1. Introduction

One of the main problems faced by the Standard Model of Cosmology is the origin of spacetime through a big bang singularity. The existence of this singularity in the solutions to Einstein’s equations, when applied to cosmological models, highlights the importance of seeking a quantum gravity theory to eliminate it. Since the early Universe had dimensions much smaller than atomic nuclei, it is valid to suggest that it was governed by the laws of quantum mechanics. The first attempt to find a quantum gravity theory was the quantization of General Relativity, which gave rise to the Wheeler-DeWitt equation [

1,

2]. The application of this quantum theory to cosmology produced Quantum Cosmology (QC) [

3]. Although it is widely accepted that QC is not the fundamental theory for describing the very early universe, many important results have already been obtained from the study of QC models. One of such results is the birth of the universe through a quantum tunneling process. Due to that process, it is possible to show that the universe may originate without the big bang singularity [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

In the literature, there are many works using the quantum tunneling process in different quantum cosmology models [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. In addition to the investigation of the quantum tunneling process, we may find several other recent works on different aspects of QC. In [

22], the authors discuss the time in QC. It is shown that the reparametrization invariance is not guaranteed after one quantizes the model. Reference [

23] shows a different quantization process, where the authors use what they call a "super field" consisting of the union of the spacetime wavefunction and the matter fields. The authors of [

24] study how a form of dark energy called "phantom energy" affects the wavefunction of the universe which is a solution to the appropriate Wheeler-DeWitt equation. One of the most important results is that the higher the energy content in the model, the greater the probability that the universe will be born with a determined size, avoiding the initial singularity in

. References [

25,

26,

27] bring a novel approach in which the authors try to use fractional calculus in QC. In [

28] the author reviews the DeBroglie-Bohm quantum theory. This is a theory that dispenses with the collapse of the wavefunction and, therefore, is quite appropriate to be applied to QC. In [

29] the authors also address the issue of time not being an exactly defined notion in QC and present two solutions with applications focused on QC. In reference [

30] the authors employ the fractional Riesz derivative in the Wheeler-DeWitt equation for a closed de Sitter geometry. The authors of [

31] study a quantum cosmology model using electromagnetic radiation as a matter content. Reference [

32] presents the first study of QC using quantum computers. There, the authors solve a Wheeler-DeWitt equation and show that the use of quantum computers allows one to reach solutions with a high degree of precision. In reference [

33] the authors explore a two-dimensional cosmological model of quantum gravity. They do it, initially, by writing the classical sector with the aid of the ADM formalism, and then they solve the Wheeler-Dewitt equation in order to describe the quantum sector. In [

34] the authors study approximate solutions to the Wheeler-DeWitt equation and compare the results with cosmological perturbative theories. In the work [

35], the author works on the quantization of quantum cosmology models, introducing the concepts of mini-superspace, perfect fluids, and scalar fields, bringing up conceptual problems such as the evolution of time and unitarity, as well as physical interpretations. These are some examples showing that Quantum Cosmology is an active field and grows over time.

Since the seminal work by P. A. M. Dirac in 1937 [

36] arguing about the possibility that some of the fundamental constants of nature may vary with the age of the Universe, many works have been done exploring that possibility. Although not mentioned in Dirac’s work, the cosmological constant (CC) is today a very important constant of nature because it is a possible candidate to explain the present accelerated expansion of our Universe [

37,

38]. Some recent observational evidence shows that the expansion of the universe accelerated faster in the past than it is doing now[

39]. This opens up the possibility, among others, for a running CC. In fact, even before this recent observational evidence, several researchers have already considered the possibility of a running CC [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. A promising line of investigation of a running CC is based on the study, using quantum field theory in curved spacetime, of the renormalization group (RG) [

45,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. In the RG method, the equation of state for the cosmological constant is exactly given by

and the CC becomes time dependent. Also, using the RG method it is possible, with the aid of some cosmological observations, to impose phenomenological limits on a certain parameter of the method [

51,

53]. It certainly improves the predictions of this method.

In this work, we want to study the Universe in its early stages through quantum cosmology. For this purpose, the tunneling probabilities for the emergence of the Universe through a potential barrier are calculated. We do that with the help of the solutions to the Wheeler-DeWitt equation obtained in two different ways: the numerical solution and the WKB approximation. The Universe is described by a Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) model with positive curvature of the spatial sections, coupled to a dust perfect fluid and a running cosmological constant, described by the RG method. The latter is introduced to describe the dark energy present in the Universe.

In

Section 2, we derive the total Hamiltonian, draw a phase portrait, and solve the Hamilton equations for a FLRW cosmological model, with constant positive spatial sections and coupled to a dust perfect fluid and a running cosmological constant. In

Section 3, we quantize the model and solve the resulting Wheeler-DeWitt equation, using a numerical method and the WKB approximation. In

Section 4, we compute the WKB (

) and the integrated (

) tunneling probabilities for the universe to tunnel through the potential barrier. We investigate how

and

depend on several parameters of the model. Finally, in

Section 5, we summarize the main points and results of the paper. In

Appendix A, we compute in detail, with the aid of the Schutz variational formalism, the total Hamiltonian for the dust fluid.

2. The Classical Model

The classical cosmology, based on the FLRW model, has its foundations in Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (GR) [

54], accurately elucidating large-scale phenomena such as black holes, gravitational waves, light deflection, and the precession of Mercury’s orbit. Objectively, in this section, the ADM formalism [

55,

56] was used to derive the Hamiltonian density of GR, thus making possible to quantize it.

The action integral, written in terms of the matter Lagrangian density (

) and the Ricci scalar (

R), is given by,

Where

g is the determinant of the metric,

is defined as the sum of the contributions from the time-varying CC,

(where

is the pressure associated to the time-varying CC), and the perfect fluid

(where

is the pressure associated to the fluid). In this work, the following system of units is used:

.

