1. Introduction

Recent years have witnessed an upsurge in network attacks. Among these, Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) stand out as complex, prolonged, and meticulously orchestrated cyberattacks. Their inherent complexity hampers timely detection, and successful APT attacks often result in substantial losses. Consequently, tracing the origins of APTs and ensuring robust cybersecurity have underscored the critical importance of threat intelligence.

Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) encompasses both existing and emerging threats to critical assets, detailing mechanisms, indicators, implications, and actionable recommendations [

1]. As an indispensable resource, CTI enables cybersecurity professionals to effectively identify, analyze, and mitigate risks.

Despite its significance, threat intelligence is frequently disseminated in unstructured formats such as web pages, emails, and similar sources. This unstructured nature poses considerable challenges for rapidly extracting pertinent information from vast datasets. As a result, Named Entity Recognition (NER) has emerged as a pivotal technique for automating the extraction of critical information related to network attacks.

Recent research in CTI-oriented NER has yielded notable advancements, including the development of domain-specific datasets and the proposal of tailored NER models (a comprehensive review is provided in

Section 2). Nevertheless, significant gaps remain that hinder the practical application of threat intelligence analysis. First, existing datasets predominantly rely on semi-structured texts (e.g., forums, blogs, and emails) and lack standardization, with an absence of large-scale, uniformly annotated collections exhibiting consistent data distributions and label definitions. Second, prevailing modeling approaches treat network threat intelligence as conventional text, overlooking its unique characteristics within cybersecurity reports. Consequently, these models do not fully leverage domain-specific knowledge, resulting in an inadequate capture of the nuanced technical intricacies of threat intelligence.

In summary, the principal contributions of this paper are as follows:

We delineate the challenges inherent in existing dataset construction and introduce CTINER—a novel dataset specifically designed for Named Entity Recognition in Cyber Threat Intelligence—to address the paucity of suitable NER datasets.

We further propose PROMPT-BART, a multi-prompt NER model that seamlessly integrates domain-specific threat intelligence knowledge. By leveraging prefix, demonstration, and template prompts, PROMPT-BART expands its knowledge base and overcomes the limitations of conventional single-prompt approaches.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work.

Section 3 introduces the CTINER dataset, while

Section 4 details the PROMPT-BART model based on prompt-based learning for NER.

Section 5 presents experimental evaluations, and

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Research on Methods for Named Entity Recognition

2.1.1. General Domain Named Entity Recognition Research

Named Entity Recognition (NER) aims to detect and classify named entities in text into pre-defined categories. Over the years, NER has evolved from rule- and dictionary-based approaches to machine learning and deep learning methods, with recent advances incorporating pre-trained and large-scale models.

Ma et al. [

2] proposed an end-to-end model that combines Bi-LSTM, CNN, and CRF, where character-level features extracted via CNN are concatenated with Word2Vec embeddings. Pinheiro et al. [

3] similarly integrated CNN and CRF, while Jiang et al. [

4] addressed Chinese character ambiguity using a BERT-Bi-LSTM-CRF model for electronic medical records, showing that BERT enhances semantic representation. Fang et al. [

5] tackled cross-domain few-shot learning by incorporating a memory module to store source domain information, and Chen et al. [

6] developed HEProto, a multi-task model that jointly performs span detection and type classification.

Arora et al. [

7] introduced Split-NER, decomposing NER into two subtasks: a question-answering model first detects entity spans without labels, and then a QA-style classifier assigns entity types. This two-stage fine-tuning of BERT results in efficient training and strong performance. Wang et al. [

8] proposed OaDA to enhance few-shot NER by generating multiple permutations of entities, ensuring unique input–output pairs, and introduced an OaDA-XE loss function to mitigate the one-to-many mapping issue. Their approach significantly improves the few-shot performance of pre-trained language models on three benchmark datasets.

2.1.2. Named Entity Recognition Research in Cyber Threat Intelligence

Cyber threat intelligence NER shares methodological similarities with general-domain NER but demands additional domain-specific knowledge due to the unique characteristics of cybersecurity entities.

Liao et al. [

9] employed a rule-based method to extract four predefined entity types, while Zhu et al. [

10] classified compromise indicators (IOCs) using a four-stage manual analysis. Zhou et al. [

11] combined a Bi-LSTM, attention mechanism, and spelling features to detect low-frequency IOCs in security reports, whereas Dionisio et al. [

12] utilized a Bi-LSTM-CRF model to extract IOC entities from tweets.

To tackle challenges such as mixed-language texts and specialized vocabulary, Wang et al.[

13] integrated boundary features with an iterative dilated CNN for NER. Chen et al. [

14] streamlined the conventional BERT-BiLSTM-CRF framework by removing the Bi-LSTM layer and directly feeding BERT-generated word vectors into a CRF, thereby achieving high accuracy in both real-world scenarios and malware intelligence datasets.

