1. BPD, PTSD, and cPTSD: Diagnoses, Theoretical Models, and Clinical Overlap

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and Complex PTSD (cPTSD) are three interrelated psychopathological conditions. Although they share some symptomatic dimensions, each disorder features distinct characteristics that shape their clinical profiles. Recent research has focused on these specific traits to enhance diagnostic clarity and inform treatment strategies.

BPD [

1] is classified among personality disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 1–2% in the general population and substantially higher rates in clinical settings (10–20%), making it one of the most frequently diagnosed personality disorders [

2]. According to the categorical model of the DSM-5-TR, BPD is diagnosed by meeting five out of nine main criteria, including: (1) frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment, (2) unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, (3) identity and self-image disturbances, (4) impulsivity in at least two self-damaging areas, (5) recurrent self-harming behavior and/or suicidal ideation, (6) affective instability due to marked mood reactivity, (7) chronic feelings of emptiness, (8) inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger, and (9) transient dissociative symptoms or stress-related paranoid ideation [

1]. This diagnostic threshold results in a highly heterogeneous symptom profile, allowing patients with markedly different presentations to fall under the same diagnostic category [

3].

The Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (AMPD) in the DSM-5-TR approaches BPD through two main criteria: (A) the level of personality functioning—evaluating impairments in identity, empathy, intimacy, and self-direction—and (B) maladaptive personality traits, such as emotional lability, impulsivity, hostility, among others. AMPD conceptualizes BPD as resulting from the interplay between an unstable sense of self—marked by self-criticism, emptiness, and dissociation—and problematic interpersonal functioning, often characterized by extreme idealization or devaluation [

1]. This dimensional approach helps capture the disorder’s complexity and allows for more tailored therapeutic interventions [

4].

Linehan’s biosocial theory [

5] conceptualizes BPD as a disorder of emotion dysregulation arising from the interaction between a

biological vulnerability - characterized by high emotional sensitivity, reactivity, and a slow return to baseline [

6] - and an

invalidating environment [

7], which reinforces emotional and behavioral difficulties. This model aligns with key components of AMPD Criteria A and B, particularly emotional lability and impulsivity, considering them central to BPD development. However, emerging evidence suggests that the biosocial model may extend beyond BPD, encompassing a broader range of disorders characterized by emotion dysregulation [

4].

As previously noted, BPD shares considerable symptom overlap with PTSD [

8,

9] and with cPTSD [

8,

9,

10]. Indeed, approximately 30% of BPD patients also meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD, and nearly 50% for cPTSD [

11,

12], as confirmed by recent systematic reviews [

13]. This comorbidity may be attributed to shared symptoms across the three disorders, such as emotional hyperreactivity and interpersonal difficulties. Nevertheless, PTSD is typically linked to a single traumatic event, with symptoms including intrusive recollections, avoidance, hypervigilance, and negative alterations in mood and cognition [

1]. In contrast, BPD involves chronic dysfunction not necessarily tied to one traumatic episode [

14,

15]. Zlotnick and colleagues [

16] found that among individuals with comorbid BPD and PTSD, childhood trauma was more strongly associated with symptom severity than in those with BPD alone. This suggests that PTSD may amplify clinical complexity and general dysfunction in BPD without altering its core traits.

When PTSD symptoms include disturbances in self-organization (DSO), the diagnosis of Complex PTSD (cPTSD) may apply. DSO encompasses (1) pervasive emotion dysregulation, (2) a profoundly negative self-concept marked by shame and worthlessness, and (3) chronic relational disturbances, such as isolation and difficulty forming stable bonds. The key distinction of cPTSD lies in exposure to prolonged, repeated trauma—particularly interpersonal trauma like emotional, physical, or sexual abuse during childhood. The high prevalence of cPTSD in BPD patients [

11] has led some authors to conceptualize cPTSD as a trauma-related subtype of BPD [

10,

17,

18]. However, the specific DSO symptoms are relatively distinct from those of BPD [

19,

20]. In cPTSD, emotion dysregulation presents as chronic self-regulation difficulties and emotional numbing, rather than the intense mood swings and explosive anger seen in BPD [

9]. Furthermore, the negative self-concept in cPTSD is defined by stable, enduring feelings of shame and guilt, contrasting with the unstable and fragmented self-image in BPD. Lastly, while both disorders involve relational difficulties, BPD is marked by intense, alternating patterns of idealization and devaluation to prevent abandonment, whereas cPTSD reflects avoidance rooted in fear of intimacy [

19].

Table 1 summarizes the key differences between PTSD, cPTSD, and BPD in relation to the variables examined in this study.

According to the model proposed by Bohus and colleagues [

21], Complex PTSD (cPTSD) is characterized by two distinct forms of traumatization: (1) repeated experiences of physical or sexual violence, and (2) traumatic invalidation by caregivers, both of which give rise to specific emotional and behavioral patterns [

21,

22]. During the traumatic experience, sensory, emotional, and cognitive impressions are thought to form traumatic networks that contribute to the development of the negative self-concept typical of the disorder, often associated with emotions such as guilt, shame, and disgust. Subsequently, social invalidation hinders the individual’s ability to disclose the trauma, leading to social withdrawal and interpersonal difficulties. In a feedback-loop process, these effects give rise to dysfunctional coping strategies—such as emotional avoidance and detachment—that provide temporary relief but also perpetuate the traumatic experience. These traumatic networks may later be reactivated by internal or external cues, and the renewed experience is further reinforced by the patient's ongoing social isolation, thereby strengthening negative cognitive-emotional schemas and maintaining emotional and relational distress.

1.1. Emotion Dysregulation in BPD, PTSD, and cPTSD

Emotion dysregulation lies at the core of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and is the primary target of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; [

5]). Although also present in PTSD and cPTSD, it manifests in different ways and to varying degrees of severity [

9].

In BPD, the interplay between biological and environmental vulnerabilities [

5] leads to a chronic inability to modulate intense emotional states. This dysregulation is considered ego-syntonic (i.e., experienced as an integral part of the self) and is often triggered by interpersonal situations perceived as invalidating or threatening [

5,

8,

9]. It reflects a structural instability of identity, a hallmark of BPD [

1,

15], which appears to be strongly correlated with Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), particularly emotional abuse and emotional neglect [

23]. In this regard, a specific analysis by Alafia and Manjula [

24] highlighted a significantly higher prevalence of emotional abuse in individuals with BPD compared to clinical control groups, and a substantial association with the development of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. These maladaptive strategies have been identified as key predictors of negative affective states such as anger and sadness [

24].

In PTSD, emotion dysregulation tends to be more specifically linked to traumatic memories and triggers that reactivate the trauma. It is frequently characterized by intense emotional states such as anger, fear, or shame that emerge during flashbacks or in response to trauma-related stimuli [

1]. Unlike BPD, dysregulation in PTSD is ego-dystonic (i.e., experienced as alien to the self and closely tied to the traumatic event [

8]).

