1. Introduction

In Germany, out of over 400.000 people suffering from idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease (PD; [

1,

2]), approximately half of them show advanced disease stages according to the Hoehn and Yahr scale (H&Y) with a score ≥ 3 [

3] with several motor and non-motor symptoms relevantly impacting their quality of life [

4,

5]. Following dementia, people with Parkinson’s Disease (PwP) have the highest risk of patients with chronic diseases aged >65 years to become care dependent [

6]. In Germany, about 40% of PwP have a care degree and about every fifth even needs a professional long-term care (LTC) [

7] mainly provided by mobile (outpatient) nursing services, followed by residency in nursing homes and professional domestic 24-hour care [

8]. A current scoping review pointed towards a rather poor care situation of PwP in such LTC facilities in Germany (which is similar to international reports [

9,

10,

11]) and highlighted the need for more detailed analyses of care situation in these institutions due to the lack of data [

7]. So far, for example, there is no information about the quality and quantity of nursing care in LTC facilities in Germany [

7]. Knowledge of LTC nursing staff on PD has earlier been found to be rather poor with the need for more education at least in nursing homes [

12], but - up to now - there is no data about mobile nursing services presenting the most frequently used type of LTC [

8]. In Germany, there are several educational trainings for nursing staff to improve knowledge of nurses regarding PD. These were summarized earlier and range from basic level “Online care school Parkinson” or “Parkinson care specialist” to higher specialized qualifications such as Parkinson assistants (“PASS”) for the outpatient and Parkinson nurses (“PD nurses”) for inpatient settings [

13,

14]. Up to date, there is no data on how often these qualifications are used in LTC settings.

Consequently, this study - using a nation-wide (spread out to participants from all 16 federal states of Germany), anonymous survey evaluating the perspective of LTC nursing staff - aimed to examine the quantity and quality of professional LTC in different LTC settings as well as the nursing staffs’ knowledge about PD.

2. Materials and Methods

We analyzed data from our nationwide, cross-sectoral, survey-based Care4PD study [

15,

16] that was already introduced earlier [

17]. It consisted of two questionnaires that were developed to evaluate the care situation of PwP with focus on LTC – one for PwP (not part of this recent study) and another for nursing staff of LTC facilities. The latter survey contained questions on the nursing staffs’ evaluation of quantity and quality of LTC nursing care as well as their knowledge about PD and their need of PD-specific education or trainings. Study participation was voluntary and anonymous. Single- or multiple-choice questions, graduated (Likert) scales, visual analogue scales (from 0 = not applicable/not at all to 10 = very applicable/very much) and open questions were used (see Supplement). Data collection was performed between August and Dezember 2021.

2.1. LTC Nursing Staff Questionnaire

This questionnaire consisting of 32 questions in total was addressed to nursing staff of LTC facilities. After a testing phase (interviews with five nurses) and consultation of a statistician, the questionnaire was revised, condensed, and optimized to the final version. Questionnaires were distributed nationwide using a link to the online version (created with the online survey tool Unipark by Tivian [

15]) that was sent to about 900 institutions (nursing associations (“Pflegeverbände”), nursing agencies (“Pflegeträger”), labor union (“ver.di”) or supervisors of LTC facilities) for further spreading to their members. We also provided a written version that was distributed via post directly to another 960 randomly selected LTC facilities (7000 copies; mobile nursing services, nursing homes, 24-hour care) and nursing staff working there.

Returned questionnaires were processed identically to our patient survey that was introduced earlier [

8,

18] which means that Unipark results were first exported into Excel to later create an SPSS compatible database. Questionnaires with inconsistent or >30% missing data (n=7) were excluded from analysis.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Questionnaire results are given as number of (n), percentage of (%) participants or means with standard deviation (SD) and range from minimum to maximum. Inner-group comparisons were performed between the subgroups “nursing home” and “mobile nursing services using Student’s t-test for metrical variables (or corrected p-values according to the Welch-Test in case of unequal variances), Mann-Whitney-U test for categorial variable or Pearson’s Chi squared test for binary variables. Correlations were calculated using Spearman’s rho.

3. Results

3.1. Group Characteristics and Nurses’ Experiences with PwP

295 questionnaires were returned, thereof 105 online. Distribution rate was 11.7% for the online version (105/900) and 2.7% for the paper version (190/7000) with a total response rate of 3.7% (295/7900). 288 out of 295 returned nursing staff questionnaires were finally included. Characteristics of participants are described in

Table 1.

To sum up, the predominantly female nursing staff group was middle-aged with a mean about 42 years and with an age span from legal majority to old-age pension, with mostly (79%) registered qualification level (exam after a three-year course of nursing school) and sufficient working experience of in average 18 years (again spanning from beginners to old-stagers). 8% of participants spoke another mother language than German, mainly Polish. About a quarter (26%) of participants worked part-time or in temporary work concepts (travel nurse = “Zeitarbeit”). Only very few institutions focused on care of PwP in the sense of a priority care, but about 44% of participants would desire such concepts.

A total of 95.5% (n=275) nursing staff members reported to have current or previous contact to PwP. Thus, the following analyses focused on these 275 nurses.

