Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Sustainable Aviation Roadmaps

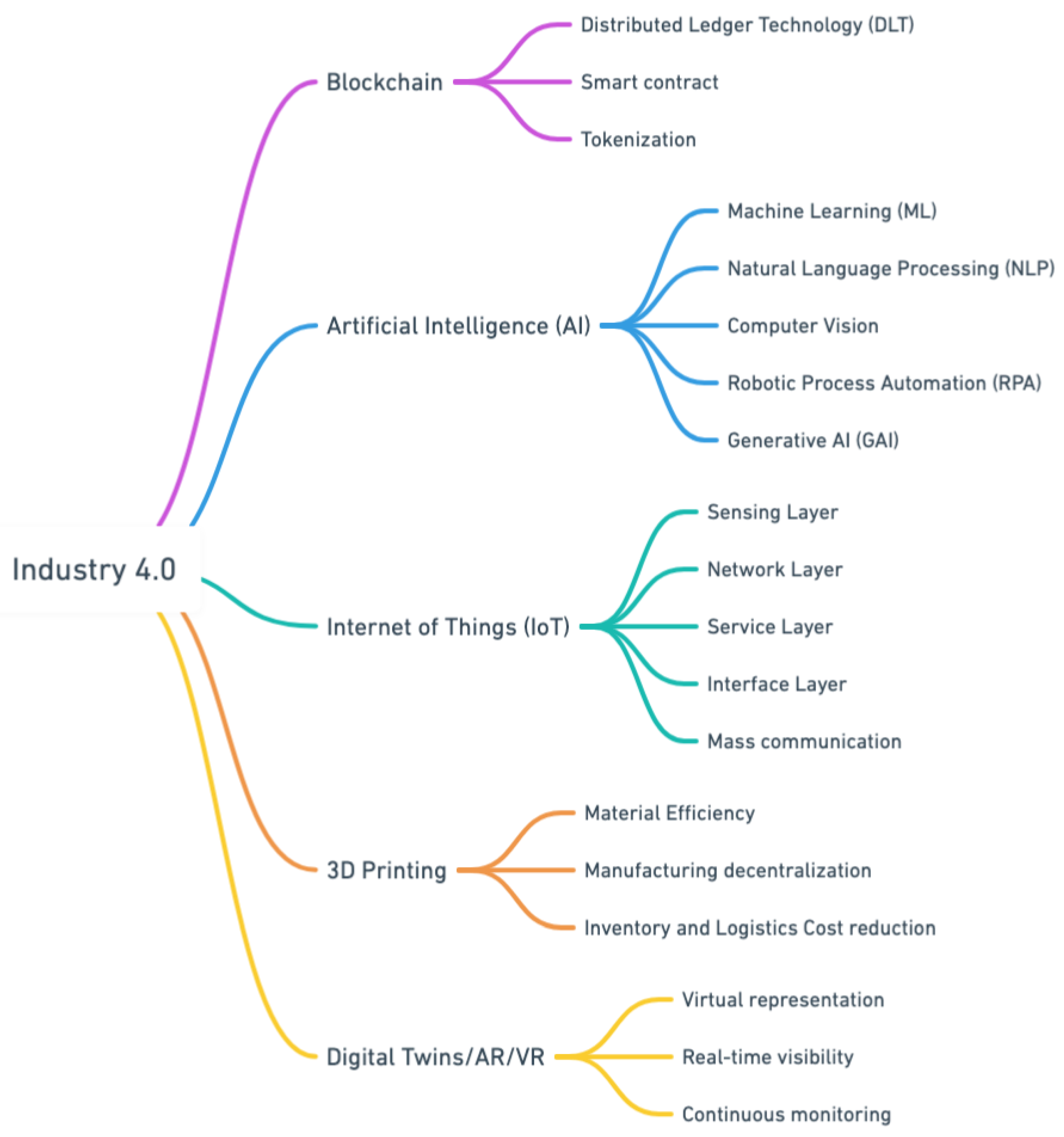

2.2. Industry 4.0

2.2.1. Blockchains

2.2.2. AI

2.2.3. Internet of Things (IoT)

2.2.4. 3D Printing

2.2.5. Simulations (Digital twins/AR/VR)

2.2. Research Gaps

3. Research Methods

- (1)

- Provide reviews that enhance understanding of Industry 4.0 and its representative technologies.

- (2)

- Provide knowledge that highlights the applications of Industry 4.0 in supply chain management.

- (3)

- Bridge the understanding of how disruptive technologies under Industry 4.0 could address the six streams of SAF grand challenges.

4. Discussion and Implications

4.2. Feedstock Innovation

4.2.6. Recourse Market and Availability Analysis

4.2.7. Increase Sustainable Lipid Supply

4.2.8. Boost Biomass Production and Waste Collection

4.2.9. Improve Feedstock Supply Logistics

4.2.10. Improve Feedstock Handling System Reliability

4.2.11. Enhance Sustainability of Biomass and Waste Supply Systems

4.3. Conversion Technology

4.3.6. Decarbonize, Diversify, and Scale the Current Fermentation-Based Fuel Industry

4.3.7. Enhance Production and Reduce Carbon Intensity of Existing ASTM-Approved Pathways

4.3.8. Develop Bio-Intermediates and Pathways Compatible with Existing Capital Assets.

4.3.9. Reduce Risk During Operations and Scale-Up

4.3.10. Develop Innovative Unit Operations and Pathways

4.4. Building Supply Chains

4.4.6. Establish Regional Stakeholder Coalitions

4.4.7. Model SAF Supply Chains

4.4.8. Demonstration of Regional SAF Supply Chains

4.4.9. Develop a Production Infrastructure to Support SAF Deployment in the Industry

4.5. Policy and Valuation

4.5.6. Improve the Environmental Data and Models for SAF

4.5.7. Conduct Techno-Economic and Production Feasibility Analysis

4.5.8. Contribute to SAF Policy Development

4.6. Enabling End Use

4.6.6. Support SAF Evaluation, Testing, Qualification, and Specification

4.6.7. Facilitate the Adoption of Unblended and High-Percentage SAF Blends, Including Up to 100% SAF

4.6.8. Explore Synthetic Jet Fuels that Enhance Operational Performance and Productivity

4.6.9. Adapt Fuel Infrastructure to Support the Distribution and Use of SAF

4.7. Communicating Progress and Building Support

4.7.6. Engage Stakeholders to Promote Awareness and Collaboration on Sustainable Feedstock Practices

4.7.7. Carry out a Comprehensive Assessment of the Benefits and Influence of the SAF Grand Challenge

4.7.8. Track the Advancement of the SAF Grand Challenge Objectives

4.7.9. Share the Positive Impacts of the SAF Grand Challenge with the Broader Community

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abideen, A. Z., Sundram, V. P. K., Pyeman, J., Othman, A. K., & Sorooshian, S. (2021). Digital Twin Integrated Reinforced Learning in Supply Chain and Logistics. Logistics, 5(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Abu Talib, M., Nasir, Q., Dakalbab, F., & Saud, H. (2025). Future aviation jobs: The role of technology in shaping skills and competencies. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 11(2), 100517. [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, I., Nwulu, N., & Adebo, O. A. (2023). Internet of Things (IoT) in the food fermentation process: A bibliometric review. Journal of Food Process Engineering, 46(5), e14321. [CrossRef]

- Aejas, B., Belhi, A., & Bouras, A. (2025). Using AI to Ensure Reliable Supply Chains: Legal Relation Extraction for Sustainable and Transparent Contract Automation. Sustainability, 17(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Agnusdei, G. P., Elia, V., & Gnoni, M. G. (2021). Is Digital Twin Technology Supporting Safety Management? A Bibliometric and Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 11(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W. (2025). Artificial Intelligence in Aviation: A Review of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Applications for Enhanced Safety and Security. Premier Journal of Artificial Intelligence. [CrossRef]

- AI Applications for Renewable Fuel Producers. (n.d.). Imubit. Retrieved June 7, 2025, from https://imubit.com/ai-applications-for-renewable-fuel-producers/.

- Ai, W., & Cho, H. M. (2024). Predictive Models for Biodiesel Performance and Emission Characteristics in Diesel Engines: A Review. Energies, 17(19), Article 19. [CrossRef]

- Airbus. (2021, November 8). This chase aircraft is tracking 100% SAF’s emissions performance | Airbus. https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/stories/2021-11-this-chase-aircraft-is-tracking-100-safs-emissions-performance.

- Airbus. (2025, April 23). Digital Twins: Accelerating aerospace innovation from design to operations | Airbus. https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/stories/2025-04-digital-twins-accelerating-aerospace-innovation-from-design-to-operations.

- Akbari, M., Ha, N., & Kok, S. (2022). A systematic review of AR/VR in operations and supply chain management: Maturity, current trends and future directions. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 15(4), 534–565. [CrossRef]

- Akhator, P., & Oboirien, B. (2025). Digitilising the energy sector: A comprehensive digital twin framework for biomass gasification power plant with CO2 capture. Cleaner Energy Systems, 10, 100175. [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, N., Mehmood, R., Alzahrani, A., Yigitcanlar, T., & Corchado, J. M. (2023). Autonomous and Sustainable Service Economies: Data-Driven Optimization of Design and Operations through Discovery of Multi-Perspective Parameters. Sustainability, 15(22), Article 22. [CrossRef]

- Alam, A., & Dwivedi, P. (2019). Modeling site suitability and production potential of carinata-based sustainable jet fuel in the southeastern United States. Journal of Cleaner Production, 239, 117817. [CrossRef]

- Alaska. (2021, April 21). Alaska Airlines commits to carbon, waste and water goals for 2025, announces path to net zero by 2040—Apr 21, 2021. Alaska Airlines News. https://news.alaskaair.com/newsroom/alaska-airlines-commits-to-carbon-waste-and-water-goals-for-2025-announces-path-to-net-zero-by-2040/.