In cPTSD, emotion dysregulation is more persistent and generalized than in PTSD. It involves not only difficulties in modulating negative emotions such as fear and anger, but also a chronic sense of worthlessness and shame that extends to self-perception and interpersonal functioning [

25]. It is closely associated with repeated and prolonged interpersonal trauma, which impairs the individual’s capacity to develop adaptive emotional regulation strategies [

8,

10]. As such, cPTSD is marked by a profound and structural impairment in emotional self-regulation, an element it shares with BPD. Although the overlap between cPTSD and BPD is substantial, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) studies have revealed that cPTSD symptoms are more closely related to avoidance and relational disconnection, whereas BPD is marked by heightened emotional and relational instability and impulsive behavior [

20]. These findings underscore the importance of a precise diagnostic approach that takes into account both the shared features and the differences between the disorders, thereby enhancing the understanding of their interrelations and supporting trauma-focused interventions.

1.2. Dissociation in BPD, PTSD, and cPTSD

Dissociation is defined in the DSM-5-TR as a "disruption and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior" [

1]. From an evolutionary and pathogenetic perspective, dissociation appears to represent the human organism’s extreme response to intolerable stress, particularly in the context of severe abuse [

26].

Since the work of Kernberg [

27], dissociation has been conceptualized as an alteration of consciousness and a fragmentation of mental experience, serving an adaptive function in promoting individual survival. This definition has largely remained consistent across different schools of psychotherapy. In the context of BPD, Linehan reconceptualized dissociation as an extreme form of experiential avoidance [

28], employed by patients in response to aversive tension states that are perceived as unbearable [

5]. The notion of dissociation as experiential avoidance continues to be supported by empirical research on BPD. For instance, a meta-analytic review by Cavicchioli and colleagues [

29] confirmed this function across multiple studies. Furthermore, the presence of dissociation has been found to predict poorer outcomes in DBT treatment among women with BPD [

30].

The link between dissociation and trauma is robust in both Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and Dissociative Disorders (DD; [

31]), particularly when viewed within a multifactorial etiological framework. A growing body of evidence suggests that Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and disorganized attachment are common among individuals with DD, BPD, and cPTSD [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. However, patients with BPD tend to exhibit higher levels of dissociation compared to individuals with other psychiatric or personality disorders [

38], though not when compared to those with DD or PTSD [

39]. This finding may be understood in light of the differing functions that dissociation serves across these disorders.

Specifically, in BPD, dissociation may reflect an acute, situational response to stress [

40,

41], serving to manage aversive emotional states in the moment, without constituting a structural or stable personality feature [

42]. In contrast, in DD, dissociation is a structural element of personality, functioning to protect the individual from traumatic emotions or memories by creating significant compartmentalization within consciousness, identity, and memory [

43,

44]. Finally, in PTSD, dissociation serves to shield the individual from the traumatic memory. Although it is less chronic than in DD, it is more specifically related to trauma than in BPD [

10,

45].

In cPTSD, dissociation often manifests as a combination of hyperarousal and hypoarousal, with marked difficulty regulating both positive and negative emotional states. Unlike PTSD, dissociation in cPTSD is closely tied to persistent emotional and relational disorganization, attributed to chronic and prolonged interpersonal trauma [

8].

One of the outstanding questions in current research on dissociative symptomatology concerns which specific features of BPD are most strongly associated with dissociation [

42]. The present study aims to contribute new evidence on this issue as well.

1.3. Adverse Childhood Experiences in BPD, PTSD, and cPTSD

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) encompass a wide range of traumatic experiences occurring during childhood, including severe forms of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, neglect, chronic maltreatment, and invalidating environments [

46]. These often cumulative experiences can profoundly impact a child’s psychological, emotional, and neurobiological development, disrupting the ability to regulate emotions, form stable relationships, and develop a coherent and positive sense of self. The effects of ACEs are not limited to childhood but often persist into adulthood, increasing vulnerability to a broad spectrum of psychopathologies, including BPD, PTSD, and cPTSD [

10,

47]. Their relevance has been extensively studied in both clinical and research settings, consistently identifying ACEs as significant risk factors for long-term emotional and behavioral difficulties.

Patients with BPD are 13 times more likely to report ACEs compared to non-clinical controls and other clinical populations (e.g., mood disorders, psychosis, and other personality disorders; [

48], highlighting the central role of ACEs in the development of the disorder [

49]. However, not all ACEs exert the same impact. While traumatic events such as physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, neglect, and domestic violence are linked to a greater risk of developing personality disorders in adulthood [

47], in BPD, emotional abuse has been found to have the most direct and significant association [

24], followed closely by emotional neglect [

23]. The evidence regarding the role of sexual abuse is more nuanced. While some studies suggest that sexual abuse is a significant predictor of adult dissociative phenomena—pointing to a specific link between dissociation and sexual trauma (see [

50] for a literature review)—more recent findings suggest a more indirect relationship, potentially mediated by other factors such as insecure attachment [

49]. This study also aims to shed light on the relationship between sexual abuse, borderline symptomatology, and dissociative and post-traumatic symptoms.

In PTSD, ACEs primarily contribute to the emergence of symptoms related to exposure to single or episodic traumatic events, such as hyperarousal, intrusive traumatic memories, and avoidance behaviors [

51]. These symptoms reflect emotional regulation dysfunctions and heightened hypervigilance, which undermine trust in others. While ACEs in PTSD are impactful, their effect tends to be less pervasive than in cPTSD, leading to more circumscribed difficulties rather than widespread and chronic emotional dysregulation [

52]. Nonetheless, ACEs remain a critical vulnerability factor, influencing maladaptive emotional responses and psychological functioning, and highlighting the importance of addressing these factors in clinical interventions.

In cPTSD, ACEs—especially when prolonged and repeated—have a profound impact on personality functioning and epistemic trust [

52], understood as the ability to trust and learn from social information. Impaired epistemic trust hinders the individual’s capacity to revise self-perceptions and worldviews through positive social interactions, thereby intensifying interpersonal difficulties and the negative self-concept that typify cPTSD. Specifically, the three hallmark Disturbances in Self-Organization (DSO)—emotional dysregulation, negative self-concept, and chronic interpersonal difficulties—emerge from the interplay between multiple, enduring ACEs and impaired personality functioning. Kampling and colleagues [

52], in their study on British military veterans, found that those with high exposure to ACEs exhibited more severe cPTSD symptoms, including pronounced DSO, and reported lower levels of perceived social support. These findings underscore the protective role of social support, the absence of which may contribute to the chronic course of the disorder.

1.3. DBT-PTSD Treatment

The overlap among BPD, PTSD, and cPTSD underscores the need for integrated therapeutic approaches. Treatments such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy for PTSD (DBT-PTSD) combine emotion regulation strategies with trauma-processing techniques and have shown effectiveness in reducing symptoms across all three disorders [

21,

22,

53]. DBT-PTSD is a targeted adaptation of standard DBT, developed specifically to address cPTSD—particularly in patients with histories of childhood abuse and comorbid conditions such as BPD. This treatment approach emerged in response to the limited effectiveness of standard DBT in alleviating PTSD symptoms in patients with BPD. Initial studies revealed that while standard DBT was successful in enhancing emotion regulation and reducing self-harming behaviors, it failed to adequately address the intrusive and dissociative symptoms characteristic of PTSD [

22].

DBT-PTSD integrates core principles of DBT with trauma-specific interventions such as

in sensu exposure, allowing patients to process traumatic emotions and memories within a secure therapeutic context. The treatment is structured into phases that include crisis management, psychoeducation on trauma, skills training for distress tolerance and emotion regulation, and guided trauma exposure [

53]. During exposure, emphasis is placed on developing a coherent trauma narrative and reducing physiological arousal and emotional and behavioral avoidance.

