Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Deviations from the Intended Protocol

2.2. Step 1 – Identifying the Research Questions

- What are the characteristics of available evidence on diet-related variables and depression in peri- and post-menopausal women?

- What are the main findings of available evidence on diet-related variables and depression in peri- and post-menopausal women?

- What are the main research gaps on the topic of diet-related variables and depression in peri- and post-menopausal women?

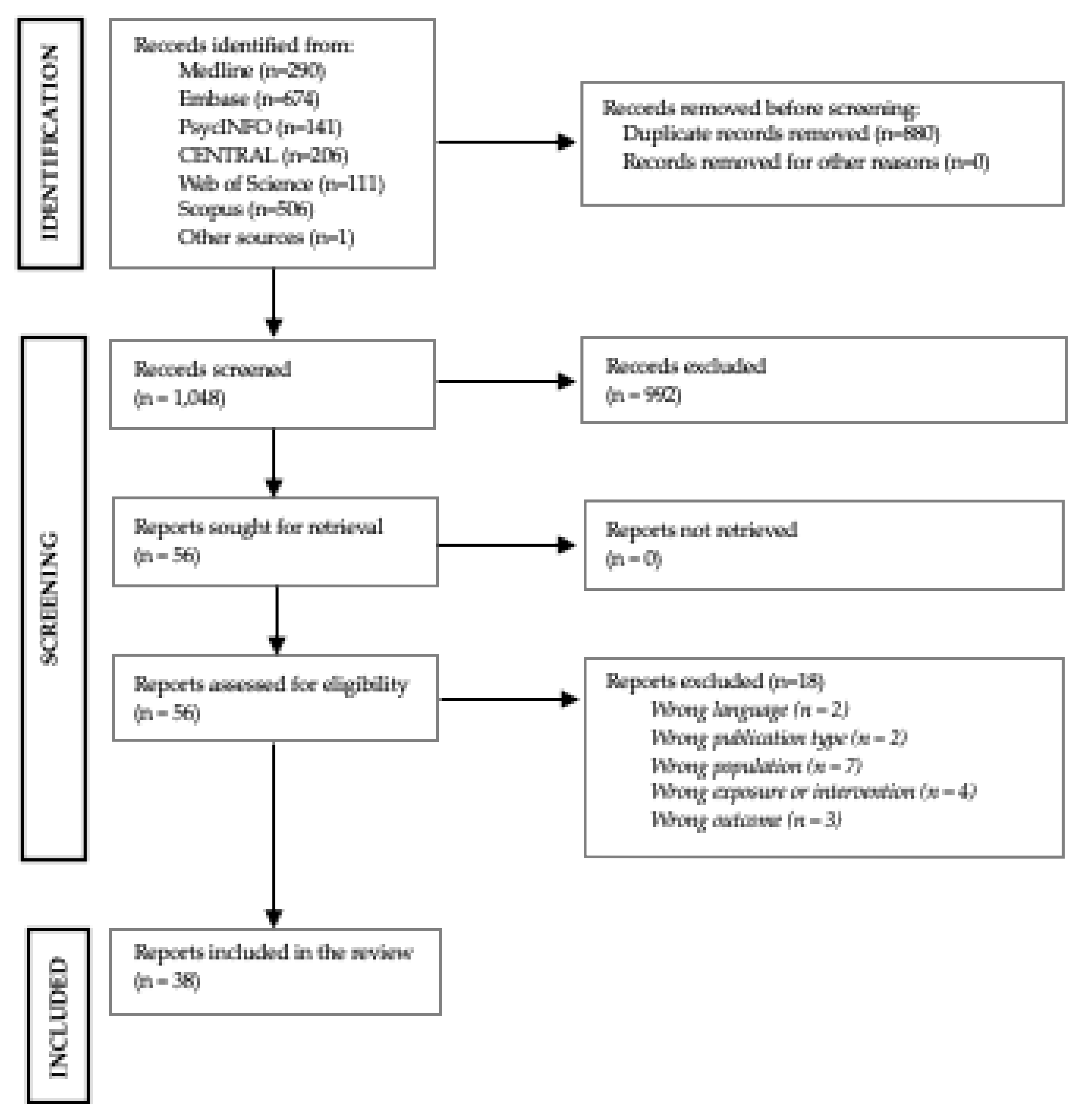

2.3. Step 2 – Identifying the Relevant Studies

2.4. Step 3 – Study Selection

2.4.1. Type of Participants

2.4.2. Type of Exposures and Interventions

2.4.3. Type of Comparators

2.4.4. Type of Outcomes

2.4.5. Type of Study Designs

2.4.6. Selection of Studies

2.5. Step 4 – Charting the Data

2.6. Step 5 – Collating, Summarizing and Reporting Results

2.7. Step 6 – Methodological Quality Appraisal

- Being at low risk of bias when all domains were rated as such;

- Raising some concerns when at least one domain was rated as such, but no domain was rated as being at high risk of bias;

- Being at high risk of bias when at least one domain was rated as such, or when multiple domains were rated as raising some concerns.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.1.1. Type of Participants

