1. Introduction

Legumes played central roles in the development of agriculture and civilization, and they account for approximately one-third of the world’s primary crop production. In addition, legumes are also important due to their ecologically vital role in biological nitrogen fixation [

1]. The

Medicago genus is one of the most important forage resources and they are cultivated worldwide [

2]. In the

Medicago genus,

M. truncatula has been adopted as a model species for legumes [

3].

M. sativa (alfalfa) is highly productive, stress tolerant, and a valuable forage crop for livestock, which is referred as “the king of forage crop” [

4,

5].

M. falcata is mainly distributed in the north of China, Russia, Mongolia and Europe [

6], and grows in adverse environments, with great tolerance against abiotic stresses [

7].

The inheritance of the chloroplast genome with conserved gene content and order made it a valuable asset for studies in plant phylogenetic and evolutionary [

8,

9]. Chloroplast genomes of legumes have undergone considerable diversification in gene/intron content and gene order during phylogenetic evolution [

1]. It was reported that chloroplast genomes of some legume experienced rearrangement, including the loss of an inverted repeat or genes (e.g.

rpl22 and

rps16 genes) [

10,

11], or inversions of long fragments [

12,

13], including

Glycyrriza,

Astragalus,

Medicago,

Pisum, and

Vicia faba [

14]. As for alfalfa, its chloroplast DNA was thought unrearranged, except for the deletion of one segment of the IR [

10,

15].

M. falcata is considered as a wild species as well as a subspecies of

M. sativa complex [

4,

16]. It was still difficult to clearly distinguish among

M. sativa,

M. falcata and their hybrid

Medicago × varia based on the molecular and morphological evidence [

2]. Therefore, more chloroplast genomes of

M. falcata will be valuable genetic resources for the study of population genetics and evolutionary relationships of

Medicago species. In this study, we chose two

M. falcata ecotypes of different regions (e.g. Russia and Xinjiang, China) for complete chloroplast genome sequencing, our detailed analyses on chloroplast genomes of two new

M. falcata ecotype enrich and refine the chloroplast genome information of

M. falcata. In addition, this study would be helpful to further understand plastid evolution and phylogeny of the

Medicago genus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, DNA Extraction, and Sequencing

The plants of one

Medicago falcata ecotypes was obtained from the Federal Research Center of Russia Vavilov Institute of Plant Genetic Resources (MW271002, SRR15182922), and the other was were collected in Xinjiang, China (MW271003, SRR15182921), and they were cultivated in the greenhouse of the College of Grassland Science, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China. Total genomic DNA of

M. falcata was extracted from the fresh leaves by using the modified CTAB method [

17].

2.2. Chloroplast Genome Assembly and Annotation

The software GetOrganelle v1.5 [

18] was used to assemble the chloroplast genome, with the chloroplast genome of another

M. falcata ecotype (GenBank accession number: NC 032066.1) as reference. Chloroplast genome annotation was performed by using GeSeq [

19] (

https://chlorobox.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/geseq.html). In order to ensure the prediction accuracy of the encoded protein and RNA genes, the program Hmmer was used to predict the protein coding sequences, and ARAGORN v1.2.38 was used to predict the tRNA genes [

20], and the final annotation results were manually corrected. According to the annotation, circular diagram of the chloroplast genomes of

M. falcata was subsequently drawn using OGDRAW v1.3.1 [

21].

2.3. Genome Structure Analysis of Chloroplast Sequence

Perl scripts and Python scripts of self-written were used to process the chloroplast genome annotation files of five Medicago plant samples, and to calculate the basic data of the chloroplast genome structure, including the number of chloroplast genes, the total length of the chloroplast genome (bp), GC content, protein-coding gene number, CDS number, rRNA number and proportion, tRNA number and proportion, IR number, and the classification of chloroplast genes in the Medicago plant subgenus.

2.4. Analysis of the Chloroplast Genome Consistency

The Python script was used to process the annotation files of the five

Medicago plant samples, and the sequence comparison of whole chloroplast genome of five

Medicago samples were anzlyzed with the online mVISTA program (

http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/mvista/submit.shtml) [

22]. Then we selected Shuffle- LAGAN as the parameter for sequence comparison [

23]. The sequence identity of the chloroplast genomes of all

Medicago plant samples were analyzed, with the chloroplast genome of

M. falcata (NC 032066.1) as reference sequence.

2.5. Analysis of Simple and Complex Repeats

The program Tandem Repeats Finder [

24] and the online program reputer (

https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer) [

25] were used to predict repetitive sequence and scattered repetitive sequences. The local MISA program was used to predict the simple repeat sequence (SSR) [

26], and the maximal number of mononucleotide repeats, dinucleotide repeats, trinucleotide repeats, tetranucleotide repeats, pentanucleotide repeats and hexanucleotide repeats were set to 10, 6, 4, 3, 3, and 3, respectively.

2.6. Analysis of Nucleotide Polymorphism of the Chloroplast Genome

The commonly shared CDS sequences of five Medicago chloroplast were aligned with the muscle v3.8 program. DNAsp v6 was used to analyze the nucleotide polymorphism and calculate the nucleotide diversity.

2.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

A total of 37 chloroplast genome sequences were used for phylogenetic analysis, including 11 sequences of the Medicago genus and other 25 species of Leguminous plants, with chloroplast genome of Arabidopsis thaliana as outgroup. Because genetic evolutionary rates varied in different regions over the whole chloroplast genome, the phylogenetic trees were built based on the following two datasets: (1) the complete chloroplast genomes, and (2) the CDS sequences.

