Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

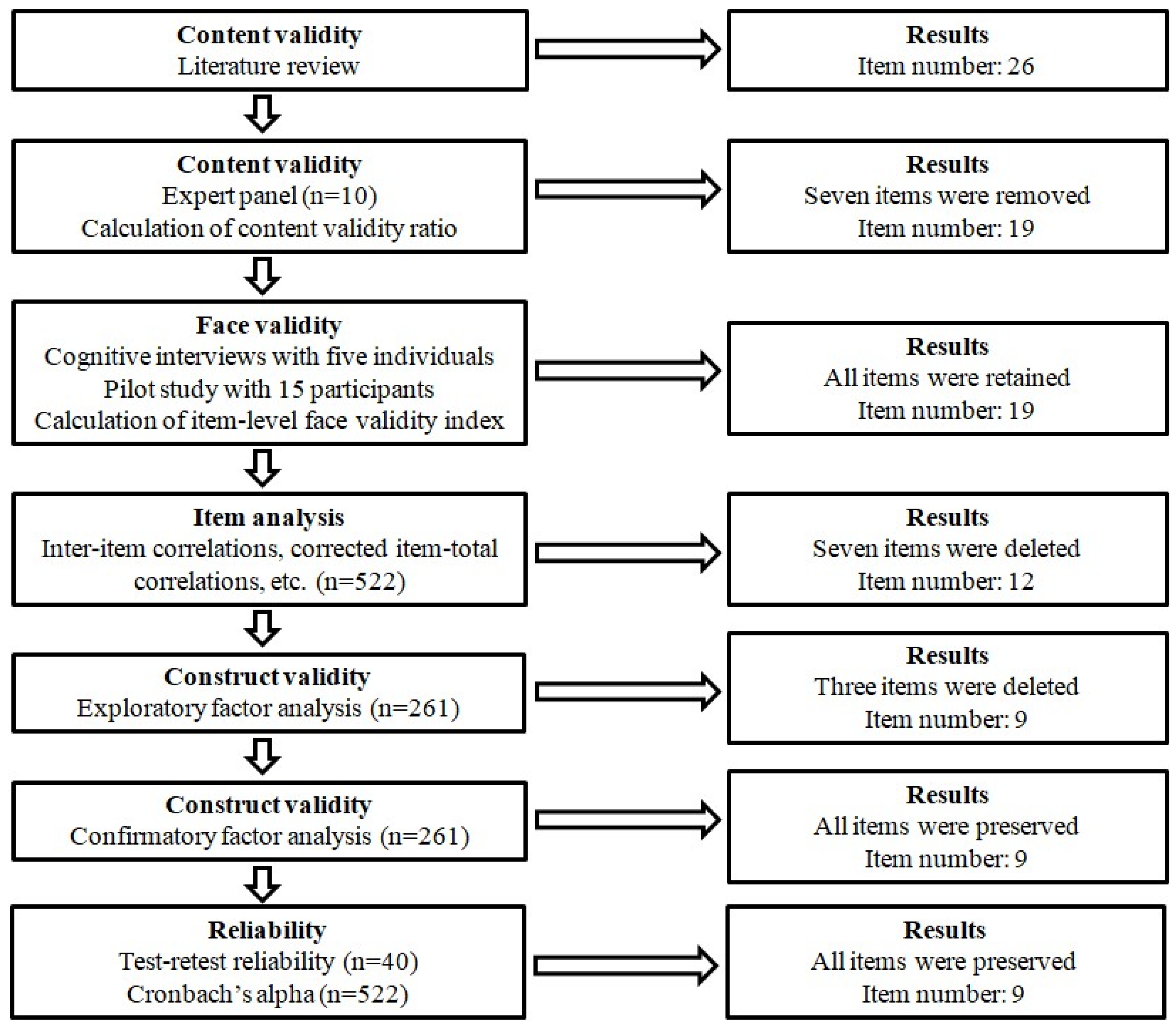

2.1. Development of the Scale

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Item Analysis

2.4. Construct Validity

2.5. Concurrent Validity

2.6. Reliability

2.7. Ethical Considerations

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Item Analysis

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

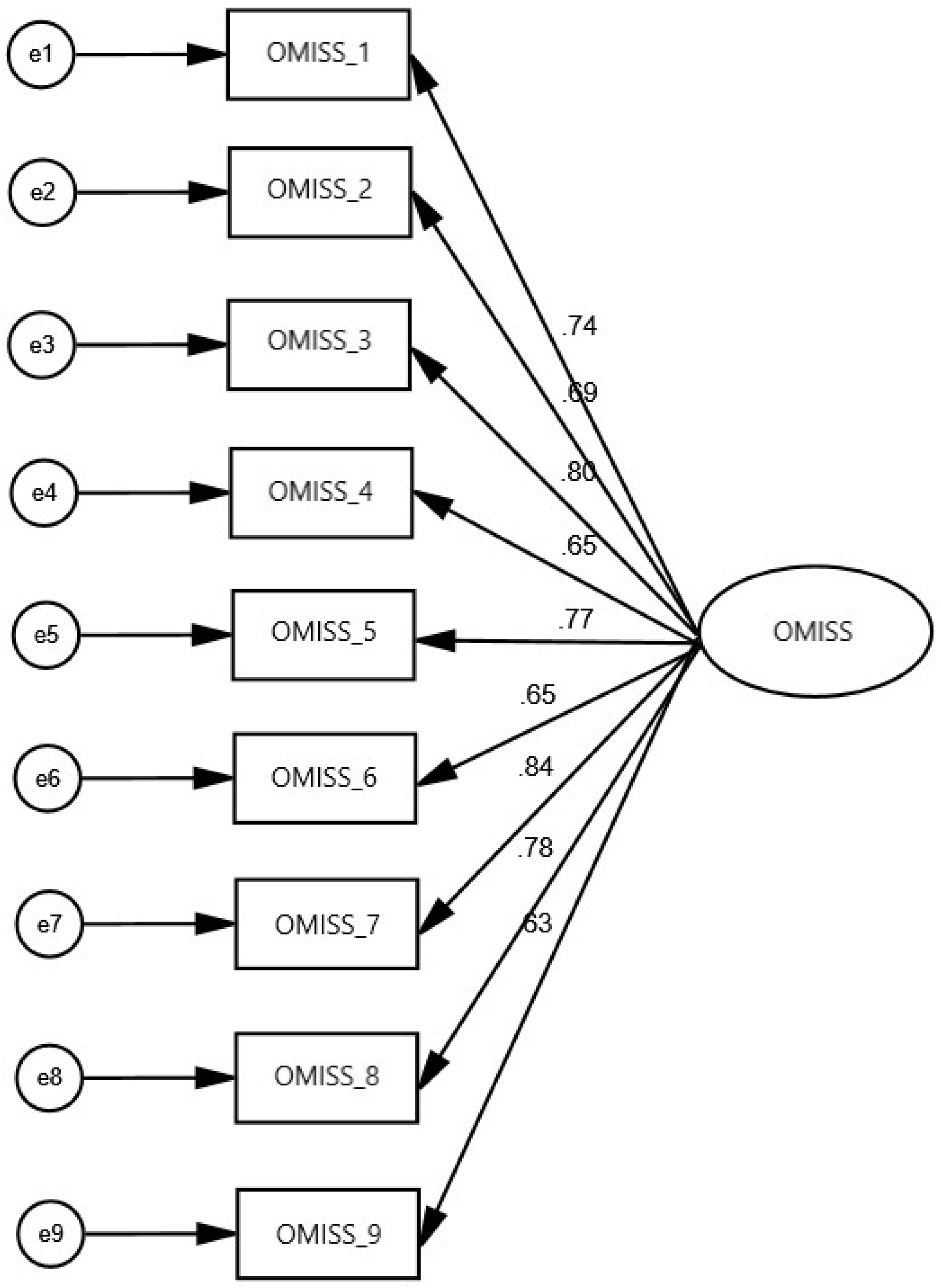

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.4. Concurrent Validity

3.5. Reliability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CMQ | Conspiracy mentality questionnaire |

| CVR | Content validity ratio |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SPSS | Statistical package for social sciences |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| US | United States |

References

- Statista. Number of Internet and Social Media Users Worldwide as of February 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/.

- Statista. Number of Internet Users Worldwide from 2014 to 2029. Available online: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1146844/internet-users-in-the-world.

