1. Introduction

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [

1,

2] have transformed computer vision by enabling the synthesis of high-fidelity images, finding applications in artistic content creation, augmenting data for medical imaging, and beyond. Despite these successes, GAN training remains notoriously unstable, particularly when training data are limited [

3,

4,

5]. In such cases, the discriminator rapidly overfits the small pool of real images, and its confidence separates real and generated distributions, causing the generator to receive vanishing gradients and driving mode collapse [

3]. To tackle these problems, StyleGAN2-ADA incorporates the ADA framework that applies to a diverse set of invertible, differentiable image transforms to the discriminator inputs and dynamically adjusts their strength based on the discriminator’s overconfidence. While ADA enables stable training with only a few thousand images, its reliance on a convolutional discriminator hampers its ability to model global, long-range relationships since convolutions inherently focus on local receptive fields [

3].

In parallel, Vision Transformers (ViTs) [

6] have demonstrated that modeling images as sequences of patch tokens with self-attention can capture global structure and context more effectively than CNNs [

7,

8,

9] albeit at the cost of high data requirements. Recent works such as ViTGAN [

8] and TransGAN [

7] adapt pure-transformer architectures for GANs, showing that transformers can excel generation when combined with robust regularization. In data-limited scenarios, however, these methods either lack adaptive augmentation mechanisms or struggle with the memory demands of high-resolution global attention.

This work bridges these two paradigms by integrating a multi-scale ViT discriminator into StyleGAN2-ADA’s adaptive augmentation loop. The core insight is that global self-attention naturally regularizes discriminator confidence across distant image regions, counteracting the overfitting that plagues convolutional discriminators in data-scarce settings. By uniting this with ADA’s dynamic transformations and ViT-based augmentation, along with additional differentiable augmentations and consistency regularization, we craft a discriminator that can guide the generator and enforce global coherence. We show consistent improvements in Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Inception Score (IS) by systematically evaluating the proposed framework ViT-D-StyleGAN2-ADA on FFHQ, AFHQ subsets, and CIFAR-10. Our work makes the following key contributions:

A multi-scale ViT discriminator that replaces the CNN-based discriminator of StyleGAN2-ADA. It employs efficient grid-based self-attention, effectively capturing both local textures and global image structures.

We adopt two patch-level augmentations: Patch Dropout and Patch Shuffle, that operate directly on token embeddings. These augmentations adjust dynamically based on discriminator feedback, reinforcing local detail preservation and global coherence.

Transformer-specific loss adaptations, including token-level gradient penalties (R1) and Path Length Regularization (PLR) applied directly to the ViT class token, to enhance stability and convergence.

We tailor the training recipe for data-limited regimes by incorporating relative position encoding, token-wise normalization, and ADA heuristics, stabilizing adversarial learning.

2. Related Works

GANs have been extended to semi-supervised [

12], fully supervised [

13] and reinforcement learning [

14], with success in image synthesis [

4,

15]. Key advancements include improved losses (WGAN GP [

16], non-saturating loss [

3]), architecture (StyleGAN [

17], BigGAN [

18]), and normalization (Spectral Norm [

19]). StyleGAN2 [

15] refined style-based generation with path length regularization (PLR). StyleGAN2-ADA [

3] addresses discriminator overfitting in small datasets using ADA to apply stochastic, invertible image transformations. ADA avoids issues in methods like RandAugment [

20] and consistency regularization [

11,

21] adjusting augmentation strength based on real vs fake confidence, ensuring consistent generalization across dataset sizes [

15]. It achieves state-of-the-art performance on small datasets like BRECAHAD [

22] and CIFAR-10.

To combat discriminator overfitting on small datasets, StyleGAN2-ADA [

3] introduced Stochastic Discriminator Augmentation (SDA), applying a suite of stochastic, invertible image transform pixel geometric warps, color adjustments, noise, and cutout with fixed probability p such that the discriminator never sees clean images. They further designed ADA, which monitors the discriminator’s output distribution on real samples to adjust p dynamically, removing the need for manual augmentation tuning and preventing leaks of augmentations into generated data [

3]. Other augmentation strategies, Differentiable Augmentation (DiffAug) [

10] and Balanced Consistency Regularization (bCR) [

11], apply differentiable augmentations to both real and fake images or specialized augmentations for transformers [

24,

25] have emerged, respectively, stabilizing GAN training under limited data [

9].

GANs also benefit from rapidly developing Vision Transformers [

26]. ViTGAN [

8] and TransGAN [

7] showed that pure transformer discriminators and generators can rival CNN-based GANs, with TransGAN introducing a memory-friendly pyramid transformer and grid self-attention to handle high-resolution images efficiently [

19,

27]. Yet, neither integrated adaptive augmentation nor explored tailored high-regulation datasets for transformer discriminators.

2.1. Motivation

Despite the success of StyleGAN2-ADA in curbing overfitting, its convolutional discriminator remains inherently constrained in data-scarce regimes due to a limited receptive field. In our preliminary experiment, we train three StyleGAN2-ADA models with only 10k, 5k, and 2k FFHQ images. As shown in

Figure 1, the model produces high-fidelity, diverse faces in the 10k scenario. When the training data shrinks to 5k, fine details and variability diminish. In the extreme case of 2k, although the generator reproduces local textures (e.g., pores, hairs), it cannot maintain the overall structure and proper alignment of the eyes. These patterns, together with the collapse of jaw symmetry, indicate memorization of local patterns rather than learning holistic geometry, ultimately leading to mode collapse.

Formally, let

be an image. A CNN discriminator

bases its decision on features extracted with small kernels. As a result, the receptive field of

is typically limited (compared to the resolution of

X). In contrast, a ViT discriminator computes global self-attention over non-overlapping

patches:

Then,

with

. Every patch attends globally, so misalignment in any region produces corrective gradients across all patches.

By integrating this global mechanism into ADA’s dynamic augmentation loop, we extend ADA’s non-leaking stochastic transforms with two operations: patch dropout (randomly masking entire ViT patches) and patch shuffle (permuting patch positions), to complement pixel-level and geometric augmentations. We enforce local texture fidelity and coherent global structure, preventing mode collapse even with a few thousand training images.

3. Research Methodology

As shown in

Figure 2, our framework maintains StyleGAN2’s style-based convolutional generator [

3] while introducing three major innovations: (1) a multi-scale ViT discriminator with efficient grid self-attention [

7] (2) an augmented pipeline combining patch-level augmentation, DiffAug [

10], bCR [

11], in ADA augmentation pipeline, (3) loss adaptations tailored to transformer embeddings and global tokens. We used FID [

3] and IS [

3] to evaluate our model’s performance. FID compares generated and real-image feature distributions in the inception space, which is sensitive to mode collapse, and IS gauges image diversity or quality via conditional and marginal label distributions.

3.1. Augmentation Pipeline

We begin with SDA [

3], applying 18 invertible, differentiable transforms such as pixel (flips, rotations, translations), geometric (scaling, shifts), color (brightness, contrast, hue), noise injection, and cutout, each with probability

p as shown in

Figure 3. In addition, we employed DiffAug [

10], which includes differentiable transformations (color, translation, cutout) to real and fake images, promoting gradient flow and reducing mode collapse. Additionally, bCR [

11] penalizes the discriminator for inconsistency across augmentation pairs, promoting invariance to benign transforms while ensuring the discriminator focuses on meaningful content.

