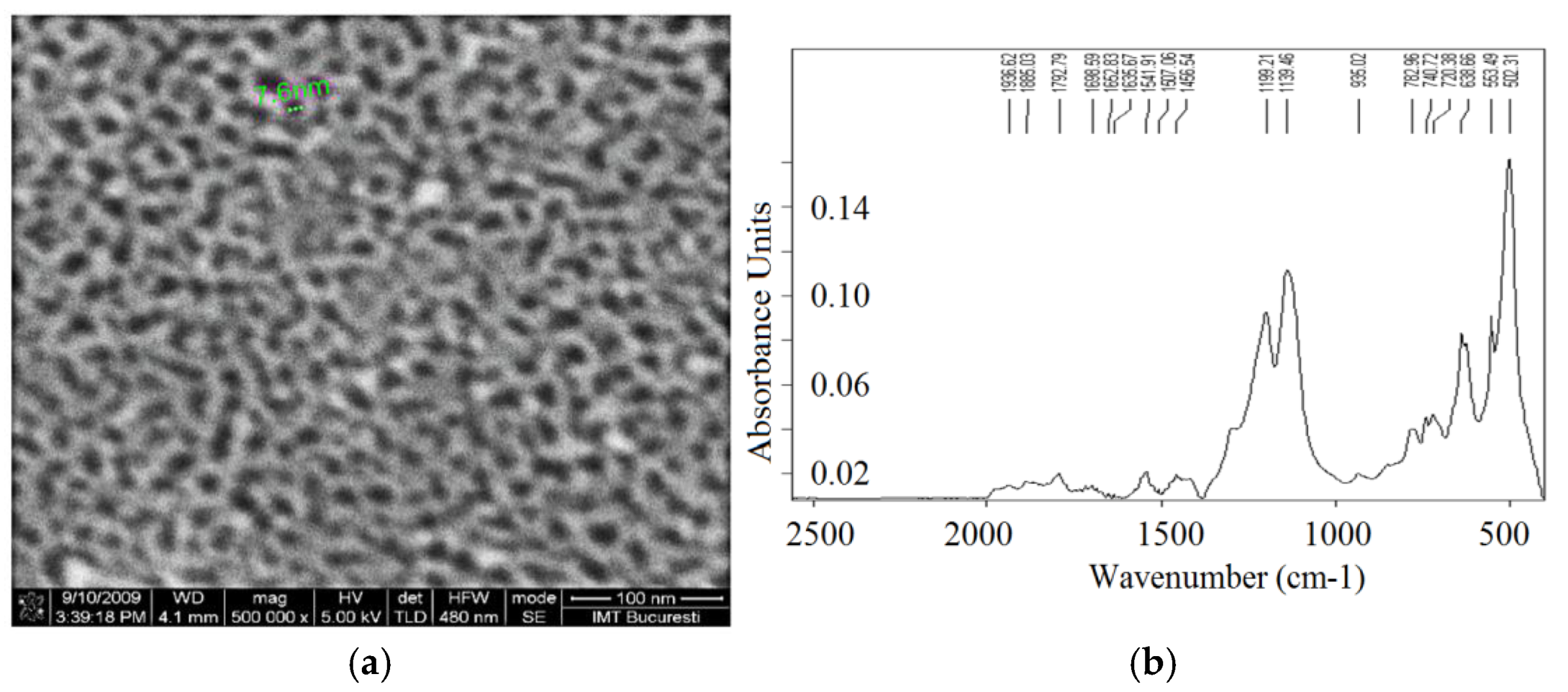

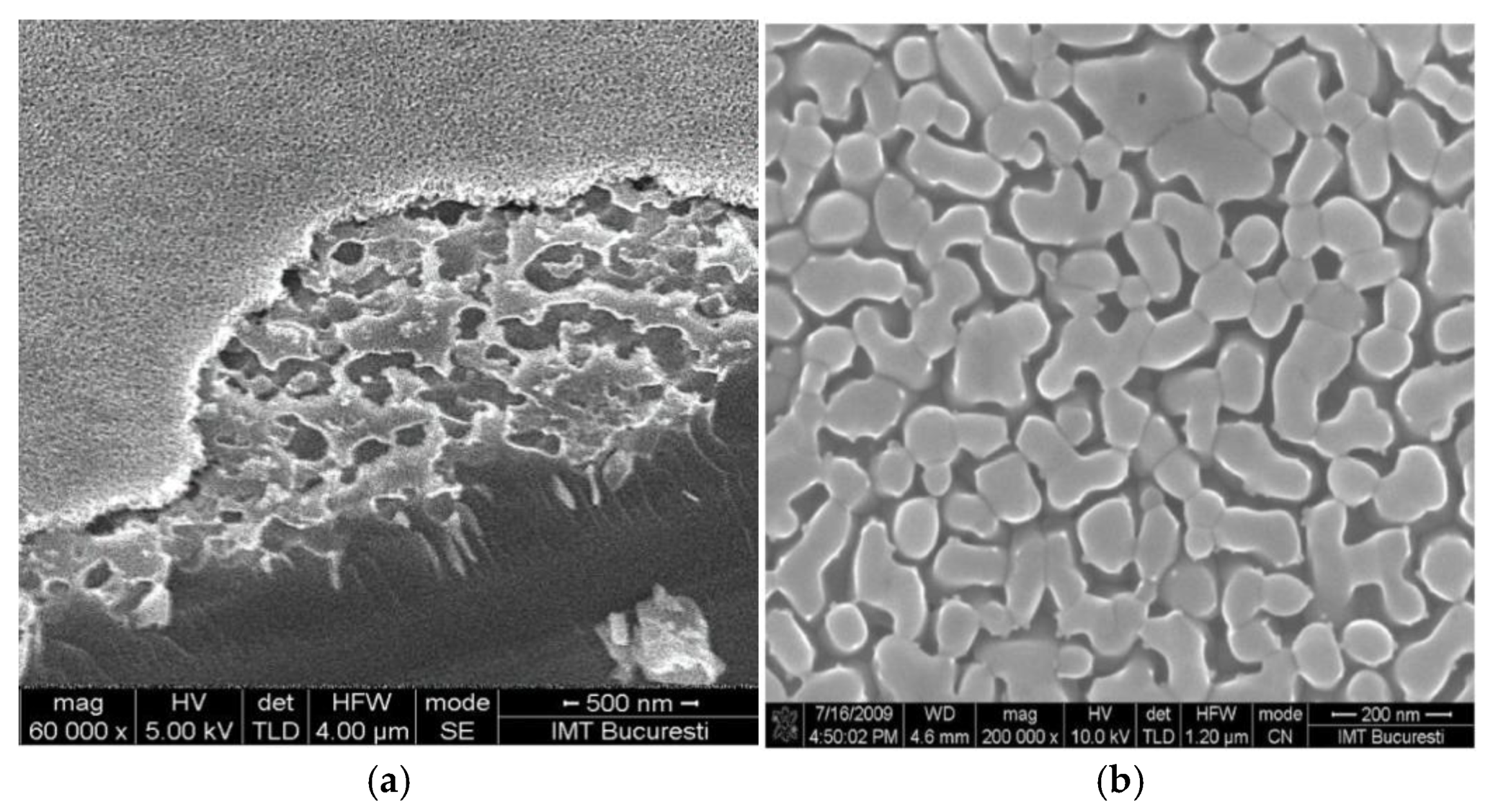

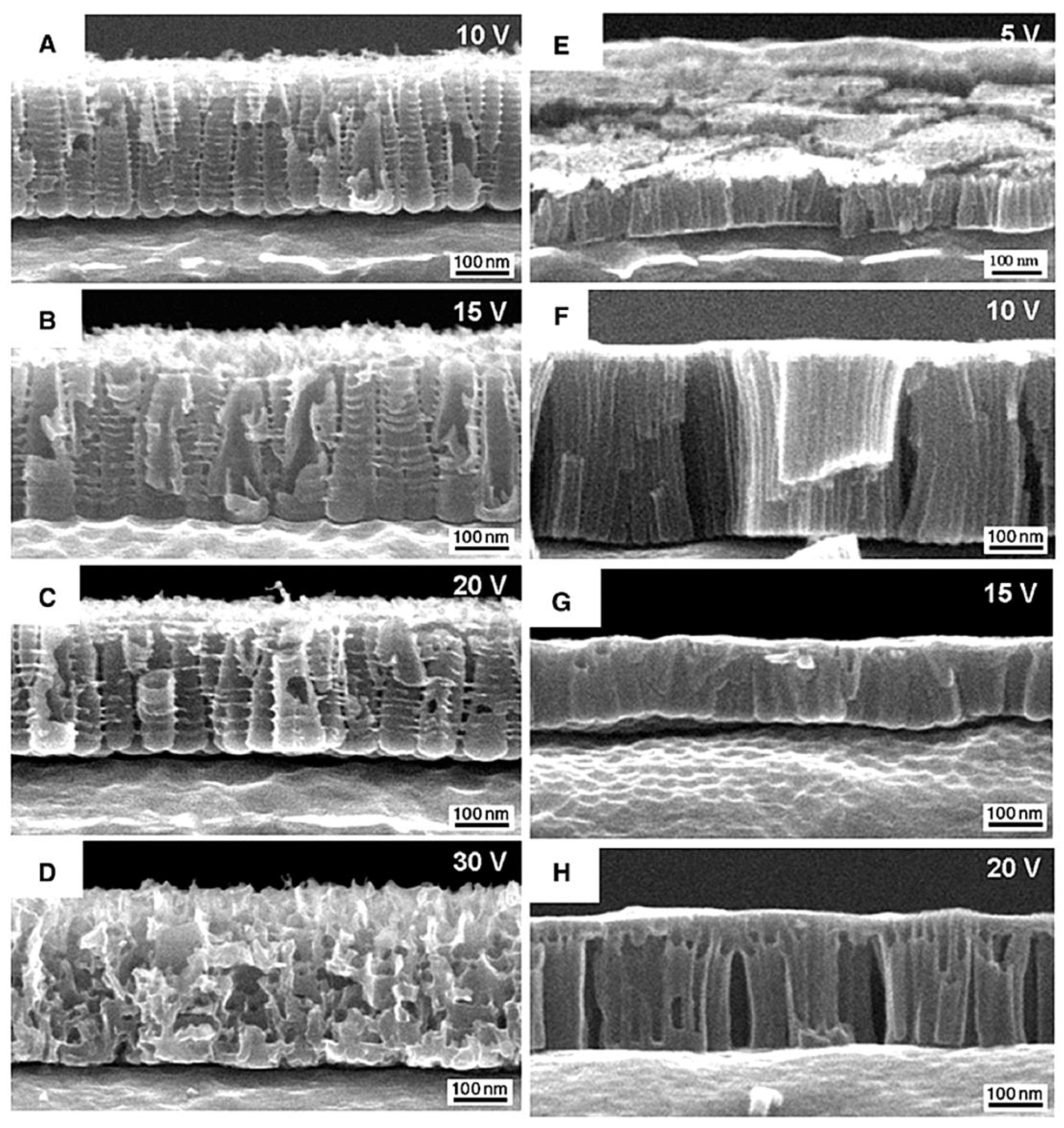

3.2. Porous Al2O3 on Si-Wafer

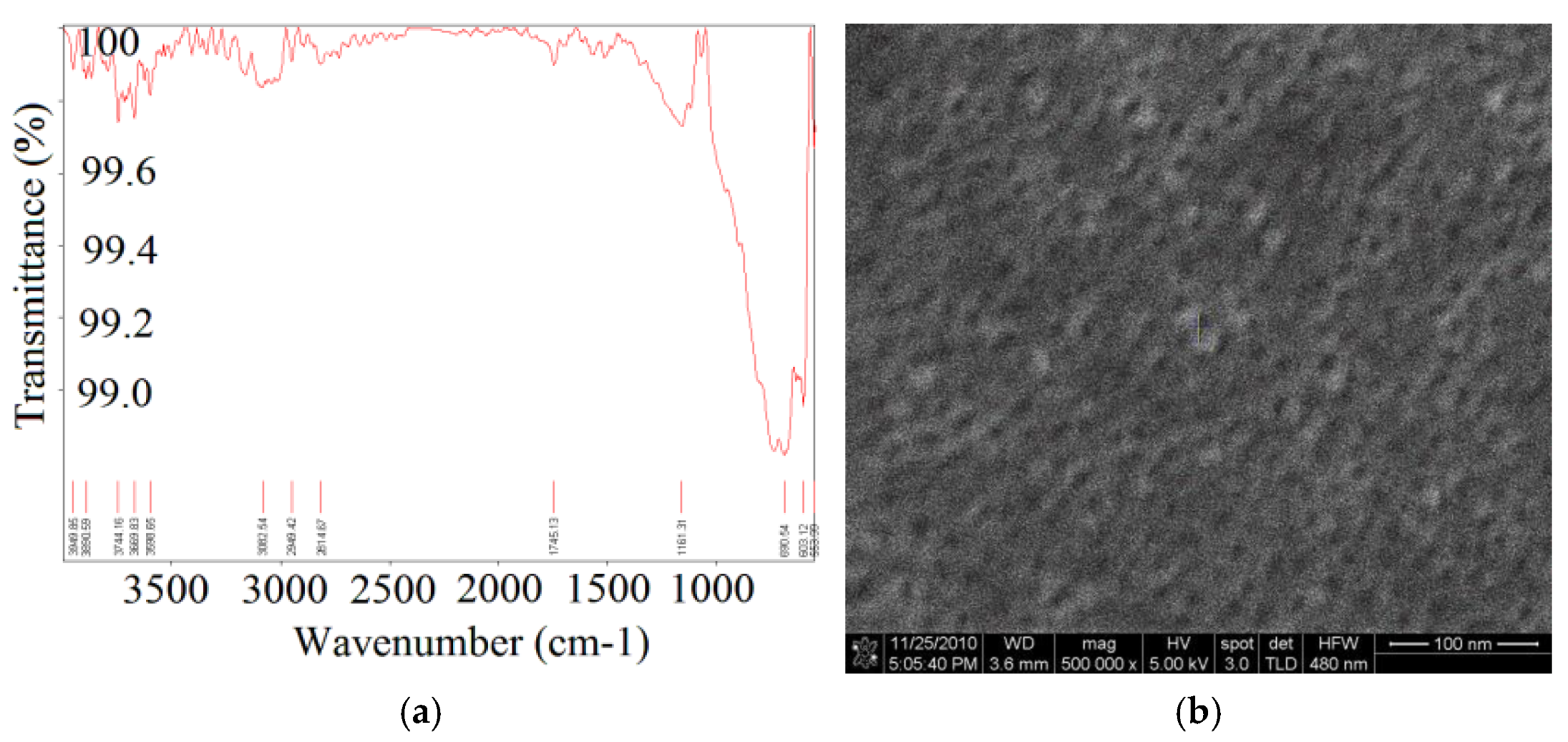

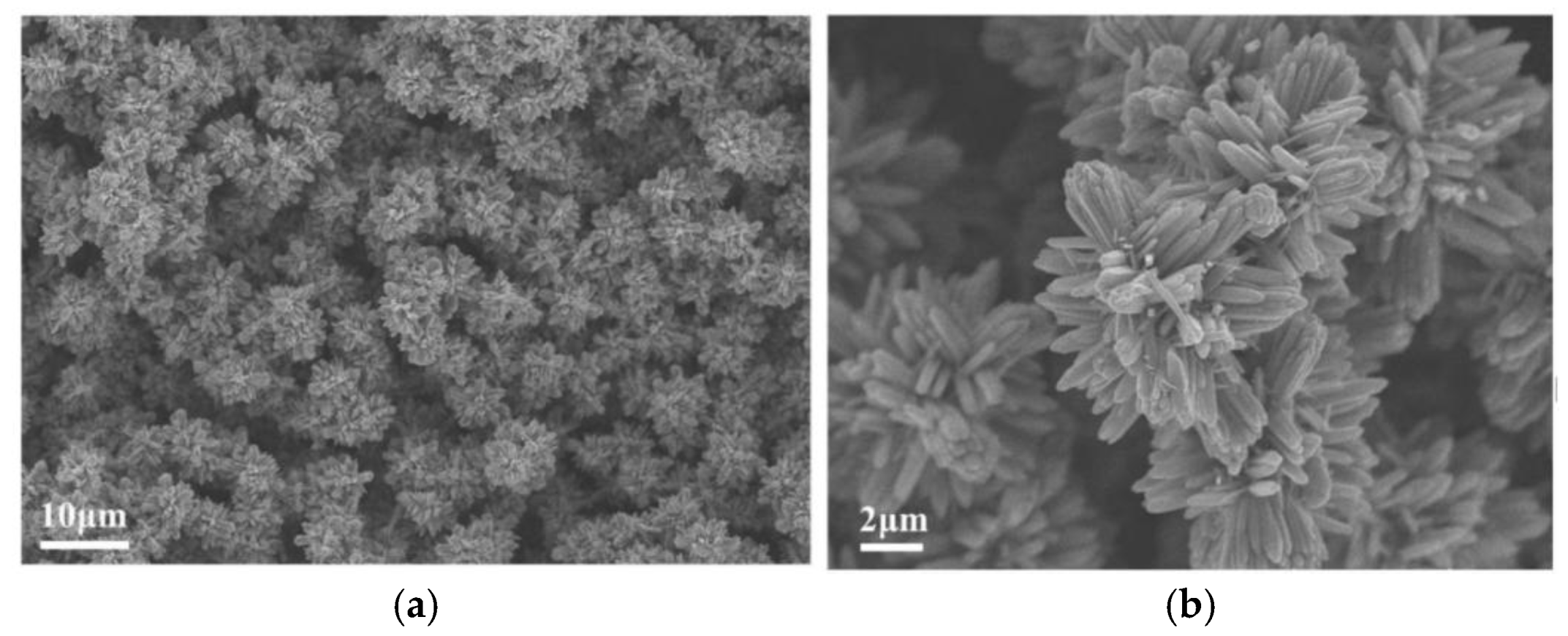

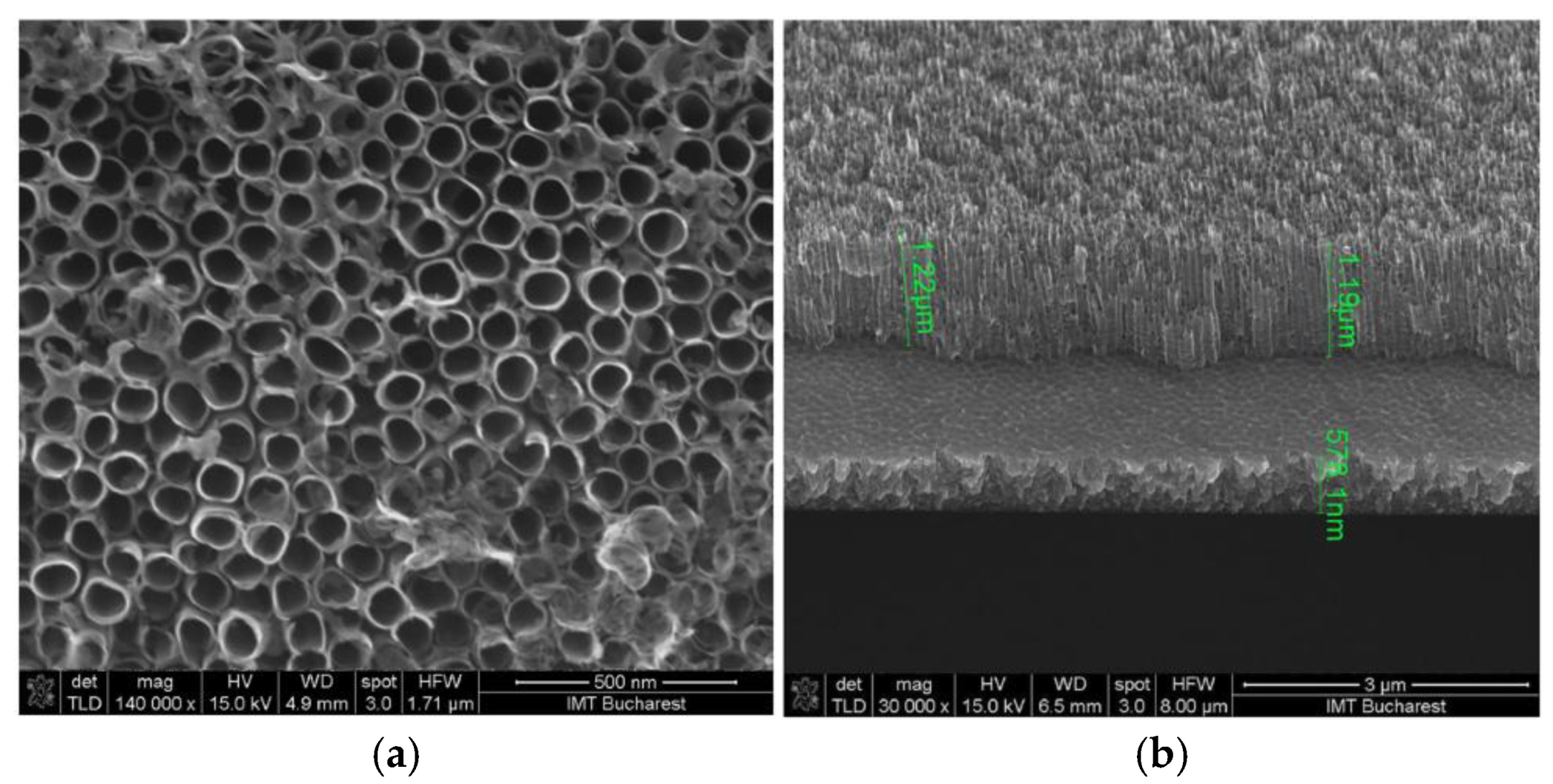

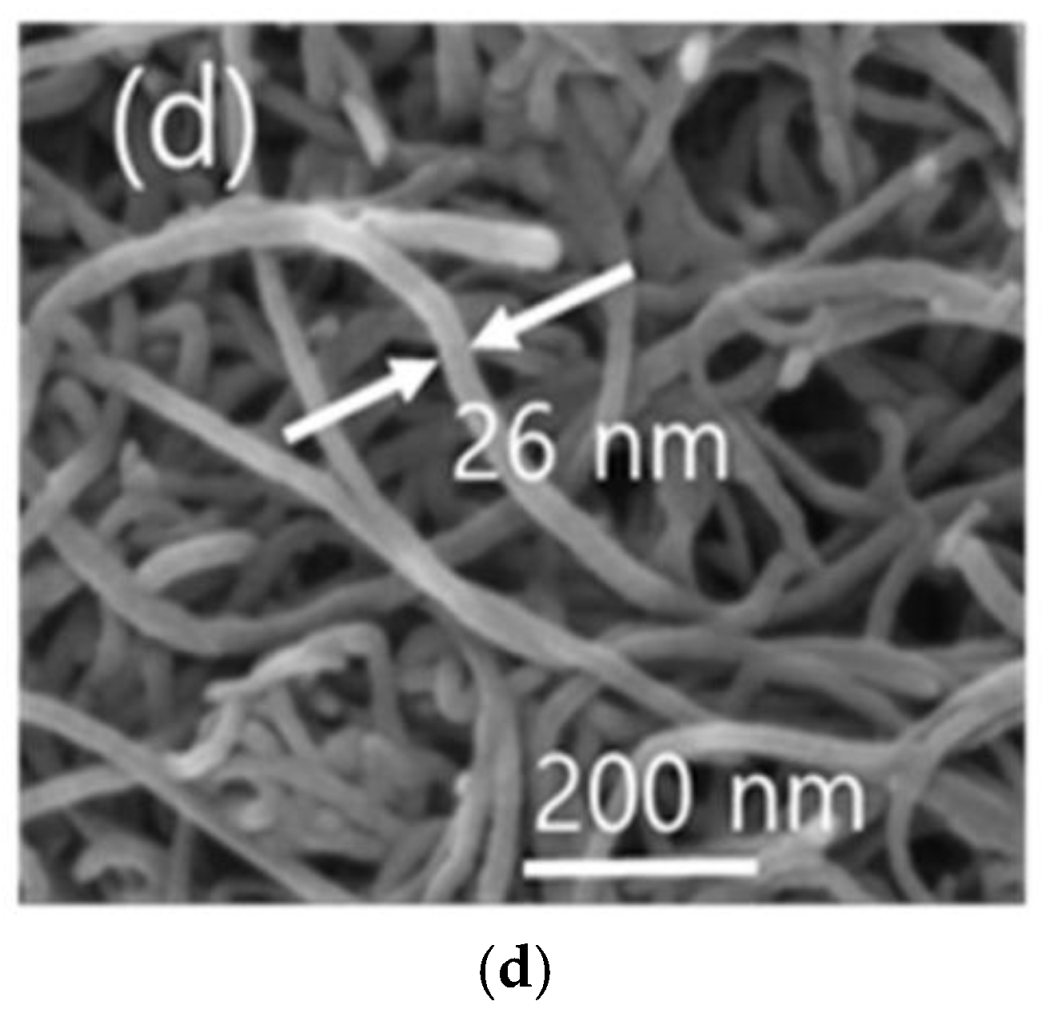

3.3. Nano-Structured TiO2 Grown on Si-Wafer

4. Other Oxides Used in ISFET and Related-Transistors Construction

5. Discussions About Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vyas, P.B.; Zhao, C.; Dag, S.; Pal, A.; Bazizi, E.M.; Ayyagari-Sangamalli, A. Next Generation Gate-all-around Device Design for Continued Scaling Beyond 2 nm Logic. International Conference on Simulation of Semiconductor Processes and Devices (SISPAD) Kobe, Japan 2023, 1, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refai-Ahmed, G.; Zhirnov, V.V.; Park, S.B.; Helmy, A.S.; Sammakia, B.; Ghose, K.; Ang, J.A.; Bonilla, G.; Mahdi, T.; Wieser, J.; Ramalingam, S. New Roadmap for Microelectronics: Charting the Semiconductor Industry’s Path Over the Next 5, 10, and 20 Years. 26th IEEE Electronics Packaging Technology Conference EPTC, Singapore, 2024, 1, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, A.; Ghafar-Zadeh, E. Emerging Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors for Life Science Applications. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravariu, C. Current Status of Field-Effect Transistors for Biosensing Applications. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, H.; Singh, K.R.B.; Natarajan, A.; Pandey, S.S. Advances in field effect transistor based electronic devices integrated with CMOS technology for biosensing. Talanta Open 2025, 11, 8, 100394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, C. Fundamentals of chemical sensors and biosensors, Chapter 1, Editor(s): Jeong-Yeol Yoon, Chenxu Yu. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Chemical and Biological Sensing. Elsevier Science 2024, 1-21. pp. 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Musala, S.; Srinivasulu, A.; Appasani, B.; Ravariu, C. Low Power High Speed FINFET Based Differential Adder Circuits With Proposed Carry/Carrybar Structures. University Politehnica of Bucharest Scientific Bulletin Series C Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 2023, 85, 335–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ravariu, C.; Srinivasulu, A.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Musala, S. Generalized Analytical Model for Enzymatic BioFET Transistors. Biosensors 2022, 7, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.A.; Piramidowicz, R. Integrated Photonic Sensors for the Detection of Toxic Gasses - A Review. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lu, A.; Li, W.; Yu, S. NeuroSim V1.4: Extending Technology Support for Digital Compute-in-Memory Toward 1nm Node. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2024, 71, 1733–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughedda, A.; Pancheri, L.; Parmesan, L.; Gasparini, L.; Quarta, G.; Perenzoni, D.; Perenzoni, M. The Modeling of a Single-Electron Bipolar Avalanche Transistor in 150 nm CMOS. Sensors 2025, 25, 3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubanova, O.; Poletaev, A.; Komarova, N.; Grudtsov, V.; Ryazantsev, D.; Shustinskiy, M.; Shibalov, M. A. Kuznetsov, A novel extended gate ISFET design for biosensing application compatible with standard CMOS. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2024, 177, 108387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravariu, C.; Mihaiescu, D.; Morosan, A.; Vasile, B.S.; Purcareanu, B. Sulpho-Salicylic Acid Grafted to Ferrite Nanoparticles for n-Type Organic Semiconductors. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamani, T. , Baz, A.; Patel, S.K., Design of an Efficient Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for Label-Free Detection of Blood Components. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 3147–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajiga, O.M.; Jameson, S.B.; Carter, B.H.; Wesson, D.M.; Mitzel, D.; Londono-Renteria, B. Artificial Feeding Systems for Vector-Borne Disease Studies. Biology 2024, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eidi, A. Design and evaluation of an implantable MEMS based biosensor for blood analysis and real-time measurement. Microsystem Technology 2023, 29, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, C.; DeMas-Giménez, G.; Royo, S. Overview of Biofluids and Flow Sensing Techniques Applied in Clinical Practice. Sensors 2022, 22, 6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelenis, D.; Barauskas, D.; Dzikaras, M.; Viržonis, D. Four-Channel Ultrasonic Sensor for Bulk Liquid and Biochemical Surface Interrogation. Biosensors 2024, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leau, S. A.; Diaconu, I.; Lete, C.; Matei, C.; Lupu, S. Electro analysis of serotonin at platinum nanoparticles modified electrode. University Politehnica of Bucharest Scientific Bulletin Series C Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 2024, 86, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal Eddin, F.B.; Fen, Y.W. The Principle of Nanomaterials Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensors and Its Potential for Dopamine Detection. Molecules 2020, 25, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravariu, C.; Popescu, A.; Podaru, C.; Manea, E.; Babarada, F. The Nanopous Al2O3 Material Used for the Enzyme Entrapping in a Glucose Biosensor. XII Mediterranean Conference on Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing MEDICON 2010, Chalkidiki, Greece, Springer Proceedings, vol. 29, pp. 459-462.

