1. Introduction

Blind Image Quality Assessment (BIQA) plays a critical role in a wide range of applications, including device benchmarking and image-driven pattern analysis. Its influence spans multiple domains such as image quality assurance, data compression, signal transmission, media quality of service, user experience evaluation, image enhancement, object recognition, and high-level content understanding [

1,

2,

3]. Unlike full- or reduced-reference methods [

4,

5,

6,

7], BIQA aims to estimate perceptual image quality solely based on the distorted image itself, without access to any corresponding reference image or related metadata. This no-reference characteristic makes BIQA especially well-suited for large-scale, real-world deployments in industrial and consumer-level scenarios where reference images are typically unavailable. BIQA is not only foundational for improving automated visual systems but also essential for ensuring quality consistency in the era of ubiquitous imaging.

With the rapid advancement of imaging hardware and the widespread deployment of high-performance chips, ultra-high-definition (UHD) images have become increasingly accessible in everyday life, not only through professional imaging equipment but also via consumer-grade mobile devices. This surge in image resolution presents significant challenges for the BIQA task in the UHD domain. The resolution of realistic images in public BIQA datasets has increased dramatically, from ≈ 500 × 500 pixels in early datasets such as LIVE Challenge (CLIVE) [

8] to 3,840 × 2,160 pixels in recent benchmarks [

9]. Despite this progress in data availability, effectively handling UHD images in BIQA remains an open and unresolved problem, due to the high computational cost, increased visual complexity, and scale sensitivity of existing models.

To address these challenges of BIQA in the UHD domain, several kinds of existing approaches offer valuable insights into modeling perceptual quality under high-resolution conditions. These methods could be broadly categorized based on their methodological foundations, architectural designs, and feature extraction strategies.

Handcrafted feature-based methods. An input image can be quantified by a compact feature vector, which serves as the input to a regression model for quality score prediction. For example, Chen

. extract handcrafted features by computing maximum gradient variations and local entropy across multiple image channels, which are then combined to assess image sharpness [

10]. Yu

. treat the outputs of multiple indicators as mid-level features and explore various regression models for predicting perceptual quality [

11]. Wu

. extract multi-stage semantic features from a pre-trained deep network and refine them using a multi-level channel attention module to improve prediction accuracy [

12]. Similarly, Chen and Yu utilize a pre-trained deep network as a fixed feature extractor and evaluate a range of regression models on the BIQA task [

13]. These feature-based approaches [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] are computationally efficient and can compress an UHD image into a low-dimensional representation, enabling fast quality prediction. However, their reliance on handcrafted or shallow features often limits their representational capacity, making it challenging to capture the rich visual structures and complex distortions present in UHD images.

Patch-based deep learning methods. Many deep learning-based approaches adopt a patch-based strategy, where numerous sub-regions (patches) are sampled from an input image and fed into a neural network. The image quality score is then predicted through an end-to-end learning process that jointly optimizes hierarchical feature representations and network parameters. For instance, Yu

. develop a shallow convolutional neural network (CNN), where randomly cropped patches from each image are used to train the network by minimizing a cost function with respect to the corresponding global image quality score [

15,

16]. Bianco

. explore the use of features extracted from pre-trained networks, as well as fine-tuning strategies tailored for the BIQA task, and the final image quality score is obtained by average-pooling the predicted scores across multiple patches [

17]. Ma

. propose a multi-task, end-to-end framework that simultaneously predicts distortion types and image quality using two sub-networks [

18]. Su

. introduce a hyper-network architecture that divides the BIQA process into three stages, content understanding, perception rule learning, and self-adaptive score regression [

19]. While these patch-based methods [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] offer an effective means to learn visual features in a data-efficient manner, they typically assign the same global quality score to all patches regardless of local variation. This simplification overlooks the spatial heterogeneity and region-specific distortions that are especially pronounced in UHD images.

Transformer-based methods. To fully exploit image content and mitigate the negative effects of cropping or resizing, BIQA based on Transformer and their variants has been proposed [

20,

21,

22]. These models leverage the strength of self-attention mechanisms to capture both global and local dependencies, which is especially important for handling the complex structures in high-resolution images. For instance, Ke

. introduce a multi-scale image quality Transformer, which takes full-resolution images as input. The model represents image quality at multiple granularities with varying sizes and aspect ratios, and incorporates a hash-based spatial and scale-aware embedding to support positional encoding in the multi-scale representation [

23]. Qin

. fine-tune a pre-trained vision backbone and introduce a Transformer decoder to extract quality-aware features. They further propose an attention panel that enhances performance and reduces prediction uncertainty [

24]. Yang

. design a model that uses image patches for feature extraction, applies channel-wise self-attention, and incorporates a scale factor to model the interaction between global context and local details. The final quality score is computed as a weighted aggregation of patch-level scores [

25]. Pan

. design a semantic attention module for refining quality perceptual features and introduce a perceptual rule learning module tailed to image content, leveraging image semantics into the BIQA process [

26]. Despite their superior performance, these Transformer-based models [

23,

24,

25,

26] often require substantial computational resources for training and fine-tuning. This high computational cost poses a barrier to their widespread application, particularly in real-time or resource-constrained environments.