Patch-Level Augmentations: Transformer architectures, though initially designed for language processing, have demonstrated their value in vision applications thanks to their self-attention mechanism [

6]. Unlike text, visual inputs typically exhibit high levels of redundancy. In this work, we show that vision transformers can be trained effectively using only a subset of image patches by employing two patch-level augmentation techniques—Patch Dropout [

28] and Patch Shuffle [

29]—thereby reducing both memory usage and computational cost without sacrificing performance.

Patch Dropout randomly eliminates a fraction of image tokens at the input level. Specifically, prior to feeding patch embeddings into transformer blocks, a subset of tokens is arbitrarily sampled and removed, while positional embeddings are preserved. This method leverages spatial redundancy in image data, compelling the discriminator to infer global structure from incomplete observations, thereby enhancing generalization,

Patch Shuffle randomly rearranges the positions of patch embeddings within the image. Although this increases training data variability, it introduces a potential bias due to the altered data distribution. Consequently, Patch Shuffle is applied selectively and sparingly across layers, balancing the bias-variance tradeoff and promoting robust feature extraction by forcing the discriminator to recognize global coherence amidst shuffled spatial information,

To avoid augmentation leakage, we follow StyleGAN2-ADA’s approach, ensuring transformations with

p are non-exploitative for the generator. We adapt the augmentation intensity on-the-fly in response to the discriminator’s confidence level: increase

p if overfitting occurs and decrease p vice versa, ensuring balanced augmentation for high-quality image generation [

3].

3.2. CNN-Based Generator

We follow the StyleGAN2-ADA Generator, which transforms a latent vector

and an optional conditioning label

into style vectors w. Then progressively builds an image from low to high-resolution

using modulated convolution, noise injection, and ToRGB layers [

15,

17]. PLR ensures stable latent mapping. The design promotes disentanglement in the latent space and allows fine-grained control over synthesis at each resolution level.

3.3. VIT-Based Discriminator

The discriminator’s core responsibility is differentiating real images from generated ones. Unlike typical classification tasks focusing primarily on semantic distinctions, the discriminator emphasizes detailed visual artifacts indicative of authenticity. To optimize performance, the input images are segmented into patch tokens, analogous to “words” in natural language processing [

30]. This tokenization allows the discriminator to focus on local visual cues effectively.

The choice of patch sizes critically affects performance. Larger patches preserve high-level semantic structures but compromise low-level texture details, while smaller patches enhance detail retention but significantly increase computational demands due to longer token sequences. To balance this trade-off, we employ a multi-scale discriminator, drawing inspiration from CNNs’ ability to operate at multiple resolutions [

3,

23].

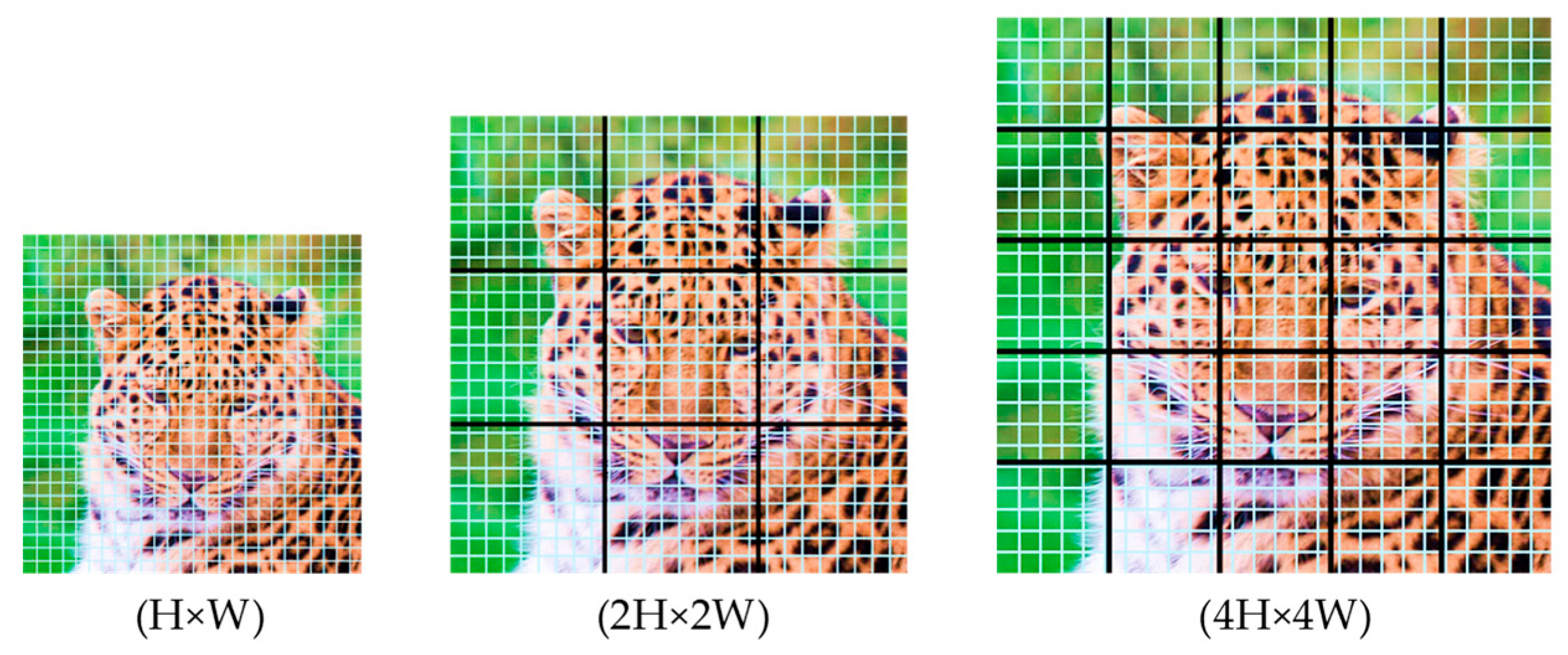

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the multi-scale discriminator systematically processes patches at varying scales [

7]. Initially, input images

are divided into three sequences using patch sizes

P, 2P, and

4P. Each sequence undergoes a linear transformation to obtain embeddings with dimensions proportional to their patch scale:

,

and

respectively. Combined with positional encoding, these embeddings feed into successive stages of transformer blocks, progressively capturing hierarchical visual representations [

6].

Between each stage, sequences are reshaped into two-dimensional feature maps and downsampled via Average Pooling, constructing a pyramid-shaped feature hierarchy. Post-transformer block processing appends a learnable classification token, which undergoes a final classification head to produce the real or fake prediction.

For computational efficiency, We utilize grid-based self-attention by partitioning feature maps into distinct, non-overlapping blocks, as shown in

Figure 5, restricting attention computations within each grid. Standard global self-attention is retained at lower resolutions to maintain global context coherence. This hybrid attention mechanism ensures effective local and global feature integration, outperforming conventional efficient attention approaches in generative modeling tasks.