- Meng, F.; Xie, J.; Sun, J.; Xu, C.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, X.; Jia, T.; Huang, S.; Deng, Y.; Hu, Y. Spreading Dynamics of Information on Online Social Networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2025, 122, e2410227122. [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, G.; Anderson, I.A.; Wood, W. Sharing of Misinformation Is Habitual, Not Just Lazy or Biased. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120, e2216614120. [CrossRef]

- Brady, W.J.; McLoughlin, K.; Doan, T.N.; Crockett, M.J. How Social Learning Amplifies Moral Outrage Expression in Online Social Networks. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe5641. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I.A.; Wood, W. Social Motivations’ Limited Influence on Habitual Behavior: Tests from Social Media Engagement. Motivation Science 2023, 9, 107–119. [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.D.; Sundar, S.S.; Le, T.; Lee, D. “Fake News” Is Not Simply False Information: A Concept Explication and Taxonomy of Online Content. American Behavioral Scientist 2021, 65, 180–212. [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Epstein, Z.; Mosleh, M.; Arechar, A.A.; Eckles, D.; Rand, D.G. Shifting Attention to Accuracy Can Reduce Misinformation Online. Nature 2021, 592, 590–595. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Linden, S.; Albarracín, D.; Fazio, L.; Freelon, D.; Roozenbeek, J.; Swire-Thompson, B.; Van Bavel, J. Using Psychological Ccience to Understand and Fight Health Misinformation; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, 2023;

- Fetzer, J.H. Information: Does It Have To Be True? Minds and Machines 2004, 14, 223–229. [CrossRef]

- Diaz Ruiz, C. Disinformation on Digital Media Platforms: A Market-Shaping Approach. New Media & Society 2025, 27, 2188–2211. [CrossRef]

- Fallis, D. What Is Disinformation? lib 2015, 63, 401–426. [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.G.; Rand, D.G. Fighting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media: Experimental Evidence for a Scalable Accuracy-Nudge Intervention. Psychol Sci 2020, 31, 770–780. [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Research Note: Examining False Beliefs about Voter Fraud in the Wake of the 2020 Presidential Election. HKS Misinfo Review 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Cannon, T.D.; Rand, D.G. Prior Exposure Increases Perceived Accuracy of Fake News. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 2018, 147, 1865–1880. [CrossRef]

- Bodner, G.E.; Musch, E.; Azad, T. Reevaluating the Potency of the Memory Conformity Effect. Memory & Cognition 2009, 37, 1069–1076. [CrossRef]

- Global Health Security: Recognizing Vulnerabilities, Creating Opportunities; Masys, A.J., Izurieta, R., Reina Ortiz, M., Eds.; Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-23490-4.

- Wandless, D. The Effect of Web-Based Clinical Misinformation on Patient Interactions. Medicine 2025, 53, 407–410. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Linden, S. Misinformation: Susceptibility, Spread, and Interventions to Immunize the Public. Nat Med 2022, 28, 460–467. [CrossRef]

- Borges Do Nascimento, I.J.; Beatriz Pizarro, A.; Almeida, J.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; André Gonçalves, M.; Björklund, M.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. Infodemics and Health Misinformation: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Bull World Health Organ 2022, 100, 544–561. [CrossRef]

- Roozenbeek, J.; Schneider, C.R.; Dryhurst, S.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; Van Der Bles, A.M.; Van Der Linden, S. Susceptibility to Misinformation about COVID-19 around the World. R. Soc. open sci. 2020, 7, 201199. [CrossRef]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiracy Theories as Barriers to Controlling the Spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Social Science & Medicine 2020, 263, 113356. [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, R.; Lamberty, P. A Bioweapon or a Hoax? The Link Between Distinct Conspiracy Beliefs About the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak and Pandemic Behavior. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 2020, 11, 1110–1118. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Petit, A.; Causier, C.; East, A.; Jenner, L.; Teale, A.-L.; Carr, L.; Mulhall, S.; et al. Coronavirus Conspiracy Beliefs, Mistrust, and Compliance with Government Guidelines in England. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 251–263. [CrossRef]

- Loomba, S.; De Figueiredo, A.; Piatek, S.J.; De Graaf, K.; Larson, H.J. Measuring the Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation on Vaccination Intent in the UK and USA. Nat Hum Behav 2021, 5, 337–348. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.F.; Velásquez, N.; Restrepo, N.J.; Leahy, R.; Gabriel, N.; El Oud, S.; Zheng, M.; Manrique, P.; Wuchty, S.; Lupu, Y. The Online Competition between Pro- and Anti-Vaccination Views. Nature 2020, 582, 230–233. [CrossRef]

