Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

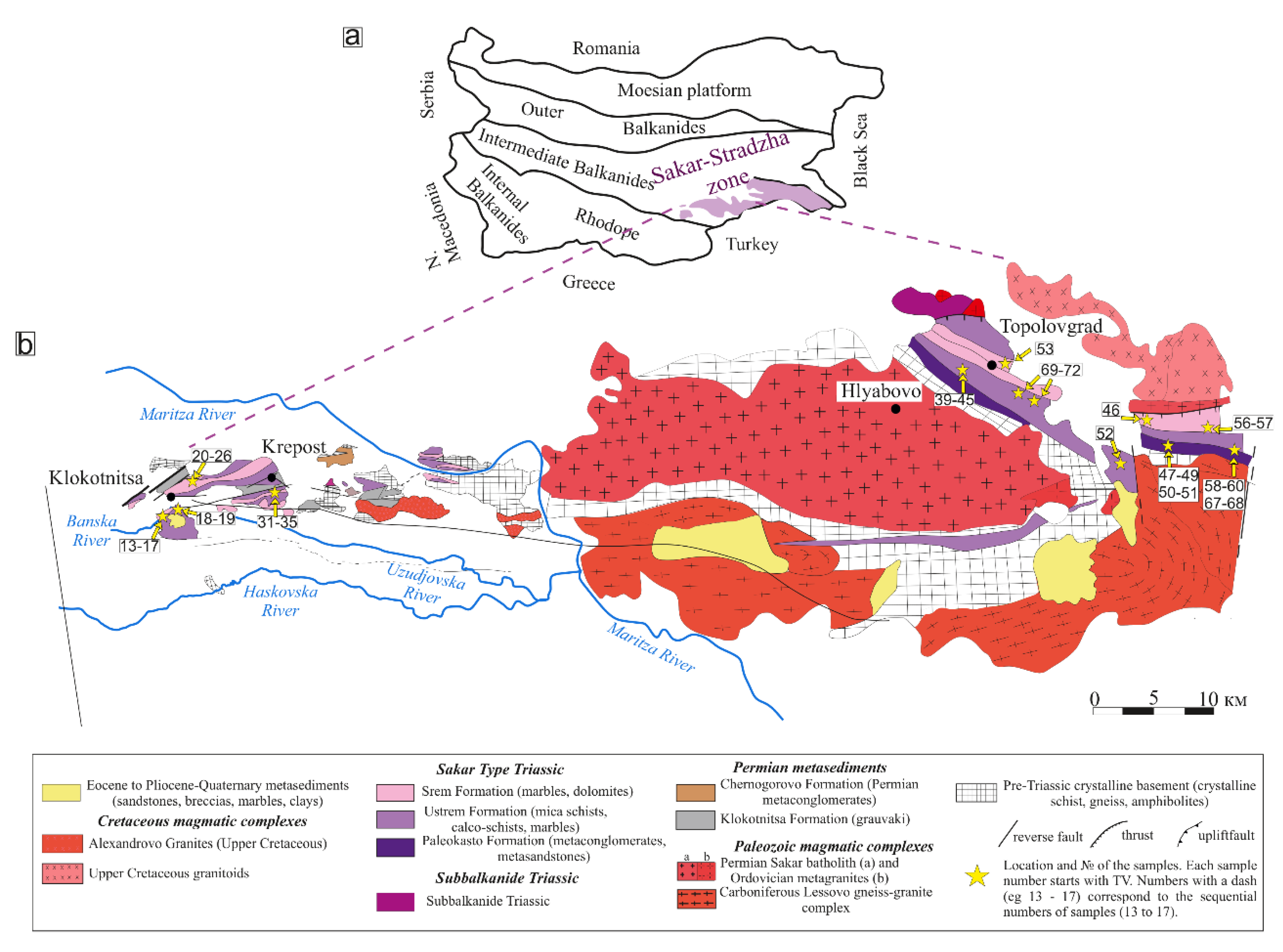

2. Geological Setting

3. Analytical Procedure

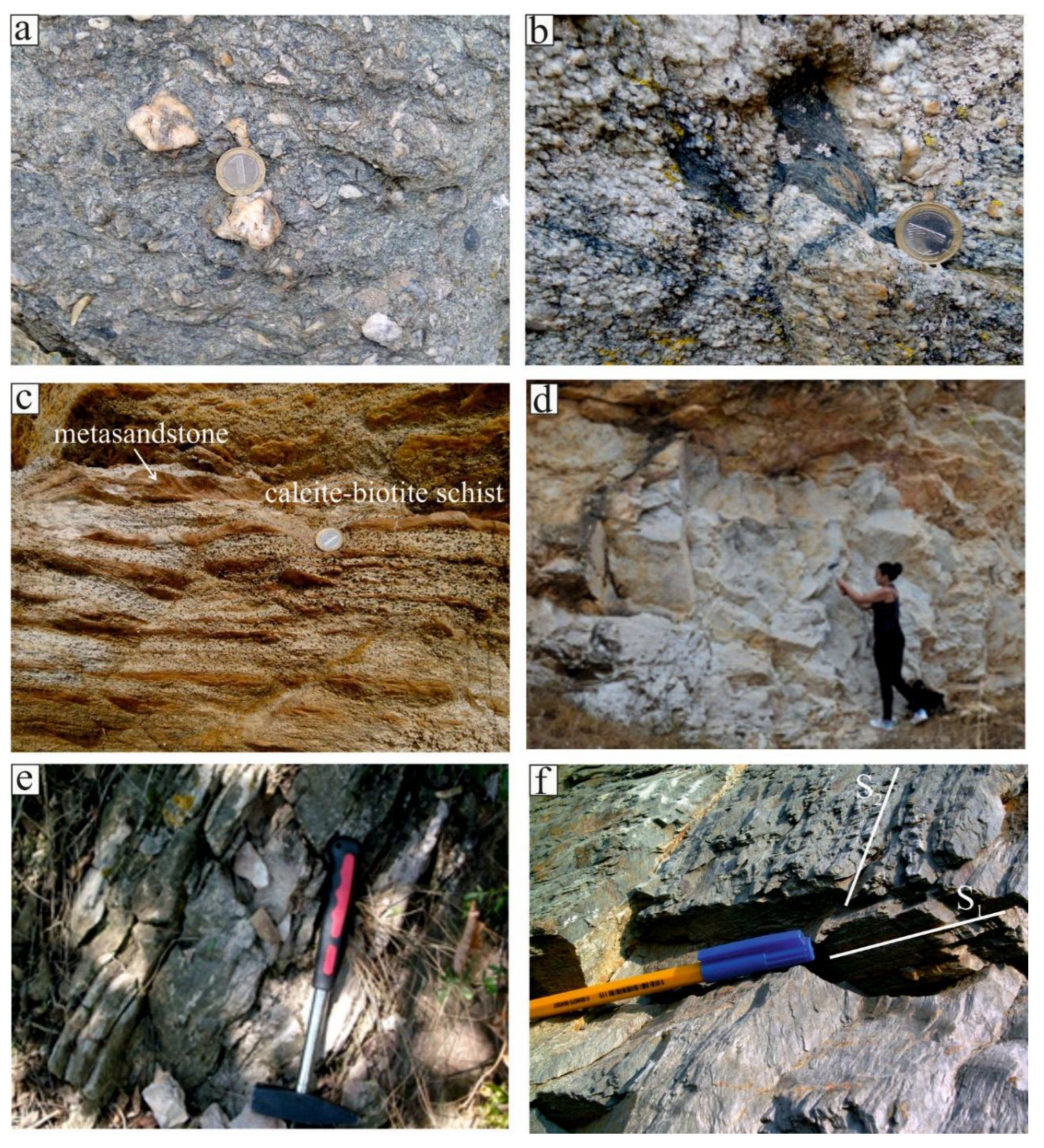

4. Field Observation and Sampling

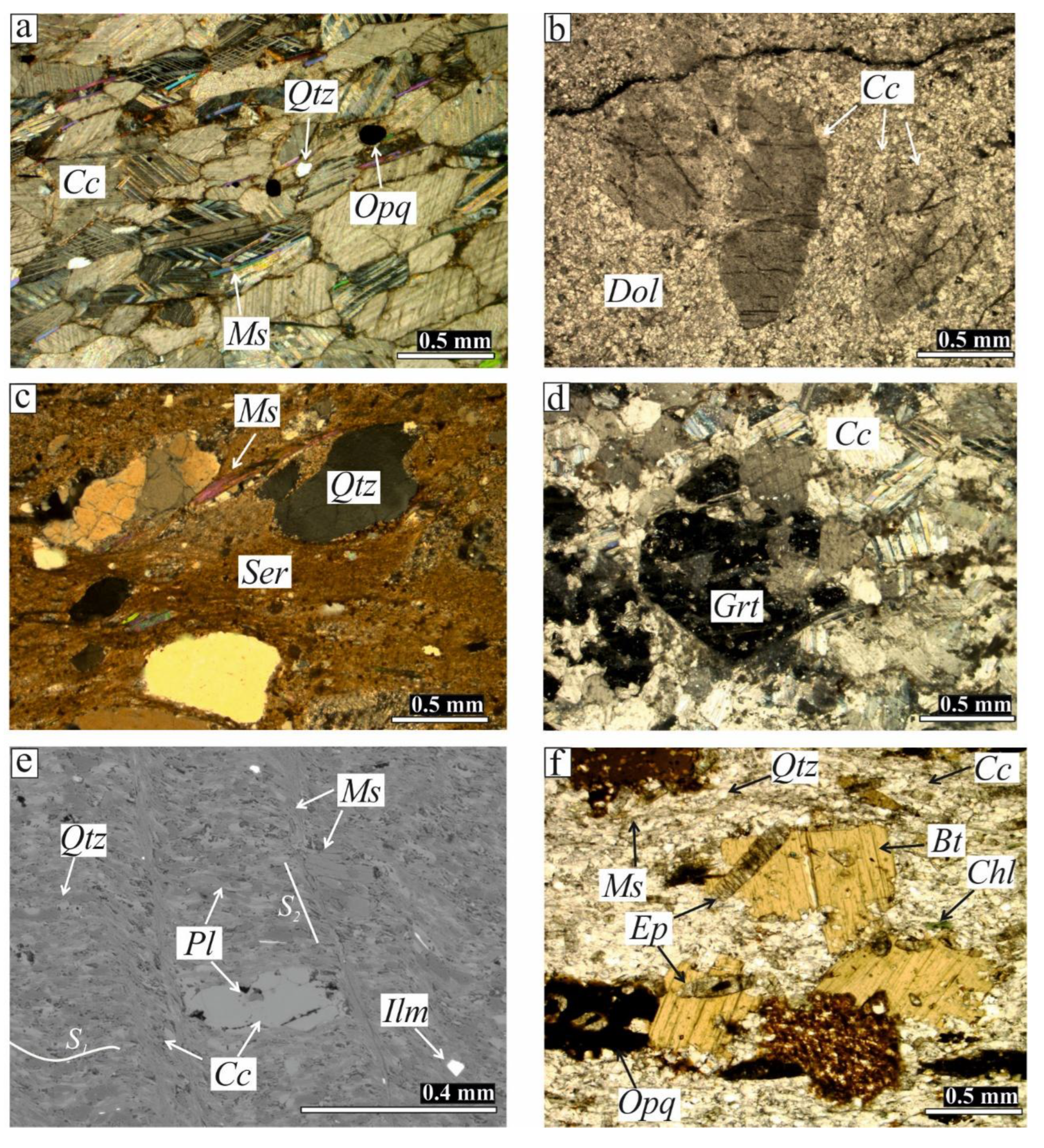

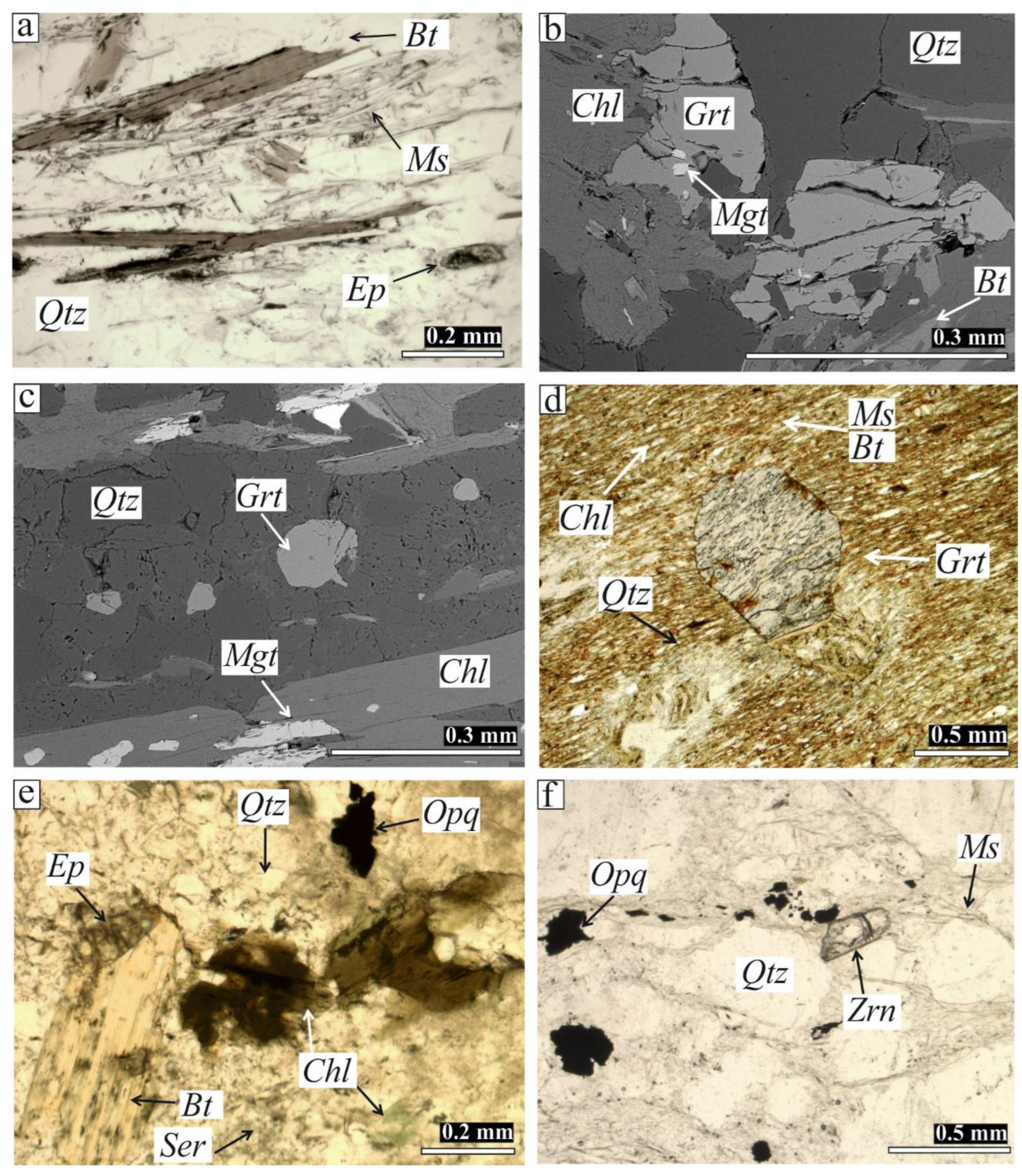

5. Petrographic Observation

5.1. Pure Marbles

5.2. Impure Marbles

5.3. Carbonate-Silicate Rocks

5.4. Silicate and Carbonate-Bearing Silicate Rocks

6. Geochemistry

6.1. Minerals Controlling Whole-Rock Geochemistry

6.2. Minerals Controlling the Whole-Rock Trace Elements Composition

6.3. Protoliths: Provenance, Weathering and Hydraulic Sorting

7. U-Pb Detrital Zircon Geochronology

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

References

- McLennan, S.M.; Hemming, S.; McDaniel, D.K.; Hanson, G.N. Geochemical approaches to sedimentation, provenance, and tectonics. In: Johnnson, M.J., Basu, A., (eds) Processes controlling the composition of clastic sediments. Geol. Soc. Am. 1993, Special Paper 284, London, 21–40.

- Bhatia, M.R.; Crook, K.A.W. Trace element characteristics of graywackes and tectonic setting discrimination of sedimentary basins. Contrib. Miner. Pet. 1986, 92, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roser, B.; Korsch, R. Provenance signatures of sandstone-mudstone suites determined using discriminant function analysis of major-element data. Chem. Geol. 1988, 67, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenestra, A.; Franz, G. Regional Metamorphism. Enc. Geol. 2005, 407–413. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrels, G. Detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology: current methods and new opportunities Tect. Sed. Basins. 2012, 2, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerli, J.; Spandler, C.; Oliver, N.H.S. Element redistribution and mobility during upper crustal metamorphism of metasedimentary rocks: an example from the eastern Mount Lofty Ranges, South Australia. Contrib. Miner. Pet. 2016, 171, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argue, J.J. Element mobility during regional metamorphism in crustal and subduction zone environments with a focus on the rare earth elements (REE). Am. Mineral. 2017, 102, 1796–1821. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanov, A.S. A review of the geochemical changes occurring during metamorphic devolatilization of metasedimentary rocks. Chem. Geol. 2021, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, U.; Veizer, J. Chemical diagenesis of a multicomponent carbonatee system—l: Trace elements. J. Sediment. Petrol. 1980, 4, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Reeder, R.J. 1983. Crystal chemistry of the rhombohedral carbonates.—In Reeder R. J. (ed.): Carbonates, Rev. Mineral.Geochem. 1983, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Veizer, J. Diagenesis of Pre-Quaternary Carbonates as Indicated by Tracer Studies. J. Sediment. Res. 1977, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.E.; Wright, V.P. Carbonate Sedimentology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, United States, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Komiya, T.; Hirata, T.; Kitajima, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Shibuya, T.; Sawaki, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Shu, D.; Li, Y.; Han, J. Evolution of the composition of seawater through geologic time, and its influence on the evolution of life. Gondwana Res. 2008, 14, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.-Y.; Zheng, Y.-F. Marine carbonate records of terrigenous input into Paleotethyan seawater: Geochemical constraints from Carboniferous limestones. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 141, 508–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melezhik, V. Strontium and carbon isotope geochemistry applied to dating of carbonate sedimentation: an example from high-grade rocks of the Norwegian Caledonides. Precambrian Res. 2001, 108, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostevin, R.; Shields, G.A.; Tarbuck, G.M.; He, T.; Clarkson, M.O.; Wood, R.A. Effective use of cerium anomalies as a redox proxy in carbonate-dominated marine settings. Chem. Geol. 2016, 438, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostevin, R. Cerium Anomalies and Paleoredox (Elements in Geochemical Tracers in Earth System Science). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Murray, W.R. Chemical criteria to identify the depositional environment of chert: general principles and applications. Sed. Geol. 1994, 90, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.-J.; Li, Q.-H.; Yan, L.-L.; Zeng, L.; Lua, L.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Hui, J.; Jin, X.; Tang, X.-C. Geochemistry of limestones deposited in various plate tectonic settings. Earth Sci. Rev. 2017, 167, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, P.K. The geochemistry of carbonate diagenesis: The past, present and future. Sedimentology 2015, 62, 1233–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantle, M.S.; Barnes, B.D.; Lau, K.V. The Role of Diagenesis in Shaping the Geochemistry of the Marine Carbonate Record. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 48, 549–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatalov, G. Geology of the Strandza zone in Bulgaria. Prof. Marin Drinov Publishing House of BAS, Sofia. 1990, 263 p. (in Bulgarian with an English summary).

