Introduction

Chitin is a biopolymer which is remarkably abundant and robust in all thermal, chemical and mechanical terms meaning its properties, e.g., as a sorbent, might be exploited in molecular machines given appropriate periodic processes driven by light or chemical energy can be identified. In addition, redox potentials of metal ions next to and remote from chitin do differ and are considerably influenced by complexation, indicating that

Batteries can be produced by exploiting this fact

Performance of metalloproteins (or more simple catalysts) will be influenced by local presence or absence of chitin

Reaction of M ions on chitin with or at ligands are rapid when there is chitin

Chitin will promote organic oxidations by metal centers, employing O2 or IO3- as oxidants.

Because extent of M adsorption usually differs between water and nearby inundated sediment, simple mechanical processes will transfer metal ions into or out of the sediment to promote chemical or biochemical reactions [

1]

There are implications for the function of metalloproteins remote from and next to chitin, like in dioxygen transport in arthropods, cephalopods, operation of V-dependent oxidation enzymes in fungi or photosynthesis in lichens, plus the chance of a chitin-covered organism to hide from predators once local ligands do change.

Besides working out useful procedures for different tasks (or running into problems), one can conclude that the behavior/activity, possible even the preferred direction of some chemical process at a metalloprotein or more simple metal ion/ligand combination will be changed by presence of chitin. F.e.], one might think of using Co adsorption on chitin combined with amino acids or polyamines for purposes of oxygen-circuit diving (“artificial gills” consisting of chitin modified in this manner and fixed to a ribbon where it is circulated in between O

2-rich open waters and acid-caused release of O

2 next to a CO

2 scrubber). However, electrochemical measurements show rapid oxidation of glycine by air when there is chitin, restoring the low electrochemical potential of Co electrodes with and without chitin while causing substantial corrosion forming CoO at/of the chitin-covered electrode [

1].

One might make machines including mechanical or photochemical processes based on this but also should consider the problems which arose during biological evolution from this: chitin is a very old biopolymer, existing in Volyn mine organisms [

2] long before any extended hard structures (mouthpieces in organisms like

Kimberella or in earliest arthropods, mollusks; legs, fins or other limbs, armour) were made from it or muscles, nerves required to pass it through a water-sediment interface periodically did evolve. This did happen ≤ 555 mio. years ago while the separation age of animals with and without chitin (branching of Ecdysozoa) is estimated at 630 mio. years BP [

3] and even earlier dates hold for splits between (latest common ancestors of) fungi (also containing chitin) and of animals. Though chitin obviously was and is a useful material, animals had to “learn” how to cope with these chemical features of chitin before employing it (or abandon it almost completely which happened in ancestors of vertebrates/chordates other than amphioxus [

4]) in a larger scale.

Concerning technical applications, we of course can make ready use of these properties and the large-scale availability and non-toxicity of chitin – once we did fully explore them. This is very much like historic appreciation of semiconductor properties of Si or certain compounds, making ferromegnets from uncommon materials/elements or employing the repulsive electrostatic potential within heavy atomic nuclei. Besides adsorption to chitin in its dissolved state (suspended in a Li salt solution in carboxamide solvents such as DMF [

5,

6]), where redox reactions of attached ions also can be studied along a broad range of potentials [

5], similar experiments are feasible using solid chitin. This can be either native chitin (represented by dead daphnia or grasshoppers, sandhoppers, exuviae, dragonfly wings and the like) or a purified material derived from shrimp peeling. Native chitin contains very high levels of proteins and polyphenols [

7] which effect cross-linking of the chitin strands but might also intercept metal ions including Fe, V, or Pu [

8]. Accordingly, one would expect that most of the original interior structure is lost during purification, such as the plywood-like arrangement of the chitin strands. The density of purified chitin is 1.37 g/cm

3 (own measurements). Notwithstanding this, extraction of both polyphenols and proteins/peptides would likely leave behind voids in the structure of chitin. Metal ions known to diffuse slowly from the surface into bulk material [

9,

10], sometimes (Al, Co) even forming diffusion fronts [

9], giving proof of some empty inner spaces if not channels like in C nanotubes or ReO

3 to exist in the purified chitin. Moreover, dissolution of chitin by DMF/Li

+ occurs in a very smooth manner removing planar layers one by one, again indicating a kind of sheet structure which is pre-formed in native chitin [

9] and becomes more accessible to solvents, ions and other reactants when proteins and phenols were removed previously.

One would expect that metal ions would now, besides

ion migration perpendicular to the chitin surface (into either direction, possibly

be expelled by other chemical entities changing shape or size due to photochemistry (e.g., azobenzenes) or reduction (many different metal ions) whereas others would

escape spatial confinement (also present in the stable position of metal ion complexation at chitin or equivalent solvents such as N-acetylethanol amine).

Accordingly, the behavior of ions must be understood by electrochemical measurements indicating changes a) next to chitin (where ions may be removed from layers accessible to electrochemistry into either direction) and b) in N-acetyl ethanolamine solvent (indicating relative solvation compared with water or methanol). The voltage measured in between a bare electrode and one covered by chitin gives information on extent and dynamics of adsorption of the corresponding ions while introducing some driver which accepts either electrons or undergoes photochemical activation to move other components now under the chitin surface. Due to our vast experience and because it is much smaller and hence more ready to get inside the chitin structure, we chose europium (Eu) as a photoactvated driver species, rather than bulky organics like azobenzenes. Of course, one might mix a solution of chitin in DMF/Li+ with one containing azobenzene or the like and precipitate the system by simply adding water or ether trying to get an assembly which includes the driver species. Yet the product reconstituted by precipitation is unlikely still to have the channels required for the said function.

Catalytic activities found by us in different electrode-chitin-organic matter systems show some degradation of organics next to chitin [

1]. This does pose several interesting questions, including that of how arthropods, lichens, … (could start to) deal with an oxidizing atmosphere (O

2 levels/local redox potentials considerably while not steadily increasing in late Ediacarian and early Cambrian times). Notably, chitin was present in biota for quite a while already [

2] but arthropods did evolve only in Cambrian. We are convinced that a possible positive selection value of some material (biopolymer) or (metabolic) process can only be estimated if you possess some solid, comprehensive knowledge about its properties. As for chitin, it is not just a very robust material but likewise a strong sorbent. Since release takes place at pH ≤ 3 (i.e., in stomach) all animals feeding on arthropods or lichens will be exposed to adsorbed metal ions or complexes. Hence one must know how much is bound and which are dynamic equilibria (how fast does adsorption take place, do ions stay at the original place of adsorption and is there significant desorption in less acidic conditions?). If there are diurnal migrations of arthropods (e.g., zooplankton) between sites exceeding and missing the lower limit of adsorption level (usually, about 1 nMol/l or less) or mechanical agitation at the water/sediment interface [

1,

9] or even photochemical processes removing hitherto adsorbed ions or changing ligands which then get involved in desorption, a desorption which occurs on a timescale of about 12 hours or shorter will translate into transport. How fast, then, is adsorption?

Materials and Methods

The setting comprises chitin and solvent [water, with added CH

3OH or ethanolamine], ligands [selected according to the metal ion, both inorganic [thiourea, SCN

-, iodate, carbonate] and organic [e.g., HCOO

-, glycine, ethylenediamine, or caffeinate], and a conductive salt). Usually NaClO

4 is employed for this purpose; in non-polar media (esters, toluene) which are distinguished by very peculiar photochemical reactions mediated by Eu(III) quaternary phosphonium salts like PBu

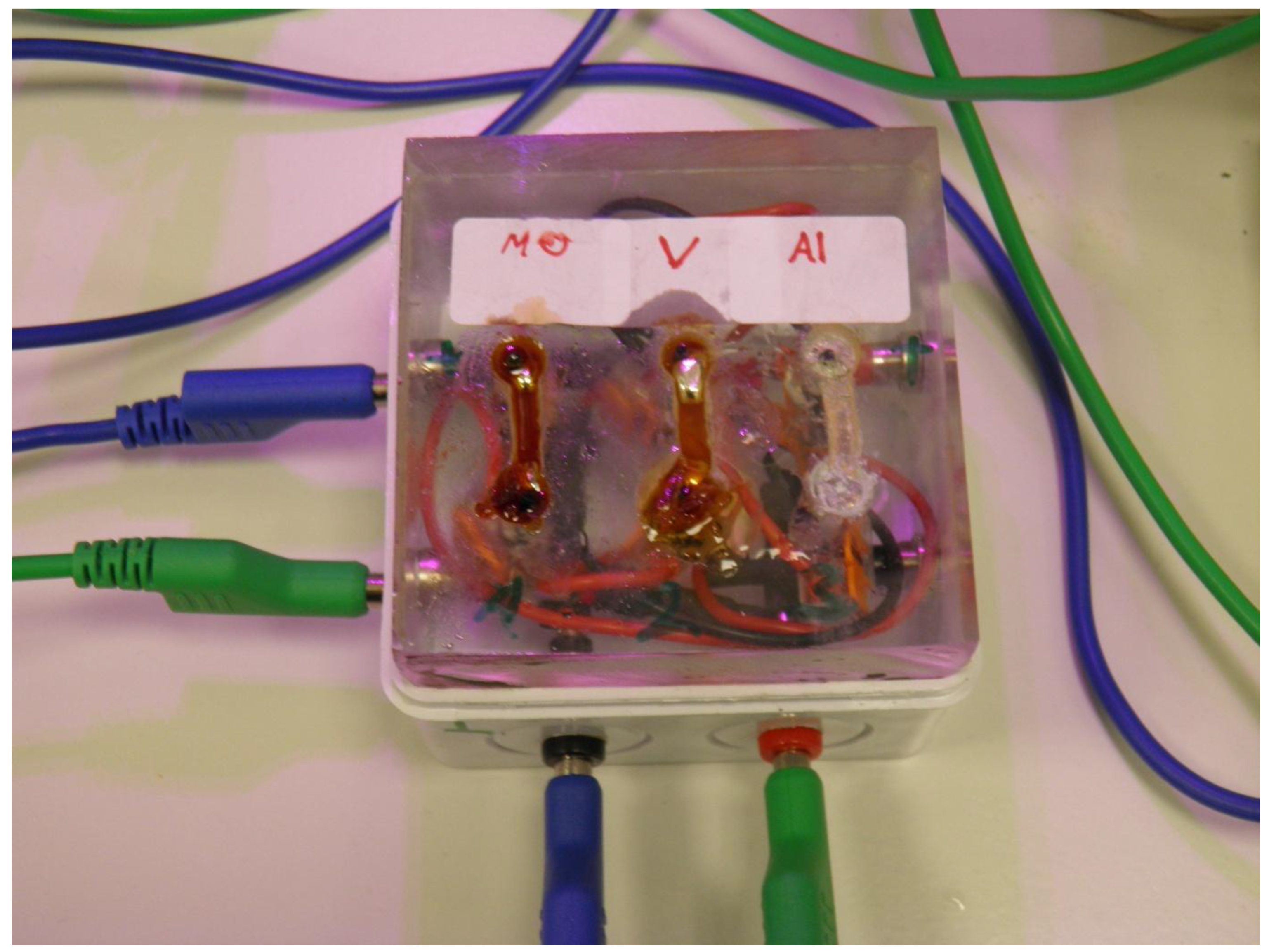

4Br are used instead (quaternary ammonium salts undergo photooxidation themselves), using liquid-metal alloy electrodes. The equilibrium and present state of adsorption can be characterized by electrochemical methods using a very simple setup being a 2D-system (

Figure 1):

Its CV equivalent comes with a floating device keeping chitin next to the working electrode.

