1. Introduction

The Valdivian temperate rainforest is home to a variety of unique species, some of which produce edible berries with potentially beneficial compounds. However, these species are endangered by climate change, growing population and timber industry [

1,

2]. Previous research has identified phenolic compounds and several anthocyanins in some of endemic berries collected in the Valdivian forest [

3,

4]. Recently, from

Azara serrata Ruiz & Pav. several rare glycosylated anthocyanins were detected and quantified using UHPLC-DAD-TIMS-TOF-MS, and showed inhibition of specific enzymes related to chronic non-communicable diseases (CNCD) [

5]. Luzuriaga is a small Gondwanean genus with three representative species in the Southern area of America (

L. Marginata (Gaertner) Bentham,

L. radicans R. & P., and

L. polyphylla (Hooker) Macbride), and only one species from Oceania (

L. parviflora (Hooker) Kunth.) [

6].

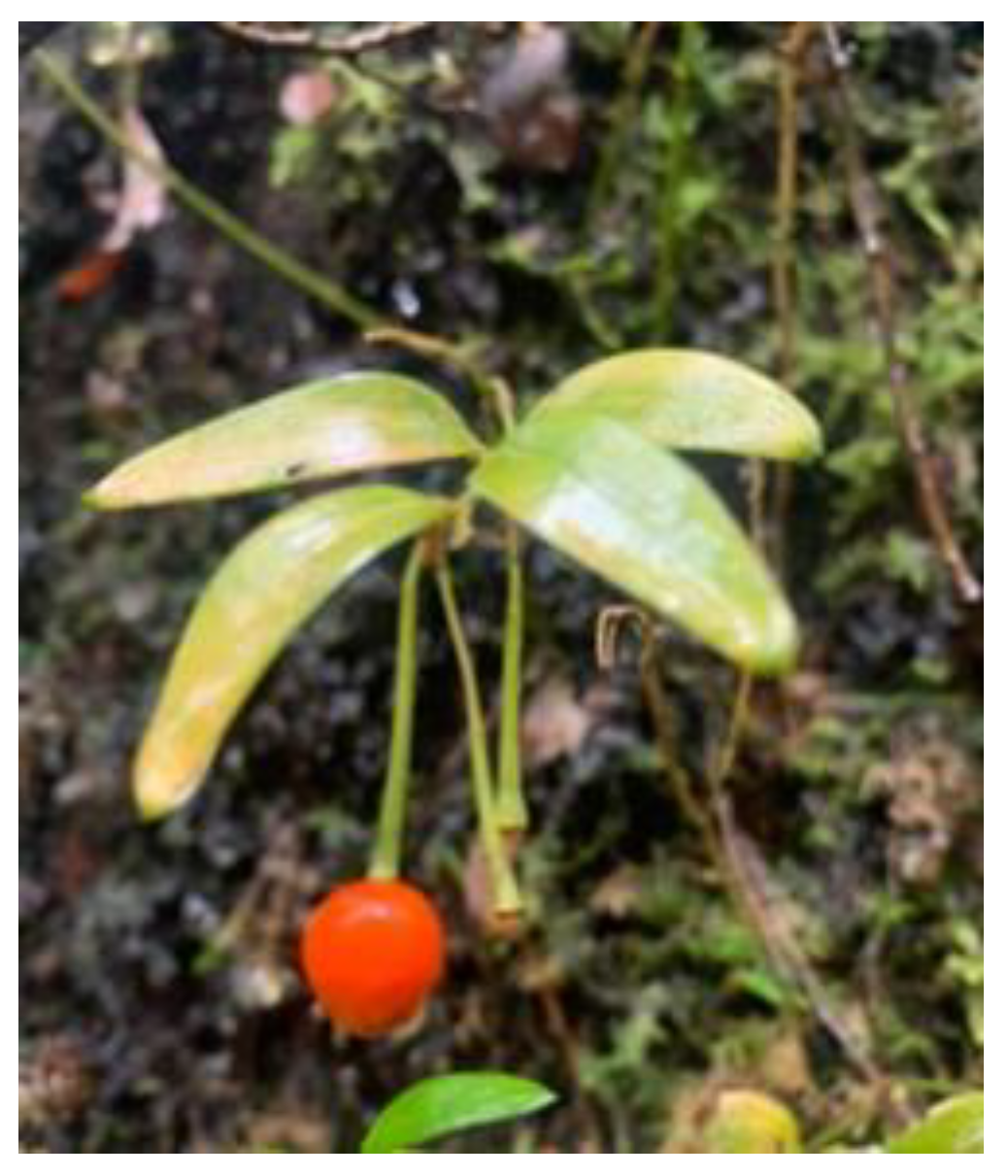

Luzuriaga radicans Ruiz & Pav. (

Figure 1) is an evergreen semi-herbaceous vine. Its leaves are up to 4 cm long, with 4-13 parallel veins. It has fragrant flowers with 2-4 articulated peduncles. The plant is a climbing vine growing in trees in O'Higgins, Maule, Ñuble, Biobío, Araucanía, Los Ríos, Los Lagos, and Aysén Regions of Chile. Its has edible orange-red berries that can be used as antipyretic, while its stems are used in crafting, particularly for basketry, brooms, and other household utensils. So far there are no scientific studies about chemistry and scarce bioactivity of the edible fruits from

L. radicans, therefore it represents and intriguing opportunity to find new medicinal properties of the berries, and possibly significant chemotaxonomic contributions. This work aims to measure the proximate composition, metals, antienzimatic (glucosidase, amylase, BuChE and AChE) and antioxidant properties of the orange berries, and to analyze for the first time the carotenoid profile by UHPLC-DAD, HPLC-APCI(+)-MS and UHPLC-ESI(+)-TOF-MS from the berries.

