1. Introduction

This is the 4th in a series of studies on international hospital bed number comparison and capacity planning [

1,

2,

3] which is based on the authors’ 30 years of experience in demand forecasting, capacity planning and financial risk for hospitals and purchasers. To avoid self-citation details of over 300 studies are available in the Supplementary materials S1. These studies will be referenced using an alpha numeric system, i.e., see A.1, etc., in Supplementary material S1, where A, B, etc., refers to a section and 1 ,2, etc., is the study number in each section.

The art of capacity planning is to consider all contingent factors to make a realistic forecast of future bed and staff requirements. If the resulting built capacity is too small the unit is not fit for purpose and may require a second business case and additional construction work – all of which take time and unnecessary cost. On the other hand, if it is built too large there may be a relatively small increase in capital costs, which are depreciated over the life of the building, however, the additional space can be put to other productive uses, say, a small laboratory for point of care testing, etc. The aim of this study is to illustrate how best to make such real-world forecasts.

I entered healthcare in the early 1990’s and was informed that the correct way to forecast future demand was to calculate admission rates by age band and extrapolate these forwards using government statistical agency population estimates for the area in which the hospital was located. It was assumed that government statistical agency forecasts were akin to predictions rather than estimates, and it was ignored that such estimates were often extremely unreliable, especially for children [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Future admissions were then multiplied by future length of stay (LOS) which was assumed to decrease

ad infinitum and the resulting occupied bed days were then adjusted for an optimum bed occupancy rate, often assumed to be 85%.

Over the space of 30 years, I have never come across an age-based forecast that worked in the real world [

1,

2,

3]. Gross underestimation is the most usual outcome because admission rates per age band usually increase over time as medical technology increases the range of treatable conditions, increasing public expectations, social disintegration, and disease incidence/exacerbation rates change, i.e., bronchiolitis, asthma, allergies, cancers, etc., in children [

8,

9,

10]. Relatively common conditions such as appendicitis also show unexpected changes over time [

2], see also S.6 in S1.

In addition, many health conditions show seasonality [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] often exacerbated by meteorological factors which also affect the spread of pathogens [

16,

17,

18]. These imply that the seasonal profile can show high volatility making annual averages an entirely unhelpful planning tool [

19,

20,

21]. For example, it is known that asthma exacerbations in children occur sporadically during the period of autumn, winter and spring [

22]. Another study showed that pediatric trauma admissions are higher during the afternoon, evening, and weekends while rain reduced the admission rate. Each degree of increase in temperature increased the rate of trauma admissions by 4% [

23]. In Taiwan both seasonality and the associations with air pollutants and climate factors vary by age group with the number of weather and pollutant factors increasing with age [

24]. Many common pediatric infectious diseases show a seasonal pattern [

14,

15,

25]. It is worth recalling that staff sickness absence is also seasonal, see E.1-6 in S1, which may conflict with pediatric seasonality.

LOS has been known for many years to be a highly complex variable [

26], see K.1-9 in S1, which is not subject to continuous reduction, and in smaller units is subject to sampling error [

27].

Next, 85% occupancy as an ‘optimum’ has likewise been repeatedly demonstrated to be a complete fallacy [

1,

2,

3]. However, in the literature, 85% has been applied as a crude measure of busyness, where it is true that at above 85% daily occupancy, hospital acquired infections (HAI), staff stress, adherence to standards, medication errors, never events, etc.; become progressively worse [

2,

3,

28]. This is a very different issue to a bed being available for the next arriving patient and is better understood by daily measurement of staff to patient ratios [

3].

The true optimum occupancy in terms of bed availability is dictated by queuing theory which clearly shows that the optimum occupancy is entirely dependent on the size of the unit [

2,

3]. Smaller units are forced to operate at lower levels of average occupancy, and with consequent higher operating costs [

2,

3]. Queuing theory also gives insight into the real number of people waiting for admission (the hidden queue of people on trolleys in corridors, in the emergency department, or in ambulances) and the real time this hidden queue waits for admission. This hidden queue also gives insight into the pressure to prematurely discharge patients or unusually high transfers to other hospital. Sadly, misinformation regarding 85% occupancy has been almost impossible to dispel and queuing theory is almost never used in bed capacity planning.

For all these reasons pediatrics is one of the more challenging specialties regarding capacity planning. While it may be obvious that past trends in births will directly affect pediatric demand, i.e., today’s 10-year-old admissions were born 10 years ago, etc., it may not be obvious that trends in pediatric deaths are likewise important. This association arises from the ‘nearness-to-death’ or ‘time-to-death’ effect [

29] in which 55% of a person’s lifetime hospital bed occupancy occurs in the last year of life, irrespective of the age at death [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], although this becomes 100% for death in the first year of life. Such deaths tend to have an elongated tail regarding LOS thereby having a disproportionate effect on bed demand [

35]. Poisson randomness in the local number of pediatric patients in the last year of life can therefore disproportionately affect occupied bed days, calculated average LOS and costs, see C.16 to C.23 in S1.

Multiple admissions by the same person are reflected in a negative binomial distribution [

36] which has implications to sample size when attempting to benchmark average LOS between different sized pediatric units [

37]. A similar situation is observed in the emergency department where a small number of troubled individuals/parents account for a disproportionate level of attendance, see B.10-11 in S1, and in the average cost for the same HRG/DRG in different sized hospitals, see O.17 in S1.

In addition to the nearness-to-death effect, other pediatric patients have childhood conditions, i.e., bronchiolitis, cancer, etc., which do not lead to childhood death, but which also generate multiple admissions and a negative binomial effect.

The above statistical issues are further compounded by declining fertility and birth rates [

38] which suggest that demand may change with high uncertainty and with location specific trends in births due to internal/external immigration, and local home building [

3].

It has also been observed that many admissions in the first year of life are potentially preventable’ with available community care [

39] but depend greatly on parental factors [

40]. The admission rate per birth in England has been increasing over time and reaches a maximum at 1-3 months after birth, followed closely by 7-28 days, with the minimum admission rate at 0-6 days [

39].

Hence pediatric bed demand is subject to very high seasonal volatility, especially among those in the first year of life [

39] who are acquiring wider immunity and resistance to the external environment and who may be lacking in parental care by mothers with a history of hospital admissions relating to mental health, violence, self-harm or substance misuse [

40,

41].

The concept of volatility also implies financial risk given that hospital income will fluctuate, see N.1-N.40 in S1), and peaks in demand lead to medical errors and litigation costs [

42].

Indeed, poor advice is often given by external ‘experts’ leading to the construction of hospitals or departments which are often far too small to be fit-for-purpose. This has led to the formulation of the nine ‘never make these fatal errors’ in capacity planning.

Attempt to obtain the minimum case possible for all variables by assuming that all schemes to reduce demand will simultaneously achieve 100% success. See point #8.

Use simplistic age-based forecasts for admissions based on a single year. Use more than 8 years of data (preferably 15 years), to follow the trend in each year of age. Then take the trend into the future with multiple probable scenarios along with the observed (past) uncertainty associated with demand.

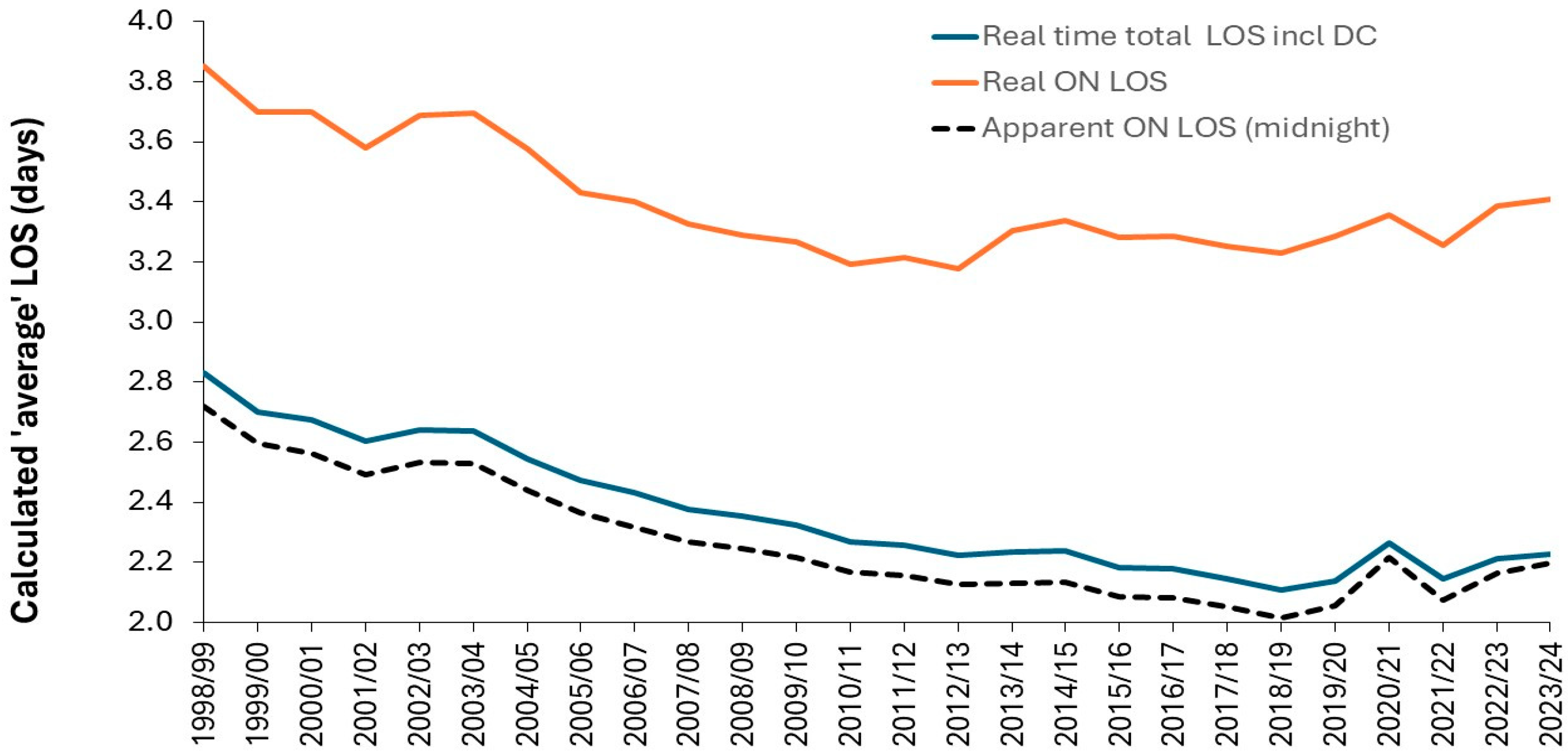

Calculate average length of stay (LOS) based on midnight stays, always use real time data. Midnight LOS will consistently underestimate the real LOS [

3].

Assume that LOS is a constant, rather than a variable with confidence intervals, and assume that LOS decreases ad-infinitum. Most trends in LOS decrease toward an asymptote.

Focus exclusively on those HRG/DRGs which show above average LOS. These will generally be matched by other HRG/DRGs with lower-than-average LOS. These arise due to the ambiguities in the local clinical coding process compared to that applying to the national average. This includes how doctors record diagnoses and the depth of local coding with complications and existing conditions affecting health. Local LOS is subject to sampling error as it is a small subset of national data [

27].

Use annual averages for admissions and LOS. Many conditions show seasonality due to multiple causes and LOS can also show seasonal variation.

Assume that lower LOS means better care or that lower LOS makes large savings in costs. For pediatrics it is the volatility in admissions which dominates bed demand not the calculated LOS – this directly contradicts the accepted dogma that reduction in LOS is one of the key ingredients to reducing bed demand. Reducing LOS only benefits a steady state system or the baseline bed demand which lies beneath the volatile changes, see I.6,9 in S1.

Assume that 85% occupancy is a proven figure. Proof of 85% as an optimum occupancy does not exist and most categorically does not apply to small bed pools such as pediatrics [

1,

2,

3].

Make simplistic models comprising all the variables and proposed schemes to reduce admissions and LOS. An alternative is to use Monte Carlo simulation (including seasonality) which will show the full range of probable outcomes. This is a subset of operational research [

19,

20,

21]. The alternative is to use past data to illustrate the sources of variability – upon which Monte Carlo simulation will be based but without the full nuances of the real world. Hence simultaneous variation in admissions and LOS imply that the actual trend in occupied bed days is a preferred approach.

The nine fatal errors have been regularly observed by the author relating to capacity planning in England [

1,

2,

3]. These were forced on the English NHS in an environment where politicians had an erroneous belief that the NHS had too many beds and a serious policy fiasco where the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) for building hospital capacity necessitated government Treasury rules for the affordability of PFI projects, where the fiscal rules contradicted the real world of how bed demand behaved [

1,

2,

3].

The study is not intended as a comprehensive literature review but gives sufficient wider references to explain why certain approaches are used and will give examples explaining the above fatal errors, propose alternate ways to create capacity scenarios, and demonstrate how the adequacy of current capacity can be quantified.

While data from England is used to illustrate many of the concepts it is recognized that high population density creates a unique situation relative to the USA, see E.6, P.4 in S1, where in 2011 in England some 50% of the population lived within 6 km of the nearest ED and only 9% lived >20 km away. The shortest average distance was only 2.5 km in Camden (London) to the highest average of 34.2 km in Eden (Cumbria) [

43]. The situation in the USA involves far greater distances [

44]. Hence pediatric units in England tend to be larger than in many countries.

The study therefore goes into considerable detail to illustrate the multidimensional complexity behind real-world pediatric capacity planning. This complexity has necessitated placing supporting analysis and discussion in a series of Supplementary files/documents which are part of the peer review process. The supplementary materials also include a special focus on pediatric capacity in the USA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources of Data

International pediatric mortality was from the United Nations [

45], while that in US states was from [

46]. International hospital bed numbers from [

47]. Data relating to England covers financial year inpatient admissions [

48], winter daily SITREPS [

49], hospital bed numbers and occupied beds [

50]. Quarterly bed occupancy in Northern Ireland [

51].

Annual births in world countries [

52], annual births in the USA [

53], births in Arizona [

54] and Hawaii [

55]. Monthly births in European countries from Eurostat [

56]. Annual births in Australian regions [

57].

Monthly deaths by age and sex, England and Wales [

57], single year of age deaths and population, England and Wales [

58]. Length of stay for appendectomy, Australia [

59].

2.2. Additional Data from English Hospitals

Additional data covering hospital admissions, bed occupancy and births for children was obtained by Freedom of Information requests to several English hospitals.

2.3. Analysis of Admissions During the First Year of COVID-19

Statistically significant changes in pediatric hospital admissions [

47] were detected by averaging admissions in 2018/19, 2019/20, 2022/23 and 2023/24, i.e., the 2 pre-COVID-19 years plus the 2 years after COVID-19 had greatly diminished. This average was compared to admissions during the first year of COVID-19 (2020/21) when the Wuhan and antigenically similar Alpha strains predominated, see G.6, G.7 in S1. Differences which exceeded the 95% CI were flagged as significant.

2.4. Analysis of Daily Occupied beds to Simuate a Worst Year

Daily occupied beds can be calculated in two ways. Firstly, from the admission and discharge dates of each patient and summing the number of patients still admitted at any day/time. This method is used in English hospitals. A second method counts the number of admissions and discharges on each day. The number of occupied beds is calculated as:

Current occupied beds = yesterday’s occupied beds + admissions – discharges

This method commences by counting the occupied beds at the start of the time series. It highlights the fact that occupied beds primarily depend on the disparity between admissions and discharges, which is not primarily driven by length of stay (LOS).

The next step is to line up all the years of data commencing on the same day of the week, i.e., a Sunday. For example, 2019 commences on Tuesday, the nearest Tuesday for 2020 is the 31st December 2019, and the nearest Tuesday for 2021 is the 29th December 2020, through to Tuesday the 2nd January 2024, etc. This step is required to detect any day-of-week changes in bed occupancy and is more important when there is a higher proportion of elective procedures.

Each day in the year is then adjusted to contain the same number of occupied beds as the ‘worst’ year in the time series. For England, the highest recent year occurred in 2023/24 which was 38% higher than 2018/19, and 20% higher than 2019/20, etc. Normally this would involve at least 15 years of data, but this depends on the availability of historic data. This then gives multiple views of the potential bed demand in a worst year for every day of the week throughout the year.

Statistical analysis is then performed for every adjusted day of the year (mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, maximum and upper and lower quartiles). Analysis of standard deviation (STDEV) in one English pediatric unit for each day showed that STDEV was randomly distributed, indicating that the baseline pattern for daily median occupied beds (highest from mid-September to just before Christmas) could be diminished/amplified for periods of time in any year but the duration of amplified periods were longer in a worst year, i.e., worst years probably have a higher frequency of disease outbreaks. This method can be used to estimate the proportion of full-time and on-call staff to minimize staff costs throughout the year, see L.31 in S1.

2.5. Analysis of Periods of Maximum Pediatric Deaths

Monthly data for children’s deaths by gender and single-year-of-age [

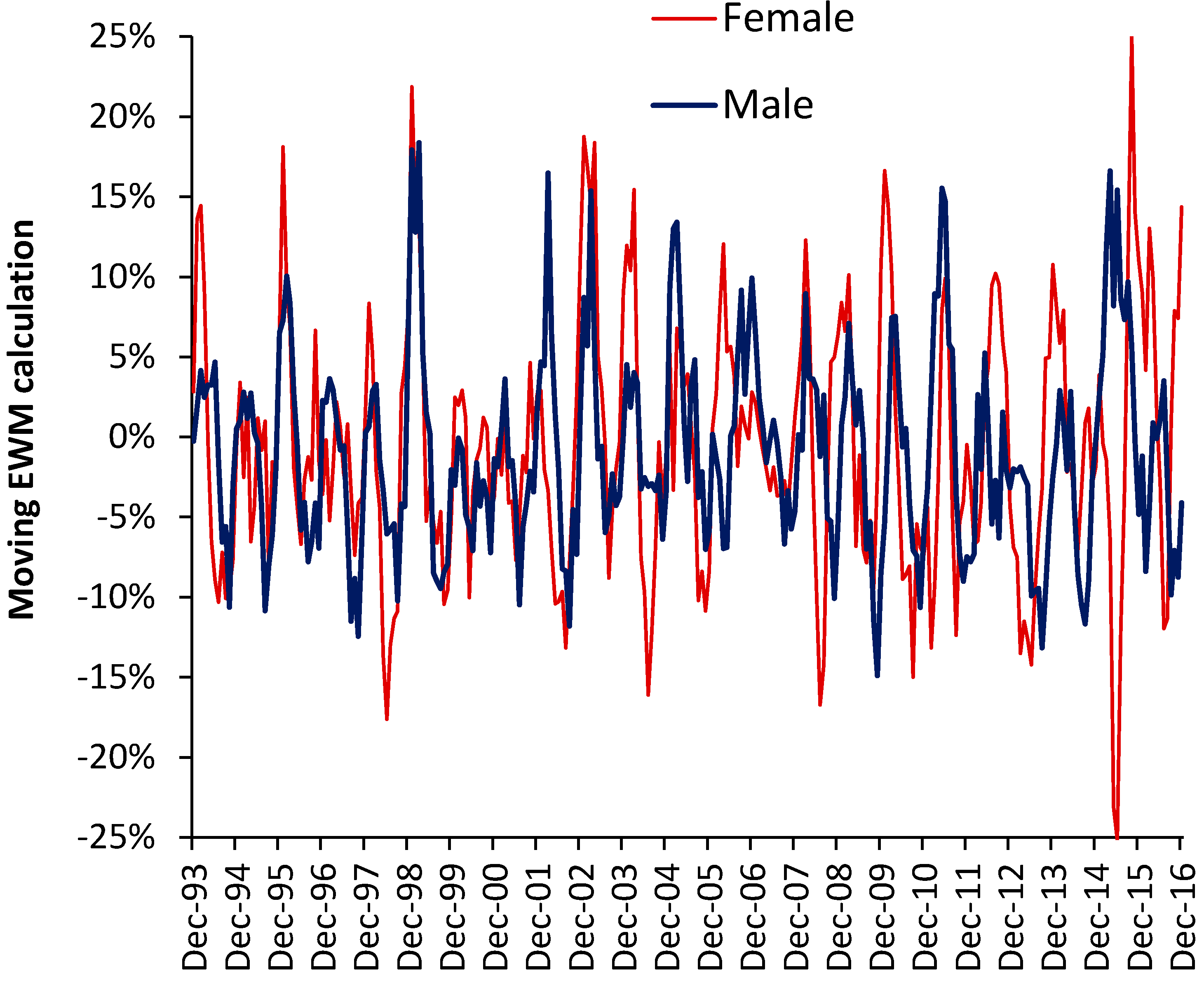

58] was analyzed using a moving ‘excess winter mortality’ (EWM) calculation. An EWM calculation compares the average deaths in the most recent 4 months with the average over the previous 8 months. In the northern hemisphere for adults aged >60 years this calculation usually has its maximum value in the 4 months ending in March, i.e., winter, see H.7 in S1. The concept can be extended to any period of excess mortality by conducting a moving calculation.