- Aghababaeian, H.; Hamdanieh, L.; Ostadtaghizadeh, A. Alcohol Intake in an Attempt to Fight COVID-19: A Medical Myth in Iran. Alcohol 2020, 88, 29–32. [CrossRef]

- Jolley, D.; Paterson, J.L. Pylons Ablaze: Examining the Role of 5G COVID-19 Conspiracy Beliefs and Support for Violence. British J Social Psychol 2020, 59, 628–640. [CrossRef]

- Dubé, E.; Vivion, M.; MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine Hesitancy, Vaccine Refusal and the Anti-Vaccine Movement: Influence, Impact and Implications. Expert Review of Vaccines 2015, 14, 99–117. [CrossRef]

- Albarracin, D.; Romer, D.; Jones, C.; Hall Jamieson, K.; Jamieson, P. Misleading Claims About Tobacco Products in YouTube Videos: Experimental Effects of Misinformation on Unhealthy Attitudes. J Med Internet Res 2018, 20, e229. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A.; Thompson, T.L. Misinformation About Health: A Review of Health Communication and Misinformation Scholarship. American Behavioral Scientist 2021, 65, 316–332. [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Lazy, Not Biased: Susceptibility to Partisan Fake News Is Better Explained by Lack of Reasoning than by Motivated Reasoning. Cognition 2019, 188, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Who Falls for Fake News? The Roles of Bullshit Receptivity, Overclaiming, Familiarity, and Analytic Thinking. Journal of Personality 2020, 88, 185–200. [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, M.V.; Pennycook, G.; Bear, A.; Rand, D.G.; Cannon, T.D. Belief in Fake News Is Associated with Delusionality, Dogmatism, Religious Fundamentalism, and Reduced Analytic Thinking. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 2019, 8, 108–117. [CrossRef]

- Arin, K.P.; Mazrekaj, D.; Thum, M. Ability of Detecting and Willingness to Share Fake News. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 7298. [CrossRef]

- Maertens, R.; Götz, F.M.; Golino, H.F.; Roozenbeek, J.; Schneider, C.R.; Kyrychenko, Y.; Kerr, J.R.; Stieger, S.; McClanahan, W.P.; Drabot, K.; et al. The Misinformation Susceptibility Test (MIST): A Psychometrically Validated Measure of News Veracity Discernment. Behav Res 2023, 56, 1863–1899. [CrossRef]

- Sparks, J.R.; Katz, I.R.; Beile, P.M. Assessing Digital Information Literacy in Higher Education: A Review of Existing Frameworks and Assessments With Recommendations for Next-Generation Assessment. ETS Research Report Series 2016, 2016, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Maertens, R.; Roozenbeek, J.; Basol, M.; Van Der Linden, S. Long-Term Effectiveness of Inoculation against Misinformation: Three Longitudinal Experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 2021, 27, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Roozenbeek, J.; Van Der Linden, S. Fake News Game Confers Psychological Resistance against Online Misinformation. Palgrave Commun 2019, 5, 65. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.H. Neutralizing Misinformation through Inoculation: Exposing Misleading Argumentation Techniques Reduces Their Influence. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175799. [CrossRef]

- Guess, A.M.; Lerner, M.; Lyons, B.; Montgomery, J.M.; Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J.; Sircar, N. A Digital Media Literacy Intervention Increases Discernment between Mainstream and False News in the United States and India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 15536–15545. [CrossRef]

- Swire, B.; Berinsky, A.J.; Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.H. Processing Political Misinformation: Comprehending the Trump Phenomenon. R. Soc. open sci. 2017, 4, 160802. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Linden, S.; Roozenbeek, J.; Maertens, R.; Basol, M.; Kácha, O.; Rathje, S.; Traberg, C.S. How Can Psychological Science Help Counter the Spread of Fake News? Span. J. Psychol. 2021, 24, e25. [CrossRef]

- Roozenbeek, J.; Maertens, R.; Herzog, S.M.; Geers, M.; Kurvers, R.; Sultan, M.; Van Der Linden, S. Susceptibility to Misinformation Is Consistent across Question Framings and Response Modes and Better Explained by Myside Bias and Partisanship than Analytical Thinking. Judgm Decis Mak 2022, 17, 547–573. [CrossRef]

