Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

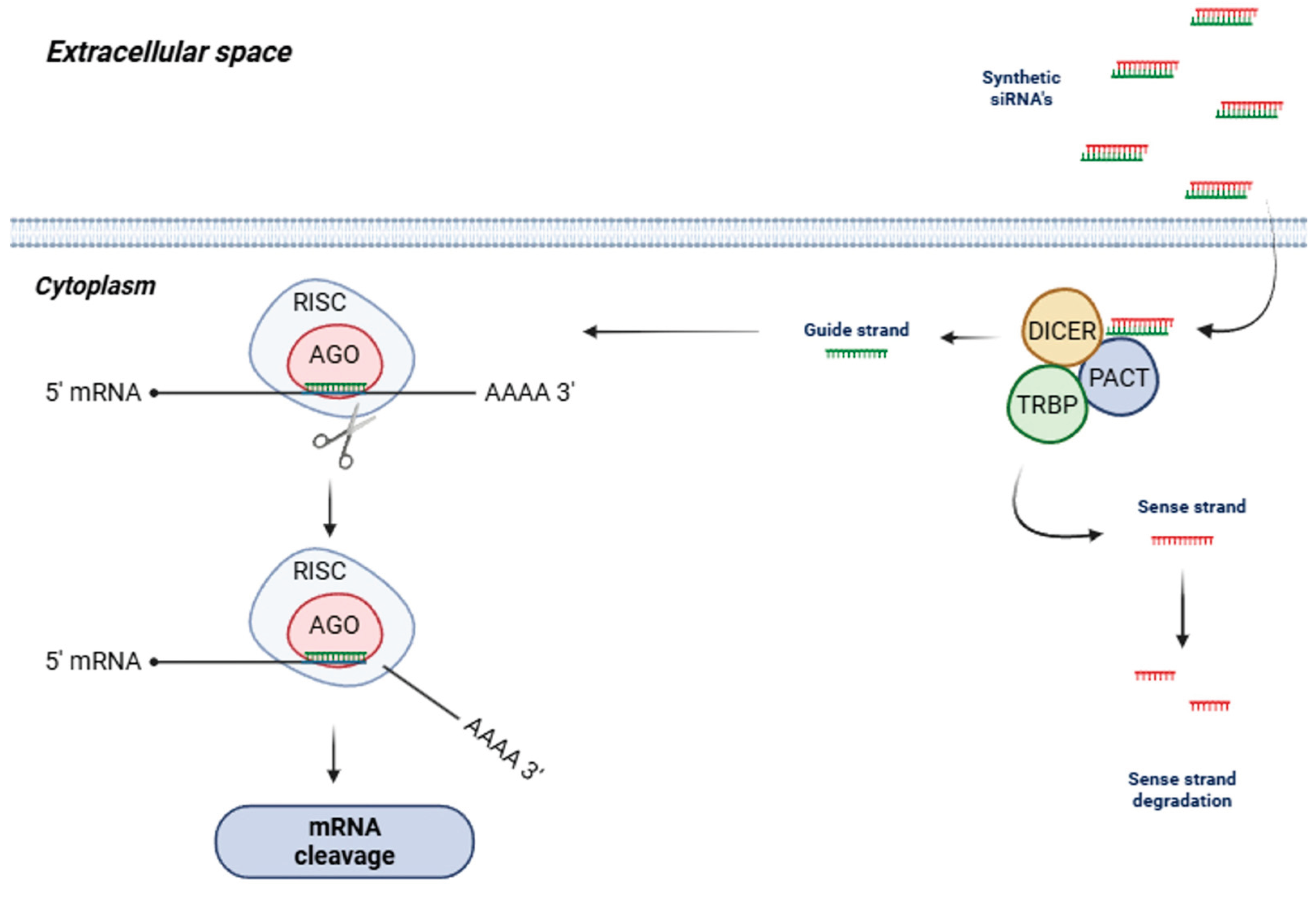

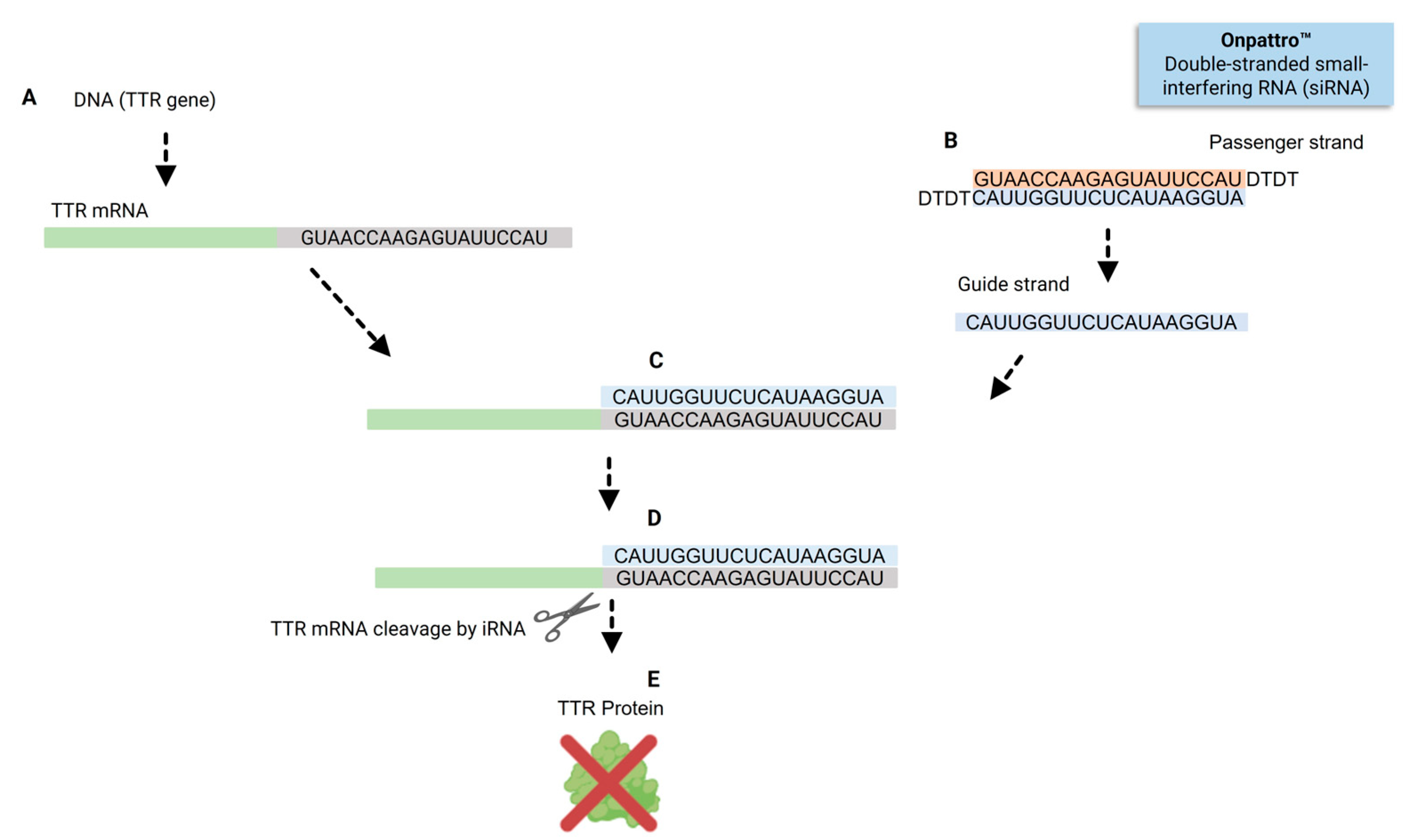

2. siRNAs – Concept and Mechanism of Action

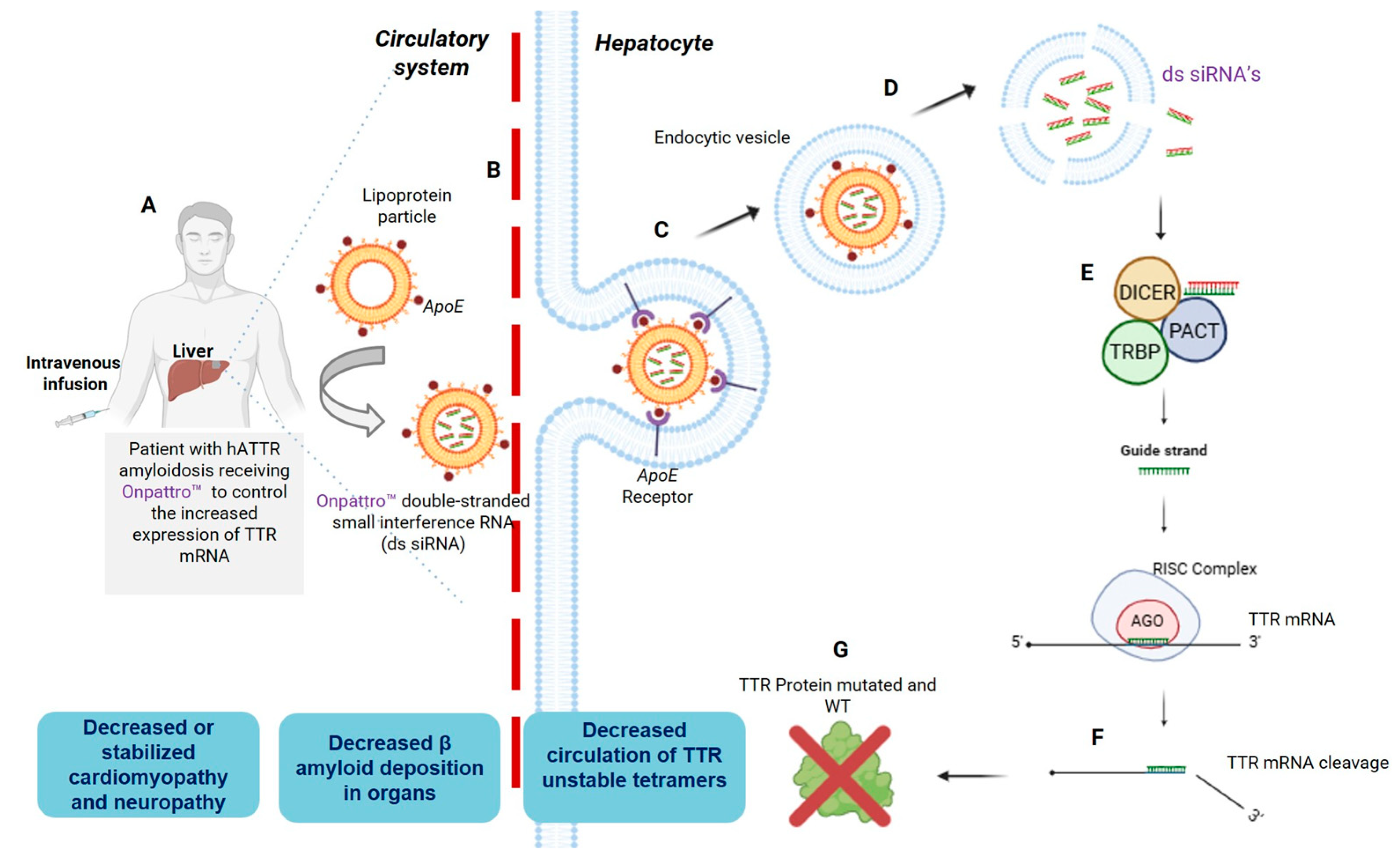

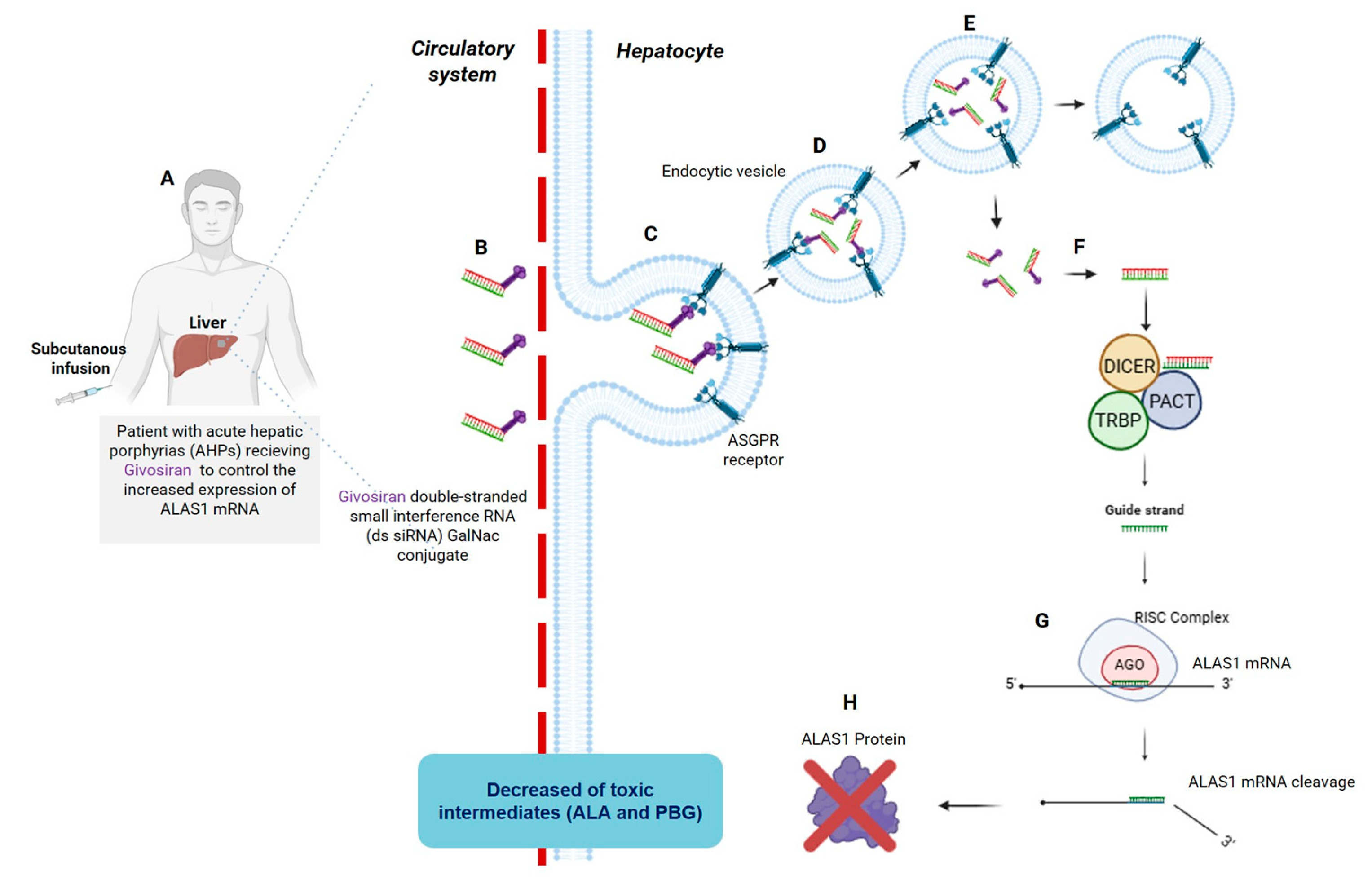

3. Reaching the Liver: The First Two FDA-Approved siRNAs, Patisiran and Givosiran

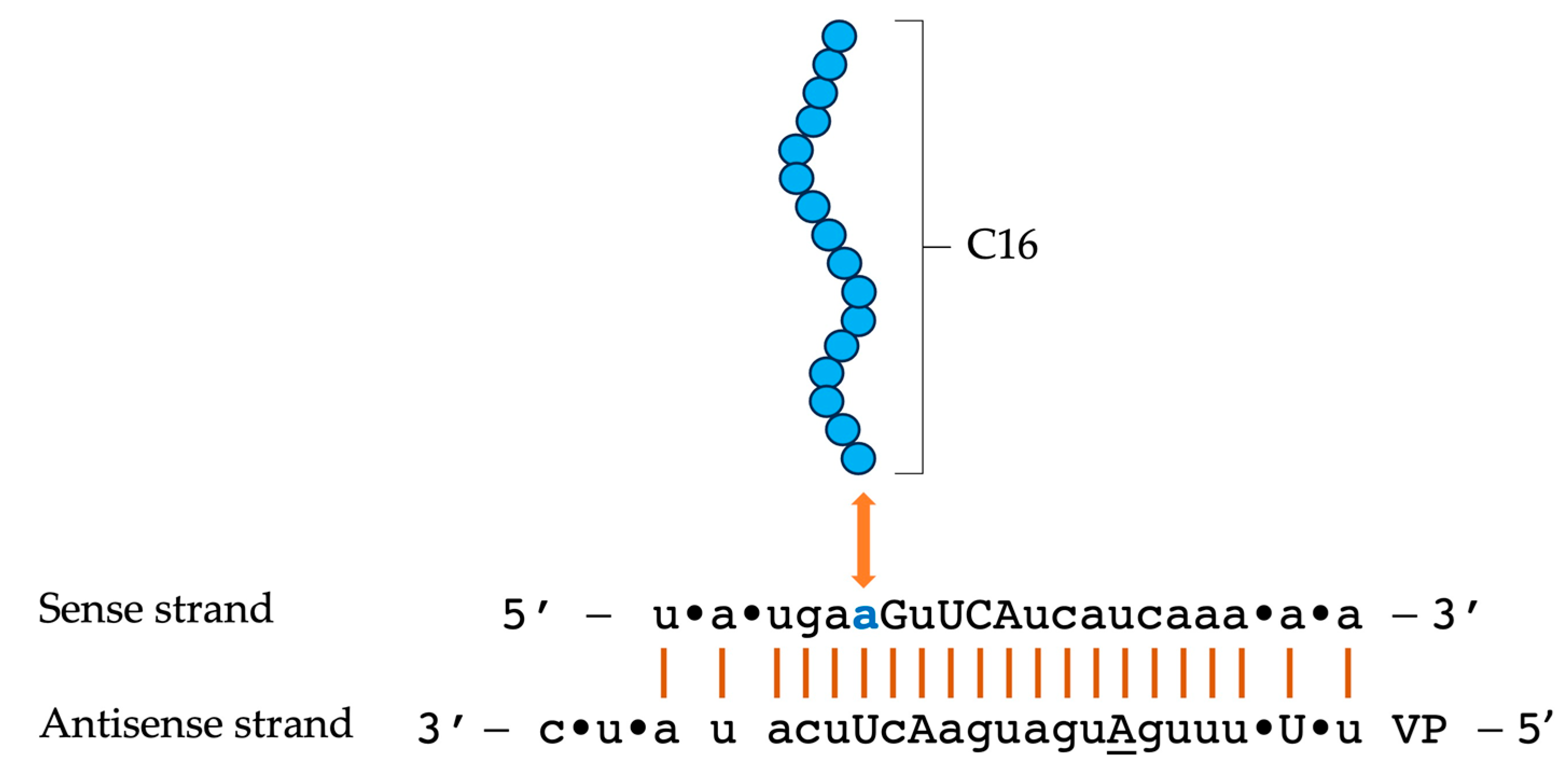

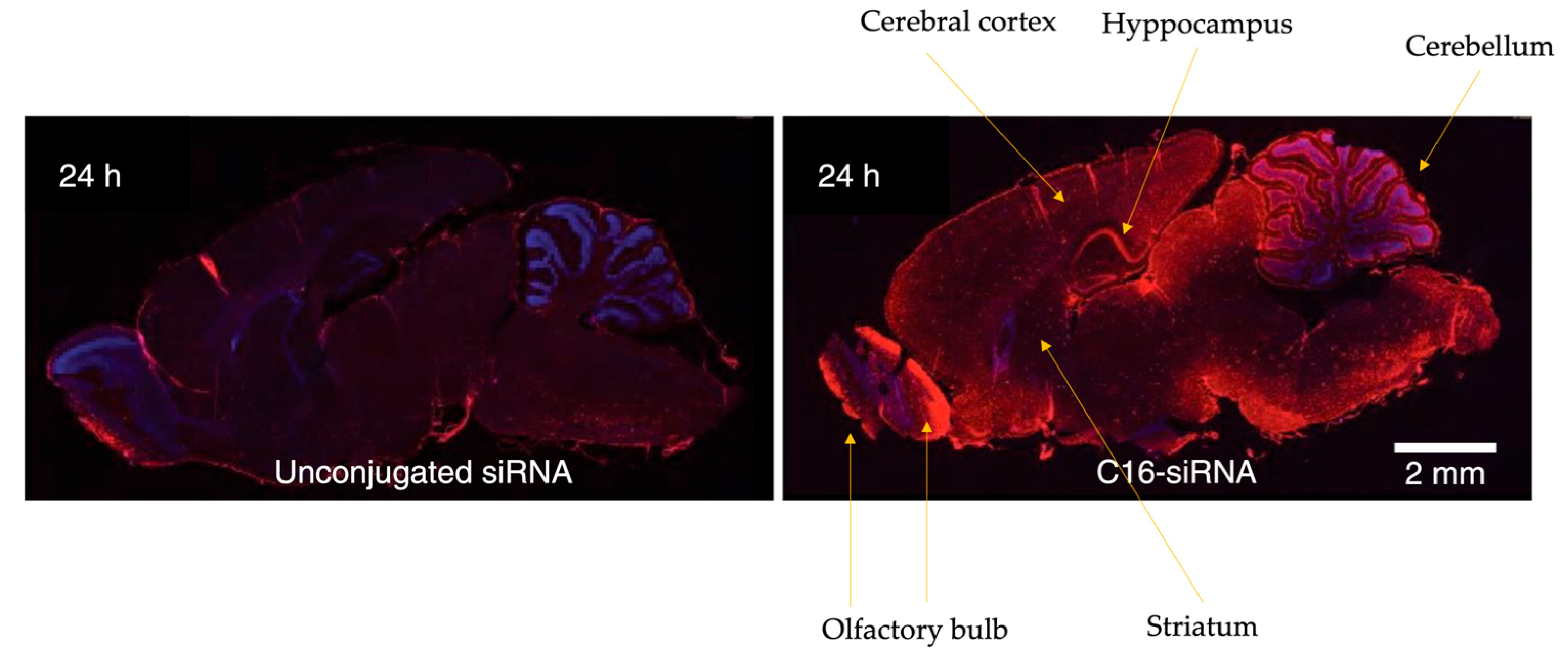

4. C16-siRNAs

4.1. Innovations in the Design of Brain-Delivered C16-siRNAs: A Functional Perspective

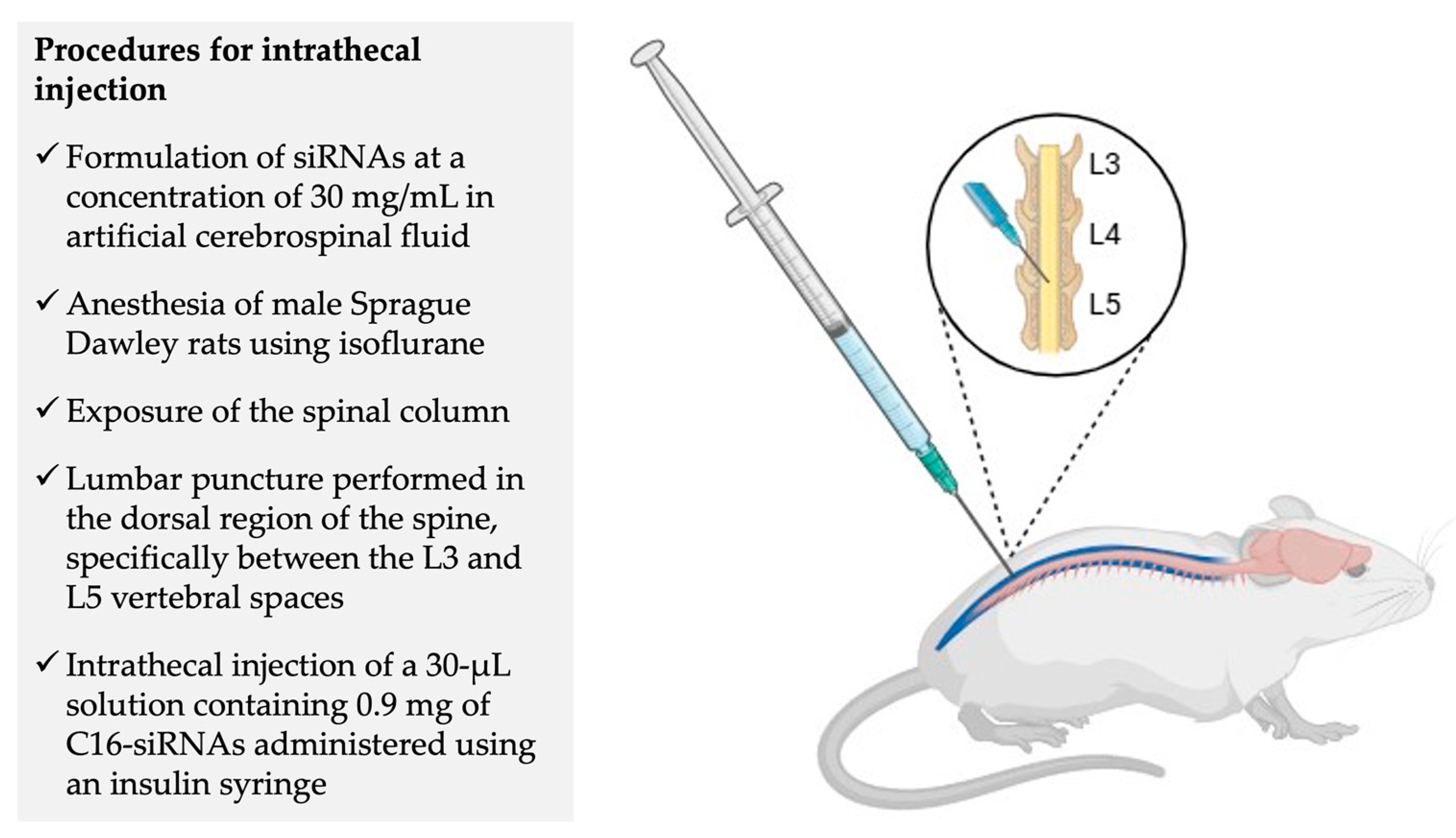