2.1.3. Research on Prompt Engineering-based Named Entity Recognition

Prompt learning reformulates downstream tasks by converting input data into formats compatible with pre-trained language models using predefined templates, thereby harmonizing the objectives of pre-training and fine-tuning. This approach mitigates performance degradation inherent in traditional paradigms, where distinct stages involve disparate tasks and optimization goals, by recasting many natural language processing tasks as masked language model tasks.

Chen et al. [

15] introduced the Self-Describing Network (SDNet), which leverages labeled data and external knowledge for transfer learning. Ben-David et al. [

16] proposed the PADA model for automated prompt generation. Other generative approaches include prompt decomposition [

17], prefix prompt methods [

18], and a combination of template-based prompts with multi-level neural networks to address ambiguous Chinese NER [

19].

Ye et al. [

20] developed a two-stage prompt learning framework that decomposes NER into entity localization and type classification. The framework employs distant supervision to efficiently train the localization module and uses concise prompt templates to train the classification module. During inference, entity spans are first predicted and then reformulated via prompt templates to enable rapid and accurate type prediction.

Xia et al. [

21] introduced the MPE framework, which embeds semantic information of entities directly into the prompt construction process to enhance recognition accuracy. To address data scarcity, MPE decomposes training data into domain-agnostic meta-tasks tailored to NER and employs a dedicated prompt meta-learner to optimize meta-prompts.

In unsupervised and low-resource scenarios, prompt learning demonstrates significant advantages in cost-effectiveness and flexibility. Validated in tasks such as knowledge question answering and text generation, this approach shows promise for threat intelligence analysis, potentially outperforming methods that rely on traditional pre-training and fine-tuning. However, the application of prompt engineering in named entity recognition for cyber threat intelligence remains relatively scarce, which is also the research direction we are dedicated to advancing.

2.2. Construction of Datasets for Named Entity Recognition

2.2.1. General Domain Datasets

Named entity recognition (NER) has advanced significantly with the availability of authoritative benchmark datasets.For example, Sang et al. [

22] developed the CoNLL-2003 dataset to identify and classify entities (e.g., person names, locations, organizations), thereby establishing a standardized evaluation benchmark. Similarly, Linguistic Data Consortium(LDC) introduced ACE2005[

23], a multilingual dataset encompassing English, Arabic, and Chinese, which addresses five subtasks: entities, values, temporal expressions, relations, and events. Although these datasets effectively evaluate general NER performance, they offer limited utility for specialized domains such as cyber threat intelligence, highlighting the need for domain-specific datasets.

