In the dynamic continuum of career development, career indecision is a significant barrier to both individual career development and fulfillment (Xu & Bhang, 2019). Moreover, this pervasive indecision not only impedes personal advancement but also presents a considerable challenge to the global labor market (Priyashantha et al., 2023). Marked by dissatisfaction and ambiguity, career distress often exacerbates this indecision (Lipshits-Braziler et al., 2016), trapping individuals in a cycle of indecision that undermines their capacity for decisive career-related choices.

In this sense, the notion of career adaptability has emerged as a salient mediator (Chen et al., 2022), offering the potential to reduce the adverse effects of career distress on decision-making processes. Recognized as an essential competency (Rossier et al., 2017; Savickas, 1997), career adaptability is pivotal in navigating the complexities of contemporary vocational trajectories, particularly within an economic environment characterized by perpetual volatility in job markets and professional roles. Thus, the ability to adjust to fluctuating conditions, redefine one’s vocational identity, and surmount career barriers is now regarded as the foundation of occupational resilience (Rossier et al., 2017).

Despite its recognized significance, there is a lack of research on the mediating function of career adaptability. While several previous studies have delved into the constructs of career distress (Priyashantha et al., 2023) and indecision (Milot-Lapointe et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2021) in isolation, few have investigated how career adaptability affects the link between these two components. This gap highlights the need for a thorough investigation to clarify how career adaptability exerts its effects.

Addressing this scholarly gap is of paramount academic and practical consequence. Indeed, an enriched understanding of career adaptability can catalyze the formulation of more efficacious strategies and support frameworks, empowering individuals to transcend career distress and indecision. Such insights hold the promise of enhancing vocational counseling approaches and shaping policy directives, ultimately resulting in a workforce that is more adaptable and resilient.

This investigation seeks to address this gap by examining the intermediary role of career adaptability within the interplay of career distress and career indecision. By employing a rigorous methodological approach, this study aims to provide empirical evidence that elucidates the extent to which career adaptability can act as a protection against the negative effects of career distress on an individual’s decision-making abilities.

Background

The examination of the interrelationship between career distress and career indecision in academic settings is a focal point of vocational psychology, with career adaptability identified as a significant mediating variable. The following sections will provide an in-depth exploration of career adaptability, career distress, and career indecision, discussing their respective roles and interplay in the formation of academic career paths. This discourse will be underpinned by empirical evidence and theoretical frameworks, culminating in a thorough investigation of these interconnected phenomena.

The Importance and Dynamics of Career Adaptability

Career adaptability is a multifaceted construct that encapsulates an individual’s capacity to effectively manage and respond to the various changes and challenges encountered throughout their vocational journey (Akkermans et al., 2018). It entails not simply reacting to changes but also proactively anticipating and preparing for future vocational developments (Gao et al., 2019). Moreover, career adaptability constitutes a dynamic and continuous process that equips individuals to flourish within an ever-changing career landscape (Chen et al., 2020), making it an essential skill set for long-term vocational success and fulfillment.

Additionally, career adaptability fosters resilience and flexibility, empowering individuals to navigate the uncertainties of the job market successfully (Ferrari et al., 2017; Rossier et al., 2017). It enables proactive personal and professional development, aligned with the evolving demands of the workplace (Seibert et al., 2016). This adaptability is pivotal in maintaining a positive career trajectory, particularly during periods of economic fluctuation or industry transformation, where the capacity to pivot and seize new opportunities is invaluable (Akkermans et al., 2018).

Furthermore, career adaptability is instrumental in guiding career development tasks, particularly for students and early-career professionals (Hartung & Cadaret, 2017). It facilitates critical decisions, such as the choosing of an academic major, the exploration of career possibilities, and the formulation of strategic professional goals (Savickas, 2020). Career adaptability also requires ongoing self-evaluation and market analysis to ensure that career decisions are relevant and align with individual goals and market dynamics (Savickas et al., 2009).

The pillars of career adaptability—concern, control, curiosity, and confidence—constitute the core components of this concept. Concern motivates proactive engagement in career development; control fosters the conviction in one’s influence over career outcomes; curiosity provokes the pursuit of new knowledge; confidence provides the assurance necessary to enact change and adapt to new career challenges (Hartung & Savickas, 2023). Together, these elements comprise a comprehensive framework for understanding and enhancing career adaptability.