- Kozouharov, D.; Savov, S. Lithostratigraphy of the metamorphic Triassic of the Lissovo Graben, South Sakar, Svilengrad district. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 1996, 49, 7–8, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zagorchev, I.; Budurov, K. : Triassic geology.—In: Zagorchev, I., Ch. Dabovski, T. Nikolov (Eds.) Geology of Bulgaria. Volume II. Part 5. Mesozoic Geology. Sofia, Prof. Marin Drinov Academic Publishing House, 2009, 766 p. (in Bulgarian with an English summary).

- Tzankova, N.; Pristavova, P. Metamorphic evolution of garnet-bearing schists from Sakar Mountain, Southeastern Bulgaria C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2007, 60, 3, 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdjikov, Ia.; Vangelov, D. 2025. Structure of the Southesternmost parts of the Strandzha zone, Sofia University Publishing House, 2025, 3-7 (in Bulgarian with English abstract).

- Ivanov, Zh. , 2017, Tectonics of Bulgaria. Sofia, Sofia University Publishing House, 199–224 p. (in Bulgarian with English abstract).

- Bonev, N.; Filipov, P.; Raicheva, R.; Moritz, R. Timing and tectonic significance of Paleozoic magmatism in the Sakar unit of the Sakar-Strandzha Zone, SE Bulgaria. Int. Geol. Rev. 2019, 61, 1957–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdjikov, I. 2005. Alpine metamorphism and granitoid magmatism in the Strandja Zone: New data from the Sakar Unit, SE Bulgaria Turk. J.Earth Sci. 2005, 14, 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sarov, S. Lithotectonic subdivision of the metamorphic rocks in the area of Rila and Rhodope Mountains—results from geological mapping at scale 1:50 000. 2012, In: International Conference “Geological Schools of Bulgaria. The School of Prof. Z. Ivanov”, 43–47.

- Naydenov, K.; Peytcheva, I.; von Quadt, A.; Sarov, S.; Kolcheva, K.; Dimov, D. The Maritsa strike-slip shear zone between Kostenets and Krichim towns, South Bulgaria — Structural, petrographic and isotope geochronology study. Tectonophysics 2013, 595-596, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.; Satır, M.; Tüysüz, O.; Akyüz, S.; Chen, F. The tectonics of the Strandja Massif: late-Variscan and mid-Mesozoic deformation and metamorphism in the northern Aegean. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2000, 90, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.I. Geology of Turkey: A Synopsus. Anschnitt 2008, 21, 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sunal, G.; Satir, M.; Natal'IN, B.A.; Toraman, E. Paleotectonic Position of the Strandja Massif and Surrounding Continental Blocks Based on Zircon Pb-Pb Age Studies. Int. Geol. Rev. 2008, 50, 519–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.I.; Nikishin, A.M. Tectonic evolution of the southern margin of Laurasia in the Black Sea region. Int. Geol. Rev. 2015, 57, 1051–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattò, S.; Cavazza, W.; Zattin, M.; Okay, A.I. No significant Alpine tectonic overprint on the Cimmerian Strandja Massif (SE Bulgaria and NW Turkey). Int. Geol. Rev. 2017, 60, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machev, P.; Ganev, V.; Klain, L. New LA-ICP-MS U-Pb zircon dating for Strandja granitoids (SE Bulgaria): evidence for two-stage late Variscan magmatism in the internal Balkanides. Turk. J. EARTH Sci. 2015, 24, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ahin, Y.S.; Aysal, N.; Güngör, Y.; Peytcheva, I.; Neubauer, F. Geochemistry and U-Pb zircon geochronology of metagranites in Istanca (Strandja) Zone, NW Pontides, Turkey: Implications for the geodynamic evolution of Cadomian orogeny. Gondwana Res. 2014, 26, 2, 755-771. [Google Scholar]

- Natal’iN, B.A.; Sunal, G.; Gün, E.; Wang, B.; Zhiqing, Y. Precambrian to Early Cretaceous rocks of the Strandja Massif (northwestern Turkey): evolution of a long lasting magmatic arc. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2016, 53, 1312–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladinova, Tz.; Georgieva, M. 2020, New data on the westernmost part of the Sakar unit metamorphic basement, SE Bulgaria Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2020, 81, 3, 105-107. [Google Scholar]

- Sunal, G.; Natal’in, B.A.; Satır, M.; Toraman, E. 2006, Palaeozoic magmatic events in the Strandja Massif, NW Turkey Geodin. Acta 2006, 19, 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Okay, A.I.; Satır, M.; Maluski, H.; Siyako, M.; Monie, P.; Metzger, R.; Akyüz, S. 1996, Paleo- and Neo-Tethyan events in northwestern Turkey: Geologic and geochronologic constraints, In: Yin A, and Harrison TM (editors), The tectonic evolution of Asia: Cambridge University Press United Kingdom, 1996, 420–441 p.