- Ali Ijaz Malik, M., Kalam, M. A., Mujtaba Abbas, M., Susan Silitonga, A., & Ikram, A. (2024). Recent advancements, applications, and technical challenges in fuel additives-assisted engine operations. Energy Conversion and Management, 313, 118643. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. M., Rahman, A. U., Kabir, G., & Paul, S. K. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Approach to Predict Supply Chain Performance: Implications for Sustainability. Sustainability, 16(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Alkhader, W., Alkaabi, N., Salah, K., Jayaraman, R., Arshad, J., & Omar, M. (2020). Blockchain-Based Traceability and Management for Additive Manufacturing. IEEE Access, 8, 188363–188377. [CrossRef]

- Al-Qaseemi, S. A., Almulhim, H. A., Almulhim, M. F., & Chaudhry, S. R. (2016). IoT architecture challenges and issues: Lack of standardization. 2016 Future Technologies Conference (FTC), 731–738. [CrossRef]

- Al-Rakhami, M. S., & Al-Mashari, M. (2021). A Blockchain-Based Trust Model for the Internet of Things Supply Chain Management. Sensors, 21(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, S., Wang, Q., & Bennett, N. (2016). Application and integration of an RFID-enabled warehousing management system – a feasibility study. Journal of Industrial Information Integration, 4, 15–25. [CrossRef]

- Andiappan, V., How, B. S., & Ngan, S. L. (2021). A Perspective on Post-Pandemic Biomass Supply Chains: Opportunities and Challenges for the New Norm. Process Integration and Optimization for Sustainability, 5(4), 1003–1010. [CrossRef]

- Andriulo, F. C., Fiore, M., Mongiello, M., Traversa, E., & Zizzo, V. (2024). Edge Computing and Cloud Computing for Internet of Things: A Review. Informatics, 11(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M. Y., Hossain, M. J., & Alam, M. M. (2024). Machine learning scopes on microgrid predictive maintenance: Potential frameworks, challenges, and prospects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 190, 114088. [CrossRef]

- Arias, A., Feijoo, G., & Moreira, M. T. (2023). How could Artificial Intelligence be used to increase the potential of biorefineries in the near future? A review. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 32, 103277. [CrossRef]

- Arinze, C. A., Izionworu, Onuegbu, V., Isong, D., Daudu, C. D., & Adefemi, A. (2024). Predictive maintenance in oil and gas facilities, leveraging ai for asset integrity management. International Journal of Frontiers in Engineering and Technology Research, 6(1), 016–026. [CrossRef]

- Asghar, A., Sairash, S., Hussain, N., Baqar, Z., Sumrin, A., & Bilal, M. (2022). Current challenges of biomass refinery and prospects of emerging technologies for sustainable bioproducts and bioeconomy. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining, 16(6), 1478–1494. [CrossRef]

- Ashok, M., Madan, R., Joha, A., & Sivarajah, U. (2022). Ethical framework for Artificial Intelligence and Digital technologies. International Journal of Information Management, 62, 102433. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, F., & Calghan, J. (2023). Using NLP to Enhance Supply Chain Management Systems. Journal of Engineering Research and Reports, 25(9), 211–219. [CrossRef]

- ASTM. (2025, July 5). Standard Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuel Containing Synthesized Hydrocarbons. https://store.astm.org/d7566-22.html.

- Baicu, L. M., Andrei, M., Ifrim, G. A., & Dimitrievici, L. T. (2024). Embedded IoT Design for Bioreactor Sensor Integration. Sensors, 24(20), Article 20. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, D., Sharma, P., Bora, B. J., & Dizge, N. (2024). Harnessing biomass energy: Advancements through machine learning and AI applications for sustainability and efficiency. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 191, 193–205. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, N. (2023). Biomass to Energy—An Analysis of Current Technologies, Prospects, and Challenges. BioEnergy Research, 16(2), 683–716. [CrossRef]

- Banur, O. M., Patle, B. K., & Pawar, S. (2024, February 21). Integration of robotics and automation in supply chain: A comprehensive review—Extrica. https://www.extrica.com/article/23349.

- Bastani, H., Zhang, D. J., & Zhang, H. (2022). Applied Machine Learning in Operations Management. In V. Babich, J. R. Birge, & G. Hilary (Eds.), Innovative Technology at the Interface of Finance and Operations: Volume I (pp. 189–222). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Bastos, T., Teixeira, L. C., & Nunes, L. J. R. (2024). Forest 4.0: Technologies and digitalization to create the residual biomass supply chain of the future. Journal of Cleaner Production, 467, 143041. [CrossRef]

- Baumann, S., & Klingauf, U. (2020). Modeling of aircraft fuel consumption using machine learning algorithms. CEAS Aeronautical Journal, 11(1), 277–287. [CrossRef]

- Bergero, C., Gosnell, G., Gielen, D., Kang, S., Bazilian, M., & Davis, S. J. (2023). Pathways to net-zero emissions from aviation. Nature Sustainability, 6(4), 404–414. [CrossRef]

- Bhagwan, N., & Evans, M. (2023). A review of industry 4.0 technologies used in the production of energy in China, Germany, and South Africa. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 173, 113075. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A., Bhargava, D., Kumar, P. N., Sajja, G. S., & Ray, S. (2022). Industrial IoT and AI implementation in vehicular logistics and supply chain management for vehicle mediated transportation systems. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 13(1), 673–680. [CrossRef]

- Bhashyam, A., VP, G., Engineering, S., & Ai, C. (2022). The Scale of Shell’s Global AI Predictive Maintenance Program. C3 AI. https://c3.ai/blog/how-shell-scaled-ai-predictive-maintenance-to-monitor-10000-pieces-of-equipment-globally/.

- Bioenergy Insight. (2023, May 25). US Energy Secretary heralds $15m biomass facility upgrade. Bioenergy Insight. https://www.bioenergy-news.com/news/us-energy-secretary-heralds-15m-biomass-facility-upgrade/.

- Bioledger, R. on S. B. (RSB) and. (2021). Blockchain Database for Sustainable Biofuels: A Case Study.

- Biran, O., Feder, O., Moatti, Y., Kiourtis, A., Kyriazis, D., Manias, G., Mavrogiorgou, A., Sgouros, N. M., Barata, M. T., Oldani, I., Sanguino, M. A., Kranas, P., & Baroni, S. (2022). PolicyCLOUD: A prototype of a cloud serverless ecosystem for policy analytics. Data & Policy, 4, e44. [CrossRef]

- Bocca, R., Espinoza, N., & Jamison, S. (2025, January). Unleashing the Full Potential of Industrial Clusters: Infrastructure Solutions for Clean Energies. https://initiatives.weforum.org/transitioning-industrial-clusters/case-study-details/avelia,-the-blockchain-powered-book-and-claim-solution-for-scaling-saf-demand/aJYTG0000000UkT4AU.

- Boeing. (2023, June 20). Boeing Launches SAF Dashboard to Track and Project Sustainable Aviation Fuel Production. https://investors.boeing.com/investors/news/press-release-details/2023/Boeing-Launches-SAF-Dashboard-to-Track-and-Project-Sustainable-Aviation-Fuel-Production/default.aspx.

- Borges, M. E., Hernández, L., Ruiz-Morales, J. C., Martín-Zarza, P. F., Fierro, J. L. G., & Esparza, P. (2017). Use of 3D printing for biofuel production: Efficient catalyst for sustainable biodiesel production from wastes. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 19(8), 2113–2127. [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P. F. (2021). Digitization, Digital Twins, Blockchain, and Industry 4.0 as Elements of Management Process in Enterprises in the Energy Sector. Energies, 14(7), Article 7. [CrossRef]

- Borrill, E., Koh, S. C. L., & Yuan, R. (2024). Review of technological developments and LCA applications on biobased SAF conversion processes. Frontiers in Fuels, 2. [CrossRef]

- Brett, D. (2024, November 19). New blockchain platform launched for SAF usage tracking in cargo. Air Cargo News. https://www.aircargonews.net/new-blockchain-platform-launched-for-saf-usage-tracking-in-cargo/1079016.article.

- Brody, P. (2017). How blockchain is revolutionizing supply chain management. Digitalist Magazine (SAP).

- Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. (2025). Generative AI at Work*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 140(2), 889–942. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.-J., Choi, T.-M., & Zhang, J. (2021). Platform Supported Supply Chain Operations in the Blockchain Era: Supply Contracting and Moral Hazards. Decision Sciences, 52(4), 866–892. [CrossRef]

- CASS. (2024). Singapore Sustainable Air Hub Blueprint. Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore. https://www.caas.gov.sg/docs/default-source/docs---so/singapore-sustainable-air-hub-blueprint.pdf.

- CFR. (2022, July). Clean Fuel Regulations. https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2022/2022-07-06/html/sor-dors140-eng.html.