3.1.2. Type of Exposures, Interventions, and Comparators

3.1.3. Type of Outcomes

3.1.4. Type of Study Designs

3.1.5. Methodological Quality

3.2. Study of Study Findings

3.2.1. Dietary Patterns

3.2.2. Food and Food Groups

3.2.3. Macronutrients

3.2.4. Micronutrients

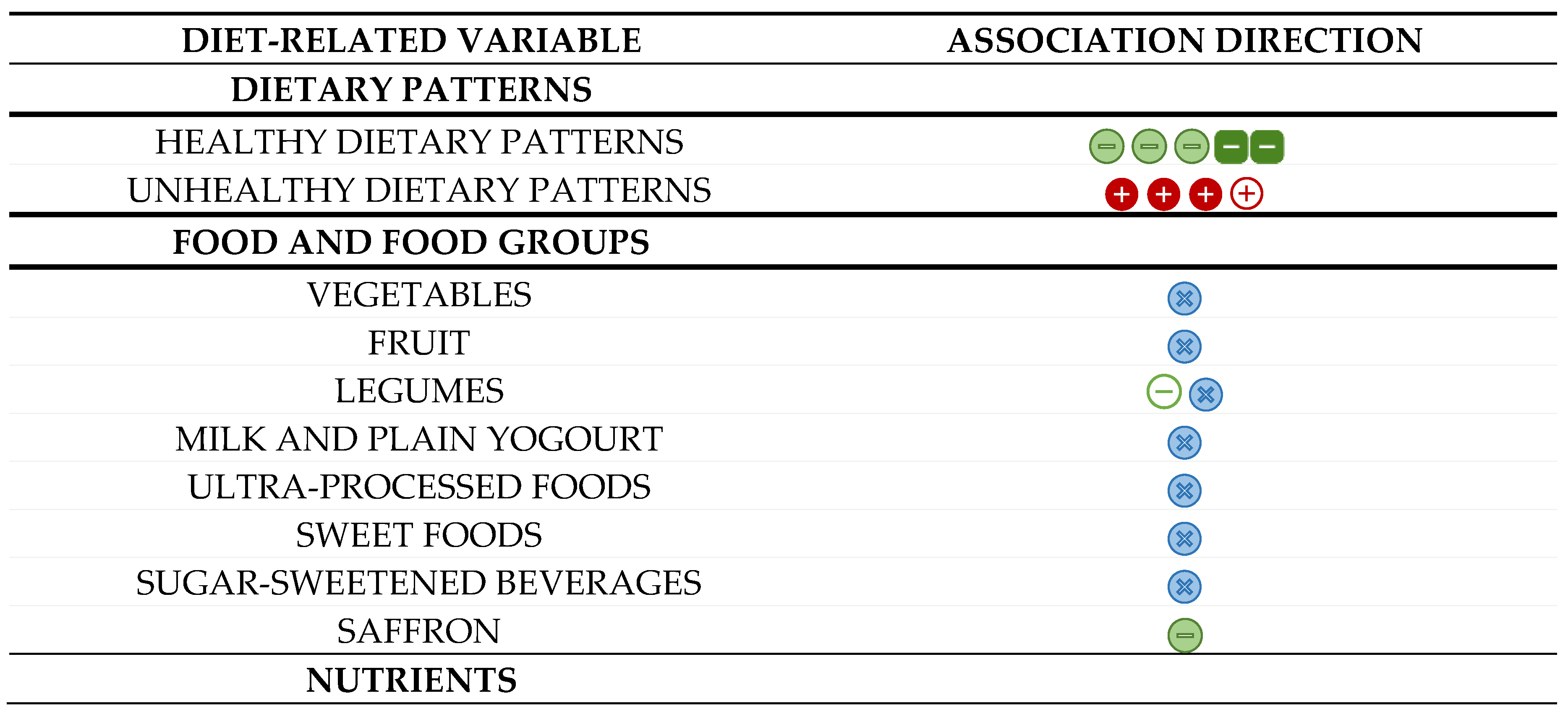

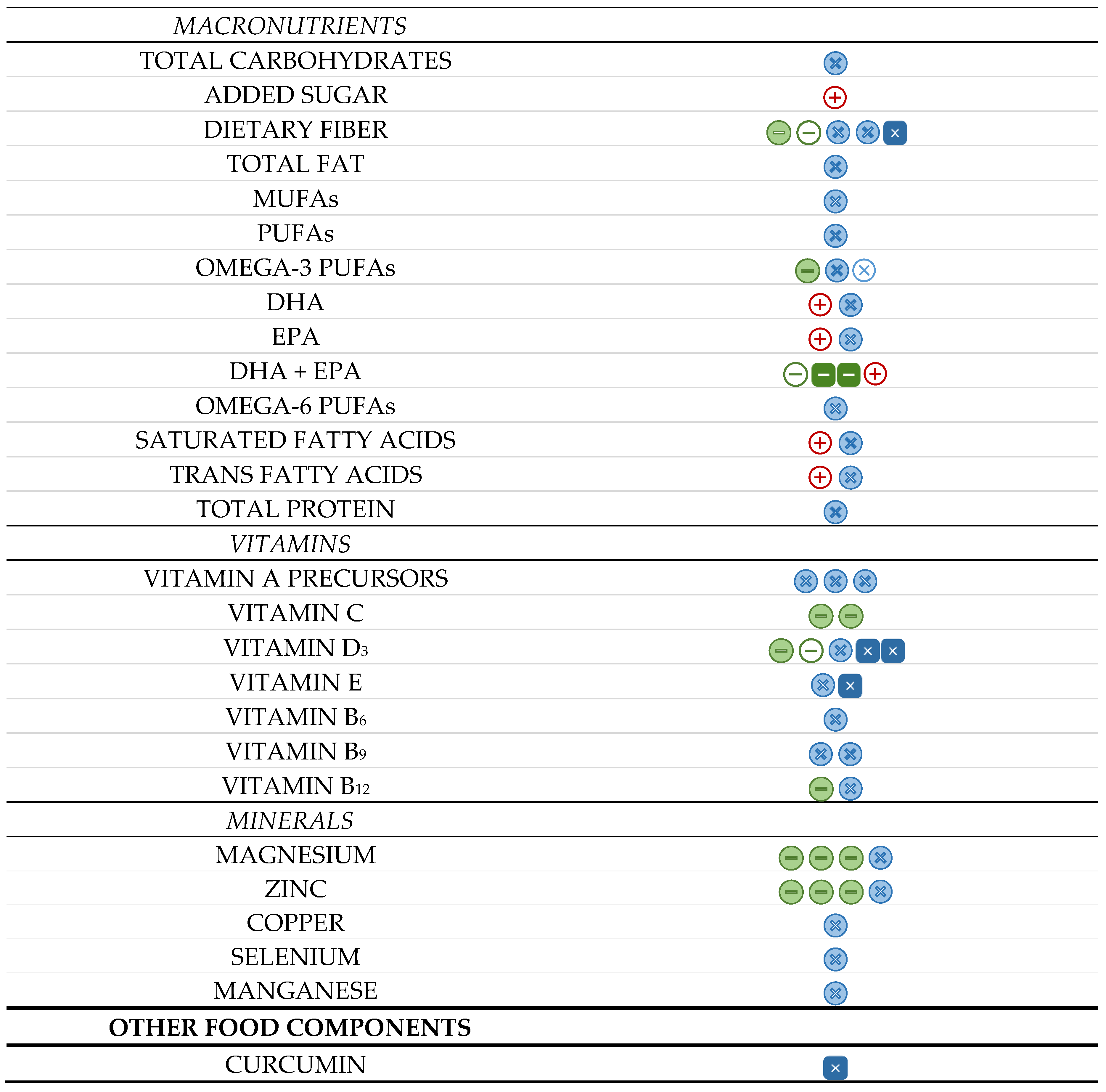

(full circles) represent cross-sectional studies,

(full circles) represent cross-sectional studies,  (empty circles) represent prospective cohort studies, and

(empty circles) represent prospective cohort studies, and  (full squares) represent experimental studies. The colours green, red and blue indicate negative (-), positive (+), and null (x) associations, respectively.

(full squares) represent experimental studies. The colours green, red and blue indicate negative (-), positive (+), and null (x) associations, respectively.

(full circles) represent cross-sectional studies,

(full circles) represent cross-sectional studies,  (empty circles) represent prospective cohort studies, and

(empty circles) represent prospective cohort studies, and  (full squares) represent experimental studies. The colours green, red and blue indicate negative (-), positive (+), and null (x) associations, respectively.

