1. Introduction

Cholelithiasis, or gallstone disease, is one of the most prevalent conditions globally [

1,

2]. The incidence escalates with age, exhibiting a predominance among the elderly, being more pronounced in women than in males, and particularly prevalent in Hispanic groups, while African and Asian populations demonstrate the lowest prevalence [

3,

4].

In the United States, almost 20 million individuals possess gallstones, and annually, between 300,000 and 750,000 cholecystectomies are conducted. In Europe, around 20% of the adult population possesses gallstones, and annually, 900,000 cholecystectomies are performed [

4]. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has swiftly established itself as the gold standard for treating symptomatic gallstones, supplanting the open surgery, and is among the most frequently executed general surgical interventions globally. Although laparoscopic cholecystectomy offers numerous benefits over open surgery, including reduced hospitalization and recovery duration, diminished postoperative pain, lower morbidity and mortality rates, and a decreased incidence of specific complications like incisional hernias, apprehensions have been raised about the heightened risk of significant intraoperative complications linked to this technique. Various studies have sought to elucidate the nature of these complications, their prevalence, and the associated risk factors [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Literature categorizes the principal intraoperative complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy as follows [

10]:

- -

Bile duct injuries (BDI)

- -

Vascular or vasculo-biliary (VB) injuries

- -

Bowel perforation and other trocar/ Veress needle-induced injuries

1.1. Risk Factors for Intraoperative Complications in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

At present, there is no universally standardized definition of “difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy”, which may be complicated by inflammation or scarring that alters local anatomy, thereby rendering dissection more challenging and perilous. However, certain risk factors may indicate a difficult procedure (e.g., acute calculous cholecystitis, empyema, gangrene, perforation, and Mirizzi syndrome). In these instances, the LC correlates with prolonged operating duration, elevated blood loss, extended hospital stay, heightened complication rates, conversion to open surgery, increased treatment expenses, and fatality rates [

11].

Men are more prone to experiencing IOC than women, and the conversion to open surgery is likewise more prevalent among men than women. Acute cholecystitis constitutes an additional independent risk factor for intraoperative problems during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the necessity for conversion to open surgery. Acute cholecystitis involves inflammation of the gallbladder and adjacent tissues, which may distort gallbladder structure, complicating surgical intervention and heightening the risk of complications [

12]. Current guidelines advocate for the application of the Tokyo Guidelines 2018 (TG18) to stratify the risk of patients with acute calculous cholecystitis, thereby reducing the likelihood of intraoperative complications during laparoscopic cholecystectomy [

13,

14]. Chronic situations are comparatively more advantageous as these patients can be admitted electively, resulting in operational treatments that are typically less complex and more manageable for surgeons.

A gangrenous gallbladder presentation is highly correlated with an increased risk of intraoperative complications and conversion to open surgery. Body weight significantly influences the probability of IOC: a weight over 90 kg was independently correlated with a heightened incidence of IOC. Individuals with elevated body weight are more susceptible to significant gallbladder inflammation or fibrosis, complicating dissection for the surgeon. Furthermore, individuals with a history of abdominal surgery are at an increased risk of developing IOC compared to those without such a history [

6,

9,

15,

16].

1.2. Bile Duct Injuries

BDIs are the predominant category of intraoperative complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with a greater incidence of small lesions compared to large ones [

17]. Despite the overall incidence remaining low, certain studies noted only a marginal reduction in the annual incidence of iatrogenic biliary duct injury over a decade, contrary to the substantial decrease anticipated from enhanced imaging technologies and cumulative laparoscopic expertise [

8,

17].

Bile duct injuries were categorized according to the Strasberg-Bismuth classification as follows [

18,

19]:

- -

Type A: Injury to the cystic duct or the accessory biliary ducts of Luschka may result in unnoticed and asymptomatic leaks post-surgery, or lead to the development of bile peritonitis;

- -

Type B and C: Occlusion (B) and transection (C) injuries of the aberrant right hepatic ducts. This suggests the draining of the cystic duct into an anomalous right hepatic duct, leading the surgeon to confuse the right hepatic duct with the cystic duct at its junction with either the main hepatic duct or the common bile duct. In type B damage, the patient may stay asymptomatic for years until presenting with recurrent cholangitis, characterized by fever and right upper quadrant pain. A type C injury involves a biliary leak;

- -

Type D: lateral injury to the common bile duct leading to a biliary leak. May be handled endoscopically or could advance to type E damage;

- -

-

Type E: Engage the principal ducts and are categorized based on the extent of harm to the biliary tree. Patients affected typically exhibit jaundice weeks to years post-cholecystectomy, necessitating surgical intervention. The primary forms of type E bile duct damage are as follows:

Bismuth type I (E1) – transection > 2cm from the confluence;

Bismuth type II (E2) – transection < 2cm form the confluence;

Bismuth type III (E3) – transection in the hilum;

Bismuth type IV (E4) – separation of the major ducts in the hilum;

Bismuth type V (E5) – association of a type C injury and an injury in the hilum;

Significant biliary leakage typically occurs 2 to 10 days following cholecystectomy. Patients affected usually exhibit fever, stomach pain, and/or bilious ascites. Jaundice may also occur. Leucocytosis and atypical liver function tests, especially increased serum alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase levels, are prevalent. Bilirubin levels will be somewhat raised as the body reabsorbs bile from third-spacing.

Alternative classifications of these injuries have been proposed, such as the BILE classification, which emphasizes the clinical ramifications of BDI and offers a framework to effectively direct the treatment strategy. The suggested categorization approach is clinically focused, although it also incorporates the anatomical relationship of each IBDI stage, utilizing the Strasberg classification [

20].

