1. Introduction

Myocardial stimulation occurs due to a sudden voltage change in myocardial tissue. During bipolar pacing, this stimulation arises from the arrival of negatively charged electrons at the cathodal pole of the lead, which then return to the device via the anodal pole. The initiation of this voltage change is termed the “make” phase, and its termination the “break” phase. [

1]

In bipolar pacing configurations, the cathodal pole is typically programmed to the lead tip, while the anodal pole may be programmed to the lead ring, defibrillation coil (bipolar pacing), or the generator itself (unipolar pacing). [

1]

Functionally, myocardial capture can occur at both poles. However lower energy is usually required at the cathodal pole to capture tissue (except during the relative refractory period), whereas higher energy is needed at the anodal pole, particularly when the anode has a large surface area, resulting in lower charge density. Anodal stimulation often occurs during the “break” phase of the stimulus. [

2,

3,

4]

Modern devices, especially cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) systems, allow for multiple pacing vectors between right ventricular (RV) and left ventricular (LV) leads. For example, the cathode may be programmed to the LV lead tip and the anode to the RV lead ring to optimize thresholds. [

1]

When pacing the left ventricle in a bipolar configuration (LV tip [cathode] → RV ring [anode]), high pacing outputs (e.g., for patients with elevated LV thresholds) may inadvertently cause anodal capture at the RV site. This can result in RV-only pacing (due to failed LV capture), leading to loss of CRT benefits and associated clinical risks. [

5] To mitigate this, reprogramming the anode to a larger surface area (e.g., defibrillation coil) reduces charge density and suppresses anodal capture. [

4] For this reason, anodal capture is rarely observed with RV leads with an integrated bipolar design. [

6]

Left bundle branch area pacing (LBBAP) has emerged as a novel technique in conduction system pacing (CSP), addressing limitations of His Bundle Pacing (e.g., unstable electrical parameters and procedural complexity). [

7,

8] It produces a physiological LV activation pattern comparable to CRT, making it a viable option as a bailout strategy during failed CRT implantations or for patients who do not meet CRT criteria but may benefit from physiological pacing. [

9]

Several electrocardiographic criteria are used to confirm successful LBBAP:

- 1.

QRS transition:

- -

During threshold testing: from non-selective left bundle branch pacing (ns-LBBP) to selective left bundle branch pacing (s-LBBP) or to left ventricular septal pacing (LVSP).

- -

At programmed stimulation: transition to s-LBBP with pacing output adjustments.

- 2.

V6 R-wave peak time (V6RWPT):

- -

< 75 ms in patients with narrow native QRS or isolated right bundle branch block (RBBB)

- -

< 80 ms in patients with left bundle branch block (LBBB), interventricular conduction delay (IVCD), RBBB with fascicular block, wide escape rhythm, or asystole.

- 3.

V6-V1 interpeak interval: > 44 ms

- 4.

Stimulus-to-Potential alignment: potential-V6RWPT matches stimulus-V6RWPT (difference about ± 10 ms). [

10]

Among these, QRS transition (though rarely observed) has the highest specificity for confirming true left bundle branch (LBB) capture. [

10]

Transition from ns-LBBP to s-LBBP is defined by prolongation of the stimulus-to-QRS interval (measured from the pacing artifact). On the ECG, this manifests as:

- -

A rounded R’ wave in lead V1, accompanied by prolongation of the V1 R-wave peak time (V1RWPT) exceeding 10 ms.

- -

The development of a deeper S wave in leads V6 and I, while the V6RWPT remains unchanged.

Transition to LVSP, instead, reflects loss of LBB capture, resulting in pure LVSP. Key ECG features include:

- -

Prolongation of the V6RWPT, indicating delayed activation of the left ventricular lateral wall.

- -

Reduced R’ wave amplitude in V1, reflecting diminished direct LBB activation.

