Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

1.1.1. Single-Frame Methods

1.1.2. Multi-Frame Methods

1.2. Motivation

2. Methods

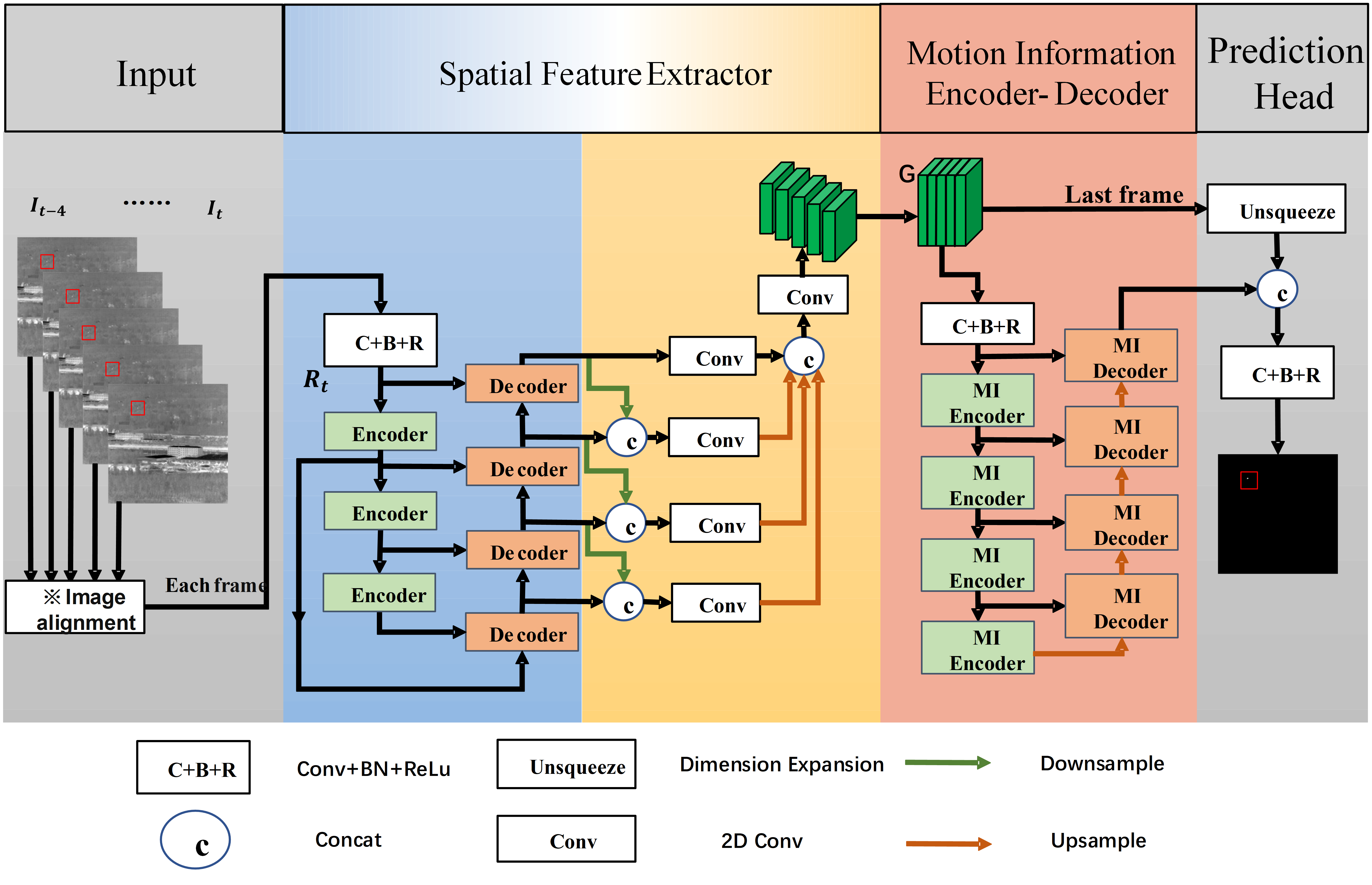

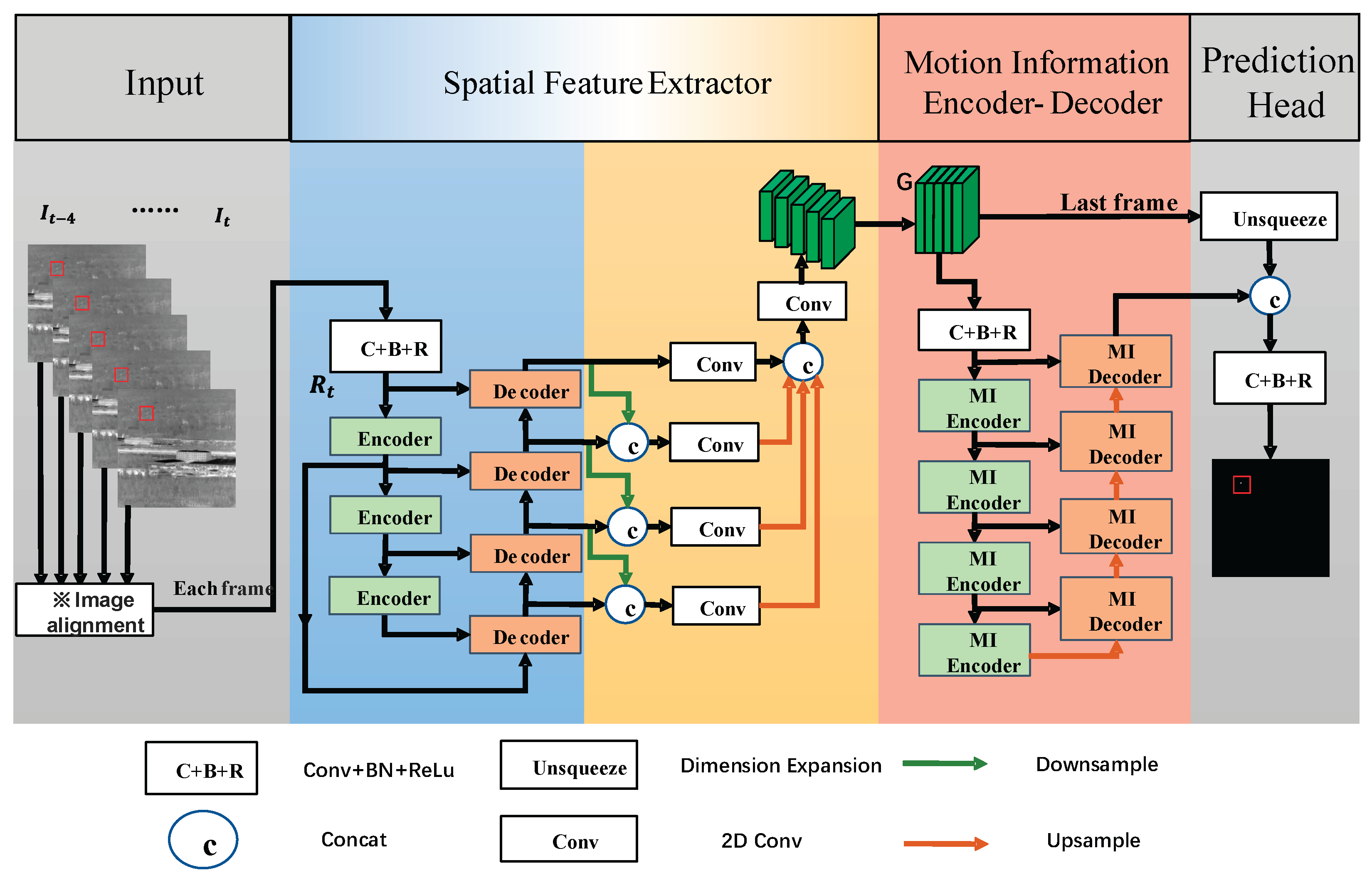

2.1. Overall Architecture

2.2. Spatial Feature Extractor

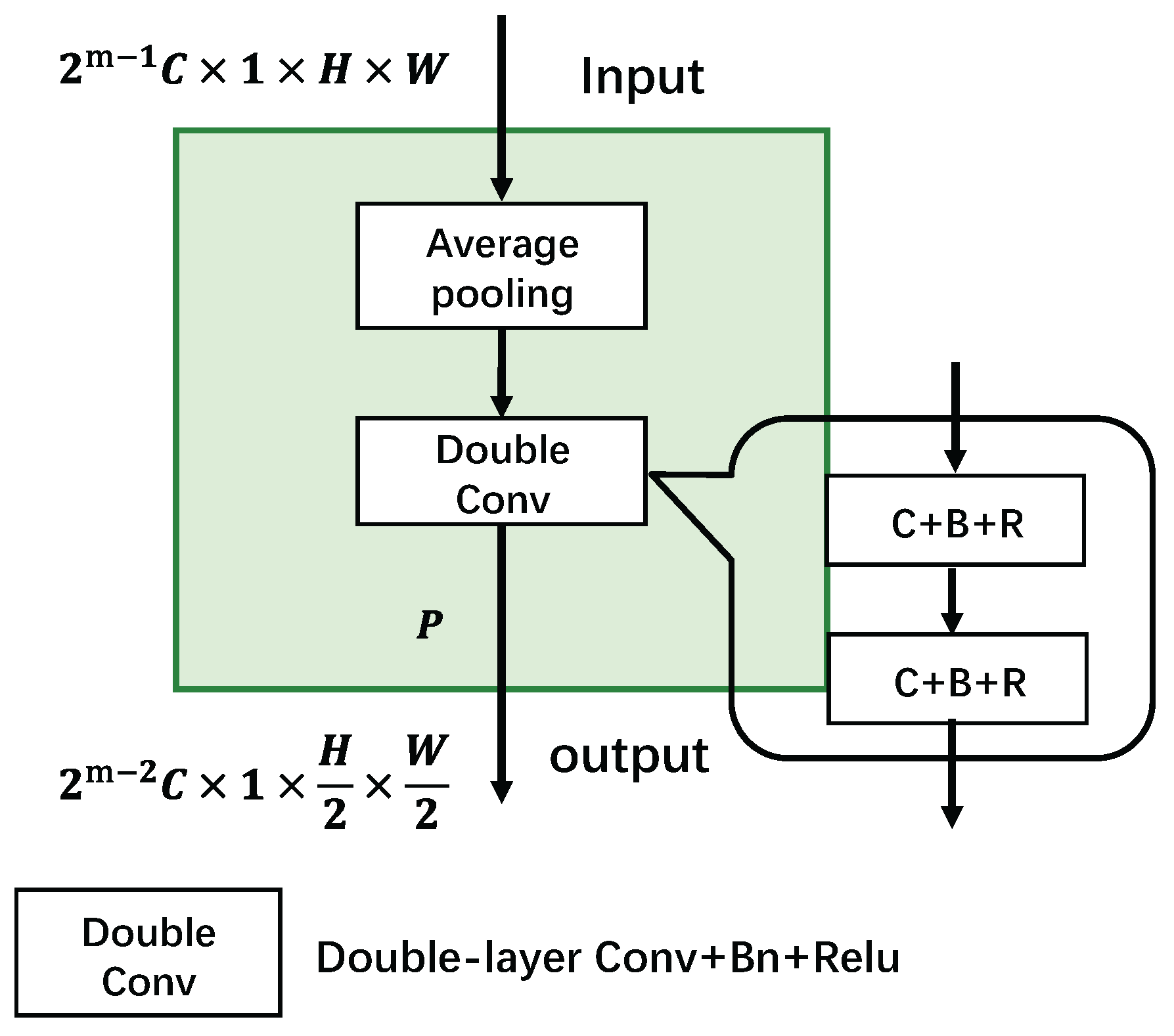

2.2.1. Encoder

2.2.2. Decoder

