1. Introduction

The Kenyan government launched Social Health Authority (SHA) comprising Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF), Primary Healthcare Fund (PHP), and Emergency, Chronic, and Critical Illness Fund (ECCIF) in October 2024, with premiums funding SHIF and taxes funding PHP and ECCIF [

1]. SHA is a transition from the allegedly inequitable National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) into a more inclusive and universal health coverage (UHC)-oriented model[

2]. The government of Kenya leverages the growing digital infrastructure and social media use to promote SHA, even though similar initiatives in other African countries did not adequately address disinformation and a lack of clarity about health policy details[

2,

3]. Therefore, SHA’s digital strategy should be optimized to significantly improve contributions to SHIF.

Influencing the public with health information depends on people’s electronic health (eHealth) literacy, which enhances searching, retrieving, appraising, synthesizing, and correctly applying online health information for better health decision-making [

4]. For example, a Swedish cross-sectional analysis by Ahlstrand et al. found that high ehealth literacy among university students is associated with better health decision-making and greater engagement with digital health information [

5]. Similarly, Diviani et al. caution that limited awareness of credible online health information sources, which is attributed to low eHealth literacy, exposes digital health consumers to a high risk of invalidated information that may be false or misinterpreted [

6]. University students taking health-related courses presumably have high eHealth literacy levels compared to the general population due to their existing knowledge of health concepts [

7,

8]. Hence, they are expected to be better informed on health insurance compared to the general public.

Advanced knowledge of health insurance and eHealth literacy among health students in Kenya is crucial in SHA awareness strategies since families and communities of the students trust them for health information. Barasa et al. and Mugo agreed on the necessity of public health education initiatives to enhance health literacy and bridge the knowledge gaps that marred NHIF use [

9,

10]. As the reliance on digital communication for SHA awareness and information dissemination increases, health students can be used as the focal points to improve accessibility, retrieval, interpretation, and use of online health insurance information by communities in Kenya. Their health sciences background, community trust, and eHealth literacy can be leveraged to ensure that the general public, especially people in the informal sector, access the information they need to make informed decisions on contributing to SHIF.

More than 19 million Kenyans were enrolled for SHA as of February 2025, indicating a considerable reach [

11]. However, only 3.5 million people, primarily the formally employed, were actively contributing to SHIF since the premium is automatically deducted from their salaries [

12]. The informal sector may be avoiding SHA due to consumption of inaccurate SHA information from online sources due to low eHealth literacy levels. Liu et al. highlighted the critical role that eHealth literacy plays in the sustainability of structured healthcare models [

13]. Njuguna and Wanjala asserted that investing in health awareness initiatives contributes to the broader dissemination of accurate health insurance information, which increases public trust and participation in health insurance systems [

14]. Therefore, identifying intervention areas for improving eHealth literacy levels and health insurance knowledge is vital in the efforts to ensure every Kenyan consistently contributes to SHIF.

Literature review did not identify studies on the eHealth literacy of health students in Kenya and how it influences their knowledge of health insurance, yet health students require the least resources to train into health insurance crusaders when their eHealth literacy is high. The health students could be focal points to educate their community members about health insurance to address the characterized problem of most Kenyans having limited knowledge of the social health insurance benefits package [

15,

16]. Every village in Kenya most likely has an undergraduate student in health sciences whose health sciences background and passion in healthcare can be supplemented with better eHealth literacy to make them champions for social health insurance uptake through awareness. This study aimed to assess the levels of and relationship between eHealth literacy and SHA knowledge of undergraduate students pursuing health-related courses in Kenya toward identifying intervention areas to prepare them to be SHA crusaders in their communities especially in the informal sector, where health insurance uptake is low.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design: analytical cross-sectional study

Target and accessible population: Undergraduate students pursuing health-related courses in Kenyan universities were the target population. The accessible population comprised health undergraduate students on major social media platforms in Kenya.

Sample size estimation: The sample size was 120 estimated using G*Power 3.1.9.7 software with the following input parameters: statistical test = ordinal logistic regression, odds ratio = 2, probability of health insurance knowledge = 25%, significance level (α) = 0.05, power = 0.8, multicollinearity adjustment = 0.2, median rating = three (neutral), and variance = 1.

Ethical considerations: This study involved human participants, hence it was conducted while adhering to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki on the ethical conduct of research involving human participants including informed consenting and confidentiality. No personal identifiable information, contacts details, or IP addresses were collected during the survey to protect the respondents’ privacy. MUST Institutional Research Ethics Review Committee (MIRERC) reviewed the protocol for this study and approved it (MIRERC 018/2025). The National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI) granted research license number NACOSTI/P/25/418223 for this study after reviewing the protocol.

Recruitment: One researcher and research assistants across the universities in Kenya shared social media posts inviting health students to participate in the online survey and indicating the survey link on TikTok, X, Instagram, Facebook, Linkedin, and class emails. Additionally, the post was promoted on WhatsApp status to reach people aged 18 to 27 years, which is the age-group for most undergraduate students in Kenya.