Figure 2.

a plastic bubble film floating in the solvent (H2O/THF/acetic acid) does keep chitin around the working electrode (Pt sheet connected to V_Ga liquid alloy). Electrochemical results obtained with this setup are shown below.

Figure 2.

a plastic bubble film floating in the solvent (H2O/THF/acetic acid) does keep chitin around the working electrode (Pt sheet connected to V_Ga liquid alloy). Electrochemical results obtained with this setup are shown below.

Table 1.

list of chemicals and devices.

Table 1.

list of chemicals and devices.

| Kinds of material/equipment |

Name, substance |

supplier |

Remarks, purpose |

| devices |

Channel-electrode system |

Home-built |

Recording of both voltage and current in between bare and chitin-covered electrode (4 cm apart); conductive salts, Eu(III), ligands, and photoreductants placed in channel which can be illuminated. |

| |

Cyclic voltammeter |

PalmSens |

Mobile microdevice, directly attached to laptop |

| Metals, compounds |

|

|

|

| |

NaClO4 monohydrate |

|

Conductive salt |

| |

PBu4Cl |

|

Photostable conductive salt |

| |

V metal |

|

|

| |

V_Ga alloy |

|

Prepared from elements. Dissolves in Eu photooxidation conditions when there is chitin. |

| |

VCl3

|

Sigma-Aldrich |

Solid anhydrous salt |

| |

(VO)SO4

|

Riedel-deHaen |

|

| |

Ga |

Goodfellow |

|

| |

Ga_In alloy |

|

Liquid eutectic mixture |

| |

Eu(III) trifluoromethanesulfonate |

|

|

| |

Mo sheet |

|

|

| |

Mo_Ga alloy |

|

Prepared from elements |

| |

Ni chloride |

|

Dark olive-green adduct with chitin; Ni gets removed when irradiated with Eu(III)/H atom donor |

| Solvents, biopolymers, ligands, other materials |

|

|

|

| |

Chitin, purified |

Merck |

From shrimp Pandalus borealis. Adsorbs metal ions in kind of cavity reducing the number of consecutive |

| |

ethanolamine |

|

Gets dark red when exposed to Eu/light with both Mo_Ga and V_Ga. |

| |

fructose |

|

Photoreductant when combined with Mo |

| |

Bis-diphenylphosphinoethane |

|

dppe. Apparently does not bind to Mo when there is chitin |

Metal ion dynamics on a chitin interface were studied by electrochemical methods, including cyclic voltammetry in water and other aq. media comparing bare- and chitin-covered metal electrodes.

The purified chitin does contain some metals as a background (Fe, Al, Ti about 10 – 20 µg/g each, Cu and Zn at 1 – 2 ppm). Yet, these do not produce measurable electrochemical signals even in dissolved state. Apparently, metal ions switch to electrochemically silent deep sites in chitin during longer periods of time. This would be expected to happen given the model outlined that metal ions may be shifted from the channels where they are physically and electronically connected with an electrode.

Results and Discussion

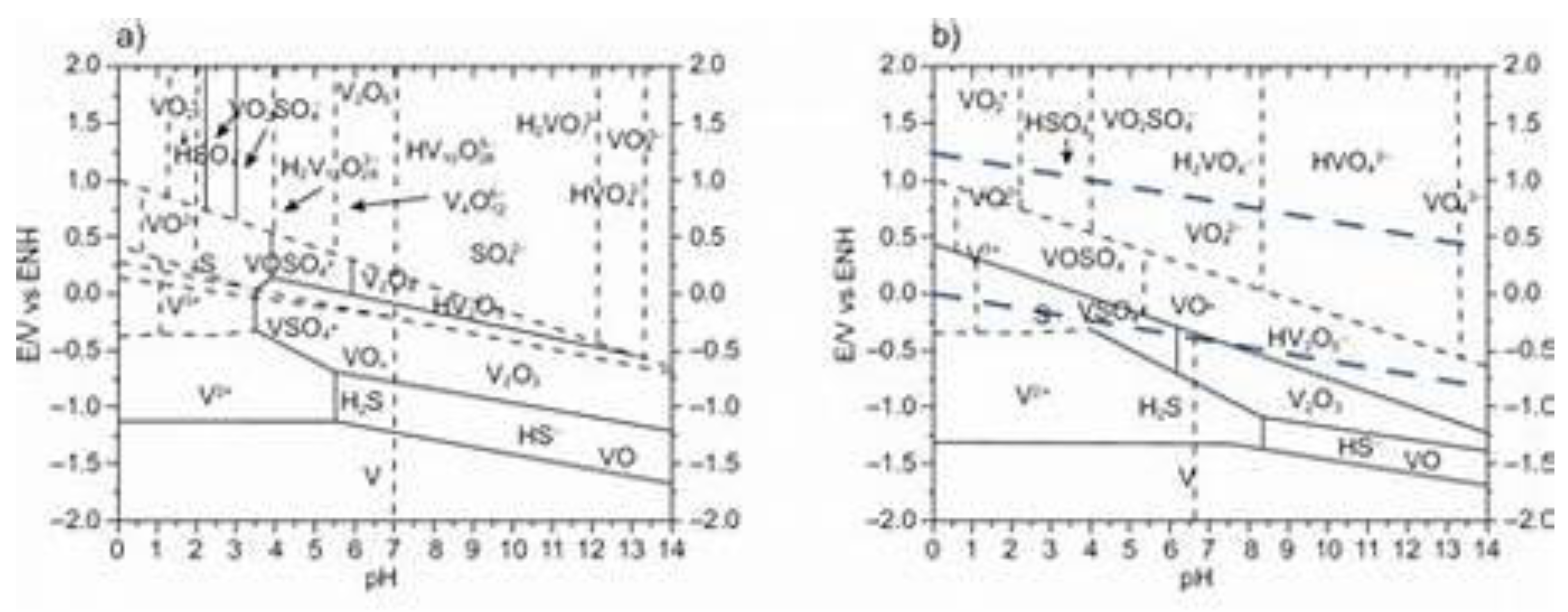

The isoelectric point of chitin is pH 3.5 (i.e., close to the lower limit of metal adsorption by chitin) indicating negative surface charge (corroborated by measurement of zeta potentials [

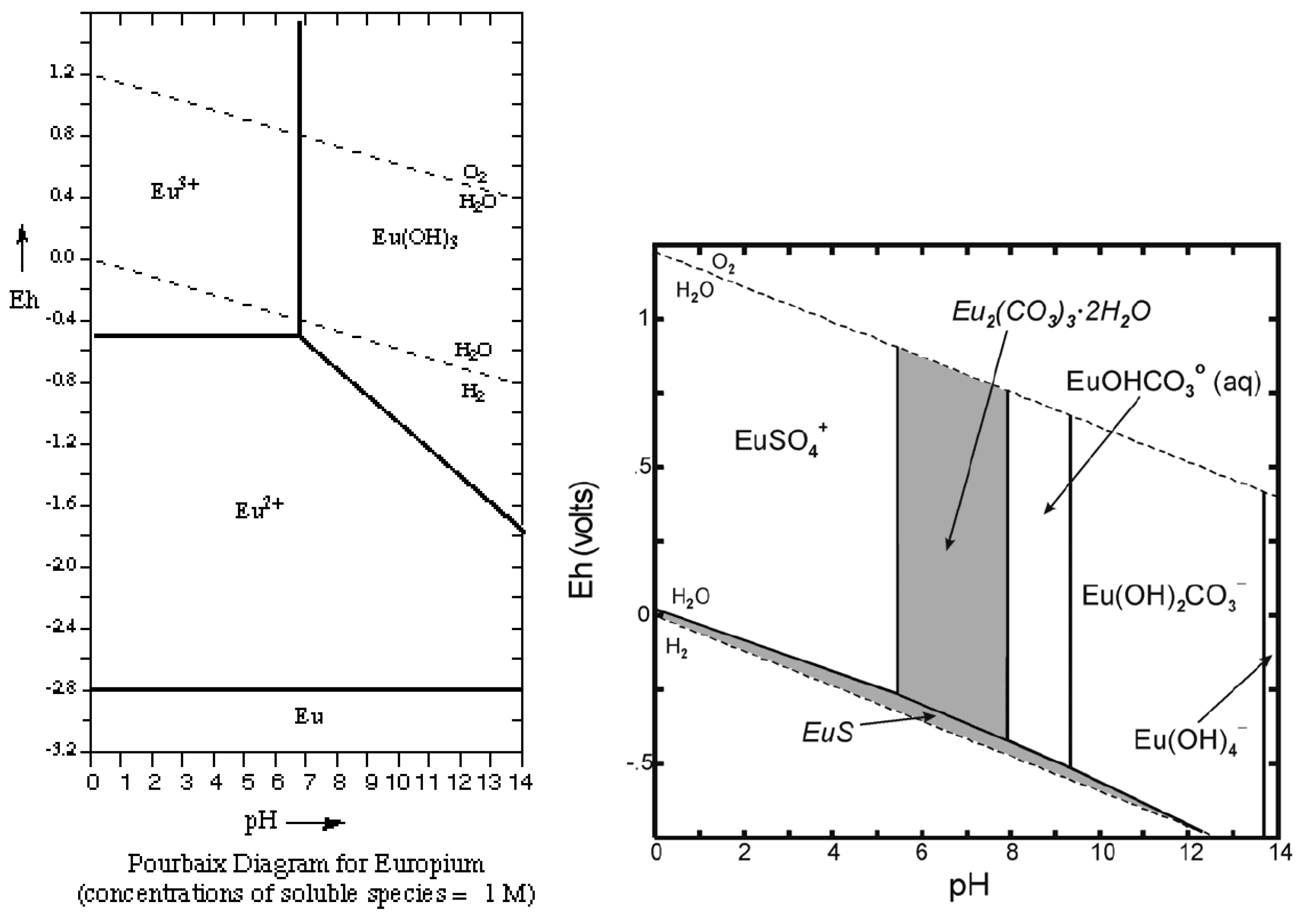

11]). Note that potentials calculated here are given vs. NHE (lower broken line at pH 0) while our measurements refer to SCE, that is, NHE + 0.241 V.