In summary, career adaptability encompasses an individual’s proactive approach to anticipating and preparing for career transitions, managing emotional and behavioral self-regulation, and committing to continuous career planning and goal setting (Chen et al., 2020; Savickas, 2020). It encompasses problem-solving abilities to address vocational challenges effectively, a tendency to adopt new roles and environments, and a dedication to lifelong learning to sustain market relevance and competitiveness. Consequently, this diverse skill set empowers individuals to navigate their career paths with resilience and foresight, adapting to the progressive demands of the professional sphere (Peng et al., 2021).

Understanding and Addressing Career Distress

Career distress represents a substantial emotional and psychological challenge for individuals when they face career-related difficulties, uncertainties, or barriers (Akmal et al., 2023). This distress typically manifests as frustration, anxiety, and dissatisfaction, stemming from a variety of factors associated with one’s professional life (Akmal et al., 2023; Laditka et al., 2023). It is a complex issue that can influence multiple aspects of an individual’s career and overall well-being (Schilbach et al., 2023).

The origins of career distress are diverse, including uncertainty (Akmal et al., 2023) regarding career paths, job prospects, or future directions, all of which can lead to feelings of discomfort. Moreover, job insecurity, such as the fear of potential job loss or unstable employment conditions (Qazi et al., 2023), also contributes to career distress. Additionally, a discrepancy between actual career outcomes and personal aspirations can provoke distress (Praskova & McPeake, 2022), as can the challenge of balancing work responsibilities with personal life.

Career distress influences several critical areas, including decision-making processes, where it may result in indecision or suboptimal choices (Akmal et al., 2023; Milot-Lapointe et al., 2020). It can also impede performance, reducing productivity and job satisfaction (Hengen & Alpers, 2021). Prolonged exposure to career distress can also adversely affect an individual’s physical and mental health (Browning & Heinesen, 2012; Sullivan & von Wachter, 2009), underscoring the need for timely and effective intervention.

In the academic context, the interplay between career distress and academic career trajectories is complex and multi-dimensional. Academics face a variety of challenges throughout their career progression (McAlpine et al., 2014), including research, teaching, and administrative responsibilities associated with tenure-track positions. When the realities of these roles fall short of expectations, such as during periods of limited research funding (Bloch et al., 2014) or overwhelming multi-role demands (Zhao et al., 2024), career distress can arise, impacting an individual’s well-being and professional identity. Career transitions are particularly stressful for academics. The progression from graduate studies to faculty roles can be a significant source of stress (Opoku et al., 2020). Early-career academics face uncertainties related to tenure, publication achievements, and professional networking (Nästesjö, 2021; Toomey, 2022). Conversely, mid-career academics may experience distress due to stagnation or perceived lack of advancement, influencing their motivation and career path (Welch et al., 2019). Empirical research supports the notion that career distress significantly affects job satisfaction, commitment, and retention in the academic sector (Mampuru et al., 2024).

The Social Cognitive Career Theory offers valuable insight into this dynamic, suggesting that self-efficacy and coping mechanisms significantly affect distress levels (Brown & Lent, 2019). This theoretical perspective emphasizes the importance of developing effective coping strategies to reduce the effects of career distress.

Factors Contributing to Career Indecision and their Implications

Career indecision is a significant concern for individuals, particularly when they face crucial career-related decisions (Katerina et al., 2021; Priyashantha et al., 2023). This uncertainty or hesitation arises from a combination of factors, such as conflicting interests, insufficient information, apprehension regarding commitment, and external pressures (Priyashantha et al., 2023; Xu & Bhang, 2019). A comprehensive understanding of the complexities of career indecision is essential, as it can profoundly affect one’s professional trajectory and personal satisfaction (Bagchi & Reddy, 2023). The origins of career indecision are varied (Priyashantha et al., 2023). The inherent ambiguity within the complexities of contemporary labor markets frequently leads to indecision among adolescents and young adults (Parola & Marcionetti, 2024).