Data collection tools: The survey tool comprised a demographics section, an eight-item eHealth literacy scale, and a 10-item adapted Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Health Insurance Knowledge Quiz. The eHealth literacy scale’s Cronbach’s alpha is 0.8 based on psychometric analysis among internet-based college students [

17], which shows good internal consistency and reliability for use among the university students accessible through social media platforms. The KFF Health Insurance Knowledge Quiz is user-friendly and it elicits reliable responses that represent a unidimensional construct of health insurance knowledge from university students [

18].

Data collection: The survey was distributed through Google Forms to potential respondents as a survey link accessible through

https://forms.gle/YEauT4cwpjMcnSAHA. The survey responses were viewed in Google sheet and downloaded into Excel for analysis.

Data analysis: Data were sorted, cleaned, and coded for analysis using SPSS Version 25. Data were summarized using median, interquartile range, and frequencies. The associations among the variables were determined using Chi-square test for trend. Spearman’s rank correlation measured the direction and strength of association between eHealth literacy and SHA/SHIF knowledge, controlling for age, gender, year of study, and socio-economic status. Multivariable logistic regression identified predictors of SHA/SHIF knowledge.

3. Results

TDemographic characteristics

A total of 207 health students responded to the survey between 31

st April 2025 and 31

st May 2025. Their mean age was 21.7 years (standard deviation = 2.1) while the age range was 18-31 years. Male and female students were almost equally represented (

Table 1). Participants were studying in 21 university comprising 12 public universities and nine private universities spread across Kenya.

Six major and 12 other undergraduate healthcare courses offered in Kenya were represented, with medicine, nursing, and medical laboratory science topping the list. The other courses include pharmacy, dentistry, physical therapy, and microbiology (

Figure 1).

Reliability of scales

Both the eHealth literacy scale and the SHA and SHIF knowledge scale had excellent reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.9 (95% CI: 0.88-0.92) and 0.96 (95% CI: 0.95-0.97), respectively. The inter-item correlations of the items ranged from 0.51 to 0.57 for the eHealth literacy scale and 0.70-0.72 for the SHA and SHIF knowledge scale, both indicating strong inter-item consistency.