The minimum potential reached in the light-exposed alkaline (due to presence of ethanol amine) solution/chitin suspension containing both Eu and V is -0.685 V vs. SCE ≡ -0.444 V vs. NHE. This corresponds to the stability region of Eu(OH)3 or (after absorption of CO2) of [Eu(OH)2(CO3)]- and of V(III) oxides, respectively. However, this work was not done with neat V metal but with a liquid V_Ga alloy, meaning V activity in the alloy (i.e., that of the reduced state) is substantially smaller than 1. For comparison, both CVs are shown.

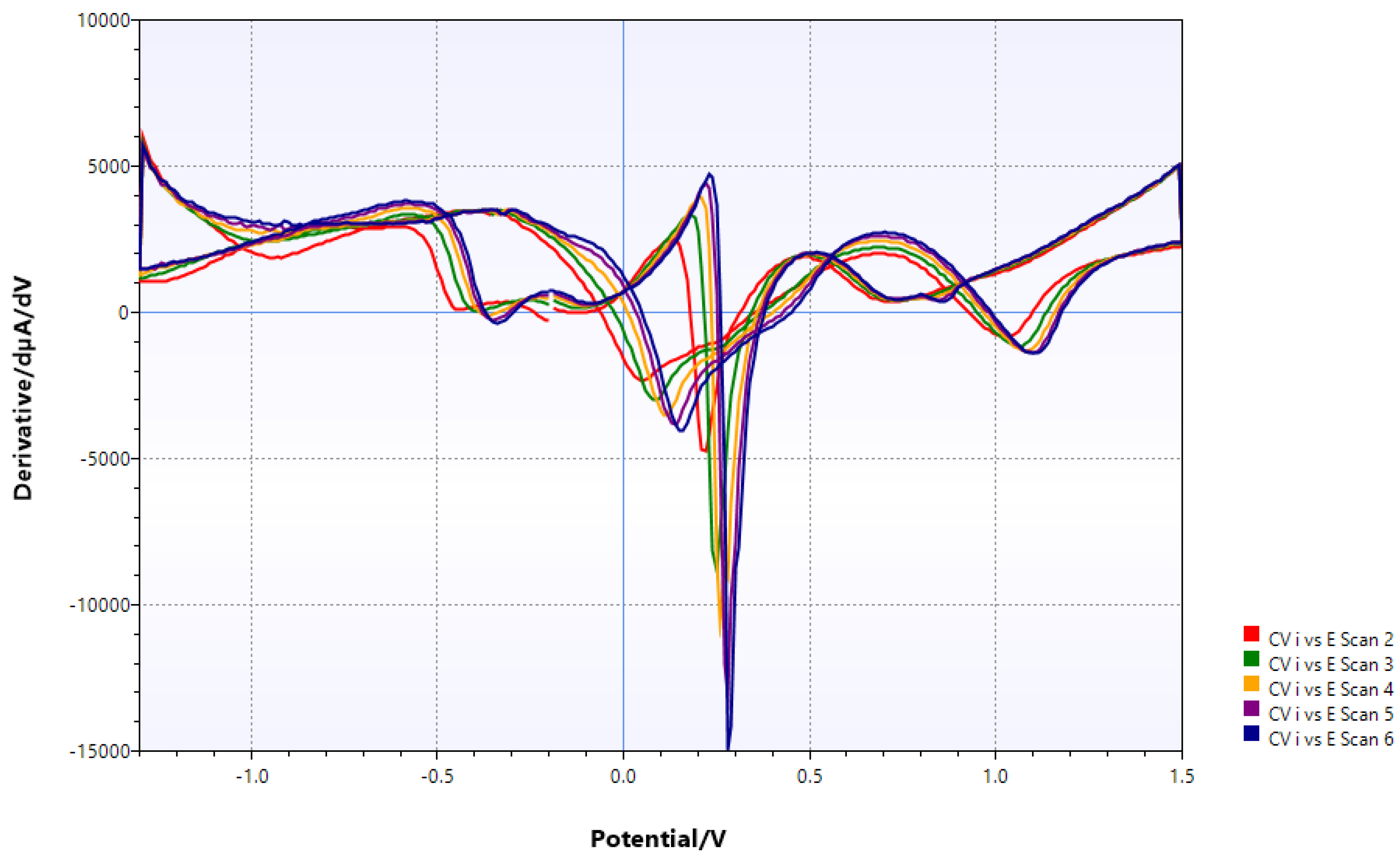

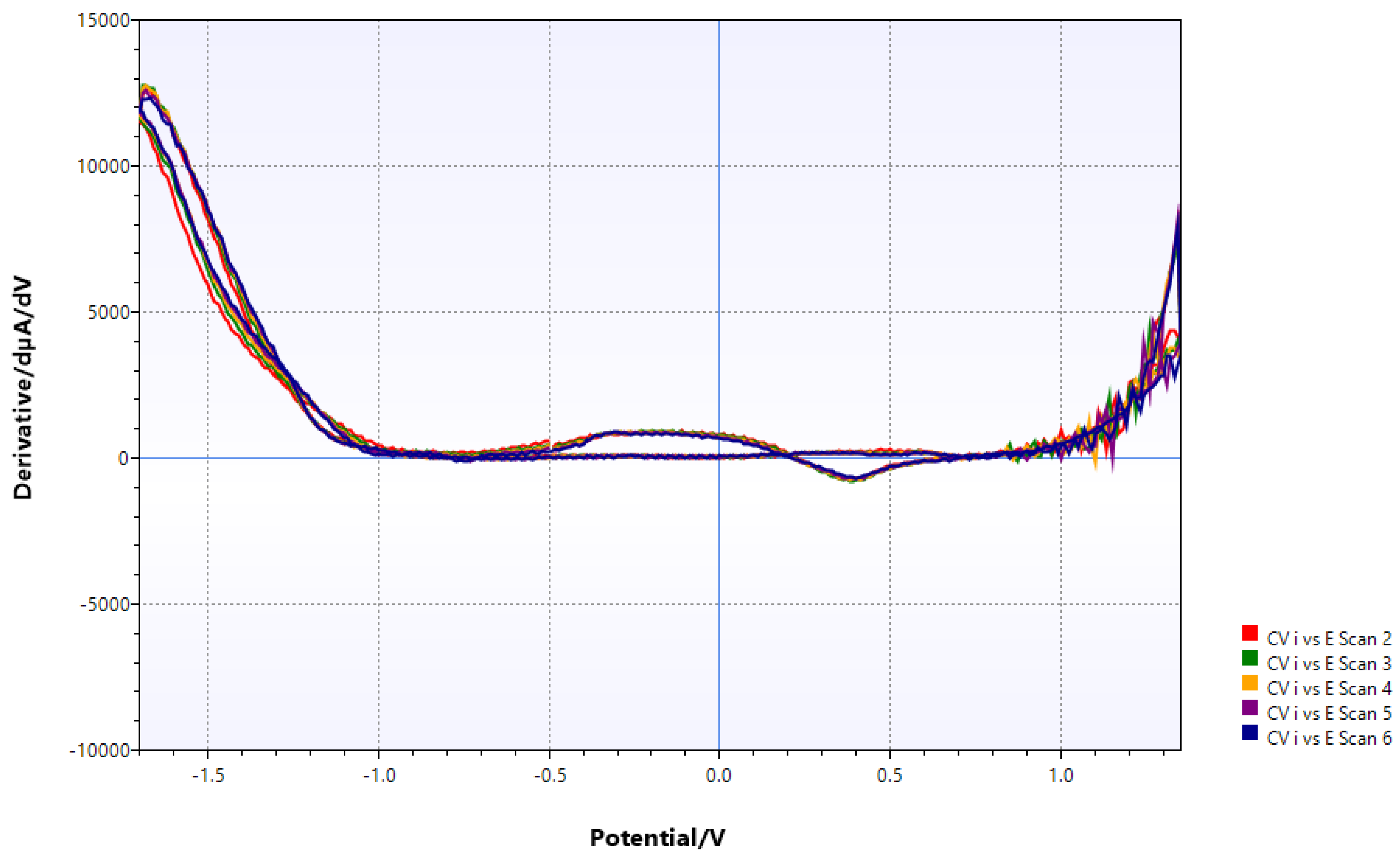

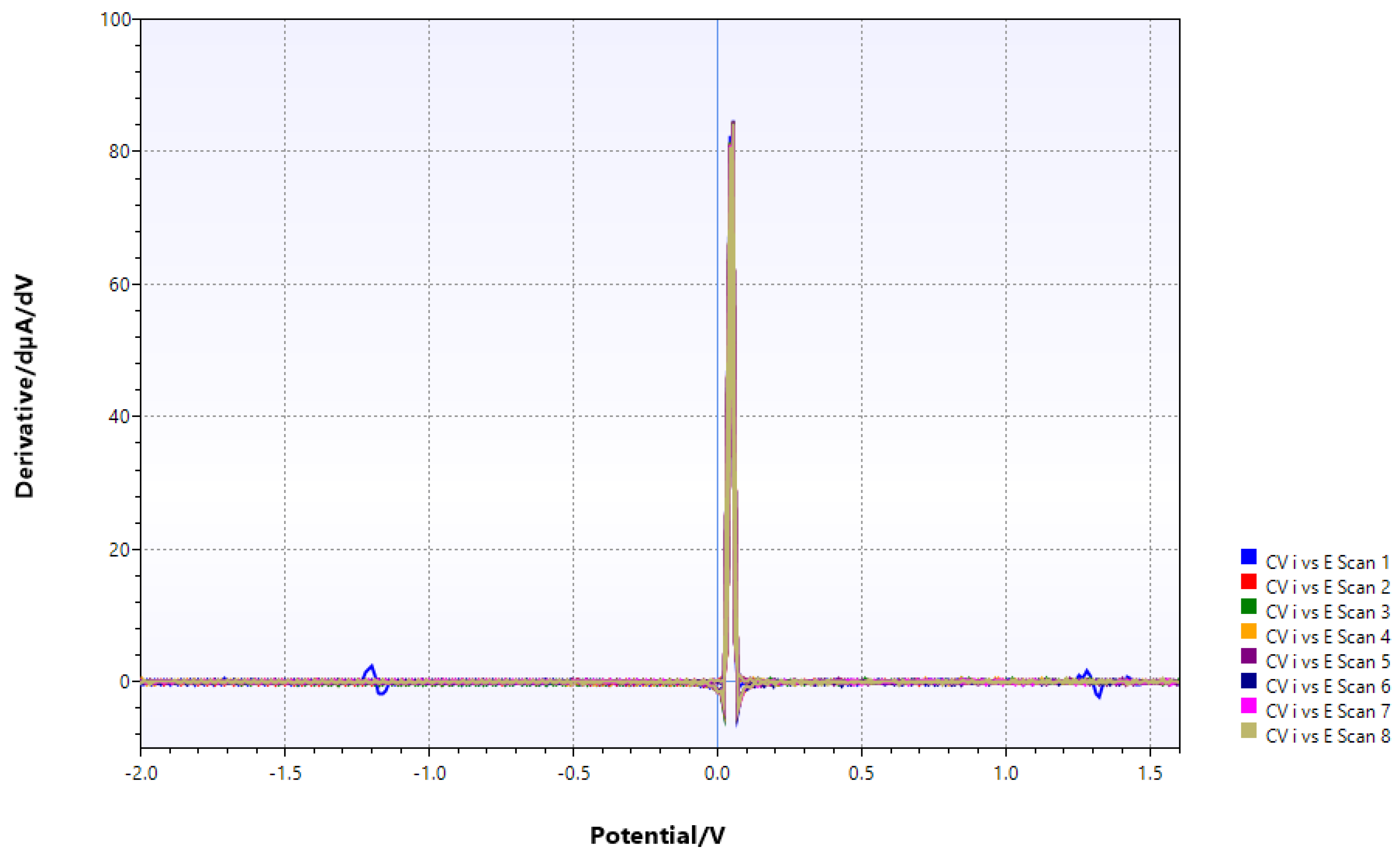

Figure 3.

CV of V(IV) oxysulfate in aq. methanol/DMF (1st deriv.). All expected redox transitions (cp. Pourbaix diagram of V).

Figure 3.

CV of V(IV) oxysulfate in aq. methanol/DMF (1st deriv.). All expected redox transitions (cp. Pourbaix diagram of V).

Figure 4.

Pourbaix diagrams of V with sulfur compounds. The typical bright-red, photoactive [VS4]3- and patronite (polysulfde VS4) do not represent thermodynamically stable species are visible.