- -

Disappearance of S wave in lead I and V6, consistent with altered ventricular depolarization patterns. [

10]

2. Case Presentation

A 75-year-old man with a history of acute myocardial infarction treated with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG; left internal mammal artery to left anterior descending artery) and concomitant modified endo-ventricular circular plasty (Dor procedure) for apical aneurysm and atrial flutter treated with transcatheter ablation in 2022, targeting a critical isthmus at the cresta terminalis, subsequently developed sinus node dysfunction requiring permanent pacemaker implantation. Optimal medical therapy for heart failure was initiated and titrated over several months.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed left ventricular hypertrophy, septal dyskinesia, and apical akinesia, resulting in severe left ventricular dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction, LVEF 25%). Given persistent LV dysfunction despite optimal medical therapy and the presence of LBBB with a QRS duration of 164 ms, an upgrade to CRT was indicated.

Pre-procedural contrast venography demonstrated occlusion of the left axillary vein; thus, the patent left subclavian vein was selected for venous access. A single-coil defibrillation lead was first positioned at the mid-apical septum of the right ventricle. Subsequent attempts to cannulate the coronary sinus for LV lead placement were unsuccessful, despite venographic guidance. As a bailout strategy, a lumenless lead (SelectSecure MRI SureScan 3830, Medtronic) was implanted via a C315-His delivery sheath (Medtronic) for LBBAP. The implanted device (Amplia MRI CRT-D SureScan, Medtronic) was connected to the defibrillation lead (DF4 port) and to the LBBAP lead and the preexisting atrial lead (IS1 port).

Initial LBBAP threshold was 2.0V@0.4ms, with QRS transition from non-selective to selective LBB capture at 2.2V@0.4ms. After current of injury (COI) reduction, threshold improved to 1.0V@0.4ms, with QRS transition at 1.1@0.4ms.

The following day, threshold testing was repeated with multiple vectors to optimize pacing parameters.