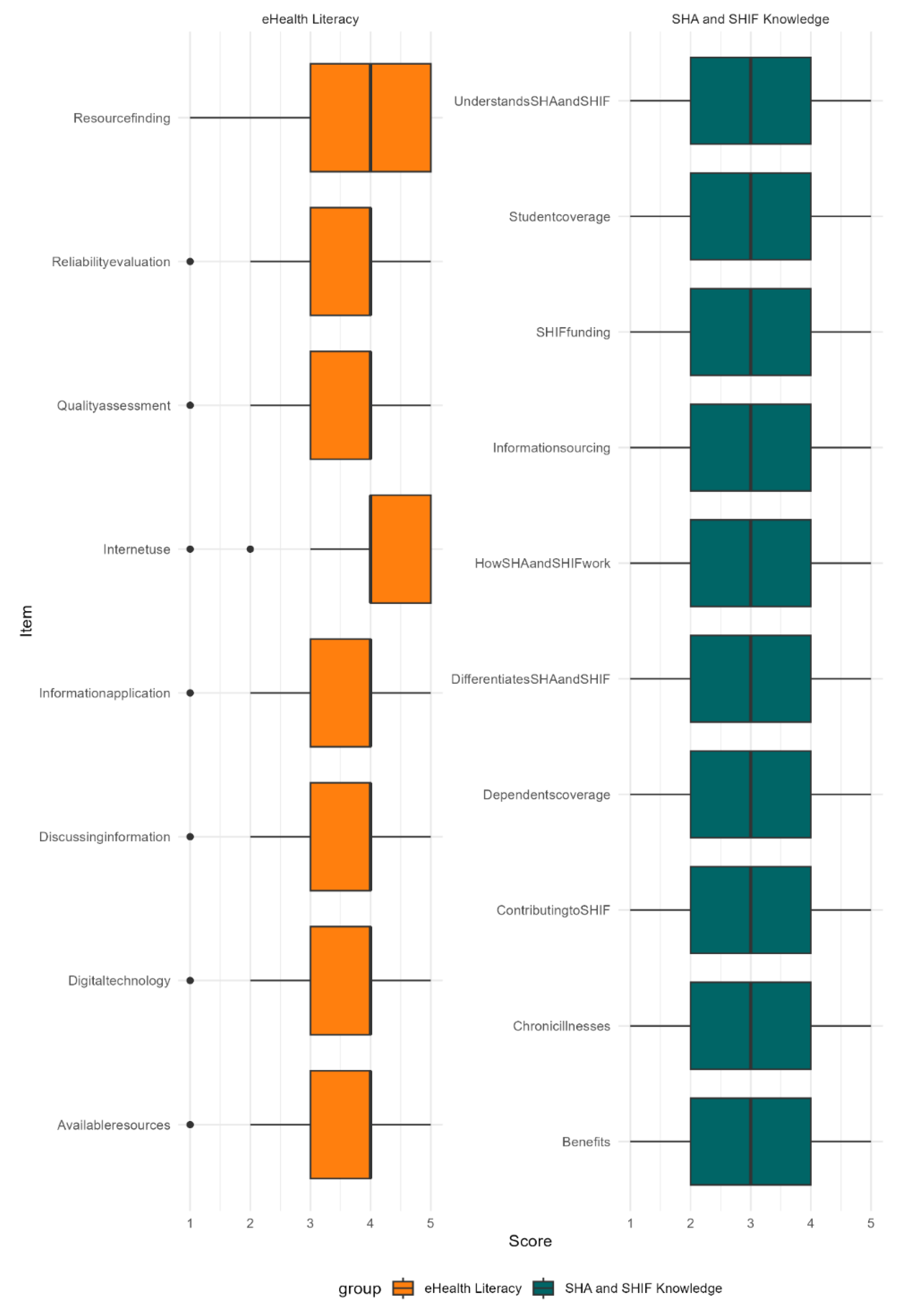

eHealth literacy levels

The median total eHealth literacy score was 31 (interquartile range = 5). The range of the total scores was 32 (minimum = 8, maximum = 40). Only 53.6% (n = 111) of them had high eHealth literacy levels, with 5.3% (n = 11) having low eHealth literacy levels. Comparisons of total eHealth literacy scores across gender, university, and course did not reveal any statistically significant differences.

However, comparisons of the total eHealth literacy scores across years of study revealed that at least one of the years had a different median from the rest (Kruskal-Wallis H = 12.4, df = 3, p = 0.006). Post hoc Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction showed that only year 4’s eHealth literacy scores (median = 4) were significantly different from year 3’s (median = 3.75, p = 0.02) and year 1’s (median = 3.75, p = 0.02), which may not translate to practical differences. Similarly, the eHealth literacy levels (high, modest, and low) were only statistically significantly associated with the course the students pursued (χ² = 22.1, df = 10, p-value = 0.01) and their year of study (χ² = 15.4, df = 6, p-value = 0.02).

Out of the eight individual items of the eHealth literacy scale, only knowledge of how to use the internet and find helpful health resources online were rated highly (

Figure 2).

