Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

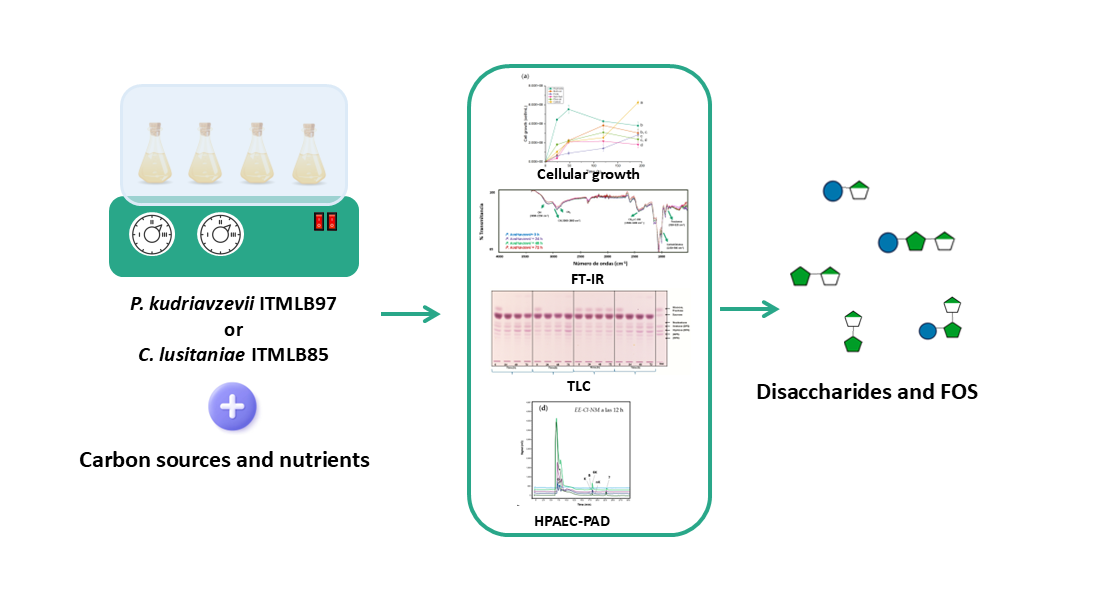

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Agave Juice Extraction

2.2. Microorganisms

2.3. Physicochemical Analysis of the Agave Juices

2.4. Yeast Growth Screening in Different Agave Juices

2.5. Effects of Sucrose Concentration on FOS Production

2.6. Surfactants Effects on FOS Production

2.7. Effects of Carbon Sources and Nutrients on FOS Production

2.8. Fructosyltransferase Activity Evaluation

2.9. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

2.10. Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) Analysis

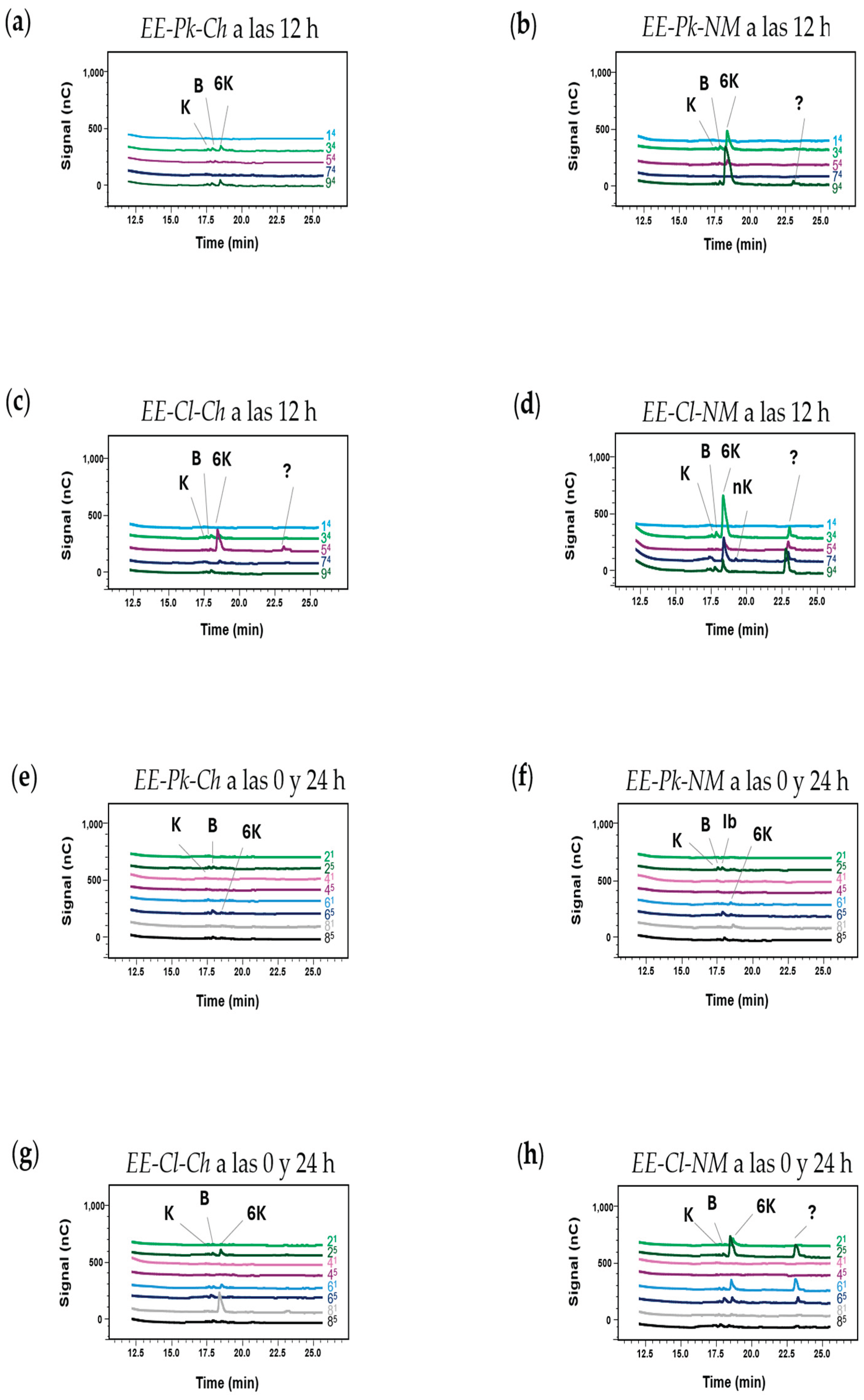

2.11. High-Performance Anion-Exchange Chromatography with Pulsed Amperometric Detection (HPAEC-PAD) Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Analysis