- Chan, H. K., Griffin, J., Lim, J. J., Zeng, F., & Chiu, A. S. F. (2018). The impact of 3D Printing Technology on the supply chain: Manufacturing and legal perspectives. International Journal of Production Economics, 205, 156–162. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. E., Chen, Y.-C., & Lu, M.-F. (2019). Supply chain re-engineering using blockchain technology: A case of smart contract based tracking process. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 144, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y., Iakovou ,Eleftherios, & and Shi, W. (2020). Blockchain in global supply chains and cross border trade: A critical synthesis of the state-of-the-art, challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Production Research, 58(7), 2082–2099. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A., Brouwer, B., & Westra, E. (2022). Robotics for a Quality-Driven Post-harvest Supply Chain. Current Robotics Reports, 3(2), 39–48. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, C., & Singh, A. (2019). A review of Industry 4.0 in supply chain management studies. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 31(5), 863–886. [CrossRef]

- Chavan, C., Hembade, S., Jadhav, G., Komalwad, P., & Rawat, P. (2023). Computer Vision Application Analysis based on Object Detection. INTERANTIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT, 07(04). [CrossRef]

- Chávez, M. M. M., Sarache, W., & Costa, Y. (2018). Towards a comprehensive model of a biofuel supply chain optimization from coffee crop residues. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 116, 136–162. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H., Chen, G., He, J., & Kannan, D. (2024). Big data for logistics decarbonization. Annals of Operations Research, 343(3), 923–925. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., vom Lehn, F., Pitsch, H., & Cai, L. (2025). Design of novel high-performance fuels with artificial intelligence: Case study for spark-ignition engine applications. Applications in Energy and Combustion Science, 23, 100341. [CrossRef]

- Chireshe, F., Petersen, A. M., Ravinath, A., Mnyakeni, L., Ellis, G., Viljoen, H., Vienings, E., Wessels, C., Stafford, W. H. L., Bole-Rentel, T., Reeler, J., & Görgens, J. F. (2025). Cost-effective sustainable aviation fuel: Insights from a techno-economic and logistics analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 210, 115157. [CrossRef]

- Choi, T., Kumar, S., Yue, X., & Chan, H. (2022). Disruptive Technologies and Operations Management in the Industry 4.0 Era and Beyond. Production and Operations Management, 31(1), 9–31. [CrossRef]

- Comesana, A. E., Huntington, T. T., Scown, C. D., Niemeyer, K. E., & Rapp, V. H. (2022). A systematic method for selecting molecular descriptors as features when training models for predicting physiochemical properties. Fuel, 321, 123836. [CrossRef]

- Corsini, L., Aranda-Jan ,Clara Beatriz, & and Moultrie, J. (2022). The impact of 3D printing on the humanitarian supply chain. Production Planning & Control, 33(6–7), 692–704. [CrossRef]

- COSCO. (2024, April 9). COSCO SHIPPING Lines Introduces Traceable and Verifiable Green Certificates with GSBN Empowered by Blockchain Technology. https://en.coscoshipping.com/col/col6923/art/2024/art_3b7a182117d8421194ba7e9d2c24a98e.html.

- Csedő, Z., Magyari, J., & Zavarkó, M. (2024). Biofuel supply chain planning and circular business model innovation at wastewater treatment plants: The case of biomethane production. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain, 11, 100158. [CrossRef]

- CSIRO. (2023). Sustainable Aviation Fuel Roadmap. Australia’s National Science Agency. https://www.csiro.au/en/work-with-us/services/consultancy-strategic-advice-services/CSIRO-futures/Energy/Sustainable-Aviation-Fuel-Roadmap.

- Cui, Q., & Chen, B. (2024). Cost-benefit analysis of using sustainable aviation fuels in South America. Journal of Cleaner Production, 435, 140556. [CrossRef]

- D Kulkarni Saurav, N. (2024). Revolutionizing Manufacturing: The Integral Role of AI and Computer Vision in Shaping Future Industries. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 13(1), 1183–1188. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, M. A. V. F., & Normey-Rico, J. E. (2011). Modeling, Control and Optimization of Ethanol Fermentation Process. IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 44(1), 10609–10614. [CrossRef]

- Despeisse, M., Baumers, M., Brown, P., Charnley, F., Ford, S. J., Garmulewicz, A., Knowles, S., Minshall, T. H. W., Mortara, L., Reed-Tsochas, F. P., & Rowley, J. (2017). Unlocking value for a circular economy through 3D printing: A research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 115, 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Dilek, E., & Dener, M. (2023). Computer Vision Applications in Intelligent Transportation Systems: A Survey. Sensors, 23(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- DOE. (2023). Data, Modeling, and Analysis Program. Energy.Gov. https://www.energy.gov/eere/bioenergy/data-modeling-and-analysis-program.

- DOE, USDA, DOT, and EPA. (2022). Sustainable Aviation Fuel Grand Challenge Roadmap: Flight Plan for Sustainable Aviation Fuel Report. https://www.energy.gov/eere/bioenergy/articles/sustainable-aviation-fuel-grand-challenge-roadmap-flight-plan-sustainable.

- Dryad. (2025). Ultra Early Wildfire Detection | Dryad Networks. Dryad. https://www.dryad.net.

- Duan, Y., Edwards, J. S., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2019). Artificial intelligence for decision making in the era of Big Data – evolution, challenges and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management, 48, 63–71. [CrossRef]

- Duc, D. N., & Nananukul, N. (2023). An integrated methodology based on machine-learning algorithms for biomass supply chain optimisation. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management, 46(1), 47–75. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Ismagilova, E., Aarts, G., Coombs, C., Crick, T., Duan, Y., Dwivedi, R., Edwards, J., Eirug, A., Galanos, V., Ilavarasan, P. V., Janssen, M., Jones, P., Kar, A. K., Kizgin, H., Kronemann, B., Lal, B., Lucini, B., … Williams, M. D. (2021). Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 57, 101994. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Pandey, N., Currie, W., & Micu, A. (2023). Leveraging ChatGPT and other generative artificial intelligence (AI)-based applications in the hospitality and tourism industry: Practices, challenges and research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S., Haji Esmaeili, S. A., Sobhani, A., & Szmerekovsky, J. (2022). Renewable jet fuel supply chain network design: Application of direct monetary incentives. Applied Energy, 310, 118569. [CrossRef]

- Emerson. (2022). Emerson and Neste Engineering Solutions to Optimize Fintoil Biorefinery Operations for More Efficient, Sustainable Production | Emerson US. https://www.emerson.com/en-us/news/automation/22-6-digital-technologies-optimize-biorefinery-operations.

- Emerson. (2025, June 20). Fuel Blending | Emerson US. https://www.emerson.com/en-us/industries/automation/downstream-hydrocarbons/refining/fuel-blending.

- Enderle, B., Rauch, B., Hall, C., & Bauder, U. (2021). A proposed Digital Twin concept for the smart utilization of Sustainable Aviation Fuels. In AIAA SCITECH 2022 Forum. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. [CrossRef]

- Ethereum. (2025). Solidity—Solidity 0.8.31 documentation. https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/latest/.

- European Parliament. (2021). ReFuelEU Aviation—Sustainable Aviation Fuels | Legislative Train Schedule. European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/spotlight-JD21/file-refueleu-aviation?sid=5201.

- Eyo-Udo, N. L., Agho, M. O., Onukwulu, E. C., Sule, A. K., & Azubuike, C. (2025). Advances in Blockchain Solutions for Secure and Efficient Cross-Border Payment Systems. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Applied Science, IX(XII), 536–563. [CrossRef]

- Fang, B., Yu, J., Chen, Z., Osman, A. I., Farghali, M., Ihara, I., Hamza, E. H., Rooney, D. W., & Yap, P.-S. (2023). Artificial intelligence for waste management in smart cities: A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 21(4), 1959–1989. [CrossRef]

- Fay, C. D., Corcoran, B., & Diamond, D. (2024). Green IoT Event Detection for Carbon-Emission Monitoring in Sensor Networks. Sensors, 24(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Ficili, I., Giacobbe, M., Tricomi, G., & Puliafito, A. (2025). From Sensors to Data Intelligence: Leveraging IoT, Cloud, and Edge Computing with AI. Sensors, 25(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J., & Quasney, E. (2017). Using autonomous robots to drive supply chain innovation. https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/Industries/industrial-construction/articles/autonomous-robots-supply-chain-innovation.html.

- Flak, J. (2020). Technologies for Sustainable Biomass Supply—Overview of Market Offering. Agronomy, 10(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Frank, A. G., Dalenogare, L. S., & Ayala, N. F. (2019). Industry 4.0 technologies: Implementation patterns in manufacturing companies. International Journal of Production Economics, 210, 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Fu, S., Tan, Y., & Xu, Z. (2023). Blockchain-Based Renewable Energy Certificate Trade for Low-Carbon Community of Active Energy Agents. Sustainability, 15(23), Article 23. [CrossRef]

- FuelCab India. (2024, October 21). Overcoming Biofuel Supply Chain Challenges: How FuelCab Can Drive Solutions? https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/overcoming-biofuel-supply-chain-challenges-how-fuelcab-can-drive-e0exc/.

- Fuller, A., Fan, Z., Day, C., & Barlow, C. (2020). Digital Twin: Enabling Technologies, Challenges and Open Research. IEEE Access, 8, 108952–108971. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q., Guo ,Shanshan, Liu ,Xiaofu, Manogaran ,Gunasekaran, Chilamkurti ,Naveen, & and Kadry, S. (2020). Simulation analysis of supply chain risk management system based on IoT information platform. Enterprise Information Systems, 14(9–10), 1354–1378. [CrossRef]

- GCAA & MOEI. (2022). National Sustainable Aviation Fuel Roadmap of the United Arab Emirates. https://u.ae/-/media/Documents-2024/UAE_National_SAF_Roadmap-(2).pdf.

- GE. (2019, July 30). GE’s Catalyst Can Help Hybrid Planes Take Flight By Generating Up To 1 Megawatt | GE Aerospace News. https://www.geaerospace.com/news/articles/product-technology/ges-catalyst-can-help-hybrid-planes-take-flight-generating-1-megawatt.

