Introduction

The cerebellum is a critical structure in the human brain, significantly impacting physical movements, including eye coordination, motor learning, and complex tasks like driving or throwing a ball. It contributes to balance maintenance, motor coordination, visual tracking, and even cognitive processes such as language processing and mood regulation [

1]. This versatile role highlights the cerebellum importance not only in basic physical activities but also in higher-level functions, which has proven to be effective for modeling in AI systems.

With advancements in computational neuroscience, various models have been developed to work with cerebellar functions. These models range from traditional mathematical representations, such as the Hodgkin-Huxley equations, to some artificial neural networks (ANNs). The cerebellum ability to predict, adapt, and correct errors in real-time makes it an ideal inspiration for creating adaptive AI systems that can efficiently learn and operate in dynamic environments.

This review aims to explore the diverse computational models of the cerebellum, beginning with its overall architecture, then a focus on the Purkinje cell (PC) —the most important cell within this structure— and finally the other cerebellar cells. By analyzing their roles in motor control, error correction, and synaptic dynamics, this work will provide a comprehensive understanding of cerebellar functions. By evaluating both biological models and AI neural networks inspired by the cerebellum, this review will identify potential applications and limitations of these architectures.

Cerebellum Architecture

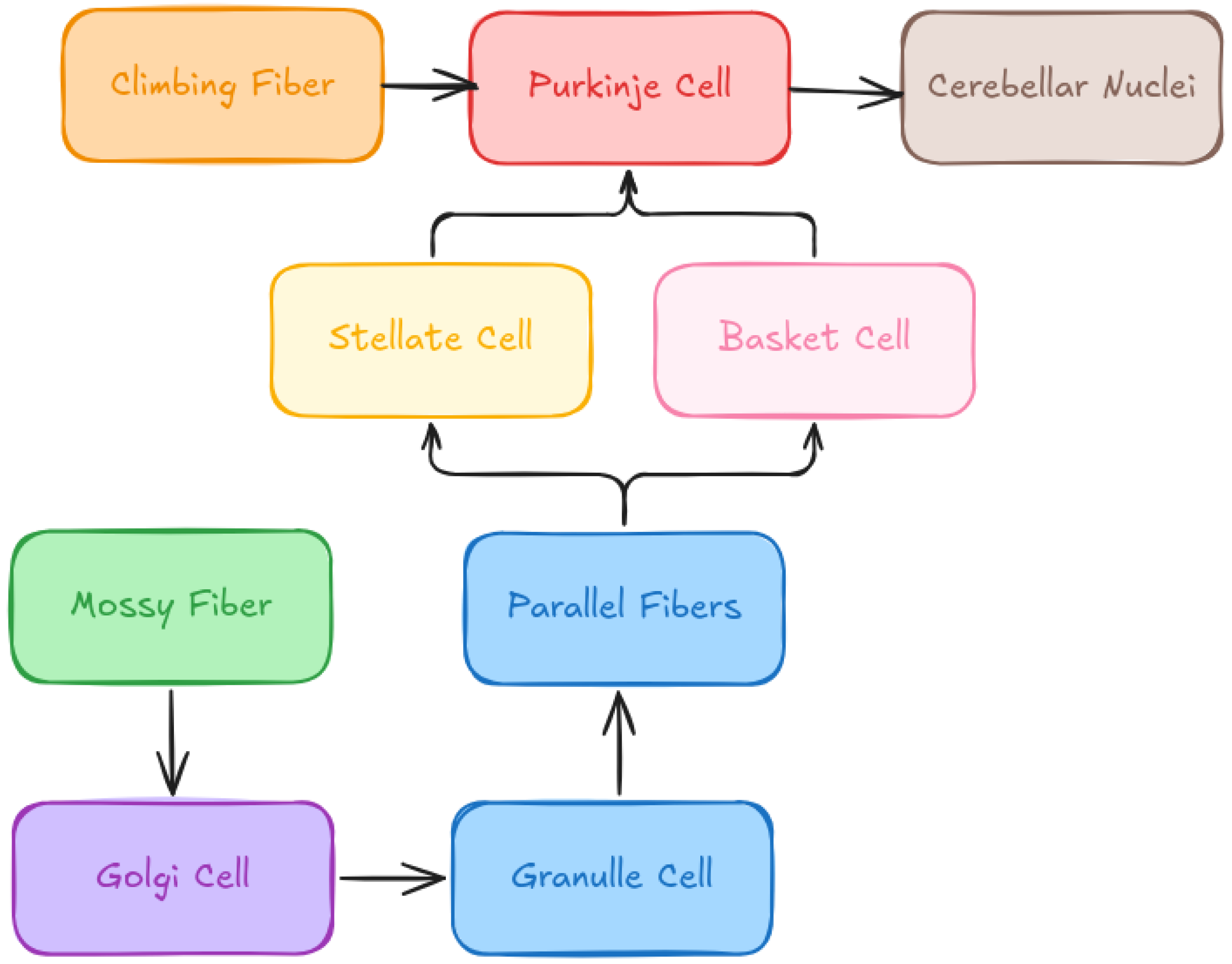

As shown in

Figure 1, the cerebellum exhibits a well-organized and layered cytoarchitecture. Various facets of the cerebellum architecture can be highlighted, along with its capacity for prediction and motor control, emphasizing its complexity and versatility. The cerebellum acts as a predictive feed-forward model, using Kalman filters to perform essential calculations for both motor control and cognitive functions [

3]. The ability to learn in real time through synaptic plasticity, as demonstrated in a model that uses mossy fibers and PCs to adjust synapses and accurately predict the position of moving targets, is fundamental [

4]. The synchronization and temporal coding in motor responses are generated intrinsically in the cerebellar circuits without relying on conduction delays, suggesting a new perspective on motor processing [