- Georgiev, S.; von Quadt, A.; Heinrich, C.; Peytcheva, I.; Marchev, P. Time evolution of rifted continental arc: Integrated ID-TIMS and LA-ICPMS study of magmatic zircons from the Eastern Srednogorie, Bulgaria. Lithos 2012, 154, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunal, I.; Georgiev, S.; von Quadt, A. U/Pb ID-TIMS dating of zircons from the Sakar-Strandzha Zone: New data and old questions about the Variscan orogeny in SE Europe. In: National Conference “Geosciences 2016” Sofia Bulgarian Geological Society, 71–72 p.

- Pristavova, S.; Tzankova, N.; Gospodinov, N.; Filipov, P. 2019. Petrological study of metasomatic altered granitoids from Kanarata Deposit, Sakar Mountain, southeastern Bulgaria. J. Min. Geol. Sci. 2019, 62, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sałacińska, A.; Gerdjikov, I.; Gumsley, A.; Szopa, K.; Chew, D.; Gawęda, A.; Kocjan, I. Two stages of Late Carboniferous to Triassic magmatism in the Strandja Zone of Bulgaria and Turkey. Geol. Mag. 2021, 158, 2151–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci Şans, B.; Özdamar, Ş.; Esenli, F.; Georgiev, S. First U–Pb zircon and (U-Th)/He apatite ages of the Paleo-Tethys rocks in the Strandja Massif, NW Turkey: implications from newly identified serpentinite body Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natal’in, A.B.; Sunal, G.; Satir, M.; Toraman, E. Tectonics of the Strandja Massif, NW Turkey: History of a Long-Lived Arc at the Northern Margin of Paleo-Tethys. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2012, 21, 755–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounov, A.; Gerdjikov, Ia.; Gumsley, A.; Vangelov, D.; Gumsley, P.A.; Chew, D.; Kristoffersen, M. On the presence of a Variscan metamorphism and deformation in the Sakar Unit of Strandja Massif. Geol. Balc. 2024, 85, 3, 27-30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałacińska, A.; Gerdjikov, I.; Kounov, A.; Chew, D.; Szopa, K.; Gumsley, A.; Kocjan, I.; Marciniak-Maliszewska, B.; Drakou, F. Variscan magmatic evolution of the Strandja Zone (Southeast Bulgaria and northwest Turkey) and its relationship to other north Gondwanan margin terranes. Gondwana Res. 2022, 109, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonev, N.; Filipov, P.; Raicheva, R.; Moritz, R. Evidence of late Paleozoic and Middle Triassic magmatism in the Sakar-Strandzha Zone, SE Bulgaria, Regional geodynamic implications. Int. Geol. Rev. 2021, 64, 1199–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysal, N.; Şahin, S.Y.; Güngör, Y.; Peytcheva, I.; Öngen, S. Middle Permian–early Triassic magmatism in the Western Pontides, NW Turkey: Geodynamic significance for the evolution of the Paleo-Tethys. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2018, 164, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- atalov, G. Triassische kristalline Schiefer und Magmagesteine zwischen Haskovo und Dimitrovgrad C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 1961, 14, 5, 503-506. [Google Scholar]

- Chatalov, G. 1961. Triassic crystalline schists and the granites embedded in them in the area of the villages of Svetlina, Orlov dol, Gradets and Madrets (North of Sakar Mountain). Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. XXII (In Bulgarian with English abstract). 1961, 1, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hagdorn, H.; Göncüoglu, M.C. Early-Middle Triassic echinoderm remains from the Istranca Massif, Turkey. Neues Jahrb. Fur Geol. Und Palaontologie-Abhandlungen 2007, 246, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonev, N.; Chiaradia, M.; Moritz, R. Strontium isotopes reveal Early Devonian to Middle Triassic carbonate sedimentation in the Sakar-Strandzha Zone, SE Bulgaria. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2022, 111, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladinova, Tz.; Georgieva, M.; Cherneva, Z. U-Pb datting of detrital zircons from low-grade metasedimentary rocks in the Klokotnitsa village area, SE Bulgaria, In: Proceedings of the National Conference “GEOSCIENCES 2017”, Sofia, Bulgarian Geological Society, 67–68.

- Vladinova, Tz.; Georgieva, M.; Bosse, V.; Cherneva, Z. U-Pb detrital zircons geochronology from metasedimentary rocks of the Sakar unit, Sakar-Strandzha zone, SE Bulgaria. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2018, 79, 3, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Filipov, P.; Bonev, N.; Raicheva, R.; Chiaradia, M.; Moritz, R. Bracheting the timing of clastic metasediments and marbles from Pirin and Sakar Mts, Bulgaria: Implication of U-Pb geochronology of detritial zircon samples and 87Sr/86Sr of carbonate rocks. In: XXI International Congress of the GBGA, Salburg, Austria, 2018, 158 p.