Such a moving calculation reveals that while adults show higher winter mortality due to the presence of common winter pathogens such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza, etc., see H.7 in S1, the situation is more complex in children presumably because they are prone to a wider range of pathogens whose various strains/variants have unique year of age profiles, see G.6, G.7 in S1. The 4-month period is sufficient to allow the detection of the spread of multiple types of pathogens across England and Wales. With over 3000 species of known human pathogens the moving EWM calculation is therefore capable of detecting multiple outbreaks.

2.6. Estimating Total Occupied Beds for Children in England

The Hospital Episode Statistics data [

48] used in this study is split by the consultant specialty. Hence, the specialty pediatrics is directly available but total bed use by children must be estimated. Over the years 2000/01 to 2023/24 data is available for the total number of all-age admissions and for children aged 0-14. Data covering 15-19 is only available from 2012/13 onward. For the specialty pediatrics admissions for ages 15-19 were estimated from the trend in the ratio of age 15-19 versus 0-14 from 2012/13 onward extrapolated back in time. This then gives an estimate for the total admissions aged 0-19 across all the years.

Total all-age occupied beds are available for all years and so the ratio of admissions for children was calculated for each consultant specialty and this was then applied to the total number of occupied bed days (occupied beds = occupied bed days ÷ 365 days per year). Unsurprisingly this ratio varies from less than 0.1% for palliative care, around 10% for radiology and trauma and orthopedics, around 40% for audiological medicine and clinical genetics through to close to 100% for the dental specialties. This assumes that the average LOS for children in each specialty is close to that for adults. LOS largely depends on the procedure/condition rather than age; however, slight overestimation is possible. Rather than attempt to extrapolate the proportion of children back in time for every specialty, only extrapolation from 2012/13 to 2010/11 was attempted. It was felt that the reduction in LOS in the specialties other than pediatrics between 2000/01 to 2010/11 was likely to lead to greater over estimation in the earlier years.

3. Results

3.1. Defining Pediatric Admissions, Beds and Bed Pool Size

Definitions and Multi-Specialty Pediatric Care

Pediatric care is defined as any care given to children including general and specialist pediatric care. A bed is defined as any bed/cot/trolley/couch used to accommodate pediatric inpatients or those queuing to gain entry to the department. Such beds can be open (staffed) or closed, i.e., undergoing deep cleaning or held in reserve for times of peak demand. Inpatient care covers both overnight and same day care and can include pediatric assessment units and any wards or critical care units which are dedicated to children.

In England, there were around 1.6 million pediatric admissions (emergency + elective + day case, aged 0-14) in 2000/01 rising to 2.1 million in 2016/17 and then falling to 1.9 million in 2023/24 [

48]. Children can be under the care of consultants from a variety of specialties. In England over 65 consultant specialties treat pediatric patients and

Table 1 shows those where >50% of admissions are for children.

A consultant can have more than 1 registered specialty. Hence the largest number of children’s admissions mainly occur in the specialties Pediatrics (69%), Ear, Nose & Throat (34%), General Surgery (5%) and Trauma & Orthopedics (10%) all making up 82% of the total. Some 1% of admissions occur in the emergency department/assessment units. In England, specialty code 180 is used for admissions into the ‘emergency department’, however, most of these admissions occur in dedicated adult or pediatric assessment units, hence, pediatric assessment units fall within the scope of the study and their size should be determined using the same principles. Some admissions such as cardiothoracic surgery (0.2% of children’s admissions) will occur in specialist hospitals including dedicated children’s hospitals. In England, many dedicated children’s hospitals are located on the site of a larger adult and children’s acute hospital. The specific context will determine how the calculations are applied. The number of required pediatric beds are assumed to include any escalation beds which are open or staffed at peak demand.

When attempting to quantify genuine pediatric bed demand, strictly speaking past data should be adjusted to include any patients queuing to gain entry to the unit such as in ambulances outside the emergency/assessment department, in cubicles/trolleys outside the unit, etc. This implies that peak years may be underestimated.

Finally, regarding specialist children’s hospitals, many of the admissions for the 65 consultant specialties treating children, such as trauma and orthopedics, endocrinology, etc., will occur in dedicated specialty bed pools (as also in adult care). The bed demand in each of these specialty bed pools needs to be forecast separately.

3.1.2. Defining a bed pool

The costs incurred in any health care system are a product of that system. The hospital average bed occupancy is fundamental to understanding those costs [

2,

3]. When researching pediatric unit size in the USA I quickly discovered that what at first appeared to be large children’s hospitals were the product of many years of mergers and acquisitions, hence, a collection of smaller hospitals which may not exclusively focus on pediatric care. Some could more correctly be described as women’s and children’s, etc. This is not exclusive to the USA and the same has occurred in England, hence, the second article in this series gave average bed occupancy at the individual sites of the larger NHS Trusts [

2].

Hence the need to define a bed pool as the fundamental unit of operational efficiency and costs in what may first appear to be ‘large’ hospitals. A bed pool is a collection of beds dedicated to a set purpose such as adult/child, maternity/other care, male/female, etc. Other types of care are not allowed to cross into the defined bed pool and most importantly the bed pool size must be determined at each site.

The bed pool then becomes the fundamental unit for capacity planning. The planner must therefore understand which patients use the different bed pools. For example, a day surgery or endoscopy unit may treat both children and adults. There is some overlap such that a trauma unit will have a separate pediatric bed pool, however single rooms may allow discretion as to where older children are located. In the case of a genuine fluid boundary the total beds may be used to model the bed demand to gain economy of scale (discussed later). Some discretion is also allowed if patients can be quickly transferred between sites to balance demand among the smaller bed pools. These become intra-organization transfers as opposed to officially recognized inter-organization transfers.

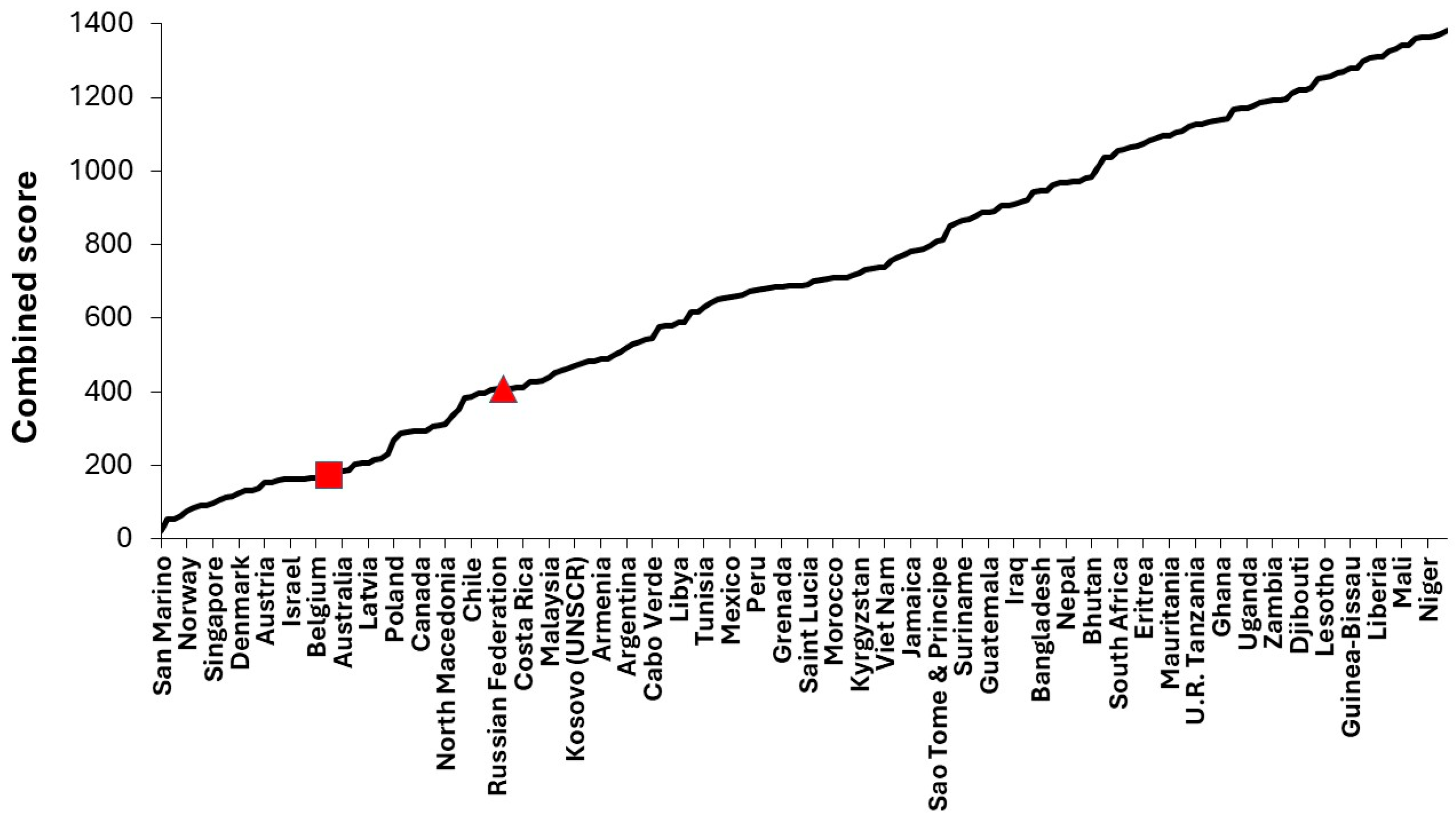

3.2. Ranking Countries by Childhood Mortality

One way to rank the success of pediatric care is to compare childhood mortality. United Nations mortality data [

45] for neonates, infants, age 1-11 months, 1-4, 5-9, 10-14 and 15-19 in 200 countries was averaged over the 3 years 2020 to 2022 and ranked for each group with 1 for lowest and 200 for highest mortality. The individual ranks were then summed across the 7 age groups, and this is shown in

Figure 1. Hence, the minimum score is 7 while the maximum score is 1400.

San Marino had the lowest combined score of 22 rising to 1382 for Somalia. San Marino was generally low across all ages, except age 1-11 months where it ranked 11th. In this study overall comparisons are made between the UK (red square) and USA (red triangle). Wealthy countries other USA all have a low rank score, e.g., Luxembourg (3rd), Singapore (9th), Japan (14th), Switzerland (19th), etc. The nearest countries to the UK are Belgium, Germany, Portugal and Australia, while those nearest to the USA are the Russian Federation, Romania, China and Costa Rica. Across different ages the UK ranked between 9th and 41st while the USA ranked between 51st and 85th. Individual US states are arrayed around this average with Georgia, Mississippi, Indiana, Ohio having about double the rate in New York, Washington, California [

46]. We can assume that net childhood care in the UK is considerably improved than even the best states in the USA in terms of mortality outcomes. How pediatric bed planning may contribute to this disparity will be covered later.

Before progressing further, we need to quantify how well the most recent bed supply across pediatric units is matched against the current bed demand.

3.3. Is Our Current Bed Supply Sufficient?

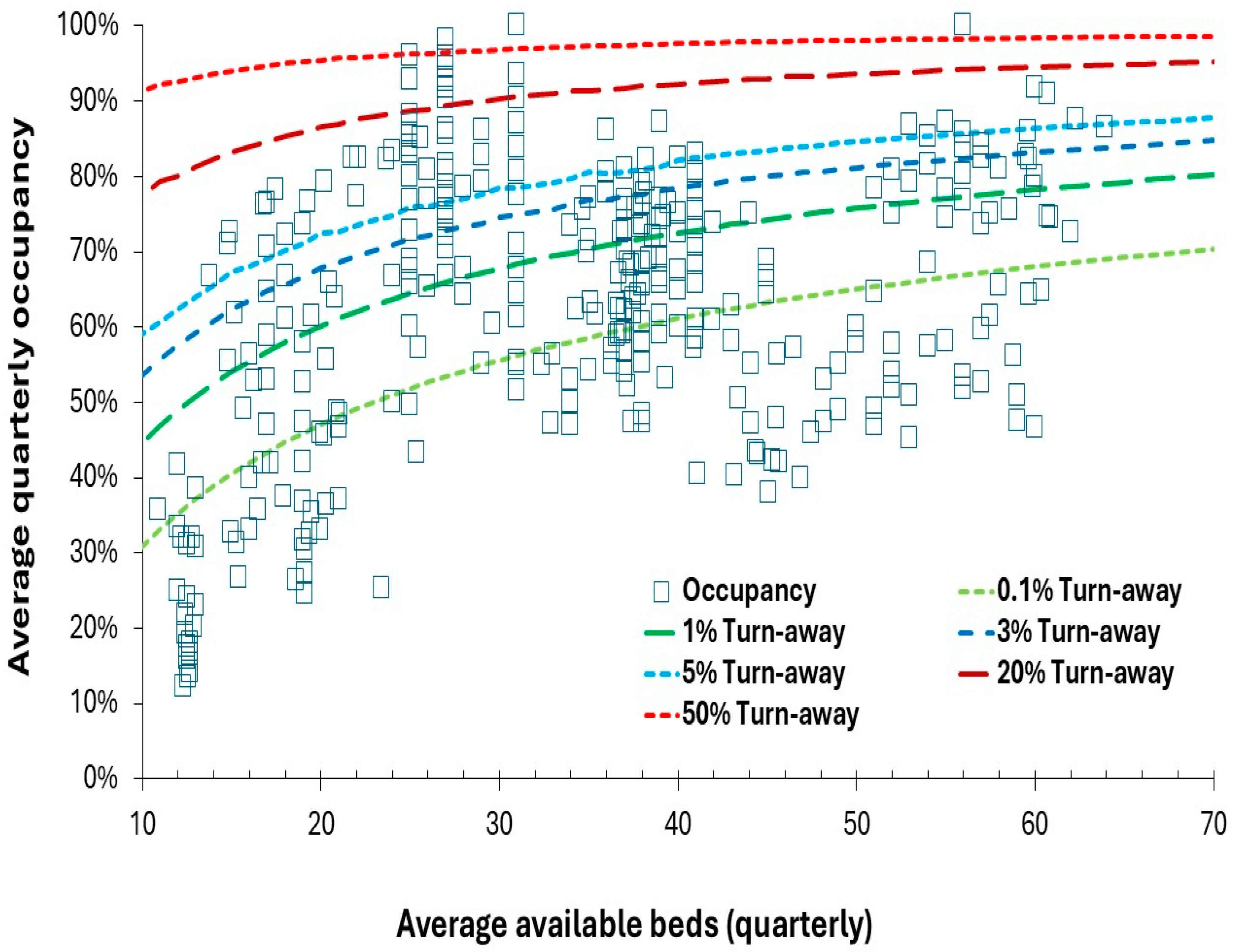

As presented in previous studies [

2,

3] we commence with an evaluation of current bed capacity using the Erlang-B equation and the lines of turn-away. Turn-away measures the proportion of time that a bed is not immediately available for the next patient and is therefore a measure of delays to treatment, hidden queues, cancelled operations, transfers to other hospitals and operational chaos. The aim of the following charts is to allow individual units to compare themselves with all other units of a similar size, and additionally with units having similar levels of turn-away (as a measure of chaos and hidden queues). As was mentioned previously [

2,

3] other forms of the Erlang equations can be used to estimate queue length and the time spent waiting for admission. Clearly bed occupancy varies throughout the day and time of year, and hence long-term averages are used for the purpose of comparing relative performance. In addition, due to the delay between diagnosis and admission for surgery or treatment, units with a higher proportion of elective admissions can operate at slightly higher turn-away. However, recall that the fundamental nature of elective demand is itself subject to Poisson and environmental volatility which imply that the slightly higher occupancy is limited, see D.1-3, 8, 9, N.1, N.2 in S1.