2.2.2. Cybersecurity Domain Datasets

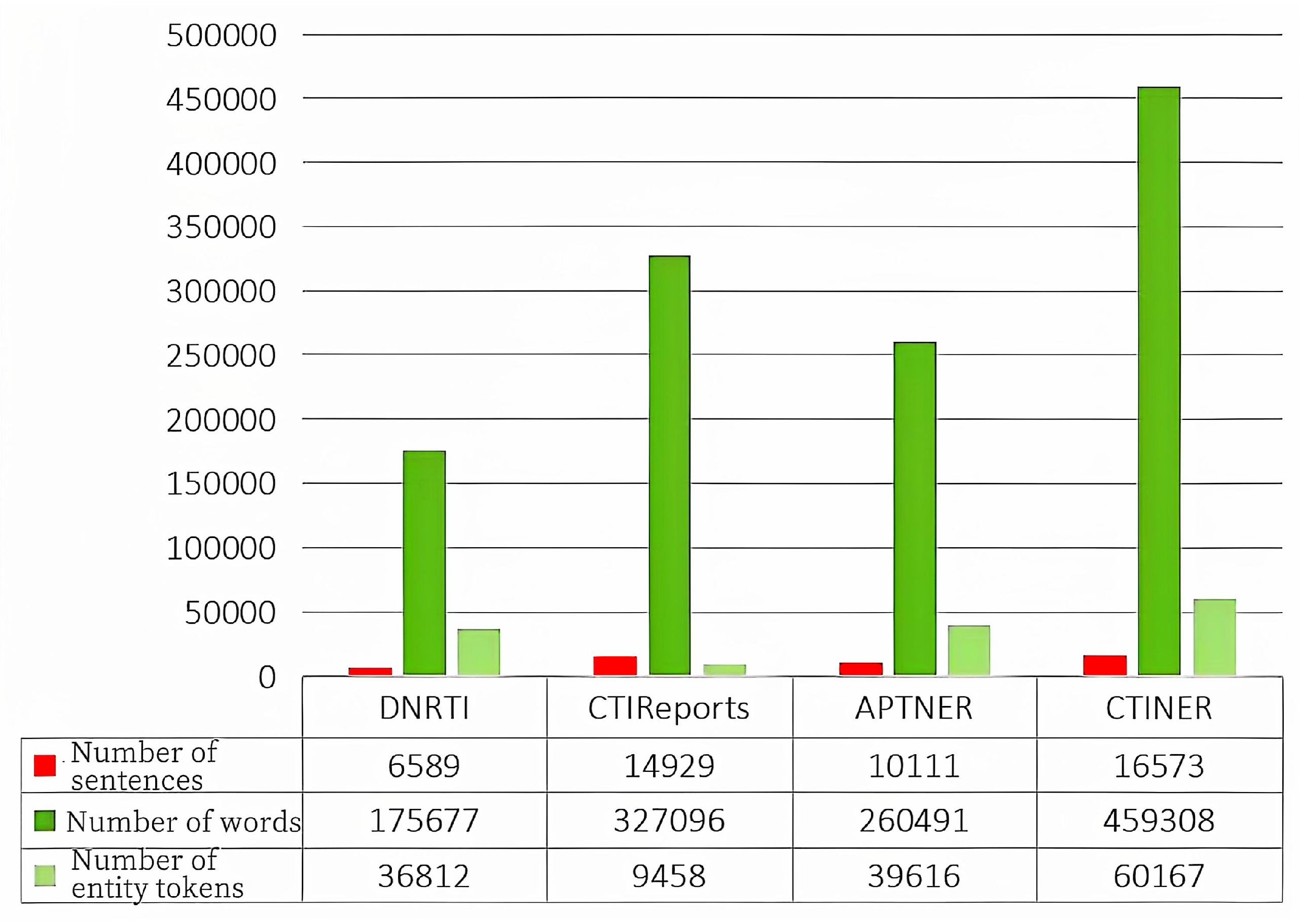

Wang et al.[

24] constructed the DNRTI dataset from over 300 threat intelligence reports, predefining 13 entity labels over 175,677 words with 36,812 annotations (approximately 21% of the total), partitioned into training, test, and validation sets (7:1.5:1.5 ratio). Kim et al. [

25] developed the CTIReports dataset from 160 unstructured PDFs, featuring 10 entity types across 327,096 words and 9,458 annotations. Moreover, in 2022, Wang et al. [

26] integrated cybersecurity articles, blogs, and open-source reports to create the APTNER dataset, which defines 21 entity labels over 260,491 words with 39,616 annotations (approximately 15.2%), using a similar data split.

Structured Threat Information Expression 2.1 (STIX 2.1)[

27] is a standardized language and serialization format designed for the exchange of Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI). It enables organizations to share CTI in a consistent, machine-readable manner, thereby assisting the security community in better understanding potential computer attacks and in more promptly and effectively predicting and responding to such threats.

Significant variations in entity label counts and annotation formats—often misaligned with industry standards such as STIX 2.1—limit the dataset’s utility for fine-grained entity extraction in large-scale threat intelligence, and preclude them from achieving the authoritative status of benchmarks like CoNLL-2003 or ACE2005.

