1. Introduction

Identified by the WHO as one of the top ten global health threats, vaccine hesitancy refers to the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines [

1]. This phenomenon is influenced by factors such as misinformation, mistrust of health systems, and cultural beliefs [

2,

3]. It poses a global public health challenge by reducing herd immunity and allowing the resurgence of preventable diseases [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Effective communication strategies and education are critical for addressing these issues and improving vaccine uptake worldwide [

9].

In South Tyrol, Italy, vaccine hesitancy is compounded by unique linguistic and cultural diversity, with a significant portion of the population speaking German or Ladin [

10]. This multilingual environment creates barriers to effective communication between healthcare providers and patients [

11]. In addition, cultural differences influence health beliefs and trust in medical authorities, making it difficult for GPs to effectively communicate the importance of immunization [

12]. These challenges are exacerbated by time constraints and a shortage of GPs, which limit the ability to provide in-depth patient counselling and tailored communication [

13]. The slow development of digital tools and support further complicates their efforts to provide consistent and accessible health information [

14]. These challenges require targeted strategies to improve communication skills and resources to address vaccine hesitancy effectively in this diverse region.

This article proposes strategies to improve the communication between GPs and vaccine-hesitant patients in linguistically and culturally diverse regions. By addressing the communication challenges faced by GPs, it aims to improve immunization campaigns and increase the vaccine uptake.

2. Methods

Data sources for this review included EMBASE and PubMed, which were searched using keywords such as "vaccine hesitancy,” "communication strategies,” "general practitioners,” "South Tyrol,” "cultural diversity, and "public health interventions. “The websites of major health organizations (World Health Organization, European Centre for Disease Control, and Italian Ministry of Health) were also consulted. The search strategy included identification and review of relevant titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text review of selected articles and examination of reference lists for additional studies.

Literature selection was based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria for relevance and quality. Peer-reviewed articles, health organization reports, government publications on vaccine hesitancy, communication strategies, and public health interventions were included, focusing on empirical data and systematic reviews. Articles not written in English, German, or Italian, publications older than 10 years, unless seminal, and studies with limited applicability to South Tyrol were excluded.

3. Results

4.1. Vaccine Hesitancy in South Tyrol

In South Tyrol, vaccine hesitancy is higher among German-speaking communities than among Italian-speaking communities [

15]. Mistrust of health policies, misinformation, and cultural and linguistic barriers are the key factors [

16]. This is exacerbated by the region's unique socio-political landscape, where historical tensions and linguistic diversity affect public health initiatives and vaccination rates [

17]. Specific challenges include lower vaccination rates in rural areas with a higher concentration of German speakers, reflecting broader issues of education and trust in healthcare institutions [

18].

GPs are a particularly important source of health information for the population of this region, particularly among German-speaking communities [

19]. This is evidenced by findings that confirm that friends and health professionals are two important sources of health-related information for the German-speaking population, indicating the special role of GPs in disseminating health information and influencing health behaviors [

20].

International evidence consistently highlights the mistrust of health systems and is a key predictor of vaccine hesitancy [

21]. Studies show that individuals with lower levels of education are more likely to be skeptical about vaccines because of their limited health literacy and greater susceptibility to misinformation [

22]. These global patterns underscore the critical need for targeted interventions to build trust and improve education to increase the vaccine uptake.

3.2. General Practitioners as Trusted Sources

GPs are key to influencing public health behaviors because of their role as trusted and accessible healthcare providers [

23]. They influence vaccination decisions because of their trust in and direct interaction with patients [

24]. Their knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and barriers directly affect their vaccination behavior and recommendations for patients [

25]. GPs with access to scientific and official sources of information and strong communication skills are more confident in recommending vaccines, thereby positively influencing patients' decisions. In addition, addressing barriers, such as misinformation and improving GP communication through targeted training programs, can increase vaccine uptake [

26].

In South Tyrol, GPs are crucial because of the region's linguistic and cultural diversity. They provide tailored and culturally sensitive information for various language groups. However, challenges, such as time constraints and the need for better communication skills, must be addressed. Strengthening GPs through training and resources is essential to reduce vaccine hesitancy and improve public health outcomes.