- Elmas, A.; Yılmaz, İ.; Yiğitbaş, E.; Ullrich, T. A Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous metamorphic core complex, Strandja Massif, NW Turkey. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2010, 100, 6, 1251-1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunal, G.; Satir, M.; Natal'In, B.A.; Topuz, G.; Vonderschmidt, O. Metamorphism and diachronous cooling in a contractional orogen: the Strandja Massif, NW Turkey. Geol. Mag. 2011, 148, 580–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilov, P.; Maliakov, Y.; Balogh, K. K-Ar dating of metamorphic rocks from Strandja massif, SE Bulgaria. Geochem. Mineral. Petrol. (Sofia) 2004, 41, 107–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vladinova, Tz.; Georgieva, M.; Cherneva, Z. Geochemistry of Triassic metasediments from the area of the village of Klokotnitsa, SE Bulgaria,—In: Proceedings of the National Conference “GEOSCIENCES 2016”, Sofia Bulgarian Geological Society, 77–78.

- Chavdarova, S.; Machev, Ph. Amphibolites from Sakar Mountain—geological position and petrological features. In: National Conference “Geosciences 2017” Sofia Bulgarian Geological Society, 49–50.

- Vladinova, Tz.; Georgieva, M.; Peytcheva, I. 2019, U-Pb geochronology and geochemistry of rutiles from metaconglomerate in the Sakar-Strandzha zone, SE Bulgaria. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2019, 80, 3, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bonev, N.; Spikings, R.; Moritz, R. 2020, 40Ar/39Ar constraints for an early Alpine metamorphism of the Sakar unit, Sakar-Strandzha zone, Bulgaria Geol. Mag. 2020, 157, 2106–2112. [Google Scholar]

- Gumsley, A.; Szopa, K.; Chew, D.; Gerdjikov, Ia.; Jokubauskas, P.; Marciniak-Maliszewska, B.; Drakou, F. An Early Cretaceous thermal event in the Sakar unit (Strandja Zone, SE Bulgaria/NW Turkey) revealed based on U-Pb rutile geochronology and Zr-in-rutile thermometry Lithos, 2023, 448–449.

- Kaygısız, E.; Aysal, N.; Yağcıoğlu, K.D. Detrital zircon and rutile U–Pb dating of garnet-mica schist in the Istranca (Strandja) Massif (NW Türkiye): Mineral chemistry and metamorphic conditions. Geochemistry 2024, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanev, S.; Göncüoğlu, M.C.; Gedik, I.; Lakova, I.; Boncheva, I.; Sachanski, V.; Okuyucu, C.; Özgül, N.; Timur, E.; Maliakov, Y.; et al. Stratigraphy, correlations and palaeogeography of Palaeozoic terranes of Bulgaria and NW Turkey: a review of recent data. Geol. Soc. London, Spéc. Publ. 2006, 260, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.I.; Satır, M.; Maluski, H.; Siyako, M.; Monie, P.; Metzger, R.; Akyüz, S. Paleo- and Neo-Tethyan events in northwestern Turkey: Geologic and geochronologic constraints, In: Yin A, and Harrison TM (editors), The tectonic evolution of Asia: Cambridge University Press United Kingdom, 1996, 420–441.

- Puetz, S.J.; Spencer, C.J. Evaluating U-Pb accuracy and precision by comparing zircon ages from 12 standards using TIMS and LA-ICP-MS methods. Geosystems Geoenvironment. 2023, 2, 100177–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- atalov, A.G. Contribution to the stratigraphy and lithology of Sakar-type Triassic (Sakar Mountains, South-east Bulgaria). Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. XLVI 1985, 2, 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhuharov, D. 1968. Proterozoic complex. In: Stratigraphy of Bulgaria. (eds. V. Tsankov, H. Spasov), Science and Art, 1968, 25–62. (In Bulgarian with English abstract).

- Boyanov, I.; Shilyafova, Zh.; Goranov, A.; Ruseva, M.; Nenov, T. Explanatory note to the Geological Map of Bulgaria with a scale of 1:100,000. Map sheet Chirpan. Committee for Geology and Mineral Resources “Geology and Geophysics” AD, 1993, 1–75.

- Schoenherr, J.; Reuning, L.; Hallenberger, M.; Lüders, V.; Lemmens, L.; Biehl, C.B.; Lewin, A.; Leupold, M.; Wimmers, K.; Strohmenger, J.Ch. Dedolomitization: Review and case study of uncommon mesogenetic formation conditions. Earth Sci. Rev. 2018, 185, 780–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flügel, E. Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks, Analysis. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2010, 976.