Large multi-modal model-based methods. Large multi-modal models (LMMMs) offer promising opportunities for advancing BIQA by integrating both visual and textual information for rich image quality representation. By leveraging language understanding alongside visual perception, these models can incorporate subjective reasoning, descriptive feedback, and contextual knowledge into the assessment process. For example, You

. construct a multi-functional BIQA framework that includes both subjective scoring and comparison tasks. They develop a LMMM capable of interpreting user-provided explanations and reasoning to inform the final quality predictions [

27]. Zhu

. train a LMMM across diverse datasets to enable it to compare the perceptual quality of multiple anchor images. The final quality scores are derived via maximum a posteriori estimation from a predicted comparison probability matrix [

28]. Chen

. further extend the capabilities of LMMMs by incorporating detailed visual quality analysis from multiple modalities, including the image itself, quality-related textual descriptions, and distortion segmentation. They utilize multi-scale feature learning to support image quality answering and region-specific distortion detection via text prompts [

29]. Kwon

. generate a large number of attribute-aware pseudo-labels by using LMMM and allow to learn rich representative attributes of image quality by fine-tuning on large image datasets, and these quality-related knowledge enables several applications in real-world scenarios [

30]. While these LMMM-based frameworks significantly enhance the flexibility and interpretability of BIQA systems, they come with substantial costs. Training such models requires massive amounts of annotated image-text data and high-performance computational resources [

27,

28,

29,

30]. In addition, the inference time of LMMMs is often longer compared to conventional deep learning models, which limits their practical deployment in real-time or resource-constrained scenarios.

To the best of our knowledge, a limited number of studies have attempted to address the challenges of handling UHD images in the BIQA task. These pioneering efforts have explored various strategies to adapt deep learning models for the high computational and perceptual complexity of UHD content. Huang

. propose a patch-based deep network that integrates ResNet [

31], Vision Transformer (ViT) [

21], and recurrent neural network (RNN) [

32] to benchmark their curated high-resolution image database [

33]. This hybrid architecture is designed to combine spatial feature extraction, global context modeling, and sequential processing. Sun

. develop a multi-branch framework that leverages a pre-trained backbone to extract features corresponding to global aesthetic attributes, local technical distortions, and salient content. These diverse feature representations are fused and regressed into final quality scores, enabling the model to account for multiple dimensions of perceptual quality in UHD images [

34]. Tan

. explore Swin Transformer [

22] to process full-resolution images efficiently. Their approach mimics human visual perception by assigning adaptive weights to different sub-regions and incorporates fine-grained frequency-domain information to enhance prediction accuracy [

35]. Collectively, these studies mark significant progress in extending BIQA methods to UHD content. However, the approaches in [

33,

34,

35] rely on complex multi-branch architectures and Transformer-based pyramid perception mechanisms, which demand substantial computational resources and incur high processing times. These limitations hinder their scalability and practicality in real-world UHD applications.

In this study, we propose a novel framework, SUper-resolved Pseudo References In Dual-branch Embedding (SURPRIDE), to address the challenges of BIQA in the UHD domain. The core idea is to leverage super-resolution (SR) as a lightweight and deterministic transformation to generate pseudo-reference from the distorted input. Although SR is not intended to restore ground-truth quality, it introduces structured and distortions that provide informative visual contrasts. Further, by pairing each distorted image with its corresponding SR version, we construct a dual-branch network architecture that simultaneously learns intrinsic quality representations from the original input and comparative quality cues from the pseudo-reference. This design enables the model to better capture fine-grained differences that are especially critical in UHD images.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows,

A novel BIQA framework, namely SUper-resolved Pseudo References In Dual-branch Embedding (SURPRIDE), is proposed, that leverages SR reconstruction as a self-supervised transformation to generate external quality representations.

A dual-branch network with a hybrid loss function is implemented. It jointly models intrinsic quality features from the distorted image and comparative cues from the generated pseudo-reference. The hybrid loss function combines the cosine similarity and mean squared error (MSE), allowing to learn from both absolute quality indicators and relational differences between the input patch pairs.

Comprehensive experiments are conducted on multiple BIQA benchmarks, including UHD, high-definition (HD), and standard-definition (SD) image datasets. The results demonstrate that SURPRIDE achieves superior or competitive performance compared to state-of-the-art (SOTA) works.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 details the proposed SURPRIDE framework, including the motivation behind the dual-branch architecture and descriptions of its core components, patch preparation, the dual-branch network design, and the proposed hybrid loss function.

Section 3 outlines the experimental setup, including the datasets used, baseline BIQA models for comparison, implementation details, and the evaluation protocol.