- Ryazantsev, D.; Shustinskiy, M.; Sheshil, A.; Titov, A.; Grudtsov, V.; Vechorko, V.; Kitiashvili, I.; Puchnin, K.; Kuznetsov, A.; Komarova, N. A Portable Readout System for Biomarker Detection with Aptamer-Modified CMOS ISFET Array. Sensors 2024, 24, 3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravariu, C.; Podaru, C.; Manea, E. Design and technological characterization aspects of a gluco-detector BioFET. 32nd IEEE International Semiconductor Conference, Sinaia, Romania 2009, 281-284. [CrossRef]

- Minamiki, T.; Sekine, T.; Aiko, M.; Su, S.; Minami, T. An organic FET with an aluminum oxide extended gate for pH sensing. Sensors and Materials 2019, 31, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushparaj, K.; Di Zazzo, L.; Allegra, V.; Capuano, R.; Catini, A.; Magna, G.; Paolesse, R.; Di Natale, C. Detection of Ascorbic Acid in Tears with an Extended-Gate Field-Effect Transistor-Based Electronic Tongue Made of Electropolymerized Porphyrinoids on Laser-Induced Graphene Electrodes. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhinav, V.; Naik, T.R. Low-Cost, Point-of-Care Potassium Ion Sensing Electrode in EGFET Configuration for Ultra-High Sensitivity. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 121837–121845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmpakos, D.; Apostolakis, A.; Jaber, F.; Aidinis, K.; Kaltsas, G. Recent Advances in Paper-Based Electronics: Emphasis on Field-Effect Transistors and Sensors. Biosensors 2025, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, S. B., Aqilah Azlan; Mahzan, N. H.; Zulkifli, Z.; Zulkefle, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; M.A., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Herman, S.H. Understanding the Extended-gate FET pH Sensor Sensing Mechanism through Equivalent Circuit Simulation in LTSpice. IEEE International Conference on Automatic Control and Intelligent Systems (I2CACIS), Shah Alam, Malaysia. 2024; 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.M.; Lin, L-A.; Ding, H-Y.; Her, J-L.; Pang, S-T. A simple and highly sensitive flexible sensor with extended-gate field-effect transistor for epinephrine detection utilizing InZnSnO sensing films. Talanta 2024, 275, 126178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, A.L.T. , Teo, E.Y.L., Seenivasagam, S., Hung, Y.P., Boonyuen S., Chung E.L.T., Lease J., Andou Y. Nanostructures embedded on porous materials for the catalytic reduction of nitrophenols: a concise review. Journal of Porous Materials 2024, 31, 1557–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Luo, Q.; Song, X. An antibody nanopore-enabled microsensor for detection of osteoprotegerin. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 2024, 63, 11, 117001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, S.A. , Temprano-Coleto F., Kaneelil P.R., Knopp R., Taylor A.J., Storey-Matsutani M.A., Wilson J.L., Saleh M.S., Konicek, A.R. Effect of capillary number and viscosity ratio on multiphase displacement in microscale pores. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2025, 10, 054201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, M.; Kim, S.; Park, N. Stimuli-Responsive DNA Hydrogel Design Strategies for Biomedical Applications. Biosensors 2025, 15, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, Z.; Veenuttranon, K.; Lu, X.; Chen, J. Recent Advances in the Fabrication and Application of Electrochemical Paper-Based Analytical Devices. Biosensors 2024, 14, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbaz, A., Hussain. Immobilized Enzymes-Based Biosensing Cues for Strengthening Biocatalysis and Biorecognition. Catal. Lett. 2022, 152, 2637–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