The comprehensive design of our ViT-based discriminator, including multi-scale processing, grid self-attention, and transformer-specific regularization, provides robust adversarial feedback essential for stable GAN training under data-limited scenarios

3.4. Training Protocol

To stabilize training and reduce the data-hungry nature of transformer discriminators, we integrate techniques from TransGAN [

7] and StyleGAN2-ADA [

3]:

Relative Position Encoding: Instead of fixed or learnable absolute position embeddings, we apply relative position encoding [

26,

33,

34,

35] which captures token relationships via pairwise offsets, enhancing performance on high-resolution tasks,

Modified Normalization: We use token-wise scaling inspired by Local Response Normalization [

26,

36] which avoids learned affine shifts and stabilizes training [

37,

38] improving model stability and lowering FID scores,

3.5. Loss Functions and Modifications

The StyleGAN2 loss function includes a non-saturating logistic loss, an R1 penalty for the discriminator, and PLR for the generator [

39]. The discriminator loss is modified with the addition of an R1 penalty (gradient penalty for real images) [

16,

17,

40] and a PLR that controls the generator’s smooth latent-to-image mapping. The modified discriminator loss is:

here,

D(x) extracts patch embeddings before classification, and

GP(ϕ) controls the R1 penalty, set to values such as 10 for FFHQ, AFHQ and 7.8 for CIFAR-10. Through gradient regularization applied at the embedding level, we constrain the discriminator’s sensitivity to global feature representations, thereby mitigating its propensity to degenerate toward high-frequency noise under data scarcity constraints.

For PLR, we adapt it to operate on the class token rather than pixel outputs:

where

tracks the moving average of gradient magnitudes. By focusing PLR on the class token, We synchronize the generator’s updates with the discriminator’s overall assessment, enhancing latent-to-feature mapping and improving sample diversity. These modifications ensure that the CNN generator and ViT discriminator co-adapt symbiotically, balancing fine-grained synthesis with robust global critique.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

We implement our model in PyTorch 1.7.0 with CUDA 11.8 on dual NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPUs. Training budgets are 25K kimg for FFHQ (5K/10K subsets) and AFHQ (Cat, Dog, Wild; ∼5K each), and 100K kimg for CIFAR-10 (50K images). All images are downsampled with a box filter, zip-archived, and normalized to [–1, 1].

We train with a batch size of eight images per GPU. The generator is optimized with a learning rate of 2.5e-3; the transformer discriminator optimizer is Adam with a learning rate of 1e-4 for face/animal datasets and 1e-3 for CIFAR-10, with weight decay 0.01. ADA’s heuristic target p=0.6; DiffAug and bCR follow default operator sets. We measure the realism of generated images via the FID across all datasets and IS on CIFAR-10.

4.2. Comparison of Results on Small-Scale Datasets

All baseline models are trained using their official code under our evaluation protocol.

Table 1 reports FID scores for StyleGAN2-ADA [

3] and our ViT-D-based variants on low-shot subsets of FFHQ and AFHQ. On FFHQ-5k, StyleGAN2-ADA attains an FID of 10.96, while replacing its discriminator with ViT-D reduces this to 10.69; adding DiffAug [

10] slightly degrades performance to 11.02, whereas incorporating bCR [

11] yields the best result of 10.13. A similar pattern emerges on FFHQ-10k, where the baseline’s FID of 8.13 improves to 7.87.