Section 4 presents a comprehensive analysis of the experimental results across UHD, HD, and SD image databases, along with supporting ablation studies on the UHD-IQA database [

9].

Section 5 discusses the key findings, practical implications, and current limitations of the proposed SURPRIDE framework. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the study and highlights potential directions for future research in BIQA for UHD imagery.

5. Discussion

BIQA in the UHD domain remains challenging. Most existing BIQA approaches rely on handcrafted features [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14], patch-based learning [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

51], self-attention mechanisms [

23,

24,

25,

26,

49], or multi-modal large-model representations [

27,

28,

29,

30]. A limited number of models have been specifically tailored for UHD images [

33,

34,

35], and these typically involve complex architectures and computationally intensive modules such as Transformers [

20,

21,

22,

26]. While effective, such designs are often impractical for real-world deployment due to their high resource requirements and limited scalability. To address these limitations, we propose a lightweight dual-branch framework, SURPRIDE, to represent image quality by learning from both the original input and a super-resolved pseudo-reference. Specifically, ConvNeXt [

54] is employed as the VFM for efficient feature extraction, and SwinFIR [

55] is used for fast SR reconstruction. Inspired by the visual differences observed between high- and low-quality images after down-sampling and SR reconstruction, a hybrid loss function is introduced that balances prediction accuracy with feature similarity. This design enables the network to effectively learn both absolute and comparative quality cues.

The SURPRIDE framework demonstrates top-tier BIQA performance on the UHD-IQA (

Table 2,

Figure 4) and HR-IQA (

Table 10) databases, both of which contain authentic UHD images. The effectiveness of the proposed method can be attributed to several key factors. First, the use of ConvNeXt [

54] as the VFM backbone in both branches allows for the extraction of intrinsic characteristics from the original input and comparative embeddings from the SR-reconstructed patch (

Table 3). While the primary branch plays the dominant role in BIQA performance, the SR branch provides valuable complementary information, leading to further improvements (

Table 8). Motivated by the observed phenomenon that higher-quality images often exhibit more noticeable degradation after SR reconstruction (

Figure 1), the features from both branches are weighted and concatenated to form a more robust representation for quality prediction. Second, critical parameters, including input image size, patch size, SR method, and scaling factor, are systematically optimized through extensive ablation studies (

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8). These settings enable the framework to achieve optimal performance, with additional applications across HD and SD databases. Third, the proposed hybrid loss function encourages the learning of comparative embeddings by leveraging differences introduced through SR reconstruction. This loss formulation enhances the network’s ability to model perceptual quality more accurately (

Table 6 and

Table 9). In summary, SURPRIDE combines a lightweight architecture with strategically tuned components and loss design to deliver superior or competitive results on UHD image databases, while remaining efficient and scalable for real-world deployment.

The proposed SURPRIDE framework demonstrates strong performance not only on UHD image databases (

Table 2,

Table 10), but also on HD (

Table 11,

Table 12) and SD (

Table 13,

Table 14) image databases. Falling under the category of patch-based deep learning methods, SURPRIDE randomly samples patches from the original images and reconstructs corresponding SR patches [

55]. These pairs of patches are used to extract deep representative features, which are weighted and concatenated for robust quality representation and score prediction. Unlike earlier approaches that use small patches of size 16×16 or 32×32 [

15,

16,

60], SURPRIDE adopts a much larger patch size of 384×384 (

Table 4), which better captures contextual and structural information. Prior studies suggest that larger patch sizes contribute positively to performance in BIQA tasks [

17,

34,

46,

50,

51]. Notably, SURPRIDE avoids reliance on high-computation modules or complex attention-based mechanisms. Its use of ConvNeXt [

54] as the feature extraction backbone proves effective across a wide range of image resolutions. The success of SURPRIDE across databases with varying resolutions (

Table 4) could be attributed to several key factors. (a) Large patch sizes (384×384 or 224×224) retain sufficient local information while also capturing broader spatial context. These patches represent meaningful regions of the image, enabling the model to learn fine-grained distortion patterns that are often consistent within high-resolution content [

50,

59]. (b) Training with multiple patches per image increases data diversity and supports better generalization [

48,

51,

59,

60]. By sampling image patches either randomly or strategically, the model is exposed to a diverse range of distortions and scene content, helping to compensate for the unavailability of full-resolution images during training. (c) Patch-level features tend to be scale-invariant, allowing models trained on high-resolution patches to generalize well across different image sizes [

48,

51,

59]. Local distortions in UHD images often exhibit characteristics similar to those in HD or SD images. (d) Moreover, processing entire UHD images directly is computationally prohibitive in terms of memory and training time. Patch-based learning provides a practical alternative, enabling the reuse of deep networks [

20,

21,

22,

30,

31,

46,

51,

54] without compromising batch size or training stability. In conclusion, patch-based learning strategies remain highly effective for BIQA in the UHD domain, offering a favorable balance between computational efficiency and model accuracy.

