1. Introduction

The development of the epidermis plays a central role in driving the morphogenesis of the

Caenorhabditis elegans (

C. elegans) embryo. Epidermal morphogenesis is a complex and dynamic process that requires the collaboration of multiple features such as mechanical forces and signaling [

1]. The epidermis is the outer cellular layer of an organism and plays an important role in embryogenesis as this tissue regulates the shape of the animal during the developmental process [

2]. Understanding this process is crucial for uncovering the mechanisms of morphogenesis and has significant implications for studying developmental diseases and related gene function [

3].

C. elegans is a useful model to study morphogenesis and provides insights into various human diseases due to its fixed cell number, stereotypical cell division pattern, rapid developmental process, and the ease and economy with which genetic experiments such as RNA interference (RNAi) can be performed [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Epidermal morphogenesis involves complex cell-to-cell interactions and coordination between multiple genes. The intricate process of epidermal development in embryos is often described by classifying it into distinct phenotypic stages, which provide a valuable framework (

Figure 1A). This facilitates the analysis of phenotypic embryonic images, thereby elucidating the underlying mechanisms. Several influential studies have reported the critical role of epidermal morphogenesis using defective embryonic images to elucidate aspects such as epidermal cell fate junctions, interactions, and regulatory mechanisms [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Incorporating a temporal perspective is essential to developmental studies of this process. A pioneering study successfully used RNA-sequencing analysis to explore linkages in developmental timing and provide comprehensive insights into temporal and spatial dynamics [

13]. Recently, a novel, large-scale study used RNAi and four-dimensional imaging of specialized strains tagged with fluorescent proteins to systematically characterize embryonic development [

14]. However, current image-based research methods focus heavily on defective phenotypes. Although certain genes are involved in epidermal development, their inactivation does not cause obvious morphological abnormalities, and the epidermal developmental process can still be completed. Instead, the progression through specific embryonic stages is prolonged (

Figure 1B). This often requires complex experimental designs aimed at converting developmental delays into observable defects. One such method entails combining weak-allele mutant strains with RNAi to induce more severe developmental defects than with single mutants. This highlights the need for a novel approach emphasizing the developmental timing and addressing the omissions in traditional approaches during the epidermal development process.

Recent advancements in deep learning-based image analysis have led to substantial breakthroughs across various research fields, particularly in medical imaging, where automated analysis enables more accurate and efficient diagnoses [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. This method has also transformed the approach to developmental biology, expanding our understanding of morphogenesis, embryogenesis, behavior, and even aging in

C. elegans. For instance, image segmentation models have been used to analyze the “morphodynamics” of early embryos [

20], and object detection models have characterized multiple features of

C. elegans in microfluidic devices, including size, movement, speed, and fluorescence [

21], apart from aiding the study of worm behavior [

22]. Furthermore, image similarity analysis models have been applied to identify cell divisions in early embryos automatically [

23], and classification models have been employed to study lifespan [

24]. However, most studies have focused on early embryos, tracking cell lineage or behavior, while studies focusing on epidermal morphogenesis are lacking.

This study introduces a deep learning-based image analysis approach, offering a more direct and temporally focused methodology compared to traditional methods. This approach is particularly capable of highlighting cases where the effects on development are not severe enough to cause detectable changes in the phenotype but are manifested as developmental delays. Time-lapse differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy was used to monitor the developmental timing of each stage of epidermal morphogenesis in

C. elegans. Our approach combined two classic deep learning models: ResU-Net [

25,

26] was used for noise reduction, thereby facilitating focus on embryonic regions, and ResNet [

27] was employed to predict embryonic stages and generate a developmental timeline to facilitate real-time-tracking of the process.

This approach was successfully applied to experiments screening three genes, namely, ajm-1, tes-1, and leo-1. These genes are known to be involved in epidermal morphogenesis in C. elegans but RNAi treatment targeting them does not exhibit noticeable phenotypic defects until the late elongation phase. Temporal analysis indicated that RNAi treatment revealed the impacts of these genes on developmental timing at specific embryonic stages.

This study posits that the time taken by each specific epidermal developmental stage can provide critical insights into the regulation of epidermal morphogenesis. Therefore, in the absence of apparent phenotypic defects, temporally assessing embryogenesis offers an effective approach to detect subtle developmental changes. Shifting the focus from visible phenotypic defects to developmental timing is expected to provide a platform for identifying genes that contribute to epidermal morphogenesis. This approach may also have broad applicability to other image-based studies, such as embryogenesis in various organisms and the early diagnosis of certain developmental disorders that arise during embryogenesis but remain subtle and difficult to detect by conventional methods.

3. Discussion

In this study, we proposed a deep learning-based approach for analyzing C. elegans epidermal morphogenesis. Unlike traditional approaches that focus on defective phenotypes, our approach for gene function analysis focused on the time required for completion of each developmental stage.