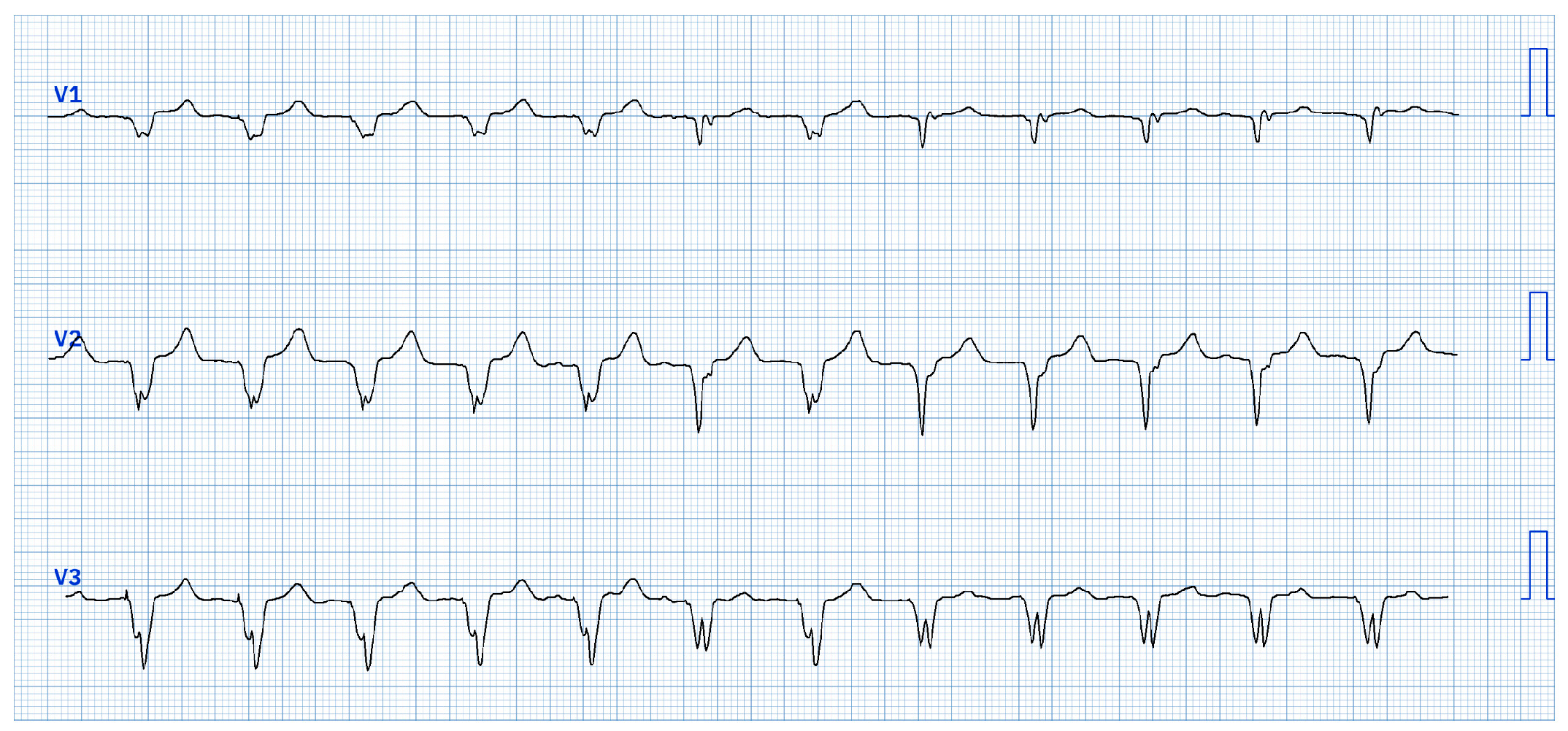

During bipolar pacing (LBBAP tip → RV defibrillation lead ring) starting from 5V@0.4ms, two distinct QRS morphology changes were observed:

- 1.

At 4.5V@0.4ms: morphology consistent with right ventricular apical pacing, attributed to anodal capture at the RV defibrillation lead ring changes to a ns-LBBAP morphology (

Figure 1).