Dual- and multi-branch network architectures have become increasingly prominent in advancing BIQA tasks [

33,

34,

35,

46,

47]. This trend reflects the growing demand for richer and more nuanced modeling of perceptual image quality that single-branch models often struggle to achieve effectively. First, these architectures enable the separation and specialization of complementary information [

46,

48,

59,

60]. Dual-branch networks typically extract different feature types, such as global semantics (or quality-aware encoding) in one branch and local distortions (or content-aware encoding) in the other. Multi-branch networks may explicitly model multiple perceptual dimensions, including aesthetic quality, data fidelity, object saliency, and content structure. This separation facilitates better feature disentanglement, allowing the network to handle the complex, multidimensional characteristics of human visual perception effectively [

46,

48]. Second, robustness and adaptability across distortion types are enhanced. Real-world images often exhibit mixed or unknown distortion types, and no single representation is sufficient to capture all relevant quality variations [

51,

58]. Branching allows each sub-network to specialize in detecting specific distortions or perceptual cues, leading to improved generalization and performance across diverse scenarios. Third, dual- and multi-branch architectures provide flexibility for adaptive fusion [

46,

47,

48,

59,

60]. By incorporating attention mechanisms, gating functions, or learned weighting schemes, these models can dynamically integrate information from multiple branches. This enables the network to emphasize the most relevant features at inference time, which is particularly important for UHD content or images with complex structures, where different regions may contribute unequally to perceived quality. Ultimately, the popularity of dual- and multi-branch networks is driven by their superior ability to align with human perceptual processes. Their modular and interpretable design supports the modeling of multi-scale, multi-type distortions in a way that more closely reflects how humans assess image quality. As a result, such architectures have consistently demonstrated strong performance on challenging, distortion-rich datasets in both synthetic and authentic environments.

Several limitations exist in the current study. First, the design and exploration of loss functions are not comprehensive. Alternative loss functions, such as marginal cosine similarity loss [

63], may offer additional benefits for enhancing feature similarity learning and improving quality prediction accuracy. Second, the feature fusion strategy employed is relatively simplistic. More advanced fusion techniques, including feature distribution matching [

64] and cross-attention-based fusion [

65], could be explored to enrich the representational power of the dual-branch framework. Third, the choices of backbone and SR architectures are not exhaustively evaluated. Integrating other promising modules, such as MobileMamba [

66], arbitrary-scale SR [

67], or uncertainty-aware models [

68], may further boost performance. Finally, the proposed framework lacks fine-grained optimization of hyperparameters and architectural configurations. A more systematic exploration of design choices could lead to additional performance gains in BIQA for UHD images.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G., Q.M. and Q.S.; Data curation, J.G. and Q.M.; Formal analysis, S.Y. and Q.S.; Funding acquisition, S.Y. and Q.S.; Investigation, S.Y. and Q.S.; Methodology, J.G., Q.M., S.Z. and Y.W.; Project administration, Q.S.; Software, J.G., Q.M., S.Z. and Y.W.; Supervision, Q.S.; Validation, S.Z. and Y.W.; Visualization, J.G., S.Z. and Y.W.; Writing - original draft, J.G. and S.Y.; Writing - review & editing, S.Y. and Q.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

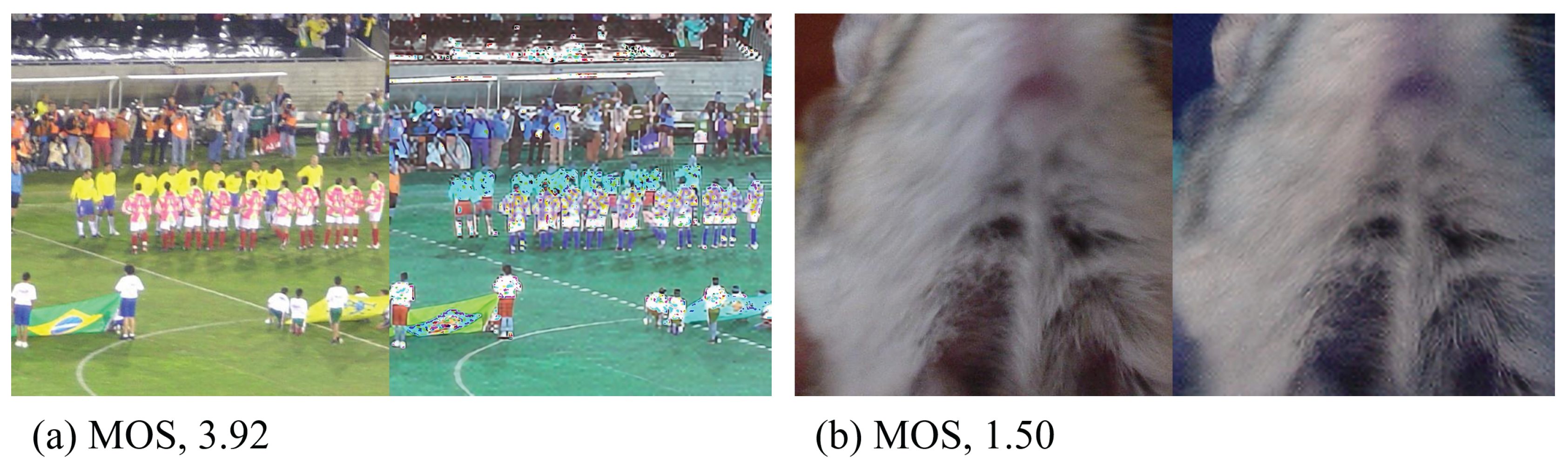

Figure 1.