Knowledge of SHA

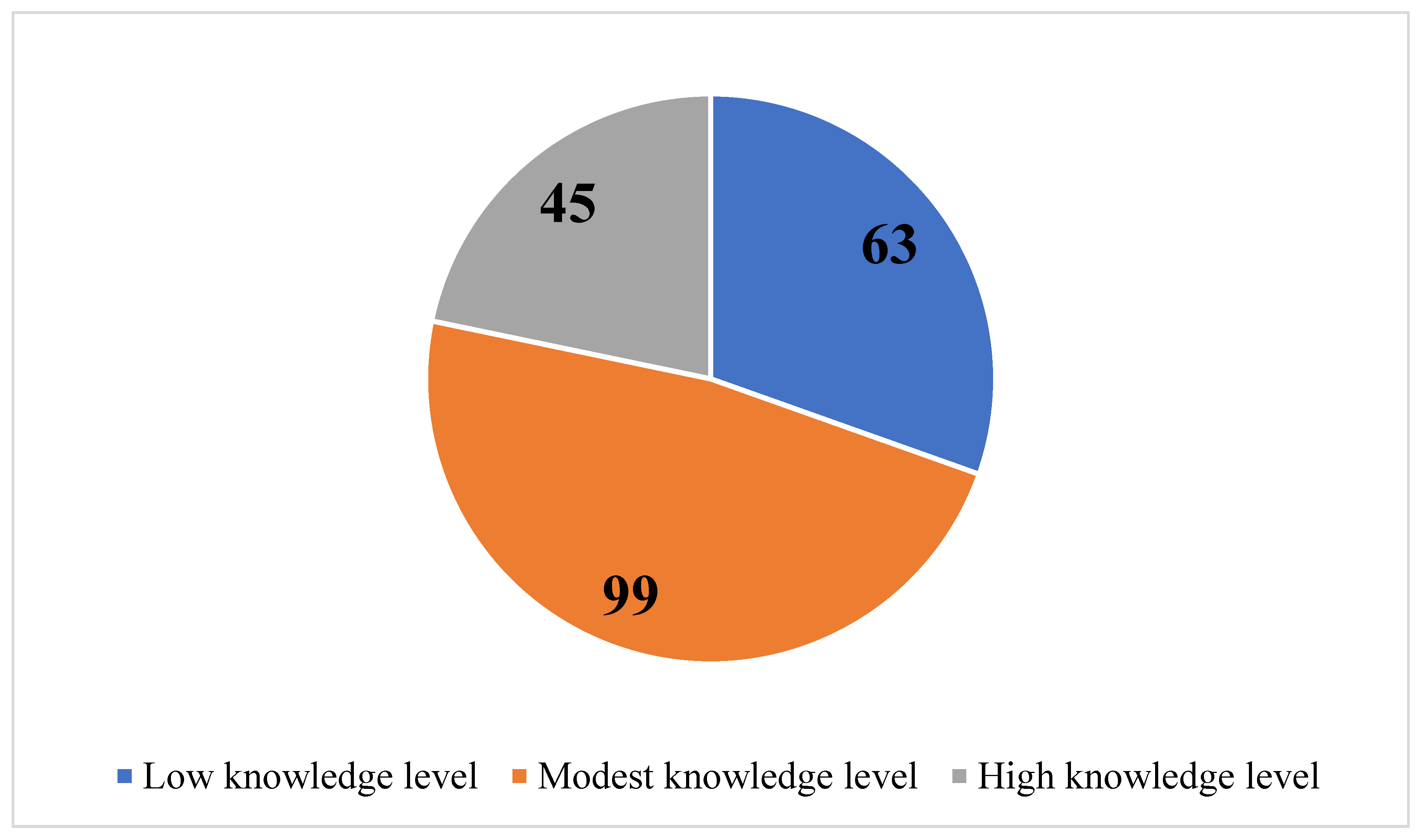

Only 9.2% (n = 19) of the 207 participants had never heard of SHA/SHIF. The median total score of knowledge of SHA was 30 (IQR = 14), with the minimum and maximum total scores being 10 and 50 respectively. Only 21.7% (n = 45) of the participants had a high level of knowledge of SHA.

A binary logistic regression was conducted to determine whether age, gender, university, course, and year of study predicted having heard of SHA/SHIF. The model was statistically significant for the course (χ² (1) = 9.9, p = 0.002) and age (χ² (1) = 5.0, p = 0.03). However, only the course of study statistically significantly (p = 0.004) predicted having heard of SHA/SHIF (OR = 1.45, 95% CI [1.1, 1.9]), with students in MBCHB, nursing, and MLS having higher odds of having heard of SHA compared to their counterparts in community health. Similarly, only comparisons across courses showed existence of course partakers with a statistically significant total score of SHA knowledge (Kruskal-Wallis H = 14.7, df = 5, p = 0.012). However, post hoc Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction showed that none of the courses’ learners were statistically significantly different median from the learners of the other individual courses.

Association between eHealth literacy and knowledge of SHA

eHealth literacy total scores were statistically significantly positively correlated with the total scores of the knowledge of SHA (Spearman’s rho = 0.36, p = 0.0001).

The SHA knowledge level and eHealth literacy level variables were recoded into two measures: low (a combination of low and modest) and high (retained as it was) to conduct binary logistic regression. Collinearity diagnostics were conducted using linear regression. The distribution of SHA knowledge level (high or low) in relation to age, gender, university, course, year, eHealth literacy level, and having heard of SHA were predicted using penalized logistic regression (Firth method) instead of binary logistic regression. This is because although variance inflation factors (VIF) values ranged from 1.0 to 1.6 and tolerance values ranged from 0.6 to 1.0, showing that levels of collinearity among the predictors were acceptable, cross-tabulation revealed that frequencies of the outcome were more than 10 in some categories of the predictors.

