1. Introduction

In recent years, music generation models based on artificial intelligence have made remarkable progress. Deep learning models [

1,

2] have demonstrated outstanding capabilities in learning and generating complex music. Neural network models such as MusicVAE [

3] and music transformer models [

4] have proven their effectiveness in symbolic music generation by establishing models of music structures and generating coherent melody sequences. Transformer-based frameworks, for instance, Hybrid Learning Transformer [

5], which integrates music theory modules, and Structured Music Transformer [

6], which fuses style clustering for conditional generation. Meanwhile methods like Musika! [

7] and Compound Word Transformer [

8] continue to expand the boundaries of symbolic generation. However, despite these advancements, existing approaches still face notable limitations. Large language models (LLMs) applied to music such as MusicBERT [

9] and ChatMusician [

10] have demonstrated potential in tasks like melody generation and complex musical pattern modeling through pretraining on symbolic music data. However, these models often lack explicit modeling of musical structure during generation process, resulting in insufficient consistency in harmony, rhythm and style. Although diffusion-based models for symbolic music generation [

11,

12] can generate high-quality musical sequences, they also typically lack clear mechanisms to embed music theory rules. Rule-guided diffusion approaches [

13] introduce musical rules to guide generation, but they often suffer from limited flexibility and reduced diversity due to strict human design constraints. The contradiction between theoretical rigor and creative diversity in music algorithms is obvious in the existing hybrid models. Such as the hierarchical RNN proposed by Zixun et al. [

14] achieves end-to-end symbolic melody generation with coherent long-term structure via a hierarchical strategy. Although this model performs well in terms of global structure control, it still has the problem of rhythmic rigidity at the local note level, highlighting what can be described as an over-constraint problem in rule-based architecture of music generation. Conversely, the Structure-Informed Transformer [

15] bypasses explicit symbolic rules by embedding music-theoretical structures as relative positional encodings. This can enhance the rhythmic resolution, but due to its insufficient simulation of vertical sound constraints, it usually violates the voice part rules, such as parallel octaves. In contrast, DeepBach [

16], a neuro-symbolic model that integrates strict counterpoint rules with neural networks, achieves highly stylistic and accurate chorale generation, but strictly adheres to counterpoint rules, making it stylistically rigid and limited to Bach chorales. These strategies embody the approximation dilemma in music generation especially harmony generation, where purely statistical models often compromise harmonic coherence, and symbolic rule systems, though accurate in theory, restrict creative freedom through overly rigid constraints.

To overcome the above challenges, we propose a novel symbolic music generation framework Entropy-Regularized Latent Diffusion for Harmony-Constrained(ERLD-HC) that integrates a variational autoencoder(VAE)-diffusion hybrid architecture with entropy-regularized harmonic constraints. Specifically, we enhance the cross-attention mechanism within the diffusion process by injecting chord-aware representations learned via a Conditional Random Field (CRF) [

17], guided by entropy-based regularization. This design enables the model to incorporate soft, differentiable music-theoretic priors while maintaining flexibility and diversity in melodic generation. Unlike traditional rule-based systems or purely data-driven models, our approach introduces a learnable harmonic prior that improves the coherence and consistency of generated music. Our main contributions are as follows:

We propose a hierarchical generation architecture, ERLD-HC, which combines a VAE-based latent space representation with a denoising diffusion model, leveraging the strengths of both generative paradigms for symbolic music generation.

We introduce an entropy-guided CRF module into the cross-attention of the diffusion model, enabling continuous and interpretable harmonic control that integrates music theoretic knowledge into the generation process.

The significance of our method lies in its ability to reconcile two traditionally conflicting goals in music generation: the creative flexibility provided by neural networks and the strict rules of music theory. By embedding entropy-regularized, learnable music theoretic constraints into the cross-attention mechanism of the diffusion process, we establish a new deep learning framework that respects theoretical rigor while preserving expressive capacity.

2. Data Preprocessing

This paper adopts Musical Instrument Digital Interface(MIDI) files for the repre- sentation of music sequences. MIDI is a symbolic format that stores musical control and structural information rather than actual audio signals, making it suitable for digital composition and algorithmic analysis. A MIDI file typically consists of two main components: the header block, which includes metadata such as file type, number of tracks, and temporal resolution; and track blocks, which store a sequence of MIDI events. These events include: Note events (Note On/Off): indicating the start and end of a note, with associated pitch and timing information; Control changes: modifying parameters such as volume or modulation; Program change: switching instrument timbres; Meta-events: encoding additional information like time signatures, lyrics, and key.