5. Phase 1 Clinical Trial – NCT05231785: Experimental Design and Preliminary Results

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aCSF | Artificial cerebrospinal fluid |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AEs | Adverse events |

| AGO2 Argonaute 2 enzyme | Argonaute 2 enzyme |

| AHP | Acute hepatic porphyria |

| ALA | δ-aminolevulinic acid |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| ARIA-H | Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities-haemosiderin |

| ASGPR | Asialoglycoprotein receptor |

| Aβ | β-amyloid |

| CAA | Cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| DEAF1 | Deformed epidermal autoregulatory factor-1 |

| ds-siRNA | Double-stranded siRNA |

| EOAD | Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GalNAc | N-acetylgalactosamine |

| GNA | Glycol nucleic acid |

| hATTR | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis |

| IT | Intrathecal |

| IV | Intravenous |

| LNP | Lipid nanoparticle |

| LRP1 | Lipoprotein receptor-related protein |

| MAD | Multiple ascending dose |

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| NfL | Neurofilament light chain |

| NFT’s | Neurofibrillary tangles |

| NHPs | Non-human primates |

| PACT | Protein activator of the interferon-induced protein kinase |

| PBG | Porphobilinogen |

| PD | Pharmacodynamics |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PK | Pharmacokinetics |

| PS | Phosphorothioate |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| ROS | Reative oxygen species |

| SAD | Single ascending dose |

| sAPPα | Soluble APPα |

| sAPPβ | Soluble APPβ |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| Sod1 | Superoxide dismutase 1 |

| TRBP | Transactivation response RNA-binding protein |

| TTR | Transthyretin |

| VLDLR | Very low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| VP | Vinylphosphonate |