- Roozenbeek, J.; Maertens, R.; McClanahan, W.; Van Der Linden, S. Disentangling Item and Testing Effects in Inoculation Research on Online Misinformation: Solomon Revisited. Educational and Psychological Measurement 2021, 81, 340–362. [CrossRef]

- Brick, C.; Hood, B.; Ekroll, V.; de-Wit, L. Illusory Essences: A Bias Holding Back Theorizing in Psychological Science. Perspect Psychol Sci 2022, 17, 491–506. [CrossRef]

- Aird, M.J.; Ecker, U.K.H.; Swire, B.; Berinsky, A.J.; Lewandowsky, S. Does Truth Matter to Voters? The Effects of Correcting Political Misinformation in an Australian Sample. R. Soc. open sci. 2018, 5, 180593. [CrossRef]

- Batailler, C.; Brannon, S.M.; Teas, P.E.; Gawronski, B. A Signal Detection Approach to Understanding the Identification of Fake News. Perspect Psychol Sci 2022, 17, 78–98. [CrossRef]

- Dhami, M.K.; Hertwig, R.; Hoffrage, U. The Role of Representative Design in an Ecological Approach to Cognition. Psychological Bulletin 2004, 130, 959–988. [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Fifth edition.; SAGE Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, California, 2022; ISBN 978-1-5443-7934-0.

- Johnson, R.L.; Morgan, G.B. Survey Scales: A Guide to Development, Analysis, and Reporting; The Guilford Press: New York, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4625-2696-3.

- Saris, W.E. Design, Evaluation, and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research; Second Edition.; Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-63461-5.

- Denniss, E.; Lindberg, R. Social Media and the Spread of Misinformation: Infectious and a Threat to Public Health. Health Promotion International 2025, 40, daaf023. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.; Tump, A.N.; Ehmann, N.; Lorenz-Spreen, P.; Hertwig, R.; Gollwitzer, A.; Kurvers, R.H.J.M. Susceptibility to Online Misinformation: A Systematic Meta-Analysis of Demographic and Psychological Factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2024, 121, e2409329121. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; McKee, M.; Torbica, A.; Stuckler, D. Systematic Literature Review on the Spread of Health-Related Misinformation on Social Media. Social Science & Medicine 2019, 240, 112552. [CrossRef]

- Ayre, C.; Scally, A.J. Critical Values for Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio: Revisiting the Original Methods of Calculation. Meas Eval Counsel Dev 2014, 47, 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, K. Cognitive Interviewing Methodologies. Clin Nurs Res 2021, 30, 375–379. [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.S.B. ABC of Response Process Validation and Face Validity Index Calculation. EIMJ 2019, 11, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most from Your Analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval 2005, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- DeVon, H.A.; Block, M.E.; Moyle-Wright, P.; Ernst, D.M.; Hayden, S.J.; Lazzara, D.J.; Savoy, S.M.; Kostas-Polston, E. A Psychometric Toolbox for Testing Validity and Reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007, 39, 155–164. [CrossRef]

- De Vaus, D. Surveys in Social Research; 5th ed.; Routledge: London, 2004;

- Yusoff, M.S.B.; Arifin, W.N.; Hadie, S.N.H. ABC of Questionnaire Development and Validation for Survey Research. EIMJ 2021, 13, 97–108. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin B; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: New Jersey, 2017;

- De Winter, J.C.F.; Dodou, D.; Wieringa, P.A. Exploratory Factor Analysis With Small Sample Sizes. Multivariate Behav Res 2009, 44, 147–181. [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistics Notes: Cronbach’s Alpha. BMJ 1997, 314, 572–572. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.; Homburg, C. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing and Consumer Research: A Review. Int J Res Mark 1996, 13, 139–161. [CrossRef]

- DiSiNFO Database Available online: https://euvsdisinfo.eu/disinformation-cases/.

- Diplomatic Service of the European Union Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/_en.

- Nasa Data Reveals Dramatic Rise in Intensity of Weather Events Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/17/nasa-data-reveals-dramatic-rise-in-intensity-of-weather-events.

- France Mulls Social Media Ban for Under-15s after Fatal School Stabbing Available online: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20250611-france-eyes-social-media-ban-for-under-15s-after-school-stabbing.