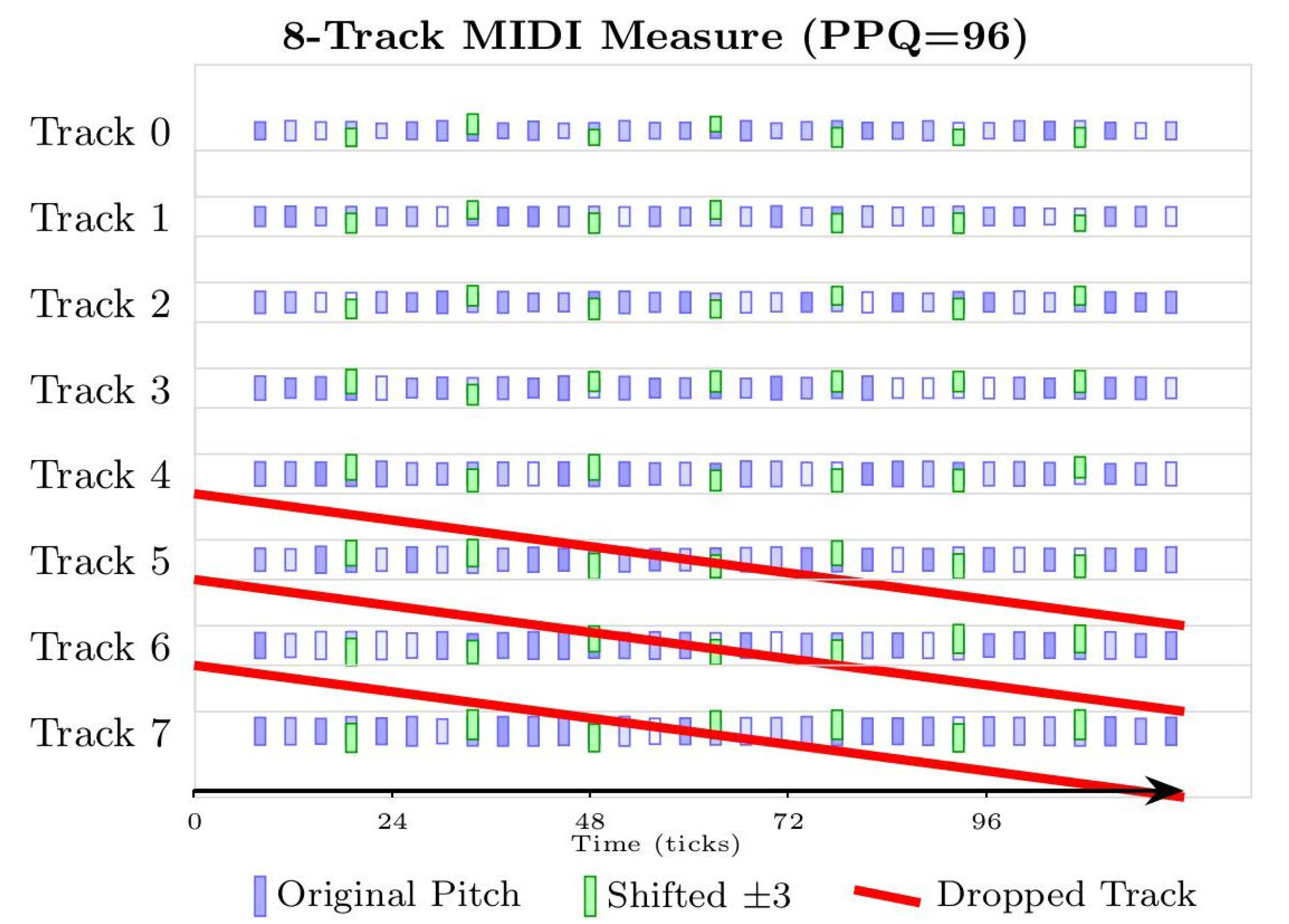

To facilitate the input of symbolic music into the model, this paper refers to MusicVAE to convert the note-level information such as duration, pitch, start time, end time, dynamics, etc in the MIDI file into a standardized data format. Specifically, the pitch in each MIDI file is encoded as 0-127. The intensity of the MIDI file is quantified into 8 intervals, each interval representing a specific volume range. Each volume change event sets a segment, in which all subsequent note-on events will use this set volume level until another volume change event occurs. The advancement of time is represented by 96 time offset events, and each event advances the current time by one quantified time step. Twenty-four time steps represent the length of a quarter note. In addition to the 128 different instrument sounds defined by the MIDI standard, a number channel for drums has also been added, with a total of 129 program selection events. The MIDI program number is set at the beginning of each track. The model we proposed models musical segments that contain up to 8 tracks, each track consisting of a single instrument, with a globally unified clock resolution of 96 pulses per quarter note(PPQ). To address the unbalanced style distribution in the dataset, this paper adopts a data enhancement strategy. To maintain the tonality constraint, the pitch is randomly offset by ±3 semitones, and the global dynamics are scaled by ±15% to simulate the dynamic changes in performance. One to two non-main melody tracks are randomly discarded to improve the model's robustness, as shown in

Figure 1.