3. Results

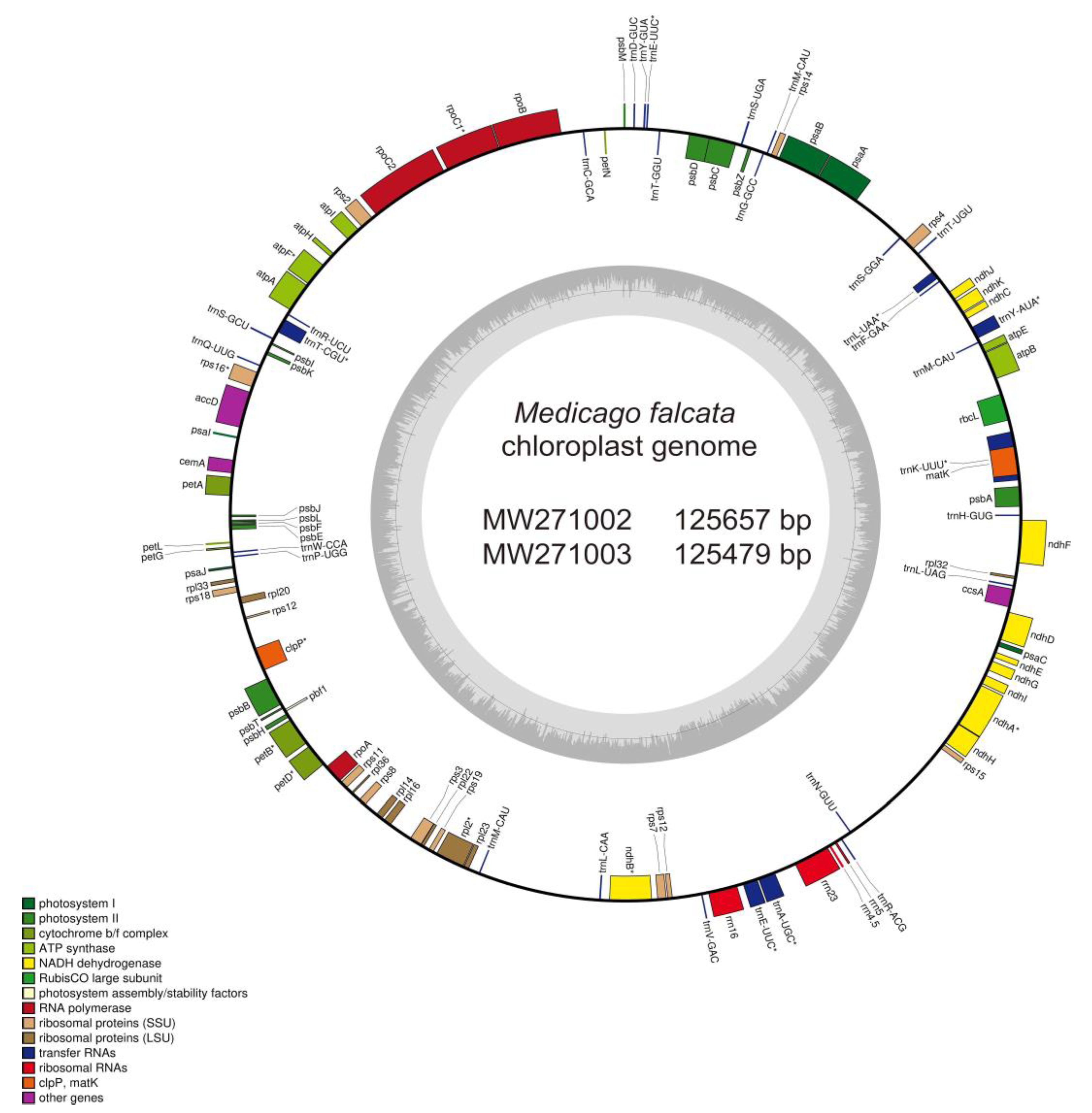

3.1. Characterization of the Chloroplast Genomes of Two M. falcata Ecotype

We used NovaSeq 6000 sequencing platform to generate raw data (3.4G) from the two

M. falcata chloroplast, and deposited them at the GenBank database, and MW271002 and SRR15182922 were for the one obtained from Russia, and MW271003 and SRR15182921 were for the other one collected from Xinjiang, China. The length of the complete chloroplast genomes of these two

M. falcata are 125,657 bp and 125,479 bp in length (Figure. 1,

Table 1). By comparison, the chloroplast genome of

M. falcata strain 1210,

M. sativa and

M. truncatula are 124,430, 125,330 and 124,033 bp in length, respectively (

Table 1). In details, their chloroplast genome sequences contained 112 unique genes, including 78 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNA genes and 4 rRNA genes. Of all five samples, except for

M truncatula, all the others had identical numbers of protein-coding genes (78) and rRNA genes (4). It is worth noting that

M. falcata (NC 032066.1) from Inner Mongolia of China lacks two tRNA, while the other two ecotypes of

M. falcata have 30 tRNAs (

Table 2).