- Ghenai, C., Husein, L. A., Al Nahlawi, M., Hamid, A. K., & Bettayeb, M. (2022). Recent trends of digital twin technologies in the energy sector: A comprehensive review. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 54, 102837. [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M., Iranmanesh, M., Fathi, M., Rejeb, A., Foroughi, B., & Nikbin, D. (2024). Beyond Industry 4.0: A systematic review of Industry 5.0 technologies and implications for social, environmental and economic sustainability. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration. [CrossRef]

- Ghoroghi, A., Rezgui, Y., Petri, I., & Beach, T. (2022). Advances in application of machine learning to life cycle assessment: A literature review. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 27(3), 433–456. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I., Rosen, D., & Stucker, B. (2015). Direct Digital Manufacturing. In I. Gibson, D. Rosen, & B. Stucker (Eds.), Additive Manufacturing Technologies: 3D Printing, Rapid Prototyping, and Direct Digital Manufacturing (pp. 375–397). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y., Zhang, H., Morris, T., Zhang, C., & Alharithi, M. (2024). Waste Cooking Oil Recycling and the Potential Use of Blockchain Technology in the UK. Sustainability, 16(14), Article 14. [CrossRef]

- Gress, D. R., & Kalafsky, R. V. (2015). Geographies of production in 3D: Theoretical and research implications stemming from additive manufacturing. Geoforum, 60, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Grim, R. G., Tao, L., Abdullah, Z., Cortright, R., & Oakleaf, B. (2024). The Challenge Ahead: A Critical Perspective on Meeting U.S. Growth Targets for Sustainable Aviation Fuel (No. NREL/TP--5100-89327, 2331423, MainId:90106; p. NREL/TP--5100-89327, 2331423, MainId:90106). [CrossRef]

- Guo, G., He, Y., Jin, F., Mašek, O., & Huang, Q. (2023). Application of life cycle assessment and machine learning for the production and environmental sustainability assessment of hydrothermal bio-oil. Bioresource Technology, 379, 129027. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., & Liang, C. (2016). Blockchain application and outlook in the banking industry. Financial Innovation, 2(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- H2-View. (2023, September 22). ORLEN and Yokogawa sign MoU to develop SAF production technology. H2 View. https://www.h2-view.com/story/orlen-and-yokogawa-sign-mou-to-develop-saf-production-technology/2099400.article/.

- Halenar, I., Juhas, M., Juhasova, B., & Borkin, D. (2019). Virtualization of Production Using Digital Twin Technology. 2019 20th International Carpathian Control Conference (ICCC), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, A. W., Prastowo, H., & Pitana, T. (2021). Real-Time Fuel Consumption Monitoring System Integrated With Internet Of Things (IOT). Kapal: Jurnal Ilmu Pengetahuan Dan Teknologi Kelautan, 18(2), 88–100. [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnakumar, R., Dand, A., Nannapaneni, S., & Krishnan, K. (2019). Supervised Machine Learning Approach for Effective Supplier Classification. 2019 18th IEEE International Conference On Machine Learning And Applications (ICMLA), 240–245. [CrossRef]

- Haseltalab, V., Dutta, A., & Yang, S. (2023). On the 3D printed catalyst for biomass-bio-oil conversion: Key technologies and challenges. Journal of Catalysis, 417, 286–300. [CrossRef]

- Hassini, E. (2008). Supply Chain Optimization: Current Practices and Overview of Emerging Research Opportunities. INFOR: Information Systems and Operational Research, 46(2), 93–96. [CrossRef]

- He, X., Wang, N., Zhou, Q., Huang, J., Ramakrishna, S., & Li, F. (2024). Smart aviation biofuel energy system coupling with machine learning technology. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 189, 113914. [CrossRef]

- Heike Risse. (2024, April 1). Lab of the future: Automated robotic analysis of petroleum products. https://www.metrohm.com/en/discover/blog/2024/robotic-analysis-petro.html.

- Hofmann, E., Strewe, U. M., & Bosia, N. (2018). Supply Chain Finance and Blockchain Technology. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S. (2024). The Role of Natural Language Processing in Streamlining Supply Chain Communication. Business, Economics and Management. [CrossRef]

- Holmström, J., & Partanen, J. (2014). Digital manufacturing-driven transformations of service supply chains for complex products. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 19(4), 421–430. [CrossRef]

- Honeywell. (2024, September 23). Honeywell And USA Bioenergy To Partner On Automation At New Sustainable Aviation Fuel Refinery. https://www.honeywell.com/us/en/press/2024/09/honeywell-and-usa-bioenergy-to-partner-on-automation.

- Hu, J.-L., Li, Y., & Chew, J.-C. (2025). Industry 5.0 and Human-Centered Energy System: A Comprehensive Review with Socio-Economic Viewpoints. Energies, 18(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. H., Liu, P., Mokasdar, A., & Hou, L. (2013). Additive manufacturing and its societal impact: A literature review. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 67(5), 1191–1203. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T. A., & Zondervan, E. (2022). Process intensification and digital twin – the potential for the energy transition in process industries. In E. Zondervan (Ed.), Process Systems Engineering: For a Smooth Energy Transition (pp. 131–150). De Gruyter. https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110705201-005/html.

- IATA. (2020). Sustainable Aviation Fuel: Technical Certification.

- ICAO. (2013). ICAO ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT 2013 AVIATION AND CLIMATE CHANGE.

- ICAO. (2016). Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/Documents/EnvironmentalReports/2022/ENVReport2022_Art56.pdf.

- ICAO. (2019). Aviation Benefits Report-2019. ICAO. https://www.icao.int/sustainability/Documents/AVIATION-BENEFITS-2019-web.pdf.

- IEA. (2021, February 22). Biofuel production using petroleum refining technologies – Analysis. IEA. https://www.iea.org/articles/biofuel-production-using-petroleum-refining-technologies.

- Ikbarieh, A., Jin, W., Zhao, Y., Saha, N., Klinger, J. L., Xia, Y., & Dai, S. (2025). Machine Learning Assisted Cross-Scale Hopper Design for Flowing Biomass Granular Materials. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 13(16), 5838–5851. [CrossRef]

- Inan, I., Orhan, I., & Ekici, S. (2025). Fuel savings strategies for sustainable aviation in accordance with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). Energy, 320, 135159. [CrossRef]

- Insights, L. (2022, November 16). New blockchain registry for Sustainable Aviation Fuel backed by McKinsey, JP Morgan, Meta. Ledger Insights - Blockchain for Enterprise. https://www.ledgerinsights.com/blockchain-registry-for-sustainable-aviation-fuel-backed-by-mckinsey-jp-morgan-meta/.

- Islam, M. R., Oliullah, K., Kabir, M. M., Alom, M., & Mridha, M. F. (2023). Machine learning enabled IoT system for soil nutrients monitoring and crop recommendation. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 14, 100880. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. (2023). The Industry 5.0 framework: Viability-based integration of the resilience, sustainability, and human-centricity perspectives. International Journal of Production Research. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00207543.2022.2118892.

- Ivanov, D., & and Dolgui, A. (2021). A digital supply chain twin for managing the disruption risks and resilience in the era of Industry 4.0. Production Planning & Control, 32(9), 775–788. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D., Dolgui, A., & Sokolov, B. (2022). Cloud supply chain: Integrating Industry 4.0 and digital platforms in the “Supply Chain-as-a-Service.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 160, 102676. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, I., Ivanov, D., Dolgui, A., & Namdar, J. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence in supply chain and operations management: A capability-based framework for analysis and implementation. International Journal of Production Research. [CrossRef]

- Jahin, M. A., Shovon, M. S. H., Shin, J., Ridoy, I. A., & Mridha, M. F. (2024). Big Data—Supply Chain Management Framework for Forecasting: Data Preprocessing and Machine Learning Techniques. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 31(6), 3619–3645. [CrossRef]

- Jameel, A., & Gani, A. (2025). A Case Study on Integrating an AI System into the Fuel Blending Process in a Chemical Refinery. ChemEngineering, 9(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M., Haleem, A., Singh, R. P., Suman, R., & Khan, S. (2022). A review of Blockchain Technology applications for financial services. BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations, 2(3), 100073. [CrossRef]

- Jessen, J. (2024a, November 19). SAF: Helping Microsoft & DB Schenker Cut Supply Chain Carbon. https://sustainabilitymag.com/articles/db-schenker-microsoft-sustainable-logistics.

- Jessen, J. (2024b, November 26). Shell’s Blockchain Solution to Scaling SAF. https://climatetechdigital.com/tech-and-ai/shells-blockchain-solution-to-scaling-saf.

- Joseph, A. J., Kruger, K., & Basson, A. H. (2021). An Aggregated Digital Twin Solution for Human-Robot Collaboration in Industry 4.0 Environments. In T. Borangiu, D. Trentesaux, P. Leitão, O. Cardin, & S. Lamouri (Eds.), Service Oriented, Holonic and Multi-Agent Manufacturing Systems for Industry of the Future (pp. 135–147). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S., Gunasekaran ,Angappa, & and Arha, H. (2019). Understanding the Blockchain technology adoption in supply chains-Indian context. International Journal of Production Research, 57(7), 2009–2033. [CrossRef]

- Kandaramath Hari, T., Yaakob, Z., & Binitha, N. N. (2015). Aviation biofuel from renewable resources: Routes, opportunities and challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 42, 1234–1244. [CrossRef]

- Karkaria, V., Tsai, Y.-K., Chen, Y.-P., & Chen, W. (2025). An optimization-centric review on integrating artificial intelligence and digital twin technologies in manufacturing. Engineering Optimization, 57(1), 161–207. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H. T. (2021, March 15). Advanced BioFuels USA – Fighting Fraud with Tech – RSB, Bioledger Build up Blockchain for Biofuels Traceability. https://advancedbiofuelsusa.info/fighting-fraud-with-tech-rsb-bioledger-build-up-blockchain-for-biofuels-traceability.

