Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

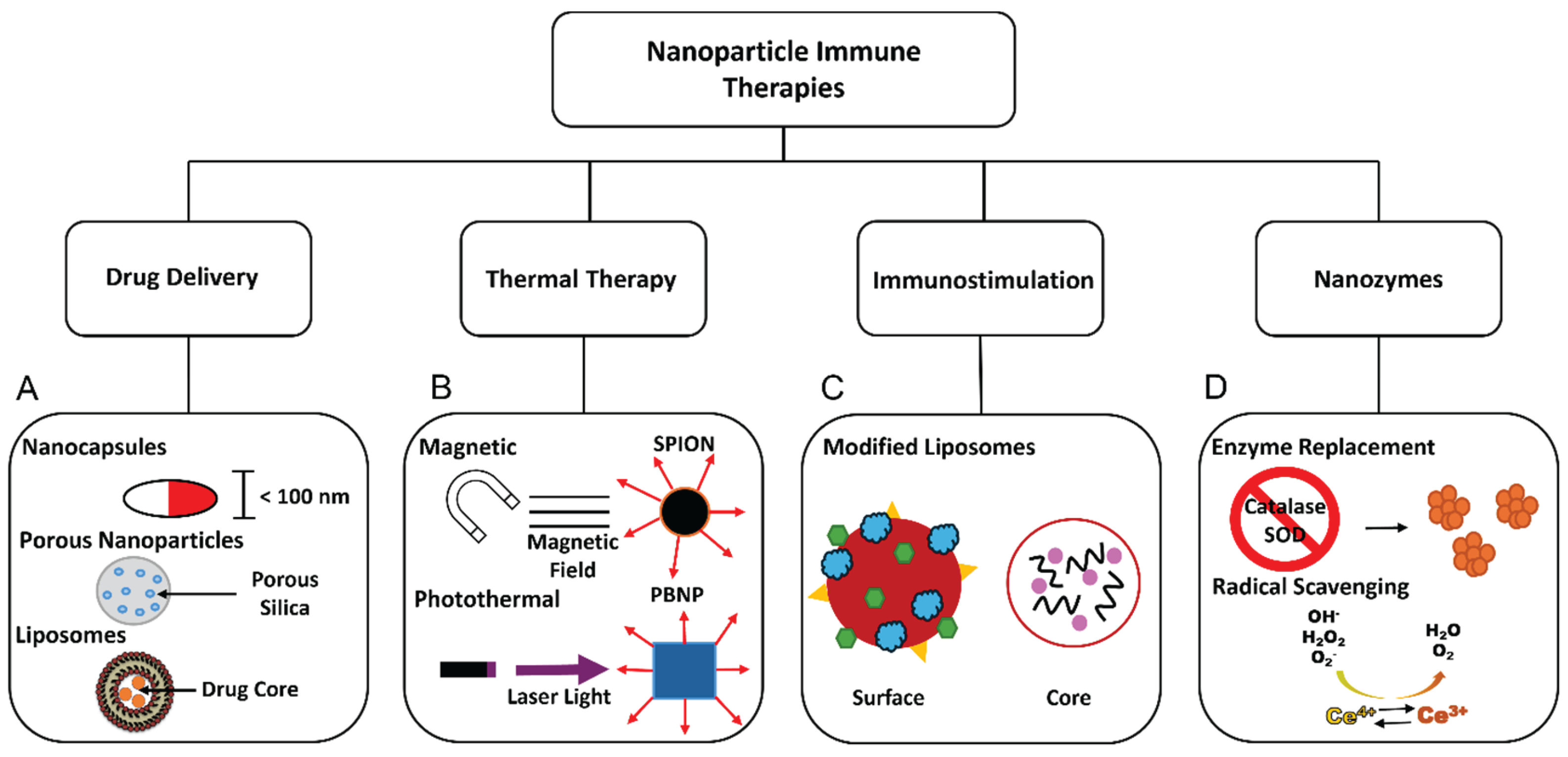

2. Nanoparticles for Immune Applications

3. Nanoceria as Potential Nanomedicine

3.1. Uptake and Localization of Nanoceria

3.2. Factors Affecting Different Activities of Nanoceria

3.3. Enzyme-Mimetic Properties of Nanoceria

3.3.1. SOD-like Activity

3.3.2. CAT-like Activity

3.3.3. OXD-like Activity

3.3.4. POD-like Activity

4. Biomedical Application for Nanoceria

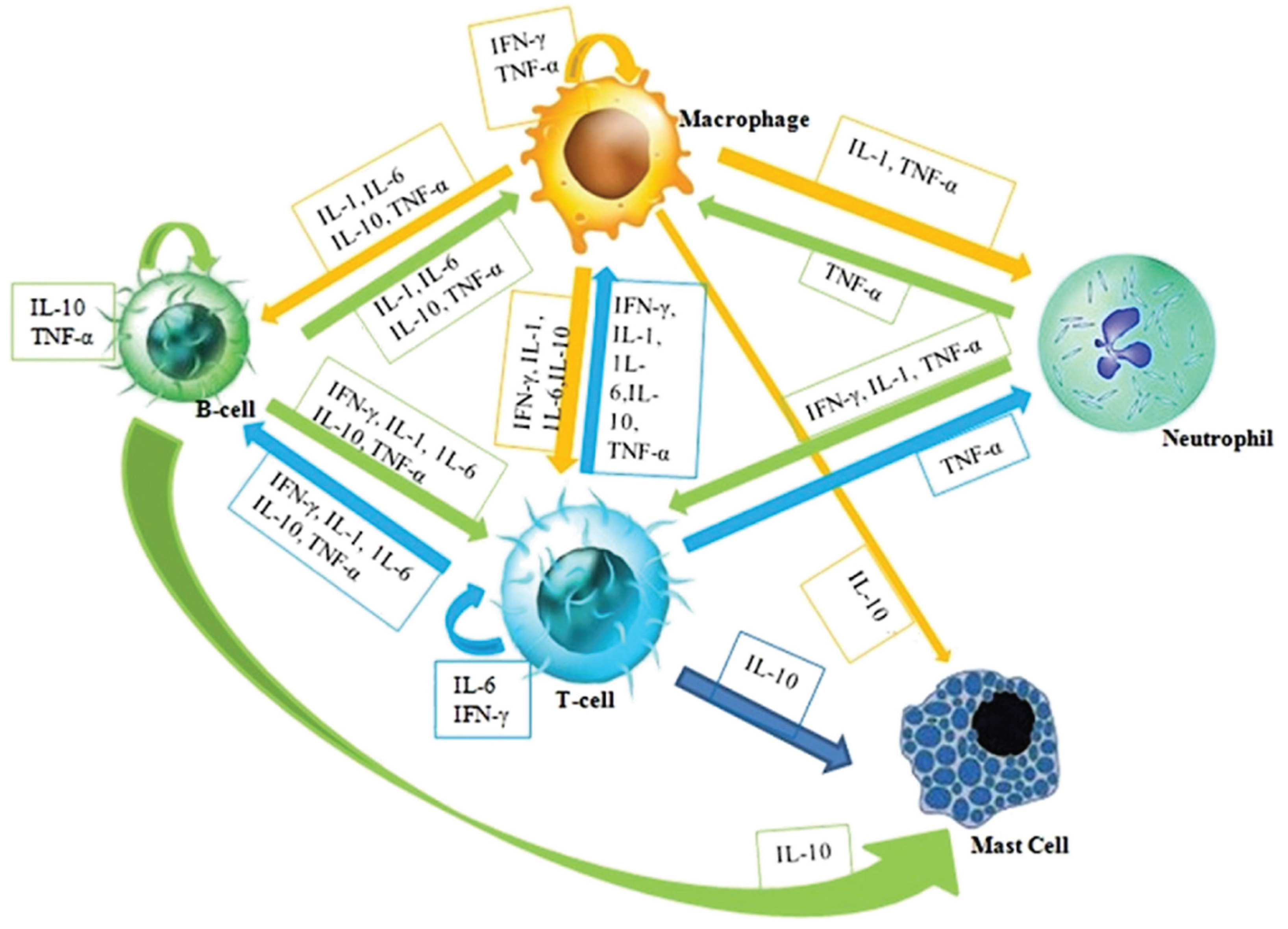

4.1. Nanoceria for Antiinflammation Applications

4.2. Nanoceria for Immunotherapy Applications

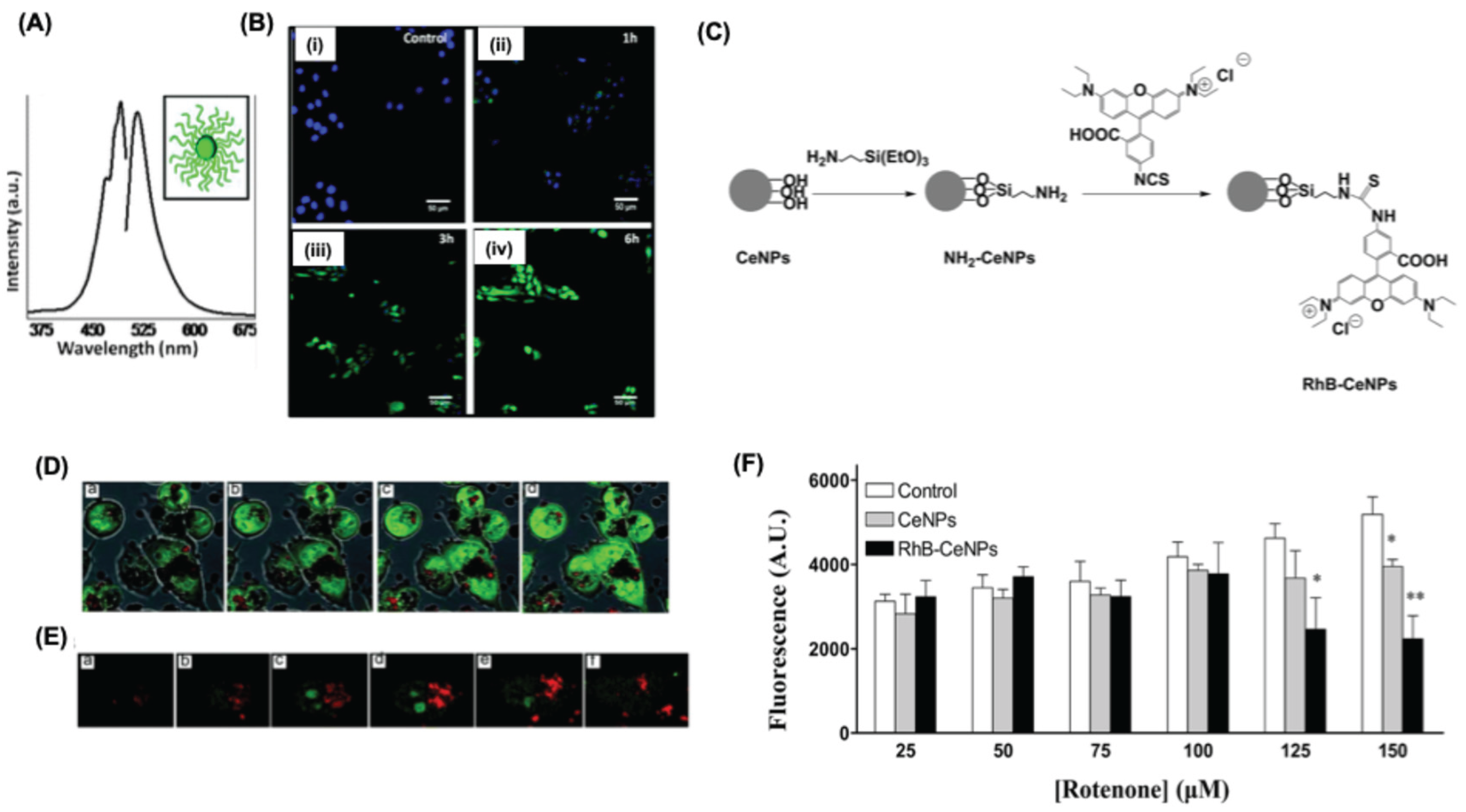

4.3. Theranostic Application of Nanoceria

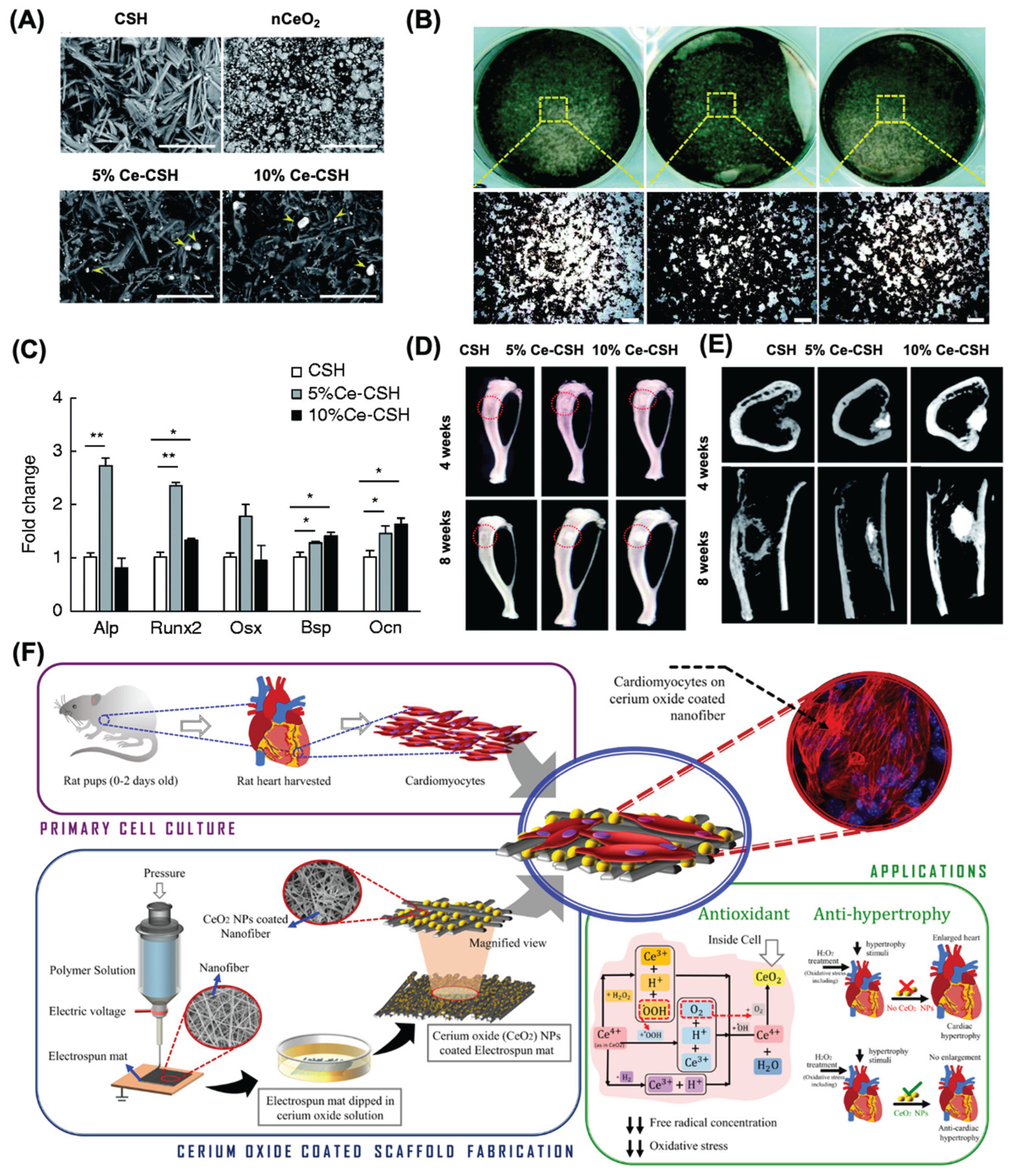

4.4. Nanoceria for Tissue Engineering Applications

| Nano formulation | Role of nanoceria | Cell type | Tissue target | Tissue repiar | Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoceria-incorporated hydroxyapatite (HA) coatings | Additive to scaffold | Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) | Bone | Constructive remodeling | Enhances cell viability and osteogenesis, restores antioxidant defenses and gene expression and inhibits apoptosis, osteoclastogenesis, and oxidative stress. | [188] |

| Cancellous bone containing poly-L-lactic acid and nanoceria | Additive to scaffold | Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) | Bone | Constructive remodeling | Improvement of cell proliferation ; Prevents apoptosis via calcium channel activation and HIF-1α stabilization |

[182] |

| Nanoceria |

Dispersion in medium | BMSCs Bone & adipose | Bone | Constructive remodeling | BMSC viability increased, while osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation were inhibited in a time- and dose-dependent manner | [189] |

| Nanoceria |

Dispersion in medium | Cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) | Heart | Constructive remodeling |