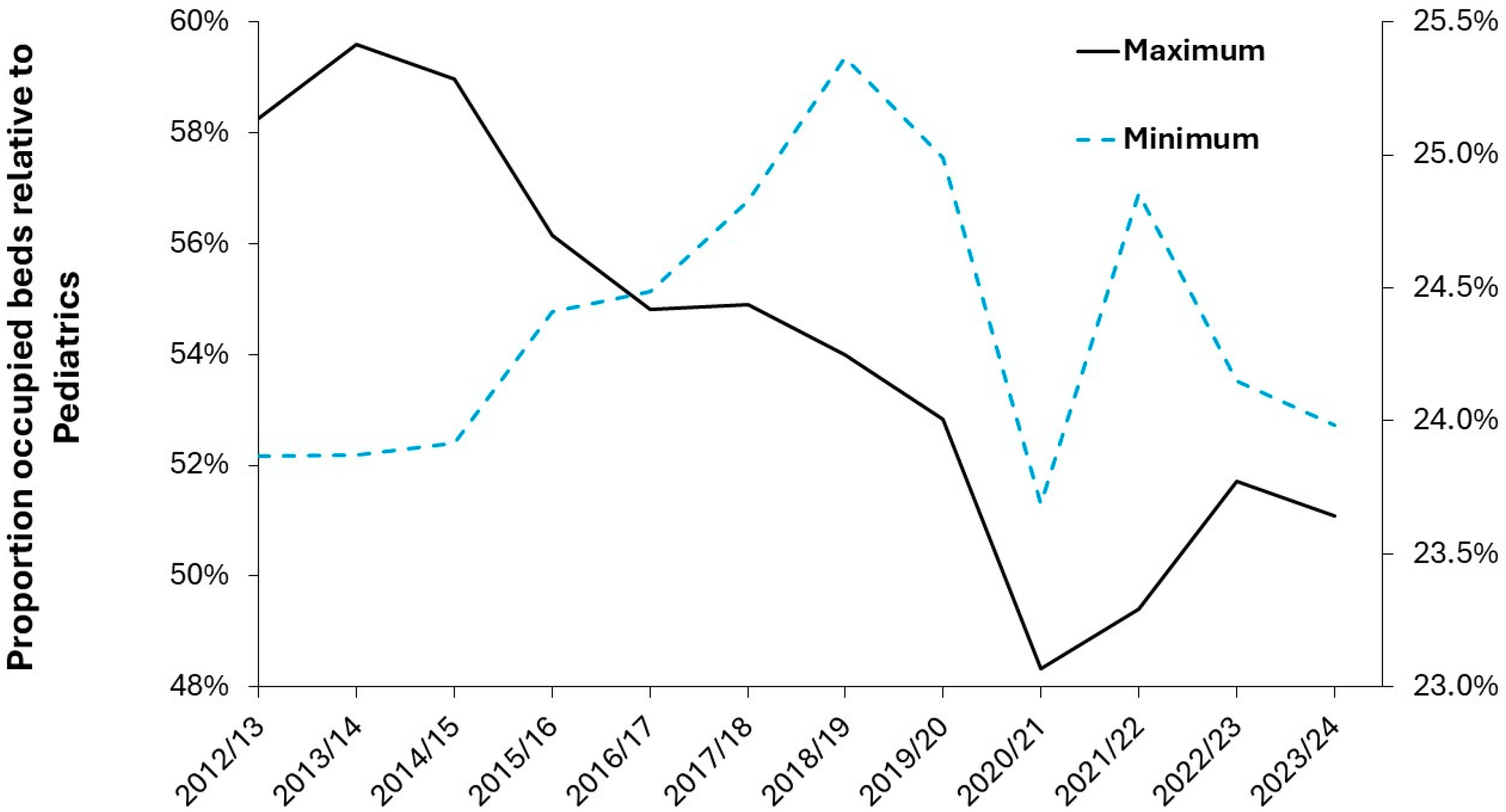

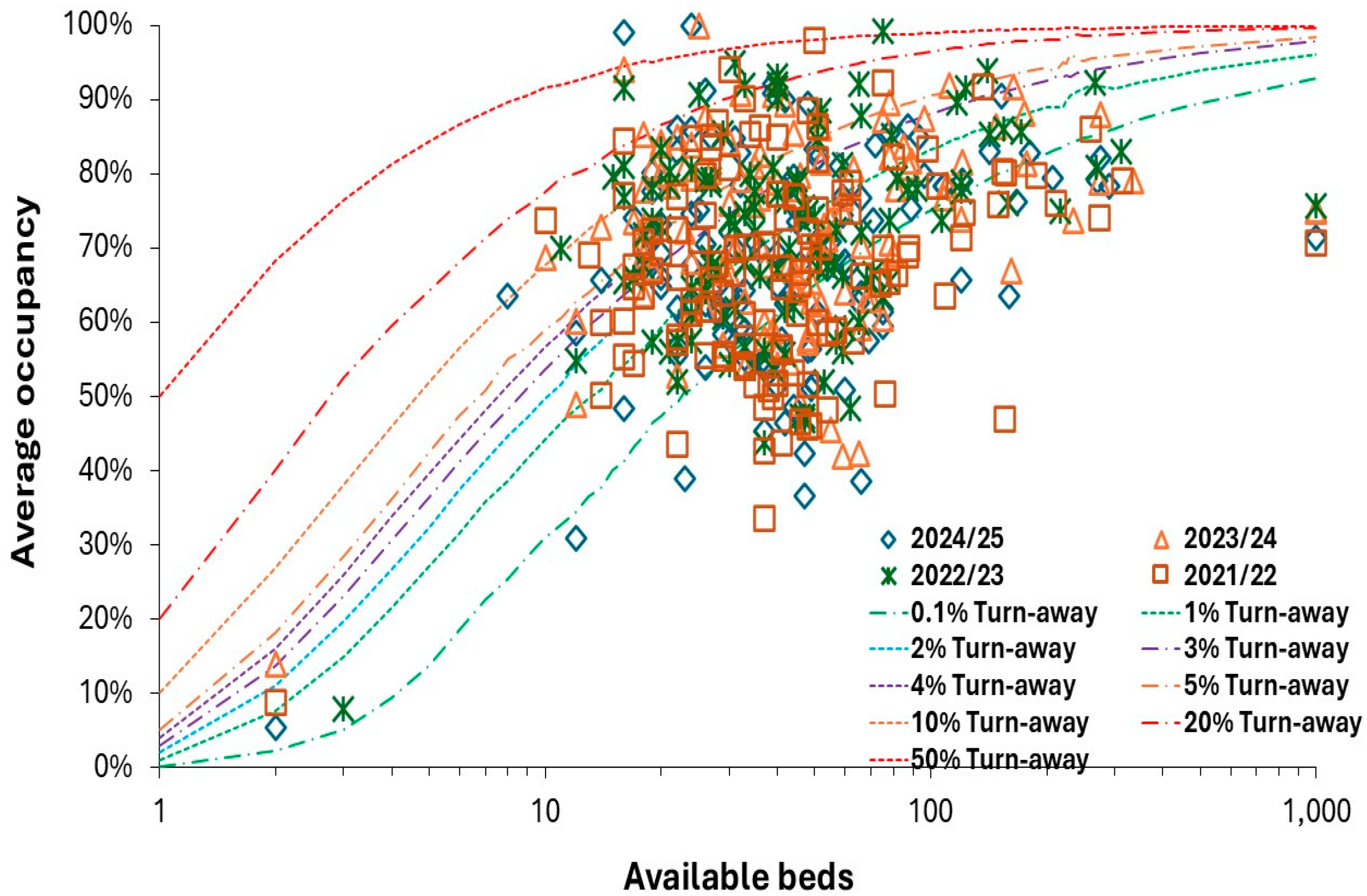

In

Figure 2, data for English pediatric units was obtained from the NHS England winter SITREPS reporting [

49] which documents bed numbers and occupancy at 6 a.m. over the period November to April which approximately covers the period autumn/winter/spring already highlighted to contain seasonal spikes in demand [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

The data gives the maximum number of available beds over the period and the average daily occupancy which will include the dip in bed occupancy during the Christmas and New Year holiday period. The four periods 2021/22 to 2024/25 are covered. Each datapoint represents an NHS Trust which will mostly have just one pediatric unit, but occasionally two or more. At the far right (at 1000 beds) is data for the whole of England, which is around 6000 beds with type 1 emergency departments (ED) and a further 200 beds for hospitals without a type 1 ED. See Supplementary material S2 [

61,

62,

63]. In 2024/25 there were 120 pediatric units in England with the largest being Manchester University (335 beds), Great Ormond Street (273) and Alder Hey Children’s (234). The smallest units are at the Queen Victoria Hospital (2) which is a specialist reconstructive surgery center, while Barnsley hospital (10 maximum, 8 normally) also has a separate children’s assessment unit. For Barnsley, children with specialist needs go to Leeds Teaching Hospital (164), a 40-minute journey, or Sheffield Children’s (162), a 47-minute car journey (both times are outside of peak hours). Data for the lines of turn-away is also available in Supplementary material S2 [

61,

62,

63]. Since units with <10 beds are common for critical care and for pediatric units in other countries more detailed turn-away data is provided up to 15 beds.

It is desirable for any pediatric unit to have somewhere less than an average of 0.1% turn away and about 15% of units achieve this target. About 15% of units operate above 10% turn-away as the average for the whole period. These units have such high turn-away that they are likely to have poor patient outcomes and/or practice high levels of premature discharge. These and the other 70% of units in the middle need to evaluate their future bed requirements. The overall conclusion is that very little has changed in four years and that oversight by NHS England (established in 2012 and abolished on 13 March 2025 to once again become part of the Department of Health and Social Care) and the Care Quality Commission (CQC) has been exceedingly lax – possibly because government agencies are loath to admit that 30 years of a policy-induced capacity planning fiasco led to England being stripped of necessary hospital bed capacity [

1,

2,

3].

By way of comparison, pediatric bed numbers and occupancy are available at quarterly intervals for Northern Ireland (which is run independently of the English NHS) for a 10-year period from 2014/15 to 2023/24 [

51]. These are given in

Figure A1 in the Appendix where we see that pediatric units in Northern Ireland are below the 0.1% turn-away line in around 25% of quarters (mostly during the summer). For units with more than 30 beds, occupancy is generally below the 5% turn-away line in the worst quarters (usually the 3 months ending in December). For units with less than 30 beds the worst quarters lie between 5% and 20% turn-away. The hospitals with up to 100% occupancy deal in child and adolescent psychiatry, where it is well recognized that there are insufficient beds to cope with the volatile demand. It is unknown if the implied wait to admission or implied premature discharge is detrimental to patient care. The smallest pediatric unit with around 11 beds operated at less than 0.1% turn-away in all but 3 quarters but remained under 0.5% turn-away. From the Northern Ireland figures we can tentatively propose that up to 5% turn-away during the worst quarters is a likely limit to an acceptable turn-away and that available (surge) beds can be increased to meet this target.

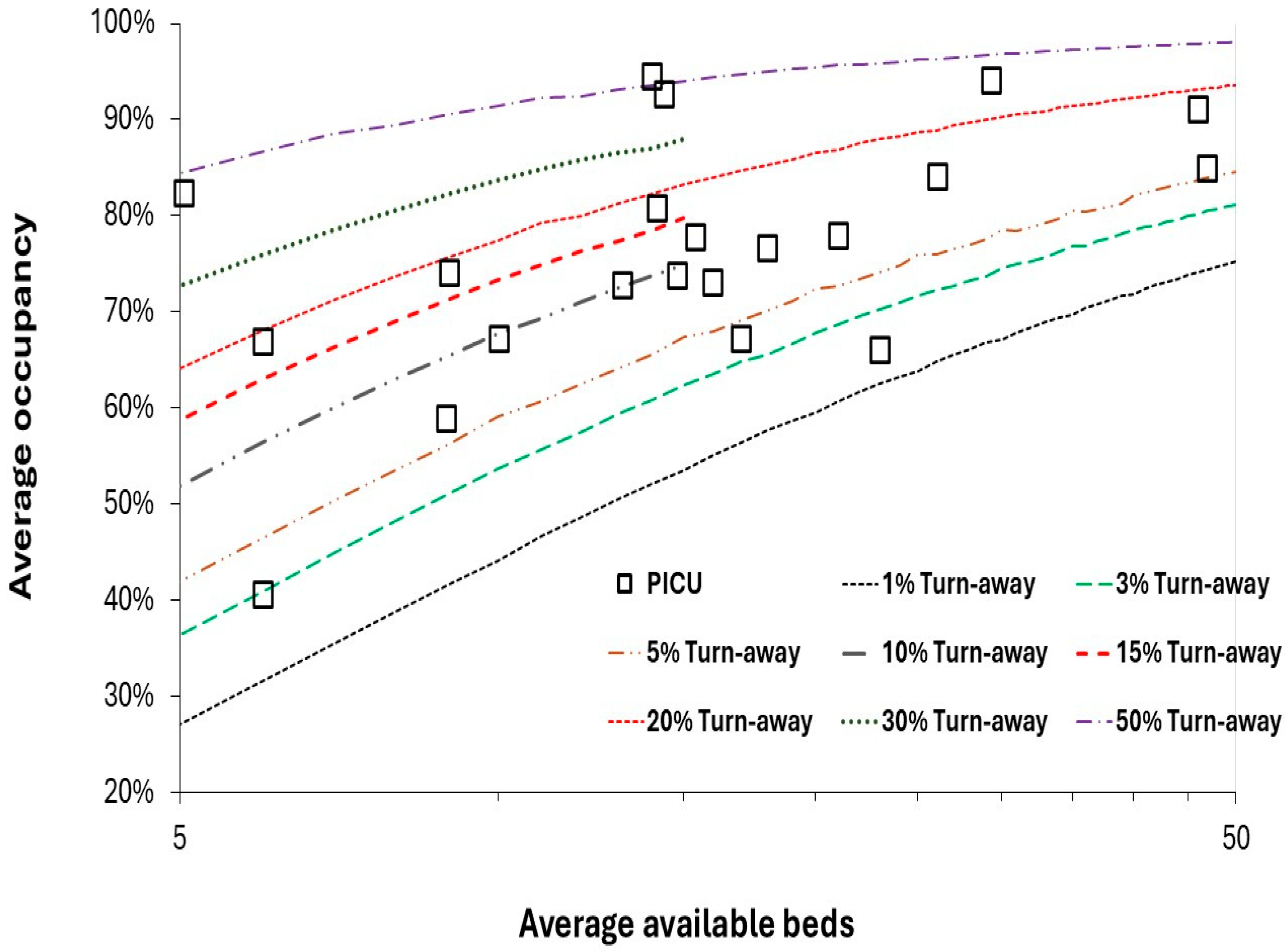

Figure 3 investigates the situation for pediatric intensive care units (PICU) in England during the winter of 2024/25. Pediatric intensive care is generally restricted to the larger teaching hospitals which operate in a hub and spoke manner with the surrounding general pediatric units. The numbers in

Figure 2 are for NHS Trusts and may be spread across more than one site. Were data available for the smaller individual sites the data would be moved to the left and the turn-away would be higher. Up to 10 units look to require additional PICU beds to handle the winter (November to February) peak in demand. The best units look to operate below 5% turn-away.

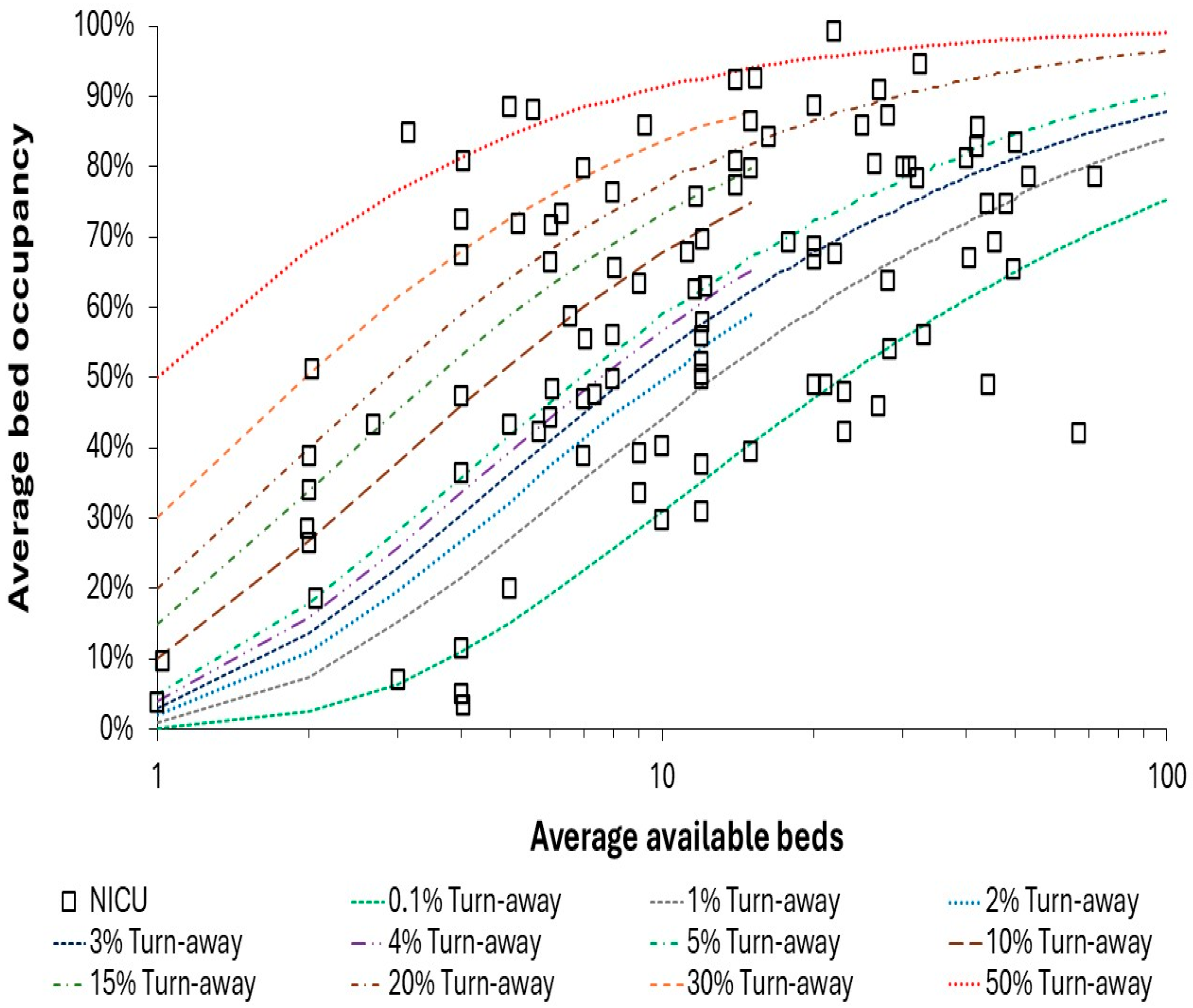

Figure 4 shows the situation for neonatal intensive care units (NICU) for the autumn/winter/spring period in 2024/25. A surprising number of units operate above 20% turn-away, which once again has never been investigated in terms of outcomes.

PICU all function above 2% to 3% turn-away which is consistent with a higher proportion of elective surgical work. However, those units operating above 20% turn-away probably need more beds. NICU is characterized by higher levels of immediate access with around 20 units correctly functioning near to or below the 0.1% turn-away line. Units above the 20% turn-away line almost certainly need more beds. Occupancy and turn-away for these units in the winter of 2023/24 has been previously reported [

3]. For both PICU and NICU several units operate above 85% average occupancy and will therefore experience the combined deleterious effect of high turn-away and high busyness.

From

Figures 2 to 4 it is evident that several units chose to operate with sufficient beds to achieve immediate access, i.e., near or below 0.1% turn-away. Regarding the level of safety for pediatric units, note in

Figure 2 that around 20 units consistently function above 85% average occupancy, also in

Figure 4. Based on the principle of the link between busyness and patient safety [

2,

3], such units should be on the hospital’s risk register and questions should be raised as to why this situation has not been addressed.

An example of using the lines of turn-away to estimate the required surge capacity at a pediatric unit is given in Supplementary material S3 [

49,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68], which uses data from the Barts NHS Trust in England to illustrate the method [

49]. Turn-away offers a suitable method to calculate pediatric surge capacity if around 10-15 years of historic data is available, and adjustment is made for the past and future expected trends in births.

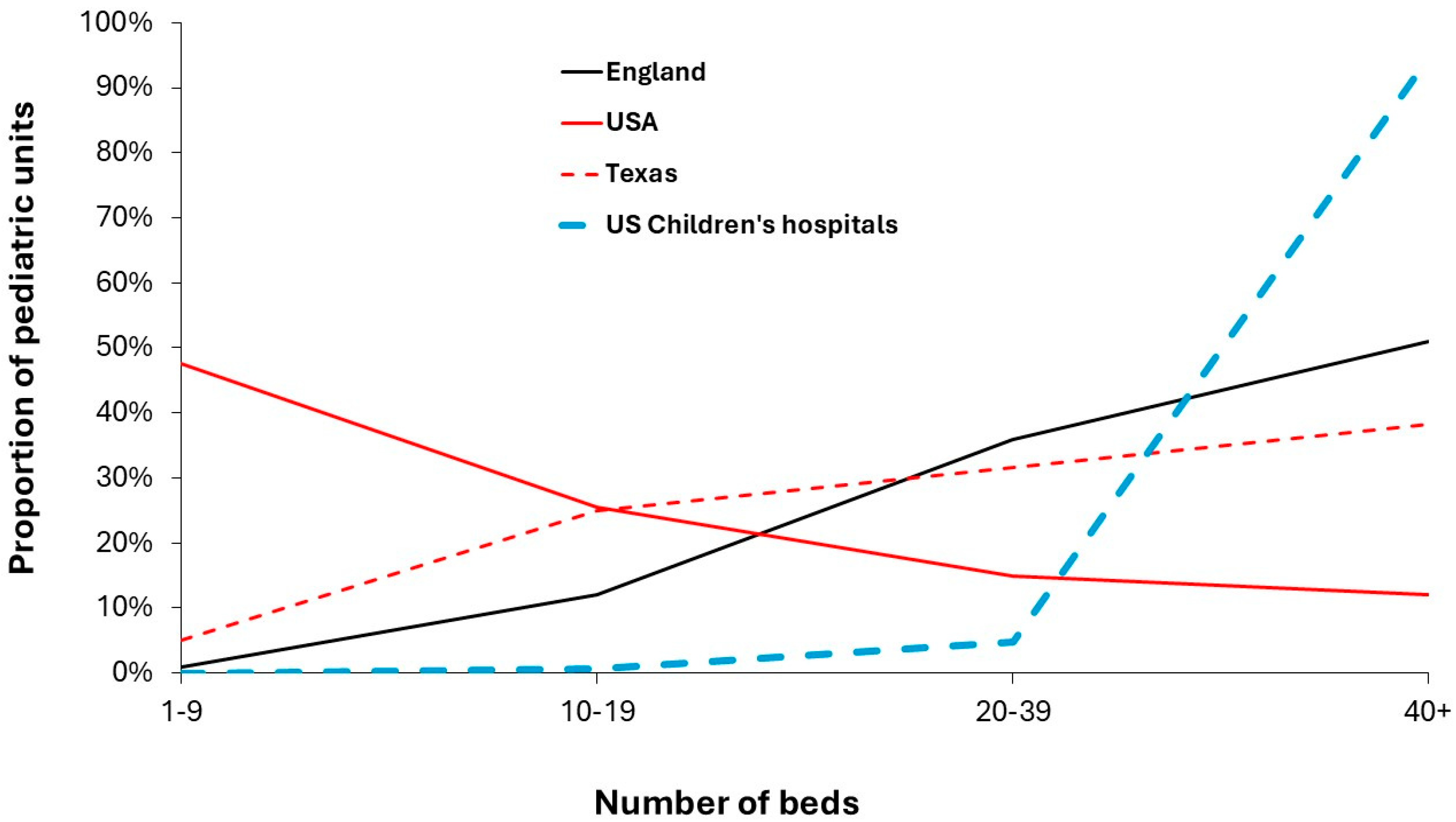

3.4. The Size of Pediatric Units in the USA and England

Since the population density in England is very high, see D.6 and P.4 in S1, pediatric units in other countries are likely to be smaller than 15 beds and a comparison between the USA, Texas and England is provided in

Figure 5 where the USA is characterized by nearly half of units having <10 beds [

60], while England has over half with >40 beds, and Texas is midway, see Supplementary material S2 (61-63). Bed numbers in

Figure 5 need to be understood from

Figure 2 and the intermediate situation for Texas implies even lower than the line for the USA in smaller states. As may be expected, US hospitals which have the term ‘children’s hospital’ in their name largely fall into the 40+ group. For this group the number of beds are the total reported by the hospital. However, this sub-group is counterbalanced by the high proportion of beds in the 1-9 group which will occur in general hospitals (community hospitals in US terminology).