1.3. Extrabiliary Complications

Access-related consequences encompass those associated with extra-peritoneal insufflations, port site hemorrhage, small intestinal laceration, transverse colon injury, damage to the round ligament of the liver or the greater omentum, hepatic injury, and duodenal or gastric perforation. Such injuries exhibit a greater occurrence in patients with a history of abdominal surgery, particularly those involving the upper abdomen or umbilical region [

10,

21,

22].

Biliary problems in laparoscopic cholecystectomy are nearly as prevalent, and certain cases can be life-threatening if not promptly detected and adequately managed [

21].

1.3.1. Vascular Injuries

Intraoperative or postoperative hemorrhagic problems may arise from trocar insertion, surgical dissection, or inadequate retraction. The predominant areas of vascular injury include the epigastric vessels (often compromised during trocar insertion), the cystic artery, and the liver bed [

23]. Hemorrhage following laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be life-threatening; nevertheless, mild hemorrhage is significantly more prevalent. Minor hemorrhaging may provide more challenges in laparoscopic surgery compared to open cholecystectomy due to the difficulty in removing the clot that obscures the surgical field. Hemorrhaging may potentially result in more severe consequences, such as ductal damage, due to the excessive application of electrocautery [

10].

Numerous efforts have been undertaken to systematically categorize vascular lesions. The Strasberg-Bismuth classifications for biliary injuries exclude vascular involvement. In 2010, Kaushik proposed a novel classification system that categorizes vascular injuries into severe and small based on the necessity for conversion, supplementary surgical interventions, or blood transfusions.

The European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) has recently introduced a new categorization called ATOM, which encompasses the architecture of injury including vascular and biliary damage (A), timing of detection (To), and mechanism of injury (M).

Preoperative identification of a vascular lesion accompanying a biliary lesion is crucial, since inadequate vascularization of the common bile duct may lead to anastomotic strictures following surgical biliary tract repair, recurrent cholangitis, and secondary biliary cirrhosis. Significant vascular injury: Any hemorrhage affecting the right hepatic artery, portal vein, suprahepatic veins, or inferior vena cava that necessitates conversion to open surgery for control or repair; requirement for blood transfusions; concomitant biliary injury; necessity for transfer to a tertiary center [

24].

1.3.1.1. Hepatic Artery Injuries

Among hepatic artery injuries, lesions of the right hepatic artery are the most often documented complication that may arise during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The closure of the hepatic artery is generally well tolerated, as it does not typically result in significant effects due to the portal circulation and an extensive network of collateral arterial branches originating from the hepatic hilum. In such instances, hepatic artery ligation may occasionally result in ischemic hepatic necrosis or liver atrophy. RHA injury is commonly observed in conjunction with bile duct injury. RHA injuries typically arise in two scenarios: firstly, during a fundus-first laparoscopic cholecystectomy conducted amidst significant inflammation; secondly, in the context of vascular anomalies, such as the caterpillar hump of the RHA, where the hepatic artery may be erroneously identified as the cystic artery. The primary complication of RHA injury is significant hemorrhage during dissection, which invariably necessitates conversion to open surgery in the hands of unskilled practitioners[

24].

1.3.1.2. Hepatic Veins, Portal Vein and Major Retroperitoneal Vessel Injuries

Venous hemorrhage is less prevalent than arterial hemorrhage. Hemorrhage resulting from hepatic vein injury typically originates from the liver bed after gallbladder removal. Patients may have a substantial branch of the middle hepatic vein attached to the liver bed, resulting in an elevated risk of venous damage during cholecystectomy. The existence of chronic cholecystitis and fibrous tissue may elevate the risk of substantial hemorrhage from the liver bed [

23]. In the management of venous injuries, hemorrhage from the middle hepatic vein branch during surgery can only be controlled with direct hemostatic sutures; this procedure may be executed via laparoscopy by skilled practitioners or frequently necessitates conversion to open surgery [

24].

Injuries to the portal vein are often concomitant with injuries to the biliary system and the right hepatic artery. The surgical correction of portal vein lesions is exceedingly challenging, frequently complicated by significant hemorrhage, and seldom achieved successfully. In the event of portal vein injury during surgery, rapid reconstruction by a skilled hepato-biliary surgeon is warranted, provided the patient is hemodynamically stable.

The primary consequence following surgical repair of a portal vein lesion is acute portal thrombosis, which frequently results in liver infarction. Injuries to significant retroperitoneal vascular structures are rare although potentially fatal consequences of laparoscopy. Injuries to the inferior vena cava and aorta are commonly linked to the insertion of a trocar or Veress needle during laparoscopic surgery.

1.4. Anatomical Variations as Independent Risk Factors for Intraoperative Complications

Patients exhibiting anatomical abnormalities experience considerable intraoperative and postoperative problems in contrast to those with normal anatomy. A significant correlation exists between intraoperative hemorrhage and cystic artery anomalies, while intraoperative bile leaks are linked to choledochal cysts and gallbladder malformations [

23]. A statistically significant correlation has been discovered between conversion to an open method and the occurrence of anatomical abnormalities in general [

25]. Although less prevalent than vascular anomalies, congenital malformations and normal variants of the biliary tree can be significant during laparoscopic surgery, as failure to identify them may result in iatrogenic damage, hence elevating morbidity and fatality rates [

25,

26,

27].

1.4.1. Variations in Ductal Anatomy

The predominant ductal abnormality identified is an elongated CD. The elongated common duct benefits the surgeon by facilitating manipulation and ensuring that only the duct is engaged, terminating at the infundibulum. Nevertheless, an elongated, parallel, and spiral compact disc could pose a risk due to the uncertainty of its termination. Ligation of the cystic duct in proximity to the common hepatic duct may lead to stricture of the latter. Likewise, confusing the cystic duct with the bile duct may lead to iatrogenic harm, including unintentional ligation or transection of the extrahepatic bile duct. Furthermore, an atypically elongated cystic duct remnant (up to 6 cm in length) may persist following cholecystectomy [

27,

28].

