Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

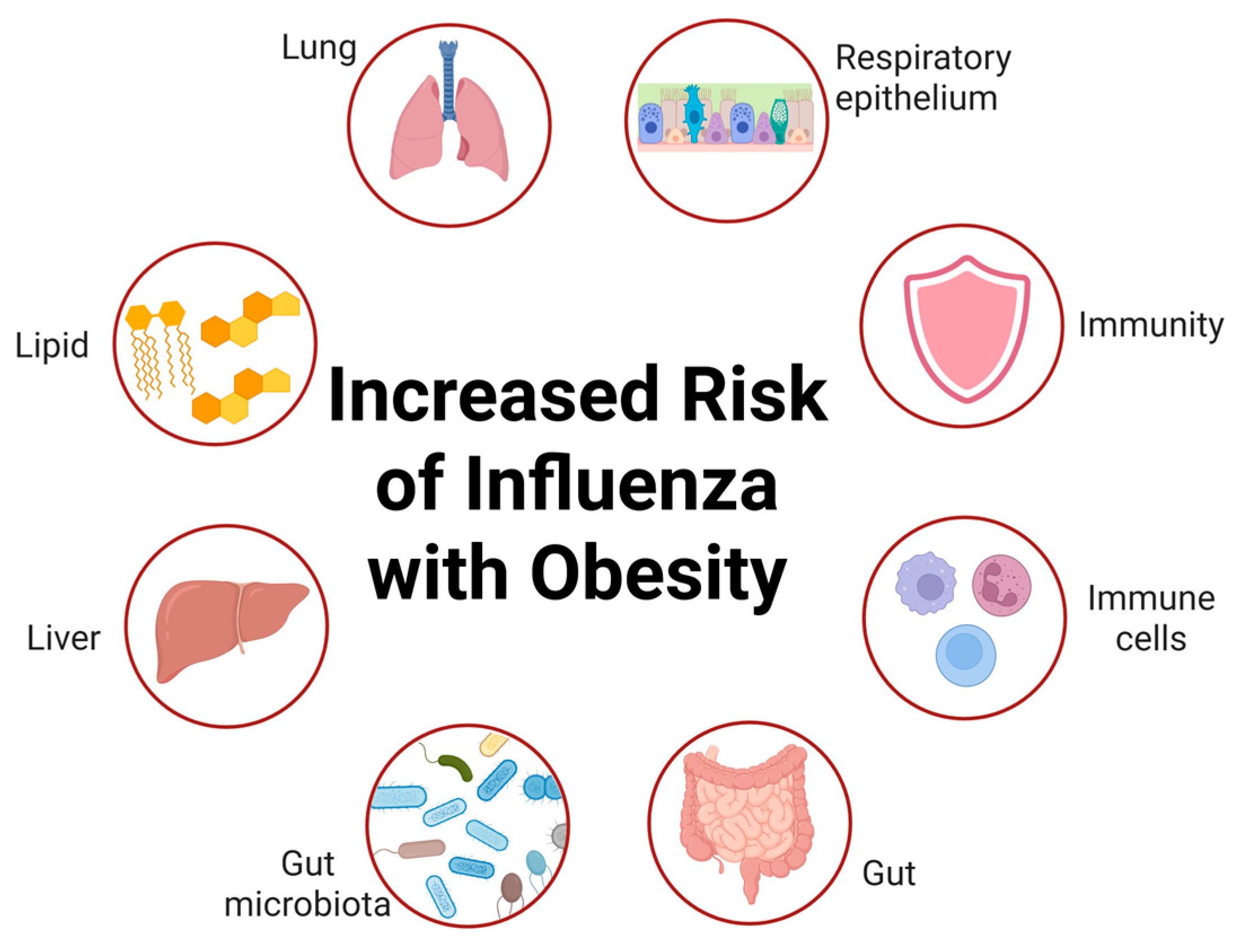

2. The Epidemiological Association Between Obesity and Influenza Infection

3. The Relationship Between Obesity and Gut Microbiota

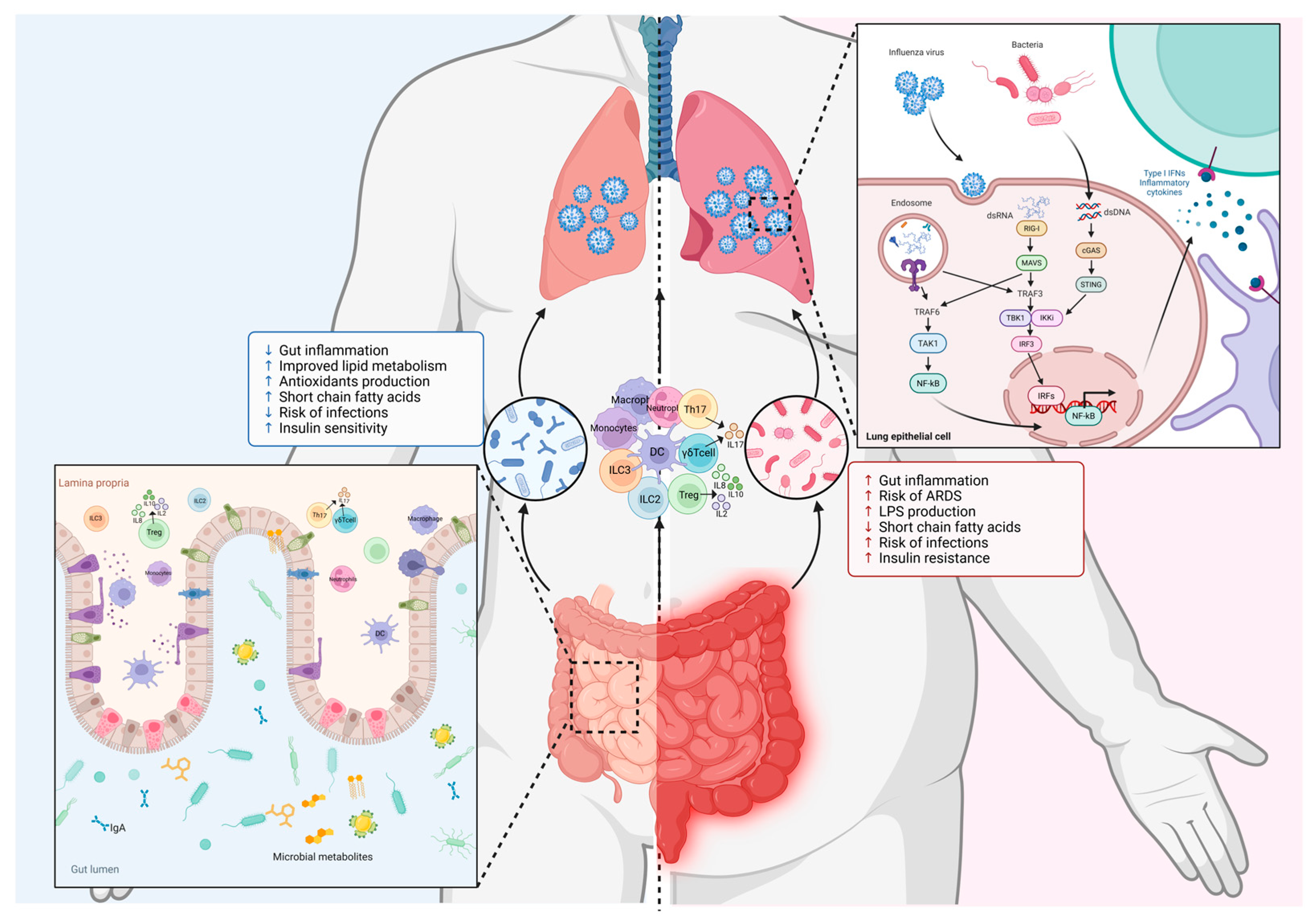

4. Mechanisms of the Interaction Between Gut Microbes and the Respiratory Immune System

5. Gut-Lung Axis in Influenza Virus Infection

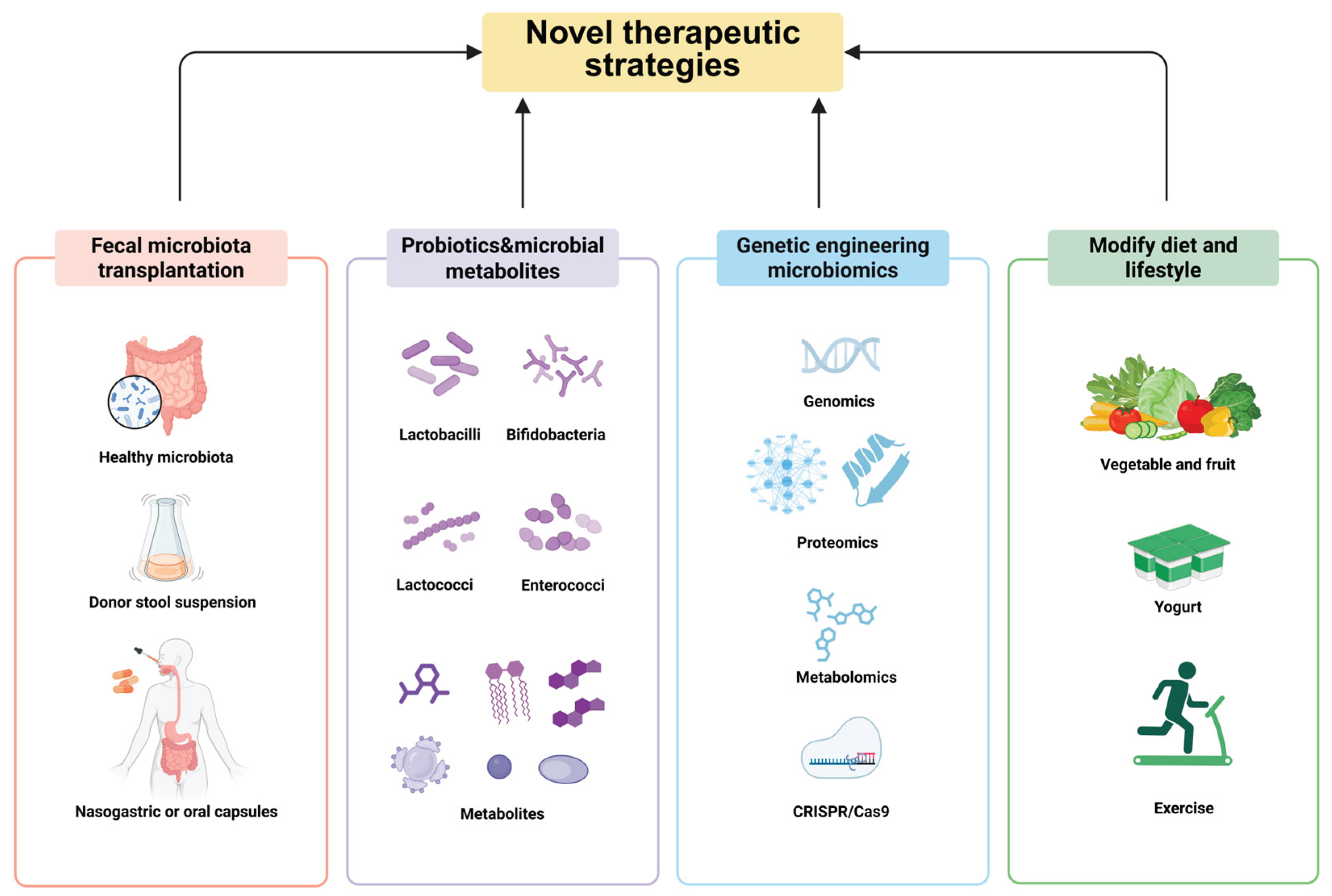

6. Targeting the Gut Microbiota to Treat Influenza

6.1. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

6.2. Targeted Therapy of Probiotics and Microbial Metabolites

6.3. Transgenic Microbial Therapy

6.4. Modify Diet and Lifestyle

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease, C. and Prevention, Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza --- United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2010. 59(33): p. 1057-62.

- Shrestha, S.S.; Swerdlow, D.L.; Borse, R.H.; Prabhu, V.S.; Finelli, L.; Atkins, C.Y.; Owusu-Edusei, K.; Bell, B.; Mead, P.S.; Biggerstaff, M.; et al. Estimating the Burden of 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) in the United States (April 2009-April 2010). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 52, S75–S82. [CrossRef]

- Tumpey, T.M.; Basler, C.F.; Aguilar, P.V.; Zeng, H.; SolórZano, A.; Swayne, D.E.; Cox, N.J.; Katz, J.M.; Taubenberger, J.K.; Palese, P.; et al. Characterization of the Reconstructed 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic Virus. Science 2005, 310, 77–80. [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; McBride, R.; Paulson, J.C.; Basler, C.F.; Wilson, I.A. Structure, Receptor Binding, and Antigenicity of Influenza Virus Hemagglutinins from the 1957 H2N2 Pandemic. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1715–1721. [CrossRef]

- West, J., et al., Characterization of changes in the hemagglutinin that accompanied the emergence of H3N2/1968 pandemic influenza viruses. PLoS Pathog, 2021. 17(9): p. e1009566.