3. Methods

3.1. Model Network Structure

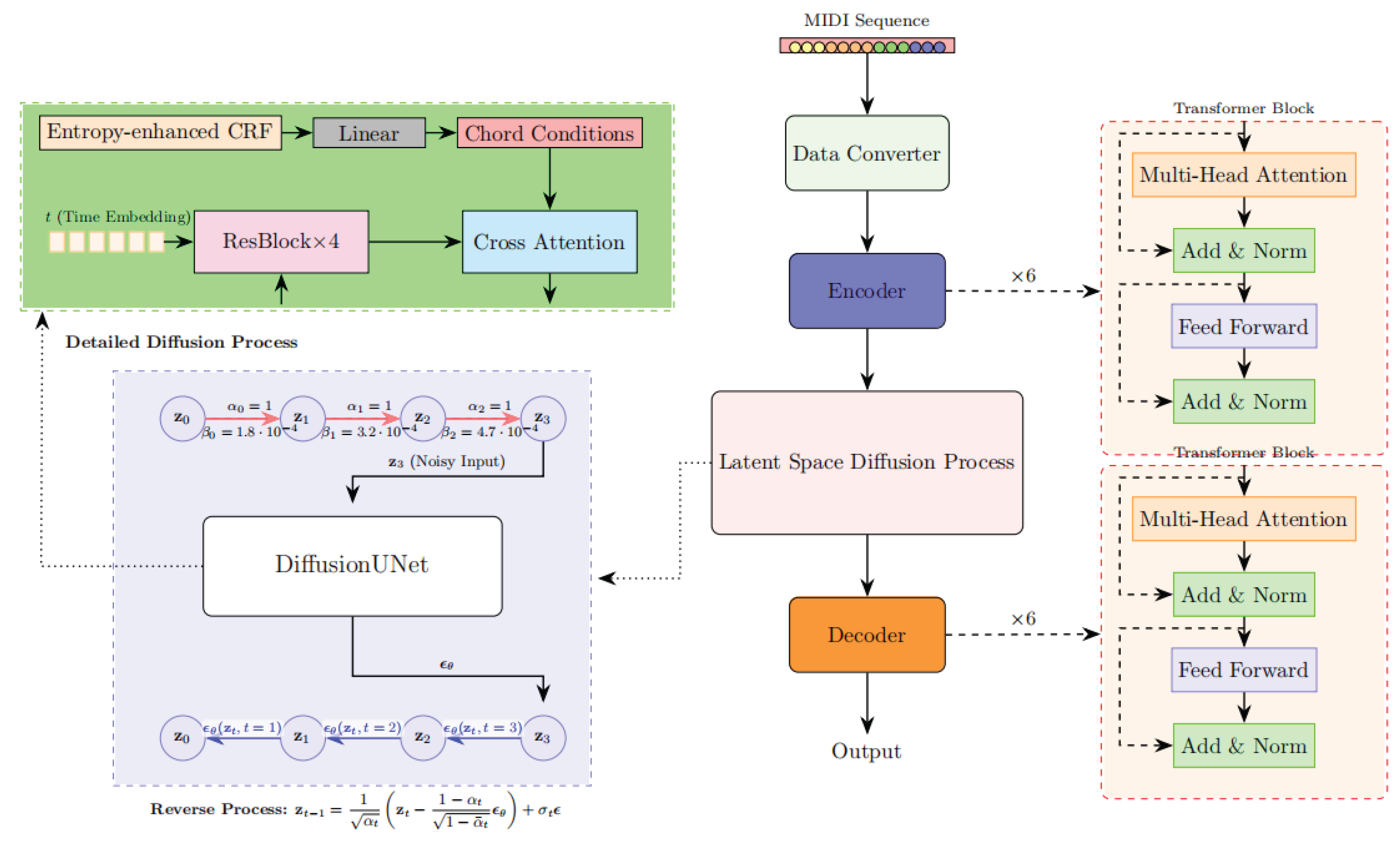

The overall architecture of the proposed ERLD-HC model is illustrated in

Figure 2. Our model adopts a Transformer-based VAE backbone. The encoder consists of 6 Transformer layers [

18], each comprising an 8-head self-attention mechanism (with a hidden dimension of 512) and a feedforward network (FFN) with an intermediate dimension of 2048. The encoder outputs the mean and variance of the latent variables, from which a 256-dimensional latent code z is sampled using the reparameterization trick.

A diffusion process is then applied in the latent space. In the forward process, Gaussian noise is added to the latent code z using a cosine noise schedule. In the reverse process, a UNet-based noise predictor [

19], composed of 4 residual blocks [

20] and attention layers, gradually denoises the latent representation.

To ensure the generated output conforms to symbolic music structures and emphasizes harmonic correctness rather than audio fidelity, we retain the VAE decoder to preserve constraint consistency throughout the generation. Decoder takes the latent representation produced by the diffusion module as input and generates pitch, duration, velocity, etc. Unlike autoregressive decoders, our design does not apply causal masking, allowing the model to leverage global context during decoding and enabling efficient generation of complete musical segments.

Importantly, we introduce an entropy-regularized CRF mechanism into the cross-attention layers of the diffusion network, enabling the model to integrate harmony-aware constraints in a learnable and differentiable manner during generation.

3.2. VAE-Encoder

Firstly, the MIDI file is converted into a tfrecord sequence. Each notesequence is split at the time-change boundaries, and sequences that do not meet predefined conditions are filtered out based on parameters. A data converter is used to convert the sequences into tensors, which are subsequently fed into the VAE encoder. As shown in Equation (1),

represents a 128-dimensional feature vector extracted from the original MIDI sequence, containing quantized pitch, timing and dynamic information.

3.3. Latent Diffusion

Encoder output

is directly used as the initial latent variable in the diffusion process. The diffusion is divided into the forward noise-adding process and the reverse denoising process. In the forward noise-adding process, Gaussian noise [

21] is gradually added to obtain

from

, as defined in Equation (2):

Here,

denotes the improved cosine-based noise schedule.The noise scheduling coefficient

is used to control the intensity of noise addition. In the initial stage, the original signal is largely preserved, and complete noise reduction is achieved in the final stage. The cosine function changes gently within the interval

, avoiding sudden changes in linear scheduling at both ends. It is suitable for music signals because the harmonic structure needs to be smoothly disrupted. Meanwhile, stable scheduling is conducive to the effective transmission of CRF constraints. The scheduling function is defined as Equation (3):

denotes the current timestep, and

is the total number of diffusion steps. The offset

, the reverse denoising process uses a trained UNet to predict the noise

, gradually restoring

from

, as shown in Equation (4):

is the noise predicted by UNet, see blue arrow in

Figure 2. The core modules of the UNet architecture include 4 resblocks and cross-attention. The chord sequence output by entropy-enhanced CRF is mapped to a 128-dimensional condition vector through linear projection. In each denoising step of the diffusion process, the chord features generated by CRF are introduced through cross-attention, thereby constraining the generation results at the latent space level. It enables dynamic alignment between latent note sequences and chord conditions. Compared with simple concatenation, cross-attention can retain the temporal relationship between the two sequences and avoid information confusion. At each layer of UNet, the diffusion intermediate noise

is used as the Query, and the chord condition vector

c is used as the Key and Value. Condition control is achieved through Equation (5):

is the learnable projection matrix. Cross-attention integrates the attended output into the residual connection and then pass through LayerNorm(LN), the process is shown as Equation (6):

is the output projection matrix. Cross-attention dynamically highlights relevant chord features at each denoising step. This weighted fusion ensures harmonic consistency without disrupting the inherent noise-prediction dynamics of the diffusion model. LN and residual connections stabilize training, as the attention output is added to the original feature map before normalization. Crucially, this approach outperforms concatenation by preserving long-range dependencies: chords influence note generation adaptively, even when sequences are non-aligned. We use a 128-dimensional projection to preserve harmonic context while maintaining computational efficiency, avoiding unnecessary overparameterization. In order to enable the model to utilize external information such as harmony on features at different levels, cross-attention layers are introduced within each intermediate UNet block.