Original images with varying MOS values and their corresponding SR reconstructed images (side by side). Interestingly, higher-quality images tend to exhibit more noticeable distortions after SR reconstruction.

Figure 1.

Original images with varying MOS values and their corresponding SR reconstructed images (side by side). Interestingly, higher-quality images tend to exhibit more noticeable distortions after SR reconstruction.

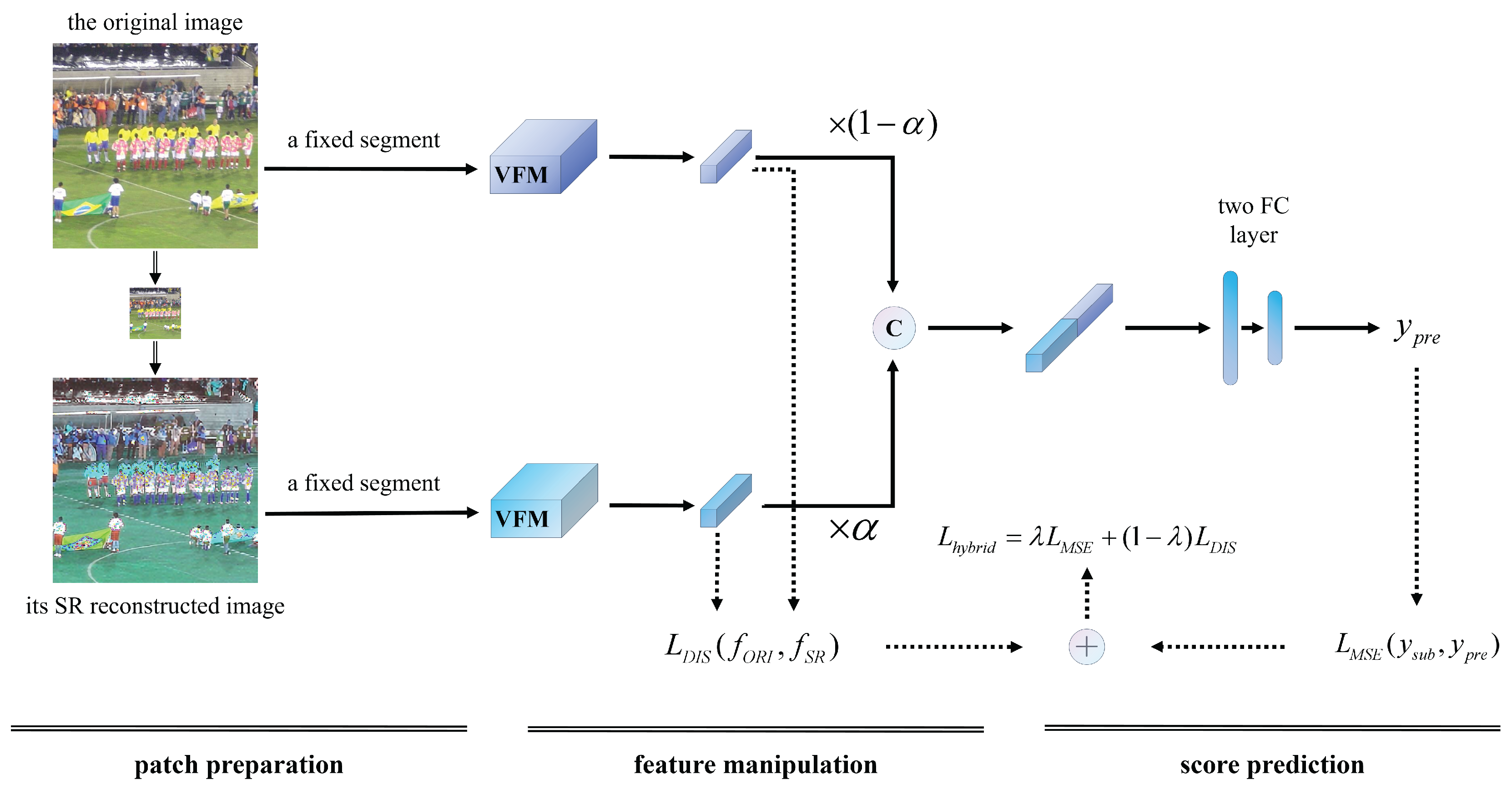

Figure 2.