- Khan, M. R., Amin, J. M., & Hosen, M. M. (2024). DIGITAL TWIN-DRIVEN OPTIMIZATION OF BIOENERGY PRODUCTION FROM WASTE MATERIALS (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 5063886). Social Science Research Network. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y., Su’ud, M. B. M., Alam, M. M., Ahmad, S. F., Ahmad (Ayassrah), A. Y. A. B., & Khan, N. (2023). Application of Internet of Things (IoT) in Sustainable Supply Chain Management. Sustainability, 15(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J., Pitt, L., & Berthon, P. (2015). Disruptions, decisions, and destinations: Enter the age of 3-D printing and additive manufacturing. Business Horizons, 58(2), 209–215. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Kim, M., Im, S., & Choi, D. (2021). Competitiveness of E Commerce Firms through ESG Logistics. Sustainability, 13(20), Article 20. [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, M., & Ruiner, C. (2022, September 1). Artificial intelligence, robotics, and logistics employment: The human factor in digital logistics. | EBSCOhost. [CrossRef]

- Koskinopoulou, M., Raptopoulos, F., Papadopoulos, G., Mavrakis, N., & Maniadakis, M. (2021). Robotic Waste Sorting Technology: Toward a Vision-Based Categorization System for the Industrial Robotic Separation of Recyclable Waste. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 28(2), 50–60. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine. [CrossRef]

- Kouhizadeh, M., & Sarkis, J. (2020). Blockchain Characteristics and Green Supply Chain Advancement. In Global Perspectives on Green Business Administration and Sustainable Supply Chain Management (pp. 93–109). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D., Kumar, S., & Joshi, A. (2023). Assessing the viability of blockchain technology for enhancing court operations. International Journal of Law and Management, 65(5), 425–439. [CrossRef]

- Kuzhagaliyeva, N., Horváth, S., Williams, J., Nicolle, A., & Sarathy, S. M. (2022). Artificial intelligence-driven design of fuel mixtures. Communications Chemistry, 5(1), 111. [CrossRef]

- Lakhouit, A. (2025). Revolutionizing urban solid waste management with AI and IoT: A review of smart solutions for waste collection, sorting, and recycling. Results in Engineering, 25, 104018. [CrossRef]

- LanzaJet. (2024, April 22). LanzaJet Announces Investment from Microsoft’s Climate Innovation…. LanzaJet. https://www.lanzajet.com/news-insights/lanzajet-announces-investment-from-microsofts-climate-innovation-fund-supporting-continued-company-growth.

- Lee, I., & Lee, K. (2015). The Internet of Things (IoT): Applications, investments, and challenges for enterprises. Business Horizons, 58(4), 431–440. [CrossRef]

- Lennard, Z. (2025). FEDECOM: Enabling cross-border energy exchange by federating energy communities. Open Research Europe, 4, 269. [CrossRef]

- Liao, M., & Yao, Y. (2021). Applications of artificial intelligence-based modeling for bioenergy systems: A review. GCB Bioenergy, 13(5), 774–802. [CrossRef]

- Lim, H. R., Khoo, K. S., Chew, K. W., Teo, M. Y. M., Ling, T. C., Alharthi, S., Alsanie, W. F., & Show, P. L. (2024). Evaluation of Real-Time Monitoring on the Growth of Spirulina Microalgae: Internet of Things and Microalgae Technologies. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 11(2), 3274–3281. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. L., Wang, W. M., Guo, H., Barenji, A. V., Li, Z., & Huang, G. Q. (2020). Industrial blockchain based framework for product lifecycle management in industry 4.0. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 63, 101897. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., & Yang, X. (2024). Insight of low flammability limit on sustainable aviation fuel blend and prediction by ANN model. Energy and AI, 18, 100423. [CrossRef]

- Loce, R. P., Bernal, E. A., Wu, W., & Bala, R. (2013). Computer vision in roadway transportation systems: A survey. Journal of Electronic Imaging, 22(4), 041121. [CrossRef]

- Luman, R. (2024). BLOCKCHAIN DRIVEN SUPPLY CHAIN TRANSPARENCY IN SAF PRODUCTION: ENHANCING TRACEABILITY AND REGULATORY COMPLIANCE. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science, 15(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C., Zhou, Y., Yan, W., He, W., Liu, Q., Li, Z., Wang, H., Li, G., Yang, Y., Han, W., Lu, C., & Li, X. (2022). Predominant Catalytic Performance of Nickel Nanoparticles Embedded into Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dot-Based Nanosheets for the Nitroreduction of Halogenated Nitrobenzene. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 10(25), 8162–8171. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S., Ding, W., Liu, Y., Ren, S., & Yang, H. (2022). Digital twin and big data-driven sustainable smart manufacturing based on information management systems for energy-intensive industries. Applied Energy, 326, 119986. [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D. J. (2011). A Framework for Conceptual Contributions in Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 136–154. [CrossRef]

- Magazzeni, D., McBurney, P., & Nash, W. (2017). Validation and Verification of Smart Contracts: A Research Agenda. Computer, 50(9), 50–57. [CrossRef]

- Mahey, H. (2020). Robotic Process Automation with Automation Anywhere: Techniques to fuel business productivity and intelligent automation using RPA. Packt Publishing Ltd.

- Maiti, A., Raza, A., Kang, B. H., & Hardy, L. (2019). Estimating Service Quality in Industrial Internet-of-Things Monitoring Applications With Blockchain. IEEE Access, 7, 155489–155503. [CrossRef]

- Mana, A. A., Allouhi, A., Hamrani, A., Rehman, S., el Jamaoui, I., & Jayachandran, K. (2024). Sustainable AI-based production agriculture: Exploring AI applications and implications in agricultural practices. Smart Agricultural Technology, 7, 100416. [CrossRef]

- MarketsandMarkets. (2025, January). Overcoming AI Challenges in Aviation Fuel Market. https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/ResearchInsight/ai-impact-analysis-on-aviation-fuel-industry.asp.

- Martinez-Valencia, L., Garcia-Perez, M., & Wolcott, M. P. (2021). Supply chain configuration of sustainable aviation fuel: Review, challenges, and pathways for including environmental and social benefits. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 152, 111680. [CrossRef]

- MBIE. (2021). SAF Consortium Roadmap. New Zealand’s Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment. https://p-airnz.com/cms/assets/PDFs/Airnz-sustainable-aviation-fuel-in-new-zealand-may-2021.pdf.

- McKinsey. (2024). Securing a sustainable fuel supply: Airline strategies | McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/aerospace-and-defense/our-insights/how-the-aviation-industry-could-help-scale-sustainable-fuel-production?

- Meena, M., Shubham, S., Paritosh, K., Pareek, N., & Vivekanand, V. (2021). Production of biofuels from biomass: Predicting the energy employing artificial intelligence modelling. Bioresource Technology, 340, 125642. [CrossRef]

- Merlo, A. L. C., Mendonça, D. S., Santos, J., Carvalho, S. T., Guerra, R., & Brandão, D. (2025). Blockchain for the carbon market: A literature review. Discover Environment, 3(1), 68. [CrossRef]

- Metzger, D. F., Klahn, C., & Dittmeyer, R. (2023). Downsizing Sustainable Aviation Fuel Production with Additive Manufacturing—An Experimental Study on a 3D printed Reactor for Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis. Energies, 16(19), Article 19. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. H., Tifft, S. M., Wiatrowski, M. R., Benavides, P. T., Huq, N. A., Christensen, E. D., Alleman, T., Hays, C., Luecke, J., Kneucker, C. M., Haugen, S. J., Sànchez I Nogué, V., Karp, E. M., Hawkins, T. R., Singh, A., & Vardon, D. R. (2022). Screening and evaluation of biomass upgrading strategies for sustainable transportation fuel production with biomass-derived volatile fatty acids. iScience, 25(11), 105384. [CrossRef]

- MIT Technology Review. (2023, November 28). Procurement in the age of AI. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/11/28/1083628/procurement-in-the-age-of-ai/.

- Mohr, S., & Khan, O. (2015). 3D Printing and Its Disruptive Impacts on Supply Chains of the Future. Technology Innovation Management Review, 5(11), 20–25.

- Morgan, T. R., Jr, R. G. R., & Ellinger, A. E. (2018). Supplier transparency: Scale development and validation. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 29(3), 959–984. [CrossRef]

- Moshebah, O. Y., Rodríguez-González, S., & González, A. D. (2024). A Max–Min Fairness-Inspired Approach to Enhance the Performance of Multimodal Transportation Networks. Sustainability, 16(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Moyer, P. (2021, September 22). Market data distribution & consumption through cloud & AI. Google Cloud Blog. https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/financial-services/market-data-distribution--consumption-through-cloud--ai.

- Muldbak, M., Gargalo, C., Krühne, U., Udugama, I., & Gernaey, K. V. (2022). Digital Twin of a pilot-scale bio-production setup: 14th International Symposium on Process Systems Engineering (PSE 2021+). Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Process Systems Engineering, 1417–1422. [CrossRef]

- National Agricultural Library. (2021). Digital twins for the optimization of agrifood value chain processes and the supply of quality biomass for bio-processing | National Agricultural Library. https://www.nal.usda.gov/research-tools/food-safety-research-projects/digital-twins-optimization-agrifood-value-chain.

- Naveed, M. H., Khan, M. N. A., Mukarram, M., Naqvi, S. R., Abdullah, A., Haq, Z. U., Ullah, H., & Mohamadi, H. A. (2024). Cellulosic biomass fermentation for biofuel production: Review of artificial intelligence approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 189, 113906. [CrossRef]

- Norazmi, A. (2023). SAF accounting based on robust chain-of-custody approaches.

- NREL. (2024, January 29). On the Ground in Colorado, NREL Is Simulating Sustainable Aviation Fuel Combustion During Flight | NREL. https://www.nrel.gov/news/detail/features/2024/on-the-ground-in-colorado-nrel-is-simulating-sustainable-aviation-fuel-combustion-during-flight.

- NREL. (2025, June 21). Engage Energy Modeling Tool | State, Local, and Tribal Governments | NREL. https://www.nrel.gov/state-local-tribal/engage-energy-modeling-tool.