2. Results and Discussion

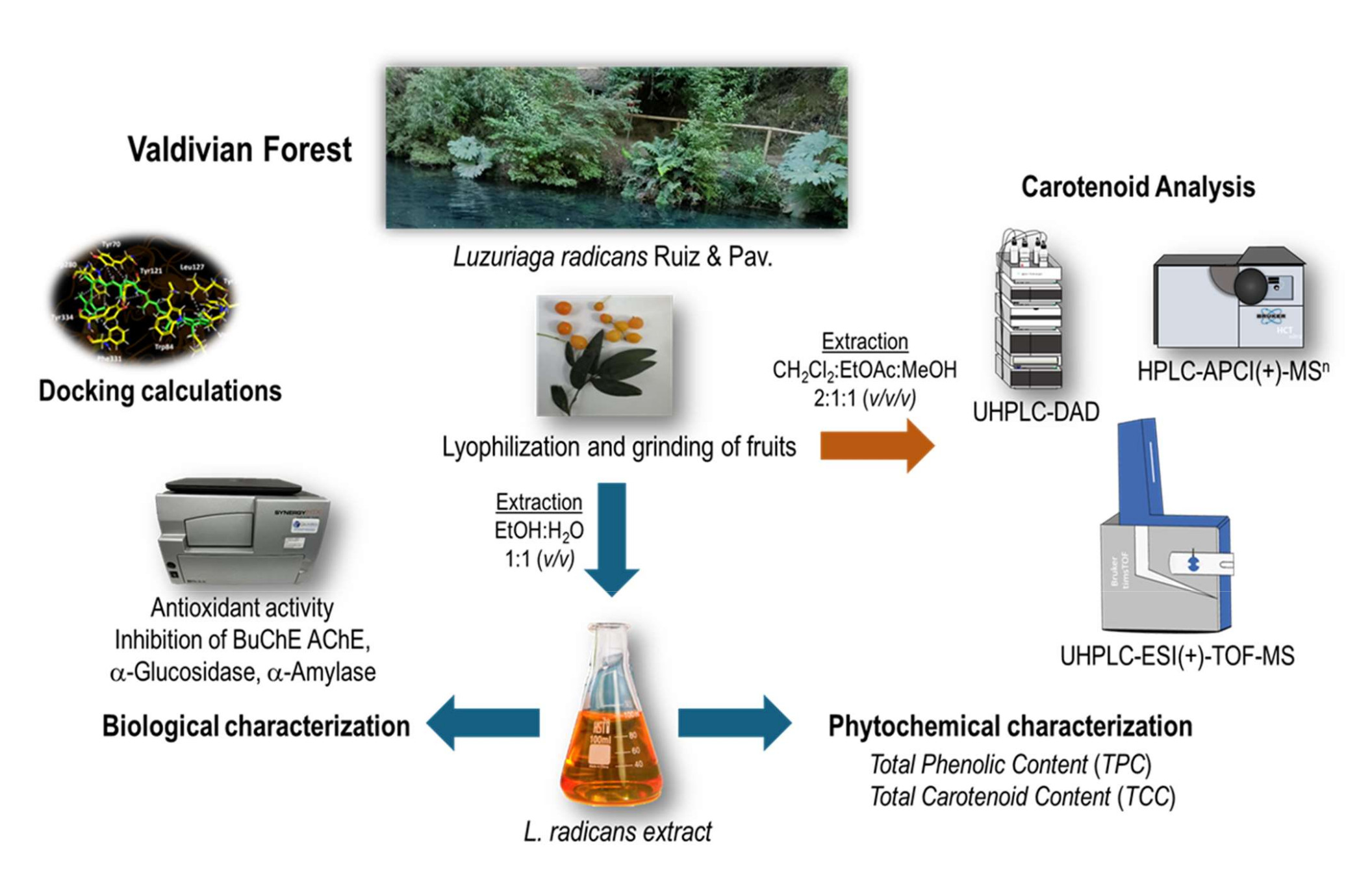

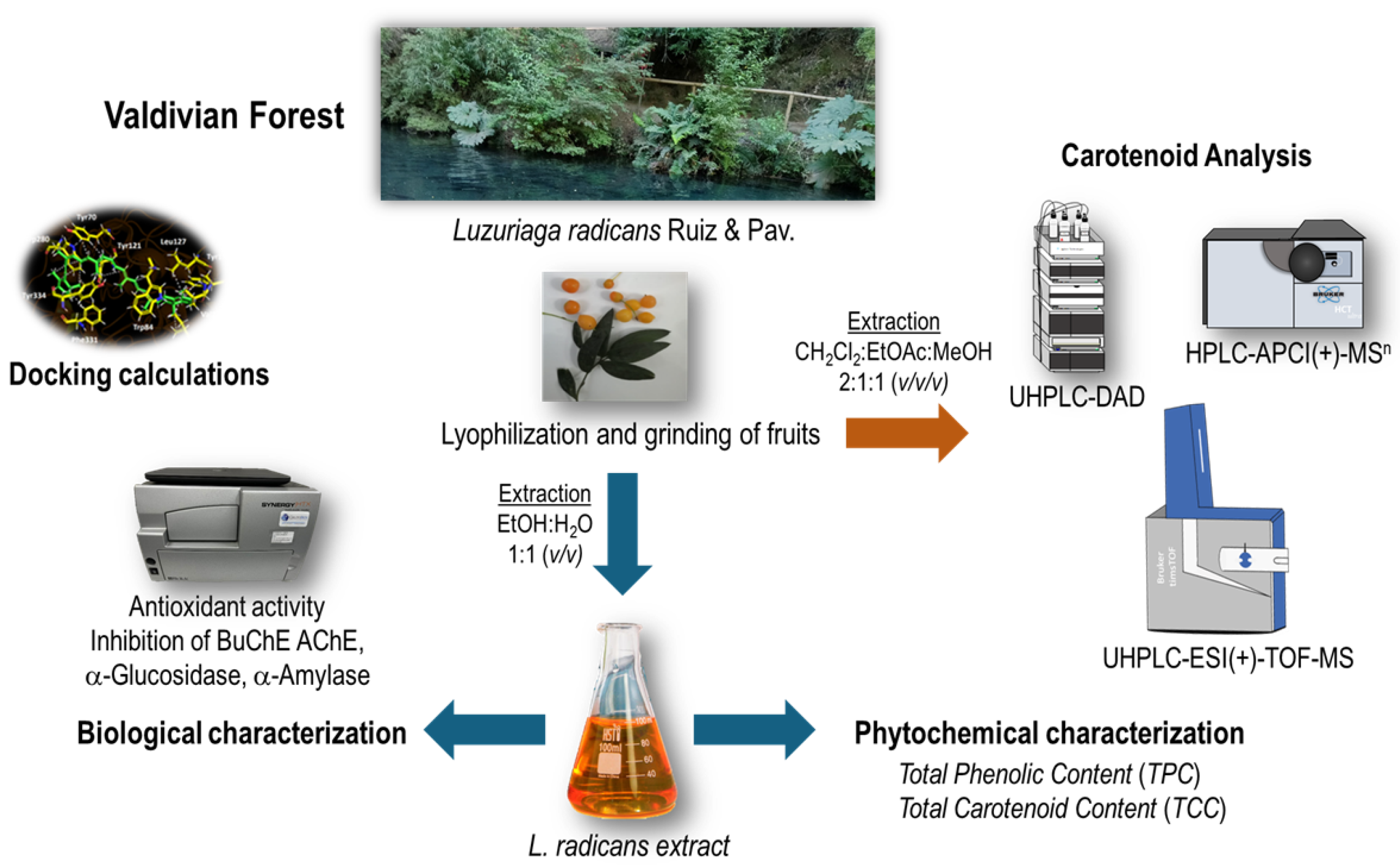

L. radicans fruits was collected in Saval Park, Valdivia, Chile in april 2023. The lyo- philized berries (50 g) were grounded to obtain a fine powder. An ethanol:water 1:1 (v:v) extract was prepared by maceration. This extract was chemically characterized, standar- dized and its functional properties were determined (

Figure 2).

2.1. Metals and Proximate Composition

The results of the proximate composition (

Table 1) showed that

L. radicans fruits are rich in carbohydrates (65.5 %) and have a low lipid (0.03 %), and protein content (6.34 %), and the mineral content showed that the fruits are rich in magnesium (6.82 mg/kg) and potassium (43.26 mg/kg) but lower in sodium, which make this berry very good for the elderly and better than other fruits such as the case of

Azara dentata [

4]. Mg and Ca are important minerals for supporting heart functions, bone formation, metabolizing glucose, relaxing muscle, and conducting memory. The results obtained regarding the proximate composition of these berries indicate that these undepreciated fruits, generally underva- lued and considered only for decorative purposes, could be used as an important source of minerals, fiber, and protein, and that these results may encourage their consumption.

2.2. Antioxidant Activity and Content of Phenolic and Carotenes

During oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydroxyl radicals, and non-radical species such as hydrogen peroxide, are produced [

7]. These species can react with a wide range of molecules present in living cells, such as amino acids, sugars, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, leading to their oxidation and, consequently, patholo- gical processes or alterations in foods or cosmetics [

8]. Various methods are used to mea- sure the antioxidant capacity of natural products and evaluate their potential use as an- tioxidants. In this study, total phenolic compounds by spectrometry were discrete (9.33 ± 0.01 mg GAE/g dry weight), lower than Valdivian

A. serrata berries (57 mg GAE/g dry weight) [

5], while total carotenoids were high measured by spectroscopy (79.0 ± 0.3 mg carotene/100 g fruit) and also by HPLC, (98 mg/100 g) compared to orange cocona fruits CD1 ecotype (12.2 mg/100 g fruits) [

9]. The ORAC is a fluorescent and sensitive method [

10], while ABTS•+ assay is a reproducible technique used to evaluate the antioxidant properties of extracts by donating hydrogen atoms to form a non-radical molecule [

11]. In this study

L. radicans extract achieved IC

50 = 6.65 ± 0.5 μg/mL and IC

50 = 9.95 ± 0.05 μg/mL in the DPPH and ABTS antiradical methods. This antioxidant capacity can be compared with natural antioxidants used commercially (gallic acid DPPD: IC

50 = 4.32 ± 0.5; quercetin: IC

50 = 12.23 ± 0.8 µg/mL). Furthermore, ORAC and FRAP (108.9 ± 4.07 and 47.8 ± 0.01 μmol Trolox/g dry fruit, respectively) were lower than that of

A. serrata (387 and 426 μmol Trolox/g dry fruit, respectively) [

5] (

Table 2). ORAC is also higher than those of

Ugni molinae berries (222 μmol TE/g dry fruit) [

12]. Due to this activities, the extract could be included in cosmetic, medicinal, or food products to protect them from oxidation or for skin or body care against the effects of free radicals.

2.3. Enzyme Inhibitory Properties

Several important enzymes related to CNCD were analyzed using the hydro-ethanolic extract of the endemic fruits of

L. radicans. The results are shown in

Table 2. Some of the enzymes implicated in the development of metabolic syndromes are glucosidases, amylases, and lipases. α-Glucosidase and α-amylase are important hydrolases that release glucose by digesting glycogen and starch, and are implicated in diabetes and various other diseases such as infections and cancer [

13]. Inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase slows carbohydrate digestion and absorption and subsequently suppresses postprandial hyperglycemia [

14]. In this study

L. radicans extract showed no inhibitory activity on those enzymes, but showed activity against cholinesterases (AChE and BuChE). Cholinesterase enzymes play a fundamental role in the development of Alzheimer's disease (AD), since they catalyze the hydrolysis and inactivation of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, producing choline and acetate. Cholinesterase inhibitors, such as some phenolic compounds, improve cholinergic function in AD, preserving acetylcholine levels, and are therefore a good strategy for the symptomatic treatment of AD [

15]. Inhibition of these enzymes could also be useful in cases of autism and schizophrenia [

16], as well as dementia and Parkinson's disease [

17]. In this study, the most notable results were those of acetylcholinesterase (IC

50: 6.904 ± 0.42), several times less active to that of standard galantamine (IC

50: 0.402 + 0.02), and butyrylcholinesterase (IC

50: 18.38 ± 0.48), although glucosidase and amylase inhibition was very low (IC

50: more than 1000) compared to acarbose, cholinesterases inhibition activity could lead to the discovery of a naturally occurring drug useful for further treatment.