5]. Additionally, ANNs inspired by the structure of the cerebellum can replicate biomechanical functions of the extraocular muscles, demonstrating precise eye movements [

6]. It is also proposed that the cerebellum decodes input signals into group codes for more efficient processing, which contradicts the traditional idea of synaptic adjustment based on input patterns [

7]. The machine learning capabilities of the cerebellum are demonstrated in tasks such as pattern recognition and robot balance, highlighting its potential in robotics and autonomous systems applications [

8]. The modular organization and synaptic plasticity of the cerebellum are crucial for its adaptability and neuronal processing, which is essential to the regulation of complex behaviors [

9]. Models of neural networks based on the cerebellum show how it can learn behaviors through spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) [

10]. Furthermore, a computational model based on error learning suggests that the cerebellum adjusts motor commands in response to errors indicated by climbing fibers [

11]. Recent studies have developed large-scale neuromorphic cerebellar models that improve biological accuracy and computational efficiency for real-time motor learning [

12], while others demonstrate the application of cerebellum-inspired spiking neural networks in adaptive robotic control, enabling robots to handle dynamic environments through error correction [

13]. Additionally, cerebellum-based spiking neural networks (SNN) have been applied in both pattern classification and robotic trajectory prediction, showcasing versatility, scalability, and potential applications in robotics and autonomous systems [

14]. Furthermore, internal models in the cerebellum allow for the management of a wide range of motor tasks and quick adaptation to new situations, highlighting the importance of prediction in the control of complex movements [

15]. Studies show how the structure and functions of the cerebellum can be applied in models of learning and motor control, with significant implications for robotics and other autonomous systems such as is demonstrated in the mentioned papers.

Purkinje Cell

The PC has a dense and long dendritic tree that is extensively penetrated by parallel fibers. This neuron is responsible for transmitting information out of the cerebellar cortex through action potentials propagated along its axon. When it receives voltage from a climbing fiber or its dendrites, the channels open to increase the potential difference, consequently generating a signal that propagates along the axon. If the input voltage is insufficient, the channels do not open.