No alteration of the cellular growth and differentiation; Protection of cells against oxidative insults | [190] |

| Citrate-stabilized nanoceria |

Dispersion in medium | Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts | - | Constructive remodeling |

Enhanced proliferative activity of primary cells; Reduction of intracellular ROS during the lag phase of cell growth; Modulation of major antioxidant enzymes | [191] |

| Nanoceria |

Dispersion in medium | Human adipose derived-mesenchymal stem cells (hAd-MSCs) | Skin | Constructive remodeling | Improved tensile strength of acellular dermal matrices impregnated with nanoceria enhances hAd-MSC growth and survival, boosts free radical scavenging, and increases collagen content | [192] |

| Nanoceria & Samarium-doped nanoceria |

Dispersion in medium | Neural progenitor cells | Nerves | Constructive remodeling |

NPs enter cells and temporarily protect against oxidative stress. They hinder neuronal differentiation and disrupt the cytoskeleton, posing neurotoxicity risks. High collagen levels are observed. |

[193] |

4.5. Nanoceria for Wound Healing Applications

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

6. Future Direction and Prospects

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Netea, M.G.; Balkwill, F.; Chonchol, M.; Cominelli, F.; Donath, M.Y.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Golenbock, D.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Heneka, M.T.; Hoffman, H.M.; et al. A guiding map for inflammation. Nature Immunology 2017, 18, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Alysandratos, K.D.; Angelidou, A.; Delivanis, D.A.; Sismanopoulos, N.; Zhang, B.; Asadi, S.; Vasiadi, M.; Weng, Z.; Miniati, A.; et al. Mast cells and inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1822, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margraf, A.; Lowell, C.A.; Zarbock, A. Neutrophils in acute inflammation: current concepts and translational implications. Blood 2022, 139, 2130–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megha, K.B.; Joseph, X.; Akhil, V.; Mohanan, P.V. Cascade of immune mechanism and consequences of inflammatory disorders. Phytomedicine 2021, 91, 153712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seder, R.A.; Ahmed, R. Similarities and differences in CD4+ and CD8+ effector and memory T cell generation. Nature Immunology 2003, 4, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalán, D.; Mansilla, M.A.; Ferrier, A.; Soto, L.; Oleinika, K.; Aguillón, J.C.; Aravena, O. Immunosuppressive Mechanisms of Regulatory B Cells. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 611795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Huang, Y.; Dai, K. TNF-α-induced LRG1 promotes angiogenesis and mesenchymal stem cell migration in the subchondral bone during osteoarthritis. Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, e2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetsanopoulou, A.I.; Alamanos, Y.; Voulgari, P.V.; Drosos, A.A. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Rheumatoid Arthritis Development. Mediterr J Rheumatol 2023, 34, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharja, A.; Mahil, S.K.; Barker, J.N. Psoriasis: a brief overview. Clin Med (Lond) 2021, 21, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henein, M.Y.; Vancheri, S.; Longo, G.; Vancheri, F. The Role of Inflammation in Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, C.R.; Hsu, J.; Tompkins, L.K.; Pennington, A.F.; Flanders, W.D.; Sircar, K. Clinical outcomes among hospitalized US adults with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, with or without COVID-19. J Asthma 2022, 59, 2509–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indicators of Environmental Health Disparites: Childhood Asthma Prevalence. 2023.

- Sartori, A.C.; Vance, D.E.; Slater, L.Z.; Crowe, M. The impact of inflammation on cognitive function in older adults: implications for healthcare practice and research. J Neurosci Nurs 2012, 44, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, Y.; Du, W.; Gong, L.; Chang, H.; Zou, Z. Tumor-associated macrophages: an accomplice in solid tumor progression. Journal of Biomedical Science 2019, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dropulic, L.K.; Lederman, H.M. Overview of Infections in the Immunocompromised Host. Microbiol Spectr 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryer, B.; Feldman, M. Cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 selectivity of widely used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med 1998, 104, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, N.; Kohno, T. Analgesic Effect of Acetaminophen: A Review of Known and Novel Mechanisms of Action. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 580289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.B.; Kasotakis, G.; Haut, E.R.; Miller, A.; Harvey, E.; Hasenboehler, E.; Higgins, T.; Hoegler, J.; Mir, H.; Cantrell, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the treatment of acute pain after orthopedic trauma: a practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma and the Orthopedic Trauma Association. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2023, 8, e001056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghlichloo, I.; Gerriets, V. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Available online: (accessed on.

- Agrawal, S.; Khazaeni, B. Acetaminophen Toxicity. Available online: (accessed on.

- Bindu, S.; Mazumder, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem Pharmacol 2020, 180, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgens, A.; Sharman, T. Corticosteroids. Available online: (accessed on.

- Harvey, J.; Lax, S.J.; Lowe, A.; Santer, M.; Lawton, S.; Langan, S.M.; Roberts, A.; Stuart, B.; Williams, H.C.; Thomas, K.S. The long-term safety of topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis: A systematic review. Skin Health Dis 2023, 3, e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coondoo, A.; Phiske, M.; Verma, S.; Lahiri, K. Side-effects of topical steroids: A long overdue revisit. Indian Dermatol Online J 2014, 5, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.J.; Morris, K.J.; Jayson, M.I. Prednisolone inhibits phagocytosis by polymorphonuclear leucocytes via steroid receptor mediated events. Ann Rheum Dis 1983, 42, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.; Castro, M.; Bourdin, A.; Fucile, S.; Altman, P. Short-course systemic corticosteroids in asthma: striking the balance between efficacy and safety. Eur Respir Rev 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, M.; Hartman, L.; Opris-Belinski, D.; Bos, R.; Kok, M.R.; Da Silva, J.A.; Griep, E.N.; Klaasen, R.; Allaart, C.F.; Baudoin, P.; et al. Low dose, add-on prednisolone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis aged 65+: the pragmatic randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled GLORIA trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2022, 81, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Goyal, A.; Sonthalia, S. Corticosteroid Adverse Effects. Available online: (accessed on.

- Manubolu, S.; Nwosu, O. Exogenous Cushing’s syndrome secondary to intermittent high dose oral prednisone for presumed asthma exacerbations in the setting of multiple emergency department visits. Journal of Clinical and Translational Endocrinology: Case Reports 2017, 6, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjiani, D.; Paul, D.B.; Kunnumpurath, S.; Kaye, A.D.; Vadivelu, N. Availability and utilization of opioids for pain management: global issues. Ochsner J 2014, 14, 208–215. [Google Scholar]

- Dydyk, A.M.; Jain, N.K.; Gupta, M. Opioid Use Disorder. Available online: (accessed on.

- Lyle Cooper, R.; Thompson, J.; Edgerton, R.; Watson, J.; MacMaster, S.A.; Kalliny, M.; Huffman, M.M.; Juarez, P.; Mathews-Juarez, P.; Tabatabai, M.; et al. Modeling dynamics of fatal opioid overdose by state and across time. Prev Med Rep 2020, 20, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awate, S.; Babiuk, L.A.; Mutwiri, G. Mechanisms of action of adjuvants. Front Immunol 2013, 4, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostólico Jde, S.; Lunardelli, V.A.; Coirada, F.C.; Boscardin, S.B.; Rosa, D.S. Adjuvants: Classification, Modus Operandi, and Licensing. J Immunol Res 2016, 2016, 1459394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Gewirtz, D.A. Editorial: Risks and Benefits of Adjuvants to Cancer Therapies. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 913626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, K.; Roudaia, L.; Buhlaiga, N.; Del Rincon, S.V.; Papneja, N.; Miller, W.H., Jr. A review of cancer immunotherapy: from the past, to the present, to the future. Curr Oncol 2020, 27, S87–s97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavón-Romero, G.F.; Parra-Vargas, M.I.; Ramírez-Jiménez, F.; Melgoza-Ruiz, E.; Serrano-Pérez, N.H.; Teran, L.M. Allergen Immunotherapy: Current and Future Trends. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.A.; Dayan, C.M. Immunotherapy for type 1 diabetes. Br Med Bull 2021, 140, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Pang, Y.; Zhou, H. The interaction between nanoparticles and immune system: application in the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle classification, physicochemical properties, characterization, and applications: a comprehensive review for biologists. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothamasu, P.; Kanumur, H.; Ravur, N.; Maddu, C.; Parasuramrajam, R.; Thangavel, S. Nanocapsules: the weapons for novel drug delivery systems. Bioimpacts 2012, 2, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharti, C.; Nagaich, U.; Pal, A.K.; Gulati, N. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in target drug delivery system: A review. Int J Pharm Investig 2015, 5, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos da Silva, A.; Dos Santos, J.H.Z. Stöber method and its nuances over the years. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2023, 314, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, J.S.; Xu, Q.; Kim, N.; Hanes, J.; Ensign, L.M. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2016, 99, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, S.; Ramalho, M.J.; Loureiro, J.A.; Pereira, M.C. Liposomes as biomembrane models: Biophysical techniques for drug-membrane interaction studies. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2021, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J. A Review of Liposomes as a Drug Delivery System: Current Status of Approved Products, Regulatory Environments, and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.A.; Allemailem, K.S.; Almatroodi, S.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Rahmani, A.H. Recent strategies towards the surface modification of liposomes: an innovative approach for different clinical applications. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, P.P.; Biswas, S.; Torchilin, V.P. Current trends in the use of liposomes for tumor targeting. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2013, 8, 1509–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danila, D.; Pardo, P.S.; Misra, R.D.K.; Boriek, A.M. Liposomes as Imaging Agents of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Bone Implants. In Curr Issues Mol Biol; © 2025 by the authors.: 2025; Volume 47.