- Taubenberger, J.K. and D.M. Morens, 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerg Infect Dis, 2006. 12(1): p. 15-22.

- Janssen, I., P.T. Katzmarzyk, and R. Ross, Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: evidence in support of current National Institutes of Health guidelines. Arch Intern Med, 2002. 162(18): p. 2074-9.

- Alexopoulos, S.J.; Chen, S.-Y.; Brandon, A.E.; Salamoun, J.M.; Byrne, F.L.; Garcia, C.J.; Beretta, M.; Olzomer, E.M.; Shah, D.P.; Philp, A.M.; et al. Mitochondrial uncoupler BAM15 reverses diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Ding, C.; Liu, Q.; Ma, T.; Han, X.; Lu, D.; Zhang, L. The association between sarcopenia and cardiovascular disease: An investigative analysis from the NHANES. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 103864. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, B., Humans against Obesity: Who Will Win? Adv Nutr, 2019. 10(suppl_1): p. S4-S9.

- Hornung, F.; Schulz, L.; Köse-Vogel, N.; Häder, A.; Grießhammer, J.; Wittschieber, D.; Autsch, A.; Ehrhardt, C.; Mall, G.; Löffler, B.; et al. Thoracic adipose tissue contributes to severe virus infection of the lung. Int. J. Obes. 2023, 47, 1088–1099. [CrossRef]

- Louie, J.K.; Acosta, M.; Samuel, M.C.; Schechter, R.; Vugia, D.J.; Harriman, K.; Matyas, B.T. A Novel Risk Factor for a Novel Virus: Obesity and 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, 301–312. [CrossRef]

- Mafort, T.T., et al., Obesity: systemic and pulmonary complications, biochemical abnormalities, and impairment of lung function. Multidiscip Respir Med, 2016. 11: p. 28.

- Falagas, M.E.; Athanasoulia, A.P.; Peppas, G.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E. Effect of body mass index on the outcome of infections: a systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 280–289. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Grantham, M.; Pantelic, J.; de Mesquita, P.J.B.; Albert, B.; Liu, F.; Ehrman, S.; Milton, D.K. Infectious virus in exhaled breath of symptomatic seasonal influenza cases from a college community. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 1081–1086. [CrossRef]

- Elliot, J.G.; Donovan, G.M.; Wang, K.C.; Green, F.H.; James, A.L.; Noble, P.B. Fatty airways: implications for obstructive disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1900857. [CrossRef]

- Kwong, J.C.; Campitelli, M.A.; Rosella, L.C. Obesity and Respiratory Hospitalizations During Influenza Seasons in Ontario, Canada: A Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 413–421. [CrossRef]

- E Maier, H.; Lopez, R.; Sanchez, N.; Ng, S.; Gresh, L.; Ojeda, S.; Burger-Calderon, R.; Kuan, G.; Harris, E.; Balmaseda, A.; et al. Obesity Increases the Duration of Influenza A Virus Shedding in Adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1378–1382. [CrossRef]

- Fezeu, L.; Julia, C.; Henegar, A.; Bitu, J.; Hu, F.B.; Grobbee, D.E.; Kengne, A.-P.; Hercberg, S.; Czernichow, S. Obesity is associated with higher risk of intensive care unit admission and death in influenza A (H1N1) patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 653–659. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.; Rodríguez, A.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Lorente, L.; Del Mar Martín, M.; Pozo, J.C.; Montejo, J.C.; Estella, A.; Arenzana, .; Rello, J. Impact of Obesity in Patients Infected With 2009 Influenza A(H1N1). Chest 2011, 139, 382–386. [CrossRef]

- Kok, J.; Blyth, C.C.; Foo, H.; Bailey, M.J.; Pilcher, D.V.; Webb, S.A.; Seppelt, I.M.; Dwyer, D.E.; Iredell, J.R.; Semple, M.G. Viral Pneumonitis Is Increased in Obese Patients during the First Wave of Pandemic A(H1N1) 2009 Virus. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e55631. [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, L.; La Ruche, G.; Tarantola, A.; Barboza, P.; for the epidemic intelligence team at InVS Epidemiology of fatal cases associated with pandemic H1N1 influenza 2009. Eurosurveillance 2009, 14, 19309. [CrossRef]

- Investigators, A.I., et al., Critical care services and 2009 H1N1 influenza in Australia and New Zealand. N Engl J Med, 2009. 361(20): p. 1925-34.

- Andrew, M.K.; Pott, H.; Staadegaard, L.; Paget, J.; Chaves, S.S.; Ortiz, J.R.; McCauley, J.; Bresee, J.; Nunes, M.C.; Baumeister, E.; et al. Age Differences in Comorbidities, Presenting Symptoms, and Outcomes of Influenza Illness Requiring Hospitalization: A Worldwide Perspective From the Global Influenza Hospital Surveillance Network. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad244. [CrossRef]

- E Cohen, L.; Hansen, C.L.; Andrew, M.K.; A McNeil, S.; Vanhems, P.; Kyncl, J.; Domingo, J.D.; Zhang, T.; Dbaibo, G.; Laguna-Torres, V.A.; et al. Predictors of Severity of Influenza-Related Hospitalizations: Results From the Global Influenza Hospital Surveillance Network (GIHSN). J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 229, 999–1009. [CrossRef]

- Lau, D.; Tobin, S.; Pribiag, H.; Nakajima, S.; Fisette, A.; Matthys, D.; Flores, A.K.F.; Peyot, M.-L.; Madiraju, S.R.M.; Prentki, M.; et al. ABHD6 loss-of-function in mesoaccumbens postsynaptic but not presynaptic neurons prevents diet-induced obesity in male mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Men, Y.; Bartlett, A.; Hernández, M.A.S.; Xu, J.; Yi, X.; Li, H.-S.; Kong, D.; Mazitschek, R.; Ozcan, U. Central inhibition of HDAC6 re-sensitizes leptin signaling during obesity to induce profound weight loss. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 857–876.e10. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Luo, C.; Sun, L.; Feng, T.; Yin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Mulholland, M.W.; Zhang, W.; Yin, Y. Reduction of specific enterocytes from loss of intestinal LGR4 improves lipid metabolism in mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Sass, F.; Ma, T.; Ekberg, J.H.; Kirigiti, M.; Ureña, M.G.; Dollet, L.; Brown, J.M.; Basse, A.L.; Yacawych, W.T.; Burm, H.B.; et al. NK2R control of energy expenditure and feeding to treat metabolic diseases. Nature 2024, 635, 987–1000. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J., et al., GLP-1-directed NMDA receptor antagonism for obesity treatment. Nature, 2024. 629(8014): p. 1133-1141.