The framework consists of two branches, each followed by a VFM backbone for feature extraction. Then, the output features are weighted and concatated as the input of a module with two FC layers. In model training, added to forms a hybrid loss function for guiding the model toward improved performance.

Figure 2.

The framework consists of two branches, each followed by a VFM backbone for feature extraction. Then, the output features are weighted and concatated as the input of a module with two FC layers. In model training, added to forms a hybrid loss function for guiding the model toward improved performance.

Figure 3.

Illustration of patch preparation. (a) An exemplary image with a resolution of 2560 × 1440, red squares and green squares denote the basic patches sized 16 × 16. (b) An image patch sized 384 × 384 composed of successive red patches. (c) An image patch sized 384 × 384 formed by successive green patches. Notably, these patches are uniformly sampled across the entire image. Throughout the training process, both the original and SR reconstructed images are subjected to an identical and fixed sampling strategy.

Figure 3.

Illustration of patch preparation. (a) An exemplary image with a resolution of 2560 × 1440, red squares and green squares denote the basic patches sized 16 × 16. (b) An image patch sized 384 × 384 composed of successive red patches. (c) An image patch sized 384 × 384 formed by successive green patches. Notably, these patches are uniformly sampled across the entire image. Throughout the training process, both the original and SR reconstructed images are subjected to an identical and fixed sampling strategy.

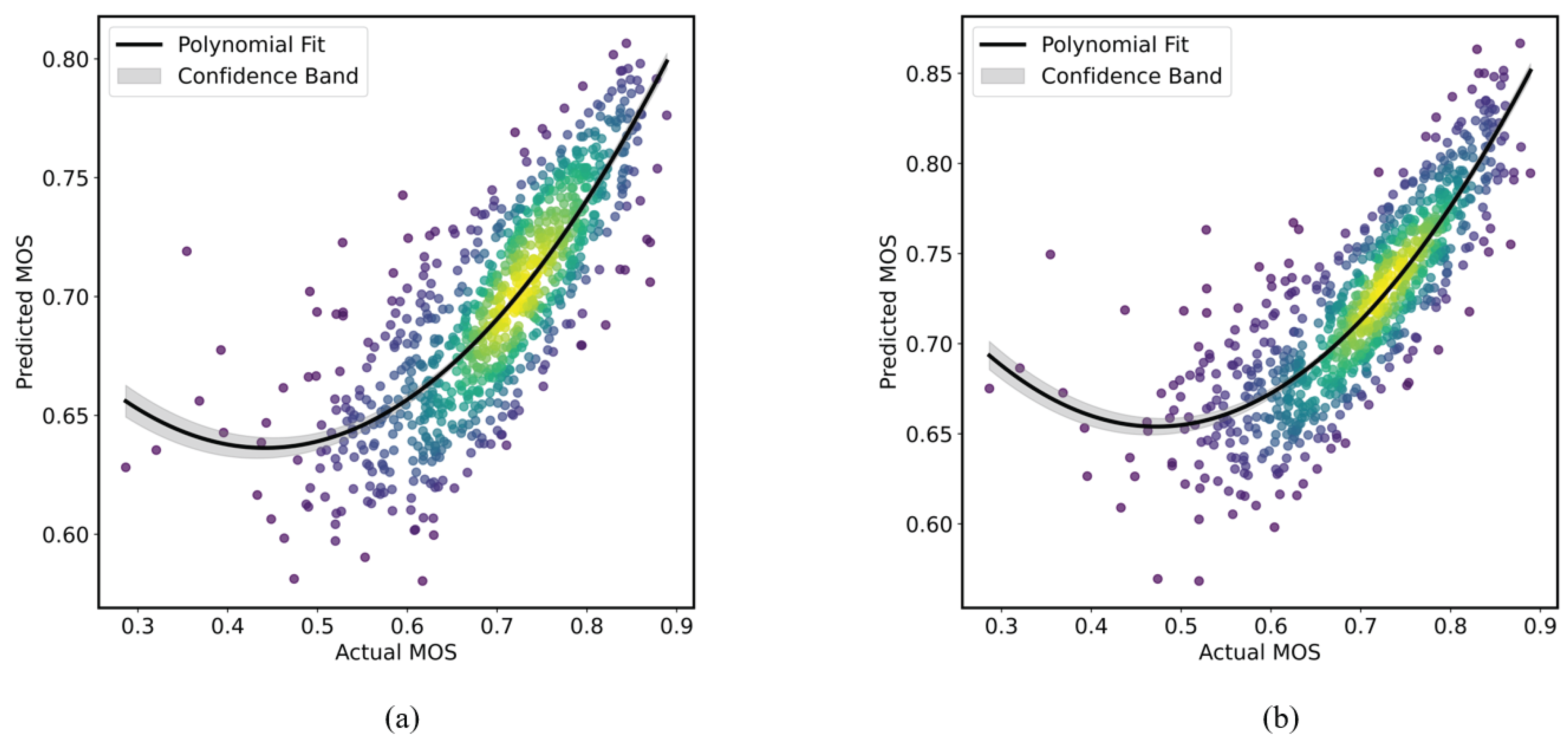

Figure 4.