- Núñez-Merino, M., Maqueira-Marín ,Juan Manuel, Moyano-Fuentes ,José, & and Martínez-Jurado, P. J. (2020). Information and digital technologies of Industry 4.0 and Lean supply chain management: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Production Research, 58(16), 5034–5061. [CrossRef]

- Nyman, H. J., & Sarlin, P. (2014). From Bits to Atoms: 3D Printing in the Context of Supply Chain Strategies. 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 4190–4199. [CrossRef]

- Obi Reddy, G. P., Dwivedi, B. S., & Ravindra Chary, G. (2023). Applications of Geospatial and Big Data Technologies in Smart Farming. In K. Pakeerathan (Ed.), Smart Agriculture for Developing Nations: Status, Perspectives and Challenges (pp. 15–31). Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, M. J., Langton, D., & O’Hare, G. M. P. (2019). Edge computing: A tractable model for smart agriculture? Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture, 3, 42–51. [CrossRef]

- Okolie, J. A. (2024). Introduction of machine learning and artificial intelligence in biofuel technology. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 47, 100928. [CrossRef]

- Okolie, J. A., Moradi, K., Rogachuk, B. E., Narra, B. N., Ogbaga, C. C., Okoye, P. U., & Adeleke, A. A. (2024). Data-Driven Framework for the Techno-Economic Assessment of Sustainable Aviation Fuel from Pyrolysis. BioEnergy Research, 18(1), 6. [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D. B., Fapohunda, O., Wada, O. Z., Usman, S. O., Ige, A. O., Ajisafe, O., & Oladapo, B. I. (2024). Smart waste management: A paradigm shift enabled by artificial intelligence. Waste Management Bulletin, 2(2), 244–263. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, T. L., & Tomlin, B. (2019). Industry 4.0: Opportunities and Challenges for Operations Management. MANUFACTURING & SERVICE OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT. [CrossRef]

- On the Ground in Colorado, NREL Is Simulating Sustainable Aviation Fuel Combustion During Flight. (n.d.). Retrieved March 9, 2025, from https://www.nrel.gov/news/features/2024/on-the-ground-in-colorado-nrel-is-simulating-sustainable-aviation-fuel-combustion-during-flight.html.

- Oriekhoe, O. I., Oyeyemi, O. P., Bello, B. G., Omotoye, G. B., Daraojimba, A. I., Adefemi, A., Oriekhoe, O. I., Oyeyemi, O. P., Bello, B. G., Omotoye, G. B., Daraojimba, A. I., & Adefemi, A. (2024). Blockchain in supply chain management: A review of efficiency, transparency, and innovation. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 11(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Osman, E. (2023, May 6). Edge Computing for the Aviation Sector. Zsah. https://www.zsah.net/edge-computing-in-aviation-sector/.

- Owusu, W. A., & Marfo, S. A. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Application in Bioethanol Production. International Journal of Energy Research, 2023(1), 7844835. [CrossRef]

- Painuly, S., & Sharma, S. (2024). Natural Language Processing Techniques for e-Healthcare Supply Chain Management System. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Systems and Intelligent Computing (ESIC), 11–16. [CrossRef]

- Palander, T., Tokola, T., Borz, S. A., & Rauch, P. (2024). Forest Supply Chains During Digitalization: Current Implementations and Prospects in Near Future. Current Forestry Reports, 10(3), 223–238. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S. L., & Nishant, R. (2023). Artificial intelligence for digital sustainability: An insight into domain-specific research and future directions. International Journal of Information Management, 72, 102668. [CrossRef]

- Pansare, R., Yadav, G., & Nagare, M. R. (2021). Reconfigurable manufacturing system: A systematic bibliometric analysis and future research agenda. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 33(3), 543–574. [CrossRef]

- Parhamfar, M. (2024). Towards green airports: Factors influencing greenhouse gas emissions and sustainability through renewable energy. Next Research, 1(2), 100060. [CrossRef]

- Park, A., & Li, H. (2021). The Effect of Blockchain Technology on Supply Chain Sustainability Performances. Sustainability, 13(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., & Kang, D. (2024). Artificial Intelligence and Smart Technologies in Safety Management: A Comprehensive Analysis Across Multiple Industries. Applied Sciences, 14(24), Article 24. [CrossRef]

- Patro, P. K., Jayaraman ,Raja, Acquaye ,Adolf, Salah ,Khaled, & and Musamih, A. (2024). Blockchain-based solution to enhance carbon footprint traceability, accounting, and offsetting in the passenger aviation industry. International Journal of Production Research, 0(0), 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Patro, P. K., Jayaraman ,Raja, Acquaye ,Adolf, Salah ,Khaled, & and Musamih, A. (2025). Blockchain-based solution to enhance carbon footprint traceability, accounting, and offsetting in the passenger aviation industry. International Journal of Production Research, 0(0), 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Pattison, I. (2017, April 27). 4 characteristics that set blockchain apart | Architecting the Cloud. https://architectingthecloud.com/2017/04/27/4-characteristics-that-set-blockchain-apart/.

- Petre, E., Selişteanu, D., & Roman, M. (2021). Advanced nonlinear control strategies for a fermentation bioreactor used for ethanol production. Bioresource Technology, 328, 124836. [CrossRef]

- Petrick, I. J., & Simpson, T. W. (2013). 3D Printing Disrupts Manufacturing: How Economies of One Create New Rules of Competition. Research-Technology Management, 56(6), 12–16. [CrossRef]

- Pidatala, V. R., Lei, M., Choudhary, H., Petzold, C. J., Martin, H. G., Simmons, B. A., Gladden, J. M., & Rodriguez, A. (2024). A miniaturized feedstocks-to-fuels pipeline for screening the efficiency of deconstruction and microbial conversion of lignocellulosic biomass. PLOS ONE, 19(10), e0305336. [CrossRef]

- Popowicz, M., Katzer, N. J., Kettele, M., Schöggl, J.-P., & Baumgartner, R. J. (2025). Digital technologies for life cycle assessment: A review and integrated combination framework. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 30(3), 405–428. [CrossRef]

- Qazi, A. M., Mahmood, S. H., Haleem, A., Bahl, S., Javaid, M., & Gopal, K. (2022). The impact of smart materials, digital twins (DTs) and Internet of things (IoT) in an industry 4.0 integrated automation industry. Materials Today: Proceedings, 62, 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q., & Tao, F. (2018). Digital Twin and Big Data Towards Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0: 360 Degree Comparison. IEEE Access, 6, 3585–3593. [CrossRef]

- Qudrat-Ullah, H. (2025). A Thematic Review of AI and ML in Sustainable Energy Policies for Developing Nations. Energies, 18(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Rachana Harish, A., Liu, X. L., Li, M., Zhong, R. Y., & Huang, G. Q. (2023). Blockchain-enabled digital assets tokenization for cyber-physical traceability in E-commerce logistics financing. Computers in Industry, 150, 103956. [CrossRef]

- Rachana Harish, A., Liu, X. L., Zhong, R. Y., & Huang, G. Q. (2021). Log-flock: A blockchain-enabled platform for digital asset valuation and risk assessment in E-commerce logistics financing. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 151, 107001. [CrossRef]

- Raman, R., Gunasekar, S., Dávid, L. D., Rahmat, A. F., & Nedungadi, P. (2024). Aligning sustainable aviation fuel research with sustainable development goals: Trends and thematic analysis. Energy Reports, 12, 2642–2652. [CrossRef]

- Rauchs, M., Glidden, A., Gordon, B., Pieters, G. C., Recanatini, M., Rostand, F., Vagneur, K., & Zhang, B. Z. (2018). Distributed Ledger Technology Systems: A Conceptual Framework (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3230013). Social Science Research Network. [CrossRef]

- Rayes, A., & Salam, S. (2017). Internet of Things From Hype to Reality. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Rayes, A., & Salam, S. (2022). The Things in IoT: Sensors and Actuators. In A. Rayes & S. Salam (Eds.), Internet of Things from Hype to Reality: The Road to Digitization (pp. 63–82). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A., Keogh, J. G., Wamba, S. F., & Treiblmaier, H. (2021). The potentials of augmented reality in supply chain management: A state-of-the-art review. Management Review Quarterly, 71(4), 819–856. [CrossRef]

- Remko Van Hoek, Michael DeWitt, Mary Lacity, & Travis Johnson. (2022, November 8). How Walmart Automated Supplier Negotiations. https://hbr.org/2022/11/how-walmart-automated-supplier-negotiations.

- Ribeiro, J., Lima, R., Eckhardt, T., & Paiva, S. (2021). Robotic Process Automation and Artificial Intelligence in Industry 4.0 – A Literature review. Procedia Computer Science, 181, 51–58. [CrossRef]

- Richey, R. G., Chowdhury, S., Davis-Sramek, B., Giannakis, M., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2023). Artificial intelligence in logistics and supply chain management: A primer and roadmap for research. Journal of Business Logistics, 44(4), 532–549. [CrossRef]

- RMI. (2022, November 16). RMI Partners with Energy Web Foundation to Build Sustainable Aviation Fuel Certificate Registry, as Part of Ongoing Decarbonization Work with the Sustainable Aviation Buyers Alliance. RMI. https://rmi.org/press-release/rmi-partners-with-energy-web-foundation-to-build-sustainable-aviation-fuel-certificate-registry/.

- Roeck, D., Sternberg ,Henrik, & and Hofmann, E. (2020). Distributed ledger technology in supply chains: A transaction cost perspective. International Journal of Production Research, 58(7), 2124–2141. [CrossRef]

- Rogachuk, B. E., Prigmore, S. M., Ogbaga, C. C., & Okolie, J. A. (2025). Public Perception and Awareness of Sustainable Aviation Fuel in South Central United States. Sustainability, 17(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H., Baricz, N., & Pawar, K. S. (2016). 3D printing services: Classification, supply chain implications and research agenda. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 46(10), 886–907. [CrossRef]

- Romeiko, X. X., Zhang, X., Pang, Y., Gao, F., Xu, M., Lin, S., & Babbitt, C. (2024). A review of machine learning applications in life cycle assessment studies. Science of The Total Environment, 912, 168969. [CrossRef]

- Ronaghi, M. H. (2021). A blockchain maturity model in agricultural supply chain. Information Processing in Agriculture, 8(3), 398–408. [CrossRef]

- Roy, R. B., Mishra, D., Pal, S. K., Chakravarty, T., Panda, S., Chandra, M. G., Pal, A., Misra, P., Chakravarty, D., & Misra, S. (2020). Digital twin: Current scenario and a case study on a manufacturing process. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 107(9), 3691–3714. [CrossRef]

- RSB. (n.d.).

