2.1. Data Description

The foundation of this study rests upon the export data from S.P. AbonneeService's database systems. This dataset represents a complete cross-sectional snapshot of subscription-related information, encompassing behavioral, transactional, and demographic patterns essential for churn prediction modeling.

The dataset architecture is organized into four sections that collectively capture the subscription lifecycle and dynamics of the customer relationship. These categories include Subscriber Data, Subscription Data, Invoice Data, and Statistical Data, each serving distinct analytical purposes. This approach enables a comprehensive analysis of customer behavior patterns while preserving the details necessary for accurate churn prediction across heterogeneous publisher environments.

2.1.1. Subscriber Data

The subscriber data component encompasses comprehensive demographic, contact, and preference information for both subscription recipients and financial payers within the subscription ecosystem. This dual-entity structure acknowledges the complexity of modern subscription relationships, particularly in gift subscription scenarios where the beneficiary and financial responsible party represent distinct individuals with separate behavioral profiles and communication preferences.

Recipient subscriber data captures complete customer profiles including personal identification details, comprehensive address information spanning street-level specificity through international postal systems, and multi-channel contact information encompassing various email addresses, telephone numbers, and traditional correspondence methods. The demographic component includes gender classification, formal titles, and complete name structures that accommodate international naming conventions and cultural variations across S.P. AbonneeService's diverse customer base.

Financial and administrative elements within subscriber data include banking information necessary for payment processing, tax identification numbers for compliance purposes, and detailed communication preferences that govern customer contact permissions.

Payer subscriber data maintains an identical structure to recipient data, populated exclusively in scenarios where the subscription financial responsibility differs from that of the subscription beneficiary. This approach enables complete analysis for gift subscription scenarios while maintaining data integrity through consistent field structures and validation requirements across both subscriber entity types.

2.1.2. Subscription Data

Subscription data represents the core analytical component of the dataset, containing detailed information about individual subscription instances and their lifecycle characteristics. Each subscription record maintains a unique identification spanning over 200 titles across multiple publishing categories within S.P. AbonneeService's scope.

Publication-specific information, including content type, delivery method, and editorial focus, enables analysis across different forms of publishing. Subscription acquisition data captures the complete customer journey, from the initial contact method to detailed source attribution, promotional campaign identification, and registration methodology, enabling effective marketing analysis and informed decision-making.

Pricing and payment structures within subscription data include detailed tariff classifications, payment frequency specifications, and delivery quantity tracking, which accommodates varying subscription models ranging from weekly publications to quarterly journals. The payment processing component tracks both completed transactions and obligations.

Subscription lifecycle management data captures the temporal evolution of customer relationships through comprehensive tracking of start and end dates, renewal behavior patterns, and administrative status modifications. Cancellation data provides detailed attribution, including methodology employed, underlying reasons for discontinuation, and timing patterns that reveal seasonal and behavioral trends essential for predictive modeling.

2.1.3. Invoice Data

The invoice data component provides a focused snapshot of the most recent billing interaction for each subscription, representing the current financial status rather than comprehensive historical billing records.

Current invoice information includes detailed billing identification, transaction timing, and comprehensive payment status classification that distinguishes between various stages of the billing lifecycle. Payment status tracking encompasses initial invoicing confirmation, successful payment completion, automated banking debits, and identification of outstanding balances, providing essential indicators of customer financial engagement and potential payment-related churn triggers.

Collection and reminder data within the invoice component tracks customer response patterns to payment requests, including detailed timing of reminder communications and customer payment behavior following collection efforts. This information provides critical insights into financial issues and payment pattern disruptions that frequently precede subscription cancellation decisions, making it particularly valuable for predictive modeling focused on payment-related churn scenarios.

2.1.4. Statistical Data

The statistical data component serves a dual purpose, containing both processed derivatives of the primary data categories and unique metrics that cannot be derived from the base data alone. The processed elements provide standardized versions of subscriber, subscription, and invoice information.

The primary value of statistical data lies in its behavioral and interaction metrics, which extend beyond transactional records to capture service quality indicators and patterns of customer relationships. Delivery performance tracking encompasses detailed complaint histories and service interruption patterns, reflecting operational effectiveness and customer satisfaction levels. These metrics provide essential context for understanding non-financial churn triggers related to service quality and operational performance. Customer service interaction data within the statistical component reveals customer engagement patterns by facilitating the number of interactions with customer service.

Historical subscription patterns captured within statistical data offer complex insights into customer behavior that extend beyond current subscription status. These metrics include subscription duration tracking, renewal pattern analysis, and cross-portfolio subscription behavior, which reveals customer lifecycle patterns essential for developing a comprehensive retention strategy.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

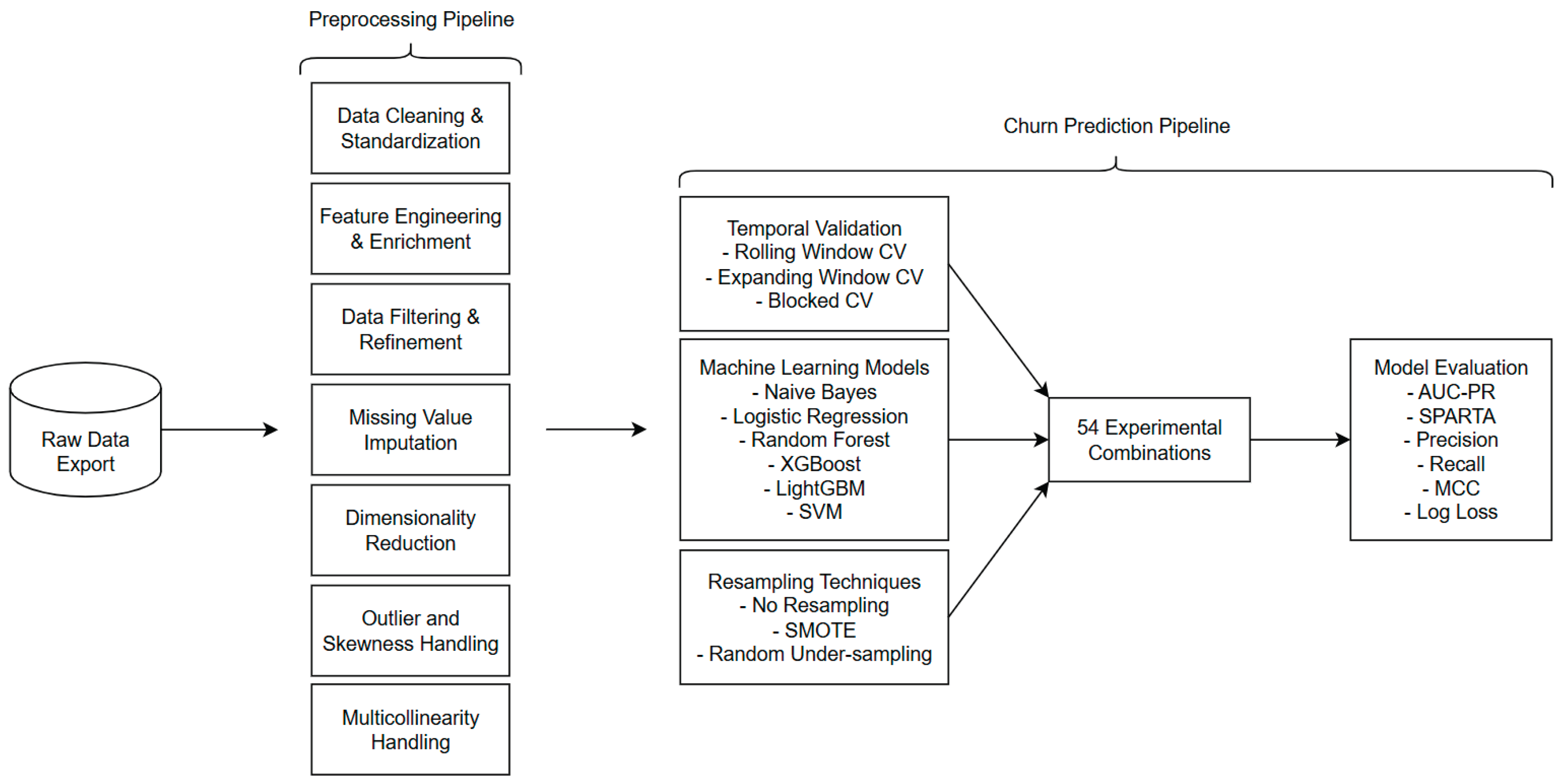

The raw data extracted from S.P. AbonneeService’s systems undergoes an extensive automated preprocessing pipeline to ensure data quality, consistency, and suitability for the full churn prediction pipeline. This pipeline is designed to be robust across diverse publisher datasets and prioritizes the creation of interpretable features. The sequence of operations is carefully structured: initial standardization and cleaning prepare the data for reliable feature engineering, which is then followed by refinement, missing value imputation, and advanced numerical processing to optimize the dataset for machine learning algorithms.