Clinical trials have demonstrated that DBT-PTSD significantly reduces post-traumatic and dissociative symptoms, as well as self-injurious and suicidal behaviors, even in outpatient settings. In a multicenter study [

21], patients receiving DBT-PTSD showed greater symptom remission compared to those treated with Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), along with marked improvements in quality of life and emotion regulation.

A distinctive feature of DBT-PTSD is the balance between acceptance and change, central to standard DBT [

5], which involves combining validation strategies with interventions aimed at transforming trauma-related negative beliefs. This flexible approach allows for effective management of the complex symptomatology of post-traumatic disorders and the dynamic interplay among past trauma, emotion regulation, and dysfunctional relational schemas. The therapy is designed to be highly adaptable, meeting the individual needs of patients [

22].

1.4. The Present Study

Building on the existing body of literature, the present study aims to address the following research question: How do different dimensions of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) influence key psychopathological domains, namely emotion dysregulation, dissociation, and borderline symptomatology?

To this end, the research hypotheses to be tested through bivariate correlation analysis and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) are as follows:

- 1)

Different dimensions of ACEs are expected to be positively and significantly correlated with levels of post-traumatic symptomatology, dissociative symptomatology, borderline symptoms, and emotion dysregulation.

- 2)

Levels of dissociative symptoms are hypothesized to be highly correlated with post-traumatic symptomatology, whereas levels of emotion dysregulation are expected to be strongly correlated with borderline symptomatology.

- 3)

Emotional abuse and emotional neglect are hypothesized to be the ACE dimensions with the greatest impact on emotion dysregulation and borderline symptoms.

- 4)

Sexual abuse is hypothesized to be a positive and significant predictor of dissociative symptoms, reflecting a specific link between dissociation and sexual trauma in patients with BPD.

Additionally, Explorative Graph Analysis will be used to explore the following research questions:

- 1)

Which psychopathological factors emerge as central nodes within the symptom network of the tested sample?

- 2)

Are there patterns that diverge from previously validated measurement structures, thereby suggesting novel latent configurations?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 83 patients (76 females, 7 males) were assessed for the present study between 2019 and 2024.

Participants were voluntarily recruited in a DBT Psychotherapy Center in Padua (Italy), based on the following inclusion criteria: Being 18 years of age or older, being a native Italian speaker, having normative cognitive functioning, and having received a clinical diagnosis of BPD.

2.2. Measures

All participants were administered the Raven's Progressive Matrices [

54] to ensure normative cognitive functioning. Subsequently, the following self-report questionnaires were used to assess the constructs relevant to our research questions:

- -

Borderline Symptom List–23 (BSL-23; [

55]): A short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-95), developed to reliably and efficiently assess symptoms typical of Borderline Personality Disorder. The Italian version consists of 18 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“

not at all”) to 4 (“

very much”), measuring symptom severity over the past week. The BSL-23 is designed to be highly sensitive to therapeutic change and to effectively discriminate between patients with BPD and those with other psychiatric diagnoses. The scale has shown excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .89).

- -

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire–Short Form (CTQ-SF; [

56,

57]): A retrospective self-report instrument for measuring childhood trauma. It consists of 28 items assessing five specific dimensions of ACEs: emotional abuse (CTQ_emoab, 5 items, α = .79), physical abuse (CTQ_phyab, 5 items, α = .82), sexual abuse (CTQ_sexab, 5 items, α = .91), emotional neglect (CTQ_emoneg, 5 items, α = .90), and physical neglect (CTQ_phyneg, 5 items, α = .67). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“

never true”) to 5 (“

very often true”). The scale’s convergent validity is supported by moderate correlations with post-traumatic and general psychopathological symptoms (Sacchi et al., 2018).

- -

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; [

23,

58]): A self-report questionnaire designed to assess difficulties in emotion regulation. It includes 36 items divided into six subscales that assess clinically relevant aspects of emotion dysregulation: Non-acceptance of emotional responses (DERS_non, 6 items, α = .90), difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior (DERS_go, 5 items, α = .80), impulse control difficulties (DERS_im, 6 items, α = .90), lack of emotional awareness (DERS_aw, 6 items, α = .85), limited access to emotion regulation strategies (DERS_st, 8 items, α = .91), and lack of emotional clarity (DERS_cl, 5 items, α = .86). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“

never”) to 5 (“

always”).

- -

Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES [

59,

60]): A self-report instrument composed of 28 items designed to measure the frequency of dissociative experiences in clinical and non-clinical populations. Participants rate each item on a visual analog scale from 0% to 100%. The DES assesses three primary dissociative dimensions: absorption and imaginative involvement (DES_assco, 9 items, α = .84), dissociative amnesia and behavioral lapses (DES_adiss, 8 items, α = .81), and depersonalization/derealization (DES_depder, 6 items, α = .88). The DES can be used to detect both non-pathological and pathological dissociative symptoms.

- -

Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale 3 (PDS-3; [

61]): A 24-item self-report measure (PDS_tot, α = .89) that assesses the severity of PTSD symptoms over the past month, based on DSM-IV criteria. It evaluates symptom clusters such as intrusive thoughts, avoidance behaviors, and hyperarousal. According to the literature, the PDS-3 is a psychometrically sound instrument for PTSD screening under DSM-IV-R criteria. It is particularly recommended in large-scale traumatic events such as natural disasters or mass terrorism.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the open-source statistical software R (version 4.4.2).

Following an initial exploration of descriptive statistics for the sample, bivariate correlations among measured variables were computed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. In particular, the corrplot package was employed to intuitively visualize correlations between questionnaire scores (CTQ, DERS, BSL-23, DES, and PDS), including their subscales, through a correlogram.

For the analysis using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM; [

62]), the

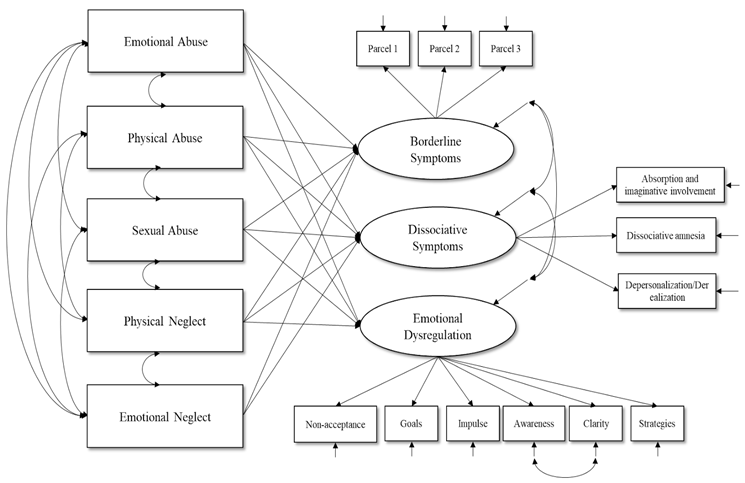

lavaan package [

63] was utilized. The following measurement models were specified.

For borderline symptomatology (BSL), three parcels (each composed of 6 items) were created.