In inflammatory situations, it merges with the RHD/CBD, creating a misleading appearance of the infundibulum. Excessive traction on the GB aligns CBD/RHD with CD, resulting in the misidentification of CBD as CD and causing accidental damage.

Variations in cystic duct insertion

- -

Type A - CD joining the anterior sectorial duct

- -

Type R - CD joining the RHD

- -

Type P - CD joining the posterior sectorial duct.

Subvesical ducts or ducts of Luschka are small, superficial ducts located in the region of the GB draining into the major hepatic ducts. Subvesical ducts are present on both sides of the margins of the GB where the peritoneum is reflected onto the liver. Although they may not drain any liver parenchyma, they can be a source of a bile leak or biliary peritonitis after cholecystectomy. Injury to these ducts can be avoided by giving adequate traction to the GB away from the liver edge [

27,

28].

1.4.2. Variations in Vascular Anatomy

It is more typical for the extrahepatic biliary tree’s vascular supply to vary than its ductal structure. Approximately 50% of people exhibit variations in the hepatic and cystic arteries. Hemorrhage from the cystic artery is a significant complication during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, elevating the likelihood of conversion to open surgery. The documented rate of conversion to open surgery due to vascular damage is approximately 0%–1.9% with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with a mortality rate of about 0.02%. Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the anatomy of the cystic artery and its variations [

27,

28].

The cystic artery is a branch of the right hepatic artery, typically originating in Calot’s triangle. It typically emits an anterior or superficial branch and a posterior or deep branch. This bifurcation typically occurs near the gallbladder. Furthermore, the cystic artery provides a direct branch to the common duct, typically seen during dissection between the duct and the artery [

27,

28].

Both originate in the right hepatic artery within Calot’s triangle. It is the most prevalent vascular abnormality [

28].

The right hepatic artery may exhibit a sinuous tortuosity known as caterpillar hump or Moynihan’s hump, which occupies a significant section of Calot’s triangle. As a result of an anomalous course, the right hepatic artery approaches the cystic duct and gallbladder, leading to the development of a short cystic artery. Consequently, the right hepatic artery may be erroneously identified as the cystic artery and mistakenly ligated, leading to profuse hemorrhage and subsequent necrosis of the right lobe of the liver. Moreover, due to the brevity of the cystic artery originating from the caterpillar hump, it is susceptible to avulsion from the hepatic artery [

27,

28].

Upon nearing the gallbladder, the cystic artery bifurcates into deep and superficial branches at the neck of the gallbladder. The superficial branch traverses the left side of the gallbladder. The deep branch traverses the connective tissues between the gallbladder and liver parenchyma. The deep branch generates little branches that supply the GB, which interconnect with the superficial branches. This type is observed in 70%–80% of instances, as per the literature [

27,

28].

Cystic artery with an uncertain origin (Gastroduodenal artery, superior pancreaticoduodenal, celiac trunk, right gastric artery)

This variant of the cystic artery is referred to as a low-lying cystic artery, which bypasses Calot’s triangle and approaches the gallbladder beyond it. In traditional open cholecystectomy, it is regarded as inferior to the cystic duct, as it typically localizes superficially and anteriorly to the cystic duct from a laparoscopic perspective. The terminal segment, as it nears the gallbladder, is significant for laparoscopic surgeons. It requires initial manipulation and is prone to damage and hemorrhage during the dissection of the peritoneal folds linking the hepatoduodenal ligament to Hartmann’s pouch of the gallbladder or to the cystic duct [

27].

A pertinent vascular anomaly involved a vessel with a delayed origin from the right hepatic artery entering the gallbladder at the cystic plate level, seen in 11 cases. This variant, though rare, is surgically significant and may be harmed, resulting in severe hemorrhage during the cholecystectomy after ligating the cystic duct and artery [

28].

The anatomical variant of the right hepatic artery typically arises from the superior mesenteric artery or the aorta. It traverses Calot’s triangle posterior to the portal vein and proceeds parallel to the cystic duct along its course across the triangle. It can be entirely encompassed by the CD of gallbladder. It produces several minor branches to nourish the gallbladder at its body, and it is frequently entirely enveloped by the gallbladder. We must use caution regarding this variant of the right hepatic artery. From the laparoscopic perspective, it appears as a singular, substantial artery [

27,

28].

1.5. Prevention and Management of Intraoperative Complications

A proposed strategy for preventing intraoperative problems in laparoscopic cholecystectomy is intraoperative imaging. Intraoperative cholangiography has been demonstrated to decrease the occurrence of biliary injuries, but not significantly, and to enhance the detection of biliary duct injuries during surgery, hence facilitating timely diagnosis and intervention [

13,

29,

30].

A further risk mitigation strategy is the attainment of the critical view of safety (CVS). When properly implemented, this preventive mechanism has been shown to markedly diminish both biliary and vascular damage through accurate dissection of Calot’s triangle and the identification of the cystic duct and cystic artery, thereby allowing for an exceedingly minimal margin of error [

23,

30,

31]. Although not always practical, CVS is one of the most successful techniques for anatomical identification, hence receiving significant endorsement in the current recommendations for laparoscopic cholecystectomy [

13,

30].

To mitigate access-related intraoperative difficulties, the optimal recommendation is to execute a mini-laparotomy at the entry site for the optic trocar, particularly in patients with a history of abdominal procedures. A novel approach has recently been introduced in which the epigastric trocar is initially inserted following the establishment of pneumoperitoneum at Palmer’s point using a Veress needle, providing a safer option for patients by limiting the risk of bowel injury, decreasing conversion rates, and improving recovery outcomes [

22].

If a safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy is unfeasible, the optimal alternative is to select a bail-out surgery, as delineated in the Tokyo Guidelines 2018 [

32]:

- -

Subtotal cholecystectomy: the procedure entails incising the gallbladder, aspirating its contents, and excising as much of the gallbladder wall as feasible while treating the stump, rather than completely resecting the gallbladder, a method that has been employed since the era of open cholecystectomy.

