Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Solution Preparation

2.2. Visual Tests

2.3. Density and Sound Velocity

2.4. Tensiometry

2.5. Dynamic Light Scattering

2.6. Viscosimetry

2.7. Rheometry

- Simple shear: Shear viscosity measurements were performed in a speed range from 1 to 500 s-1, obtaining 5 points per logarithmic decade.

- To determine the linear viscoelastic zone (LVZ), the elastic and viscous moduli were obtained from 0.1 to 100% of relative deformation at a constant frequency of 10 rad/s, obtaining 10 points per logarithmic decade.

- Elastic and viscous moduli were obtained from a frequency of 0.1 to 100 rad/s at a constant strain within the LVZ. Dynamic viscosity was analyzed in conjunction with shear rate and viscosity determined in the viscometer.

- The elastic and viscous moduli were obtained as a function of temperature at a constant frequency of 10 rad/s and with the same percentage of deformation belonging to the LVZ.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Visual Tests

3.2. Density and Sound Velocity

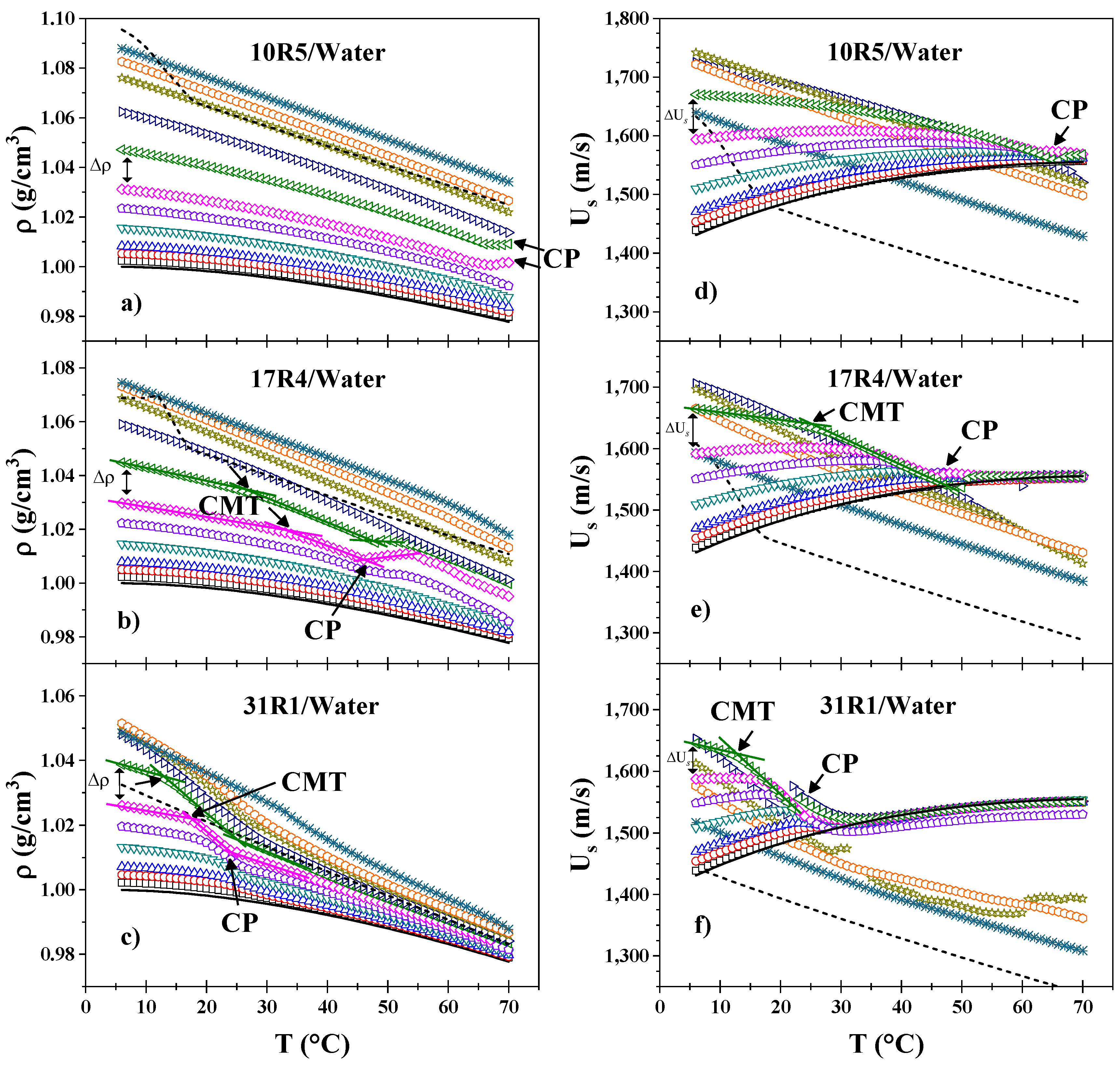

- In the 10R5/water system (Figure 2a), these decays are only observed when the derivative (not shown) is analyzed. Only a slight increase in density is visible at 65°C and above (at concentrations of 20 and 30 wt%), corresponding to phase separation, which was verified by direct observation. At these concentrations, the amount of copolymer is sufficient for the instrument to begin to detect homogeneity errors in the sample.

- In the 17R4/water system (Figure 2b), the density decays sharply at intermediate temperatures, around 20 and 40°C, exhibiting two distinct linear zones. Very similar to the 10R5 system, the 15, 20 and 30% concentrations experience a slight peak in density that rises and decays in the 45 and 50°C range due to phase separation.

- For the 31R1/water system (Figure 2c), the dehydration of the PPO blocks is more abrupt than for the other two systems, where again two linear zones can be delineated between 10 and 20°C. The phase separation of these systems was observed between 20 and 30°C, and above this temperature the density acquires an almost linear behavior, the slope of which increases with concentration.