- Glazer, E.S.; Curley, S.A. The ongoing history of thermal therapy for cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2011, 20, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulińska-Litewka, J.; Łazarczyk, A.; Hałubiec, P.; Szafrański, O.; Karnas, K.; Karewicz, A. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles-Current and Prospective Medical Applications. Materials (Basel) 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli, C.; Moya, S.E.; Lomas, J.S.; Gravier-Pelletier, C.; Briandet, R.; Hémadi, M. Recent advances in nanotechnology for eradicating bacterial biofilm. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2383–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Yue, W.; Cai, S.; Tang, Q.; Lu, W.; Huang, L.; Qi, T.; Liao, J. Improvement of Gold Nanorods in Photothermal Therapy: Recent Progress and Perspective. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 664123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhan, X.; Xiong, J.; Peng, S.; Huang, W.; Joshi, R.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Yuan, K.; et al. Temperature-dependent cell death patterns induced by functionalized gold nanoparticle photothermal therapy in melanoma cells. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, K.L.; Kono, H. The inflammatory response to cell death. Annu Rev Pathol 2008, 3, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Holay, M.; Park, J.H.; Fang, R.H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L. Nanoparticle Delivery of Immunostimulatory Agents for Cancer Immunotherapy. Theranostics 2019, 9, 7826–7848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nsairat, H.; Khater, D.; Sayed, U.; Odeh, F.; Al Bawab, A.; Alshaer, W. Liposomes: structure, composition, types, and clinical applications. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenchov, R.; Bird, R.; Curtze, A.E.; Zhou, Q. Lipid Nanoparticles─From Liposomes to mRNA Vaccine Delivery, a Landscape of Research Diversity and Advancement. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 16982–17015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretiakova, D.S.; Vodovozova, E.L. Liposomes as Adjuvants and Vaccine Delivery Systems. Biochem (Mosc) Suppl Ser A Membr Cell Biol 2022, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pöyhönen, L.; Bustamante, J.; Casanova, J.L.; Jouanguy, E.; Zhang, Q. Life-Threatening Infections Due to Live-Attenuated Vaccines: Early Manifestations of Inborn Errors of Immunity. J Clin Immunol 2019, 39, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, A.; Saxena, K.; Sharma, G.; Rajesh; Sheikh, F.A.; Seth, C.S.; Tripathi, R.M. Nanozymes: A comprehensive review on emerging applications in cancer diagnosis and therapeutics. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 256, 128272. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Hong, W.; Li, G. Highly sensitive electrochemical detection of cholesterol based on Au-Pt NPs/PAMAM-ZIF-67 nanomaterials. Anal Sci 2024, 40, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dai, X.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, H. Nanozymes Regulate Redox Homeostasis in ROS-Related Inflammation. Front Chem 2021, 9, 740607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifi, M.A.; Seal, S.; Godugu, C. Nanoceria, the versatile nanoparticles: Promising biomedical applications. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, A.Y.; Erlichman, J.S. The potential of cerium oxide nanoparticles (nanoceria) for neurodegenerative disease therapy. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2014, 9, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalashnikova, I.; Chung, S.-J.; Nafiujjaman, M.; Hill, M.L.; Siziba, M.E.; Contag, C.H.; Kim, T. Ceria-based nanotheranostic agent for rheumatoid arthritis. Theranostics 2020, 10, 11863–11880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.K.; Kim, T.; Choi, I.Y.; Soh, M.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.J.; Jang, H.; Yang, H.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, H.K.; et al. Ceria nanoparticles that can protect against ischemic stroke. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2012, 51, 11039–11043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.L.; Chung, S.J.; Woo, H.J.; Park, C.R.; Hadrick, K.; Nafiujjaman, M.; Kumar, P.P.P.; Mwangi, L.; Parikh, R.; Kim, T. Exosome-Coated Prussian Blue Nanoparticles for Specific Targeting and Treatment of Glioblastoma. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 20286–20301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Huo, M. Nanozymes-recent development and biomedical applications. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.A.; Gao, J.; Wal, R.V.; Gigliotti, A.; Burchiel, S.W.; McDonald, J.D. Pulmonary and systemic immune response to inhaled multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Toxicol Sci 2007, 100, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.A.; Lauer, F.T.; Burchiel, S.W.; McDonald, J.D. Mechanisms for how inhaled multiwalled carbon nanotubes suppress systemic immune function in mice. Nat Nanotechnol 2009, 4, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, A.V.; Shurin, G.V.; Shurin, M.R.; Kisin, E.R.; Murray, A.R.; Young, S.H.; Star, A.; Fadeel, B.; Kagan, V.E.; Shvedova, A.A. Direct effects of carbon nanotubes on dendritic cells induce immune suppression upon pulmonary exposure. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 5755–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Koike, E.; Yanagisawa, R.; Hirano, S.; Nishikawa, M.; Takano, H. Effects of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on a murine allergic airway inflammation model. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2009, 237, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Podila, R.; Shannahan, J.H.; Rao, A.M.; Brown, J.M. Intravenously delivered graphene nanosheets and multiwalled carbon nanotubes induce site-specific Th2 inflammatory responses via the IL-33/ST2 axis. Int J Nanomedicine 2013, 8, 1733–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.J.; Bateman, H.R.; Stover, A.; Gomez, G.; Norton, S.K.; Zhao, W.; Schwartz, L.B.; Lenk, R.; Kepley, C.L. Fullerene nanomaterials inhibit the allergic response. J Immunol 2007, 179, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, N.; Luh, T.Y.; Chou, C.K.; Wu, J.J.; Lin, Y.S.; Lei, H.Y. Inhibition of group A streptococcus infection by carboxyfullerene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001, 45, 1788–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, W.S.; Cho, M.; Jeong, J.; Choi, M.; Cho, H.Y.; Han, B.S.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.O.; Lim, Y.T.; Chung, B.H. Acute toxicity and pharmacokinetics of 13 nm-sized PEG-coated gold nanoparticles. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2009, 236, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parween, S.; Gupta, P.K.; Chauhan, V.S. Induction of humoral immune response against PfMSP-1(19) and PvMSP-1(19) using gold nanoparticles along with alum. Vaccine 2011, 29, 2451–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Vanoirbeek, J.A.; Luyts, K.; De Vooght, V.; Verbeken, E.; Thomassen, L.C.; Martens, J.A.; Dinsdale, D.; Boland, S.; Marano, F.; et al. Lung exposure to nanoparticles modulates an asthmatic response in a mouse model. Eur Respir J 2011, 37, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkilany, A.M.; Murphy, C.J. Toxicity and cellular uptake of gold nanoparticles: what we have learned so far? J Nanopart Res 2010, 12, 2313–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, D.; Yang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Fang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Tian, L.; Lin, B.; Yan, J.; et al. Comparative study of respiratory tract immune toxicity induced by three sterilisation nanoparticles: silver, zinc oxide and titanium dioxide. J Hazard Mater 2013, 248-249, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Tian, X.; Song, X.; Li, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Nie, G. Nanoparticle-induced exosomes target antigen-presenting cells to initiate Th1-type immune activation. Small 2012, 8, 2841–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Shi, J.; Feng, W.; Nie, G.; Zhao, Y. Exosomes as extrapulmonary signaling conveyors for nanoparticle-induced systemic immune activation. Small 2012, 8, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.C.; Liang, H.J.; Wang, C.C.; Liao, M.H.; Jan, T.R. Iron oxide nanoparticles suppressed T helper 1 cell-mediated immunity in a murine model of delayed-type hypersensitivity. Int J Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 2729–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, M.; Langonné, I.; Huguet, N.; Guichard, Y.; Goutet, M. Iron oxide particles modulate the ovalbumin-induced Th2 immune response in mice. Toxicol Lett 2013, 216, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingard, C.J.; Walters, D.M.; Cathey, B.L.; Hilderbrand, S.C.; Katwa, P.; Lin, S.; Ke, P.C.; Podila, R.; Rao, A.; Lust, R.M.; et al. Mast cells contribute to altered vascular reactivity and ischemia-reperfusion injury following cerium oxide nanoparticle instillation. Nanotoxicology 2011, 5, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, A.; Rao, P.J.; Selvam, G.; Murthy, P.B.; Reddy, P.N. Acute inhalation toxicity of cerium oxide nanoparticles in rats. Toxicol Lett 2011, 205, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanan-Khan, A.; Szebeni, J.; Savay, S.; Liebes, L.; Rafique, N.M.; Alving, C.R.; Muggia, F.M. Complement activation following first exposure to pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): possible role in hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Oncol 2003, 14, 1430–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, C.L.; LeMasurier, J.S.; Belz, G.T.; Scalzo-Inguanti, K.; Yao, J.; Xiang, S.D.; Kanellakis, P.; Bobik, A.; Strickland, D.H.; Rolland, J.M.; et al. Inert 50-nm polystyrene nanoparticles that modify pulmonary dendritic cell function and inhibit allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol 2012, 188, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerium. Available online: (accessed on.