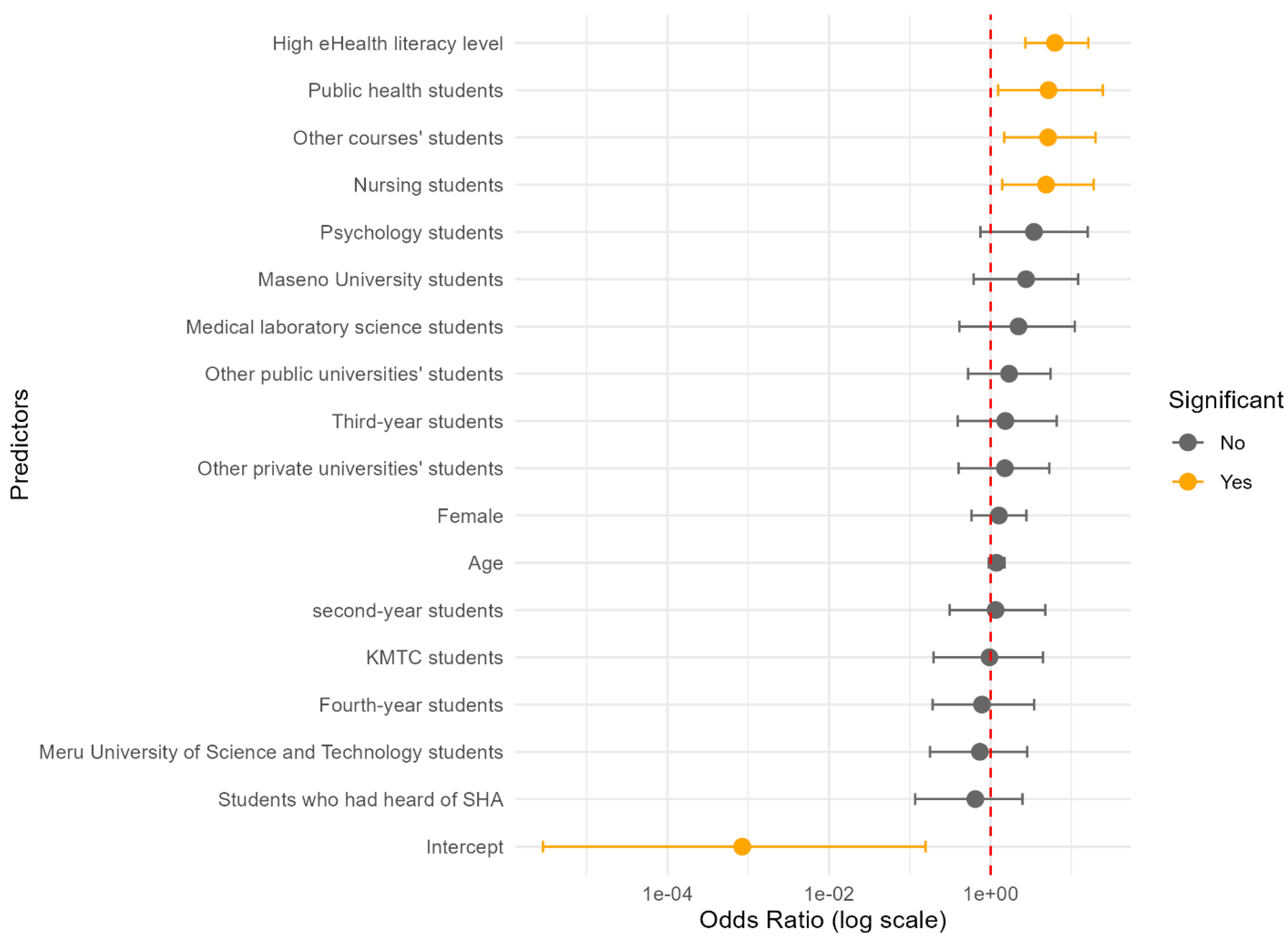

All the included predictors except age were categorical. The overall model was statistically significant χ² (17) = 43.15, p = 0.0005. Only eHealth literacy and partaking some course were significant predictors SHA knowledge level (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Numbers of health students in Kenya that self-related their knowledge of SHA as low, modest or high.

Figure 3.

Numbers of health students in Kenya that self-related their knowledge of SHA as low, modest or high.

Figure 4.

A forest plot of the odds ratios of predictors of SHA knowledge levels among university students in Kenya estimated using penalized logistic regression.

Figure 4.

A forest plot of the odds ratios of predictors of SHA knowledge levels among university students in Kenya estimated using penalized logistic regression.

Respondents with high eHealth literacy were six times more likely to have a high knowledge level of SHA compared to those with low eHealth literacy levels, controlling for age, gender, university, course, year of study, and having heard of SHA (

Table 2). Similarly, compared to respondents studying medicine, nursing, public health, and other courses’ students were approximately five times more likely to have a high level of SHA knowledge, controlling for all the other predictors in the model.

4. Discussion

eHealth literacy levels

About half of Kenya’s health students have suboptimal eHealth literacy levels, indicating that they may not be effectively differentiating credible information from gutter content about SHA [

1]. A similar study among young adults in four universities in Kenya reported a median eHealth literacy rating of 3.21 out of 5 [

2], which is slightly lower than the 3.88 observed in this study. In Ethiopia, two studies, one among all health students and the other specifically among nursing University students reported mean ratings of 3.58 and 3.15, respectively [

3,

4]. Therefore, health students have slightly higher eHealth literacy levels compared to other university students, but the levels are suboptimal considering the high rates of smartphone and internet penetration in Kenya.

eHealth literacy could be improving as health student progress from year 1 to year 4 but it remains sub-optimal even in year 4, indicating the need to supplement the health curriculums in Kenya with eHealth literacy concepts. Year four students have advanced education levels and age, which are known factors that influence eHealth literacy levels [

5,

6]. eHealth can be taught in tertiary education for healthcare workers of the future to enhance their readiness to work in an environment characterized by abundant eHealth information and technologies [

7]. Therefore, if eHealth is integrated in curriculums of health students in Kenya, their eHealth literacy levels can progressively improve more significantly as they transition from first year to fourth year.

The health students had suboptimal eHealth literacy levels in reliability evaluation, quality assessment, application, and discussion of online health information, as well as application of digital technology and knowing the available online health resources. Competencies to evaluate reliability of eHealth information are critical since the overall quality of health information is concerning [

8]. Health students should also have the capacity to assess the quality of online health information as for-profit organizations and individuals marketing products and services embrace health information-sharing as a marketing strategy [

9]. Since people are projected to increasingly seek health information online [

10], healthcare professional in training should prepare to discuss the credibility of various sources with patients and community members to optimize their online health-seeking behaviors. Therefore, the health students need improvements in all eHealth aspects.