Figure 4.

Pourbaix diagrams of V with sulfur compounds. The typical bright-red, photoactive [VS4]3- and patronite (polysulfde VS4) do not represent thermodynamically stable species are visible.

Eu

2+ does rapidly reduce V(III) (or trivalent Fe, Cr) when there are bridging ligands, especially in acidic conditions [

12].

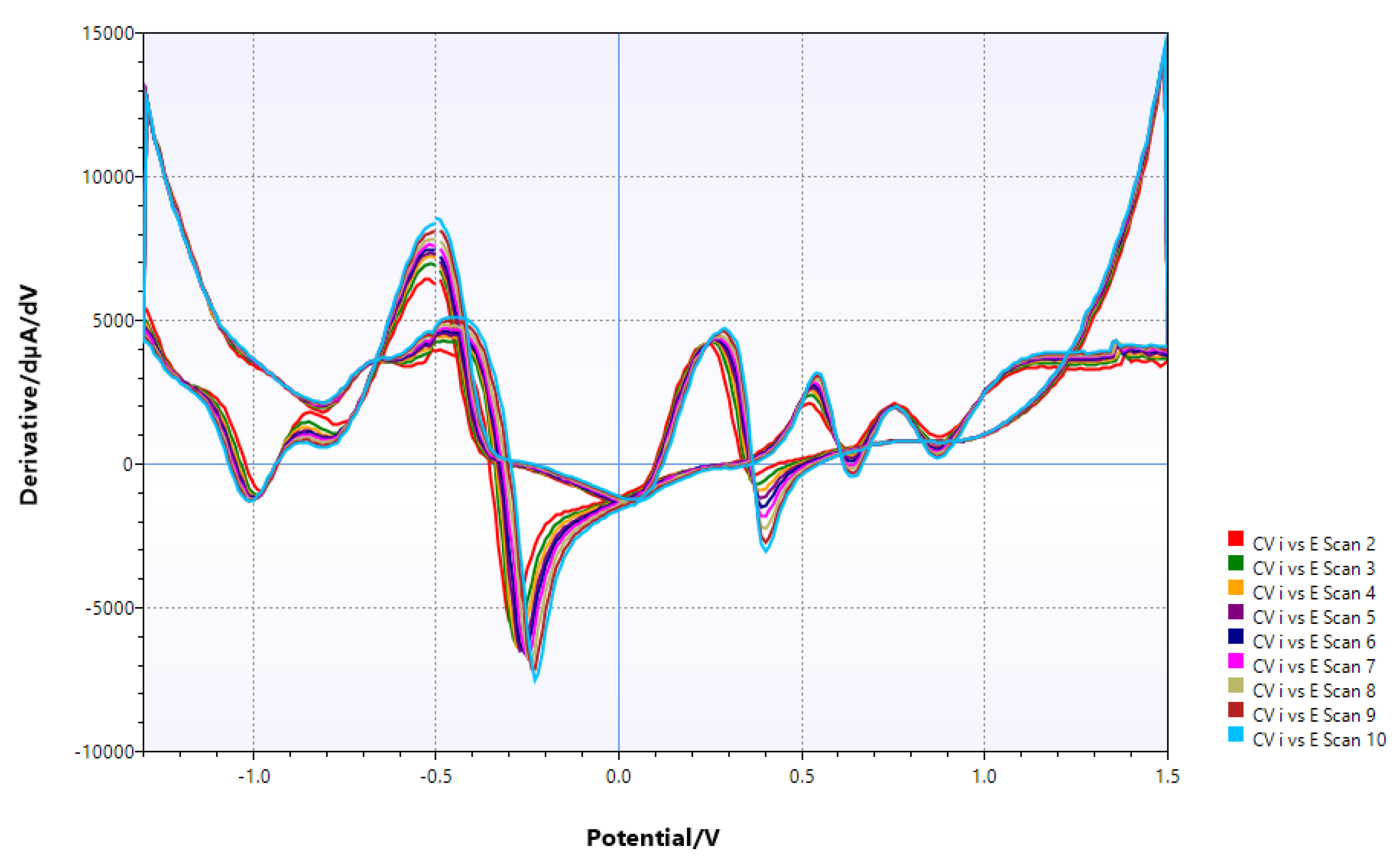

Figure 5.

Addition of Eu(III) and caffeic acid + DMF; not yet photolyzed (caffeic acid was employed as a catechol ligand for inducing secondary redox reactions of small molecules with V(II) [

13]). The number of redox transitions does suggest there are both free V and caffeinate complex species.

Figure 5.

Addition of Eu(III) and caffeic acid + DMF; not yet photolyzed (caffeic acid was employed as a catechol ligand for inducing secondary redox reactions of small molecules with V(II) [

13]). The number of redox transitions does suggest there are both free V and caffeinate complex species.

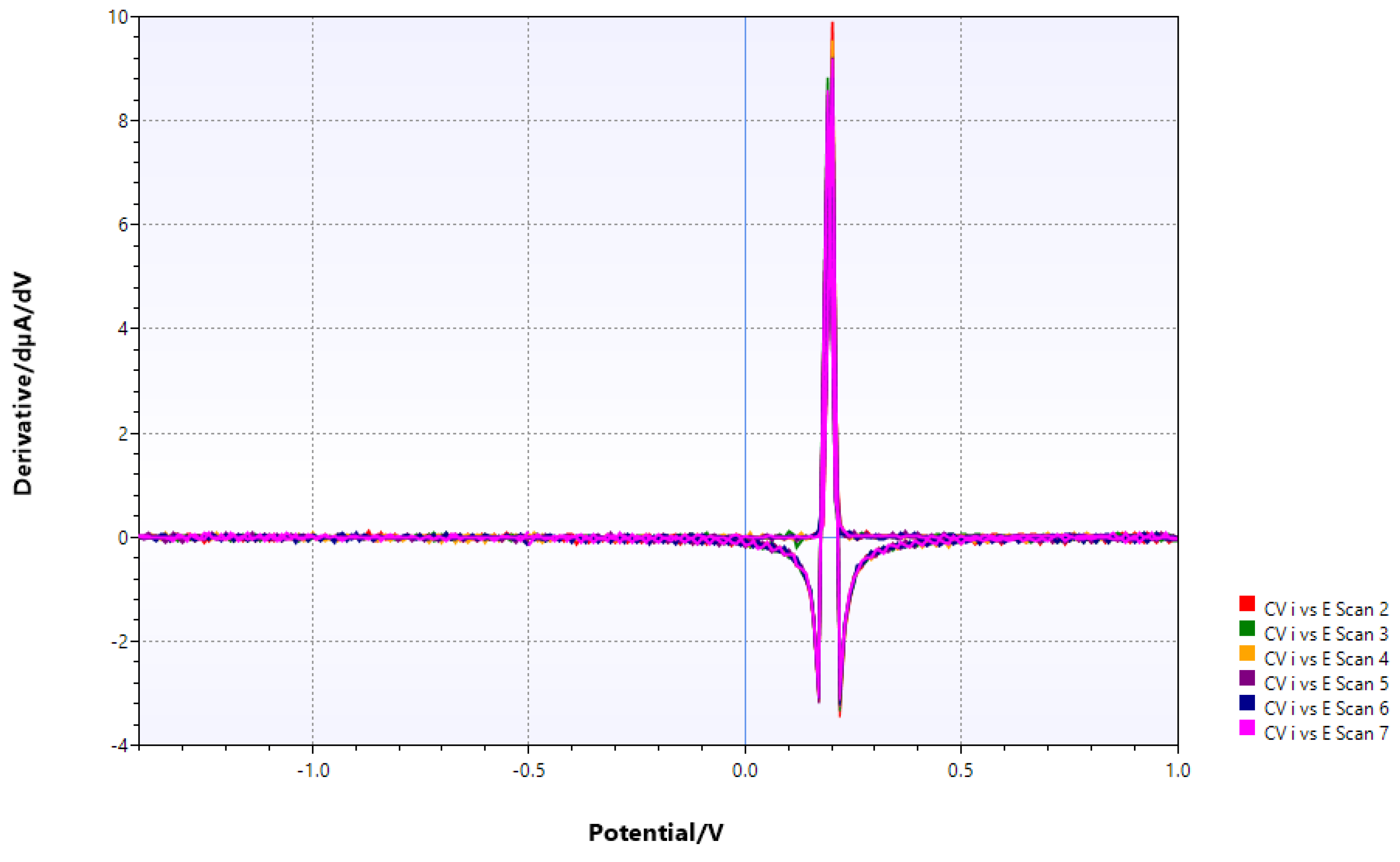

Figure 6.