- -

Open conversion: The necessity of transitioning from a laparoscopic treatment to an open surgery should not be regarded as a surgical failure. Rather, it seeks to mitigate the risk of illness and mortality. The conversion rate has been declining with the regular use of LC. Surgeons are acquiring increased proficiency in this minimally invasive procedure over time [

7,

9].

Ultimately, in the event of significant intraoperative difficulties, particularly vasculo-biliary issues, the prevailing opinion advocates for the referral of patients to specialist centers with hepatobiliary surgeons for optimal management of these complications, especially if identified postoperatively [

13,

19].

2. Materials and Methods

We retrospectively analysed medical records of 648 patients who were diagnosed with cholelithiasis and had laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the General Surgery Department, Colentina Clinical Hospital, Romania, in the time period between 2020 and 2024. The analysis included operative protocols, anaesthesiology records, the medical history which included the history of the disease, documented laboratory findings and imaging results.

We analysed the type and frequency of intraoperative complications, as well as factors that increase the risk for development of such complications. We noted the causes and incidence of conversions and the way they resolved. We noted gender, age, body mass index (BMI), pathohistological findings of the surgically removed gallbladder, as well as their correlation with the occurrence of complications.

The patients were divided into groups according to their age (6 groups of patients, each with a 10 year age gap), gender (male, and female), BMI (greater than 30 kg/m2, and less than 30 kg/m2). All surgically extracted gallbladders were examined by pathophysiologists in order to confirm the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis, chronic cholecystitis or presence of malignancy. Subsequently, correlations between these pathohistological findings and type/frequency of intraoperative and postoperative complications were examined.

An ultrasonographic exam was performed 24 hours before each surgery. In order to simplify the analysis of the correlation between ultrasonographic findings and possible complications, all ultrasonographic findings were grouped into three groups: group I- chronic cholecystitis, group II- uncomplicated acute cholecystitis (increased gallbladder wall thickness > 3 mm but without gallbladder empyema, necrosis, perforation), and group III- complicated acute cholecystitis.

We used a standard four-port technique in all surgical interventions.

Patients who underwent surgery for acalculous cholecystitis or polyps were excluded.

3. Results

A total of 648 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy were included in this study.

Majority of the study people (432 patients, 67%) ware female (

Figure 1).

Most of the study patients were in the normal range of weight, 35% (225 patients) having a BMI < 30kg/m2.

Among the study people, 38% (246 patients) of study people had smoking habit, 191 (29%) had diabetes, and 412 (63%) had hypertension.

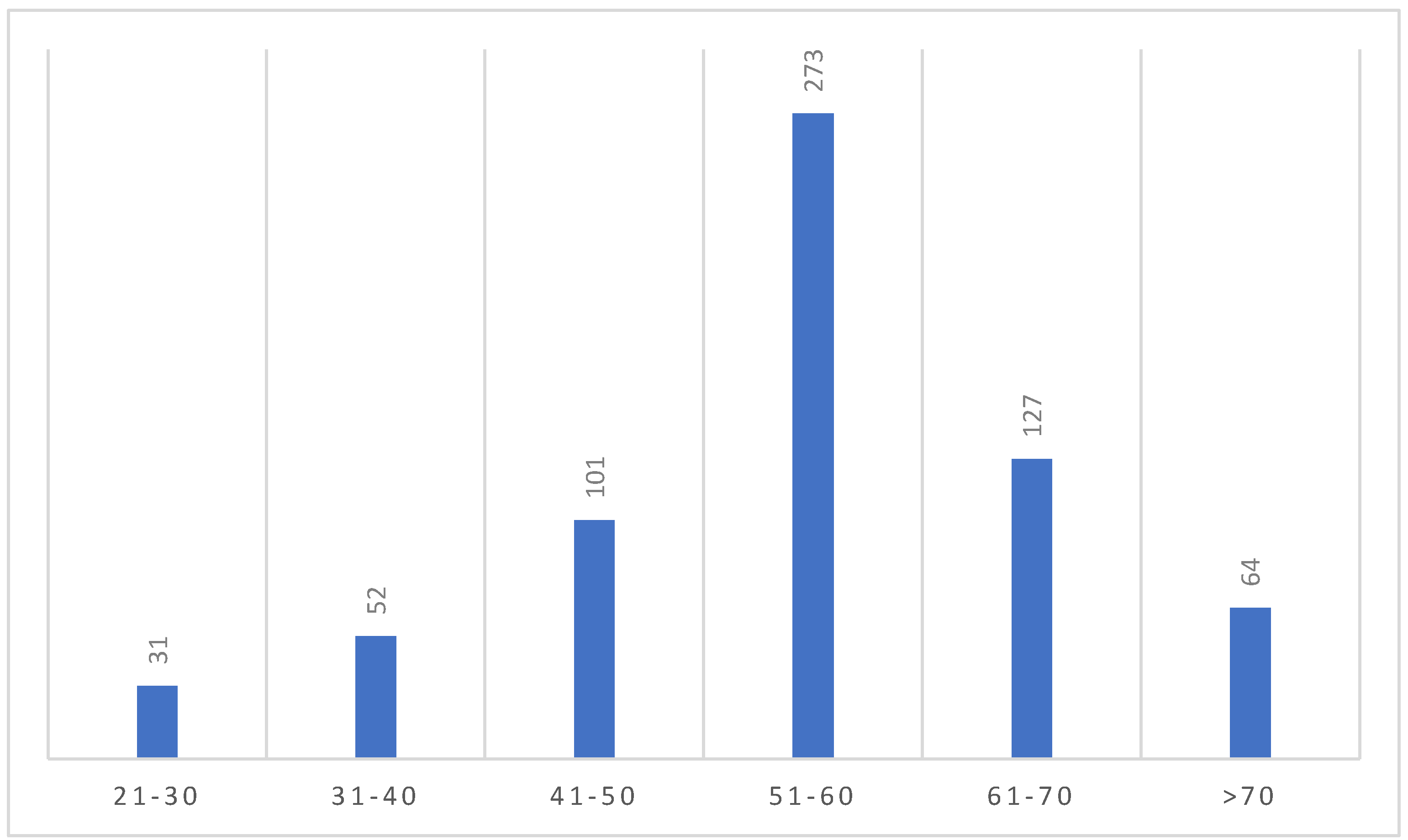

The majority of people in our study was in the age group of 51-60 (273 patients, 42%) (

Figure 2).