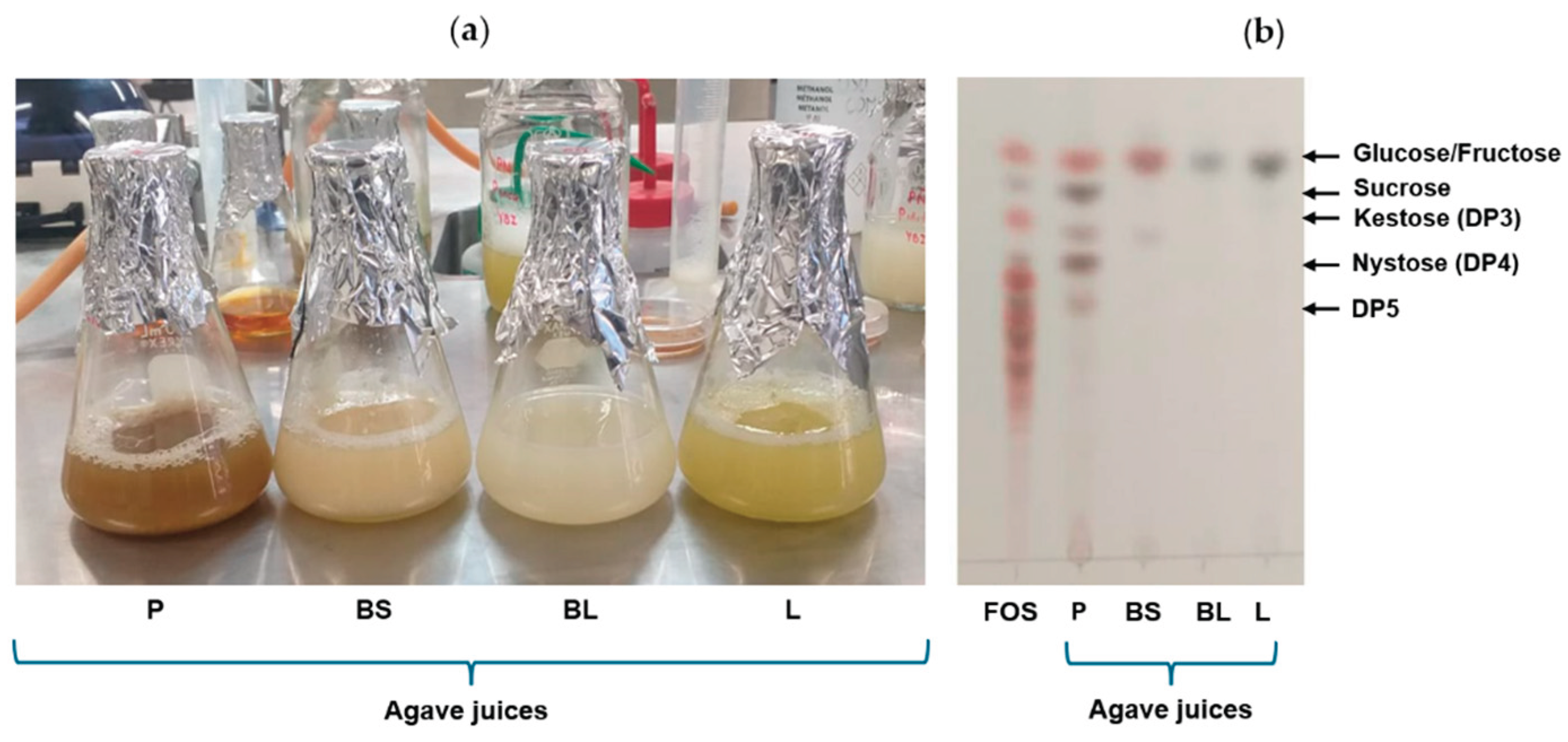

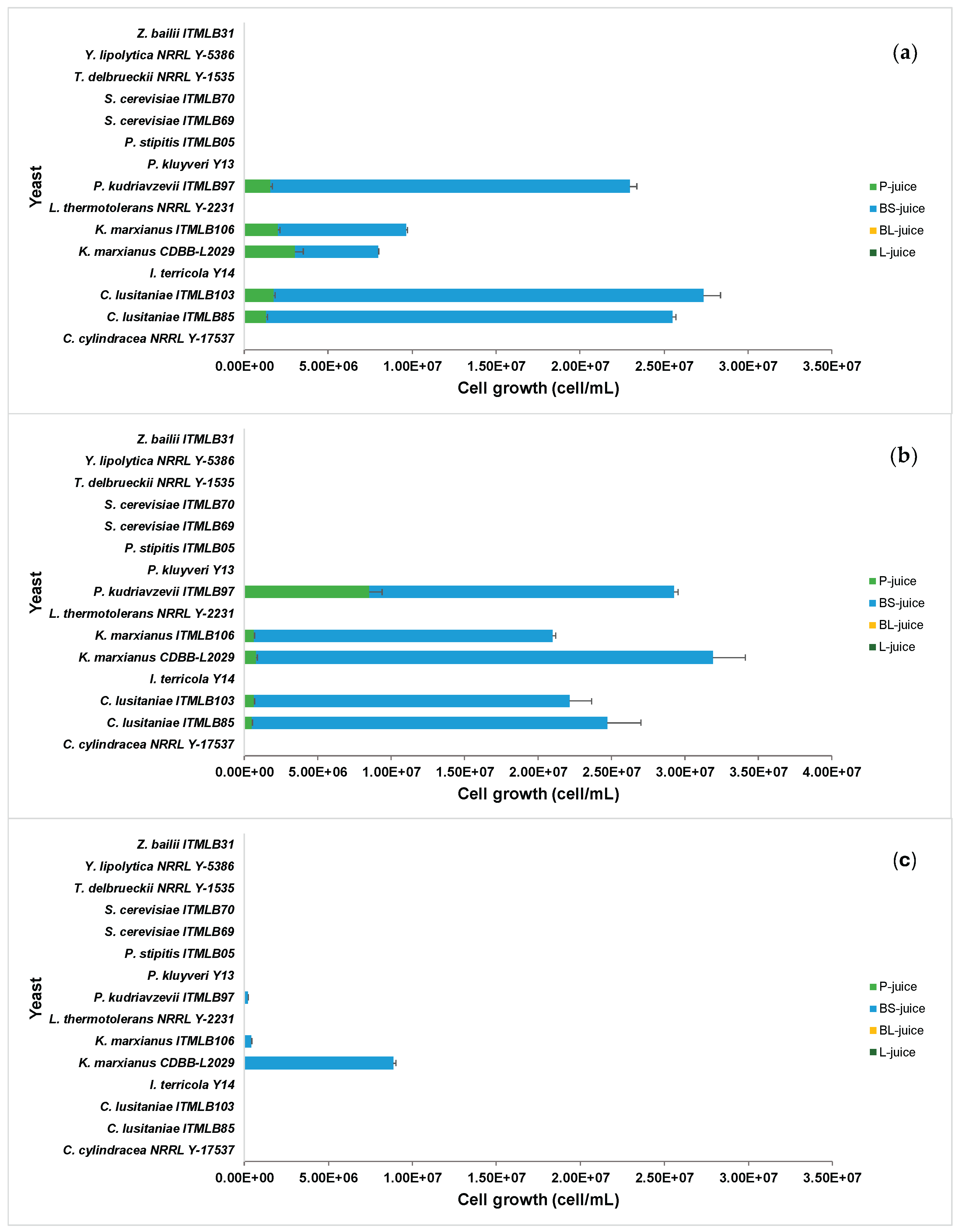

3.2. Yeast Growth Screening in Different Agave Juices

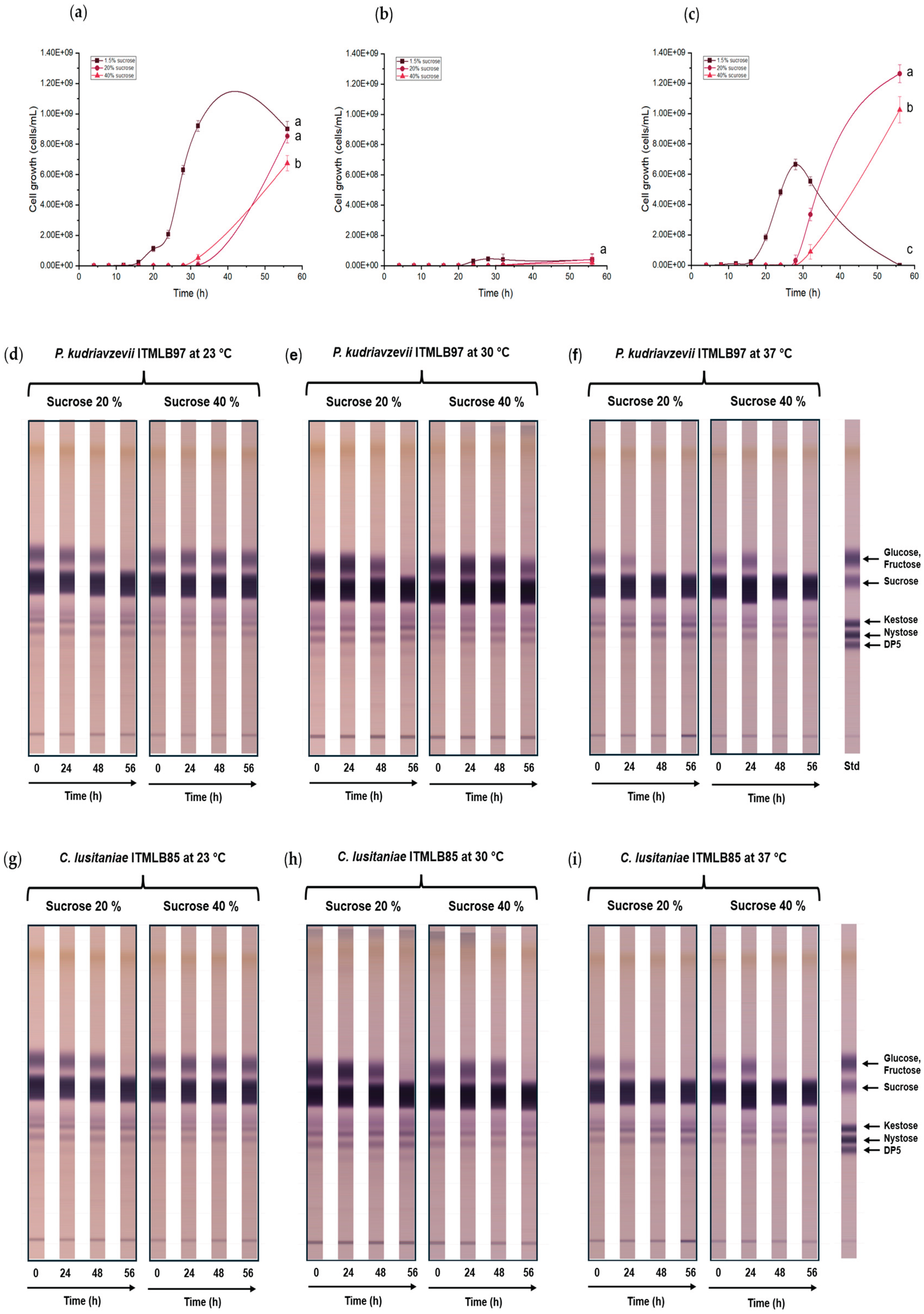

3.3. Effects of Sucrose on FOS Production

3.4. Surfactants Effects on FOS Production

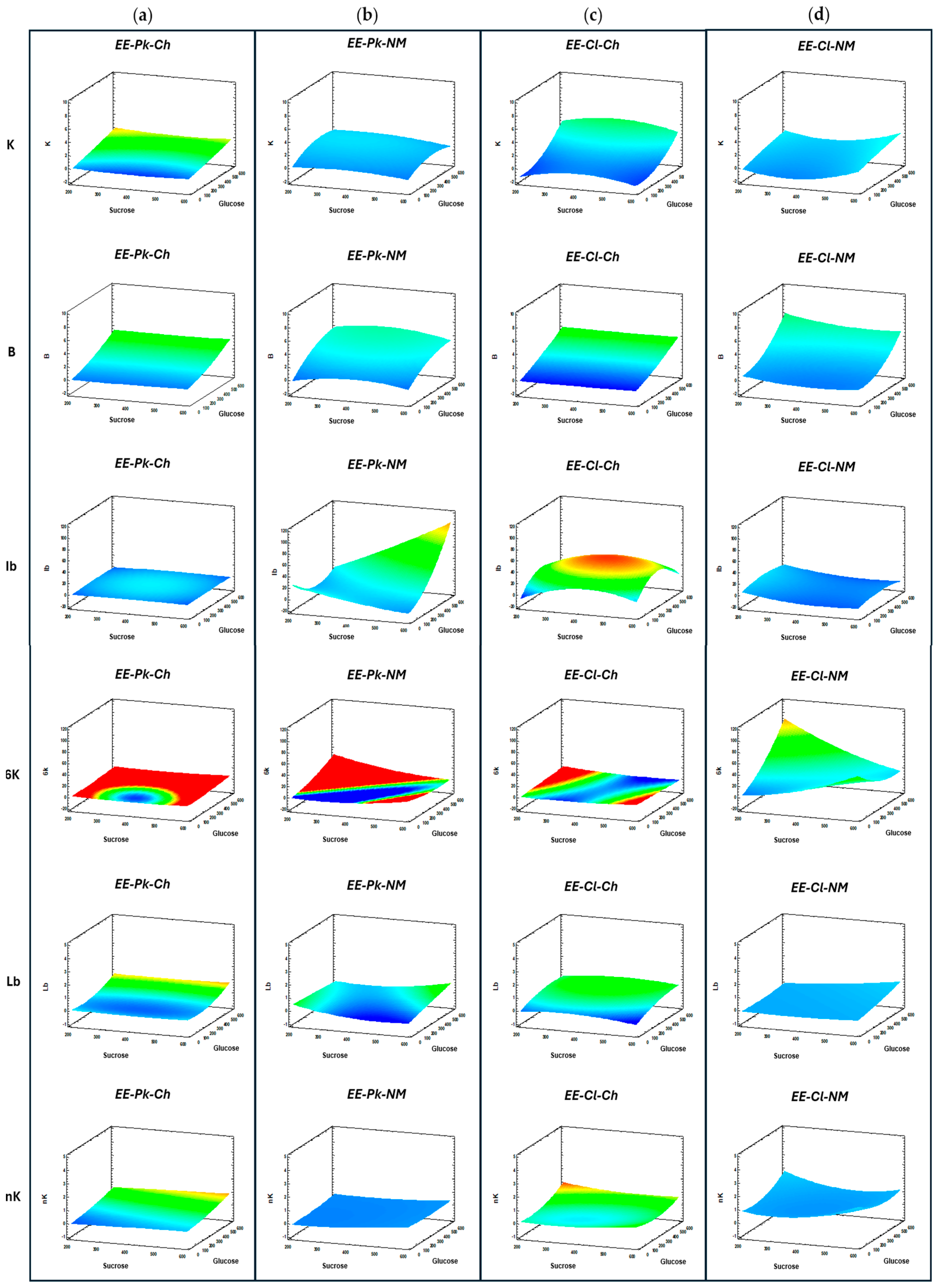

3.5. Effects of Carbon Sources and Nutrients on Yeast Growth and FOS Production

3.5. Fructosyltransferase Enzyme Activity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Abbreviations

| FOS | Fructooligosaccharides |

| DP | Degree polymerization |

| HDP | High polymerization degree |

| FTase | Fructosyltransferase |

| FFase | β-fructofuranosydase |

| 1F-FOS | Inulin type FOS |

| 6F-FOS | Levan type FOS |

| 1,6F-FOS | Graminan type FOS |

| 6G-FOS | Neo-levan type FOS |

| aFOS | Agavin-FOS |

| RSM | Response surface methodologies |

| P | Pine head |

| BS | Base of the scape |

| BL | Base of the leaf |

| L | Leaf |

| P-juice | Pine head juice |

| BS-juice | Base of the scape juice |

| BL-juice | Base of the leaf juice |

| L-juice | Leaf juice |

| TLC | Thin Layer Chromatography |

| YPD | Yeast Peptone Dextrose medium |

| YPDE | Enriched Yeast Peptone Dextrose medium |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| DNa | Sodium deoxycholate |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HPAEC-PAD | High-Performance Anion-Exchange Chromatography with Pulsed Amperometric Detection |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| PCA | Principal Components Analysis |

| OPLS | Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures |

| MIR | MID-infrared spectroscopy |

| PC | Principal Components |

| RS | Response Surface |

References

- Singh, R.S.; Singh, R.P.; Kennedy, J.F. Recent insights in enzymatic synthesis of fructooligosaccharides from inulin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 85, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banguela, A.; Hernández, L. Fructans: From natural sources to transgenic plants. Biotecnol. Apl. 2006, 23, 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte-Izquierdo, Y.; Salomé-Abarca, L.F.; González-Hernández, J.C.; López, M.G. Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) production by microorganisms with fructosyltransferase activity. Fermentation, 2023, 9, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antošová, M.; Polakovič, M. Fructosyltransferases: The enzymes catalyzing production of fructooligosaccharides. Chem. Pap. 2001, 55, 350–358. [Google Scholar]

- Straathof, A.J.; Kieboom, A.P.; van Bekkum, H. Invertase-catalyzed fructosyl transfer in concentrated solutions of sucrose. Carbohydr. Res. 1986, 146, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huazano-García, A.; López, M.G. Enzymatic hydrolysis of agavins to generate branched fructooligosaccharides (a-FOS). Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 184, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Frutos, D.; Piedrabuena, D.; Sanz-Aparicio, J.; Fernández-Lobato, M. Yeast cultures expressing the Ffase from Schwanniomyces occidentalis, a simple system to produce the potential prebiotic sugar 6-kestose. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno-Pérez, M.; Linde, D.; Fernández-Arrojo, L.; Plou, F.J.; Fernández-Lobato, M. Heterologous overproduction of β-fructofuranosidase from yeast Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous, an enzyme producing prebiotic sugars. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 3459–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huazano-García, A.; Silva-Adame, M.B.; Vázquez-Martínez, J.; Gastelum-Arellanez, A.; Sánchez-Segura, L.; López, M.G. Highly branched neo-fructans (Agavins) attenuate metabolic endotoxemia and low-grade inflammation in association with gut microbiota modulation on high-fat diet-fed mice. Foods. 2020, 9, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rosa, O.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Muñíz-Marquez, D.; Nobre, C.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N. Fructooligosaccharides production from agro-wastes as alternative low-cost source. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T. The cholesterol-lowering action of plant stanol esters. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 2109–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zeng, T.; Wang, S.E.; Wang, W.; Wang, Q.; Yu, H.X. Fructo-oligosaccharides enhance the mineral absorption and counteract the adverse effects of phytic acid in mice. J. Nutr. 2010, 26, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, G.T.; Vasconcelos, Q.D.; Aragão, G.F. Fructooligosaccharides on inflammation, immunomodulation, oxidative stress, and gut immune response: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M. Prebiotics: The concept revisited1. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 830S–837S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Molina, A.; Castillo, E.; Munguia, A.L. A novel two-step enzymatic synthesis of blastose, a β-d-fructofuranosyl-(2↔ 6)-d-glucopyranose sucrose analog. Food Chem. 2017, 227, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Nagai, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Mitamura, K.; Taga, A. Identification of a functional oligosaccharide in maple syrup as a potential alternative saccharide for diabetes mellitus patients. Int. J. Mol. 2019, 20, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raga-Carbajal, E.; López-Munguía, A.; Alvarez, L.; Olvera, C. Understanding the transfer reaction network behind the nonprocessive synthesis of low molecular weight levan catalyzed by Bacillus subtilis levansucrase. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Alonso, P.; Fernández-Arrojo, L.; Plou, F.J.; Fernández-Lobato, M. Biochemical characterization of a β-fructofuranosidase from Rhodotorula dairenensis with transfructosylating activity. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farine, S.; Versluis, C.; Bonnici, P.; Heck, A.; L'homme, C.; Puigserver, A.; Biagini, A. Application of high performance anion exchange chromatography to study invertase-catalyzed hydrolysis of sucrose and formation of intermediate fructan products. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 55, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro-Benito, M.; de Abreu, M.; Fernández-Arrojo, L.; Plou, F.J.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.; Ballesteros, A.; Polaina, J.; Fernández-Lobato, M. Characterization of a β-fructofuranosidase from Schwanniomyces occidentalis with transfructosylating activity yielding the prebiotic 6-kestose. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 132, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, S.G.; Sutherland, F.C.W.; Meyer, P.S.; Du Preez, J.C. Transport-limited sucrose utilization and neokestose production by Phaffia rhodozyma. Biotechnol. Lett. 1996, 18, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger, S.M.; Kilian, S.G.; Potgieter, M.A.; Du Preez, J.C. The effect of production parameters on the synthesis of the prebiotic trisaccharide, neokestose, by Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous (Phaffia rhodozyma). Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2003, 32, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Ning, Y.; Jin, Z.; Tian, Y. Biochemical characterization of an intracellular 6G-fructofuranosidase from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous and its use in production of neo-fructooligosaccharides (neo-FOSs). Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 1715–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorsch, J.; Castro, C.C.; Couto, L.D.; Nobre, C.; Kinnaert, M. Optimal control for fermentative production of fructooligosacharides in fed-batch bioreactor. J. Process Control. 2019, 78, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, A.; Oliveira, M.R.; Baldo, C.; Tischer, C.A.; Sartori, D.; Mantovani, M.S.; Celligoi, M.A.P.C. Production of fructooligosaccharides by Bacillus subtilis natto CCT7712 and their antiproliferative potential. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128, 1414–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, M.G.; Mancilla-Margalli, N.A.; Mendoza-Díaz, G. Molecular structures of fructans from Agave tequilana Weber var. azul. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7835–7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Marroquin, A.; Hope, P.H. Agave juice, fermentation and chemical composition studies of some species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1953, 1, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mendoza, A.J. Flora del Valle de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Agavaceae. Fascículo. 2011; 88, 1-95.