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 should raise potential red flags regarding the ability of the multitude of small units in the USA to function in the face of volatile demand. The study of Cushing et al [

44] further established that 25% of US pediatric units have only 5 beds or fewer. Five beds is a tiny unit with 50% turn-away at 84% average occupancy and 15% average occupancy required for 0.1% turn-away, see Supplementary material S2 [

61,

62,

63].

Regarding the larger US children’s hospitals from Supplementary material S2 we see a median whole hospital bed occupancy around 59% and 65% for size weighted occupancy. Under the assumption that patients can be placed in any bed, i.e., a single specialty hospital, the median occupancy could be 78% and a weighted average of 83%. As explained, [49,50,69–85both are overestimates due to the multi-site nature of many hospitals.

Supplementary document S4 [

49,

50,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85] compares hospital and bed numbers in the USA and England using a ratio per birth to give an approximate like-for-like comparison, while S5 [

61,

62,

63,

74,

75,

77,

82]. applies English bed numbers to show equivalent beds in US states and counties. Spreadsheet S5 is intended to provide a template for other countries to conduct similar comparison and includes a count of maternity units in US states to act as an additional reference point. In S5 using the English norms some 1.5% of the US population lives in a county which would have fewer than 1.5 pediatric beds, 9.8% for fewer than 5.5 beds and 17.1% for below 10.5 beds. Low population density states like Wyoming and Montanna will struggle to provide access for the rural population, and in theory should be given additional help to do so.

The conclusion is that there are at least 2-times more specialist children’s hospitals per birth than England, 2-times more PICU beds and 3-times more NICU beds. However, as of 2022 fewer general pediatric beds than England. Specialist hospital beds show gross inequality in distribution between states and that the beds in some of the smaller units may be better merged – which may not be a welcome suggestion but is qualified by low population density in many parts of the US [

44]. The higher ratios of specialist children’s hospitals, PICU and NICU beds looks to be driven by a higher profit margin rather than genuine patient needs. Alternately, the unlikely situation where children in the USA are 2-times sicker than those in England.

Given this highly skewed distribution of small pediatric units it is unsurprising that pediatric intensive care units (PICU) in the USA are concentrated in cities [

81] where all specialist children’s hospitals are located, see Supplementary material S2 [

61,

62,

63]. A similar situation occurs in England with PICUs only located in a select number of hospitals.

3.5. Using Births to Forecast Pediatric and Neonatal Admissions

Given that both maternity and pediatric services are related by births, Supplementary document S6 [

49,

50] explores the relationship between the respective size of these units in the same hospital or region. In England, a pediatric unit has around 85% of the number of occupied beds as an associated maternity unit, with wider variation in this ratio as the hospital gets smaller or the comparison is made based on quarterly data.

The previous study investigating maternity bed capacity [

3], it was suggested that births in England could rise by up to 24% higher than in 2023 over the next 15 years. An expanded birth forecasting tool has been attached to this study in Supplementary material S7 [

3]. The data in S7 is specific to the UK but can be adapted to other countries. The dilemmas surrounding forecasting future births are addressed in section 3.7. The main point of the forecasting tool is to force the use of single year of age in the understanding of why pediatric demand is so volatile. The issue of single year of age behavior in pediatric deaths will be explored later.

The sheet ‘Forecast admissions’ in S7 [

3] is used to circumvent the key problem that the catchment area of a hospital is not exactly known. However, births, neonatal and pediatric admissions and bed days are known for the unit wishing to forecast future capacity – assuming that the pediatric and maternity units are reasonably close by.

In ‘Forecast admissions’ data has been added for births to the residents of Milton Keynes in England where actual data is available up to 2023. Neonatal and pediatric admissions are merely example data from national ratios. Neonatal admissions assume an approximate ratio of 1 neonatal admission per 7 births (see below). Each unit will substitute their own actual births and admissions data.

Note how the forecast admissions rely on a cascade of ages arising from births. Hence births in 2002 become the population of 1 year-old in 2003, while births in 2011 become the population of 14-year-old in 2025, etc. For the sake of simplicity childhood deaths and inward/outward migration are ignored. The unit will also substitute their best forecast for future births (as alternate scenarios).

The aim of the sheet is to calculate a time series for admissions per birth/population by single year of age over 10 to 15 years to visualize the extent to which the trends in admissions show variation over time. The next step is to attempt to estimate how the admission rate will trend over time. In the example shown in the ‘Forecast admissions’ sheet the maximum admission rate from the past has been chosen to estimate the likely worst-case years in the future. The worst case will not simultaneously happen for all ages. However, the sheet shows that the variable admissions are dominated by the first year of life.

This approach has a major limitation in that its usefulness decreases with the size of the unit and it will therefore give results dominated by Poisson randomness for small units which will include most US pediatric units. In such cases it can be used at State or Area Health Board level to gain insight into the fundamental issues surrounding uncertainty in capacity planning.

A highly recommended alternative is to substitute occupied the larger number of bed days instead of admissions. Since beds numbers are the goal the occupied bed days (average occupied beds = bed days ÷ 365 days per annum) approach is highly recommended. This sheet gives an annual average and an adjustment for seasonality will be required which can be achieved by an analysis of past daily occupied beds which is covered later.

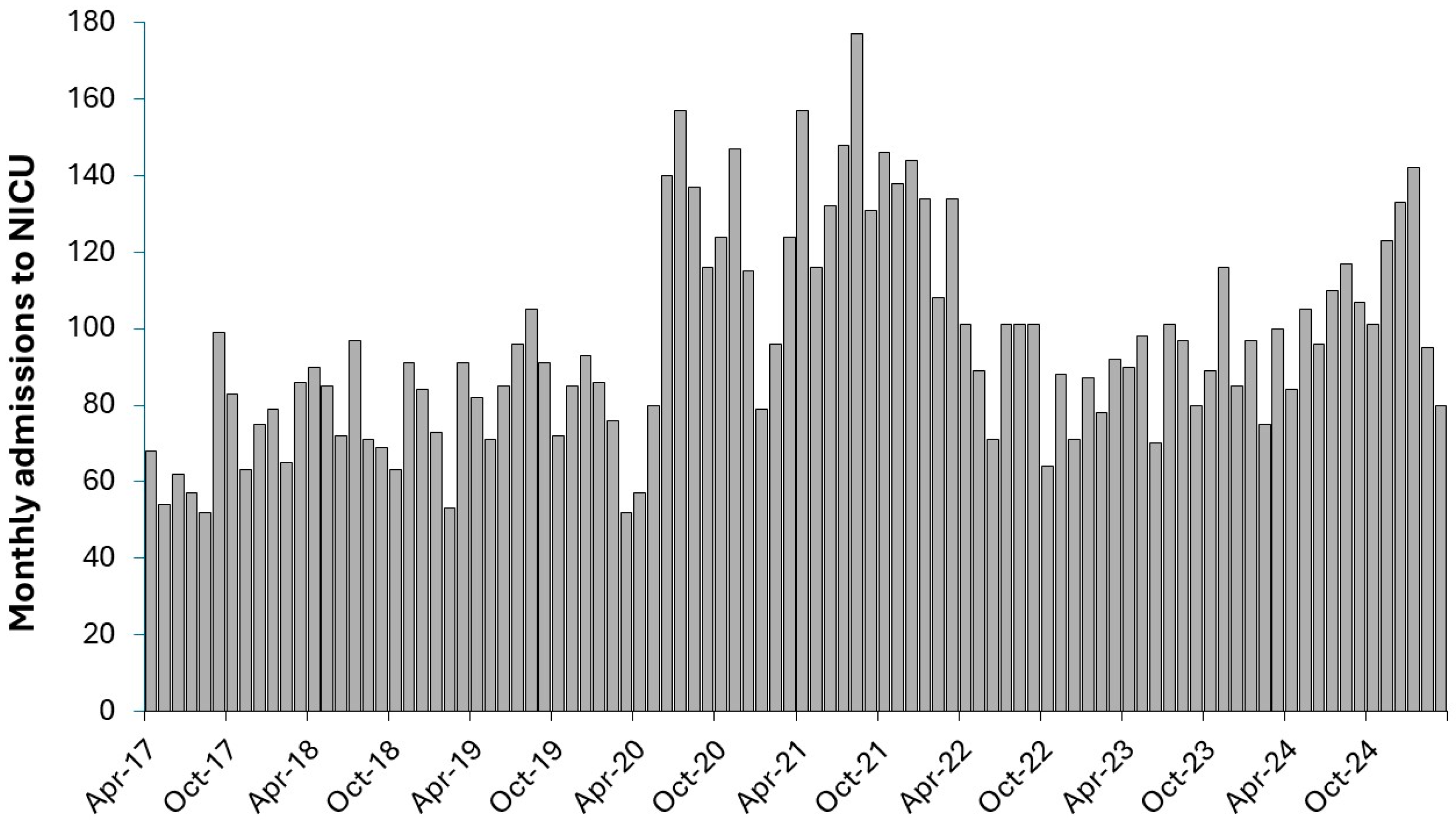

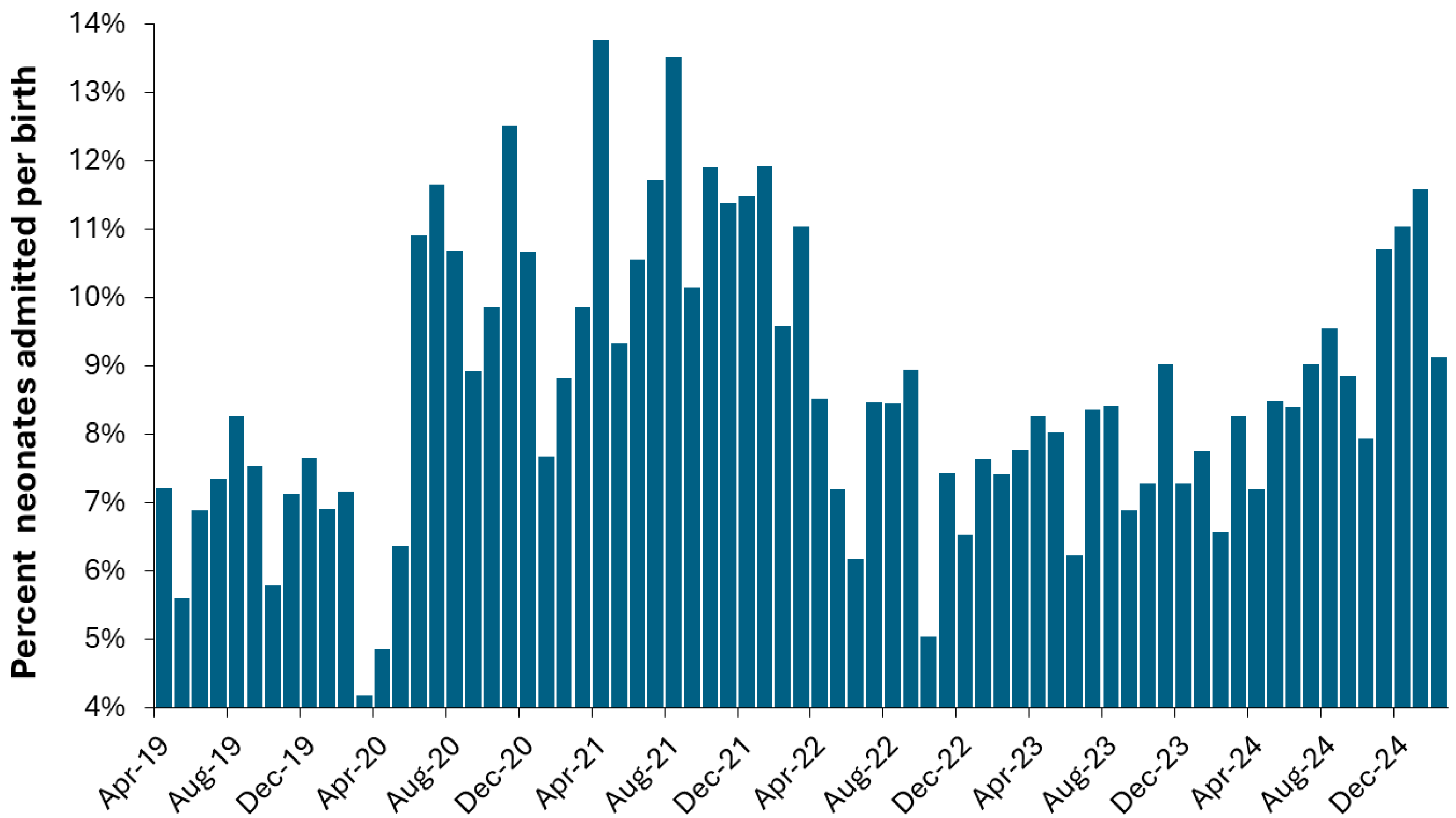

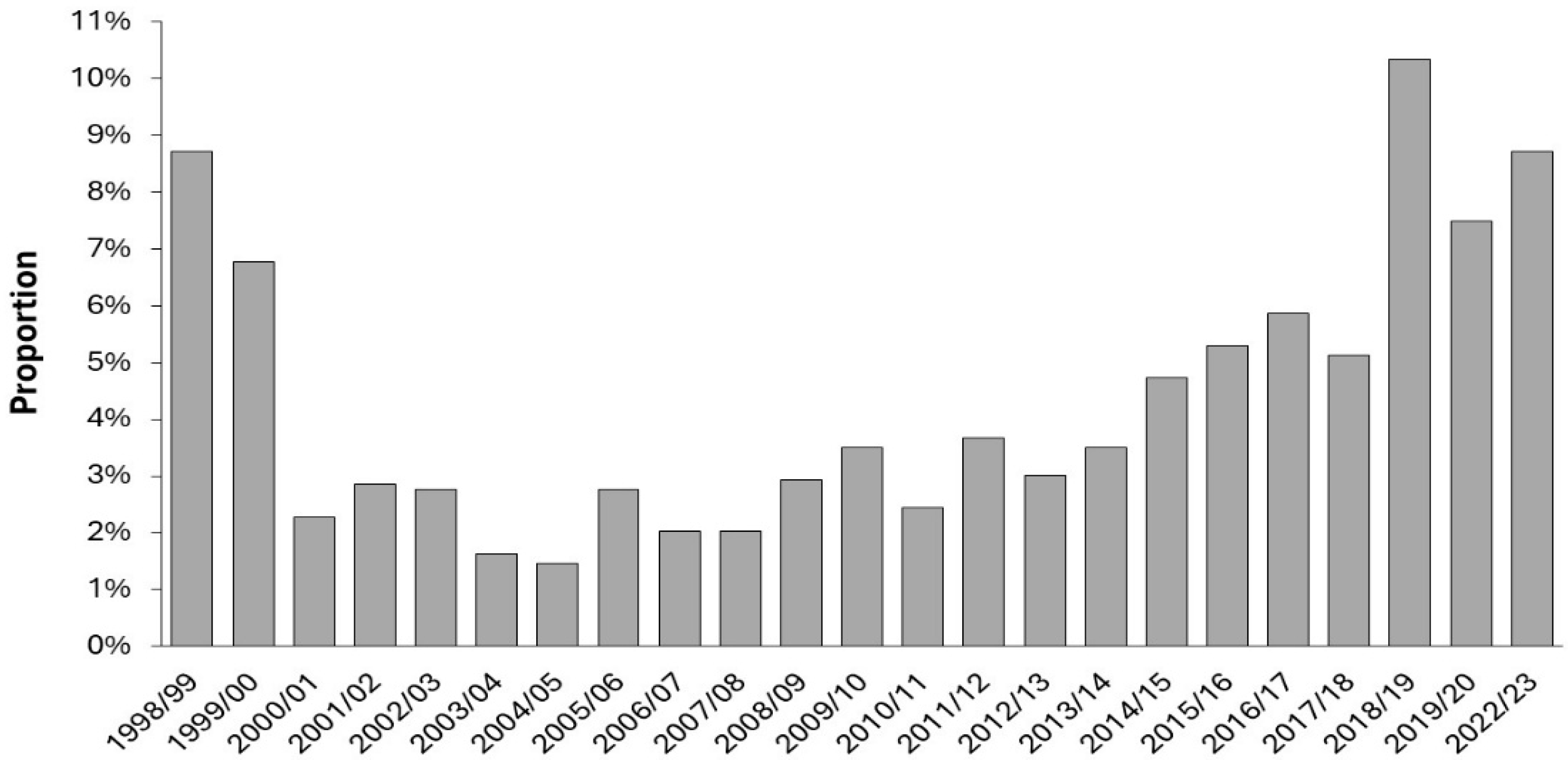

Regarding neonates,

Figure 6 shows that the proportion of births resulting in an admission to the neonatal unit shows systematic variation. Note that the actual monthly admissions shown in

Figure A2 are the combination of births times proportion progressing to NICU. The data in

Figure 6 and A3 comes from the St Bartholomew’s (Barts) group of hospitals in London. While it could be assumed that the first peak is due to COVID-19 it is important to point out that the timing does not exactly coincide, and the data does not reflect the minimum points in the summer for COVID-19 infections. It is not widely appreciated that COVID-19 had a profound effect on the frequencies of pathogens via pathogen interference, see I.3 in S1, and that lockdowns only temporarily altered the transmission of different pathogens. In addition, many neonatal conditions originate during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester, see R.13 in S1. Hence births from April-20 onward will be influenced by events during the preceding 9 months of pregnancy.

Figure 6 also demonstrates that annual averages can be very misleading. Indeed, due to the systematic changes in the ratio of neonatal admissions per birth, a 12-month total will give different answers depending on when the 12-month starts and finishes. This is called the calendar year fallacy, see M.28 in S1.

The previous study [

3] highlighted that births show seasonality which will immediately impact on neonatal demand and on pediatric demand in the first year of life.