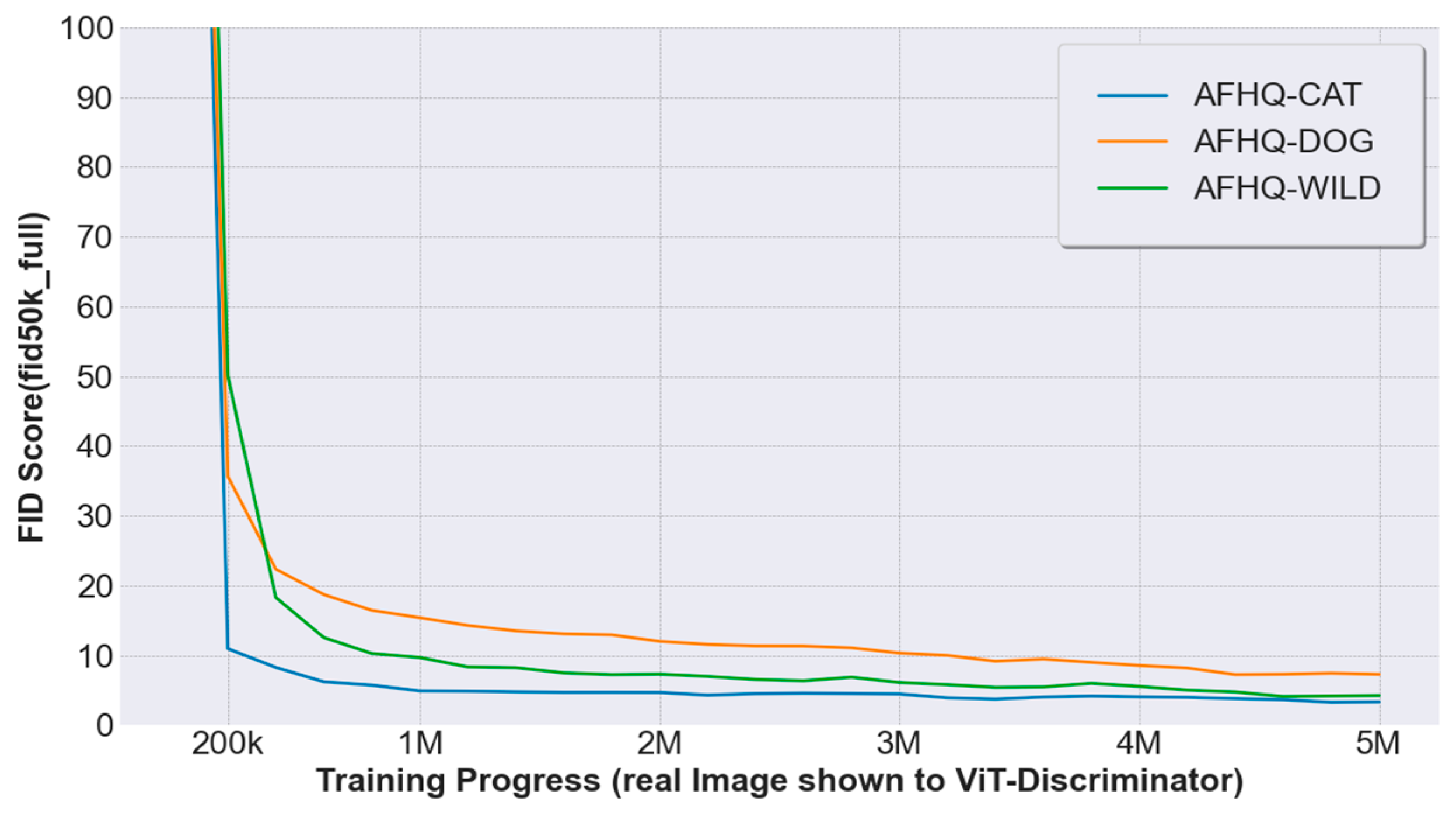

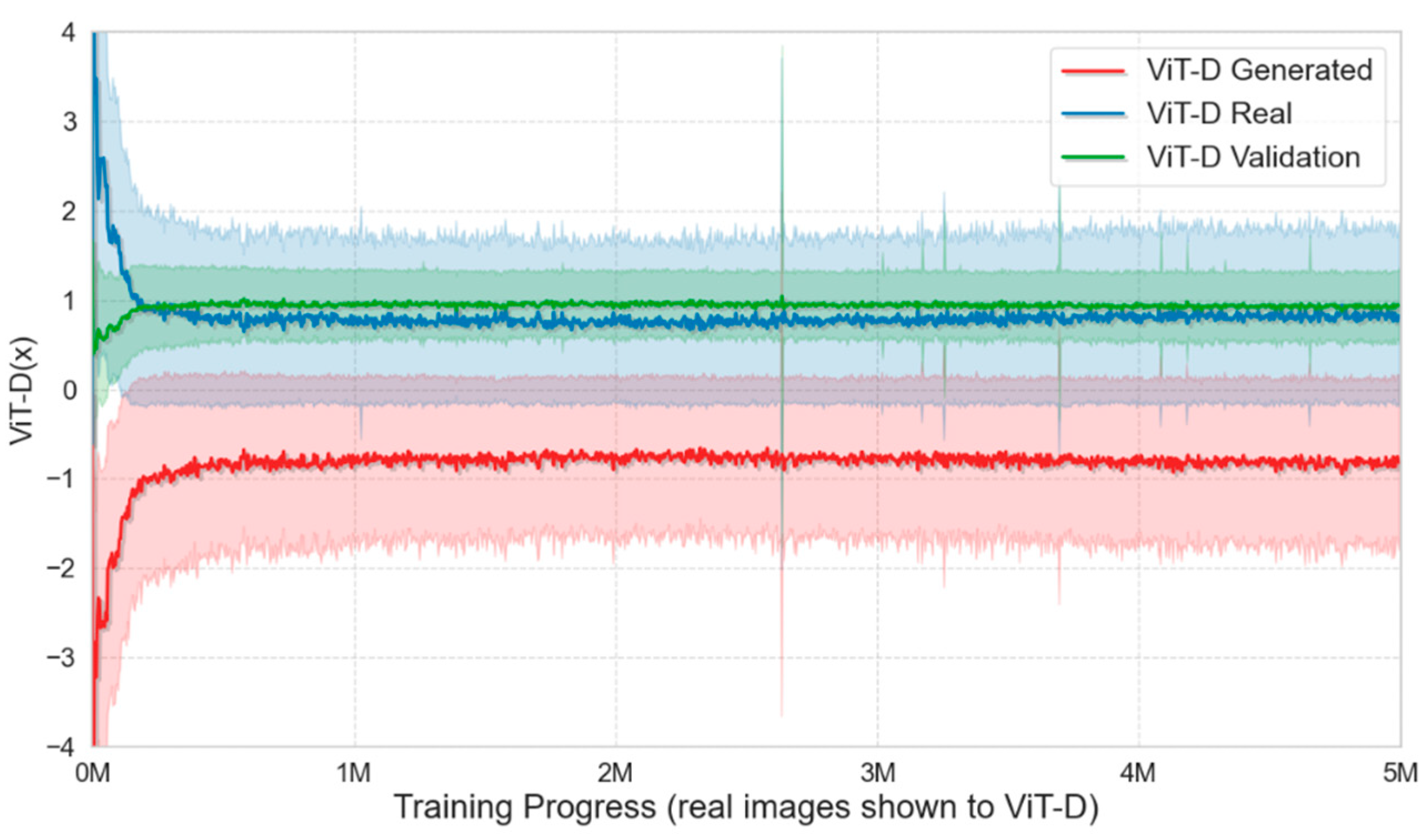

With ViT-D (DiffAug again showing a minor regression to 10.11). On the AFHQ, our best-performing configuration (ViT-D + bCR) shows a clear advantage on AFHQ-Dog (5.81 vs. 7.40), and comparable performance on AFHQ-Wild and AFHQ-Cat. These results demonstrate that our ViT-D discriminator smooth training stability shown in

Figure 6, especially when paired with batch-consistency regularization, consistently enhances sample quality in data-scarce scenarios.