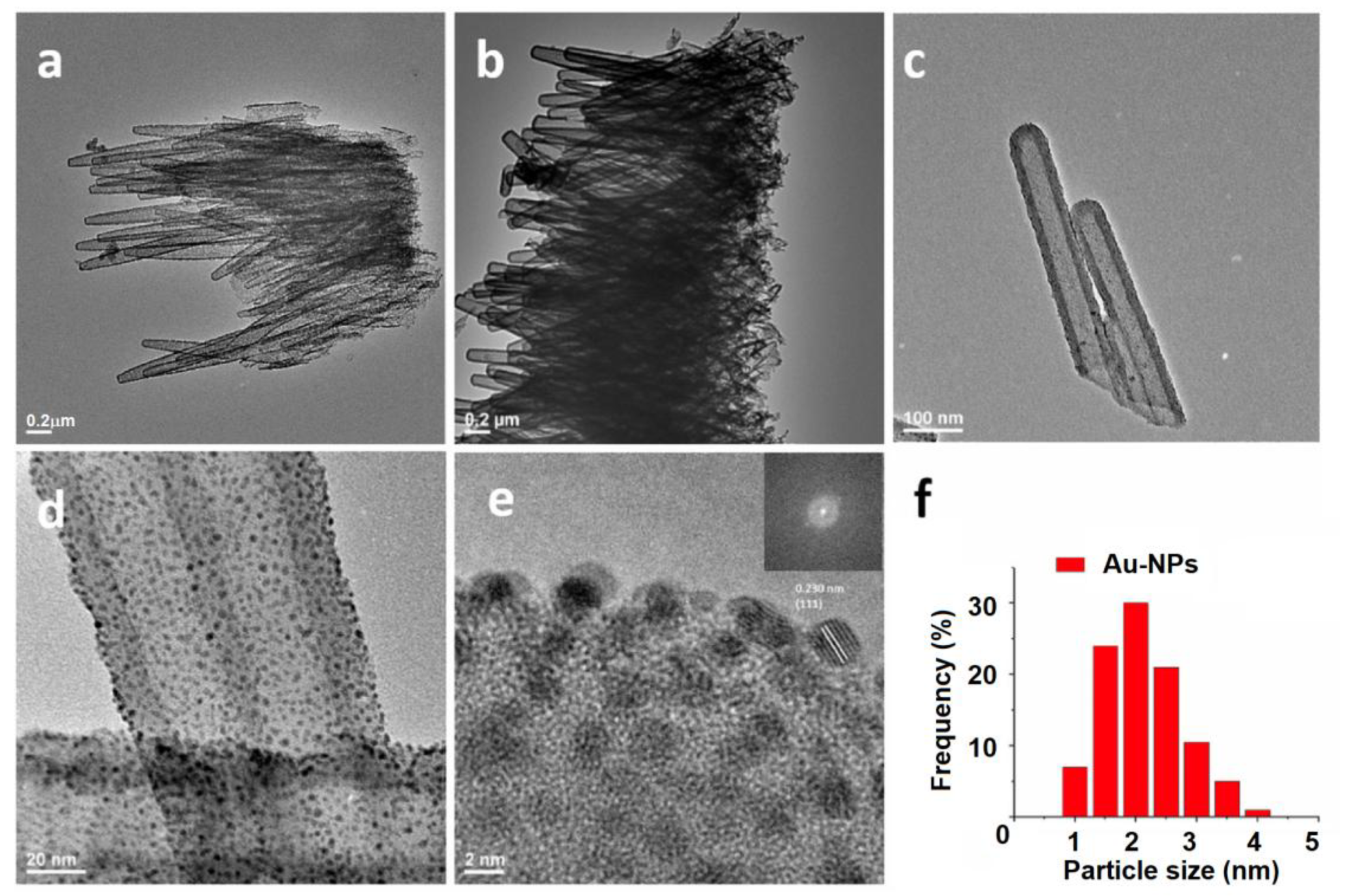

- Ravariu, C.; Manea, E.; Parvulescu, C.; Babarada, F.; Popescu, A. Titanium dioxide nanotubes on silicon wafer designated for GOX enzymes immobilization. Digest Journal of Nanomaterials and Biostructures 2011, 6, 2, 703–707. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, S. Silica sol–gel composite film as an encapsulation matrix for the construction of an amperometric tyrosinase-based biosensor. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2000, 15, 7–8, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Chaudhury, N.K. Entrapment of biomolecules in sol–gel matrix for applications in biosensors: Problems and future prospects. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2007, 22, 11, 2387–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravariu, C.; Parvulescu, C.C.; Manea, E.; Tucureanu, V. Optimized Technologies for Cointegration of MOS ransistor and Glucose Oxidase Enzyme on a Si-Wafer. Biosensors 2021, 11, 12, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelofs, K.G.; Wang, J.; Sintim, H.O.; Leea, V.T. Differential radial capillary action of ligand assay for high-throughput detection of protein-metabolite interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 37, 15528–15533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-J.; Lu, S.-Y.; Tseng, C.-C.; Huang, K.-H.; Chen, T.-L.; Fu, L.-M. Rapid Microfluidic Immuno-Biosensor Detection System for the Point-of-Care Determination of High-Sensitivity Urinary C-Reactive Protein. Biosensors 2024, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mah, D.-G.; Oh, S.-M.; Jung, J.; Cho, W.-J. Enhancement of Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect Transistors through Sol-Gel Processed Lead Zirconate Titanate Ferroelectric Film Integration and Coplanar Gate Sensing Paradigm. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prall, K. Chapter: Mobile Ion Contamination. In book: CMOS Plasma and Process Damage. Springer Cham. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-T.; Hsiao, C.-Y.; Lee, H.-W.; Kuo, C.-F. Comparison between Different Configurations of Reference Electrodes for an Extended-Gate Field-Effect Transistor pH Sensor. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 8433−8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharathi, G.; Hong, S. Gate Engineering in Two-Dimensional (2D) Channel FET Chemical Sensors: A Comprehensive Review of Architectures, Mechanisms and Materials. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.-P.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Lee, C.-H.; Vu, C.-A.; Chen, W.-Y. Comparing solution-gate and bottom-gate nanowire field-effect transistors on pH sensing with different salt concentrations and surface modifications. Talanta 2024, 271, 125731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garika, V.; Babbar, S.; Samanta, S.; Harilal, S.; Lerner, A.E.; Rotfogel, Z.; Pikhay, E.; Shehter, I.; Elkayam, A.; Bashouti, M.Y.; Akabayov, B.; Ron, I.; Hazan, G.; Roizin, Y.; Shalev, G. Addressing the challenge of solution gating in biosensors based on field-effect transistors. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2024, 265, 116689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergveld, P. Development, operation and application of the ion sensitive field effect transistor as a tool for electrophysiology. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. BME 1972, 19, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janićijević, Ž.; Baraban, L. Integration Strategies and Formats in Field-Effect Transistor Chemo- and Biosensors: A Critical Review. ACS Sensors 2025, 10, 4, 2431–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, S. , Alharbi, Y., Alqahtani, A. Nanomaterials Connected to Bioreceptors to Introduce Efficient Biosensing Strategy for Diagnosis of the TORCH Infections: A Critical Review. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 55, 4, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergveld, P. Thirty years of ISFETOLOGY What happened in the past 30 years and what may happen in the next 30 years. Sensors and Actuators B 2003, 88, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravariu, C. MOSFET with tips and tricks. e-Book Politehnica Press Publisher 2023, Bucharest, Romania, pp. 56-59.

- R.E.G. van Hal, J.C.T. Eijkel, P. Bergveld. A novel description of ISFET sensitivity with the buffer capacity and double layer capacitance as key parameters. Sensors and Actuators B 1995, 24/25, 201–205.

- M. Esashi, T. Matsuo. Integrated micro multi ion sensor using field effect of semiconductor. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. BME 1978, 25, 184–192.

- Sakai, T. Ion sensitive FET with a silicon–insulator silicon structure. Proceedings of the Transducer-87.

- Hyun, T.-H.; Cho, W.-J. High-Performance FET-Based Dopamine-Sensitive Biosensor Platform Based on SOI Substrate. Biosensors 2023, 13, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J.M. Chovelon, N. Jaffrezic-Renault, Y. Cros, J.J. Fombon, D. Pedone, Monitoring of ISFET encapsulation aging by impedance measurements. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 1991, 3, 43–50. [CrossRef]

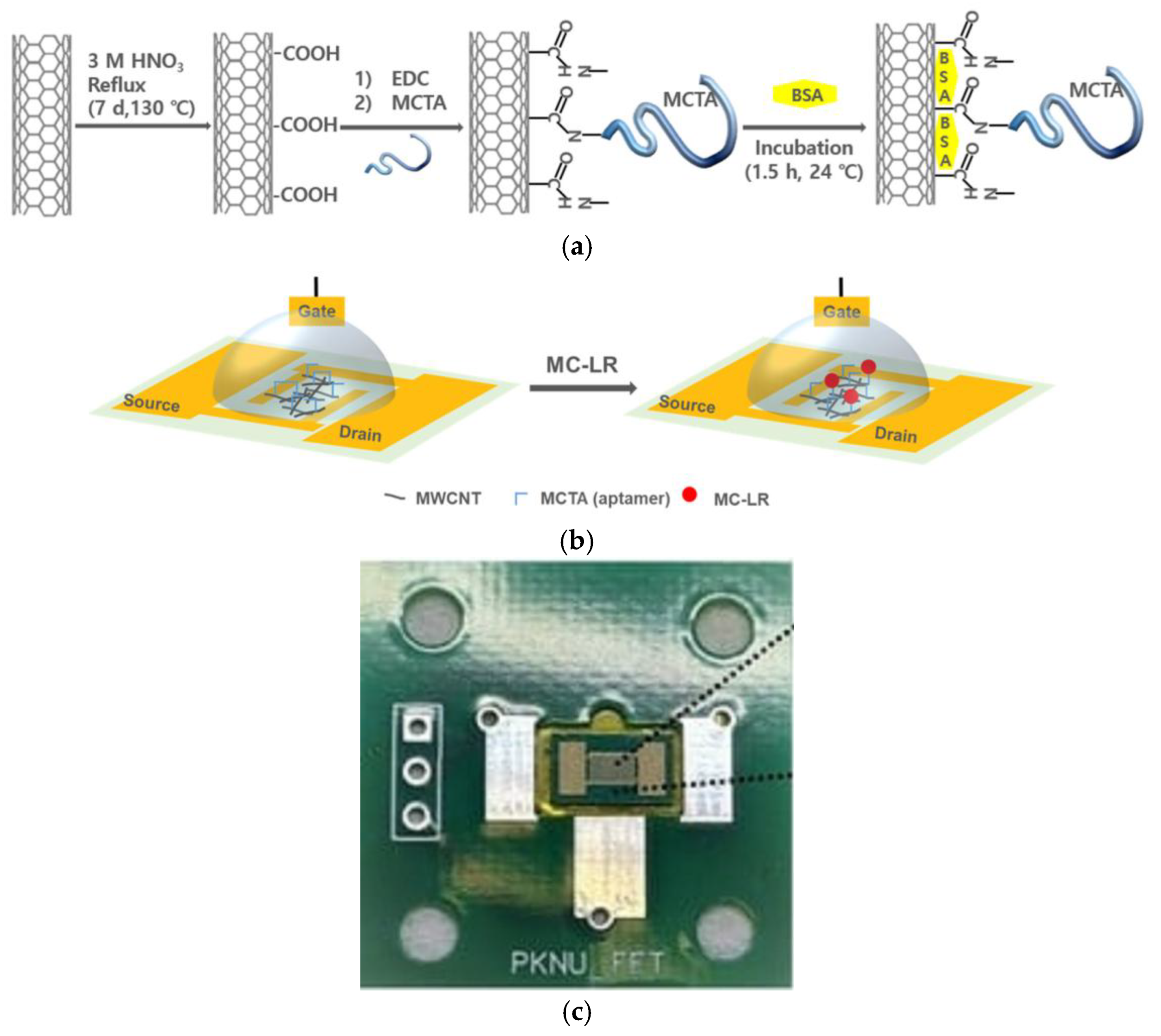

- Nandanwar, S.; Lee, S.; Park, M.; Kim, H.J. Label-Free Extended Gate Field-Effect Transistor for Sensing Microcystin-LR in Freshwater Samples. Sensors 2025, 25, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, M.; Ravariu, C.; Hascsi, Z. First and Second Order Digital Circuits with Neuronal Models under Pulses Train Stimulus. Romanian Journal of Information Science and Technology ROMJIST 2025, 28, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, T.M. Development of macroporous silicon for bio-chemical sensing applications. Journal of Microelectronic Engineering Conference 2005, 15, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