2.2.1. Initial Data Cleaning and Standardization

The first stage focuses on foundational data integrity. All raw data fields are subjected to type conversion: date-like strings are parsed into standardized datetime objects; numeric fields, including those representing currency with associated symbols and locale-specific decimal separators, are converted to numerical types; boolean-like text (e.g., “Ja”/“Nee”, which is Dutch for “Yes”/“No”) is mapped to true boolean values; and fields intended as categorical are defined as categorical variables, with common string representations of missingness (e.g., “nan”, “none”, empty strings) unified to a standard null representation. For instance, gender indicators are transformed to a consistent case. Any remaining columns not explicitly typed are converted to a string format. A minimal rule-based normalization, driven by configurable patterns, is then applied to specific fields to rectify common inconsistencies, although current configurations apply this sparingly. This initial standardization is crucial as it ensures that all subsequent operations act upon data of expected and consistent types, preventing errors and improving the reliability of derived features.

2.2.2. Feature Engineering and Enrichment

Following initial cleaning, several feature engineering steps are undertaken to create new, more informative variables.

First, a set of binary indicators is generated from existing data characteristics. For example, the presence of contact information, such as an email address or phone number, or the use of specific payment methods, such as direct debit, is converted into boolean flags. This binarization enhances model interpretability by creating explicit signals for key customer attributes, thereby improving the model's clarity and transparency.

Second, more complex derived features are created to capture crucial aspects of subscriber behavior and lifecycle. Subscriber birth dates are transformed into age categories; this categorization can be static or adaptive to the data distribution, based on pipeline configuration, to ensure meaningful group sizes. Additionally, behavioral patterns such as serial churn tendencies are identified by analyzing historical subscription patterns. The specific criteria for flagging a customer as a serial churner, namely an average subscription duration of less than one year, more than two cancelled subscriptions, and more than three total subscriptions, were established based on industry experience and the recommendation of S.P. AbonneeService's CTO, Marc Dierikx [

15]. A significant step involves calculating churn indicators: a binary churn event flag is determined based on subscription end dates and renewal statuses, and a corresponding time-to-event (or time-to-censoring for active subscriptions) is computed relative to a defined study end date, which can be utilized for future survival analysis. This provides the target variable and temporal context for the churn model. Summaries of customer interactions, including the total number of service issues or issues per year (calculated using Bayesian smoothing and percentile capping to handle variance and outliers), are also generated.

Third, composite scores are engineered by combining several binarized features with predefined weights. These scores aim to quantify abstract concepts, including customer reachability (based on available contact channels and permissions), engagement (based on communication opt-ins), business customer profile strength (based on the provision of business-specific details, such as VAT numbers), and payment reliability (based on payment method and reminder history). The specific features included in these composite scores and their respective weights were determined in consultation with Marc Dierikx [

15] to reflect business understanding and their relative importance. These engineered features provide higher-level abstractions that can be more directly interpretable and predictive.

2.2.3. Data Filtering and Refinement

To focus the analysis on relevant customer segments, specific data filtering rules are applied. Rows corresponding to non-actionable subscription types or particular business-to-business intermediary accounts, as defined in the configuration based on criteria provided by Marc Dierikx [

15], are removed. Additionally, scenarios where the financial payer is a distinct entity from the subscription recipient are filtered out to simplify the modeling scope, focusing on direct subscriber relationships. This step ensures the model is trained on a dataset representative of the target population for retention efforts.

2.2.4. Missing Value Imputation

The pipeline then addresses missing data through a multi-faceted imputation strategy. The placement of this comprehensive imputation stage within the pipeline is a considered choice. Initial data cleaning and type conversion (

Section 2.2.1) standardize various raw representations of missingness to null values. Early feature engineering steps, particularly binarization (

Section 2.2.2), often rely on the distinction between present and absent data, thus implicitly using the original missingness context (e.g., a customer either has a listed phone number or not). However, the creation of other derived features, such as calculating age from birth dates, can introduce new missing values if the source data is incomplete. Therefore, the main imputation phase is strategically positioned after these initial feature creation steps but critically before the advanced numerical processing stages (

Section 2.2.6), such as skewness correction and outlier treatment, and subsequent model training. These later stages generally require complete, non-null datasets to function correctly and produce reliable results. This ordering ensures that as much information as possible is derived while preserving the original missingness context where beneficial, before filling gaps to prepare for numerically intensive algorithms.

For geographical information, missing province data for subscribers is imputed using a hierarchical approach. First, suppose the subscriber's country code indicates a non-domestic location, a distinct "Foreign_[CountryCode]" category is assigned. In this case, the reason is that province-level data is not consistently recorded for international subscribers, and the relatively low volume of such subscribers makes detailed imputation impractical and less reliable. For domestic (Dutch) addresses with missing provinces, the system attempts to infer the province by first looking up the most common province associated with the subscriber's listed city or place name from non-missing records. If this fails, it then attempts to infer the province based on the most common province associated with the initial digits of their postal code. Any remaining domestic addresses with unidentifiable provinces are assigned an "Unknown_NL" category, while truly unclassifiable cases default to a general "Unknown" province.

Beyond these targeted imputations, a general configurable strategy handles remaining missing values. Depending on the configuration (e.g., AUTOFILL_MISSING), missing numerical data may be filled with zero, booleans with false, and categoricals with a distinct “Unknown” category. Specific columns, such as counts of items sent or paid, may have custom default fill values (e.g., 1). The critical subscription cancellation date is explicitly preserved as missing if KEEP_OPZEGDATUM is enabled, which will mainly be used for auditing purposes in later steps.

2.2.5. Dimensionality Reduction and Noise Management

To manage data sparsity and reduce noise from less frequent categories, frequency-based grouping is applied to selected categorical features (e.g., acquisition or campaign codes). Categories that fall below a minimum frequency threshold and collectively represent less than a specified percentage of the dataset are consolidated into a generic “Other” category.

Irrelevant data sections (identified by column name prefixes) and explicitly listed redundant columns are then removed. Subsequently, features exhibiting low variance are identified and removed. This includes columns with constant values or, if REMOVE_NEAR_UNIFORMITY is enabled, near-constant values, where uniformity is assessed dynamically based on the majority class proportion for categorical and boolean data, and the coefficient of variation for numerical data, scaled according to the dataset size. Auditing variables, key identifiers, and churn-related target variables are exempt from this removal.

Finally, a configurable step allows for the removal of any rows that still contain missing values after all imputation and feature engineering steps, ensuring a complete dataset for modeling. The option to retain records where only the cancellation date is missing is available, as it serves as an auditing variable.

2.2.6. Advanced Numerical Feature Processing

Numerical features undergo a dedicated three-stage processing sequence:

Semantic Categorization: Numerical features are automatically categorized into types such as monetary, count, ratio (bounded 0-1), or unbounded ratio/usage metric. This categorization leverages statistical properties (distribution, presence of negatives, zero-inflation, skewness, kurtosis, coefficient of variation, decimal precision). It can be guided by manually defined categories for specific known features (e.g., financial transaction amounts are 'monetary').

Skewness Correction: Based on the assigned category and observed skewness (magnitude and direction), appropriate transformations are applied. For instance, monetary data often benefits from log or Yeo-Johnson transforms, count data from square root or Freeman-Tukey, and bounded ratio data from arcsine or logit transforms [

34,

35]. The pipeline iteratively tries a sequence of suitable transformations, selecting the one that most effectively normalizes the distribution or reduces skew, validated by statistical testing.