3.1. Deep Learning-Based Diagnostic Tool for Temporal Analysis

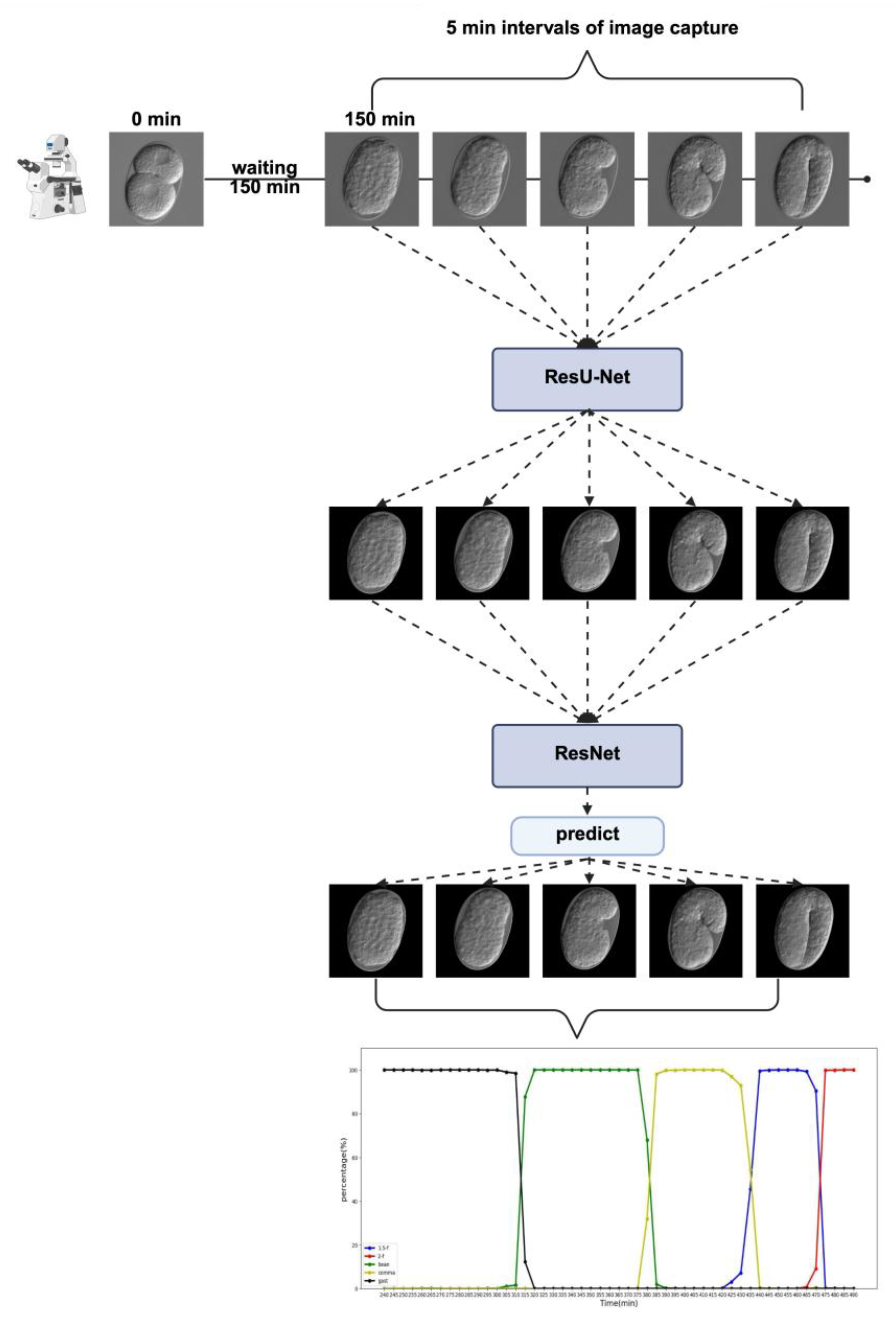

We implemented a new diagnostic approach for epidermal morphogenesis. Two classic deep learning models were used. First, we used ResU-Net to process the raw images. Next, we continuously predicted the stage from time-lapse images using ResNet. The time required for each stage completion was then calculated.

What sets our approach apart is the way these two models were integrated. By using ResU-Net for denoising, we retained only the pixel values corresponding to regions of interest, thereby enabling the subsequent stage prediction to focus more specifically on the meaningful areas of the image. This design also highlights the potential applicability of our method to other types of noisy microscopy images or other medical images, as it identifies and separates important regions in advance.

For ResNet, softmax function’s ability to assign probabilities to classification labels was used to dynamically visualize the embryonic development process and transitional periods. Furthermore, the UMAP projection of the predicted labels after training showed that the classified stages clustered sequentially along the correct embryonic developmental trajectory rather than being randomly distributed, indicating that the model had learned semantically meaningful features aligned with the temporal progression of morphogenesis.

3.2. Calculations of Time Required for Each Stage in Control(RNAi) Group

In this study, we defined the strict 0-min time point at the 2-cell stage of the embryo. Time-lapse images were then captured every 5 min, starting from 150 min, until the completion of the 2-fold stage. Using time as the horizontal axis and the predicted probability of each stage as the vertical axis, we created a timeline from the dorsal intercalation stage to the 2-fold stage, with different colors representing each stage. By measuring the duration of different colored segments in the predicted timeline, we were able to estimate the duration of each embryonic stage.

Although the current approach occasionally misclassified individual images within the entire time-lapse dataset, the fixed epidermal development process made such errors easily identifiable. For example, misclassified images appeared as isolated points of a different color within a continuous segment on the predicted timeline, making them visually distinguishable. Therefore, when images were misclassified (i.e., appeared as a different stage within a segment of a single predicted color on the timeline) they were assigned to the corresponding embryonic stage for the purpose of calculating the duration of each stage.

During the model training phase, no specific constraints were imposed on embryo orientation. As a result, when applying the model to actual time-lapse data, the method could process images unrestrictedly as long as the entire embryo fit within the 256×256 pixels frame. In the control(RNAi) group, the standard error of the mean for each stage was within 2 min, indicating low variability in our measurements. However, the measurement of duration for the dorsal intercalation and ventral enclosure stages showed greater individual variability compared to later stages. This variability might be due to the embryos within the eggshell not aligning their ventral or dorsal side toward the microscope, or to some embryos being positioned at an angle to the eggshell. This could introduce inconsistency in the duration measurements during these stages. Further analyses with angle correction may improve measurement accuracy in future studies.