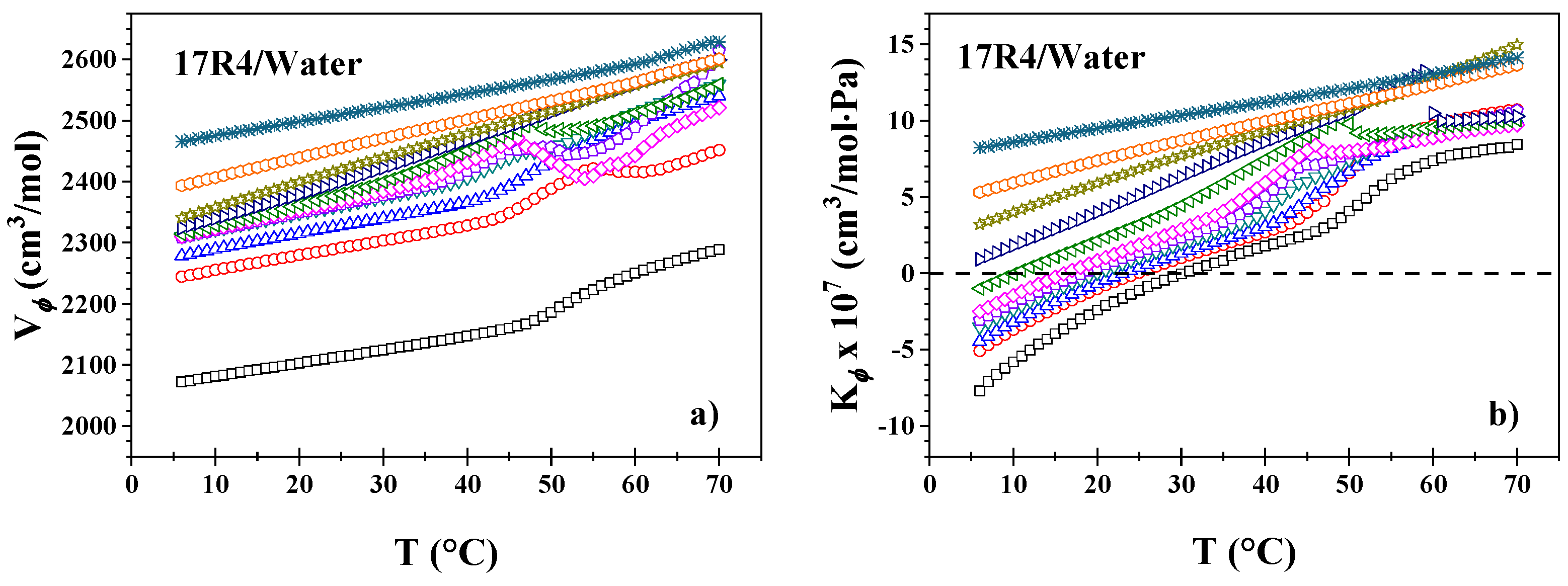

3.3. Molar Volume and Molar Adiabatic Compressibility

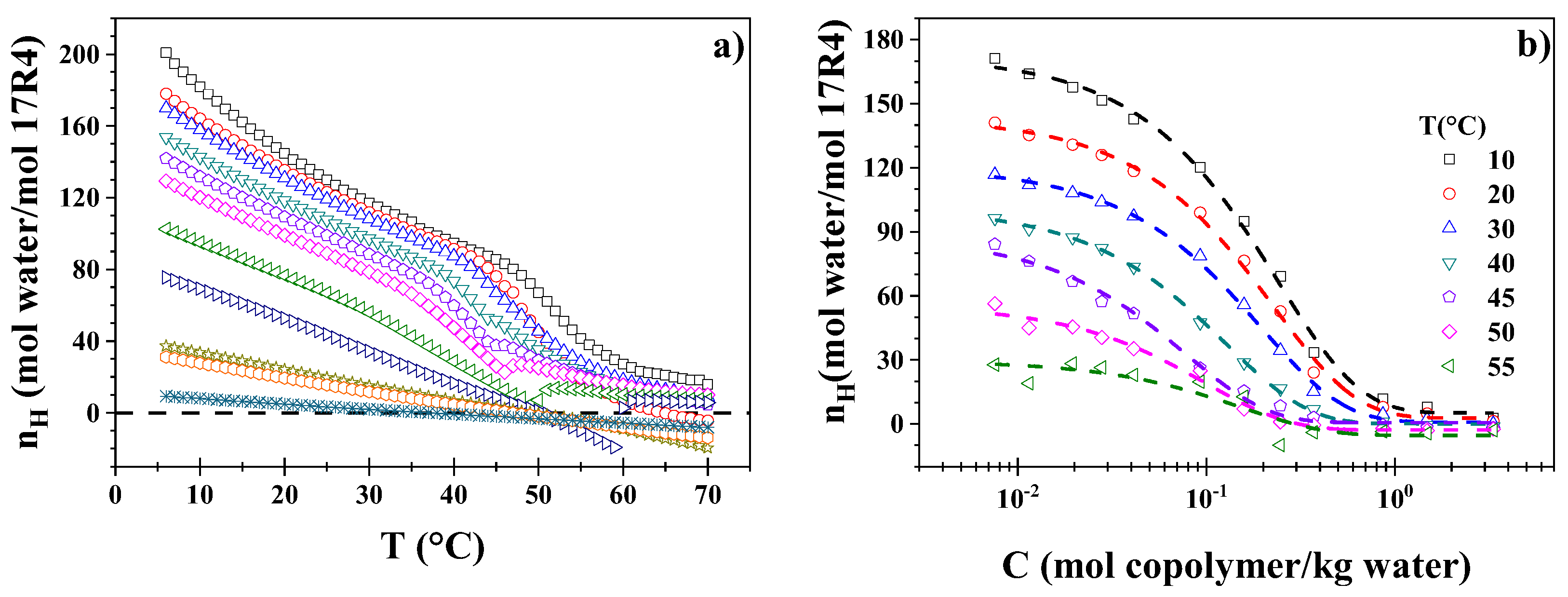

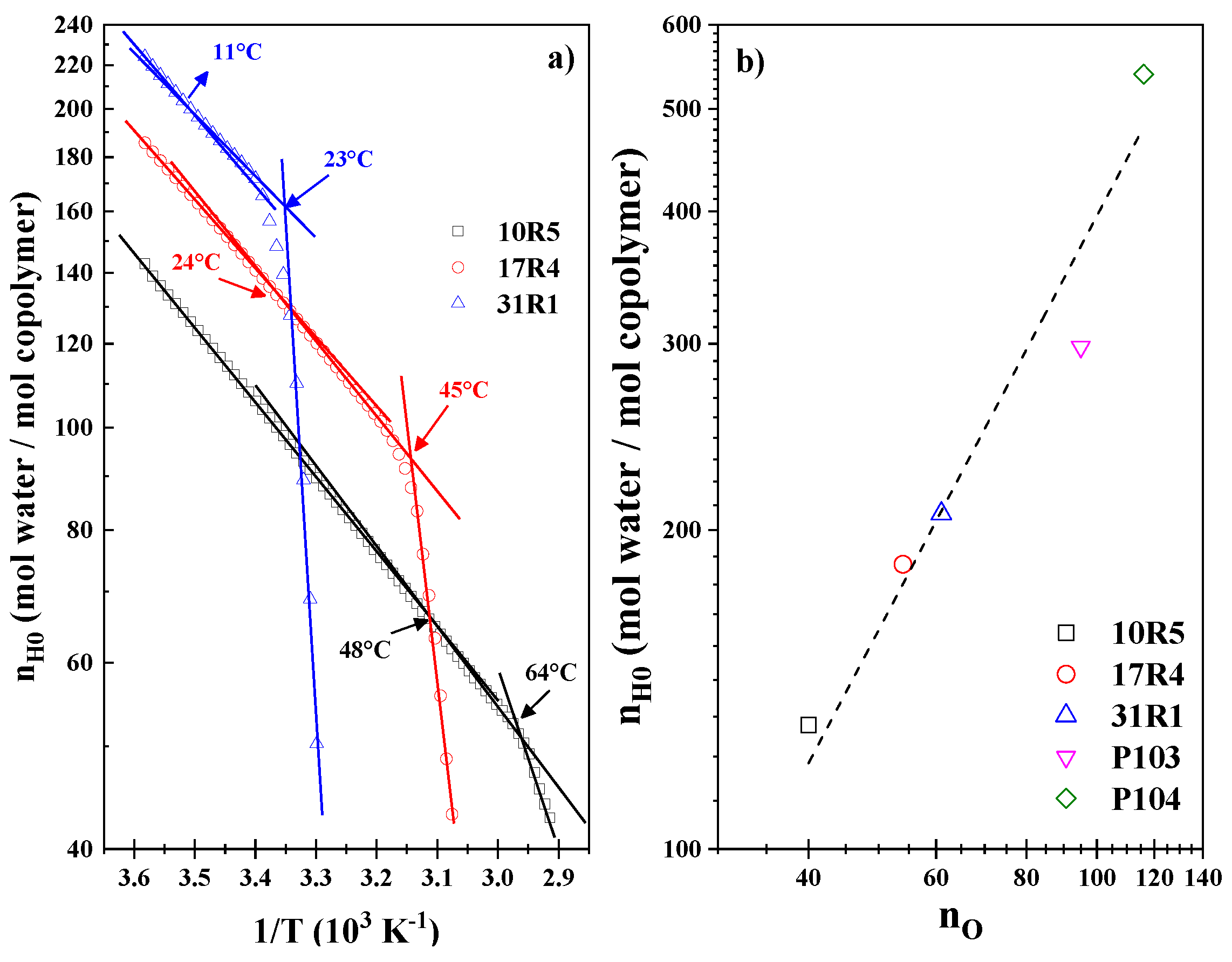

3.4. Hydration Number

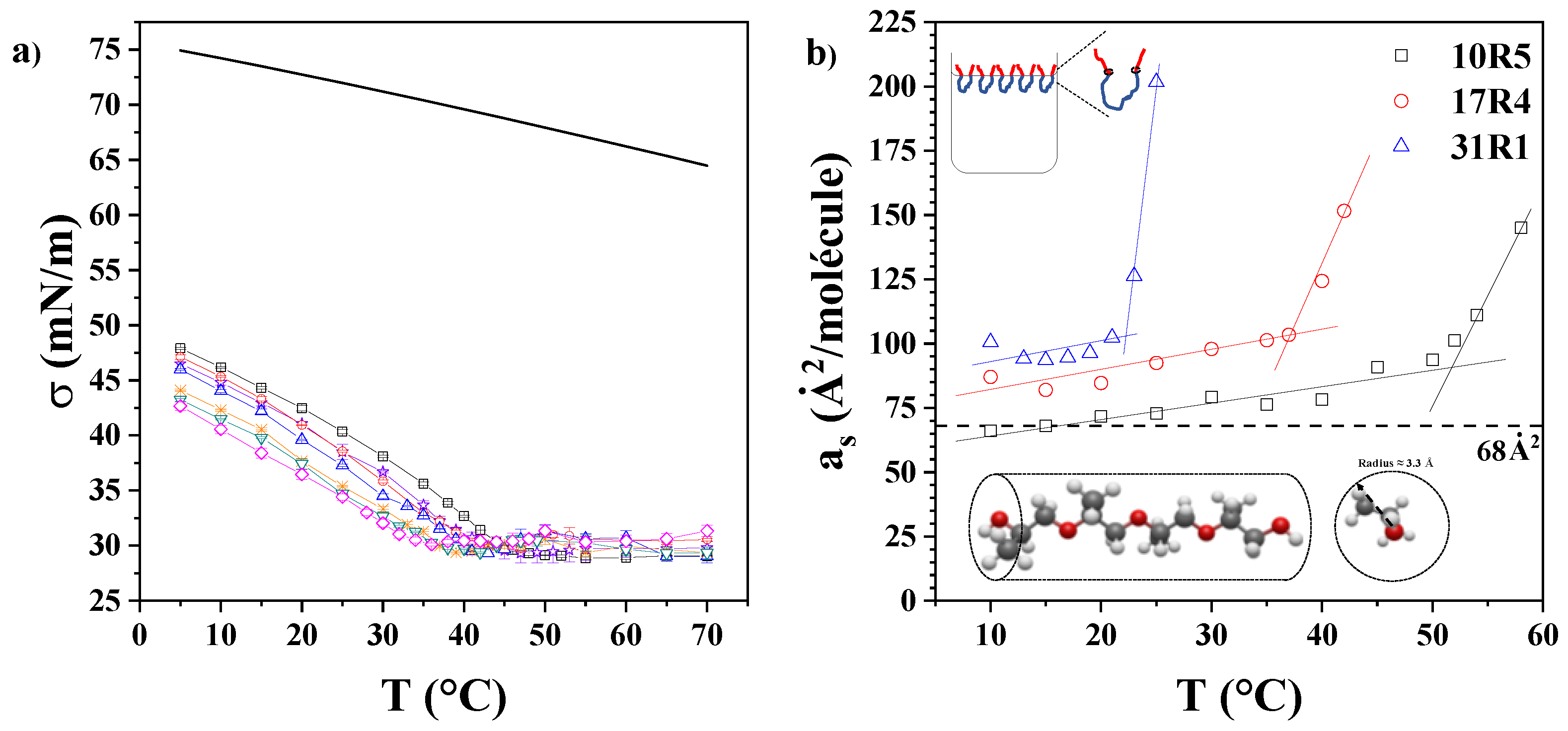

3.5. Surface Tension

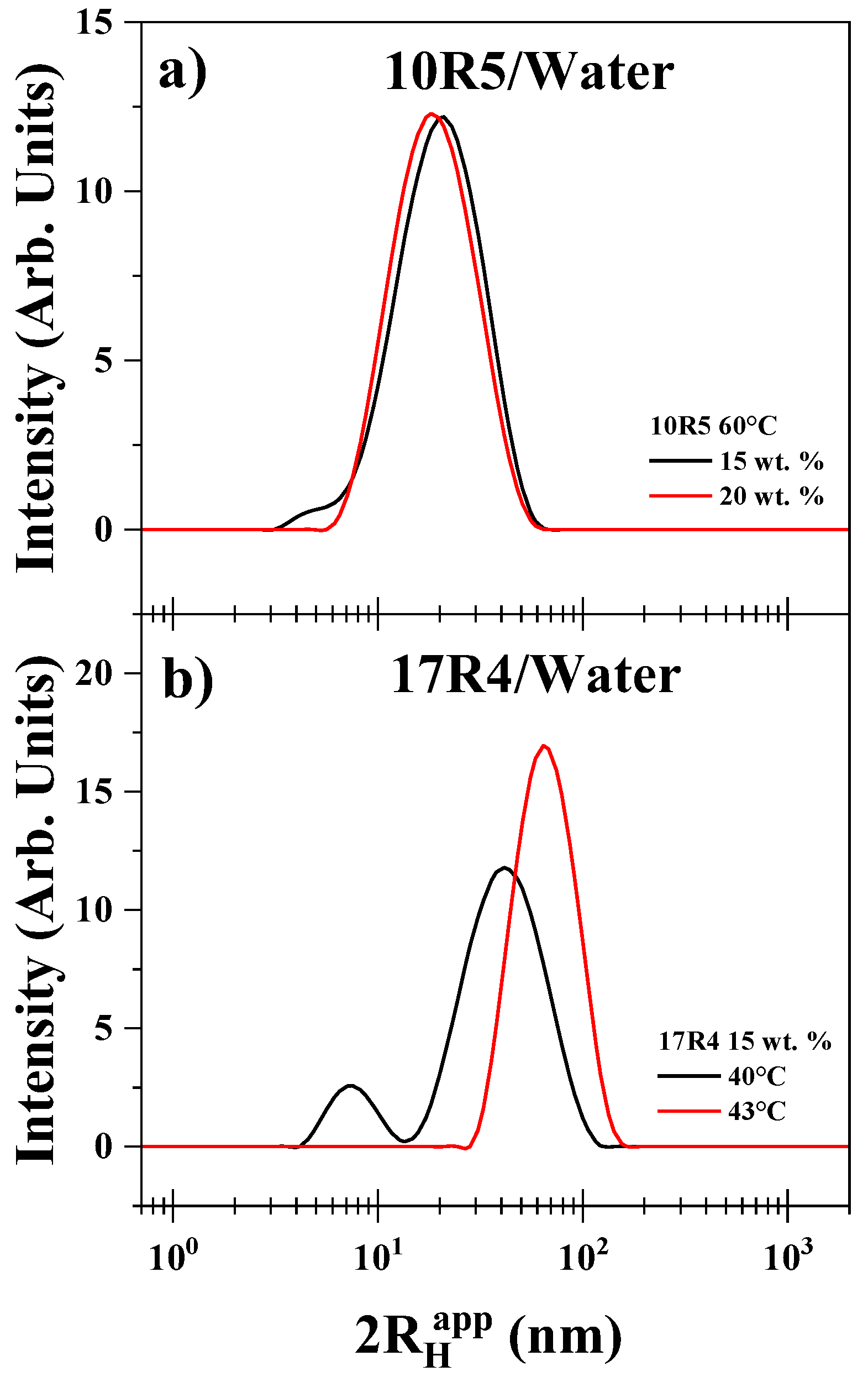

3.6. Dynamic Light Scattering

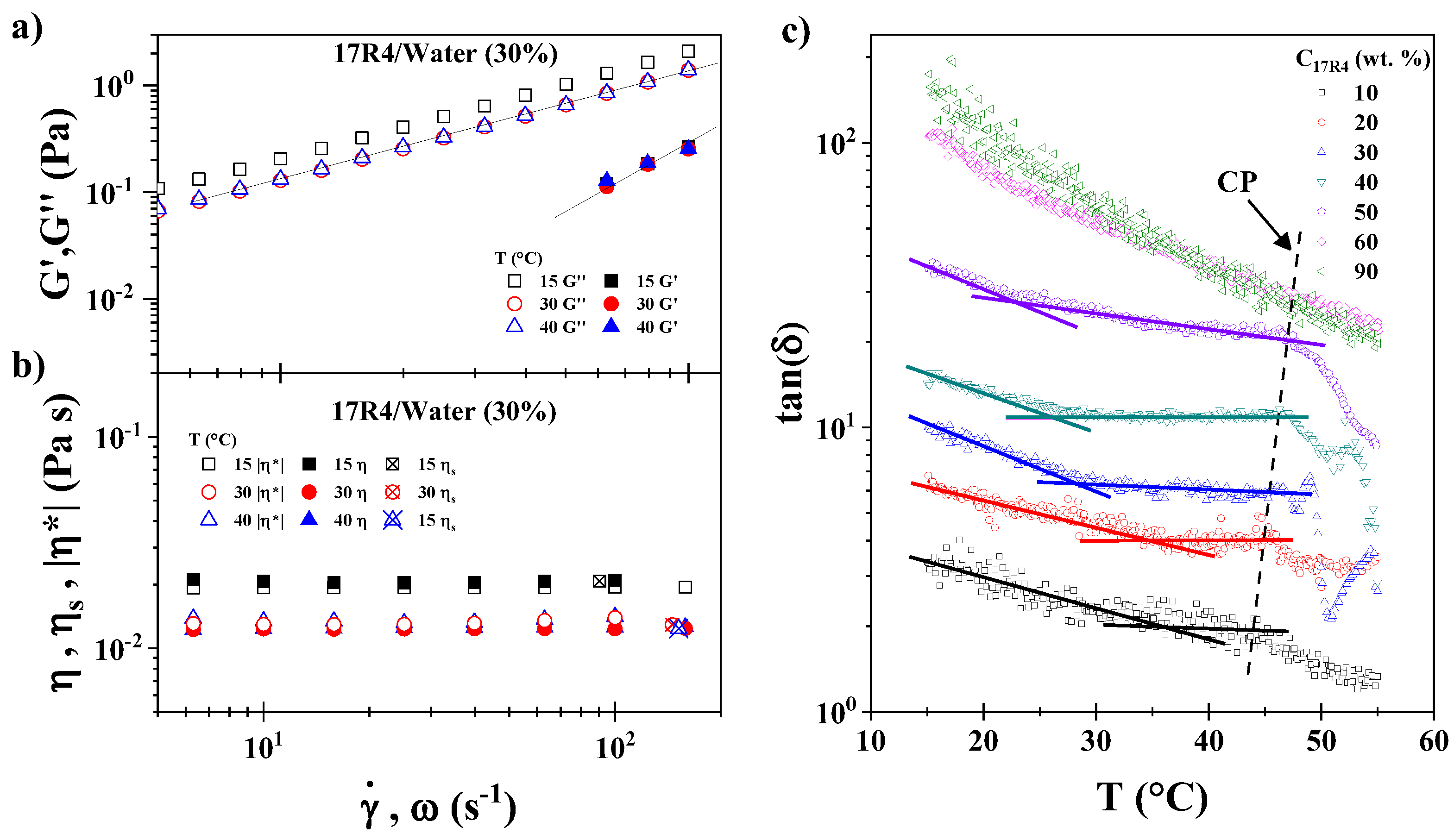

3.7. Rheometry

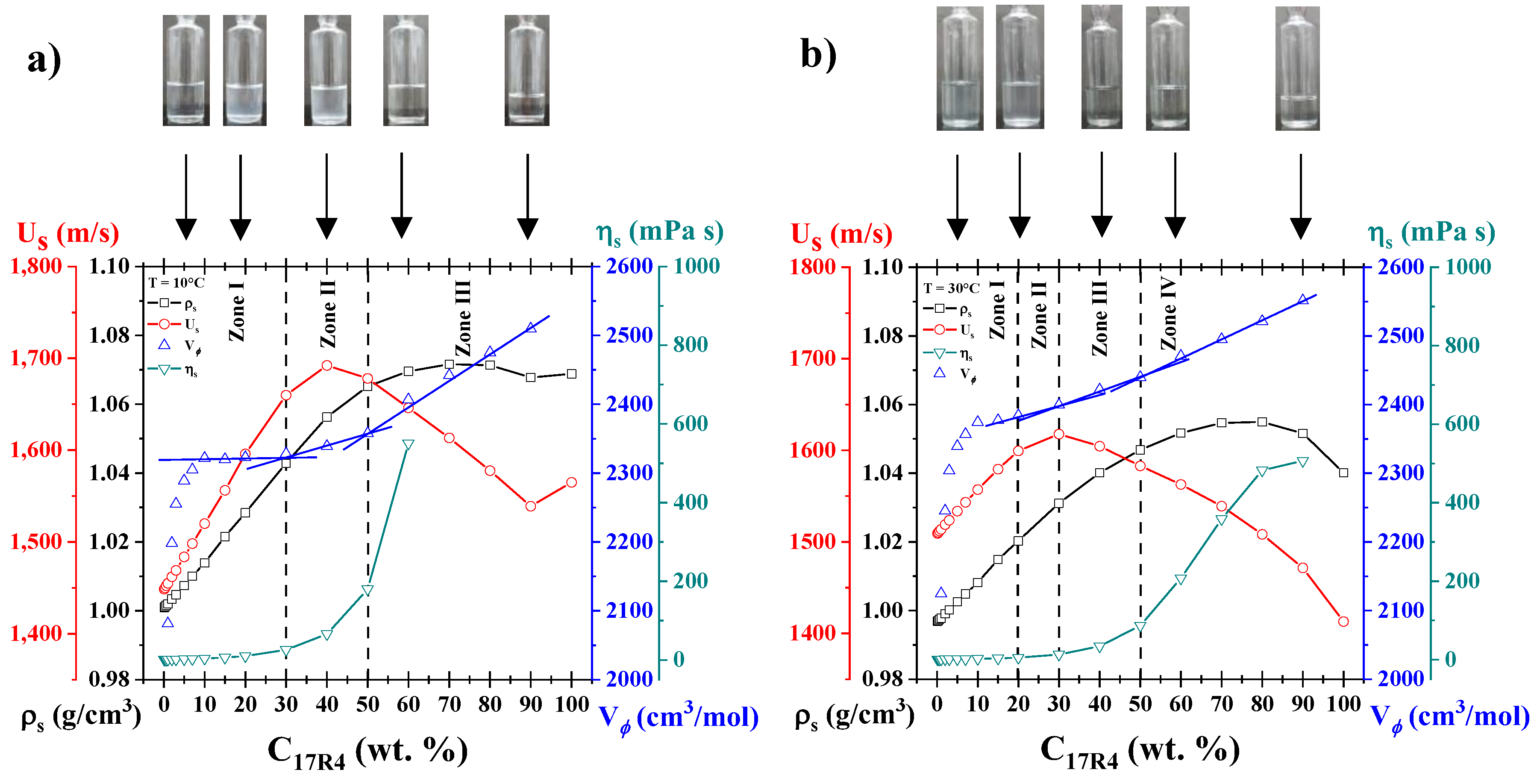

3.8. Analysis by Concentration

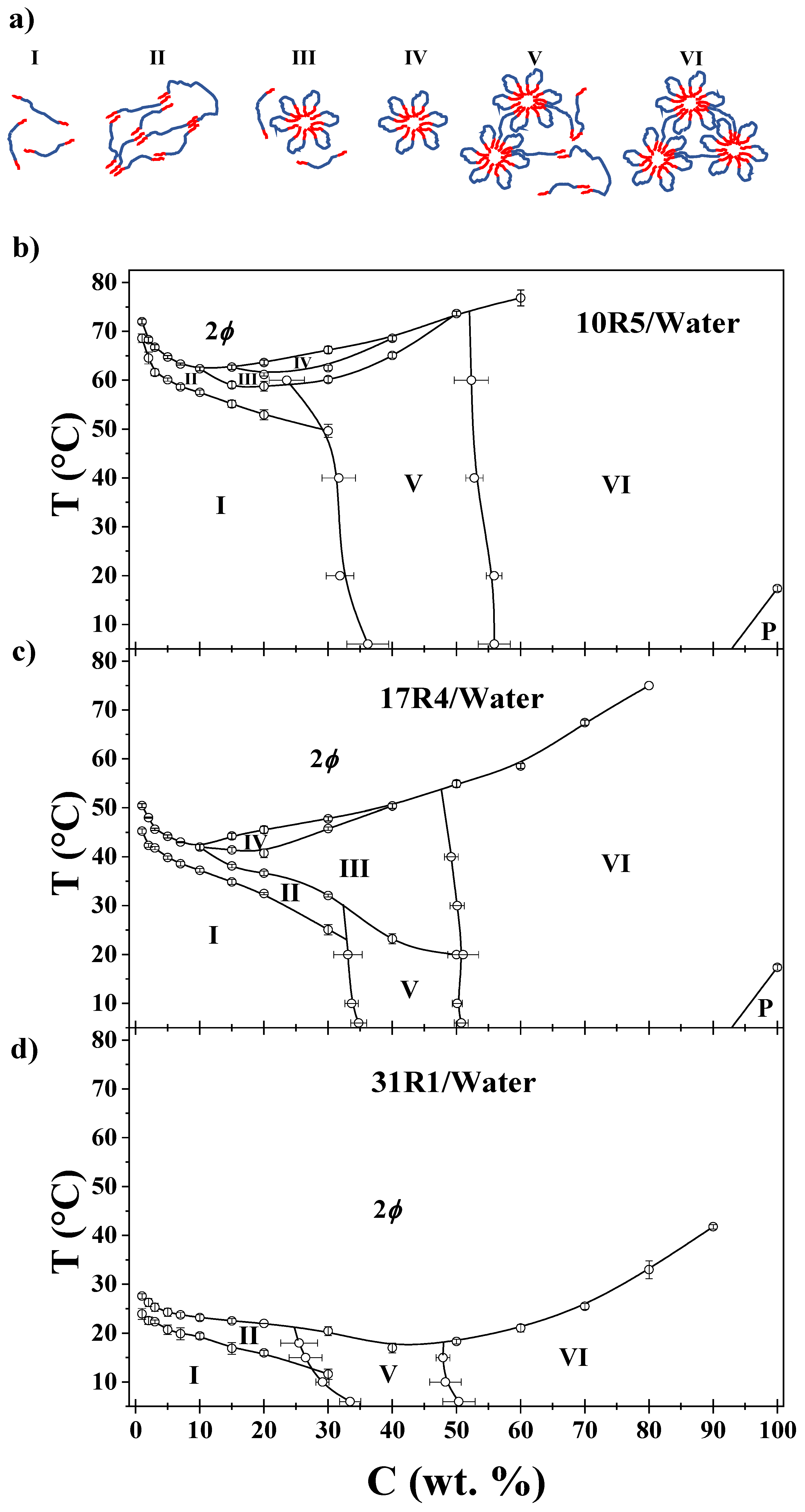

3.9. Phase diagrams

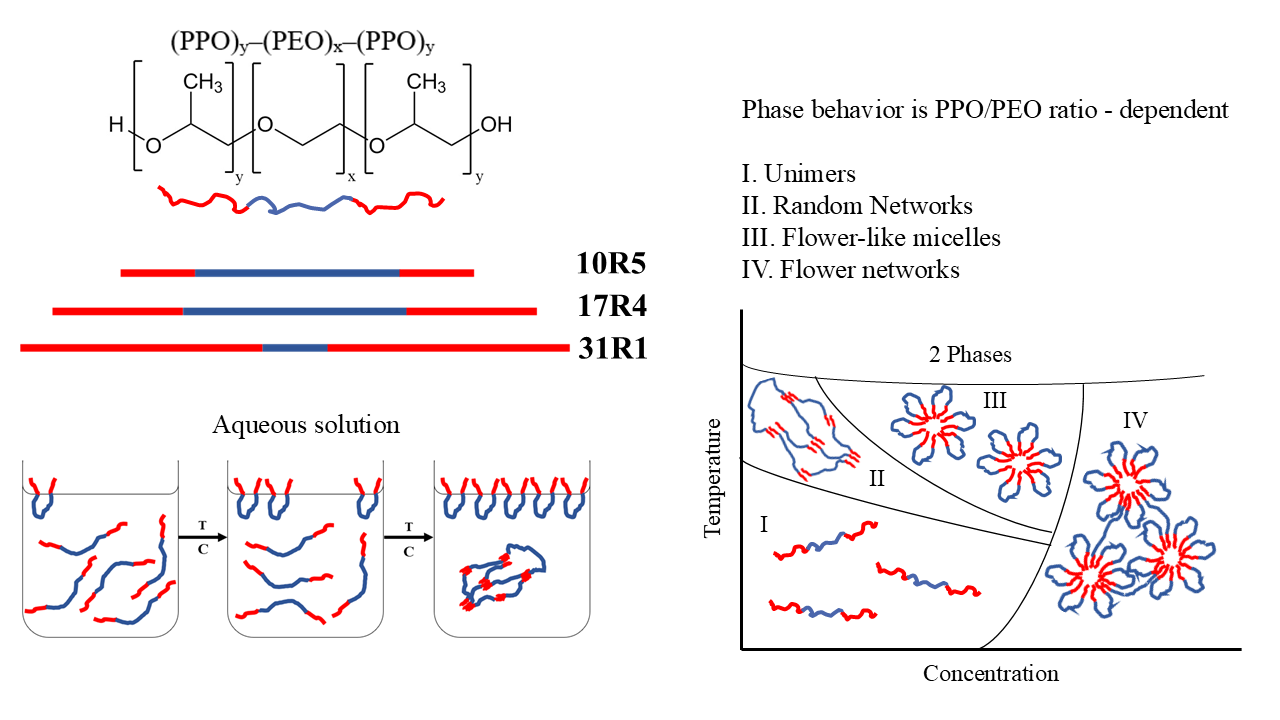

- I.

- Unimers: visually transparent with high polydispersity and monotonous physicochemical properties.

- II.

- Random networks: visually opaque with minor changes in viscosity, density, and sound velocity.

- III.

- Flower-like micelles and unimers: optically transparent with significant changes in viscosity.

- IV.