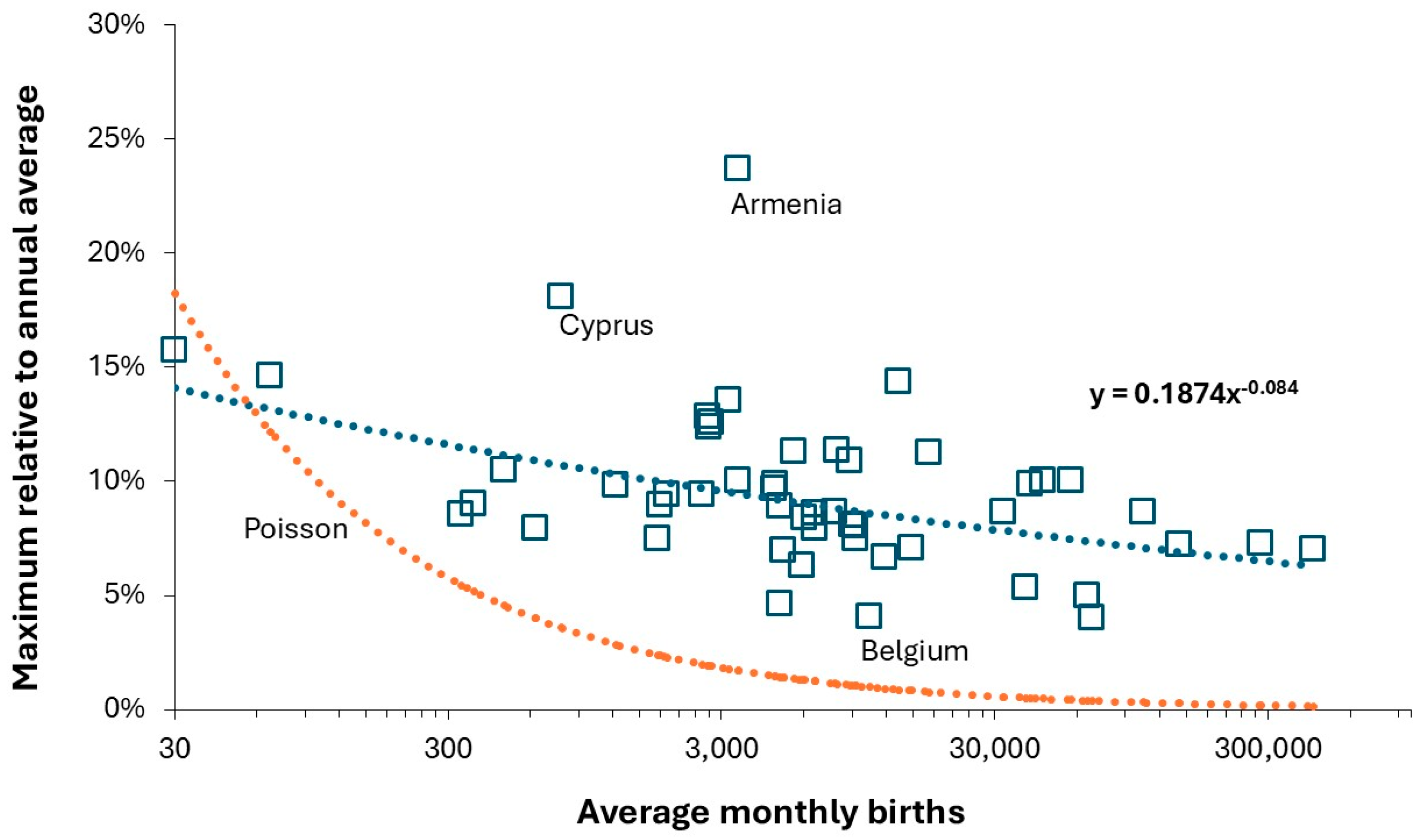

Table A1 in the Appendix demonstrates that all European countries show unique patterns in the seasonality of births and hence each pediatric unit should be aware that the local seasonal pattern will subtly affect bed demand.

Figure A3 in the Appendix demonstrates that systematic factors are involved. The key point is that the local pattern of seasonality in births must be established for each neonatal unit and with knock-on effects in the pediatric unit.

Supplementary material S8 [

56] shows that the shape of the seasonal profile of births is different for every European country. Countries of large geographic size such as Germany and Ukraine can be expected to show region-specific profiles. Lastly, the previous study [

3] demonstrated that the seasonality in births is highly variable around the average value.

Hence the actual admissions to NICU are a complex combination of the (variable) seasonality in births and the (variable) proportion of births progressing to the NICU. This is illustrated later where contrary to the downward trend in births NICU admissions are increasing over time and show periods of high demand. The period of high demand during the first two years of COVID-19 should be investigated to see if the spectrum of diagnoses associated with admission was different to ‘normal’ [

86]. However, note that admissions during the winter of 2024/25 were nearly as high as the two peaks during the first 2 years of COVID-19.

Note that the age in weeks for admission of premature neonates is decreasing over time as technology and medications improve [

87], and that an increasingly higher proportion of births result in a NICU admission where the mother is aged over 30 years [

88]. Also note that very preterm babies have a higher PICU admission rate in the first 2 years of life [

87]. This brings us back to the issue of uncertainty about future demand and the need for spare floor space to cope with future uncertainties.

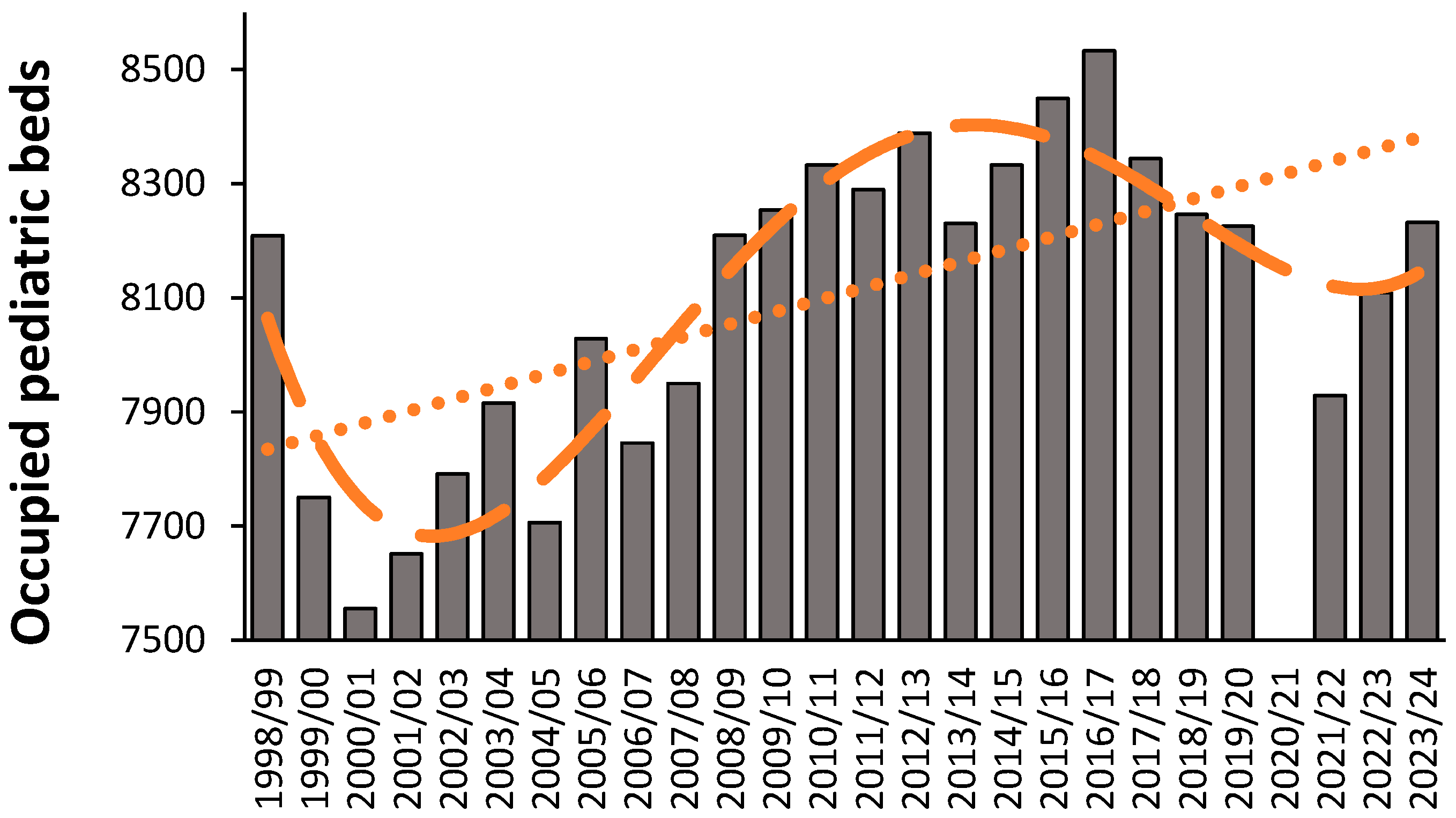

3.6. High Births and Capacity Shocks

Capacity planning in the English NHS has been exceptionally poor over many years [

1,

2,

3] and to this end

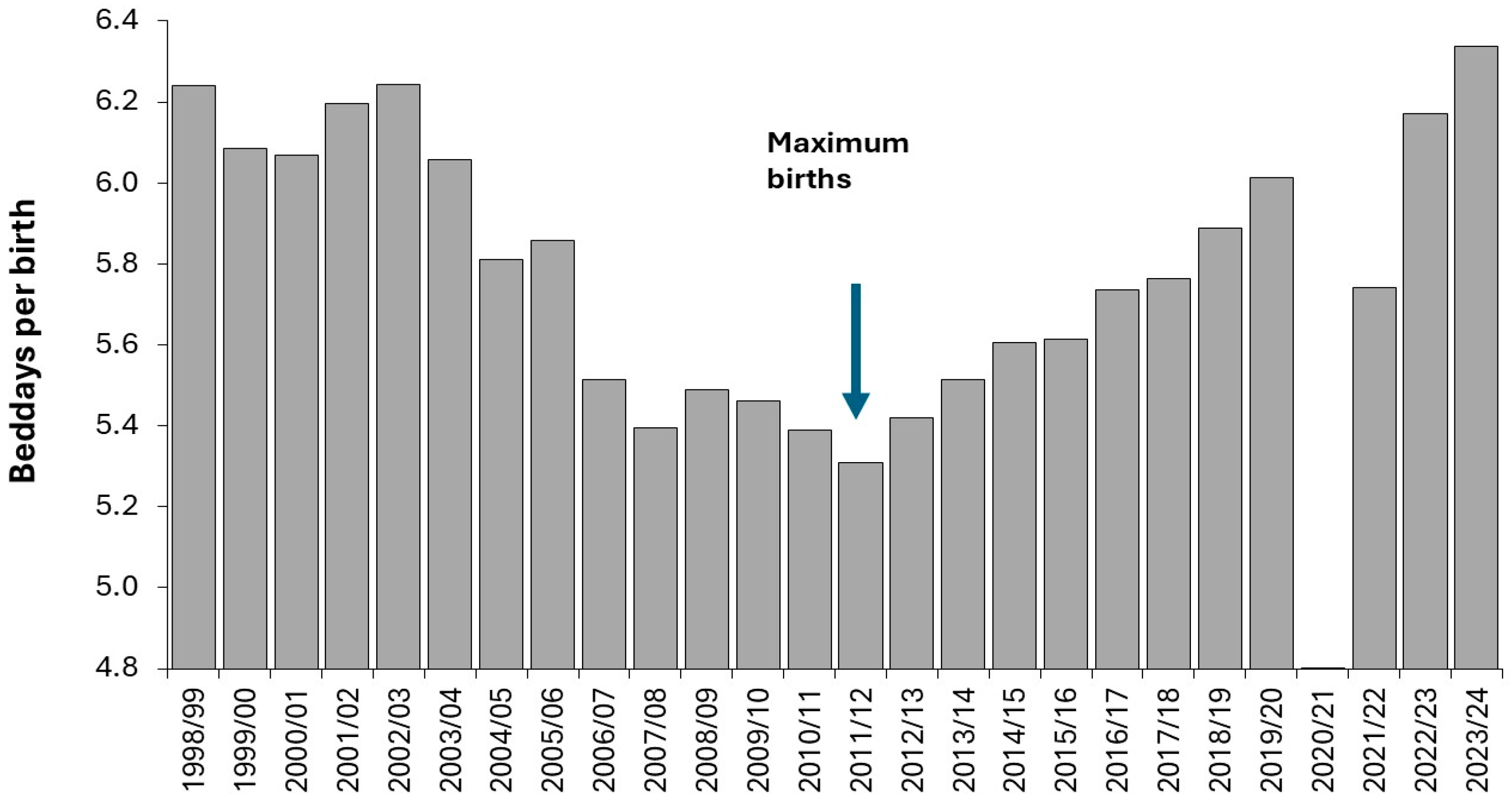

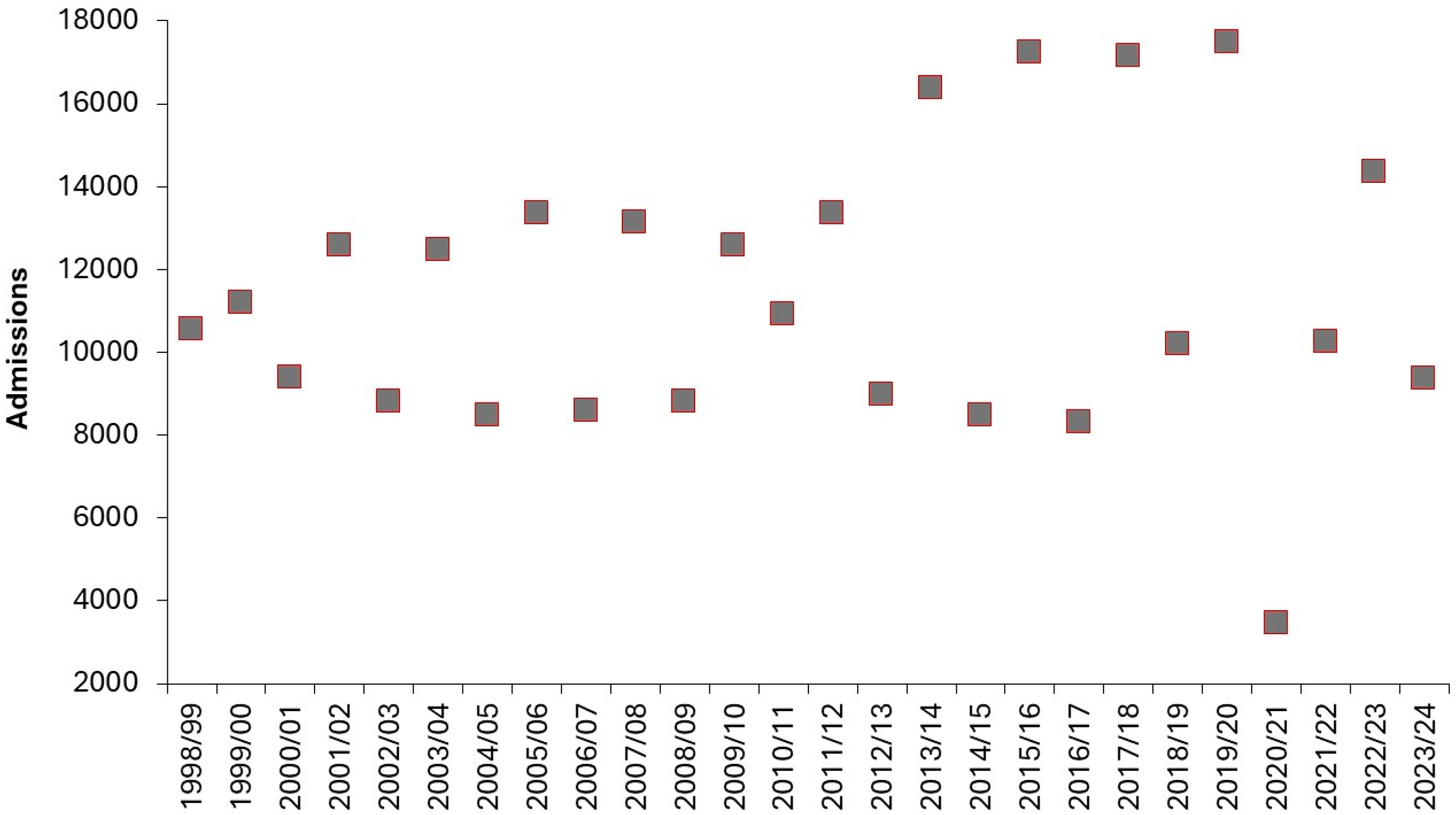

Figure A4 shows the trend in occupied pediatric beds between 1998/99 and 2023/24. Due to the lack of forward planning,

Figure 7 (Based on

Figure A4) shows a self-inflicted capacity shock in 2011/12 when births reached their maximum value as a natural consequence of the World War II baby boom [

3]. Births had previously gone through a minimum in the 12 months ending June 2002 and reach another minimum in 2023.

Figure 7 reflects that there was no expansion in bed capacity after 2002, hence the ratio of total pediatric occupied bed days (all ages) per birth fell as births increased through to 2011/12, i.e., length of stay was squeezed by 15%. As births began to fall after 2011/12 bed days per birth once again expanded. Bed days per birth is not a perfect measure but it illustrates the essential issue.

Since data on pediatric bed numbers has never been regularly collected in England it is not possible to determine the effect on turn-away. Indeed, it would require retrospective analysis to determine the extent to which pediatric outcomes may have declined during this self-inflicted capacity shock. A similar capacity shock occurred in English maternity units [

3]. The situation regarding bed occupancy during COVID-19 is investigated later.

3.7. The Dilemma Regarding Forecasting Future Births

While it is true that the fertility rate is decreasing around the world it is not true that the number of births are decreasing in every country or location. The previous study on maternity capacity planning [

3] devoted considerable attention to the unreliability of birth forecasts and the local factors affecting these trends. To illustrate these concepts

Figure 8 shows the trend in births for the USA between 1950 and 2024 along with a birth forecast through to 2100.

The trend for the USA encompasses the combined effects of past trends in births, immigration, birth control, and fertility rates, and how these have a knock-on effect in the present and future. It was previously noted that England has a similar cyclic pattern to the USA arising from the World War II baby boom [

3]. Supplementary material S9 [

52] shows that every country has its own unique time series for births from 1990 to 2030. Countries are sorted from increasing (mainly in Africa) to decreasing birth trends. Many countries show undulating behavior as seen in the USA and UK, i.e., never assume simple straight-line trends.