Outlier Treatment: Outliers are detected using methods such as Isolation Forest through the pyod library, with detection thresholds dynamically adjusted based on feature category and whether the feature was previously transformed [

32,

33]. Detected outliers are then handled in a category-specific manner; for example, monetary outliers might be winsorized adaptively based on skewness, while count outliers might be capped at a high percentile of non-zero values.

This structured approach to numerical processing ensures that transformations and outlier handling are contextually appropriate, enhancing model performance and stability.

2.2.7. Multicollinearity Management

As a final step, multicollinearity is addressed to improve model interpretability and stability. Highly correlated numerical features (above a configurable Spearman correlation threshold, e.g., 0.7) are grouped. Within each group, the feature with the highest Information Value (IV) related to the churn target is retained, while the others are removed. Features with very low IV (e.g., < 0.02) are also considered for removal. Auditing identifiers and target variables are protected from this process. This ensures that the final feature set is both predictive and less redundant.

The overall order of these preprocessing steps is critical: initial cleaning enables reliable feature engineering; derived features then undergo imputation and refinement; and numerical processing is performed last on a complete and well-defined set of numerical inputs, followed by multicollinearity reduction on the finalized feature set.

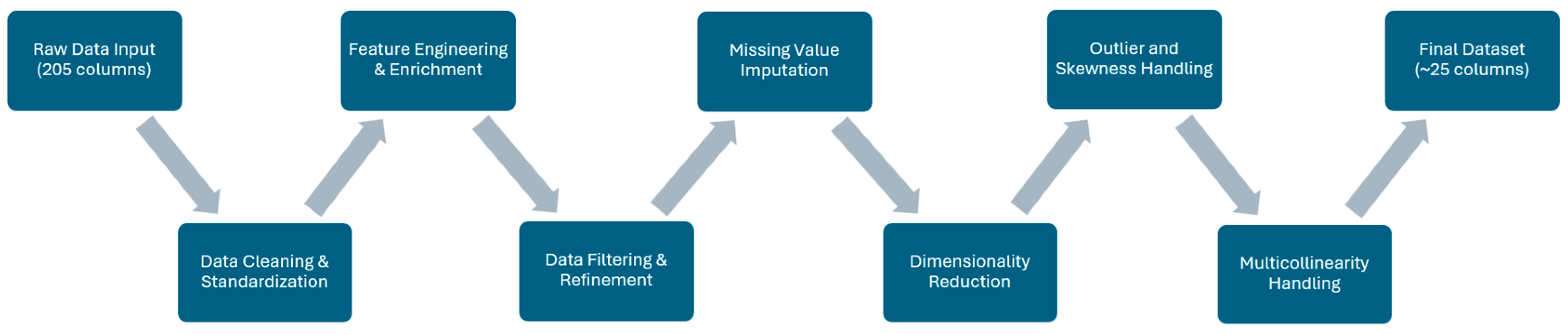

Figure 2 illustrates the complete automated preprocessing pipeline described in the preceding sections, demonstrating the systematic transformation from raw database exports containing 205 columns to a refined dataset of approximately 25 predictive features. The flowchart shows the sequential progression through data cleaning and standardization, feature engineering and enrichment (including composite score creation and behavioral pattern identification), data filtering and refinement for actionable customer segments, missing value imputation including hierarchical geographical approaches, dimensionality reduction through frequency-based categorical grouping, advanced numerical processing with semantic categorization and skewness correction, outlier treatment using Isolation Forest, and multicollinearity management through Information Value-based feature selection. This systematic approach ensures consistent processing across heterogeneous publisher datasets while maintaining feature interpretability essential for business stakeholder understanding.

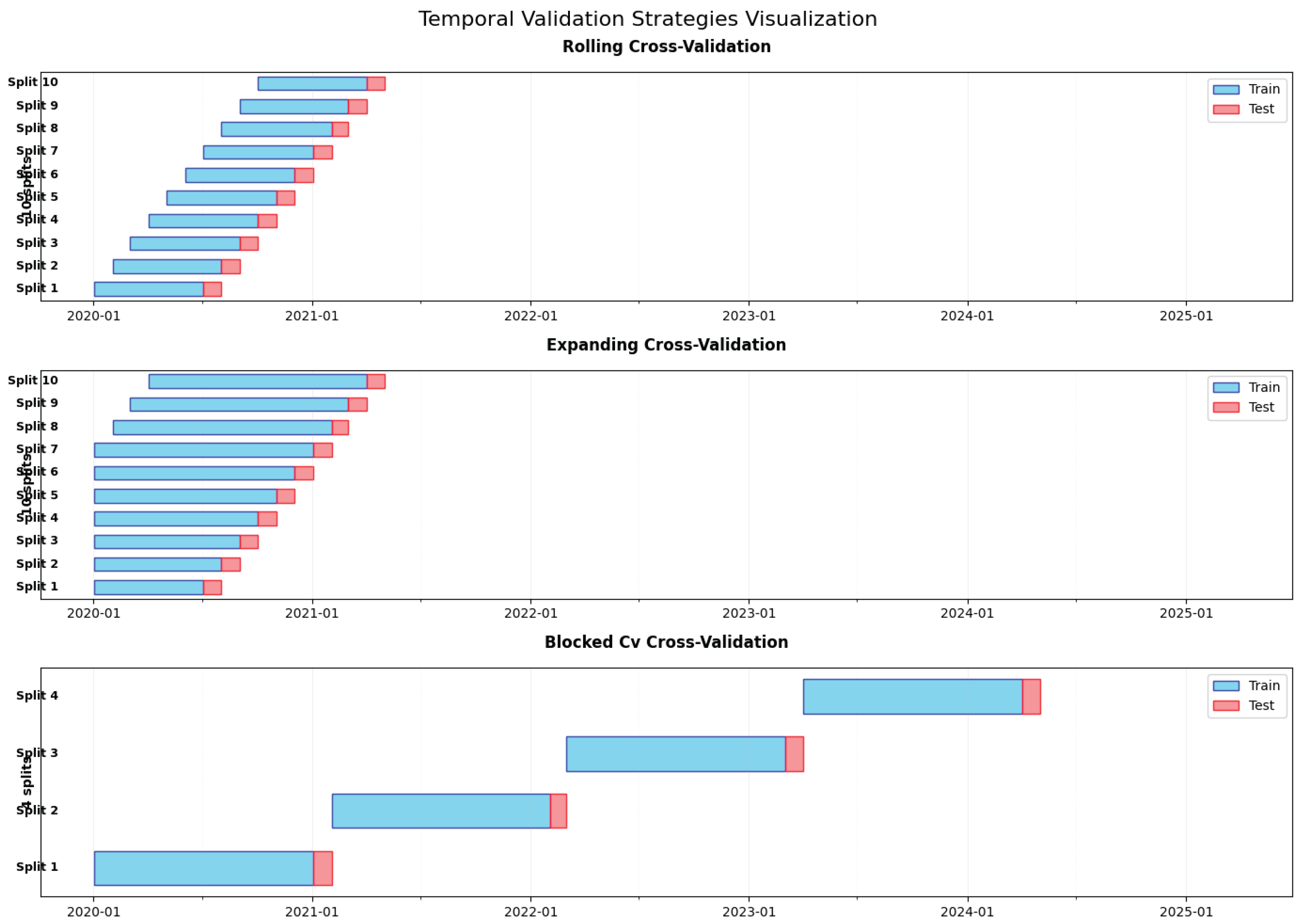

2.3. Temporal Validation Strategies

To evaluate model performance on time-ordered subscription data and ensure that predictions are validated against future, unseen periods, this study implements several temporal cross-validation strategies. A fundamental requirement for modeling time-dependent phenomena, such as customer churn, is the strict prevention of data leakage, where information from future periods may inadvertently influence model training. All employed validation strategies are derived from a common base class named TemporalSplitter. This architectural choice ensures consistency across methods, mandating, for example, a minimum number of samples to guarantee sufficient data within each validation split and operating on data that is pre-sorted by a primary temporal column (the subscription entry date). The TemporalSplitter framework generates training and testing indices based on key date columns, relative to a dynamically determined "snapshot date" for each validation split. The key date columns used are the subscription entry date and the subscription cancellation date.