Knowledge of SHA

Nearly 10% of health students self-reported having never heard of SHA or SHIF yet the government has been conducting both mainstream media and digital media sensitizations, showing that information penetration was subpar. NHIF awareness in the general population was 81.5% in four counties in Western Kenya in 2019 [

11], which aligns with the current findings since health insurance knowledge levels are expected to be higher among health students compared to the general population in Kenya that mainly comprises people in the informal sector [

12]. Knowledge of health insurance determines the rate of its uptake [

13]. Consequently, having 10% of trusted health advocates and prospective healthcare workers not knowing about health insurance means that the unawareness is likely to cascade to the community members who depend on them for health information [

14]. Since receiving health insurance instructions is associated with better knowledge and self-efficacy about health insurance [

15], the health insurance instructions can be integrated into the courses of undergraduate health students in Kenya to ensure all of them have the knowledge.

Having only a fifth of health students in universities in Kenya with high levels of SHA knowledge indicates a worrying situation considering that the proportion could be even smaller in the general population. A similar study in Nigeria reported high levels of knowledge of a university health insurance system among students in a Nigerian university but the detailed understanding of the services covered by the insurance was low [

16], indicating superficial knowledge. The high likelihood of SHA/SHIF knowledge among MBCHB, nursing, and MLS students compared to other health students could be due to their more intense interaction with the healthcare system in Kenya during practicums, resulting in better knowledge. However, learning from the clinical environments is unreliable since it depends on the approachability and supportiveness of clinical supervisors [

17]. Accordingly, health insurance education should be integrated into the coursework component of healthcare workers’ training for system sustainability and equity [

18], considering Kenya’s diverse clinical practicum settings.

Health students with health insurance knowledge are more likely to embrace advocacy about health insurance considering the knowledge-persuasion-decision-implementation-confirmation continuum of spreading ideas [

19]. Besides, health insurance literacy is associated with greater utilization of preventive and primary care services, which can result in better health outcomes overall [

20]. Learning from a Public Health Youth Ambassador Program that equipped students as community health workers in Virginia USA [

21], Kenyan students’ health insurance literacy can be optimized alongside equipping them with science communication skills to strategically position them as SHA ambassadors to support plain-language awareness initiatives among community health promoters and the general public in their local communities.

Association between eHealth literacy and knowledge of SHA

The positive correlation between eHealth literacy and knowledge of SHA reveals an opportunity to improve knowledge of SHA using eHealth literacy interventions. High eHealth literacy levels compared to low eHealth literacy levels were the main predictor of high levels of knowledge of SHA. High eHealth literacy is associated with better online health seeking behaviors [

2], which is likely to increase exposure to information about SHA. A cohort study conducted among Kenyatta University students in the school of business and the school of education reported that students whose phones had a health-related mobile app were more likely to have high levels of health awareness [

22]. Health students with high eHealth literacy levels can use the most recent evidence-based online materials not only to boost their health insurance knowledge but also to empower community members to make informed decisions on health insurance [

23]. Therefore, incorporating eHealth literacy into the curriculums of health courses in Kenya can enhance the sustainability of having health students as health insurance advocates.

The main limitation of this study is that the survey was self-reported, hence the ratings of eHealth literacy and health insurance knowledge may have been influenced by social desirability bias or self-enhancement bias. Fully anonymizing the survey and using validated tools reduced the risk of the biases. Another limitation is that the sample was not equally distributed across all the universities in Kenya, hence the findings may be more confidently generalized among Moi University, Meru University of Science and Technology, KMTC, and Maseno University; which individually had sizeable representations in the sample compared to other universities. Nevertheless, the results for other institutions were similar to the overall findings, indicating that the study paints a countrywide picture of eHealth literacy and health insurance knowledge among health students.

5. Conclusions

Despite the high penetration rate of smartphones and internet in Kenya, some health students have suboptimal eHealth literacy levels. Although eHealth literacy gradually improves as a health student progresses from first year to fourth year, the changes are marginal, indicating the need for interventions to optimize the changes. All the eHealth literacy aspects had nearly the same scores, hence interventions should cover all of them. Some health students have never heard of SHA while others are only modestly knowledgeable about it, hence interventions are needed to ensure all health students are equitably and adequately aware and knowledgeable of SHA. The clinical practicums could be contributing to the current health students’ knowledge of SHA but the practicums are unreliable since they present inequitable opportunities considering their dependence on the approachability and supportiveness of the supervisors. A program in the health curriculums in Kenya that strategically equips all health students with health insurance knowledge can prepare them to be better SHA advocates in their local communities. Since eHealth literacy emerged as the main predictor of SHA knowledge, it can be improved among health students to enhance their capacity as health insurance ambassadors. Qualitative research is required to determine why pursuing courses like nursing and public health predicts SHA/SHIF knowledge better than pursuing MBChB.

