1. Introduction

Hydrological environment is an integral component of ecosystems that provide multiple vital functions [

1]. Rivers and lakes, as an important part of the Earth’s hydrological environment, naturally purify water and maintain environmental health: processes such as filtration by riparian vegetation and sedimentation remove pollutants from runoff [

2], thereby improving water quality and buffering against ecological degradation [

3,

4,

5]. In addition, river–lake systems also help regulate regional climate conditions [

6,

7]; the presence of water bodies can mitigate urban heat island effects through evaporative cooling and heat absorption, significantly lowering local temperatures in surrounding areas [

8]. However, rapid land cover changes, including urbanization, agricultural expansion and industrial development have substantially undermined these functions [

9,

10,

11].

Diffusion-based [

12,

13,

14] generative modeling has rapidly progressed from synthesizing natural photographs to more complex modalities such as art style transfer, super-resolution, and video creation. Early work established denoising-diffusion probabilistic models as a stable, high-fidelity alternative to GANs [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], enabling photo-realistic imagery and text-to-image systems such as GLIDE [

20] and Imagen; parallel advances have extended the paradigm to video, where cascaded architectures (e.g., Imagen Video) sequentially denoise spatio-temporal volumes with impressive realism. Within remote sensing, adaptation has been comparatively recent, RSDiff [

21] introduced a two-stage cascade for text-conditioned satellite scenes, SatDM [

22] and DiffusionSat [

23] injected semantic masks or metadata to guide layout, and the latest CRS-Diff [

24] incorporates multi-condition control (text, metadata, sketches) to improve geographic consistency and downstream utility. Despite these gains, most pipelines still rely on generic prompts and ad-hoc filtering [

25], yielding artifacts that limit their value for high-precision tasks. Motivated by these gaps, our work couples ChatGPT 4o-generated [

26], class-specific descriptions with exemplar-conditioned stable diffusion and rigorous perceptual gating, producing high-fidelity, deformation-rich samples tailored for land cover applications.

Land-cover mapping has progressed from early pixel-wise statistical classifiers to modern deep-learning pipelines, yet several structural bottlenecks remain [

27,

28]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) fine-tuned from natural-image backbones have dominated recent benchmarks and achieved impressive gains in scene-level accuracy [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]; however, their fixed, square receptive fields struggle with the elongated shorelines, meandering rivers and fragmented urban parcels that typify high-resolution remote-sensing imagery [

37,

38,

39]. Transformer variants introduce global self-attention and have reduced spectral–spatial aliasing [

40,

41], but most implementations still assume regularly sampled grids and require dense, task-specific supervision that is costly to acquire. Transfer learning and self-supervised strategies alleviate data scarcity to a degree [

42,

43,

44], yet performance remains capped by the long-tailed, classimbalanced nature of real-world aerial datasets and by cross-sensor domain shifts. Parallel work in diffusion-based generation has begun to synthesize auxiliary satellite scenes (e.g., RSDiff [

21], SatDM [

22], DiffusionSat [

23]) to enrich training corpora; nevertheless, these pipelines rely on generic prompts and heuristic filtering, often yielding semantic inconsistencies and geometric artifacts that limit downstream utility [

25]. In short, existing LCLU classifiers either (i) model complex landform geometries with inflexible kernels, or (ii) augment data with imagery whose fidelity is insufficient for fine-grained mapping, leaving a gap that the present LVC2-DViT seeks to close by uniting class-balanced, description-driven diffusion sampling with a deformation-aware Vision Transformer.

In response to these challenges, we introduce the LVC2-DViT (Landview Creation for Landview Classification with Deformable Vision Transformer), an end-to-end framework designed to enhance land-use classification by combining landview creation and deformable Vision Transformers. The LVC2-DViT framework consists of two main modules. The first module utilizes the RRDBNet model within the Real-ESRGAN framework [

45,

46] for super-resolution processing. Then, ChatGPT-4o is employed to generate textual descriptions based on each class of land cover in remote sensing images. These textual descriptions, along with the original images, are used in combination with Stable Diffusion to generate new samples for data augmentation. The quality of the generated samples is carefully evaluated both manually and using specific metrics to ensure their high fidelity. The second module introduces the DViT model for land cover classification of remote sensing images. DViT utilizes the DCNv4 backbone to extract spatially rich features, which are then processed through vision-transformer to capture global context and inter-patch relationships. The integration of deformable convolutions enables dynamic adaptation to complex spatial patterns, overcoming challenges like occlusions and geometric distortions, thus improving classification performance in diverse remote sensing scenarios.

The rest part of this study is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the data and the framework that we proposed in the research.

Section 3 shows the experimental analysis.

Section 4 offers discussions about the significance, limitations and future work of the framework.

Section 5 gives the conclusions of the paper.

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Dataset

The study uses the Aerial Image Dataset (AID), which is a comprehensive large-scale remote sensing dataset designed to facilitate aerial scene classification in the domain of remote sensing [

31]. It was constructed by collecting over ten thousand high-resolution aerial images sourced from Google Earth imagery, which were processed from original optical aerial photos using RGB renderings. Although the images are derived from Google Earth, studies have shown that there is negligible difference between these images and real optical aerial photographs, even at the pixel level, making them suitable for scene classification tasks. AID includes various scene categories that span diverse geographic regions and environments, allowing for robust model evaluation [

31]. This dataset serves as an essential benchmark for the development and comparison of scene classification algorithms. It includes several critical scene categories, including ports, beaches, rivers, ponds, and bridges, which are crucial for applications related to water resource monitoring and urban planning.

For the enhancement of the resolution and detail of the aerial imagery used in our study, we applied super-resolution techniques to all images in the dataset. Specifically, the research employed the RRDBNet model within the Real-ESRGAN framework [

45], selected for its superior performance in upscaling low-resolution images while maintaining fine details and minimizing artifacts [

46]. This approach uses a network configuration with 23 residual blocks, enabling efficient learning and optimization of super-resolution tasks. The process enhances each image by a factor of four, improving its resolution while preserving critical features for accurate scene classification. By applying this method, the study ensured that the resulting imagery not only meets high-quality visual standards but also maintains computational efficiency suitable for further processing and analysis.

2.2. Framework

The LVC2-DViT framework is designed to enhance remote sensing land-use classification by combining advanced data augmentation techniques and deformation-aware classification models, which consists of two main modules. The first module employs the RRDBNet model within the Real-ESRGAN framework for super-resolution and uses ChatGPT-4o to generate textual descriptions for land cover classes, which are then combined with Stable Diffusion to create augmented samples. The second module integrates the DViT model for land cover classification, improving accuracy by handling complex landform geometries.

2.2.1. Image Diffusion

A GPT-4–assisted Stable Diffusion pipeline is adopted to enlarge the training corpus with high-fidelity remote-sensing imagery while avoiding the monotonicity that characterises conventional augmentation techniques. First, GPT-4 analyses each original AID image and produces a detailed Stable-Diffusion-style prompt that faithfully describes its semantic content [

47]. These prompts serve as positive textual conditions for a latent diffusion model, stable diffusion [

48], thus generating additional samples that preserve key attributes of the scene. Because the vanilla Stable Diffusion model, trained on generic internet photographs, may yield outputs with artistic or cartoon-like artefacts, a domain-adapted variant fine-tuned on landscape imagery is employed, together with a “Snapshot Photo Realism” LoRA module to reinforce photorealistic style [

49,

50]. Complementary negative prompts further suppress painterly textures, ensuring that the synthesized images resemble authentic aerial photographs suitable for land-cover analysis.