A crucial consideration in churn prediction, which is addressed by these temporal validation methods, is that the same customer entities can legitimately appear in both the training and test sets of a given split. The distinction lies in the temporal scope of the information used: the training set captures historical behavior and status up to the snapshot date, while the test set evaluates the model's ability to predict outcomes (i.e., churn events) for these same customers in a period strictly after this snapshot date. The target variable in the test set is thus always chronologically after any information used for training, appropriately simulating a real-world deployment scenario where a model, trained on past data, predicts future churn.

2.3.1. Rolling Window Cross-Validation

The Rolling Window Cross-Validation strategy is designed to assess model performance on dynamically changing data patterns, reflecting environments where recent data may be more indicative of future behavior. This method follows the principle of training on a fixed-duration window of past data and testing on the immediately subsequent period.

The process for generating splits can be conceptualized as follows:

Let be the dataset sorted chronologically by the subscription entry date.

Let be the earliest subscription entry date in .

Let be the duration of the training window.

Let be the duration by which the window slides forward (step size), which also typically defines the prediction horizon for the test set.

Let be the total number of splits generated.

For each split :

The snapshot date,

, is defined as:

The training period for the split encompasses data from .

The testing period for the split encompasses data from .

Customer data included for training in the split consists of subscriptions that meet two criteria: (1) their entry date is before , and (2) they are known to be active at some point during or after the training window starts. More specifically, they either remain active at the snapshot date (no churn date recorded) or churned at any time on or after . The model is then evaluated on its ability to predict churn for these same customers during the testing period, , excluding those who had already churned before .

For the Rolling Window Cross-Validation implementation, the training window duration months with a step size month. This configuration ensures that each model iteration trains on a consistent 6-month historical period, advancing the temporal window by one-month intervals, and provides overlapping validation periods that capture gradual shifts in customer behavior patterns. The temporal column specification utilizes the subscription entry date as the primary ordering criterion, with churn events identified through the subscription cancellation date.

The rationale for the Rolling Window approach lies in its suitability for environments where customer behavior may evolve rapidly. By consistently training on a fixed-length recent history, this strategy tests the model's adaptability to emerging trends and its performance on the most current behavioral patterns. It simulates a deployment scenario where models are periodically retrained using only a recent, limited segment of historical data, prioritizing recency over the sheer volume of historical information. The implementation ensures that each split contains a sufficient number of samples for both training and testing to be statistically meaningful.

2.3.2. Expanding Window Cross-Validation

The Expanding Window Cross-Validation strategy is employed to evaluate models that may benefit from a progressively larger historical context, under the assumption that more data generally leads to better model generalization.

The split generation process is as follows:

Let , , and be defined as in the Rolling Window method.

Let be the duration of the initial training window.

Let be an optional maximum duration for the training window. If not set, the window expands indefinitely from .

For each split :

The snapshot date,

, is defined as:

The start of the training period for the split

,

, is:

The training period for split i is .

The testing period for split i is .

Similar to the rolling window, training data for the split includes subscriptions active or churned within its training window, having started before . Testing evaluates predictions for these customers in the subsequent testing period, excluding those who have already churned.

The Expanding Window Cross-Validation implementation employs an initial window size months, expanding by month increments with a maximum window duration months. This parameter set enables models to progressively incorporate additional historical context while minimizing excessive computational overhead and mitigating potential bias from outdated behavioral patterns. The expanding approach captures the cumulative learning benefit of increased training data while maintaining temporal relevance through the 12-month maximum window constraint. Just like the Rolling Window approach, temporal ordering is based on the subscription entry date, and churn identification is done through the subscription cancellation date.

This strategy is particularly beneficial when long-term historical patterns and seasonality are considered essential for accurate churn prediction. The optional maximum window duration provides a practical balance, allowing the model to leverage extensive history while mitigating the risks of outdated patterns biasing the model or leading to excessive computational load. As before, the system also ensures each split meets a minimum sample requirement.

2.3.3. Blocked Cross-Validation

The Blocked Cross-Validation method offers a stringent test of a model's generalization capability across distinct, temporally distant periods by dividing the dataset into non-overlapping segments. This strategy is beneficial for assessing long-term model stability.

The formation of blocks is defined as:

Let and be defined as previously.

Let be the desired number of train-test blocks.

Let be the duration of the training period within each block.

Let be the duration of the testing period within each block.

Let be an optional duration of a gap period between the training and testing periods within each block (defaulting to zero if not specified).

For each block :

Note: We use superscript notation (k) to index blocks while subscripts denote variable types.

The start of the block

,

, is:

The training period for the block is .

The snapshot date for the block is .

The testing period for the block is .

Customer inclusion logic remains consistent: training utilizes subscriptions known up to (active or churned within the training period of the block ), and testing assesses predictions for these customers during the block's testing period, after accounting for any churns before the test period begins.

The Blocked Cross-Validation implementation utilizes non-overlapping temporal blocks with training periods months and testing periods month, generating independent validation blocks with no temporal gap (). This configuration provides a stringent evaluation of model generalization across distinct temporal periods while ensuring sufficient training data within each block. The 12:1 month train-test ratio balances comprehensive model training with focused prediction evaluation over meaningful prediction horizons. Again, just like the Rolling Window and Expanding Window approaches, temporal ordering is based on the subscription entry date, and churn identification is done through the subscription cancellation date.

The primary rationale for Blocked Cross-Validation is its ability to assess model stability and robustness when faced with potentially different underlying data distributions or significant shifts in customer behavior that may occur over extended periods. The optional gap period further ensures the independence of the test set by preventing leakage from events near the train-test boundary. The total number of blocks generated may be adjusted if the dataset's temporal span is insufficient to form the requested number of blocks of the specified durations, while still respecting minimum sample size constraints for each split. This method differs from the previous two in that it does not necessarily utilize overlapping data between the training sets of consecutive blocks, thereby providing a more challenging validation scenario.

Figure 3 summarizes the three temporal validation approaches employed in this study, illustrating the key differences in training window management, temporal boundary handling, and split generation strategies discussed above. The visualization illustrates how each method offers distinct advantages for model evaluation: rolling window approaches prioritize recent behavioral patterns, expanding window methods leverage cumulative historical information, and blocked cross-validation ensures the assessment of generalization across non-overlapping periods.

2.4. Temporally-Aware Feature Engineering and Preprocessing

This section describes the systematic transformation of raw input features into a numerical format suitable for machine learning algorithms. Unlike the data preprocessing described in

Section 2.2, which focuses on cleaning raw database exports and creating business-relevant derived features, this feature engineering process operates on already-cleaned features and is executed within each temporal validation fold to ensure temporal integrity, particularly relevant for time-dependent features. While the earlier preprocessing establishes data quality and consistency across the entire dataset, this stage ensures that temporal boundaries are respected and that features are optimally formatted for machine learning algorithms.

The ChurnFeatureEngineer component manages this pipeline, which consists of two main stages: temporally aware feature creation, followed by general feature preprocessing. The sequential execution of these stages is critical for maintaining temporal validity while maximizing the predictive value of derived features.

2.4.1. Temporally-Aware Feature Creation

The temporal feature engineering process addresses a fundamental challenge in time-series prediction: ensuring that feature calculations reflect only information available at the time of prediction while capturing meaningful temporal patterns. The TemporalFeatureEncoder component implements this through dynamic feature generation, which adapts to the temporal boundaries of each training fold.

Time-dependent features, such as recency metrics, are dynamically generated for each training fold. These calculations are performed relative to the training end-date of that specific training fold, preventing data leakage by ensuring that only information available up to that point is used. This approach differs from static feature engineering approaches, which may incorporate future information, thereby compromising the temporal validity of the prediction model and introducing data leakage.

For specified datetime columns (e.g., the insertion and starting date of a subscription), features are created representing the time elapsed between the event date in the column and the end date of the current fold. These features, listed as [column]_days_since, provide the model with critical recency information that captures the temporal distance between customer actions and the prediction point. The calculation methodology ensures that recent customer activities receive an appropriately weighted temporal representation while maintaining consistency across different training folds.