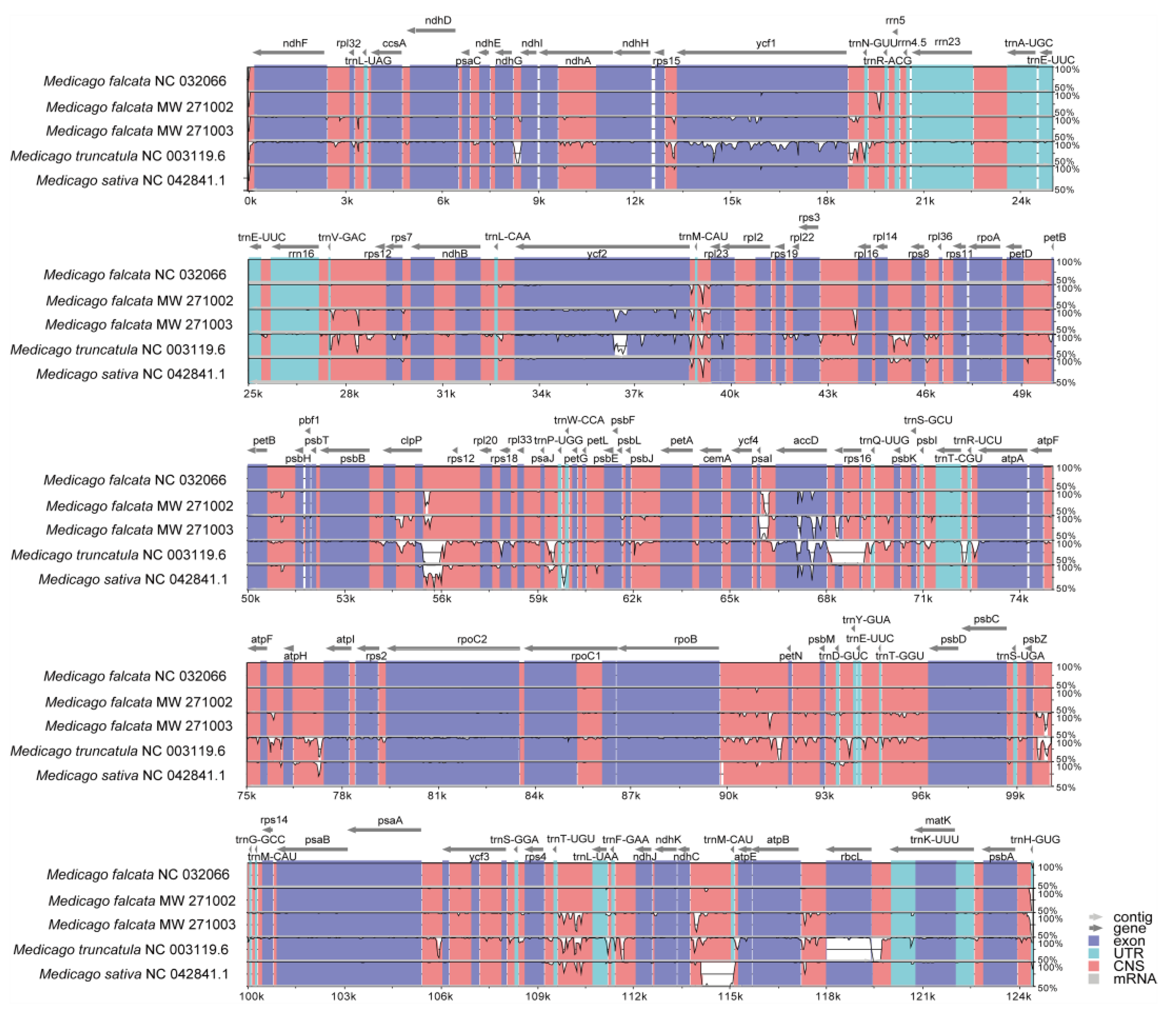

3.2. Comparative Analysis of the Chloroplast Genome of Three Medicago Species

The mVISTA-based identity plot indicated conservation in DNA sequence and gene synteny across the whole chloroplast genome, and revealed the areas with increased genetic variation (

Figure 2). The genes number, order and orientation were found to be highly conserved. However, their CDS regions showed distinct variation (

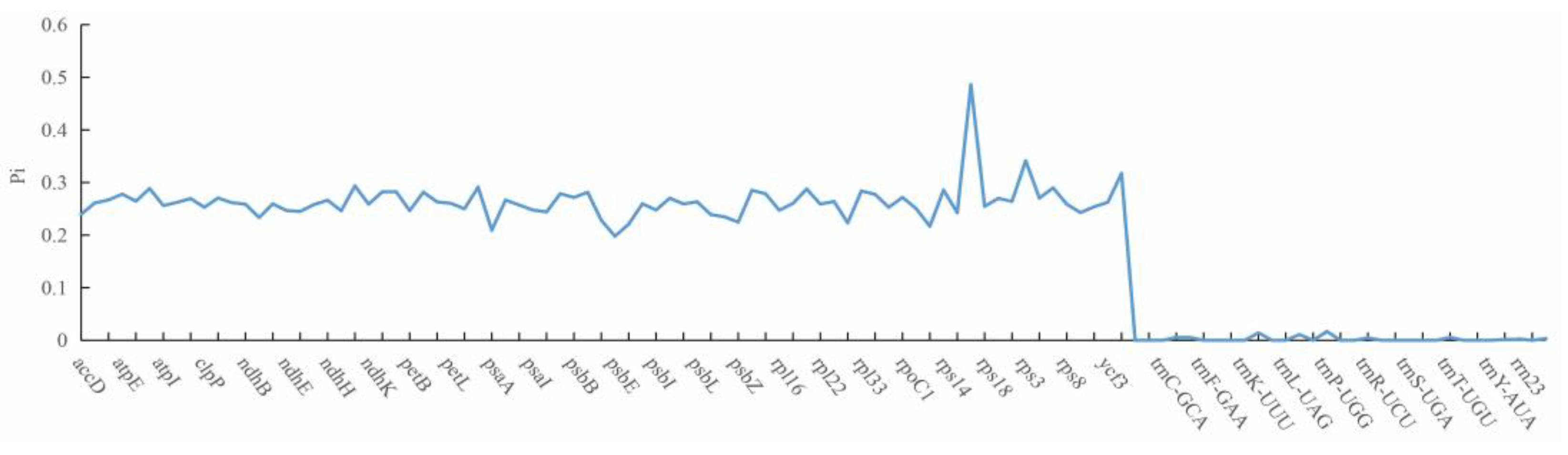

Figure 2). Further analysis on nucleotide polymorphisms (nucleotide diversity) indicated that 87 out of 108 genes differed among these five

Medicago species, but no difference was found for the remaining 21 genes. In this study, we found that all rRNA and tRNA genes are highly conserved (

Figure 3). Compared with tRNA genes and rRNA genes, protein-coding genes had relatively higher nucleotide diversity (

Figure 3,

Table S1), and the highest nucleotide diversity was 0.486 for

rps16, while the lowest value was 0.198 for

psbE. The analyses on the nucleotide diversity revealed the variation size of the chloroplast genome in different

Medicago species, and regions with high nucleotide diversity (e.g.

rps16,

rps3 and

ycf) may be developed as potential molecular markers for population genetics.