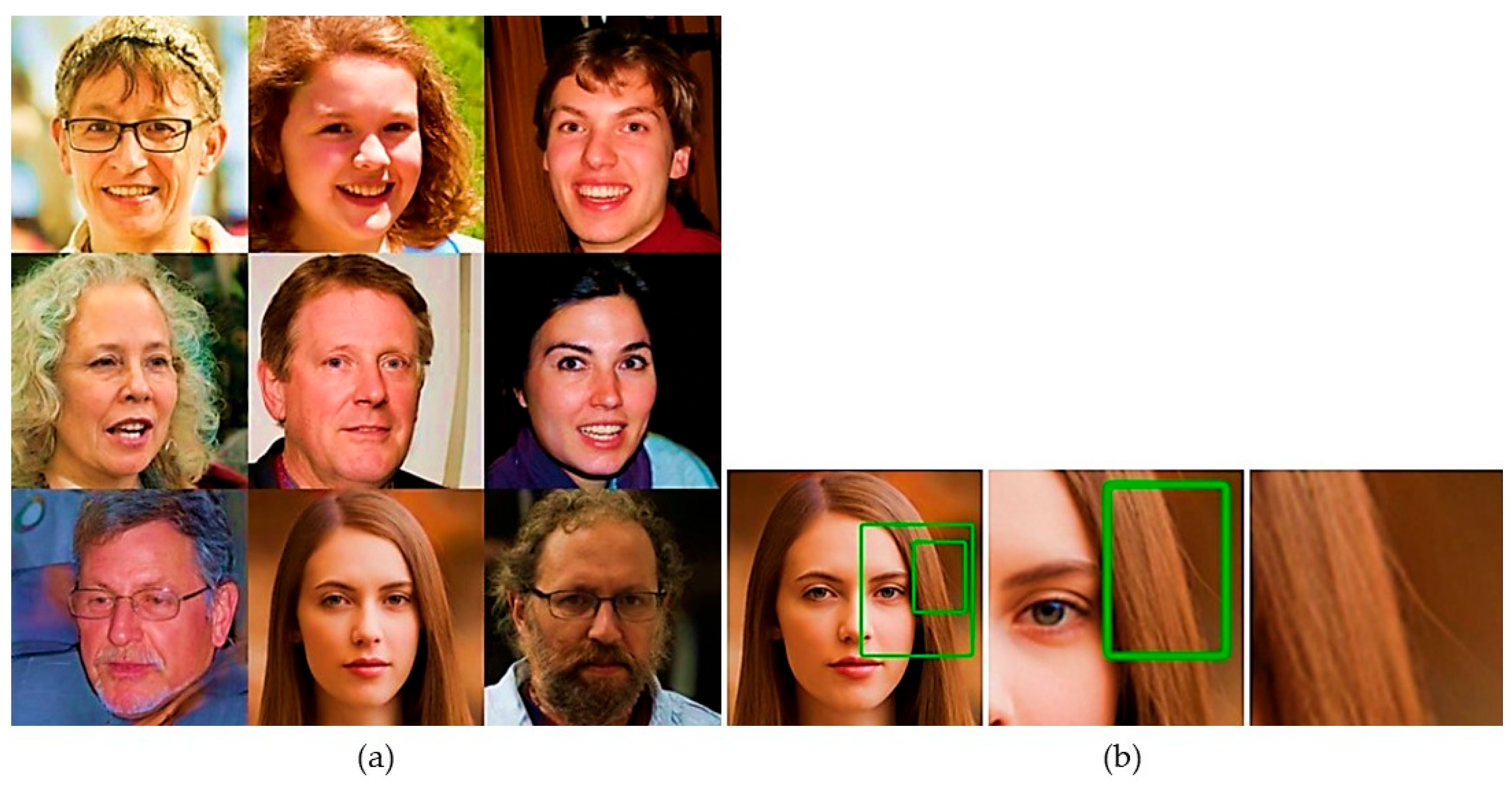

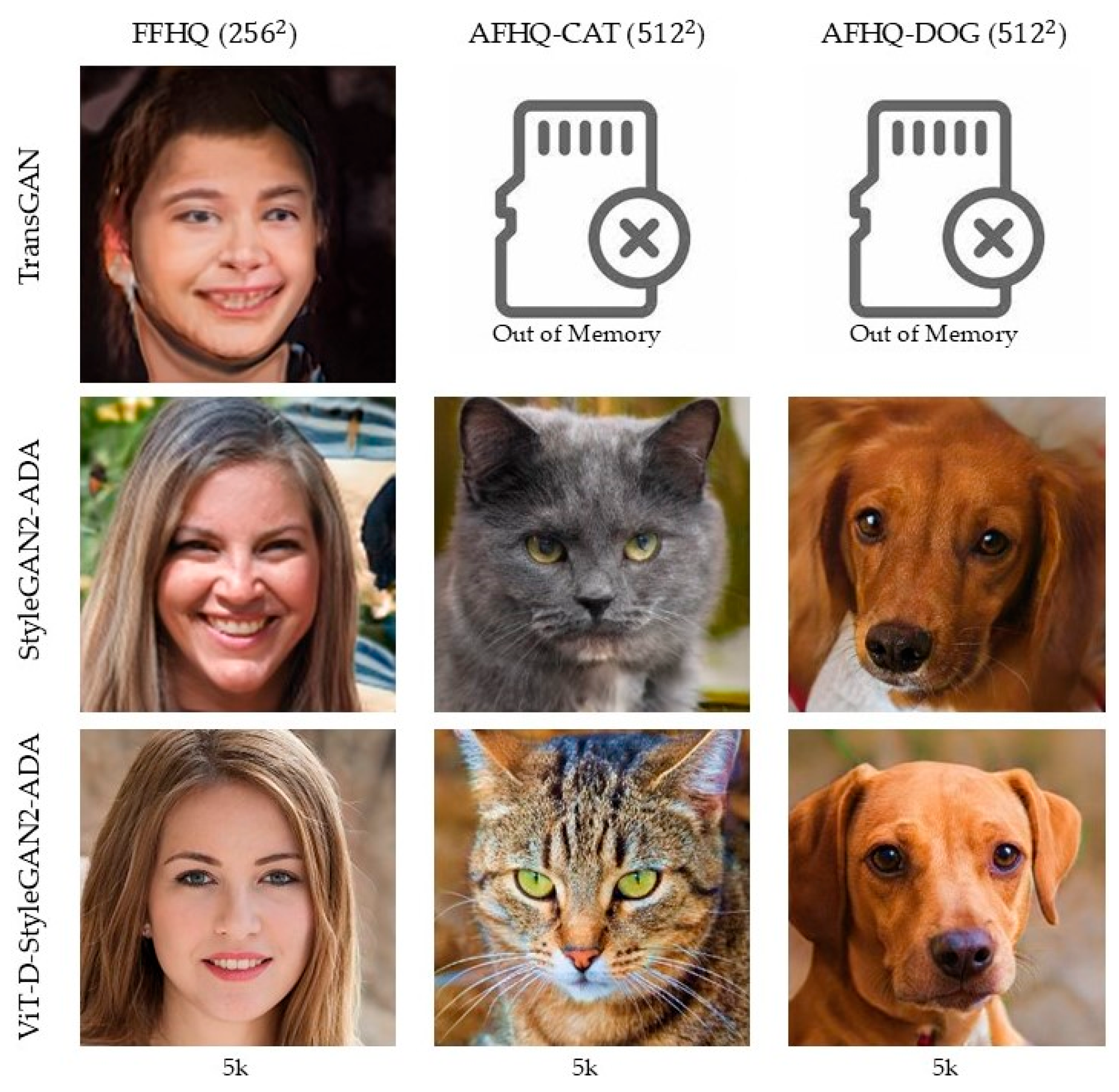

As shown in

Figure 7, the samples generated for FFHQ dataset by our ViT-D-StyleGAN2-ADA suggest that the model produces well-structured faces, aligned eyes, and symmetrical jaws. This likely stems from ViT’s global self-attention mechanism, which simultaneously models local details and overall context. Our approaches seem to help prevent mode collapse, enhancing diversity. The close-up crops highlight the model’s ability to capture fine details, such as sharp eyelashes, realistic skin textures, and individual hair strands. These observations indicate that integrating ViT with StyleGAN2-ADA can contribute to achieving both high fidelity and variability, even under constrained-data training.

Table 2 summarizes the performance of representative GAN architectures on CIFAR-10, reporting FID and IS, where lower FID and higher IS indicate better sample quality and diversity. Among the established models, StyleGAN2-ADA achieves an FID of 4.76 and an IS of 9.98; ViTGAN [

8] records 5.03 and 9.43, respectively; TransGAN [

7] yields 8.96 and 8.34; ProGAN attains 15.88 and 8.62; BigGAN reports 14.32 and 9.31; and FQ-GAN achieves 5.72 and 8.53. By replacing the convolutional discriminator in StyleGAN2-ADA with our ViT-based discriminator, we reduce FID to 3.57 while raising IS to 10.68.

When combined only with DiffAug, our ViT-D variant outperforms the baseline (FID = 4.11, IS = 9.93). Finally, integrating bCR alongside ViT-D yields the best results. An FID of 3.01 and an IS of 10.97 demonstrate that our hybrid discriminator and regularization scheme substantially improve generation quality and sample diversity over both CNN- and transformer-only approaches.

4.3. Ablation Studies

We perform comprehensive ablation experiments to evaluate the impact of each element in our proposed approach, as summarized in

Table 3. The studies employed datasets including FFHQ and AFHQ subsets and evaluated performance using FID, where lower values indicate better results.

Initially, the baseline StyleGAN2-ADA achieved FID scores of 8.13, 3.41, 7.40, and 3.55 for FFHQ, AFHQ WILD, AFHQ DOG, and AFHQ CAT, respectively, with an average score of 5.62 across all datasets.

Introducing the ViT-D-StyleGAN2-ADA(+ViT-D) improved the FID scores across multiple datasets: notably reducing the FFHQ score to 7.87, AFHQ DOG to 6.35, and AFHQ CAT to 3.29. However, there was a slight increase in the AFHQ WILD score to 4.12, resulting in an overall improvement to an average FID of 5.41.

When DiffAug is incorporated with + ViT-D, the results were unexpectedly weaker, with higher FID scores of 10.11 (FFHQ), 4.98 (AFHQ WILD), 6.84 (AFHQ DOG), and 4.78 (AFHQ CAT), leading to an increased average FID of 6.68. This indicates that DiffAug alone may introduce excessive augmentation leading to performance degradation.

In contrast, adding +bCR alongside the ViT-D resulted in substantial improvements, yielding FID scores of 7.92 (FFHQ), 3.23 (AFHQ WILD), 5.81 (AFHQ DOG), and 3.12 (AFHQ CAT). The average FID notably decreased to 5.10, underscoring the effectiveness of combining ViT with bCR for maintaining a favorable trade-off between augmentation and regularization.

Overall, The ablation experiments unequivocally show the effectiveness of our ViT-based discriminator when enhanced with bCR, confirming the importance of carefully selected augmentations and transformer-specific regularizations in achieving optimal performance under limited-data conditions.

