Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

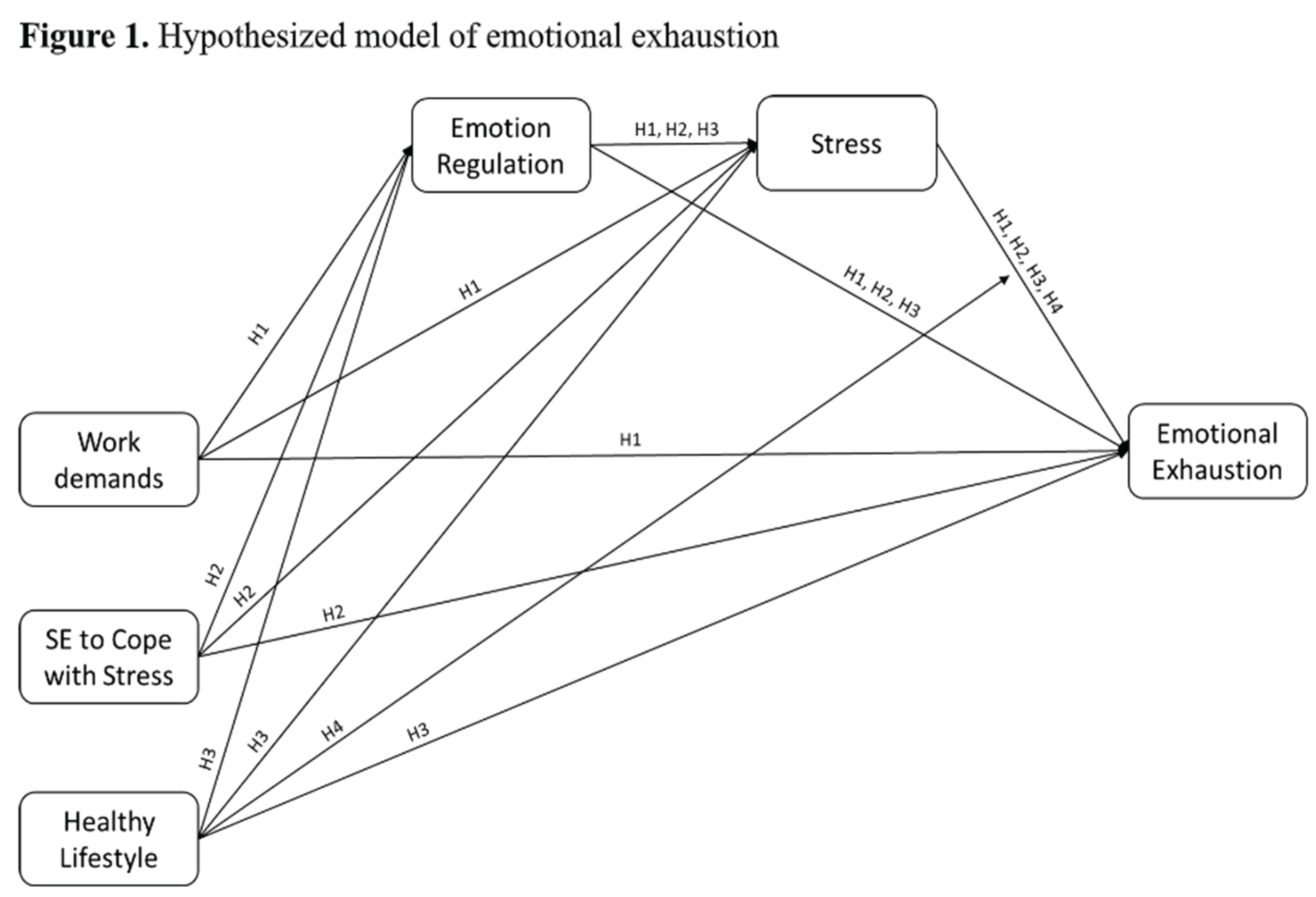

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analyses

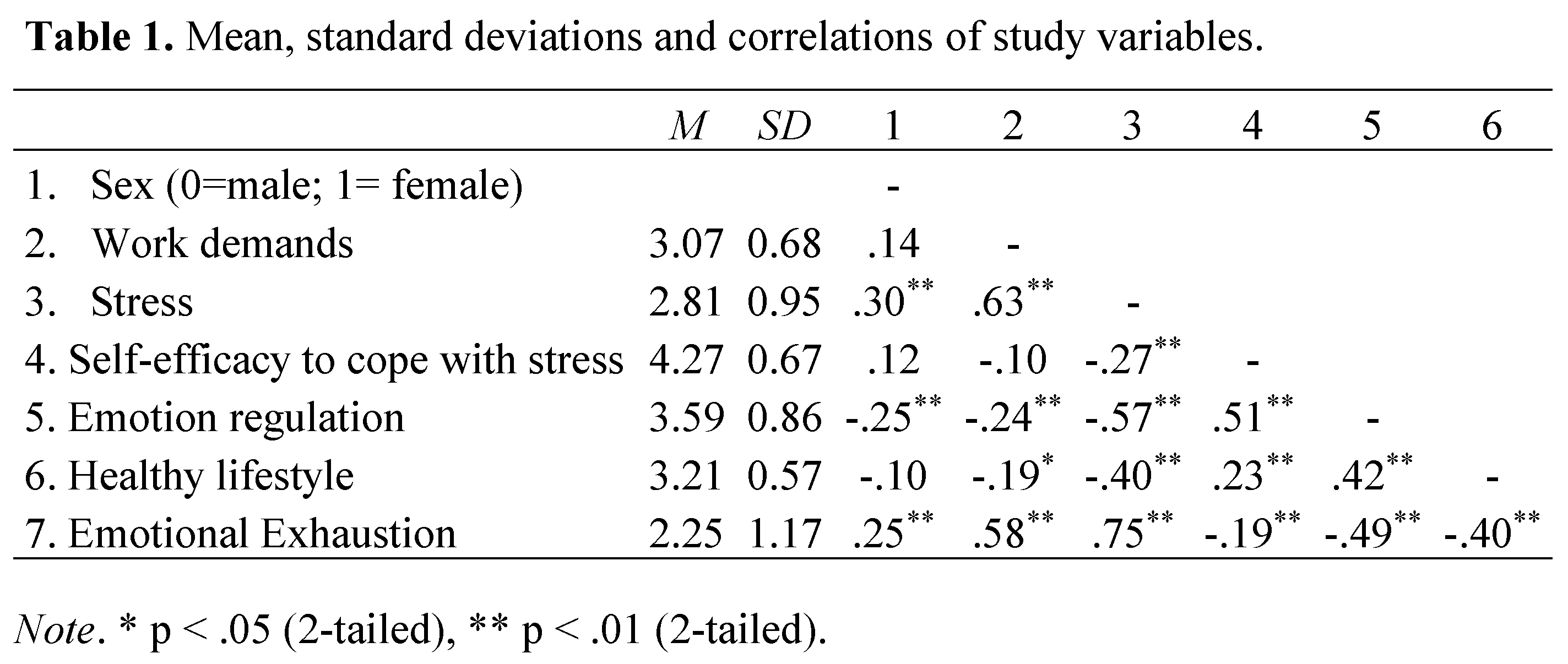

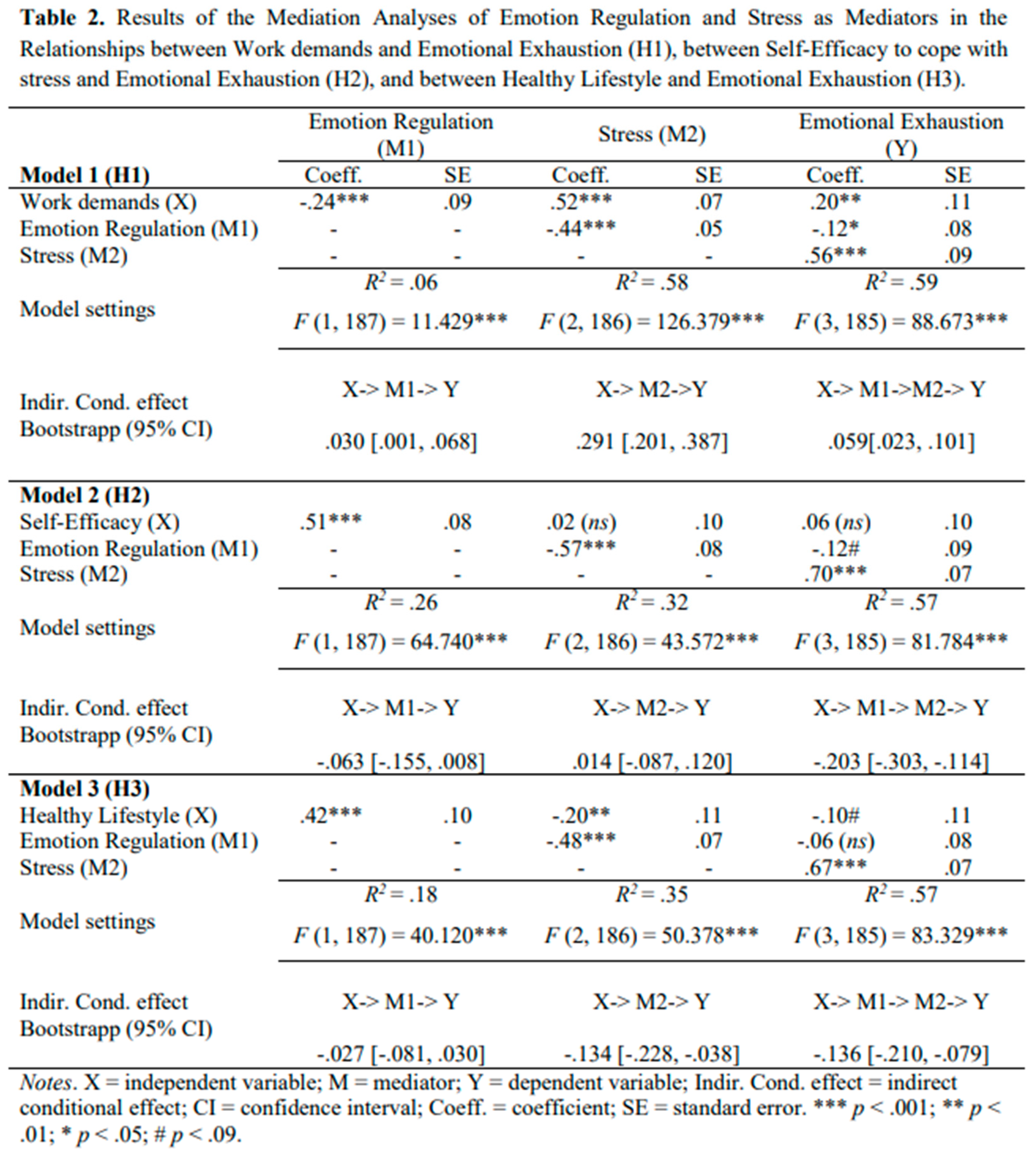

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

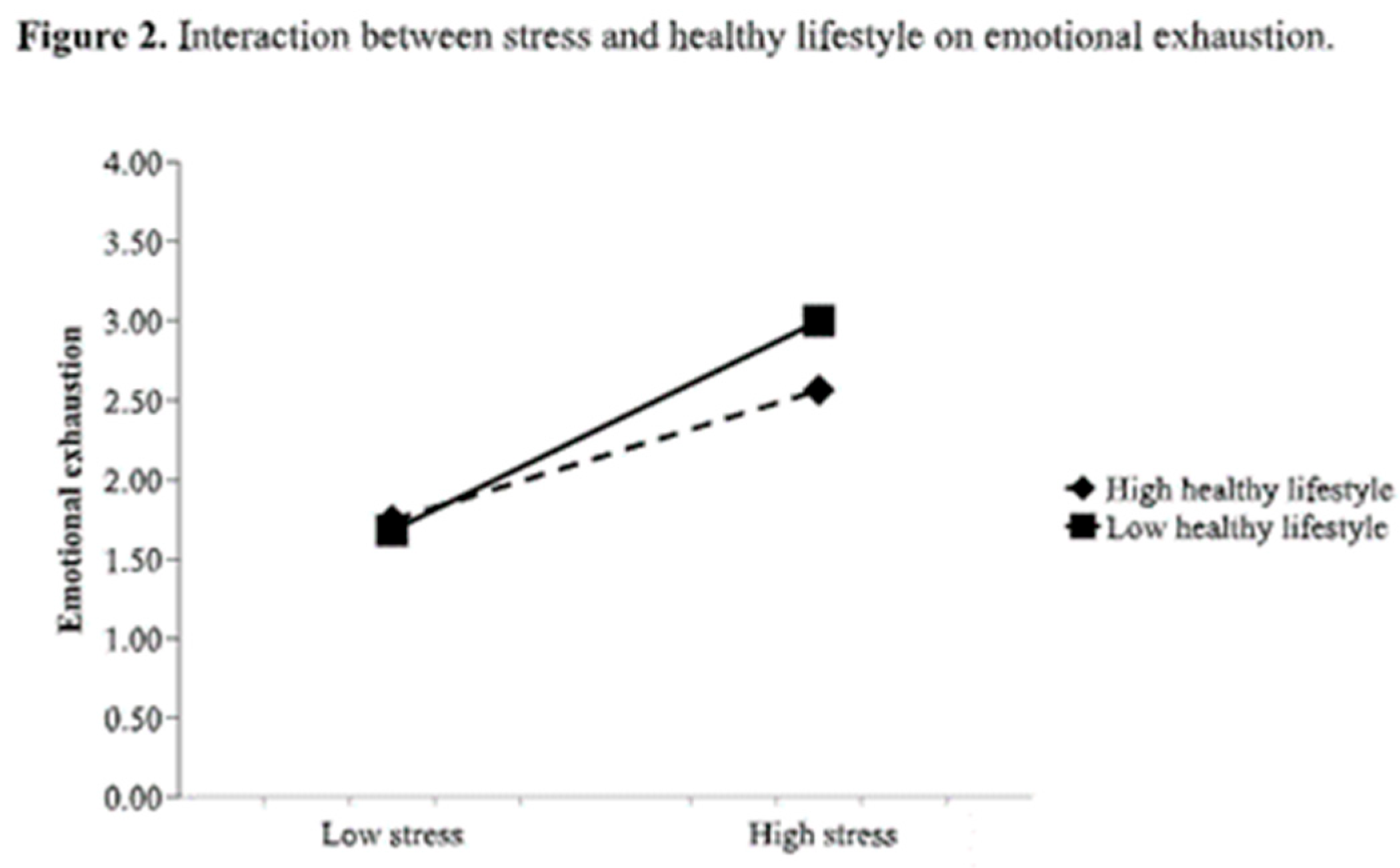

3.2. Mediation and Moderation Hypotheses

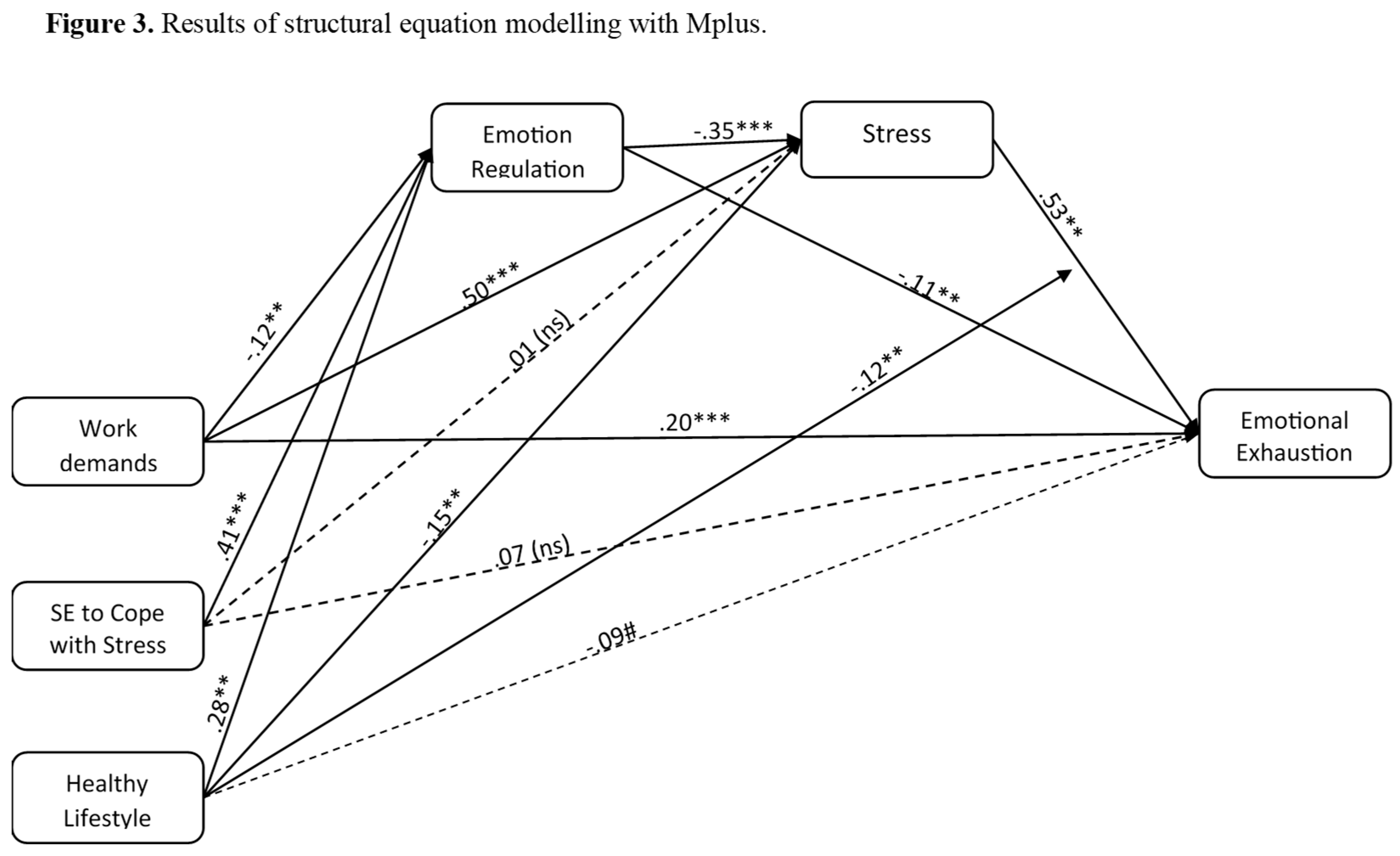

3.3. Predictive Model

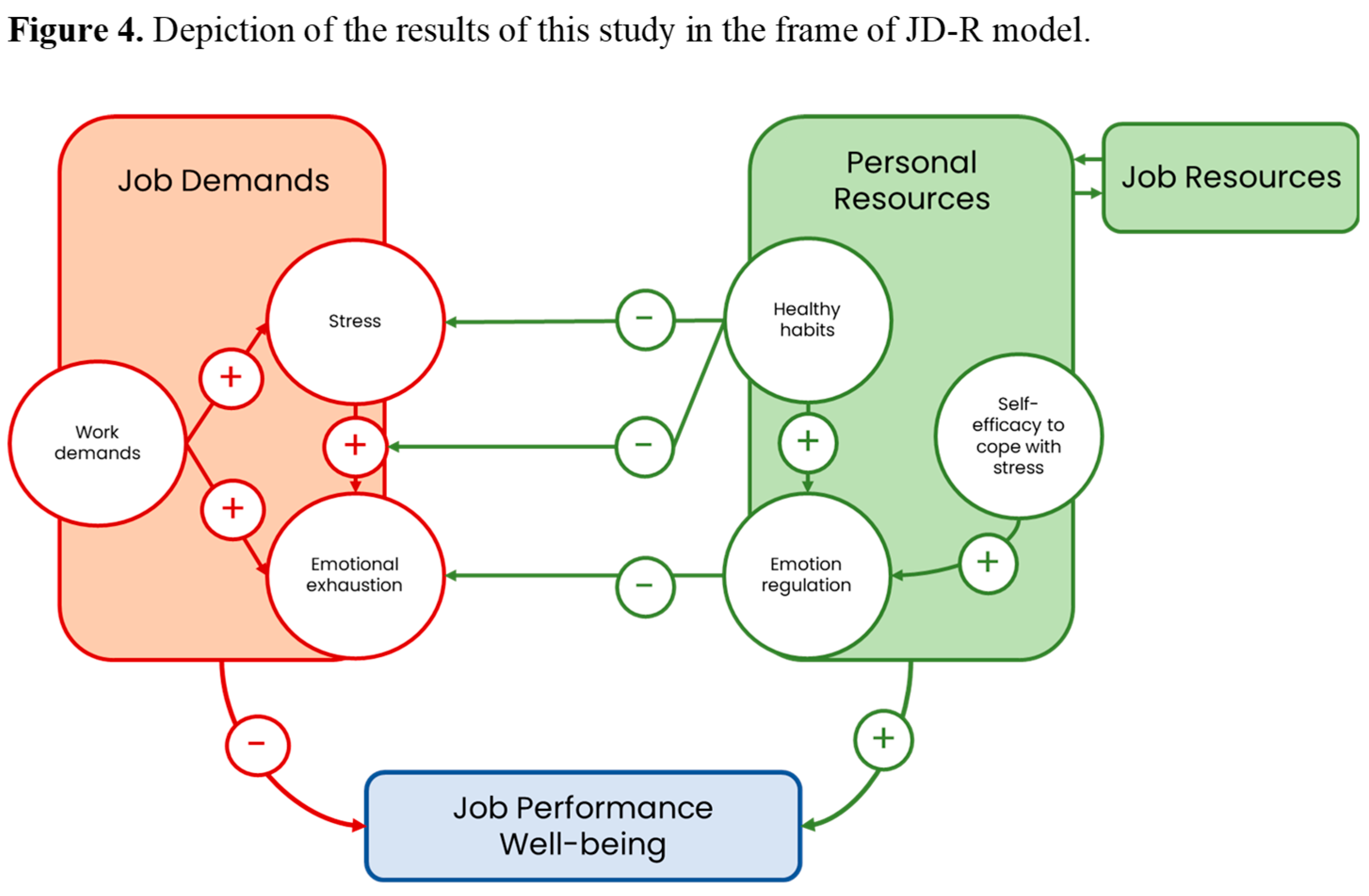

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walton, M.; Murray, E.; Christian, M.D. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2020, 9, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Z.; Han, M.F.; Luo, T.D.; Ren, A.K.; Zhou, X.P. Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19. Chin. J. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Dis. 2020, 38, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.P.; Kolcz, D.L.