- The Guardian Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Guardian.

- France 24 Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/France_24.

- Santirocchi, A.; Spataro, P.; Alessi, F.; Rossi-Arnaud, C.; Cestari, V. Trust in Science and Belief in Misinformation Mediate the Effects of Political Orientation on Vaccine Hesitancy and Intention to Be Vaccinated. Acta Psychologica 2023, 237, 103945. [CrossRef]

- Cologna, V.; Kotcher, J.; Mede, N.G.; Besley, J.; Maibach, E.W.; Oreskes, N. Trust in Climate Science and Climate Scientists: A Narrative Review. PLOS Clim 2024, 3, e0000400. [CrossRef]

- Bogert, J.M.; Buczny, J.; Harvey, J.A.; Ellers, J. The Effect of Trust in Science and Media Use on Public Belief in Anthropogenic Climate Change: A Meta-Analysis. Environmental Communication 2024, 18, 484–509. [CrossRef]

- Guess, A.M.; Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J. Exposure to Untrustworthy Websites in the 2016 US Election. Nat Hum Behav 2020, 4, 472–480. [CrossRef]

- Cologna, V.; Mede, N.G.; Berger, S.; Besley, J.; Brick, C.; Joubert, M.; Maibach, E.W.; Mihelj, S.; Oreskes, N.; Schäfer, M.S.; et al. Trust in Scientists and Their Role in Society across 68 Countries. Nat Hum Behav 2025, 9, 713–730. [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Heferon, M.; Kennedy, B.; Johnson, C. Trust and Mistrust in Americans’ Views of Scientific Experts; Pew Research Center: USA, 2019; pp. 1–96;.

- About Pew Research Center Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/about/.

- Douglas, K.M. Are Conspiracy Theories Harmless? Span. J. Psychol. 2021, 24, e13. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Luo, X.; Jia, H. Is It All a Conspiracy? Conspiracy Theories and People’s Attitude to COVID-19 Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 1051. [CrossRef]

- Biddlestone, M.; Azevedo, F.; Van Der Linden, S. Climate of Conspiracy: A Meta-Analysis of the Consequences of Belief in Conspiracy Theories about Climate Change. Current Opinion in Psychology 2022, 46, 101390. [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P.; Chan, H.-W. Conspiracy Theories and Climate Change: A Systematic Review. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2023, 91, 102129. [CrossRef]

- Jolley, D.; Marques, M.D.; Cookson, D. Shining a Spotlight on the Dangerous Consequences of Conspiracy Theories. Current Opinion in Psychology 2022, 47, 101363. [CrossRef]

- Bruder, M.; Haffke, P.; Neave, N.; Nouripanah, N.; Imhoff, R. Measuring Individual Differences in Generic Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories Across Cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Katsiroumpa, A.; Moisoglou, I.; Lamprakopoulou, K.; Galani, O.; Tsiachri, M.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Galanis, P. Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire: Translation and Validation in Greek. International Journal of Caring Sciences 2025, Under press.

- Lantian, A.; Muller, D.; Nurra, C.; Douglas, K.M. Measuring Belief in Conspiracy Theories: Validation of a French and English Single-Item Scale. rips 2016, 29, 1. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [CrossRef]

- Scherer, L.D.; Pennycook, G. Who Is Susceptible to Online Health Misinformation? Am J Public Health 2020, 110, S276–S277. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Infodemic Management: An Overview of Infodemic Management During COVID-19, January 2020-May 2021; 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003596-6.

- Bruns, H.; Dessart, F.J.; Krawczyk, M.; Lewandowsky, S.; Pantazi, M.; Pennycook, G.; Schmid, P.; Smillie, L. Investigating the Role of Source and Source Trust in Prebunks and Debunks of Misinformation in Online Experiments across Four EU Countries. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 20723. [CrossRef]

- Frederick, S. Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2005, 19, 25–42. [CrossRef]

- Feist, G.J. Predicting Interest in and Attitudes toward Science from Personality and Need for Cognition. Personality and Individual Differences 2012, 52, 771–775. [CrossRef]

- Arceneaux, K.; Vander Wielen, R.J. The Effects of Need for Cognition and Need for Affect on Partisan Evaluations. Political Psychology 2013, 34, 23–42. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Parker, S.K.; De Jong, J.P.J. Need for Cognition as an Antecedent of Individual Innovation Behavior. Journal of Management 2014, 40, 1511–1534. [CrossRef]

| Please think about what you do when you see a post or story that interests you on social media or websites. How often do you … |