- Flower-like micelles: visually similar to zone III. Zones III and IV are distinguished by DLS size distributions.

- V.

- Micellar networks and unimers: Visually transparent and with abrupt changes in density, sound velocity, viscosity, and molar volume when analyzed by concentration.

- VI.

- Micellar networks: Visually similar to Zone V. Zone V and VI can be distinguished by the beginning and end of the transition development as shown in Figure 10.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kesisoglou, F.; Wu, Y. Understanding the effect of API properties on bioavailability through absorption modeling. AAPS J 2008, 10(4), 516–525. [CrossRef]

- Chavda, H. V.; Patel, C. N.; Anand, I. S. Biopharmaceutics classification system. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy 2010, 1(1), 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Malmsten, M. Surfactants and polymers in drug delivery. In Drugs and the pharmaceutical sciences, 1st ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, USA, 2002; Volume 122, pp. 1–49. ISBN: 9780824743758.

- Garg, S.; Peeters, M.; Mahajan, R. K.; Singla, P. Loading of hydrophobic drug silymarin in pluronic and reverse pluronic mixed micelles. J Drug Deliv Sci Tech, 2022, 75, p. 103699. [CrossRef]

- Raval, A.; Pillai, S. A.; Bahadur, A.; Bahadur, P. Systematic characterization of Pluronic® micelles and their application for solubilization and in vitro release of some hydrophobic anticancer drugs. J Mol Liq, 2017, 230, 473-481. [CrossRef]

- Schmolka, I. R. A Review of Block Polymer Surfactants. J Am Oil Chem Soc 1977, 54(3), 110–116. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Khan, A. Phase Behavior of Poly(ethylene oxide)-Poly(propylene oxide)-Poly (ethylene oxide) Triblock Copolymers in Water. Macromolecules 1995, 28(11), 3807–3812. [CrossRef]