- Xu, C.; Qu, X. Cerium oxide nanoparticle: a remarkably versatile rare earth nanomaterial for biological applications. NPG Asia Materials 2014, 6, e90–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, S.; Frolov, D.D.; Masunov, A.E.; Seal, S. Structure and properties of cerium oxides in bulk and nanoparticulate forms. 2014, 584, 199-208.

- Hirst, S.M.; Karakoti, A.S.; Tyler, R.D.; Sriranganathan, N.; Seal, S.; Reilly, C.M. Anti-inflammatory properties of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Small 2009, 5, 2848–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, P.; Pal, S.; Seehra, M.S.; Shi, Y.; Eyring, E.M.; Ernst, R.D. Concentration of Ce 3+ and Oxygen Vacancies in Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Chemistry of Materials 2006, 18, 5144–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafun, J.-D.; Kvashnina, K.O.; Casals, E.; Puntes, V.F.; Glatzel, P. Absence of Ce 3+ Sites in Chemically Active Colloidal Ceria Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 10726–10732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.; Patil, S.; Kuchibhatla, S.V.N.T.; Seal, S. Size dependency variation in lattice parameter and valency states in nanocrystalline cerium oxide. Applied Physics Letters 2005, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celardo, I.; De Nicola, M.; Mandoli, C.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Traversa, E.; Ghibelli, L. Ce 3+ Ions Determine Redox-Dependent Anti-apoptotic Effect of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2011, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, X.; Gao, X.; Zhao, Y. Simultaneous enzyme mimicking and chemical reduction mechanisms for nanoceria as a bio-antioxidant: a catalytic model bridging computations and experiments for nanozymes. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 13289–13299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, K.; Huang, J.; Xiao, K. Uptake, distribution, clearance, and toxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles with different sizes and coatings. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, A.; Emami, J.; Tuszynski, J.A.; Lavasanifar, A. The Uniqueness of Albumin as a Carrier in Nanodrug Delivery. Mol Pharm 2021, 18, 1862–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, A.; Karakoti, A.; Seal, S.; Self, W.T. Unveiling the mechanism of uptake and sub-cellular distribution of cerium oxidenanoparticles. Molecular Biosystems 2010, 6, 1813–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolova, N.; Rovira-Llopis, S.; Baldoví, H.G.; Navalon, S.; Asiri, A.M.; Victor, V.M.; Garcia, H.; Herance, J.R. Ceria nanoparticles with rhodamine B as a powerful theranostic agent against intracellular oxidative stress. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 79423–79432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.L.Y.; Moonshi, S.S.; Ta, H.T. Nanoceria: an innovative strategy for cancer treatment. Cell Mol Life Sci 2023, 80, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, M.S.; Jung, M.; Teoh, W.Y.; Gunawan, C.; Vassie, J.A.; Amal, R.; Whitelock, J.M. Cellular uptake and reactive oxygen species modulation of cerium oxide nanoparticles in human monocyte cell line U937. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 7915–7924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassie, J.A.; Whitelock, J.M.; Lord, M.S. Endocytosis of cerium oxide nanoparticles and modulation of reactive oxygen species in human ovarian and colon cancer cells. Acta Biomater 2017, 50, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.S.; Song, W.; Cho, M.; Puppala, H.L.; Nguyen, P.; Zhu, H.; Segatori, L.; Colvin, V.L. Antioxidant Properties of Cerium Oxide Nanocrystals as a Function of Nanocrystal Diameter and Surface Coating. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9693–9703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Sandberg, A.; Heckert, E.; Self, W.; Seal, S. Protein adsorption and cellular uptake of cerium oxide nanoparticles as a function of zeta potential. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 4600–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asati, A.; Santra, S.; Kaittanis, C.; Perez, J.M. Surface-Charge-Dependent Cell Localization and Cytotoxicity of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 5321–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Huang, W.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Q. Redox enzyme-mimicking activities of CeO(2) nanostructures: Intrinsic influence of exposed facets. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 35344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubernatorova, E.O.; Liu, X.; Othman, A.; Muraoka, W.T.; Koroleva, E.P.; Andreescu, S.; Tumanov, A.V. Europium-Doped Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Limit Reactive Oxygen Species Formation and Ameliorate Intestinal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Adv Healthc Mater 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Du, Y.; Fu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Gao, X.; Guo, X.; Wei, J.; Yang, Y. Ceria-Based Nanozymes in Point-of-Care Diagnosis: An Emerging Futuristic Approach for Biosensing. ACS Sensors 2023, 8, 4442–4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornatska, M.; Sharpe, E.; Andreescu, D.; Andreescu, S. Paper bioassay based on ceria nanoparticles as colorimetric probes. Anal Chem 2011, 83, 4273–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsvik, C.; Patil, S.; Seal, S.; Self, W.T. Superoxide dismutase mimetic properties exhibited by vacancy engineered ceria nanoparticles. Chem Commun (Camb) 2007, 1056–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirmohamed, T.; Dowding, J.M.; Singh, S.; Wasserman, B.; Heckert, E.; Karakoti, A.S.; King, J.E.; Seal, S.; Self, W.T. Nanoceria exhibit redox state-dependent catalase mimetic activity. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010, 46, 2736–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Patil, S.; Bhargava, N.; Kang, J.F.; Riedel, L.M.; Seal, S.; Hickman, J.J. Auto-catalytic ceria nanoparticles offer neuroprotection to adult rat spinal cord neurons. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 1918–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoti, A.S.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Aggarwal, R.; Davis, J.P.; Narayan, R.J.; Self, W.T.; McGinnis, J.; Seal, S. Nanoceria as Antioxidant: Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. Jom (1989) 2008, 60, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Mameli, M.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Licoccia, S.; Stellacci, F.; Ghibelli, L.; Traversa, E. A novel synthetic approach of cerium oxide nanoparticles with improved biomedical activity. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckert, E.G.; Karakoti, A.S.; Seal, S.; Self, W.T. The role of cerium redox state in the SOD mimetic activity of nanoceria. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2705–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldim, V.; Bedioui, F.; Mignet, N.; Margaill, I.; Berret, J.-F. The enzyme-like catalytic activity of cerium oxide nanoparticles and its dependency on Ce 3+ surface area concentration. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 6971–6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioateră, N.; Pârvulescu, V.; Rolle, A.; Vannier, R.N. Effect of strontium addition on europium-doped ceria properties. Solid State Ionics 2009, 180, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Singh, S. Role of phosphate on stability and catalase mimetic activity of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2015, 132, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Singh, S. Redox-dependent catalase mimetic cerium oxide-based nanozyme protect human hepatic cells from 3-AT induced acatalasemia. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2019, 175, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celardo, I.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Traversa, E.; Ghibelli, L. Pharmacological potential of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asati, A.; Kaittanis, C.; Santra, S.; Perez, J.M. pH-tunable oxidase-like activity of cerium oxide nanoparticles achieving sensitive fluorigenic detection of cancer biomarkers at neutral pH. Anal Chem 2011, 83, 2547–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asati, A.; Santra, S.; Kaittanis, C.; Nath, S.; Perez, J.M. Oxidase-like activity of polymer-coated cerium oxide nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2009, 48, 2308–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J. Boosting the oxidase mimicking activity of nanoceria by fluoride capping: rivaling protein enzymes and ultrasensitive F − detection. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 13562–13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Wei, X.; Guo, J.; Ye, X.; Yang, S. On the origin of the oxidizing ability of ceria nanoparticles. 2015, 5, 97512-97519.

- Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Lou, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, L.; Wei, H. Nanomaterials with enzyme-like characteristics (nanozymes): next-generation artificial enzymes (II). Chemical Society Reviews 2019, 48, 1004–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.; Ni, D.; Rosenkrans, Z.T.; Huang, P.; Yan, X.; Cai, W. Nanozyme: new horizons for responsive biomedical applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2019, 48, 3683–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, A.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, D. A Review on Metal- and Metal Oxide-Based Nanozymes: Properties, Mechanisms, and Applications. Nanomicro Lett 2021, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Y.; Wei, H.; Guo, J.; Yang, Y. Ceria-based peroxidase-mimicking nanozyme with enhanced activity: A coordination chemistry strategy. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshatteri, A.H.; Ali, G.K.; Omer, K.M. Enhanced Peroxidase-Mimic Catalytic Activity via Cerium Doping of Strontium-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks with Design of a Smartphone-Based Sensor for On-Site Salivary Total Antioxidant Capacity Detection in Lung Cancer Patients. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2023, 15, 21239–21251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckert, E.G.; Seal, S.; Self, W.T. Fenton-like reaction catalyzed by the rare earth inner transition metal cerium. Environ Sci Technol 2008, 42, 5014–5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.C.; Johnson, M.E.; Walker, M.L.; Riley, K.R.; Sims, C.M. Antioxidant Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles in Biology and Medicine. Antioxidants (Basel) 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banavar, S.; Deshpande, A.; Sur, S.; Andreescu, S. Ceria nanoparticle theranostics: harnessing antioxidant properties in biomedicine and beyond.

- Feng, N.; Liu, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Li, Q. Advanced applications of cerium oxide based nanozymes in cancer. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Ivanova, O.S.; Manturova, N.E.; Medvedeva, O.A.; Shevchenko, A.V.; Vorsina, E.S.; Achar, R.R.; Parfenov, V.A.; Stupin, V.A. Antimicrobial Activity of Citrate-Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio, S.; Svensson, F.; Breijaert, T.; Seisenbaeva, G.; Kessler, V. Nanoceria–nanocellulose hybrid materials for delayed release of antibiotic and anti-inflammatory medicines. Materials Advances 2022, 3, 7228–7234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Li, Y.; Tian, L. Advanced Biological Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanozymes in Disease Related to Oxidative Damage. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 8601–8614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.R.; Nayak, V.; Sarkar, T.; Singh, R.P. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: properties, biosynthesis and biomedical application. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 27194–27214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiyue, W.; Wang, B.; Shi, D.; Li, F.; Ling, D. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles-Based Optical Biosensors for Biomedical Applications. Advanced Sensor Research 2023, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dhall, A.; Self, W. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: A Brief Review of Their Synthesis Methods and Biomedical Applications. Antioxidants (Basel) 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Hong, G.; Mazaleuskaya, L.; Hsu, J.C.; Rosario-Berrios, D.N.; Grosser, T.; Cho-Park, P.F.; Cormode, D.P. Ultrasmall Antioxidant Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles for Regulation of Acute Inflammation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 60852–60864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.G.; Lee, Y.; Lee, N.; Soh, M.; Kim, D.; Hyeon, T. Ceria-Based Therapeutic Antioxidants for Biomedical Applications. Adv Mater 2024, 36, e2210819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Bao, S.; Yao, L.; Fu, X.; Yu, Y.; Lyu, H.; Pang, H.; Guo, S.; Zhang, H.; et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles in wound care: a review of mechanisms and therapeutic applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2024, 12, 1404651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Mozafari, M. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: Recent Advances in Tissue Engineering. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, S.; Arvapalli, R.; Manne, N.D.; Maheshwari, M.; Ma, B.; Rice, K.M.; Selvaraj, V.; Blough, E.R. Cerium oxide nanoparticle treatment ameliorates peritonitis-induced diaphragm dysfunction. Int J Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 6215–6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne, N.D.; Arvapalli, R.; Nepal, N.; Shokuhfar, T.; Rice, K.M.; Asano, S.; Blough, E.R. Cerium oxide nanoparticles attenuate acute kidney injury induced by intra-abdominal infection in Sprague-Dawley rats. J Nanobiotechnology 2015, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fu, X.; Chen, W.; Chen, P.; Zhu, H.; Yang, B.; Liang, J.; Zeng, F. Amelioration of the rheumatoid arthritis microenvironment using celastrol-loaded silver-modified ceria nanoparticles for enhanced treatment. J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Zhu, Y.; Li, K.; Hao, K.; Chai, Y.; Jiang, H.; Lou, C.; Yu, J.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; et al. Microneedles loaded with cerium-manganese oxide nanoparticles for targeting macrophages in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D.; Nossent, J.; Pavlos, N.J.; Xu, J. Rheumatoid arthritis: pathological mechanisms and modern pharmacologic therapies. Bone Research 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.Y.; Song, S.Y.; Go, S.H.; Sohn, H.S.; Baik, S.; Soh, M.; Kim, K.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.C.; et al. Synergistic Oxygen Generation and Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging by Manganese Ferrite/Ceria Co-decorated Nanoparticles for Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 3206–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Gao, W.; Sun, J.; Gao, K.; Li, D.; Mei, X. Developing cerium modified gold nanoclusters for the treatment of advanced-stage rheumatoid arthritis. Mater Today Bio 2022, 15, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, A.; Saifi, M.A.; Godugu, C. Nanoceria Ameliorates Fibrosis, Inflammation, and Cellular Stress in Experimental Chronic Pancreatitis. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2023, 9, 1030–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Tang, Y.; Xie, W.; Ma, Z.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, T.; Jia, X.; Zhou, J.; Hu, Z.; et al. Cerium-based nanoplatform for severe acute pancreatitis: Achieving enhanced anti-inflammatory effects through calcium homeostasis restoration and oxidative stress mitigation. Mater Today Bio 2025, 31, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hadrick, K.; Chung, S.J.; Carley, I.; Yoo, J.Y.; Nahar, S.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, T.; Jeong, J.W. Nanoceria as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug for endometriosis theranostics. J Control Release 2025, 378, 1015–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.F. Hypoxia and the Tumor Microenvironment. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2021, 20, 15330338211036304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galon, J.; Costes, A.; Sanchez-Cabo, F.; Kirilovsky, A.; Mlecnik, B.; Lagorce-Pagès, C.; Tosolini, M.; Camus, M.; Berger, A.; Wind, P.; et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science 2006, 313, 1960–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Mitra, R.N.; Zheng, M.; Wang, K.; Dahringer, J.C.; Han, Z. Developing Nanoceria-Based pH-Dependent Cancer-Directed Drug Delivery System for Retinoblastoma. Adv Funct Mater 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Varo, G.; Perramón, M.; Carvajal, S.; Oró, D.; Casals, E.; Boix, L.; Oller, L.; Macías-Muñoz, L.; Marfà, S.; Casals, G.; et al. Bespoken Nanoceria: An Effective Treatment in Experimental Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2020, 72, 1267–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Z.; Liu, H.; Guo, Z.; Gou, W.; Liang, Z.; Qu, Y.; Han, L.; Liu, L. A pH-Responsive Polymer-CeO(2) Hybrid to Catalytically Generate Oxidative Stress for Tumor Therapy. Small 2020, 16, e2004654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourmohammadi, E.; Khoshdel-Sarkarizi, H.; Nedaeinia, R.; Darroudi, M.; Kazemi Oskuee, R. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: A promising tool for the treatment of fibrosarcoma in-vivo. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2020, 109, 110533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, F.; Wang, S.; Zheng, H.; Yang, S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H. Cu-doped cerium oxide-based nanomedicine for tumor microenvironment-stimulative chemo-chemodynamic therapy with minimal side effects. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2021, 205, 111878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.; Munro, D.; Clarke, J. Endometriosis Is Undervalued: A Call to Action. Front Glob Womens Health 2022, 3, 902371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, K.; Babu, K.N.; Singh, A.K.; Das, S.; Kumar, A.; Seal, S. Mitigation of endometriosis using regenerative cerium oxide nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2013, 9, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, H.; Kimura, T.; Koyama, S.; Ogita, K.; Tsutsui, T.; Shimoya, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Koyama, M.; Kaneda, Y.; Murata, Y. Mouse model of human infertility: transient and local inhibition of endometrial STAT-3 activation results in implantation failure. FEBS Lett 2006, 580, 2717–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Ehlerding, E.B.; Cai, W. Theranostic nanoparticles. J Nucl Med 2014, 55, 1919–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Tang, W.; Zhao, J.; Jing, L.; McHugh, K.J. Theranostic nanoparticles with disease-specific administration strategies. Nano Today 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Cámara, J.A.; Boullosa, A.M.; Gustà, M.F.; Mondragón, L.; Schwartz, S., Jr.; Casals, E.; Abasolo, I.; Bastús, N.G.; Puntes, V. Nanoceria as Safe Contrast Agents for X-ray CT Imaging. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, P.; Truong, A.; Brommesson, C.; Rietz, A.; Kokil, G.; Boyd, R.; Hu, Z.; Dang, T.; Persson, P.; Uvdal, K. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles with Entrapped Gadolinium for High T 1 Relaxivity and ROS-Scavenging Purposes. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 21337–21345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P.; Tal, A.A.; Skallberg, A.; Brommesson, C.; Hu, Z.; Boyd, R.D.; Olovsson, W.; Fairley, N.; Abrikosov, I.A.; Zhang, X.; et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles with antioxidant capabilities and gadolinium integration for MRI contrast enhancement. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Xu, Z.P.; Little, P.J.; Whittaker, A.K.; Zhang, R.; Ta, H.T. Novel iron oxide-cerium oxide core-shell nanoparticles as a potential theranostic material for ROS related inflammatory diseases. J Mater Chem B 2018, 6, 4937–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turin-Moleavin, I.A.; Fifere, A.; Lungoci, A.L.; Rosca, I.; Coroaba, A.; Peptanariu, D.; Pasca, S.A.; Bostanaru, A.C.; Mares, M.; Pinteala, M. In Vitro and In Vivo Antioxidant Activity of the New Magnetic-Cerium Oxide Nanoconjugates. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Al Saidi, A.K.; Ghazanfari, A.; Baek, A.; Tegafaw, T.; Ahmad, M.Y.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.U.; Park, J.A.; Yang, B.W.; et al. Ultrasmall cerium oxide nanoparticles as highly sensitive X-ray contrast agents and their antioxidant effect. RSC Adv 2024, 14, 3647–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolmanovich, D.D.; Chukavin, N.N.; Savintseva, I.V.; Mysina, E.A.; Popova, N.R.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Sozarukova, M.M.; Ivanov, V.K.; Popov, A.L. Hybrid Polyelectrolyte Capsules Loaded with Gadolinium-Doped Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles as a Biocompatible MRI Agent for Theranostic Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K, K.J.; Kopecky, C.; Koshy, P.; Liu, Y.; Devadason, M.; Holst, J.; K, A.K.; C, C.S. Theranostic Activity of Ceria-Based Nanoparticles toward Parental and Metastatic Melanoma: 2D vs 3D Models. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2023, 9, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadidi, H.; Hooshmand, S.; Ahmadabadi, A.; Javad Hosseini, S.; Baino, F.; Vatanpour, M.; Kargozar, S. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles (Nanoceria): Hopes in Soft Tissue Engineering. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Singh, S.; Maiti, T.K.; Das, A.; Barui, A.; Chaudhari, L.R.; Joshi, M.G.; Dutt, D. Cerium oxide nanoparticles disseminated chitosan gelatin scaffold for bone tissue engineering applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 236, 123813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Li, J.; He, J.; Tang, X.; Dou, C.; Cao, Z.; Yu, B.; Zhao, C.; Kang, F.; Yang, L.; et al. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle Modified Scaffold Interface Enhances Vascularization of Bone Grafts by Activating Calcium Channel of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016, 8, 4489–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Zhen, C.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Fang, Y.; Shang, P. Recent advances of nanoparticles on bone tissue engineering and bone cells. Nanoscale Advances 2024, 6, 1957–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nethi, S.; Nanda, H.S.; T.W.J, S.; Patra, C. Functionalized nanoceria exhibit improved angiogenic properties. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2017, 5, 9371–9383. [CrossRef]