To retain essential spatial structure, the generation process is guided by ControlNet [

51]. Canny edge maps extracted from each source image delineate salient objects, rivers, bridges, beaches and are supplied as auxiliary conditions to the diffusion model. With a narrow edge detection threshold and adequate guidance steps, ControlNet constrains modifications to peripheral regions while preserving the core geometry of target features. Such structurally aware augmentation aligns with recent diffusion-based methods that enforce spatial consistency in remote-sensing synthesis [

49,

52,

53], and it supplies the LVC2-DViT classifier with diverse yet credible training examples, ultimately enhancing mapping performance.

2.2.2. Flashinternimage

The FlashInternImage framework serves as an advanced visual backbone for our land-use classification tasks. At the core of this architecture is the Deformable Convolution v4 (DCNv4) [

54], which significantly improves upon traditional convolutional and attention-based methods by integrating adaptive aggregation windows and dynamically adjustable weights. DCNv4 addresses previous limitations by eliminating the softmax normalization in spatial aggregation, thus improving expressivity, which simultaneously optimizing memory access to reduce computational redndancy and enhance inference speed. Compared to DCNv3 [

55], DCNv4 achieves over threefold acceleration in forward computation and substantially faster convergence. Consequently, integrating DCNv4 into the InternImage [

56] architecture, resulting in FlashInternImage, provides an impressive 80% speed increase without compromising, and even further improving, overall performance across various vision tasks.

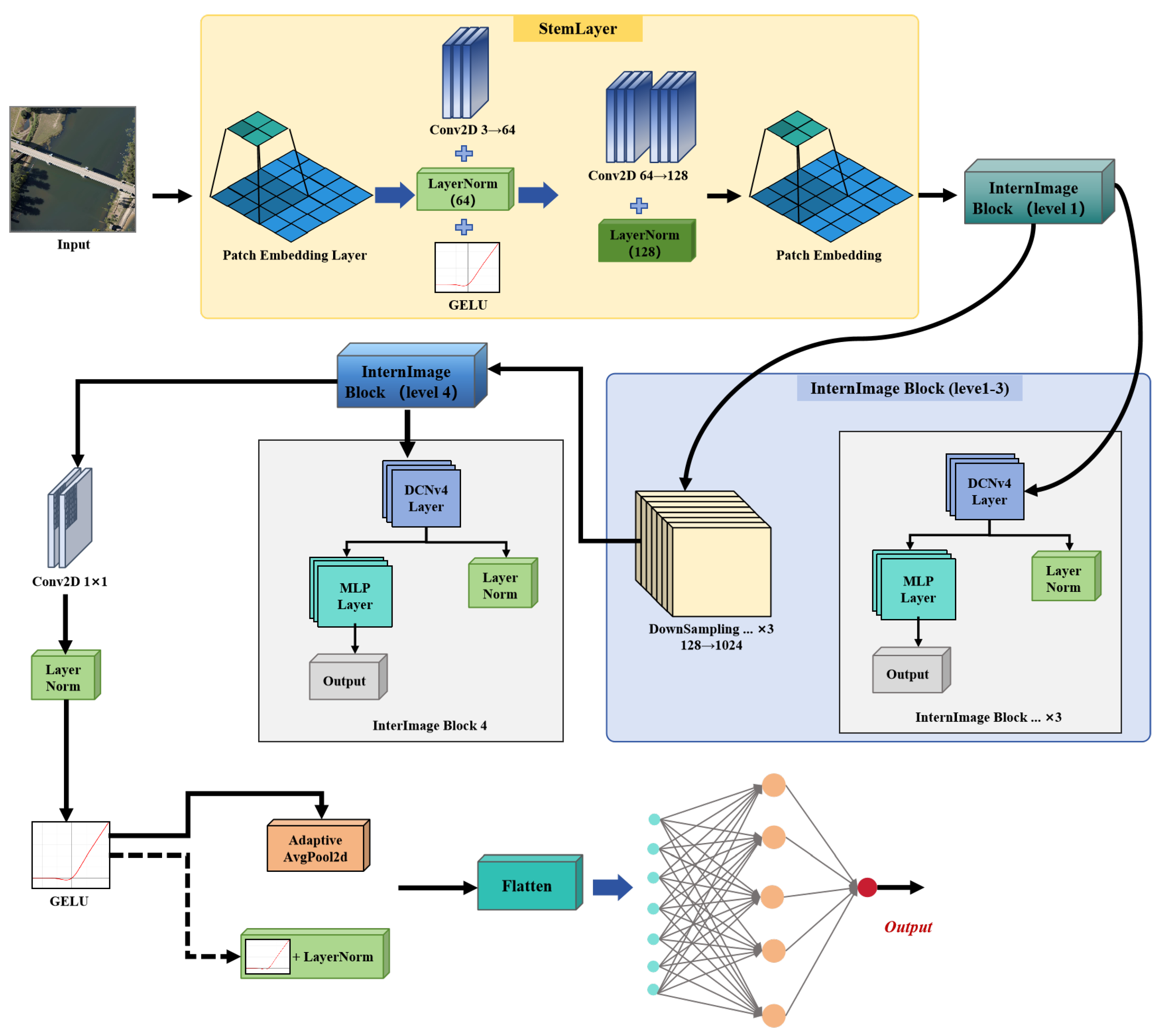

FlashInternImage adopts a hierarchical multi-stage architecture, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The input image initially undergoes preliminary feature extraction via a StemLayer, subsequently processed by multiple InternImage Blocks, each incorporating DCNv4 layers, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) layers, and normalization operations. These blocks progressively capture both local and global spatial dependencies at increasing semantic abstraction levels. Ultimately, features are aggregated through adaptive pooling, followed by fully connected layers to achieve accurate classification. Notably, FlashInternImage has demonstrated exceptional results across diverse vision benchmarks, such as image classification (achieving up to 88.1% accuracy on ImageNet-22K [

57]), instance segmentation (COCO benchmark [

58]), and semantic segmentation (ADE20K benchmark [

59]), highlighting its superior capability and robustness in managing geometric complexities inherent in high-resolution remote sensing imagery.