On admission the majority of patients had chronic calculous cholecystitis (486 patients, 75%). As for the portion of patients with acute cholecystitis at admission, they were mostly uncomplicated (without gangrene or perforation of the gallbladder) (125 patients, 19%).

117 patients (18%) of the study people had history of abdominal surgery with comparable distribution between upper and lower abdominal interventions (

Table 1).

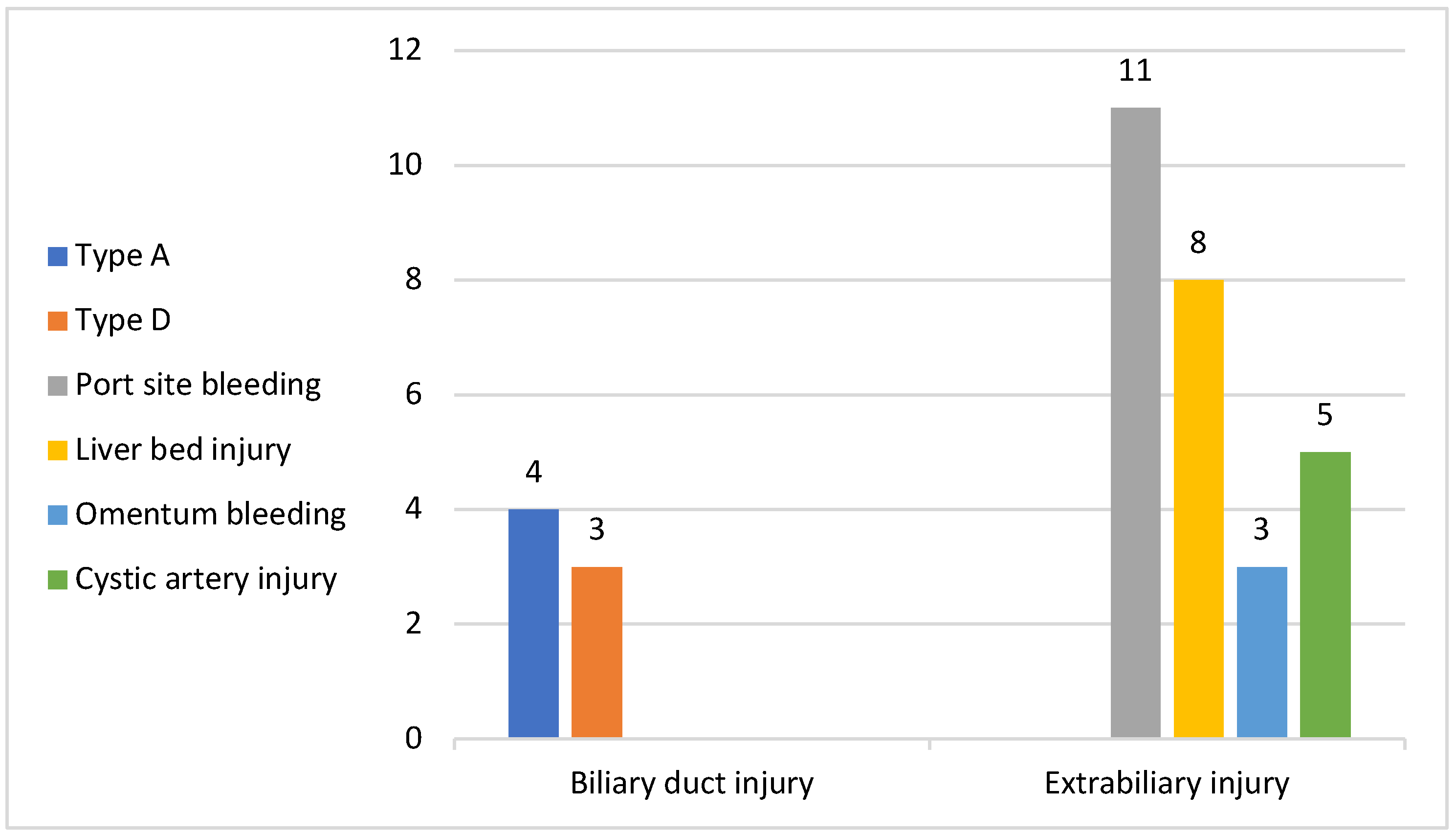

As for the intraoperative complications, among the study people the total number of complications we registered was of 34 (5%), among which 14 had access-related complications (11 with trocar site bleeding and 3 patients with lesions of the omentum), all 14 with previous upper abdominal surgery; 8 had liver bed injury during gallbladder dissection; 5 patients had bleeding from the cystic artery, mostly due to the presence of a double cystic artery which was undetected at the moment of sectioning or started at the moment of cystic duct dissection due to close proximity with the latter (

Figure 3).

In our study group, 7 patients presented bile duct injuries: 4 patients with Bismuth type A and 3 with Bismuth type D. Among the 4 patients with type A biliary injury, laparoscopic resolution of the injury was feasible in 3 cases with a lower dissection and clipping and sectioning of the cystic duct proximal to the site of injury, without affecting the common bile duct while open conversion was mandatory in 1 case when a transcystic drainage was applied.