3.3. Trial to Temporal Analysis of the Gene Function in RNAi Knockdown Animals

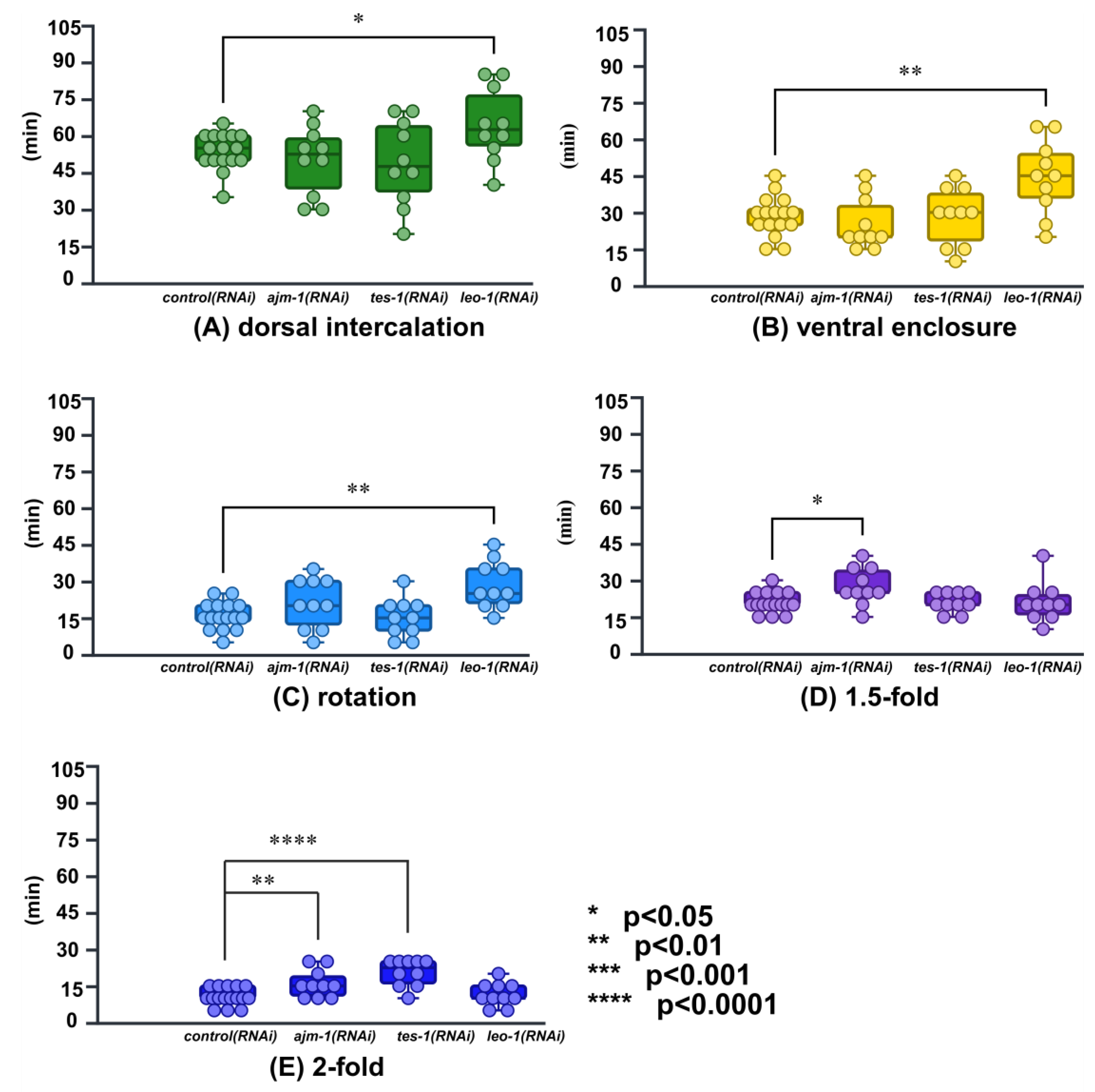

This study employed a diagnostic approach that applies computer vision to analyze temporal patterns. Specifically, it divided epidermal morphogenesis into five stages and calculated the duration of each stage. Using this method, we detected developmental delays in three selected genes at specific embryonic stage, clarifying the stages of epidermal development to which each gene specifically contributed.

In the analysis of

leo-1(RNAi) animals, developmental delays were observed in three early embryonic stages: dorsal intercalation: (delayed by 20.00%), ventral enclosure (delayed by 56.53%), rotation (delayed by 44.11%). No delays were detected at the 1.5-fold and 2-fold stages. This suggests that

leo-1 was primarily involved in early epidermal development and did not contribute substantially to later stages.

leo-1, as a component of the PAF1C complex, collaborated with the other four components to regulate cell migration and cell positioning, which are critical for epidermal development [

28]. In the current study, the delays observed from the dorsal intercalation to the rotation stage in

leo-1(RNAi) animals likely resulted from reduced LEO-1 expression in early epidermal development, impairing the timely progression of normal cell migration and positioning. Since no delays were observed at the 1.5-fold and 2-fold stages, it is hypothesized that the reduced

leo-1 expression permitted cell positioning to proceed with delays but without major disruption. Consequently, late-stage epidermal development could proceed on schedule. This further suggests that

leo-1 had weak or no contribution to later stages of epidermal development.