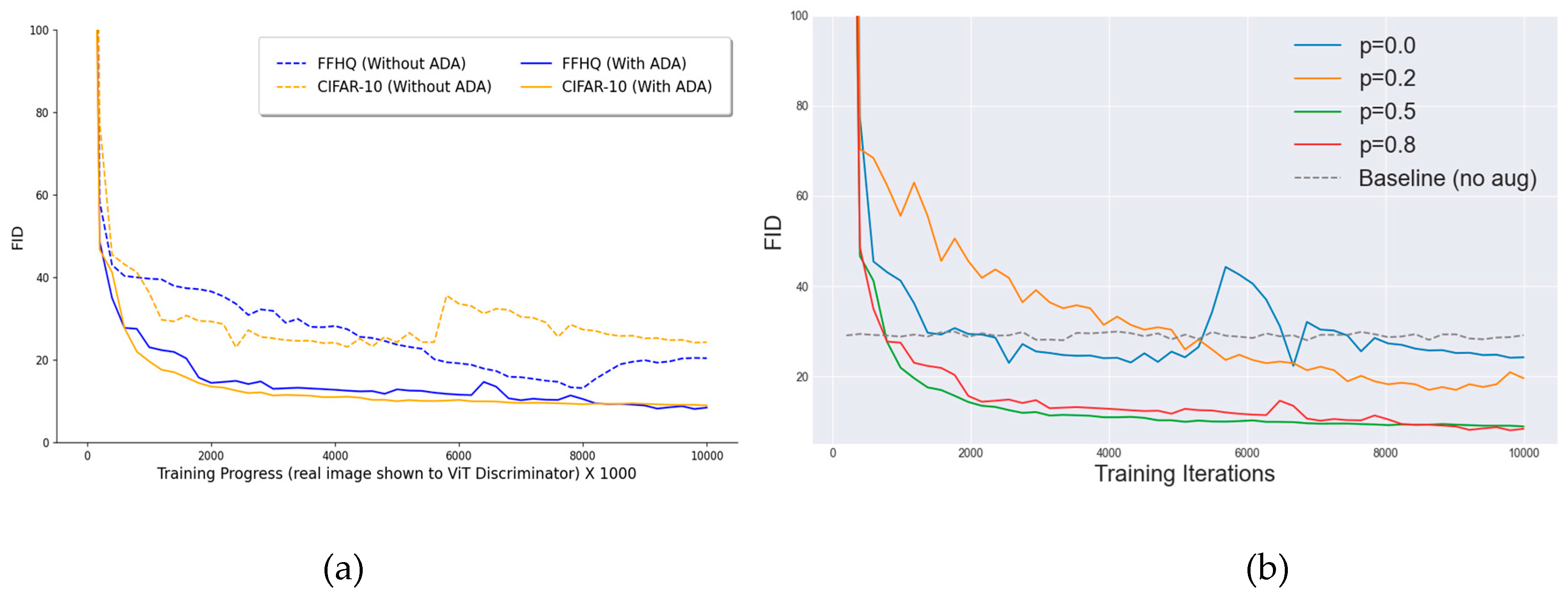

4.4. Training Observations and Augmentation Impact

We systematically explore the effect of different augmentation strengths on FFHQ and CIFAR-10. The ADA markedly enhanced our proposed model’s performance and training stability across multiple datasets. Without ADA exhibited significant challenges, which result in significant overfitting and erratic training behavior, as illustrated in

Figure 8(a).

Figure 8(b) illustrates augmentation Impact of

p, low augmentation

p=0.2 FID goes down to 17.0, while more substantial augmentation

p=0.5 yields FID = 8.94. Extreme augmentation

p=0.8 marginally improves to FID = 8.09 but risks leakage artifacts (e.g., misoriented outputs) as predicted by non-leaking transform theory [

4]. In contrast, ADA dynamically adjusts p to hover around 0.5, maintaining optimal augmentation throughout training and avoiding performance regressions.

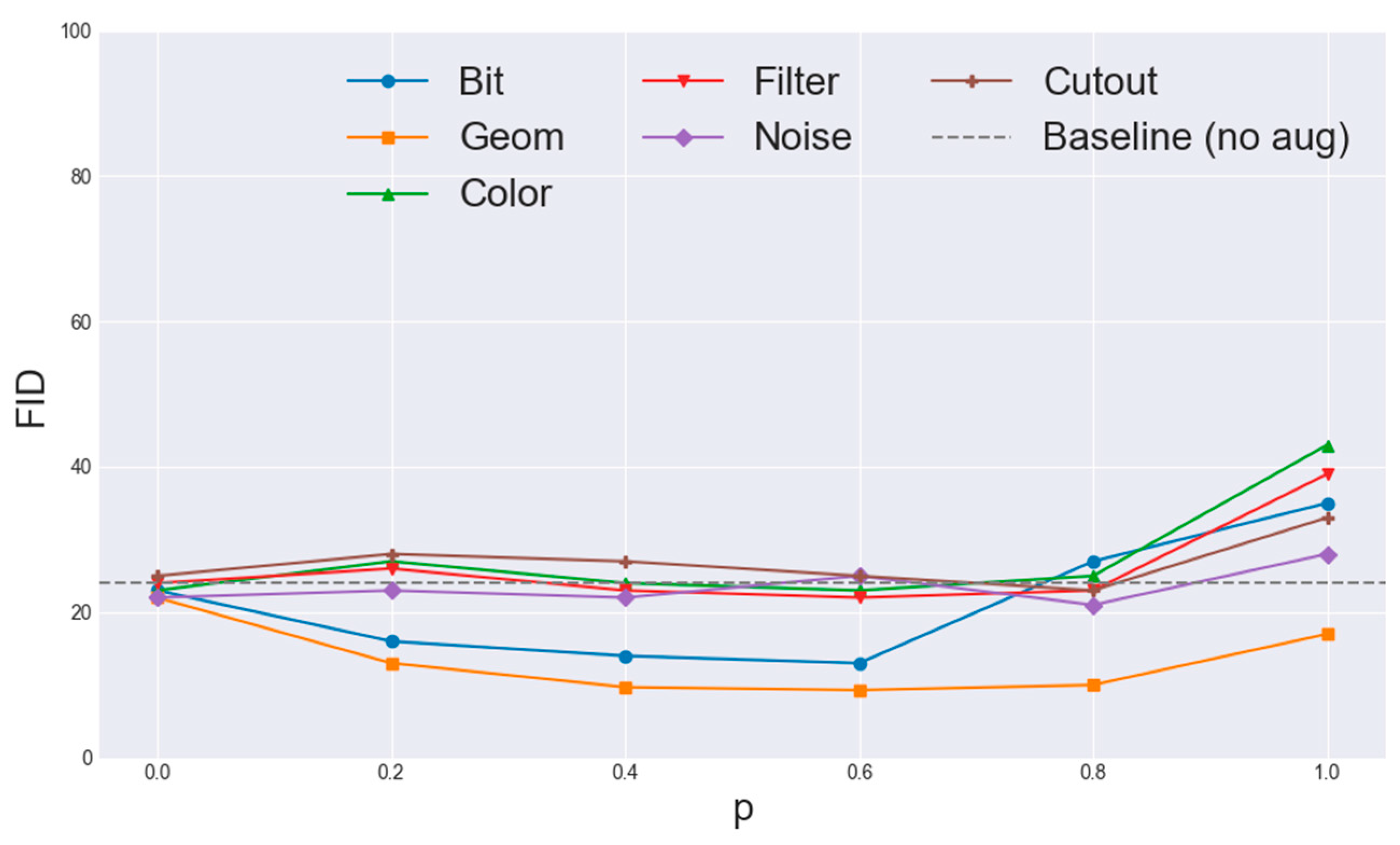

Further analysis shows in

Figure 9, that geometric transforms (rotations, translations) and color perturbations contribute most to FID reduction, while heavy filtering, noise, and cutout offer diminishing returns mirroring findings in StyleGAN2-ADA [

4]. These insights guided our selection of augmentation subsets for bCR and DiffAugment, ensuring maximal benefit without leakage.