2.4. Analysis of the Carotenoid Profile

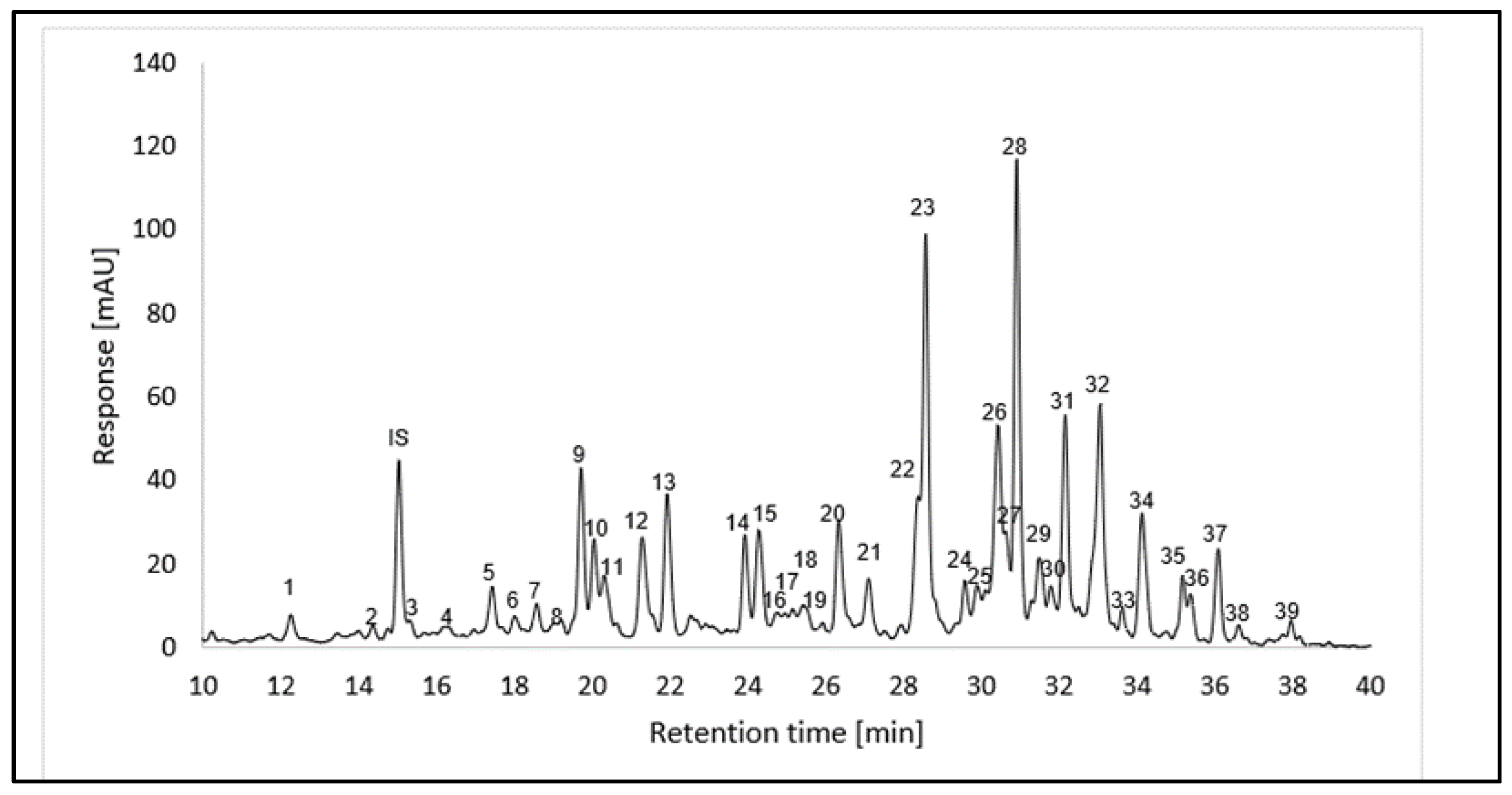

2.4.1. Chromatographic Analysis of Carotenoids

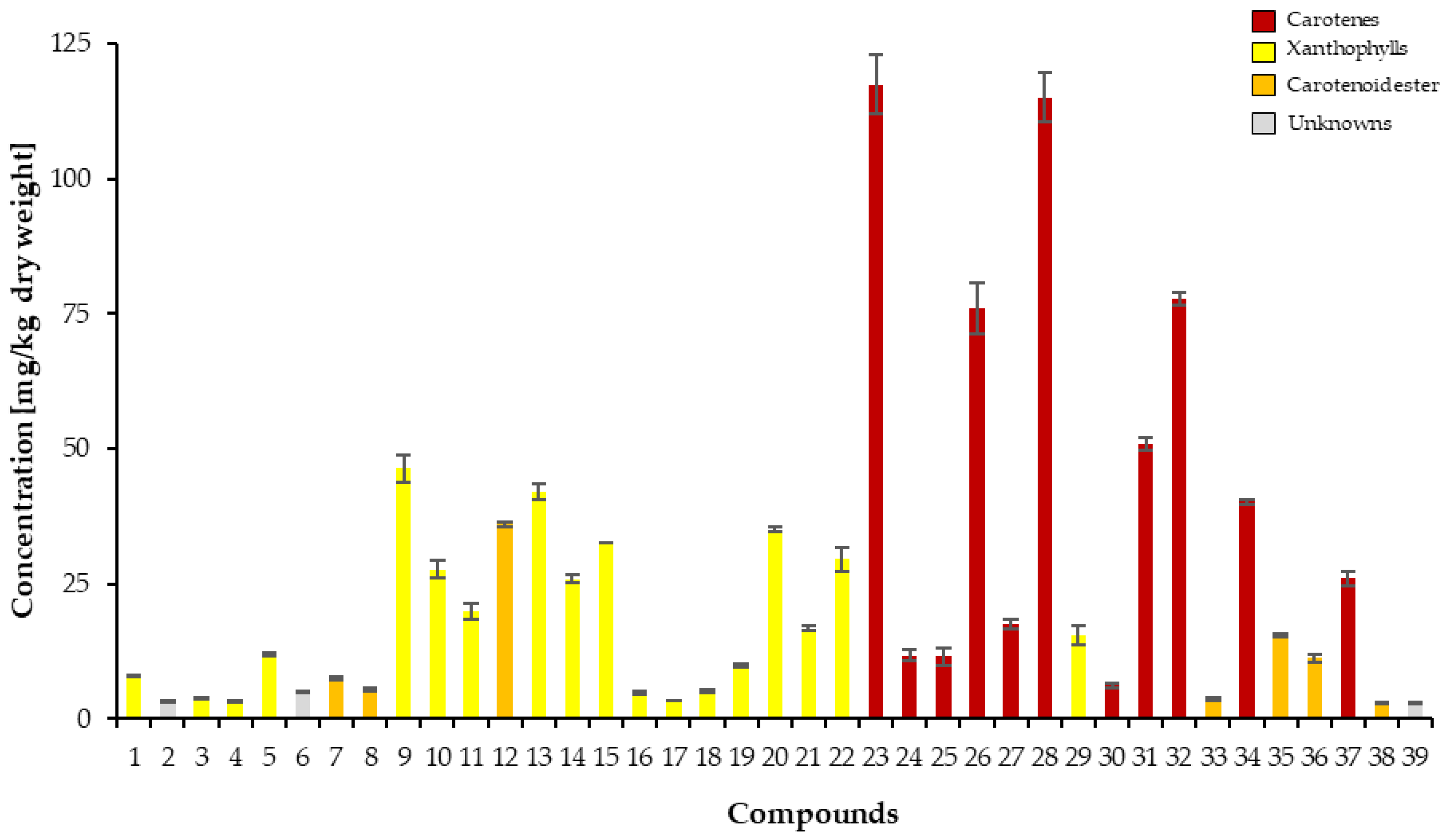

Carotenoids are a class of natural pigments that we all know for the colors ranging from orange to red and yellow of many fruits, vegetables, and flowers, as well as for the provitamin A activity that some of them possess. The analysis of the carotenoid profile was performed by UHPLC-DAD, HPLC-APCI(+)-MSn and UHPLC-ESI(+)-TOF-MS. Identification was performed for carotenoids and carotenoid esters using MSn and DAD data. Carotenoids have characteristic absorption spectra, so the wavelengths of the ma- xima were determined and the %III/II-ratio was calculated. Molecular ions were determined by using APCI(+)-MSn measurements. Thirty-nine peaks (

Figure 3 and

Table 3) were tentatively identified for the first time in

L. radicans extract in positive ionization mode. The carotenoids could be identified by their UV spectrum and molecular ions, and literature data were used for qualification.