- Augustine, R.; Dalvi, Y.B.; Dan, P.; George, N.; Helle, D.; Varghese, R.; Thomas, S.; Menu, P.; Sandhyarani, N. Nanoceria Can Act as the Cues for Angiogenesis in Tissue-Engineering Scaffolds: Toward Next-Generation in Situ Tissue Engineering. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2018, 4, 4338–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chang, H.; Yang, S.; Tu, M.; Zhang, X.; Yu, B. Cerium-containing α-calcium sulfate hemihydrate bone substitute promotes osteogenesis. J Biomater Appl 2019, 34, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Azfer, A.; Rogers, L.M.; Wang, X.; Kolattukudy, P.E. Cardioprotective effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles in a transgenic murine model of cardiomyopathy. Cardiovascular Research 2007, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Shen, Q.; Xie, Y.; You, M.; Huang, L.; Zheng, X. Incorporation of Cerium Oxide into Hydroxyapatite Coating Protects Bone Marrow Stromal Cells Against H(2)O(2)-Induced Inhibition of Osteogenic Differentiation. Biol Trace Elem Res 2018, 182, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ge, K.; Ren, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Effects of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles on the Proliferation, Osteogenic Differentiation and Adipogenic Differentiation of Primary Mouse Bone Marrow Stromal Cells In Vitro. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2015, 15, 6444–6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliari, F.; Mandoli, C.; Forte, G.; Magnani, E.; Pagliari, S.; Nardone, G.; Licoccia, S.; Minieri, M.; Di Nardo, P.; Traversa, E. Cerium oxide nanoparticles protect cardiac progenitor cells from oxidative stress. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 3767–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.L.; Popova, N.R.; Selezneva, II; Akkizov, A.Y.; Ivanov, V.K. Cerium oxide nanoparticles stimulate proliferation of primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts in vitro. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2016, 68, 406–413. [CrossRef]

- Pesaraklou, A.; Mahdavi-Shahri, N.; Hassanzadeh, H.; Ghasemi, M.; Kazemi, M.; Mousavi, N.S.; Matin, M.M. Use of cerium oxide nanoparticles: a good candidate to improve skin tissue engineering. Biomed Mater 2019, 14, 035008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliga, A.R.; Edoff, K.; Caputo, F.; Källman, T.; Blom, H.; Karlsson, H.L.; Ghibelli, L.; Traversa, E.; Ceccatelli, S.; Fadeel, B. Cerium oxide nanoparticles inhibit differentiation of neural stem cells. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Ren, Y.; Pan, W.; Yu, Z.; Tong, L.; Li, N.; Tang, B. Fluorescent Nanocomposite for Visualizing Cross-Talk between MicroRNA-21 and Hydrogen Peroxide in Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Live Cells and In Vivo. Anal Chem 2016, 88, 11886–11891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Behera, M.; Mahapatra, C.; Sundaresan, N.R.; Chatterjee, K. Nanostructured polymer scaffold decorated with cerium oxide nanoparticles toward engineering an antioxidant and anti-hypertrophic cardiac patch. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2021, 118, 111416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Kosaric, N.; Bonham, C.A.; Gurtner, G.C. Wound Healing: A Cellular Perspective. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 665–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Sanchez, M.; Lancel, S.; Boulanger, E.; Neviere, R. Targeting Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Treatment of Impaired Wound Healing: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, M.; Crosera, M.; Monai, M.; Montini, T.; Fornasiero, P.; Bovenzi, M.; Adami, G.; Turco, G.; Filon, F.L. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Absorption through Intact and Damaged Human Skin. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigurupati, S.; Mughal, M.R.; Okun, E.; Das, S.; Kumar, A.; McCaffery, M.; Seal, S.; Mattson, M.P. Effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the growth of keratinocytes, fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells in cutaneous wound healing. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2194–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Lu, J.; Li, J.; Du, Y.; Sun, X.; Chen, X.; Gao, J.; Ling, D. Ceria nanocrystals decorated mesoporous silica nanoparticle based ROS-scavenging tissue adhesive for highly efficient regenerative wound healing. Biomaterials 2018, 151, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Cornel, E.J.; Li, C.; Du, J. Combined Antioxidant-Antibiotic Treatment for Effectively Healing Infected Diabetic Wounds Based on Polymer Vesicles. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 9027–9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Su, G.; Zhang, R.; Dai, R.; Li, Z. Nanomaterials-Functionalized Hydrogels for the Treatment of Cutaneous Wounds. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allu, I.; Kumar Sahi, A.; Kumari, P.; Sakhile, K.; Sionkowska, A.; Gundu, S. A Brief Review on Cerium Oxide (CeO2NPs)-Based Scaffolds: Recent Advances in Wound Healing Applications.