- Vladinova, Tz.; Georgieva, M. Metamorphic of the westernmost Triassic metasedimentary rocks in the Sakar Unit, Sakar-Strandja Zone. Bulgaria 2022, 73, 4, 353-363. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The continental crust: its composition and evolution. United States: Web. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- McLennan, S.M.; Taylor, S.R. Th and U in sedimentary rocks: crustal evolution and sedimentary recycling. Nature 1980, 285, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S.M.; Taylor, S.R. Sedimentary Rocks and Crustal Evolution: Tectonic Setting and Secular Trends. J. Geol. 1991, 99, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S.M.; Taylor, S.R.; McCulloch, M.T; Maynard, J.B. Geochemical and NdSr isotopic composition of deep-sea turbidites: Crustal evolution and plate tectonic associations. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 1990, 54, 2015–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S.M. Rare Earth Elements in Sedimentary Rocks: Influence of Provenance and Sedimentary Processes. In: Lipin, B.R. and McKay, G.A., Eds., Geochemistry and Mineralogy of Rare Earth Elements, De Gruyter, Berlin, 1989, 169-200.

- Tobia, F.H.; Al-Jaleel, H.S.; Rasul, A.K. Elemental and isotopic geochemistry of carbonate rocks from the Pila Spi Formation (Middle–Late Eocene), Kurdistan Region, Northern Iraq: implication for depositional environment. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganai, A.; Rashid, A.S. 2015, Rare earth element geochemistry of the Permo-Carboniferous clastic sedimentary rocks from Spiti Region, Tethys Himalya: significance of Eu and Ce anomalies. Chin. J. Geochem. 2015, 34, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, P.A.; Leveridge, B.E. Tectonic environment of the Devonian Gramscatho basin, south Cornwall: framework mode and geochemical evidence from turbiditic sandstones. J. Geol. Soc. 1987, 144, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladinova, Tz.; Georgieva, M.; Cherneva, Z.; Cruciani, G. Geochemistry and thermodynamic modelling of low-grade metasedimentary rocks from the Sakar-Strandja region, SE Bulgaria In: Goldschmidt Abstract, 2017, 4101.

- Machev, Ph. , 2007, Coexisting muscovite and paragonite in the metapelites from Sakar and the problem for their equilibrium. Ann. Univ. Sofia, Fac. Geol. Geogr. 2007, 1, 263–282. [Google Scholar]

- Grozdanov, L.; Chatalov, A. Amphibolites from the vicinity of the village of Lessovo, the western parts of the Dervent heights, Southeast Bulgaria C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 1995, 48, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Machev, Ph. Moissanite (SiC) from mica schists from Sakar Mtn—occurrence and petrological significance In: Bulgarian Geological Annual Scientific Conferences, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2011, 67–68.

- Franke, W.; Ballèvre, M.; Cocks, L. ; R.M., Torsvik, T.H.; Żelaźniewicz, A. Variscan Orogeny. Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences Encyclopedia of Geology (Second Edition), 2020, 338–349.

- Cortesogno, L.; Gaggero, L.; Ronchi, A.; Yanev, S. Late orogenic magmatism and sedimentation within Late Carboniferous to Early Permian basins in the Balkan terrane (Bulgaria): geodynamic implications. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2004, 93, 500–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatalov, A. 1995. Petrogtaphy, chemical composition and petrogenesis and protogenesis of upper Paleozoic and Lower Triassic metasediments from the Melnitsa-Srem Horst, Southeastern Bulgaria. Annuaire lʼunversite de Sofia “St. Kliment Ohridksi” Faculte de Geologie et Geographie. 1995, 1, 97–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bonev, N.; Filipov, P.; Raicheva, R.; Moritz, R. Detrital zircon age constraints for Late Permian to Late Triassic clastic sedimentation in the northern-western Sakar-Strandzha Zone, SE Bulgaria. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2021, 111, 495–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, M. , Vladinova, Tz. 2022. Geochemistry of Triassic metasediments from easternmost part of Sakar unit, Sakar-Strandzha Zone, SE Bulgaria. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2022, 83, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naydenov, K.A.; von Quadt, A.; Peytcheva, I.; Sarov, S.; Dimov, D. 2009, U-Pb zircon dating of metamorphic rocks in the region of Kostenets-Kozarsko villages: constraints on the tectonic evolution of the Maritsa strike-slip shear zone. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2009, 70, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Peytcheva, I.; von Quadt, A. The Palaeozoic protoliths of Central Srednogorie, Bulgaria: records in zircons frombasement rocks and Cretaceous magmatites. 5th International Symposium on Eastern Mediterranean Geology, Thessaloniki, Greece, Conference Volume, Extended abstract, 2004, T11-9.

- Gerdzhikov, Ia.; Lazarova, A.; Kunov, A.; Vangelov, D. 2013. Highly metamorphic complexes in Bulgaria Yearb. Univ. Min. Geol. “St. Ivan Rilski” 2013, 56, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Carrigan, C.W.; Mukasa, S.B.; Haydoutov, I.; Kolcheva, K. Age of Variscan magmatism from the Balkan sector of the orogen, central Bulgaria. Lithos 2005, 82, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.I.; Topuz, G. Variscan orogeny in the Black Sea region. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2016, 106, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettijohn, F.; Potter, P.E.; and Siever, R. Sand and Sandstone, Springer, Berlin, 1973.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).