In the analysis of

ajm-1(RNAi) animals, developmental delays were observed at two late embryonic stages: 1.5-fold (delayed by 31.40%) and 2-fold (delayed by 50.66%). No delays were detected from dorsal intercalation to the rotation stage. This suggests that

ajm-1 contributed primarily during the elongation phase of late epidermal development, with minimal involvement in earlier stages.

ajm-1 is essential for the integrity of epithelial junctions and embryonic elongation [

29]. Our temporally detailed analysis is consistent with these findings. Although previous research reported developmental delays in

ajm-1 embryos [

29], the reported timing spanned a broad period from enclosure to the 2-fold stage. Using our approach, we clarified that delays specifically occurred at the 1.5-fold and 2-fold stages, providing complementary insights into previous findings.

In the analysis of

tes-1(RNAi) animals, developmental delays were observed only at the 2-fold stage (delayed by 93.06%). This suggests that

tes-1 played a specific role in embryonic elongation starting from the 2-fold stage, with minimal contribution to early epidermal development and the elongation process prior to the 2-fold stage.

tes-1 localizes to junctions in a tension-dependent manner from the 2-fold stage, stabilizing the junctional actin cytoskeleton during embryonic morphogenesis [

30]. Therefore, the observed 2-fold stage delay in

tes-1(RNAi) animals likely reflects the critical role of

tes-1 in maintaining cell–cell contacts necessary for subsequent embryonic elongation. Our findings confirm previous studies and provide new insights based on a different analytical approach.

3.4. Contributions and Limitations of the Current Approach

The proposed approach successfully diagnoses the specific developmental stages to which the three genes contributed to embryonic epidermal development. Using this approach, genes identified through a genome-wide RNAi screen can be further analyzed to determine their specific contributions to developmental progression. This is particularly relevant for genes where development timing as demonstrated with tes-1(RNAi) in this study, needs to be considered. By applying this approach to a secondary screening using C. elegans homologs of genes associated with epidermal-related diseases or developmental delay in other model organisms, it could serve as a complementary analytical approach to existing methods.

Furthermore, this approach holds potential for detecting certain developmental abnormality related diseases that arise during embryogenesis but remain undetected by conventional methods. In contrast to traditional studies that primarily focus on postnatal pathogenesis [

31], our method emphasizes early screening, when subtle developmental defects occur.

However, the current approach exhibits instability during the transition period, where two distinct patterns were observed. This may be because transition periods exhibit characteristics of mixed stages, and the model has not been specifically trained to recognize these periods, leading to uncertainty in predictions. While misclassifications occasionally occurred during the non-transition period, they can be corrected after considering the temporal context. Nevertheless, the model is not yet fully reliable and further optimization is required to improve its accuracy and reliability.

Another limitation is that the current approach produced several unstable timelines when predicting time-lapse data from the RNAi group. We suspect that this instability arose because the model detected subtle defects in the embryos following RNAi treatment that are often imperceptible to the human eye. Exploring how deep learning can further leverage its ability to discern these subtle defects and uncover their underlying causes could be intriguing for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L.; methodology, F.L.; software, F.L.; validation, F.L., P.L.; formal analysis, F.L., P.L.; investigation, F.L.; resources, F.L., M.O. and L.K.C.; data curation, F.L. and P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L.; writing—review and editing, L.K.C., Y.K., and M.I.; supervision, Y.K. and M.I.; project administration, Y.K. and M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Key events in Caenorhabditis elegans embryonic epidermal development process. (A) Six stages of embryonic epidermal development in C. elegans, which were predicted using deep learning models. (B) Embryos exhibiting developmental impacts temporally following RNA interference treatment. All images were processed by the ResU-Net model trained in this study.

Figure 1.

Key events in Caenorhabditis elegans embryonic epidermal development process. (A) Six stages of embryonic epidermal development in C. elegans, which were predicted using deep learning models. (B) Embryos exhibiting developmental impacts temporally following RNA interference treatment. All images were processed by the ResU-Net model trained in this study.

Figure 2.

ResU-Net performance diagram (A) ResU-Net IoU results diagram. The IoU scores are used to evaluate accuracy. The green line represents the IoU score for the validation set, while the red line indicates the IoU score for the training set. (B) ResU-Net loss diagram. The green line represents the loss for the validation set, while the red line indicates the loss for the training set. (C) ResU-Net also performs well in deliberately prepared images with severe noise. from left to right, mixed with other embryos in the frame, focus issues, presence of bubbles around the embryo, and presence of tissue debris around the embryo. The top row shows the original images, whereas the bottom row displays the processed results.

Figure 2.

ResU-Net performance diagram (A) ResU-Net IoU results diagram. The IoU scores are used to evaluate accuracy. The green line represents the IoU score for the validation set, while the red line indicates the IoU score for the training set. (B) ResU-Net loss diagram. The green line represents the loss for the validation set, while the red line indicates the loss for the training set. (C) ResU-Net also performs well in deliberately prepared images with severe noise. from left to right, mixed with other embryos in the frame, focus issues, presence of bubbles around the embryo, and presence of tissue debris around the embryo. The top row shows the original images, whereas the bottom row displays the processed results.

Figure 3.

ResNet performance diagram. (A) ResNet validation performance diagram. Different colors of blue, orange, green, and red, represent “Accuracy,””Precision,””Recall,” and ”F1-Score,” respectively. (B) Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) reveals that the image classification model can accurately capture the key semantic features of each embryonic stage. On the left side of each subcategory is the embryo image after ResU-Net processing, whereas the right side displays the image following Grad-CAM analysis. Red arrows indicate areas with high weightings (C) UMAP visualization of feature representations from the validation dataset using the ResNet model. Each point represents a single embryo image, colored according to its predicted developmental stage. Black lines indicate the correct developmental trajectory of C. elegans, illustrating the temporal order of embryogenesis.

Figure 3.