Differences between individual goals and real career results can bring people to a point of doubt (Creed et al., 2009; Patton & Creed, 2007). Furthermore, the prospect of long-term career commitments can provoke anxiety, while societal expectations, parental influence, and peer pressure may exacerbate feelings of indecision (Jemini-Gashi et al., 2021). In the academic context, career indecision assumes a unique significance. It presents challenges to decision-making processes, potentially resulting in delays or suboptimal choices with enduring consequences (Sarsıkoğlu, 2023). The development of academic identity is also vulnerable to the effects of indecision, as students shape their self-concept in the academic environment (Ching, 2021). Moreover, the stress associated with sustained indecision can negatively impact both well-being and academic performance (Chambel & Curral, 2005; Müceldili et al., 2023), emphasizing the need for sensitive and supportive interventions.

Empirical studies affirm the impact of career indecision on academic pathways (Priyashantha et al., 2023). Research on late adolescents in Italy has identified distinct profiles based on the extent of career decision-making difficulties, ranging from “Lower Indecision” to “Very High Indecision,” illustrating the broad range of indecision encountered (Parola & Marcionetti, 2024). The Social Cognitive Career Theory posits that self-efficacy and coping strategies are critical in managing career indecision (Jemini-Gashi et al., 2021). The practical implications of understanding career indecision are considerable, particularly within educational settings (Priyashantha et al., 2023). Schools and universities are strategically positioned to provide specialized support for students facing decision-making challenges (Daniels et al., 2011; Pordelan et al., 2020). Creating environments that promote self-reflection, interest exploration, and mentorship is instrumental in reducing career indecision.

Tailored career guidance interventions are essential for effectively addressing the complexities of career indecision (Sharapova et al., 2023). These interventions should be customized to meet the distinct needs of each student, considering their concerns and decision-making tendencies (Parola & Marcionetti, 2024). In doing so, career counselors and educators can offer more impactful support, enabling students to make well-informed decisions that align with their interests and goals, thereby fostering more rewarding academic and professional journeys.

Method

Participants

The study’s cohort comprised 337 undergraduate students from various academic disciplines at …………. University, ranging in age from 18 to 25 years and an average age of 21.3 years. The gender composition was 56% female. Participants were recruited through a stratified random sampling approach to achieve a representative cross-section of the student body. Stratification criteria included gender, academic year, and field of study. Eligibility was restricted to individuals actively enrolled in a full-time degree program who had formally declared a major, with a minimum Grade Point Average (GPA) of 15 out of 20, indicative of good academic standing. Under ethical research practices, participants were thoroughly informed about the study’s objectives, specifically its focus on examining the interplay between career distress and career indecision, with an emphasis on the mediating influence of career adaptability. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses, participation was entirely voluntary, with the option to withdraw at any stage without consequences. Data were collected through a series of questionnaires designed to quantitatively measure career distress, career indecision, and career adaptability, with the administration of these measures estimated to require approximately 12 minutes per participant.

Measures

Career distress questionnaire. The career distress questionnaire was designed and developed by Creed et al. (2015) to measure career distress. It has 12 items, based on the Likert scale, with questions such as, “I spend time thinking about choosing a job and what I may do about it.” The present study also demonstrated that the career distress scale has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .889). Moreover, the correlation of the questions with a good score ranged from .53 to .66.

Career indecision questionnaire. The career indecision questionnaire was designed by Lee (2004). It has 33 items and six subscales that include: lack of information (6 items), require information (6 items), adjective decision (6 items), disagreement with others (4 items), confused identity (6 items), and the anxiety of selection (5 items). According to Lee (2004), the reliability of this questionnaire, assessed through an internal consistency analysis, ranges from .81 to .96. Divergent validity results indicated that the correlation of this questionnaire with the Osipow job decision-making scale is -.48. The results of the current study confirm the validity and reliability of this scale for use in the Iranian population.

Career adaptability questionnaire. The career adaptability questionnaire was designed and validated by Savickas and Porfeli (2012), and consists of 24 items rated on a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire measures four dimensions: concern, control, curiosity, and confidence. Savickas and Porfeli (2012) reported the coefficient of Cronbach’s alpha among the 13 countries as follows: concern (.83), control (.74), curiosity (.79), and confidence (.85), with an overall scale reliability of .92.