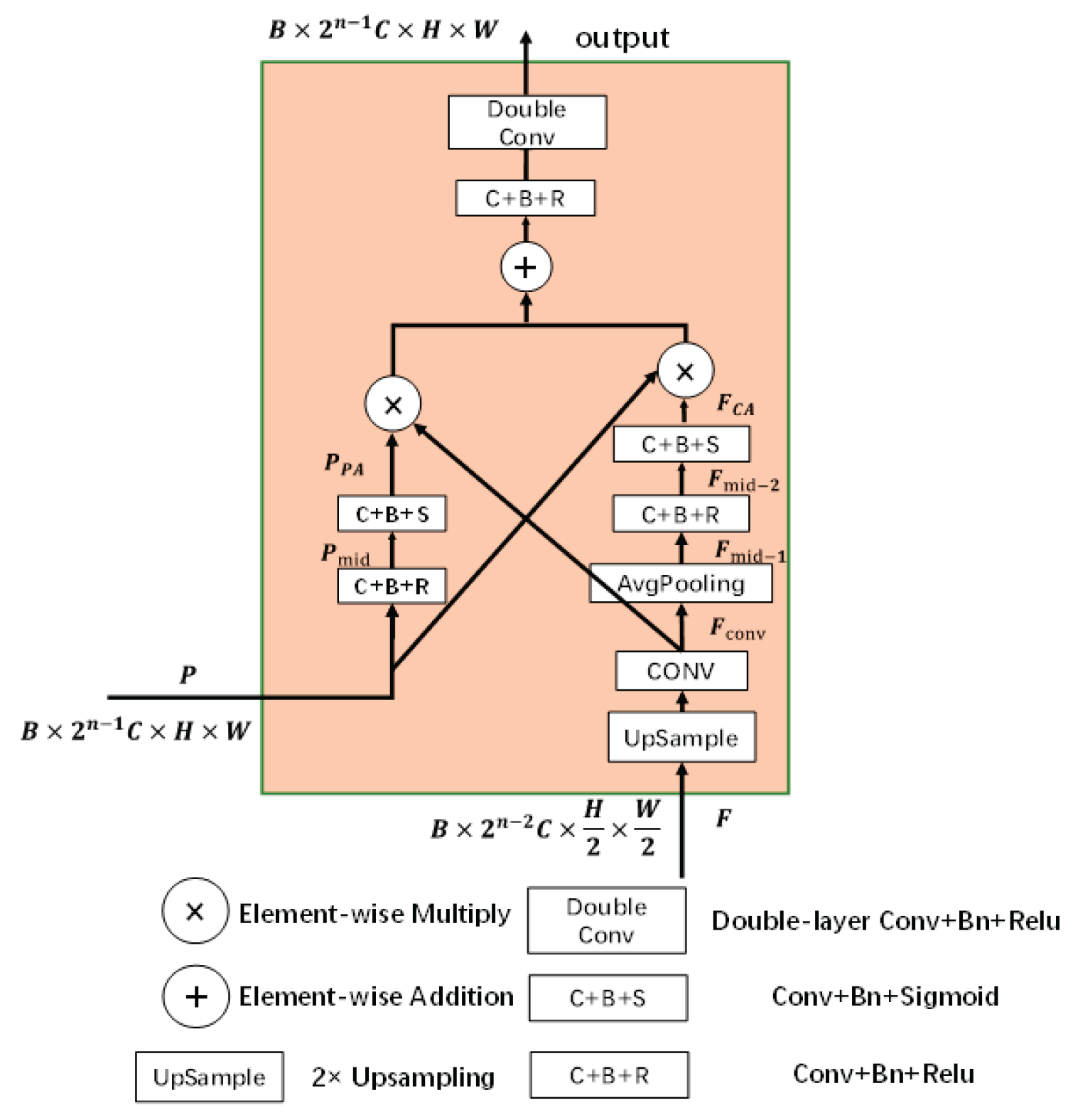

2.3. Motion Information Encoder

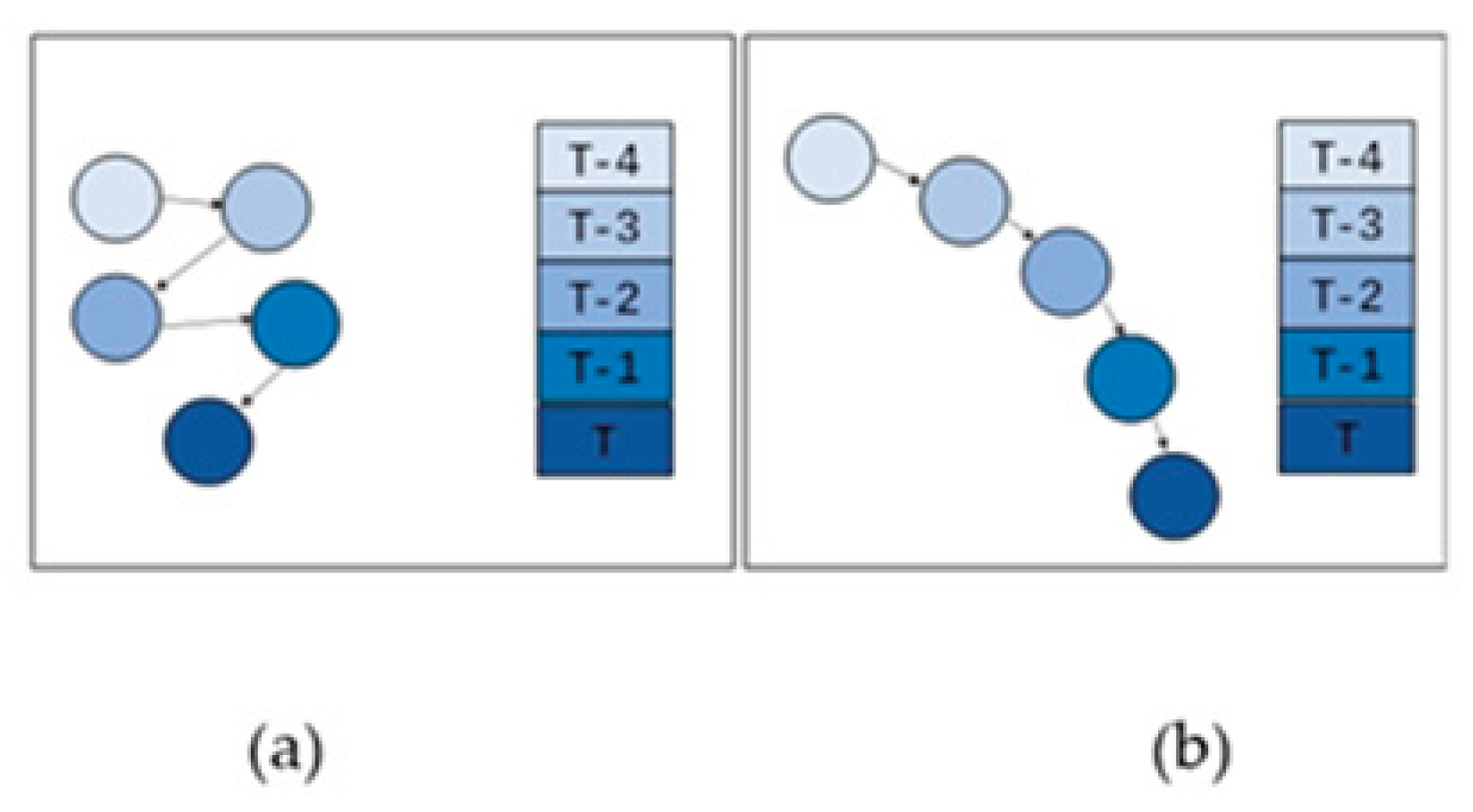

2.3.1. Inter-Frame Motion Encoding Module

| Algorithm 1: Inter-Frame Motion Encoding |

|

Input: Feature map F Output: Mapping value vector V |

| 1.(F_pool,index)=3DMaxpooling(F) 2: index_x(i)=index(i)%W // index_x [0,W) 3. index_y(i)=index(i)//W // index_y [0,H) 4. for i in range(T-1): if index_x(i)< index_x(t): = -1 if index_x(i)= index_x(t): = 0 if index_x(i)> index_x(t): = 1 // Horizontal direction encoding 5.for i in range(T-1): if index_y(i)< index_y (t): = -1 if index_y (i)= index_y (t): = 0 if index_y (i)> index_y (t): = 1 // Vertical direction encoding 6. for i in range(T-1): // V+= v(i) 7.V=V/(t-1) 8: return V |