- Isabel Enríquez-Salazar, M.; Veana, F.; Aguilar, C.N.; De la Garza-Rodríguez, I.M.; López, M.G.; Rutiaga-Quinones, O.M.; Morlett-Chávez, J.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R. Microbial diversity and biochemical profile of aguamiel collected from Agave salmiana and A. atrovirens during different seasons of year. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Magueyal, F.J.; Bautista-Méndez, A.; Villanueva-Tierrablanca, H.D.; García-Ruíz, J.L.; Jiménez-Islas, H.; Navarrete-Bolaños, J.L. Novel process to obtain agave sap (aguamiel) by directed enzymatic hydrolysis of agave juice fructans. LWT. 2020, 127, 109387. [Google Scholar]

- Picazo, B.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Muñiz-Márquez, D.B.; Flores-Maltos, A.; Michel-Michel, M.R.; de la Rosa, O.; Rodriguez-Jasso, R.M.A.I.; Rodriguez, R.; Aguilar-González, C.N. Enzymes for fructooligosaccharides production: Achievements and opportunities. Enzymes in Food Biotechnology; Kuddus, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Bocco, G.; López-Granados, E.; Mendoza, M.E. La investigación ambiental en la cuenca del Lago de Cuitzeo: Una revisión de la bibliografía publicada. Contribuciones para el desarrollo sostenible de la cuenca del lago de Cuitzeo, Michoacán. 2012. 317-345.

- Alcocer, J.; Hammer, U.T. Saline lake ecosystems of Mexico. AEHMS. 1998, 1, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pantoja, M.A.; Alcocer, J.; Maeda-Martínez, A.M. On the Spinicaudata (Branchiopoda) from Lake Cuitzeo, Michoacán, México: First report of a clam shrimp fishery. Hydrobiologia, 2002, 486, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.L.C.; Bruns, R.E.; da Silva, E.G.P.; Dos Santos, W.N.L.; Quintella, C.M.; David, J.M.; de Andrade, J.B.; Breitkreitz, M.C.; Jardim, I.C.S.F.; Neto, B.B. Statistical designs and response surface techniques for the optimization of chromatographic systems. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1158, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, A.; Montazerghaem, L.; Naeimi, A.; Abhari, A.R.; Vafaee, M.; Ali, G.A.; Sadegh, H. Investigation of photocatalytic behavior of modified ZnS: Mn/MWCNTs nanocomposite for organic pollutants effective photodegradation. J Environ Manage. 2019, 247, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Yu, X.; Xu, B.; Pang, R.; Zhang, Z. 3D slope reliability analysis based on the intelligent response surface methodology. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado-Mojica, E.; López, M.G. Fructan metabolism in A. tequilana Weber Blue variety along its developmental cycle in the field. J. Agric Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11704–11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Ning, Y.; Jin, Z.; Tian, Y. Biochemical characterization of an intracellular 6G-fructofuranosidase from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous and its use in production of neo-fructooligosaccharides (neo-FOSs). Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 1715–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomé-Abarca, L.F.; Márquez-López, R.E.; Santiago-García, P.A.; López, M.G. HPTLC-based fingerprinting: An alternative approach for fructooligosaccharides metabolism profiling. CRFS. 2023, 6, 100451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappe-Oliveras, P.; Moreno-Terrazas, R.; Arrizón-Gaviño, J.; Herrera-Suárez, T.; García-Mendoza, A.; Gschaedler-Mathis, A. Yeasts associated with the production of Mexican alcoholic nondistilled and distilled Agave beverages. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-López, M.R.; Osorio-Díaz, P.; Flores-Morales, A.; Robledo, N.; Mora-Escobedo, R. Chemical composition, antioxidant capacity and prebiotic effect of aguamiel (Agave atrovirens) during in vitro fermentation. RMIQ. 2015, 14, 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz-Márquez, D.B.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Aguilar-González, C.N. Producción artesanal del aguamiel: una bebida tradicional mexicana. Rev. Cient. UadeC. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista, N.; Arias, G.C. Bromatological chemical study about the aguamiel of Agave americana L. (Maguey). Cienc. Investig. 2008.