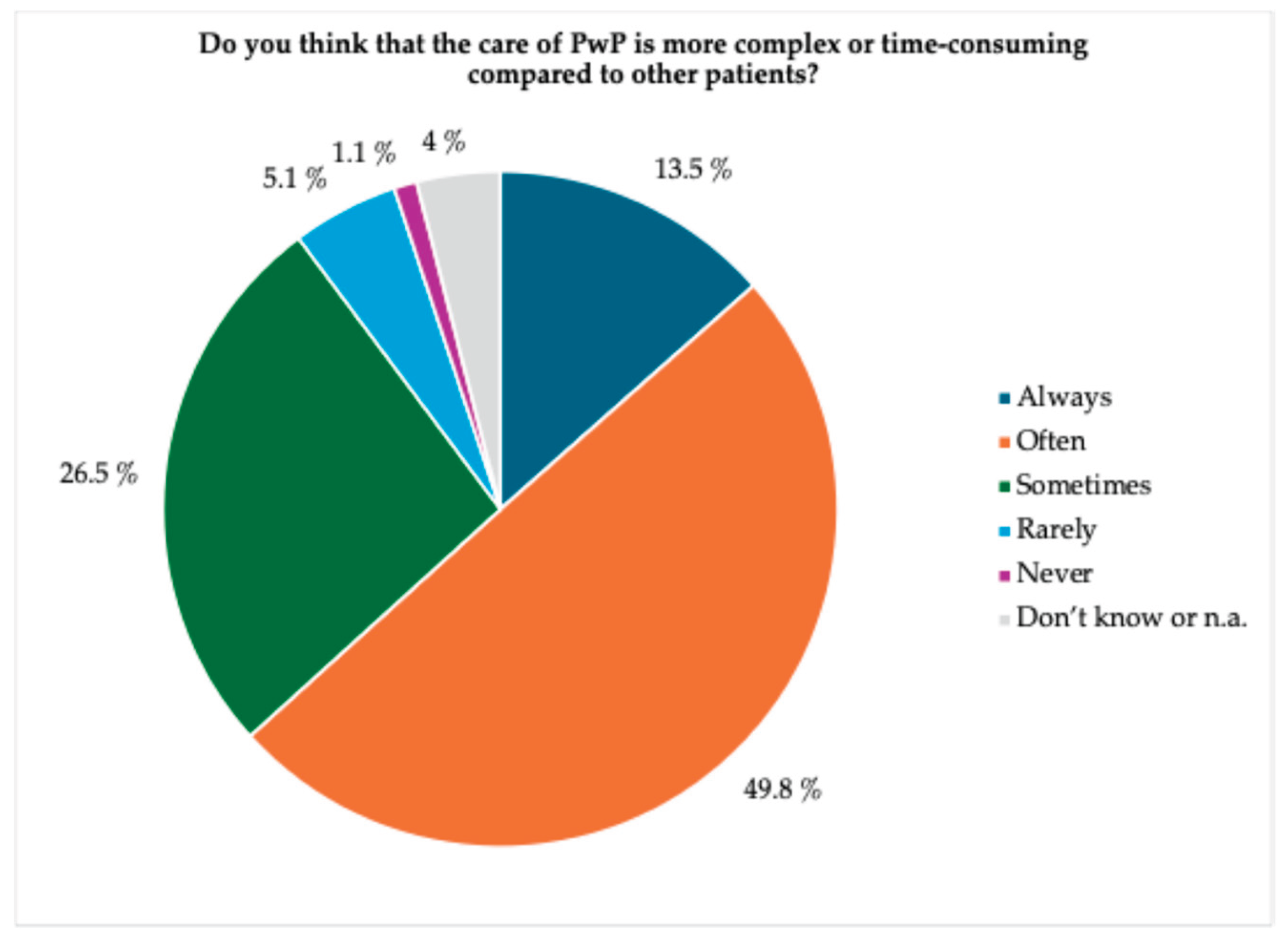

When asked about the complexity and time consumption of care of PwP, over 60% of participants assessed this aspect as always or often high (see

Figure 1).