3.3. Communication Strategies

3.3.1. Overview of Effective Communication

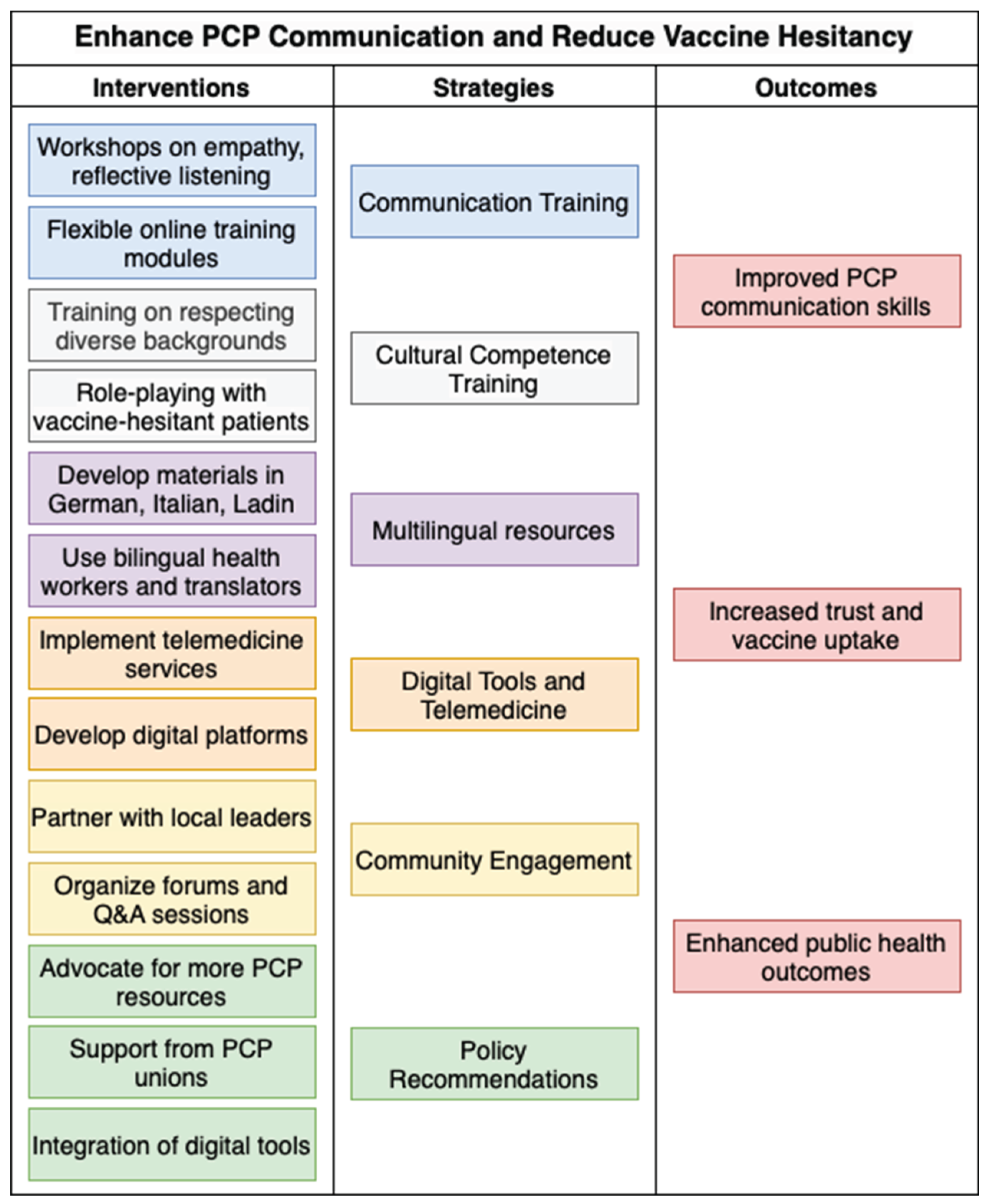

Effective communication strategies are critical for addressing vaccine hesitancy. Details of the strategies used to enhance GP communication skills are presented in

Table 1.