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Ferrand, J.; Fried, J.; Robinson, K. Health care workers’ mental health and quality of life during COVID-19: Results from a mid-pandemic, national survey. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, S.; Oetjen, N.; Du, J.; Posenato, E.; Resende de Almeida, R.M.; Losada, R.; Ribeiro, O.; Frisardi, V.; Hopper, L.; Rashid, A.; et al. Mental health among medical professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in eight European countries: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koinis, A.; Giannou, V.; Drantaki, V.; Angelaina, S.; Stratou, E.; Saridi, M. The impact of healthcare workers’ job environment on their mental-emotional health. Coping strategies: The case of a local general hospital. Health Psychol. Res. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Norman, I.; Xiao, T.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Leamy, M. Evaluating a psychological first aid training intervention (Preparing Me) to support the mental health and wellbeing of Chinese healthcare workers during healthcare emergencies: Protocol for a randomized controlled feasibility trial. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 809679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagni, M.; Maiorano, T.; Giostra, V.; Pajardi, D. Coping with COVID-19: Emergency stress, secondary trauma and self-efficacy in healthcare and emergency workers in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 566912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, K.; Sugawara, N.; Yasui-Furukori, N.; Danjo, K.; Furukori, H.; Sato, Y.; Tomita, T.; Fujii, A.; Nakagam, T.; Sasaki, M.; Nakamura, K. Relationship between occupational stress and depression among psychiatric nurses in Japan. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2016, 71, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Ahn, Y.S.; Kim, K.; Yoon, J.H.; Roh, J. Association between job stress and occupational injuries among Korean firefighters: A nationwide cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Paneque, R.J.; Pavés-Carvajal, J.R.P. Occupational hazards and diseases among