- Fadahunsi, N.; Petersen, J.; Metz, S.; Jakobsen, A.; Mathiesen, C.V.; Buch-Rasmussen, A.S.; Kurgan, N.; Larsen, J.K.; Andersen, R.C.; Topilko, T.; et al. Targeting postsynaptic glutamate receptor scaffolding proteins PSD-95 and PICK1 for obesity treatment. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadg2636. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Lyu, X.; Markhard, A.L.; Fu, S.; Mardjuki, R.E.; Cavanagh, P.E.; Zeng, X.; Rajniak, J.; Lu, N.; Xiao, S.; et al. PTER is a N-acetyltaurine hydrolase that regulates feeding and obesity. Nature 2024, 633, 182–188. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, P.; Liu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, T.; Tang, Q.; Jia, Q.; et al. B3galt5 functions as a PXR target gene and regulates obesity and insulin resistance by maintaining intestinal integrity. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Liu, K.; Sun, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, X. Influenza A virus infection activates STAT3 to enhance SREBP2 expression, cholesterol biosynthesis, and virus replication. iScience 2024, 27, 110424. [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ma, D.; Zhang, M.; Tang, M.; Ouyang, T.; Zhang, F.; Shi, X.; et al. Paraventricular hypothalamic RUVBL2 neurons suppress appetite by enhancing excitatory synaptic transmission in distinct neurocircuits. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Thingholm, L.B., et al., Obese Individuals with and without Type 2 Diabetes Show Different Gut Microbial Functional Capacity and Composition. Cell Host Microbe, 2019. 26(2): p. 252-264 e10.

- Menni, C.; A Jackson, M.; Pallister, T.; Steves, C.J.; Spector, T.D.; Valdes, A.M. Gut microbiome diversity and high-fibre intake are related to lower long-term weight gain. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1099–1105. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Huang, W.; Lin, Y.; Chan, F.K.; Ng, S.C. Gut microbiota in patients with obesity and metabolic disorders — a systematic review. Genes Nutr. 2022, 17, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Kasai, C.; Sugimoto, K.; Moritani, I.; Tanaka, J.; Oya, Y.; Inoue, H.; Tameda, M.; Shiraki, K.; Ito, M.; Takei, Y.; et al. Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between obese and non-obese individuals in a Japanese population, as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and next-generation sequencing. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015, 15, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.J., N.P. West, and A.W. Cripps, Obesity, inflammation, and the gut microbiota. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2015. 3(3): p. 207-15.

- Jumpertz, R.; Le, D.S.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Trinidad, C.; Bogardus, C.; Gordon, J.I.; Krakoff, J. Energy-Balance Studies Reveal Associations between Gut Microbes, Caloric Load, and Nutrient Absorption in Humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Choi, H.-N.; Yim, J.-E. Effect of Diet on the Gut Microbiota Associated with Obesity. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 28, 216–224. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Mao, K.; Chen, X.; Sun, M.-A.; Kawabe, T.; Li, W.; Usher, N.; Zhu, J.; Urban, J.F., Jr.; Paul, W.E.; et al. S1P-dependent interorgan trafficking of group 2 innate lymphoid cells supports host defense. Science 2018, 359, 114–119. [CrossRef]

- Olszak, T.; An, D.; Zeissig, S.; Vera, M.P.; Richter, J.; Franke, A.; Glickman, J.N.; Siebert, R.; Baron, R.M.; Kasper, D.L.; et al. Microbial Exposure During Early Life Has Persistent Effects on Natural Killer T Cell Function. Science 2012, 336, 489–493. [CrossRef]

- Alon, R.; Sportiello, M.; Kozlovski, S.; Kumar, A.; Reilly, E.C.; Zarbock, A.; Garbi, N.; Topham, D.J. Leukocyte trafficking to the lungs and beyond: lessons from influenza for COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 21, 49–64. [CrossRef]

- Pick, R.; He, W.; Chen, C.-S.; Scheiermann, C. Time-of-Day-Dependent Trafficking and Function of Leukocyte Subsets. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 524–537. [CrossRef]

- Zundler, S.; Günther, C.; Kremer, A.E.; Zaiss, M.M.; Rothhammer, V.; Neurath, M.F. Gut immune cell trafficking: inter-organ communication and immune-mediated inflammation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 50–64. [CrossRef]

- Uchimura, Y.; Fuhrer, T.; Li, H.; Lawson, M.A.; Zimmermann, M.; Yilmaz, B.; Zindel, J.; Ronchi, F.; Sorribas, M.; Hapfelmeier, S.; et al. Antibodies Set Boundaries Limiting Microbial Metabolite Penetration and the Resultant Mammalian Host Response. Immunity 2018, 49, 545–559.e5. [CrossRef]

- Trompette, A.; Pernot, J.; Perdijk, O.; Alqahtani, R.A.A.; Domingo, J.S.; Camacho-Muñoz, D.; Wong, N.C.; Kendall, A.C.; Wiederkehr, A.; Nicod, L.P.; et al. Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids modulate skin barrier integrity by promoting keratinocyte metabolism and differentiation. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 908–926. [CrossRef]

- Trompette, A.; Gollwitzer, E.S.; Yadava, K.; Sichelstiel, A.K.; Sprenger, N.; Ngom-Bru, C.; Blanchard, C.; Junt, T.; Nicod, L.P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 159–166. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T.B.; Davis, K.M.; Lysenko, E.S.; Zhou, A.Y.; Yu, Y.; Weiser, J.N. Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 228–231. [CrossRef]

- Trompette, A.; Gollwitzer, E.S.; Pattaroni, C.; Lopez-Mejia, I.C.; Riva, E.; Pernot, J.; Ubags, N.; Fajas, L.; Nicod, L.P.; Marsland, B.J. Dietary Fiber Confers Protection against Flu by Shaping Ly6c− Patrolling Monocyte Hematopoiesis and CD8+ T Cell Metabolism. Immunity 2018, 48, 992–1005.e8. [CrossRef]