| Wt | Wild type |

References

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Nixon, R.A.; Jones, D.T. Alzheimer Disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the Global Prevalence of Dementia in 2019 and Forecasted Prevalence in 2050: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madnani, R.S. Alzheimer’s Disease: A Mini-Review for the Clinician. Front Neurol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Villain, N.; Frisoni, G.B.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Sabbagh, M.; Cappa, S.; Bejanin, A.; Bombois, S.; Epelbaum, S.; Teichmann, M.; et al. Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations of the International Working Group. Lancet Neurol 2021, 20, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Ren, Y.; Yamazaki, Y.; Qiao, W.; Li, F.; Felton, L.M.; Mahmoudiandehkordi, S.; Kueider-Paisley, A.; Sonoustoun, B.; Arnold, M.; et al. Alzheimer’s Risk Factors Age, APOE Genotype, and Sex Drive Distinct Molecular Pathways. Neuron 2020, 106, 727–742.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B. A Brief History of the Progress in Our Understanding of Genetics and Lifestyle, Especially Diet, in the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2024, 100, S165–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard, L.T.; Christoffersen, M.; Frikke-Schmidt, R. Shared Risk Factors between Dementia and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.-F.; Jiang, T.; Tan, M.-S.; Tan, L.; Zhao, Q.-F.; Li, J.-Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.-T. Meta-Analysis of Modifiable Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015, jnnp-2015-310548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Q.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.-F.; Tan, M.-S.; Tan, L.; Xu, W.; Zhao, Q.-F.; Wang, J.; Jiang, T.; Yu, J.-T. Risk Factors for Predicting Progression from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016, 87, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Vemuri, P. Resistance vs Resilience to Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2018, 90, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkle, B.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Sims, R.; Bis, J.C.; Damotte, V.; Naj, A.C.; Boland, A.; Vronskaya, M.; van der Lee, S.J.; Amlie-Wolf, A.; et al. Genetic Meta-Analysis of Diagnosed Alzheimer’s Disease Identifies New Risk Loci and Implicates Aβ, Tau, Immunity and Lipid Processing. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsell, S.E.; Mock, C.; Fardo, D.W.; Bertelsen, S.; Cairns, N.J.; Roe, C.M.; Ellingson, S.R.; Morris, J.C.; Goate, A.M.; Kukull, W.A. Genetic Comparison of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Persons With Alzheimer Disease Neuropathology. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2017, 31, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prpar Mihevc, S.; Majdič, G. Canine Cognitive Dysfunction and Alzheimer’s Disease – Two Facets of the Same Disease? Front Neurosci 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panek, W.K.; Murdoch, D.M.; Gruen, M.E.; Mowat, F.M.; Marek, R.D.; Olby, N.J. Plasma Amyloid Beta Concentrations in Aged and Cognitively Impaired Pet Dogs. Mol Neurobiol 2021, 58, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, D.R.; Capetillo-Zarate, E.; Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H. The Development of Amyloid β Protein Deposits in the Aged Brain. Science of Aging Knowledge Environment 2006, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, B.T.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dickson, D.W.; Duyckaerts, C.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association Guidelines for the Neuropathologic Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2012, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montine, T.J.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Dickson, D.W.; Duyckaerts, C.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Mirra, S.S.; et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association Guidelines for the Neuropathologic Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Practical Approach. Acta Neuropathol 2012, 123, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Lopez, J.A.; Yachnis, A.T.; Prokop, S. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The Neuropathological Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurodegener 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, B.J.; Su, J.H.; Cotman, C.W.; White, R.; Russell, M.J. β-Amyloid Accumulation in Aged Canine Brain: A Model of Early Plaque Formation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging 1993, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czasch, S.; Paul, S.; Baumgärtner, W. A Comparison of Immunohistochemical and Silver Staining Methods for the Detection of Diffuse Plaques in the Aged Canine Brain. Neurobiol Aging 2006, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, K.A.; Sohrabi, H.R.; Rodrigues, M.; Beilby, J.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Taddei, K.; Criddle, A.; Wraith, M.; Howard, M.; Martins, G.; et al. Association of Cardiovascular Factors and Alzheimer’s Disease Plasma Amyloid-β Protein in Subjective Memory Complainers. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2009, 17, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verghese, P.B.; Castellano, J.M.; Garai, K.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Shah, A.; Bu, G.; Frieden, C.; Holtzman, D.M. ApoE Influences Amyloid-β (Aβ) Clearance despite Minimal ApoE/Aβ Association in Physiological Conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Guo, Z. Alzheimer’s Aβ42 and Aβ40 Peptides Form Interlaced Amyloid Fibrils. J Neurochem 2013, 126, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.X.; Zhao, Y.F.; Li, Y.M. Aβ42 and Aβ40: Similarities and Differences. Journal of Peptide Science 2015, 21, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, I.E.; Savage, J.E.; Watanabe, K.; Bryois, J.; Williams, D.M.; Steinberg, S.; Sealock, J.; Karlsson, I.K.; Hägg, S.; Athanasiu, L.; et al. Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis Identifies New Loci and Functional Pathways Influencing Alzheimer’s Disease Risk. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Recent Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Trials and New Drug Development Strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannopoulou, K.G.; Papageorgiou, S.G. Current and Future Treatments in Alzheimer Disease: An Update. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacorte, E.; Ancidoni, A.; Zaccaria, V.; Remoli, G.; Tariciotti, L.; Bellomo, G.; Sciancalepore, F.; Corbo, M.; Lombardo, F.L.; Bacigalupo, I.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Monoclonal Antibodies for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Published and Unpublished Clinical Trials. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2022, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanan, V.K.; Armstrong, M.J.; Choudhury, P.; Coerver, K.A.; Hamilton, R.H.; Klein, B.C.; Wolk, D.A.; Wessels, S.R.; Jones, L.K. Antiamyloid Monoclonal Antibody Therapy for Alzheimer Disease: Emerging Issues in Neurology. Neurology 2023, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Osse, A.M.L.; Cammann, D.; Powell, J.; Chen, J. Anti-Amyloid Monoclonal Antibodies for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. BioDrugs 2024, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, G.; Tuschl, T. Mechanisms of Gene Silencing by Double-Stranded RNA. Nature 2004, 431, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and Specific Genetic Interference by Double-Stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titze-de-Almeida, R.; David, C.; Titze-de-Almeida, S.S. The Race of 10 Synthetic RNAi-Based Drugs to the Pharmaceutical Market. Pharm Res 2017, 34, 1339–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.C.; Doudna, J.A. Molecular Mechanisms of RNA Interference. Annu Rev Biophys 2013, 42, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthew, R.W.; Sontheimer, E.J. Origins and Mechanisms of MiRNAs and SiRNAs. Cell 2009, 136, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushati, N.; Cohen, S.M. MicroRNA Functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2007, 23, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, P. Renaissance of Mammalian Endogenous RNAi. FEBS Lett 2014, 588, 2550–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketting, R.F. The Many Faces of RNAi. Dev Cell 2011, 20, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A.J.; MacRae, I.J. The RNA-Induced Silencing Complex: A Versatile Gene-Silencing Machine. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 17897–17901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; Doudna, J.A. A Three-Dimensional View of the Molecular Machinery of RNA Interference. Nature 2009, 457, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamore, P.D. RNA Interference: Big Applause for Silencing in Stockholm (Reprinted from Cell, Vol 127, Pg 1083-1086, 2006). Cell 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamore, P.D.; Tuschl, T.; Sharp, P.A.; Bartel, D.P. RNAi: Double-Stranded RNA Directs the ATP-Dependent Cleavage of MRNA at 21 to 23 Nucleotide Intervals. Cell 2000, 101, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, G.; Tuschl, T. Mechanisms of Gene Silencing by Double-Stranded RNA. Nature 2004, 431, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.I.E.; Zain, R. Therapeutic Oligonucleotides: State of the Art. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2019, 59, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Suhr, O.B.; Hund, E.; Obici, L.; Tournev, I.; Campistol, J.M.; Slama, M.S.; Hazenberg, B.P.; Coelho, T. First European Consensus for Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment of Transthyretin Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy. Curr Opin Neurol 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ledford, H. Gene-Silencing Technology Gets First Drug Approval after 20-Year Wait. Nature 2018, 560, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA - Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Treatments for Heart Disease Caused by a Serious Rare Disease, Transthyretin Mediated Amyloidosis.