Over the years, various computational models have been developed to better understand the functioning of the PC. These models vary in their focus, complexity, and objectives, but all contribute to the collective knowledge about this cell.

Models [

16] and [

17] stand out for their focus on the active membrane of the PC. Using the neuronal simulation program GENESIS and the Hines algorithm, both models are based on detailed anatomical reconstructions and Hodgkin-Huxley equations to describe the ionic conductance of the membrane. Model [

16] focuses on the cell response under different currents, showing how somatic and dendritic Ca2+ waves are generated. In contrast, model [

18] adds a layer of complexity by incorporating excitatory and inhibitory synapses, revealing how these synaptic interactions influence the somatic and dendritic activity of the cell.

The model described in [

18] also uses GENESIS to simulate the PC but differs from the previous models by including a detailed circuit for the soma, the main dendrite, and the dendritic branches. This approach allows for the study of synaptic activation by different types of cells, providing a comprehensive view of synaptic dynamics in the PC. Similarly, the model in [

19] employs Hodgkin-Huxley equations but focuses specifically on the response to parallel and climbing fiber synapses, highlighting the specific interactions that modulate neuronal activity.

In contrast, the model presented in [

20] uses a probabilistic approach, based on equations representing a probability density function. This model focuses on the variability and nonlinear interactions between populations of PCs, offering a different perspective from the more detailed and mechanistic models.

The model described in [

21] focuses on the decoding of parallel fiber synapses, showing how activation of these fibers can produce hyperpolarization in the PC. This study aims to establish a decoding ranking for input patterns, adding an information processing dimension to the understanding of the PC.

Finally, the study in [

22] compares biological models [

16,

17] with ANNs in recognizing parallel fiber patterns. The results indicate that ANNs can perform significantly better in terms of pattern recognition, suggesting that these models could be a powerful tool for studying synaptic dynamics in the PC.The mathematical model is accurate for predicting cases bounded by the same model conditions, something that does not occur in the ANN since it will depend on the training data.

In summary, models [

16,

17,

18], and [

19] use Hodgkin-Huxley equations and focus on ionic conductance and synaptic responses, providing a detailed view of the electrophysiological mechanisms of the PC. Model [

20] introduces a probabilistic perspective, while [

21] focuses on the decoding of input patterns. Model [

21] compares the performance of biological models [

16,

17] with an ANN, highlighting the potential of ANNs in neuroscientific research. These results highlight the limitations of trusting only one modeling approach, and point to the need for hybrid frameworks that combine the precision of biologically grounded models with the adaptability and scalability of ANNs. Such integration could improve our understanding of the complex neuronal dynamics and support more effective applications.

Cerebellar neurons

The cerebellum contains many different neurons, each with distinctive morphological and functional characteristics that contribute to the motor responses and learning.

Table 1 summarizes the major cerebellar neuron types to help the understanding of the functions per each neuron type.

The model proposed by Tadashi Yamazaki and Shigeru Tanaka simulates a recurrent inhibitory network in the cerebellum by random projection. This model represents the interactions between granule cells and Golgi cells, generating reproducible random sequences in multiple trials, providing an in-depth understanding of synaptic dynamics in the cerebellum [

23]. In the study by Leffler et al., a mathematical model was developed that provides a detailed representation of granule cell development in the mouse cerebellum, accurately fitting the experimental data and showing excellent agreement with the growth dynamics observed in the cerebellar layers [

24].

Kawato model provides a computational representation of motor learning in the cerebellum based on error feedback learning. This model suggests that climbing fibers reflect errors in motor commands, which contributes to long-term synaptic plasticity in PCs, thus facilitating precise motor coordination [

11]. Similarly, the model of Kakei et al. proposes that the cerebellum is able to predict the internal state of the cerebral cortex by combining recurrent neural networks and feedforward networks, which optimizes motor control by integrating both structures [

3].