If we introduce the values of

R and

, computed for the FLRW metric with positively curved spatial sections, in Equation (

1) we obtain,

where

is the scale factor,

is the lapse function,

is the time-varying CC energy density (we used that

),

is the fluid energy density,

is a constant associated with the fluid Equation (

A5), the dot means derivative with respect to time and

is defined as,

The running cosmological constant energy density,

has the following expression [

45,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52],

where

represents the vacuum energy density at present time,

H is the Hubble function defined as

,

is a constant that gives the Hubble function at the present time, and the parameter

is a dimensionless constant that emerges from the renormalization process and characterizes the magnitude of quantum effects on the vacuum energy density. It is defined as,

where

represents the predominance of bosons (

) or fermions (

) at high energies,

M is a weighted sum of the effective masses of massive virtual particles and

is the Planck mass (

). Since

, the parameter

is typically very small, of the order of

[

51,

53]. This value reflects the low quantum contribution relative to the total gravitational energy. However, studies suggest that in the early Universe, during a highly anisotropic and dynamic phase, the usual limitations on the sign and magnitude of

may not apply. In such conditions,

could assume much larger values (both positive and negative). This occurs because spacetime conditions are dominated by intense quantum effects and high-energy interactions that influence vacuum dynamics [

52]. This behavior enables exploration of cases where the values of

directly impact the isotropization process and the evolution of the metric [

52]. The parameter

also regulates the temporal variation of the vacuum energy density.

Introducing the value of

Equation (

4) in the action Equation (

2), we find,

From action (

6) one extracts the following Lagrangian density,

for simplicity, we will consider

.

Now we can compute the canonical momentum,

Introducing

Equation (

8) into the Hamiltonian density definition,

and using the Schutz formalism [

57], in order to determine the Hamiltonian of the matter sector (see

Appendix A for more details), one obtains,

where

. To avoid factor ordering ambiguities, one must use the following change of variables [

58],

Choosing the gauge

, the Hamiltonian density becomes,

Using the constraint equation

one identifies the potential

,

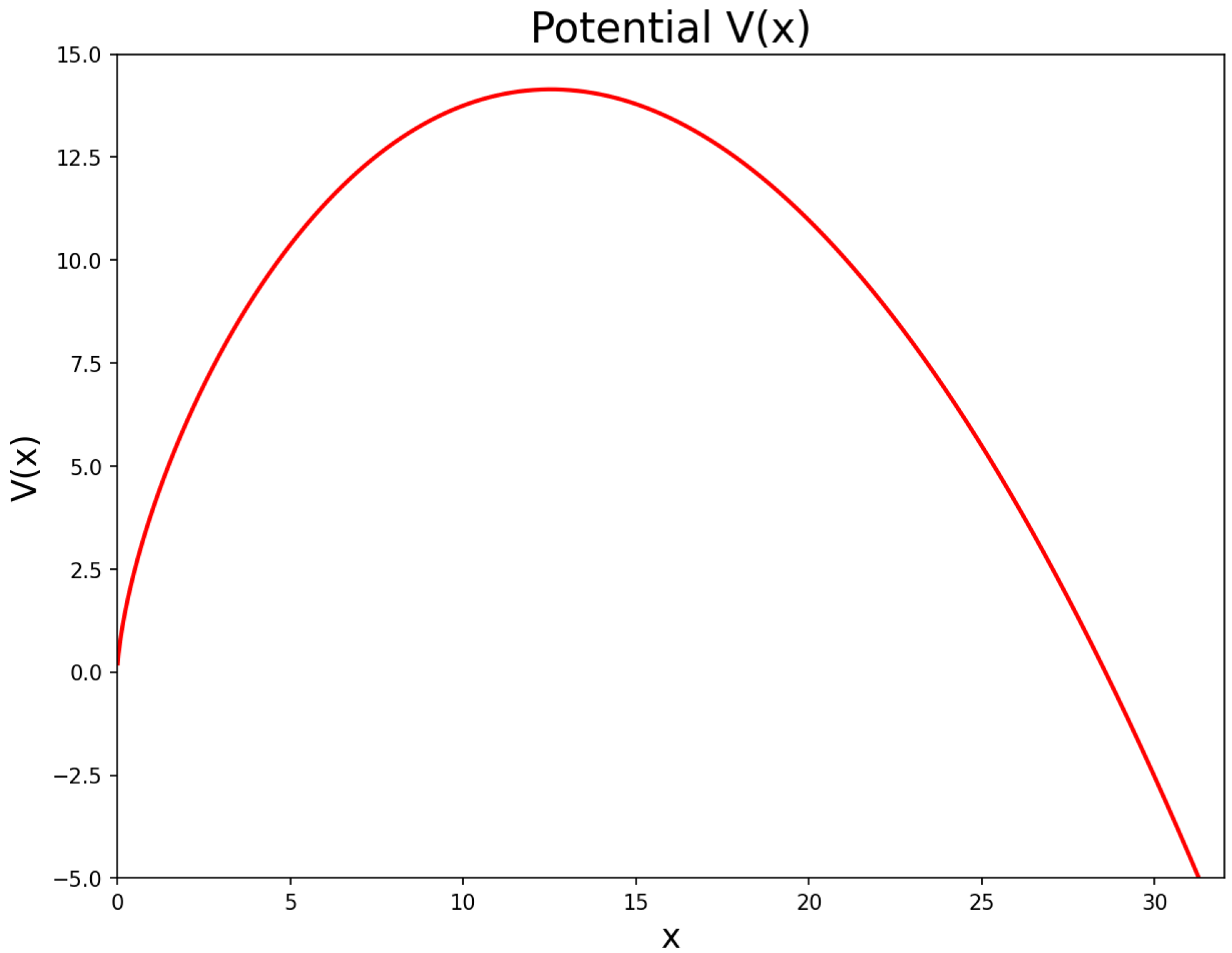

which has the shape of a barrier. In

Figure 1, we show an example of

Equation (

12), for

,

and

. In this example, the maximum value of

(

) is 14.1421.