V metal/VCl3 with chitin (added just 5 min before); most transitions seen before and in the Pourbaix diagram are suppressed.

Figure 6.

V metal/VCl3 with chitin (added just 5 min before); most transitions seen before and in the Pourbaix diagram are suppressed.

Figure 7.

16 hours after chitin addition: minimal shift of potential, probably due to migration of V ions on chitin surface.

Figure 7.

16 hours after chitin addition: minimal shift of potential, probably due to migration of V ions on chitin surface.

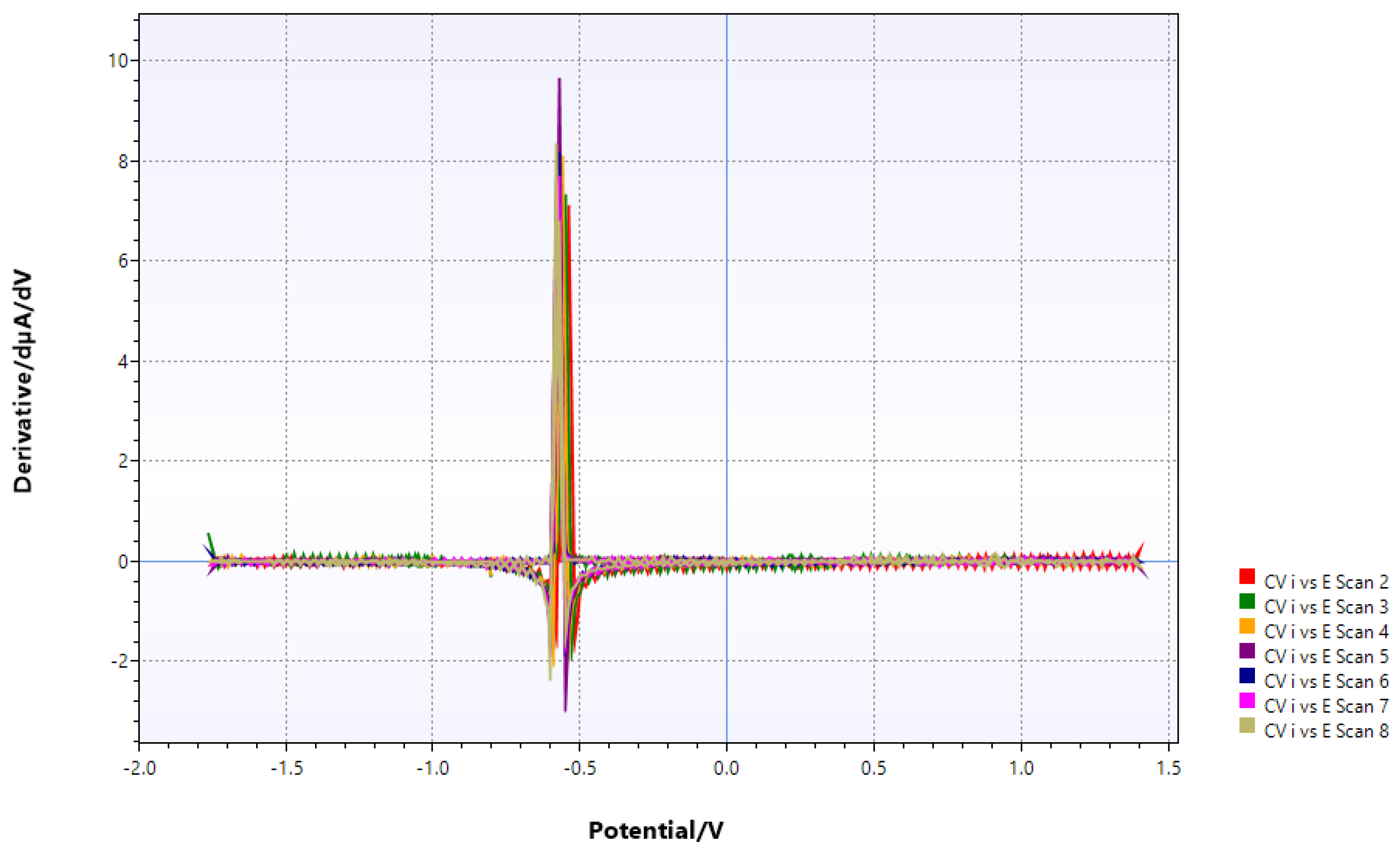

Figure 8.

V_Ga/VCl3 with chitin, Eu(III) and ethanolamine added, prior to photolysis. Solvent addition causes substantial negative potential shift.

Figure 8.

V_Ga/VCl3 with chitin, Eu(III) and ethanolamine added, prior to photolysis. Solvent addition causes substantial negative potential shift.

Table 2.

redox transitions before and after chitin addition (all potentials are vs. SCE and first derivatives).

Table 2.

redox transitions before and after chitin addition (all potentials are vs. SCE and first derivatives).

| metal |

Ligand(s) |

Potential [V] |

remarks |

+ chitin |

Potential [V] |

Difference [mV] |

| V |

chloride |

0.43 |

|

|

+0.19 (only trans., after 24 h) |

-240 |

| |

|

-0.19/-0.04 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

-1.22/-1.14 |

Metal deposition |

|

|

|

| V_Ga |

Cl- |

|

|

|

+0.236 just after chitin addition; +0.31 after 24 hours |

|

| |

+ ethanol amine |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

No shift against |

Adding Eu(III) |

-0.555 dark |

|

| |

|

|

Steady decrease of single redox transition, current does also decrease upon illumination. Solution, chitin stay colorless |

|

-0.685 > 5 h illumination, -1.01 weak, substantial noise (probably photogenerated radicals) |

|

| |

|

|

Complete dissolution of V_Ga under chitin, Eu, light within 3 d |

|

-0.52 (equal to Ga/chitin) |

|

| |

Cl- |

Only measured after chitin addition (right) |

Separation into two phases, no more metal deposition from aq. solution |

+ caffeic acid |

+0.173 (only signal) |

-17 → caffeinatocomplex marginally stable on chitin |

| |

|

See above |

Eu-based redox transitions completely suppressed |

Adding Eu triflate, dark |

+0.20 |

+27 (intermixing of different M-centered transitions) |

| |

|

|

Rapid e transfer Corg→ Eu → V(chitin)

|

70 h illumination |

+0.25 |

|

| Ga |

nitrate |

-1.50 |

|

|

-1.44 (24 h after chitin add.) |

+60 |

| |

|

-1.44 |

|

|

-1.23 |

|

| |

|

-0.63 positive |

Metal deposition signal? |

|

-0.87 negative |

|

| |

|

+0.09 unstable |

|

|

-0.53 negative |

|

| |

|

+0.62→ 0.71 upon repeated CV scans |

|

|

-0.10 short-lived upon repeated CV scans |

|

| Mo |

acetate |

-0.048 |

THF/acetic acid added for obtaining homogeneous solution |

No measurement omitting dppe |

|

|

| |

+ dppe |

0.051 |

Single signal |

|

0.061, after 12 d: +0.095 |

|

| Ni |

chloride |

-0.77 |

|

|

-0.73 |

+40 |

| |

|

0.16 |

|

|

-0.475 positive |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

-0.25→ -0.21 negative |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

+0.044 |

-116? |

| |

|

|

|

|

+0.51 |

|

| |

Nitrate/glycine |

|

Eu added, very brief photolysis (10 min) |

|

-0.71 |

|

| |

|

|

|

Peak due to Ni not Eu |

-0.48 positive |

|

| |

|

|

|

Peak due to Ni not Eu |

-0.214 negative |

|

| |

|

|

|

Peak due to Ni not Eu |

+0.047 |

|

| |

|

|

|

Peak due to Ni not Eu |

0.51 |

|

| |

|

|

Eu added, photolysis for 24 h; |

Ni is removed from chitin surface (color) |

-0.98 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

-0.83 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

+0.12 |

|

| |

|

|

|

New Ni complex? |

0.61 |

|

Table 3.

ion radii (Shannon radii):.

Table 3.

ion radii (Shannon radii):.

| metal |

+II |

+III |

+IV |

+V |

remarks |

| La |

|

About 130 |

|

|

|

| Ce |

|

130 |

111 (CN = 8) |

|

|

| Eu |

139 (CN = 8)

144 (CN = 9) |

120.6 (CN = 8)