A systematic review by Whitehead et al. [

26] identified several effective communication strategies to counter misinformation regarding vaccines and to improve their uptake. Providing factual corrections and debunking myths effectively reduce beliefs about misinformation [

27]. Disseminating knowledge regarding vaccines through various media sources has increased public awareness. Humor reduces resistance, whereas scientific consensus boosts it. Preemptive warnings about misinformation reduce misperceptions.

3.3.2. Visual Aids, Personalizing the Message, and Enganging in Motivational Interviewing

Visual aids such as charts, infographics, and videos can help convey information more effectively than verbal explanations alone [

28]. In addition, sharing the stories of patients who have benefited from vaccination or have suffered from vaccine-preventable diseases can be powerful in influencing patient decisions. Personal stories and testimonials can humanize the data and make the benefits of immunization more tangible, which allows for connecting with patients on an emotional level [

27].

Personalizing messages that align with patients’ values and beliefs is effective. Discussing the impact of vaccination on the family and community makes conversations more persuasive and ensures that the information is understood and personally felt, thus motivating vaccine uptake. [

29].

Motivational interviewing is a patient-centered technique that encourages patients to express their thoughts about vaccination. This involved open-ended questions that affirmed autonomy. Studies have shown that it significantly increases vaccine acceptance among hesitant individuals, providing clinicians with an effective tool for engaging with these patients [

27,

29].

3.3.3. Challenges in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Regions

GPs face unique challenges in the linguistically and culturally diverse regions of South Tyrol. The study by Ausserhofer et al. [

20] on health information-seeking emphasizes the critical need for tailored communication strategies that address these specific challenges. GPs must be trained to effectively utilize face-to-face consultations to ensure that they can address the individual concerns and circumstances of each patient [

30]. Personalizing the message to align with the patient's values and beliefs ensures that the information is not only understood but also felt at a personal level.

Cultural competence training helps GPs to understand and respect diverse backgrounds, thus providing more effective and empathetic care. This includes the development of multilingual resources tailored to the different literacy levels. Supporting digital tools and telehealth services can enhance communication with accessible and timely information, particularly in multilingual settings.

Ongoing training and professional development are essential. Workshops on advanced communication, cultural competence, and visual aids can improve GPs' engagement with vaccine-hesitant patients. Flexible modules, including online courses and e-learning [

31], fit into busy schedules and keep GPs updated on best practices.

4. Discussion

Effective communication addresses vaccine hesitancy by demonstrating empathy, ensuring transparency, and providing personalized information. Empathy includes understanding and acknowledging patients' concerns, using reflective listening, and building trust through open-ended questions in a nonjudgmental environment. Transparency refers to honestly communicating both the benefits and potential risks of vaccination, thereby reducing beliefs in conspiracies [

32]. Medical communication should be accessible and emotionally engaging, acknowledging fear, while providing accurate information. Addressing the emotional components of vaccine hesitancy and maintaining a stable relationship with trust are critical. Di Lorenzo et al. [

33] recommended using a non-elitist language to effectively reach a wider audience.

Training for GPs should address their communication needs given their limited availability and heavy workload. Flexible modules, including online courses and e-learning platforms, can fit into busy schedules. Workshops on empathy, reflective listening, cultural competence, and hands-on simulations could improve engagement with vaccine-hesitant patients. Incentives and integration of training into regular practice can further motivate family physicians to develop these essential skills.

Additionally, it is essential to provide relevant online information that is easily accessible [

34]. This aligns with requests from GPs in a recent interdisciplinary and interprofessional relational coordination survey in South Tyrol, which emphasized the need for better online information access [

35]. Providing online resources can help overburdened GPs quickly access accurate and up-to-date information, thereby enhancing their ability to effectively communicate with patients.

Attitudes toward vaccination are influenced by science literacy and public health trust. Higher science literacy correlates with positive vaccine attitudes as informed individuals critically evaluate health information and share less unreliable data. Trust in public health institutions is crucial, indicating that both literacy and trust are essential in addressing vaccine hesitancy [

12]. Lower levels of education and health literacy increase susceptibility to misinformation. Hurstak et al. [

22] showed that improving health literacy could enhance vaccine uptake. To support GPs in South Tyrol, relevant information should be made available online with multilingual resources tailored to the region's linguistic diversity [

34]. In addition, school-based health education can significantly improve health literacy and public health outcomes [

36].