3.4. Chord Inference Based on Entropy-Regularized CRF

In the music generation model, chord inference critically determines the structural coherence and theoretical rationality of the synthesized MIDI signals. Traditional probabilistic models such as Hidden Markov models [

22] are limited by the assumption of local transitions, making them inadequate for modeling long-range harmonic dependencies and tonal structures. To overcome this limitation, we adopt a CRF framework enhanced by entropy-based feature functions [

23], which encode both data-driven and theory-aware properties into a unified probabilistic model.

CRF is a discriminative model used for sequence labeling tasks [

24], which calculates the conditional probability distribution over label sequences given an observation sequence. Unlike traditional models, CRF allows the incorporation of complex, dependent feature functions. We reformulate these functions using entropy measures to capture harmonic consistency, tonal stability, and melodic smoothness in a statistically grounded manner.

Given an input sequence of unit-normalized pitch class vectors

, where each vectors

is derived from weighted pitch occurrences in a bar, the conditional probability of a chord label sequence is defined as:

Here, denotes the k-th entropy-based feature function, and is its learnable weight. is the partition function that normalizes the distribution. We propose the following 4 types of entropy-based feature functions.

3.4.1. Pitch Class Entropy(PCE)

To evaluate how concentrated a pitch vector

is around certain chord tones, we define a pitch entropy function as Equation (8):

Where is the probability of pitch class in . A lower entropy indicates tonal concentration, which is more likely to match standard chord structures. This function penalizes incoherent or overly scattered pitch distributions.

3.4.2. Chord Transition Entropy(CTE)

The Instead of binary chord change indicators, we introduce a statistical prior over chord transitions. Given empirical transition probabilities

, we define in Equation (9):

This penalizes rare or disharmonious transitions, enforcing learned chord progre- ssions typical in tonal music.

3.4.3. Key Matching Entropy(KME)

To assess the alignment between the current chord and its key context

,we define a key-alignment entropy in Equation (10):

Where if pitch class in belongs to the diatonic scale of , and 0 otherwise. A low value implies the chord is harmonically consistent with the current key.

3.4.4. Tonal Entropy(TE)

To avoid erratic key modulations, we introduce a penalty on tonal inconsistency across time as follows:

Here is the entropy of the key distribution over the full sequence. High entropy implies frequent modulations, which are discouraged unless musically justified.

All weights

are optimized by maximizing the log-likelihood of the correct chord sequence in Equation (13):

Through this entropy-regularized CRF framework, the model not only captures high-level music theory constraints but also allows flexible local variation, achieving a balance between theoretical soundness and creative expression. The entropy-regularized CRF outputs harmonically informed chord sequences, which serve as explicit conditions for guiding the diffusion-based music generator.

3.5. VAE-Decoder

After the denoising process of the diffusion model, the final denoised latent sequence encapsulates the musical structure and harmonic information conditioned by prior chord-aware modeling. The decoder is designed to transform this latent representation into structured event sequences, which are then converted into symbolic MIDI format.

We adopt a Transformer-based decoder to parameterize the output distribution over musical event tokens, as shown in Equation (14):

Here, denotes the event token at time step , and the decoder outputs a probability distribution over the vocabulary of discrete musical events (e.g., note-on, note-off, velocity, duration). The output event sequence is finally post-processed into a structured MIDI format using a rule-based event parser, ensuring compliance with MIDI standards. This decoder design assumes that harmonic and stylistic constraints have already been modeled in the latent space during the diffusion process. Therefore, no additional conditional input is introduced at the decoding stage, promoting architectural simplicity and computational efficiency.

3.6. Loss Function Design

To enable global optimization and ensure the structural coherence between generated note sequences and harmonic constraints, this study adopts a joint training strategy. Specifically, the VAE, diffusion, and CRF modules are integrated into an end-to-end framework, and their losses are jointly optimized.

The overall loss is defined as:

Where and are trade-off coefficients used to balance the contribution of each component.

3.6.1. VAE Loss

To learn structured latent representations from MIDI data, the VAE is trained to maximize the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) defined as:

where

denotes the input note sequence,

is its latent embedding, and the loss balances reconstruction fidelity and latent regularization through the Kullback Leibler(KL) divergence.

3.6.2. Diffusion Model Loss

After obtaining the latent representation from the VAE, a diffusion model is trained to progressively denoise and synthesize structured embeddings. The objective is to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) [

25] between the sampled noise

and the predicted noise

, as shown in Equation (17):

Where denotes the latent variable at diffusion step , and is the noise predicted by the model.

3.6.3. CRF Loss

The CRF module is separately trained for chord inference based on the note sequences generated by the VAE and diffusion modules. The CRF is optimized by maximizing the conditional log-likelihood of the true chord sequence, as shown in Equation (18):

Here, denotes the pitch-class feature at time , is the corresponding chord label, represents the trainable feature functions, and is the partition function ensuring a valid probability distribution.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset and Parameter Settings

This paper adopts the LMD-matched dataset, a refined subset of the Lakh MIDI Dataset that is aligned with the Million Song Dataset via audio fingerprint matching, resulting in significantly improved alignment quality compared to LMD-full. The dataset contains 45,129 high-quality MIDI files spanning various genres, with pop, rock, and jazz. For harmonic annotation, chord labels were automatically inferred using the music21 toolkit. During preprocessing, MIDI files were segmented into 4/4 bars, discarding bars not equal to four quarter notes. Bars containing more than 8 tracks or any track exceeding 64 events were also excluded. Data augmentation involved ±3 semitone modulation and filtering of invalid pitches. A 50-step cosine noise schedule was used in the diffusion process, with training conducted on an RTX 3090 Ti using FP16 mixed precision. A two-stage evaluation framework was employed to assess model performance under both free and conditional generation scenarios.