3. Construction of Cyber Threat Intelligence Datasets

3.1. Dataset Extraction Methods and Corresponding Modules

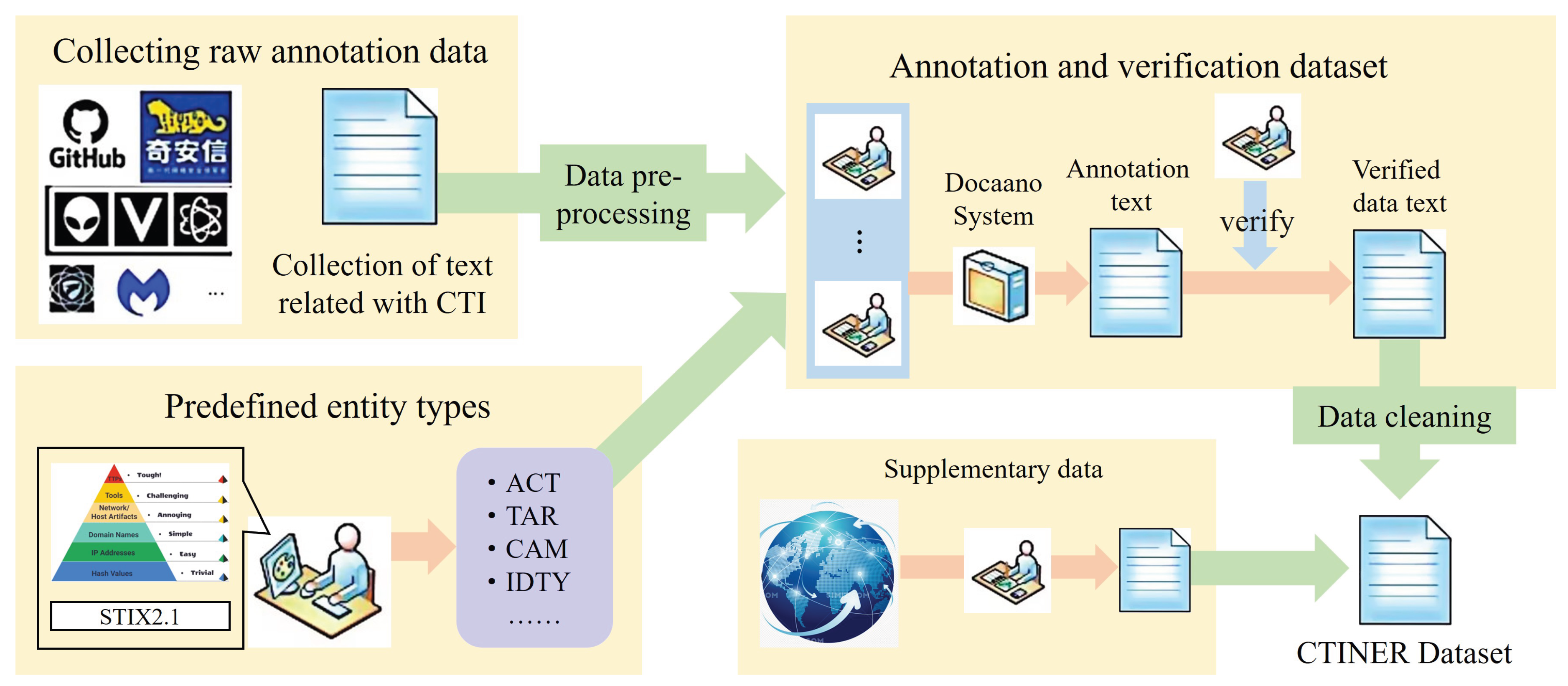

The CTINER dataset construction process is outlined in

Figure 1 and includes seven modules: threat intelligence acquisition, data preprocessing, entity pre-definition, annotation and verification, data format conversion, annotation data cleaning, and rare data supplementation. Each module is described in detail below.

3.1.1. Threat Intelligence Acquisition Module

The dataset primarily consists of APT analysis reports, which detail the attack methods and consequences of attacks targeting specific organizations. To construct the dataset, raw intelligence data was sourced from cybersecurity companies and open-source repositories such as GitHub. The collected APT reports were processed into TXT format, retaining only the main body of the text.

3.1.2. Data Preprocessing Module

The preprocessing steps include verifying punctuation at paragraph ends and segmenting the text into sentences and words using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK). Afterward, data cleaning is performed, ensuring proper spacing, word count consistency, and checking whether the text consists of English alphabet characters.

3.1.3. Entity Pre-definition Module

Entity labels, primarily related to attack indicators, were pre-defined based on existing classification standards. The pyramid model, which shown in

Figure 1 divides threat intelligence into six layers, each representing different levels of usable information and associated challenges. Selected indicators include network features (URLs, sample files, OS), attack tools (legitimate tools, malware), and TTPs (vulnerabilities, attack campaigns, malicious emails). The STIX 2.1 specification [

27] served as a reference for defining entity standards, facilitating standardized communication of threat intelligence. This approach enhances the dataset’s compatibility with existing and future threat analysis systems. The paper defines 13 entity labels, as detailed in

Table 1.

3.1.4. Annotation and Verification Module

Due to the domain-specific vocabulary and entity types, automated annotation tools were insufficient for accurate entity recognition. Therefore, manual annotation was conducted by volunteers with cybersecurity expertise. The data annotated includes the TXT corpus from the preprocessing module, and the 13 entity labels defined in the entity pre-definition module. The Doccano system was used for annotation.

3.1.5. Data Format Conversion Module

For easier processing and visualization, the module converts the exported JSONL annotation files from Doccano into JSON and subsequently into TXT format, employing the BIO tagging format for named entity recognition tasks. The final dataset consists of two columns: each row contains a word and its corresponding label, separated by a space, with sentences separated by blank lines. The tag format is: Tag = B, I, O + “-” + ACT, TAR, CAM, IDTY, VUL, TOOL, MAL, LOC, TIME, FILE, URL, OS, EML, O, where "O" represents non-entity words.

3.1.6. Annotation Data Cleaning Module

Given the typically long sentences and low entity density in cyber threat intelligence, many sentences contain no entities. These sentences are removed to enhance the proportion of entity-labeled sentences and address data imbalance.

3.1.7. Rare Data Supplementation Module

Certain entity types in APT reports are underrepresented due to the nature of the reports. To address this, open-source data was sourced from the internet to supplement underrepresented entities, based on statistical analysis of the dataset.

3.2. Dataset Overview and Entity Distribution

The dataset is split into training, testing, and validation sets with a ratio of 7:2:1, as shown in

Table 2. The dataset comprises 16,573 sentences, 459,308 words, 42,549 entities, and 60,167 entity tokens. On average, each sentence contains approximately 28 words, indicating that the sentences in cyber threat intelligence texts are relatively lengthy but contain fewer entities. This characteristic presents challenges in constructing a knowledge-rich named entity recognition dataset for the cyber threat intelligence domain.