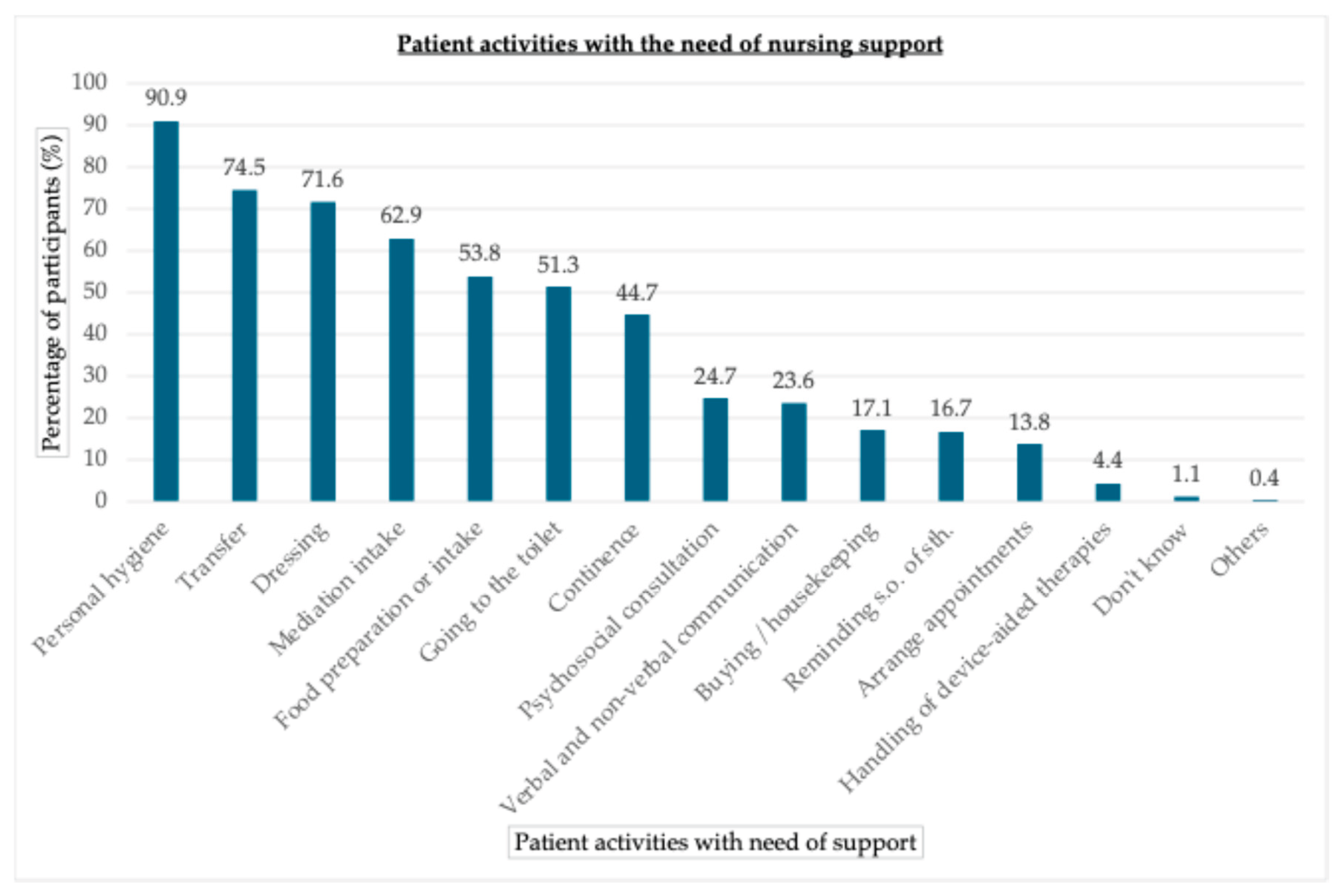

According to nursing participants, PwP need most support regarding personal hygiene, transfer or dressing whereas the handling of device-aided therapies was less important (see

Figure 2).

3.2. Quantity and Quality of Nursing Care in LTC Facilities

Indicators for nursing care quantity and quality in LTC facilities are given in

Table 2.

Regarding care quantity, the nursing staff group reported to support on average 3 PwP per week up to an individual maximum of 15 PwP. Nursing care time was estimated as about 48 minutes per day when including all types of care (especially 24-hour care). When only focusing on the care settings mobile nursing services (MNS) and nursing homes (NH), care time was similar between both (p>0.05). Timely intake of medication was mainly ensured with a score of 7.5 on a scale from 0 = never to 10 = very timely. The existence of a sufficient number of nursing staff members was only reported by about one quarter of nursing participants (“always” or “often” combined) whereas 17% even complained about “never” having enough LTC personnel. About half of the nursing staff reported about “frequently changing” nursing staff. However, a permanent nursing contact person for PwP was reported to be available in about two third of participants and nursing support was felt to be sufficient by half of them (“always” or “often”).

Quality of care was ranked as “adequate” care by most of the nursing participants with, however, about 10% faulting an even “unsafe” care quality in their institution with the occurrence of avoidable complications. Overall care situation was rated as moderate with a ranking of about 6 on a scale from 0=insufficient to 10=optimal.

3.3. Knowledge of LTC Nursing Staff on PD

Nursing staffs’ ratings on their knowledge on PD are depicted in

Table 3 and reveal rather insufficient knowledge on PD symptoms and therapy, especially regarding the handling of intensified device-aided therapies (DBS, pumps). This was even more pronounced when including all participants (n=288) - even those without recent or past contact to PwP (PD symptoms: mean 6.5 [0-10] +/- SD 2.1; PD therapy in general: mean 4.0 [0-10] +/- SD 2.0; handling of device-aided therapies: mean 2.4 [0-10] +/- SD 2.4).