Author Contributions

F Conceptualization, E.A., M.A., and D.K.; Methodology, E.A., M.A., and D.K.; Validation, E.A., M.A., and D.K.; Formal Analysis, D.K.; Investigation, D.K.; Resources, E.A. and M.A.; Data Curation, E.A., M.A., and D.K.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, D.K.; Writing – Review & Editing, E.A., M.A., and D.K.; Visualization, D.K.; Supervision, D.K.; Project Administration, E.A.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Meru University of Science and Technology Institutional Research Ethics Review Committee (MIRERC) (MIRERC 018/2025, 04/4/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Mendeley Data at DOI:10.17632/t86f562rkd.1.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the School of Health Sciences at Meru University of Science and Technology for the support accorded when planning this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| MBCHB |

Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery |

| NHIF |

National Hospital Insurance Fund |

| KMTC |

Kenya Medical Training College |

| SHA |

Social Health Authority |

| SHIF |

Social Health Insurance Fund |

References

- W. Ng’ang’a, M. Mwangangi, and A. Gatome-munyua, “Health Reforms in Pursuit of Universal Health Coverage : Lessons from Kenyan Bureaucrats,” Heal. Syst. Reform, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 2406037, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Nduba-Banja, A. Mutisya, and A. A. Ahmed, “Kenya: Transition to the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF),” Bowmanslaw. Accessed: Mar. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://bowmanslaw.com/wp-admin/admin-ajax.php?action=generate_acf_pdf_insight&post_id=68939&nonce=bd3427e5b2.

- O. I. Eze, A. Iseolorunkanmi, and D. Adeloye, “The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in Nigeria: current issues and implementation challenges,” J. Glob. Heal. Econ. Policy, vol. 4, p. e20204002, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen et al., “The relationship between diabetes distress and eHealth literacy among patients under 60 years of age with diabetes: a multicenter cross-sectional survey,” BMC Health Serv. Res., vol. 25, p. 657, 2025. [CrossRef]

- I. Ahlstrand et al., “Health-promoting factors among students in higher education within health care and social work: a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data in a multicentre longitudinal study,” BMC Public Health, vol. 22, p. 1314, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Diviani, B. van den Putte, C. S. Meppelink, and J. C. M. van Weert, “Exploring the role of health literacy in the evaluation of online health information: Insights from a mixed-methods study.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 99, no. 6, pp. 1017–1025, 2016, [Online]. Available: https://pdf.sciencedirectassets.com/271173/1-s2.0-S0738399116X00067/1-s2.0-S073839911630026X/am.pdf.

- S. Abrha, F. Abamecha, D. Amdisa, D. Tewolde, and Z. Regasa, “Electronic health literacy and its associated factors among university students using social network sites (SNSs) in a resource-limited setting, 2022: cross-sectional study,” BMC Public Health, vol. 24, p. 3444, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. D. Mengestie, T. M. Yilma, M. A. Beshir, and G. K. Paulos, “EHealth Literacy of Medical and Health Science Students and Factors Affecting eHealth Literacy in an Ethiopian University: A Cross-Sectional Study,” Appl. Clin. Inform., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 301–309, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Barasa, P. Nguhiu, and D. McIntyre, “Measuring progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 3.8 on universal health coverage in Kenya,” BMJ Glob. Heal., vol. 3, p. e000904, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Mugo, “The impact of health insurance enrollment on health outcomes in Kenya,” Health Econ. Rev., vol. 13, p. 42, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health of Kenya, “Social Health Authority Implementation Progress.” Accessed: Apr. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.health.go.ke/social-health-authority-implementation-progress.

- M. Muoki, “Health experts blame gov’t over SHA failure, say rollout was rushed.” Accessed: Apr. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://citizen.digital/news/health-experts-blame-govt-over-sha-failure-say-rollout-was-rushed-n358317.

- X. Li and Q. Liu, “Social media use, eHealth literacy, disease knowledge, and preventive behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study on chinese netizens,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 22, no. 10, p. e19684, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. David and P. Wanjala, “A case for increasing public investments in health: raising public commitments to Kenya’s health sector,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://healthgarissa.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Healthcare-financing-Policy-Brief.pdf.