The top five most frequent entities in the CTINER dataset are IDTY (6,778), TOOL (6,544), TAR (6,358), TIME (5,171), and ACT (4,607), which play a critical role in network threat assessment and enhancing cybersecurity.

3.3. Comparison with Other Datasets: DNRTI, CTIReports, APTNER

To assess the CTINER dataset’s advancement and rationality, it is compared with other open-source datasets in the cyber threat intelligence domain. The comparison includes predefined label rationality, entity density, and overall dataset characteristics.

3.3.1. Label Rationality

The APTNER dataset [

26] defines 21 entity types, increasing annotation complexity and compromising dataset quality. Certain entity types, such as IP addresses and MD5 values, have limited utility due to their time-sensitive nature, with attackers frequently altering these indicators. To address this, CTINER eliminates these time-sensitive entities and merges those with overlapping meanings (e.g., merging security teams and identity authentication into IDTY, domain names and URLs into URL, and vulnerability names and identifiers into VUL).

In the DNRTI dataset [

24], CTINER modifies the attack objective to "attack target" based on the threat information expression model. DNRTI also suffers from overlapping or ambiguously defined entity types, such as spear phishing, and lacks critical entities like malware.

The CTIReports dataset [

25] primarily focuses on IP addresses, malware, and URLs, which are insufficient for downstream tasks such as knowledge graph construction or machine-readable intelligence generation.

In contrast, the CTINER dataset incorporates the STIX 2.1 specification, the pyramid model, and the threat information expression model, defining 13 distinct entity types. These types are independent and better support downstream research in threat intelligence.

3.3.2. Dataset Scale Comparison

An analysis of dataset characteristics (sentence count, word count, and entity token count) reveals that the CTINER dataset contains significantly more sentences, words, and entity tokens than the other three datasets in comparison, shown in

Figure 2, summarizes the CTINER dataset alongside other cyber threat intelligence datasets, with the data split ratio of training, testing, and validation sets.

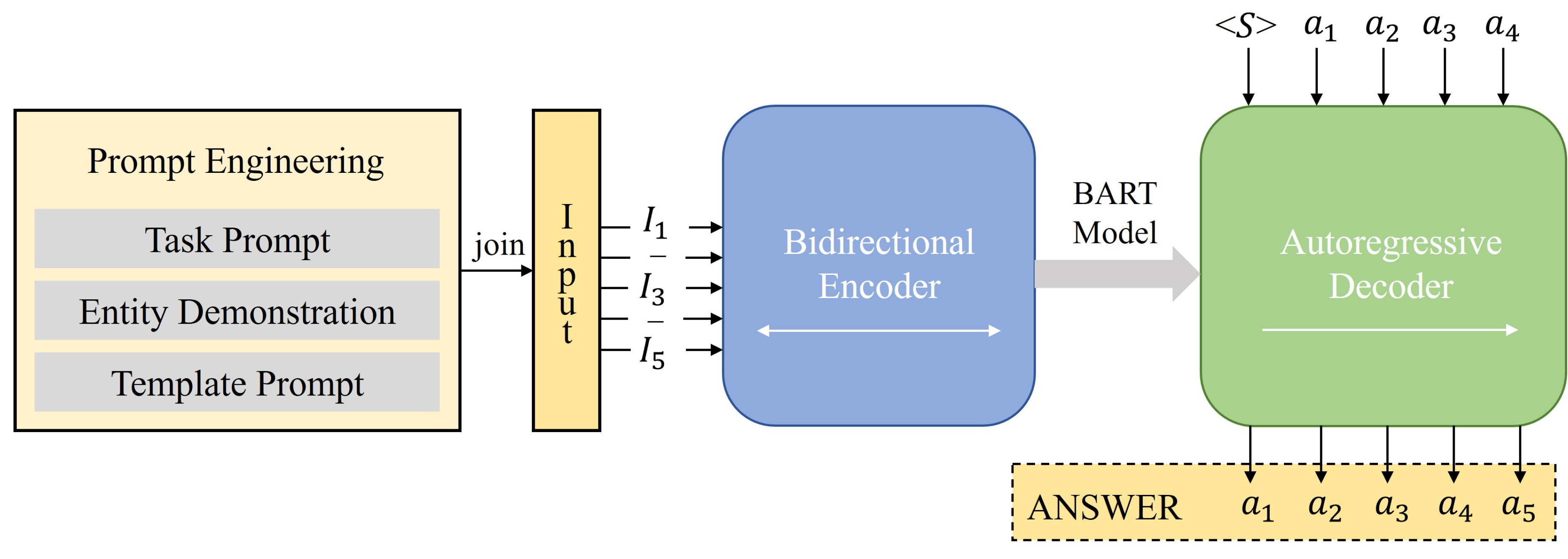

4. Model

Prompt engineering fundamentally involves embedding high-quality knowledge into the model training process by leveraging human-provided prior information to guide learning and activate the model’s reasoning capabilities. In this study, we introduce the PROMPT-BART model, which employs three distinct types of prompts—task prompts, entity demonstration prompts, and template prompts—as illustrated in

Figure 3.