4.2. Chord Confusion Analysis of CRF Strategy

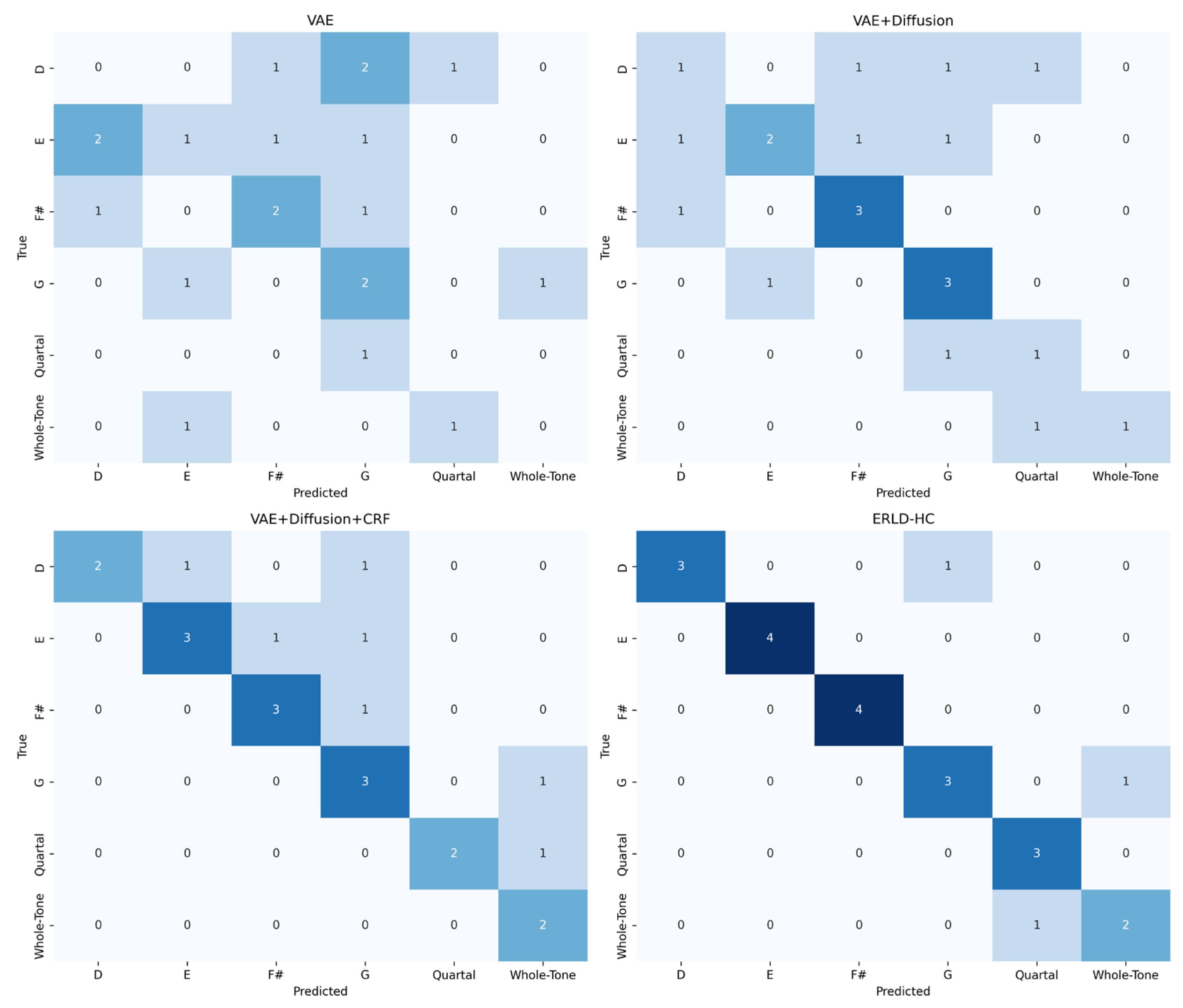

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed strategies in chord inference, we design a multi-dimensional confusion matrix heatmap to compare the alignment between predicted chords and ground truth chords across models. Specifically, for each generation round, we generate 10 sequences and concatenate all frame-level chord labels into two long sequences, from which we compute the confusion matrix after filtering zero-only or non-chord rows and columns.

As shown in

Figure 3, to prove the validity of the model we proposed, we added modules one by one to conduct ablation experiments. The baseline VAE+Diffusion model exhibits scattered and weak diagonal responses, with a mean diagonal value of 1.83, reflecting poor chord consistency and frequent misclassifications. In contrast, the VAE+Diffusion+CRF model achieves a diagonal mean of 2.5, benefiting from the introduction of global harmonic constraints in the initial stage and temporal dependencies captured by CRF. This significantly reduces illogical harmonic transitions and enhances correct chord alignment. Our model, ERLD-HC, further improves the diagonal consistency to 3.16, and effectively resolves ambiguous transitions such as D→G vs. D→F#, which are commonly confused in baseline models. Notably, ERLD-HC retains a small number of non-diagonal but musically plausible transitions such as G→Whole-Tone, demonstrating a balance between theoretical harmonic correctness and creative diversity. The confusion matrix of ERLD-HC (bottom-right in

Figure 3) shows a sparse, sharp diagonal structure, while its few off-diagonal entries reflect stylistic variation rather than noise. These results confirm that our entropy-regularized CRF not only improves the accuracy of harmony, but also maintains the flexibility of expression in symbolic music generation.

In order to further analyze the chord confusion matrix in multiple dimensions, this paper calculates the confusion matrix derivative index Kappa coefficient (Cohen's Kappa) [

26] to evaluate the consistency between predicted and actual chord labels and eliminate the influence of random guesses. The calculation formula is Equation (19):

where

represents observation consistency, that is, the sum of diagonal elements is divided by total sample size, and

represents random consistency, that is, the accuracy rate of expected random guessing, calculated through marginal distribution. The Kappa coefficient is taken between 0 and 1. As shown in

Table 1, the 0.83 of our model is better than the 0.61 of VAE+Diffusion+CRF while retaining diversity. Meanwhile, calculate the proportion of chord transitions predicted by the Functional Compliance Rate (FCR) statistical model that conform to the rules of music theory, which is used to quantify the theoretical rationality. The calculation method is the number of compliant transfers divided by the total number of transfers. In this experiment, 86% of ERLD-HC is higher than 68% of VAE+Diffusion+CRF, which is in line with music theory but retains creativity by controlling non-diagonal elements. And calculate the Stylized Retention Rate(SRR) to quantify the proportion of non-theoretical but artistically valuable chord transitions retained by the model when generating music. Although these transitions do not conform to traditional harmonic rules, they are in line with specific musical styles. The SRR is equal to the number of stylized non-diagonal transfers divided by the total number of non-diagonal transfers. The SRR of ERLD-HC is 33%, indicating that the model selectively retains some theoretically inconsistent but reasonable transitions while maintaining a high FCR, which meets the requirements of creative auxiliary tools.