High workloads, increased service demands, and bureaucratic requirements have led to general reluctance among GPs to adopt new communication initiatives [

37]. This reluctance is often rooted in the perception of an already excessive workload and a lack of adequate reimbursement for additional services. GP unions, while advocating for better working conditions and remuneration, often prioritize the protection of union members over empowerment through the implementation of innovative healthcare practices [

38]. This focus may inadvertently slow the adoption of effective communication strategies to address vaccine hesitancy.

In addition, the shortage of GPs exacerbates these problems by stretching existing physicians and limiting their ability to provide thorough and empathetic patient counselling [

39]. Policies that fail to address these systemic issues contribute to the ongoing challenge of effectively communicating the importance of immunization. To overcome these barriers, it is essential to develop policies that not only support GPs in their current roles but also incentivize the adoption of new communication practices [

40]. This includes providing adequate financial compensation for additional services, reducing unnecessary bureaucratic tasks, and ensuring sufficient staffing to distribute the workload more evenly.

Proposed Strategy

Addressing vaccine hesitancy and increasing vaccine uptake require comprehensive strategies [

41]. The proposed strategies for enhancing communication skills are summarized in

Figure 1.

Understanding vaccine attitudes, intentions, and behaviors is important, with a focus on building vaccine confidence and identifying the roots of hesitancy. Effective communication techniques include using strong vaccine recommendations and presumptive formats; initiating discussions with clear, assertive statements rather than open-ended questions; and presenting vaccination as the default option [

42]. Motivational interviews are an effective strategy for vaccine-hesitant parents. Specific techniques, such as open-ended questions, affirmations, reflection, and autonomy support, help build trust and encourage vaccination [

32]. The role of GPs and pediatricians in these strategies is important, and cultural competence is essential to address the concerns of diverse populations [

43]. Policy recommendations include the consistent application of policies, such as the dismissal of families who refuse vaccines, with a strong emphasis on ethical considerations, potential impact on attitudes toward vaccines, and trust in the medical system [

42].

The key strategies for improving GP communication and vaccine uptake are as follows:

GPs should provide clear and transparent information about vaccine safety, efficacy, and potential adverse effects, acknowledging the uncertainties in building trust. Empathic communication, including understanding and acknowledging concerns and using reflective listening, is essential. Tailoring information to a patient's medical history, cultural background, and personal concerns makes communication more relevant and persuasive [

32].

Training programs for GPs can enhance their communication skills. Workshops should include empathic communication, reflective listening, clear information, and cultural competencies. Role-playing with actors can provide hands-on experience. To accommodate overburdened GPs, training should be flexible and accessible using online modules, short videos, and interactive e-learning schedules.

Addressing GP workload and motivation is critical. Integrating communication training into CME credits ensures that skills are updated. Financial incentives or recognition can motivate GPs, whereas peer learning groups and mentorship programs can provide ongoing support and encouragement.

Effective communication increases vaccine uptake and implementation of new clinical practices. Five recommendations have been made to facilitate this process. Clearly explain the rationale and benefits of the new practices, provide adequate training, use multiple communication channels, and communicate changes effectively in advance. Allowing feedback and engagement fosters ownership and addresses concerns, helps overcome resistance, and supports implementation [

44].

By adopting these strategies, family physicians can become more effective communicators, reduce vaccine hesitancy, and improve public health outcomes in their communities.

Advocating increased resources for GPs is essential for addressing the challenges faced in South Tyrol. This includes providing financial incentives for GPs involved in vaccine promotion activities and ensuring access to necessary tools and training. Increased funding and support can help manage GP workloads and integrate new communication practices effectively.

Support from GP unions is needed to improve communication skills and reduce bureaucratic burdens on GPs [

45]. By advocating policies that improve working conditions and support innovative healthcare practices, GP unions can help create an environment in which GPs are motivated and able to implement effective vaccine communication strategies.