2.2.3. Vision-Transformer

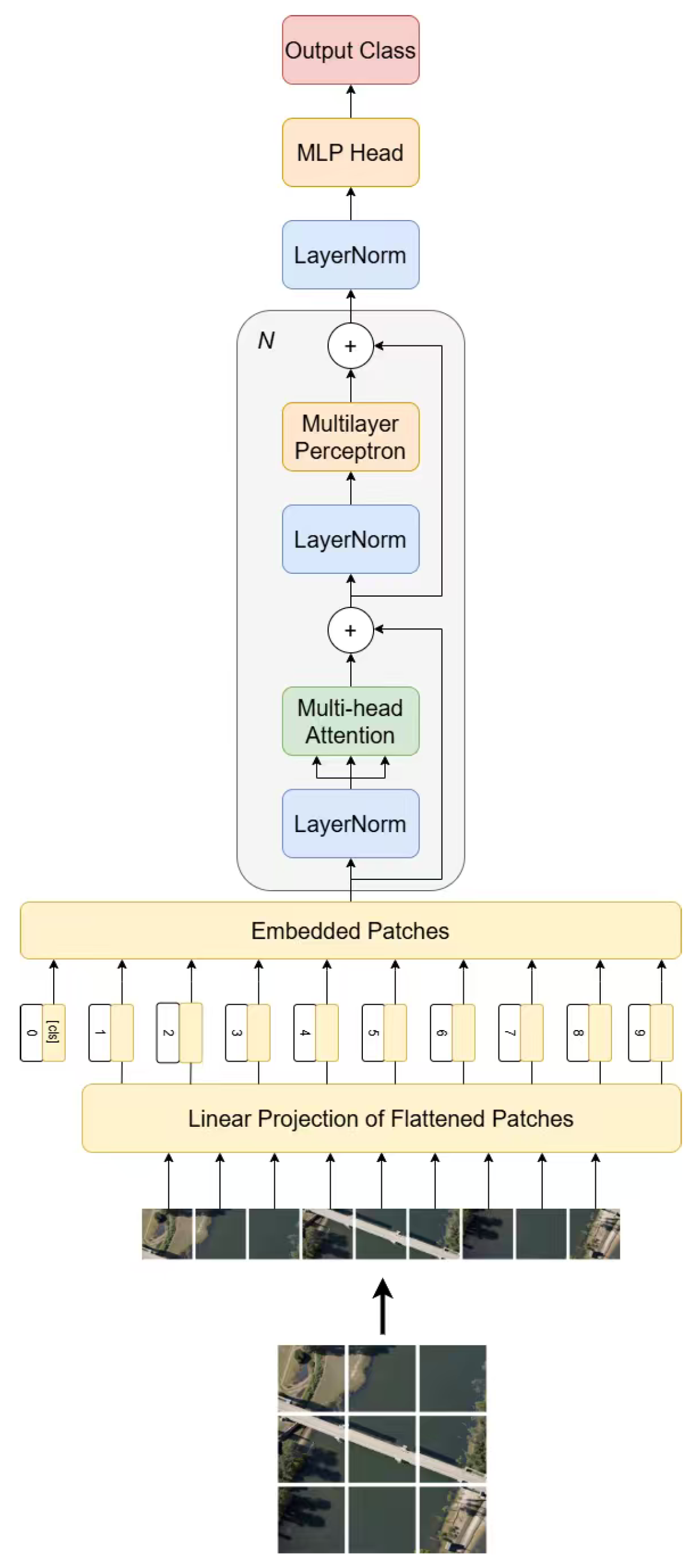

The Vision-Transformer [

60] is a classical computer vision model for classification tasks that takes the input image into non-overlapped patches and each patch is linearly mapped to a vector of the same dimension. These patches are concatenated with the learnable classification token and position encoding to form a sequence. Then, only the Encoder stack of the Transformer is used for end-to-end feature extraction. Each layer applies LayerNorm, multi-head self-attention, and a residual connection, followed by another LayerNorm, a two-layer FFN, and another residual connection. The representation of the classification token is passed to an MLP head to produce class distributions. The ViT has achieved better classification accuracies compared with traditional CNNs. However, the complexity of its self-attention calculation increases greatly with the number of patches and is insensitive to local deformations. This motivates us to integrate the deformable convolutional networks into its architecture. The overall architecture of Vision-Transformer is shown as

Figure 2.

2.2.4. Deformable Vision Transformer

Deformable Vision Transformer (DViT) is a hybrid computer vision architecture specifically designed for remote sensing land-use classification, effectively integrating fine-grained spatial information with global contextual representations [

61]. The model is constructed based on the Vision Transformer (ViT) and FlashInternImage frameworks, the latter of which builds upon DCNv4 to leverage dynamic and adaptive spatial modeling capabilities. DCNv4 specializes in handling complex geometric variations in images through its deformable convolution mechanisms, while ViT excels at capturing global contextual dependencies through self-attention mechanisms. DViT adapts these two models by concentrating on combining their complementary strengths, employing DCNv4’s robust local adaptive feature extraction capabilities in the convolutional backbone and ViT’s ability to model long-range dependencies in its transformer encoder. This adaptation ensures that the network can effectively capture both fine-grained spatial details and global contextual information, significantly enhancing the accuracy and generalizability of remote sensing land-use classification tasks.

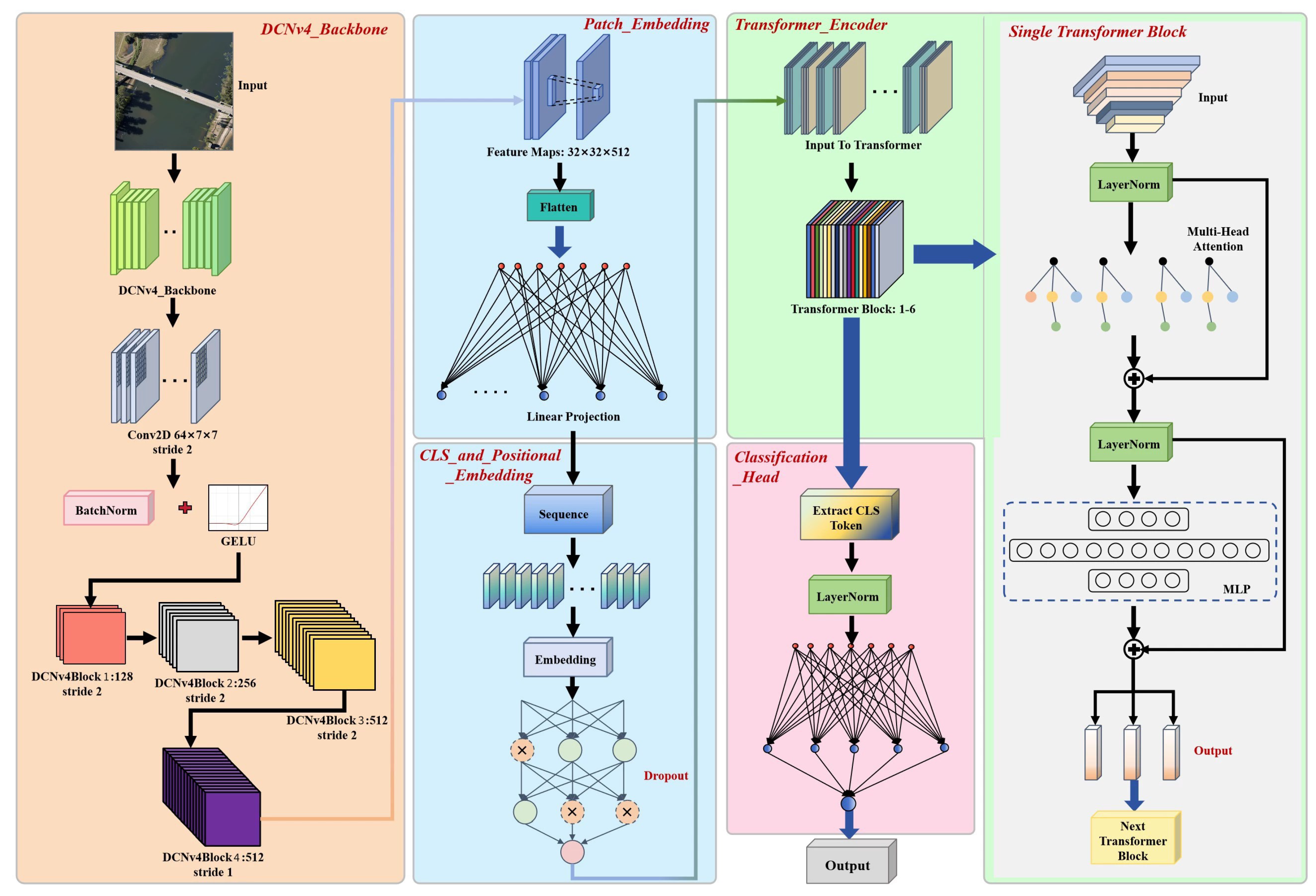

The overall architecture of the DViT Framework is shown in

Figure 3. The workflow can be clearly delineated into four distinct stages. Initially, the DCNv4 backbone extracts spatially-rich features from input remote sensing images, utilizing a sequence of DCNv4 residual blocks accompanied by batch normalization and GELU activation functions. Specifically, input images are progressively processed through convolutional and DCNv4 residual blocks to generate refined and representative feature maps. Subsequently, these feature maps undergo patch embedding, where they are flattened and linearly projected into a high-dimensional embedding space. Meanwhile, the model incorporates a learnable classification token (CLS) and positional embeddings, crucially preserving positional information and enabling the network to discriminate patches based on their spatial arrangement. These embeddings are then fed into the transformer encoder, consisting of several transformer blocks. Each transformer block comprises multi-head self-attention mechanisms and feed-forward neural networks with residual connections, effectively modeling inter-patch relationships. Lastly, the classification head extracts the output corresponding to the CLS token, normalizes it via layer normalization, and utilizes a fully-connected layer to predict the final classification labels.

