Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

8. Future Directions and Broader Implications

9. Multimodal Models and Long-Term Adaptation

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

References

- Reier L, Fowler JB, Arshad M, et al. Optic Disc Edema and Elevated Intracranial Pressure (ICP): A Comprehensive Review of Papilledema. Cureus 2022;14(5):e24915. [CrossRef]

- Orylska-Ratynska M, Placek W, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A. Tetracyclines-An Important Therapeutic Tool for Dermatologists. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19(12). [CrossRef]

- Yasir M, Goyal A, Sonthalia S. Corticosteroid Adverse Effects. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Amandeep Goyal declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Sidharth Sonthalia declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.2025.

- Tan MG, Worley B, Kim WB, Ten Hove M, Beecker J. Drug-Induced Intracranial Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Critical Assessment of Drug-Induced Causes. Am J Clin Dermatol 2020;21(2):163-172. [CrossRef]

- Rigi M, Almarzouqi SJ, Morgan ML, Lee AG. Papilledema: epidemiology, etiology, and clinical management. Eye Brain 2015;7:47-57. [CrossRef]

- Gabros S, Nessel TA, Zito PM. Topical Corticosteroids. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Trevor Nessel declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Patrick Zito declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.2025.

- Trayer J, O'Rourke D, Cassidy L, Elnazir B. Benign intracranial hypertension associated with inhaled corticosteroids in a child with asthma. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14(5). [CrossRef]

- Reifenrath J, Rupprecht C, Gmeiner V, Haslinger B. Intracranial hypertension after rosacea treatment with isotretinoin. Neurol Sci 2023;44(12):4553-4556. [CrossRef]

- Pile HD, Patel P, Sadiq NM. Isotretinoin. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Preeti Patel declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Nazia Sadiq declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.2025.

- Friedman DI. Medication-induced intracranial hypertension in dermatology. Am J Clin Dermatol 2005;6(1):29-37. [CrossRef]

- Gardner K, Cox T, Digre KB. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension associated with tetracycline use in fraternal twins: case reports and review. Neurology 1995;45(1):6-10. [CrossRef]

- Shutter MC, Akhondi H. Tetracycline. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Hossein Akhondi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.2025.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster G, Weiss JS, Bhatia ND, Gold LS, Kircik L. Nonantibiotic Properties of Tetracyclines in Rosacea and Their Clinical Implications. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2021;14(8):14-21. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34840653).

- Hashemian H, Peto T, Ambrosio R, Jr., et al. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmology: An Updated Comprehensive Review. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2024;19(3):354-367. [CrossRef]

- Balyen L, Peto T. Promising Artificial Intelligence-Machine Learning-Deep Learning Algorithms in Ophthalmology. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2019;8(3):264-272. [CrossRef]

- Joseph S, Selvaraj J, Mani I, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence-Based Automated Diabetic Retinopathy Screening in Real-World Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American journal of ophthalmology 2024;263:214-230. [CrossRef]

- Olawade DB, Weerasinghe K, Mathugamage M, et al. Enhancing Ophthalmic Diagnosis and Treatment with Artificial Intelligence. Medicina (Kaunas) 2025;61(3). [CrossRef]

- Tonti E, Tonti S, Mancini F, et al. Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Technology in Glaucoma: A Review. J Pers Med 2024;14(10). [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Wang L, Wu X, et al. Artificial intelligence in ophthalmology: The path to the real-world clinic. Cell Rep Med 2023;4(7):101095. [CrossRef]

- Bajwa J, Munir U, Nori A, Williams B. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: transforming the practice of medicine. Future Healthc J 2021;8(2):e188-e194. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Wang X, Zhang K, et al. Recent advances and clinical applications of deep learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal 2022;79:102444. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Chen W. Solving data quality issues of fundus images in real-world settings by ophthalmic AI. Cell Rep Med 2023;4(2):100951. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Liu L, Ruan S, Li M, Yin C. Are Different Versions of ChatGPT's Ability Comparable to the Clinical Diagnosis Presented in Case Reports? A Descriptive Study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2023;16:3825-3831. [CrossRef]