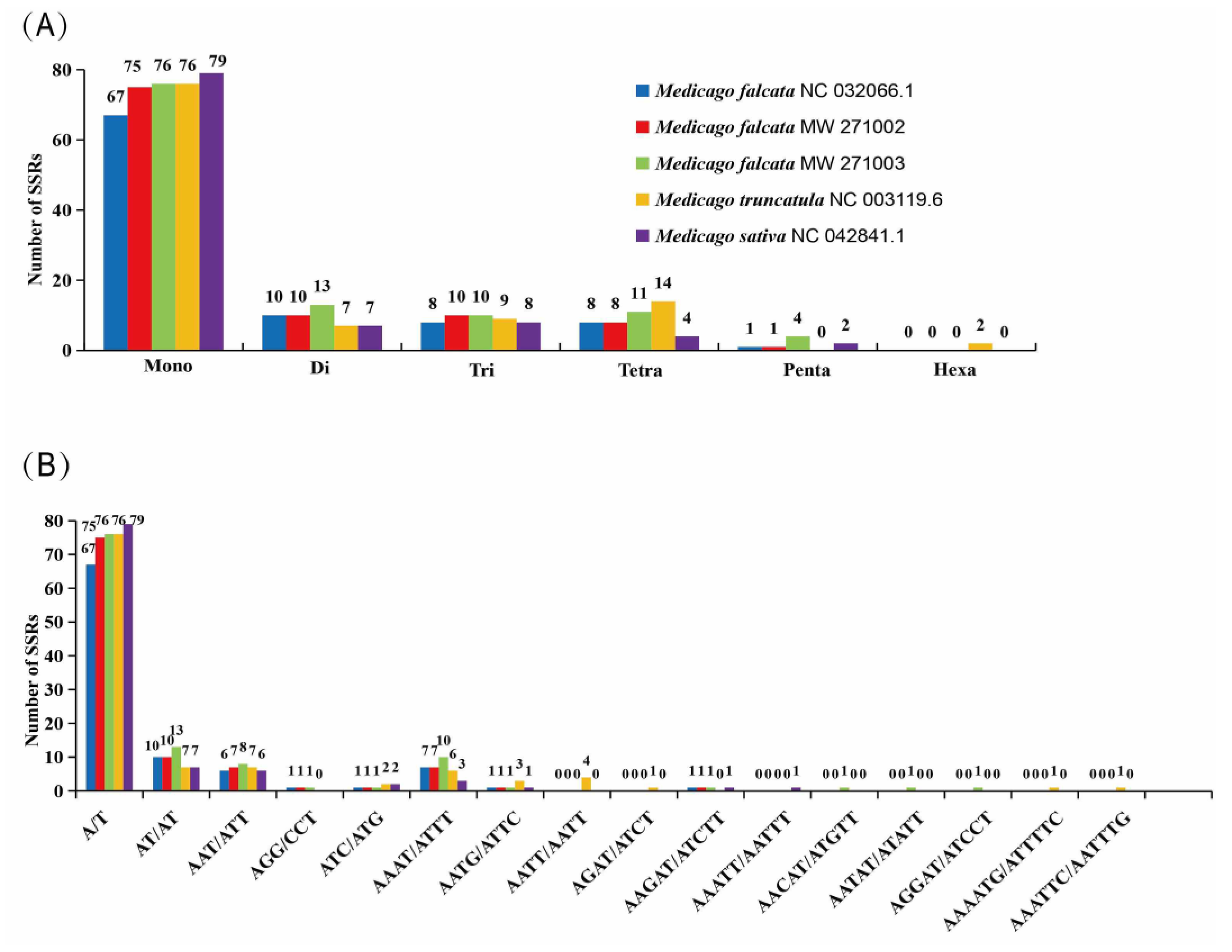

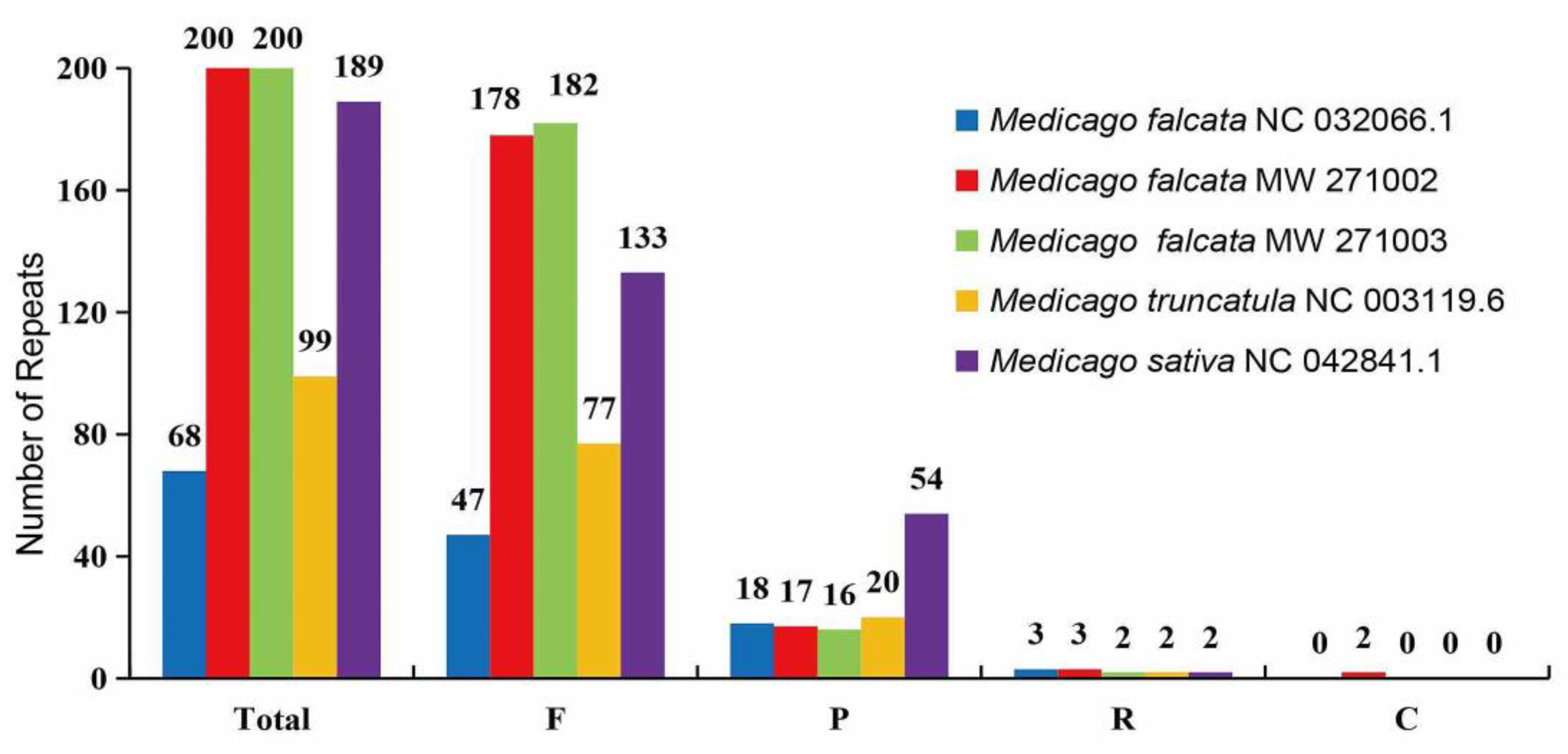

3.3. Features of the cpDNA Repeats of Medicago

Complete chloroplast genomes of all five

Medicago species contained mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta- and hexanucleotide SSRs. The most abundant repeats are mononucleotide repeats, accounting for more than 71.73% of the total SSRs, followed by the di-, tri-, tetra- and pentanucleotides (

Figure 4A). Considering sequence complementary, 16 classified repeat types were found in all five

Medicago species. The most abundant repeat type was A/T, and they were 67, 75, 76, 76, and 79 in

M. falcata NC 032066.1,

M. falcata MW 271002,

M. falcata MW 271003,

M. truncatula, and

M. sativa, respectively (

Figure 4B).

We detected four different types of long dispersed repeats (LDRs), namely forward (F), palindromic (P), reverse (R) and complement (C) repeats. Among these large repeats, forward repeats were found to be the most abundant, ranging from 47 to 182, followed by the palindromic repeats that ranged from 16 to 54 (

Figure 5). And two complementary repeats were found in

M. falcata MW271002, which was absent in the other four accesions (

Figure 5).