Standard date components are extracted from datetime columns to capture potential seasonalities and cyclical patterns inherent in subscription-based business models. These include the month, day of the week, quarter, and a binary flag indicating if the date falls on a weekend. The extraction of these cyclical components enables the model to learn temporal patterns that may influence customer behavior, such as seasonal subscription preferences or day-of-week effects on customer engagement.

The original datetime columns are removed after these temporal features are generated, ensuring that the subsequent processing pipeline operates exclusively on numerical representations while preserving all temporal information in a format that is algorithmically accessible.

2.4.2. General Feature Preprocessing

Following the creation of temporal features, the complete feature set undergoes standardized preprocessing to ensure optimal compatibility with machine learning algorithms. This stage is implemented through a ColumnTransformer pipeline from scikit-learn that applies appropriate transformations based on pre-identified column types [

16].

Numeric types

All features identified as numeric, including the newly created temporal features and any original numeric features, are standardized using the StandardScaler from scikit-learn [

17]. This transformation scales features to have zero mean and unit variance, which is beneficial for many machine learning algorithms that are sensitive to feature scale differences. Standardization is critical, given the diverse scales inherent in the temporal features (e.g., [column]_days_since values ranging from 0 to several thousand) and the original dataset's numerical variables.

Categorical types

Features identified as categorical are converted into a numerical format using OneHotEncoder [

18]. This process creates binary (0/1) columns for each unique category present in the feature, with the optional removal of the first category's column to prevent perfect multicollinearity. Perfect multicollinearity occurs when categorical columns become linearly dependent, which can lead to numerical instability in certain machine learning algorithms. The encoder is configured with handling unknown categories, ensuring that new categories appearing in test data that were not observed in the training data are represented by zeros across all one-hot encoded columns, thereby preventing pipeline failures while maintaining long-term model stability.

Boolean types

Features already in boolean (0/1) format are passed through without further transformation, maintaining their interpretability while ensuring compatibility with the numerical output format required by the machine learning algorithms.

The ChurnFeatureEngineer pipeline, after completing both temporal feature creation and general preprocessing stages, outputs a purely numerical NumPy array of features ready for model training. The pipeline maintains feature name, enabling interpretability analysis and feature importance evaluation in subsequent modeling stages. This numerical array format ensures integration with the temporal validation framework and resampling techniques in the churn prediction pipeline.

2.5. Machine Learning Model Selection

To address the complex challenge of churn prediction across heterogeneous publisher datasets, this study implements a comprehensive collection of machine learning algorithms, each selected to provide distinct analytical perspectives on customer behavior patterns and use cases. The model selection strategy prioritizes the balance between predictive performance and interpretability requirements, ensuring that generated predictions can be translated into actionable retention strategies.

The chosen algorithms represent a wide range of fundamental machine learning algorithms, including linear methods for baseline performance and interpretability, probabilistic approaches for uncertainty quantification, ensemble techniques for robust feature interaction modeling, gradient boosting for high-performance non-linear pattern detection, and kernel methods for complex decision boundary modeling. Each algorithm addresses specific aspects of the churn prediction challenge, such as feature interaction complexity, while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for deployment.

All models incorporate explicit class imbalance handling mechanisms, recognizing that churn prediction inherently involves imbalanced datasets where active customers significantly outnumber those who churn. This differs from the resampling techniques described in section 2.6, as these model-level approaches adjust the algorithms' internal behavior during training (such as loss function weighting and splitting criteria) rather than modifying the training dataset distribution itself. These algorithmic adjustments complement potential resampling strategies by ensuring that minority class patterns receive appropriate attention regardless of the data distribution provided to the model. The parameter selection strategy emphasizes ranges that strike a balance between computational efficiency and predictive performance, enabling comprehensive hyperparameter optimization while maintaining practical deployment constraints.

2.5.1. Probabilistic Baseline Model: Naive Bayes

The Gaussian Naive Bayes classifier provides a probabilistic baseline that assumes feature independence while maintaining computational efficiency and strong theoretical foundations. This model serves as a reference point for comparing more sophisticated approaches mentioned later on, offering insights into the predictive value achievable under simplified distributional assumptions. The implementation utilizes the GaussianNB classifier from scikit-learn [

19].

The Naive Bayes classifier estimates churn probability through Bayes' theorem combined with the independence assumption:

Under the Gaussian assumption and feature independence, the likelihood term becomes:

where

and

represent the mean and variance of the feature

for class

, estimated from the training data.

Despite its simplifying assumptions, Naive Bayes often performs surprisingly well in practice, particularly when the independence assumption is approximately satisfied or when the decision boundary can be effectively approximated by the multiplicative probability model [

9]. The algorithm's efficiency and probabilistic output make it valuable for establishing baseline performance expectations and providing interpretable probability estimates for business stakeholders.

The model requires no hyperparameter tuning, focusing evaluation on the fundamental predictive signal available in the feature set under simplified assumptions. This characteristic makes it particularly valuable for assessing whether more complex models provide meaningful improvements over basic probabilistic modeling.

2.5.2. Linear Baseline Model: Logistic Regression

Logistic regression serves as the primary linear baseline for churn prediction, providing interpretable coefficients that directly quantify the relationship between customer characteristics and the probability of churn. This algorithm addresses the binary classification nature of churn prediction by utilizing the logistic function, ensuring bounded probability outputs while maintaining linear interpretability in the log-odds space. The implementation uses the LogisticRegression class from scikit-learn [

20].

The logistic regression model estimates the probability of churn for a customer

as:

where

represents the feature vector for the customer

,

is the intercept term, and

represents the coefficient for the feature

. The linear combination

represents the log odds of churn, enabling the direct interpretation of feature effects on churn probability.

The implementation utilizes the SAGA (Stochastic Average Gradient Augmented) solver, which provides computational efficiency for large datasets while supporting both L1 and L2 regularization [

20]. The regularization term prevents overfitting through penalized likelihood maximization:

where

controls regularization strength (inverse of the C parameter), and

determines the penalty type (1 for L1, 2 for L2). The balanced class weighting approach automatically adjusts for class imbalance by weighting the loss function inversely proportional to class frequencies, ensuring that the minority class (churned customers) receives appropriate attention during model training.

The hyperparameter space utilizes regularization strengths of 1 and 10, encompassing strong to moderate regularization scenarios, while maintaining computational efficiency through the SAGA solver's advanced optimization algorithms. This configuration provides a robust linear baseline that serves as both a standalone predictor and a benchmark for evaluating the added value of more complex non-linear approaches.

2.5.3. Ensemble Method: Random Forest

Random Forest addresses the variance and overfitting limitations of individual decision trees through ensemble averaging, while providing built-in feature importance measures that enhance model interpretability. This algorithm combines bootstrap aggregating (bagging) with random feature selection to create diverse decision trees that collectively provide robust predictions. The implementation utilizes the RandomForestClassifier from scikit-learn [

21].

Each tree

in the forest is trained on a bootstrap sample of the training data, with each split considering only a random subset of features. The final prediction combines individual tree predictions:

where

represents the number of trees and

represents the probability estimate from the tree

.

The algorithm's built-in feature importance calculation provides valuable insights for business understanding:

where

represents the proportion of samples reaching the node

,

measures the impurity decrease at the node

,

indicates the feature used for splitting at the node

, and

is an indicator function for a feature

.

The hyperparameter configuration balances ensemble size with computational efficiency, utilizing 100 or 300 estimators to ensure prediction stability while maintaining reasonable training times. The maximum depth constraint (10 levels or unlimited) controls individual tree complexity, preventing excessive overfitting while allowing sufficient model flexibility. Balanced class weighting ensures appropriate handling of class imbalance by adjusting the impurity criteria to account for unequal class frequencies.

Random Forest's resistance to overfitting, natural handling of mixed data types, and interpretable feature importance measures make it particularly suitable for the heterogeneous data environment of the case company.

2.5.4. Extreme Gradient Boosting: XGBoost

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) represents an advanced implementation of the gradient boosting framework, incorporating regularization techniques and optimized tree construction. The implementation utilizes the XGBClassifier from the xgboost library [

22]. The algorithm uses iterative ensemble construction, where each new model corrects the errors of the previous ensemble through additive modeling:

where

represents the ensemble after

iterations,

is the new weak learner, and

is the step size determined through optimization.