4.1. Model Construction

We design and integrate task prompts, entity demonstration prompts, and template prompts along with the original input to form the comprehensive input for the PROMPT-BART model. The simultaneous use of these three prompt types offers multi-level guidance, effectively merging high-level task instructions with concrete examples to produce accurate and reliable outputs. This multi-prompt strategy enhances the model’s reasoning ability and output consistency, thereby reducing errors and uncertainty—especially in complex tasks.

4.1.1. Constructing Task Prompts

Task prompts serve to define the task and clarify the model’s role, thus guiding its behavior and enriching the semantic context. For example, the first sentence introduces the model with a statement such as “I am an experienced cybersecurity expert and a proficient linguist.” In the context of a cybersecurity NER task, the subsequent sentence specifies, “This task involves named entity recognition for cybersecurity, aiming to label entity types in the provided sentence.” The final sentence, “Below are some demonstrations; please make the appropriate predictions,” directs the model’s focus toward the provided examples.

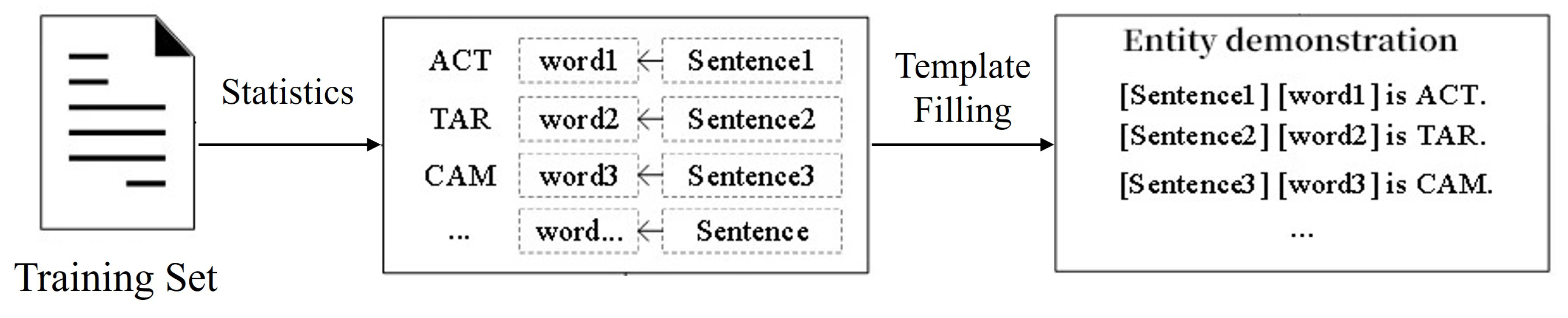

4.1.2. Constructing Entity Demonstration Prompts

Entity demonstration prompts provide clear task guidance by presenting representative examples for each entity type. We employ a statistical method to select exemplar entities for each category, as depicted in

Figure 4. For each entity type, the most frequent and concise entity from the training set is chosen as the contextual reference. Sentences are then constructed based on these entities, as detailed in

Table 3. This approach ensures that the model is furnished with clear, contextually relevant examples to inform its predictions.

4.1.3. Constructing Template Prompts

Template prompts are carefully designed to provide clear, structured guidance that enhances both the model’s understanding of the input and its generation of outputs in a predetermined, standardized format. By explicitly outlining task requirements and offering a consistent framework, these prompts not only reduce ambiguity and bolster the interpretability and reliability of predictions but also improve the model’s comprehension of varied input expressions. The multi-prompt approach leverages multiple prompt inputs during inference to facilitate robust predictions. Template prompt construction involves two key steps:

Prompt Paraphrasing:

By transforming the original template into multiple linguistically diverse yet semantically equivalent expressions, paraphrasing generates varied prompts that enable the model to accurately comprehend task requirements despite varied phrasings. For example, an original prompt such as “Identify the entities in the sentence” might be rephrased as “Locate all words or phrases with specific meanings in the sentence,” thereby mitigating overfitting to a single formulation and enhancing robustness. To boost template diversity and lexical richness, we utilize a fine-tuned fairseq English-German translation model along with fastBPE subword segmentation and Moses tokenization.

This process translates and refines the initial prompts, resulting in a collection comprising three general-purpose templates and two cybersecurity-specific templates—culminating in five template pairs (see

Table 4). This step not only expands the expressive range but also reinforces the model’s adaptability to varied linguistic patterns.

Prompt Decomposition:

Decomposing a complex template into smaller sub-prompts allows the model to sequentially focus on distinct aspects of the task, reducing interference and ambiguity when processing intricate information. For instance, a sentence containing multiple entities may be split into sub-prompts like “Identify the first entity” and “Identify the second entity,” enabling the model to incrementally complete the task and ensure each entity is accurately captured. In our model, this step entails breaking down a main prompt into several sub-prompts, each independently addressing a specific entity span. By decomposing the prompt, the model is enabled to focus on individual entity predictions, thereby improving precision and reducing ambiguity.