The classical dynamics is governed by the Hamilton equations,

So, now one may impose the constraint equation

leading to an equation for the momentum

given by,

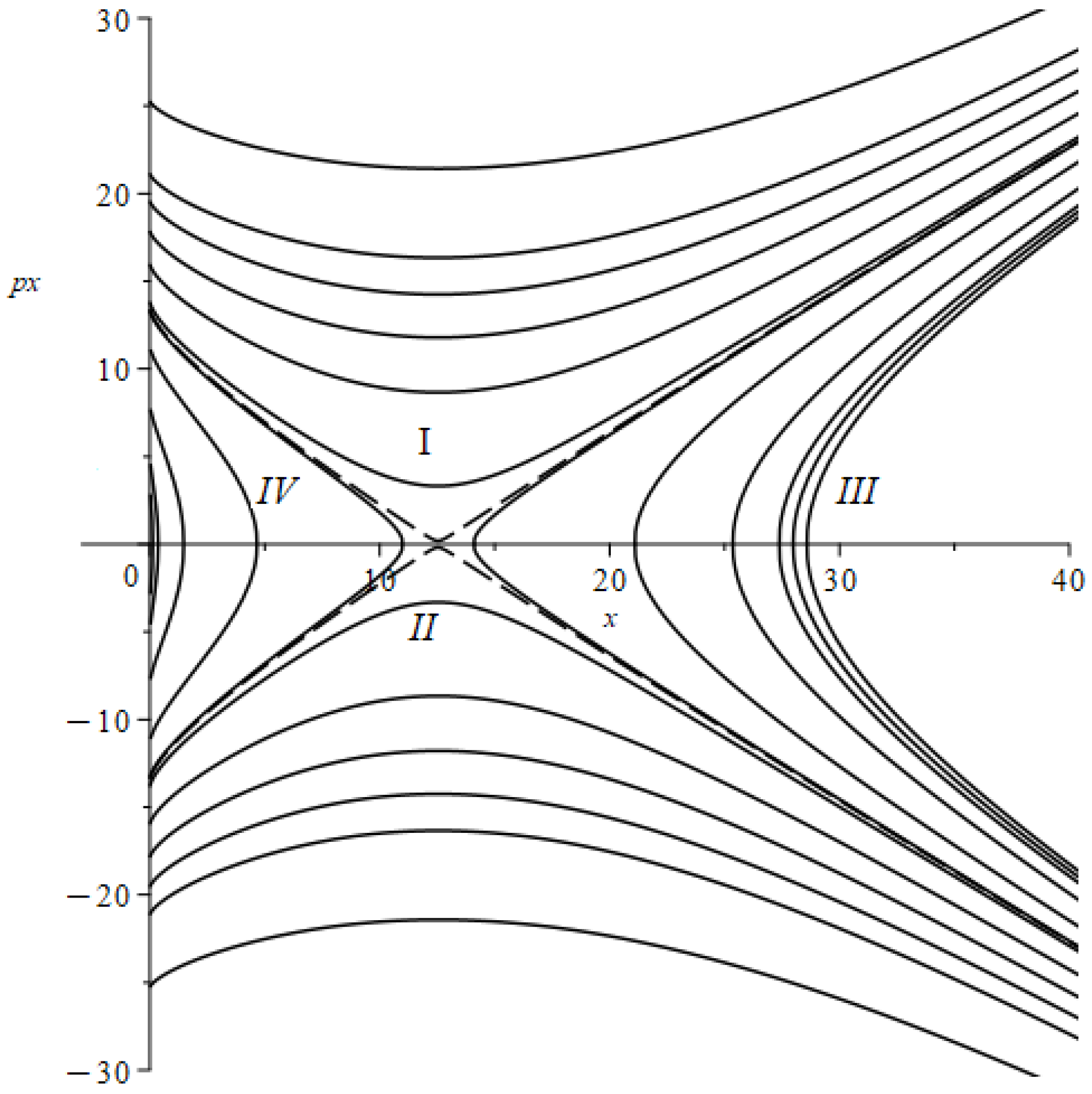

We begin studying the dynamics produced by Hamilton equations by constructing the phase portrait of the current model, which is shown in

Figure 2. The curves are labeled according to the parameter

, which takes the values

, 1, 2, 5, 10, 14,

, 15, 20, 25, …, 200, 250, 300. The phase portrait gives a general idea of all different types of dynamical solutions of the model. As we shall see next, all different types of dynamical solutions can be associated with the four regions identified in the phase portrait

Figure 2.