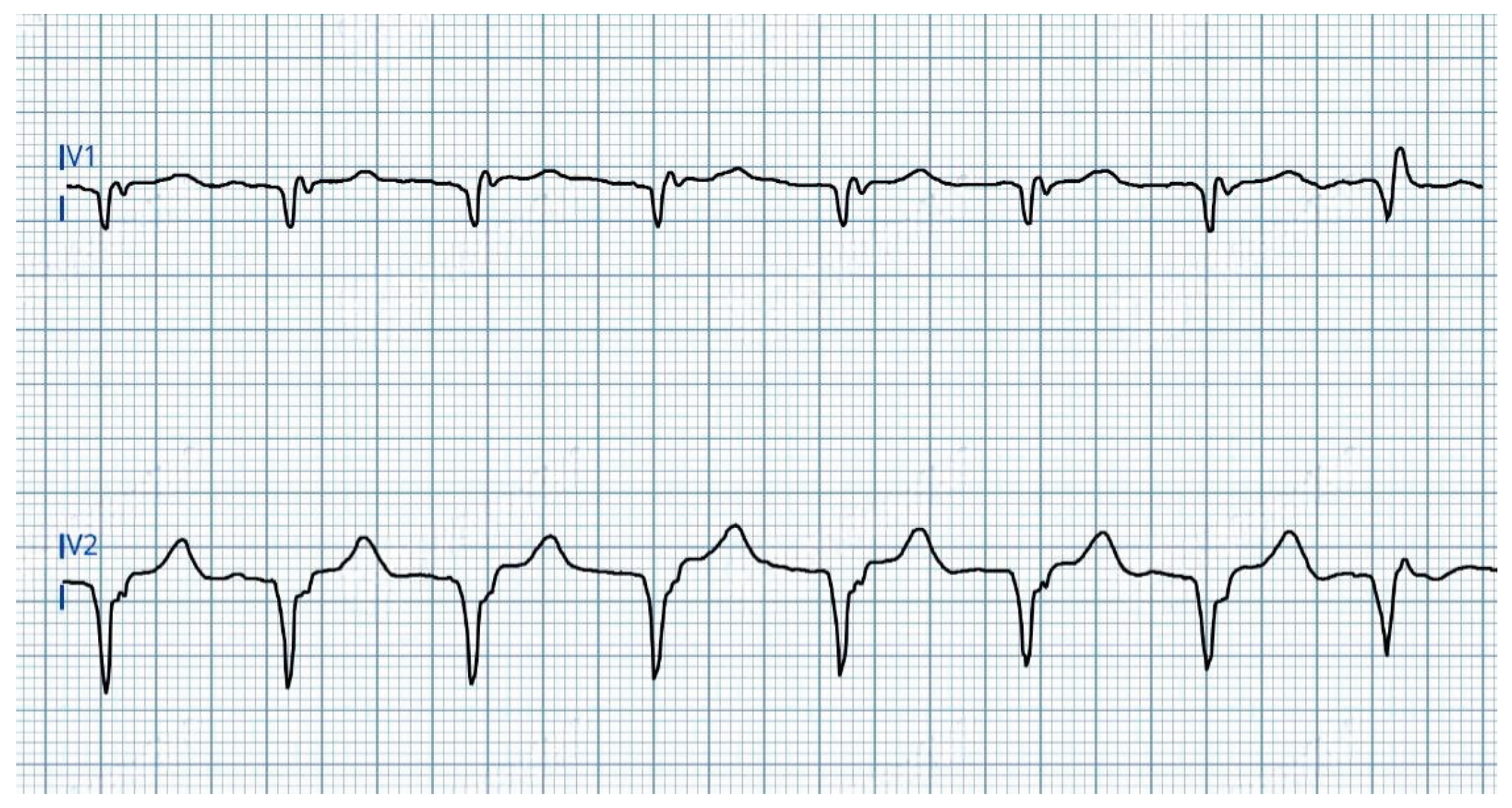

- 2.

At 1.0V@0.4ms: transition from ns-LBBAP to s-LBBAP, with threshold at 0.75V@0.4ms (

Figure 2).

In summary, three distinct QRS morphologies were observed:

> 4.5V@0.4ms: dominance of anodal capture (RV apical pacing) due to high charge density at the anode.

4.5V-1.25V@0.4ms: ns-LBBAP due to progressive reduction of anodal interference.

≤ 1.0V@0.4ms: s-LBBAP, with singularly capture of the LBB.

Voltage reduction revealed a critical gradient: anodal capture dominates at high outputs, while physiological LBB capture emerges at lower voltages, underscoring the importance of optimizing stimulation parameters to maximize LBBAP benefits.

3. Discussion

Although the use of CRT devices has declined with the spread of LBBAP, certain challenges, well-known in CRT implantation, must also be considered for CSP.

A straightforward scenario of anodal capture at the LBBAP lead ring has recently been described. In such cases, the physiological benefits of LBBAP could be lost due to anodal capture at the lead ring, however the hemodynamic effects remain controversial. [

11,

12]

In the case presented here, however, the mechanism of anodal capture resembles that observed in CRT implants, where cathodal and anodal sites are located on two separate leads. This scenario must be carefully considered to prevent the loss of the benefits from both CRT and LBBAP.

To avoid anodal capture in this context it is needed to:

- -

Confirm that anodal capture occurs only at voltages below the programmed pacing output, ensuring an appropriate safety margin.

- -

Select a different anodal pole for bipolar pacing. In devices with a defibrillation lead, choosing a larger-area anode (e.g., the defibrillation coil) can reduce charge density.

4. Conclusions

Anodal capture, a well-known issue in CRT implants, must also be considered in the context of LBBAP, particularly in complex devices with both an RV defibrillation lead and a LBBAP lead. This is especially critical in multi-vector pacing configurations to optimize the benefits of physiological stimulation and avoid the detrimental effects of unintended RV apical pacing.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, A.M. and M.B.; writing-original draft preparation, A.M. and L.R.V.; writing-review and editing, L.C. and J.B.; supervision F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

this research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

data are available on request due to restrictions.

Acknowledgments

the authors have no acknowledgments to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRT |

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy |

| LBBAP |

Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing |

| ICD |

Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator |

| CRT-D |

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy with Defibrillator |

| RV |

Right ventricular |

| LV |

Left ventricular |

| CSP |

Conduction System Pacing |

| ns-LBBP |

non-slective Left Bundle Branch Pacing |

| s-LBBP |

selective Left Bundle Branch Pacing |

| LVSP |

Left ventricular septal pacing |

| V6RWPT |

V6 R-wave peak time |

| RBBB |

Right bundle branch block |

| LBBB |

Left bundle branch block |

| IVCD |

Interventricular conduction delay |

| LBB |

Left bundle branch |

| V1RWPT |

V1 R-wave peak time |

| CABG |

Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| LVEF |

Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| COI |

Current of injury |

References

- Kaszala K, & Ellenbogen KA. Cardiac Pacing and ICDs (7th ed). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. 2020.