workers in emergency services: A literature review with special emphasis on Chile. Medwave 2015, 15, e6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; International Labour Organization. Caring for Those Who Care: Guide for the Development and Implementation of Occupational Health and Safety Programmes for Health Workers; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040779 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.; Leiter, M. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, J.; Brotheridge, C. Resources, coping strategies, and emotional exhaustion: A conservation of resources perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D.R.; Matthews, L.M.; Ambrose, S.C. A meta-analytic review of emotional exhaustion in a sales context. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2019, 39, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiabane, E.; Gabanelli, P.; La Rovere, M.T.; Tremoli, E.; Pistarini, C.; Gorini, A. Psychological and work-related factors associated with emotional exhaustion among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italian hospitals. Nurs. Health Sci. 2021, 23, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Torre, M.; Ramos, M.A.; Rosales, R.C.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: A systematic review. JAMA 2018, 320, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, M.N.; Azza, A.A. Burnout and coping methods among emergency medical services professionals. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvanova, R.K.; Muros, J.P. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Herrero, S.; Mariscal-Saldaña, M.Á.; García-Rodríguez, J.G.; Ritzel, D.O. Influence of task demands on occupational stress: Gender differences. J. Saf. Res. 2012, 43, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; De Boer, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 62, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands-Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, K.; Cieslak, R.; Smoktunowicz, E.; Rogala, A.; Benight, C.C.; Luszczynska, A. Associations