4.5. Loss Function and Energy Consumption

Figure 10 shows that the proposed loss function effectively aligns the CNN-based generator with the ViT-based discriminator, leveraging CNN’s strong inductive biases for hierarchical feature and texture synthesis while capitalizing on ViT’s global self-attention. PLR is tailored to center on the ViT’s class token rather than pixel gradients and R1 regularization was adapted to work on token embeddings, ensuring robust generalization without sacrificing critical global features.

Computational resources: both their availability and cost, along with the energy they consume, play a decisive role in shaping research agendas and determining real-world feasibility. In

Table 4, we present a comprehensive account of our project’s demands in terms of GPU usage and electricity consumption. We ran our experiments on dule RTX 3090 GPU. Power measurements were conducted in accordance with the Green500 protocol, following the precedent set by Karras et al. [

3]. Overall, our work expended roughly 8.96 MWh of electricity. Notably, nearly half of that energy was devoted to the early stages of exploration and conceptual development, before formalizing the paper. It may shows that, ViT-D Based StyleGAN2-ADA itself imposes negligible additional cost on the training of an individual model.

5. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that substituting StyleGAN2-ADA’s CNN discriminator with a Vision Transformer enhanced by patch-level dropout and shuffling, an adaptive augmentation schedule, and transformer-specific regularizations, substantially improves few-shot image synthesis (see

Figure 11). Empirical results on FFHQ, AFHQ (Cat, Dog, Wild) and CIFAR-10 reveal FID reductions of up to 32 % and stronger Inception Scores than both the original ADA baseline and recent transformer-only GANs, alongside qualitatively sharper details, enhanced global coherence, and diminished mode collapse. The core contributions include (1) a memory-efficient, multi-scale ViT discriminator seamlessly integrated into the ADA loop; (2) a non-leaking augmentation pipeline combining pixel-, patch-, and semantic-level transforms; and (3) transformer-aware loss adaptations that stabilize training and preserve latent–image smoothness. Future extensions toward linear-time attention, self-supervised discriminator pre-training, and meta-learned augmentation promise to broaden applicability to higher resolutions and diverse low-data domains.

Author Contributions

The work presented here carried out in collaboration among all authors. Conceptualization, M.M.R.; methodology, M.M.R.; supervision, B.C. and H.Z.; visualization, M.M.R.; writing—original draft, M.M.R.; writing—review and editing, B.C. and H.Z. Finally, all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset can be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all individuals and institutions that contributed to the success of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author reported no potential conflict of interest.

References

- Jiang, Y.; Gong, X.; Liu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, C.; Shen, X.; Yang, J.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Z. EnlightenGAN: Deep light enhancement without paired supervision. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 2340–2349. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27.

- Karras, T.; Aittala, M.; Hellsten, J.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Training generative adversarial networks with limited data. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 12104–12114.

- Showrov, A.; Aziz, M.; Nabil, H.; Jim, J.; Kabir, M.; Mridha, M.; Asai, N.; Shin, J. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) in medical imaging: Advancements, applications, and challenges. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 35728–35753. [CrossRef]

- Arjovsky, M.; Bottou, L. Towards principled methods for training generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2017.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; Uszkoreit, J. An image is worth 16×16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2021. arXiv:2010.11929.

- Jiang, Y.; Chang, S.; Wang, Z. TransGAN: Two pure transformers can make one strong GAN, and that can scale up. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 14745–14758.

- Lee, K.; Chang, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, H.; Tu, Z.; Liu, C. ViTGAN: Training GANs with vision transformers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022.

- Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Herranz, L.; van de Weijer, J.; Gonzalez-García, A.; Raducanu, B. Transferring GANs: Generating images from limited data. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2018; pp. 218–234.

- Zhao, S.; Liu, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Han, S. Differentiable augmentation for data-efficient GAN training. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 7559–7570.

- Zhao, Z.; Singh, S.; Lee, H.; Zhang, Z.; Odena, A.; Zhang, H. Improved consistency regularization for GANs. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021; Volume 35, No. 12.

- Salimans, T.; Goodfellow, I.; Zaremba, W.; Cheung, V.; Radford, A.; Chen, X. Improved techniques for training GANs. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29.

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134.

- Ho, J.; Ermon, S. Generative adversarial imitation learning. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29.

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aittala, M.; Hellsten, J.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Analyzing and improving the image quality of StyleGAN. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 8107–8116.

- Gulrajani, I.; Ahmed, F.; Arjovsky, M.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A. Improved training of Wasserstein GANs. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30.

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aila, T. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 789–798.

- Brock, A.; Donahue, J.; Simonyan, K. Large scale GAN training for high-fidelity natural image synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019.

- Miyato, T.; Kataoka, T.; Koyama, M.; Yoshida, Y. Spectral normalization for generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2018. arXiv:1802.05957.

- Cubuk, E.; Zoph, B.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. RandAugment: Practical automated data augmentation with a reduced search space. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020.

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Odena, A.; Lee, H. Consistency regularization for generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019.

- Aksac, A.; Demetrick, D.J.; Ozyer, T.; Alhajj, R. BreCaHAD: A dataset for breast cancer histopathological annotation and diagnosis. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 400. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karras, T.; Aila, T.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J. Progressive growing of GANs for improved quality, stability, and variation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018.

- Hirose, S.; Wada, N.; Katto, J.; Sun, H. ViT-GAN: Using vision transformer as discriminator with adaptive data augmentation. In 2021 3rd International Conference on Computer Communication and the Internet (ICCCI), 2021; pp. 185–189.

- Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, P.; Gao, J.; Chen, C. Feature quantization improves GAN training. arXiv 2020. arXiv:2004.02088.

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022.

- Dong, Y.; Cordonnier, J.-B.; Loukas, A. Attention is not all you need: Pure attention loses rank doubly exponentially with depth. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 139, 460–470.

- Liu, Y.; Matsoukas, C.; Strand, F.; Azizpour, H.; Smith, K. PatchDropout: Economizing vision transformers using patch dropout. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2023.

- Kang, G.; Dong, X.; Zheng, L.; Yang, Y. PatchShuffle regularization. arXiv 2017. arXiv:1707.07103.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008.

- Bertasius, G.; Wang, H.; Torresani, L. Is space-time attention all you need for video understanding? In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual Event, 18–24 July 2021; Volume 2, No. 3.

- Kumar, M.; Weissenborn, D.; Kalchbrenner, N. Colorization transformer. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021.

- Shaw, P.; Uszkoreit, J.; Vaswani, A. Self-Attention with relative position representations. In Proceedings of NAACL, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2018; pp. 464–468.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67.

- Hu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Z.; Lin, S. Local relation networks for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, South Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3464–3473.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer normalization. arXiv 2016. arXiv:1607.06450.