For binary classification, XGBoost optimizes an objective function combining logistic loss with explicit regularization:

where the regularization term

penalizes model complexity through L1 and L2 penalties on leaf weights, with

representing the number of leaves and

denoting leaf weights.

XGBoost employs level-wise tree construction, building balanced trees breadth-first while incorporating advanced pruning strategies. Class imbalance handling utilizes scikit-learn's compute_sample_weight function with balanced weighting, maintaining consistency with other algorithms' class_weight='balanced' approach by automatically adjusting sample importance based on class frequencies [

36].

The hyperparameter space utilizes a learning rate of 0.1, tree depth constraints set at 6 and 10 levels, and subsampling parameters of 0.8 for computational efficiency. GPU acceleration (if available) will enhance performance for large-scale datasets, making XGBoost particularly effective for capturing complex feature interactions.

2.5.5. Light Gradient Boosting: LightGBM

LightGBM (Light Gradient Boosting Machine) implements an optimized gradient boosting framework prioritizing computational efficiency while maintaining predictive performance. The implementation utilizes the LGBMClassifier from the lightgbm library [

23]. The algorithm shares the fundamental additive modeling approach described in section 2.5.4. Gradient Boosting Method: XG but employs distinct tree construction strategies for enhanced efficiency.

The key innovation lies in leaf-wise tree growth, selecting the leaf yielding maximum loss reduction rather than expanding all nodes at the same depth:

This strategy typically produces more asymmetric but deeper trees, achieving better accuracy with fewer nodes and improved computational efficiency.

LightGBM incorporates Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) and Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB) optimization techniques [

29]. GOSS reduces computational complexity by retaining high-gradient samples while randomly sampling low-gradient samples, compensating for sampling bias through adjusted gradient calculations. EFB bundles mutually exclusive sparse features, significantly reducing memory usage without substantial information loss.

Unlike XGBoost's scale_pos_weight approach, LightGBM addresses class imbalance through balanced class weighting, which modifies splitting criteria gain calculations proportionally to the inverse class frequencies, ensuring the appropriate consideration of minority class patterns during tree construction.

The implementation utilizes identical parameter ranges to XGBoost for direct performance comparison while leveraging computational advantages through GPU acceleration and advanced memory optimization.

2.5.6. Kernel Method: Support Vector Machine

The Support Vector Machine (SVM) offers sophisticated decision boundary modeling through kernel transformations, allowing for the detection of complex, non-linear patterns while maintaining a theoretical foundation in statistical learning theory. The implementation employs the SVC class from scikit-learn [

24]. The algorithm constructs optimally separating hyperplanes by maximizing the margin between classes in the transformed feature space.

The SVM optimization problem seeks to minimize:

Subject to:

where

represents the kernel transformation,

is the weight vector,

is the bias term,

are slack variables, and

controls the regularization strength.

The dual formulation enables kernel-based transformations:

where

are Lagrange multipliers and

represents the kernel function.

The implementation includes the radial basis function (RBF) kernel. The RBF kernel:

Enables complex non-linear boundary modeling through Gaussian similarity measures.

The balanced class weighting approach adjusts the penalty parameter

for each class proportionally to the inverse of class frequencies, ensuring appropriate attention to minority class samples during optimization. The probability estimation requirement enables integration with the ensemble evaluation framework through Platt scaling, which fits a sigmoid function to the SVM decision values [

24].

Hyperparameter optimization focuses on the regularization strength (values 1 and 10) to balance between margin maximization and training error minimization, while the gamma parameter utilizes the 'scale' setting for automatic adjustment based on feature dimensionality.

The SVM approach provides sophisticated pattern recognition capabilities, particularly valuable for detecting subtle customer behavior patterns that may indicate churn risk, complementing the ensemble of algorithms through its unique approach to classification boundary optimization.

2.5.7. Minimal Hyperparameter Optimization Strategy

The hyperparameter optimization strategy employed in this study prioritizes computational efficiency while maintaining systematic exploration of parameters across the diverse model ensemble. The approach utilizes a minimal grid search methodology that strikes a balance between thorough parameter evaluation and practical deployment constraints, which are essential for multi-client B2B environments.

The optimization framework systematically evaluates all parameter combinations defined in the model configurations through the Cartesian product expansion of specified parameter options. This approach generates parameter grids that cover a range of parameters while ensuring computational tractability for operational deployment.

The optimization process employs a simple train/validation split methodology, partitioning the training data into 80% for parameter optimization training and 20% for validation assessment. This approach prioritizes speed over exhaustive validation, avoiding computationally expensive cross-validation procedures that would significantly impact deployment feasibility across multiple client datasets.

Parameter selection utilizes AUC-PR (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve) as the primary optimization metric, which is particularly appropriate for imbalanced churn prediction scenarios, as it focuses on the minority class performance and provides a robust evaluation regardless of class distribution [

27]. The optimization algorithm iterates through all parameter combinations, training models on the optimization subset and evaluating performance on the validation subset, retaining the parameter configuration that achieves maximum AUC-PR performance.

Hyperparameter optimization is executed within each temporal training fold to ensure that parameter selection respects chronological boundaries and reflects only information available at the time of prediction, thereby preventing data leakage while maintaining consistency across temporal evaluation periods.

2.5.8. Model Integration and Ensemble Strategy

The comprehensive model selection strategy ensures robust churn prediction through algorithmic diversity while maintaining interpretability requirements for business implementation. Each algorithm contributes distinct analytical perspectives: probabilistic approaches establish the baseline for comparing model performance under simplified assumptions, linear methods provide interpretable coefficients and transparent decision boundaries, ensemble methods deliver robust feature interaction modeling, gradient boosting captures complex non-linear patterns, and kernel methods enable sophisticated boundary optimization.

The hyperparameter optimization strategy complements this algorithmic diversity through systematic parameter exploration that balances computational efficiency with performance maximization. The minimal grid search approach enables comprehensive evaluation of various parameter combinations while maintaining practical deployment constraints. The optimization process operates within each temporal training fold, ensuring that parameter selection reflects only information available at the time of prediction while maintaining consistency across temporal evaluation periods.

The integration of model-level class imbalance handling with systematic hyperparameter optimization ensures consistent performance across diverse customer distributions encountered within the heterogeneous publisher portfolio. These model-level approaches adjust algorithms' internal behavior during training through loss function weighting and splitting criteria modifications, complementing potential resampling strategies described in section 2.6.

This integrated approach to model selection and hyperparameter optimization provides comprehensive coverage of machine learning paradigms while maintaining practical deployment constraints, ensuring that the resulting churn prediction system can deliver accurate, interpretable, and actionable insights across a heterogeneous publisher portfolio.