The essence of DViT lies in its unique integration of adaptive convolutional processing and transformer-based global contextual understanding, clearly differentiating it from existing hybrid models such as RoadFormer [

41]. The main advantages of DViT can be summarized as follows:

DViT leverages the DCNv4 backbone’s powerful deformable convolution capability, dynamically adapting receptive fields to capture intricate spatial relationships effectively, thereby overcoming challenges like occlusions, rotations, and complex geometric distortions prevalent in remote sensing imagery.

The carefully designed transition from convolutional feature maps to transformer embeddings, incorporating positional and classification tokens, enhances the network’s sensitivity to spatial context and positional variance.

The use of a transformer encoder enables DViT to comprehensively model global interdependencies among image patches, addressing the limitations of convolution-only methods that typically neglect long-range interactions.

The extensive use of normalization and dropout layers within both convolutional and transformer modules significantly improves the training stability and generalization capacity of the model, ensuring robust performance across diverse remote sensing scenarios.

3. Results

3.1. Environment Setup

The experimental component of this study was conducted using Python version 3.12 and the PyTorch framework. The experiments were carried out on hardware equipped with NVIDIA RTX 4090 graphics cards. To ensure the reliability and stability of our findings, each model underwent ten separate experimental runs for comparison purposes. This approach allowed for a more comprehensive assessment of the models’ performance and stability across different experimental conditions.

3.2. Evaluation of Diffusion Framework

To assess the quality of the generated images, we employed two commonly used metrics, Kernel Inception Distance (KID) and Perceptual Image Distance (PID). The KID metric evaluates the distributional similarity between the features of the generated and original images, with lower values indicating closer similarity [

62]. For our evaluation, 30 randomly selected generated images were compared to their corresponding original images, resulting in an average KID score of 12.1, suggesting a reasonable alignment with the original data.

Additionally, the PID metric measures perceptual similarity, assessing how visually comparable the generated images are to the original ones [

63]. With a PID value of 0.67, our results indicate a high degree of perceptual similarity, although some perceptual discrepancies remain. While both metrics suggest room for improvement, the current strategy of the framework provides satisfactory results, demonstrating its capability in generating images of acceptable quality for remote sensing tasks.

3.3. Evaluation of Model Performances

This study evaluates the performance of various models, including FlashInternImage, Vision Transformer, and DViT, through metrics such as Overall Accuracy (OA), Mean Accuracy (mAcc), Kappa Coefficient, Precision (macro), Recall (macro), and F1-score (macro). These metrics provide comprehensive insights into model effectiveness for Landview Classification tasks.

Overall Accuracy (OA) quantifies the proportion of correctly classified instances across all classes and is computed as shown in Formula (1):

where TP, TN, FP, and FN represent true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively.

Mean Accuracy (mAcc) reflects the average classification accuracy across different classes, highlighting the balanced performance of models especially in datasets with class imbalance [

64]. The mAcc is computed using Formula (2):

where

N is the total number of classes.

The Cohen’s Kappa coefficient provides an evaluation of the model’s performance by considering agreement occurring by chance [

64]. It is calculated through Formula (3):

where

denotes the observed agreement and

represents the probability of random agreement.

Precision (macro) is calculated as the mean of class-wise precision, capturing the model’s accuracy in predicting each class correctly and reducing the impact of false positives [

65]. It is computed as shown in Formula (4):

Recall (macro), representing the average recall across all classes, indicates the model’s capability to identify all relevant instances per class, thereby accounting for false negatives. It is computed using Formula (5):

The F1-score (macro) harmonizes precision and recall into a single performance metric, providing a balanced measure that is particularly beneficial when precision and recall are equally critical [

65]. It is computed as illustrated in Formula (6):

These metrics collectively provide an in-depth evaluation, enabling a nuanced understanding of each model’s strengths and areas requiring improvement for effective Landview Classification.

3.3.1. Hyperparameters Setup

In this study, all models including Vision Transformer (ViT), FlashInternImage, and Deformable Vision Transformer (DViT) were trained for 50 epochs using a batch size of 8 and a learning rate initialized at

. The AdamW optimizer [

66] was employed to optimize the model parameters, providing improved weight decay handling and convergence stability during training. The input images were uniformly resized to a resolution of

pixels and normalized using mean and standard deviation values of

and

, respectively.

The network training was conducted by minimizing the Cross-Entropy Loss function, defined mathematically as:

where

N is the number of training samples in each batch,

C denotes the total number of classes,

represents the ground-truth indicator (with a value of 1 if the sample

i belongs to class

c and 0 otherwise), and

is the predicted probability of sample

i belonging to class

c.

Additionally, each model was configured with its respective specialized settings: the ViT and DViT models utilize transformer encoder layers with a dimensionality of 512, depth of 6 layers, and 8 attention heads, each head having a dimensionality of 64. The Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) dimension within the transformer was set to 1024. The dropout rate and embedding dropout were both set to 0.1 to prevent overfitting. For the FlashInternImage model, the DCNv4-based backbone architecture was configured with channel dimensions set at 64 and depth configuration of [4, 4, 18, 4]. The group numbers were assigned as [4, 8, 16, 32], and the offset scale was adjusted to 0.5, utilizing DCNv4 convolutional operations to effectively capture geometric variations within the images.

3.3.2. Result Analysis of Each Model

Table 1 illustrates the average values of performance metrics—OA, mAcc, Kappa coefficient, Precision, Recall, and F1-score—for three different models (ViT, FlashInternImage, and DViT) evaluated over 10 experimental runs. The results indicate that the DViT model consistently surpasses the ViT and FlashInternImage models across all metrics. Specifically, DViT achieves an OA of 0.9572, demonstrating a noticeable improvement of 2.13% compared to ViT (0.9359) and improvement of 2.59% compared to FlashInternImage (0.9313). Similarly, the mAcc of DViT (0.9568) surpasses ViT (0.9360) by 2.08% and FlashInternImage (0.9303) by 2.65%. The Kappa coefficient further underscores the superior performance of DViT, achieving 0.9465, surpassing ViT by 2.66% and FlashInternImage by up to 3.24%. Regarding Precision, Recall, and F1-score, DViT maintains a stable advantage with improvements of approximately 2.29%, 2.08%, and 2.18% respectively over ViT, and comparable margins over FlashInternImage, confirming the robust predictive capability and reliability of the DViT model.