(full squares) represent experimental studies. The colours green, red and blue indicate negative (-), positive (+), and null (x) associations, respectively.

| Authors (year) Country |

Population | Exposure | Outcome | Statistical adjustments | Results | RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abshirini et al. (2019) [93] Iran |

n=175 Post-MP |

DTAC Method: FFQ (147 items) and PCA |

Depressive symptoms Method: DASS-42 |

SEC; MPS | • DTAC was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (β=-0.11, p=0.03). | 9/15

|

| Azarmanesh et al. (2022) [94] United States |

n=2,392 Post-MP |

DII Method: 24h dietary recall and DII |

Depressive symptoms Method: PHQ-9 |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors | • DII was positively associated with depressive symptoms (Q4 vs. Q1, OR: 2.1, 95%CI: 1.1–4.3). | 9/15

|

| Chae et al. (2021) [95] South Korea |

n=4,150 Post-MP |

Omega-3 PUFA intake Method: 24h dietary recall |

Depression dx or symptoms Method: Dx or NR questionnaire |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Diet | • Omega-3 PUFA intake was negatively associated with depression dx or symptoms (Q5 vs. Q1, OR: 0.52, 95%CI: 0.33–0.83). | 9/15

|

| Kim et al. (2021) [96] United States |

n=2,858 Post-MP |

Dietary fiber intake Method: 24h dietary recall |

Depressive symptoms Method: PHQ-9 |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Chronic diseases | • Dietary fiber intake was not associated with depressive symptoms. | 10/15

|

| Kostecka et al. (2022) [114] Poland |

n=191 Peri-MP |

Vit. D3 status Method: NR |

Depressive symptoms Method: BDI |

None reported | • Vit. D3 status was not associated with depressive symptoms. | 8/15

|

| Lee et al. (2023) [109] South Korea |

n=1,770 Peri/Post-MN |

Vit. B9, A and E serum levels Method: NR |

Depressive symptoms Method: PHQ-9 |

SEC; Health behaviors | • Vit. B9, A and E serum levels were not associated with depressive symptoms. | 9/15

|

| Li et al. (2020a) [76] United States |

n=1,406 Peri-MN |

Omega-3 PUFA intake Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Diet; SH | • Omega-3 PUFA intake was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (Q4 vs. Q1, OR: 0.06, 95%CI: 0.01–0.46). | 9/15

|

| Li et al. (2020b) [77] United States |

n=2,793 Pre/peri-MN |

Oleic and linoleic acid intakes Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; MPS; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors | • Oleic (Q4 vs. Q1, OR: 2.00, 95%CI: 1.30–3.06) and linoleic (Q4 vs. Q1, OR: 1.59, 95%CI: 1.05–2.42) acid intakes were positively associated with depressive symptoms, even when adjusted for MPS. | 9/15

|

| Li et al. (2020c) [78] United States |

n=1,403 Peri-MN |

TFA intake Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Diet | • TFA intake was not associated with depressive symptoms. | 9/15

|

| Li et al. (2020d) [79] United States |

n=1,359 Peri-MN |

Mn intake Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Diet; VMS | • Mn intake was not associated with depressive symptoms. | 9/15

|

| Li et al. (2020e) [80] United States |

n=1,403 Peri-MN |

Dietary fiber intake Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Diet; SH | • Dietary fiber intake was not associated with depressive symptoms. | 9/15

|

| Li et al. (2021) [81] United States |

n=1,400 Peri-MN |

β-carotene intake Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Diet; SH, VMS | • β-carotene intake was not associated with depressive symptoms. | 9/15

|

| Li et al. (2022a) [82] United States |

n=3,054 Pre/peri-MN |

Provit. A intake Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Diet; SH | • Provit. A intake was not associated with depressive symptoms, even when adjusted for MPS. | 9/15

|

| Li et al. (2022b) [83] United States |

n=3,088 Pre/peri-MN |

Vit. C intake Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; Health behaviors; Diet; Chronic diseases | • Vit. C intake was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (OR: 0.70, 95%CI: 0.52–0.93), even when adjusted for MPS. | 9/15

|

| Liao et al. (2019) [97] China |

n=2,051 Post-MP |

Dietary patterns a posteriori Method: FFQ (100 items) and PCA |

Depressive symptoms Method: ZSRDS |

SEC; Health behaviors; Diet; Chronic diseases | • The “healthy” dietary pattern was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (Q4 vs. Q1, OR: 0.57, 95%CI: 0.33–0.97). The “sweets” (Q4 vs. Q1, OR: 1.66, 95%CI: 1.03–2.71) and “traditional Tianjin” (Q4 vs. Q1, OR: 2.53, 95%CI: 1.58–4.16) dietary pattern were positively associated with depressive symptoms. |

9/15

|

| Liu et al. (2016) [98] China |

n=1,125 Post-MP |

Dietary patterns a posteriori Method: FFQ (85 items) and PCA |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; Health behaviors; Diet; Chronic diseases | • The “whole-plant food" processed food dietary pattern was positively associated with depressive symptoms (T3 vs. T1, OR: 1.79, 95%CI: 1.18–2.72). The “processed food” dietary pattern was positively associated with depressive symptoms (T3 vs. T1, OR: 1.79, 95%CI: 1.18–2.72). The “animal food” dietary pattern was not associated with depressive symptoms. |

9/15

|

| Nazari et al. (2019)* [99] Iran |

n=136 Post-MP |

Mg and Zn serum levels Method: AAS |

Depressive symptoms Method: BDI |

NR | • Zn (OR: 0.97, 95%CI: 0.96–0.99) and Mg (OR: 0.30, 95%CI: 0.15–0.61) serum levels were negatively associated with depressive symptoms. | 7/15

|

| Noll et al. (2019) [100] Brazil |

n=225 Post-MP |

Intake of 7 food groups Method: 24h dietary recall |

Depressive symptoms Method: WHQ |

SEC; MPS | • Vegetable intake was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (T2-3 vs. T1, PR: 0.65, 95%CI: 0.43–0.98). Ultra-processed food, sweet food, sugar sweetened beverage, fruit, legume, and milk and plain yogurt intakes were not associated with depressive symptoms. |

9/15

|

| Oldra et al. (2020) [110] Brazil |

n=400 Peri/post-MP |

Intake of 19 nutrients Method: 3d food diary |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

NR | • Dietary fiber, PUFA, Mg, Zn, vit. C, D3, and B12 intakes were negatively associated with depressive symptoms (p<0.05). Carbohydrate, protein, lipid, SFA, MUFA, omega-3 and omega-6 PUFA, Se, vit. B6 and B9 intakes were not associated with depressive symptoms. |

9/15

|

| Sengul et al. (2014) [101] Turkey |

n=96 Post-MP |

Serum vit. B9 and B12 levels Method: Autoanalyzer |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

NR | • Serum vit. B9 and B12 levels did not differ between women with and without depressive symptoms. | 7/15

|

| Stanislawska et al. (2014) [102] Pomeranian region |

n=171 Post-MN |

Plasma Mg and Zn levels Method: AAS |

Depressive symptoms Method: BDI |

NR | • Mg plasma levels were lower in women with mild depressive symptoms than women without (p<0.05). Zn plasma levels were lower in women with moderate depressive symptoms than women without (p<0.05). |