As for the 3 patients with type D Bismuth biliary injuries, all 3 were converted to open surgery with a Kehr tube.

Overall, we registered 8 cases of conversion to open surgery: in 5 cases the conversion was applied in the impossibility of solving the injury laparoscopically (1 case of type A biliary injury, 3 cases of type D biliary injury, 1 case of cystic artery injury and bleeding in which laparoscopic haemostasis was not achievable). The remaining 3 cases of conversion to open surgery were bail-out procedures to prevent the occurrence of major intraoperative complications. All 3 patients presented history of upper abdominal surgery and after a first inspection of the abdominal cavity and the assessment of an important adhesion process, it was clear that a safe dissection of the gallbladder was not feasible laparoscopically and we resorted to open conversion (

Table 2).

In no case in this study lot we resorted to subtotal cholecystectomy as bail-out procedure.

Among minor intraoperative complications, the most frequent were iatrogenic perforations of the gallbladder.

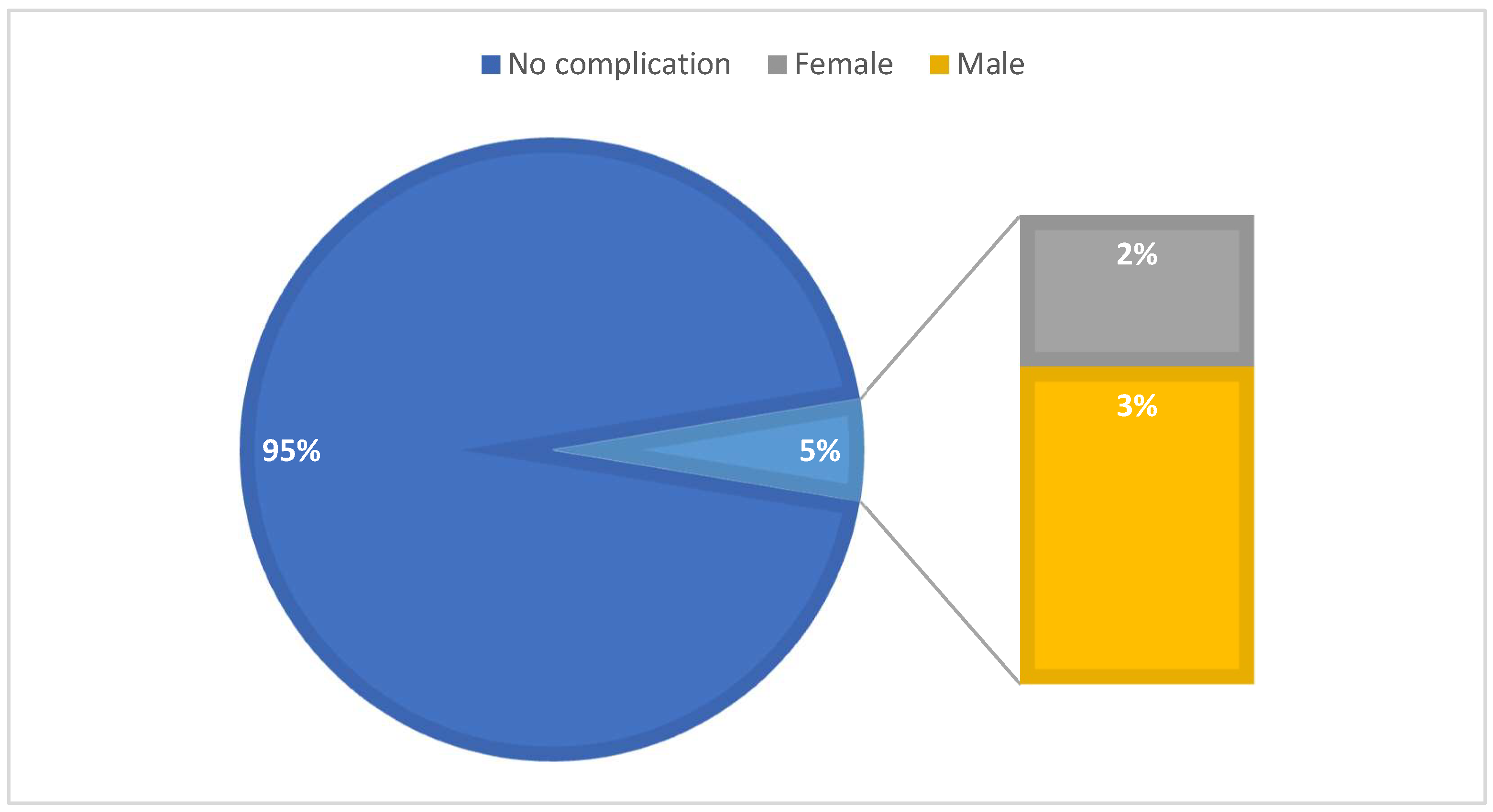

Among the patients which presented intraoperative complications the majority were men (23 patients) (

Figure 4). As for the 8 cases of conversion to open surgery, the majority were also men (5 patients).

4. Discussion

Since its first application, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has rapidly become the gold standard for the treatment of symptomatic gallstones [

33]. This procedure has demonstrated to have several advantages when compared to the classic open cholecystectomy among which we can mention minimal trauma, decrease pain, shorter hospitalisation, shorter postoperative recovery and, finally, better cosmetic outcomes [

34].

Despite presenting several advantages, it comes with a set of new possible complications, some of which with a major impact on surgical outcome and patient’s health.

The frequency of these major intraoperative complications is influenced by both patient- and surgeon-related (experience in laparoscopy surgery and more specifically in laparoscopic cholecystectomy) factors.

We retrospectively analysed a lot of 648 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy in our General Surgery Department over the course of 5 years.