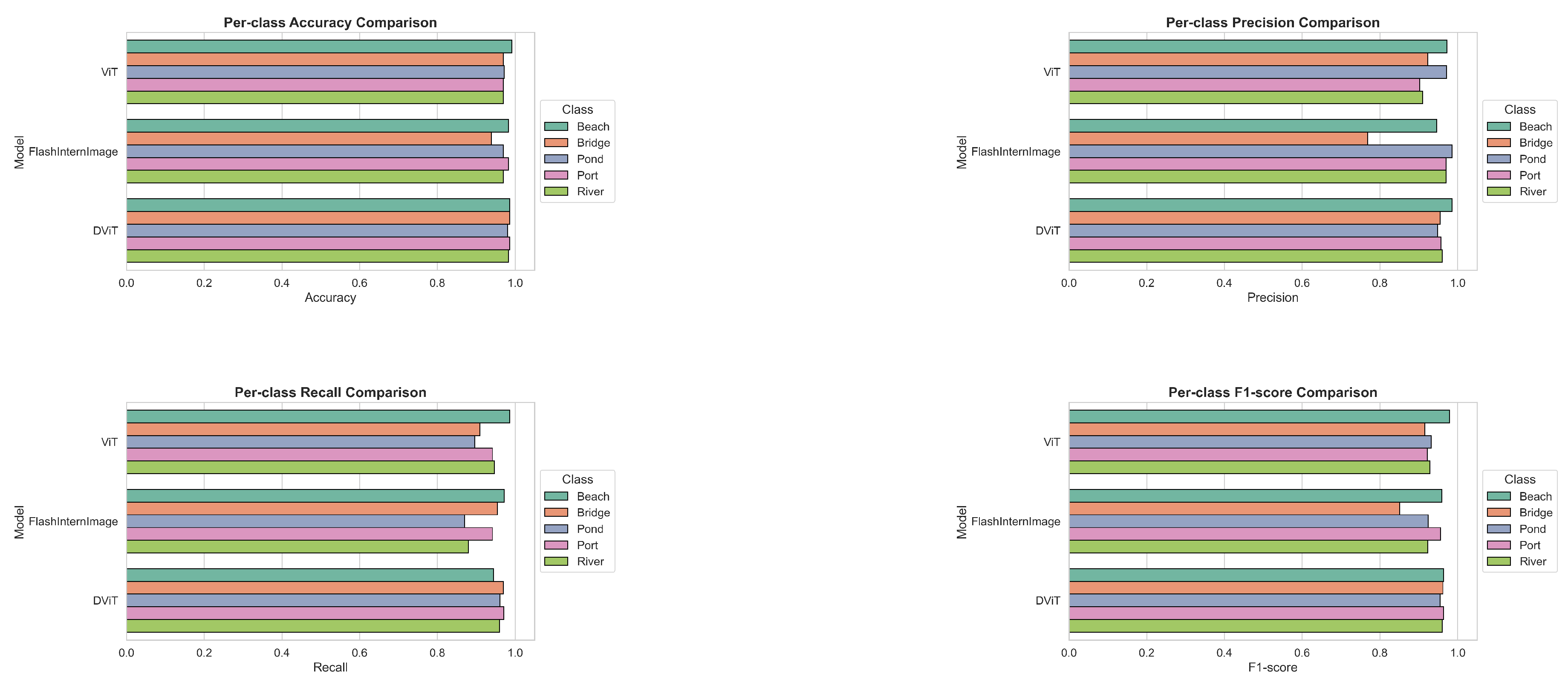

Figure 4 provides a detailed per-class comparison across five land-cover classes (Beach, Bridge, Pond, Port, and River) using four critical evaluation metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. In terms of

accuracy, DViT consistently demonstrates robust performance, achieving high accuracies for Bridge, Pond, Port, and River (all above 0.9805), notably surpassing FlashInternImage by significant margins, especially in the Bridge class (0.9861 vs. 0.9387, approximately 4.74% higher). However, ViT achieves the highest accuracy in the Beach class (0.9916), outperforming DViT (0.9861) and FlashInternImage (0.9833). Regarding

precision, DViT maintains strong performance, particularly for Bridge (0.9552), surpassing FlashInternImage (0.7683) by an extensive margin (approximately 18.69%), though ViT (0.9231) also performs relatively well. Conversely, FlashInternImage exhibits superior precision for the Pond (0.9853) and River (0.9706) classes, narrowly exceeding both DViT and ViT, indicating fewer false-positive errors. Examining

recall, DViT achieves the highest recall in Pond (0.9610), Port (0.9710), and River (0.9600), clearly surpassing FlashInternImage (River: 0.8800, Pond: 0.8701). FlashInternImage, however, achieves notably high recall in Bridge (0.9545), surpassing ViT (0.9091) and closely matching DViT (0.9697). ViT exhibits optimal recall for Beach (0.9861), indicating superior sensitivity for this class. Finally, considering the balanced metric of

F1-score, DViT again demonstrates strong overall performance, notably for Bridge (0.9624), Pond (0.9548), Port (0.9640), and River (0.9600), consistently outperforming both FlashInternImage and ViT, highlighting its effective balance between precision and recall. For the Beach class, ViT yields the highest F1-score (0.9793), indicating superior overall predictive performance compared to FlashInternImage (0.9589) and DViT (0.9645). Overall, while ViT and FlashInternImage each exhibit strengths in specific categories, the DViT model demonstrates consistently robust and balanced classification performance across most metrics and classes.