To further evaluate the chord prediction accuracy of each model, we calculate Precision, Recall, and F1-score [

27] based on the chord-level confusion matrix constructed from the generated sequences. As shown in

Table 2, the baseline VAE+Diffusion model yields an F1-score of 0.51, indicating moderate chord matching performance. By introducing CRF, the VAE+Diffusion+CRF model achieves a significantly improved F1-score of 0.68. Our proposed ERLD-HC framework achieves the highest scores across all three metrics, with an F1 of 0.82, demonstrating that entropy-regularized chord inference within the diffusion process leads to more precise and consistent harmonic predictions.

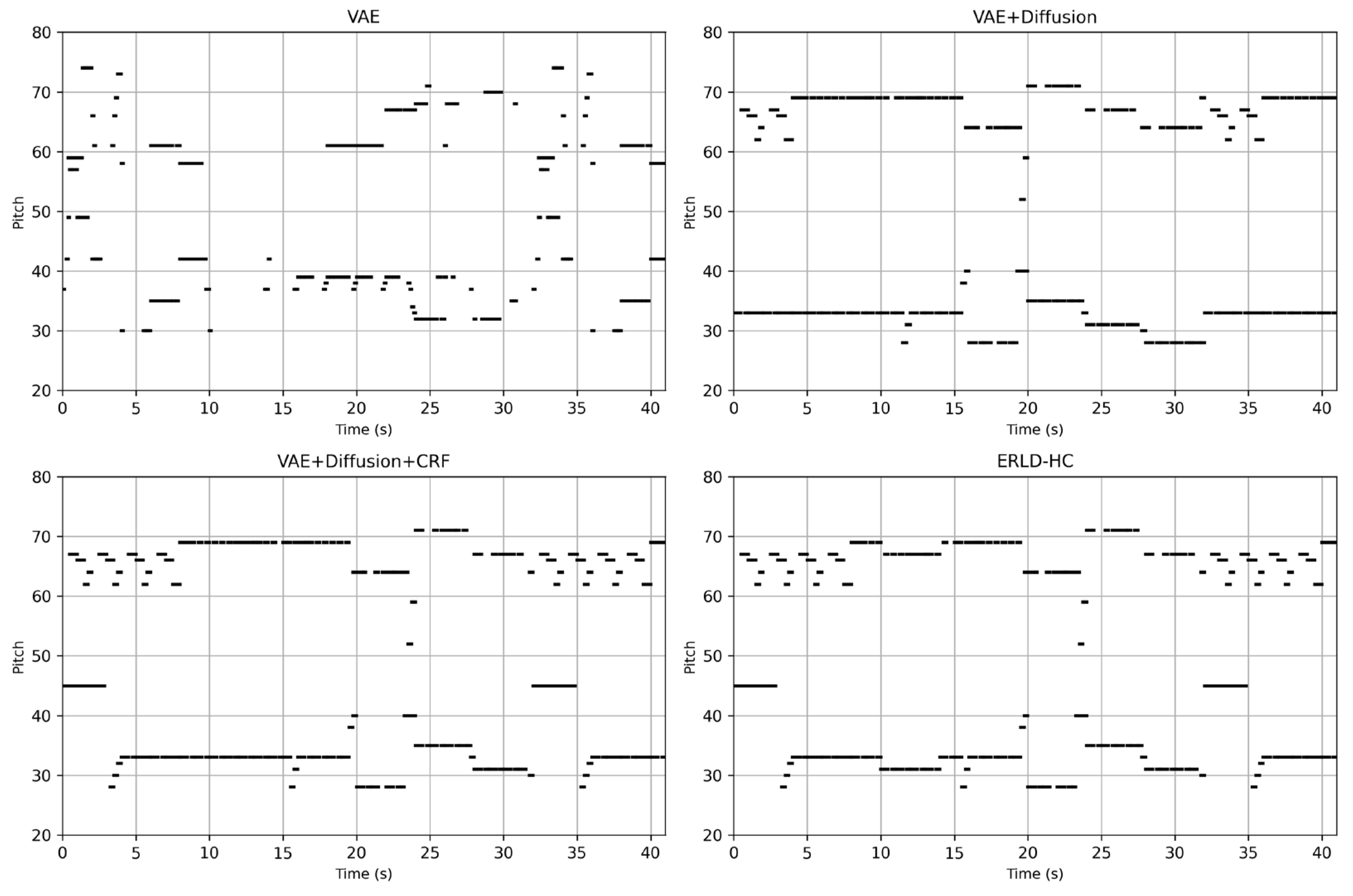

4.3. Visual Comparison of MIDI Generation Across Models

To visualize the MIDI generated by our models, we rendered the piano rolls of two benchmark model, the VAE+Diffusion+CRF model, and our proposed ERLD-HC model, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The note sequences generated by the baseline VAE model exhibit a lack of rhythmic structure, abrupt changes, and overall chaotic and incoherent patterns. Although the diffusion-based baseline improves coherence, it suffers from excessive repetition. The VAE+Diffusion+CRF model reduces redundancy but still contains a recurring 10-second repetition. In contrast, our ERLD-HC model displays tighter note groupings, a more balanced pitch distribution, and higher rhythmic entropy—indicating enhanced phrase-level coherence and structural consistency in the generated music.

4.4. Design of Evaluation Indicators for Music Generation

In order to verify the Entropy-Regularized Latent Diffusion for Harmony Constrained model designed in this paper, this paper conducts ablation experiments from three dimensions: Harmony, Melody, and Overall Generation Quality, and evaluates the contributions of different modules respectively.