- Sallam, K., Mohamed, M., & Mohamed, A. W. (2023). Internet of Things (IoT) in Supply Chain Management: Challenges, Opportunities, and Best Practices. Sustainable Machine Intelligence Journal, 2, (3):1-32. [CrossRef]

- Sans, V. (2020). Emerging trends in flow chemistry enabled by 3D printing: Robust reactors, biocatalysis and electrochemistry. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 25, 100367. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C. H. dos, de Queiroz ,José Antônio, Leal ,Fabiano, & and Montevechi, J. A. B. (2022). Use of simulation in the industry 4.0 context: Creation of a Digital Twin to optimise decision making on non-automated process. Journal of Simulation, 16(3), 284–297. [CrossRef]

- Schmieg, B., Döbber, J., Kirschhöfer, F., Pohl, M., & Franzreb, M. (2019). Advantages of Hydrogel-Based 3D-Printed Enzyme Reactors and Their Limitations for Biocatalysis. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 6. [CrossRef]

- Serna, A., Soroa, A., & Agerri, R. (2021). Applying Deep Learning Techniques for Sentiment Analysis to Assess Sustainable Transport. Sustainability, 13(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M., Wever, M., & Espig, M. (2025). A Framework for Assessing the Potential of Artificial Intelligence in the Circular Bioeconomy. Sustainability, 17(8), Article 8. [CrossRef]

- Sharabati, A.-A. A., & Jreisat, E. R. (2024). Blockchain Technology Implementation in Supply Chain Management: A Literature Review. Sustainability, 16(7), Article 7. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M., Sehrawat, R., Luthra, S., Daim, T., & Bakry, D. (2024). Moving Towards Industry 5.0 in the Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Sector: Challenges and Solutions for Germany. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71, 13757–13774. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V., Tsai, M.-L., Chen, C.-W., Sun, P.-P., Nargotra, P., & Dong, C.-D. (2023). Advances in machine learning technology for sustainable biofuel production systems in lignocellulosic biorefineries. Science of The Total Environment, 886, 163972. [CrossRef]

- Sharno, M. A., & Hiloidhari, M. (2024). Social sustainability of biojet fuel for net zero aviation. Energy for Sustainable Development, 79, 101419. [CrossRef]

- Sheik, A. G., Kumar, A., Ansari, F. A., Raj, V., Peleato, N. M., Patan, A. K., Kumari, S., & Bux, F. (2024). Reinvigorating algal cultivation for biomass production with digital twin technology—A smart sustainable infrastructure. Algal Research, 84, 103779. [CrossRef]

- Shell. (2022). Creating integrated digital ecosystems | Shell Global. https://www.shell.com/what-we-do/digitalisation/digitalisation-in-action/creating-integrated-digital-ecosystems.html.

- Shi, Z., Ferrari, G., Ai, P., Marinello, F., & Pezzuolo, A. (2023). Artificial Intelligence for Biomass Detection, Production and Energy Usage in Rural Areas: A review of Technologies and Applications. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 60, 103548. [CrossRef]

- Sierla, S., Sorsamäki, L., Azangoo, M., Villberg, A., Hytönen, E., & Vyatkin, V. (2020). Towards Semi-Automatic Generation of a Steady State Digital Twin of a Brownfield Process Plant. Applied Sciences, 10(19), Article 19. [CrossRef]

- Sipthorpe, A., Brink, S., Van Leeuwen, T., & Staffell, I. (2022). Blockchain solutions for carbon markets are nearing maturity. One Earth, 5(7), 779–791. [CrossRef]

- SkyNRG. (2024). SUSTAINABLE AVIATION FUEL ARKE OUTLOOK. https://www.efuel-alliance.eu/fileadmin/Downloads/SAF-Market-Outlook-2024-Summary.pdf.

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. [CrossRef]

- Staples, M. D., Malina, R., Suresh, P., Hileman, J. I., & Barrett, S. R. H. (2018). Aviation CO2 emissions reductions from the use of alternative jet fuels. Energy Policy, 114, 342–354. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, W. (2023). Robotic Process Automation in Supply Chain. European Journal of Supply Chain Management, 1(1), Article 1.

- Subramanian, G., & Thampy, A. S. (2021). Implementation of Hybrid Blockchain in a Pre-Owned Electric Vehicle Supply Chain. IEEE Access, 9, 82435–82454. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, G., Thampy, A. S., Ugwuoke, N. V., & Ramnani, B. (2021). Crypto Pharmacy – Digital Medicine: A Mobile Application Integrated With Hybrid Blockchain to Tackle the Issues in Pharma Supply Chain. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society, 2, 26–37. [CrossRef]

- Swinkels, L. (2024). Trading carbon credit tokens on the blockchain. International Review of Economics & Finance, 91, 720–733. [CrossRef]

- Syafrudin, M., Alfian, G., Fitriyani, N. L., & Anshari, M. (2024). Applied Artificial Intelligence for Sustainability. Sustainability, 16(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Tanzil, A. H., Brandt, K., Zhang, X., Wolcott, M., Stockle, C., & Garcia-Perez, M. (2021). Production of Sustainable Aviation Fuels in Petroleum Refineries: Evaluation of New Bio-Refinery Concepts. Frontiers in Energy Research, 9. [CrossRef]

- Tatham, P., Loy, J., & Peretti, U. (2015). Three dimensional printing – a key tool for the humanitarian logistician? Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 5(2), 188–208. [CrossRef]

- Thanasi-Boçe, M., & Hoxha, J. (2025). Blockchain for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 17(11), Article 11. [CrossRef]

- Thepchalerm, T., & Pinsuwan, S. (2025). CEO voices on sustainable aviation: An analysis of environmental communication in the airline industry. Green Technologies and Sustainability, 3(3), 100194. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Birtchnell, John Urry, Chloe Cook, & Andrew Curry. (2012). Freight Miles: The Impacts of 3D Printing on Transport and Society. ESRC Project ES/J007455/1. https://www.academia.edu/3628536/Freight_Miles_The_Impacts_of_3D_Printing_on_Transport_and_Society.

- Tienin, B. W., Cui ,Guolong, Ukwuoma ,Chiagoziem Chima, Talla Nana ,Yannick Abel, Mba Esidang ,Roldan, & and Moniz Moreira, E. Z. (2024). MS3Net: A deep ensemble learning approach for ship classification in heterogeneous remote sensing data. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 45(3), 748–771. [CrossRef]

- Tirkolaee, E. B., Sadeghi, S., Mooseloo, F. M., Vandchali, H. R., & Aeini, S. (2021). Application of Machine Learning in Supply Chain Management: A Comprehensive Overview of the Main Areas. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2021(1), 1476043. [CrossRef]

- Tönnissen, S., & Teuteberg, F. (2020). Analysing the impact of blockchain-technology for operations and supply chain management: An explanatory model drawn from multiple case studies. International Journal of Information Management, 52, 101953. [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367. [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R. J. (2016). Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Using the Past and Present to Explore the Future. Human Resource Development Review, 15(4), 404–428. [CrossRef]

- Treleaven, P., Gendal Brown, R., & Yang, D. (2017). Blockchain Technology in Finance. Computer, 50(9), 14–17. [CrossRef]

- Ucar, A., Karakose, M., & Kırımça, N. (2024). Artificial Intelligence for Predictive Maintenance Applications: Key Components, Trustworthiness, and Future Trends. Applied Sciences, 14(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Ukoba, K., Olatunji, K. O., Adeoye, E., Jen, T.-C., & Madyira, D. M. (2024). Optimizing renewable energy systems through artificial intelligence: Review and future prospects. Energy & Environment, 35(7), 3833–3879. [CrossRef]

- Velarde, C. (2019). Sustainable Aviation Fuel ‘Monitoring System.’ European Union Aviation Safety Agency.

- Verdouw, C. N., Robbemond ,R.M., Verwaart ,T., Wolfert ,J., & and Beulens, A. J. M. (2018). A reference architecture for IoT-based logistic information systems in agri-food supply chains. Enterprise Information Systems, 12(7), 755–779. [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Ch, W., Navarro, A. M., & Sanchez-Viteri, S. (2024). Optimization of inventory management through computer vision and machine learning technologies. Intelligent Systems with Applications, 24, 200438. [CrossRef]

- Viola, J., & Chen, Y. (2020). Digital Twin Enabled Smart Control Engineering as an Industrial AI: A New Framework and Case Study. 2020 2nd International Conference on Industrial Artificial Intelligence (IAI), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- von Krogh, G., Roberson, Q., & Gruber, M. (2023). Recognizing and Utilizing Novel Research Opportunities with Artificial Intelligence. Academy of Management Journal, 66(2), 367–373. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Ting, Z. J., & Zhao, M. (2024). Sustainable aviation fuels: Key opportunities and challenges in lowering carbon emissions for aviation industry. Carbon Capture Science & Technology, 13, 100263. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Chaffart, D., & Ricardez-Sandoval, L. A. (2019). Modelling and optimization of a pilot-scale entrained-flow gasifier using artificial neural networks. Energy, 188, 116076. [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. J., Machado, P. G., Da Silva, A. V., Saltar, Y., Ribeiro, C. O., Nascimento, C. A. O., & Dowling, A. W. (2024). Sustainable aviation fuel technologies, costs, emissions, policies, and markets: A critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 449, 141472. [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. J., Machado, P. G., da Silva, A. V., Saltar, Y., Ribeiro, C. O., Nascimento, C. A. O., & Dowling, A. W. (2024). Sustainable aviation fuel technologies, costs, emissions, policies, and markets: A critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 449, 141472. [CrossRef]

- WEF. (2024, September 20). Innovations in sustainability: XR in business and climate strategies. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/09/xr-technologies-redefining-business-climate-strategies-innovation/.