Mean (standard deviation) | Corrected item-total correlation | Floor effect (%) | Ceiling effect (%) | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted | Item exclusion or retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2.64 (0.94) | 0.430 | 12.6 | 1.0 | -0.06 | -0.62 | 0.885 | Retained |

|

1.25 (0.67) | 0.245 | 85.1 | 0.6 | 3.01 | 9.36 | 0.889 | Excluded |

|

1.21 (0.58) | 0.226 | 85.4 | 0.2 | 3.17 | 10.82 | 0.890 | Excluded |

|

3.19 (1.34) | 0.665 | 14.9 | 19.7 | -0.23 | -1.12 | 0.877 | Retained |

|

2.69 (1.24) | 0.664 | 21.5 | 8.2 | 0.19 | -0.98 | 0.877 | Retained |

|

1.22 (0.64) | 0.260 | 86.4 | 0.6 | 3.33 | 11.76 | 0.889 | Excluded |

|

2.90 (1.25) | 0.769 | 15.9 | 12.3 | 0.07 | -0.99 | 0.873 | Retained |

|

2.69 (1.30) | 0.640 | 25.3 | 9.8 | 0.17 | -1.09 | 0.878 | Retained |

|

2.93 (1.25) | 0.728 | 15.7 | 11.7 | 0.01 | -1.03 | 0.875 | Retained |

|

3.55 (1.14) | 0.600 | 5.2 | 23.0 | -0.48 | -0.61 | 0.880 | Retained |

|

1.19 (0.56) | 0.234 | 87.7 | 0.2 | 3.43 | 12.52 | 0.889 | Excluded |

|

1.14 (0.45) | 0.234 | 89.5 | 0.0 | 3.50 | 12.75 | 0.889 | Excluded |

|

2.64 (1.15) | 0.433 | 19.2 | 5.6 | 0.19 | -0.79 | 0.886 | Retained |

|

2.62 (1.19) | 0.790 | 20.9 | 6.7 | 0.27 | -0.85 | 0.872 | Retained |

|

2.87 (1.17) | 0.705 | 12.6 | 9.8 | 0.15 | -0.81 | 0.876 | Retained |

|

3.51 (1.23) | 0.590 | 7.1 | 25.9 | -0.43 | -0.83 | 0.880 | Retained |

|

3.41 (1.15) | 0.504 | 5.0 | 20.5 | -0.23 | -0.83 | 0.883 | Retained |

|

1.23 (0.61) | 0.277 | 86.0 | 1.1 | 2.75 | 6.79 | 0.889 | Excluded |

|

1.16 (0.50) | 0.236 | 89.5 | 0.4 | 3.27 | 10.15 | 0.889 | Excluded |

| Please think about what you do when you see a post or story that interests you on social media or websites. How often do you ... |

One factor | |

|---|---|---|

| Factor loadings | Communalities | |

|

0.513 | 0.264 |

|

0.770 | 0.593 |

|

0.721 | 0.520 |

|

0.801 | 0.642 |

|

0.682 | 0.466 |

|

0.781 | 0.611 |

|

0.692 | 0.479 |

|

0.545 | 0.297 |

|

0.849 | 0.721 |

|

0.799 | 0.638 |

|

0.693 | 0.480 |

|

0.588 | 0.345 |

| Please think about what you do when you see a post or story that interests you on social media or websites. How often do you ... |

One factor | |

|---|---|---|

| Factor loadings | Communalities | |

|

0.771 | 0.595 |

|

0.778 | 0.606 |

|

0.887 | 0.770 |

|

0.761 | 0.580 |

|

0.841 | 0.707 |

|

0.748 | 0.559 |

|

0.884 | 0.781 |

|

0.824 | 0.679 |

|

0.724 | 0.524 |

| Scale | Online Misinformation Susceptibility Scale | |

|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s correlation coefficient | P-value | |

| Fake news detection scale | -0.135 | 0.002 |

| Trust in Scientists Scale | -0.304 | <0.001 |

| Single-item trust in scientists scale | -0.280 | <0.001 |

| Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire | 0.159 | <0.001 |

| Single-item conspiracy belief scale | 0.095 | 0.030 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).