For emotion dysregulation (DERS), a facet-representative approach was used. The latent variable was composed by 6 observed variables, each representing the composite score (i.e., the average of their respective items) of the six dimensions of DERS: (1) Internal state awareness (awareness subscale, DERS_aw), (2) acceptance of internal states (non-acceptance subscale, DERS_non), (3) understanding of emotional responses (clarity subscale, DERS_cl), (4) ability to engage in goal-directed behavior (goals subscale, DERS_go), (5) impulsivity (impulse subscale, DERS_im), and (6) access to effective strategies (strategies subscale, DERS_st).

The same facet-representative approach was applied to dissociative symptomatology (DES), which includes three specific dimensions: (1) absorption and imaginative involvement (DES_assco), (2) dissociative amnesia and behavioral lapses (DES_adiss), and (3) depersonalization and derealization (DES_depder).

The ACEs (via the CTQ) were instead measured by five distinct observed variables, which were computed as the mean of items from each subscale: (1) physical abuse (CTQ_phyab), (2) emotional abuse (CTQ_emoab), (3) sexual abuse (CTQ_sexab), (4) physical neglect (CTQ_phyneg), and (5) emotional neglect (CTQ_emoneg).

Once the measurement models for each construct were defined, the structural model was specified by regressing the latent psychopathology variables (i.e., borderline symptoms, dissociative symptoms, and emotion dysregulation) on the observed ACE variables (i.e., emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect). Model fit was evaluated using chi-square statistics (a non-significant result at α = .05, i.e., p > .05, indicates good fit) and the following indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI; values > .90), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; values > .90), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; values < .06), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR; values < .08).

Finally, Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA) was used to obtain additional insights into the latent factorial structure of the observed variables. Unlike SEM, which tests a predefined structure (i.e., confirmatory or theory-driven approach), EGA identifies factor structures without a priori specification (i.e., exploratory or data-driven approach), using methods from network science [

64]. EGA involves three steps: (1) Estimation of the Correlation Matrix to assess linear relationships among variables; (2) Application of the GLASSO algorithm to build a sparse partial correlation network, highlighting only the strongest associations; and (3) Community Detection and Factor Estimation to cluster items into groups representing latent constructs with strong internal associations. The

EGAnet package in R was used for this analysis.

3. Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables considered in the current sample.

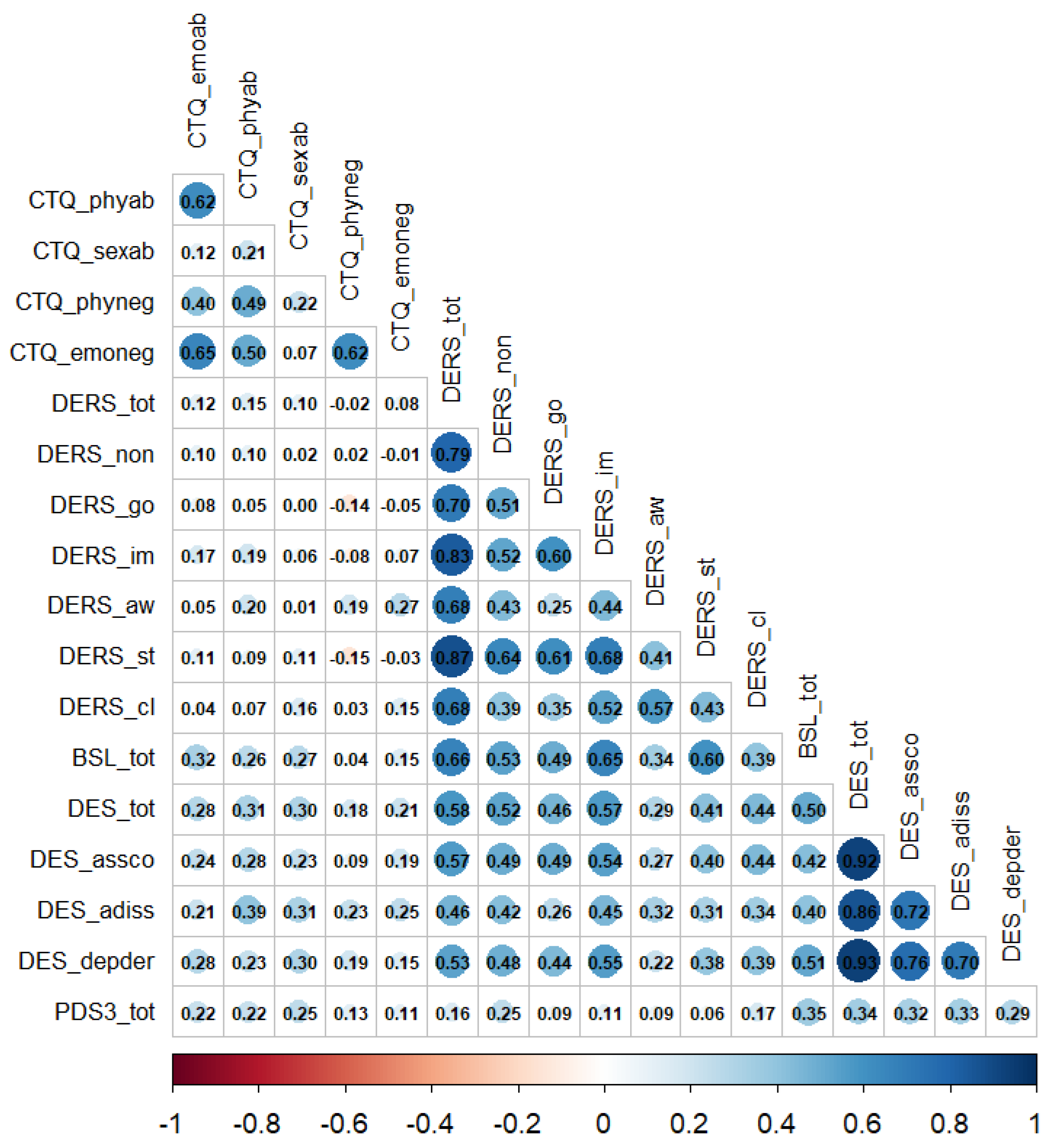

The correlogram in

Figure 1 displays the correlations among the various psychopathological variables examined in this study. Bivariate relationships between variables were assessed using zero-order Pearson correlations, with the significance level set at α = .05.

The results of the bivariate correlation analyses suggest the following:

Different dimensions of ACEs show low-to-moderate positive correlations with post-traumatic symptomatology (PDS3_tot, range r = .11–.25), moderate correlations with dissociative symptoms (DES_tot, range r = .18–.31), and low-to-moderate positive correlations with borderline symptomatology (BSL_tot, range r = .04–.32). Correlations with emotion dysregulation (DERS_tot) were very low (range r = –.02 to .15). These findings are consistent with Hypothesis 1, indicating that the strongest associations are observed with dissociative and borderline symptoms.

Dissociative symptomatology showed a strong correlation with post-traumatic symptoms (PDS3_tot, r = .40), thereby supporting Hypothesis 2. Moreover, dissociative symptoms were also significantly associated with borderline symptomatology (BSL_tot, r = .61), suggesting that dissociation is a salient feature in patients with BPD, often linked to prior traumatic experiences. Levels of emotion dysregulation were strongly correlated with the severity of borderline symptoms (BSL_tot, r = .66), also confirming Hypothesis 2, and with dissociative symptoms (DES_tot, r = .58). These results underscore that emotional difficulties represent a central component in the development and expression of both borderline and dissociative psychopathology.