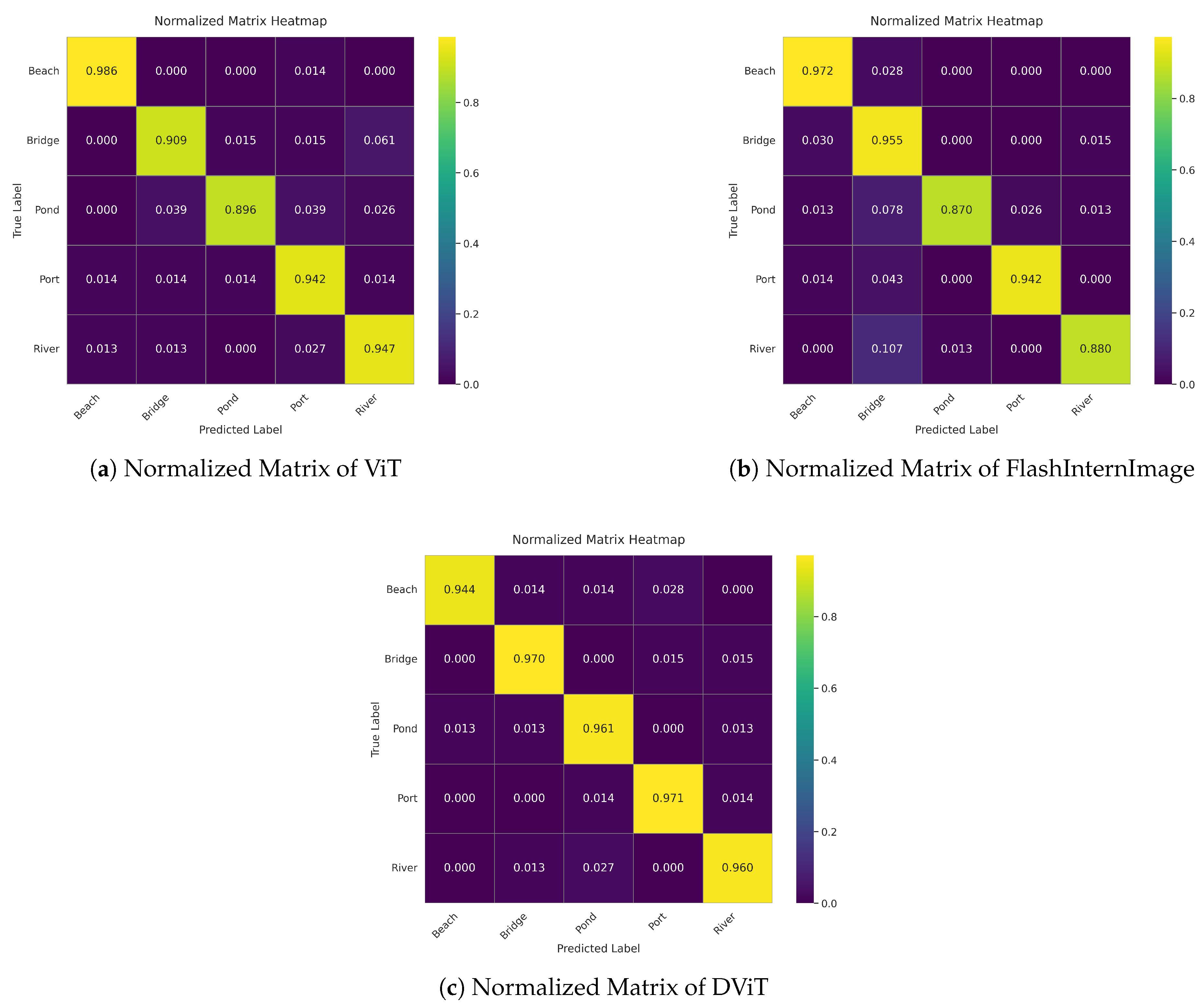

Figure 5 provides the confusion matrices of ViT, FlashInternImage, and DViT models, detailing their classification accuracy and misclassification patterns across five land-cover classes. The matrices demonstrate that the DViT model achieves superior classification accuracy for Bridge (64/66), Pond (74/77), Port (67/69), and River (72/75), outperforming both ViT and FlashInternImage. Specifically, for Bridge, DViT misclassifies only 2 samples compared to ViT’s 6. Similarly, for Pond, DViT misclassifies only 3 samples, fewer than ViT’s 8 and FlashInternImage’s 10. Regarding Port and River, DViT also demonstrates fewer errors (Port: 2 errors, River: 3 errors) compared to ViT (Port: 4 errors, River: 4 errors) and FlashInternImage (Port: 4 errors, River: 9 errors). However, for the Beach class, ViT (71/72) and FlashInternImage (70/72) both outperform DViT (68/72), highlighting DViT’s relatively weaker performance, with 4 misclassifications compared to ViT’s 1 and FlashInternImage’s 2. These comparisons underscore DViT’s overall superior accuracy while suggesting potential improvements for the Beach category classification.

Figure 6 also provides the normalized matrices of the ViT, FlashInternImage, and DViT models, clearly highlighting variations in per-class prediction accuracy. The DViT model consistently achieves higher diagonal values across classes, particularly excelling in correctly identifying "Bridge" (0.970), "Port" (0.971), and "Pond" (0.96), surpassing FlashInternImage (Bridge: 0.955; Port: 0.942; Pond: 0.870) and ViT (Bridge: 0.909; Port: 0.942; Pond: 0.896). FlashInternImage shows notable misclassification in the "River" class, with only 0.880 accuracy and a significant confusion rate (0.107) in mispredicting it as "Bridge." However, ViT achieves superior accuracy in classifying "Beach" (0.986), outperforming both FlashInternImage (0.972) and DViT (0.944), reflecting better robustness in this specific category. Overall, the normalized matrices reveal that DViT offers more balanced and stable classification performance, minimizing inter-class confusion compared to ViT and FlashInternImage.

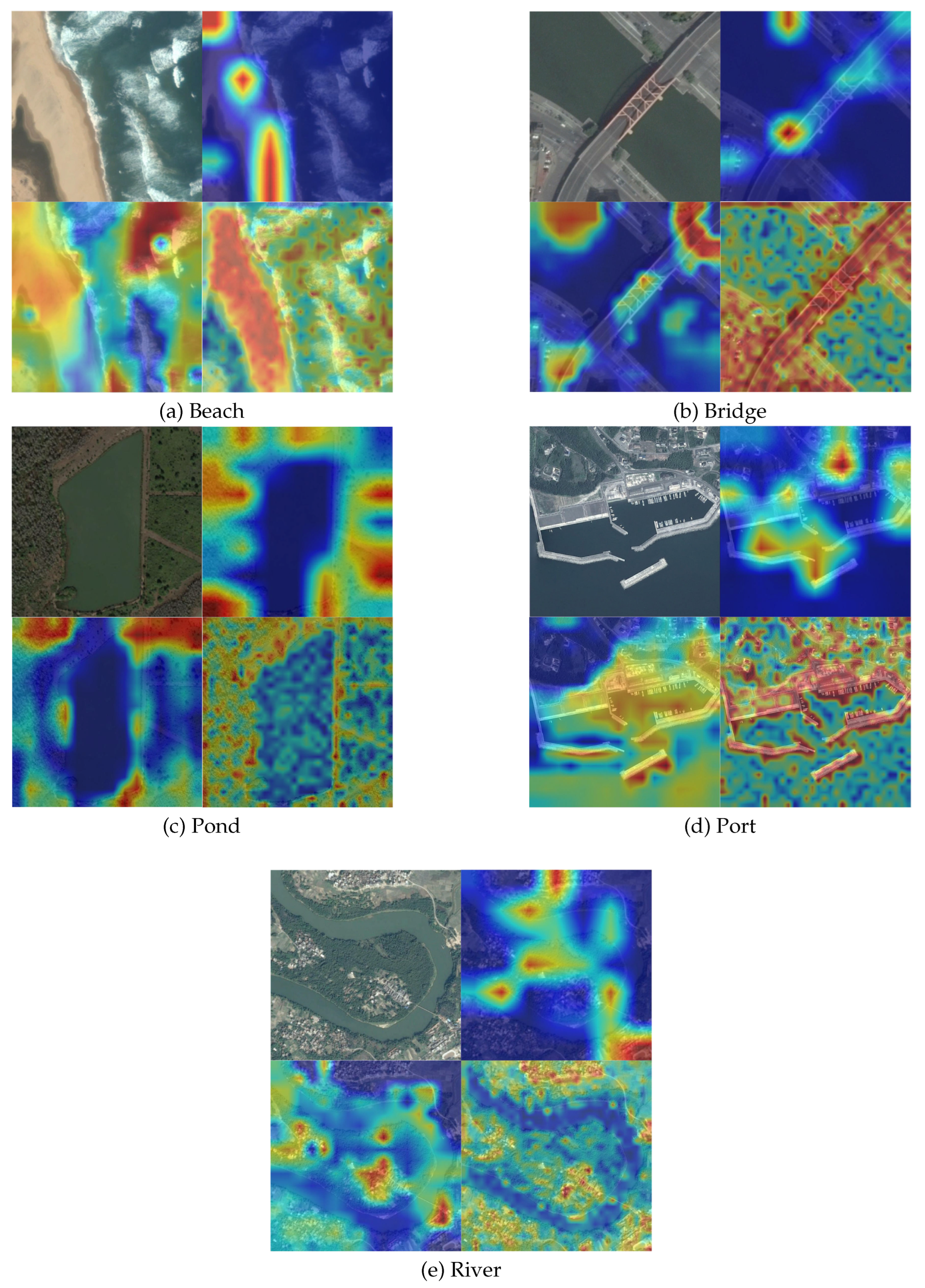

3.4. Visualization of Model Attention via Heatmap

To gain deeper insight into the regions influencing the classification decisions of the model, heatmaps were generated to illustrate the spatial attention on input images. Specifically, Class Activation Mapping (CAM) and Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) techniques were employed [

67]. A hook is registered at the final convolutional layer to collect the gradients, which are then applied to the layer’s output to produce activation maps. These activation maps are subsequently weighted to highlight regions significantly influencing classification decisions, enabling clear visualization of the model’s decision rationale.

The resulting heatmaps for five distinct classes—Beach, Bridge, Pond, Port, and River—are illustrated in

Figure 7. Overall, the models primarily attend to essential structural or boundary features relevant to each class, yet exhibit slight differences in attention patterns. In the Beach category, all three models—ViT, FlashInternImage, and DViT—mainly focus on shoreline boundaries and wave formations, with DViT showing slightly more precise boundary delineation. For Bridge imagery, structural components such as bridge spans and pillars are prominently highlighted by all models, though ViT and DViT provide comparatively sharper attention than FlashInternImage. Pond images show consistent attention along water boundaries; here, DViT and ViT demonstrate clearer edge localization relative to FlashInternImage’s broader attention coverage. For Port imagery, models collectively emphasize dock structures and harbor edges, with DViT slightly enhancing the spatial coherence of infrastructure features. Finally, in the River class, attention closely follows the river course, and while all models successfully identify spatial continuity, DViT presents a marginally more focused tracing of the watercourse. These visualizations collectively illustrate the robust yet nuanced approaches of ViT, FlashInternImage, and DViT in localizing discriminative image features.