7/15

|

| Wieder-Huszla et al. (2020) [103] Pomeranian region |

n=102 Post-MP |

Mg, Zn, Cu, and Se serum levels Method: Mannovette system |

Depressive symptoms Method: BDI-II |

NR | • Mg, Zn, Cu, and Se serum levels were not associated with depressive symptoms. | 7/15

|

| Authors (year) Country |

Population | Exposure | Outcome | Statistical adjustments | Results | RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bertone-Johnson et al. (2011) [86] United States Study duration: 3 y |

n=81,189 Post-MP |

Vit. D3 intake Method: FFQ (122 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: 8-BS/AD use |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; HT use; Diet; Chronic diseases; Solar irradiance | • Compared to vit. D3 intakes < 100 IU, vit. D3 intakes ≥ 400 IU and < 800 IU were associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms (OR: 0.88, 95%CI: 0.79–0.97). | 13/15

|

| Colangelo et al. (2017) [104] United States Study duration: 3.2 y |

n=1,616 Post-MP |

DHA, EPA, and DHA+EPA intakes Method: FFQ (120 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D/AD use |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health Behaviors; Diet; Chronic Diseases | • DHA (Q4 vs. Q1, RR: 2.39, 95%CI: 1.45–3.39), EPA (Q4 vs. Q1, RR: 2.10, 95%CI: 1.27–3.48), and EPA+DHA (Q4 vs. Q1, RR: 2.04, 95%CI: 1.24–3.37) intakes were positively associated with depressive symptoms. | 12/15

|

| Gangwisch et al. (2015) [87] United States Study duration: 3 y |

n=69,954 Post-MP |

Dietary glycemic index Added sugar intake Dietary fiber intake Method: FFQ (145 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: 8-BS/AD use |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Social support; Stressful life events; HT use; Diet; Chronic diseases | • Dietary glycemic index (Q5 vs. Q1, OR: 1.22, 95%CI: 1.09–1.37) and added sugar intake (Q5 vs. Q1, OR: 1.23, 95%CI: 1.07–1.41) were positively associated with depressive symptoms. Dietary fiber intake was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (Q5 vs. Q1, OR: 0.86, 95%CI: 0.76–0.98). |

13/15

|

| Li et al. (2010) [102,111] United States Study duration: 10.6 y |

n=1,005 Peri/Post-MP |

Weekly legume intake Method: FFQ |

Severe depressed mood Method: CES-D/AD use |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Diet; Food Allergies; Chronic diseases | • In peri-MP women, only moderate (1-2x/wk) vs. infrequent (<1x/wk) legume intake was associated with a lower risk of severe depressed mood (RR: 0.52, 95%CI: 0.27–1.00). In post-MP women, weekly legume consumption was not associated with severe depressed mood. |

12/15

|

| Li et al. (2020f) [84] United States Study duration: 5 y |

n=2,376 Pre/Post-MP |

SFA intake Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

SEC; Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Chronic stress; AD use; Diet; VMS; SH | • SFA intake was positively associated with depressive symptoms (Q4 vs. Q1, OR: 2.61, 95%CI: 1.15 – 5.93), even when adjusted for MPS. | 12/15

|

| Li et al. (2020g) [85] United States Study duration: 5 y |

n=2,376 Pre/Post-MP |

TFA intake Method: FFQ (103 items) |

Depressive symptoms Method: CES-D |

Anthropometrics; Health behaviors; Chronic stress; AD use; Diet; SH | • TFA intake was positively associated with depressive symptoms (Q4 vs. Q1, OR: 1.64, 95%CI: 1.09–2.47), even when adjusted for MPS. | 12/15

|

| Persons et al. (2014) [88] United States Study duration: 3 y |

n=7,066 Post-MP |

Omega-3 PUFA intake DHA, EPA, DHA+EPA intakes RBC omega-3 PUFAs, DHA, and EPA Methods: FFQ (120 items; intake) NR (RBC) |

Depressive symptoms Method: 8-BS/AD use |

SEC; Health behaviors; HT use; Bilateral oophorectomy; Chronic diseases | • Omega-3 PUFA, DHA, and EPA intakes were not associated with depressive symptoms. DHA+EPA intakes were negatively associated with depressive symptoms (T3 vs. T1, OR: 0.71, 95%CI: 0.50–0.99). RBC omega-3 PUFA, DHA, EPA, and DHA+EPA levels were not associated with depressive symptoms. |

13/15

|

| Authors (year) Country |

Study design | Population | Interventions | Outcome | Results | RoB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | ||||||

| Assaf et al. (2016) [90] United States |

Open-label RCT Duration: 1 y n=48,834 |

Post-MP | Low-fat diet | No intervention | Depressive symptoms Method: Modified CES-D |

• The low-fat diet (vs. no intervention) significant decreased depressive symptoms (MD: 0.07, 95%CI: 0.02 – 0.12). | High

|

| Bertone-Johnson et al. (2012) [89] United States |

TB-RCT Duration: 3 y n=36,282 |

Post-MP | Daily vit. D3 (400 IU) + Ca (1,000 mg) supplement capsules | Placebo capsule | Depressive symptoms Method: 8-BS/AD use |

• No significant difference was observed between the effects of the experimental and the control interventions. | High

|

| Farshbaf-Khalili et al. (2022) [105] Iran |

TB-RCT Duration: 8 wks n=81 |

Post-MP |

Experimental intervention #1: Daily curcumin (1,000 mg) supplement capsules Experimental intervention #2: Daily vit. E (1,000 mg) supplement capsules |

Placebo capsule | Depressive symptoms Method: GCS |

• While all interventions decreased depressive symptoms from pre- to post-intervention, no significant differences were observed between their individual effects. | Low

|

| Freeman et al. (2011) [92] United States |

Pre-Post NEGD Duration: 8 wks n=20 |

Peri/Post-MP | Daily ethyl-DHA (375 mg) + EPA (465 mg) supplement capsules | None | Depressive symptoms Method: MADRS |

• The intervention decreased depressive symptoms from pre- to post-intervention (MD: -12.0, SD: 8.3, p<0.0001). | High

|

| Kashani et al. (2018) [106] Iran |

DB-RCT Duration: 6 wks n=56 |

Post-MP | Daily saffron (30 mg) supplement capsules | Placebo capsule | Depressive symptoms Method: HDRS |

• The experimental intervention (vs. control) significantly decreased depressive symptoms (SMD: 19.6, 95%CI: 9.00–30.28, p=0.001). | High

|

| Lucas et al. (2009) [112] Canada |

TB-RCT Duration: 8 wks n=120 |

Peri/Post-MP | Daily ethyl-DHA (150 mg) + EPA (1,005 mg) supplement capsules | Placebo capsule | Depressive symptoms Method: HSCL-D-2 and HDRS-21 |

• The experimental intervention (vs. control) significantly decreased depressive symptoms when assessed with the HSCL-D-20 (SMD: -0.85 vs. -0.50 with placebo, p<0.05) and the HDRS-21 (SMD: -0.74 vs. -0.38 with placebo, p<0.05). These effects were however restricted to women without a major depressive episode at baseline (n=91). | Low

|

| Mason et al. (2016) [107] United States |

TB-RCT Duration: 1 y n=218 |

Post-MP | Daily vit. D3 (2,000 IU) supplement capsules | Placebo capsule | Depressive symptoms Method: BSI-18 |

• No significant difference was observed between the effects of the experimental and the control interventions. | Low

|

| Shafie et al. (2022) [73] Iran |

TB-RCT Duration: 6 wks n=60 |

Peri/Post-MP | Prebiotic-enriched yoghurt | Regular yoghurt placebo | Depressive symptoms Method: DASS-21 |