A number of different carotenoids belonging to the groups of carotenes, xanthophylls and carotenoid esters were identified on the basis of the DAD and MS data. A total of 14 compounds from the carotene group can be tentatively identified (peaks 23-28, ms4, 30-34 and 37). The largest group consists of (all-E)-β-carotene, γ-carotene, (all-E)-lycopene and various cis-isomers of these carotenes (peaks 23, 25, 26, 28, 30-32, 34 and 37), which are characterized by the m/z of 537 and characteristic absorption maxima. Peak 24 has an m/z of 539 and can be assigned to β-zeacarotene. Three isomers of ζ-carotene could be determined with m/z 541 (peaks ms4, 27 and 28) [

18]. The largest number of carotenoids in the fruit are free xanthophylls with 19 compounds (peaks 1, 3-5, 9-21 and 29). Peak 1 can be assigned to a coelution of (all-E)-lutein and (all-E)-zeaxanthin, and peak 10 to (all-E)-β-cryptoxanthin. Peaks 3-5 and 9, have an m/z of 569, due to the absorption maxima for peaks 3 and 5 at λ = 466 nm they could be cis-isomers of lutein or zeaxanthin. A total of 13 peaks (4, 11-21 and 29) can be assigned to xanthophylls with an m/z of 553; the carotenoids α-cryptoxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, 5,8-epoxy-α-carotene, 5,6-epoxy-β-carotene and zeinoxanthin can be considered according to the literature. According to our detected MS peaks (

Table 3) ni, xanthophyll (MW 552) can be assigned to α-cryptoxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, 5,8-epoxy-α-carotene, 5,6-epoxy-β-carotene or zeinoxanthin, while ni, xanthophyll (MW 600) can be attributted to violaxanthin, auroxanthin, neoxanthin or luteoxanthin.

The carotenoid profile of

L. radicans revealed a number of esterified carotenoids in addition to the free xanthophylls and carotenes. The parent xanthophylls were tentatively identified as: esters with (all-E)-violaxanthin (peaks 12, ms1, ms2, 31, 33) [

19,

20,

21]; (all-E)-β-cryptoxanthin (peaks 35 and 38) [

22] and (all-E)-antheraxanthin (peak ms3, 32) [

19,

20] (

Table 3). Further esters could be partially assigned on the basis of the MS data, whereby peaks 6, 7, 8, 10 and 27 belong to xanthophylls with MW 600, which may be (all-E)-viola-xanthin, auroxanthin, neoxanthin or luteoxanthin. Peaks 13, 33 and 37 can be assigned to esters of xanthophylls with MW 568, i.e. in the literature zeaxanthin-dimyristate, zeaxanthin-dilaurate and zeaxanthin myristate palmitate were tentative identified [

18,

19]. The carotenoid esters identified in this study mainly contained the saturated fatty acids palmitic acid (C12:0) and myristic acid (C14:0), which were bound as mono or diesters. In addition, three xanthophyll esters with capric acid (C:10) were detected with peaks 6, 7 and 27 and two xanthophyll esters containing palmitic acid (C:16) with peak 13 and ms2.

Carotenoids are lipid soluble compounds that show antioxidant properties by sca- venging radicals [

23] and for instance the ABTS·+ radical [

24], especially due to the conjugated double bond system in the structure of carotenoids [

25], but the main beta carotene suffers trans (E) to cis (Z) isomerization, while the (all-E)-form is the predominant isomer found in unprocessed carotene-rich plant foods [

26]. Some articles also link higher caro- tenoid intakes and tissue concentrations with reduced cancer and cardiovascular disease risk [

23]. However, some authors mention that dependence on chain length and character of the terminal function varies the activity in TEAC assay with increasing activity as: β-apo-8’-carotenal < β-apo-8’-carotenoic acid ethyl ester < 6’-methyl-β-apo-6’-carotene-6’-one (citranaxanthin) [

26].

2.4.2. Qualitative Analysis of Carotenoids

The quantification of carotenoids of

L. radicans extract was performed by UHPLC-DAD as β-carotene equivalents using an internal standard (

Figure S1 and

Table S1) [

27] and

Figure 4 shows the carotenoid concentrations in pulp and skin of

L. radicans. The carotenes have the highest quantitative proportion with a content of 549.93 ± 22.95 mg/kg fresh weight and a proportion of 55.92 % of the total content. The various xanthophylls have a total content of 340.42 ± 13.99 mg/kg fresh weight and a contribution of 34.62%. The xanthophyll esters represent the group with the lowest content; 82.04 ± 2.21 mg/kg fresh weight and 8.34 %. The carotenoids (15-Z)-β-carotene, (all-E)-β-carotene, γ-carotene and (13-Z)-β-carotene, which have the highest content, all belong to the carotene group.

In Chile, studies on species of the Alstroemeriaceae family are very scarce and have been limited to in vitro micropropagation and germination trials for production and germplasm conservation purposes [

28,

29,

30]. However, the presence of carotenoids in

L. radicans is comparable to species of the genus

Lilium, which contain β-carotene and (E/Z)-phytoene in significant concentrations [

31], along with plants such as

Zamia dressleri [

32],

Sorbus aucuparia [

33],

Moringa oleifera [

34], and

Vaccinium spp., whose chemical profiles show high contents of carotenes and their derivatives with diverse biological effects.

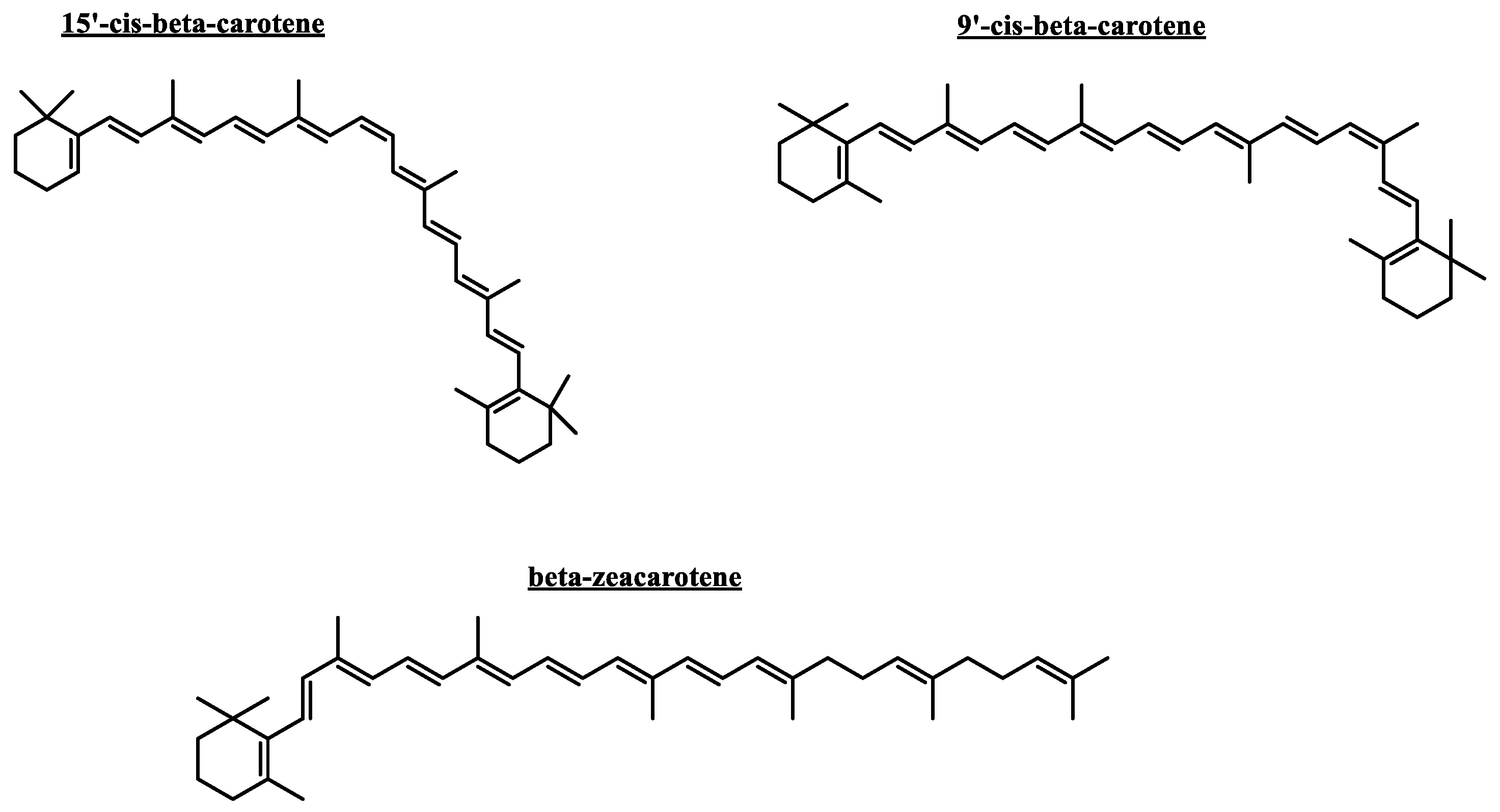

2.5. Docking Simulations

Docking simulations were performed for every carotenoid shown in

Figure 5. Each molecule was fully optimized, energetic minimizations and protonation or deprotonation, were carried out using the LigPrep tool in Maestro Schrödinger suite v.11.8 (Schrödinger, LLC) [

36].

Selected carotenoid compounds 9’-cis-β-carotene, 15’-cis-β-carotene and β-zeacarotene, as well as the known cholinesterase inhibitor galantamine were subjected to docking assays into the acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase catalytic sites, aiming to analyze the molecular interactions between the different enzymes and the chosen derivatives, as well as to obtain the energy docking descriptors. This step aimed to provide a rationale for the inhibitory activities observed with the previously mentioned carotenoids (

Table 4).