ResNet performance diagram. (A) ResNet validation performance diagram. Different colors of blue, orange, green, and red, represent “Accuracy,””Precision,””Recall,” and ”F1-Score,” respectively. (B) Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) reveals that the image classification model can accurately capture the key semantic features of each embryonic stage. On the left side of each subcategory is the embryo image after ResU-Net processing, whereas the right side displays the image following Grad-CAM analysis. Red arrows indicate areas with high weightings (C) UMAP visualization of feature representations from the validation dataset using the ResNet model. Each point represents a single embryo image, colored according to its predicted developmental stage. Black lines indicate the correct developmental trajectory of C. elegans, illustrating the temporal order of embryogenesis.

Figure 4.

Screened timeline examples that show misclassification and the two observed patterns of transition periods. Different colors of black, green, yellow, sky blue, purple, and dark blue represent “before intercalation,” “dorsal intercalation,” “ventral enclosure,” “rotation,” “1.5-fold,” and “2-fold” stages: (A) Misclassification in the timeline. (B) Oscillating between high probabilities for two different stages during transition period. (C) Maintaining a low probability during transition period.

Figure 4.

Screened timeline examples that show misclassification and the two observed patterns of transition periods. Different colors of black, green, yellow, sky blue, purple, and dark blue represent “before intercalation,” “dorsal intercalation,” “ventral enclosure,” “rotation,” “1.5-fold,” and “2-fold” stages: (A) Misclassification in the timeline. (B) Oscillating between high probabilities for two different stages during transition period. (C) Maintaining a low probability during transition period.

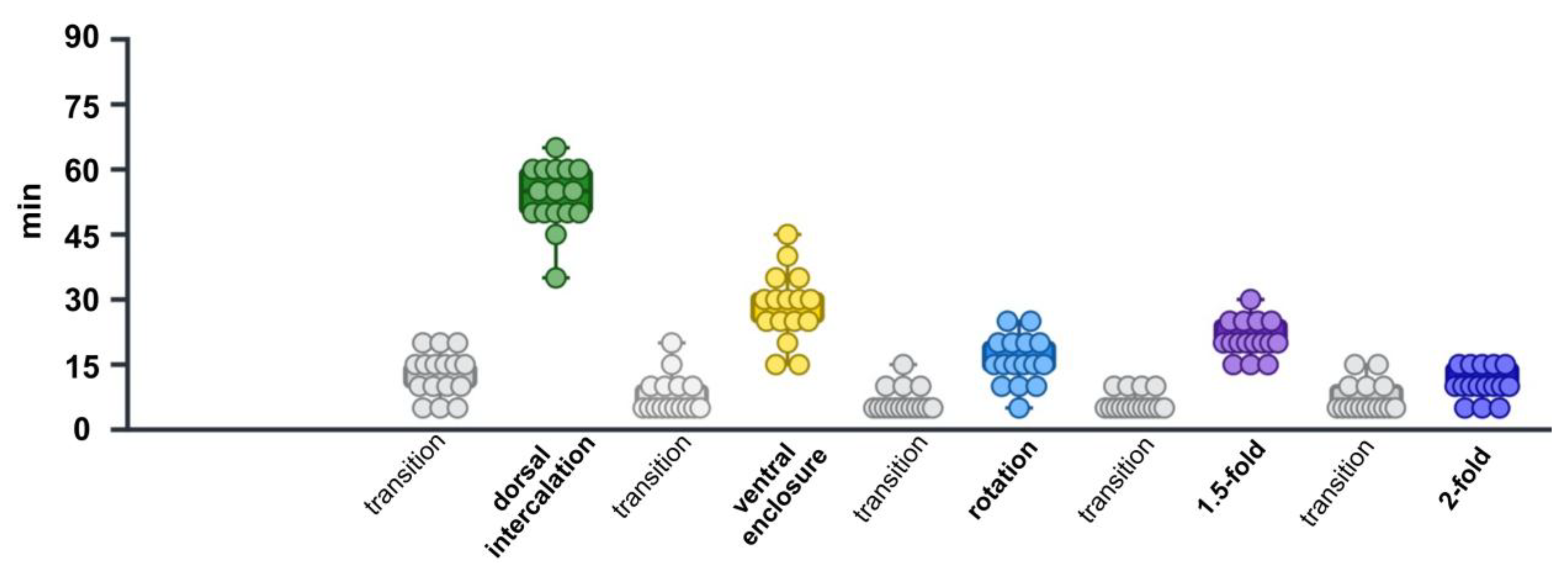

Figure 5.

Time requirements for control(RNAi) embryonic development in each stage. Different colors of black, green, yellow, sky blue, purple, dark blue, and grey represent “before intercalation”, “dorsal intercalation,” “ventral enclosure,” “rotation,” “1.5-fold,” and “2-fold”, “transition” stages, respectively. Each dot represents the time required by a single embryo to undergo each specific embryonic stage.

Figure 5.

Time requirements for control(RNAi) embryonic development in each stage. Different colors of black, green, yellow, sky blue, purple, dark blue, and grey represent “before intercalation”, “dorsal intercalation,” “ventral enclosure,” “rotation,” “1.5-fold,” and “2-fold”, “transition” stages, respectively. Each dot represents the time required by a single embryo to undergo each specific embryonic stage.

Figure 6.

Calculated and compared duration of embryonic development in each stage and, successfully defined specific embryonic stages affected by RNAi treatment of ajm-1, tes-1, and leo-1; ajm-1(RNAi) was delayed in the 1.5-fold, 2-fold stages and, transition periods; tes-1(RNAi) was delayed in the 2-fold stage; leo-1(RNAi) was delayed in dorsal intercalation, ventral enclosure, and rotation stages. control: n = 16; ajm-1(RNAi), tes-1(RNAi), and leo-1(RNAi): n = 10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001; unpaired Student’s T-test. (a) dorsal intercalation. (b) ventral enclosure. (c) rotation. (d) 1.5-fold. (e) 2-fold. Each dot represents the time required by a single embryo to undergo each specific embryonic stage.