- Weyer, S., Schmitt, M., Ohmer, M., & Gorecky, D. (2015). Towards Industry 4.0—Standardization as the crucial challenge for highly modular, multi-vendor production systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 48(3), 579–584. [CrossRef]

- Wheelock, C. (2025, May 14). The Business Case for AI-Powered Sustainability. Canopy Edge. https://canopyedge.com/2025/05/the-business-case-for-ai-powered-sustainability/.

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. [CrossRef]

- Woo, J., Fatima, R., Kibert, C. J., Newman, R. E., Tian, Y., & Srinivasan, R. S. (2021). Applying blockchain technology for building energy performance measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) and the carbon credit market: A review of the literature. Building and Environment, 205, 108199. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2021, September 20). Aviation’s flight path to a net-zero future. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2021/09/aviation-flight-path-to-net-zero-future/.

- World Economic Forum. (2023, November 30). How can AI make aviation more sustainable? World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/11/3-ways-ai-can-revolutionize-sustainable-aviation/.

- Wu, C., Wang, Y., & Tao, L. (2024). Machine learning-enabled techno-economic uncertainty analysis of sustainable aviation fuel production pathways. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances, 20, 100650. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., Xiao, G., Huang, D., Zhang, X., Ye, D., & Weng, H. (2025). Edge Computing-Based Machine Vision for Non-Invasive and Rapid Soft Sensing of Mushroom Liquid Strain Biomass. Agronomy, 15(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Pero, M. E. P., Ciccullo, F., & Sianesi, A. (2021). On relating big data analytics to supply chain planning: Towards a research agenda. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 51(6), 656–682. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. D., He, W., & Li, S. (2014). Internet of Things in Industries: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 10(4), 2233–2243. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V. S., Singh, A. R., Raut, R. D., Mangla, S. K., Luthra, S., & Kumar, A. (2022). Exploring the application of Industry 4.0 technologies in the agricultural food supply chain: A systematic literature review. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 169, 108304. [CrossRef]

- Yan, G., Yang, X., Shaban, M., Abed, A. M., Abdullaev, S., Alhomayani, F. M., Khan, M. N., Alkhalaf, S., Alturise, F., & Albalawi, H. (2025). Artificial intelligence-powered study of a waste-to-energy system through optimization by regression-centered machine learning algorithms. Energy, 320, 135142. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Fu, Z.-Y., Zhan, D.-C., Liu, Z.-B., & Jiang, Y. (2021). Semi-Supervised Multi-Modal Multi-Instance Multi-Label Deep Network with Optimal Transport. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 33(2), 696–709. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Boehm, R. C., Bell, D. C., & Heyne, J. S. (2023). Maximizing Sustainable aviation fuel usage through optimization of distillation cut points and blending. Fuel, 353, 129136. [CrossRef]

- Yar, M. A., Hamdan, M., Anshari, M., Fitriyani, N. L., & Syafrudin, M. (2024). Governing with Intelligence: The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Policy Development. Information, 15(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Yi, H. (2022). A traceability method of biofuel production and utilization based on blockchain. Fuel, 310, 122350. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W., Patros, P., Young, B., Klinac, E., & Walmsley, T. G. (2022). Energy digital twin technology for industrial energy management: Classification, challenges and future. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 161, 112407. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Huang ,Ganquan, & and Guo, X. (2021). Financing strategy analysis for a multi-sided platform with blockchain technology. International Journal of Production Research, 59(15), 4513–4532. [CrossRef]

- Zahraee, S. M., Shiwakoti, N., & Stasinopoulos, P. (2022). Agricultural biomass supply chain resilience: COVID-19 outbreak vs. sustainability compliance, technological change, uncertainties, and policies. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain, 4, 100049. [CrossRef]

- Zamani, E. D., Smyth, C., Gupta, S., & Dennehy, D. (2023). Artificial intelligence and big data analytics for supply chain resilience: A systematic literature review. Annals of Operations Research, 327(2), 605–632. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Zhang, L., & Konz, N. (2023). Computer Vision Techniques in Manufacturing. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, 53(1), 105–117. [CrossRef]

- Židek, K., Piteľ, J., Adámek, M., Lazorík, P., & Hošovský, A. (2020). Digital Twin of Experimental Smart Manufacturing Assembly System for Industry 4.0 Concept. Sustainability, 12(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Zonta, T., da Costa, C. A., da Rosa Righi, R., de Lima, M. J., da Trindade, E. S., & Li, G. P. (2020). Predictive maintenance in the Industry 4.0: A systematic literature review. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 150, 106889. [CrossRef]

| Year | Initiative / Program | Country/Org | Objective | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | SAF Grand Challenge Roadmap | US (DOE, DOT, USDA, EPA) |

|

(DOE, USDA, DOT, and EPA, 2022) |

| 2021 | Canada Clean Fuel Regulations | Canada |

|

(CFR, 2022) |

| 2021 | Japan SAF Roadmap | Japan |

|

(SkyNRG, 2024) |

| 2021 | SAF Consortium Roadmap | New Zealand |

|

(MBIE, 2021) |

| 2022 | National Sustainable Aviation Fuel Roadmap |

United Arab Emirates |

|

(GCAA & MOEI, 2022) |

| 2023 | Sustainable Aviation Fuel Roadmap | Australia |

|

(CSIRO, 2023) |

| 2024 | Singapore Sustainable Air Hub Blueprint | Singapore |

|

(CASS, 2024) |

| Technology | Definition | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Distributed ledger technology (DLT) |

|

|

| Smart contract |

|

|

| Tokenization |

|

|

| Technology | Definition | Application |

|---|---|---|

| ML |

|

|

| NLP |

|

|

| Computer vision |

|

|

| Robotic Process Automation (RPA) |

|

|

| Generative AI (GAI) |

|

|

| IoT Layers and Features | Applications |

|---|---|

|

Sensing Layer includes RFID tags, sensors, actuators, and other intelligent devices (Lee & Lee, 2015). A foundational layer. Enables identification, tracking, and collection of data from physical objects (Rayes & Salam, 2022). |

|

|

Network Layer transmits information gathered at sensing layer via wired or wireless networks (Alyahya et al., 2016; Rayes & Salam, 2017). Utilizes wireless networks and sensor-enabled RFID technology to provide real-time visibility. | |

|

Service Layer uses middleware to interact between data services and applications (Lee and Lee, 2015, Borgia, 2014). Integrates cloud computing to allow sensing devices to interface with IoT applications (Gubbi et al., 2013). | |

|

Interface Layer facilitates user interaction with the IoT system (Taj et al., 2023; Choi et al., 2015). Presents data in an accessible format and functions as an interactive gateway between end-users and IoT-enabled devices (O’Donovan et al., 2015). |

| Key features | Applications |

|---|---|

| Mass customization |

|

| Material efficiency |

|

| Manufacturing decentralization |

|

| Inventory and logistics costs reduction |

|

| Features | Applications |

|---|---|

| Virtual representation |

|

| Real time visibility |

|

| Continuous monitoring |

|

| Immersive training simulations |

|

| Remote collaboration and stakeholder engagement |

|

| Workstream | Key Action Area | Industry 4.0 Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Innovation | Resource Market & Availability Analysis | AI, Big Data, Blockchain, Cloud |

| Increase Sustainable Lipid Supply | AI, ML, Blockchain, IoT | |

| Boost Biomass Production & Waste Collection | IoT, AI, Autonomous Robots | |

| Improve Feedstock Supply Logistics | AI, IoT, Blockchain, Edge Computing | |

| Improve Feedstock Handling Reliability | AI, Digital Twins, Robotics, Edge Computing | |

| Enhance Sustainability of Biomass Supply | AI, Blockchain, IoT | |

| Conversion Technology | Decarbonize and Scale Fermentation-Based Fuels | AI, ML, IoT, Blockchain, Edge Computing |

| Enhance ASTM Pathways | Digital Twins, AI, Blockchain, 3D Printing | |

| Develop Bio-intermediates | AI, Cyber-physical Systems, 3D Printing | |

| Reduce Risk & Scale-Up | AI, Digital Twins, Blockchain | |

| Develop Innovative Pathways | AI, IoT, Automation | |

| Building Supply Chains | Establish Regional Coalitions | Blockchain, Cloud, Smart Contracts |

| Model SAF Supply Chains | AI, Big Data, IoT, Edge Computing | |

| Demonstrate Regional Supply Chains | AI, Digital Twins, 3D Printing | |

| Develop Production Infrastructure | AI, Robotics, Automation, Blockchain | |

| Policy and Valuation | Improve Environmental Data & Models | AI, Big Data, Blockchain, Cloud |

| Techno-economic Feasibility Analysis | AI, Digital Twins, Edge Computing | |

| Contribute to SAF Policy Development | AI, Blockchain, Cloud | |

| Enabling End Use | Support Evaluation & Testing | AI, Digital Twins, Blockchain, Automation |

| Adopt High-percentage SAF Blends | AI, Cyber-physical Systems, Sensors | |

| Explore Synthetic Jet Fuels | AI, 3D Printing, Automation | |

| Adapt Infrastructure | IoT, Blockchain, AI | |

| Communicating Progress | Engage Stakeholders | AI, Blockchain, Cloud |

| Assess Benefits & Influence | AI, Digital Twins, Cloud | |

| Track SAF Grand Challenge | IoT, Blockchain, AI, Cloud | |

| Share Positive Impacts | AI, AR/VR, Blockchain, Sentiment Analysis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).