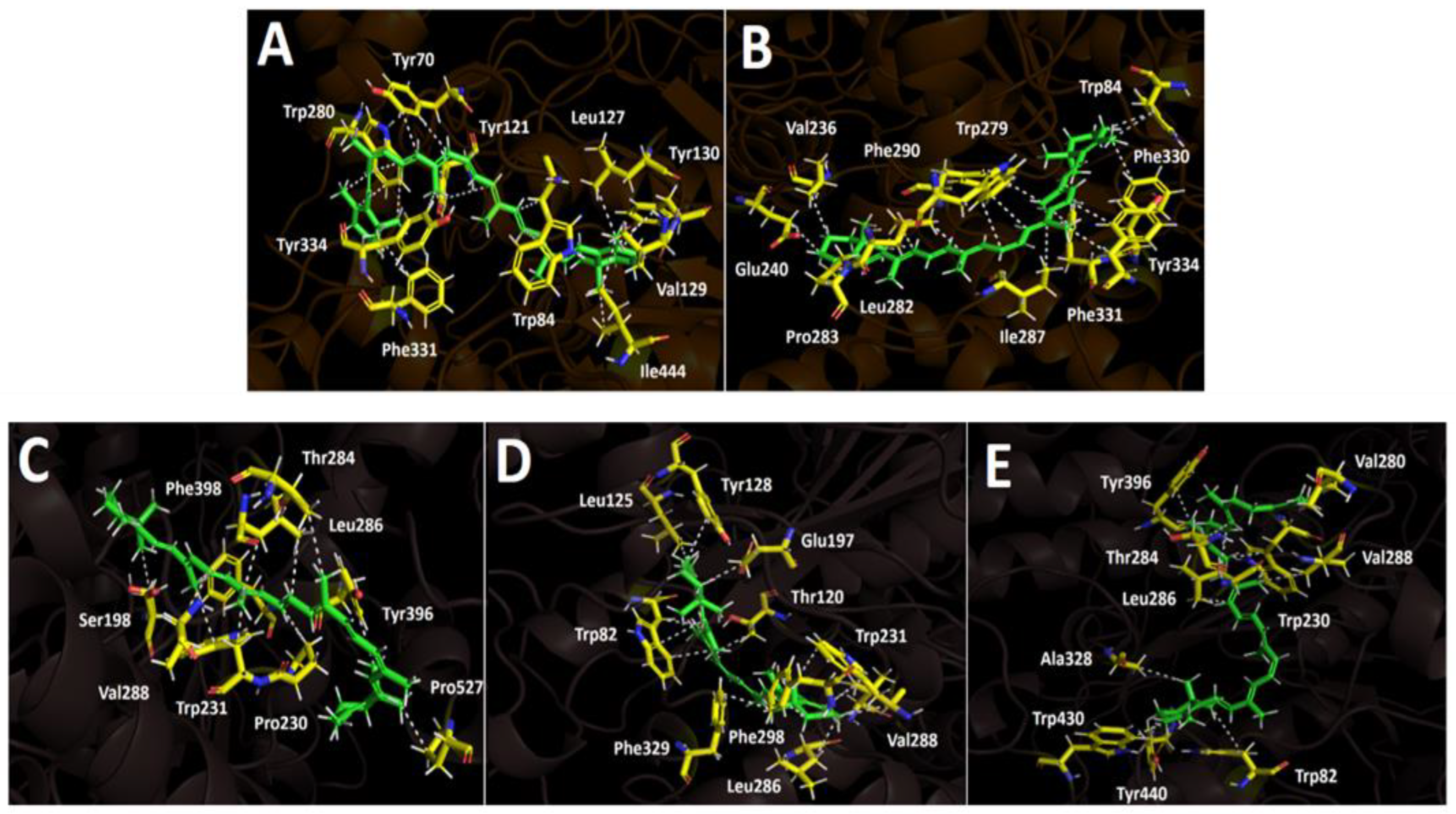

2.5.1. Acetylcholinesterase (TcAChE) Docking Results

The two selected carotenoids 9’-cis-β-carotene and 15’-cis-β-carotene formed multiple hydrophobic interactions within the catalytic site of acetylcholinesterase, particularly with hydrophobic residues lining the surface of the catalytic gorge, which are key contri- butors to their inhibitory activity. Within acetylcholinesterase, both carotenoids adopt a comparable orientation, exhibiting a partially bent conformation as a result of the high rotational flexibility conferred by their hydrocarbon chains. Binding energies obtained for the two derivatives were notably favorable and comparable to the binding energy of the inhibitor (−12.989 kcal/mol, see

Table 4). Owing to the nature of its chemical structure, the carotenoid 9’-cis-β-carotene displays multiple hydrophobic interactions with the enzyme’s amino acid residues, resulting in a binding energy of −9.780 kcal/mol. The hydrophobic interactions observed for this derivative, considering it lacks polar groups, involve the residues Tyr70, Trp84, Tyr121, Leu127, Val129, Tyr130, Phe331, Trp280, Tyr334, and Ile444 (

Figure 6A). On the other hand, compound 15’-cis-β-carotene performed hydrophobic interactions as well. The implicated amino acids were Trp84, Val236, Glu240, Trp279, Leu282, Pro283, Ile287, Phe290, Phe330, Phe331 and Tyr334 (

Figure 6B). The binding energy was -11.356 kcal/mol, which correspond to a better value compared to 9’-cis-β-carotene due to the greater number of interactions formed by this second derivative.

2.5.2. Butyrylcholinesterase (hBuChE) Docking Results

Butyrylcholinesterase belongs to the same structural class of proteins as acetylcholinesterase, both being members of the esterase/lipase family and classified as serine hydrolases [

37,

38]. Like acetylcholinesterase, this enzyme possesses a deep and narrow gorge lined with several hydrophobic residues [

39]. Therefore, three carotenoids—9’-cis-β-carotene, 15’-cis-β-carotene, and β-zeacarotene—were subjected to docking assays with this enzyme. β-zeacarotene possesses a long aliphatic chain and only one cycloaliphatic substituent; thus, it was included to evaluate whether lipophilic hydrocarbons contribute to binding affinity, considering that exhibits a cLogP value of 15.466. Binding energies from docking assays of carotenoid compounds against butyrylcholinesterase exhibited a similar pattern to those observed with acetylcholinesterase. The three tested carotenoids showed binding energies comparable to that of galantamine (

Table 4). Notably, 9’-cis-β-carotene stood out with an energy of -9.815 kcal/mol. Similar to acetylcholinesterase, the carotenoids subjected to docking assays in butyrylcholinesterase predominantly engaged in hydrophobic interactions, due to the nature of their structures, which lack polar groups. In this sense, 9’-cis-β-carotene performed several hydrophobic interactions with Ser198, Pro230, Trp231, Thr284, Leu286, Val288, Tyr396, Phe398 and Pro527 (

Figure 6C).

On the other hand, 15’-cis-β-carotene and β-zeacarotene, also exhibit distinct hydrophobic interactions with the active site residues of butyrylcholinesterase demonstrating their potential for stable binding within the enzyme's hydrophobic pocket. 15’-cis-β-carotene interacts hydrophobically with residues such as Trp82, Thr120, Leu125, Tyr128, Glu197, Trp231, Leu286 Val288, Phe298 and Phe329, (

Figure 6D). These interactions indicate that this compound is likely positioned deep within the hydrophobic cleft of butyrylcholinesterase engaging with both aromatic and aliphatic re- sidues, stabilizing the molecule through Van der Waals interactions. Likewise, β-zeacarotene forms hydrophobic contacts as well, with a slightly different set of residues: Trp82, Trp230, Val280, Thr284, Leu286, Val288, Ala328, Tyr396, Tyr440 and Trp430 (

Figure 6E). The presence of Val and Leu residues supports a strong hydrophobic anchoring within the enzyme. Interestingly, the three compounds share interactions with, Val288, and Leu286, which may represent key hydrophobic hot spots within the butyrylcholineste- rase. These shared residues could be central to the binding of hydrophobic molecules and may influence the affinity of similar compounds.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals, Reagents and Materials

Distilled water, ultrapure water, ethyl acetate, ethanol, Folin–Ciocalteau reagent, ascorbic acid, AlCl3, FeCl3, gallic acid, magnesium metal, CH3CO2K 1M, quercetin, dimethyl sulfoxide, FeSO4, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,4,6, tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ), 2,20-azo-bis (2-amidinopropane dichlorohydrate), and analytical grade solvents were obtained from Merck® (Santiago de Chile). Trolox, β-Apo-8`-carotenal, DMSO with purity higher than 95% were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chem. Co. (St Louis, MO, USA), Phytolab gmbH & Co. KG (Verstenbergsgreuth, Germany) or Extrasynthese (Genay, France), acetylcholinesterase (TcAChE, EC 3.1.1.7), butyrylcholinesterase (hBuChE, EC 3.1.1.8), 4-nitrophenyldodecanoate, phosphate buffer, dinitrosalicylic acid, trichloroacetic acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), fetal calf serum (FCS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), L-glutamine (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), α-amylase, α-glucosidase, standard p-nitrophenyl-D-glucopyranoside, acarbose, sodium persulfate sodium carbonate, ferrous sulfate, sodium acetate, sodium sulfate anhydrous, and absolute ethanol were obtained from Sigma Aldrich Chem. Co. (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Double-deionized water (Nanopure®, Werner GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany). Methanol (HPLC grade) was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, U.K.). Disodium hydrogen phosphate dihydrate (≥99.0%, p.a.), and citric acid (≥99.5%, p.a.) were obtained from Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG (Karlsruhe, Germany). The solvents used for the UHPLC-DAD-TOF analyses were water (LC-MS grade) and methanol (UHPLC-MS-grade), purchased from TH. Geyer GmbH & Co. KG (Renningen, Germany).