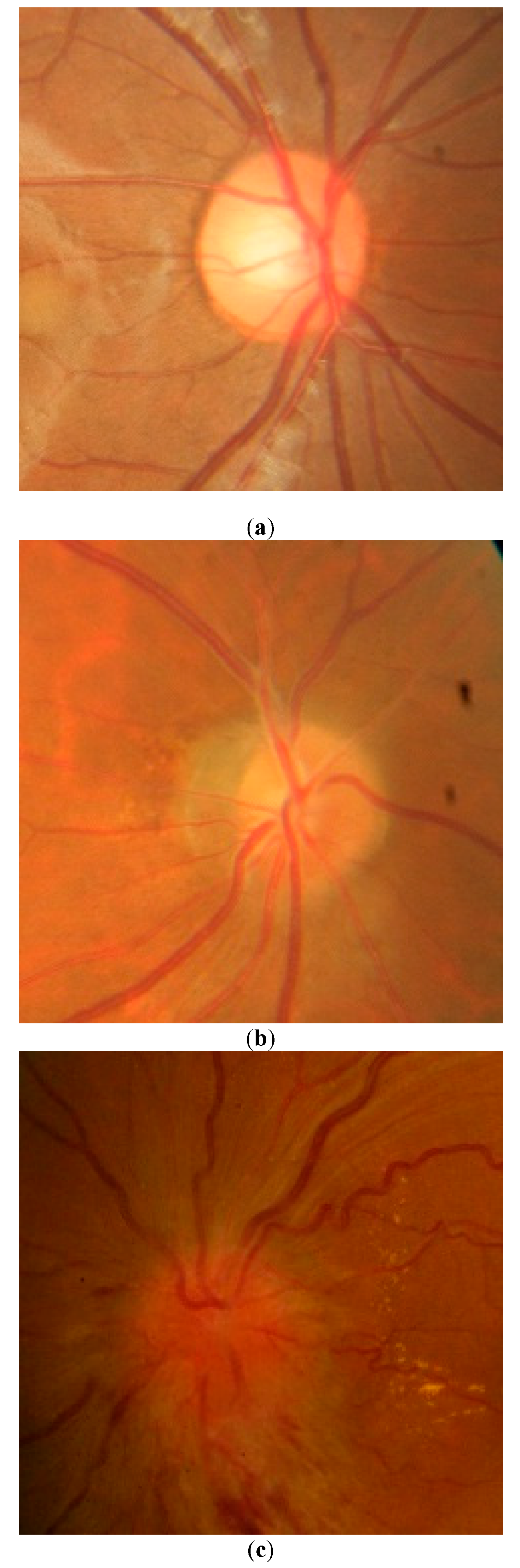

- Sathianvichitr K, Najjar RP, Zhiqun T, et al. A Deep Learning Approach for Accurate Discrimination Between Optic Disc Drusen and Papilledema on Fundus Photographs. J Neuroophthalmol 2024;44(4):454-461. [CrossRef]

- Saba T, Akbar S, Kolivand H, Ali Bahaj S. Automatic detection of papilledema through fundus retinal images using deep learning. Microsc Res Tech 2021;84(12):3066-3077. [CrossRef]

- Milea D, Najjar RP, Zhubo J, et al. Artificial Intelligence to Detect Papilledema from Ocular Fundus Photographs. The New England journal of medicine 2020;382(18):1687-1695. [CrossRef]

- Carla MM, Crincoli E, Rizzo S. RETINAL IMAGING ANALYSIS PERFORMED BY CHATGPT-4o AND GEMINI ADVANCED: The Turning Point of the Revolution? Retina (Philadelphia, Pa 2025;45(4):694-702. [CrossRef]

- Jin K, Ye J. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in ophthalmology: Current status and future perspectives. Adv Ophthalmol Pract Res 2022;2(3):100078. [CrossRef]

- Moraru AD, Costin D, Moraru RL, Branisteanu DC. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in ophthalmology - present and future (Review). Exp Ther Med 2020;20(4):3469-3473. [CrossRef]

- Goktas P, Grzybowski A. Assessing the Impact of ChatGPT in Dermatology: A Comprehensive Rapid Review. J Clin Med 2024;13(19). [CrossRef]

- Cuellar-Barboza A, Brussolo-Marroquin E, Cordero-Martinez FC, Aguilar-Calderon PE, Vazquez-Martinez O, Ocampo-Candiani J. An evaluation of ChatGPT compared with dermatological surgeons' choices of reconstruction for surgical defects after Mohs surgery. Clin Exp Dermatol 2024;49(11):1367-1371. [CrossRef]

- Elias ML, Burshtein J, Sharon VR. OpenAI's GPT-4 performs to a high degree on board-style dermatology questions. Int J Dermatol 2024;63(1):73-78. [CrossRef]

- Ahn JM, Kim S, Ahn KS, Cho SH, Kim US. Accuracy of machine learning for differentiation between optic neuropathies and pseudopapilledema. BMC Ophthalmol 2019;19(1):178. [CrossRef]

- He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)2016:770-778.

- Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li L-J, Li K, Fei-Fei L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition: IEEE; 2009: 248–255.

- Howard J, Ruder S. Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification. Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Melbourne, Australia: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018: 328–339.

- Smith LN. A disciplined approach to neural network hyper-parameters: Part 1 -- learning rate, batch size, momentum, and weight decay. 2018.