4. Discussion

The proposed LVC2-DViT framework demonstrates that coupling class-balanced, description-driven diffusion sampling with a deformation-aware Vision Transformer can raise land-cover mapping accuracy by more than two percentage points over state-of-the-art baselines while leaving model capacity unchanged. By injecting high-fidelity synthetic imagery that faithfully represents elongated coastlines, bridges, and riverine structures, and by replacing rigid convolutional kernels with DCNv4 enabled adaptive receptive fields [

54,

56], our approach mitigates both class imbalance and geometric distortion - two longstanding obstacles in high-resolution remote sensing. Nevertheless, two practical constraints remain. First, evaluation was confined to five scene types in the AID corpus; although these classes typify hydrological environments, broader validation on additional sensors, spectral bands and disturbance regimes is still required. Second, despite perceptual gating, the average KID (12.1) and PID (0.67) reveal a residual fidelity gap between synthetic and real imagery, most visible in the Beach category. These caveats do not compromise the principal finding, that integrating diffusion augmentation with deformable attention yields measurable gains, but they do motivate future work.

In particular, in the future study, we plan to (i) extend LVC2-DViT to multi-spectral and multi-sensor datasets such as Sentinel-2 and Gaofen-6, (ii) fine-tune the diffusion backbone with in-domain aerial imagery to reduce KID/PID further, and (iii) explore lightweight deformable self-attention blocks and semi-supervised domain adaptation to cut training cost and enhance cross-region generalisation.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes LVC2-DViT, an end-to-end framework that synergistically combines two core innovations to advance remote sensing land-use classification. Firstly, a generative data augmentation pipeline leverages ChatGPT-4o’s textual scene descriptions and Stable Diffusion (enhanced by ControlNet-guided geometric fidelity) to synthesize class-balanced, high-fidelity training imagery, effectively mitigating data scarcity. Secondly, a DViT classifier integrates DCNv4’s adaptive receptive fields with Vision Transformer’s global context modeling, robustly capturing irregular landform geometries like meandering rivers and fragmented shorelines. Evaluated on five AID land-cover classes, LVC2-DViT achieves a 2.13 percentage higher Overall Accuracy and 2.66 percentage higher Cohen’s Kappa versus a strong ViT baseline, while also surpassing FlashInternImage. This demonstrates its significant contribution to accurate environmental monitoring and land planning by concurrently resolving data limitations and geometric distortion challenges in remote sensing. Furthermore, it provides critical technical support for ecological conservation, enabling precise assessment and protection of vulnerable hydrological ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., K.W., S.C. and W.P.; methodology, C.L., K.W., S.C. and W.P.; software, K.W., S.C., W.P. and C.L.; validation, K.W., S.C., W.P. and Z.C.; formal analysis, C.L.; investigation, K.W., S.C. and W.P.; resources, C.S., K.W., W.P., C.L. and Z.C.; data curation, W.P., K.W., S.C., C.L. and Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L., K.W., S.C. and W.P.; writing—review and editing, K.W., S.C., W.P., C.L., and Z.C.; visualization, K.W., S.C., W.P., C.L., and Z.C.; supervision, C.L., K.W.; project administration, C.L., K.W.; funding acquisition, K.W., S.C., W.P., C.L., and Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the AID Dataset team from Wuhan University for open-sourcing the AID dataset.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Musetsho, K. D.; Chitakira, M.; Ramoelo, A. Ecosystem service valuation for a critical biodiversity area: Case of the Mphaphuli community, South Africa. Land, 11, 1696, 2022.

- Chen, H.; Cai, W. Multi-scale analysis of water purification ecosystem service flow in Taihu basin for land management and ecological compensation. Land, 13, 1694, 2024.

- Li, C.; Cui, H.; Tian, X. Remote Sensing Image Segmentation of Wetlands in Macau Based on Machine Learning. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 2665, 2023. 2023 International Conference on Big Data, Information and Intelligent Engineering, Wuhan, China, 17–18 September.

- Zhou, W.; Wu, T.; Tao, X. Exploring the spatial and seasonal heterogeneity of the cooling effect of an urban river on a landscape scale. Scientific Reports, 14, 8327, 2024.

- Allain, B.S.; Marechal, C.; Pottier, C. Wetland Water Segmentation Using Multi-Angle and Polarimetric Radarsat-2 Datasets. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Munich, Germany, 22–27 July 2012; pp. 4915–4917. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Z.Y.; Ru, A.; Li, X.J. ANN Based High Spatial Resolution Remote Sensing Wetland Classification. In Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Distributed Computing and Applications for Business Engineering and Science (DCABES), Guiyang, China, 18–24 August 2015; pp. 180–183. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, Y.; Li, W.; Xia, X.G.; Tao, R.; Yue, A. Infrared Attention Network for Woodland Segmentation Using Multispectral Satellite Images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 60, 2022, p. 5627214.

- Cui, H.; Liang, J.; Li, C.; Tian, X. Improved Convolutional Neural Network with Attention Mechanisms for River Extraction. Water, vol. 17, no. 12, 2025, p. 1762.

- Mashala, M. J.; Dube, T.; Mudereri, B. T.; Ayisi, K. K.; Ramudzuli, M. R. A systematic review on advancements in remote sensing for assessing and monitoring land use and land cover changes impacts on surface water resources in semi-arid tropical environments. Remote Sens., 15, 3926, 2023.

- Li, C.; Cui, H.; Tian, X. A Novel CA-RegNet Model for Macau Wetlands Auto Segmentation Based on GF-2 Remote Sensing Images. Appl. Sci., 13, 12178, 2023.

- Lupa, M.; Pełka, A.; Młynarczuk, M.; Staszel, J.; Adamek, K. Why rivers disappear—Remote sensing analysis of post-mining factors using the example of the Sztoła River, Poland. Remote Sens., 16, 111, 2024.

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 6840–6851, 2020.

- Song, Y.; Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Kingma, D.P.; Kumar, A.; Ermon, S.; Poole, B. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. arXiv:2011.13456, 2020.

- Li, C.; Zhou, K.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, M.; Gao, H.; Jin, B.; Zhao, H. AVD2: Accident video diffusion for accident video description. arXiv:2502.14801, 2025.

- Xu, T.; Zhang, P.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Gan, Z.; Huang, X.; He, X. AttnGAN: Fine-grained text-to-image generation with attentional GANs. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1316–1324, 2018.

- Ruan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Fan, Y.; Tang, F.; Liu, Q.; Chen, E. DAE-GAN: Dynamic aspect-aware GAN for text-to-image synthesis. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 13960–13969, 2021.

- Zhao, R.; Shi, Z. Text-to-remote-sensing-image generation with structured generative adversarial networks. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 19, 1–5, 2021.

- Tao, M.; Tang, H.; Wu, F.; Jing, X.Y.; Bao, B.K.; Xu, C. DF-GAN: A simple and effective baseline for text-to-image synthesis. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 16515–16525, 2022.

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, R.; Chen, C.; Li, C.; Tensmeyer, C.; Yu, T.; Gu, J.; Xu, J.; Sun, T. Towards language-free training for text-to-image generation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 17907–17917, 2022.

- Nichol, A.; Dhariwal, P.; Ramesh, A.; Shyam, P.; Mishkin, P.; McGrew, B.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, M. GLIDE: Towards photorealistic image generation and editing with text-guided diffusion models. arXiv:2112.10741, 2021.