3.2. Plant Material

L. radicans (

Figure 1) mature fruits and aerial parts were collected in Saval Park, Valdivia, Chile (-39.8068° S, 72.9162° W) in april 2023 and kept at -80

oC until processing. The berries were freeze-dried (Labconco Freezone 4.5 l, Kansas, MO, USA) to perform the chromatographic and mass spectrometric analyses.

3.3. Berry Extract Preparation

The extraction for biological activities was performed with water: absolute ethanol 1:1 v:v, with sonication (ultrasound probe SXSONIC Processor (Sonics, Inc, Shangai, China) using 1 g each of separated freeze-dried pulp and peel, with 10 ml ethanol, 15 min, 3 times in the dark) and the one for carotenoid analysis was performed with dichloromethane (CH

2Cl

2)/ethyl acetate (EtOAc)/Methanol (MeOH) (50/25/25, v/v/v) [

40]. For this purpose, 50 mg of freeze-dried and deseeded fruit was added to an Eppendorfcap containing 1 mL of DCM/EtOAc/MeOH (50/25/25, v/v/v) (0.1% BHT), then 50 µL of ISTD β-Apo-8`-carotenal was added. The sample was vortexed for 1 min and then centrifuged for 5 min. 500 µL was taken and put into an Eppendorfcap along with 700 µL of Mc-Ilvaine buffer (pH = 7). The sample was mixed with the vortexer for 1 min and then centrifuged for 5 min. 300 µL was removed and placed in a roll edge glass and dried under N

2.

For analysis, the extract was diluted in 0.3 mL tBME/MeOH (90/10, v/v) and filtered through a 0.2 µm PTFE syringe filter. Extraction was performed in triplicate. All steps for the carotenoid extraction were performed under red light.

3.4. Chemical Contents

3.4.1. Determination of Proximate Composition

The proximate composition was determined using the freeze-dried parts (pulp, and peels) of

L. radicans according to the methods established by AOAC [

41] with some mo- difications [

42]. Moisture content was analyzed by direct drying in a circulating air oven: 5 g of each freeze-dried sample was added to pre-weighed porcelain crucibles and maintained at 105 °C until a constant weight was reached. For ash analysis, 5 g of each sample was placed in porcelain crucibles, carbonized, and incinerated in a muffle furnace at 550 °C until only ash remained. For protein analysis, 0.4 g of each sample was weighed in filter paper, placed in Kjeldahl tubes, and treated with 10 mL of sulfuric acid and 2 g of a catalytic mixture (potassium sulfate and copper sulfate). Digestion was done in a digestion block at 450 °C until the solution became bluish-green. After digestion, the samples were allowed to cool to ambient temperature, transferred to clean Kjeldahl tubes, and placed in a nitrogen distiller. In the distiller, 25 mL of 30% NaOH was added to each digested sample to initiate distillation. The distillate was collected in a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 10 mL of distilled water and 2 drops of phenolphthalein indicator, then titrated with HCl. Lipid content was determined by direct extraction of the sample with petroleum ether in a continuous Soxhlet extractor. For this purpose, 5 g of each sample was placed in Soxhlet extraction cartridges. The cartridge containing the sample was added to the extractor and allowed to reflux for approximately 8 hours. After distillation, the petroleum ether was removed from the flask by vacuum. The flask with the residue was dried in an oven at 105 °C for about 1 hour, then cooled in a desiccator to room temperature and weighed. Levels of the minerals magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), iron (Fe), calcium (Ca), zinc (Zn), potassium (K), copper (Cu) and manganese (Mn), were determined in a mineral measurement apparatus (Varian AA240, Belrose, Australia) using atomic absorption spectroscopy, previously set with standard solutions with known amounts of the minerals being determined using flames of air-acetylene and nitrous oxide-acetylene, with the latter only being used for calcium analysis. Hollow monometa- llic cathode lamps were used for each element analyzed. All analyses were performed in triplicate.

3.4.2. Total Polyphenols and Carotenes Quantification

Standardized protocols were used to determine the total phenolic content (TPC) and total carotenoid content (TCC). Absorbance was recorded in multiplate reader (Synergy HTX, Billerica, MA, USA). The calibration curves were done using gallic acid and a beta-carotene standard [

9]. The phenolic compounds content and carotene content were expressed as μg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per mL (μg GAE/mL) and mg of beta-carotene per g of sample, respectively.

3.4.3. Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) Diode Array Detector (DAD) Analysis for the Quantification of the Carotenoids

For the quantitation of the carotenoids, an Agilent 1290 Infinity II System (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a binary solvent manager, an autosampler, a column heater, and a diode array detector was used. The column was a Accucore C30 column, 150 x 3,0 mm, 2,6 µm, Thermo Scientific (Dreieich, Deutschland), with a colum temperature of 14 °C, column flow of 0.4 mL min-1, and an injection volume of 5 µL. The mobile phases consisted of methanol/water (87/13, v/v; eluent A) and methanol/tBME/water (90/7/3, v/v; eluent B), using a gradient program as follows: 0 min, 2 % B; 2 min 14.5 % B; 5.5 min, 22 % B; 37 min, 69 % B; 38 min, 69 % B; 39 min, 95 % B; 42 min, 95 % B; 43 min, 2 % B; 48 min, 2 % B. The UV-Vis spectra were obtained in the range of 200-600 nm; while the chromatograms were analyzed at λ = 470 nm. Quantification was performed using external calibration with (all-E)-β-carotene recorded with 8 points from 1 - 500 mg/L, each measured 3-fold at λ = 470 nm (R2 = 0.9998). Carotenoids were quantified as (all-E)-β-carotene equivalents. Data analysis was performed using OpenLab Chromato- graphy Data System (CDS), ChemStation Edition, Version 3.4 (3.4.0) (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany).

3.4.4. HPLC-APCI(+)-MSn Analysis for the Quantification of the Carotenoids

For identification, samples were analyzed on an Agilent 1100/1200 series (Waldbronn, Germany) HPLC system, consisted of a binary pump (G1312A), autosampler (G1329A), column oven (G1316A), and diode array detector (G1315B), and was coupled with an ion-trap mass spectrometer (HCT Ultra ETD II, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) using an APCI (atmospheric pressure chemical ionization) ionization source. The same column was used as for the quantitative analysis using UHPLC-DAD with a column temperature of 22 °C. The mobile phases consisted of methanol/water (90/10, v/v; eluent A) and methanol/tBME (10/90, v/v; eluent B), using a gradient program as follows: 0 min, 2 % B; 2.0 min 14.5 % B; 37 min, 69 % B; 38 min, 69 % B; 39 min, 95 % B; 42 min, 95 % B; 43 min, 2 % B; 48 min; 2 % B. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min and the injection volume was 5 µL. The diode array detector was operated in an acquisition range of 200–700 nm. The HPLC-MS runs were additionally monitored at λ = 470 nm. The APCI source was operated in positive mode using nitrogen as a nebulizer (45 psi) and drying gas at a rate of 7.0 L/min (temp. 350 °C). The scan range was set between m/z 125 and 1250 using the ultra-scan mode with a mass scanning range of 26.000 m/z per second. MS1 parameters were as fo- llows: voltage of high-voltage (HV) capillary -3500 V, HV end plate offset −500 V, trap drive 64.0, octopole Rf amplitude 0.0 Vpp, lens 1 -200.0 V, capillary exit −200.0 V, target mass 500, max. accumulation time 200.000 μs, ion charge control (ICC) target 100,000, average of four spectra. Results were evaluated with the software Data Analysis 4.0 (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany).

3.4.5. UHPLC-TOF-MS Analysis for the Quantification of the Carotenoids

The chromatographic analysis was performed on an Agilent 1290 Infinity system including the same parts as the system used for the quantitation. The column used was an Accucore C30 column, 150 x 3,0 mm, 2,6 µm, Thermo Scientific (Dreieich, Deutschland). The used mobile phases were (A) methanol / water (90/10; v/v) (B) tBME / MeOH / water (90/7/3; v/v/v), with temperature of 14 °C, flow of 0.4 ml min-1, and injection volume of 5 µL. The gradient was the same as for the carotenoid analysis using UHPLC-DAD (section 3.4.3).

For the mass spectrometry, the system was a timsTOF equipped with an electrospray ionization source (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). For ESI-positive measurements, the settings were scan range 100-1850 m/z; inversed ion mobility range 1/k0, 0.55-1.90 V* s/cm-2; ramp time, 67.3 ms; spectra rate, 13.64 Hz; collision RF, 1100 Vpp; transfer time, 65 µs; capillary voltage, 4500 V; nebulizing gas pressure, 2.20 bar (N2); dry gas flow rate, 10 L min-1(N2); nebulizer temperature, 220 °C; collision energy, 10 eV. To calibrate the mass spectrometer and trapped ion mobility, the ESI-L Low Concentration Tuning Mix (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) was used. To operate the system, the software was Bruker Compass Hystar Version 6.2 and otofControl Version 6.2 (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). For evaluating the analyses, Bruker Compass Data Analysis Version 5.3 (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany) was used.