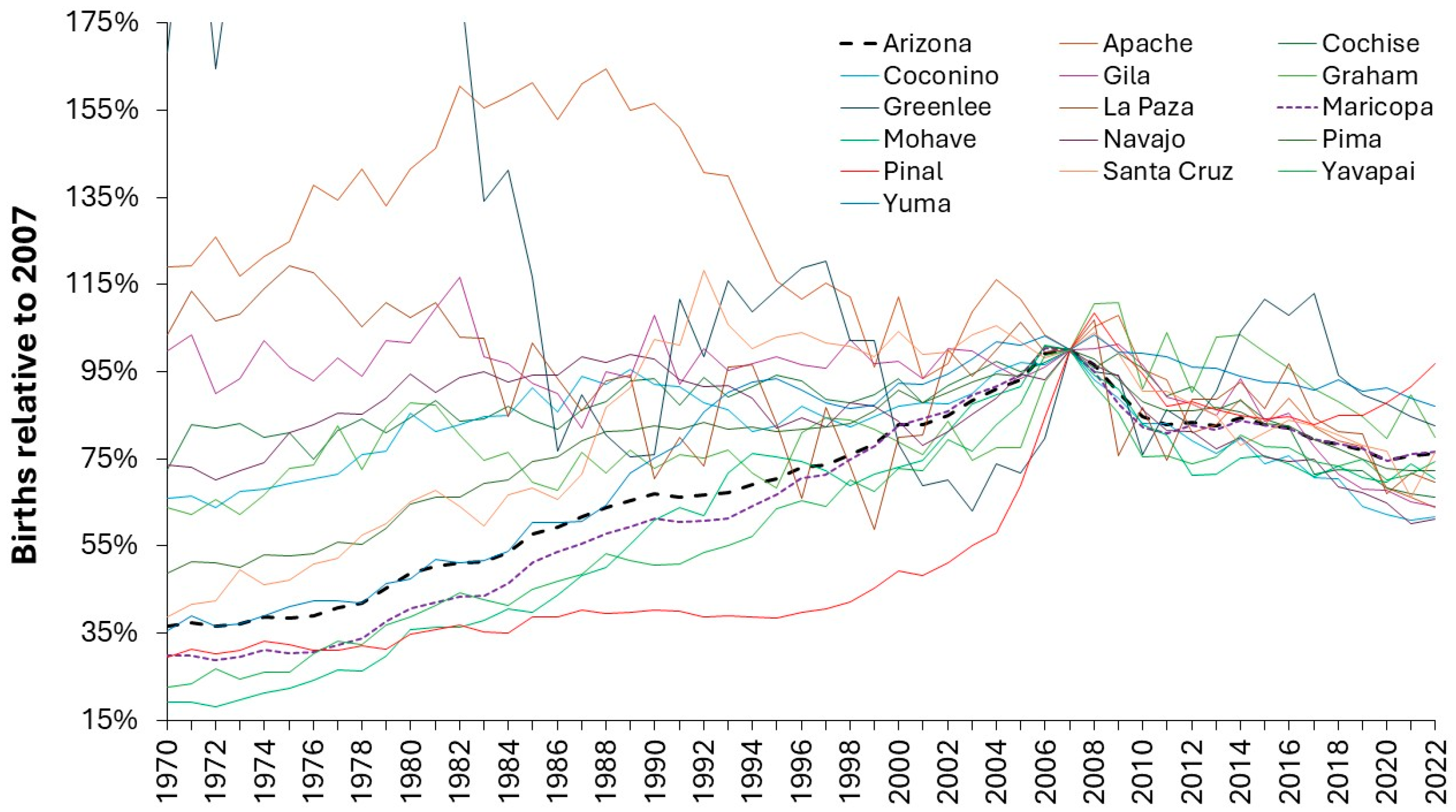

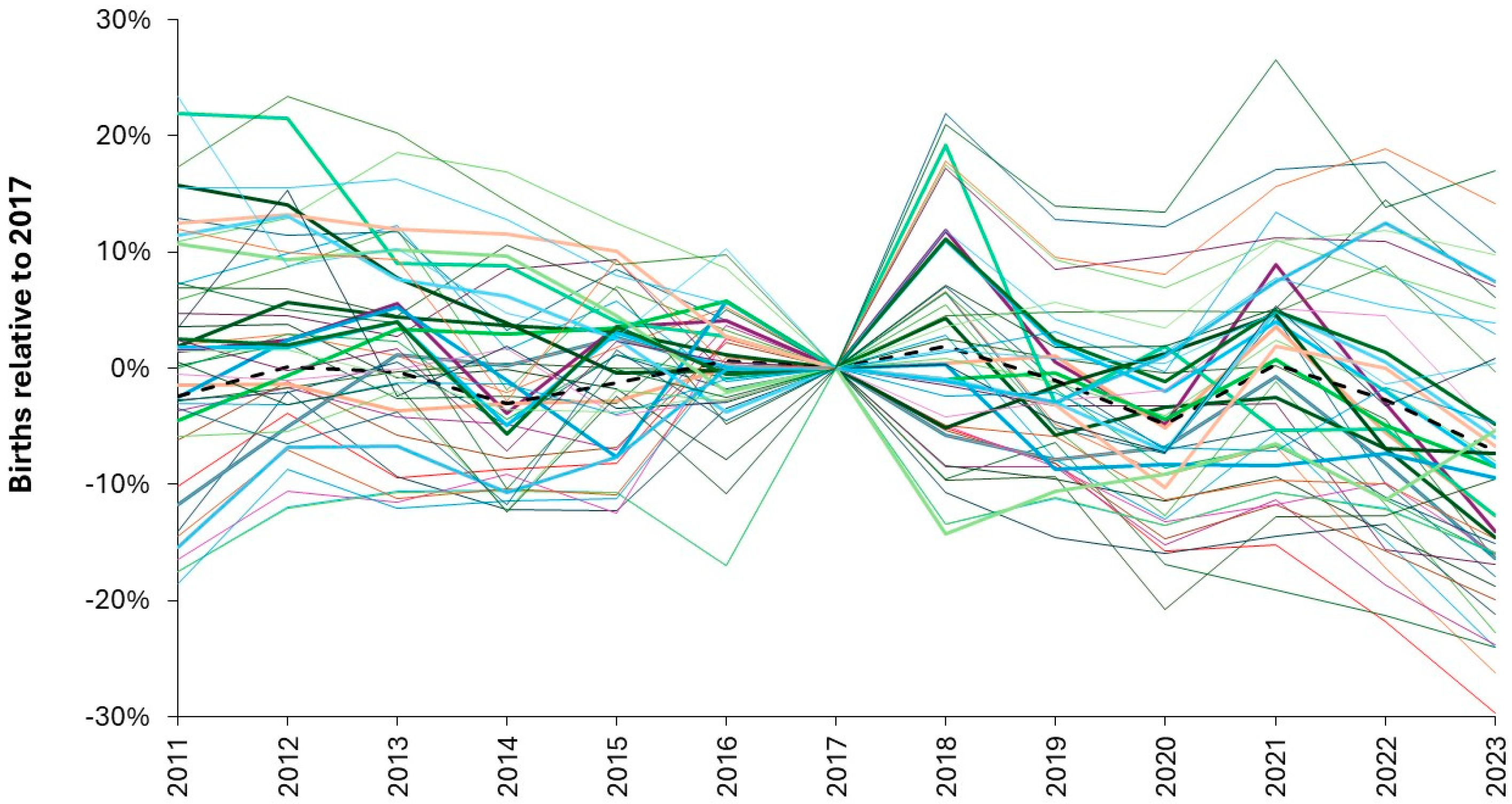

To further illustrate the issue regarding local trends

Figure 9 shows the trend in births from 2011 to 2023 relative to 2017 in selected Australian regions.

Australia has around 300,000 births per annum (black dashed line). Most regions have over 1,000 births per annum but the smallest region, namely South East Tasmania, has less than 400 per annum.

Figure 9 demonstrates the highly regional nature of birth trends and that even at regional level there is considerable volatility between years. Even at the level of Australia there are occasional minimum years as in 2014, 2020, 2023. The minimum in 2020 (-3.7% compared to 2019) is repeated in other countries, despite an almost total lockdown including international travel. However, even for regions with 1000 births the change ranges from -12% to +6% (1 STDEV of Poisson variation is ± 3%). Changes for the other years will have various contributory factors.

Finally, returning to the USA,

Figure A5 [

54] shows the trend in births for counties in Arizona. These trends are nothing like the trend for the USA in

Figure 8 and look to be dominated by population changes especially in Pinal (5127 births in 2022, 31 persons per km2) and Greenlee (114 births, 2 per km2) counties. The importance of local factors cannot be overstated.

Each maternity and pediatric unit sits within a bigger national, regional and local context which must be understood to construct reasonable scenarios for future demand. National and state statistical agencies will have the relevant data and may be able to assist with local birth forecasts under various assumptions.

3.8. Using Past Daily Bed Occupancy to Quantify Seasonality and Staffing

This approach to bed planning has been discussed in detail in N.2 in S1. The hospital information department will use real time admission and discharge data to calculate daily bed occupancy. Some background analysis will be required to determine the time of day when bed occupancy typically reaches its maximum value, and this time will then be used for the historical analysis. It is important that people who have been admitted but not yet discharged should be counted as occupying a bed.

The analysis should be performed using separate elective and emergency admissions. Multiple years of daily occupancy are then lined up starting on the first Sunday of each year. This is necessary to capture the weekday cycle in both emergency and elective admissions. Times of lower bed demand during the summer, Easter, Christmas and New Year holidays will become immediately apparent. Planned bed closures during these times are possible for deep cleaning and to give space for staff holidays.

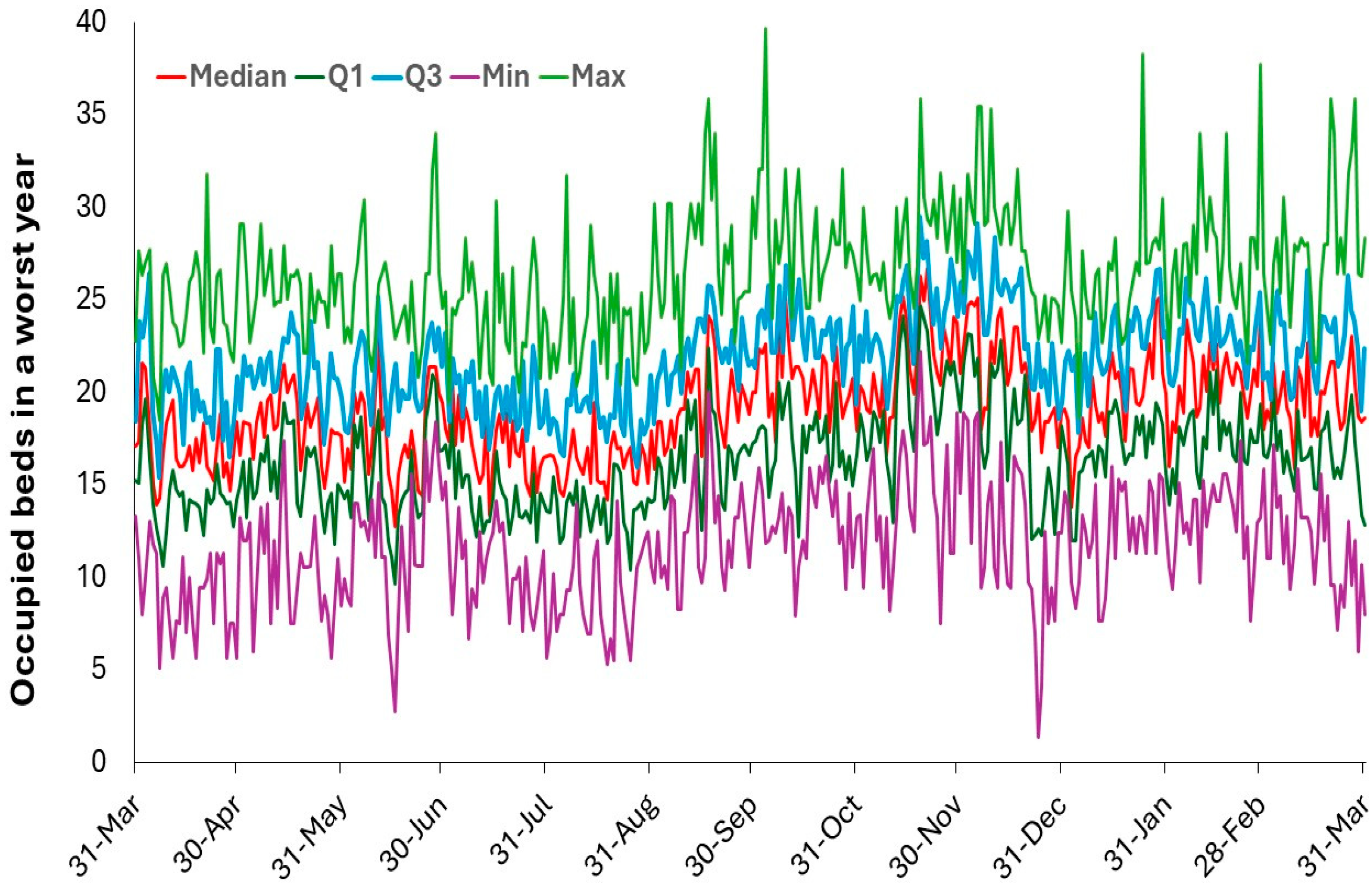

Bed occupancy in each year can be adjusted to give likely future years, either as an ‘average’ year or a ‘maximum’ year (from section 2.4). An example of this is given in

Figure 10 from the Great Western Hospital in Swindon, England.

The reference year was 2023/24, however, as can be seen, a worst year can be made up from segments containing both low and high admissions. This is illustrated in

Table 2 which shows the average beds occupied beds in April and May across all years.

As can be seen 2023/24 (reference ’worst’ year) has the second lowest average occupied beds in April and May, through to 2016/17 which has 45% more than the reference year.

Hence, the timing and magnitude of such small segments are unique to each year. It is of interest to note that each year seems to be divided into 3 larger segments where each segment starts and finishes at the three major school holidays. This is one of the reasons why it is suggested that the transmission of pathogens at school is the major factor regulating pediatric admissions, either by the direct and indirect effects of pathogens via the processes of pathogen interference, see I.3 in S1. This will be covered in the Discussion.

For staffing, perhaps the lower quartile or the median can be chosen to represent the level of full-time staff while variation above the median shows the likely need for ad-hoc staff. This is far easier to achieve in a large city than for a small rural hospital where overtime may be the only recourse. The dilemma is that both the lower quartile and median show considerable volatility, which it is assumed is very difficult to predict. The underlying day of week profile is likewise subject to volatility.

It should be noted that the behavior seen in

Figure 10 is equally applicable to adult medical inpatient care, see L.6 in S1, and is highly suggestive of hidden roles for infectious agents – of which 3000 species of human pathogens have currently been identified, see I.3 in S1. This method is highly recommended because it gives a clear view of the highly volatile real-world bed demand, and it works best when as many years data as possible are available to pick up all possible nuances in intermittent demand surges.

Attempts to predict staffing aside, the overwhelming conclusion is one of extreme complexities and the immense difficulty of resourcing pediatric beds, i.e. staff lurch from very quiet to frantically busy on a regular basis.

3.9. Nearness-to-Death in Pediatric Bed Demand

It is well documented that around half of lifetime hospital admissions and occupied beds occurred in the last year of life [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

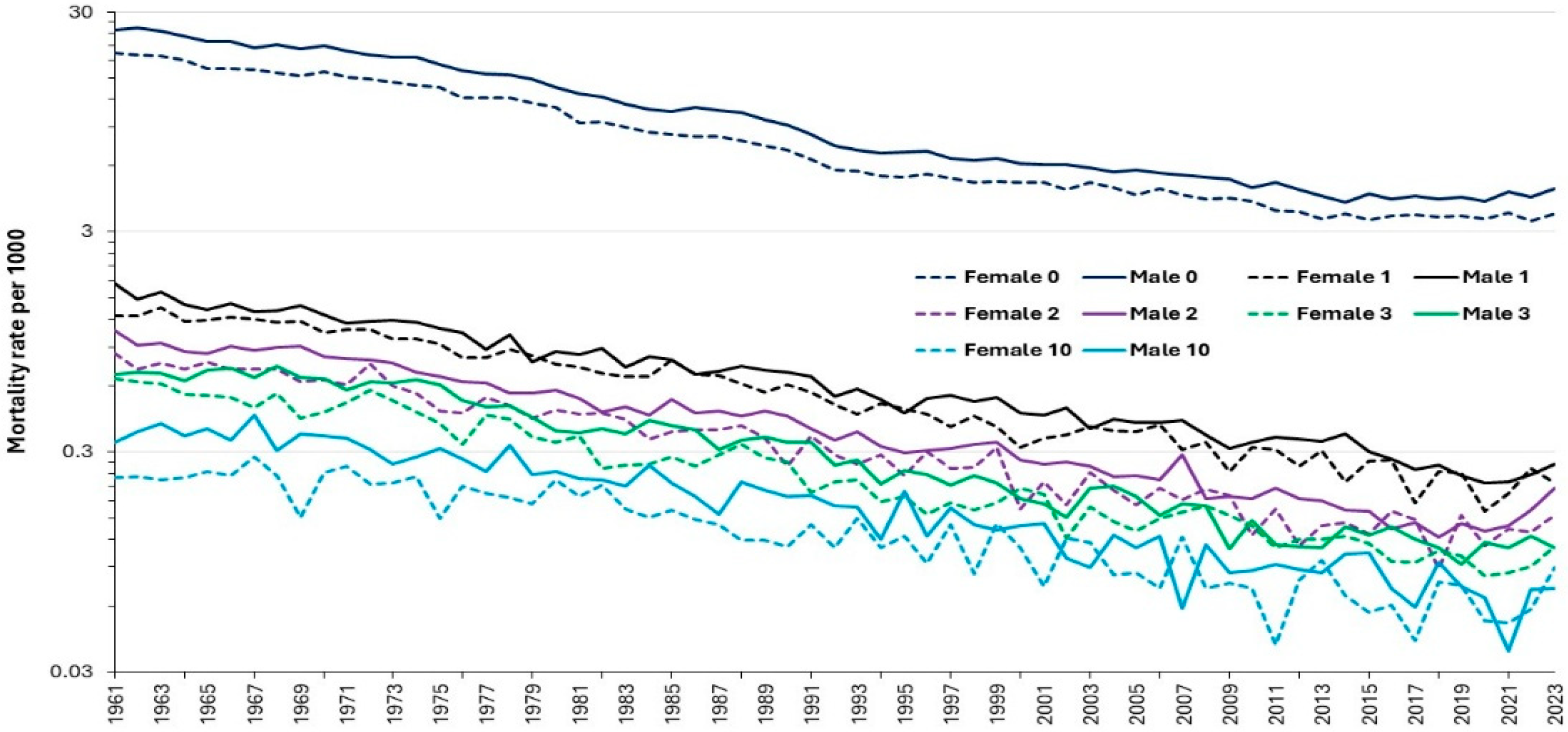

Figure 11 therefore becomes relevant in understanding how mortality contributes to pediatric bed demand. Thankfully the rate of childhood death in England and Wales has been declining for many years, especially in the first year of life. The rate of decrease is highest from the 1960’s to the 1990’s, then slows and reaches a possible asymptote around 2012. The decline between 1961 and 2023 ranges from 9-times for males aged 7 down to 2.3-times for females aged 13 and is 5.4- and 5.3-times respectively for males and females in the first year of life [

59].

Hence, while deaths made a larger contribution in former years, this has seemingly reached an asymptote, and at local level it is the absolute number of deaths rather than the mortality rate which is the variable of interest.

Despite these numbers being a total for England and Wales note the scatter around the trend lines and periods of consistently higher deaths. One key point is that the wobbles in the trend lines are sex and single year of age specific. This single year of age and gender specificity is illustrated in

Table A2 and

Figure A6 in the Appendix using a moving excess deaths calculation like that used for calculating excess winter mortality (EWM), see H.1-12 in S1, hence average deaths in the current 4 months versus average deaths in the previous 8 months.

Table A2 shows the point in time at which the moving excess mortality calculation reaches its maximum value (1993-20160, namely a different maximum and time of occurrence for each age/sex combination.

Table A2 shows the month at which the moving excess mortality calculation reaches the maximum value over a 24-year period (1993-2016). As can be seen in

Table A2 the maximum value for the moving mortality calculation depends on age and sex and reaches its maximum value between age 8-10 in females and 9-11 in males. The number of deaths in females reach a minimum value between age 7-11 and 7-10 in males. Deaths in males are typically 25% to 150% higher than females depending on the age. The minimum difference occurs at age 3. One standard deviation of Poisson variation will contribute ± 30% (males) ± 33% (females)to the moving mortality calculation for ages 7-10, but only ±4% to 5% at age 0. The profile for the maximum values only therefore has a modest Poisson contribution and looks to be a genuine outcome of age per se.

Clearly the highest values in

Table A2 are not the only maxima in the 26 years, and this is demonstrated for age 0 in

Figure A6 which shows multiple periods of excess mortality over time. Unlike in adults where the moving excess mortality calculation commonly reaches its maximum in winter (4 months ending at March) both

Table A2 and

Figure A6 show that maximum deaths in children can occur at any time of the year. The net result is profound complexity.

Such complexity is relevant when translated to the level of individual pediatric units. Assuming 200 pediatric units in England and Wales gives an average in 2023 of 13 deaths aged 0 per unit and 18 deaths per unit aged 0-14. At such small numbers Poisson and Negative Binomial randomness adds further statistical scatter to the potential end-of-life burden experienced each year at local level [

36]. It is also known that such persons typically experience an extended hospital stay and have multiple admissions whose frequency escalates as death approaches [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. This represents a significantly overlooked aspect of pediatric and neonatal average LOS and volatile bed demand.

3.10. Pediatric Length of Stay (LOS) and the Benchmarking Fallacy

This section is very important because there are many fallacies surrounding LOS benchmarking and the supposed reduction in costs when LOS is reduced. Detailed analysis of LOS is therefore a very important defensive step, since there is a widespread perception that LOS ‘should/ought’ to reduce ad-infinitum. While LOS did reduce somewhat rapidly during the 1970’s and 1980’s the rate of reduction dramatically reduced from the 1990’s onward, see C.1 in S1. This section also needs to address various fallacies surrounding LOS benchmarking, namely, “your LOS is higher than the national average, and therefore you must be inefficient and could save x% beds by moving to the national average”. This can be called the steady state fallacy, i.e., LOS is only of primary importance in bed demand when admissions and case mix are at steady state. However, it is first important to realize that at least 3 different measures for average LOS can be calculated at each pediatric unit.

3.10.1. Different Calculations for Average LOS Give Different Answers

In many countries the LOS is calculated as a simplistic count of the number of midnight stays in hospital. Patients admitted and discharged on the same day are assigned a zero day LOS. This gives highly misleading calculation of the real average LOS [

2,

3]. To this end

Figure 12 shows three alternative calculations for average LOS using ENT in England between 1998/99 and 2023/24. For simplicity the analysis includes both elective and emergency admissions, and a ‘real time’ estimate is calculated assuming that same day stay admissions are for 12 hours (0.5 days) and that the count of overnight bed days underestimates the real stay by 3.5% [

3].

As background, in England, any admission is counted as an overnight (ON) stay except if it is designated as an elective ‘day case’ (DC), i.e., it was intended to admit and discharge the patient for a procedure on the same day.