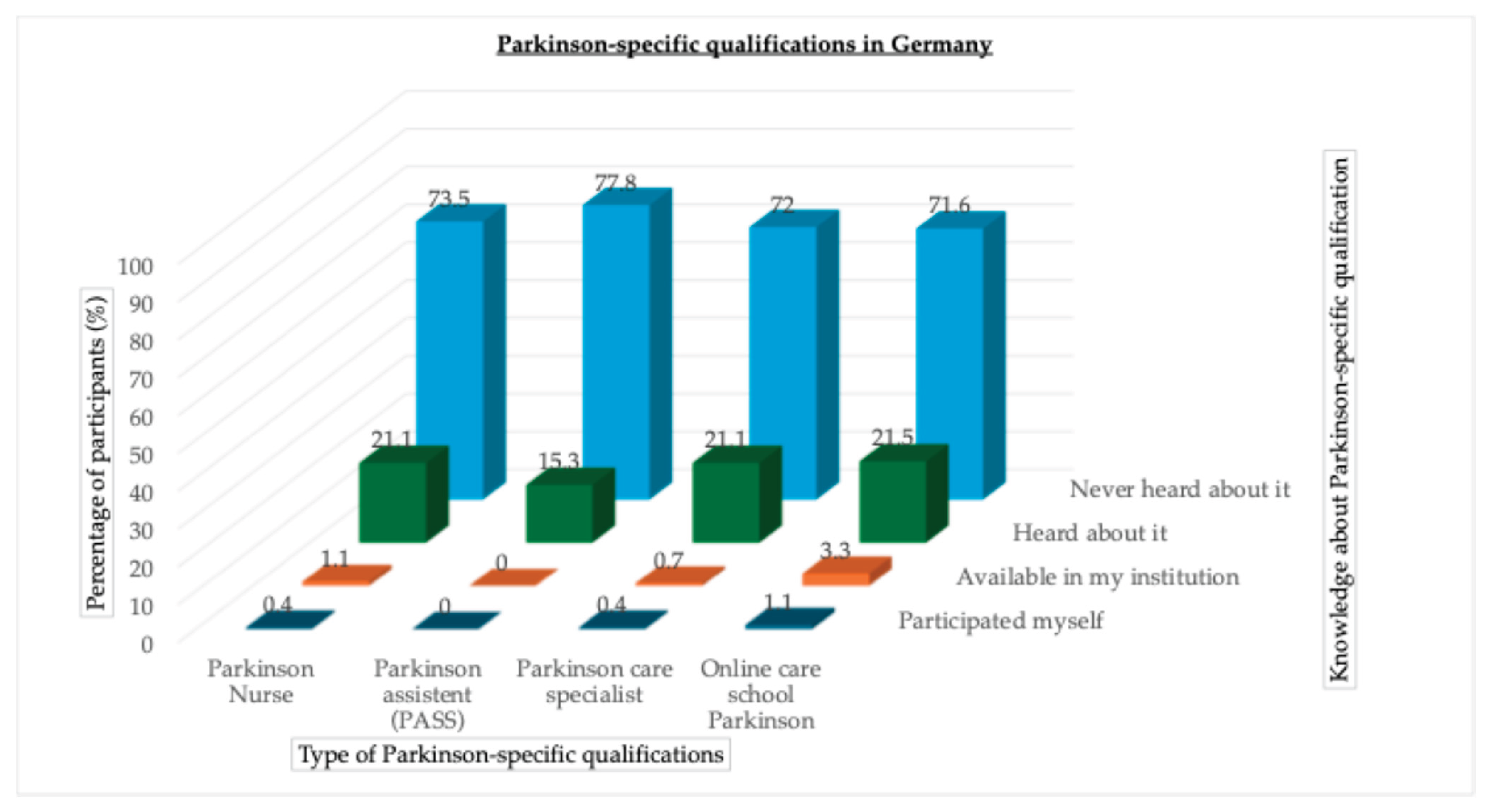

Most participants (>70%) did not know about the existence of PD-specific nursing qualifications (PD Nurse, PD assistant, PD care specialist, PD online care school). Basically PD-qualified nursing staff (absolving PD online care school) was used in about 3% of the participants’ facilities. Specialized PD nurses were only available in 1.1% of facilities (see

Figure 3).

The 4 existing qualification options ranking from specialized (PD Nurse, PASS) to more basic qualification levels (Parkinson care specialist, online care school Parkinson) are shown with percentage of participants (%) knowing or deploying them.

Nursing staff members rated the importance of proper PD-specialized training as rather important (mean 7.0 +/- SD 2.9 [0-10] on a scale from 0=not at all important to 10=very important). When looking at differences between LTC settings, the need for nurses specialized in PD was valuated higher in the NH (mean 5.7 +/- SD 3.3 [0-10], n=46) compared to the MNS (mean 7.7 +/- SD 2.6 [0-10], n=159)) subgroup. Further setting subgroup analyses (MNS vs. NH) revealed no other relevant differences between groups.