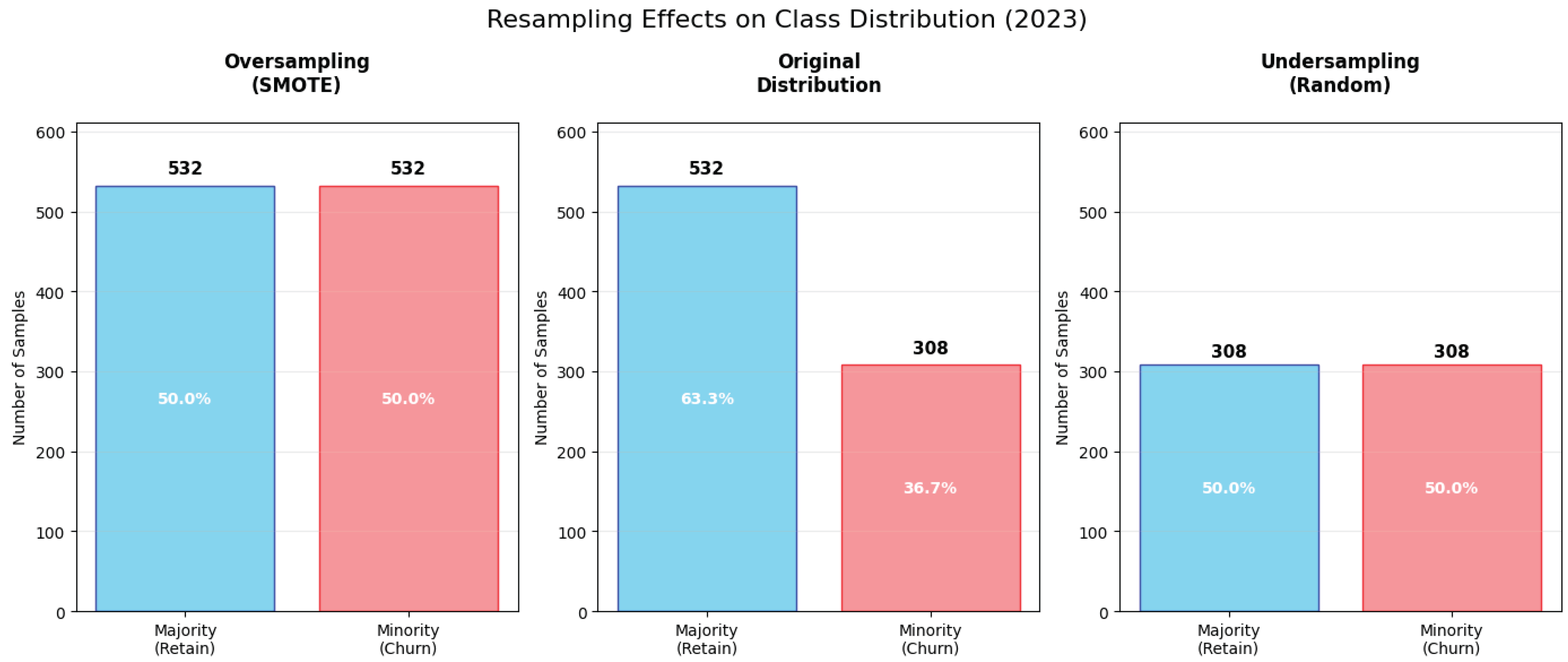

2.6. Resampling Techniques

Class imbalance represents a fundamental challenge in churn prediction, where the distribution of active versus churned customers typically exhibits significant skew toward the majority class. This imbalance can substantially impact model performance, as standard machine learning algorithms tend to optimize for overall accuracy rather than detecting minority classes, resulting in models that achieve high accuracy scores while failing to identify customers at risk of churning. To address this critical limitation, this study implements a comprehensive evaluation of resampling techniques that systematically modify the training data distribution to improve minority class recognition without compromising the temporal integrity of the validation framework.

The resampling strategy encompasses three distinct approaches: a baseline configuration that maintains original class distributions, synthetic oversampling that generates minority class examples, and undersampling that reduces majority class representation. Each technique addresses different aspects of the class imbalance challenge while maintaining compatibility with the temporal validation framework described in

Section 2.3. The implementation utilizes the imbalanced-learn library, which provides specialized tools for handling imbalanced datasets while ensuring seamless integration with scikit-learn pipelines and temporal cross-validation procedures [

30].

Critically, all resampling operations are applied exclusively to training data within each temporal fold, ensuring that test data maintains its original distribution to provide a realistic performance evaluation. This approach prevents data leakage while enabling fair comparison of resampling effectiveness across different temporal periods and varying degrees of class imbalance inherent in a heterogeneous publisher portfolio.

2.6.1. No Resampling Baseline

The no-resampling configuration serves as a baseline for evaluating the impact of data manipulation techniques on model performance. This approach maintains the original class distribution present in the training data, providing insight into the natural predictive signal available without the need for synthetic data generation or sample removal. The implementation utilizes a custom NoResampling class that includes compatibility with imbalanced-learn pipelines while returning the input data unchanged.

The baseline approach is particularly valuable for understanding the trade-offs between prediction accuracy and class balance, as it reveals whether resampling techniques provide genuine predictive improvements or merely redistribute prediction errors across classes.

2.6.2. Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique (SMOTE)

SMOTE addresses class imbalance through intelligent synthetic sample generation that preserves the underlying data structure while expanding the representation of the minority class. The technique operates by identifying instances of the minority class and generating synthetic samples along the line segments connecting these instances to their k-nearest neighbors in the feature space. The implementation utilizes the SMOTE class from imbalanced-learn [

25].

The synthetic sample generation process can be formally described as follows. For each minority class sample

SMOTE identifies its k nearest minority class neighbors, denoted as

. A synthetic sample

is then generated by:

where

is a randomly selected neighbor from

and

is a random number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1:

. This interpolation ensures that synthetic samples lie along the line segments connecting existing minority class samples to their nearest neighbors, maintaining local feature relationships while expanding the representation of minority class regions.

The k-nearest neighbor selection utilizes Euclidean distance in the standardized feature space:

Where p represents the number of features and denotes the value of feature f for sample . The default configuration employs k = 5 neighbors, striking a balance between preserving local structure and generating synthetic diversity.

SMOTE's effectiveness stems from its ability to create synthetic samples that reflect the local density and structure of minority class regions, enabling models to learn more robust decision boundaries around churning customers [

5,

27]. Unlike random oversampling, which duplicates existing samples, SMOTE's interpolative approach reduces the risk of overfitting while providing models with richer training examples that better represent the minority class distribution.

2.6.3. Random Under-Sampling

Random under-sampling addresses class imbalance by systematically removing majority class samples, thereby creating balanced training sets by reducing the number of non-churning customers rather than increasing the representation of churning customers. The implementation employs the RandomUnderSampler class from imbalanced-learn [

26], which performs random selection without replacement from the majority class population.

The under-sampling process operates by defining a target sampling ratio and randomly selecting samples from the majority class to achieve the desired class distribution. For a dataset with

majority class samples and

minority class samples, the balanced configuration removes samples to achieve:

The random selection process ensures that each majority class sample has an equal probability of retention:

where

represents a majority class sample. This uniform probability distribution prevents systematic bias in the retained majority class samples while maintaining the representative characteristics of the original majority class distribution.

The mathematical expectation of the sampling process preserves the population mean:

However, for finite samples, the sample variance exhibits increased uncertainty due to the reduced sample size. The sample variance

serves as an unbiased estimator of the population variance, but with increased variance around the true value:

This increased uncertainty reflects the fundamental trade-off in under-sampling: computational efficiency and class balance are achieved at the cost of statistical precision and potential information loss from discarded majority class samples.

Random under-sampling offers computational advantages by reducing training set sizes, thereby enabling faster model training and lower memory requirements. However, this efficiency gain introduces the risk of information loss, as potentially valuable patterns of the majority class may be eliminated during the random selection process. This technique proves particularly effective when the majority class samples contain significant redundancy or when computational constraints limit the feasibility of synthetic oversampling approaches. This sampling strategy employs automatic balancing, where the algorithm determines optimal sample sizes to achieve approximately equal class representation.

Figure 4 demonstrates the distributional effects of the resampling approaches on the class imbalance challenge described in the preceding sections. The visualization illustrates how SMOTE preserves and expands minority class representation through synthetic sample generation, while maintaining the local data structure. In contrast, the random under-sampling approach reduces majority class representation through systematic sample removal. These contrasting methodologies offer distinct advantages for model training. SMOTE's interpolative approach minimizes the risk of overfitting while providing richer training examples that better represent the minority class distribution. In contrast, random under-sampling offers computational efficiency and balanced training sets, but introduces potential information loss from discarded majority class samples.

2.7. Model Evaluation Framework

The evaluation of churn prediction models in a multi-client B2B environment presents unique challenges that extend beyond traditional single-dataset validation approaches. The heterogeneous nature of publisher portfolios, combined with temporal dependencies and class imbalance characteristics inherent in subscription-based data, requires a comprehensive evaluation framework that can reliably assess model performance across various contexts. This evaluation framework must balance statistics with interpretability, ensuring that performance metrics accurately reflect business-relevant performance while also guiding decision-making.

The evaluation methodology implemented in this study addresses these challenges through a multi-faceted assessment strategy that combines temporal robustness metrics with performance measurement across multiple complementary metrics. Each metric serves a distinct analytical purpose: probabilistic metrics assess the quality of uncertainty quantification, threshold-dependent metrics evaluate operational decision-making capabilities, and business-oriented metrics directly support business-relevant performance. The framework operates within the temporal validation structure described in

Section 2.3, ensuring that all performance assessments respect chronological boundaries and prevent data leakage while providing realistic estimates of deployment performance across varying temporal contexts.