Steuber and Jaeger presented a model that focuses on rebound responses in neurons of the cerebellar nucleus and their role in temporal coding and synchronization of neuronal firing. This mechanism allows the generation of reverberant loops and facilitates the storage of activity patterns in the cerebellum [

25]. On the other hand, Peddicord model describes a grid-like structure between the cerebellar cortex and spinal pathways, highlighting the inhibitory influence of PCs and the synaptic architecture involved [

26].

LFPsim, developed by Parasuram, is a powerful tool that enables the simulation and visualization of electrical potentials in neurons and neural networks. It provides a graphical interface that displays neuron morphology and voltage changes, facilitating detailed analysis of bioelectrical activity [

27]. Krichmar et al. further expanded on this by using a qualitative reasoning algorithm to simulate neural behavior in the cerebellar cortex, showcasing the model ability to execute complex tasks such as saccadic eye movements [

28]. Additionally, VERTEX, an innovative tool introduced in the article, simulates extracellular potentials generated by neuronal activity in the neocortex and is capable of modeling over 100,000 neurons. Its accuracy is validated through comparisons with experimental recordings in macaque neocortical tissue, making it highly relevant for neuroscience research. Implemented in Matlab, VERTEX offers both flexibility and speed, enhancing the study of brain dynamics in various health and disease conditions [

29].

Building on these tools, recent studies focus on reconstructing local field potentials (LFPs) in the granular layer of the rat cerebellum using spiking neural networks and neural mass models. By leveraging LFPsim and VERTEX, the analysis of transmembrane current variability and neuronal activity offer deeper insights into the biological mechanisms behind LFP generation, revealing critical differences between normal and pathological neuronal states [

30].

Finally, a model employing stochastic differential equations improves the accuracy of simulations of cerebellar granule cells by incorporating experimentally observed variability in their electrical activity. This approach allows for the reproduction of irregular behaviors, such as subthreshold oscillations and variability in action potentials [

31]. The Golgi cell model, on the other hand, analyzes the activation of mossy fibers and its influence on spike generation and synaptic plasticity, considering the distribution of ion channels in different parts of the cell [

32].

Perspective

The use of AI to develop cerebellar architectures has been growing with the passing of the years, focusing on mimicking cerebellar plasticity, such as STDP, to achieve real-time adaptation in motor tasks [

10,

13,

14]. Others utilize ANNs to simulate biomechanical functions, like eye movements or motor control, demonstrating precise coordination and timing [

5,

6,

8]. Additionally, these models often incorporate internal models for forward and inverse motor prediction, replicating the cerebellum ability to adjust motor commands based on sensory feedback [

3,

11].

AI has made significant strides in emulating cerebellar functions, offering grasps into neural processing and applications in robotics and beyond. However, to fully replicate the cerebellum versatility and adaptability, future models must address the limitations of current AI systems, like integrating more complex biological features, enhancing computational efficiency to represent high biological fidelity, and expanding generalization capabilities across diverse tasks that the cerebellum performs.

Regarding the PC, models [

16,

17,

18], and [

19] use Hodgkin-Huxley equations and focus on ionic conductance and synaptic responses, providing a detailed view of the electrophysiological mechanisms of the PC. Model [

20] introduces a probabilistic perspective, while [

21] focuses on the decoding of input patterns. Model [

22] compares the performance of biological models [

16,

17] with an ANN, highlighting the potential of ANNs in neuroscientific research.

AI has the competence to revolutionize the study of PC by providing advanced and adaptive models that complement traditional mathematical models. This not only expands the scope of cell simulation, but also opens up a promising line of research to develop models that are increasingly accurate and customizable, enabling advances in the understanding of neurophysiology and the design of biomedical interventions. With its ability to learn and adapt, AI offers a versatile platform for future studies, positioning itself as a key tool for the investigation of complex biological systems.