- AlRyalat SA, Musleh AM, Kahook MY. Evaluating the strengths and limitations of multimodal ChatGPT-4 in detecting glaucoma using fundus images. Front Ophthalmol (Lausanne) 2024;4:1387190. [CrossRef]

- Leong YY, Vasseneix C, Finkelstein MT, Milea D, Najjar RP. Artificial Intelligence Meets Neuro-Ophthalmology. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2022;11(2):111-125. [CrossRef]

- Biousse V, Najjar RP, Tang Z, et al. Application of a Deep Learning System to Detect Papilledema on Nonmydriatic Ocular Fundus Photographs in an Emergency Department. American journal of ophthalmology 2024;261:199-207. [CrossRef]

- Ruamviboonsuk P, Ruamviboonsuk V, Tiwari R. Recent evidence of economic evaluation of artificial intelligence in ophthalmology. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2023;34(5):449-458. [CrossRef]

- Rau A, Rau S, Zoeller D, et al. A Context-based Chatbot Surpasses Trained Radiologists and Generic ChatGPT in Following the ACR Appropriateness Guidelines. Radiology 2023;308(1):e230970. [CrossRef]

- Savelka J, Ashley KD. The unreasonable effectiveness of large language models in zero-shot semantic annotation of legal texts. Front Artif Intell 2023;6:1279794. [CrossRef]

- Tan W, Wei Q, Xing Z, et al. Fairer AI in ophthalmology via implicit fairness learning for mitigating sexism and ageism. Nature communications 2024;15(1):4750. [CrossRef]

- EyeWiki. Artificial Intelligence in Neuro-Ophthalmology. EyeWiki. December 20, 2023 (https://eyewiki.org/Artificial_Intelligence_in_Neuro-Ophthalmology).