- A Hill, D.; Siracusa, M.C.; Abt, M.C.; Kim, B.S.; Kobuley, D.; Kubo, M.; Kambayashi, T.; LaRosa, D.F.; Renner, E.D.; Orange, J.S.; et al. Commensal bacteria–derived signals regulate basophil hematopoiesis and allergic inflammation. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 538–546. [CrossRef]

- Maurice, C.F.; Haiser, H.J.; Turnbaugh, P.J. Xenobiotics Shape the Physiology and Gene Expression of the Active Human Gut Microbiome. Cell 2013, 152, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G.C.Y.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Li, A.Y.L.; Zhan, H.; Wan, Y.; Chung, A.C.K.; Cheung, C.P.; Chen, N.; et al. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 944–955.e948. [CrossRef]

- Sencio, V.; Barthelemy, A.; Tavares, L.P.; Machado, M.G.; Soulard, D.; Cuinat, C.; Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; Noordine, M.-L.; Salomé-Desnoulez, S.; Deryuter, L.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis during Influenza Contributes to Pulmonary Pneumococcal Superinfection through Altered Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 2934–2947.e6. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., et al., Respiratory influenza virus infection induces intestinal immune injury via microbiota-mediated Th17 cell-dependent inflammation. J Exp Med, 2014. 211(12): p. 2397-410.

- Laidlaw, B.J.; Zhang, N.; Marshall, H.D.; Staron, M.M.; Guan, T.; Hu, Y.; Cauley, L.S.; Craft, J.; Kaech, S.M. CD4+ T Cell Help Guides Formation of CD103+ Lung-Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells during Influenza Viral Infection. Immunity 2014, 41, 633–645. [CrossRef]

- Mann, E.R.; Lam, Y.K.; Uhlig, H.H. Short-chain fatty acids: linking diet, the microbiome and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 577–595. [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, M.; Ichinohe, T. High ambient temperature dampens adaptive immune responses to influenza A virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 3118–3125. [CrossRef]

- Bachem, A.; Makhlouf, C.; Binger, K.J.; de Souza, D.P.; Tull, D.; Hochheiser, K.; Whitney, P.G.; Fernandez-Ruiz, D.; Dähling, S.; Kastenmüller, W.; et al. Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Promote the Memory Potential of Antigen-Activated CD8+ T Cells. Immunity 2019, 51, 285–297 e285. [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, P.C.; Ulanowicz, C.J.; A Damen, M.S.M.; Eom, J.; Sawada, K.; Chung, H.; Alahakoon, T.; Oates, J.R.; Wayland, J.L.; E Stankiewicz, T.; et al. Obesity Uncovers the Presence of Inflammatory Lung Macrophage Subsets With an Adipose Tissue Transcriptomic Signature in Influenza Virus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 231, e317–e327. [CrossRef]

- Castro, I.A.; Jorge, D.M.M.; Ferreri, L.M.; Martins, R.B.; Pontelli, M.C.; Jesus, B.L.S.; Cardoso, R.S.; Criado, M.F.; Carenzi, L.; Valera, F.C.P.; et al. Silent Infection of B and CD8 + T Lymphocytes by Influenza A Virus in Children with Tonsillar Hypertrophy. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [CrossRef]

- Hensen, L.; Illing, P.T.; Clemens, E.B.; Nguyen, T.H.O.; Koutsakos, M.; van de Sandt, C.E.; Mifsud, N.A.; Nguyen, A.T.; Szeto, C.; Chua, B.Y.; et al. CD8+ T cell landscape in Indigenous and non-Indigenous people restricted by influenza mortality-associated HLA-A*24:02 allomorph. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Koutsakos, M., et al., Human CD8(+) T cell cross-reactivity across influenza A, B and C viruses. Nat Immunol, 2019. 20(5): p. 613-625.

- van de Wall, S., et al., Dynamic landscapes and protective immunity coordinated by influenza-specific lung-resident memory CD8(+) T cells revealed by intravital imaging. Immunity, 2024. 57(8): p. 1878-1892 e5.

- Schmidt, A.; Fuchs, J.; Dedden, M.; Kocher, K.; Schülein, C.; Hübner, J.; Antão, A.V.; Irrgang, P.; Oltmanns, F.; Viherlehto, V.; et al. Inflammatory conditions shape phenotypic and functional characteristics of lung-resident memory T cells in mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Pritzl, C.J.; Luera, D.; Knudson, K.M.; Quaney, M.J.; Calcutt, M.J.; Daniels, M.A.; Teixeiro, E. IKK2/NFkB signaling controls lung resident CD8+ T cell memory during influenza infection. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Yuan, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hu, Y.; et al. Anaerostipes caccae CML199 enhances bone development and counteracts aging-induced bone loss through the butyrate-driven gut–bone axis: the chicken model. Microbiome 2024, 12, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.T.; Begka, C.; Pattaroni, C.; Caley, L.R.; Floto, R.A.; Peckham, D.G.; Marsland, B.J. Butyrate regulates neutrophil homeostasis and impairs early antimicrobial activity in the lung. Mucosal Immunol. 2023, 16, 476–485. [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.J.; Messina, N.L.; Clarke, C.J.; Johnstone, R.W.; Levy, D.E. Constitutive Type I Interferon Modulates Homeostatic Balance through Tonic Signaling. Immunity 2012, 36, 166–174. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Du, F.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase Is a Cytosolic DNA Sensor That Activates the Type I Interferon Pathway. Science 2013, 339, 786–791. [CrossRef]

- Loo, Y.-M.; Gale, M., Jr. Immune Signaling by RIG-I-like Receptors. Immunity 2011, 34, 680–692. [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Toll-like Receptors and Their Crosstalk with Other Innate Receptors in Infection and Immunity. Immunity 2011, 34, 637–650. [CrossRef]

- Abt, M.C.; Osborne, L.C.; Monticelli, L.A.; Doering, T.A.; Alenghat, T.; Sonnenberg, G.F.; Paley, M.A.; Antenus, M.; Williams, K.L.; Erikson, J.; et al. Commensal Bacteria Calibrate the Activation Threshold of Innate Antiviral Immunity. Immunity 2012, 37, 158–170. [CrossRef]

- Ichinohe, T.; Pang, I.K.; Kumamoto, Y.; Peaper, D.R.; Ho, J.H.; Murray, T.S.; Iwasaki, A. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5354–5359. [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A.J.; McSorley, H.J.; Davidson, D.J.; Fitch, P.M.; Errington, C.; Mackenzie, K.J.; Gollwitzer, E.S.; Johnston, C.J.; MacDonald, A.S.; Edwards, M.R.; et al. Enteric helminth-induced type I interferon signaling protects against pulmonary virus infection through interaction with the microbiota. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 1068–1078.e6. [CrossRef]