between job burnout and self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Grau, A.L. The influence of personal dispositional factors and organizational resources on workplace violence, burnout, and health outcomes in new graduate nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotel, A.; Golu, F.; Pantea Stoian, A.; Dimitriu, M.; Socea, B.; Cirstoveanu, C.; Davitoiu, A.M.; Jacota-Alexe, F.; Oprea, B. Predictors of burnout in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 1–604. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1994, 59, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Saudino, K.J. Emotion regulation and stress. J. Adult Dev. 2011, 18, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Stress and Emotions: A New Synthesis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–320. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Koku, G.; Grime, P. Emotion regulation and burnout in doctors: A systematic review. Occup. Med. 2019, 69, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Brufau, R.; Martin-Gorgojo, A.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Estrada, E.; Capriles-Ovalles, M.E.; Romero-Brufau, S. Emotion regulation strategies, workload conditions, and burnout in healthcare residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.C.J.; Durand-Bush, N.; Young, B.W. Self-regulation capacity is linked to wellbeing and burnout in physicians and medical students: Implications for nurturing self-help skills. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Iñigo, D.; Totterdell, P.; Alcover, C.M.; Holman, D. Emotional labour and emotional exhaustion: Interpersonal and intrapersonal mechanisms. Work Stress 2007, 21, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Huang, S.; Wang, W. Work environment characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of emotion regulation strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, J. Healthy lifestyle changes and mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Curr. Psychol. In press. [CrossRef]