3.4. Suggestions How to Optimize LTC in PD

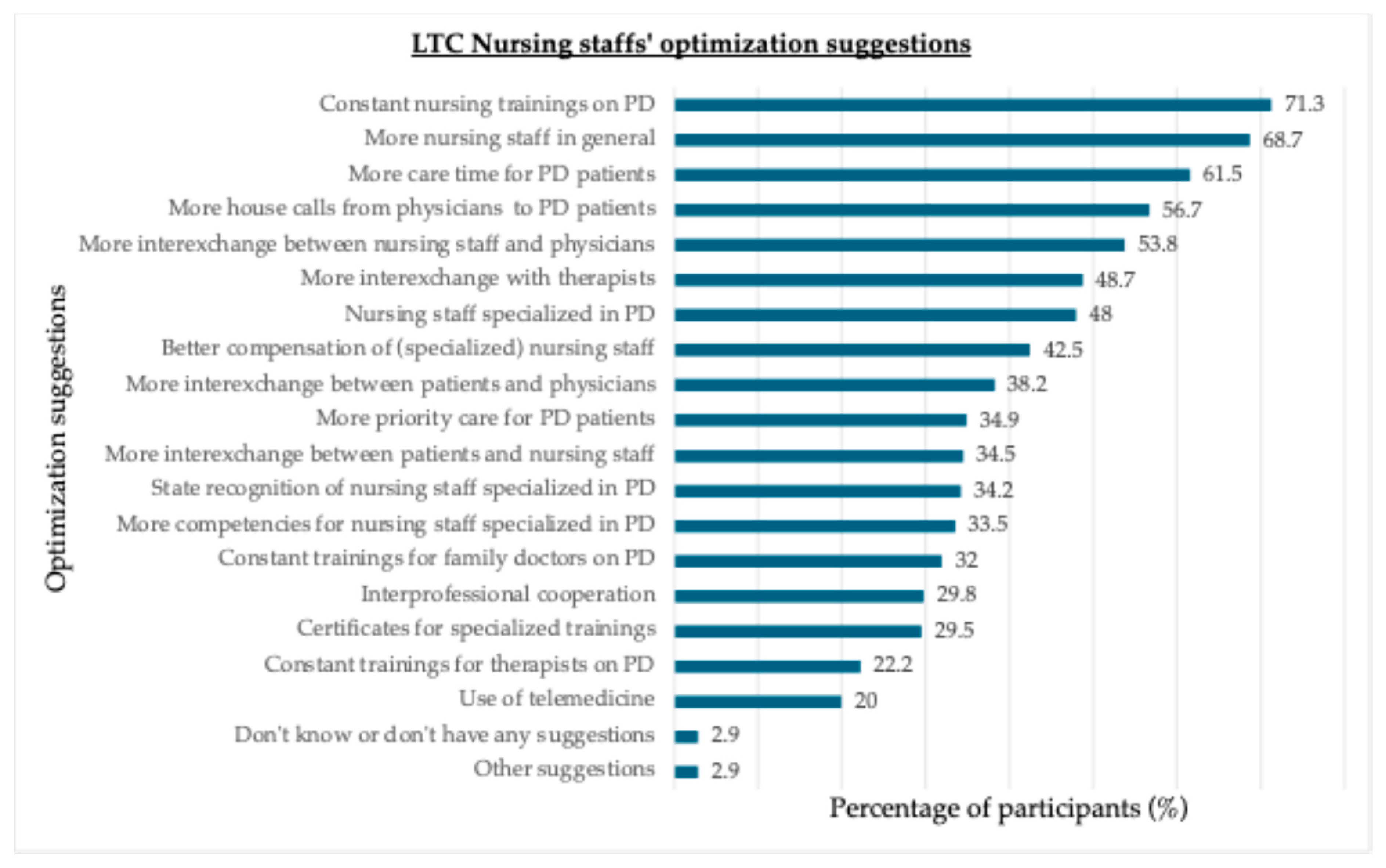

Figure 4 gives an overview on participants’ suggestions (based on predefined, self-developed answering options as well as free text options) of how to optimize LTC in PD. Mainly personnel and time capacities as well as educational aspects and interexchange between nurses and physicians are requested.

3.5. Correlations of Care Quantity and Nursing Staff Knowledge with Care Quality

There was a significant negative correlation (r=-0.416, p<0.001) between the staffing (ranging from 1= “never” to 5 = “always” enough) and care quality evaluations (ranging from 1=“optimal” to 4 =“unsafe”) revealing that care quality enhances with adequate staffing levels. In this study, there was no significant correlation between staffs’ time capacities per person in minutes per day with care quality (r=-0.25, p=0.839). Same was true for LTC nursing staffs (overall) knowledge on PD ranging from 0=none to 10=profound and its correlation with care quality (r=-0.99, p=0.109).

4. Discussion

Our Care4PD study is the first examining indicators for quantity and quality of nursing care of PwP in Germany and presents data on the knowledge of LTC nursing staff on PD and their need and interest in trainings specialized in PD. The overall low response rate of 3.7% lays within the reported range of previous studies [

20]. Acceptance to response online was higher (11.7%) compared to the written version (2.7%). However, number of respondents was acceptable with view to previous studies [

20]. Another distribution method e.g., via directly contacting nurses could possibly have increased response rates [

21].