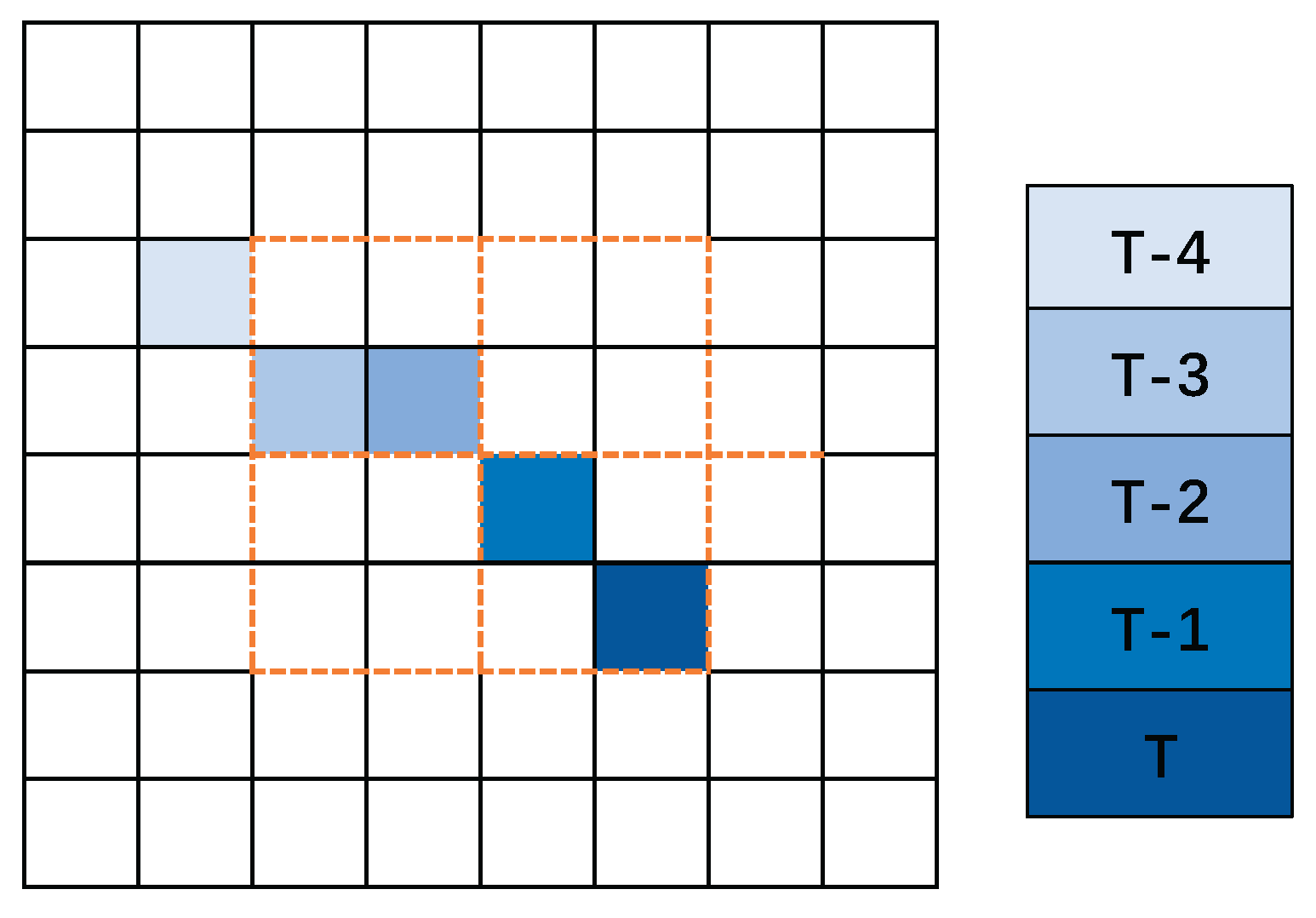

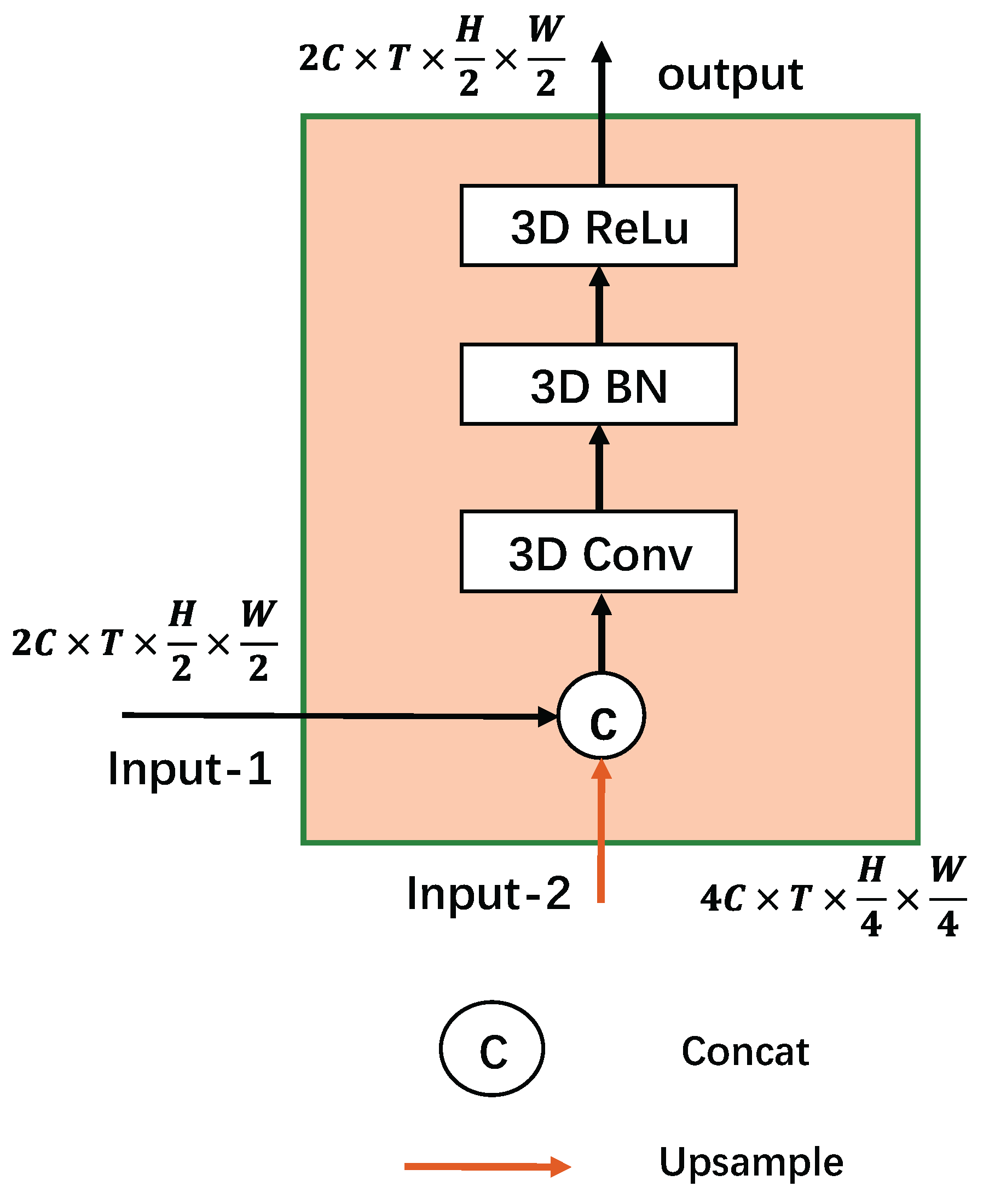

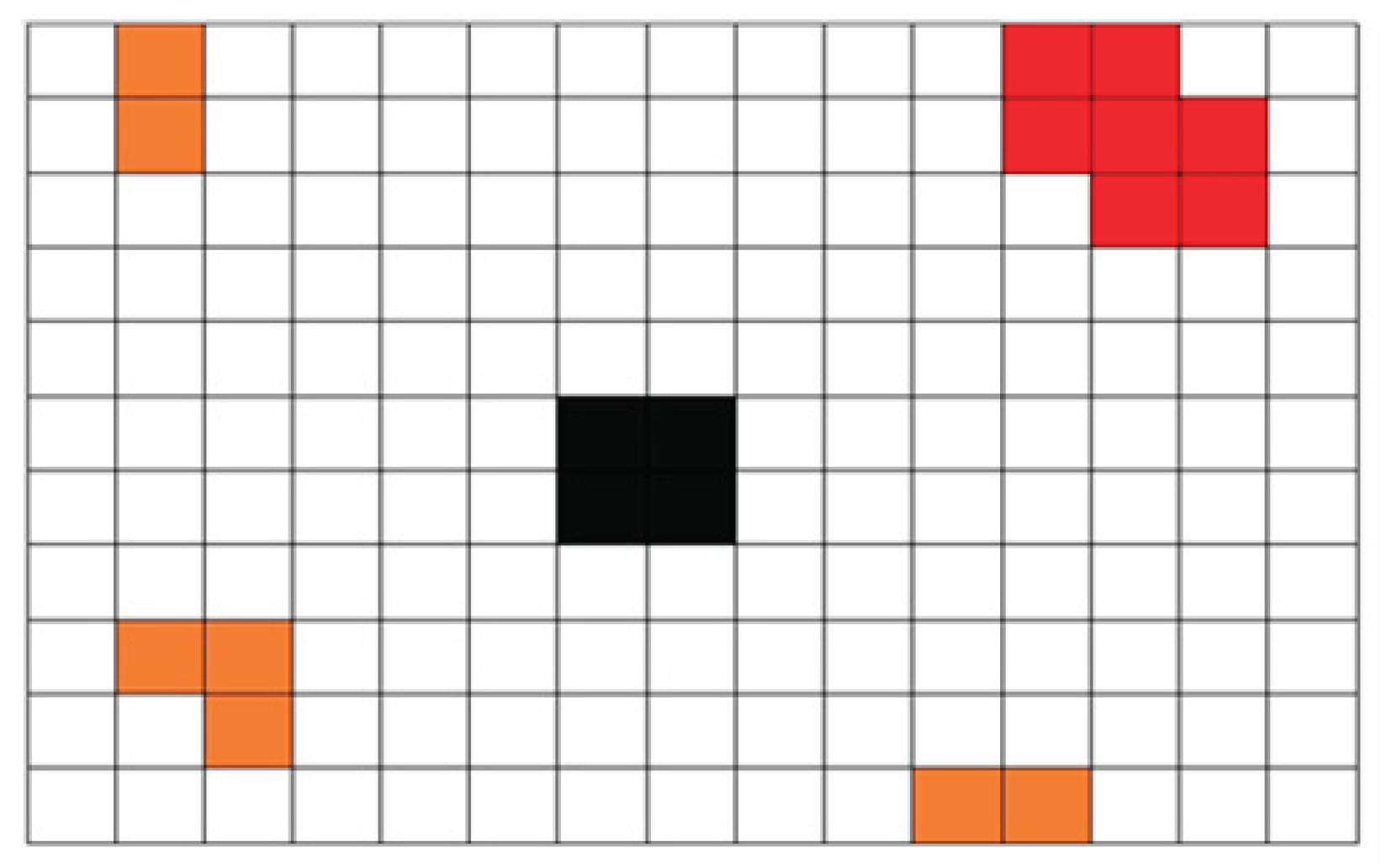

2.3.2. Intra-Frame Position Encoding

| Algorithm 2: Intra-Frame Position Encoding Module |

|

Input: Feature map F Output: Mapping value vector D |

| 1: (F_pool,index)=3DMaxpooling(F) 2: index_x(i)=index(i)%2 //The result is 0 or 1, which means on the left or right 3. index_y(i)=(index(i)//W)%2 // The result is 0 or 1, which means in the upper or lower area 4. for i in range(T): D(i)=1.25+ // The codes of the four positions are 5: return D |

2.4. Motion Information Decoder