In summary, integrating these three prompt types endows the PROMPT-BART model with comprehensive, multi-level guidance, thereby achieving superior performance in cybersecurity-oriented named entity recognition tasks.

4.2. Model Training and Inference

The task prompt

T, entity demonstrations

M, and the original input sequence

X are jointly fed into the encoder of the BART model, as shown in (

1) and (

2), ultimately generating a natural sentence that contains the entities and their corresponding types (i.e.the answer).

Here,

and

, where

N and

M represent the lengths of the input and output sequences, respectively. Non-entities are represented as “

is not a named entity,” where

denotes a non-entity word, and its unit is a token.

For each

pair, the input is fed into the BART model’s encoder to obtain a hidden representation,

, of the input sequence. This hidden representation, along with the token

output by the decoder from the previous step, serves as the input for the decoder in the current step, as shown in (

3). The conditional probability of the token output

at the current stage is specified in (

4).

Where

W and

b represent trainable parameters, and

i represents the

i stage.

The decoder-side model’s loss function is represented by (

5).

For each span

in the original input sequence

X, we combine the span with each label

using a template to obtain the

, where

. The trained model calculates a score for each

, assigning the label with the highest score to

, as shown in the following formula.

5. Experiment

The experiments in this study were conducted using the Torch 2.1.0 deep learning framework implemented with Python 3.11.0, ensuring a robust and reproducible computational environment. Key configurations of the experimental setup are summarized in

Table 5.

5.1. Comparison and Analysis of Template Prompts

To assess the efficacy of template prompts, we selected seven representative sentence structures for entity recognition from five pairs of bidirectionally translated prompt templates (refer to

Table 4). For non-entity cases, a uniform template—“

is not a named entity,” where “

” denotes a term that does not constitute an entity—was applied. The experimental results (

Table 6) reveal that shorter templates consistently outperform longer ones in terms of Precision, Recall, and F1 score. We hypothesize that longer templates tend to incorporate redundant information, potentially obscuring the essential content required for accurate model comprehension, while also incurring increased resource consumption that may further degrade performance. Consequently, the final template adopted for the PROMPT-BART model is “

is

.”

5.2. Comparison of NER Models

The PROMPT-BART model was benchmarked against several named entity recognition (NER) models based on deep learning and prompt-based approaches. As presented in

Table 7, PROMPT-BART achieved an F1 score improvement ranging from 4.26% to 8.3% over the deep learning-based NER baseline models. Furthermore, compared to the prompt-based NER model Template-NER, PROMPT-BART exhibited an additional F1 score enhancement of 1.31%.

5.3. Ablation Experiment Results and Analysis

An ablation study was conducted on the PROMPT-BART model to evaluate the contribution of each prompt component. The results, shown in

Table 8, indicate that the removal of either the task prompt or the entity demonstration prompt leads to declines in Precision, Recall, and F1 score—with F1 scores decreasing by 1.06% and 1.16%, respectively. These findings substantiate the effectiveness of the prompt engineering strategy employed in this study.

6. Conclusions

This paper introduces the CTINER dataset, which defines 13 distinct entity types, and presents the PROMPT-BART Named Entity Recognition (NER) model. Given the unique characteristics of the cyber threat intelligence domain, future research may consider the following directions:

Development of an Open-Source Annotation System: Creating an annotation system (e.g., based on Doccano) that leverages its AutoLabel feature to facilitate efficient automated annotation. Additionally, incorporating human-in-the-loop reinforcement techniques could further streamline the processing of unlabeled data.

Integration of GANs with Prompt Learning: Employing Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to generate novel training samples could enable more effective model training, thereby improving the overall generalization capabilities of the NER model.

7. Patents

This section is not mandatory, but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xinzhu Feng and Xinxin Wei; methodology, Xinzhu Feng and Songheng He; software, Xinzhu Feng and Xinxin Wei; validation, Xinxin Wei and Songheng He; formal analysis, Xinzhu Feng and Songheng He; investigation, Xinxin Wei, Runshi Liu and Huanzhou Yue; data curation, Xinxin Wei, Runshi Liu and Huanzhou Yue; writing—original draft preparation, Xinzhu Feng and Songheng He; writing—review and editing, Xinzhu Feng and Songheng He; visualization, Xinzhu Feng and Songheng He; supervision, Xuren Wang; project administration, Xinzhu Feng and Songheng He; funding acquisition, Xuren Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded by Open Foundation of Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education of China (No.KLCS20240206)

Data Availability Statement

The dataset employed in this study is proprietary but has been made accessible for research purposes via the following repository:

https://github.com/Fxz03/CTINER_dataset. Access may be subject to certain restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- McMillan, R.; Pratap, K. Market guide for security threat intelligence services. Gartner Report (G00259127) 2014.