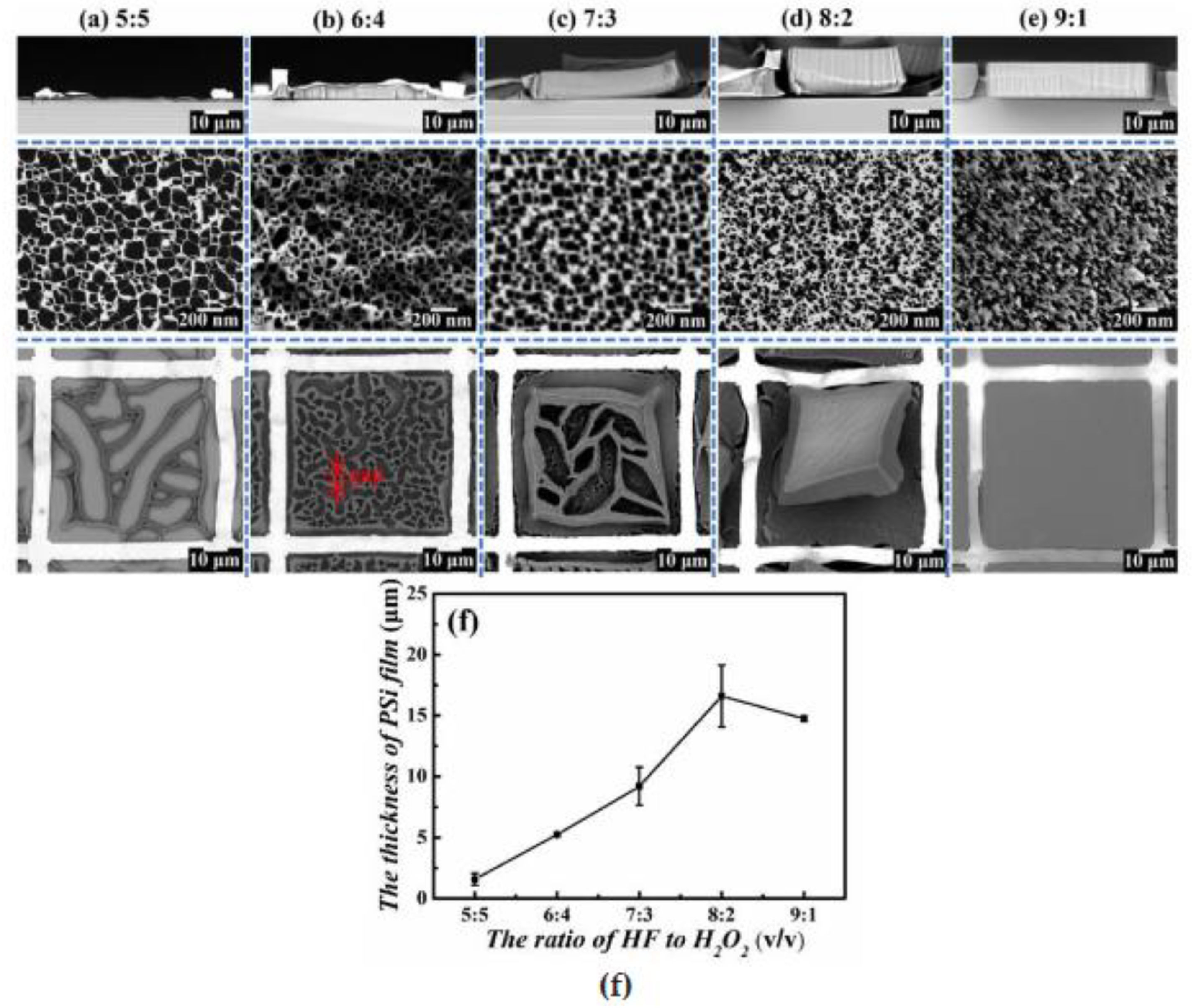

- Manea, E.; Podaru, C.; Popescu, A.; Budianu, E.; Purica, M.; Babarada, F.; Parvulescu, C. Nano-Porous Silicon for Sensors and Solar Cells. AIP Conf. Proceedings 2007, 899, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavatski, S.; Popov, A.I.; Chemenev, A.; Dauletbekova, A.; Bandarenka, H. Wet Chemical Synthesis and Characterization of Au Coatings on Meso- and Macroporous Si for Molecular Analysis by SERS Spectroscopy. Crystals 2022, 12, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-González, F.; García-Salgado, G.; Rosendo, E.; Díaz, T.; Nieto-Caballero, F.; Coyopol, A.; Romano, R.; Luna, A.; Monfil, K.; Gastellou, E. Porous Silicon Gas Sensors: The Role of the Layer Thickness and the Silicon Conductivity. Sensors 2020, 20, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Jin, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, S.; Shui, L. Wafer-Scale Fabrication and Transfer of Porous Silicon Films as Flexible Nanomaterials for Sensing Application. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rodriguez, R.; Hathaway, E.; Coffer, J.L.; del Castillo, R.M.; Lin, Y.; Cui, J. Gold Nanoparticles in Porous Silicon Nanotubes for Glucose Detection. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Liao, L.; Shen, X.; Mei, Z.; Du, Q.; Liang, L.; Lei, B.; Du, J. Advancement in Research on Silicon/Carbon Composite Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Metals 2025, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awawdeh, K.; Buttkewitz, M.A.; Bahnemann, J.; Segal, E. Enhancing the performance of porous silicon biosensors: the interplay of nanostructure design and microfluidic integration. Microsystems & Nanoengineering 2024, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, K.A.; Kosewski, G.; Dobrzyńska, M.; Drzymała-Czyż, S. Lactoferrin Production: A Systematic Review of the Latest Analytical Methods. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

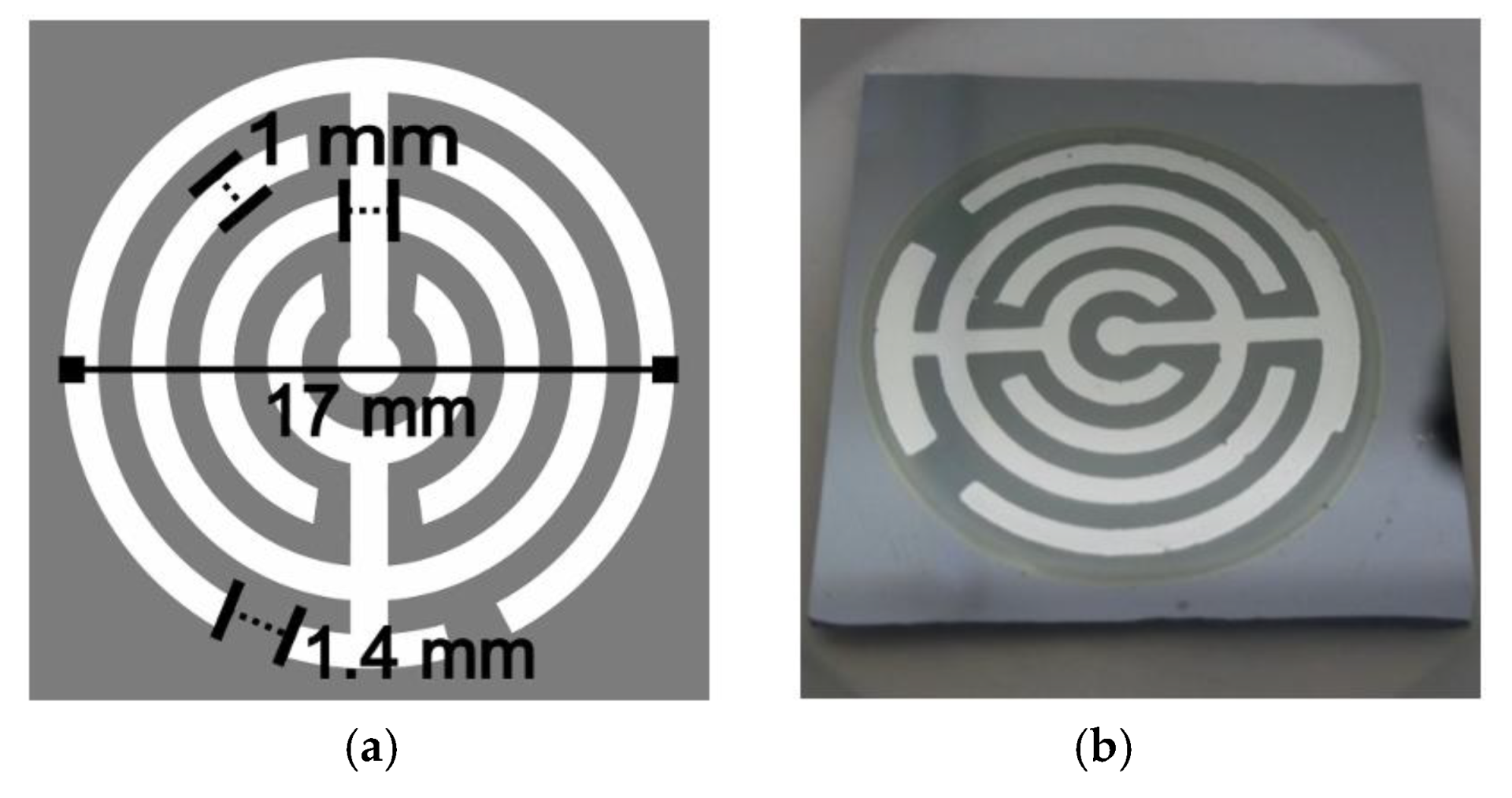

- Babarada, F.; Ravariu, C.; Bajenaru, A.; Manea, E. From simulations to masks for a BioFET design. IEEE, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Shim, J.; Bala, A.; Park, H.; Kim, S. Boosting Sensitivity and Reliability in Field-Effect Transistor-Based Biosensors with Nanoporous MoS2 Encapsulated by Non-Planar Al2O3. Advanced Functional Materials 2023, 33, 42, 2301919:1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