- Almgren, M.; Brown, W.; Hvidt S. Self-aggregation and phase behavior of poly(ethylene oxide )-poly(propylene oxide)-poly(ethylene oxide) block copolymers in aqueous solution. Colloid Polym Sci 1995, 273, 2–15. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Jin, Q.; Li, B.; Ding, D.; Shi, A. C. Phase diagram of poly(ethylene oxide) and poly(propylene oxide) triblock copolymers in aqueous solutions. Macromolecules 2006, 39(17), 5891–5896. [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, P.; Holzwarth, J. F.; Hatton, T. A. Micellization of Poly(ethylene oxide)-Poly(propylene oxide)-Poly(ethylene oxide) Triblock Copolymers in Aqueous Solutions: Thermodynamics of Copolymer Association. Macromolecules 1994, 27(9), 2414–2425. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q.; Li, L.; Jiang S. Effects of a PPO-PEO-PPO triblock copolymer on micellization and gelation of a PEO-PPO-PEO triblock copolymer in aqueous solution. Langmuir 2005, 21(20), 9068–9075. [CrossRef]

- Linse, P. Micellization of Poly(ethylene oxide)-Poly(propylene oxide) Block Copolymers in Aqueous Solution. Macromolecules 1993, 26(17), 4437–4449, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Tsui, H. W.; Wang, J. H.; Hsu, Y. H.; Chen, L. J. Study of heat of micellization and phase separation for Pluronic aqueous solutions by using a high sensitivity differential scanning calorimetry. Colloid Polym Sci 2010, 288(18), 1687–1696. [CrossRef]

- Naharros-Molinero, A.; Caballo-González, M. Á.; de la Mata, F. J.; García-Gallego, S. Direct and Reverse Pluronic Micelles: Design and Characterization of Promising Drug Delivery Nanosystems. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14(12), 2628. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kotaka, T.; Inagaki, H. Thermodynamic and Conformational Properties of Styrene-Methyl Methacrylate Block Copolymers in Dilute Solution. V. Light-Scattering Analysis of Conformational Anomalies in p-Xylene Solution. Polym J 1972, 3(3), 338–349. [CrossRef]