126 (CN = 9) |

|

|

|

| Ga |

|

61 – 76 |

|

|

|

| In |

|

94 (CN = 6) |

|

|

|

| V |

93 |

78 |

72 |

≤ 68 (50 for CN = 4) |

VO2+ (blue) exists next to chitin if there is no ethanolamine |

| Mo |

|

83 |

79 |

|

|

| Ni |

63 (square-planar), 69 (tetrahedral) |

|

|

|

|

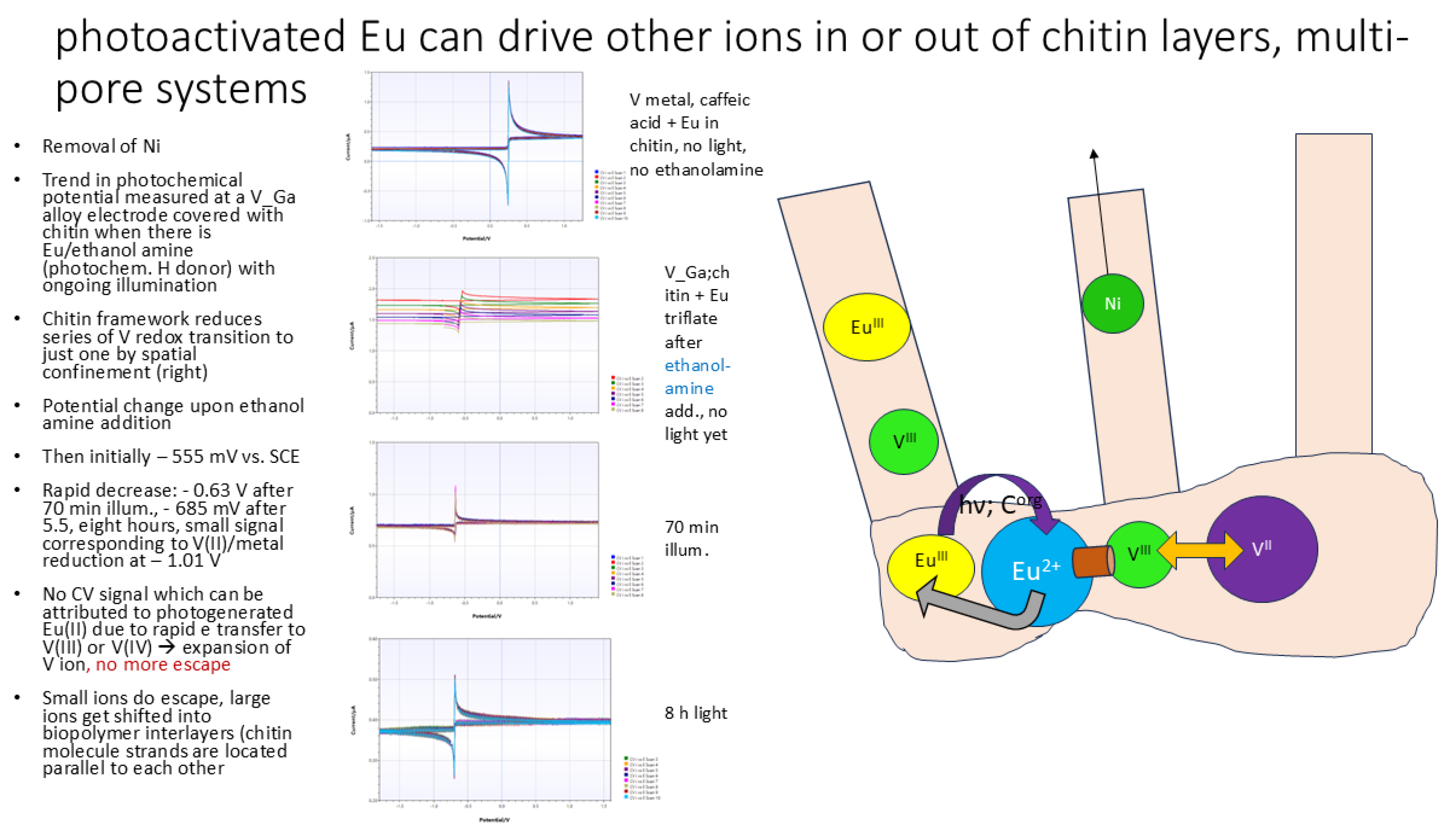

This list does constrain the size of the “channels” provided by the chitin natural arrangement: Ni(II) does get out, and when there is no ethanolamine, no photochemical up-sizing of Eu ions will take place. In addition, ethanol amine does substantially decrease the potential value of the only remaining redox transition, possibly switching to another redox transition with vanadium.

Upon illumination/photodehydrogenation of some substrate, Eu ions “swell” by some 18 pm in radius. The change is similar with V

II/III, meaning that a possible bridging ligand will move back and forth by some 15 – 20 pm. Thus, V is removed from the channel parallel to the surface, unlikely to return to the ion channel for escape. The Eu ion or Eu-ligand bridge-V system acts as a kind of piston which moves solvate- and other molecules likewise parallel to the surface. In addition, adsorbed ions slowly migrating deeper into the bulk chitin [

9] might be brought into close contact with local donor sites (OH, acetamide, carboxylate or NH

2 if chitin underwent some oxidation or hydrolysis respectively). Catechols and similar polyphenols are crucial in crosslinking chitin molecules [

7] but not obviously involved electrochemistry; however, various catechols can reduce N

2, CN

- or CO when combined with V(II) and some Brönsted base in either water or CH

3OH [

13]. With such complexes as well as V-nitrogenase [

14] CO as a substrate affords C

>1 products like in Fischer-Tropsch reactions, mainly C

2H

4, minor C

2H

6 and C

3H

8 [

15]. By simply adding chitin, the C

org→Eu→V redox cascade becomes a molecular machine relocating both metal ions and ligands, organic molecules by periodic, photodriven expansion and re-contraction of metal ions starting with excited Eu(III).