3.5. Antioxidant Activity

The free radical scavenging and antioxidant capacity of the different extracts was determined by spectrophotometric methods using a microplate reader (Synergy HTX, Billerica, MA, USA).

3.5.1. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) Assay

The ORAC assay evaluates the radical scavenging capacity by application of 2,2-Azo-bis (2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) to the samples. Excitation and emission wavelengths were measured at λ = 485 and 530 nm, respectively, using Trolox for the calibration curve. Results are expressed in μmol Trolox/g of dry fruit [

5].

3.5.2. Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

The FRAP assay was based on the reduction of the ferric 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine complex (Fe3+-TPTZ to Fe2+-TPTZ), which generates a blue coloration in the samples and was measured by spectrophotometry at λ = 593 nm using a Trolox standard curve. Results are expressed in μmol Trolox/g of dry fruit [

5].

3.5.3. DPPH Scavenging Activity

The bleaching of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical was used, which turns colorless as antioxidants provide protons. The reaction was monitored by spectrophotometry at λ = 515 nm using a gallic acid standard curve. Results are expressed in μg/mL, denoting the half inhibitory concentration (IC

50) [

43].

3.5.4. ABTS Scavenging Activity

The test was performed using ABTS 2,2-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothioazolin-6-sulfonic acid) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The decrease in absorbance was recorded at 1 and 6 minutes after the start of the reaction, and the percentages of decolorization were subsequently calculated [

11]. The assays were performed in triplicate. The IC

50 value (concentration capable of eliminating 50% of the free radicals) was determined.

3.6. Enzymatic Inhibitory Activity

3.6.1. Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibition Assays

The inhibitory activity of the Cholinesterase enzymes was evaluated as described previously [

5]. Briefly, a solution with 5-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) was prepared in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 0.02 M MgCl2 and 0.1 M NaCl. Then, the hydroethanolic extract of Luzuriaga (50 L, 2 g/mL) was mixed in a 96-well microplate with 125 mL of DTNB solution, acetylcholinesterase (TcAChE) or butyrylcholinesterase (hBuChE) (25 L); It was dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) and incubated for 15 min at 25 °C. The reaction was initiated by the addition of acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCI) or butyrylthiocholine chloride (BTCl) (25 µL). After 10 min of reaction, the absorbance at a wavelength of 405 nm was measured and the IC

50 (μg/mL) was calculated [

5].

3.6.2. α-Glucosidase Inhibition Assay

Solutions were read at λ = 415 nm in microplate reader over a one-minute interval for a total of 20 min, employing an acarbose standard curve. The stock solution of the α-glucosidase enzyme was prepared in 2 mL at 20 U/mL of buffer for subsequent dilution. Results are expressed as (IC

50) in μg/mL [

10].

3.6.3. α-Amylase Inhibition Assay

Solutions were read by spectrophotometry at λ = 515 nm using an acarbose standard curve. The α-amylase enzyme at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL in 5 mL of 20 mM phosphate buffer solution at pH 6.9. Results are expressed in μg/mL (IC

50) [

10].

3.7. Docking Calculations

Docking calculations were performed for every carotenoid shown in

Figure 6. Each molecule was fully optimized, energetic minimizations and protonation or deprotonation, were carried out using the LigPrep tool in Maestro Schrödinger suite v.11.8 (Schrödinger, LLC) [

36]. The partial charges plus the geometries of all compounds were fully set using the DFT method with set B3LYP/6-311G+(d,p) as the standard basis [

44,

45] in Gaussian 09W software [

46]. Crystallographic enzyme structures of

Torpedo californica acetylcholi- nesterase (TcAChE; PDBID: 1DX6 code [

47]), plus human butyrylcholinesterase (hBChE; PDBID: 4BDS code [

48]) were acquired from the Protein Data Bank RCSB PDB [

49]. Enzyme optimizations were acquired using the Protein Preparation Wizard from Maestro software, where water molecules and ligands of the crystallographic protein active sites were removed. In the same way, all polar hydrogen atoms at pH 7.4 were added. Appropriate ionization states for acid and basic amino acid residues were pondered. The OPLS3e force field was employed to minimize protein energy. The enclosing box size was set to a cube with sides of 26 Å length. The presumed catalytic site of each enzyme in the centroid of selected residues were chosen, considering their accepted catalytic amino acids: Ser200 for acetylcholinesterase (TcAChE) [

50,

51], Ser198 for butyrylcholinesterase (hBChE) [

52,

53]. The Glide Induced Fit Docking protocol has been used for the final pairings [

54]. Compounds were pointed by the Glide scoring function in the extra-precision mode (Glide XP; Schrödinger, LLC) [

55] and were picked by the best scores and best RMS values (cutting criterion: less than 1 unit), to get the potential intermolecular interactions between the enzymes and compounds plus the binding mode and docking descriptors. Complexes were visualized in a Visual Molecular Dynamics program (VMD) and Pymol [

56].

3.8. Statistical Analysis

All assays were performed at least three times with three different samples. Each experimental value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical program InfoStat (student version, 2011) was used to assess the degree of statistical correlation between the different groups. Comparisons between groups were made using Tukey test.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the carotenoid composition of extracts from L. radicans was described for the first time, along with its potential use as an antioxidant and possible use against chronic non-communicable diseases. Overall, these findings expand our knowledge of secondary metabolites in native Luzuriaga species and validate some bioactivity, specially the potentiality as supplement in aid of Alzheimer disease (inhibition of AChE enzyme) laying the groundwork for future studies. Future studies should focus on evaluating the biological effects of the key pure unknown carotenoid compounds in animal or cellular models, along with pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetic research to elucidate their mechanisms of action. Furthermore, the development of biotechnological and or chemical synthesis strategies could enhance their future applications.

Supplementary Materials

: The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: external (all-E)-β-carotene-calibration curve; Table S1: quantified carotenoid contents [mg/kg DW], calculated as (all-E)-β-carotene equivalents.

Author Contributions

M.J.S., S.S., and R.G.; methodology J.R-P., S.S., R.G.; validation S.S., J.R-P.; formal analysis - experiments performed: S.S., J.R-P.; investigation - experiments performed: A.T-B., M.J.S, S.S., J.R-P., R.G.; - analyzed and interpreted the data: J.R-P., S.S.; resources M.J.S., P.W., A.T-B.; visualization M.J.S., R.G., J.R-P; writing—original draft preparation M.J.S., S.S., R.G., J.R-P; writing—review and editing M.J.S, S.S., R.G., A.T-B., J.R-P; supervision M.J.S. and R.G.; project administration M.J.S. and R.G.; funding acquisition P.W. and M.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FONDECYT 1220075.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fuentes-Castillo, T.; Hernández, H.J.; Pliscoff, P. Hotspots and ecoregion vulnerability driven by climate change velocity in Southern South America. Reg Environ Chang 2020, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecklin, D.; DellaSala, D.A.; Luebert, F.; Pliscoff, P. Valdivian Temperate Rainforests of Chile and Argentina. In Temperate and Boreal Rainforests of the World: Ecology and Conservation; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics, 2011; pp. 132–153.

- Brito, A.; Areche, C.; Sepúlveda, B.; Kennelly, E.J.; Simirgiotis, M.J. Anthocyanin characterization, total phenolic quantification and antioxidant features of some chilean edible berry extracts. Molecules 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, L.C.; Palacios, J.; Barrientos, R.E.; Gómez, J.; Castagnini, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Tapia, A.; Paredes, A.; Cifuentes, F.; Simirgiotis, M.J. UHPLC-MS Phenolic Fingerprinting, Aorta Endothelium Relaxation Effect, Antioxidant, and Enzyme Inhibition Activities of Azara dentata Ruiz & Pav Berries. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hopfstock, P.; Romero-Parra, J.; Winterhalter, P.; Gök, R.; Simirgiotis, M. In Vitro Inhibition of Enzymes and Antioxidant and Chemical Fingerprinting Characteristics of Azara serrata Ruiz & Pav. Fruits, an Endemic Plant of the Valdivian Forest of Chile. Plants, 2024; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Jara-Seguel, P.; Zúniga, C.; Romero-Mieres, M.; Palma-Rojas, C.; von Brand, E. Luzuriagaceae), Karyotype study in Luzuriaga radicans (Liliales: Luzuriagaceae). Biologia (Bratisl) 2010, 65, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, J.; Aran, J.M. Reactive oxygen species: Drivers of physiological and pathological processes. J Inflamm Res 2020, 13, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn Rev 2010, 4, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Arana, G.; Merino-Zegarra, C.; Riquelme-Penaherrera, M.; Nonato-Ramirez, L.; Delgado-Wong, H.; Pertino, M.W.; Parra, C.; Simirgiotis, M.J. Antihyperlipidemic and antioxidant capacities, nutritional analysis and uhplc-pda-ms characterization of cocona fruits (Solanum sessiliflorum dunal) from the peruvian amazon. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Benítez, A.; Ortega-Valencia, J.E.; Jara-Pinuer, N.; Ley-Martínez, J.S.; Velarde, S.H.; Pereira, I.; Sánchez, M.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P.; Sasso, F.C.; Simirgiotis, M.; et al. Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Potential of the Antarctic Lichen Gondwania regalis Ethanolic Extract: Metabolomic Profile and In Vitro and In Silico Evaluation. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conta, A.; Simirgiotis, M.J.; Martínez Chamás, J.; Isla, M.I.; Zampini, I.C. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Larrea cuneifolia Cav. Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Contribution to the Plant Green Extract Validation of Its Pharmacological Potential. Plants 2025, 14, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INTA PORTAL ANTIOXIDANTES. Available online: https://portalantioxidantes.com/orac-base-de-datos-actividad-antioxidante-y-contenido-de-polifenoles-totales-en-frutas/.