- ten Brinke, G.; Hadziioannou, G. Topological Constraints and Their Influence on the Properties of Synthetic Macromolecular Systems. 2. Micelle Formation of Triblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 1987, 20(3), 486–489. [CrossRef]

- Balsara, N. P.; Tirrell, M.; Lodge, T. P. Micelle Formation of BAB Triblock Copolymers in Solvents That Preferentially Dissolve the A Block. Macromolecules 1991, 24(8), 1975–1986. [CrossRef]

- Naskar, B.; Ghosh, S.; Moulik, S. P. Solution Behavior of Normal and Reverse Triblock Copolymers (Pluronic L44 and 10R5) Individually and in Binary Mixture. Langmuir 2012, 28(18), 7134–7146. [CrossRef]

- Larrañeta, E.; Isasi, J. R. Phase Behavior of Reverse Poloxamers and Poloxamines in Water. Langmuir 2012, 29(4), 1045–1053. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, G.; Vicente, F. A.; Schaeffer, N.; Cardoso, I. S.; Ventura, S. P.; Jorge, M.; Coutinho, J. A. Rationalizing the Phase Behavior of Triblock Copolymers through Experiments and Molecular Simulations. J Phys Chem C 2019, 123(34), 21224–21236. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chu, B. Phase Behavior and Association Properties of Poly(oxypropylene)-Poly(oxyethylene)-Poly(oxypropylene) Triblock Copolymer in Aqueous Solution. Macromolecules 1994, 27(8), 2025. [CrossRef]

- Huff, A.; Patton, K.; Odhner, H.; Jacobs, D. T.; Clover, B. C.; Greer, S. C. Micellization and Phase Separation for Triblock Copolymer 17R4 in H2O and in D2O. Langmuir 2011, 27(5), 1707–1712. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhry, B. Z.; Snowden, M. J.; Leharne, S. A. A scanning calorimetric investigation of phase transitions in a PPO-PEO-PPO block copolymer. Eur Polym J 1999, 35(2), 273–278. [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, G.; Paduano, L.; Khan, A. Temperature and concentration effects on supramolecular aggregation and phase behavior for poly(propylene oxide)-b-poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(propylene oxide) copolymers of different composition in aqueous mixtures. J Colloid Interface Sci 2004, 279(2), 379–390. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, K.; Brown, W.; Jorgensen, E. Phase Behavior of Poly(propylene oxide) - Poly(ethylene oxide) - Poly(propylene oxide) Triblock Copolymer Melt and Aqueous Solutions. Macromolecules 1994, 27(20), 5654–5666. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Bao, H.; Li, L. Role of PPO-PEO-PPO triblock copolymers in phase transitions of a PEO-PPO-PEO triblock copolymer in aqueous solution. Eur Polym J 2015, 71(2), 423–439. [CrossRef]

- White, J. M.; Calabrese, M. A. Impact of small molecule and reverse poloxamer addition on the micellization and gelation mechanisms of poloxamer hydrogels. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2022, 638, 128246. [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, P.; Olsson, U.; Lindman, B. Phase Behavior of Amphiphilic Block Copolymers in Water-Oil Mixtures: The Pluronic 25R4-Water-p-Xylene System. J Phys Chem 1996, 100(1), 280–288. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D. ; Vaswani, P.; Sengupta, S.; Ray, D.; Bhatia, D.; Choudhury, S. D.; Aswalm V. K.; Kuperkar, K.; Bahadur, P. Thermoresponsive phase behavior and nanoscale self-assembly generation in normal and reverse Pluronics®. Colloid Polym Sci 2022, 301, 75–92. [CrossRef]

- White, J. M.; Garza, A.; Griebler, J. J.; Bates, F. S.; Calabrese, M. A. Engineering the Structure and Rheological Properties of P407 Hydrogels via Reverse Poloxamer Addition. Langmuir 2023, 39(14), 5084–5094. [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh S.; Feng, Z.; Pettersson, T.; Hakkarainen, M. A proof-of-concept for folate-conjugated and quercetin-anchored pluronic mixed micelles as molecularly modulated polymeric carriers for doxorubicin. Polymer (Guildf) 2015, 74, 193–204. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kang, T. S.; Mahajan, R. K. Complexation of triblock reverse copolymer 10R5 with surface active ionic liquids in aqueous medium: A physico-chemical study. RSC Adv 2015, 5(21), 16349–16360. [CrossRef]

- Phani Kumar, B. V. N.; Reddy, R. R.; Pan, A.; Aswal, V. K.; Tsuchiya, K.; Prameela, G. K. S.; Abe, M.; Mandal, A. B.; Moulik, S. P. Physicochemical Understanding of Self-Aggregation and Microstructure of a Surface-Active Ionic Liquid [C4mim] [C8OSO3] Mixed with a Reverse Pluronic 10R5 (PO8EO22PO8). ACS Omega 2018, 3(5), 5155–5164. [CrossRef]

- Saoudi, O.; Lasrem, A.; Ghaouar, N. Studies of the behavior of reverse nonionic surfactant Pluronic 31R1 in aqueous and Propylammonium acetate (PAAc) ionic liquid solutions. J Polym Res 2020, 27(12), 357. [CrossRef]

- Heater, K. J.; Tomasko, D. L. Processing of epoxy resins using carbon dioxide as an antisolvent. J Supercrit Fluids 1998, 14(1), 55–65. [CrossRef]

- Lin, B. J.; Zhu, H. T.; Tieu, A. K.; Kosasih, B. Y.; Triani, G. The effect of molecular structure on the adsorption of PPO-PEO-PPO triblock copolymers on solid surfaces. MSF 2014, 773–774, 670–677. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Murali, R.; Murthy, C. N. Clouding and aggregation behavior of PPO-PEO-PPO Triblock Copolymer (Pluronic®25R4) in surfactant additives environment. TSD 2012, 49(2), 136–144. [CrossRef]

- Franks, F. F.; Quickenden, M. J.; Ravenhill, J. R.; Smith, H. T. Volumetric behavior of dilute aqueous solutions of sodium alkyl sulfates. J Phys Chem 1967, 72(7), 2668–2669. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Ochoa, E. B.; Bravo-Anaya, L. M.; Vaca-López, R.; Landázuri-Gómez, G.; Rosales-Rivera, L. C.; Diaz-Vidal, T.; Carvajal, F., Macías-Balleza, E. R.; Rharbi, Y.; Soltero-Martínez, J. F. A. Structural Behavior of Amphiphilic Triblock Copolymer P104/Water System. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15(11), 2551. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P. Colloid and Interface Science, 1st ed; PHI Learning Private Limited, New Dehli, India, 2009. ISBN: 9788120338579.