Promoting the faster adoption of telemedicine services and digital platforms can streamline processes and improve the efficiency of patient care [

46]. Digital tools can help GPs better manage workloads and provide timely and accurate information to patients, enhancing their ability to address vaccine hesitancy and improving overall public health outcomes.

In summary, this narrative review highlights tailored strategies to improve communication between general practitioners and vaccine-hesitant individuals in culturally and linguistically diverse regions. The findings underscore the need for targeted training programs that enhance interpersonal, cultural, and linguistic competencies, supported by policies that reduce workload burdens and incentivize effective communication. Moreover, the integration of telemedicine and digital platforms is essential to facilitate access to accurate vaccine information and improve the reach and efficiency of GPs' vaccination efforts (see

Supplementary Table S1 for a summary of key recommendations).

7. Conclusion

Effective communication strategies are a prerequisite for addressing vaccine hesitancy, especially in diverse regions, such as South Tyrol. By implementing training programs to improve communication skills and cultural competence among GPs, providing multilingual resources, and using digital tools, healthcare providers can engage with vaccine-hesitant patients better. Community engagement through collaboration with local leaders and interactive forums further supports these efforts by promoting trust and open dialogues. Policy recommendations that advocate increased GP resources, support from GP unions, and the integration of digital tools are critical for creating a supportive environment for GPs to implement these strategies. Together, these approaches can significantly improve the vaccine uptake and public health outcomes in South Tyrol.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Summary of key recommendations to support GP communication and vaccine uptake.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E., G.P. and C.J.W.; investigation, C.J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.J.W.; writing—review and editing, G.P. and A.E.; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CME |

Continuing Medical Education |

| EMBASE |

Excerpta Medica Database |

| GP |

General Practitioner |

| PCP |

Primary Care Physician |

| Q&A |

Question and Answer |

References

- World Health Organization Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019 Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Galagali, P.M.; Kinikar, A.A.; Kumar, V.S. Vaccine Hesitancy: Obstacles and Challenges. Curr Pediatr Rep 2022, 10, 241–248. [CrossRef]

- Nuwarda, R.F.; Ramzan, I.; Weekes, L.; Kayser, V. Vaccine Hesitancy: Contemporary Issues and Historical Background. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 1595. [CrossRef]

- Pavić, Ž.; Kovačević, E.; Šuljok, A. Health Literacy, Religiosity, and Political Identification as Predictors of Vaccination Conspiracy Beliefs: A Test of the Deficit and Contextual Models. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2023, 10, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Russell, C.M.; Jankovsky, A.; Cannon, T.D.; Pittenger, C.; Pushkarskaya, H. Information Processing Style and Institutional Trust as Factors of COVID Vaccine Hesitancy. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 10416. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; White, T.M.; Wyka, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Rabin, K.; Larson, H.J.; Martinon-Torres, F.; Kuchar, E.; Abdool Karim, S.S.; Giles-Vernick, T.; et al. Influence of COVID-19 on Trust in Routine Immunization, Health Information Sources and Pandemic Preparedness in 23 Countries in 2023. Nat Med 2024, 30, 1559–1563. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R.M.; St Sauver, J.L.; Finney Rutten, L.J. Vaccine Hesitancy. Mayo Clin Proc 2015, 90, 1562–1568. [CrossRef]

- Haeuser, E.; Byrne, S.; Nguyen, J.; Raggi, C.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Bisignano, C.; Harris, A.A.; Smith, A.E.; Lindstedt, P.A.; Smith, G.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Trends in Routine Childhood Vaccination Coverage from 1980 to 2023 with Forecasts to 2030: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. The Lancet 2025, 0. [CrossRef]

- Jia, M. Language and Cultural Norms Influence Vaccine Hesitancy. Nature 2024, 627. [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Plagg, B.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Vaccine Hesitancy in South Tyrol: A Narrative Review of Insights and Strategies for Public Health Improvement. Ann Ig 2024, 36, 569–579. [CrossRef]