• No significant difference was observed between the effects of the experimental and the control interventions. | Low

|

| Torres et al. (2012) [108] Australia |

Open-label RCT Duration: 14 wks n=95 |

Post-MP |

Experimental intervention #1: DASH diet Experimental intervention #2: Low-fat diet |

None | Depressive symptoms Method: 37-item POMS |

• Both the DASH diet (MD: -1.1, SEM: 0.8, p<0.01) and the low-fat diet (MD: -0.6, SEM: 0.4, p<0.01) decreased depressive symptoms from pre- to post-intervention, but no significant difference was observed between their individual effects. | High |

3.2.5. Other Food Components

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Study Findings

4.2. Findings in Relation to Other Studies

4.3. Strenghts and Limitations of the Evidence

4.4. Strenghts and Limitations of the Review

4.5. Research Gaps and Future Directions

4.6. Implications for Research and Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BDI | Beck’s Depression Inventory |

| BS | Burnam Scale |

| BSI | Brief Symptom Inventory |

| CENTRAL | Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials |

| CES-D | Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

| DASH | Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension |

| DASS | Depression Anxiety Stress Scale |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| DII | Dietary Inflammatory Index |

| DTAC | Dietary Total Antioxidant Capacity |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| GCS | Greene Climacteric Scale |

| HDRS | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal |

| HSCL-D | Hopkins Symptoms Checklist Depression Scale |

| MADRS | Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| MUFA(s) | Monounsaturated Fatty Acid(s) |

| NEGD | Non-Equivalent Groups Design |

| NHLBI | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| POMS | Profile of Mood State |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews Meta-Analyses |

| PRISMA-ScR | PRISMA Checklist’s Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| PUFA(s) | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid(s) |