- Hassan, P. A.; Rana, S.; Verma, G. Making sense of Brownian motion: Colloid characterization by dynamic light scattering. Langmuir 2015, 31(1), 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R. Dynamic Light Scattering for Protein Characterization. EAC 2010. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Perez-Sanchez, G.; Jorge, M.; Ray, D.; Aswal, V. K.; Kuperkar, K.; Coutinho, J. A. P.; Bahadur, P. Rationalizing the Design of Pluronics-Surfactant Mixed Micelles through Molecular Simulations and Experiments. Langmuir 2022, 39(7), 2692–2709. [CrossRef]

- Causse, J.; Lagerge, S.; de Ménorval, L. C.; Faure, S.; Fournel, B. Turbidity and 1H NMR analysis of the solubilization of tributylphosphate in aqueous solutions of an amphiphilic triblock copolymer (L64 pluronic). Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2005, 252(1), 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Ramírez, J. G.; Fernández, V. V. A.; Macías, E. R.; Rharbi, Y.; Taboada, P.; Gámez-Corrales, R.; Puig J. E.; Soltero, J. F. A. Phase behavior of the Pluronic P103/water system in the dilute and semi-dilute regimes. J Colloid Interface Sci 2009, 333(2), 655–662. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Patel, D.; Ray, D.; Kuperkar, K.; Aswal, V. K.; Bahadur, P. Single and mixed Pluronics® micelles with solubilized hydrophobic additives: Underscoring the aqueous solution demeanor and micellar transition. J Mol Liq 2021, 343, 117625. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, G.; Scherf, G.; Glatter, O. Applications of Densiometry, Ultrasonic Speed Measurements, and Ultralow ShearViscosimetry to Aqueous Fluids. J Phys Chem B 2000, 104(15), 3463–3470. [CrossRef]

- Maccarini, M.; Briganti, G. Density Measurements on C12Ej Nonionic Micellar Solutions as a Function of the Head Group Degree of Polymerization (j = 5-8). J Phys Chem A 2000, 104(48), 11451–11458. [CrossRef]

- Wen, X. G.; Verrall, R. E. Temperature Study of Sound Velocity and Volume-Related Specific Thermodynamic Properties of Aqueous Solutions of Poly(ethylene oxide)-Poly(propylene oxide)-Poly (ethylene oxide) Triblock Copolymers. J Colloid Interface Sci 1997, 196(2), 215–223. [CrossRef]

- Meilleur, L.; Hardy, A.; Quirion, F. Probing the Structure of Pluronic PEO-PPO-PEO Block Copolymer Solutions with Their Apparent Volume and Heat Capacity. Langmuir 1996, 12(20), 4697–4703. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J. K.; Parsonage, J.; Chowdhry, B.; Leharne, S.; Mitchell, J.; Beezer, A.; Löhner, K.; Laggner, P. Scanning Densitometric and Calorimetric Studies of Poly(ethylene oxide) / Poly(propylene oxide) / Poly(ethylene oxide)Triblock Copolymers (Poloxamers) in Dilute Aqueous Solution. J Phys Chem 1993, 97(15), 3904–3909. [CrossRef]

- Eagland, D.; Crowther, N. J. Hydrophobic Interactions in Dilute Solutions of Poly(vinyl alcohol). Faraday Symp Chem Soc 1982, 17, 141–160. [CrossRef]

- Aeberhardt, K.; de Saint Laumer, J. Y.; Bouquerand, P. E.; Normand, V. Ultrasonic wave spectroscopy study of sugar oligomers and polysaccharides in aqueous solutions: The hydration length concept. Int J Biol Macromol 2005, 36(5), 275–282. [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, P.; Athanassiou, V.; Fukuda, S.; Hatton, T. A. Surface Activity of Poly(ethylene oxide)-block-Poly(propylene oxide)-block-Poly(ethylene oxide) Copolymers. Langmuir 1994, 10(8), 2604–2612. [CrossRef]

- Wanka, G.; Hoffmann, H.; Ulbricht, W. The aggregation behavior of poly-(oxyethylene)-poly-(oxypropylene)- poly-(oxyethylene)-block-copolymers in aqueous solution. Colloid Polym Sci 1990, 268, 101–117. [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M. D.; Curtis D. E.; Lonie, D. C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G. R. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J Cheminform 2012, 4(17), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.; Verma, G.; Hassan, P. A.; Bhagwat, S. S. Equilibrium and Dynamic Surface Tension Behavior of Triblock Copolymer PEO-PPO-PEO in Aqueous Medium. J Dispers Sci Technol 2015, 36(6), 885–891. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K. N.; Luong, T. T.; Florence A. T.; Paris, J.; Vaution, C.; Seiller, M.; Puisieux, F. Surface Activity and Association of ABA Polyoxyethylene-Polyoxypropylene Block Copolymers in Aqueous Solution. J Colloid Interface Sci 1979, 68(2), 225–232. [CrossRef]

- Jebari, M. M.; Ghaouar, N.; Aschi, A.; Gharbi, A. Aggregation behaviour of Pluronic® L64 surfactant at various temperatures and concentrations examined by dynamic light scattering and viscosity measurements. Polym Int 2006, 55(2), 176–183. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Alexandridis, P.; Steytler, D. C.; Kositza, M. J.; Holzwarth, J. F. Small-angle neutron scattering investigation of the temperature-dependent aggregation behavior of the block copolymer Pluronic L64 in aqueous solution. Langmuir 2000, 16(23), 8555–8561. [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, L. Self-Assembly in Aqueous Solutions of Polyether-Modified Poly(acrylic acid). Langmuir 1998, 14(20), 5806–5812. [CrossRef]

- Glatter, O.; Scherf, G.; Schillén, K.; Brown, W. Characterization of a Polyethylene oxide)-Poly(propylene oxide) Triblock Copolymer (EO27-PO39-EO27) in Aqueous Solution. Macromolecules 1994, vol. 27(21), 6046–6054. [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, A.; Czapkiewicz, J.; del Castillo, J. L.; Rodríguez, J. R. Micellar properties of long-chain alkyldimethylbenzylammonium chlorides in aqueous solutions. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2001, 193(1-3), 129–137. [CrossRef]

| Structure | Characteristics | System analyzed |

|---|---|---|

| Random networks |

|

10R5, 17R4, 25R8 |

| Flower-like micelles |

|

|

| 17R4 | ||

| Micellar networks |

|

10R5, 25R4, 25R8 |

| Lamellar Phase |

|

25R4, 25R8 |

| System | Region | exp (α) | ΔEDH (kJ/mol) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10R5/water | I | 0.406 ± 0.008 | 13.6 ± 0.02 | 0.9999 |

| II | 0.423 ± 0.031 | 13.47 ± 0.08 | 0.9996 | |

| III | 5.075 x 10-4 | 32.36 ± 0.95 | 0.9965 | |

| 17R4/water | I | 0.833 ± 0.014 | 12.55 ± 0.03 | 0.9999 |

| II | 0.610 ± 0.014 | 13.31 ± 0.04 | 0.9999 | |

| III | 2.359 x 10-17 | 113.64 ± 0.84 | 0.9988 | |

| 31R1/water | I | 1.027 ± 0.045 | 12.49 ± 0.12 | 0.9997 |

| II | 1.518 ± 0.027 | 11.57 ± 0.06 | 0.9997 | |

| III | 1.137 x 10-67 | 398.15 ± 50.9 | 0.9683 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).