- Slade, S.; Sergent, S.R. Language Barrier. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Keselman, A.; Arnott Smith, C.; Wilson, A.J.; Leroy, G.; Kaufman, D.R. Cognitive and Cultural Factors That Affect General Vaccination and COVID-19 Vaccination Attitudes. Vaccines 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tan, J.-Y. (Benjamin); Liu, X.-L.; Zhao, I. Barriers and Enablers to Implementing Clinical Practice Guidelines in Primary Care: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e062158. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; Torkamani, A.; Butte, A.J.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Schuller, B.; Rodriguez, B.; Ting, D.S.W.; Bates, D.; Schaden, E.; Peng, H.; et al. The Promise of Digital Healthcare Technologies. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1196596. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Lombardo, S.; Ausserhofer, D.; Plagg, B.; Piccoliori, G.; Gärtner, T.; Wiedermann, W.; Engl, A. Vaccine Hesitancy during the Coronavirus Pandemic in South Tyrol, Italy: Linguistic Correlates in a Representative Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 1584. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Lombardo, S.; Gärtner, T.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A.; Wiedermann, C.J. Trust in Conventional Healthcare and the Utilization of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in South Tyrol, Italy: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Ann Ig 2024, 36, 377–391. [CrossRef]

- Peterlini, O. The South-Tyrol Autonomy in Italy: Historical, Political and Legal Aspects. In One Country, Two Systems, Three Legal Orders - Perspectives of Evolution: : Essays on Macau’s Autonomy after the Resumption of Sovereignty by China. Oliveira, J. C., & Cardinal, P. (Eds.).; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 2009 ISBN 978-3-540-68571-5.

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Lombardo, S.; Plagg, B.; Gärtner, T.; Ausserhofer, D.; Wiedermann, W.; Engl, A.; Piccoliori, G. Rural-Urban Disparities in Vaccine Hesitancy among Adults in South Tyrol, Italy. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 1870. [CrossRef]

- Piccoliori, G.; Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Engl, A. Special Roles of Rural Primary Care and Family Medicine in Improving Vaccine Hesitancy. Adv Clin Exp Med 2023, 23, 401–406. [CrossRef]

- Ausserhofer, D.; Wiedermann, W.; Becker, U.; Vögele, A.; Piccoliori, G.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Engl, A. Health Information-Seeking Behavior Associated with Linguistic Group Membership: Latent Class Analysis of a Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey in Italy, August to September 2014. Arch Public Health 2022, 80, 87. [CrossRef]

- Candio, P.; Violato, M.; Clarke, P.M.; Duch, R.; Roope, L.S. Prevalence, Predictors and Reasons for COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Results of a Global Online Survey. Health Policy 2023, 137, 104895. [CrossRef]

- Hurstak, E.E.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Hahn, E.A.; Henault, L.E.; Taddeo, M.A.; Moreno, P.I.; Weaver, C.; Marquez, M.; Serrano, E.; Thomas, J.; et al. The Mediating Effect of Health Literacy on COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence among a Diverse Sample of Urban Adults in Boston and Chicago. Vaccine 2023, 41, 2562–2571. [CrossRef]

- Oberg, E.B.; Frank, E. Physicians’ Health Practices Strongly Influence Patient Health Practices. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2009, 39, 290–291. [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, D.M.; Halperin, B.A.; MacKinnon-Cameron, D.; Li, L.; McNeil, S.A.; Langley, J.M.; Halperin, S.A. The Challenge of Vaccinating Adults: Attitudes and Beliefs of the Canadian Public and Healthcare Providers. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009062. [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Campo, Á.; García-Álvarez, R.M.; López-Durán, A.; Roque, F.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Figueiras, A.; Zapata-Cachafeiro, M. Understanding Primary Care Physician Vaccination Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 13872. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, H.S.; French, C.E.; Caldwell, D.M.; Letley, L.; Mounier-Jack, S. A Systematic Review of Communication Interventions for Countering Vaccine Misinformation. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1018–1034. [CrossRef]

- Marhánková, J.H.; Kotherová, Z.; Numerato, D. Navigating Vaccine Hesitancy: Strategies and Dynamics in Healthcare Professional-Parent Communication. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20. [CrossRef]

- Nuzhath, T.; Spiegelman, A.; Scobee, J.; Goidel, K.; Washburn, D.; Callaghan, T. Primary Care Physicians’ Strategies for Addressing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 333. [CrossRef]

- Melnikow, J.; Padovani, A.; Zhang, J.; Miller, M.; Gosdin, M.; Loureiro, S.; Daniels, B. Patient Concerns and Physician Strategies for Addressing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine 2024, 42, 3300–3306. [CrossRef]

- Alnasir / Alnaser, F. Effective Communication Skills and Patient’s Health. 2020, 3.