- Stefan, K.L.; Kim, M.V.; Iwasaki, A.; Kasper, D.L. Commensal Microbiota Modulation of Natural Resistance to Virus Infection. Cell 2020, 183, 1312–1324.e10. [CrossRef]

- Schaupp, L.; Muth, S.; Rogell, L.; Kofoed-Branzk, M.; Melchior, F.; Lienenklaus, S.; Ganal-Vonarburg, S.C.; Klein, M.; Guendel, F.; Hain, T.; et al. Microbiota-Induced Type I Interferons Instruct a Poised Basal State of Dendritic Cells. Cell 2020, 181, 1080–1096.e19. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, E.S.; Shrihari, S.; Hykes, B.L.; Handley, S.A.; Andhey, P.S.; Huang, Y.-J.S.; Swain, A.; Droit, L.; Chebrolu, K.K.; Mack, M.; et al. The Intestinal Microbiome Restricts Alphavirus Infection and Dissemination through a Bile Acid-Type I IFN Signaling Axis. Cell 2020, 182, 901–918.e18. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.-M.; He, W.-R.; Gao, P.; Yang, Q.; He, K.; Cao, L.-B.; Li, S.; Feng, Y.-Q.; Shu, H.-B. Virus-induced accumulation of intracellular bile acids activates the TGR5-β-arrestin-SRC axis to enable innate antiviral immunity. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 193–205. [CrossRef]

- Steed, A.L.; Christophi, G.P.; Kaiko, G.E.; Sun, L.; Goodwin, V.M.; Jain, U.; Esaulova, E.; Artyomov, M.N.; Morales, D.J.; Holtzman, M.J.; et al. The microbial metabolite desaminotyrosine protects from influenza through type I interferon. Science 2017, 357, 498–502. [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, F.; Li, Z.; Remes-Lenicov, F.; Dávola, M.E.; Elizalde, M.; Paletta, A.; Ashkar, A.A.; Mossman, K.L.; Dugour, A.V.; Figueroa, J.M.; et al. AHR signaling is induced by infection with coronaviruses. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lv, J.; Liu, J.; Li, M.; Xie, J.; Lv, Q.; Deng, W.; Zhou, N.; Zhou, Y.; Song, J.; et al. Mucus production stimulated by IFN-AhR signaling triggers hypoxia of COVID-19. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 1078–1087. [CrossRef]

- Major, J.; Crotta, S.; Finsterbusch, K.; Chakravarty, P.; Shah, K.; Frederico, B.; D’aNtuono, R.; Green, M.; Meader, L.; Suarez-Bonnet, A.; et al. Endothelial AHR activity prevents lung barrier disruption in viral infection. Nature 2023, 621, 813–820. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, K.H.; Singanayagam, A.; Williams, L.; Faiez, T.S.; Farias, A.; Jackson, M.M.; Faizi, F.K.; Aniscenko, J.; Kebadze, T.; Veerati, P.C.; et al. Airway-delivered short-chain fatty acid acetate boosts antiviral immunity during rhinovirus infection. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 151, 447–457.e5. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, K.H.; Fachi, J.L.; De Paula, R.; Da Silva, E.F.; Pral, L.P.; DOS Santos, A.; Dias, G.B.M.; Vargas, J.E.; Puga, R.; Mayer, F.Q.; et al. Microbiota-derived acetate protects against respiratory syncytial virus infection through a GPR43-type 1 interferon response. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3273. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H.K.; Gudmundsdottir, V.; Nielsen, H.B.; Hyotylainen, T.; Nielsen, T.; Jensen, B.A.H.; Forslund, K.; Hildebrand, F.; Prifti, E.; Falony, G.; et al. Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature 2016, 535, 376–381. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhao, C.; Su, N.; Yang, W.; Yang, H.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, N.; Hu, X.; Fu, Y. Disturbances of the gut microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites as key actors in vagotomy-induced mastitis in mice. Cell Rep. 2024, 44, 114585. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.M.; Yabut, J.M.; Choo, J.M.; Page, A.J.; Sun, E.W.; Jessup, C.F.; Wesselingh, S.L.; Khan, W.I.; Rogers, G.B.; Steinberg, G.R.; et al. The gut microbiome regulates host glucose homeostasis via peripheral serotonin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 19802–19804. [CrossRef]

- E Griffin, M.; Hespen, C.W.; Wang, Y.; Hang, H.C. Translation of peptidoglycan metabolites into immunotherapeutics. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2019, 8, e1095. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Qi, X.; Li, N.; Kaifi, J.T.; Chen, S.; Wheeler, A.A.; Kimchi, E.T.; Ericsson, A.C.; Rector, R.S.; Staveley-O’cArroll, K.F.; et al. Western diet contributes to the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in male mice via remodeling gut microbiota and increasing production of 2-oleoylglycerol. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.; Zieba, J.K.; Foegeding, N.J.; Torres, T.P.; Shelton, C.D.; Shealy, N.G.; Byndloss, A.J.; Cevallos, S.A.; Gertz, E.; Tiffany, C.R.; et al. High-fat diet–induced colonocyte dysfunction escalates microbiota-derived trimethylamine N -oxide. Science 2021, 373, 813–818. [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, M.; Yamashita, M.; Ariyoshi, T.; Eguchi, S.; Minemura, A.; Miura, D.; Higashi, S.; Oka, K.; Nonogaki, T.; Mori, T.; et al. Clostridium butyricum-induced ω-3 fatty acid 18-HEPE elicits anti-influenza virus pneumonia effects through interferon-λ upregulation. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111755. [CrossRef]

- Erttmann, S.F.; Swacha, P.; Aung, K.M.; Brindefalk, B.; Jiang, H.; Härtlova, A.; Uhlin, B.E.; Wai, S.N.; Gekara, N.O. The gut microbiota prime systemic antiviral immunity via the cGAS-STING-IFN-I axis. Immunity 2022, 55, 847–861.e10. [CrossRef]

- Platt, D.J.; Lawrence, D.; Rodgers, R.; Schriefer, L.; Qian, W.; Miner, C.A.; Menos, A.M.; Kennedy, E.A.; Peterson, S.T.; Stinson, W.A.; et al. Transferrable protection by gut microbes against STING-associated lung disease. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109113–109113. [CrossRef]