4.1. Group Characteristics

As shown in

Table 1, we included a representative group of nurses (mainly well examined with a wide range of age and working experience) which allows to get an impression of the overall “everyday life” situation. Nursing staff participants in this study mainly worked in nursing homes (NH), but subgroup analyses revealed no relevant differences between both settings besides the greater need for PD-specialized nurses in nursing homes (NH). Thus, we believe that general care situation is similar for most PwP receiving professional care in “classical settings” such as NH or mobile nursing services (MNS; where most PwP are cared by [

8] and for which - so far - no such data on quantity and quality of care existed). This may be true with the exception of other care settings such as 24-hour care that may benefit from longer and more intensive care, but this aspect cannot be examined further here due to the small sample size for this subgroup.

4.2. Quantity and Quality of Nursing Care in LTC Facilities

Most participants (95.5%) had contact/experience with PD patients in the past or present and participants took care of about 3 PwP per week. Thus, PD seems to be a typical patient profile in LTC facilities again underlining the relevance of PD in this setting [

7,

17,

22,

23]. The need of care was especially high regarding basic activities of daily living such as personal hygiene, transfer or dressing that are all rather complex and time-consuming activities – in particular when factoring in the psychomotor slowness of most PwP [

24]. This might explain why nurses in our study rated the care of PwP as rather complex and time-consuming compared to other LTC patient groups.

Regarding quantity of care, our results indicate a relatively low mean care time per PwP per day of about 50

minutes regardless of the setting (mobile nursing service vs. nursing home). This is very poor compared to data of a previous study showing that families/relatives caring for PwP previously to their transition into an institutionalized care provided about 7.6

hours per day [

25]. Thus, it remains unclear how the time gap is filled: Do the families/relatives still provide the biggest support (which can be assumed at least in the mobile nursing care setting) or are there unfulfilled needs of PwP as no one provides for it? The latter assumption might explain the previous finding that after institutionalization of PwP in nursing homes indeed caregiver burden (and care time) of their relatives decreased but with the disadvantageous outcome of clinical worsening of those institutionalized PwP [

25]. Thus, future nursing care settings should provide for more time and personnel capacities to overcome this care gap.

Speaking of personnel capacities, the current study provides concrete data on mainly insufficient rates of nursing staff with even 17% of participants complaining about “never” having enough personnel in their institution. This may be a result from the nationwide nursing shortage with an approximated lack of nursing staff in Germany of about 280 000 to 690 000 nurses until 2049 [

26]. However, as a positive result of our study it can be extracted, that although both groups reported about frequently changing nursing staff, PwP often still are provided with a permanent nursing contact partner. This is important as a good nurse-patient partnership, that “takes time” to develop, finally can improve “quality of service, treatment outcomes, clients’ safety and satisfaction” and “can [furthermore] encourage clients’ self-management and improve person-centered nursing care” as highlighted by Yuan & Murphy [

27].

Quality of care was mainly ranked as “adequate” by our participants with, however, about 10% of nursing staff reporting about an even “unsafe” care quality in their institution with – regarding to the definition – the “occurrence of avoidable complications”. This is an alarmingly high number and indicates an urgent addressing of this issue. Solutions - and requests from our participants as well - might for example be the provision of proper nursing staff numbers and sufficient time capacities. Although the latter did not significantly correlated with care quality in this study, there was a significant correlation between adequate staffing levels and care quality here. This might prevent from care complications as previous studies have been found that nursing homes with high numbers of registered nurses had lower rehospitalization and emergency department visit rates [

28]. This – in return – might increase PwPs quality of life but may also reduce economical burdens as care complications may result in higher morbidity and hospitalization rates [

29,

30] that might actually be avoided.

Finally, overall care situation was rated as moderate (6 on a scale from 0=insufficient to 10=optimal) with some potential for improvement.

4.3. Knowledge of LTC Nursing Staff on PD

Our results indicate a rather insufficient knowledge of LTC nursing staff on PD symptoms and therapy, especially regarding the handling of intensified device-aided therapies. This might be explained by the fact that neurologic aspects – and PD in particular – are mentioned only marginally – at least during the current generalistic nursing education program in Germany [

14]. To overcome this, integrating a certain “minimal knowledge” on PD into the basic education of nursing staff might be helpful for the future. Furthermore, structured and comprehensive trainings on the LTC job concepts could be helpful to provide nurses with the special knowledge needed regarding relevant (neurologic) diseases in LTC settings.

Additionally, the majority of participants did not know about the existence of trained nursing staff specialized in PD and most LTC facilities did not use them. This is remarkable as advanced training options, such as the PD nurse training, were already implemented in Germany since 2006 [

31]. Others, such as the Online care school Parkinson, are easily accessible online and even free of charge with low admission hurdles. These results are comparable to a previous study showing that rather the existence of specialized PD nurses was known in LT facilities nor were they part of LTC teams for a long time [

12]. However, similar to Mai et al. [

12], in our study the need for specialized LTC nursing staff was rated relatively high with even more importance in the nursing home environment compared to mobile nursing services according to the ratings. To overcome this, the upcoming curriculum for the PD nurse training that was for a long time restricted to inpatient settings plans to also approve LTC staff participation starting in 2026. Also, the already existing training options (PD nurse, PASS, PD specialist, Online care school Parkinson) should be advertised more intensively to reach more LTC personnel. We found that 7% of participants have a university degree. Consideration should be given to developing academic continuing education programs for this target group. Furthermore, providing training and educational material on PD also in other languages (e.g., Polish, Russian) would be helpful as we found a relatively high number of nursing participants (8%) from foreign countries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) findings of the State of the World’s Nursing 2025 (SoWN) report suggest that “1 in 7 nurses worldwide […] are foreign-born, highlighting reliance on international migration”[

32,

33].