Among patient-related factors, a review of recent literature confirmed that male patients are more likely to experience an intraoperative complication in laparoscopic cholecystectomies compared to women, despite the higher number of women with gallstone disease and the higher number of women undergoing surgical treatment for it [

35,

36,

37]. The results in our study about gender prevalence in laparoscopic cholecystectomy is consistent with the current literature showing a higher number of female patients with symptomatic gallstones and undergoing surgery, 432 out of 648 patients, with a higher number of male patients experiencing intraoperative complications, 23 male patients out of the total 34 cases of complications in our study. Moreover, the majority of patients in our study converted to open surgery were men.

Majority of the study people, 273, were in the age group of 51-60 years, followed by the age group 61-70, 127, which shows a prevalence of the gallstone disease requiring surgery in this age group that is in accordance with current literature [

38,

39].

As for comorbidities, the main ones in our study were arterial hypertension and type II diabetes, also associated with the prevalence of older study people. We didn’t register a significant association between the presence of comorbidities of such kind and a higher risk for intraoperative complications or conversion to open surgery.

Another patient-related factor we registered in our study is history of previous surgery. More specifically, all the patients who presented access-related complications in our study (either lesions to the omentum or port-site bleeding), the most common class of intraoperative complication in our study group, had personal history of abdominal surgery. Moreover, out of the 8 cases of conversion to open surgery, 5 patients had had abdominal surgery in the past. This result is also in line with the current literature sustaining that previous abdominal surgery, especially of the upper abdomen, represents a higher risk factor when considering intraoperative complications and the use of bail-out procedures, such as conversion to open surgery, in laparoscopic cholecystectomy [

40].

Most patients presented with chronic cholecystitis while only 162 patients had acute cholecystitis on admission with only 32 patients presenting acute complicated cholecystitis. Out of the 34 patients in our study which presented intraoperative complications, the vast majority, 26, had a form of acute cholecystitis. Moreover, all the patients who suffered major injuries in our study, such as biliary ones, had acute cholecystitis, thus confirming acute cholecystitis as one of the risk factors for intraoperative injuries in laparoscopic surgery [

41]. These patients indeed usually associate an intense inflammatory process which makes the dissection of the gallbladder pedicle in the Callot’s triangle even harder and more dangerous. It also increases the risk of injury to surrounding structures, such as the liver, in the attempt of dissecting the adhesions, especially in the case of acute cholecystitis complicated by a gangrenous gallbladder or abscesses of the cystic plate.

5. Conclusions

Laparoscopy cholecystectomy has rapidly become the gold standard in the treatment of symptomatic gallstones presenting several advantages compared to the classic open surgery, such as minimal trauma, decrease pain, shorter hospitalisation, shorter postoperative recovery and, finally, better cosmetic outcomes. However, it is also associated with a set of new risks and complications, some of which are major, such as bile duct injuries and vascular injuries, requiring often bail-out procedures as a form of prevention or when intraoperative injuries are harder to fix laparoscopically. Many factors, both patient-related and procedure-related, have been studied and associated with a higher risk of intraoperative complications, such as age, gender, acute cholecystitis, comorbidities, etc.

In our retrospective study we offered our own experience as a non-emergency hospital regarding laparoscopic cholecystectomy and its major complications, mostly in accordance with current literature about the topic.

Knowing which are the major risks when performing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy is an important step towards understanding what can be improved in the procedure, in the patient’s preparation or even in the training of the new generation of surgeons, to minimise the intraoperative complications as well as the need for bail out procedures such as conversion to open surgery.

Overall, laparoscopy cholecystectomy still remains a safe procedure and the better option compared to open surgery in centres with experience with laparoscopy and with this specific procedure. Surgeons should be able to understand the risks and preventing them by adopting certain measures, such as critical view of safety, or by resorting to bail out procedures in the impossibility of carrying out the operation safely, not considering this choice as a failure but as a valuable action for the well-being of the patient.

Author Contributions

All authors had equal contributions in the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the protocol being approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Colentina Clinical Hospital Number 21/17 May 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Limitations of the Study: As for the limitations of this study, the main one is that our objective was not a statistical one but an observational one, by offering our personal experience about major intraoperative complications during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the associated risk factors.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LC |

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

| IOC |

Intraoperative Complications |

| CD |

Cystic Duct |

| BDI |

Biliary duct injury |

| GB |

Gallbladder |

References

- F. Peery et al., “Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2018,” Gastroenterology, vol. 156, no. 1, pp. 254-272.e11, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Unalp-Arida and C. E. Ruhl, “Increasing gallstone disease prevalence and associations with gallbladder and biliary tract mortality in the US,” Hepatology, vol. 77, no. 6, pp. 1882–1895, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Aerts and F. Penninckx, “The burden of gallstone disease in Europe,” Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Supplement, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 49–53, 2003. [CrossRef]

- F. Lammert et al., “Gallstones,” Nat Rev Dis Primers, vol. 2, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Radunovic et al., “Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Our experience from a retrospective analysis,” Open Access Maced J Med Sci, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 641–646, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Fagiri, T. İ. Başak, and S. Nergiz, “ASSESSMENT OF RISK FACTORS AND COMPLICATIONS OF LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY,” Journal Of Healthcare In Developing Countries, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 08–10, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. Rahman, M. S. Uddin, A. Taher, and M. G. Masum, “A retrospective study among patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: intraoperative and postoperative complications,” International Surgery Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 18–22, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Alexander et al., “Reporting of complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review,” HPB, vol. 20, no. 9, pp. 786–794, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Amreek, S. Z. M. Hussain, M. H. Mnagi, and A. Rizwan, “Retrospective Analysis of Complications Associated with Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for Symptomatic Gallstones,” Cureus, vol. 11, no. 7, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. S. Lee, R. S. Chari, G. Cucchiaro, and W. C. Meyers, “Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy,” The American Journal of Surgery, vol. 165, no. 4, pp. 527–532, 1993. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Abdallah, M. H. Sedky, and Z. H. Sedky, “The difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a narrative review,” BMC Surg, vol. 25, no. 1, p. 156, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- ”Treatment of acute calculous cholecystitis - UpToDate.” Accessed: Jun. 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-acute-calculous-cholecystitis?search=cholecystitis%20worldwide&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=2#topicContent.