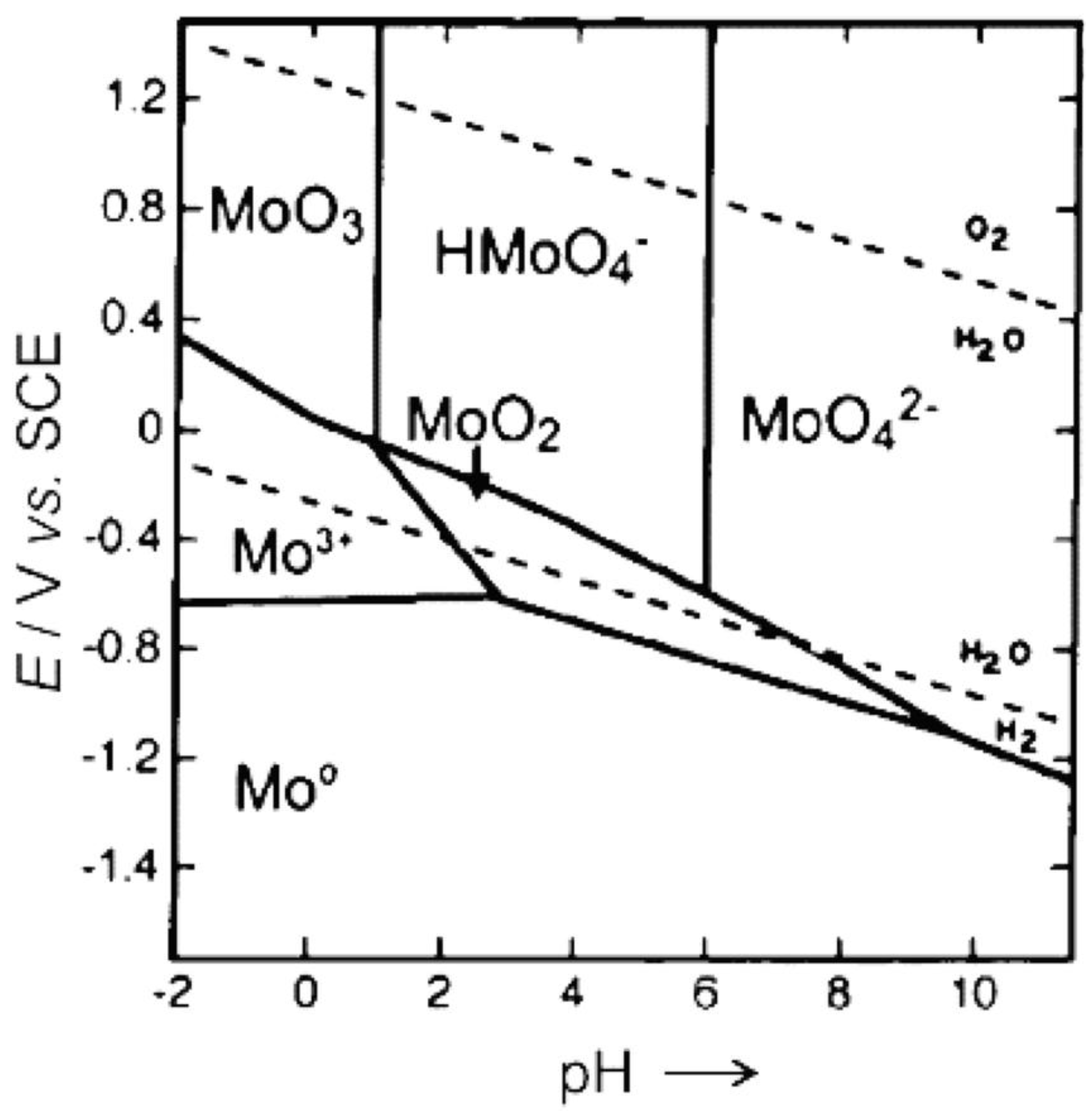

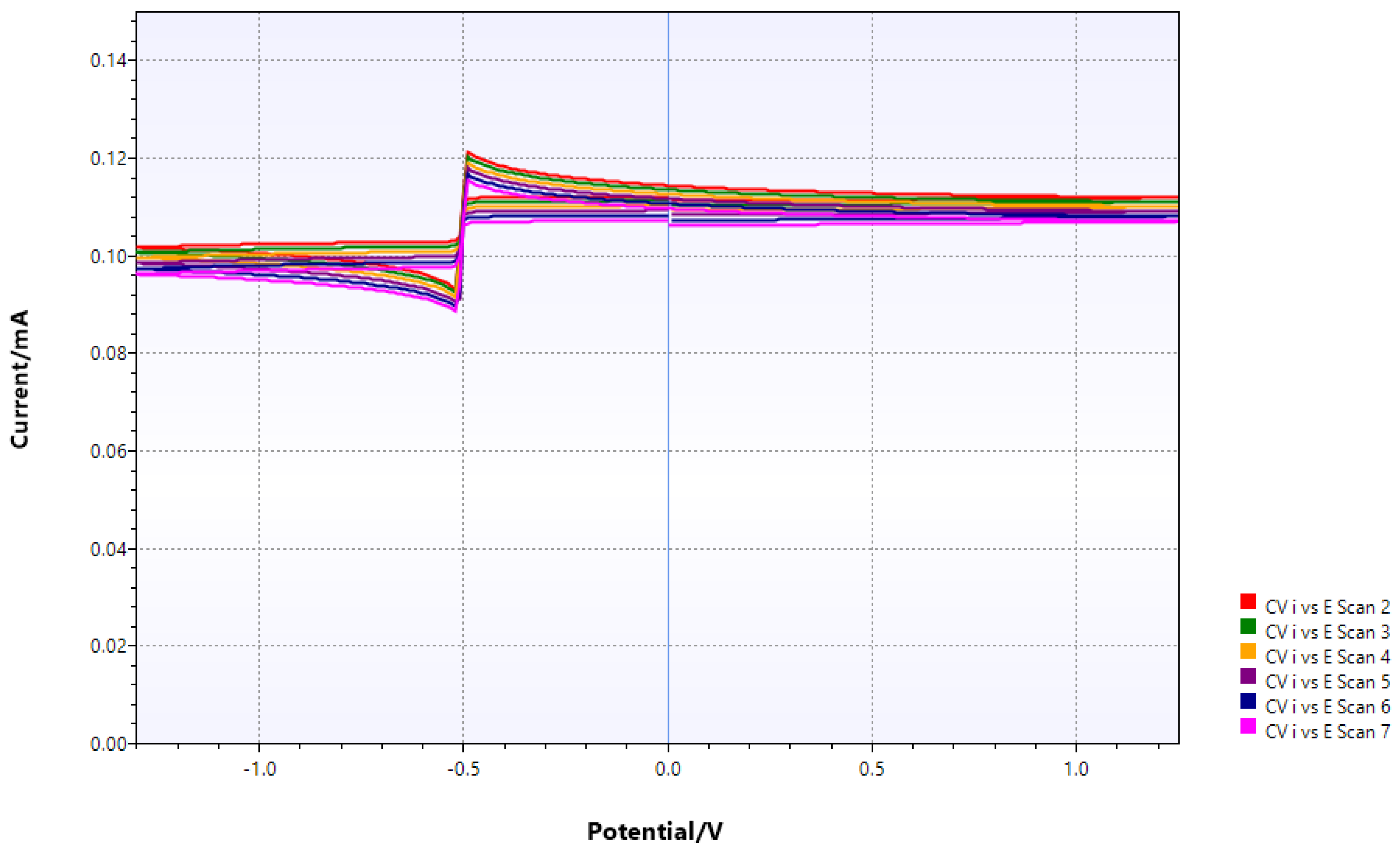

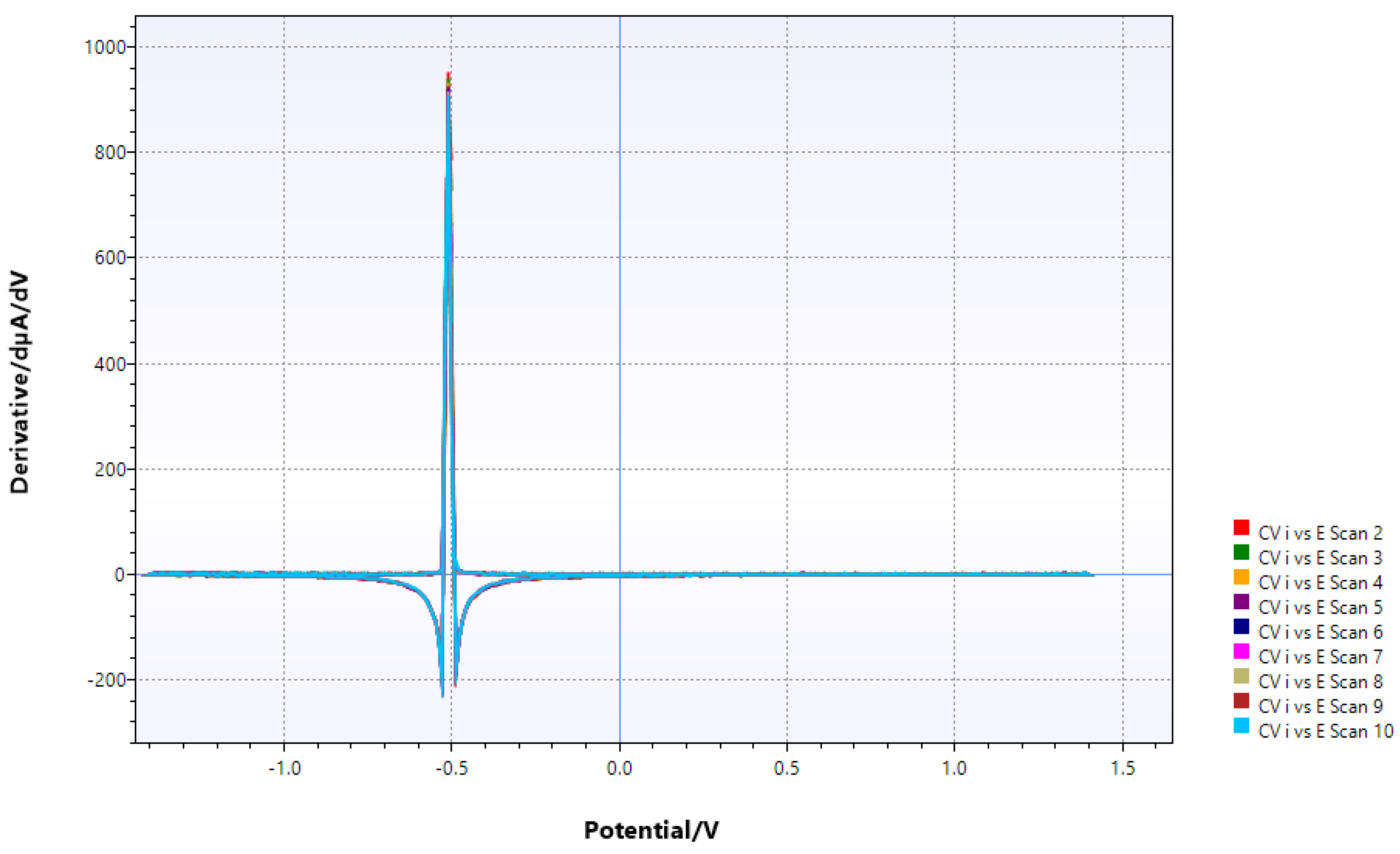

Similar experiments with a Mo_Ga alloy showed essentially the same results, namely reduction of the Mo redox series comprising two or three transitions from Mo(VI) [added as NH4 heptamolybdate] to Mo metal in slightly acidic (acetate buffer) conditions

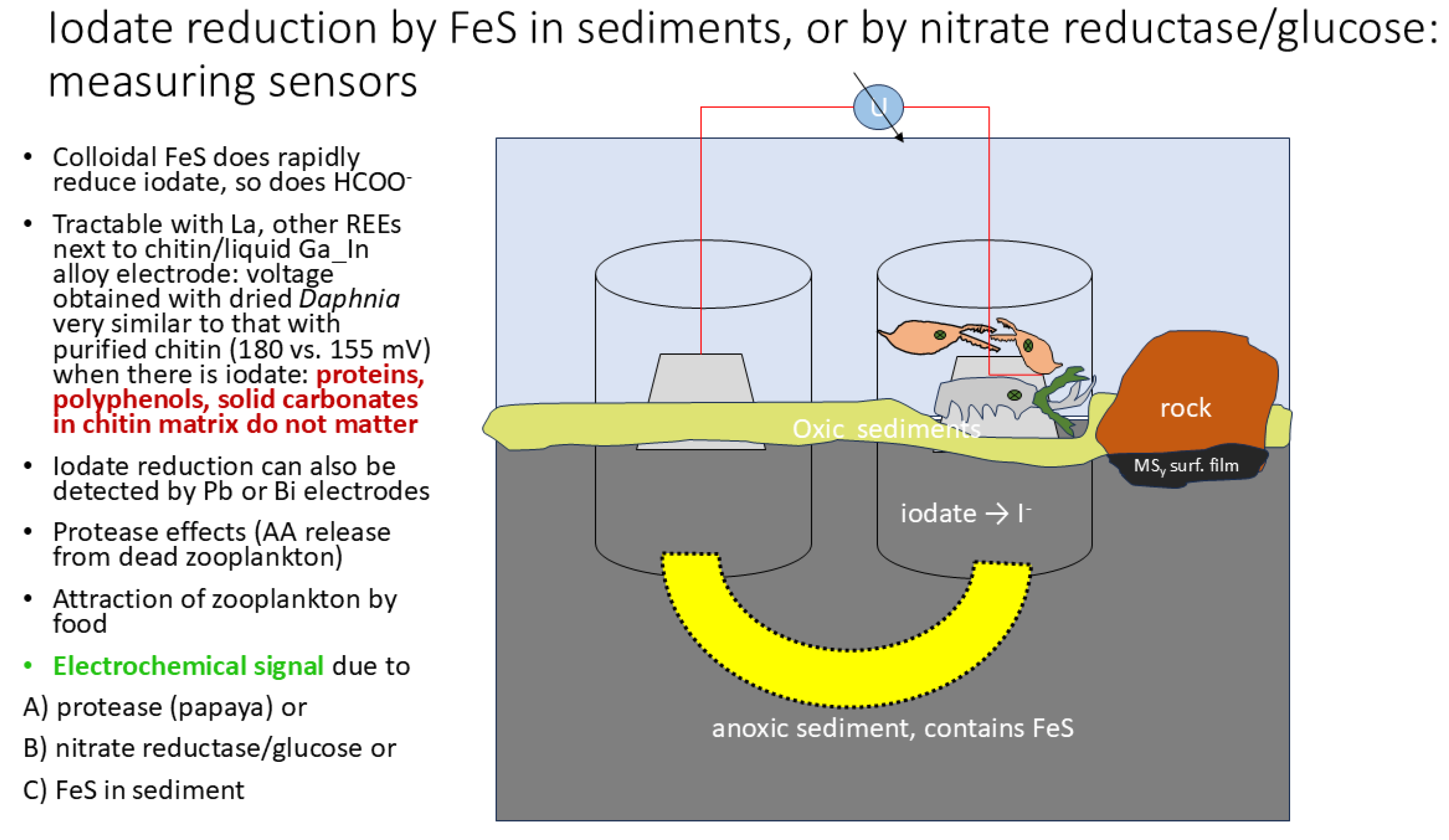

The following picture (

Figure 10) summarizes the results.

Figure 10.

brown cylinder: bridging ligand some of which cause fast e

- transfer from Eu to V [

12]. There is just one redox transition next to chitin instead of the series observed without chitin (cp. Pourbaix diagrams of V, Eu):.

Figure 10.

brown cylinder: bridging ligand some of which cause fast e

- transfer from Eu to V [

12]. There is just one redox transition next to chitin instead of the series observed without chitin (cp. Pourbaix diagrams of V, Eu):.

Figure 11.

Pourbaix diagrams for Eu, simple and with carbonate, S species.

Figure 11.

Pourbaix diagrams for Eu, simple and with carbonate, S species.

Figure 12.

Pourbaix diagram of Mo to a single signal

Figure 12.

Pourbaix diagram of Mo to a single signal

Figure 13.

CV of Mo/dppe bound to chitin. The only redox signal possibly represents the Mo(III)/MoO

2/protonated molybdate triple point, And(

Figure 14).

Figure 13.

CV of Mo/dppe bound to chitin. The only redox signal possibly represents the Mo(III)/MoO

2/protonated molybdate triple point, And(

Figure 14).