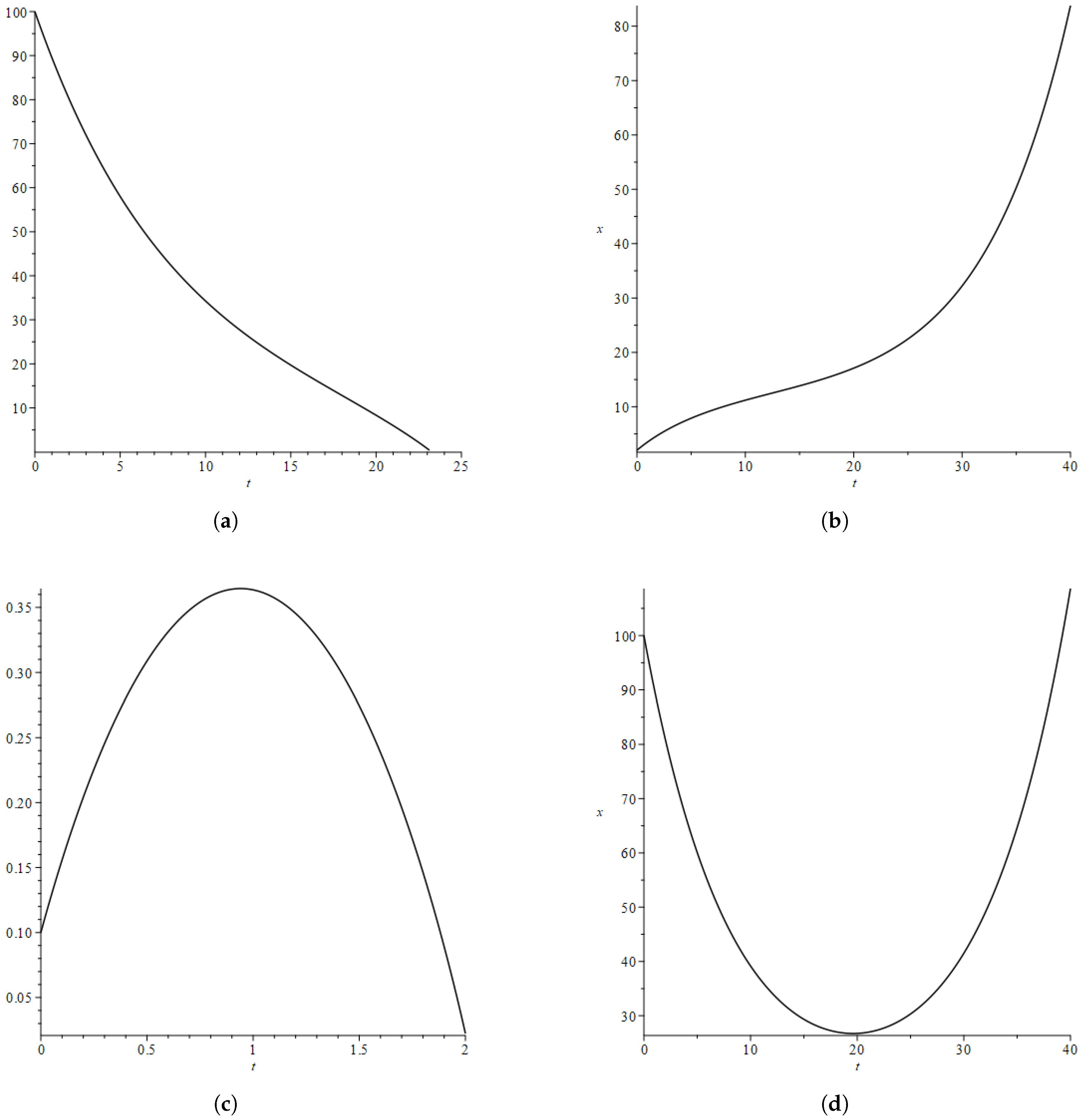

After combining some of the Hamilton equations from Equation (13), one can obtain a second-order differential equation for the classical evolution of the scale factor,

When solving Equation (

15), with the appropriate initial conditions, four different types of classical solutions are found pictured in

Figure 3a,d. These solutions are: (i) A contraction solution which has

x starting at a high value and decreasing until it reaches

, which produces a big crunch singularity. This solution can be seen in

Figure 3a. For this particular example, the initial conditions were

and

. These types of solutions are located in Region II of

Figure 2; (ii) An expansion solution where

x begins at small values and starts an expansion at an accelerated rate to infinity. This solution can be seen in

Figure 3b. For this particular example, the initial conditions were

and

. These types of solution are located in Region I of

Figure 2; (iii) An expansion followed by a contraction solution in which

x begins at small values and grows until it reaches a maximum value. Then it begins to shrink until it reaches

, which produces a big crunch singularity. This solution is shown in

Figure 3c. For this particular example, the initial conditions were

and

. These types of solution are located in Region IV of

Figure 2; (iv) A bouncing solution, where

x starts at a high value, shrinks until it reaches a minimum value and then grows towards infinity. This solution is portrayed in

Figure 3d. For this particular example, the initial conditions were

and

. These types of solution are located in Region III of

Figure 2.

5. Conclusions

In the present work, the probability for the birth of a homogeneous and isotropic FLRW Universe with positively curved spatial sections (

) was studied. The matter content of the model is composed of a dust perfect fluid. The potential barrier of the model originates from the geometry of space-time, the fluid energy density and the presence of running cosmological constant, which can be interpreted as the zero-point energy of the quantum vacuum in Quantum Field Theory (QFT) [

64]. The Hamiltonian was found using the ADM formalism and the model was quantized using the Dirac formalism.

We explicitly calculated the tunneling probabilities and for the birth of the Universe as a function of the phenomenological parameter (), the dust energy E, the cosmological constant energy density () and the Hubble parameter ().