4.4.1. Harmony Assessment

The harmony violation rate(HVR) [

28] is an indicator that quantifies the degree of violation of traditional harmony rules (such as part progression, chord connection, dissonant resolution, etc.) in musical works. This indicator analyzes the interval relationship between consecutive chords and counts the frequency of parallel fifths/octaves and interval jumps. The calculation formula can be expressed in Equation (20):

represents the number of violations detected within the analysis range, represents the overall analysis of harmony events.

- 2.

Chord Transition Probability(CTP)

Chord transition probability(CTP) [

29] describes the transition rules of adjacent chords in MIDI sequences and reflects the statistical characteristics of harmonic progressions. Given chord sequence

, its transition probability matrix

is defined in Equation (21):

Here,

represents the number of chord categories, and

is the frequency of transitions from chord

to

in the training data. In order to facilitate the comparison of various model indicators, in this paper, chord transition entropy(CTE)

is used instead of chord transition probability. The chord transition frequency is statistically calculated from the LMD dataset, smoothed by Laplace and normalized to avoid zero probability. The chord transition entropy is obtained by calculating the shannon entropy for the probability distribution

of each row of the transition matrix

and taking the average as shown in Equation (22):

- 3.

Chord Saturation (CS)

Chord saturation(CS) quantifies how densely pitches are packed within a chord, helping to capture how full or harmonically tense a chord is perceived to be. High-saturation chords usually contain a large number of notes and have a compact pitch distribution, while low-saturation chords may consist of only a few notes. We define chord saturation as the ratio of the total number of notes in a musical segment to the maximum possible number of notes as shown in Equation (23), where the maximum value is calculated as 12 times the number of chords (assuming that each chord can theoretically cover all 12 pitches). This indicator quantifies the overall harmonic density by measuring the degree to which music utilizes the chromatic scale. Its value close to 1 indicates rich harmonic content, while a value close to 0 indicates less pitch variation:

4.4.2. Melodic Assessment

The smoothness of the pitch contour quantifies how continuously the pitch changes in a melody. A smoother contour implies smaller and more gradual pitch intervals between adjacent notes, which often suggests higher melodic coherence. One proxy for measuring this coherence is the average second-order difference of pitch values. A lower value indicates a more coherent and less jumping melody, while higher values correspond to more abrupt melodic changes. As shown in Equation (24), the pitch sequence

is extracted from the melody part of a MIDI file, sorted by onset time, and evaluated using a second-order difference within a sliding window.

- 2.

Contour Volatility(CV)

Contour volatility(CV) is an indicator for quantifying the intensity of melodic pitch changes, comprehensively reflecting the amplitude and frequency of directional changes of interval jumps. Unlike Smoothness which focuses on continuity, volatility emphasizes the unpredictability of change and is suitable for evaluating the improvisational nature, decorative complexity or tension of a melody. It is calculated by comparing the number of direction reversals (for example, from rising to falling) with all possible transition numbers as shown in Equation (25). A higher value indicates the presence of complex ornamental notes, while a lower value suggests that the melody moves linearly.

represents the total number of notes, represents the number of direction changes, and the denominator indicates possible combinations of three adjacent notes.

4.4.3. Overall Generation Quality

The structural index (SI) assesses the clarity of musical forms by measuring the degree of separation between clusters in the feature space. A high SI value (close to 1) indicates that each part is clearly defined, while a low value indicates a loose structure. This indicator is used to evaluate the structural coherence of the music generated by the algorithm. First, extract the multi-dimensional feature generation matrix from MIDI, where is the number of notes and

is the feature dimension, Then, the features are standardized to eliminate dimensional differences, the data is divided into segments corresponding to the structure of

K clusters by using k-means [

30], the cluster label of each note is obtained, and the mean of the contour coefficients of all samples is calculated as the SI value as shown in Equation (26):

is the average distance from sample to other points in the same cluster, and is the average distance from sample to the nearest opposite cluster. The range of SI is between -1 and 1. The higher the value, the clearer the structure.

- 2.

Pitch Naturalness(PN)

Pitch naturalness measures the degree to which a pitch sequence adheres to style conventions. It combines scale conformity, interval statistics and harmonic rules. High values indicate that the melody has tonal coherence, while low values reflect atonal or experimental textures. Given a note sequence

, calculate the semitone difference

of the note and count the proportion of intervals that satisfy

as shown in Equation (27):

is an indicative function. The higher the value, the stronger the nature.

4.4.4. Experimental Result

This section quantitatively evaluates the performance of the baseline model, its variants, and the proposed ERLD-HC framework in symbolic music generation, focusing on three key dimensions: harmonic structure, melodic contour, and overall generative quality. To ensure fair comparison, all models generate 50 MIDI sequences of a fixed duration of 41 seconds, and the reported results are averaged across all generations. Both unconditional and conditional generation settings are assessed, as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4, respectively.

In the unconditional generation, the baseline VAE exhibits a relatively high HVR of 4.55% and CV of 0.49, reflecting its limited theoretical constraints in music. Although incorporating a diffusion process (VAE+Diffusion) slightly reduces the violation rate to 3.90%, it leads to increased CTE of 0.725, indicating that the model gains diversity at the cost of harmonic consistency.The introduction of CRF constraints in VAE+Diffusion reduces the HVR further to 2.65% and lowers the CTE to 0.61, suggesting improved structural coherence.

The ERLD-HC model that we proposed achieves the best performance, with a HVR of only 1.55%, CTE of 0.48, and the highest PN of 0.88 and SI of 0.81, confirming that our hierarchical entropy-regularization constraint can balance creativity and harmony rules.