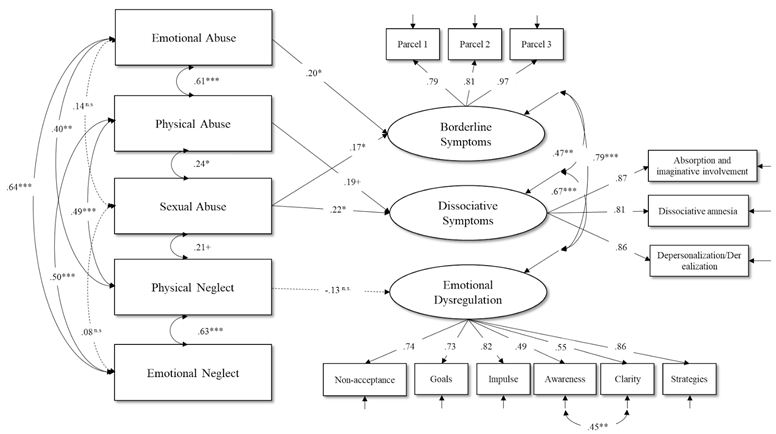

3.1. Structural Equation Models (SEM)

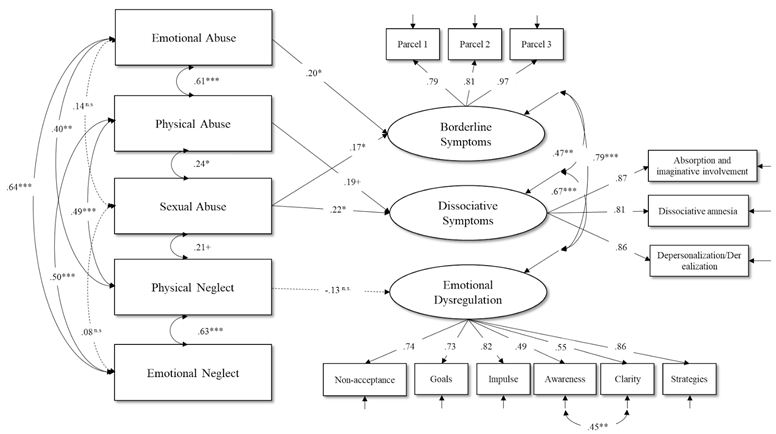

The analysis of the structural part of the model was conducted in two phases. In Model 1 (see Figure A1 in the Appendix), it was specified that the three latent outcome variables were regressed on all CTQ subscales. In Model 2 (see Figure A2 in the Appendix), all paths whose standardized estimates had an absolute value less than .20 were fixed to zero. Both models were tested using the Maximum Likelihood estimation method, with a total of 78 observations (out of 83 available). In both models, the main fit indices suggest an acceptable fit of the model to the data (Model 1: χ² = 136.713, df = 95, p = .003, CFI = 0.945, TLI = 0.921, RMSEA = 0.075, SRMR = 0.060; Model 2: χ² = 143.340, df = 105, p = .008, CFI = 0.949, TLI = 0.934, RMSEA = 0.068, SRMR = 0.091).

Partial support was found for Hypothesis 3: emotional abuse (CTQ_emoab) significantly and positively predicted borderline symptomatology (BSL_tot, β = .20, p < .05). However, no significant effects were observed for emotional abuse (CTQ_emoab) on emotion dysregulation, nor for emotional neglect (CTQ_emoneg) on borderline symptomatology (BSL_tot) or emotion dysregulation (DERS_tot).

In support of Hypothesis 4, the effect of sexual abuse (CTQ_sexab) on dissociative symptomatology (DES_tot) was positive and statistically significant (β = .22, p < .05). Additional interesting results from the SEM analysis include a positive and marginally significant effect of physical abuse (CTQ_phyab) on dissociative symptoms (DES_tot, β = .19, p < .10), and a significant effect of sexual abuse (CTQ_sexab) on borderline symptomatology (BSL_tot, β = .17, p < .05).

3.2. Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA)