Scatter plots of predicted MOS versus subjective MOS values: (a) The proposed SURPRIDE algorithm; (b) the SOTA model, UIQA. Each plot includes a quadratic fit line with confidence bands through Gaussian kernel density estimation.

Figure 4.

Scatter plots of predicted MOS versus subjective MOS values: (a) The proposed SURPRIDE algorithm; (b) the SOTA model, UIQA. Each plot includes a quadratic fit line with confidence bands through Gaussian kernel density estimation.

Table 1.

Summary of dataset configurations.

Table 1.

Summary of dataset configurations.

| |

Year |

No. of images |

Resolution |

MOS range |

Cropped resolution |

| UHD-IQA [9] |

2024 |

6,073 |

≈ 3840×2160 |

[0,1] |

2560×1440 |

| HRIQ [33] |

2024 |

1,120 |

2880×2160 |

[0,5] |

2560×1440 |

| CID [41] |

2014 |

474 |

1600×1200 |

[0,100] |

1600×1200 |

| KonIQ-10k [42] |

2020 |

10,073 |

1024×768 |

[0,5] |

1024×768 |

| CLIVE [8] |

2015 |

1,162 |

≈ 500×500 |

[0,100] |

496×496 |

| BIQ2021 [40] |

2021 |

12,000 |

≈ 512×512 |

[0,1] |

512×512 |

Table 2.

Achievement on the AIM 2024 Challenge using official data splitting.

Table 2.

Achievement on the AIM 2024 Challenge using official data splitting.

|

on the testing set |

on the validation set |

| |

PLCC |

SRCC |

PLCC |

SRCC |

| SJTU |

0.7985 |

0.8463 |

0.8238 |

0.8169 |

| GS-PIQA |

0.7925 |

0.8297 |

0.8192 |

0.8092 |

| CIPLAB |

0.7995 |

0.8354 |

0.8136 |

0.8063 |

| EQCNet |

0.7682 |

0.7954 |

0.8285 |

0.8234 |

| MobileNet-IQA |

0.7558 |

0.7883 |

0.7831 |

0.7757 |

| NF-RegNets |

0.7222 |

0.7715 |

0.7968 |

0.7897 |

| CLIP-IQA |

0.7116 |

0.7305 |

0.7069 |

0.6918 |

| ICL |

0.5206 |

0.5166 |

0.5217 |

0.5101 |

| SURPRIDE (ours) |

0.7755 |

0.8133 |

0.7983 |

0.7930 |

Table 3.

Dual-branch settings on the UHD-IQA database.

Table 3.

Dual-branch settings on the UHD-IQA database.

| |

PLCC |

SRCC |

PLCC |

SRCC |

| Original branch |

SR branch |

| DeiT [53] |

ConvNeXt [54] |

| DeiT [53] |

0.7188 |

0.7390 |

0.6769 |

0.7054 |

| ConvNeXt [54] |

0.7695 |

0.8073 |

0.7755 |

0.8133 |

Table 4.

Effect of input image sizes on the UHD-IQA database.

Table 4.

Effect of input image sizes on the UHD-IQA database.

| dual branches |

input size |

UHD-IQA [9] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

| ConvNeXt |

224 × 224 |

0.7510 |

0.7847 |

| 384 × 384 |

0.7755 |

0.8133 |

Table 5.

Selection of SR reconstruction methods and scaling factors.

Table 5.

Selection of SR reconstruction methods and scaling factors.

| SR method |

scaling factors |

UHD-IQA [9] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

| SwinFIR [55] |

× 2 |

0.7722 |

0.8098 |

| × 4 |

0.7755 |

0.8133 |

| HAT [56] |

× 2 |

0.7665 |

0.8111 |

| × 4 |

0.7765 |

0.8095 |

Table 6.

Effect of parameter configurations of and on the UHD-IQA database.

Table 6.

Effect of parameter configurations of and on the UHD-IQA database.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.766/0.801 |

0.781/0.823 |

0.776/0.813 |

0.762/0.799 |

0.774/0.813 |

|

0.751/0.793 |

0.763/0.804 |

0.769/0.807 |

0.774/0.811 |

0.773/0.816 |

|

0.758/0.796 |

0.778/0.811 |

0.781/0.816 |

0.784/0.819

|

0.774/0.818 |

Table 7.

Effect of patch sizes for the fixed input segments.

Table 7.

Effect of patch sizes for the fixed input segments.

| patch sizes |

UHD-IQA [9] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

| 8 × 8 |

0.7741 |

0.8039 |

| 16 × 16 |

0.7755 |

0.8133 |

| 32 × 32 |

0.7720 |

0.8140 |

Table 8.