- Balatoni, I.; Szépné, H.V.; Kiss, T.; Adamu, U.G.; Szulc, A.M.; Csernoch, L. The importance of physical activity in preventing fatigue and burnout in healthcare workers. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluut, H.; Wonders, J. Not able to lead a healthy life when you need it the most: Dual role of lifestyle behaviors in the association of blurred work-life boundaries with well-being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 607294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.K.; Barral, A.L.; Vincent, K.B.; Arria, A.M. Stress and burnout among graduate students: Moderation by sleep duration and quality. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2023, 28, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R. Job Content Instrument Questionnaire and User’s Guide, Version 1.1. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Moncada, S.; Llorens, C.; Andrés, R.; Moreno, N.; Molinero, E. Manual del método CoPsoQ-istas21 (versión 2) para la evaluación y la prevención de los riesgos psicosociales en empresas con 25 o más trabajadores y trabajadoras, VERSIÓN MEDIA.; Instituto Sindical de Trabajo, Ambiente y Salud: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Escobar Redonda, E. La evaluación del burnout profesional. Factorialización del MBI-GS. Un análisis preliminar. Ansiedad Estrés 2007, 7, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tabernero, C.; Arenas, A.; Briones, E. Self-efficacy training programs to cope with highly demanding work situations and prevent burnout. In Handbook of Managerial Behavior and Occupational Health; Antoniou, A., Cooper, C., Chrousos, G., Spielberger, C., Eysenck, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 278–291. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, G.V.; Di Giunta, L.; Eisenberg, N.; Gerbino, M.; Pastorelli, C.; Tramontano, C. Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychol. Assess. 2008, 20, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyton, M.; Lobato, S.; Batista, M.; Aspano, M.A.; Jiménez, R. Validación del cuestionario de estilo de vida saludable (EVS) en una población española. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. Deporte 2018, 13, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide. Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: http://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf.

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–816. [Google Scholar]

- Kinman, G.; Dovey, A.; Teoh, K. Burnout in Healthcare: Risk Factors and Solutions; Society of Occupational Medicine: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.som.org.uk/sites/som.org.uk/files/Burnout_in_healthcare_risk_factors_and_solutions_July2023.pdf.

- Pavlova, A.; Wang, C.X.; Boggiss, A.L.; O’Callaghan, A.; Consedine, N.S. Predictors of physician compassion, empathy, and related constructs: A systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.; Panagopoulou, E.; Esmail, A.; Richards, T.; Maslach, C. Burnout in healthcare: The case for organisational change. BMJ 2019, 366, l4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfik, D.S.; Profit, J.; Morgenthaler, T.I.; Satele, D.V.; Sinsky, C.A.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Tutty, M.A.; West, C.P.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Mousavi-Roknabadi, R.S. Burnout among healthcare providers of COVID-19: A systematic review of epidemiology and recommendations. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2021, 9, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Jang, K.S. Nurses’ emotions, emotion regulation and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 1409–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, E.; Tabernero, C.; Fajardo, C.; Luque, B.; Arenas, A.; Moyano, M.; Castillo-Mayén, R. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 37, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, R.A.; Skaalvik, E.M. Principal self-efficacy: Relations with burnout, job satisfaction and motivation to quit. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2012, 15, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T.; Réveillère, C.; Colombat, P.; Fouquereau, E. The effects of job demands on nurses’ burnout and presenteeism through sleep quality and relaxation. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulchar, R.J.; Haddad, M.B. Preventing burnout and substance use disorder among healthcare professionals through breathing exercises, emotion identification, and writing activities. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2022, 29, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, C.; Carlotto, M.S.; Kaiseler, M.; Dias, S.; Pereira, A.M. Predictors of burnout among nurses: An interactionist approach. Psicothema 2013, 25, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanullah, S.; Ramesh Shankar, R. The impact of COVID-19 on physician burnout globally: a review. Healthcare 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.J.; Machowski, S.; Holdsworth, L.; Kern, M.; Zapf, D. Age, emotion regulation strategies, burnout, and engagement in the service sector: Advantages of older workers. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 33, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huang, C.; Cheung, S.P.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, J. Job demands and resources, burnout, and psychological distress of social workers in China: Moderation effects of gender and age. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 741563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).