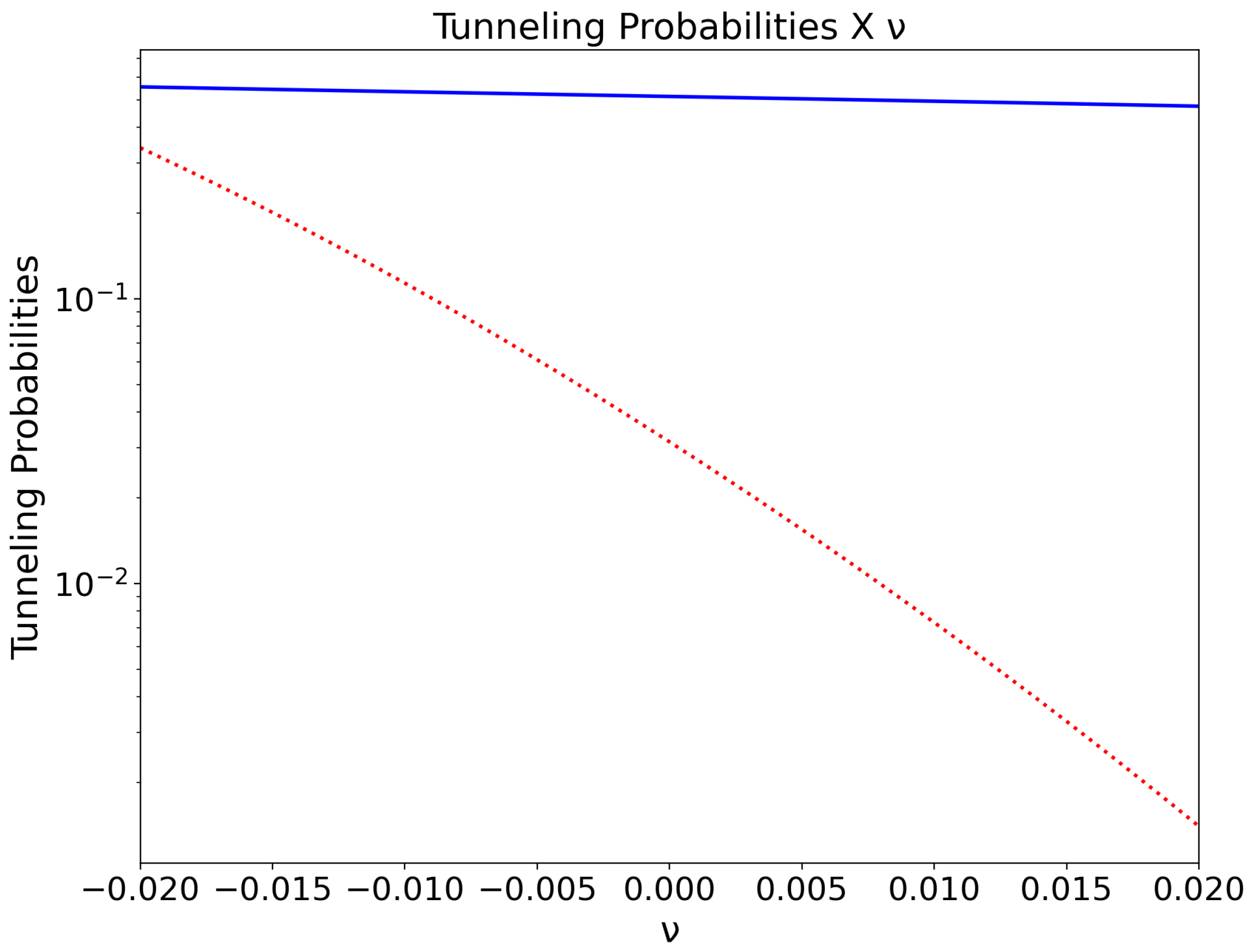

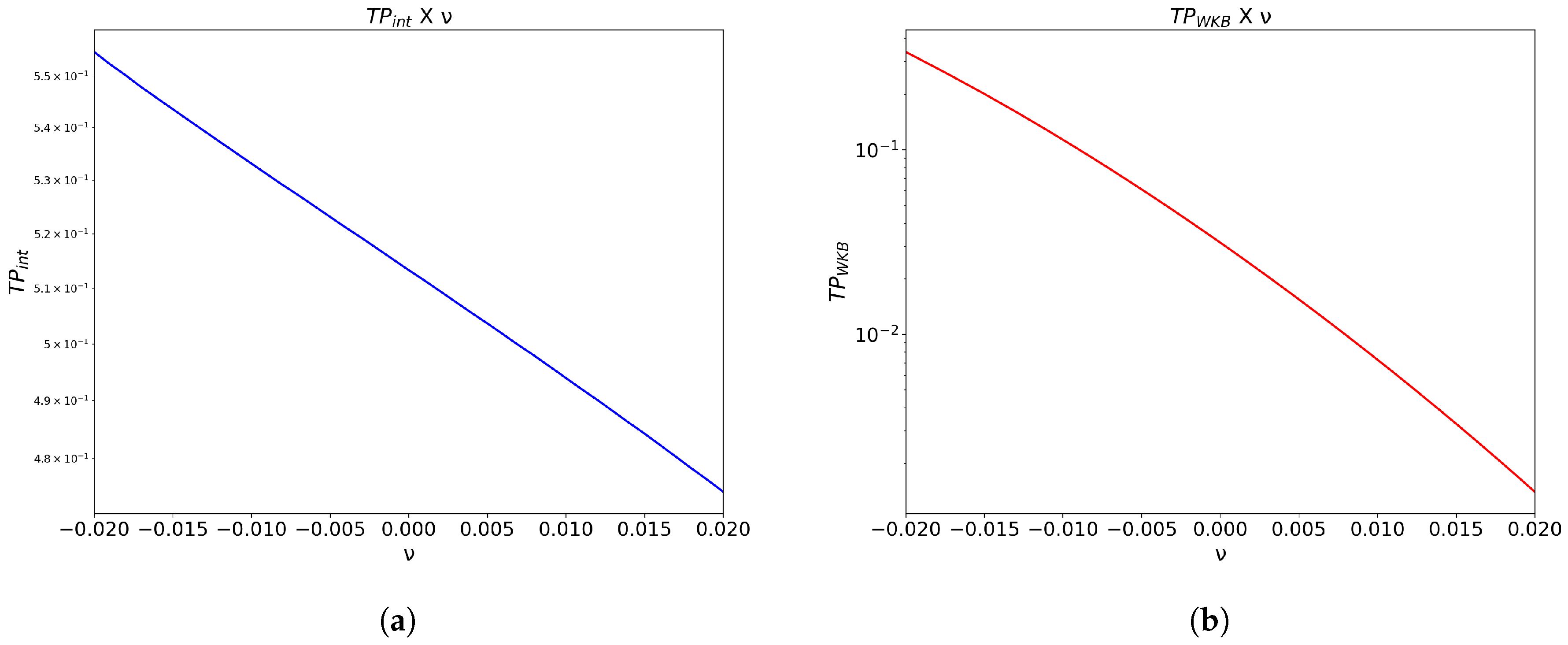

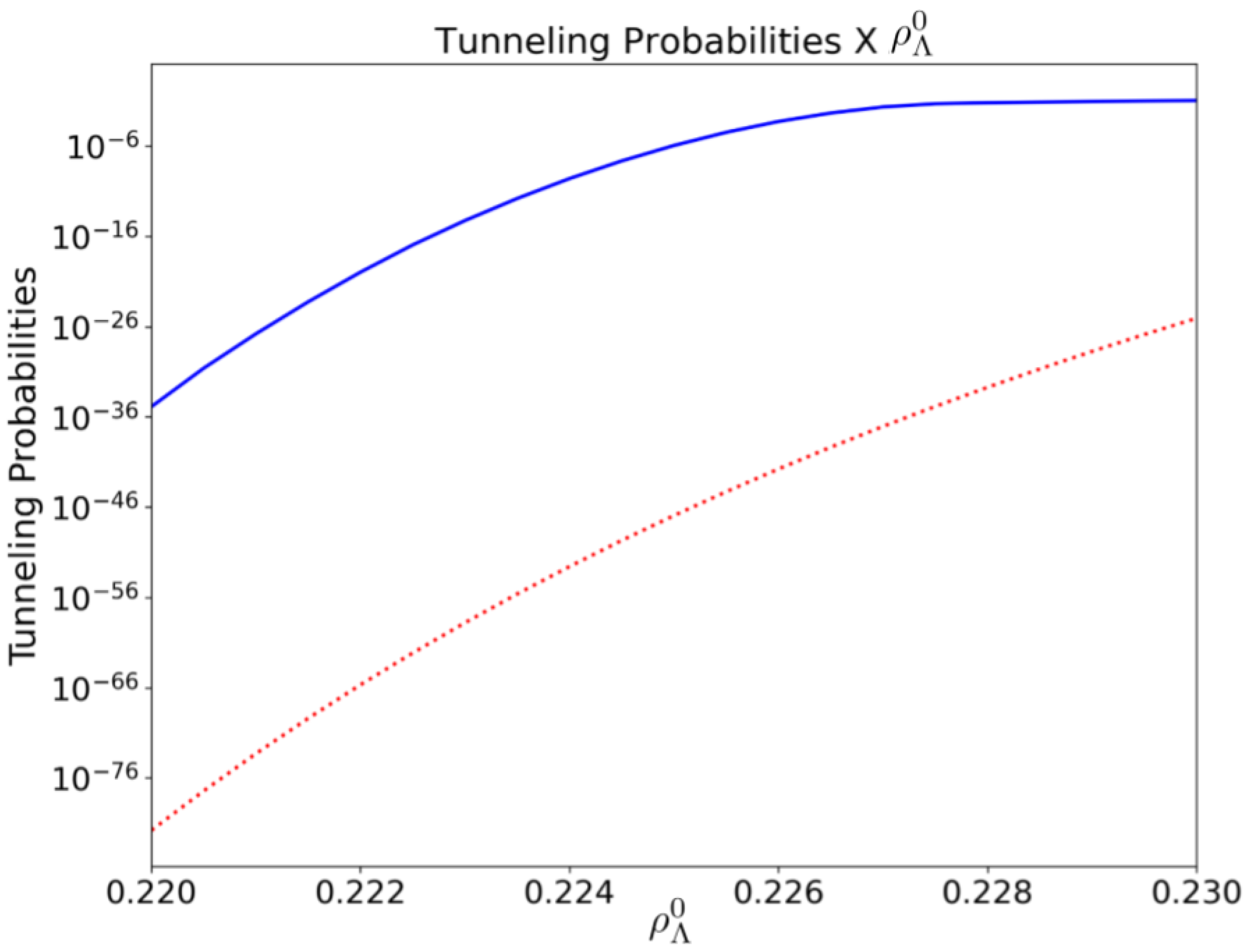

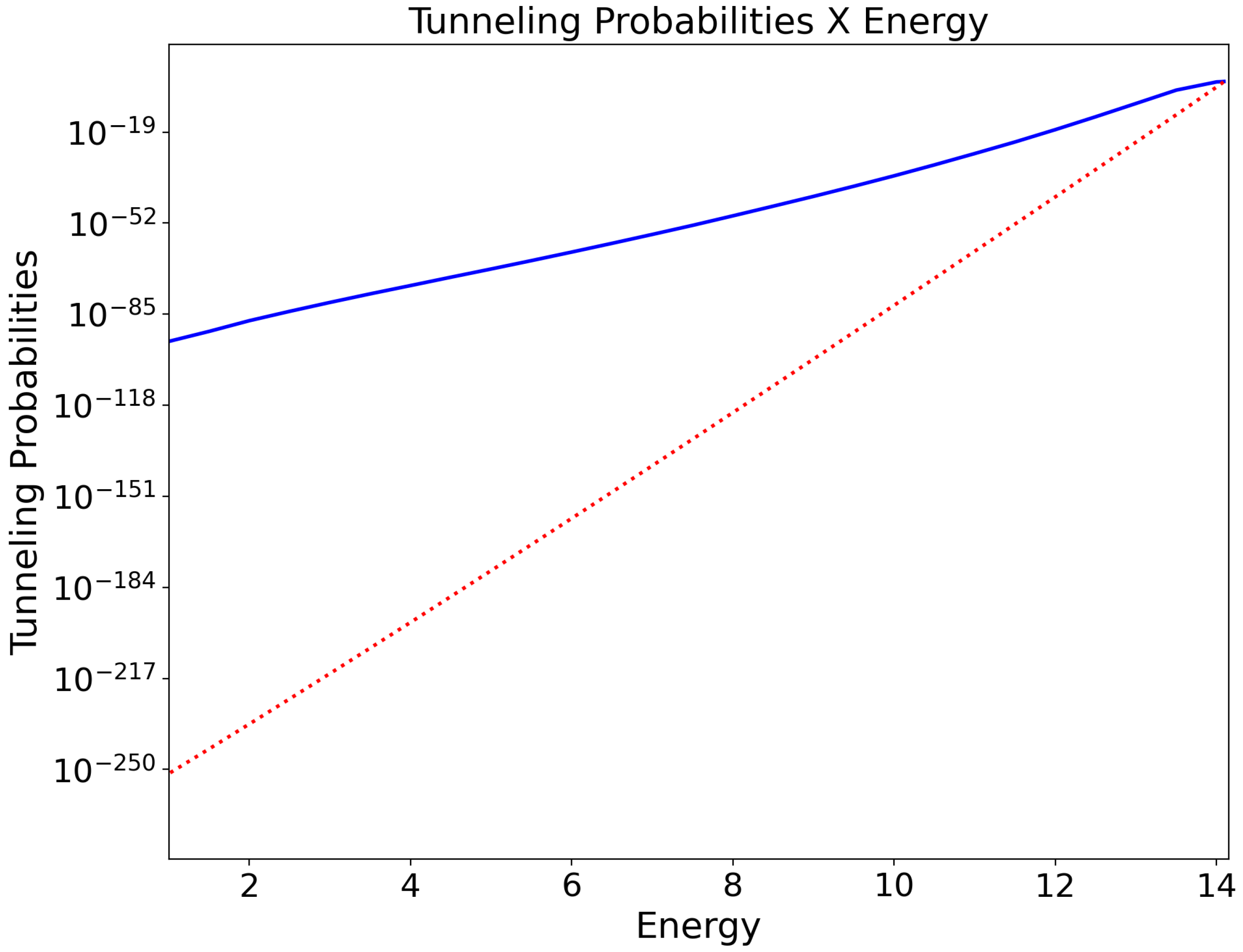

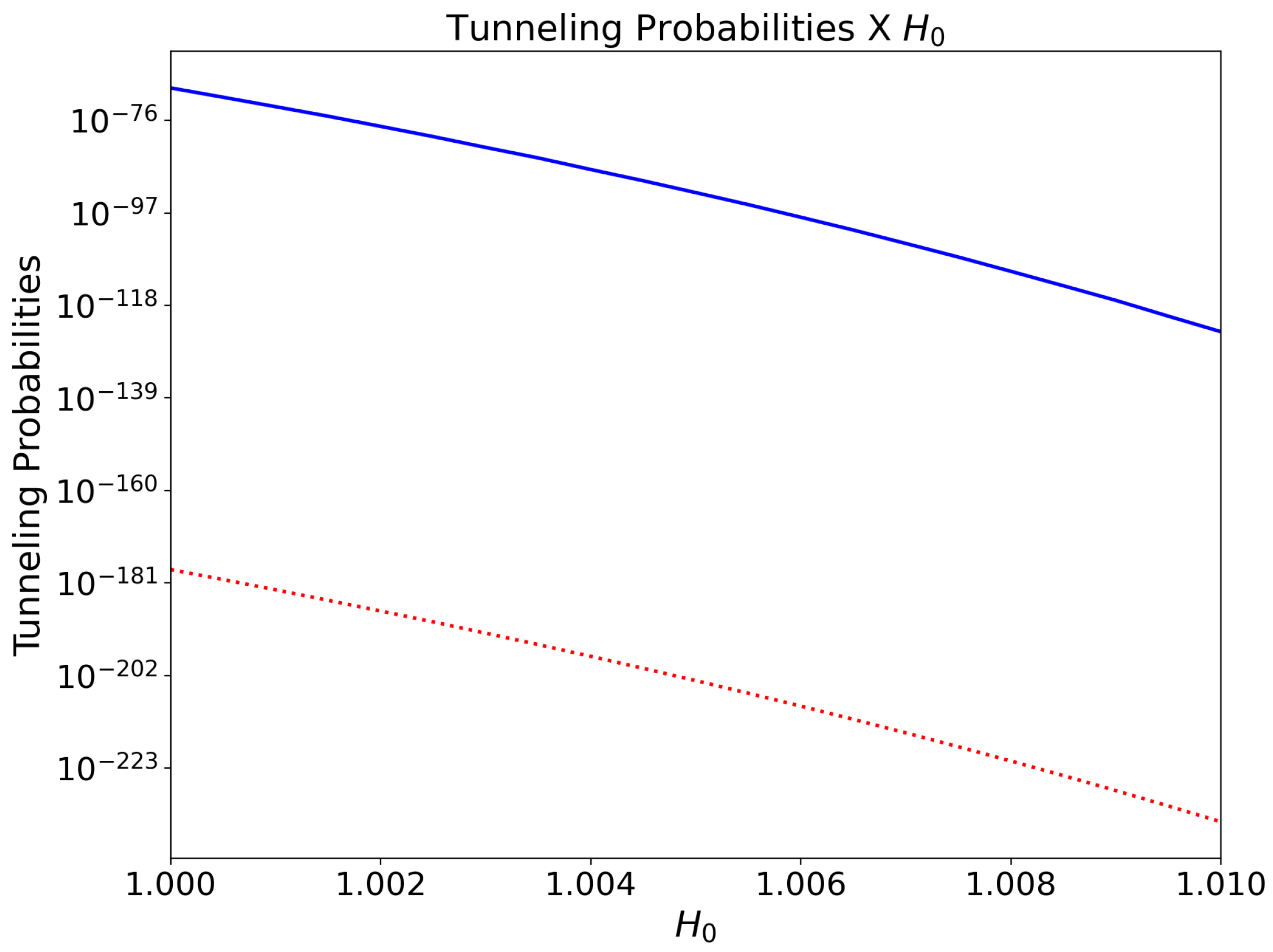

It was observed that both tunneling probabilities, and , decrease as one increases . It was also noted that and grow as E increases, indicating that the Universe is more likely to be born with higher values of the dust energy E. The same is observed for the parameter, that is, and are bigger for higher values of . Finally, the tunneling probabilities decrease as one increases the value of .

So, the best conditions for the Universe to be born, in the present model, would be having the higher possible values for E and and the lowest possible values for and .

Figure 1.

Potential with , and .

Figure 1.

Potential with , and .

Figure 2.

Phase portrait of the model made with the potential values , and , while the parameter takes different values. The dashed line occurs when and is called the separatrix.

Figure 2.

Phase portrait of the model made with the potential values , and , while the parameter takes different values. The dashed line occurs when and is called the separatrix.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a shows a contraction solution, where

x begins at a higher value and decreases to

.

Figure 3b depicts an expanding solution, where

x begins at lower value and expands towards infinity.

Figure 3c shows an expansion followed by a contraction.

Figure 3d shows a bouncing solution, where

x starts at a high value, shrinks to a minimum and begins an expansion immediately to infinity.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a shows a contraction solution, where

x begins at a higher value and decreases to

.