The apparent overnight (ON) LOS is calculated using the traditional midnight method and excludes any DC admissions. It is the traditional method for comparing average LOS between hospitals. This method is known to underestimate the real LOS [

3] and is very sensitive to the number of same day admissions which can include any elective same day stay which was not designated a DC, any same day stay emergency admissions, and any same day stay transfers between hospitals. Next comes a real time estimate of LOS which also includes day case admissions. This is probably a better measure of average LOS since it accounts for the shift to day surgery overtime. It is higher than the apparent LOS because it includes the 0.5 day estimate for any same day admission. Finally, an estimate of the real time LOS for all patients who have at least one midnight stay. It excludes any type of same day admission including day case. This is the genuine overnight average LOS and includes the residual elective patients not treated as a day case. As expected, the real average overnight LOS initially reduces up to 2012/13 and then begins to increase as increasingly more complex elective patients are left in the ON stay cohort and the least complex are treated as a day case.

It is important that all three measures of ‘average’ LOS be made available. This is especially so because the actual bed requirement depends on the number of genuine overnight stay patients (with their high average LOS) and the number of same day admissions (with a real-time LOS) which occupy an additional set of beds during daytime hours. If you take the traditional simplistic apparent ON LOS (midnight), the dashed line in

Figure 11, the calculation of the required beds will be considerably underestimated.

3.10.2. Trends in Pediatric LOS in England

Children tend to rapidly recover from illness and large reduction in LOS overtime is unlikely.

Figure 13 explores the trend in the real average LOS in England from 1998/99 to 2022/23. As can be seen the trend over 24 years is modest and may have increased in recent years. LOS in pediatric cardiology shows an unexplained cycle and to a lesser extent also pediatric neurology. There was a rapid transition in ENT between 2004/05 and 2007/08, probably due to a shift to day case but there is minimal change through to the arrival of COVID-19, and an increase since then. A similar rapid transition also occurred in pediatric neurology between 2005/06 and 2007/08, also likely to shift to day case. Pediatric neurology reaches a minimum in 2017/18 which is 2 years before COVID-19. Even at national level there is year-to-year volatility in LOS indicating that LOS is more complex than appreciated.

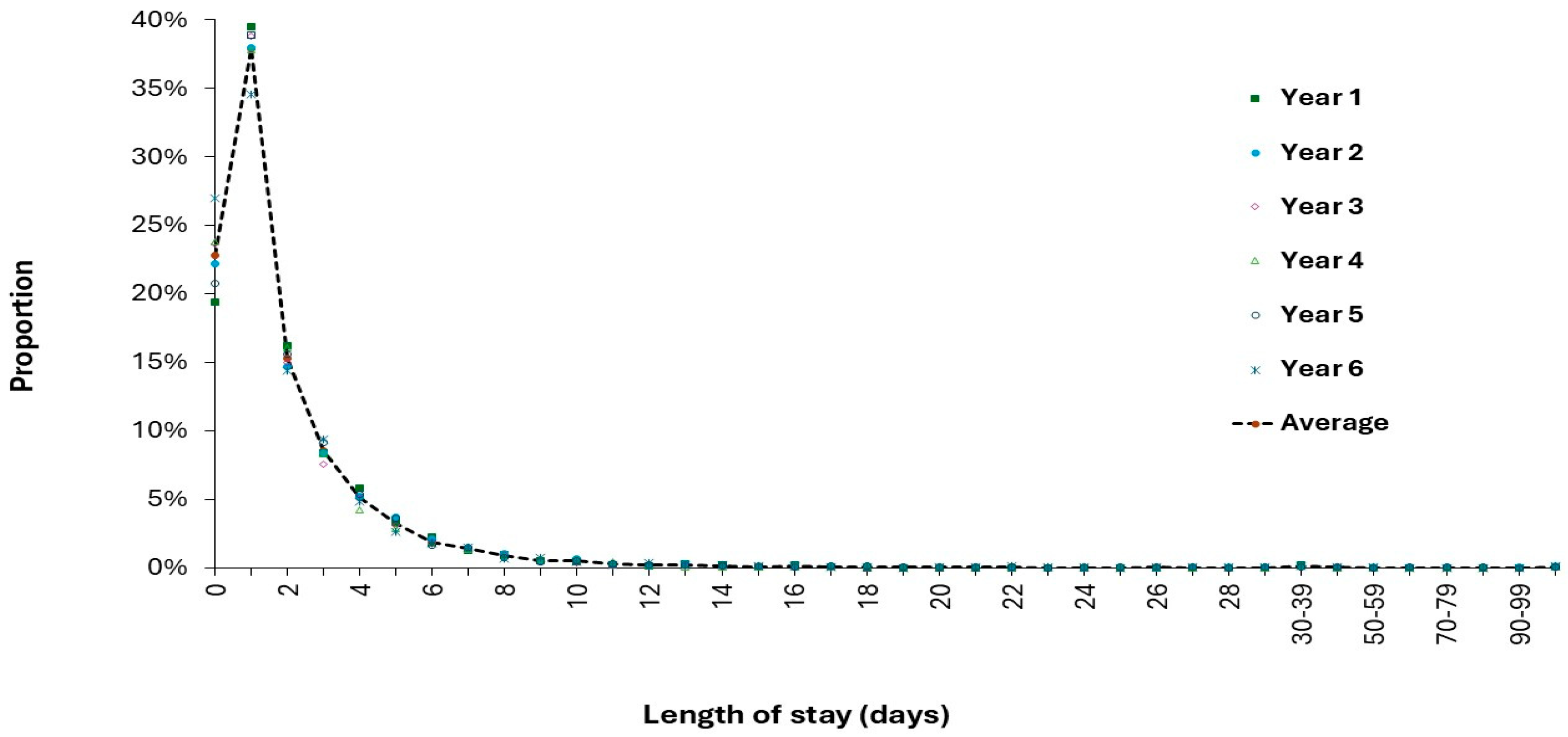

3.10.3. Average LOS from a Single Year is Subject to Sampling Error

Average LOS is not a constant but is subject to sampling error, especially as the size of the unit decreases [

27]. This is illustrated in

Figure 14 where the LOS distribution at a pediatric unit is shown over 6 consecutive years. There is no evidence that the distribution around the average is anything other than statistical scatter, i.e., the annual distribution in this pediatric unit is merely a subset of the larger 6-year average, which is a subset of a larger national LOS distribution and is therefore subject to sampling error [

27]. Sampling error is further magnified by the inability of LOS benchmarking tools to fully adjust for all the factors regulating LOS across all pediatric units, i.e., the diverse social groups surrounding each unit, distance to the hospital, spatiotemporal variation in infectious outbreaks, local levels of air pollution, allergens, and carcinogens, etc.

Table 3 summarizes the statistics for the six years in terms of annual admissions, average occupied beds, average LOS and proportion of same day stay admissions. Also given is the admissions and LOS for the subset of patients staying 13+ days.

Imagine that the pediatric unit has identified a need for more beds and commences the business case in Year 2 when the average LOS is the highest in 6 years at 2.4 days. The national average is 2.1 days, and it is suggested that if the unit were ‘efficient’ it would save 0.3 days or 12.5% of occupied beds. This will be assumed to occur and the supposed need for beds is duly reduced. None of the Managers or hospital Directors recognize the hidden fallacy and inform the pediatric doctors that inefficiency is half the problem behind their supposed need for more beds.

Even at annual level note the randomness in admissions (3207 to 4147), admissions with a stay of 13+ days (35 to 63 at ± 22% STDEV), average occupied beds (18.7 to 24.5), and the proportion of admissions which are admitted and discharged on the same day (19% to 27%). The maximum and minimum values in each column (in red/green bold) are randomly distributed between years, while the standard deviation (STDEV) of the average lies between 6% to 23% of the average depending on the variable. Note that this average sized English district general hospital has more occupied pediatric beds than total available beds in 70% of US pediatric units.

This data was from a moderately large (by international standards) general pediatric unit, now imagine breaking the case mix down to far smaller HRG/DRG level measurements. To illustrate further, a case study on LOS for appendix removal in all Australian hospitals over the years 2011/12 to 2022/23 is given in Supplementary material S10 [

60] with the expected dominating effect of unit size on apparent average LOS. It is suggested that such ‘benchmarking’ comparison is largely futile, probably driven by local factors, and that LOS reduction should only be pursued where there is genuine benefit to the patient and parents. In England, all diseases of the appendix (ICD codes K35 to K38) only account for 0.7% of pediatric admissions, hence, targeting this for LOS reduction is a pointless endeavor. Indeed, the diagnosis with the highest admissions, namely B34 (viral infection of unspecified site) only accounts for 4% of pediatric admissions. With 1680 pediatric ICD-10 3-digit diagnoses describing case mix, targeting a specific diagnosis is problematic. It is likely that any pediatric HRG/DRG will be a composite of so many conditions that specific benchmarking is dubious. Recall that HRG/DRGs are composed of conditions with a similar cost which is entirely different to a similar etiology. The fallacy regarding large reductions in costs by reducing LOS is explored in the Discussion and is an extension of similar comments regarding maternity LOS [

3].

3.11. Pediatric Demand is Intrinsically Unstable (Volatile)

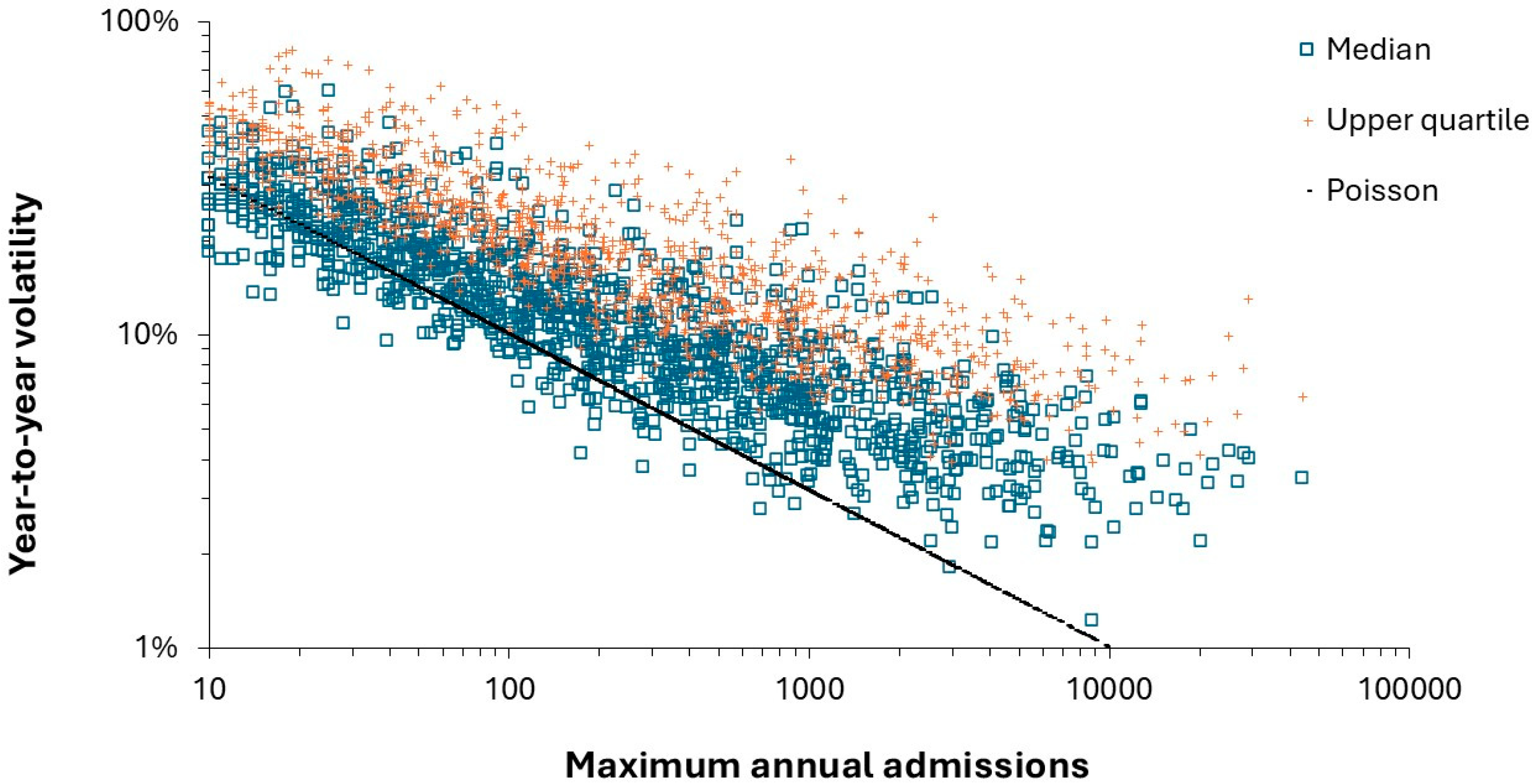

Figure 10 presented a picture of extreme volatility in bed demand. It is illustrative to determine exactly how volatile pediatric admissions are overtime.

Figure 15 shows the year-to-year median volatility for 1285 ICD-10 (3 digit) primary diagnoses associated with pediatric admissions aged 0-14.

In

Figure 15 the minimum possible volatility is set by Poisson variation where the standard deviation associated with any average is equal to the square root of the average, hence, the use of a log-log plot to display the data. One standard deviation of Poisson variation is shown as the black line. There will be some uncertainty because there is only 25-years of data, and the year-to-year volatility was deliberately underestimated by dividing by the maximum admissions in each of the paired years rather than the average. However, the key point is that the further a diagnosis lies from the dashed blue line the greater the intrinsic volatility due to the sensitivity of that condition to the external environment. Data lying along the upper edge are up to 8-times higher than could occur due to Poisson randomness.

Some 624 diagnoses (49% of the number of diagnoses) with less than 1.5-times Poisson variation only account for 10% of the total pediatric admissions. Diagnoses with >3-times higher volatility than Poisson variation account for 54% of pediatric admissions. Understandably, many of the highly volatile diagnoses are due to infections or conditions exacerbated by infections.

In addition to pathogens, will be the effect of fluctuating levels of allergens including various types of pollens, ozone levels (including thunderstorms) and air pollution [

89,

90,

91,

92,

93].

Hence, pediatric demand cannot be treated as a ‘steady state’ process. Recalling that Figure n is the volatility at annual level for the whole of England, and a move to daily volatility at local level leads to greatly amplified volatility due to the spatiotemporal granularity associated with all infectious outbreaks [

94], not to mention the interplay with regional weather patterns [

95,

96]. At the local level a diagnosis with the maximum admissions (in a worst year) only accounts for 300 admissions per annum and the volatility due to simple Poisson variation has escalated around 14-times higher. A diagnosis with around 10 admissions on the x-axis will only occur roughly once every 20 years at local level.

Figure 16 seeks to expand upon the concept of volatility by investigating the year in which each ICD-10 (3 digit) primary diagnosis had its maximum number of children’s admissions. For example, Amoebiosis (A06) had a maximum of 10 admissions in 2007/08. This was the maximum point in a cyclic trend commencing at a minimum of 2 admissions in 2005/06 and ending in another minimum of 1 admission in 2010/11. As can be seen, 2003/04 and 2004/05 had the least number of diagnoses at their maximum for admissions while 2018/19 had the highest number of diagnoses with maximum admissions.

Many infectious diseases are all known to show cyclic patterns, as do weather patterns, etc. One such cycle is illustrated in

Figure 17 for the common pediatric condition of croup where the arrival of COVID-19 is seen to interrupt the well-established high/low pattern.

While the long-term cycle in births will have some effect on the underlying pattern there is also a trend to higher pediatric admissions over time as the threshold for parents to take their child to the emergency department seems to be declining. The two COVID-19 years is an interesting case where pathogen interference from COVID-19 limited the range of pathogens in general. This was further reinforced by lockdowns also preventing pathogen spread and significantly reducing air pollution. This is counterbalanced by the fact that developments in point of care diagnostics and in medications mean that some diagnoses can now be treated in primary care or the emergency department. Nevertheless, complexity and hence volatility characterizes the trends in pediatric admissions for many diagnoses.

Finally,

Figure A4 in the Appendix shows the net effect of all the underlying volatility in LOS and admissions on the annual occupied pediatric beds in the English NHS from 1998/99 to 2023/24. As can be seen there is a cycle in bed demand which approximately follows the cycle in births. Around this cycle are high and low years. Note that the minimum in 2000/01 is not hugely different from 2020/21. However, bed demand appears to be drifting up over time. Recall that births initiate a cascade of admissions for each single-year-of-age, and that different pathogens have different single-year-of age profiles, see G.6,7 in S1.

The possibility also exists that increasing obesity among mothers is having longer term effects against child health with reported increased risk of asthma, obesity, coronary heart disease, stroke, and possibly infectious disease outcomes [

97,

98,

99].

From

Figure A4, note the difficulty in forecasting future demand in the past and almost certainly in the future. The aim is to acquire sufficient floor space to cope with an uncertain future plus the surge capacity to cope with the high years such as 1998/99, 2003/04, 2005/06, 2016/17, 2023/24, etc.

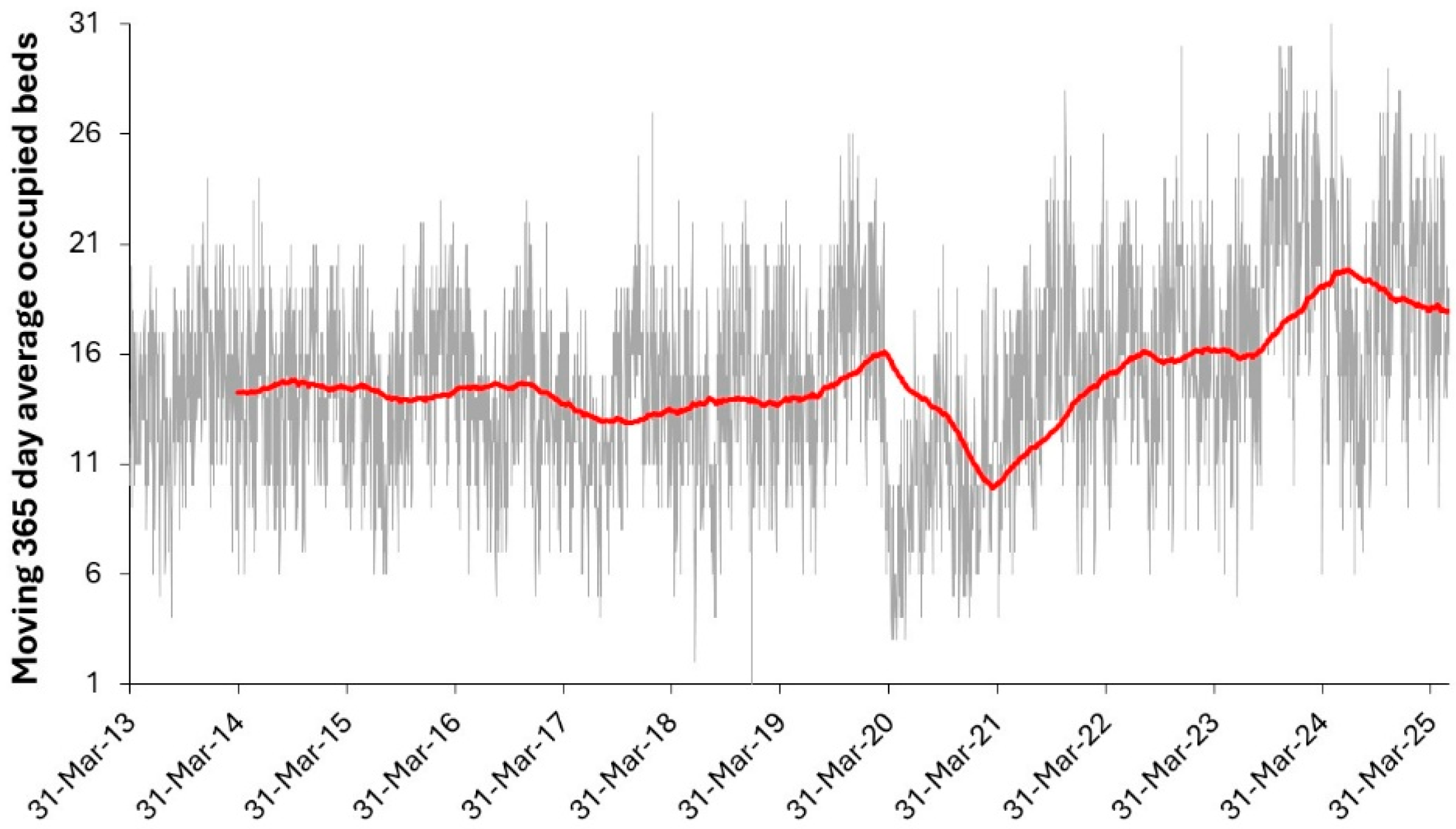

3.12. Effect of COVID-19 on Pediatric Admissions and Occupied Beds

Figure 18 suggested that COVID-19 was associated with a dramatic reduction in occupied pediatric beds. It is not widely recognized that COVID-19 exerted powerful non-specific effect on other human pathogens via the process of pathogen interference, see I.3 in S1, and that each different COVID-19 variant had unique single-year-of-age profiles, see G.6-G.7 in S1. These effects were then amplified by the intermittent lock down measures which acted by limiting pathogen transmission.