| RCT(s) | Randomized controlled trial(s) |

| RoB | Risk of Bias |

| SFA(s) | Saturated Fatty Acid(s) |

| SWAN | Studies of Women’s Health Across the Nation |

| TFA(s) | Trans Fatty Acid(s) |

| WHI | Women’s Health Initiative |

| WHQ | Women’s Health Questionnaire |

| ZSRDS | Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale |

References

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Burden of 12 Mental Disorders in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlantis, E.; Fahey, P.; Cochrane, B.; Smith, S. Bidirectional Associations Between Clinically Relevant Depression or Anxiety and COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 2013, 144, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luppino, F.S.; de Wit, L.M.; Bouvy, P.F.; Stijnen, T.; Cuijpers, P.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Zitman, F.G. Overweight, Obesity, and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010, 67, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotella, F.; Mannucci, E. Depression as a Risk Factor for Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2013, 74, 4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seabury, S.A.; Axeen, S.; Pauley, G.; Tysinger, B.; Schlosser, D.; Hernandez, J.B.; Heun-Johnson, H.; Zhao, H.; Goldman, D.P. Measuring The Lifetime Costs Of Serious Mental Illness And The Mitigating Effects Of Educational Attainment. 2019, 38, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insel, T.R. Assessing the Economic Costs of Serious Mental Illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 2008, 165, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salk, R.H.; Hyde, J.S.; Abramson, L.Y. Gender Differences in Depression in Representative National Samples: Meta-Analyses of Diagnoses and Symptoms. Psychol Bull 2017, 143, 783–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douma, S.L.; Husband, C.; O’Donnell, M.E.; Barwin, B.N.; Woodend, A.K. Estrogen-Related Mood Disorders: Reproductive Life Cycle Factors. Advances in Nursing Science 2005, 28, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Seong, S.J.; Ryu, J.M.; Cho, M.J. Prevalence, Work-Loss Days and Quality of Life of Community Dwelling Subjects with Depressive Symptoms. J Korean Med Sci 2013, 28, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Petukhova, M.; Vilagut, G.; Chatterji, S.; Heeringa, S.; Üstün, T.B.; Alhamzawi, A.O.; Viana, M.C.; Angermeyer, M.; Bromet, E.; et al. Days out of Role Due to Common Physical and Mental Conditions: Results from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Molecular Psychiatry 2011 16:12 2010, 16, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, D.; Adler, D.A.; Chang, H.; Lapitsky, L.; Hood, M.Y.; Perissinotto, C.; Reed, J.; McLaughlin, T.J.; Berndt, E.R.; Rogers, W.H. Unemployment, Job Retention, and Productivity Loss among Employees with Depression. Psychiatric Services 2004, 55, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.; Crain, L.A.; Solberg, L.I.; Unützer, J.; Maciosek, M. v.; Whitebird, R.R.; Rossom, R.C. Does Severity of Depression Predict Magnitude of Productivity Loss? Am J Manag Care 2014, 20, e294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woods, N.F.; Smith-DiJulio, K.; Percival, D.B.; Tao, E.Y.; Mariella, A.; Mitchell, E.S. Depressed Mood during the Menopausal Transition and Early Postmenopause: Observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause 2008, 15, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, M.; Schoenaker, D.A.J.M.; Joffe, H.; Mishra, G.D. Depressive Symptoms across the Menopause Transition: Findings from a Large Population-Based Cohort Study. Menopause 2016, 23, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.S.; Soares, C.N.; Vitonis, A.F.; Otto, M.W.; Harlow, B.L. Risk for New Onset of Depression During the Menopausal Transition: The Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006, 63, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, E.W. Associations of Depression with the Transition to Menopause. Menopause 2010, 17, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.W.; Sammel, M.D.; Lin, H.; Nelson, D.B. Associations of Hormones and Menopausal Status With Depressed Mood in Women With No History of Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006, 63, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberger, J.T.; Schott, L.; Kravitz, H.M.; Joffe, H. Risk Factors for Major Depression during Midlife among a Community Sample of Women with and without Prior Major Depression: Are They the Same or Different? Psychol Med 2015, 45, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberger, J.T.; Kravitz, H.M.; Chang, Y.F.; Cyranowski, J.M.; Brown, C.; Matthews, K.A. Major Depression during and after the Menopausal Transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Psychol Med 2011, 41, 1879–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Kruif, M.; Spijker, A.T.; Molendijk, M.L. Depression during the Perimenopause: A Meta-Analysis. J Affect Disord 2016, 206, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H.; De Wit, A.; Coborn, J.; Crawford, S.; Freeman, M.; Wiley, A.; Athappilly, G.; Kim, S.; Sullivan, K.A.; Cohen, L.S.; et al. Impact of Estradiol Variability and Progesterone on Mood in Perimenopausal Women With Depressive Symptoms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105, e642–e650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, Z.; Lee, S.; Kulkarni, J. The Unique Symptom Profile of Perimenopausal Depression. 2020, 19, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J.; Gavrilidis, E.; Hudaib, A.R.; Bleeker, C.; Worsley, R.; Gurvich, C. Development and Validation of a New Rating Scale for Perimenopausal Depression—the Meno-D. Translational Psychiatry 2018 8:1 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thase, M.E.; Entsuah, R.; Cantillon, M.; Kornstein, S.G. Relative Antidepressant Efficacy of Venlafaxine and SSRIs: Sex-Age Interactions. https://home.liebertpub.com/jwh 2005, 14, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sell, S.L.; Craft, R.M.; Seitz, P.K.; Stutz, S.J.; Cunningham, K.A.; Thomas, M.L. Estradiol–Sertraline Synergy in Ovariectomized Rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2008, 33, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Récamier-Carballo, S.; Estrada-Camarena, E.; Reyes, R.; Fernández-Guasti, A. Synergistic Effect of Estradiol and Fluoxetine in Young Adult and Middle-Aged Female Rats in Two Models of Experimental Depression. Behavioural Brain Research 2012, 233, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziottin, A.; Serafini, A. Depression and the Menopause: Why Antidepressants Are Not Enough? 2009, 15, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Marx, W.; Dash, S.; Carney, R.; Teasdale, S.B.; Solmi, M.; Stubbs, B.; Schuch, F.B.; Carvalho, A.F.; Jacka, F.; et al. The Effects of Dietary Improvement on Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychosom Med 2019, 81, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguacel, I.; Huybrechts, I.; Moreno, L.A.; Michels, N. Vegetarianism and Veganism Compared with Mental Health and Cognitive Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr Rev 2021, 79, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, M.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, T.; Li, Z. Dietary Inflammatory Potential and the Incidence of Depression and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. J Health Popul Nutr 2022, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzozero-Peroni, B.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Fernández-Rodríguez, R.; Jiménez-López, E.; Núñez de Arenas-Arroyo, S.; Saz-Lara, A.; Díaz-Goñi, V.; Mesas, A.E. The Impact of the Mediterranean Diet on Alleviating Depressive Symptoms in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr Rev 2024, 83, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, S.; Sangsefidi, Z.S.; Asoudeh, F.; Torabynasab, K.; Zeraattalab-Motlagh, S.; Hejazi, M.; Khalighi Sikaroudi, M.; Meshkini, F.; Razmpoosh, E.; Abdollahi, S. Effect of Low-Fat Diet on Depression Score in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Nutr Rev 2025, 83, e741–e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Travica, N.; Dissanayaka, T.; Ashtree, D.N.; Gauci, S.; Lotfaliany, M.; O’neil, A.; Jacka, F.N.; Marx, W. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazloomi, S.N.; Talebi, S.; Mehrabani, S.; Bagheri, R.; Ghavami, A.; Zarpoosh, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Wong, A.; Nordvall, M.; Kermani, M.A.H.; et al. The Association of Ultra-Processed Food Consumption with Adult Mental Health Disorders: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of 260,385 Participants. Nutr Neurosci 2023, 26, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werneck, A.O.; Steele, E.M.; Delpino, F.M.; Lane, M.M.; Marx, W.; Jacka, F.N.; Stubbs, B.; Touvier, M.; Srour, B.; Louzada, M.L.; et al. Adherence to the Ultra-Processed Dietary Pattern and Risk of Depressive Outcomes: Findings from the NutriNet Brasil Cohort Study and an Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical Nutrition 2024, 43, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejtahed, H.S.; Mardi, P.; Hejrani, B.; Mahdavi, F.S.; Ghoreshi, B.; Gohari, K.; Heidari-Beni, M.; Qorbani, M. Association between Junk Food Consumption and Mental Health Problems in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, C.A.; Freitas, T.H.; Maes, M.; de Andrade, N.Q.; Liu, C.S.; Fernandes, B.S.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Herrmann, N.; et al. Peripheral Cytokine and Chemokine Alterations in Depression: A Meta-Analysis of 82 Studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017, 135, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, D.R.; Rapaport, M.H.; Miller, B.J. A Meta-Analysis of Blood Cytokine Network Alterations in Psychiatric Patients: Comparisons between Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder and Depression. Mol Psychiatry 2016, 21, 1696–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, D.; Pariante, C.M.; Mondelli, V. Markers of Central Inflammation in Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Examining Cerebrospinal Fluid, Positron Emission Tomography and Post-Mortem Brain Tissue. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 81, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhong, S.; Liao, X.; Chen, J.; He, T.; Lai, S.; Jia, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Oxidative Stress Markers in Depression. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0138904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Fernandez, S.; Gurpegui, M.; Diaz-Atienza, F.; Perez-Costillas, L.; Gerstenberg, M.; Correll, C.U. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Parameters in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Compared to Healthy Controls Before and After Antidepressant Treatment: Results From a Meta-Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2015, 76, 13705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, C.N.; Bot, M.; Scheffer, P.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Is Depression Associated with Increased Oxidative Stress? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 51, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetler, C.; Miller, G.E. Depression and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Activation: A Quantitative Summary of Four Decades of Research. Psychosom Med 2011, 73, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Duran, N.L.; Kovacs, M.; George, C.J. Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis Dysregulation in Depressed Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.Y.; Tseng, P.T. Decreased Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Levels in Patients with Depression: A Meta-Analytic Study. J Psychiatr Res 2015, 63, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Duman, R.; Sanacora, G. Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, Depression, and Antidepressant Medications: Meta-Analyses and Implications. Biol Psychiatry 2008, 64, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirkhanzadeh Barandouzi, Z.; Starkweather, A.R.; Henderson, W.A.; Gyamfi, A.; Cong, X.S. Altered Composition of Gut Microbiota in Depression: A Systematic Review. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C.A.; Diaz-Arteche, C.; Eliby, D.; Schwartz, O.S.; Simmons, J.G.; Cowan, C.S.M. The Gut Microbiota in Anxiety and Depression – A Systematic Review. Clin Psychol Rev 2021, 83, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zonneveld, S.M.; van den Oever, E.J.; Haarman, B.C.M.; Grandjean, E.L.; Nuninga, J.O.; van de Rest, O.; Sommer, I.E.C. An Anti-Inflammatory Diet and Its Potential Benefit for Individuals with Mental Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Ju, T.; Zeng, D.; Duan, F.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, W. “Inflamed” Depression: A Review of the Interactions between Depression and Inflammation and Current Anti-Inflammatory Strategies for Depression. Pharmacol Res 2024, 207, 107322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2007, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodnaruc, A.M.; Duquet, M.; Prud’homme, D.; Giroux, I. Diet and Depression during Peri- and Post-Menopause: A Scoping Review Protocol. Methods Protoc 2023, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.; Elbers, R. Chapter 8: Assessing Risk of Bias in a Randomized Trial [Last Updated 19]. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5; Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M., Welch, V., Eds.; Cochrane, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. 2014.

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Quality Assessment of Case-Control Studies.