Figure 14.

after addition of dppe (very little change).

Figure 14.

after addition of dppe (very little change).

Here, dppe was added for comparison with the well-known [Mo(dppe)

2XY] ligand electrochemical series ([

16]; where X are N

2, CO; Y can be the same or various anions] and again to start subsequent protonating reductions [

17]. Eu + light does produce a multitude of electrochemically active radcals from organics including ligands (visible as noise over a large range of potentials); concerning applications it should be noted that similar species produced by ionizing radiation bring about N

2 reduction with Mo phosphine complexes [

18]. Carbonyl-thiocyanatocomplexes of Mo(III) containing halidoligands and both linkage isomers of SCN

- were prepared by a photochemical method and studied by this author (SF) before: [

19,

20].

A homogeneous mixture was produced by adding THF to the water/acetic acid (proton source) system. Chitin admixture (CV taken 9.5 h afterwards) causes some of the NH4 heptamolybdate to dissolve, plus a substantial increase of the potential:

Figure 15.

Mo/dppe system containing chitin after extended photolysis.

Figure 15.

Mo/dppe system containing chitin after extended photolysis.

While the fairly bulky complex does readily adsorb to chitin, leaving just one redox transition which probably corresponds to Mo(VI)/Mo(III), likely without a ligand because the complex will not make it into the chitin structure. After adding Eu and CH

3OH acting as a possible H atom donor in photolysis [

5,

21,

22], little changed except for corrosion problems. The increase of the potential after adsorption to chitin does imply now the level of the free reduced species (i.e., Mo

3+ or MoO

2) has sharply declined; however, oxoanions of elements like Cr, As, or Se also bind to chitin [

23,

24].

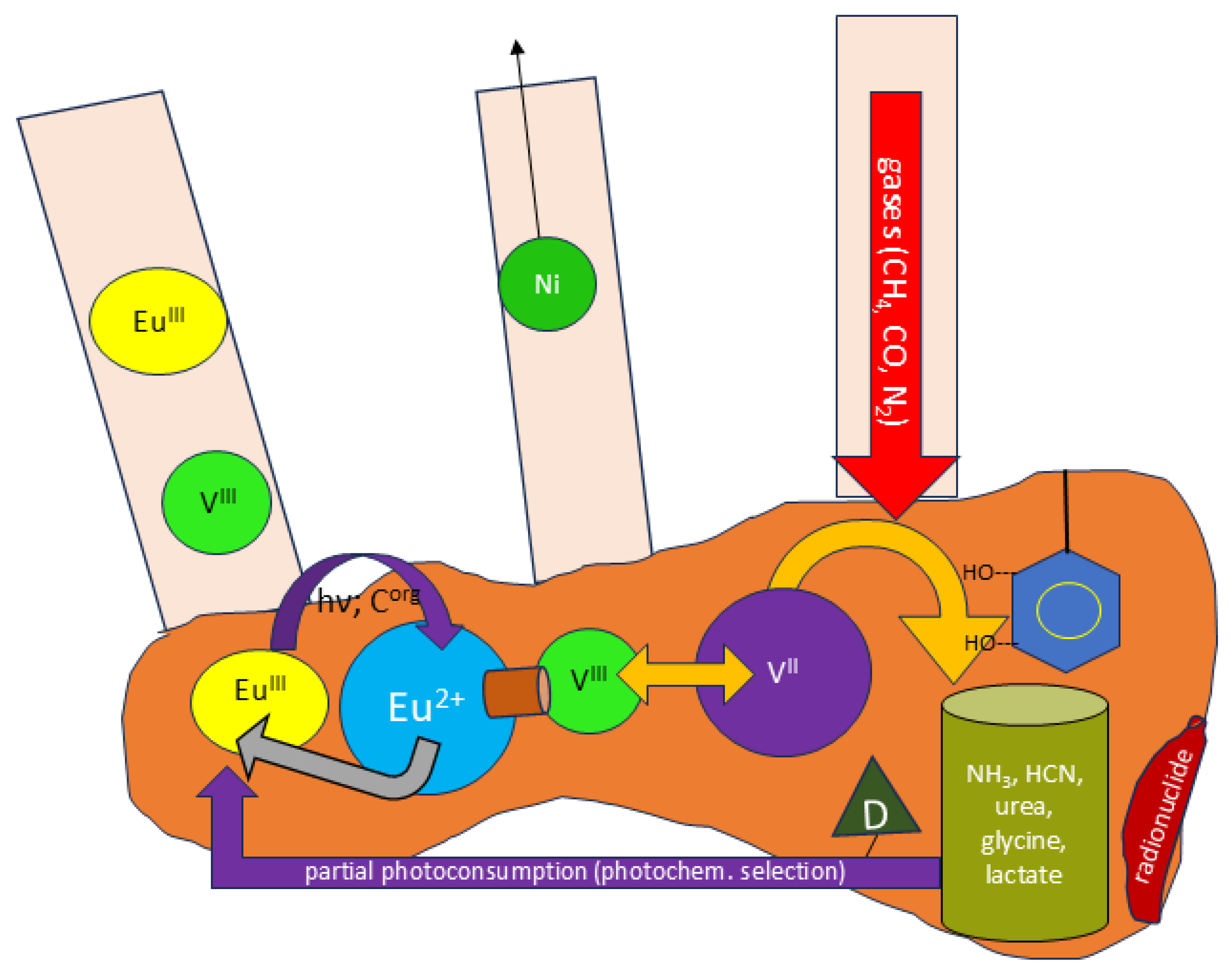

Given the long period of time it takes to get some equilibrium voltage in the setup, it is obviously difficult to construct effective sensors, especially such involving mobility of living arthropods (

Figure 16):

NAND gates based on modification of chitin were discussed by us in a previous paper [

25]. There will be some feedback of products to Eu-mediated photochemistry when admitted gases (CH

4, NH

3, CO, N

2, H

2, water vapor) get exposed to ionizing radiation (towards which chitin is remarkably stable [

26,

27]), with the products (or N

2, CO themselves) reacting with either Eu (by photooxidation [

5,

20]) or V [

13,

14]. This is shown in the following picture (

Figure 17):

Limits of operation of Eu as a pusher/piston for moving other ions/molecules subsequent to photochemical at or right below the chitin surface may be derived from the Pourbaix diagram but the electrochemical data show that transitions cannot be attributed to Eu(II/III) alone in this heterogeneous and metal-mixed system.

The relative efficiency of different radiation kinds is shown in the following table:

Table 4.

radiation chemistry of CH

4/CO/N

2, NH

3, water vapor + H

2 (resumed from [

26]). The molecules given in blue (corresponding to active wavelength λ ≈ 394 nm) can be photochemically degraded by Eu(III) [little so with glycine, but not sarcosine, N,N-dimethylglycine].

Table 4.

radiation chemistry of CH

4/CO/N

2, NH

3, water vapor + H

2 (resumed from [

26]). The molecules given in blue (corresponding to active wavelength λ ≈ 394 nm) can be photochemically degraded by Eu(III) [little so with glycine, but not sarcosine, N,N-dimethylglycine].

| Kind of energy source |

glycine |

HCN |

urea |

lactate |

others |

Remarks, references |

| α particles |

no |

|

|

|

HCOOH, succinic acid [29] when there is Fe2+

|

Rapid removal of aminogroups from glycine by α particles produced via 10B (n, α)→ 7Li [30] |

| High-energy (MeV) protons |

no |

? |

yes |

no |

acetamide, acetone [31] |

Glycine and serine form when protons pass through a CO/N2/H2O(g) mixture [27,32] |

| β- radiation/electron beams |

yes |

yes |

Yes, much |

yes |

CH3COOH |

|

| X-ray/γ radiation |

yes |

no |

no |

little |

Much methyl-, ethylamine, acetate |

Rather low G values [26,33] |

Glyconitrils (cyanohydrins) are also highly photoactive towards Eu(III)* [

5], but not its hydrolysis product glycolic acid. Pure β emitters like tritium or

147Pm are best suited for processing the material. Thus, the feedback system would operate with β- or (less effective) γ-radiation sources, with CN

-, or SCN

- (formed when there is elemental sulfur) acting as bridges transferring electrons from Eu to V. NH

3 is produced both by radiation (reduction of N

2 or nitrate) and by V(II)/catecholate system [

13]. β

- -emitting radionuclides tightly withhold by chitin include fission products such as

90Y,

142La,

141,144Ce,

147Pm,

151,155Sm,

154,155Eu [

28] and

210Pb,

210,214Bi from natural decay chains [

34]. In others such as

90Sr,

92Y,

227Ac additional intense γ radiation [

33] would alter the spectrum of products removing urea and HCN, modifying response of electrode materials like copper. Unlike α particles, proton radiation (from a beam or

3He (n, p)→ T rather than hard-to-obtain nuclides beyond the proton drip-line) would hardly produce any substances then processed by adsorbed Eu; α particles only work when combined with Fe(II) [

26,

29].

Apart from this, one would think that small ligands penetrating the surface (CO, PF3, PMe3, N2O, HC2-CN, etc.) might also control behavior of metal ions shifted within the chitin structure by starting or stopping interaction with moved metal ions, causing other reactions or redox transitions. This might be related to the performance of chitin-modified metal electrodes.

Metal ion diffusion perpendicular to some chitin surface was demonstrated before [

9], sometimes even forming clear-cut diffusion fronts in deeper layers of chitin several weeks after salts of the respective elements (Al, Co) had been applied to the surface. Some part of Ni, Cu, or Pb sticks at this surface [

9] whereas here Ni and Cu can be removed from the surface by applying Eu/photochemical substrate/light. However, given the structure of bulk chitin, one would expect there are kinds of voids in between the chitin biopolymer strands (don’t try to fix dissolved chitin to some metal surface by water-induced precipitation. While it will stick on e.g., Ta, Cu- or Ni surfaces such a chitin film is a perfect electrical isolator).

Even though total electric energy densities are small, except for Bi(III), it should be emphasized that one of our objectives is with producing green energy employing non-toxic metals and chitin. The comparison between purified chitin (from Pandalus borealis shrimp peeling, removing most of the protein and polyphenols) and the native material (dried water flies or sandhoppers) does show little differences in voltage. Accordingly, voltages in either system are due to the presence of polysaccharide chitin rather than that of any additional component linked to it (catechols would undergo redox transitions of their own, for example). Bi metal should be combined with raw chitin and thiourea ligand to obtain significant energy output, power amplification being achieved by some buffer accumulator.