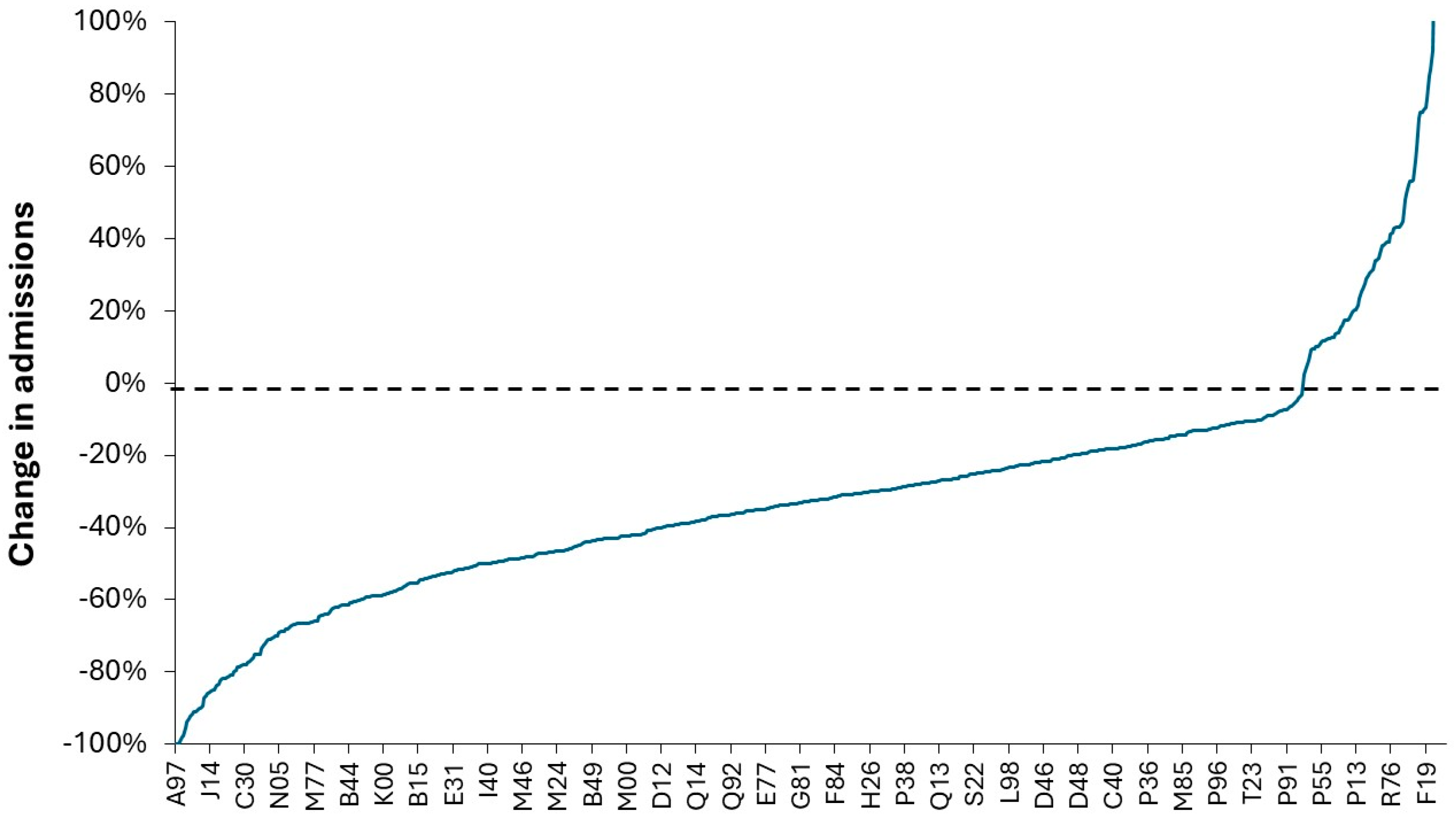

To this end

Figure 18 shows the effect of the first year of COVID-19 on admissions in children aged 0 to 14 for 730 neonatal and pediatric diagnoses which showed a statistically significant change. As can be seen the effect ranged from a 100% decrease for certain diagnoses such as dengue, neoplasms of the male genital organs and influenza through to >100% increase for diagnoses such as neoplasm of base of tongue, tic disorders, thyroiditis, poisoning by anesthetic gasses, effects of reduced temperature, neoplasms of multiple sites, fetus and newborn affected by complications of labor and delivery, and special examination for infectious/parasitic disease . The effect on influenza is confirmed by the fact that influenza in England and Wales dropped to zero detections just before the introduction of the first lock down, see G.6 in S1. The full list of diagnoses and percent change between 2019/20 and 2020/21 is provided in Supplementary material S11 [

48]. Note that the first year of COVID-19 in England was dominated by the Wuhan and Alpha strains. It is suggested that lockdowns alone are unable to explain this vast range in behavior.

There is also considerable age specificity in the change in admissions for various diagnoses seen during the 1st year of COVID-19 (see Supplementary materials S11) which strongly suggest that far more complex changes than would occur simply from lockdowns. In this analysis from 1680 ICD-10 (3-digit) pediatric diagnoses some 820 (49%) were excluded due to very low numbers or no statistically significant change in any age. In the remaining 850 diagnoses there was no statistically significant change in 62% of age 0 diagnoses and around 30% to 40% of the other age bands. This does not support a simple hypothesis that parents were in general afraid to take their children to hospital since statistically significant change is restricted to certain age-diagnosis combinations.

The strongest argument against a simple lockdown-based outcome is the fact that the Table in Supplementary material S11 shows statistically significant increases in admissions for 104 diagnoses for the first year of life (32% of the statistically significant changes), 50 diagnoses for age 1-4 , 46 diagnoses age 5-9, and 47 diagnoses for age 10-14, all around 10% of the statistically significant changes in these age bands. Some of the increases are understandable such as T55 (toxic effects of soaps and detergents) based on government advice for fastidious handwashing which some parents seemingly took to extremes in infants and children. Likewise, the increase in Z11 (screening for infectious disease) is understandable and is likely to have occurred in pediatric assessment units.

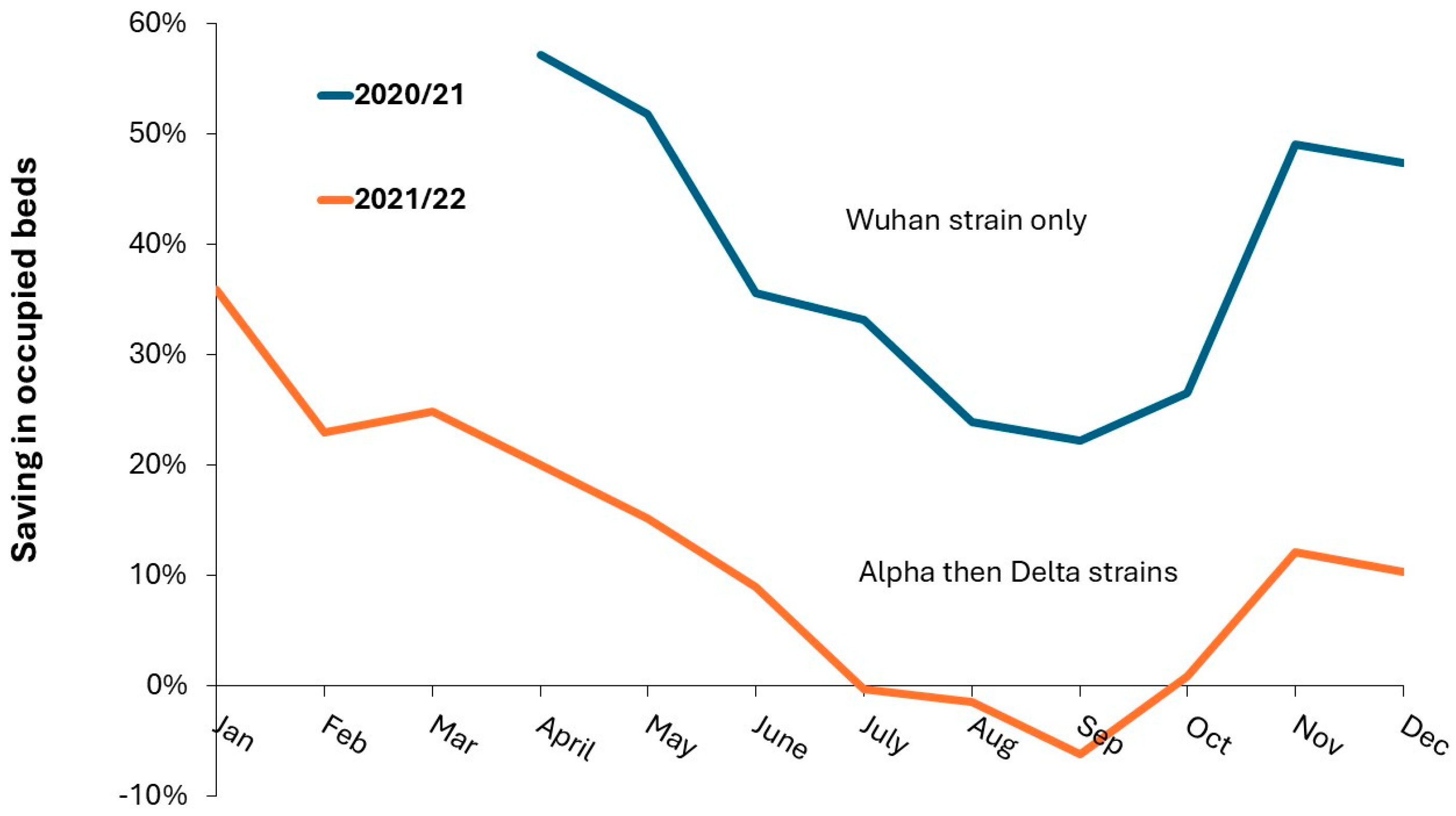

Figure 19 explores the concept that the monthly profile of pediatric bed demand during the 1st and 2nd years of COVID-19 has a strong infectious basis either as the direct effect of infection or the secondary exacerbation of existing conditions. In

Figure 20 bed occupancy at the Great Western Hospital in Swindon, England is compared in each of the first two pandemic years against the average bed demand in 2018/19, 2019/20, 2022/23, 2023/24., i.e., the two before and after years. A saving in occupied beds is shown as a positive number. Note in

Figure 20 that bed occupancy returned to pre-pandemic levels from July to September of 2021 with only a 10% saving in occupied beds in November and December of 2021.

To understand

Figure 19 three points need to be understood.

Different strains of COVID-19 have divergent single-year-of-age profiles in their degree of infectiousness and their deleterious effects, see G.6, G.7in S1.

COVID-19 strains exert powerful effects on the range of prevailing pathogens via pathogen interference, see G.6 in S1.

Lockdowns, including school closures, during the pandemic only acted to reduce the transmission of the prevailing pathogens – only when they were in place. Note all lockdown measures were removed toward the end of the 2021/22 financial year [

100]

As can be seen in

Figure 19 the initial Wuhan strain was associated with a large reduction in pediatric bed occupancy and the transition to the Alpha and Delta strains was associated with a diminished reduction in bed occupancy, i.e., a 60% reduction in April 2020 declining to a 20% reduction in April 2021. July to October of 2021 shows either no effect of a slight increase in bed demand especially in September of 2021.

The mechanisms by which pathogen interference can influence seemingly unrelated conditions will be covered later.

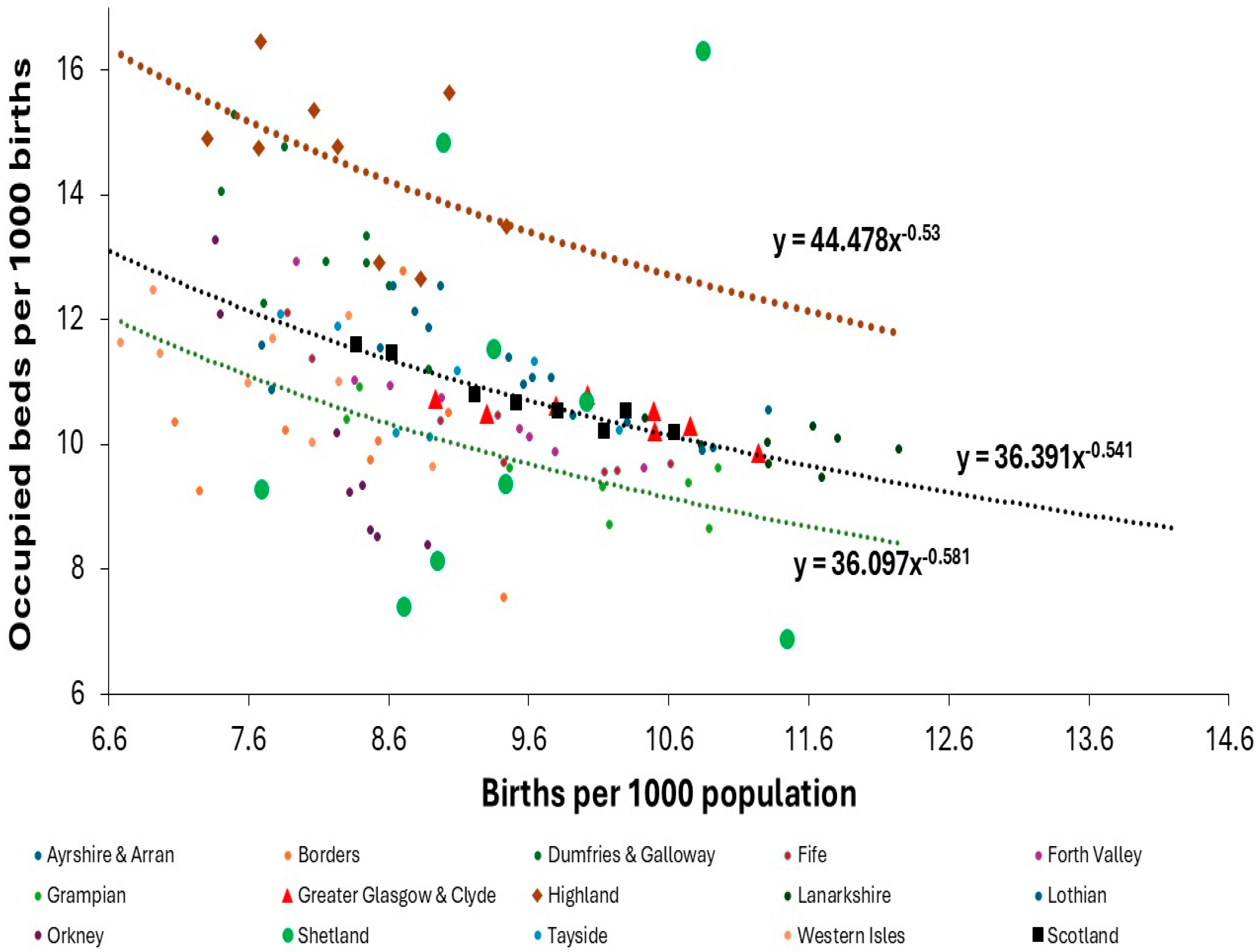

3.13. Benchmarking International Pediatric Bed Demand

It was previously suggested that international demand for adult inpatient care could be benchmarked by plotting the ratio of occupied bed per 1000 deaths versus the ratio of deaths per 1000 population (the crude mortality rate) [

1,

2]. It was demonstrated that the USA had very low levels of occupied adult beds, placing it among the less developed countries.

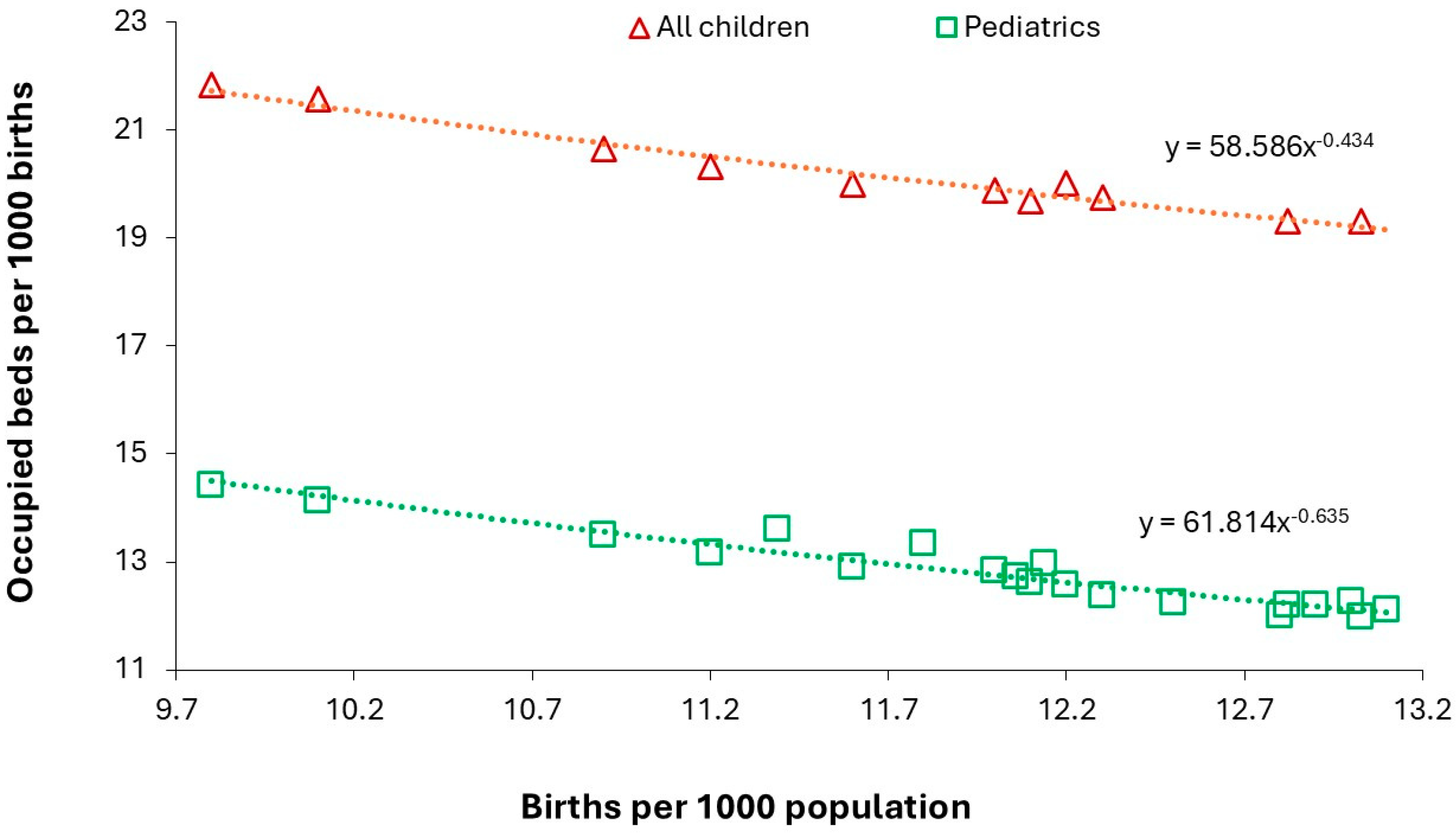

Using the same reasoning for pediatric bed demand would lead to a plot of occupied beds per 1000 births versus the births per 1000 population (the crude birth rate).

Figure 20 illustrates this using data from England. Both births and population are readily available for all world countries and at regional and local level. Which leaves each country to measure the level of occupied beds each year. The available beds are not a good measure of the expressed bed demand since the occupancy rate is largely determined by the average size, which is extremely low in the USA, i.e., actual occupied beds may be surprisingly low.