Figure 3b depicts an expanding solution, where

x begins at lower value and expands towards infinity.

Figure 3c shows an expansion followed by a contraction.

Figure 3d shows a bouncing solution, where

x starts at a high value, shrinks to a minimum and begins an expansion immediately to infinity.

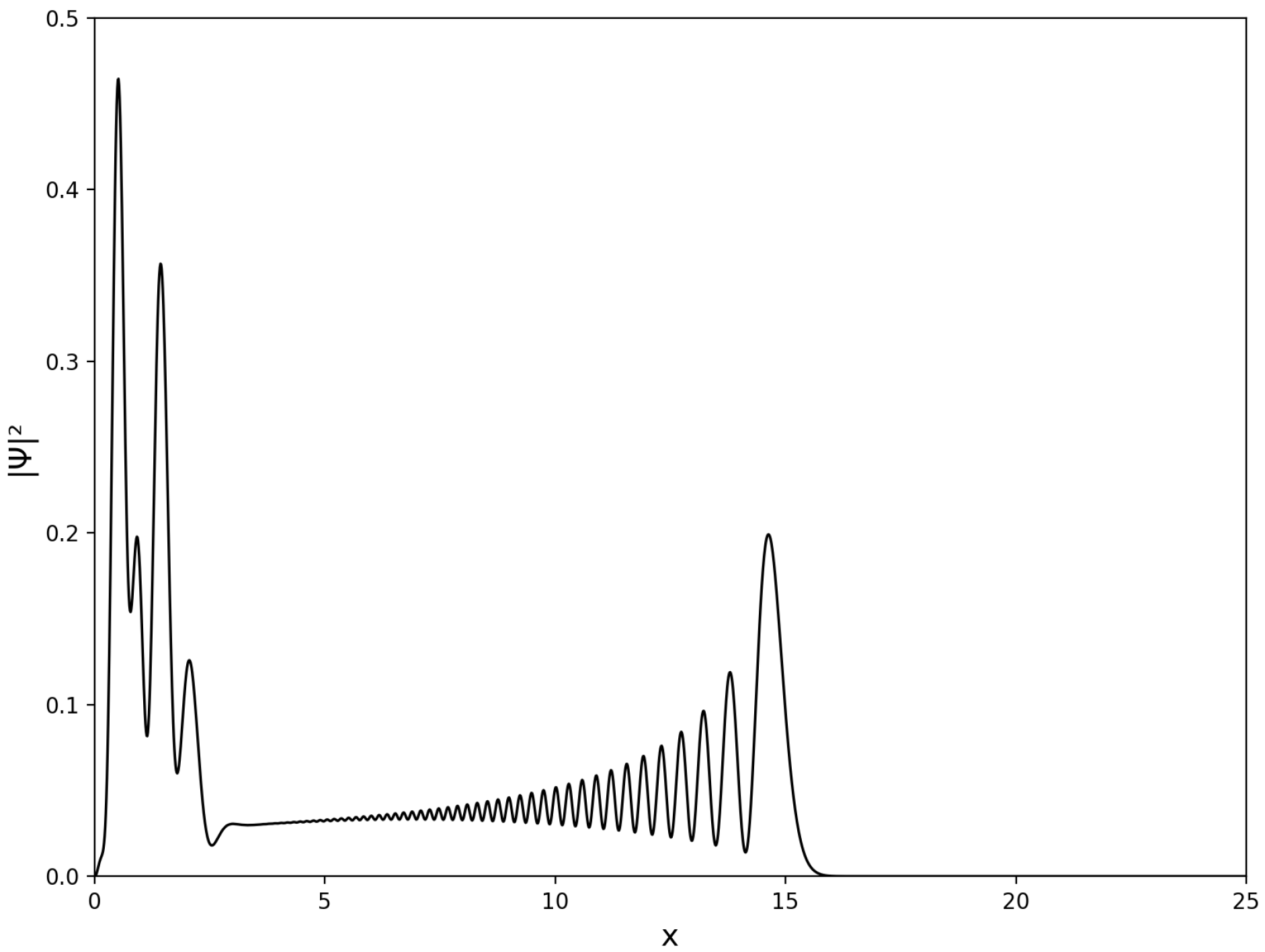

Figure 4.

for , , , at the moment , when reaches the numerical infinity, defined as .

Figure 4.

for , , , at the moment , when reaches the numerical infinity, defined as .

Figure 5.

Comparison between (solid line) and (dots) as changes for a simulation time and fixed energy . changes more slowly compared to and this gives the impression of being almost a constant line.

Figure 5.

Comparison between (solid line) and (dots) as changes for a simulation time and fixed energy . changes more slowly compared to and this gives the impression of being almost a constant line.

Figure 6.

Individual comparison of (a) and (b) as changes for a simulation time and fixed energy . Here one can see that both decrease as increases.

Figure 6.

Individual comparison of (a) and (b) as changes for a simulation time and fixed energy . Here one can see that both decrease as increases.

Figure 7.

Comparison of (solid line) and (dots) as changes for a simulation time and fixed energy .

Figure 7.

Comparison of (solid line) and (dots) as changes for a simulation time and fixed energy .

Figure 8.

Comparison of (solid line) and (dots) as energy E changes for a simulation time .

Figure 8.

Comparison of (solid line) and (dots) as energy E changes for a simulation time .

Figure 9.

Comparison of (solid curve) and (dots) as changes for a simulation time and fixed energy .

Figure 9.

Comparison of (solid curve) and (dots) as changes for a simulation time and fixed energy .

Table 1.

Variation of and as grows with a simulation time and a fixed energy .

Table 1.

Variation of and as grows with a simulation time and a fixed energy .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Variation of and as grows with a simulation time and a fixed energy .

Table 2.

Variation of and as grows with a simulation time and a fixed energy .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

The variation of and as E changes for a simulation time .

Table 3.

The variation of and as E changes for a simulation time .

| Energy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Variation and as grows with a simulation time and a fixed energy .

Table 4.

Variation and as grows with a simulation time and a fixed energy .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|