- Broggi, A.; Ghosh, S.; Sposito, B.; Spreafico, R.; Balzarini, F.; Cascio, A.L.; Clementi, N.; De Santis, M.; Mancini, N.; Granucci, F.; et al. Type III interferons disrupt the lung epithelial barrier upon viral recognition. Science 2020, 369, 706–712. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.E.; Zacharias, Z.R.; Ross, K.A.; Narasimhan, B.; Waldschmidt, T.J.; Legge, K.L. Polyanhydride nanovaccine against H3N2 influenza A virus generates mucosal resident and systemic immunity promoting protection. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gaisina, I.; Li, P.; Du, R.; Cui, Q.; Dong, M.; Zhang, C.; Manicassamy, B.; Caffrey, M.; Moore, T.; Cooper, L.; et al. An orally active entry inhibitor of influenza A viruses protects mice and synergizes with oseltamivir and baloxavir marboxil. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk9004. [CrossRef]

- Ou, G.; Xu, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Deng, L.; Chen, X. The gut-lung axis in influenza A: the role of gut microbiota in immune balance. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1147724. [CrossRef]

- Ross, F.C.; Patangia, D.; Grimaud, G.; Lavelle, A.; Dempsey, E.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. The interplay between diet and the gut microbiome: implications for health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 671–686. [CrossRef]

- Ghani, R.; Mullish, B.H.; McDonald, J.A.K.; Ghazy, A.; Williams, H.R.T.; Brannigan, E.T.; Mookerjee, S.; Satta, G.; Gilchrist, M.; Duncan, N.; et al. Disease Prevention Not Decolonization: A Model for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients Colonized With Multidrug-resistant Organisms. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 1444–1447. [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, P.H.; Hilpüsch, F.; Cavanagh, J.P.; Leikanger, I.S.; Kolstad, C.; Valle, P.C.; Goll, R. Faecal microbiota transplantation versus placebo for moderate-to-severe irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, single-centre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 17–24. [CrossRef]

- van Lier, Y.F., et al., Donor fecal microbiota transplantation ameliorates intestinal graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Sci Transl Med, 2020. 12(556).

- Surawicz, C.M., et al., Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol, 2013. 108(4): p. 478-98; quiz 499.

- Liu, F.; Ye, S.; Zhu, X.; He, X.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Ren, X.; et al. Gastrointestinal disturbance and effect of fecal microbiota transplantation in discharged COVID-19 patients. J. Med Case Rep. 2021, 15, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Biliński, J.; Winter, K.; Jasiński, M.; Szczęś, A.; Bilinska, N.; Mullish, B.H.; Małecka-Panas, E.; Basak, G.W. Rapid resolution of COVID-19 after faecal microbiota transplantation. Gut 2021, 71, 230–232. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: from biology to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 605–616. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.; Hock, Q.S.; Kadim, M.; Mohan, N.; Ryoo, E.; Sandhu, B.; Yamashiro, Y.; Jie, C.; Hoekstra, H.; Guarino, A. Probiotics for gastrointestinal disorders: Proposed recommendations for children of the Asia-Pacific region. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 7952–7964. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, L.; Lin, W.; Tang, W.; Chan, F.K.; Ng, S.C. Review article: Probiotics, prebiotics and dietary approaches during COVID-19 pandemic. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 187–196. [CrossRef]

- Xavier-Santos, D.; Padilha, M.; Fabiano, G.A.; Vinderola, G.; Cruz, A.G.; Sivieri, K.; Antunes, A.E.C. Evidences and perspectives of the use of probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics as adjuvants for prevention and treatment of COVID-19: A bibliometric analysis and systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 120, 174–192. [CrossRef]

- D'ETtorre, G.; Ceccarelli, G.; Marazzato, M.; Campagna, G.; Pinacchio, C.; Alessandri, F.; Ruberto, F.; Rossi, G.; Celani, L.; Scagnolari, C.; et al. Challenges in the Management of SARS-CoV2 Infection: The Role of Oral Bacteriotherapy as Complementary Therapeutic Strategy to Avoid the Progression of COVID-19. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 389. [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, G.; Borrazzo, C.; Pinacchio, C.; Santinelli, L.; Innocenti, G.P.; Cavallari, E.N.; Celani, L.; Marazzato, M.; Alessandri, F.; Ruberto, F.; et al. Oral Bacteriotherapy in Patients With COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 7, 613928. [CrossRef]

- McCarville, J.L.; Chen, G.Y.; Cuevas, V.D.; Troha, K.; Ayres, J.S. Microbiota Metabolites in Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 147–170. [CrossRef]

- Van Treuren, W. and D. Dodd, Microbial Contribution to the Human Metabolome: Implications for Health and Disease. Annu Rev Pathol, 2020. 15: p. 345-369.

- Zuo, T.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G.; Tso, E.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Chen, Z.; Boon, S.; Chan, F.K.L.; Chan, P.; et al. Depicting SARS-CoV-2 faecal viral activity in association with gut microbiota composition in patients with COVID-19. Gut 2020, 70, 276–284. [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Gao, H.; Lv, L.; Guo, F.; Zhang, X.; Luo, R.; Huang, C.; et al. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 or H1N1 Influenza. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2669–2678. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wan, Y.; Zuo, T.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhan, H.; Lu, W.; Xu, W.; Lui, G.C.; et al. Prolonged Impairment of Short-Chain Fatty Acid and L-Isoleucine Biosynthesis in Gut Microbiome in Patients With COVID-19. Gastroenterology 2021, 162, 548–561.e4. [CrossRef]

- Piscotta, F.J.; Hoffmann, H.-H.; Choi, Y.J.; Small, G.I.; Ashbrook, A.W.; Koirala, B.; Campbell, E.A.; Darst, S.A.; Rice, C.M.; Brady, S.F.; et al. Metabolites with SARS-CoV-2 Inhibitory Activity Identified from Human Microbiome Commensals. mSphere 2021, 6, e0071121. [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Hamady, M.; Yatsunenko, T.; Cantarel, B.L.; Duncan, A.; Ley, R.E.; Sogin, M.L.; Jones, W.J.; Roe, B.A.; Affourtit, J.P.; et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 2009, 457, 480–484. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.W.; Zhang, W. Current trends and challenges in the downstream purification of bispecific antibodies. Antib. Ther. 2021, 4, 73–88. [CrossRef]