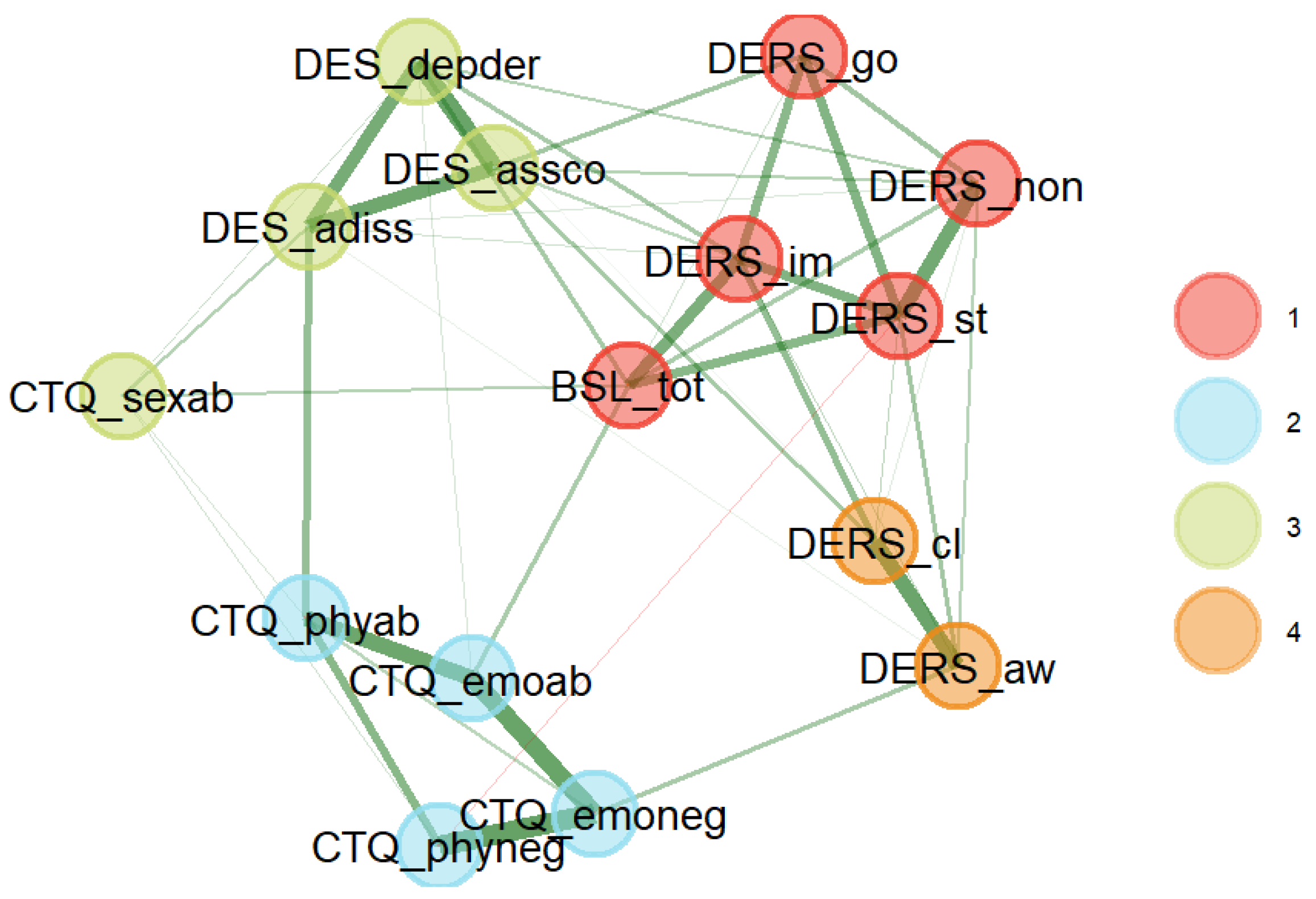

Results of EGA are reported in

Figure 2. The connections between the various nodes are represented by lines of differing thickness. Thicker lines indicate stronger correlations between variables, while thinner or nearly invisible lines represent weaker associations. Variables occupying central positions in the network and showing a high number of connections—so-called "hubs"—may be particularly relevant, as they suggest factors that play a key role in linking different psychopathological nodes. Analyzing the strongest connections and identifying variables that act as bridges between different clusters may provide valuable insights into how various psychopathological domains influence one another.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the nodes are grouped into four distinct clusters, each marked by a different color (red, blue, green, and orange). These clusters suggest the presence of statistically correlated subgroups of variables, which may reflect different psychopathological dimensions or distinct underlying processes.

The green cluster includes variables related to dissociation, such as DES_depder, DES_assco, and DES_adiss, which respectively measure depersonalization and derealization, absorption and imaginative involvement, and dissociative behaviors. These variables are connected by dense and strong links, indicating a high level of correlation among these dissociative phenomena. This result is expected, given that they represent subscales of the same measurement instrument. However, what is particularly noteworthy is the inclusion of the node corresponding to sexual abuse (CTQ_sexab) within the same cluster, highlighting a strong interrelation between dissociative symptomatology and childhood experiences of sexual abuse. This finding further supports Hypothesis 4 of the study.

Borderline symptomatology (BSL_tot) appears to be strongly interconnected with the inability to engage in goal-directed behaviors during emotional distress, the non-acceptance of internal emotional states, and a tendency toward impulsive action—represented by the subscales DERS_go, DERS_non, and DERS_im, respectively. The red cluster specifically emphasizes the centrality of BSL_tot, not only within the red cluster itself but also in relation to other variables, suggesting a possible role of borderline symptoms in linking multiple psychological domains. The centrality of BPD is not surprising, given that the data were collected from a population diagnosed with BPD. Two other subscales of the DERS—namely, clarity (DERS_cl) and impulse (DERS_im)—seem to form a separate cluster (orange cluster), suggesting a unique relationship distinct from the other subscales of the same questionnaire.

The blue cluster, which includes variables such as CTQ_emoneg, CTQ_emoab, and CTQ_phyneg, represents links among various ACE dimensions. This group of variables appears to constitute a separate but meaningful dimension in the network, indicating a strong relationship between early adverse experiences and present manifestations of emotion dysregulation and dissociation. It is worth noting, however, that the variable CTQ_sexab (sexual abuse) shows stronger correlations with dissociative symptomatology than with other childhood adversities measured within the same scale.

Finally, the orange cluster includes awareness of internal emotional states (DERS_aw) and the ability to recognize the nature of emotional responses (DERS_cl) as two distinct dimensions. These two components of emotion dysregulation appear to diverge from the other DERS subscales and from borderline symptomatology (BSL_tot), suggesting a unique pattern within the network structure.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that ACEs profoundly affect individuals' capacity to regulate intense emotions, significantly increasing the risk of developing Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). In particular, emotional abuse and emotional neglect are strongly associated with emotion dysregulation, confirming the crucial role of invalidating environments in the development of borderline symptoms, in line with Linehan’s biosocial theory [

5]. Emotional vulnerability, exacerbated by such contexts, thus emerges as a key factor in the development of dysregulation and relational difficulties typical of BPD. The data support the hypothesis that emotional abuse and emotional neglect have a stronger correlation with emotion dysregulation than other forms of ACEs in individuals with BPD. Specifically, emotional abuse appears to be more strongly associated with emotion dysregulation than other traumatic experiences, likely due to its direct impact on self-perception and self-esteem [

23,

24]. Furthermore, both the severity and the type of ACEs experienced significantly influence emotional difficulties, highlighting the importance of clinical interventions focused on improving emotion regulation.

Additionally, the analyses demonstrated that sexual abuse is a significant predictor of dissociative symptoms, suggesting that dissociation may function as a defense mechanism [

27] or as a form of experiential avoidance [

28,

29] in response to severe interpersonal trauma. These findings further support the theoretical models of Ford and Courtois [

8] and Herman [

10], showing that dissociation acts as a protective mechanism against overwhelming emotions and traumatic memories. Thus, sexual abuse emerges as a central factor in dissociative symptomatology, confirming the original hypothesis and reinforcing the specific and direct link between dissociation and sexual trauma. The SEM analysis strengthens this connection, indicating that dissociation may serve as an adaptive coping strategy in patients with a history of severe interpersonal trauma.

Moreover, the results suggest that emotion dysregulation plays a critical role in the relationship between ACEs and observed symptoms (borderline, dissociative, and post-traumatic), reinforcing the notion that emotion dysregulation constitutes a central node in the symptom network of individuals with BPD. These results emphasize the need for targeted treatments, such as DBT, that address the role of dysregulation across symptomatic domains.

The subsequent Exploratory Graph Analysis allowed for a more exploratory investigation of the interconnections among the various domains under study. Findings highlighted emotion dysregulation as a central node in the symptom network, serving as a bridge between ACEs, dissociation, and borderline symptoms. Although dissociation is prominent in individuals with a history of severe ACEs, it appears to be less central than emotion dysregulation, supporting the view that it may act as a secondary response to severe interpersonal trauma.

Regarding cPTSD, the findings are consistent with those reported by Powers and colleagues [

20], revealing overlap with BPD in the domains of emotion dysregulation and dissociation. However, key differences emerge in self-related symptoms. In cPTSD, emotion dysregulation is chronic and accompanied by persistent emotional numbing and a stable sense of worthlessness or shame. In contrast, BPD is characterized by intense emotional lability, extreme anger, and an unstable and fragmented sense of self [

9,

19]. These distinctions reflect different origins and adaptive mechanisms in response to trauma: cPTSD is typically associated with prolonged traumatic experiences that compromise the development of adaptive regulation strategies, whereas BPD is marked by a more reactive and impulsive functioning style. These findings underline the importance of accurate diagnostic differentiation, which is essential for developing therapeutic interventions that address the specific features of each disorder.

The results underscore the importance of systematically assessing the presence of ACEs in clinical settings, especially in patients with BPD. Particular attention should be paid to emotional and sexual abuse, in order to identify the most relevant domains of vulnerability and inform successful treatment planning. The evidence supporting emotion dysregulation as a central node across all symptom domains suggests that treatments such as DBT, and approaches specifically targeting emotion regulation, may be particularly effective. For patients with severe dissociation, specialized treatments such as DBT-PTSD or the integration of techniques like EMDR [

65] into standard protocols may prove beneficial. In cases of comorbidity between cPTSD and BPD, treatments should jointly address emotion regulation and trauma processing. Furthermore, the diagnostic distinctions between PTSD, cPTSD, and BPD revealed through EGA and SEM analyses can assist clinicians in making more accurate diagnoses and in developing personalized interventions. For example, patients with marked dissociation and avoidance symptoms may benefit more from trauma-focused interventions, whereas those with BPD may require prioritized interventions targeting emotional regulation and relational instability.