- Andrade, M.S.; Alden-Rivers, B. Developing a Framework for Sustainable Growth of Flexible Learning Opportunities. Higher Education Pedagogies 2019, 4, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Schmid, P.; Habersaat, K.B.; Nielsen, S.M.; Seale, H.; Betsch, C.; Böhm, R.; Geiger, M.; Craig, B.; Sunstein, C.; et al. Lessons from COVID-19 for Behavioural and Communication Interventions to Enhance Vaccine Uptake. Commun Psychol 2023, 1, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, A.; Stefanizzi, P.; Tafuri, S. Are We Saying It Right? Communication Strategies for Fighting Vaccine Hesitancy. Front Public Health 2024, 11, 1323394. [CrossRef]

- Editorial. Data Access Needed to Tackle Online Misinformation. Nature 2024, 630, 7–8.

- Piccoliori, G.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Engl, A. The Role of Homogeneous Waiting Group Criteria in Patient Referrals: Views of General Practitioners and Specialists in South Tyrol, Italy. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 985. [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Rina, P.; Barbieri, V.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Integrating a Strategic Framework to Improve Health Education in Schools in South Tyrol, Italy. Epidemiologia 2024, 5, 371–384. [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, N.C.; Blomme, R.J. Burnout among General Practitioners, a Systematic Quantitative Review of the Literature on Determinants of Burnout and Their Ecological Value. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 1064889. [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, P.H. What Makes Workers Happy: Empowerment, Unions or Both? European Journal of Industrial Relations 2019, 25, 363–376. [CrossRef]

- Finset, A.; Ørnes, K. Empathy in the Clinician–Patient Relationship. J Patient Exp 2017, 4, 64–68. [CrossRef]

- van den Bussche, H. Die Zukunftsprobleme der hausärztlichen Versorgung in Deutschland: Aktuelle Trends und notwendige Maßnahmen. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2019, 62, 1129–1137. [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, C.; Wilson, R.; O’Leary, M.; Eckersberger, E.; Larson, H.J. Strategies for Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy – A Systematic Review. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4180–4190. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, S.T.; Opel, D.J.; Cataldi, J.R.; Hackell, J.M.; COMMITTEE ON INFECTIOUS DISEASES; COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE AND AMBULATORY MEDICINE; COMMITTEE ON BIOETHICS Strategies for Improving Vaccine Communication and Uptake. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023065483. [CrossRef]

- Handtke, O.; Schilgen, B.; Mösko, M. Culturally Competent Healthcare – A Scoping Review of Strategies Implemented in Healthcare Organizations and a Model of Culturally Competent Healthcare Provision. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0219971. [CrossRef]

- Albright, K.; Navarro, E.I.; Jarad, I.; Boyd, M.R.; Powell, B.J.; Lewis, C.C. Communication Strategies to Facilitate the Implementation of New Clinical Practices: A Qualitative Study of Community Mental Health Therapists. Transl Behav Med 2022, 12, 324–334. [CrossRef]

- Bureaucracy Busting Concordat: Principles to Reduce Unnecessary Bureaucracy and Administrative Burdens on General Practice Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/bureaucracy-busting-concordat-principles-to-reduce-unnecessary-bureaucracy-and-administrative-burdens-on-general-practice/bureaucracy-busting-concordat-principles-to-reduce-unnecessary-bureaucracy-and-administrative-burdens-on-general-practice (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Barbosa, W.; Zhou, K.; Waddell, E.; Myers, T.; Dorsey, E.R. Improving Access to Care: Telemedicine Across Medical Domains. Annu Rev Public Health 2021, 42, 463–481. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).