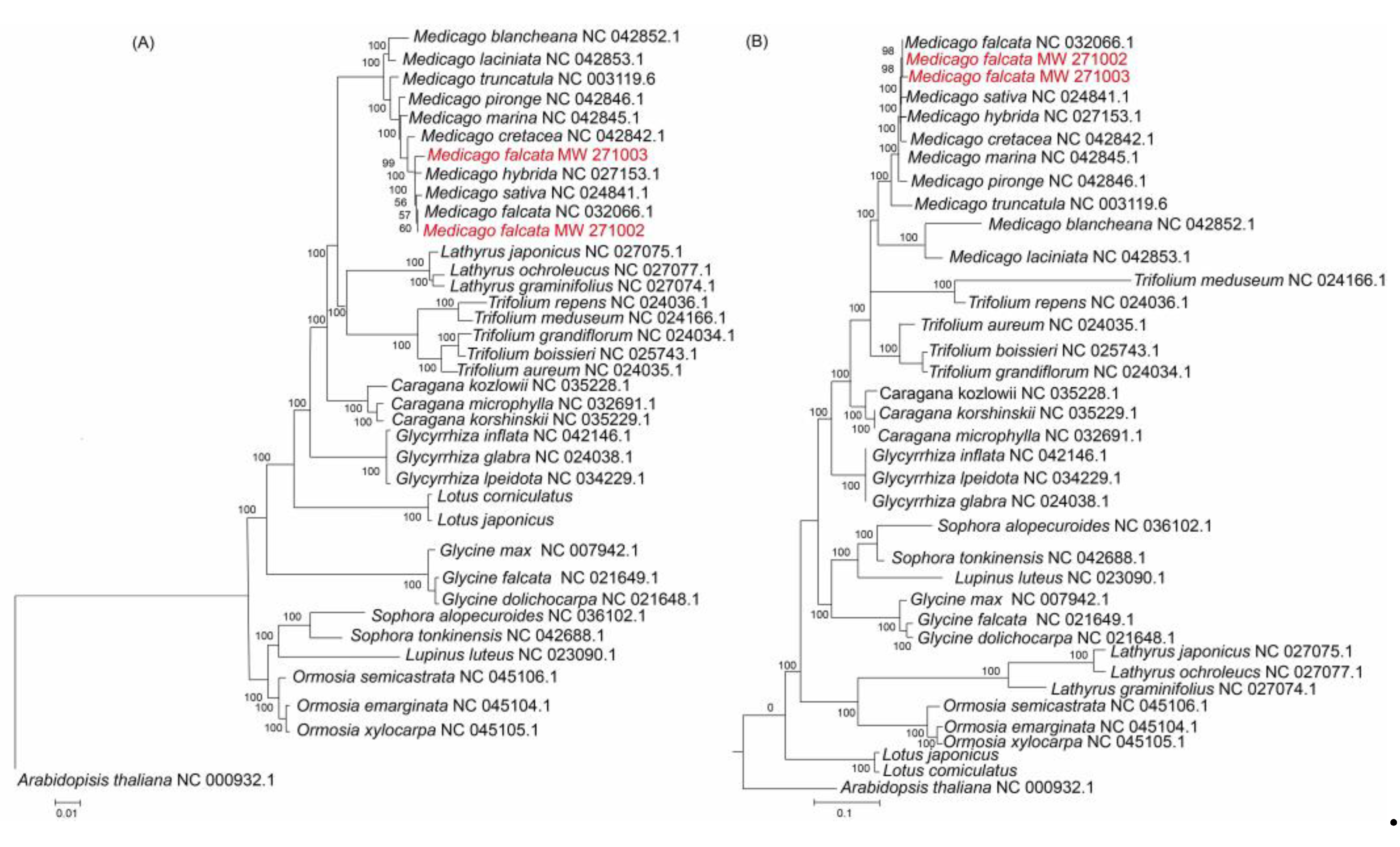

3.4. Phylogenetic Relationship Between Medicago and Related Species

The phylogenetic trees were constructed based on both CDS (CDS regions of 78 protein-coding genes) and the complete chloroplast genome sequences of 36 leguminous species and one outgroup

Arabidopsis thaliana (

Figure 6). Within the cluster of the

Medicago genus, slight difference was found for the relationship between the trees clustering with the CDS or clustering with the complete chloroplast genome sequences. The phylogenetic tree constructed with the full length is more accurate than the phylogenetic tree clustering with the CDS regions. The phylogenetic analysis with the complete chloroplast genome sequences showed that

M. falcata MW271002 and

M. falcata MW271003 were both clustered with

M. falcata, and they were close to

M. sativa and

M. hybrida (

Figure 6B), which was supported by high bootstrap value (>98%), and this result is consistent with previous phylogenetic analyses [

4,

16]. In both phylogenetic trees, the position of

M. falcata MW271003 was closely related to another two species

M. hybrida and

M. sativa, implying that

M. falcata and

M. sativa might have evolved from

M. hybrida during evolutionary.

4. Discussion

4.1. Conservation of Medicago cpDNA

Chloroplast genomes are highly conserved in angiosperms with respect to gene content and order [

27]. The highly conserved structure of the chloroplast genome is a potential source for the phylogenetic reconstruction of species relationships among legume plants [

28]. The number, type, and order of genes were found to be very similar among the chloroplast genome sequences of these five

Medicago samples [

1,

15,

29]. By comparison, the complete chloroplast genome sequence of

M. falcata MW 271002 and

M. falcata MW 271003 are longer than those of

M. sativa and

M. truncatula.

M. falcata (NC 032066.1) and

M. sativa have two more genes (e.g.

trnC-GCA and

trnY-AUA) (

Table 1) than the others, while

M. truncatula lacks of a protein-coding gene

rps16 (

Table 1).

M. falcata has a special chloroplast structure containing only one copy of the IR region, but lacks the quadripartite structure (

Figure 1,

Table 1), which is different from the chloroplast genomes of the majority of typical land plants that have two copies of IR region [

30]. In addition, lacking of IR can cause gene extensive rearrangement, this phenomenon mainly occurs in the legume tribes, including subclover, broad bean, pea and alfalfa [

10,

15,

31]. The

infA gene

was found in most angiosperm chloroplast genomes including representatives of the early branching lineages [

30], but it was not present in

M. falcata or

M. sativa chloroplast genome, which may be due to the presence of one IR. These results support the hypothesis that the presence of the large inverted repeat stabilizes the chloroplast genome against major structural rearrangements. The GC levels of the complete chloroplast genomes in angiosperm chloroplast genomes were very similar, ranging from 36.7% to 37.0% [

32,

33]. However, in our study, GC content of these species of

Medicago are 33.8%, the relatively low GC content may be due to the components and numbers of pseudogene [

34].

4.2. Simple and Complex Repeats Analysis

Large, complex repeat sequences may play important roles in the rearrangement of plastid genomes and sequence divergence [

35,

36]. Differential distribution of these repeats is associated with complete chloroplast genome rearrangement and nucleotide substitution, therefore, these repeats could be used to develop genetic markers for phylogenetic studies [

36]. The results are comparable to previously reported findings that SSRs in the complete chloroplast genomes are mainly composed of polyadenine (poly A) or polythymine (poly T) repeats and rarely tandem guanine (G) or cytosine (C) repeats [

33,

37]. The phenomenon of A/T richness in the SSR of land plants has been reported previously, and the finding in our study are consistent with those in other species [

37,

38,

39,

40].

The most abundant are mononucleotide repeats, accounting for more than 71.73% of the total SSRs, followed by the di-, tri-, tetra- and pentanucleotides(Figure

4A), similar to the results in

Lilium [

33]

; we also found that tetranucleotide repeats were more abundant than pentanucleotide repeats, which is consistent with a report on Quercus [

41]; Hexanucleotide repeats were very rare across the five

Medicago complete

chloroplast genomes, similar to the results in

Lilium and

Allium [

33,

34]; Forward repeats were more abundant than reverse and palindrome repeats (Figure

4B)[

42]. These new resources will be potentially useful for population studies in the genus

Medicago.