3. Experiments and Results

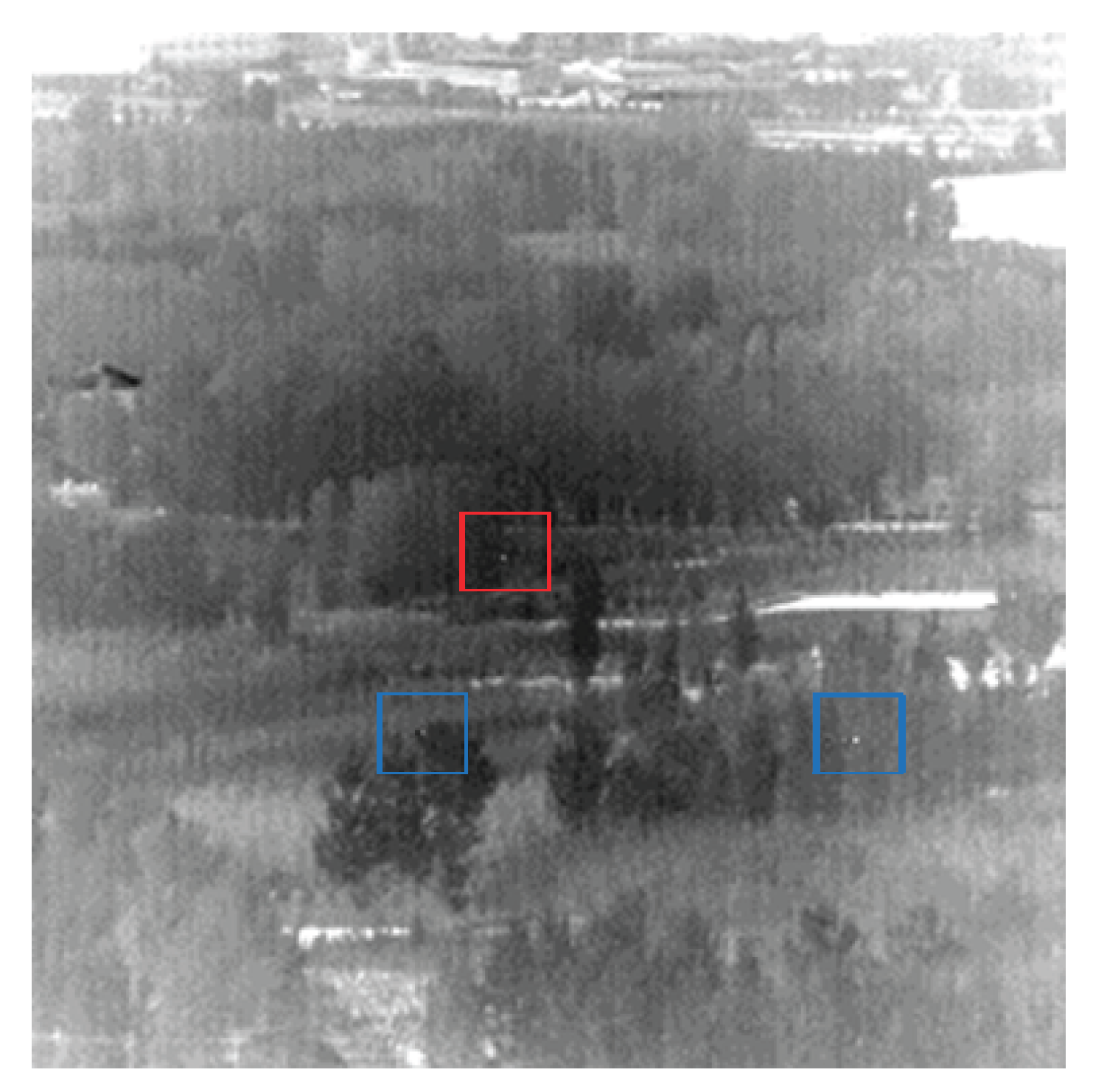

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Performance Evaluation Indices

3.3. Network Training

3.4. Ablation Study

3.4.1. Effectiveness of the MI Encoder

- Model A: An encoder that uses neither the inter-frame nor intra-frame encoding modules.

- Model B: An encoder that uses only the intra-frame position encoding module.

- Model C: An encoder that uses only the inter-frame motion encoding module.

- Model D: The complete encoder with both inter-frame and intra-frame motion encoding modules.