Figure 6.

Calculated and compared duration of embryonic development in each stage and, successfully defined specific embryonic stages affected by RNAi treatment of ajm-1, tes-1, and leo-1; ajm-1(RNAi) was delayed in the 1.5-fold, 2-fold stages and, transition periods; tes-1(RNAi) was delayed in the 2-fold stage; leo-1(RNAi) was delayed in dorsal intercalation, ventral enclosure, and rotation stages. control: n = 16; ajm-1(RNAi), tes-1(RNAi), and leo-1(RNAi): n = 10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001; unpaired Student’s T-test. (a) dorsal intercalation. (b) ventral enclosure. (c) rotation. (d) 1.5-fold. (e) 2-fold. Each dot represents the time required by a single embryo to undergo each specific embryonic stage.

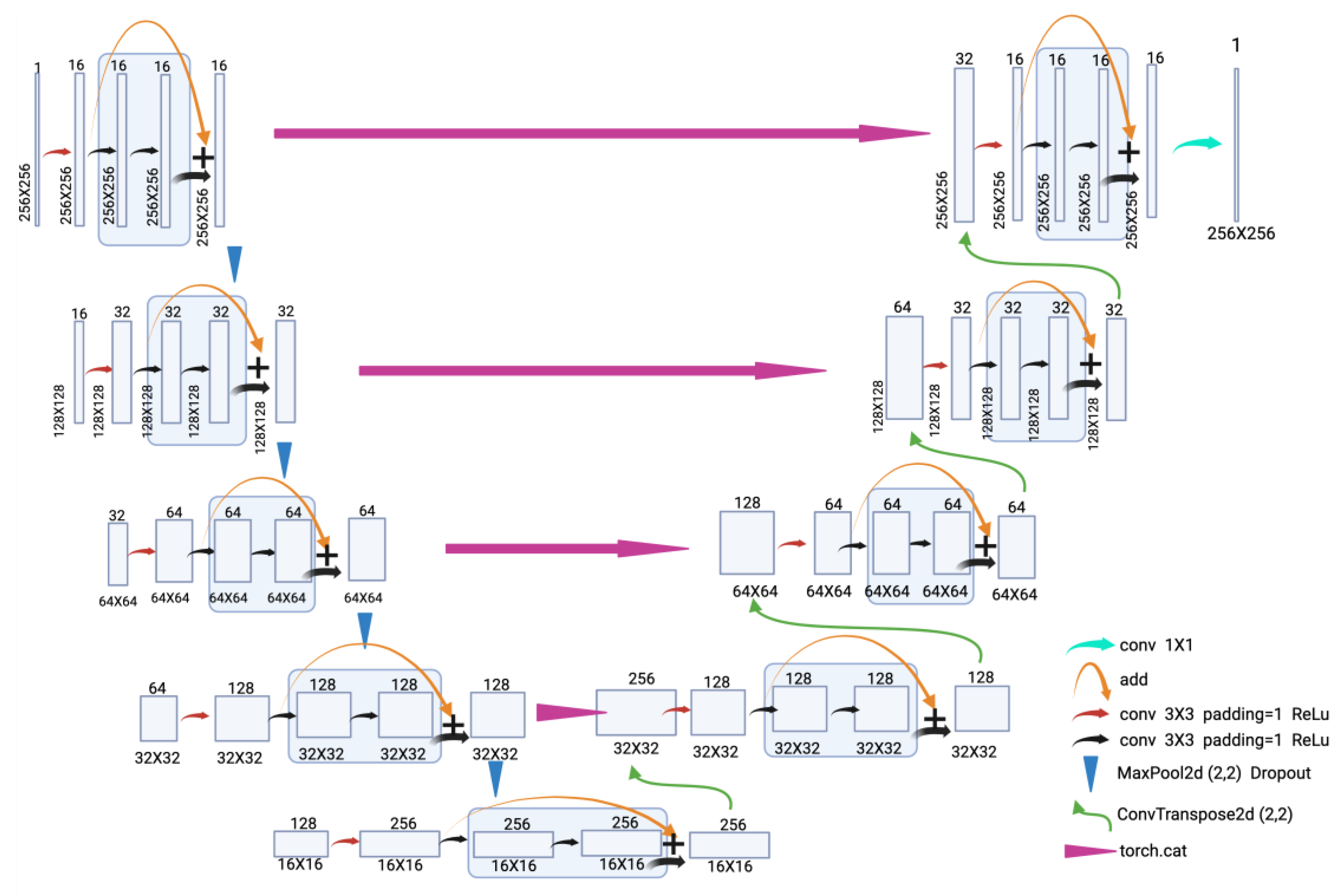

Figure 7.

ResU-Net architecture. Residual blocks are incorporated into each encoder and decoder layer. The number of channels is indicated above each box. Different arrows represent different operations, and the plus sign indicates tensor addition.

Figure 7.

ResU-Net architecture. Residual blocks are incorporated into each encoder and decoder layer. The number of channels is indicated above each box. Different arrows represent different operations, and the plus sign indicates tensor addition.