- Ulyanov, D.; Vedaldi, A.; Lempitsky, V. Instance normalization: The missing ingredient for fast stylization. arXiv 2016. arXiv:1607.08022.

- Chandar, S.; Sankar, C.; Vorontsov, E.; Kahou, S.E.; Bengio, Y. Towards non-saturating recurrent units for modelling long-term dependencies. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, No. 01.

- Arjovsky, M.; Chintala, S.; Bottou, L. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2017.

Figure 1.

Generated samples by StyleGAN2-ADA. From left to right, the StyleGAN2-ADA models are trained with 10k, 5k and 2k images from FFHQ dataset, respectively.

Figure 1.

Generated samples by StyleGAN2-ADA. From left to right, the StyleGAN2-ADA models are trained with 10k, 5k and 2k images from FFHQ dataset, respectively.

Figure 2.

Proposed system architecture.

Figure 2.

Proposed system architecture.

Figure 3.

We subject each image fed to the discriminator to a variety of augmentations, with each transformation applied according to a probability p.

Figure 3.

We subject each image fed to the discriminator to a variety of augmentations, with each transformation applied according to a probability p.

Figure 4.

ViT Based Discriminator Architecture.

Figure 4.

ViT Based Discriminator Architecture.

Figure 5.

We implement grid-based self-attention at multiple stages of the transformer.

Figure 5.

We implement grid-based self-attention at multiple stages of the transformer.

Figure 6.

ViT-D Based StyleGAN2-ADA FID Score Progression Over Training on AFHQ dataset.

Figure 6.

ViT-D Based StyleGAN2-ADA FID Score Progression Over Training on AFHQ dataset.

Figure 7.

Generated samples for FFHQ. (a) Generated samples with the proposed ViT-D-StyleGAN2-ADA (256 × 256), (b) Zoomed version of (a).

Figure 7.

Generated samples for FFHQ. (a) Generated samples with the proposed ViT-D-StyleGAN2-ADA (256 × 256), (b) Zoomed version of (a).

Figure 8.

(a) Comparison of ViT-D StyleGAN2-ADA performance on the FFHQ and CIFAR-10 datasets, with and without the incorporation of the ADA pipeline. (b) Convergence analysis of the model under varying values of probability p, utilizing geometric augmentations, illustrating the impact of different augmentation intensities on model training and performance.

Figure 8.

(a) Comparison of ViT-D StyleGAN2-ADA performance on the FFHQ and CIFAR-10 datasets, with and without the incorporation of the ADA pipeline. (b) Convergence analysis of the model under varying values of probability p, utilizing geometric augmentations, illustrating the impact of different augmentation intensities on model training and performance.

Figure 9.

Impact of parameter p on the performance of different augmentation categories, illustrating how variations in p affect the FID score across distinct augmentation techniques, including bit, geometric, color, filter, noise, and cutout operations.

Figure 9.

Impact of parameter p on the performance of different augmentation categories, illustrating how variations in p affect the FID score across distinct augmentation techniques, including bit, geometric, color, filter, noise, and cutout operations.

Figure 10.

Visualization of modified loss metrics during training on the FFHQ dataset, depicting the progression of the ViT-D discriminator’s performance across generated, real, and validation images over the course of training.

Figure 10.

Visualization of modified loss metrics during training on the FFHQ dataset, depicting the progression of the ViT-D discriminator’s performance across generated, real, and validation images over the course of training.

Figure 11.

Generated samples for FFHQ (256 × 256) and AFHQ-CAT/DOG (512 × 512) using only 5k training images. TransGAN suffers from severe artifacts and overfitting, and fails to complete AFHQ (512 × 512) due to out-of-memory errors. StyleGAN2-ADA enhances local texture fidelity but occasionally degrades global structure. By contrast, ViT-D-StyleGAN2-ADA delivers sharper details, stronger global coherence, and markedly reduced mode collapse across all domains.

Figure 11.

Generated samples for FFHQ (256 × 256) and AFHQ-CAT/DOG (512 × 512) using only 5k training images. TransGAN suffers from severe artifacts and overfitting, and fails to complete AFHQ (512 × 512) due to out-of-memory errors. StyleGAN2-ADA enhances local texture fidelity but occasionally degrades global structure. By contrast, ViT-D-StyleGAN2-ADA delivers sharper details, stronger global coherence, and markedly reduced mode collapse across all domains.

Table 1.

FID comparison of StyleGAN2-ADA and ViT-D variants on FFHQ and AFHQ datasets. ↓means lower is better.

Table 1.

FID comparison of StyleGAN2-ADA and ViT-D variants on FFHQ and AFHQ datasets. ↓means lower is better.

| Datasets |

StyleGAN2-ADA |

+ ViT-D (Ours) |

+ ViT-D + DiffAug (Ours) |

+ ViT-D + bCR (Ours) |

| FFHQ |

5k |

10.96 |

10.69 |

11.02 |

10.13 |

| 10k |

8.13 |

7.87 |

10.11 |

8.24 |

| AFHQ WILD |

5k |

3.05 |

4.12 |

4.98 |

3.30 |

| AFHQ DOG |

5k |

7.40 |

6.35 |

6.84 |

5.81 |

| AFHQ CAT |

5k |

3.55 |

3.29 |

4.78 |

3.43 |

Table 2.

Cifar-10 FID and IS comparison across GAN methods, demonstrating that our + ViT-D achieves the best overall performance. ↓ means lower is better and ↑means higher is better.

Table 2.

Cifar-10 FID and IS comparison across GAN methods, demonstrating that our + ViT-D achieves the best overall performance. ↓ means lower is better and ↑means higher is better.

| Methods |

CIFAR-10 |

| FID↓ |

IS↑ |

| ViTGAN [7] |

5.03 |

9.43 |

| TransGAN [8] |

8.96 |

8.34 |

| ProGAN [18] |

15.88 |

8.62 |

| BigGAN [23] |

14.32 |

9.31 |

| FQ-GAN [25] |

5.72 |

8.53 |

| StyleGAN2-ADA [3] |

4.76 |

9.98 |

| +ViT-D (Ours) |

3.57 |

10.68 |

| +ViT-D + DiffAug (Ours) |

4.11 |

9.93 |

| +ViT-D + bCR (Ours) |

3.01 |

10.97 |

Table 3.

Ablation experimental result with FID↓ metrics of different methods on various datasets.

Table 3.

Ablation experimental result with FID↓ metrics of different methods on various datasets.

| Method |

FFHQ |

AFHQ WILD |

AFHQ DOG |

AFHQ CAT |

Average |

| Baseline |

8.13 |

3.41 |

7.40 |

3.55 |

5.62 |

| +ViT-D |

7.87 |

4.12 |

6.35 |

3.29 |

5.41 |

| +ViT-D + DiffAug |

10.11 |

4.98 |

6.84 |

4.78 |

6.68 |

| +ViT-D + bCR |

7.92 |

3.23 |

5.81 |

3.12 |

5.10 |

Table 4.

Computational effort expenditure and electricity consumption data for this research.

Table 4.

Computational effort expenditure and electricity consumption data for this research.

| Dataset |

Number of Runs |

Memory Usages (GB) |

Time per Run (days) |

GPU-years (Dule RTX 3090) |

Electricity (MWh) |

AFHQ

CIFAR-10

FFHQ |

24

16

100 |

8.2 ±0.5

2.7 ±0.5

4.5 ±0.5 |

12.5

2.5

4.9 |

0.41

0.05

0.67 |

8.96 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).