3.4.2. Effectiveness of the Spatial Feature Extractor

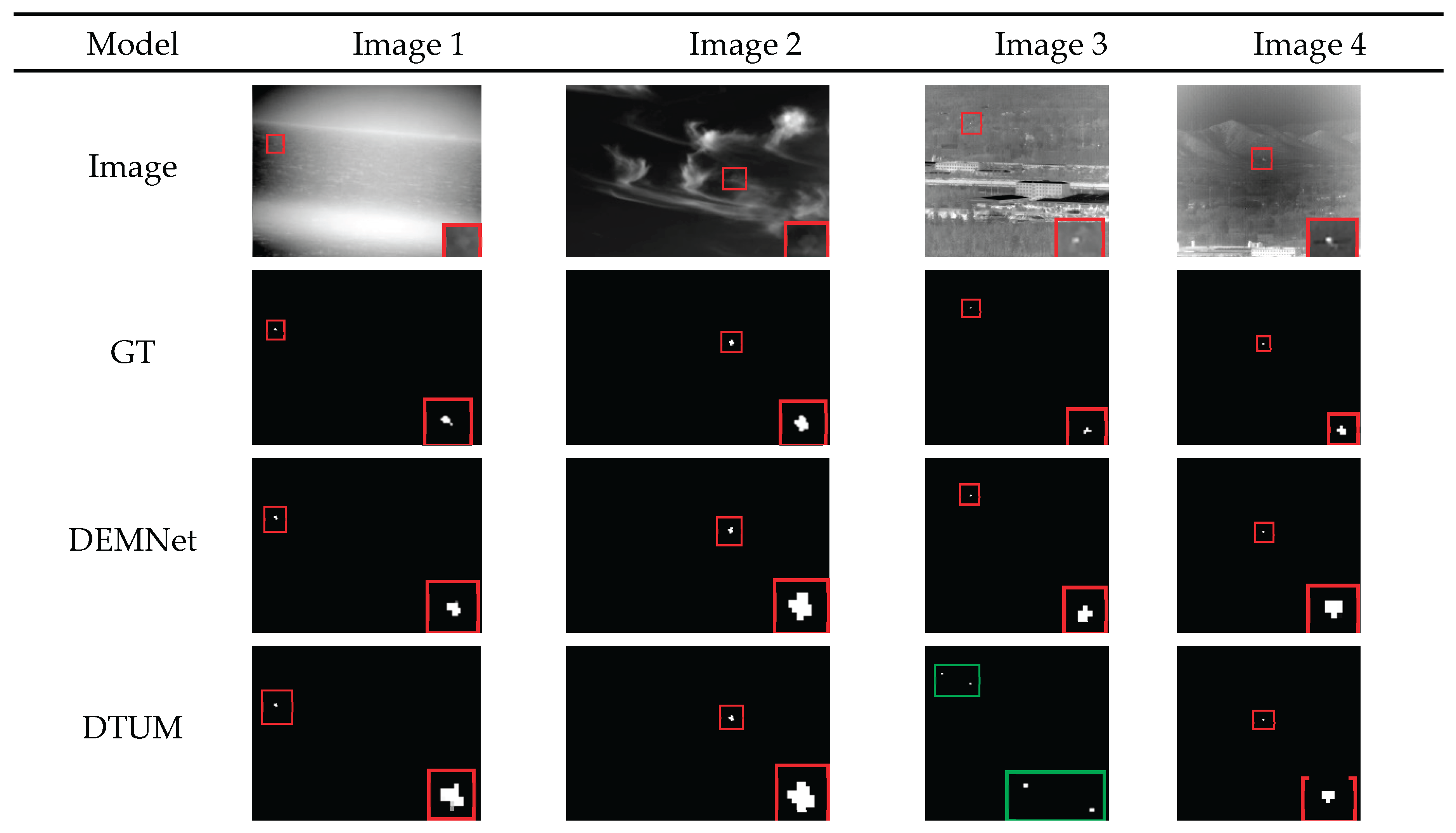

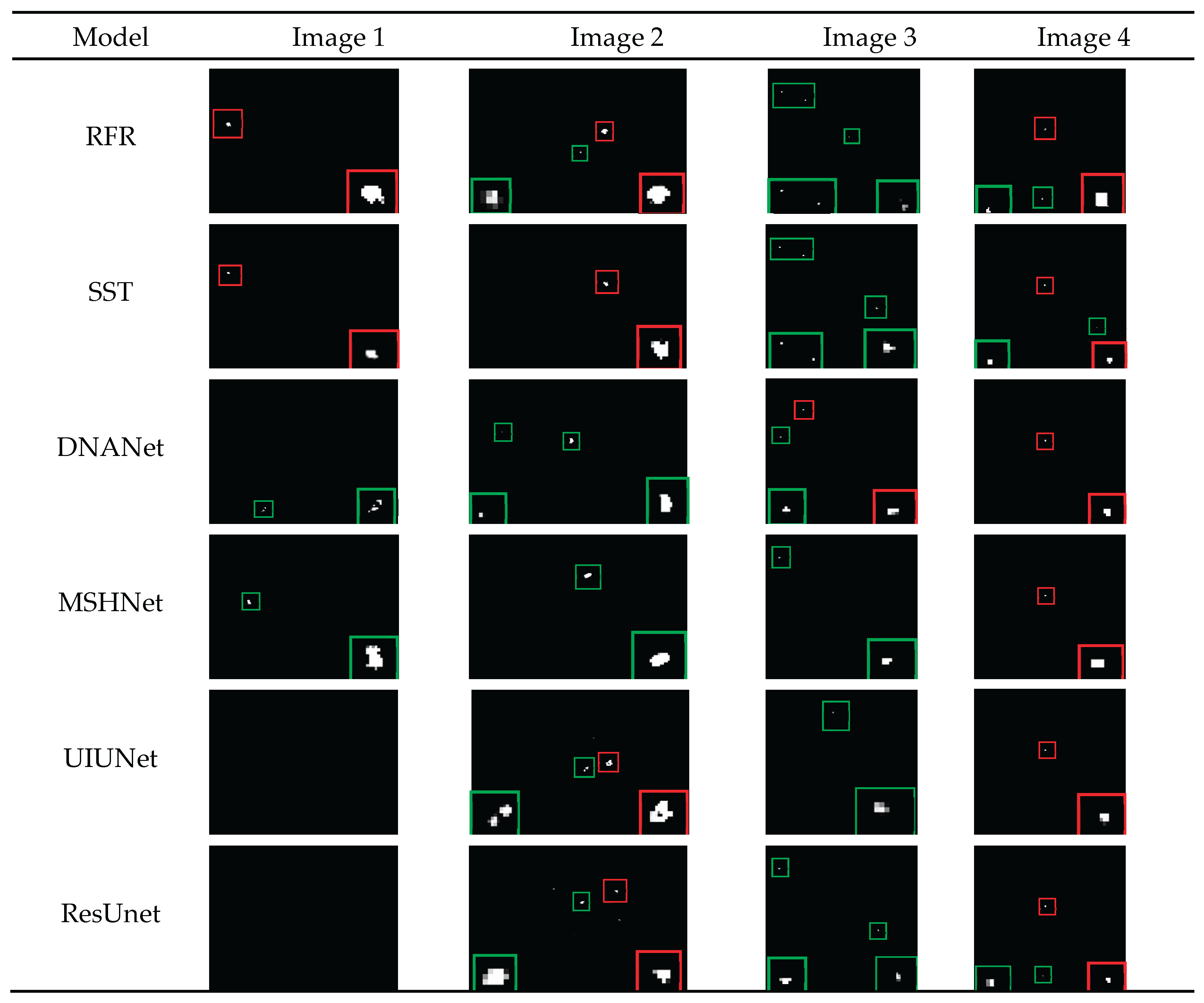

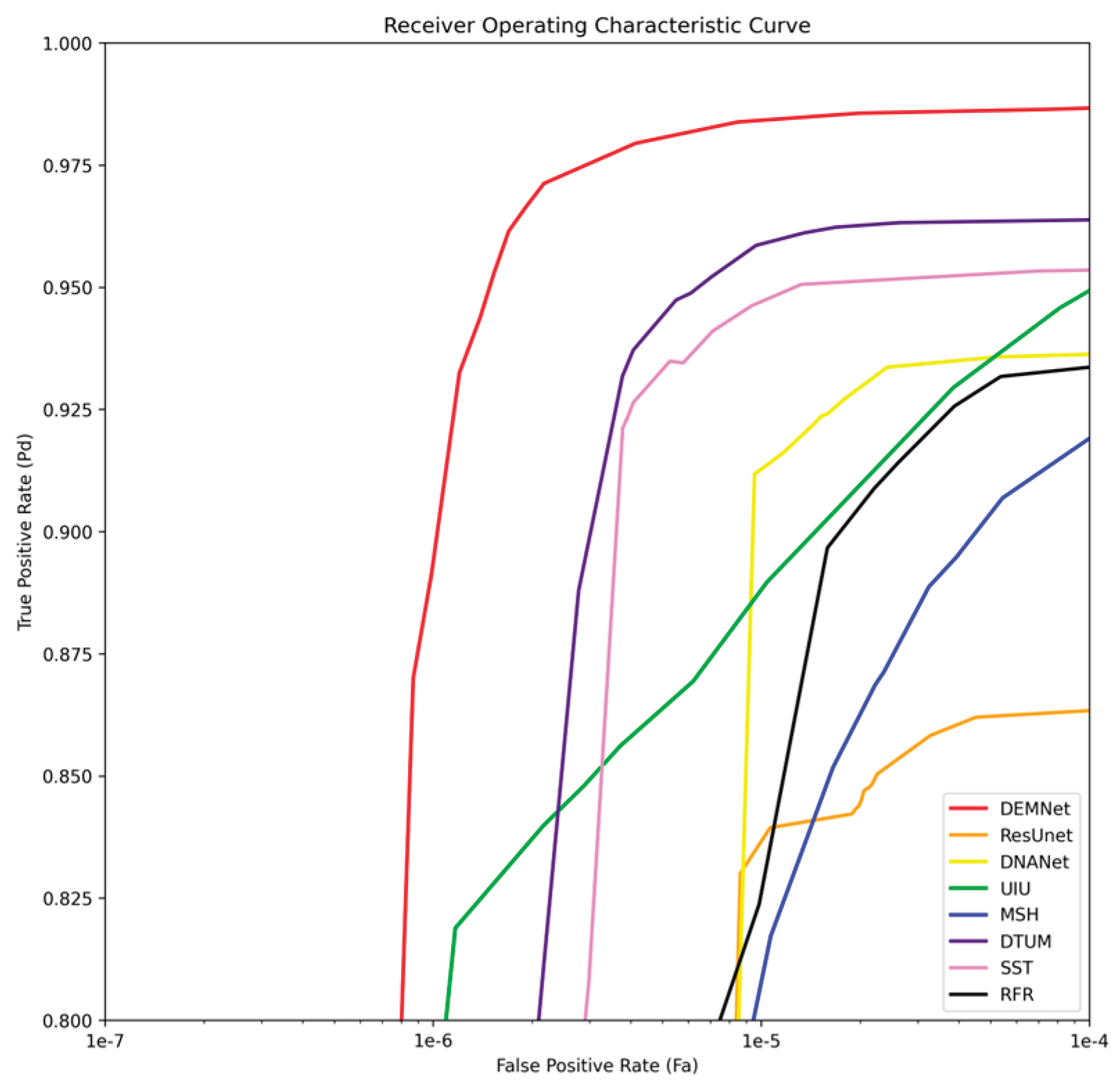

3.5. Comparative Experiments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deshpande, S.D.; Er, M.H.; Ronda, V.; Chan, P. Max-Mean and Max-Median Filters for Detection of Small-Targets [C]. Proceedings of SPIE’s International Symposium on Optical Science, Engineering, and Instrumentation, Denver, CO 1999, 74–83. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Xie, W.; Pei, J. Background Modeling in the Fourier Domain for Maritime Infrared Target Detection. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2020, 30, 2634–2649. [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Fan, H.; Lu, G.; Xu, J. An Improved Infrared Dim and Small Target Detection Algorithm Based on the Contrast Mechanism of Human Visual System. Infrared Physics & Technology 2012, 55, 403–408. [CrossRef]

- Shengxiang Qi; Jie Ma; Chao Tao; Changcai Yang; Jinwen Tian A Robust Directional Saliency-Based Method for Infrared Small-Target Detection Under Various Complex Backgrounds. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sensing Lett. 2013, 10, 495–499. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Meng, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Hauptmann, A.G. Infrared Patch-Image Model for Small Target Detection in a Single Image. IEEE Trans. on Image Process. 2013, 22, 4996–5009. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.P.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Xia, T.; Tang, Y.Y. A Local Contrast Method for Small Infrared Target Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2014, 52, 574–581. [CrossRef]

- Jinhui Han; Yong Ma; Bo Zhou; Fan Fan; Kun Liang; Yu Fang A Robust Infrared Small Target Detection Algorithm Based on Human Visual System. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sensing Lett. 2014, 11, 2168–2172. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, D.; Chen, H. Infrared Small Target Detection Based on Local Intensity and Gradient Properties. Infrared Physics & Technology 2018, 89, 88–96. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Moallem, P.; Sabahi, M.F. A False-Alarm Aware Methodology to Develop Robust and Efficient Multi-Scale Infrared Small Target Detection Algorithm. Infrared Physics & Technology 2018, 89, 387–397. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Barnard, K. Asymmetric Contextual Modulation for Infrared Small Target Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2021; pp. 949–958.