The various computational models of the cerebellum play key roles in understanding synaptic dynamics and motor learning. For example, the models of Yamazaki and Tanaka simulate recurrent inhibitory networks, providing detailed insight into the interactions between granule and Golgi cells [

23], while the mathematical model Leffler et al. focuses on cell development in the mouse cerebellum, fitting experimental data [

24]. Regarding long-term synaptic plasticity and prediction of cortical state, respectively, which optimizes motor coordination [

3,

11]. Steuber and Jaeger models focus on neuronal synchronization and storage of activity patterns, contributing to the understanding of temporal coding [

25], while Peddicord describes the connections between cerebellar cortex and spinal pathways [

26]. Tools such as LFPsim and VERTEX facilitate the simulation of bioelectric potentials, improving the analysis of neural activity [

27,

29]. These tools, together with recent studies on spike networks and transmembrane variability, allow a deeper understanding of local field potentials and the differences between normal and pathological neuronal states [

30]. In addition, more recent models, such as those of Parasum and Krichmar et al. allow detailed simulation of bioelectrical behavior and complex neural tasks such as saccadic movements [

27,

28], underscoring the progress in neural simulation and its applicability in biological and artificial conditions.

Although these models have advanced the understanding of cerebellar functions, challenges remain in integrating more complex aspects, such as cognition and emotional regulation. Furthermore, accuracy in simulating neural activity could benefit from models that combine biological and artificial approaches, optimizing both efficiency and fidelity to brain functions.

Table 1 presents an overview of cerebellar features that have already been explored through the models discussed in this review and those that are still unexplored.

Conclusion

There are multiple AI models representing the architecture of the cerebellum, mainly focused on modeling motor functions. However, progress is still needed on the intellectual and emotional aspects. In terms of neurons, mathematical models predominate, and there have been no significant innovations in this area for over a decade.

One of the foundations of AI is the data used to train it to learn the desired functions. Advancing the understanding of the intellectual and emotional workings of the architecture requires correctly understanding the implications of the cerebellum on these functions and obtaining data that reflect them.

Additionally, for the development of AI models of individual neurons, a thorough understanding of each neuron function or the synaptic interactions is necessary to create a robust model. Moreover, the presented models have defined scopes, so they must be adjusted according to the context in which they will be used.

References

- Jimsheleishvili, S. & Dididze, M. Neuroanatomy, Cerebellum. National Library of Medicine, 5381. [Google Scholar]

- Consalez, G. G. , Goldowitz, D., Casoni, F., & Hawkes, R. (2021). Origins, development, and compartmentation of the granule cells of the cerebellum. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 14, Article 611841. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H. , Ishikawa, T., Lee, J. & Kakei, S. The Cerebro-Cerebellum as a Locus of Forward Model: A Review. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 14, (2020).

- Boucheny, C. , Carrillo, R., Ros, E. & Coenen, O. J. M. D. Real-Time Spiking Neural Network: An Adaptive Cerebellar Model. in Lecture notes in computer science 136–144 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Buonomano, D. V. & Mauk, M. D. Neural Network Model of the Cerebellum: Temporal Discrimination and the Timing of Motor Responses. Neural Computation 6, 38–55 (1994).

- Ebadzadeh, M. & Darlot, C. Cerebellar learning of bio-mechanical functions of extra-ocular muscles: modeling by artificial neural networks. Neuroscience 122, 941–966 (2003).

- Gilbert, M. & Miall, R. C. How and Why the Cerebellum Recodes Input Signals: An Alternative to Machine Learning. The Neuroscientist, 28, 206–221 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- Hausknecht, M. , Li, W.-K., Mauk, M. & Stone, P. Machine Learning Capabilities of a Simulated Cerebellum. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 28, 510–522 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Ito, M. Cerebellar circuitry as a neuronal machine. Progress in Neurobiology, 78, 272–303 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Iwadate, K. , Suzuki, I., Watanabe, M., Yamamoto, M. & Furukawa, M. An Artificial Neural Network Based on the Architecture of the Cerebellum for Behavior Learning. in Advances in intelligent systems and computing 143–151 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Kawato, M. & Gomi, H. A computational model of four regions of the cerebellum based on feedback-error learning. Biological Cybernetics, 68, 95–103 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert, D. M. , Miall, R. C. & Kawato, M. Internal models in the cerebellum. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2, 338–347 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; et al. CerebelluMorphic: Large-Scale Neuromorphic Model and Architecture for Supervised Motor Learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 33, 4398–4412 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- Casellato, C.; et al. Adaptive Robotic Control Driven by a Versatile Spiking Cerebellar Network. PLoS ONE, 9, e112265 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan, A. & Diwakar, S. A cerebellum inspired spiking neural network as a multi-model for pattern classification and robotic trajectory prediction. Frontiers in Neuroscience 16, (2022).