4.3. Phylogenetic

Phylogenetic analyses based on complete plastid genome sequences have provided valuable insights into relationships among and within plant genera. As recorded in the flora of China,

M. falcata is not only considered as a wild species, but also a subspecies of

M. sativa [

4,

16], which is consistent with our our phylogenetic analyses(Figure 6). As reported previously, even grows in the same area, the phenotypic traits of

M. falcata also show considerable differences between individuals [

2]. These variation between individuals even within the same population may be related to the characteristics of cross-pollination of

M. falcata and its ability to adapt to adverse environment. Therefore, the characterization of multiple complete chloroplast genome provided the opportunity for comparison and investigation with the current

M. falcata chloroplast genome. In the genus

Medicago, species with relatively close phylogenetic relationship clustered together could be explained by frequent genetic exchange and gene introgression among species.

5. Conclusions

We determined the complete chloroplast genomes sequences of two M. falcata from Russia and Xinjiang in this study. The results revealed that the orientation, structure, size, genes number, order , GC content were conserved among five Medicago, including M. falcata NC 032066.1, Medicago falcata MW271002, M. falcata MW271003, M. truncatula NC 003119.6 and M. sativa NC 042841.1. However, there are slightly differences in the number of protein coding genes number and tRNA gene number, comparative analysis of sequence differences, the protein-coding genes similarity was low, large variation between CDS. Further analysis of nucleotide polymorphisms, observations of nucleotide diversity indicated that 87 of 108 surveyed regions differ among the five Medicago species, the nucleotide diversity of other coding genes are very high, also exceeded 0.2. In our study, we observed that all rRNA and tRNA genes are highly conserved. The most abundant are mononucleotide repeats, followed by the di-, tri-, tetra-, and penta-, forward repeats were more abundant than reverse and palindrome repeats. Two phylogenetic tree analysis results are slightly different, the phylogenetic tree made from the full length is more accurate than the CDS phylogenetic tree clustering; These results offer valuable information for future research in the identification of Medicago species and will benefit further investigations of these species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Detailed nucleotide diversity values between five Medicago species determined using whole chloroplast genomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: W.Y. and L.Q.; methodology: D.W. and Z.X.; formal analysis: D.W. and Z.X.; writing-original draft preparation: D.W.; writing-review and editing: W.Y. and L.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jansen, R.K.; Cai, Z.; Raubeson, L.A.; Daniell, H.; Depamphilis, C.W.; Leebens-Mack, J.; Müller, K.F.; Guisinger-Bellian, M.; Haberle, R.C.; Hansen, A.K.; Chumley, T.W.; Lee, S.B.; Peery, R.; McNeal, J.R.; Kuehl, J.V.; Boore, J.L. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome - scale evolutionary patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 19369–19374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wu, G.; Shrestha, N.; Wu, S.; Guo, W.; Yin, M.; Li, A.; Liu, J.; Ren, G. Phylogeny and Species Delimitation of Chinese Medicago (Leguminosae) and Its Relatives Based on Molecular and Morphological Evidence. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 619799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedito, V.A.; Torres-Jerez, I.; Murray, J.D.; Andriankaja, A.; Allen, S.; Kakar, K.; Wandrey, M.; Verdier, J.; Zuber, H.; Ott, T.; Moreau, S.; Niebel, A.; Frickey, T.; Weiller, G.; He, J.; Dai, X.; Zhao, P.X.; Tang, Y.; Udvardi, M.K. A gene expression atlas of the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 2008, 55, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, E.M.J. A synopsis of the genus Medicago (Leguminosae). Revue Canadienne De Botanique 1989, 67, 3260–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, T.; Ma, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, P.X.; Nan, Z.; Wang, Y. Global transcriptome sequencing using the Illumina platform and the development of EST - SSR markers in autotetraploid alfalfa. PLoS One 2013, 8, e83549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; He, S.; He, X.; Lu, S.; Guo, Z. An eukaryotic elongation factor 2 from Medicago falcata (MfEF2) confers cold tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Zhao, M.G.; Tian, Q.Y.; Zhang, W.H. Comparative studies on tolerance of Medicago truncatula and Medicago falcata to freezing. Planta 2011, 234, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birky, C.W. Jr. The inheritance of genes in mitochondria and chloroplasts: laws, mechanisms, and models. Annu Rev Genet. 2001, 35, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Q.; Ge, S. The phylogeny of the BEP clade in grasses revisited: evidence from the whole - genome sequences of chloroplasts. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012, 62, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.D.; Osorio, B.; Aldrich, J.; et al. Chloroplast DNA evolution among legumes: Loss of a large inverted repeat occurred prior to other sequence rearrangements. Current Genetics 1987, 11, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saski, C.; Lee, S.B.; Daniell, H.; et al. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Glycine max and Comparative Analyses with other Legume Genomes. Plant Molecular Biology 2005, 59, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, J.D.; Thompson, W.F. Rearrangements in the chloroplast genomes of mung bean and pea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1981, 78, 5533–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruneau, A.; Palmer, D.J.D. A Chloroplast DNA Inversion as a Subtribal Character in the Phaseoleae (Leguminosae). Systematic Botany 1990, 15, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, M.F.; Lavin, M.; Sanderson, M.J. A phylogeny of legumes (Leguminosae) based on analysis of the plastid matK gene resolves many well - supported subclades within the family. Am J Bot. 2004, 91, 1846–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) (Leguminosae). Gene Reports 2017, 6, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiros, C.F.; Bauchan, G.R. The genus Medicago and the origin of the Medicago sativa complex. Agronomy 1988, 93−124. [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.C.; Flores-Vergara, M.A.; Krasynanski, S.; Kumar, S.; Thompson, W.F. A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissues using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Nat Protoc. 