- Ma, X.; Hovy, E. End-to-end sequence labeling via bi-directional LSTM-CNNs-CRF. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2016; pp. 1064–1074.

- Pinheiro, P.; Collobert, R. Recurrent convolutional neural networks for scene labeling. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2014; pp. 82–90.

- Jiang, S.; Zhao, S.; Hou, K. A BERT-BiLSTM-CRF model for Chinese electronic medical records named entity recognition. In 12th International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation (ICICTA), 2019; pp. 166–169.

- Fang, J.; Wang, X.; Meng, Z. MANNER: A variational memory-augmented model for cross domain few-shot named entity recognition. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2023; pp. 4261–4276.

- Chen, W.; Zhao, L.; Luo, P. Heproto: A hierarchical enhancing protonet based on multi-task learning for few-shot named entity recognition. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2023; pp. 296–305.

- Arora, J.; Park, Y. Split-NER: Named entity recognition via two question-answering-based classifications. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), Toronto, Canada, July 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: pp. 416.

- Wang, H.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, W.; Soh, D.W.; Bing, L. Order-Agnostic Data Augmentation for Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition. In *Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers)*, Bangkok, Thailand, August 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 7792–7807. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.421. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Yuan, K.; Wang, X.F. Acing the IOC Game: Toward Automatic Discovery and Analysis of Open-Source Cyber Threat Intelligence. In *Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security*, 2016; pp. 755–766.

- Zhu, Z.; Dumitras, T. Chainsmith: Automatically Learning the Semantics of Malicious Campaigns by Mining Threat Intelligence Reports. In 2018 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P); 2018; pp. 458–472.

- Zhou, S.; Long, Z.; Tan, L. Automatic Identification of Indicators of Compromise Using Neural-Based Sequence Labelling. In Proceedings of the 32nd Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation; 2018; pp. 849–857.

- Dionísio, N.; Alves, F.; Ferreira, P.M. Cyberthreat Detection from Twitter Using Deep Neural Networks. In 2019 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2019; pp. 1–8.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.-h.; Li, H.; Huang, W.-j. Named Entity Recognition in Threat Intelligence Domain Based on Deep Learning. Journal of Northeastern University (Natural Science) 2023, 44(1), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.12068/j.issn.1005-3026.2023.01.005. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-S.; Hwang, R.-H.; Sun, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-D.; Pai, T.-W. Enhancing Cyber Threat Intelligence with Named Entity Recognition Using BERT-CRF. In GLOBECOM 2023 - 2023 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2023; pp. 7532–7537. https://doi.org/10.1109/GLOBECOM54140.2023.10436853. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Lin, H. Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition with Self-Describing Networks. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022; pp. 5711–5722.

- Ben-David, E.; Oved, N.; Reichart, R. PADA: Example-Based Prompt Learning for On-the-Fly Adaptation to Unseen Domains. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2022, 10, 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00468. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J. Template-Based Named Entity Recognition Using BART. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP; 2021; pp. 1835–1845.

- Chen, X.; Zhang, N.; Li, L. LightNER: A Lightweight Generative Framework with Prompt-Guided Attention for Low-Resource NER. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2022; pp. 2374–2387.

- Wang, X.; Wei, C.; Zhang, L. Chinese Named Entity Recognition Based on Prompt Learning and Multi-Level Feature Fusion. Journal of Data Acquisition and Processing 2024, 39(4), 1020–1032.

- Ye, F.; Huang, L.; Liang, S.; Chi, K. Decomposed Two-Stage Prompt Learning for Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition. Information 2023, 14(5), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/info14050262. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Tong, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X. MPE3: Learning Meta-Prompt with Entity-Enhanced Semantics for Few-Shot Named Entity Recognition. Neurocomputing 2025, 620, 129031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2024.129031. [CrossRef]

- Tjong Kim Sang, E.F.; De Meulder, F. Introduction to the CoNLL-2003 Shared Task: Language-Independent Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Natural Language Learning at HLT-NAACL 2003; 2003; pp. 142–147.

- Linguistic Data Consortium. ACE 2005 Multilingual Training Corpus. Linguistic Data Consortium, 2006.

- Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Ao, S. DNR-TI: A Large-Scale Dataset for Named Entity Recognition in Threat Intelligence. In 2020 IEEE 19th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom); 2020; pp. 1842–1848.

- Kim, G.; Lee, C.; Jo, J. Automatic Extraction of Named Entities of Cyber Threats Using a Deep Bi-LSTM-CRF Network. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2020, 11, 2341–2355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-020-01122-6. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, S.; Xiong, Z. APTNER: A Specific Dataset for NER Missions in Cyber Threat Intelligence Field. In 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD); 2022; pp. 1233–1238.

- OASIS Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) Technical Committee. STIX 2.1. OASIS, 2019. STIX Version 2.1 Specification. Available: https://docs.oasis-open.org/cti/stix/v2.1/csprd01/stix-v2.1-csprd01.html.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).