- Chagua Rodríguez, P.; Malpartida Yapias, R.J.; Ruíz Rodríguez, A. Tiempo de pasteurización y su respuesta en las características químicas y de capacidad antioxidante de aguamiel de Agave americana L. Rev. Investig. Altoandin. 2020, 22, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascón, L.; Cruz, M.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Neira-Vielma, A.A.; Ramírez-Barrón, S.N.; Belmares, R. Effect of Ohmic Heating on Sensory, Physicochemical, and Microbiological Properties of “Aguamiel” of Agave salmiana. Foods. 2020, 9, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadez-Blanco, R.; Bravo-Villa, G.; Santos-Sánchez, N.F.; Velasco-Almendarez, S.I.; Montville, T.J. The Artisanal Production of Pulque, a Traditional Beverage of the Mexican Highlands. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 2012, 4, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland-Sutton, J. ON PULQUE AND PULQUE-DRINKING IN MEXICO. The Lancet. 1912, 179, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega-Juárez, A.D.; Meza-Espinoza, L.; García-Magaña, M.D.L.; Ortiz-Basurto, R.I.; Chacón-López, M.A.; Anaya-Esparza, L.M.; Montalvo-González, E. Aguamiel, a Traditional Mexican Beverage: A Review of Its Nutritional Composition, Health Effects and Conservation. Foods. 2025, 14, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Ríos, G.; Figueredo-Urbina, C.J.; Casas, A. Physical, chemical, and microbiological characteristics of pulque: Management of a fermented beverage in Michoacán, Mexico. Foods. 2020, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Basurto, R.I.; Pourcelly, G.; Doco, T.; Williams, P.; Dornier, M.; Belleville, M.P. “Analysis of the main components of the aguamiel produced by the maguey-pulquero (Agave mapisaga) throughout the harvest period”. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3682–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta-García, I.; González-Muñoz, F.; Elena, R.A.M.; Sánchez-Flores, A.; López Munguía, A. Evolution of fructans in Aguamiel (Agave Sap) during the plant production lifetime. Front. nutr. 2020, 7, 566950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espíndola-Sotres, V.; Trejo-Márquez, M.A.; Lira-Vargas, A.A.; Pascual-Bustamante, S. Caracterización de aguamiel y jarabe de agave originario del Estado de México, Hidalgo y Tlaxcala. IDCYTA. 2018, 3, 522–528. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar, R.C.; Perales, S.C.; Nava, C.A.; Valera, M.L.; Gomez, L.J.; Guevara, L.F.; Hernández, D.J. and Silos, H.E. Effect of aguamiel (Agave sap) on hematic biometry in rabbits and its antioxidant activity determination. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 10, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- López-Romero, J.C.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; González-Aguilar, G.A.; Peña-Ramos, E.A.; González-Ríos, H. Biological activities of Agave by-products and their possible applications in food and pharmaceuticals. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 2461–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes-Barbosa, P.M.; Pereira, T.; Aparecida, C.; da Silva Santos, F.R.; Lisbo, N.F.; Fonseca, G.G.; Leite, R.S.R.; da Paz, M.F. Biochemical characterization, and evaluation of invertases produced from Saccharomyces cerevisiae CAT-1 and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa for the production of fructooligosaccharides. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 48, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz-Márquez, D.B.; Contreras, J.C.; Rodríguez, R.; Mussatto, S.I.; Teixeira, J.A.; Aguilar, C.N. Enhancement of fructosyltransferase and fructooligosaccharides production by A. oryzae DIA-MF in Solid-State Fermentation using aguamiel as culture medium. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 213, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Pérez, M.C. “Identificación de la fructosiltransferasa involucrada en la síntesis de fructanos ramificados de plantas micropropagadas de Agave tequilana Weber var. Azul”. Tesis doctoral. Cinvestav Unidad Irapuato. 2015.

- Laouar, L.; Lowe, K.C.; Mulligan, B.J. Yeast responses to nonionic surfactants. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1996, 18, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.T.; Davey, M.R.; Mellor, I.R.; Mulligan, B.J.; Lowe, K.C. Surfactant effects on yeast cells. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1991, 13, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.; Urbaneja, M.-A.; Goñi, F.M.; Carmona, F.G.; Cánovas, F.G.; Gómez-Fernández, J.C. Kinetic studies on the interaction of phosphatidylcholine liposomes with Triton X-100. BBA–Biomembranes. 1987, 902, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanski, T.; Hofman, W.; Witanowski, M. The infrared spectra of some carbohydrates. Bull. Acad. Polon. Sci. 1959, 7, 619–624. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Applications of infrared spectroscopy in polysaccharide structural analysis: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Chem. X. 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondragón-Cortez, P.M.; Herrera-López, E.J.; Arriola-Guevara, E.; Guatemala-Morales, G.M. Application of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) in combination with Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) for rapid analysis of the tequila production process. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quím. 2022, 21, Alim2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipson, R.S. Infrared Spectroscopy of Carbohydrates: A Review of the Literature, report. United States-Government Printing Office. Washington D.C.; USA. 1968.