Despite the promising results, the study presents several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of findings to broader clinical populations. Moreover, only a portion of the sample met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, limiting the robustness of SEM and EGA analyses in exploring PTSD-specific aspects. Additionally, the PTSD assessment tool was based on DSM-IV criteria, and future research may benefit from using updated measures that also capture the DSO components characteristic of cPTSD. Given that this is a cross-sectional study, caution is warranted in generalizing results and in avoiding any causal inference between ACEs and psychopathological symptoms. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for evaluation of the effectiveness of DBT, which the majority of participants had received. Finally, the retrospective assessment of ACEs may be influenced by memory biases, potentially affecting the reconstruction of traumatic experiences.

Future studies would benefit from adopting a longitudinal methodology to further examine the role of emotion regulation as a mediator in the relationship between ACEs and borderline symptoms. Additionally, it would be valuable to explore individual differences in response to emotion regulation-based therapeutic interventions, in order to develop increasingly personalized and evidence-based treatment strategies. Lastly, further research could investigate the interactions between ACEs and other biological and social risk factors in the etiology of BPD.

5. Conclusions

This study has contributed to clarifying the central role of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in the development of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), highlighting how specific types of ACEs—namely emotional and sexual abuse—are significantly associated with emotion dysregulation and dissociation. The results reinforce the importance of considering ACEs not only as a foundational element in understanding BPD, but also as a critical factor in explaining its symptomatic complexity, which is often associated with comorbidity with PTSD and cPTSD.

The analyses conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA) demonstrated that ACE dimensions exert a diversified impact on emotion dysregulation, borderline symptoms, and dissociative symptoms in a sample of patients with BPD and trauma. This suggests that difficulties in emotion regulation are not merely a consequence of trauma but represent a central component in the psychopathological network of BPD, linking past trauma to the current manifestation of symptoms.

Another important contribution of this study lies in the differentiation among PTSD, cPTSD, and BPD. While these conditions share symptoms such as emotional hyperreactivity and dissociation, they differ in the origin and nature of those symptoms. The findings emphasize that, whereas cPTSD is more directly associated with chronic and repeated trauma, BPD presents with chronic, ego-syntonic emotion dysregulation that is often unrelated to a single traumatic event.

These results have important implications for clinical practice. First, they underscore the need for thorough assessment of ACEs in patients with BPD and related disorders, in order to identify specific etiological factors and to plan targeted therapeutic interventions. Approaches such as DBT-PTSD [

21] appear particularly relevant for this clinical population. Moreover, recognizing the overlaps and distinctions among BPD, PTSD, and cPTSD can help clinicians personalize treatment according to the unique needs of each patient, ultimately improving therapeutic outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C., E.P, E.P., and F.M.; methodology, L.C., E.P.; software, L.C., E.P.; validation, L.C. and E.P.; formal analysis, L.C. and E.P.; investigation, L.C.; data curation, L.C. and E.P..; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; E.P.; E.P.; writing—review and editing, L.C.; E.P.; E.P.; visualization, L.C.; E.P.; E.P., F.M.; supervision, E.P., F.M.; project administration, L.C.; E.P.; funding acquisition, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee) of Scuola di Psicoterapia Cognitiva srl (protocol code 13/25).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Model 1

Appendix A.2. Model 2 with Standardized Estimates of the Free Parameters of Interest

Note.n.s.p > .10. +p ≤ .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

References

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, 2022.

- Lieb, K.; Zanarini, M.C.; Schmahl, C.; Linehan, M.M.; Bohus, M. Borderline Personality Disorder. The Lancet 2004, 364, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.; Scharoba, J.; Noack, R.; Keller, A.; Weidner, K. Subtypes of Borderline Personality Disorder in a Day-Clinic Setting—Clinical and Therapeutic Differences. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment 2023, 14, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, N.R.; Stanton, K. Compatibility of Linehan’s Biosocial Theory and the DSM-5 Alternative Model of Personality Disorders for Borderline Personality Disorder. Personality and Mental Health 2024, 18, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder; The Guilford Press, 1993.

- Niedtfeld, I.; Bohus, M. Understanding the Bio in the Biosocial Theory of BPD: Recent Developments and Implications for Treatment. In The Oxford Handbook of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy; Swales, M.A., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2019; pp. 23–45.

- Grove, J.L.; Crowell, S.E. Invalidating Environments and the Development of Borderline Personality Disorder. In The Oxford Handbook of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy; Swales, M.A., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2019; pp. 47–68.

- Ford, J.D.; Courtois, C.A. Complex PTSD, Affect Dysregulation, and Borderline Personality Disorder. bord personal disord emot dysregul 2014, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Courtois, C.A. Complex PTSD and Borderline Personality Disorder. bord personal disord emot dysregul 2021, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.L. Complex PTSD: A Syndrome in Survivors of Prolonged and Repeated Trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1992, 5, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, L.; Augsburger, M.; Elklit, A.; Søgaard, U.; Simonsen, E. Traumatic Experiences, ICD-11 PTSD, ICD-11 Complex PTSD, and the Overlap with ICD-10 Diagnoses. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2020, 141, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagura, J.; Stein, M.B.; Bolton, J.M.; Cox, B.J.; Grant, B.; Sareen, J. Comorbidity of Borderline Personality Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the US Population. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2010, 44, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, A.; Edens, R.; van Ballegooijen, W.; Dekker, J.; Beekman, A.T.; Thomaes, K. A Network Perspective on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Comorbid Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 2024, 15, 2367815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briere, J.; Rickards, S. Self-Awareness, Affect Regulation, and Relatedness: Differential Sequels of Childhood versus Adult Victimization Experiences. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 2007, 195, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzias, T.; Bohus, M.; Shevlin, M.; Hyland, P.; Bisson, J.I.; Roberts, N.P.; Cloitre, M. Is It Possible to Differentiate ICD-11 Complex PTSD from Symptoms of Borderline Personality Disorder? World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnick, C.; Johnson, D.M.; Yen, S.; Battle, C.L.; Sanislow, C.A.; Skodol, A.E.; Grilo, C.M.; McGlashan, T.H.; Gunderson, J.G.; Bender, D.S.; et al. Clinical Features and Impairment in Women with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), BPD Without PTSD, and Other Personality Disorders with PTSD. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 2003, 191, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunderson, J.G.; Sabo, A.N. The Phenomenological and Conceptual Interface between Borderline Personality Disorder and PTSD. In Personality and Personality Disorders; 2013; pp. 49–57.