All in all, regarding optimization suggestions of our participants, it becomes clear that time and personnel capacities, training options as well as interprofessional exchange were rated as more important as for example state accreditation or certification of training courses or broader competency frameworks. Thus, providing basic working environmental settings should urgently be the priority to optimize nursing care situation of PwP – and probably all people receiving LTC.

5. Conclusions

Data from nursing staff members indicate that PwP are supported by LTC nursing staff on a regular basis. Personnel and time capacities are low with sparse and frequently changing nursing staff (but at least relatively stable permanent contact partners) and only moderate care quality with even 10% of unsafe care promoting avoidable complications – a care situation that is in great need of improvement! Nursing staffs’ expertise on PD is rather low with only minor knowledge about PD therapies in particular as well as about the already existing advanced training options (e.g., PD nurse) although the interest in such trainings was rated as high.

Overall, this results in every 5th patient that does not feel sufficiently supported in everyday life Besides analyzing the special needs of PwP in LTC and providing more personnel and time capacities in general, encouraging more expertise in LTC nursing staff through trainings might additionally optimize care situation of PwP with the need of LTC.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Questionnaire S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: O.F., A.H., T.M., A.A., R.K., M.S; methodology: O.F., A.H., R.K., M.S; formal analysis: O.F., C.K., C.L., A.M.; investigation: O.F., C.K.; writing— original draft preparation: O.F., A.H., T.M.; writing—review and editing: all authors; visualization: O.F., C.K., C.L.; supervision: C.B., A. S., R.K., M.S.; funding acquisition: O.F., M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Prof. Dr. Klaus Thiemann Stiftung (no grant number available).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local Ethics committee of the medical council of Brandenburg (reference number: S10(bB)/2021 with amendment).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable (anonymous and voluntary participation).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank all nurses for their numerous participation that will help to understand and improve care situation of PwP in the future. We also thank our cooperation partners (Deutsche Parkinson Vereinigung e.V., Deutsche Parkinson Hilfe, Bundesverband der kommunalen Senioren- und Behinderteneinrichtungen e.V., FONTIVA Unternehmensgruppe, Berufsverband Deutscher Neurologen), Josephine Green and Beate Schönwald (University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf) for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PwP |

people with Parkinson’s Disease |

| LTC |

Long-term care |

| PD |

Parkinson’s Disease |

| NH |

Nursing home |

| MNS |

Mobile nursing services |

| PD Nurse |

Specialized Parkinson nurse |

| PASS |

Parkinson assistant |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

References

- Heinzel, S.; Berg, D.; Binder, S.; Ebersbach, G.; Hickstein, L.; Herbst, H.; Lorrain, M.; Wellach, I.; Maetzler, W.; Petersen, G.; et al. Do We Need to Rethink the Epidemiology and Healthcare Utilization of Parkinson’s Disease in Germany? Front Neurol 2018, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Parkinson und Bewegungsstörungen. Available online: https://www.parkinson-gesellschaft.de/die-dpg/morbus-parkinson.html (accessed on.