- Mancilla-Margalli, N.A.; López, M.G. Water-soluble carbohydrates and fructan structure patterns from Agave and Dasylirion species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7832–7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piedrabuena, D.; Míguez, N.; Poveda, A.; Plou, F.J.; Fernández-Lobato, M. Exploring the transferase activity of Ffase from Schwanniomyces occidentalis, a β-fructofuranosidase showing high fructosyl-acceptor promiscuity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2016, 100, 8769–8778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yenush, L. Potassium and sodium transport in yeast. Yeast Membr. Transp. 2016, 187–228. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.P.; Bae, J.T.; Yun, J.W. Critical effect of ammonium ions on the enzymatic reaction of a novel transfructosylating enzyme for fructooligosaccharide production from sucrose. Biotechnol. Lett. 1999, 21, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, R.M.; Walker, G.M. Influence of magnesium ions on heat shock and ethanol stress responses of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enz. Microb. Tech. 2000, 26, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltukoglu, A.; Slaughter, J.C. The effect of magnesium and calcium on yeast growth. J. Inst. Brew. 1983, 89, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.M. The roles of magnesium in biotechnology. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 1994, 14, 311–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.M.; Birch, R.M.; Chandrasena, G.; Maynard, A.I. Magnesium, calcium, and fermentative metabolism in industrial yeasts. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 1996, 54, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, E.M.; Stewart, G.G. The effects of increased magnesium and calcium concentrations on yeast fermentation performance in high gravity worts. J. Inst. Brew. 1997, 103, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, F.; Hernalsteens, S. Screening of yeast strains for transfructosylating activity. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2007, 49, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrizon, J.; Morel, S.; Gschaedler, A.; Monsan, P. Fructanase and fructosyltransferase activity of non-Saccharomyces yeasts isolated from fermenting musts of Mezcal. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EE-Pk-Ch | EE-Pk-NM | EE-Cl-Ch | EE-Cl-NM | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (g/L) | Glucose (g/L) | Glucose (g/L) | Glucose (g/L) | |||||||||

| Sucrose (g/L) | 0 | 300 | 600 | 0 | 300 | 600 | 0 | 300 | 600 | 0 | 300 | 600 |

| 200 | 1Pk-Ch | 2Pk-Ch | 3Pk-Ch | 1Pk-NM | 2Pk-NM | 3Pk-NM | 1Cl-Ch | 2Cl-Ch | 3Cl-Ch | 1Cl-NM | 2Cl-NM | 3Cl-NM |

| 400 | 4Pk-Ch | 5Pk-Ch | 6Pk-Ch | 4Pk-NM | 5Pk-NM | 6Pk-NM | 4Cl-Ch | 5Cl-Ch | 6Cl-Ch | 4Cl-NM | 5Cl-NM | 6Cl-NM |

| 600 | 7Pk-Ch | 8Pk-Ch | 9Pk-Ch | 7Pk-NM | 8Pk-NM | 9Pk-NM | 7Cl-Ch | 8Cl-Ch | 9Cl-Ch | 7Cl-NM | 8Cl-NM | 9Cl-NM |

| Juice type | pH | Density | °Brix | Moisture % | Ash % | RS (g/L) | Protein (ug/mL) | Total phenols (ug/mL GAE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 5.51 ± 0.00 a | 1.04± 0.01 a | 10.80 ± 0.10 a | 92.08 ± 0.20 a | 1.67 ± 0.02 a | 9.18 ± 0.07 a | 41.28 ± 0.05 a | 3.8 ± 0.23 a |

| BS | 5.44 ± 0.00 b | 1.03 ± 0.00 a,b | 6.50 ± 0.50 b | 96.76 ± 1.25 a | 1.24 ± 0.09 b,c | 7.35 ± 0.02 b | 35.86 ± 0.00 b | 3.53 ± 0.18 a |

| BL | 5.21 ± 0.00 c | 1.02 ± 0.01 a,b | 5.40 ± 0.30 c | 95.99 ± 0.26 a | 1.29 ± 0.02 b | 6.97 ± 0.41 a,b | 27.87 ± 0.04 c | 2.06 ± 0.06 b |

| L | 5.02 ± 0.00 d | 1.02 ± 0.01 b | 4.80 ± 0.10 c | 96.70 ± 0.16 a | 1.12 ± 0.06 c | 5.58 ± 0.18 c | 25.74 ± 0.01 d | 2.51 ± 0.31 b |

| Induction media | Optimal factors | Products generated in FOS region | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | B | Ib | 6K | Lb | nK | ||

| EE-Pk-Ch | Sucrose (g/L) | 204.43 | 600.00 | 400.00 | 600.00 | 600.00 | 600.00 |

| Glucose (g/L) | 599.96 | 599.97 | 300.00 | 600.00 | 600.00 | 600.00 | |

| Time (h) | 24.00 | 24.00 | 12.00 | 12.91 | 15.43 | 12.39 | |

| Optimal value (nC) | 2.52 | 6.07 | 1.77 | 7.46 | 0.82 | 0.92 | |

| EE-Pk-NM | Sucrose (g/L) | 200.00 | 367.50 | 600.00 | 200.00 | 200.00 | 600.00 |

| Glucose (g/L) | 437.91 | 600.00 | 600.00 | 600.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Time (h) | 24.00 | 24.00 | 21.90 | 13.21 | 23.72 | 22.32 | |

| Optimal value (nC) | 3.12 | 6.40 | 115.07 | 28.09 | 0.99 | 0.77 | |

| EE-Cl-Ch | Sucrose (g/L) | 385.84 | 600.00 | 440.27 | 200.00 | 500.12 | 200.00 |

| Glucose (g/L) | 600.00 | 599.99 | 306.21 | 600.00 | 554.65 | 598.18 | |

| Time (h) | 24.00 | 24.00 | 9.20 | 23.73 | 0.00 | 24.00 | |

| Optimal value (nC) | 9.67 | 7.10 | 51.48 | 9.55 | 0.92 | 1.74 | |

| EE-Cl-NM | Sucrose (g/L) | 599.33 | 200.20 | 200.00 | 200.00 | 596.08 | 600.00 |

| Glucose (g/L) | 600.00 | 600.00 | 300.00 | 600.00 | 599.90 | 0.00 | |

| Time (h) | 23.81 | 24.00 | 24.00 | 10.35 | 24.00 | 11.23 | |

| Optimal value (nC) | 4.25 | 8.98 | 35.97 | 91.25 | 1.21 | 1.91 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).