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Barnard, K. Attentional Local Contrast Networks for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 59, 9813–9824. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Du, S.; Liu, C.; Cao, Z. Interior Attention-Aware Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hong, D.; Chanussot, J. UIU-Net: U-Net in U-Net for Infrared Small Object Detection. IEEE Trans. on Image Process. 2023, 32, 364–376. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xiao, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, M.; An, W.; Guo, Y. Dense Nested Attention Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. on Image Process. 2023, 32, 1745–1758. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Gao, C.; Chen, F.; Meng, D.; Zuo, W.; Gao, X. Infrared Small and Dim Target Detection With Transformer Under Complex Backgrounds. IEEE Trans. on Image Process. 2023, 32, 5921–5932. [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wan, M.; Xu, Y.; Kong, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Gu, G. WTAPNet: Wavelet Transform-Based Augmented Perception Network for Infrared Small-Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, R.; Zheng, B.; Wang, H.; Fu, Y. Infrared Small Target Detection with Scale and Location Sensitivity. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA, June 16 2024; pp. 17490–17499.

- Zhang, F.; Li, C.; Shi, L. Detecting and Tracking Dim Moving Point Target in IR Image Sequence. Infrared Physics & Technology 2005, 46, 323–328. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Sun, S.-G.; Kim, K.-T. Highly Efficient Supersonic Small Infrared Target Detection Using Temporal Contrast Filter. Electronics Letters 2014, 50, 81–83. [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zhu, H.; Tao, C.; Wei, Y. Infrared Moving Point Target Detection Based on Spatial–Temporal Local Contrast Filter. Infrared Physics & Technology 2016, 76, 168–173. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Guan, Y.; Deng, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Infrared Moving Point Target Detection Based on an Anisotropic Spatial-Temporal Fourth-Order Diffusion Filter. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2018, 68, 550–556. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, J.; An, W. Infrared Dim and Small Target Detection via Multiple Subspace Learning and Spatial-Temporal Patch-Tensor Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2021, 59, 3737–3752. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Yu, H.; Liu, A.; Luo, J.; Peng, Z. Infrared Small Target Detection Using Spatiotemporal 4-D Tensor Train and Ring Unfolding. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Sparse Regularization-Based Spatial–Temporal Twist Tensor Model for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Hui, B.; Song, Z.; Fan, H.; Zhong, P.; Hu, W.; Zhang, X.; Ling, J.; Su, H.; Jin, W.; Zhang, Y; Bai, Y. A Dataset for Infrared Detection and Tracking of Dim-Small Aircraft Targets under Ground / Air Background. China Scientific Data 2020, 5(3).