- J. S. Kazungu and E. W. Barasa, “Examining levels, distribution and correlates of health insurance coverage in Kenya,” Trop. Med. Int. Heal., vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 1175–1185, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Mulupi, D. Kirigia, and J. Chuma, “Community perceptions of health insurance and their preferred design features: Implications for the design of universal health coverage reforms in Kenya,” BMC Health Serv. Res., vol. 13, p. 474, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Nguyen, M. Moorhouse, B. Curbow, J. Christie, K. Walsh-Childers, and S. Islam, “Construct Validity of the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) Among Two Adult Populations: A Rasch Analysis,” JMIR Public Heal. Surveill., vol. 2, no. 1, p. e24, 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. G. James, M. David Miller, G. Nicolette, and J. W. Cheong, “Psychometric Evaluation of a 10-Item Health Insurance Knowledge Scale,” J. Nurs. Meas., vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 491–504, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Hasannejadasl, C. Roumen, Y. Smit, A. Dekker, and R. Fijten, “Health literacy and eHealth : Challenges and strategies,” JCO Clin Cancer Inf., vol. 6, p. e2200005, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Muturi, “eHealth literacy and the motivators for HPV prevention among young adults in Kenya,” Commun. Res. Reports, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 74–86, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. B. Shiferaw, E. A. Mehari, and T. Eshete, “eHealth literacy and internet use among undergraduate nursing students in a resource limited country: A cross-sectional study,” Informatics Med. Unlocked, vol. 18, no. May 2019, p. 100273, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee and S. H. Tak, “Factors associated with eHealth literacy focusing on digital literacy components: A cross-sectional study of middle-aged adults in South Korea,” Digit. Heal., vol. 8, pp. 1–9, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Hua, S. Yuqing, L. Qianwen, and C. Hong, “Factors influencing eHealth literacy worldwide: systematic review and meta-analysis.,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 27, p. e50313, 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. C. Schiza, M. Foka, N. Stylianides, T. Kyprianou, and C. N. Schizas, “Teaching and integrating eHealth technologies in undergraduate and postgraduate curricula and healthcare professionals’ education and training,” in Digital Innovations in Healthcare Education and Training, Academic Press, 2021, pp. 169–191. [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Chang, Y. Zhang, and J. Gwizdka, “The effects of information source and eHealth literacy on consumer health information credibility evaluation behavior,” Comput. Human Behav., vol. 115, p. 106629, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Kong, S. Song, Y. C. Zhao, Q. Zhu, and L. Sha, “Tiktok as a health information source: Assessment of the quality of information in diabetes-related videos,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 1–8, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Jia, Y. Pang, and L. S. Liu, “Online health information seeking behavior: A systematic review,” Healthcare, vol. 9, p. 1740, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Kamano et al., “Awareness and factors associated with NHIF uptake in four counties in western Kenya,” East Afr. Med. J., vol. 99, no. 2, p. 4593, 2022.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health of Kenya, and The DHS Program ICF, “Kenya demographic and health survey 2022 Volume 1,” Nairobi, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR380/FR380.pdf.

- T. K. Ngetich, W. K. Aruasa, R. K. Too, and F. Newa, “Uptake of healthcare insurance and its associated factors among patients seeking care at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Eldoret,” African J. Educ. Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 2, p. 66, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://ajest.org/index.php/ajest/article/view/77/80.

- Z. Gizaw, T. Astale, and G. M. Kassie, “What improves access to primary healthcare services in rural communities ? A systematic review,” BMC Prim. Care, vol. 23, p. 313, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. S. N. Upadhyay, L. K. Merrell, A. Temple, and D. S. Henry, “Exploring the impact of instruction on college students’ health insurance literacy,” J. Community Health, vol. 47, pp. 697–703, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. P. Uguru et al., “Tertiary institutions’ social health insurance program: Awareness, knowledge, and utilization for dental treatment among students of a Nigerian University,” Int. J. Med. Heal. Dev., vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 337–343, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Joan, B. Franklin, L. Joyce, and M. Justice, “Institutional factors influencing acquisition of clinical competencies among nursing undergraduates in government and private universities in Uganda Kintu,” J. Front. Humanit. Soc. Sci., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 14–26, 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Barr, H. Y. Gantz, G. Russell, and A. Hanchate, “Impact of health insurance education program on health care professional students: An interventional study,” J. Eval. Clin. Pract., vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 1029–1033, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Indimuli, N. Torm, W. Mitullah, L. Riisgaard, and A. W. Kamau, “Informal workers and Kenya’s National Hospital Insurance Fund: Identifying barriers to voluntary participation,” Int. Soc. Secur. Rev., vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 79–107, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. F. Yagi, J. E. Luster, A. M. Scherer, M. R. Farron, J. E. Smith, and R. Tipirneni, “Association of Health Insurance Literacy with Health Care Utilization: a Systematic Review,” J. Gen. Intern. Med., vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 375–389, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Tobe et al., “Public Health Youth Ambassador Program: Educating and empowering the next generation of public health leaders to build thriving communities,” J. Health Care Poor Underserved, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 132–142, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Ogweno and E. Gitonga, “The Effect of eHealth on Information Awareness on Non-Communicable Diseases Among Youths Between 18-25 Years in Nairobi County, Kenya,” East African J. Heal. Sci., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 15–28, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Brørs, M. H. Larsen, L. B. Hølvold, and A. K. Wahl, “eHealth literacy among hospital health care providers: a systematic review,” BMC Health Serv. Res., vol. 23, p. 1144, 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).