- Nikam, R.R.; Gore, K.R. Journey of SiRNA: Clinical Developments and Targeted Delivery. Nucleic Acid Ther 2018, 28, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Brandão, P.R.; Titze-de-Almeida, S.S.; Titze-de-Almeida, R. Leading RNA Interference Therapeutics Part 2: Silencing Delta-Aminolevulinic Acid Synthase 1, with a Focus on Givosiran. Mol Diagn Ther 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullis, P.R.; Hope, M.J. Lipid Nanoparticle Systems for Enabling Gene Therapies. Molecular Therapy 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J.A.; Cullis, P.R.; van der Meel, R. Lipid Nanoparticles Enabling Gene Therapies: From Concepts to Clinical Utility. Nucleic Acid Ther 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Gonzalez-Duarte, A.; O’Riordan, W.D.; Yang, C.C.; Ueda, M.; Kristen, A. V.; Tournev, I.; Schmidt, H.H.; Coelho, T.; Berk, J.L.; et al. Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristen, A.V.; Ajroud-Driss, S.; Conceição, I.; Gorevic, P.; Kyriakides, T.; Obici, L. Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic for the Treatment of Hereditary Transthyretin-Mediated Amyloidosis. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titze-de-Almeida, S.S.; Brandão, P.R. de P.; Faber, I.; Titze-de-Almeida, R. Leading RNA Interference Therapeutics Part 1: Silencing Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis, with a Focus on Patisiran. Mol Diagn Ther 2020, 24.