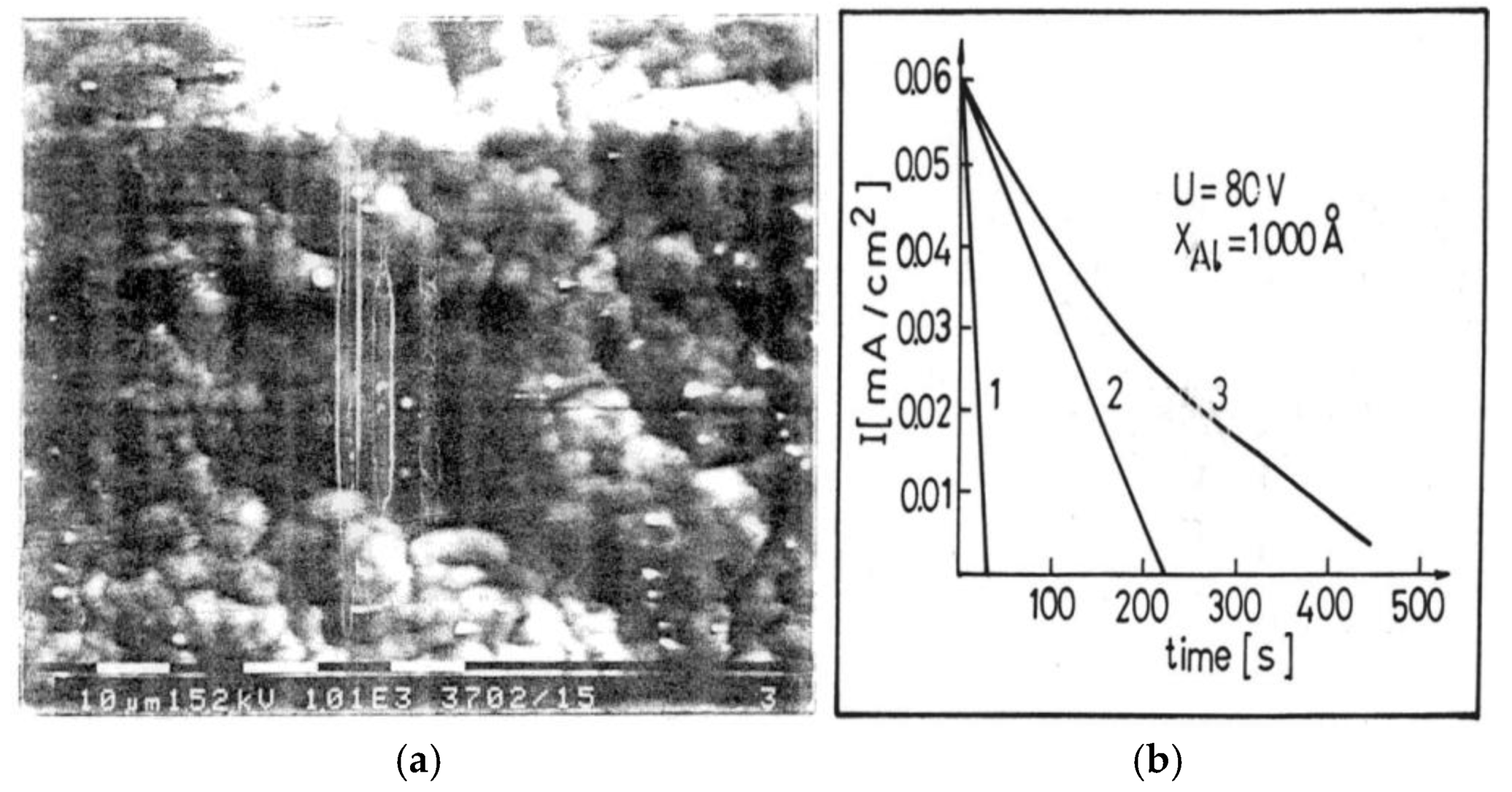

- Khanna, V.K. A plausible ISFET drift-like aging mechanism for Al2O3 humidity sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2015, 213, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E.A.; Abdolkader, T.M. A review of ion-sensitive field effect transistor (ISFET) based biosensors. International Journal of Materials Technology and Innovation 2023, 3, 3, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, A.R.; Elshafie, H.; Changalasetty, S.B.; Mubarakali, A. Optimizing Thermal Characteristics and Mobility in Sub-10 nm β-(AlxGa1−x)2O3/Ga2O3 Tri-Metal MODFETs for Advanced Biosensing Applications. ECS Journal of Solid State Science and Technology 2025, 14, 017005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeban, Y. Effectiveness of CAD-CAM Milled Versus DMLS Titanium Frameworks for Hybrid Denture Prosthesis: A Narrative Review. J. Funct. Biomater 2024, 15, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, E.; Lanzutti, A. Biomedical Applications of Titanium Alloys: A Comprehensive Review. Materials 2024, 17, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravariu, C.; Manea, E.; Babarada, F. Masks and metallic electrodes compounds for silicon biosensor integration. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2017, 697, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D-J; Kim, H-G.; Cho, S-J.; Choi, W-I. Thickness-conversion ratio from titanium to TiO2 nanotube fabricated by anodization method. Materials Letters 2008, 62, 775. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C.; Chen, K.-Y.; Su, Y.-K. TiO2 Nano Flowers Based EGFET Sensor for pH Sensing. Coatings 2019, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkefle, M.A.; Rahman, R.A.; Rusop, M.; Abdullah, W.F.H.; Herman, S.H. Porous TiO2 thin film for EGFET pHsensing application. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravariu, C.; Manea, E.; Pârvulescu, C.; Țucureanu, V.; Appasani, B.; Srinivasulu, A. Preliminary simulations and experiments of enzymatic MOS biosensors. Proc. of IEEE Annual Conference of Semiconductors CAS, 2024; 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.M. Interdigitated extended gate field effect transistor without reference electrode. Journal of Electronic Materials 2017, 46, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, H.; Ji, Z.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y. ZnO nano-array-based EGFET biosensor for glucose detection. Appl. Phys. A 2015, 119, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, E.M.; Mulato, M. Synthesis and characterization of vanadium oxide/hexadecylamine membrane and its application as pH-EGFET sensor. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2009, 52, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jrar, J.A.; Bilal, M.; Butt, F.K.; Zhang, Z.; Din, A.U.; Hou, J. A novel 2D graphene oxide/manganese vanadium oxide nanocomposite-based PEC biosensor for selective detection of glucose. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2025, 1021, 179595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.M. Yang, C.M.; Wei, C-H; Ughi, F.; Chang, J-Y.; Pijanowska, D.G.; Lai, C-S. High pH stability and detection of α-synuclein using an EGFET biosensor with an HfO2 gate deposited by high-power pulsed magnetron sputtering. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2024, 416, 136006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Seung Rim, Y.; Chen, H.; Cao, H.H.; Nakatsuka, N.; Hinton, H.L.; Zhao, C.; Andrews, A.M.; Yang, Y.; Weiss, P.S. Fabrication of High-Performance Ultrathin In2O3 Film Field-Effect Transistors and Biosensors Using Chemical Lift-Off Lithography. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 4, 4572–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, T.; Liu, X.; Li, C.; Lei, B.; Zhang, D.; Rouhanizadeh, M.; Hsiai, T.; Zhou, C. Complementary Response of In2O3 Nanowires and Carbon Nanotubes to Low-Density Lipoprotein Chemical Gating. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 103903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curreli, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Lei, B.; Gundersen, M. A.; Thompson, M. E.; Zhou, C. Selective Functionalization of In2O3 Nanowire Material Devices for Biosensing Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6922–6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkington, D.; Cooling, N.; Belcher, W.; Dastoor, P.C.; Zhou, X. Organic Thin-Film Transistor (OTFT)-Based Sensors. Electronics 2014, 3, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravariu, C.; Istrati, D.; Mihaiescu, D.; Morosan, A.; Purcareanu, B.; Cristescu, R.; Trusca, R.; Vasile, B. Solution for green organic thin film transistors: Fe3O4 nano-core with PABA external shell as p-type film. Journal of Materials Science - Materials in Electronics 2020, 31, 4, 3063–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Wang, K.; Lu, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, H.; Li, R.; Shi, M.; Wu, L.; Yan, F.; Jiang, R. Uniform Oxide Layer Integration in Amorphous IGZO Thin Film Transistors for Enhanced Multilevel-Cell NAND Memory Performance. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiong, X.; Li, H.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Liang, Z.; Yao, R.; Ning, H.; Wei, X. Application of Solution-Processed High-Entropy Metal Oxide Dielectric Layers with High Dielectric Constant and Wide Bandgap in Thin-Film Transistors. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, F.; Ashfaq Ahmed, M.; Jalal, A.H.; Siddiquee, I.; Adury, R.Z.; Hossain, G.M.M.; Pala, N. Recent Progress and Challenges of Implantable Biodegradable Biosensors. Micromachines 2024, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosri, E.; Ibrahim, F.; Thiha, A.; Madou, M. Micro and Nano Interdigitated Electrode Array (IDEA)-Based MEMS/NEMS as Electrochemical Transducers: A Review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuanaeva, R.M.; Vaneev, A.N.; Gorelkin, P.V.; Erofeev, A.S. Nanopipettes as a Potential Diagnostic Tool for Selective Nanopore Detection of Biomolecules. Biosensors 2024, 14, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Tan, R.; Feng, M.; Shen, W.; Lv, D.; Song, W. Humidity Sensing Using Polymers: A Critical Review of Current Technologies and Emerging Trends. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.J. Rapid and Easy Detection of Microcystin-LR Using a Bioactivated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube-Based Field-Effect Transistor Sensor. Biosensors 2024, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedel, V.; Hinck, S.; Peiter, E.; Ruckelshausen, A. Concept and Realisation of ISFET-Based Measurement Modules for Infield Soil Nutrient Analysis and Hydroponic Systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Xia, B.; Peng, J. Multiscale Dynamic Diffusion Model for Ions in Micro- and Nano-Porous Structures of Fly Ash: Mineralization Experimental Research. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellando, F.; Mele, L.J.; Palestri, P.; Zhang, J.; Ionescu, A.M.; Selmi, L. Sensitivity, Noise and Resolution in a BEOL-Modified Foundry-Made ISFET with Miniaturized Reference Electrode for Wearable Point-of-Care Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Rupakula, M.; Bellando, F.; Garcia, E.; Longo, J.; Wildhaber, F.; Herment, G.; Guérin, H.; Ionescu, A.M. Sweat Biomarker Sensor Incorporating Picowatt Three-Dimensional Extended Metal Gate Ion Sensitive FET Transistors. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 2039–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totorica, N.; Hu, W.; Li, F. Simulation of different structured gate-all-around FETs for 2 nm node. IOP Engineering Research Express 2024, 6, 035326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Alharbi, A.; You, K. D.; Kisslinger, K.; Stach, E. A.; Shahrjerdi, D. Experimental Study of the Detection Limit in Dual Gate Biosensors Using Ultrathin Silicon Transistors. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 7142−7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Mahanty, B.; Mohapatra, P.K.; Sen, D.; Ghosh, S.K.; Sengupta, A.; Verboom, W. Development of a dual sensitive N,N,N’,N’,N”,N”-hexa-n-octylnitrilotriacetamide (HONTA) based potentiometric sensor for direct thorium(IV) estimation. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2024, 410, 135660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