- Dekker E. Direct current make and break thresholds for pacemaker electrodes on the canine ventricle. Circ Res. 1970 Nov;27(5):811-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranefield PF, Hoffman BF, Siebens AA. Anodal excitation of cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol. 1957 Aug;190(2):383-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamborero D, Mont L, Alanis R, Berruezo A, Tolosana JM, Sitges M, Vidal B, Brugada J. Anodal capture in cardiac resynchronization therapy implications for device programming. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006 Sep;29(9):940-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dendy KF, Powell BD, Cha YM, Espinosa RE, Friedman PA, Rea RF, Hayes DL, Redfield MM, Asirvatham SJ. Anodal stimulation: an underrecognized cause of nonresponders to cardiac resynchronization therapy. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2011 May 1;11(3):64-72. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thibault B, Roy D, Guerra PG, Macle L, Dubuc M, Gagné P, Greiss I, Novak P, Furlani A, Talajic M. Anodal right ventricular capture during left ventricular stimulation in CRT-implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005 Jul;28(7):613-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang S, Zhou X, Gold MR. Left Bundle Branch Pacing: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Dec 17;74(24):3039-3049. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan ESJ, Soh R, Boey E, Lee JY, de Leon J, Chan SP, Gan HH, Seow SC, Kojodjojo P. Comparison of Pacing Performance and Clinical Outcomes Between Left Bundle Branch and His Bundle Pacing. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2023 Aug;9(8 Pt 1):1393-1403. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayaraman P, Sharma PS, Cano Ó, Ponnusamy SS, Herweg B, Zanon F, Jastrzebski M, Zou J, Chelu MG, Vernooy K, Whinnett ZI, Nair GM, Molina-Lerma M, Curila K, Zalavadia D, Haseeb A, Dye C, Vipparthy SC, Brunetti R, Moskal P, Ross A, van Stipdonk A, George J, Qadeer YK, Mumtaz M, Kolominsky J, Zahra SA, Golian M, Marcantoni L, Subzposh FA, Ellenbogen KA. Comparison of Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing and Biventricular Pacing in Candidates for Resynchronization Therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023 Jul 18;82(3):228-241. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haran Burri, Marek Jastrzebski, Óscar Cano, Karol Čurila, Jan de Pooter, Weijian Huang, Carsten Israel, Jacqueline Joza, Jorge Romero, Kevin Vernooy, Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, Zachary Whinnett, Francesco Zanon, EHRA clinical consensus statement on conduction system pacing implantation: endorsed by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), and Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), EP Europace, Volume 25, Issue 4, April 2023, Pages 1208–1236. [CrossRef]

- Whinnett, Z. I. Whinnett, Z. I., Waxman, R., Cornelussen, R. N., Foley, P., Chandrasekaran, B., Vijayaraman, P., Upadhyay, G. A., Schaller, R. D., Gardas, R., Richardson, T. D., Kudlik, Da., Zimmerman, P., Burrell, J., Lyne, J. C., Stadler, R. W., Herweg, B., & Jastrzebski, M. (2024). PO-02-062 ANODAL CAPTURE DECREASES LEFT VENTRICULAR CONTRACTILITY DURING LEFT BUNDLE BRANCH AREA PACING. Heart Rhythm, 21(5), S284–S285. [CrossRef]

- Ali N, Saqi K, Arnold AD, Miyazawa AA, Keene D, Chow JJ, Little I, Peters NS, Kanagaratnam P, Qureshi N, Ng FS, Linton NWF, Lefroy DC, Francis DP, Boon Lim P, Tanner MA, Muthumala A, Agarwal G, Shun-Shin MJ, Cole GD, Whinnett ZI. Left bundle branch pacing with and without anodal capture: impact on ventricular activation pattern and acute haemodynamics. Europace. 2023 Oct 5;25(10):euad264. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).