Effect of input resolution and SR branch.

Table 8.

Effect of input resolution and SR branch.

| input size |

SR branch |

UHD-IQA [9] |

CLIVE [8] |

KonIQ-10k [42] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

PLCC |

SRCC |

PLCC |

SRCC |

| 224 × 224 |

w/o |

0.7514 |

0.7855 |

0.8241 |

0.7993 |

0.9200 |

0.9082 |

| w |

0.7510 |

0.7847 |

0.8764 |

0.8431 |

0.9234 |

0.9113 |

| 384 × 384 |

w/o |

0.7682 |

0.8029 |

0.8948 |

0.8551 |

0.9358 |

0.9258 |

| w |

0.7755 |

0.8133 |

0.9024 |

0.8662 |

0.9360 |

0.9269 |

Table 9.

Effect of the loss function.

Table 9.

Effect of the loss function.

| input size |

|

UHD-IQA [9] |

CLIVE [8] |

KonIQ-10k [42] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

PLCC |

SRCC |

PLCC |

SRCC |

| 224 × 224 |

w/o |

0.7002 |

0.7327 |

0.8492 |

0.8255 |

0.9232 |

0.9104 |

| w |

0.7510 |

0.7847 |

0.8764 |

0.8431 |

0.9234 |

0.9113 |

| 384 × 384 |

w/o |

0.7701 |

0.8077 |

0.8990 |

0.8642 |

0.9389 |

0.9299 |

| w |

0.7755 |

0.8133 |

0.9024 |

0.8662 |

0.9360 |

0.9269 |

Table 10.

Achievement on the HRIQ database.

Table 10.

Achievement on the HRIQ database.

| |

year |

HRIQ [33] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

| HyperIQA [19] |

2020 |

0.848 |

0.848 |

| MANIQA [25] |

2022 |

0.824 |

0.824 |

| HR-BIQA [33] |

2024 |

0.925 |

0.920 |

| TD-HRNet [59] |

2025 |

0.856 |

0.861 |

| SURPRIDE (ours) |

2025 |

0.882 |

0.873 |

Table 11.

Achievement on the CID database.

Table 11.

Achievement on the CID database.

| |

year |

CID [41] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

| MetaIQA [44] |

2020 |

0.7840 |

0.7660 |

| DACNN [45] |

2022 |

0.9280 |

0.9060 |

| GCN-IQD [46] |

2023 |

0.9211 |

0.9095 |

| MFFNet [47] |

2024 |

0.9560 |

0.9530 |

| SURPRIDE (ours) |

2025 |

0.9635 |

0.9647 |

Table 12.

Performance on the KonIQ-10k database.

Table 12.

Performance on the KonIQ-10k database.

| |

year |

KonIQ-10k [42] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

| HyperIQA [19] |

2020 |

0.9170 |

0.9060 |

| TReS [49] |

2022 |

0.9280 |

0.9150 |

| ReIQA [48] |

2023 |

0.9230 |

0.9140 |

| QCN [50] |

2024 |

0.9450 |

0.9340 |

| ATTIQA [30] |

2024 |

0.9520 |

0.9420 |

| GMC-IQA [51] |

2024 |

0.9471 |

0.9325 |

| Prompt-IQA [52] |

2024 |

0.9430 |

0.9287 |

| SGIQA [26] |

2024 |

0.9510 |

0.9420 |

| SURPRIDE (ours) |

2025 |

0.9360 |

0.9269 |

Table 13.

Performance on the CLIVE database.

Table 13.

Performance on the CLIVE database.

| |

year |

CLIVE [8] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

| HyperIQA [19] |

2020 |

0.8820 |

0.8590 |

| TReS [49] |

2022 |

0.8770 |

0.8460 |

| ReIQA [48] |

2023 |

0.8540 |

0.8400 |

| ATTIQA [30] |

2024 |

0.9160 |

0.8980 |

| GMC-IQA [51] |

2024 |

0.9225 |

0.9062 |

| Prompt-IQA [52] |

2024 |

0.9280 |

0.9125 |

| SGIQA [26] |

2024 |

0.9160 |

0.8940 |

| QCN [50] |

2024 |

0.8930 |

0.8750 |

| SURPRIDE (ours) |

2025 |

0.9024 |

0.8662 |

Table 14.

Performance on the BIQ2021 database.

Table 14.

Performance on the BIQ2021 database.

| |

year |

BIQ2021 [40] |

| PLCC |

SRCC |

| CELL [5] |

2023 |

0.713 |

0.710 |

| PDAA [61] |

2023 |

0.782 |

0.638 |

| CFFA [62] |

2024 |

0.669 |

0.802 |

| IQA-NRTL [60] |

2025 |

0.895 |

0.850 |

| SURPRIDE (ours) |

2025 |

0.891 |

0.895 |