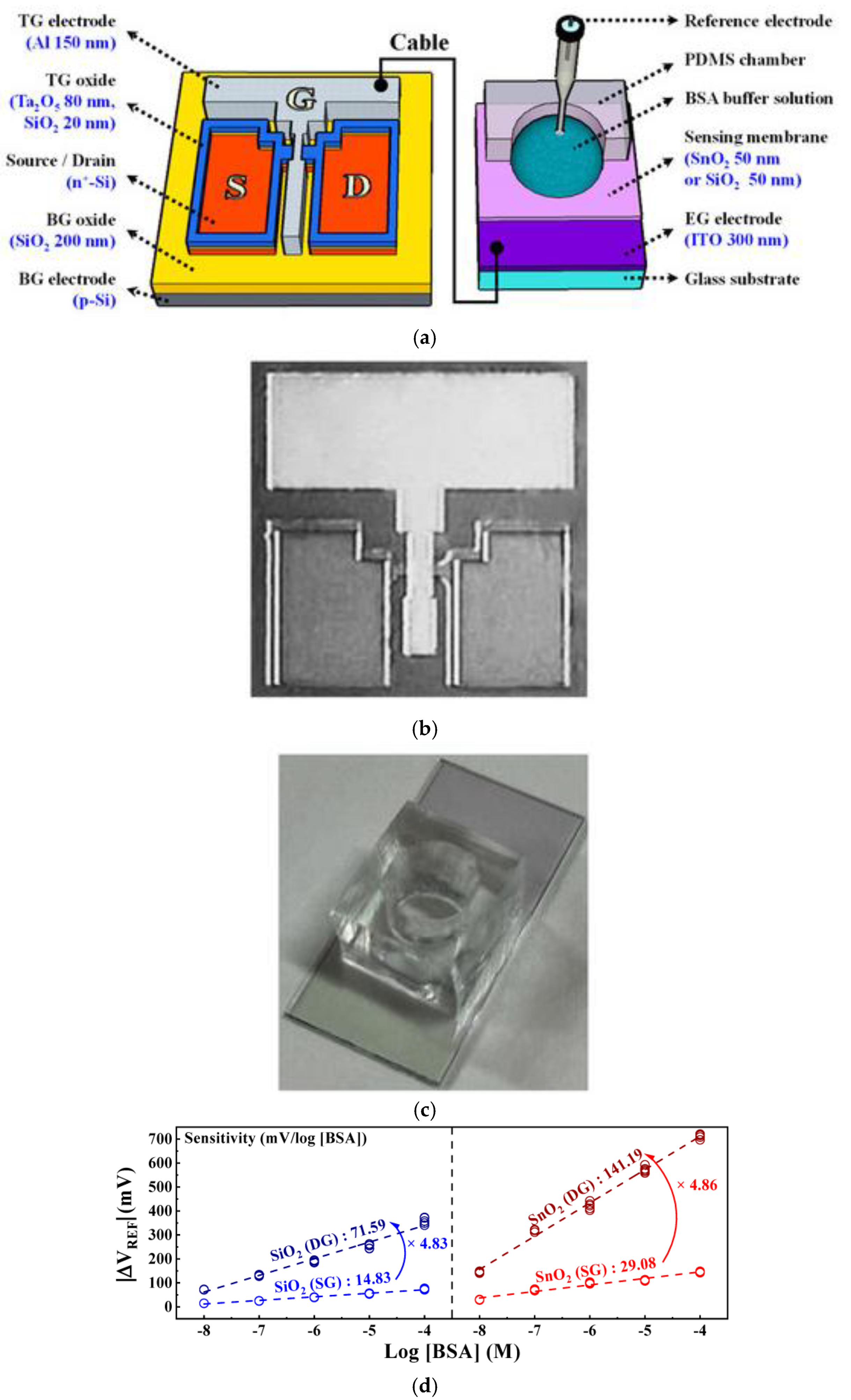

- Kim, Y.-U.; Cho, W.-J. Enhanced BSA Detection Precision: Leveraging High-Performance Dual-Gate Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect-Transistor Scheme and Surface-Treated Sensing Membranes. Biosensors 2024, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firek, P.; Cichomski, M.; Waskiewicz, M.; Piwonski, I.; Kisielewska, A. ISFET Structures with Chemically Modified Membrane for Bovine Serum Albumin Detection. Circuit World 2018, 44, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, J.; Nair, P. R.; Alam, M. A. Theory of Signal and Noise in Double-Gated Nanoscale Electronic pH Sensors. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 034516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, P. A.; Cumming, D. R. S. Performance and system on-chip integration of an unmodified CMOS ISFET. Sens. Actuators, B 2005, 111, 254−258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capua, L.; Sprunger; Y; Elettro, H.; Risch, F.; Grammoustianou, A.; Midahuen, R.; Ernst, T.; Barraud, S.; Gill, R.; Ionescu, A.M. Label-Free C-Reactive Protein Si Nanowire FET Sensor Arrays With Super-Nernstian Back-Gate Operation. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2022, 69, 4, 2159–2165. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Luo, X.; Huang, J.; Cui, X.T.; Yun, M. Detection of cardiac biomarkers using single polyaniline nanowire-based conductometric biosensors. Biosensors 2012, 2, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.-J.; Luo, Z. H. H.; Huang, M. J.; Tay, G. K. I.; Lim, E.-J.-A. Morpholino-functionalized silicon nanowire biosensor for sequence-specific label-free detection of DNA. Biosensors Bioelectronics 2010, 25, 11, 2447–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.-J.; Chua, J. H.; Chee, R.-E.; Agarwal, A.; and Wong, S.M. Label-free direct detection of MiRNAs with silicon nanowire biosensors. Biosensors Bioelectronics 2009, 24, 8, 2504–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.-J. Silicon nanowire biosensor for highly sensitive and rapid detection of Dengue virus. Sens. Actuators B, Chem. 2010, 146, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitusevich, S. Characteristic frequencies and times, signal-to-noise ratio and light illumination studies in nanowire FET biosensors. Proc. IEEE Ukrainian Microw. Week UkrMW. [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, Y. M.; Petkov, N.; Yu, R.; Nightingale, A.M.; Buitrago, E.; Lotty, O.; deMello, J.C.; Ionescu, A.M.; Holmes, J.D. Detection of ultra-low protein concentrations with the simplest possible field effect transistor. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 324001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, I.A.; Hassan, A.; Sanches, N.M.; Vieira, N.C.S.; Crespilho, F.N. Highly sensitive interfaces of graphene electrical-electrochemical vertical devices for on drop atto-molar DNA detection. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2021, 175, 112851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabdullah, M. G. K.; Elmessary, M. A.; Nagy, D.; Seoane, N. ; García-Loureiro, A-J.; Kalna, K. Scaling Challenges of Nanosheet Field-Effect Transistors Into Sub-2 nm Nodes. 2024; 12, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).