- De Schutter, E. & Bower, J. M. An active membrane model of the cerebellar Purkinje cell. I. Simulation of current clamps in slice. Journal of Neurophysiology 71, 375–400 (1994).

- De Schutter, E. & Bower, J. M. An active membrane model of the cerebellar Purkinje cell II. Simulation of synaptic responses. Journal of Neurophysiology 71, 401–419 (1994).

- De Schutter, E. Modelling the cerebellar Purkinje cell: experiments in computo. Progress in Brain Research 427–441 (1994). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellionisz, A. & Llinás, R. A computer model of cerebellar purkinje cells. Neuroscience 2, 37–48 (1977).

- Hakimian, S. , Anderson, C. H. & Thach, W. T. A PDF model of populations of Purkinje cells: Non-linear interactions and high variability. Neurocomputing 26–27, 169–175 (1999).

- Steuber, V. & De Schutter, E. Rank order decoding of temporal parallel fibre input patterns in a complex Purkinje cell model. Neurocomputing 44–46, 183–188 (2002).

- Steuber, V. & De Schutter, E. Long-term depression and recognition of parallel fibre patterns in a multi-compartmental model of a cerebellar Purkinje cell. Neurocomputing 38–40, 383–388 (2001).

- Yamazaki, T. & Tanaka, S. Computational Models of Timing Mechanisms in the Cerebellar Granular Layer. The Cerebellum, 8, 423–432 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Leffler, S. R.; et al. A Mathematical Model of Granule Cell Generation During Mouse Cerebellum Development. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 78, 859–878 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Steuber, V. & Jaeger, D. Modeling the generation of output by the cerebellar nuclei. Neural Networks, 47, 112–119 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- R.G. Peddicord et al. A computational model of cerebellar cortex and peripheral muscle, International Journal of Bio-Medical Computing, (2004).

- Parasuram, H.; et al. Computational Modeling of Single Neuron Extracellular Electric Potentials and Network Local Field Potentials using LFPsim. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 10, (2016).

- Krichmar, J. L. , Ascoli, G. A., Hunter, L. & Olds, J. L. A model of cerebellar saccadic motor learning using qualitative reasoning. in Lecture notes in computer science 133–145 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, A. , Linne, M.-L. & Yli-Harja, O. Stochastic Differential Equation Model for Cerebellar Granule Cell Excitability. PLoS Computational Biology, 4, e1000004. [Google Scholar]

- Modeling population network activity using lfpsim, spiking neurons and neural mass models. (2017, September 1). IEEE Conference Publication | IEEE Xplore. https://ieeexplore.ieee.

- Saarinen, A. , Linne, M., & Yli-Harja, O. (2008). Stochastic Differential equation model for cerebellar granule cell excitability. PLoS Computational Biology, 4(2), e1000004. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoli, S. , Ottaviani, A., Casali, S., & D’Angelo, E. (2020). Cerebellar Golgi cell models predict dendritic processing and mechanisms of synaptic plasticity. PLoS Computational Biology, 16(12), e1007937. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, K. , Oberdick, J., Rossi, F. et al. Besides Purkinje cells and granule neurons: an appraisal of the cell biology of the interneurons of the cerebellar cortex. Histochem Cell Biol 130, 601–615 (2008). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).