- Jokar, A.; Farahi, F. Effect of Vitamin C on Depression in Menopausal Women with Balanced Diet: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility 2014, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahraeini, M.; Shourab, N.J.; Javan, R.; Shakeri, M.T. Effect of Food-Based Strategies of Iranian Traditional Medicine on Women’s Quality of Life during Menopause. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility 2021, 23, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chocano-Bedoya, P.; O’Reilly, E.; Lucas, M.; Mirzaei, F.; Okereke, O.; Fung, T.; Hu, F.; Ascherio, A. Dietary Patterns and Depression in the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2012, 175, S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasco, J.A.; Williams, L.J.; Brennan-Olsen, S.L.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F.N. Milk Consumption and the Risk for Incident Major Depressive Disorder. Psychother Psychosom 2015, 84, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, G.B.; Khedkar, A.; Flaws, J.A.; Sorkin, J.D.; Gallicchio, L. Depressive Symptoms and Self-Reported Fast-Food Intake in Midlife Women. Prev Med (Baltim) 2011, 52, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.J.; Kim, S.K. Low Dietary Calcium Is Associated with Self-Rated Depression in Middle-Aged Korean Women. Nutr Res Pract 2012, 6, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivappa, N.; Schoenaker, D.A.J.M.; Hebert, J.R.; Mishra, G.D. Association between Inflammatory Potential of Diet and Risk of Depression in Middle-Aged Women: The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. British Journal of Nutrition 2016, 116, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odai, T.; Terauchi, M.; Suzuki, R.; Kato, K.; Hirose, A.; Miyasaka, N. Depressive Symptoms in Middle-Aged and Elderly Women Are Associated with a Low Intake of Vitamin B6: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, D.K.; Kim, B.; Na, K.S.; Lee, C.H.; Son, Y.D.; Lee, H.J. The Association between Omega-3 Fatty Acid Intake and Human Brain Connectivity in Middle-Aged Depressed Women. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, J.; Seong, Y.; Choi, Y.; Kim, Y.; Cho, M.S.; Ha, E.; Kwon, O.; Kim, Y.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, Y. Meal-Based Intervention on Health Promotion in Middle-Aged Women: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2023, Vol. 15, Page 2108 2023, 15, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Park, S.J.; Lee, H.J. Healthy and Unhealthy Dietary Patterns of Depressive Symptoms in Middle-Aged Women. Nutrients 2024, 16, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carels, R.A.; Darby, L.A.; Cacciapaglia, H.M.; Douglass, O.M. Reducing Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Postmenopausal Women through a Lifestyle Change Intervention. J Womens Health 2004, 13, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, S.; Mustata, C.; Rizo, J.M.; Regidor, P.A. Improvement in Menopausal Symptoms with a Nutritional Product Containing Evening Primrose Oil, Hop Extract, Saffron, Tryptophan, Vitamins B6, D3, K2, B12, and B9. European Review of Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2023, 27, 8180–8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachko, V.A.; Shulman, L.P.; Kuznetsova, I. V.; Uspenskaya, Y.B.; Burchakov, D.I. Clinical Evaluation of Effectiveness and Safety of Combined Use of Dietary Supplements Amberen® and Smart B® in Women with Climacteric Syndrome in Perimenopause. Adv Ther 2024, 41, 3183–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, J.; He, D.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X. Association between Different Triglyceride Glucose Index-Related Indicators and Depression in Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Women: NHANES, 2013–2016. J Affect Disord 2024, 360, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, M.; Homayouni Rad, A.; Mirghafourvand, M. Effects of Prebiotic-Rich Yogurt on Menopausal Symptoms and Metabolic Indices in Menopausal Women: A Triple-Blind Randomised Controlled Trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2022, 73, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, N.; Baharanchi, F.H.; Melekoglu, E.; Sohouli, M.H.; Shidfar, F. Comparison of Predictive Effect of the Dietary Inflammatory Index and Empirically Derived Food-Based Dietary Inflammatory Index on the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life and Its Complications. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abshirini, M.; Siassi, F.; Koohdani, F.; Qorbani, M.; Khosravi, S.; Hedayati, M.; Aslani, Z.; Soleymani, M.; Sotoudeh, G. Dietary Total Antioxidant Capacity Is Inversely Related to Menopausal Symptoms: A Cross-Sectional Study among Iranian Postmenopausal Women. Nutrition 2018, 55–56, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liang, H.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. Association of Dietary N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Intake with Depressive Symptoms in Midlife Women. J Affect Disord 2020, 261, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. Associations between Dietary Oleic Acid and Linoleic Acid and Depressive Symptoms in Perimenopausal Women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Nutrition 2020, 71, 110602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. Associations of Dietary Trans Fatty Acid Intake with Depressive Symptoms in Midlife Women. J Affect Disord 2020, 260, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, Q.; Xu, W.; Zheng, H.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. Dietary Manganese Intake Is Inversely Associated with Depressive Symptoms in Midlife Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Affect Disord 2020, 276, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. Dietary Fiber Is Inversely Associated With Depressive Symptoms in Premenopausal Women. Front Neurosci 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, Q.; Tong, Y.; Zheng, H.; Li, Y. Dietary Beta-Carotene Intake Is Inversely Associated with Anxiety in US Midlife Women. J Affect Disord 2021, 287, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zheng, H.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. Associations of Dietary Provitamin A Carotenoid Intake with Depressive Symptoms in Midlife Women: Results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Affect Disord 2022, 317, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, W.; Wu, Q.; Zheng, H.; Li, Y. Ascorbic Acid Intake Is Inversely Associated with Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms in US Midlife Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Affect Disord 2022, 299, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liang, H.; Tong, Y.; Zheng, H.; Li, Y. Association between Saturated Fatty Acid Intake and Depressive Symptoms in Midlife Women: A Prospective Study. J Affect Disord 2020, 267, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Zheng, H.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. Prospective Association between Trans Fatty Acid Intake and Depressive Symptoms: Results from the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation. J Affect Disord 2020, 264, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Powers, S.I.; Spangler, L.; Brunner, R.L.; Michael, Y.L.; Larson, J.C.; Millen, A.E.; Bueche, M.N.; Salmoirago-Blotcher, E.; Liu, S.; et al. Vitamin D Intake from Foods and Supplements and Depressive Symptoms in a Diverse Population of Older Women. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 94, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwisch, J.E.; Hale, L.; Garcia, L.; Malaspina, D.; Opler, M.G.; Payne, M.E.; Rossom, R.C.; Lane, D. High Glycemic Index Diet as a Risk Factor for Depression: Analyses from the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr 2015, 102, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persons, J.E.; Robinson, J.G.; Ammann, E.M.; Coryell, W.H.; Espeland, M.A.; Harris, W.S.; Manson, J.E.; Fiedorowicz, J.G. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Biomarkers and Subsequent Depressive Symptoms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014, 29, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Powers, S.I.; Spangler, L.; Larson, J.; Michael, Y.L.; Millen, A.E.; Bueche, M.N.; Salmoirago-Blotcher, E.