2.7.1. Foundational Threshold-Dependent Metrics: Precision and Recall

Traditional binary classification metrics provide the foundational building blocks for advanced performance assessment in churn prediction scenarios. Precision and recall represent the core threshold-dependent measures that enable comprehensive evaluation of model performance under realistic deployment conditions, serving as essential components for both composite metrics and business decision-making processes.

These foundational metrics are calculated using the confusion matrix components derived from binary predictions at a specified threshold. For a given prediction threshold, precision quantifies the reliability of positive predictions and directly relates to intervention efficiency in retention strategies:

where

represents true positives (correctly identified churning customers) and

represents false positives (customers incorrectly flagged as churn risks). High precision indicates that customers flagged as churn risks are likely to actually churn, enabling efficient resource allocation and minimizing unnecessary intervention costs.

Recall, also known as sensitivity, measures the proportion of actual positive cases correctly identified, reflecting the model's ability to provide comprehensive coverage of at-risk customers:

where

represents false negatives (churning customers not identified by the model). High recall ensures that retention strategies can address the majority of potential churn events, maximizing the opportunity for successful intervention.

The inherent trade-off between precision and recall represents one of the most significant challenges for companies in churn prediction deployment. Increasing the prediction threshold typically improves precision by reducing false positives but decreases recall by increasing false negatives. This trade-off necessitates careful threshold selection based on business priorities, making these foundational metrics essential for understanding model behavior across different operating points.

2.7.2. Primary Performance Metric: Area Under Precision-Recall Curve

The Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (AUC-PR) serves as the primary metric for model comparison and selection, leveraging the foundational precision and recall metrics described in

Section 2.7.1 to provide a threshold-independent assessment of model performance. Unlike the commonly used Area Under ROC Curve (AUC-ROC), which can provide overly optimistic assessments when negative classes dominate the dataset, AUC-PR focuses exclusively on the model's ability to distinguish positive cases (churning customers) from the overall population, which perfectly fits the imbalanced nature of churn prediction data [

27].

The precision-recall curve is constructed by varying the prediction threshold across all possible values and plotting the resulting precision-recall pairs as defined in

Section 2.7.1. The AUC-PR is calculated as the area under this curve:

In practice, this integral is computed numerically since machine learning models produce discrete probability predictions rather than continuous curves. The standard approach uses the trapezoidal rule, which approximates the curved area by connecting consecutive precision-recall points with straight lines and summing the resulting trapezoidal areas [

31]. AUC-PR values range from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate superior model performance. A random classifier achieves an AUC-PR equal to the positive class prevalence, while a perfect classifier achieves AUC-PR = 1.

This metric provides a comprehensive assessment of the precision-recall trade-off across all possible operating points, enabling fair comparison across different models and temporal periods regardless of the specific threshold chosen for deployment.

2.7.3. Business-Oriented Metric: SPARTA Score

The SPARTA (SP Abonnee Retentie Toekomst Analyse, which is Dutch for SP Subscriber Retention Future Analysis, and the internal acronym for this project) score represents a composite metric that combines the foundational precision and recall measures defined in

Section 2.7.1 according to business operational priorities. This metric addresses the practical reality that precision and recall carry different operational costs and benefits in churn prediction deployments, requiring a weighted combination that reflects business constraints rather than statistical optimization alone.

The SPARTA score is calculated as a weighted combination of the precision and recall metrics:

The weights prioritize precision over recall, which reflects the operational constraint that retention interventions require significant resources and that false positive predictions impose a bigger risk by not “letting sleeping dogs lie” [

15]. Conversely, false negative predictions represent opportunity costs that, while significant, do not require immediate resource allocation.

This 70:30 weighting ratio was established through an interview with S.P. AbonneeService's CTO, Marc Dierikx, to reflect realistic intervention capacity constraints [

15]. The precision emphasis ensures that retention teams can effectively manage intervention workloads while the recall component maintains sensitivity to actual churn events, preventing excessive focus on precision at the expense of coverage.

The SPARTA score provides values between 0 and 1, where higher scores indicate better alignment with business operational requirements. Unlike purely statistical metrics, SPARTA directly supports decision-making about model deployment and intervention threshold selection, making it particularly valuable for translating statistical performance into actionable business insights.

2.7.4. Correlation-Based Performance Assessment: Matthews Correlation Coefficient

The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) offers a comprehensive evaluation of binary classification performance, taking into account all four components of the confusion matrix, making it particularly robust for imbalanced datasets where other metrics may yield misleading results. MCC is calculated as:

where

represents true negatives. MCC values range from -1 to +1, where +1 indicates perfect prediction, 0 represents random performance, and -1 indicates total disagreement between predictions and actual outcomes.

The MCC's strength lies in its balanced treatment of both positive and negative classes, providing reliable performance assessment even when class distributions vary significantly across temporal periods or publisher portfolios [

27,

28]. This characteristic makes MCC particularly valuable for assessing model stability across a heterogeneous data environment.

Unlike precision and recall, which focus exclusively on positive class performance, MCC provides insight into the model's overall classification ability, including its capacity to identify customers who will not churn correctly. This comprehensive perspective offers a deeper understanding of model behavior across the entire customer spectrum, helping to identify potential biases or systematic errors in prediction patterns.

2.7.5. Probabilistic Performance Assessment: Log Loss

Log loss, also known as cross-entropy loss, provides a probabilistic assessment of model performance that evaluates the quality of probability estimates rather than binary classification decisions. This metric is particularly valuable for understanding model calibration and confidence assessment, which are essential for assessing model stability and risk-based retention strategies that require a nuanced understanding of churn probabilities rather than simple binary predictions.

Log loss is calculated as:

where

represents the number of samples,

is the true binary label for the sample

, and

is the predicted probability of the positive class for the sample

. Lower log loss values indicate better probability estimation, with perfect probability estimates achieving log loss = 0.

The inclusion of log loss in the evaluation framework supports assessment of model uncertainty quantification, enabling identification of models that provide well-calibrated probability estimates. Such calibration is essential for business applications where retention interventions should be proportional to churn risk, requiring reliable probability estimates rather than simple binary classifications.

Log loss also provides insight into model overfitting and generalization capabilities, as poorly generalized models often exhibit extreme probability estimates that result in high log loss values on test data. This characteristic makes log loss valuable for hyperparameter optimization and model selection processes.

2.7.6. Temporal Performance Aggregation

The aggregation of performance metrics across temporal validation splits provides essential insights into model stability and generalization capabilities across varying temporal contexts. The aggregation strategy employed in this study calculates descriptive statistics for each metric across all temporal splits, providing a comprehensive assessment of both average performance and performance variability.

For each metric , the following aggregate statistics are computed across temporal splits:

Mean performance: Performance standard deviation: Coefficient of variation: The coefficient of variation provides a normalized measure of performance stability, enabling comparison across different metrics and models regardless of their absolute performance levels. Lower CV values indicate more consistent performance across temporal periods, suggesting better generalization capabilities and reduced sensitivity to temporal variations in customer behavior patterns.

A composite stability score is calculated as the inverse of the average coefficient of variation across key metrics (AUC-PR, SPARTA, and MCC), providing a single measure of overall temporal robustness:

The selection of these three metrics ensures comprehensive coverage while avoiding redundancy: AUC-PR provides threshold-independent ranking performance, SPARTA incorporates business-weighted precision and recall assessment, and MCC offers balanced correlation-based evaluation. Precision and recall are excluded from direct inclusion as they are already represented through their weighted combination in the SPARTA score. Log loss is excluded due to its unbounded upper range (0 to infinity), which differs from the bounded ranges of the other metrics (AUC-PR and SPARTA: 0-1; MCC: -1 to +1) and could distort the averaged coefficient of variation calculation.

This temporal aggregation approach enables identification of models that perform consistently across diverse temporal contexts, supporting selection of robust solutions suitable for deployment across the heterogeneous publisher portfolio characteristic of S.P. AbonneeService's operational environment.