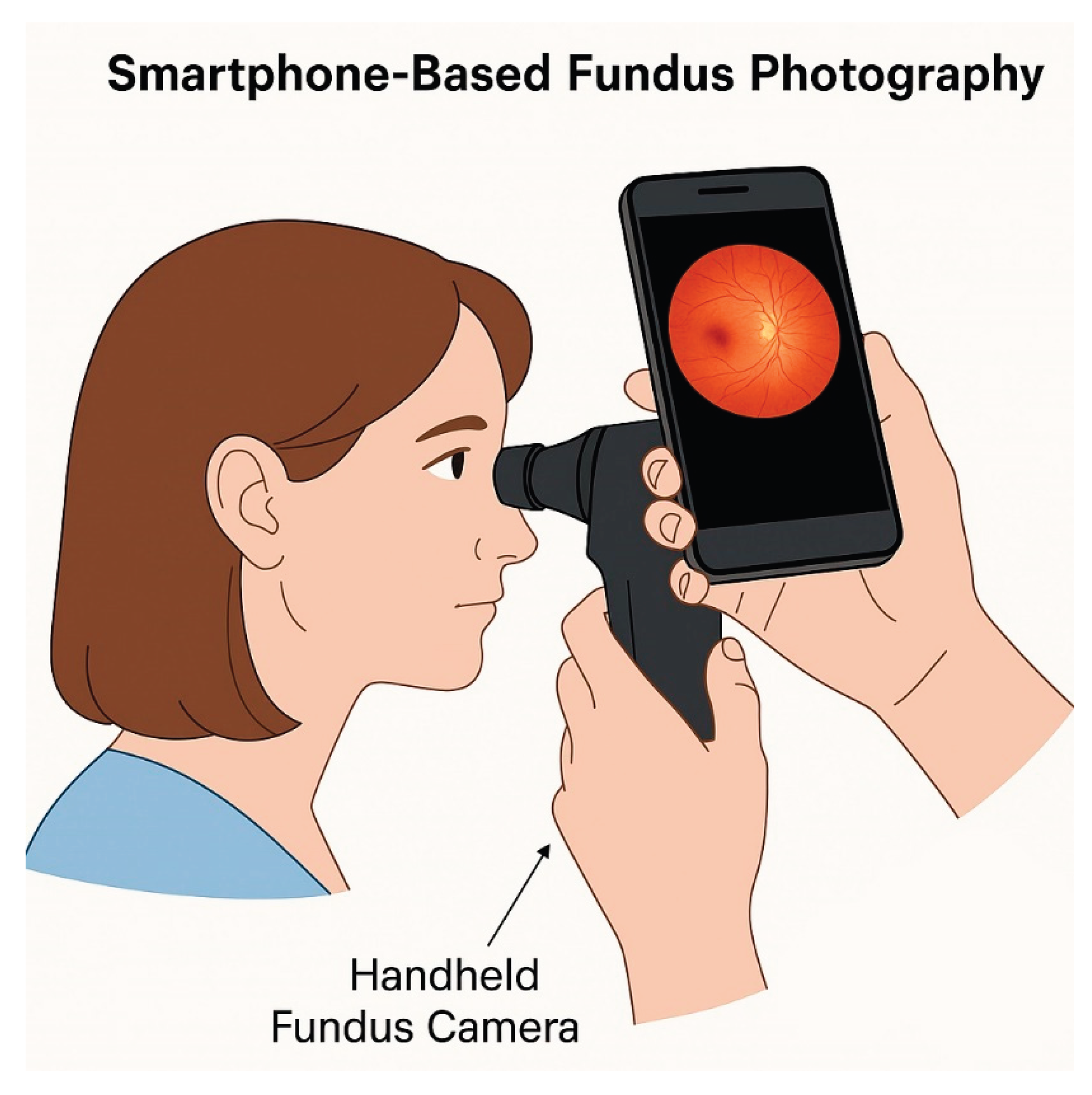

- Kumari S, Venkatesh P, Tandon N, Chawla R, Takkar B, Kumar A. Selfie fundus imaging for diabetic retinopathy screening. Eye (Lond) 2022;36(10):1988-1993. [CrossRef]

- Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37(5):360-3. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15883903).

- Beede, E., Baylor, E., Hersch, F., Iurchenko, A., Wilcox, L., Ruamviboonsuk, P., & Vardoulakis, L. M. (2020). A human-centered evaluation of a deep learning system deployed in clinics for the detection of diabetic retinopathy. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. H., Han, K., & Lee, J. H. (2023). Human-in-the-loop approach to medical AI: Framework and applications. Journal of Digital Imaging, 36(2), 413–423.

- Vickers, A. J., Van Calster, B., & Steyerberg, E. W. (2019). A simple, step-by-step guide to interpreting decision curve analysis. Diagnostic and Prognostic Research, 3, 18. [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, P. J., Kalevar, A., & Liu, I. (2019). Use of smartphone-based fundus photography in clinical practice. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology, 54(1), 16–211.

- He, J., Baxter, S. L., Xu, J., Zhou, X., & Zhang, K. (2019). The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 30–36. [CrossRef]

- Char, D. S., Abràmoff, M. D., & Feudtner, C. (2020). Identifying ethical considerations for machine learning healthcare applications. The American Journal of Bioethics, 20(11), 7–17. [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P., Rinner, C., Apalla, Z., Argenziano, G., Codella, N., Halpern, A., … & Kittler, H. (2020). Human–computer collaboration for skin cancer recognition. Nature Medicine, 26(8), 1229–1234. [CrossRef]

| a. Confusion Matrix for ResNet AI Model in Detecting Papilledema Compared to Ground Truth. | ||||||

| Resnet model P* | Resnet model N** | Total | ||||

| Labeled P | 99 | 0 | 99 | |||

| Labeled N | 1 | 98 | 99 | |||

| Total | 100 | 98 | 198 | |||

| Accuracy (%) | 99.5 | |||||

| Cohen's Kappa | 0.99 | |||||

| b. Confusion Matrix for Senior Ophthalmologists in Detecting Papilledema Compared to Ground Truth | ||||||

| Senior Ophthalmologist P* | Senior Ophthalmologist N** | Total | ||||

| Labeled P | 94 | 5 | 99 | |||

| Labeled N | 3 | 96 | 99 | |||

| Total | 97 | 101 | 198 | |||

| Accuracy (%) | 95.96 | |||||

| Cohen's Kappa | 0.9192 | |||||

| c. Confusion Matrix for Ophthalmology Resident in Detecting Papilledema Compared to Ground Truth | ||||||

| Ophthalmology Resident P* | Ophthalmology Resident N** | Total | ||||

| Labeled P | 93 | 6 | 99 | |||

| Labeled N | 2 | 97 | 99 | |||

| Total | 95 | 103 | 198 | |||

| Accuracy (%) | 95.96 | |||||

| Cohen's Kappa | 0.92 | |||||

| d: Confusion Matrix for GPT-4 Model in Detecting Papilledema Compared to Ground Truth | ||||||

| GPT-4o model P* | GPT-4o model N** | Total | ||||

| Labeled P | 73 | 26 | 99 | |||

| Labeled N | 2 | 97 | 99 | |||

| Total | 75 | 123 | 198 | |||

| Accuracy (%) | 85.86 | |||||

| Cohen's Kappa | 0.72 | |||||

| Evaluator | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Accuracy (%) | Cohen's Kappa |

| ResNet AI | 99.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 98.99 | 99.49 | 0.99 |

| Senior Ophthalmologist | 94.95 | 95.05 | 94.95 | 96.97 | 95.96 | 0.9192 |

| Ophthalmology Resident | 93.94 | 94.17 | 93.94 | 94.17 | 95.96 | 0.92 |

| GPT-4o | 73.74 | 78.86 | 73.74 | 97.98 | 85.86 | 0.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).