- von Campenhausen, S.; Bornschein, B.; Wick, R.; Botzel, K.; Sampaio, C.; Poewe, W.; Oertel, W.; Siebert, U.; Berger, K.; Dodel, R. Prevalence and incidence of Parkinson’s disease in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2005, 15, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, K.; Nakagawa, R.; Ishido, M.; Yoshinaga, Y.; Watanabe, J.; Hayashi, Y.; Mishima, T.; Fujioka, S.; Tsuboi, Y. Impact of motor and nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson disease for the quality of life: The Japanese Quality-of-Life Survey of Parkinson Disease (JAQPAD) study. J Neurol Sci 2020, 419, 117172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Luengos, I.; Lucas-Jimenez, O.; Ojeda, N.; Pena, J.; Gomez-Esteban, J.C.; Gomez-Beldarrain, M.A.; Vazquez-Picon, R.; Foncea-Beti, N.; Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N. Predictors of health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: the impact of overlap between health-related quality of life and clinical measures. Qual Life Res 2022, 31, 3241–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bussche, H.; Heinen, I.; Koller, D.; Wiese, B.; Hansen, H.; Schafer, I.; Scherer, M.; Glaeske, G.; Schon, G. [The epidemiology of chronic diseases and long-term care: results of a claims data-based study]. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2014, 47, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fründt, O.; Hanff, A.M.; Mai, T.; Warnecke, T.; Wellach, I.; Eggers, C.; van Munster, M.; Dodel, R.; Kirchner, C.; Krüger, R.; et al. Scoping-Review zur stationären Langzeitpflege von Menschen mit idiopathischem Parkinson in Deutschland. DGNeurologie 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frundt, O.; Hanff, A.M.; Mai, T.; Kirchner, C.; Bouzanne des Mazery, E.; Amouzandeh, A.; Buhmann, C.; Kruger, R.; Sudmeyer, M. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on (Health) Care Situation of People with Parkinson’s Disease in Germany (Care4PD). Brain Sci 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarpour, D.; Thibault, D.P.; DeSanto, C.L.; Boyd, C.M.; Dorsey, E.R.; Racette, B.A.; Willis, A.W. Nursing home and end-of-life care in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2015, 85, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerkamp, N.J.; Tissingh, G.; Poels, P.J.; Zuidema, S.U.; Munneke, M.; Koopmans, R.T.; Bloem, B.R. Parkinson disease in long term care facilities: a review of the literature. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014, 15, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rumund, A.; Weerkamp, N.; Tissingh, G.; Zuidema, S.U.; Koopmans, R.T.; Munneke, M.; Poels, P.J.; Bloem, B.R. Perspectives on Parkinson disease care in Dutch nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014, 15, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.; Ketter, A.K. [Residents with Parkinson’s disease in the institutional care : A cross-sectional survey of nursing homes in Germany]. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prell, T.; Siebecker, F.; Lorrain, M.; Tonges, L.; Warnecke, T.; Klucken, J.; Wellach, I.; Buhmann, C.; Wolz, M.; Lorenzl, S.; et al. Specialized Staff for the Care of People with Parkinson’s Disease in Germany: An Overview. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fründt, O.; Kirchner, C.; van Munster, M.; Hanff, A.-M.; Mai, T.; Wellach, I.; Steudter, E.; Dodel, R.; Eggers, C.; Süß, T.; et al. Aus- und Weiterbildung der Parkinsonpflege verbessern. Pflegezeitschrift 2023, 76, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiftung, T. Thiemann Parkinson Care Research - Care4PD Study. Available online: https://thiemannstiftung.de/thiemann-parkinson-care-research/ (accessed on.

- Thiemann Stiftung. Care4PD Study. Available online: https://thiemannstiftung.de/news/care4pd-studie/ (accessed on.

- Fründt, O.; Hanff, A.-M.; Mai, T.; Kirchner, C.; Bouzanne des Mazery, E.; Amouzandeh, A.; Buhmann, C.; Krüger, R.; Südmeyer, M. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on (Health) Care Situation of People with Parkinson’s Disease in Germany (Care4PD). Brain Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frundt, O.; Hanff, A.M.; Mohl, A.; Mai, T.; Kirchner, C.; Amouzandeh, A.; Buhmann, C.; Kruger, R.; Sudmeyer, M. Device-Aided Therapies in Parkinson’s Disease-Results from the German Care4PD Study. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiechter, H.M., M. Pflegeplannung; Recom Verlag: 1998.

- L’Ecuyer, K.M.; Subramaniam, D.S.; Swope, C.; Lach, H.W. An Integrative Review of Response Rates in Nursing Research Utilizing Online Surveys. Nurs Res 2023, 72, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corner, B.; Lemonde, M. Survey techniques for nursing studies. Can Oncol Nurs J 2019, 29, 58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh, M.; Ibrahim, A.K.; Chibnall, J.; Zaidi, B.; Grossberg, G.T. Prevalence of Parkinson disease and Parkinson disease dementia in community nursing homes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013, 21, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.L.; Kiely, D.K.; Kiel, D.P.; Lipsitz, L.A. The epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and natural history of older nursing home residents with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996, 44, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlagsma, T.T.; Koerts, J.; Tucha, O.; Dijkstra, H.T.; Duits, A.A.; van Laar, T.; Spikman, J.M. Mental slowness in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Associations with cognitive functions? J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2016, 38, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, I.; Lescher, E.; Stiel, S.; Wegner, F.; Höglinger, G.; Klietz, M. Analysis of Transition of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease into Institutional Care: A Retrospective Pilot Study. Brain Sci 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (Destatis), S.B. Pressemitteilung - Bis 2049 werden voraussichtlich mindestens 280 000 zusätzliche Pflegekräfte benötigt. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2024/01/PD24_033_23_12.html (accessed on.

- Yuan, S.M., J. Partnership in nursing care: a concept analysis. TMR Integrative Nursing 2019, 3(1), 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburello, H. Impact of Staffing Levels on Safe and Effective Patient Care - Literature Review. 2023.

- Audet, L.A.; Bourgault, P.; Rochefort, C.M. Associations between nurse education and experience and the risk of mortality and adverse events in acute care hospitals: A systematic review of observational studies. Int J Nurs Stud 2018, 80, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Cho, E.; Kim, E.; Lee, K.; Chang, S.J. Effects of registered nurse staffing levels, work environment, and education levels on adverse events in nursing homes. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 21458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T. Status and development of the role as Parkinson Nurse in Germany – an online survey. Pflege (Hogrefe) 2018, 31, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization - Regional Office for Europe, W. Nursing workforce grows, but inequities threaten global health goals. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/12-05-2025-nursing-workforce-grows--but-inequities-threaten-global-health-goals (accessed on.

- WHO, W.H.O.-. State of the world’s nursing 2025 - Investing in education, jobs, leadership and service delivery; Geneva, 2023; p. 166.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).