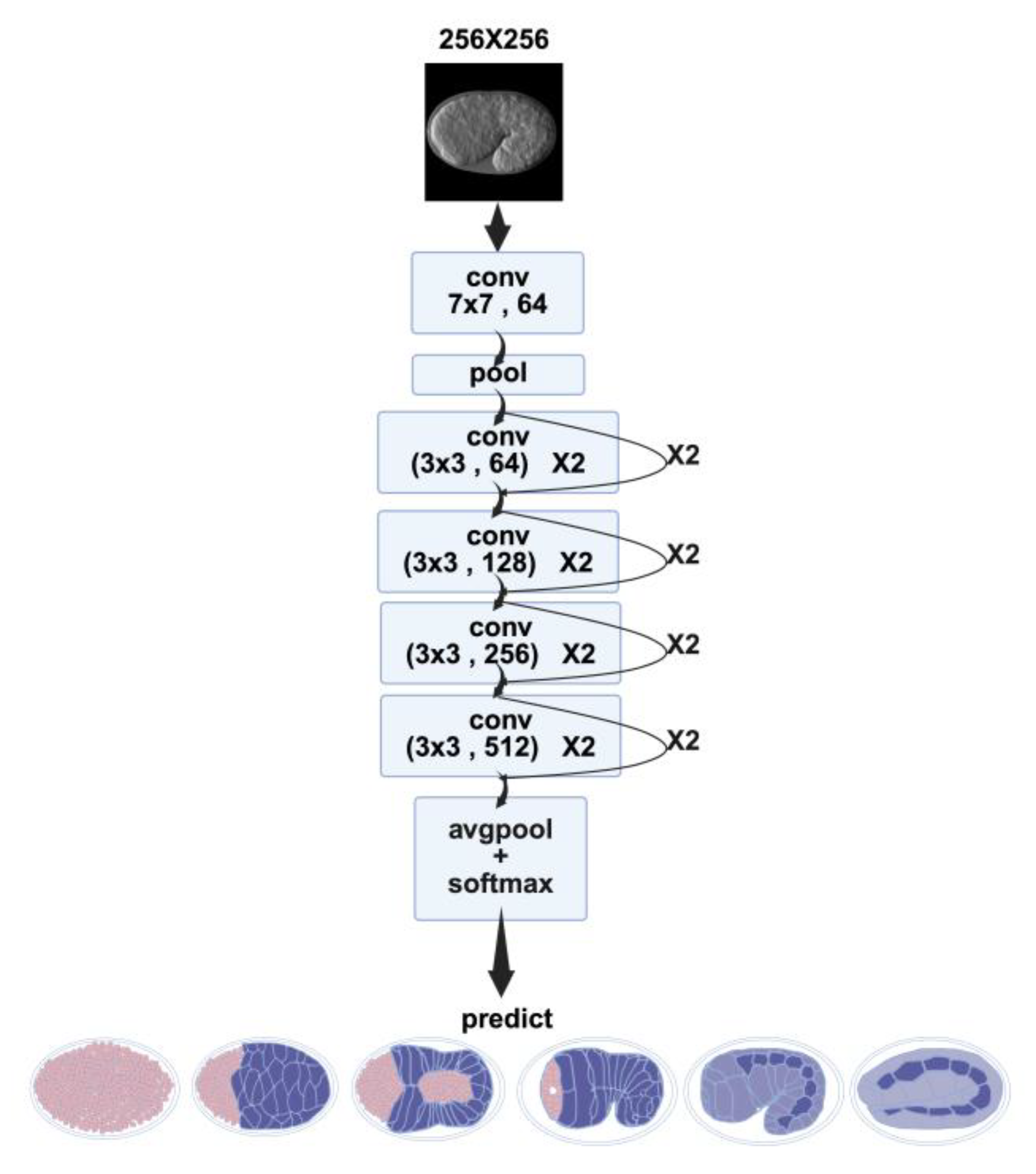

Figure 8.

ResNet architecture. After the convolution operation in the residual blocks, softmax is applied to assign probability values to the images being predicted. Boxes represent different operations; the bottom shows the predicted labels from left to right: “before intercalation”; “dorsal intercalation”; “ventral enclosure”; “rotation”; “1.5-fold”; “2-fold”.

Figure 8.

ResNet architecture. After the convolution operation in the residual blocks, softmax is applied to assign probability values to the images being predicted. Boxes represent different operations; the bottom shows the predicted labels from left to right: “before intercalation”; “dorsal intercalation”; “ventral enclosure”; “rotation”; “1.5-fold”; “2-fold”.