- Li, R.; An, W.; Xiao, C.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Guo, Y. Direction-Coded Temporal U-Shape Module for Multiframe Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2025, 36, 555–568. [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Cui, W.; Yan, P. Infrared Image Small-Target Detection Based on Improved FCOS and Spatio-Temporal Features. Electronics 2022, 11, 933. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, C.; Gribben, D. Practical Approaches to Target Detection in Long Range and Low Quality Infrared Videos. Signal & Image Processing An International Journal 2021, 12, 01–16.

- Kwan, C.; Gribben, D.; Budavari, B. Target Detection and Classification Performance Enhancement Using Super-Resolution Infrared Videos. Signal & Image Processing : An International Journal 2021, 12, 33–45. [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Sheng, W.; Liu, L.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, S. Local Motion and Contrast Priors Driven Deep Network for Infrared Small Target Super-Resolution. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2022, 15, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Hou, R.; Duan, X.; Yue, C.; Wang, X.; Cao, X. STDMANet: Spatio-Temporal Differential Multiscale Attention Network for Small Moving Infrared Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ji, L.; Zhu, J.; Ye, M.; Yao, X. SSTNet: Sliced Spatio-Temporal Network With Cross-Slice ConvLSTM for Moving Infrared Dim-Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Ji, L.; Chen, S.; Zhu, S.; Ye, M. Triple-Domain Feature Learning with Frequency-Aware Memory Enhancement for Moving Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Liu, L.; Lin, Z.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Cao, X.; Li, B.; Zhou, S.; An, W. Infrared Small Target Detection in Satellite Videos: A New Dataset and A Novel Recurrent Feature Refinement Framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2025, 1–1.

- Liu, X.; Zhu, W.; Yan, P.; Tan, Y. IR-MPE: A Long-Term Optical Flow-Based Motion Pattern Extractor for Infrared Small Dim Targets. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ji, L.; Chen, S.; Duan, W.; Zhu, S. Moving Infrared Dim and Small Target Detection by Mixed Spatio-Temporal Encoding. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2025, 144, 110100.

- Zhu, S.; Ji, L.; Chen, S.; Duan, W. Spatial–Temporal-Channel Collaborative Feature Learning with Transformers for Infrared Small Target Detection. Image and Vision Computing 2025, 154, 105435. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Xi, Y.; Tan, F.; Hou, Q. STIDNet: Spatiotemporally Integrated Detection Network for Infrared Dim and Small Targets. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 250. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Ji, L.; Zhu, J.; Chen, S.; Duan, W. TMP: Temporal Motion Perception with Spatial Auxiliary Enhancement for Moving Infrared Dim-Small Target Detection. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 255, 124731. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Qin, H.; Kou, R.; Yan, X.; Li, Z.; Peng, C.; Wu, D.; Zhou, H. Beyond Full Labels: Energy-Double-Guided Single-Point Prompt for Infrared Small Target Label Generation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sensing 2025, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. International Conference on Learning Representations 2014.

- Xu, G.; Cao, H.; Dong, Y.; Yue, C.; Zou, Y. Stochastic Gradient Descent with Step Cosine Warm Restarts for Pathological Lymph Node Image Classification via PET/CT Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 5th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing (ICSIP); 2020; pp. 490–493.

- Diakogiannis, F.I.; Waldner, F.; Caccetta, P.; Wu, C. ResUNet-a: A Deep Learning Framework for Semantic Segmentation of Remotely Sensed Data. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 162, 94–114. [CrossRef]

| Model | Module | DAUB | NUDT(All) | ||||||

| 3D Max-pooling |

Intra-frame encoding |

Inter-frame encoding |

Pd/% | Fa/10-6 | FaT/% | Pd/% | Fa/10-6 | FaT/% | |

| A | √ | 94.71 | 8.13 | 19.20 | 96.01 | 27.17 | 13.62 | ||

| B | √ | √ | 96.37 | 4.99 | 10.22 | 97.39 | 18.16 | 9.01 | |

| C | √ | √ | 95.56 | 3.08 | 5.21 | 96.82 | 10.34 | 7.35 | |

| D | √ | √ | √ | 98.28 | 1.88 | 5.01 | 98.21 | 8.56 | 6.19 |

| Model | Module | DAUB | NUDT(All) | ||||

| Pd/% | Fa/10-6 | FaT/% | Pd/% | Fa/10-6 | FaT/% | ||

| A | ResBlock & Upsample | 94.62 | 9.28 | 6.48 | 94.39 | 9.28 | 6.48 |

| B | w/o Attention Fusion | 97.06 | 8.20 | 6.07 | 96.04 | 8.19 | 6.02 |

| C | Complete module | 98.28 | 1.88 | 5.01 | 98.21 | 8.56 | 6.19 |

| DAUB | Resource and Speed | ||||||

| Pd/% | Fa/10-6 | FaT/% | Params/M | Flops/G | FPS | ||

| Single Frame |

ResUNet [43] | 85.70 | 25.48 | 20.45 | 0.914 | 2.589 | 79.9 |

| DNANet [14] | 92.15 | 14.35 | 21.63 | 1.134 | 7.795 | 37.6 | |

| UIUNet [13] | 86.54 | 7.85 | 16.18 | 50.541 | 54.501 | 32.7 | |

| MSHNet [17] | 87.29 | 24.77 | 32.74 | 4.065 | 6.065 | 45.1 | |

| Multi Frame |

DTUM [26] | 95.86 | 6.01 | 10.31 | 0.298 | 15.351 | 24.4 |

| SST [32] | 89.76 | \ | 5.05 | 11.418 | 43.242 | 21.8 | |

| RFR [34] | 92.16 | 8.79 | 19.43 | 1.206 | 14.719 | 40.2 | |

| DEMNet | 98.28 | 1.88 | 5.01 | 4.458 | 64.131* | 14.8 | |

| NUDT(SNR≤3) | NUDT(3<SNR<10) | NUDT(All) | ||||||||

| Pd/% | Fa/10-6 | FaT/% | Pd/% | Fa/10-6 | FaT/% | Pd/% | Fa/10-6 | FaT/% | ||

| Single Frame |

ResUNet [43] | 17.58 | 506.95 | 246.13 | 81.33 | 472.12 | 116.67 | 61.48 | 485.97 | 155.87 |

| DNANet [14] | 19.28 | 441.42 | 227.60 | 89.83 | 123.56 | 35.83 | 68.25 | 249.91 | 94.51 | |

| UIUNet [13] | 28.36 | 195.82 | 106.62 | 82.67 | 62.81 | 28.47 | 66.05 | 115.69 | 52.17 | |

| MSHNet [17] | 4.537 | 441.44 | 175.61 | 86.00 | 66.63 | 29.75 | 61.08 | 215.65 | 74.38 | |

| Multi Frame |

DTUM [26] | 90.74 | 9.22 | 14.18 | 99.08 | 9.23 | 3.33 | 96.53 | 9.23 | 6.65 |

| SST [32] | 51.04 | \ | 32.9 | 80.75 | \ | 26.33 | 71.66 | \ | 28.34 | |

| RFR [34] | 39.41 | 60.907 | 39.779 | 90.42 | 106.28 | 41.50 | 74.527 | 88.240 | 40.96 | |

| DEMNet | 96.41 | 6.77 | 11.72 | 99.00 | 9.74 | 3.75 | 98.21 | 8.56 | 6.19 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).