- Lewis, K.L.; Grenyer, B.F. Borderline Personality or Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder? An Update on the Controversy. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 2009, 17, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloitre, M.; Garvert, D.W.; Weiss, B.; Carlson, E.B.; Bryant, R.A. Distinguishing PTSD, Complex PTSD, and Borderline Personality Disorder: A Latent Class Analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 2014, 5, 25097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, A.; Petri, J.M.; Sleep, C.; Mekawi, Y.; Lathan, E.C.; Shebuski, K.; Bradley, B.; Fani, N. Distinguishing PTSD, Complex PTSD, and Borderline Personality Disorder Using Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling in a Trauma-Exposed Urban Sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2022, 88, 102558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohus, M.; Kleindienst, N.; Hahn, C.; Müller-Engelmann, M.; Ludäscher, P.; Steil, R.; Fydrich, T.; Kuehner, C.; Resick, P.A.; Stiglmayr, C.; et al. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (DBT-PTSD) Compared With Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) in Complex Presentations of PTSD in Women Survivors of Childhood Abuse: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohus, M. Dialectical-Behavior Therapy for Complex PTSD. In Trauma Sequelae; Maercker, A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2022; ISBN 978-3-662-64057-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafia, J.; Manjula, M. Emotion Dysregulation and Early Trauma in Borderline Personality Disorder: An Exploratory Study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 2020, 42, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases (11th Ed.); WHO: Geneva, 2019.

- Vermetten, E.; Spiegel, D. Trauma and Dissociation: Implications for Borderline Personality Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports 2014, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernberg, O.F. Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism; Aronson: New York, NY, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A.W.; Linehan, M.M. Dissociative Behavior. In Cognitive-Behavior. In Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies for Trauma; Follette, V.M., Ruzek, J.I., Abueg, F.R., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, 1998; pp. 191–225. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchioli, M.; Rugi, C.; Maffei, C. Inability to Withstand Present-Moment Experiences in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clinical Neuropsychiatry 2015, 12, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst, N.; Steil, R.; Priebe, K.; Müller-Engelmann, M.; Biermann, M.; Fydrich, T.; Schmahl, C.; Bohus, M. Treating Adults with a Dual Diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Related to Childhood Abuse: Results from a Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2021, 89, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball; S, J.; Links, and; S, P. Borderline Personality Disorder and Childhood Trauma: Evidence for a Causal Relationship. Current Psychiatry Reports 2009, 11, 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Dell, P.F.; O’Neil, J.A. Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders: DSM-V and Beyond; Routledge, 2006.

- Hooley, J.M.; Wilson-Murphy, M. Adult Attachment to Transitional Objects and Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 2012, 26, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laporte, L.; Paris, J.; Guttman, H.; Russell, J. Psychopathology, Childhood Trauma, and Personality Traits in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Their Sisters. Journal of Personality Disorders 2011, 25, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, H.; Siever, L. An Attachment Perspective on Borderline Personality Disorder: Advances in Gene–Environment Considerations. Current Psychiatry Reports 2010, 12, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijke, A. Dysfunctional Affect Regulation in Borderline Personality Disorder and in Somatoform Disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 2012, 3, 19566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venta, A.; Kenkel-Mikelonis, R.; Sharp, C. A Preliminary Study of the Relation between Trauma Symptoms and Emerging BPD in Adolescent Inpatients. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 2012, 76, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzekwa, M.I.; Dell, P.F.; Links, P.S.; Thabane, L.; Fougere, P. Dissociation in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Detailed Look. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 2009, 10, 346–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalabrini, A.; Cavicchioli, M.; Fossati, A.; Maffei, C. The Extent of Dissociation in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 2017, 18, 522–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglmayr, C.E.; Shapiro, D.A.; Stieglitz, R.D.; Limberger, M.F.; Bohus, M. Experience of Aversive Tension and Dissociation in Female Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder—a Controlled Study. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2001, 35, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglmayr, C.E.; Grathwol, T.; Linehan, M.M.; Ihorst, G.; Fahrenberg, J.; Bohus, M. Aversive Tension in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder: A Computer-based Controlled Field Study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2005, 111, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiglmayr, C.E.; Ebner-Priemer, U.W.; Bretz, J.; Behm, R.; Mohse, M.; Lammers, C.H.; Bohus, M. Dissociative Symptoms Are Positively Related to Stress in Borderline Personality Disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2008, 117, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijenhuis, E.; van der Hart, O.; Steele, K. Trauma-Related Structural Dissociation of the Personality. Activitas Nervosa Superior 2010, 52, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hart, O.; Nijenhuis, E.; Steele, K.; Brown, D. Trauma-Related Dissociation: Conceptual Clarity Lost and Found. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2004, 38, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, S.; Newman, E.; Pelcovitz, D.; Van Der Kolk, B.; Mandel, F.S. Complex PTSD in Victims Exposed to Sexual and Physical Abuse: Results from the DSM-IV Field Trial for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1997, 10, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P. A Developmental, Mentalization-Based Approach to the Understanding and Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. Development and Psychopathology 2009, 21, 355–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.; Palmier-Claus, J.; Branitsky, A.; Mansell, W.; Warwick, H.; Varese, F. Childhood Adversity and Borderline Personality Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2020, 141, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, A.; Cloos, L.; Zdravkovic, M.; Lis, S.; Krause-Utz, A. On the Interplay of Borderline Personality Features, Childhood Trauma Severity, Attachment Types, and Social Support. bord personal disord emot dysregul 2022, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aquino Ferreira, L.F.; Pereira, F.H.Q.; Benevides, A.M.L.N.; Melo, M.C.A. Borderline Personality Disorder and Sexual Abuse: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Research 2018, 262, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgoose, D.; Murphy, D. Associations between Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Complex-PTSD, Moral Injury and Perceived Social Support: A Latent Class Analysis. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 2024, 8, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampling, H.; Kruse, J.; Lampe, A.; Nolte, T.; Hettich, N.; Brähler, E.; Riedl, D. Epistemic Trust and Personality Functioning Mediate the Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Adulthood. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 13, 919191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohus, M.; Dyer, A.S.; Priebe, K.; Krüger, A.; Kleindienst, N.; Schmahl, C.; Niedtfeld, I.; Steil, R. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder after Childhood Sexual Abuse in Patients with and without Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 2013, 82, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raven, J. Raven, J. Raven Progressive Matrices. In Handbook of Nonverbal Assessment; McCallum, R.E., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2003; pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Bohus, M.; Kleindienst, N.; Limberger, M.F.; Stieglitz, R.D.; Domsalla, M.; Chapman, A.L.; Wolf, M. The Short Version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): Development and Initial Data on Psychometric Properties. Psychopathology 2009, 42, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein; P, D.; Stein; A, J.; Newcomb; D, M.; Walker; E.; Pogge; D.; et al. Development and Validation of a Brief Screening Version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect 2003, 27, 169–190. [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, C.; Vieno, A.; Simonelli, A. Italian Validation of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form on a College Group. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2018, 10, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giromini, L.; Ales, F.; de Campora, G.; Zennaro, A.; Pignolo, C. Developing Age and Gender Adjusted Normative Reference Values for the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2017, 39, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein; M, E.; Putnam, and; W, F. Development, Reliability, and Validity of a Dissociation Scale. 1986. [CrossRef]

- Mazzotti, E.; Cirrincione, R. La “Dissociative Experiences Scale”: Esperienze Dissociative in Un Campione Di Studenti Italiani. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia 2001, 28, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, S. Post-Traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS). Occupational Medicine 2008, 58, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; 5th ed.; The Guilford Press, 2023.

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Golino, H.F.; Epskamp, S. Exploratory Graph Analysis: A New Approach for Estimating the Number of Dimensions in Psychological Research. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0174035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, F. Eye Movement Desensitization: A New Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 1989, 20, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).