In conditional generation, that is, in input-based MIDI, ERLD-HC yields the best results, achieving a HVR of 1.30%, CTE of 0.32, and highest PN of 0.94. These findings underscore the benefit of integrating rule-based modules into probabilistic generative frameworks: the diffusion model provides a foundation for generative diversity, while the CRF with entropy regularization introduces theoretical rule and controls structural fluctuation, resulting in outputs that exhibit rich harmonic structure and maintain stylistic consistency.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes ERLD-HC , a novel symbolic music generation framework that integrates structural priors with deep generative modeling. Built upon a VAE+Diffusion backbone, the framework introduces an entropy-regularized CRF module into the cross-attention layers of the diffusion model, enabling enhanced control over harmonic progression during generation.

Experimental results show that ERLD-HC consistently improves upon baseline VAE+Diffusion models, particularly in harmonic coherence and melodic smoothness. We also observe that introducing entropy regularization into the CRF inference helps reduce overconfidence in chord labeling, while maintaining the diversity of harmony, the melodic changes can be more harmonious.This integration allows the model to balance adherence to harmonic rules with stylistic freedom, resulting in outputs that are both structured and expressive.

Furthermore, ERLD-HC proved the validity of combining the diffusion model and the structured probability model. By embedding CRF inference within the cross-attention mechanism of the diffusion process, the model effectively aligns latent representations with explicit musical structure, resolving both note-level and global harmonic inconsistencies. This design highlights the value of incorporating music-theoretical priors into generative models for future research at the intersection of deep learning and symbolic music reasoning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is from The Lakh MIDI dataset.The Lakh MIDI dataset is a collection of 176,581 unique MIDI files, 45,129 of which have been matched and aligned to entries in the Million Song Dataset. Its goal is to facilitate large-scale music information retrieval, both symbolic (using the MIDI files alone) and audio content-based (using information extracted from the MIDI files as annotations for the matched audio files). This paper adopts the LMD-matched dataset. You can obtain it at

https://colinraffel.com/projects/lmd/.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the use of the Lakh MIDI Dataset (LMD) for this research and thanks the creators of the Magenta project for their inspiring methodologies. The author prepared the figures using LaTeX drawing tools. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dong, L. Using deep learning and genetic algorithms for melody generation and optimization in music. Soft Computing 2023, 27, 17419–17433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H.; Su, Z.; Wu, Y. Hyperbolic Music Transformer for Structured Music Generation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 26893–26905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Engel, J.; Raffel, C.; Hawthorne, C.; Eck, D. A Hierarchical Latent Vector Model for Learning Long-Term Structure in Music. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Stockholm, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 4364–4373. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-Z.A.; Vaswani, A.; Uszkoreit, J.; Simon, I.; Hawthorne, C.; Shazeer, N.; Dai, A.M.; Hoffman, M.D.; Dinculescu, M.; Eck, D. Music Transformer: Generating Music with Long-Term Structure. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tie, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, D.; Tie, J.; Qi, L.; Lu, Y. Hybrid Learning Module-Based Transformer for Multitrack Music Generation With Music Theory. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2025, 12, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Xiao, Z. Structured Music Transformer: Structured conditional music generation based on stylistic clustering using Transformer. In Proceedings of the 43rd Chinese Control Conference (CCC 2024), Kunming, China, 28–31 July 2024; pp. 8230–8235. [Google Scholar]

- Soua, R.; Livolant, E.; Minet, P. MUSIKA: A multichannel multi-sink data gathering algorithm in wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 9th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Sardinia, Italy, 1–5 July 2013; pp. 1370–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, W.-Y.; Liu, J.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-C.; Yang, Y.-H. Compound Word Transformer: Learning to Compose Full-Song Music over Dynamic Directed Hypergraphs. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online; 2021; pp. 178–186. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, M.; Tan, X.; Wang, R.; Ju, Z.; Qin, T.; Liu, T.-Y. MusicBERT: Symbolic Music Understanding with Large-Scale Pre-Training. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; Online, 2021; pp. 791-800.

- Yuan, R.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wu, S.; Shen, T.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Z.; et al. ChatMusician: Understanding and Generating Music Intrinsically with LLM. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024; Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 6252–6271.

- Zhang, J.; Fazekas, G.; Saitis, C. Composer Style-Specific Symbolic Music Generation using Vector Quantized Discrete Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 34th International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), London, United Kingdom, 22–25 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, G.; Engel, J.; Hawthorne, C.; Simon, I. Symbolic Music Generation with Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR), Online; 2021; pp. 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Ghatare, A.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Sastry, C.S.; Gururani, S.; Oore, S.; Yue, Y. Symbolic music generation with non-differentiable rule guided diffusion. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21-27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zixun, G.; Makris, D.; Herremans, D. Hierarchical Recurrent Neural Networks for Conditional Melody Generation with Long-term Structure. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Shenzhen, China, 18-22 July 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, M.; Wang, C.; Richard, G. Structure-Informed Positional Encoding for Music Generation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2024, 14-19 April 2024; pp. 951–955. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjeres, G.; Pachet, F.; Nielsen, F. DeepBach: a Steerable Model for Bach Chorales Generation. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 1362–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty, J.D.; McCallum, A.; Pereira, F.C.N. Conditional Random Fields: Probabilistic Models for Segmenting and Labeling Sequence Data. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2001), Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA, 28 June – 1 July 2001; pp. 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, California, USA; 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015, Munich, Germany; 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27-30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6-12 December 2020; pp. 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner, L.R. A tutorial on hidden Markov models and selected applications in speech recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1989, 77, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. An Introduction to Feature Selection. In Applied Predictive Modeling; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 487–519. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Han, P.; Ren, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Shang, S. Sequence Labeling With Meta-Learning. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2023, 35, 3072–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. Linear Methods for Regression. In The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 41–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From Precision, Recall and F-measure to ROC, Informedness, Markedness and Correlation. Journal of Machine Learning Technologies 2011, 2, 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bendixen, A.; SanMiguel, I.; Schröger, E. Representation of harmony rules in the human brain. Brain Research 2007, 1155, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, C.; Brand, F.; Müller, M. Mid-level Chord Transition Features for Musical Style Analysis. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2019 - 2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Brighton, UK, 12-17 May 2019; pp. 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y. Convergence properties of the K-means algorithms. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 1994, 585–592. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).