2006, 1, 2320–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Yu, W.B.; Yang, J.B.; Song, Y.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.S.; Li, D.Z. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillich, M.; Lehwark, P.; Pellizzer, T.; Ulbricht - Jones, E.S.; Fischer, A.; Bock, R.; Greiner, S. GeSeq - versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W6–W11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laslett, D.; Canback, B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, S.; Lehwark, P.; Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W59–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, K.A.; Pachter, L.; Poliakov, A.; Rubin, E.M.; Dubchak, I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brudno, M.; Do, C.B.; Cooper, G.M.; Kim, M.F.; Davydov, E.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Green, E. D.; Sidow, A.; Batzoglou, S. LAGAN and Multi - LAGAN: efficient tools for large - scale multiple alignment of genomic DNA. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, S.; Schleiermacher, C. REPuter: fast computation of maximal repeats in complete genomes. Bioinformatics 1999, 15, 426–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, S.; Himmelbach, A.; Colmsee, C.; Zhang, X.Q.; Barrero, R.A.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Bayer, M.; Bolser, D.; Taudien, S.; Groth, M.; Felder, M.; Hastie, A.; Šimková, H.; Staňková, H.; Vrána, J.; Chan, S.; Muñoz - Amatriaín, M.; Ounit, R.; Wanamaker, S.; Schmutzer, T.; Aliyeva - Schnorr, L.; Grasso, S.; Tanskanen, J.; Sampath, D.; Heavens, D.; Cao, S.; Chapman, B.; Dai, F.; Han, Y.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Lin, C.; McCooke, J.K.; Tan, C.; Wang, S.; Yin, S.; Zhou, G.; Poland, J.A.; Bellgard, M.I.; Houben, A.; Doležel, J.; Ayling, S.; Lonardi, S.; Langridge, P.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Kersey, P.; Clark, M.D.; Caccamo, M.; Schulman, A.H.; Platzer, M.; Close, T.J.; Hansson, M.; Zhang, G.; Braumann, I.; Li, C.; Waugh, R.; Scholz, U.; Stein, N.; Mascher, M. Construction of a map - based reference genome sequence for barley, Hordeum vulgare L. Sci Data 2017, 4, 170044. Sci Data 2017, 4, 170044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, M. The chloroplast genome. Plant Mol Biol. 1992, 19, 149–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendar, S.; Na, YW.; Lee, J.R.; Shim, D.; Ma, K.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Chung, J.W. The complete chloroplast genome of Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum using Illumina sequencing. Molecules. 2015, 20, 13080–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Shi, W.; Liu, L.; Ma, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Hou, X. Complete sequencing of the chloroplast genomes of two Medicago species. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2017, 2, 302–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubeson, L.A.; Peery, R.; Chumley, T.W.; Dziubek, C.; Fourcade, H.M.; Boore, J.L.; Jansen, R.K. Comparative chloroplast genomics: analyses including new sequences from the angiosperms Nuphar advena and Ranunculus macranthus. BMC Genomics 2007, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, S.H.; Palmer, J.D.; Howe, G.T.; Doerksen, A.H. Chloroplast genomes of two conifers lack a large inverted repeat and are extensively rearranged. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988, 85, 3898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, J.Y.; Yang, T. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome sequences of a normal male-fertile cytoplasm and two different cytoplasms conferring cytoplasmic male sterility in onion (Allium cepa L). Journal of Horticultural Science & Biotechnology, 2015, 90, 459–468. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.P.; Bi, Y.; Yang, F.P.; Zhang, M.F.; Chen, X.Q.; Xue, J.; Zhang, X.H. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Lilium: insights into evolutionary dynamics and phylogenetic analyses. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Y.; Gao, L.; Liu, B.; Yang, Y.; Kong, S.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, X. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of four Allium species: comparative and phylogenetic analyses. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 12250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timme, R.E.; Kuehl, J.V.; Boore, J.L.; Jansen, R.K. A comparative analysis of the Lactuca and Helianthus (Asteraceae) plastid genomes: identification of divergent regions and categorization of shared repeats. Am J Bot. 2007, 94, 302–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, M.L.; Blazier, J.C.; Govindu, M.; Jansen, R.K. Reconstruction of the ancestral plastid genome in Geraniaceae reveals a correlation between genome rearrangements, repeats, and nucleotide substitution rates. Mol Biol Evol. 2014, 31, 645–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Z.H. The complete chloroplast genome of Tamarix ramosissima and comparative analysis of Tamaricaceae species. Biologia Plantarum 2021, 65, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaila, T.; Chaduvla, P.K.; Rawal, H.C.; Saxena, S.; Tyagi, A.; Mithra, S.V.A.; Solanke, A.U.; Kalia, P.; Sharma, T.R.; Singh, N.K.; Gaikwad, K. Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Clusterbean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L.): Genome Structure and Comparative Analysis. Genes (Basel) 2017, 8, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tan, W.; Sun, J.; Du, J.; Zheng, C.; Tian, X.; Zheng, M.; Xiang, B.; Wang, Y. Author Correction: Comparison of Four Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Medicinal and Ornamental Meconopsis Species: Genome Organization and Species Discrimination. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 15163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somaratne, Y.; Guan, D.L.; Wang, W.Q.; Zhao, L.; Xu, S.Q. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Xanthium sibiricum provides useful DNA barcodes for future species identification and phylogeny. Plant Systematics and Evolution 2019, 305, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Duan, D.; Yang, J.; Feng, L.; Zhao, G. Comparative Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Five Quercus Species. Front Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Do, H.D.K.; Hyun, J.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.H. Comparative analysis and implications of the chloroplast genomes of three thistles (Carduus L., Asteraceae). PeerJ 2021, 9, e10687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).