- An, G. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of GalNAc-Conjugated SiRNAs. J Clin Pharmacol 2024, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, J.K.; Willoughby, J.L.S.; Chan, A.; Charisse, K.; Alam, M.R.; Wang, Q.; Hoekstra, M.; Kandasamy, P.; Kelin, A.V.; Milstein, S.; et al. Multivalent N -Acetylgalactosamine-Conjugated SiRNA Localizes in Hepatocytes and Elicits Robust RNAi-Mediated Gene Silencing. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, J.L.S.; Chan, A.; Sehgal, A.; Butler, J.S.; Nair, J.K.; Racie, T.; Shulga-Morskaya, S.; Nguyen, T.; Qian, K.; Yucius, K.; et al. Evaluation of GalNAc-SiRNA Conjugate Activity in Pre-Clinical Animal Models with Reduced Asialoglycoprotein Receptor Expression. Molecular Therapy 2018, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhave, D.G.; Sugandhi, V.V.; Jha, S.K.; Nangare, S.N.; Gupta, G.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Cho, H.; Hansbro, P.M.; Paudel, K.R. Neurodegenerative Disorders: Mechanisms of Degeneration and Therapeutic Approaches with Their Clinical Relevance. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 99, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poewe, W.; Seppi, K.; Tanner, C.M.; Halliday, G.M.; Brundin, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schrag, A.E.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson Disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymeropoulos, M.H.; Lavedan, C.; Leroy, E.; Ide, S.E.; Dehejia, A.; Dutra, A.; Pike, B.; Root, H.; Rubenstein, J.; Boyer, R.; et al. Mutation in the α-Synuclein Gene Identified in Families with Parkinson’s Disease. Science (1979) 1997, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabais Sá, M.J.; Jensik, P.J.; McGee, S.R.; Parker, M.J.; Lahiri, N.; McNeil, E.P.; Kroes, H.Y.; Hagerman, R.J.; Harrison, R.E.; Montgomery, T.; et al. De Novo and Biallelic DEAF1 Variants Cause a Phenotypic Spectrum. Genetics in Medicine 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassandri, M.; Smirnov, A.; Novelli, F.; Pitolli, C.; Agostini, M.; Malewicz, M.; Melino, G.; Raschellà, G. Zinc-Finger Proteins in Health and Disease. Cell Death Discov 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.S. Structural Classification of Zinc Fingers: SURVEY AND SUMMARY. Nucleic Acids Res 2003, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, N.D.; Chung, W.K.; Sarmiere, P.D. RNA Interference (RNAi)-Based Therapeutics for Treatment of Rare Neurologic Diseases. Mol Aspects Med 2023, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.; Huang, Y. Oligonucleotide Therapeutics for Neurodegenerative Diseases. NeuroImmune Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2025, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, C. Billion-Dollar Deal Propels RNAi to CNS Frontier. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won Lee, J.; Kyu Shim, M.; Kim, H.; Jang, H.; Lee, Y.; Hwa Kim, S. RNAi Therapies: Expanding Applications for Extrahepatic Diseases and Overcoming Delivery Challenges. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2023, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, K.A.; Langer, R.; Anderson, D.G. Knocking down Barriers: Advances in SiRNA Delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009, 8, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittrup, A.; Lieberman, J. Knocking down Disease: A Progress Report on SiRNA Therapeutics. Nat Rev Genet 2015, 16, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.M.; Nair, J.K.; Janas, M.M.; Anglero-Rodriguez, Y.I.; Dang, L.T.H.; Peng, H.; Theile, C.S.; Castellanos-Rizaldos, E.; Brown, C.; Foster, D.; et al. Expanding RNAi Therapeutics to Extrahepatic Tissues with Lipophilic Conjugates. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, V.; Maier, M. Behind the Paper - Expanding the Reach of RNAi Therapeutics with Next Generation Lipophilic SiRNA Conjugates Available online:. Available online: https://communities.springernature.com/posts/expanding-the-reach-of-rnai-therapeutics-with-next-generation-lipophilic-sirna-conjugates (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Soutschek, J.; Akinc, A.; Bramlage, B.; Charisse, K.; Constien, R.; Donoghue, M.; Elbashir, S.; Gelck, A.; Hadwiger, P.; Harborth, J.; et al. Therapeutic Silencing of an Endogenous Gene by Systemic Administration of Modified SiRNAs. Nature 2004, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterman, J.F.; Hall, L.M.; Coles, A.H.; Hassler, M.R.; Didiot, M.C.; Chase, K.; Abraham, J.; Sottosanti, E.; Johnson, E.; Sapp, E.; et al. Hydrophobically Modified SiRNAs Silence Huntingtin MRNA in Primary Neurons and Mouse Brain. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W. Chemical Modulation of SiRNA Lipophilicity for Efficient Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnylam Pharmaceutics, Inc. Alnylam. Delivery Platforms - C16 Conjugates Available online:. Available online: https://www.alnylam.com/our-science/sirna-delivery-platforms (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Titze-de-Almeida, R.; David, C.; Titze-de-Almeida, S.S. The Race of 10 Synthetic RNAi-Based Drugs to the Pharmaceutical Market. Pharm Res 2017, 34, 1339–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, L.L.; Owens, S.R.; Risen, L.M.; Lesnik, E.A.; Freier, S.M.; Mc Gee, D.; Cook, C.J.; Cook, P.D. Characterization of Fully 2’-Modified Oligoribonucleotide Hetero-and Homoduplex Hybridization Andnuclease Sensitivity. Nucleic Acids Res 1995, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layzer, J.M.; McCaffrey, A.P.; Tanner, A.K.; Huang, Z.; Kay, M.A.; Sullenger, B.A. In Vivo Activity of Nuclease-Resistant SiRNAs. RNA 2004, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Minakawa, N.; Matsuda, A. Synthesis and Characterization of 2′-Modified-4′-ThioRNA: A Comprehensive Comparison of Nuclease Stability. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerson, C.R.; Sioufi, N.; Jarres, R.; Prakash, T.P.; Naik, N.; Berdeja, A.; Wanders, L.; Griffey, R.H.; Swayze, E.E.; Bhat, B. Fully 2′-Modified Oligonucleotide Duplexes with Improved in Vitro Potency and Stability Compared to Unmodified Small Interfering RNA. J Med Chem 2005, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, T.P.; Kinberger, G.A.; Murray, H.M.; Chappell, A.; Riney, S.; Graham, M.J.; Lima, W.F.; Swayze, E.E.; Seth, P.P. Synergistic Effect of Phosphorothioate, 5′-Vinylphosphonate and GalNAc Modifications for Enhancing Activity of Synthetic SiRNA. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2016, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, D.J.; Brown, C.R.; Shaikh, S.; Trapp, C.; Schlegel, M.K.; Qian, K.; Sehgal, A.; Rajeev, K.G.; Jadhav, V.; Manoharan, M.; et al. Advanced SiRNA Designs Further Improve In Vivo Performance of GalNAc-SiRNA Conjugates. Molecular Therapy 2018, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janas, M.M.; Schlegel, M.K.; Harbison, C.E.; Yilmaz, V.O.; Jiang, Y.; Parmar, R.; Zlatev, I.; Castoreno, A.; Xu, H.; Shulga-Morskaya, S.; et al. Selection of GalNAc-Conjugated SiRNAs with Limited off-Target-Driven Rat Hepatotoxicity. Nat Commun 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, M.K.; Foster, D.J.; Kel’In, A.V.; Zlatev, I.; Bisbe, A.; Jayaraman, M.; Lackey, J.G.; Rajeev, K.G.; Charissé, K.; Harp, J.; et al. Chirality Dependent Potency Enhancement and Structural Impact of Glycol Nucleic Acid Modification on SiRNA. J Am Chem Soc 2017, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraszti, R.A.; Roux, L.; Coles, A.H.; Turanov, A.A.; Alterman, J.F.; Echeverria, D.; Godinho, B.M.D.C.; Aronin, N.; Khvorova, A. 5’-Vinylphosphonate Improves Tissue Accumulation and Efficacy of Conjugated SiRNAs in Vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, R.; Willoughby, J.L.S.; Liu, J.; Foster, D.J.; Brigham, B.; Theile, C.S.; Charisse, K.; Akinc, A.; Guidry, E.; Pei, Y.; et al. 5′-(E)-Vinylphosphonate: A Stable Phosphate Mimic Can Improve the RNAi Activity of SiRNA-GalNAc Conjugates. ChemBioChem 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; van der Flier, W.M.; Jessen, F.; Hoozemanns, J.; Thal, D.R.; Boche, D.; Brosseron, F.; Teunissen, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Jacobs, A.H.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer Disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2025, 25, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, F.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation and Microglial Activation in Alzheimer Disease: Where Do We Go from Here? Nat Rev Neurol 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trist, B.G.; Hilton, J.B.; Hare, D.J.; Crouch, P.J.; Double, K.L. Superoxide Dismutase 1 in Health and Disease: How a Frontline Antioxidant Becomes Neurotoxic. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, P.; Gagliardi, S.; Cova, E.; Cereda, C. SOD1 Transcriptional and Posttranscriptional Regulation and Its Potential Implications in ALS. Neurol Res Int 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunton-Stasyshyn, R.K.A.; Saccon, R.A.; Fratta, P.; Fisher, E.M.C. SOD1 Function and Its Implications for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Pathology: New and Renascent Themes. Neuroscientist 2015, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnylan Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Alnylam Reports Additional Positive Interim Phase 1 Results for ALN-APP, in Development for Alzheimer’s Disease and Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Available online:. Available online: https://investors.alnylam.com/press-release?id=27761 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Cohen, S.; Ducharme, S.; Brosch, J.R.; Vijverberg, E.G.B.; Apostolova, L.G.; Sostelly, A.; Goteti, S.; Makarova, N.; Avbersek, A.; Guo, W.; et al. Interim Phase 1 Part A Results for ALN-APP, the First Investigational RNAi Therapeutic in Development for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Meglio, M. Overviewing Encouraging Early-Stage Data on Mivelsiran, RNA Therapeutic for Alzheimer Disease: Sharon Cohen, MD, FRCPC.

- Cohen, S.; Ducharme, S.; Brosch, J.R. Single Ascending Dose Results from an Ongoing Phase 1 Study of Mivelsiran (ALN-APP), the First Investigational RNA Interference Therapeutic Targeting Amyloid Precursor Protein for Alzheimer’s Disease.; Philadelphia, PA, 2024;

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).