- L. Michael Brunt et al., “Safe cholecystectomy multi-society practice guideline and state-of-the-art consensus conference on prevention of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy,” Surg Endosc, vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 2827–2855, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Yokoe et al., “Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos),” J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 41–54, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. AlKhalifah, A. Alzahrani, S. Abdu, A. Kabbarah, O. Kamal, and F. Althoubaity, “Assessing incidence and risk factors of laparoscopic cholecystectomy complications in Jeddah: a retrospective study,” Ann Med Surg (Lond), vol. 85, no. 6, pp. 2749–2755, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang, S. Hu, X. Gu, and X. Zhang, “Analysis of risk factors for bile duct injury in laparoscopic cholecystectomy in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Medicine (United States), vol. 101, no. 37, p. E30365, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Reinsoo, Ü. Kirsimägi, L. Kibuspuu, K. Košeleva, U. Lepner, and P. Talving, “Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomies: an 11-year population-based study,” European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 2269–2276, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Berci and L. Morgenstern, “An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.,” J Am Coll Surg, vol. 180, no. 5, pp. 638–639, May 1995.

- L. E. Alvear-Torres and A. Estrada-Castellanos, “Bile duct injury, experience from 3 years in a tertiary referral center,” Cirugia y Cirujanos (English Edition), vol. 90, no. 4, pp. 508–518, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Symeonidis, K. Tepetes, G. Tzovaras, A. A. Samara, and D. Zacharoulis, “BILE: A Literature Review Based Novel Clinical Classification and Treatment Algorithm of Iatrogenic Bile Duct Injuries,” J Clin Med, vol. 12, no. 11, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- ”Extra Biliary Complications of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Experience from a Study of 1420 Cases - PubMed.” Accessed: Jun. 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37391979/.

- M. Seif, M. Mourad, M. R. Elkeleny, and M. Wael, “Safe access to laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with previous periumbilical incsions: new approach to avoid entry related bowel injury,” Langenbecks Arch Surg, vol. 410, no. 1, p. 57, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Rajeeth, S. Tilakaratne, and R. C. Siriwardana, “The hidden threat of uncontrollable bleeding from the gallbladder bed during laparoscopic cholecystectomy,” Int J Surg Case Rep, vol. 112, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pesce, N. Fabbri, and C. V. Feo, “Vascular injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: An often-overlooked complication,” World J Gastrointest Surg, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 338–345, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Gupta, A. Kumar, C. P. Hariprasad, and M. Kumar, “Anatomical variations of cystic artery, cystic duct, and gall bladder and their associated intraoperative and postoperative complications: an observational study,” Ann Med Surg (Lond), vol. 85, no. 8, pp. 3880–3886, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- ”Anatomical variations and congenital anomalies of extra hepatic biliary system encountered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy - PubMed.” Accessed: Jun. 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20209691/.

- K. Singh, R. Singh, and M. Kaur, “Clinical reappraisal of vasculobiliary anatomy relevant to laparoscopic cholecystectomy,” J Minim Access Surg, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 273, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Benson and R. E. Page, “A practical reappraisal of the anatomy of the extrahepatic bile ducts and arteries,” British Journal of Surgery, vol. 63, no. 11, pp. 853–860, 1976. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Archer, D. W. Brown, C. D. Smith, G. D. Branum, and J. G. Hunter, “Bile Duct Injury During Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Results of a National Survey,” Ann Surg, vol. 234, no. 4, p. 549, 2001. [CrossRef]

- K. T. Buddingh, V. B. Nieuwenhuijs, L. Van Buuren, J. B. F. Hulscher, J. S. De Jong, and G. M. Van Dam, “Intraoperative assessment of biliary anatomy for prevention of bile duct injury: a review of current and future patient safety interventions,” Surg Endosc, vol. 25, no. 8, p. 2449, 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. Terho, V. Sallinen, H. Lampela, J. Harju, L. Koskenvuo, and P. Mentula, “The critical view of safety and bile duct injuries in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a photo evaluation study on 1532 patients,” HPB, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 1824–1829, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Wakabayashi et al., “Tokyo Guidelines 2018: surgical management of acute cholecystitis: safe steps in laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis (with videos),” J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 73–86, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Ferreres and H. J. Asbun, “Technical aspects of cholecystectomy,” Surgical Clinics of North America, vol. 94, no. 2, pp. 427–454, 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Coccolini et al., “Open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. Systematic review and meta-analysis,” International Journal of Surgery, vol. 18, pp. 196–204, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Ambe and L. Köhler, “Is the male gender an independent risk factor for complication in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis?,” Int Surg, vol. 100, no. 5, pp. 854–859, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Botaitis, A. Polychronidis, M. Pitiakoudis, S. Perente, and C. Simopoulos, “Does gender affect laparoscopic cholecystectomy?,” Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 157–161, Apr. 2008. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang et al., “Global Epidemiology of Gallstones in the 21st Century: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 1586–1595, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ”Gallstones (Cholelithiasis) - PubMed.” Accessed: Jun. 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29083691/.

- F. Lirussi et al., “Gallstone disease in an elderly population: The Silea study,” Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 485–491, 1999. [CrossRef]

- D. Schirmer, J. Dix, R. E. Schmieg, M. Aguilar, and S. Urch, “The impact of previous abdominal surgery on outcome following laparoscopic cholecystectomy,” Surg Endosc, vol. 9, no. 10, pp. 1085–1089, Oct. 1995. [CrossRef]

- Ł. Warchałowski et al., “The analysis of risk factors in the conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 20, pp. 1–12, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).