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Brunner, R.L.; et al. Vitamin D Supplementation and Depression in the Women’s Health Initiative Calcium and Vitamin D Trial. Am J Epidemiol 2012, 176, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.R.; Beresford, S.A.A.; Risica, P.M.; Aragaki, A.; Brunner, R.L.; Bowen, D.J.; Naughton, M.; Rosal, M.C.; Snetselaar, L.; Wenger, N. Low-Fat Dietary Pattern Intervention and Health-Related Quality of Life: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. J Acad Nutr Diet 2016, 116, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, D.; Antoine, S.L.; Mathes, T.; Neugebauer, E.A.M.; Eikermann, M. Systematic Review Finds Overlapping Reviews Were Not Mentioned in Every Other Overview. J Clin Epidemiol 2014, 67, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M.P.; Hibbeln, J.R.; Silver, M.; Hirschberg, A.M.; Wang, B.; Yule, A.M.; Petrillo, L.F.; Pascuillo, E.; Economou, N.I.; Joffe, H.; et al. Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Major Depressive Disorder Associated with the Menopausal Transition: A Preliminary Open Trial. Menopause 2011, 18, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abshirini, M.; Siassi, F.; Koohdani, F.; Qorbani, M.; Mozaffari, H.; Aslani, Z.; Soleymani, M.; Entezarian, M.; Sotoudeh, G. Dietary Total Antioxidant Capacity Is Inversely Associated with Depression, Anxiety and Some Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Postmenopausal Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2019, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarmanesh, D.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Pearlman, J.; Liu, Z.; Carbone, E.T. Association of the Dietary Inflammatory Index with Depressive Symptoms among Pre-and Post-Menopausal Women: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2010. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, M.; Park, K. Association between Dietary Omega-3 Fatty Acid Intake and Depression in Postmenopausal Women. Nutr Res Pract 2021, 15, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Hong, M.; Kim, S.; Shin, W.Y.; Kim, J.H. Inverse Association between Dietary Fiber Intake and Depression in Premenopausal Women: A Nationwide Population-Based Survey. Menopause 2021, 28, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, K.; Gu, Y.; Liu, M.; Fu, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Meng, G.; Yao, Z.; et al. Association of Dietary Patterns with Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Postmenopausal Women. British Journal of Nutrition 2019, 122, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.M.; Ho, S.C.; Xie, Y.J.; Chen, Y.J.; Chen, Y.M.; Chen, B.; Yeung-Shan Wong, S.; Chan, D.; Ka Man Wong, C.; He, Q.; et al. Associations between Dietary Patterns and Psychological Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study among Chinese Postmenopausal Women. Menopause 2016, 23, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, F.; Hekmat, K.; Iravani, M.; Haghighizadeh, M.H.; Boostani, H. The Relationship Between Serum Zinc and Magnesium Levels and Depression in Postmenopausal Women. J Biochem Technol 2019, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Noll, P.R. e. S.; Noll, M.; Zangirolami-Raimundo, J.; Baracat, E.C.; Louzada, M.L. da C.; Soares Júnior, J.M.; Sorpreso, I.C.E. Life Habits of Postmenopausal Women: Association of Menopause Symptom Intensity and Food Consumption by Degree of Food Processing. Maturitas 2022, 156, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengül, Ö.; Uygur, D.; Güleç, M.; Dilbaz, B.; Şimşek, E.M.; Göktolga, Ü. The Comparison of Folate and Vitamin B12 Levels between Depressive and Nondepressive Postmenopausal Women. Turk J Med Sci 2014, 44, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisławska, M.; Szkup-Jabłońska, M.; Jurczak, A.; Wieder-Huszla, S.; Samochowiec, A.; Jasiewicz, A.; Noceń, I.; Augustyniuk, K.; Brodowska, A.; Karakiewicz, B.; et al. The Severity of Depressive Symptoms vs. Serum Mg and Zn Levels in Postmenopausal Women. Biol Trace Elem Res 2014, 157, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder-Huszla, S.; Zabielska, P.; Kotwas, A.; Owsianowska, J.; Karakiewicz-Krawczyk, K.; Kowalczyk, R.; Jurczak, A. The Severity of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Postmenopausal Women Depending on Their Magnesium, Zinc, Selenium and Copper Levels. J Elem 2020, 25, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangelo, L.A.; Ouyang, P.; Golden, S.H.; Szklo, M.; Gapstur, S.M.; Vaidya, D.; Liu, K. Do Sex Hormones or Hormone Therapy Modify the Relation of N-3 Fatty Acids with Incident Depressive Symptoms in Postmenopausal Women? The MESA Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 75, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farshbaf-Khalili, A.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Ataei-Almanghadim, K.; Dousti, S.; Iranshahi, A.M. Clinical Efficacy of Curcumin and Vitamin e on Inflammatory-Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and Primary Symptoms of Menopause in Healthy Postmenopausal Women: A Triple-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Nutr Metab 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, L.; Esalatmanesh, S.; Eftekhari, F.; Salimi, S.; Foroughifar, T.; Etesam, F.; Safiaghdam, H.; Moazen-Zadeh, E.; Akhondzadeh, S. Efficacy of Crocus Sativus (Saffron) in Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder Associated with Post-Menopausal Hot Flashes: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2018, 297, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; de Dieu Tapsoba, J.; Duggan, C.; Wang, C.Y.; Korde, L.; McTiernan, A. Repletion of Vitamin D Associated with Deterioration of Sleep Quality among Postmenopausal Women. Prev Med (Baltim) 2016, 93, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, S.J.; Nowson, C.A. A Moderate-Sodium DASH-Type Diet Improves Mood in Postmenopausal Women. Nutrition 2012, 28, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Baek, J.C. Serum Vitamin Levels, Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors, and Their Association with Depression in Korean Women: A Cross-Sectional Study of a Nationally Representative Sample. Medicina (B Aires) 2023, 59, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldra, C.M.; Benvegnú, D.M.; Silva, D.R.P.; Wendt, G.W.; Vieira, A.P. Relationships between Depression and Food Intake in Climacteric Women. Climacteric 2020, 23, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dai, Q.; Tedders, S.H.; Arroyo, C.; Zhang, J. Legume Consumption and Severe Depressed Mood, the Modifying Roles of Gender and Menopausal Status. Public Health Nutr 2010, 13, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.; Asselin, G.; Mérette, C.; Poulin, M.J.; Dodin, S. Ethyl-Eicosapentaenoic Acid for the Treatment of Psychological Distress and Depressive Symptoms in Middle-Aged Women: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2009, 89, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, M.; Homayouni Rad, A.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Mirghafourvand, M. The Effect of Probiotics on Mood and Sleep Quality in Postmenopausal Women: A Triple-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2022, 50, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecka, D.; Schneider-Matyka, D.; Barczak, K.; Starczewska, M.; Szkup, M.; Ustianowski, P.; Brodowski, J.; Grochans, E. The Effect of Vitamin D Levels on Lipid, Glucose Profiles and Depression in Perimenopausal Women. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022, 26, 3493–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfredi, V.; Dinu, M.; Nucci, D.; Eussen, S.J.P.M.; Amerio, A.; Schram, M.T.; Schaper, N.; Odone, A. Association between Dietary Patterns and Depression: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies and Intervention Trials. Nutr Rev 2023, 81, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleton, K.M.; Boxall, L.R.; Adenuga-Ajayi, O.; Seyar, D.F. Does Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Impact Mental Health? Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Published Controlled Intervention Studies. British Journal of Nutrition 2024, 131, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, H.; Lotfaliany, M.; So, D.; Berding, K.; Berk, M.; Rocks, T.; Hockey, M.; Jacka, F.N.; Marx, W.; Cryan, J.F.; et al. Fiber Intake and Fiber Intervention in Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr Rev 2024, 82, 1678–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).