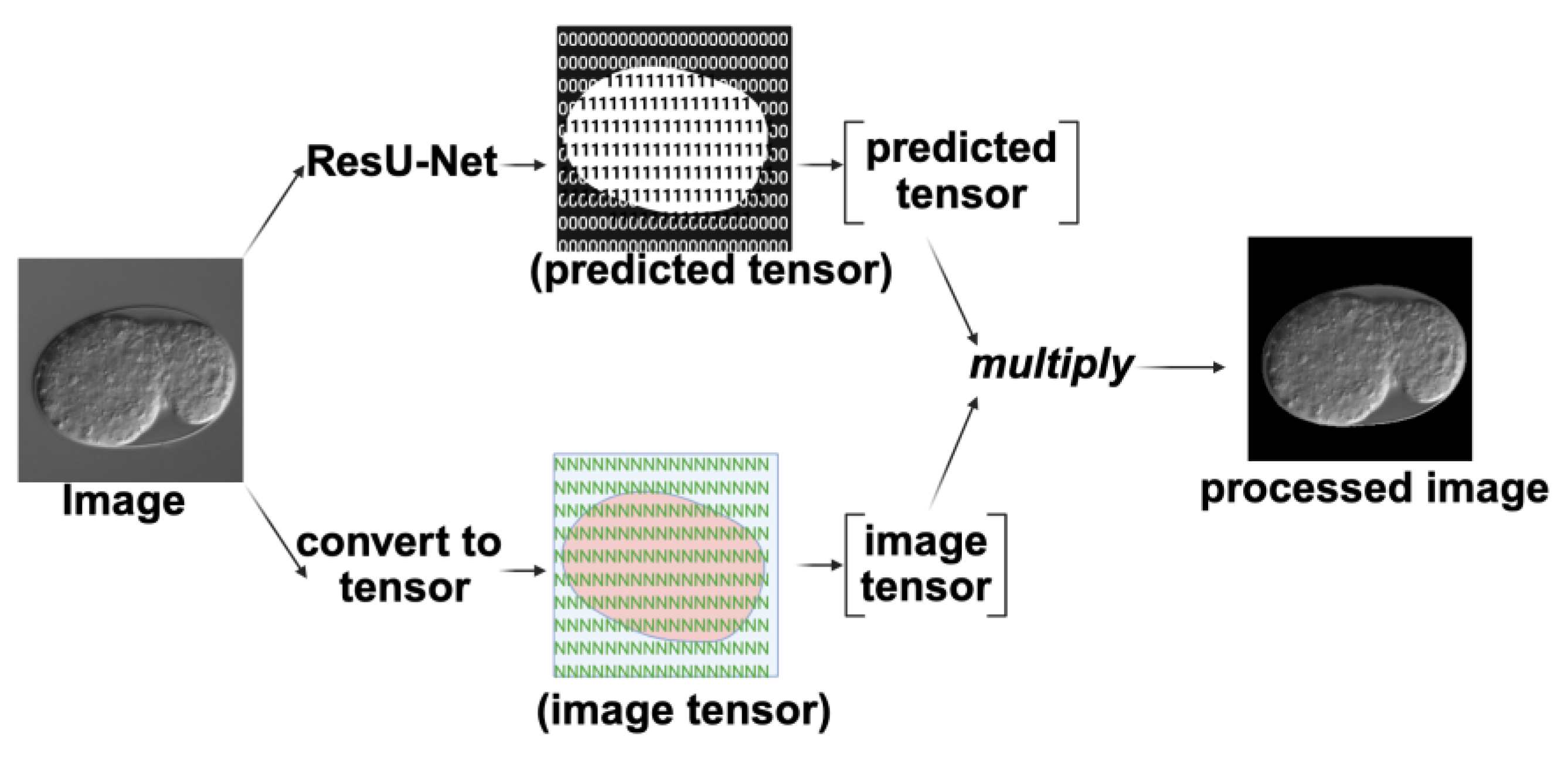

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of using ResU-Net processing to extract the embryonic region in the image. After passing through ResU-Net, a tensor containing only 0 s and 1 s is produced. This predicted tensor is then multiplied by the original image tensor to produce the processed image.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of using ResU-Net processing to extract the embryonic region in the image. After passing through ResU-Net, a tensor containing only 0 s and 1 s is produced. This predicted tensor is then multiplied by the original image tensor to produce the processed image.

Figure 10.

Key temporal analysis experimental workflow. The time-lapse image dataset is first processed by ResU-Net, followed by input into ResNet for embryonic stage prediction. Finally, the predicted timeline results are visualized.

Figure 10.

Key temporal analysis experimental workflow. The time-lapse image dataset is first processed by ResU-Net, followed by input into ResNet for embryonic stage prediction. Finally, the predicted timeline results are visualized.

Table 1.

ResU-Net performance metrics.

Table 1.

ResU-Net performance metrics.

| Metric |

Value |

| True Positive (TP) |

519,293 |

| False Positive (FP) |

14,760 |

| True Negative (TN) |

714,840 |

| False Negative (FN) |

4,483 |

| Sensitivity (TPR) |

99.14% |

| Specificity (TNR) |

97.98% |

| Overall Accuracy |

98.47% |

| Precision (PPV) |

97.24% |

| F1-Score |

98.18% |

| Intersection over Union (IoU) |

96.43% |

Table 2.

ResNet performance metrics.

Table 2.

ResNet performance metrics.

| Metric |

Value |

| Sensitivity (TPR) |

96.87% |

| Specificity (TNR) |

97.98% |

| Overall Accuracy |

96.86% |

| Precision (PPV) |

96.93% |

| F1-Score |

96.83% |

Table 3.

Statistics of the timelines and number of images collected using different interference RNA.

Table 3.

Statistics of the timelines and number of images collected using different interference RNA.

| RNAi |

Number of timelines |

Timeline number with misclassification |

Total images |

Images number with misclassification |

Continuous misclassification |

| control(RNAi) |

16 |

1 |

681 |

0.15% (N=1) |

0 |

| leo-1(RNAi) |

10 |

2 |

541 |

0.37%(N=2) |

0 |

| ajm-1(RNAi) |

10 |

2 |

467 |

0.64%(N=3) |

0 |

| tes-1(RNAi) |

10 |

3 |

457 |

0.66%(N=3) |

0 |

Table 4.

The average time required for each stage of epidermal development.

Table 4.

The average time required for each stage of epidermal development.

| RNAi |

Dorsal intercalation (min) |

Ventral enclosure (min) |

Rotation

(min) |

1.5-fold

(min) |

2-fold

(min) |

| control(RNAi) |

53.75±1.85 |

28.43±2.02 |

15.93±1.38 |

20.93±1.04 |

10.62±0.89 |

| leo-1(RNAi) |

64.50 ± 4.74 *

|

44.50 ± 4.80 **

|

28.50±3.08 **

|

21.00 ± 2.56 |

11.50 ± 1.50 |

| ajm-1(RNAi) |

50.50 ± 4.47 |

25.50 ± 3.37 |

21.00 ± 3.23 |

27.50 ± 2.39 *

|

16.00 ± 1.80 **

|

| tes-1(RNAi) |

49.50 ± 5.46 |

28.50 ± 3.73 |

15.00 ± 2.47 |

21.00 ± 1.25 |

20.50 ± 1.74 ****

|

| * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001 |