- Sebaq, A.; ElHelw, M. RSDiff: Remote-sensing image generation from text using diffusion model. arXiv:2309.02455, 2023.

- Baghirli, O.; Askarov, H.; Ibrahimli, I.; Bakhishov, I.; Nabiyev, N. SatDM: Synthesizing realistic satellite images with semantic-layout conditioning using diffusion models. arXiv:2309.16812, 2023.

- Khanna, S.; Liu, P.; Zhou, L.; Meng, C.; Rombach, R.; Burke, M.; Lobell, D.; Ermon, S. DiffusionSat: A generative foundation model for satellite imagery. arXiv:2312.03606, 2023.

- Tang, D.; Cao, X.; Hou, X.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, J.; and Meng, D. CRS-Diff: Controllable remote sensing image generation with diffusion model. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 1–14, 2024.

- De Vita, M.; Belagiannis, V. Diffusion model guided sampling with pixel-wise aleatoric uncertainty estimation. arXiv:2412.00205, 2024.

- Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Cui, J. Have we unified image generation and understanding yet? An empirical study of GPT-4o’s image generation ability. arXiv:2504.08003, 2025.

- Tzepkenlis, A.; Marthoglou, K.; Grammalidis, N. Efficient Deep Semantic Segmentation for Land Cover Classification Using Sentinel Imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmanis, D.; Datcu, M.; Esch, T.; Stilla, U. Deep Learning Earth Observation Classification Using ImageNet Pre-trained Networks. IEEE GRSL 13(1):105-109, 2016.

- Li, C.; Chen, S.; Ma, Y.; Song, M.; Tian, X.; Cui, H. Wheat Pest Identification Based on Deep Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the IEEE 7th International Conference on Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (BDAI), Beijing, China; 2024; pp. 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Tian, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhai, Y.; Cui, H.; Song, M. An Advancing GCT-Inception-ResNet-V3 Model for Arboreal Pest Identification. Agronomy 2024, 14, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G. -S.; Hu, J., Hu, F., Eds.; et al. AID: A Benchmark Dataset for Performance Evaluation of Aerial Scene Classification. IEEE TGRS 55(7):3965-3981, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, S.; Yang, S.; Zheng, Y. et al. A Hybrid Brain-Computer Interface based Wearable Exoskeleton System for Fine-Grained Hand Rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), Xi’an, China; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Li, C.; Ma, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhu, J.; Tian, X. Deep Learning Techniques for Lunar Impact Crater Identification Based on CCD and DEM Data. In: Deligiannidis, L.; Ghareh Mohammadi, F.; Shenavarmasouleh, F.; Amirian, S.; Arabnia, H.R. (eds) Image Processing, Computer Vision, and Pattern Recognition and Information and Knowledge Engineering. CSCE 2024. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 2262. Springer, Cham, 2025.

- Vali, A.; Comai, S.; Matteucci, M. Deep Learning for Large-Scale Image Classification of High-Resolution Aerial Imagery. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 34(14):1177-1196, 2020.

- Khan, S.; Khan, M.; Rauf, A.; et al. Remote Sensing Image Classification: A Comprehensive Review and Possible Future Directions. Artificial Intelligence Review, 2022.

- Zhu, X.; et al. A Survey of Remote Sensing Image Classification Based on CNNs. Geo-spatial Information Science 26(1):67-95, 2019.

- Wang, K.; Lu, S.; Jiang, S. Unseen Obstacle Detection via Monocular Camera Against Speed Change and Background Noise. In: HCI International 2023 – Late Breaking Papers: 25th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, HCII 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark, –28, 2023, Proceedings, Part IV. Springer, 2023. 23 July.

- Khan, M.; Hanan, A.; Gazzea, M.; et al. Transformer-Based Land Use and Land Cover Classification with Explainability Using Satellite Imagery. Scientific Reports 14, 16744, 2024.

- Xiao, P.; Sun, F.; Wang, K.; Xiao, K.; Shang, X.; Liu, J. Positioning Performance Analysis of Real-Time BDS-3 PPP B2b/INS Tightly Coupled Integration in Urban Environments. Advances in Space Research, Volume 72, Issue 9, 2023, Pages 4008–4020.

- Han, S.; Zhao, M.; Wang, K.; Dong, J.; Su, A. Cross-Modal Images Matching Based Enhancement to MEMS INS for UAV Navigation in GNSS Denied Environments. Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 14, 2023, p. 8238.

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; et al. RoadFormer: Pyramidal Deformable Vision Transformers for Road Network Extraction with Remote Sensing Images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens., 2022.

- Naushad, R.; Kaur, T.; Ghaderpour, E. Deep Transfer Learning for Land Use and Land Cover Classification: A Comparative Study. Sensors 21(23):8083, 2021.

- Alosaimi, N.; Alhichri, H.; Bazi, Y.; et al. Self-Supervised Learning for Remote Sensing Scene Classification under the Few-Shot Scenario. Scientific Reports 13, 433, 2023.

- Scheibenreif, L.; Hanna, J.; Mommert, M.; Borth, D. Self-Supervised Vision Transformers for Land-Cover Segmentation and Classification. In CVPR EarthVision Workshop, 2022.

- Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Dong, C.; Shan, Y. RealESRGAN: Training Real-World Blind Super-Resolution with Pure Synthetic Data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021; pp. 1905–1914. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhang, R.; Park, J.; Shechtman, E.; Paris, S.; Park, T. Scaling Up GANs for Text-to-Image Synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023; pp. 10124–10134. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 1069; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, R.; Thakur, S.; Khurana, R. Satellite imagery augmentation using latent diffusion for improved classification performance. Remote Sensing, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09685, arXiv:2106.09685, 2022.

- Zhang, L.; Agrawala, M. Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 3847. [Google Scholar]

- Toker, A.; Kaplan, H.; Aksoy, S. Diffusion-based data augmentation for remote sensing image segmentation. Remote Sensing, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; Xu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Q. Controlled diffusion models for realistic aerial image generation. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Xi. ; Luo, Jia.; Wang, W. Efficient Deformable ConvNets: Rethinking Dynamic and Sparse Operator for Vision Applications. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Sang, L. DCNv3: Towards Next Generation Deep Cross Network for CTR Prediction. In CoRR, 2024, vol. abs/2407.13349. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Xia, Y.; Li, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, X.; Dai, J. InternImage: Exploring Large-Scale Vision Foundation Models with Deformable Convolutions. arXiv:2211.05778, 2022.

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2014; pp. 740–755.

- Zhou, B.; Zhao, H.; Puig, X.; Fidler, S.; Barriuso, A.; Torralba, A. Scene Parsing through ADE20K Dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017; pp. 633–641. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; <i></i>., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. An Image Is Worth 16×16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv:2010.11929, 2020.

- Chen, S.; Liang, J.; Zhu, J.; Tian, X. New Methods for Lunar Impact Crater Detection Based on YOLO v7 with Deformable ConvNets. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Electrical, Automation and Computer Engineering (ICEACE), Changchun, China; 2023; pp. 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bińkowski, M.; Letcher, A.; Kumar, A.; Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Kwiatkowski, T.; Szepesvári, C. Demystifying MMD GANs. arXiv:1801.01401, 2018.

- Li, A.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y. PID: Prompt-independent Data Protection Against Latent Diffusion Models. arXiv:2406.15305, 2024.

- Hu, J.; Mou, L.; and Zhu, X. X. Unsupervised domain adaptation using a teacher–student network for cross-city classification of Sentinel-2 images. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLIII-B2-2020, 1569–1574, 2020.

- Powers, D. M. W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv:2010.16061, 2020.

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101, arXiv:1711.05101, 2017.

- Zhang, Y.C.; Gao, J.P.; Zhou, H.L. Breeds Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computing, Shenzhen, China, 19–21 June 2020; pp. 145–151. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).