- Augustine, R.; Zahid, A.A.; Hasan, A.; Dalvi, Y.B.; Jacob, J. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle-Loaded Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogel Wound-Healing Patch with Free Radical Scavenging Activity. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2021, 7, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dewberry, L.C.; Niemiec, S.M.; Hilton, S.A.; Louiselle, A.E.; Singh, S.; Sakthivel, T.S.; Hu, J.; Seal, S.; Liechty, K.W.; Zgheib, C. Cerium oxide nanoparticle conjugation to microRNA-146a mechanism of correction for impaired diabetic wound healing. Nanomedicine 2022, 40, 102483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sener, G.; Hilton, S.A.; Osmond, M.J.; Zgheib, C.; Newsom, J.P.; Dewberry, L.; Singh, S.; Sakthivel, T.S.; Seal, S.; Liechty, K.W.; et al. Injectable, self-healable zwitterionic cryogels with sustained microRNA - cerium oxide nanoparticle release promote accelerated wound healing. Acta Biomater 2020, 101, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Kumari, S.; Manohar Aeshala, L.; Singh, S. Investigating temperature variability on antioxidative behavior of synthesized cerium oxide nanoparticle for potential biomedical application. J Biomater Appl 2024, 38, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Yao, N.; Wen, H.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Shen, C. A nanoenzyme-modified hydrogel targets macrophage reprogramming-angiogenesis crosstalk to boost diabetic wound repair. Bioactive Materials 2024, 35, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Ding, J.; Qin, M.; Wang, L.; Jiang, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Jia, W. Enhanced ·OH-Scavenging Activity of Cu-CeO(x) Nanozyme via Resurrecting Macrophage Nrf2 Transcriptional Activity Facilitates Diabetic Wound Healing. Adv Healthc Mater 2024, 13, e2303229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhrotun, A.; Oktaviani, D.J.; Hasanah, A.N. Biosynthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles Using Phytochemical Compounds. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allawadhi, P.; Khurana, A.; Allwadhi, S.; Joshi, K.; Packirisamy, G.; Bharani, K.K. Nanoceria as a possible agent for the management of COVID-19. Nano Today 2020, 35, 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, S.; Naik, P. Synthesis and biomedical applications of Cerium oxide nanoparticles – A Review. Biotechnology Reports 2018, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokel, R.A.; Hussain, S.; Garantziotis, S.; Demokritou, P.; Castranova, V.; Cassee, F.R. The Yin: An adverse health perspective of nanoceria: uptake, distribution, accumulation, and mechanisms of its toxicity. Environ Sci Nano 2014, 1, 406–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soo Choi, H.; Liu, W.; Misra, P.; Tanaka, E.; Zimmer, J.P.; Itty Ipe, B.; Bawendi, M.G.; Frangioni, J.V. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nature Biotechnology 2007, 25, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, A.; Chu, D.; Li, S. Cerium Oxide Nanostructures and their Applications. InTech: 2016.

| Treatment | Non-Steroidal Anto-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) | Steroids (Corticosteroids) | Opioid Pain Killers | Adjuvants | Immunotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pros | Simple to access; Very effective short term; Low cost | Available in many formulations; Well-characterized mechanism; Effective short and long-term | Do not interfere with healthy inflammation; Prevents shock and, in some cases, death from trauma; Work with anti-inflammatories | Simple mechanism; Common ; Many available |

Highly tunable; Useful for many diseases; Can treat away from site of administration |

| Cons | High doses cause side effects; Possible overdose; Can cause more inflammation | Prolonged use results in severe side effects; Rare side effects make them unusable for some patients | Not anti-inflammatory; Highly addictive; Inadequate for chronic conditions | Must be administered directly to the site of interest; Limited effects; Low tunability | Long timeframes; Unpredictable side effects; Limited efficacy |

| Examples | Ibuprofen (Advil) Naproxen (Aleve) Acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin) |

Hydrocortisone Prednisone Beclomethasone |

Oxycodone Hydrocodone Morphine |

Aluminum salts Virosomes |

Allergy shots; Type-1 Diabetes Delay; Reversal of tumor immune privilege |

| Nanomaterials | Size | Dose | Outcome | Cytokines/Chemokines | In vivo/In Vitro | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNT | L: 5–15 μm; D: 10–20 nm | Inhalation 5 mg/m3 | Immunosuppression | TGFβ↑, IL-10↑ | Male C57BL/6 | [72,73] |

| SWCNT | L: 1–3 μm; D: 1–4 nm | Pharyngeal aspiration 40-120 μg/mouse | Inflammation immunosuppression | TNF-α↑, IL-6↑, MCP1↑ | BALB/c C57BL/6 | [74] |

| SWCNT | L: 3–30 μm; D: 67 nm | Intratracheal 25, 50 μg | Allergic inflammation | IL-4↑, IL-5↑, IL-13↑, IFN-γ↑ | Male mice ICR | [75] |

| MWCNT | L: 15 ± 5 μm D: 25 ± 5 nm |

Intravenously 1 mg/kg | Inflammation | IL-4↑, IL-33↑ | C57BL/6 | [76] |

| Graphene | 4 ± 1 μm2 area | Intravenously 1 mg/kg | Th2 immune response | IL-33↑, IL-5↑, IL-13↑ | C57BL/6 | [76] |

| Fullerene C60 | N/A | Intravenously 50 ng/mouse | Immunosuppression | Serum histamine↓, Lyn↓, Syk↓, ROS↓ | C57BL/6 | [77] |

| Carboxyfullerene | NA | Peritoneum and air pouch 40 mg/kg | Activate immune system | NA | C57BL/6 | [78] |

| PEG coated AuNP | 13 nm | Intravenously 0-4.26 mg/kg | Acute inflammation | MCP-1/CCL-2↑, | BALB/c | [79] |

| PfMSP-119/PvMSP-119 coated AuNPs | 17 nm | Subcutaneously 25 μg/mouse | Poor immunogenic | N/A | BALB/c | [80] |

| Citrate-stabilized AuNPs | 40 nm | Oropharyngeal aspiration 0.8 mg/kg | Hypersensitivity | MMP-9↑, MIP-2↑, TNF-α↓, IL-6↓ | TDI-sensitised mice (BALB/c) | [81] |

| AgNPs | 22.18 ± 1.72 nm | Inhalation of particles/cm3 | Immunosuppression | Malt1 gene↓, Sema7a gene↓ | C57BL/6 | [82] |

| AgNPs | 52.25 ± 23.64 nm | Intratracheal instillation 3.5 or 17.5 mg/kg | Enhance immune function | IL-1↑, IL-6↑, TNF-α↑, GSH↓, NO↑ | Wistar rats | [83] |

| FeONP | 43 nm | Intratracheal instillation (4 or 20 μg × 3) | Activate immune response | IFN-γ↑, IL-4↑ | OVA-BALB/c | [84,85] |

| FeONP | 58.7 nm | Intravenously ≤10 mg iron/kg | Immunosuppression | IFN-γ↓, IL-6↓, TNF-α↓ | DTH mice | [86] |

| FeONP | 35 ± 14 nm | Intratracheally 500 μg/mouse | Immunosuppression | IgE↓, IL-4↓ | OVA-BALB/c | [87] |

| Nanoceria | D: 8 nm | Oropharyngeal instillation of 10-100 μg/mouse | Inflammation | TNF-α↑, IL-6↑, osteopontin↑ | C57BL/6 | [88] |

| Nanoceria | D: 55 nm | Inhalation of 641 mg/m3 | Inflammation | IL-1β↑, TNF-α↑, IL-6↑, MDA↑, GSH↓ | Wistar rats | [89] |

| Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) | 85–100 nm | Infuse in accordance with Doxil | Hypersensitivity reactions | NA | Patients with solid tumors | [90] |

| Polystyrene NP | 50 nm | Intratracheal 200 μg/mouse | Anti-inflammation immunosuppression | IL-4↓, IL-5↓, IL-13↓ | Allergen challenge mice | [91] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).