- Mitragotri, S.; Burke, P.A.; Langer, R. Overcoming the challenges in administering biopharmaceuticals: formulation and delivery strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 655–672. [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, M.R.; Isabella, V.M.; Li, N.; Kurtz, C.B. Developing a new class of engineered live bacterial therapeutics to treat human diseases. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Roslan, M.A.M.; Omar, M.N.; Sharif, N.A.M.; Raston, N.H.A.; Arzmi, M.H.; Neoh, H.-M.; Ramzi, A.B. Recent advances in single-cell engineered live biotherapeutic products research for skin repair and disease treatment. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Vigouroux, A.; Rousset, F.; Varet, H.; Khanna, V.; Bikard, D. A CRISPRi screen in E. coli reveals sequence-specific toxicity of dCas9. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Crook, N.; Ferreiro, A.; Gasparrini, A.J.; Pesesky, M.W.; Gibson, M.K.; Wang, B.; Sun, X.; Condiotte, Z.; Dobrowolski, S.; Peterson, D.; et al. Adaptive Strategies of the Candidate Probiotic E. coli Nissle in the Mammalian Gut. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 499–512.e8. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Liu, C.-G.; Zang, D.; Chen, J. Gut microbiota and dietary intervention: affecting immunotherapy efficacy in non–small cell lung cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1343450. [CrossRef]

- McQuade, J.L.; Daniel, C.R.; A Helmink, B.; A Wargo, J. Modulating the microbiome to improve therapeutic response in cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e77–e91. [CrossRef]

- Gouez, M., et al., [Nutrition and physical activity (PA) during and after cancer treatment: Therapeutic benefits, pathophysiology, recommendations, clinical management]. Bull Cancer, 2022. 109(5): p. 516-527.

- Shan, G.; Minchao, K.; Jizhao, W.; Rui, Z.; Guangjian, Z.; Jin, Z.; Meihe, L. Resveratrol improves the cytotoxic effect of CD8 +T cells in the tumor microenvironment by regulating HMMR/Ferroptosis in lung squamous cell carcinoma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 229, 115346. [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, A.; Raheem, D.; Roy, P.R.; BinMowyna, M.N.; Romão, B.; Alarifi, S.N.; Albaridi, N.A.; Alsharari, Z.D.; Raposo, A. Probiotics and Plant-Based Foods as Preventive Agents of Urinary Tract Infection: A Narrative Review of Possible Mechanisms Related to Health. Nutrients 2025, 17, 986. [CrossRef]

| Target Protein/ Pathway | Function | References |

|---|---|---|

| ABHD6 | α/β-hydrolase domain 6 (ABHD6) is a lipase affecting energy metabolism. | [26] |

| HDAC6 | Histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6)re-sensitizes leptin signaling during obesity. | [27] |

| LGR4 | G-protein-coupled receptor 4 (LGR4) impacts long-chain fatty acid-absorption. | [28] |

| NK2R | Neurokinin 2 receptor (NK2R) can increase energy expenditure peripherally. | [29] |

| NMDA receptor | The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonism can treat obesity. | [30] |

| PICK1, PSD95 | Protein interacting with C kinase 1 and postsynaptic density protein-95 targeting postsynaptic glutamate receptor for obesity treatment. | [31] |

| PTER | Orphan enzyme phosphotriesterase-related (PTER) is a N-acetyltaurine hydrolase. | [32] |

| PXR | Pregnane X receptor (PXR) can regulate glycolipid metabolism. | [33] |

| SREBP2, RORγ | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2)and the retinoid acid receptor-related orphan receptor gamma (RORγ) regulate cholesterol metabolism. | [34] |

| RUVBL2 | Knockout of PVH RUVBL2 results in hyperphagic obesity. | [35] |

| Cluster of Differentiation | Efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|

| CD4 | CD4 T cells play a multiplicity of roles in protective immunity to influenza, viral antigen specificity. | [58] |

| CD8 | CD8 T cells provide broadly cross-reactive immunity and alleviate disease severity by recognizing conserved epitopes. | [61] |

| CD11 | CD11b+ cDC2 subsets present in mice regulated by IRF4 during IAV infection. | [63,64] |

| CD27 | CD45RA−CD27− effector memory-like T-cells increase in IAV- and IBV-infected patients. | [65] |

| CD38 | CD38+Ki67+CD8+ effector T cells increase in IAV infected pediatric and adult subjects. | [66] |

| CD45 | The CD45-positive macrophages expressing mCherry increase in IAV-infected patients. | [63,65] |

| CD64 | Mice lacking myeloid TBK1 showed less recruitment of CD64+SiglecF-Ly6C inflammatory macrophages. | [63] |

| CD69 | CD69+CD103+ TRM cells preferentially localized to lung sites of prior IAV infection. | [67] |

| CD103 | Vaccine can induced lung tissue-resident memory T cells expressing high levels of CD103. | [67,68] |

| CD122 | Once memory to influenza is established and enhance NF-κB signaling in T cells can increases CD122 levels. | [69] |

| Microbial metabolites | Bacteria | Efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Acetobacter and Bifidobacterium pseudolongum | Acetate can trigger antiviral immune. | [87,88] |

| Butyrate | Clostridium butyricum and Butyrivibrio | Butyrate reprograms CD8+ T cells by promoting glutamine utilization and fatty acid oxidation. | [61] |

| LPS | Gram-negative bacteria | LPS can activate the TLR4 pathwayto trigger the NF-κB signaling pathway and regulate the inflammatory response. | [40] |

| BCAA |

Prevotellacopri and Bacteroides vulgatus |

Branched-chain amino acid can induce insulin resistance. | [89] |

| Indole derivatives (e.g. IAA, IPA, 5-HIAA) | Escherichia coli, Proteus and Vibrio cholerae | They can activate the AhR. | [90] |

| 5-HT | Enterochromaffin cells produce 5-HT influencing by gut microbiota | 5-hydroxytryptaminecan regulate glucose homeostasis. | [91] |

| PGN | All species of bacteria | Peptidoglycan can activate host immunity. | [92] |

| 2-octagenoate | Blautia bacterium | 2-octagenoate can lead to liver hypertrophy, steatosis, inflammation of liver cells, and fibrosis. |

[93] |

| DAT | Clostridium orbiscindens | DAT can trigger tonic IFN signaling and regulate the phagocytic activity of macrophages. | [83] |

| TMA | Gut microbiota | Trimethylamine converted to Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) in the liver. TMAO regulates glucose metabolism and causes adipose tissue inflammation. | [94] |

| Bile acids | Clostridium scindens | BAs activate virus-induced NF-κB. | [82] |

| 18-HEPE | Clostridium strain C. butyricum | 18-HEPE activates the production of tonic IFN-λ by lung epithelial cells via GPR120, leading to enhanced resistance to influenza infection. | [95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).