- Assefa, S.T.; Yang, E.Y.; Chae, S.Y.; Song, M.; Lee, J.; Cho, M.C.; Jang, S. Alpha glucosidase inhibitory activities of plants with focus on common vegetables. Plants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Laar, F.A.; Lucassen, P.L.; Akkermans, R.P.; Van De Lisdonk, E.H.; Rutten, G.E.; Van Weel, C. α-Glucosidase inhibitors for patients with type 2 diabetes: Results from a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, A. ; Ekavali A review on Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology and its management: An update. Pharmacol Reports 2015, 67, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E.; Rossignol, D.A. Treatments for biomedical abnormalities associated with autism spectrum disorder. Front Pediatr 2014, 2, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolinski, M.; Fox, C.; Maidment, I.; Mcshane, R. Cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease dementia and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, H.; Ikoma, Y.; Kato, M.; Kuniga, T.; Nakajima, N.; Yoshida, T. Quantification of carotenoids in citrus fruit by LC-MS and comparison of patterns of seasonal changes for carotenoids among citrus varieties. J Agric Food Chem 2007, 55, 2356–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petry, F.C.; Mercadante, A.Z. Composition by LC-MS/MS of New Carotenoid Esters in Mango and Citrus. J Agric Food Chem 2016, 64, 8207–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, P.E.; Carle, R.; Zacarías, L.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Schweiggert, R.M.; Steingass, C.B. Genuine Carotenoid Profiles in Sweet Orange [ Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck cv. Navel] Peel and Pulp at Different Maturity Stages. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 13164–13175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, D.B.; Mercadante, A.Z.; Mariutti, L.R.B. Marigold carotenoids: Much more than lutein esters. Food Res Int 2019, 119, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Hempel, J.; Schweiggert, R.M.; Ni, Y.; Carle, R. Carotenoids and Carotenoid Esters of Red and Yellow Physalis (Physalis alkekengi L. and P. pubescens L.) Fruits and Calyces. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 6140–6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiokias, S.; Gordon, M.H. Antioxidant properties of carotenoids in vitro and in vivo. Food Rev Int 2004, 20, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.J.; Sampson, J.; Candeias, L.P.; Bramley, P.M.; Rice-Evans, C.A. Antioxidant activities of carotenes and xanthophylls. FEBS Lett 1996, 384, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.J.; Lowe, G.M. Antioxidant and prooxidant properties of carotenoids. Arch Biochem Biophys 2001, 385, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, L.; Boehm, V. Antioxidant activity of β-carotene compounds in different in vitro assays. Molecules 2011, 16, 1055–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, G.; Liaaen-Jensen, S.; Pfander, H. Carotenoids. Volume 5: Nutrition and Health.; Birkhäuser-Verlag.: Berlin, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, F.; Peñaloza, P.; Vidal, A.; Cautín, R.; Castro, M. Seed Maturity and Its In Vitro Initiation of Chilean Endemic Geophyte Alstroemeriapelegrina L. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 464. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aros, D.; Barraza, P.; Peña-Neira, Á.; Mitsi, C.; Pertuzé, R. Seed Characterization and Evaluation of Pre-Germinative Barriers in the Genus Alstroemeria (Alstroemeriaceae). Seeds 2023, 2, 474–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; Cautín, R.; Castro, M. In Vitro Micropropagation of the Vulnerable Chilean Endemic Alstroemeria pelegrina L. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 674. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, M.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. Molecular and Metabolic Insights into Anthocyanin Biosynthesis for Spot Formation on Lilium leichtlinii var. maximowiczii Flower Petals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo, E.; Nagy, V.; Menchaca, D.; Deli, J.; Agócs, A. Changes in the Carotenoids of Zamia dressleri Leaves during Development. Plants 2024, 13, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurori, M.; Niculae, M.; Hanganu, D.; Pall, E.; Cenariu, M.; Vodnar, D.C.; Fiţ, N.; Andrei, S. The Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Cell-Protective Properties of Bioactive Compounds Extracted from Rowanberry (Sorbus aucuparia L.) Fruits In Vitro. Plants 2024, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuker, A.; Malik, A.; Punia, H.; McGill, C.; Sofkova-Bobcheva, S.; Mor, V.S.; Singh, N.; Ahmad, A.; Mansoor, S. Probing the Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Moringa oleifera under Ideal Germination Conditions. Plants 2023, 12, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsharairi, N.A. Experimental Studies on the Therapeutic Potential of Vaccinium Berries in Breast Cancer—A Review. Plants 2024, 13, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Release, S. Maestro, version 11.8. Schrodinger, LLC, New York. - References - Scientific Research Publishing.

- Kovarik, Z.; Radić, Z.; Berman, H.A.; Simeon-Rudolf, V.; Reiner, E.; Taylor, P. Acetylcholinesterase active centre and gorge conformations analysed by combinatorial mutations and enantiomeric phosphonates. Biochem J 2003, 373, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatonnet, A.; Lockridge, O. Comparison of butyrylcholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase. Biochem J 1989, 260, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howes, M.J.R.; Perry, N.S.L.; Houghton, P.J. Plants with traditional uses and activities, relevant to the management of Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive disorders. Phyther Res 2003, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuffrida, D.; Cacciola, F.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Stinco, C.M.; Dugo, P.; Oteri, M.; Mondello, L.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Free carotenoids and carotenoids esters composition in Spanish orange and mandarin juices from diverse varieties. Food Chem 2019, 300, 125139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Methods of Analysis, 21st Edition (2019) - AOAC International.

- Vargas-Arana, G.; Merino-Zegarra, C.; del-Castillo, Á.M.R.; Quispe, C.; Viveros-Valdez, E.; Simirgiotis, M.J. Antioxidant, Antiproliferative and Anti-Enzymatic Capacities, Nutritional Analysis and UHPLC-PDA-MS Characterization of Ungurahui Palm Fruits (Oenocarpus bataua Mart) from the Peruvian Amazon. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT - Food Sci Technol 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model Seeking for parameter-free double-hybrid functionals: The PBE0-DH model Accurate excitation energies from time-dependent density functional theory: Assessing the PBE0. Cit J Chem Phys 1999, 110, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, G.A.; Bennett, A.; Tensfeldt, T.G.; Al-Laham, M.A.; Shirley, W.A.; Mantzaris, J. A complete basis set model chemistry. I. The total energies of closed-shell atoms and hydrides of the first-row elements. J Chem Phys 1988, 89, 2193–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, A. Gaussian 09W Reference 2009.

- Greenblatt, H.M.; Kryger, G.; Lewis, T.; Silman, I.; Sussman, J.L. Structure of acetylcholinesterase complexed with (-)-galanthamine at 2.3 Å resolution. FEBS Lett 1999, 463, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachon, F.; Carletti, E.; Ronco, C.; Trovaslet, M.; Nicolet, Y.; Jean, L.; Renard, P.Y. Crystal structures of human cholinesterases in complex with huprine W and tacrine: Elements of specificity for anti-Alzheimer’s drugs targeting acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase. Biochem J 2013, 453, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussman, J.L.; Harel, M.; Frolow, F.; Oefner, C.; Goldman, A.; Toker, L.; Silman, I. Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: A prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science (80- ) 1991, 253, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silman, I.; Harel, M.; Axelsen, P.; Raves, M.; Sussman, J. Three-dimensional structures of acetylcholinesterase and of its complexes with anticholinesterase agents. In Proceedings of the Structure, Mechanism and Inhibition of Neuroactive Enzymes; Portland Press Limited., 1994; Vol. 22; pp. 745–749. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet, Y.; Lockridge, O.; Masson, P.; Fontecilla-Camps, J.C.; Nachon, F. Crystal Structure of Human Butyrylcholinesterase and of Its Complexes with Substrate and Products. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 41141–41147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallini, L.R.; Bastida, J.; Cortes, N.; Osorio, E.H.; Theoduloz, C.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G. Cholinesterase inhibition activity, alkaloid profiling and molecular docking of chilean rhodophiala (Amaryllidaceae). Molecules 2018, 23, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, W.; Day, T.; Jacobson, M.P.; Friesner, R.A.; Farid, R. Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. J Med Chem 2006, 49, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesner, R.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Repasky, M.P.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Halgren, T.A.; Sanschagrin, P.C.; Mainz, D.T. Extra precision glide: Docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J Med Chem 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PyMOL. Available online: pyomol.org (accessed on 24 October 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).