Analysis Method

To evaluate the psychometric properties of the career distress scale, classical test theory (CTT), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and item response theory (IRT) methods were employed. These methods provide comprehensive insights into the psychometric qualities of individual items as well as the overall scale. SPSS.22 and R-4.3.3 software (with TAM, eRM, psych, lavaan, semPlot, and lavaanPlot packages) were utilized for the analyses. Within the CTT framework, each item on the Career Distress Scale was examined based on their distributional properties and their correlation with the total score, allowing for the identification of items that do not correlate well with the overall scale. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The career distress scale, designed as a one-dimensional measure (Creed et al., 2016), was analyzed using CFA to verify its factor structure. For the IRT analysis, the Rating Scale Model (RSM) for multi-valued scoring (Andrich, 1978) was applied, providing item difficulty parameters and fit statistics (infit and outfit) to evaluate item fit to the proposed model. To examine the relationships between career distress, career adaptability, and career indecision, structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized to test the hypothesis that career adaptability mediates the relationship between career distress and career indecision.

Additionally, mediation analysis was conducted using linear and multiple regression models as suggested by Judd and Kenny (1981). This comprehensive analysis framework ensures a robust evaluation of the psychometric properties of the career distress scale and the intricate relationships between career distress, career adaptability, and career indecision.

Results

Psychometric Study

A total of 330 students completed the Career Distress Scale in the psychometric evaluation. The total scores and analysis of the career distress items are presented in

Table 1. The mean total score for the students was 3.01 (

SD = .87), and the data distribution was normal, without significant skewness or kurtosis. The Career Distress Scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .889, and the correlation of individual items with the total score ranged between .53 and .66.

To aid in the interpretation of scores, total career distress scores were categorized as high, moderate, and low based on the 25th and 75th percentiles. In this sample, scores below 2.41 were considered low, scores above 3.68 were considered high, and scores between 2.41 and 3.68 were considered average.

The results of applying the Rasch Measurement Model (RSM) to the data are also presented in

Table 1. The difficulty of the items ranged from -.70 to -1.66 on a logit scale, indicating that all 12 items of the Career Distress Scale provided a more accurate estimate for the present study sample at the lower levels of the trait continuum. Examination of the RSM fit indicators, specifically outfit and infit values, showed that the questions had a good fit, with values between .6 and 1.4 (Wright, 1994).

Confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the proposed factor model had a good fit with the data (IFI = .991, TLI = .989, CFI = .991, GFI = .97, SRMR = .029, RMSEA= .026). These fit indices confirmed that the Career Distress Scale measures a single construct. The standardized factor loadings for all questions ranged from .56 to .71 (

Table 1), and all were significant (

p < .001). Overall, the results indicate that the Career Distress Scale is a reliable psychometric measure for use in this population.

SEM Study

In this study, a structural equation model (SEM) was employed to investigate the relationships between variables. The advantages of using SEM include (a) improved statistical estimation by accounting for measurement error; (b) the ability to investigate and test multiple paths simultaneously; and (c) the capability to test complex models, such as mediation models, while providing fit indices for the tested model.

Data analysis revealed that, after removing 7 outliers, the data distribution was normalized. The skewness values ranged from -.85 to 1.68, and the kurtosis values ranged from -.6 to 3.26 for all variables. According to Byrne (2010), data are suitable for multivariate analysis assuming normality if the skewness is between -2 and +2 and the kurtosis is between -7 and +7. Pearson correlation, mean, and standard deviation of the research variables are presented in

Table 2. All variables showed a significant correlation with career indecision (the exogenous variable). Notably, there was a negative correlation between career adaptability and career indecision (

r = -.678,

p < .001), indicating that higher career adaptability is associated with lower career indecision. Consistent with the research literature, there was a positive relationship between career distress and career indecision (Creed et al., 2016).

The structural model included career adaptability (comprising four components) and career distress as exogenous variables, and career indecision (comprising six components) as the endogenous variable. The model’s validity was evaluated using goodness of fit indices: discrepancy function divided by degree of freedom (CMIN/DF < 5), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .08), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < .08), incremental fit index (IFI > .9), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI > .9), and comparative fit index (CFI > .9). The fit indices indicated that the model had a good fit (CMIN/DF = 1.24, RMSEA = .027, SRMR = .028, IFI = .993, TLI = .991, CFI = .993).

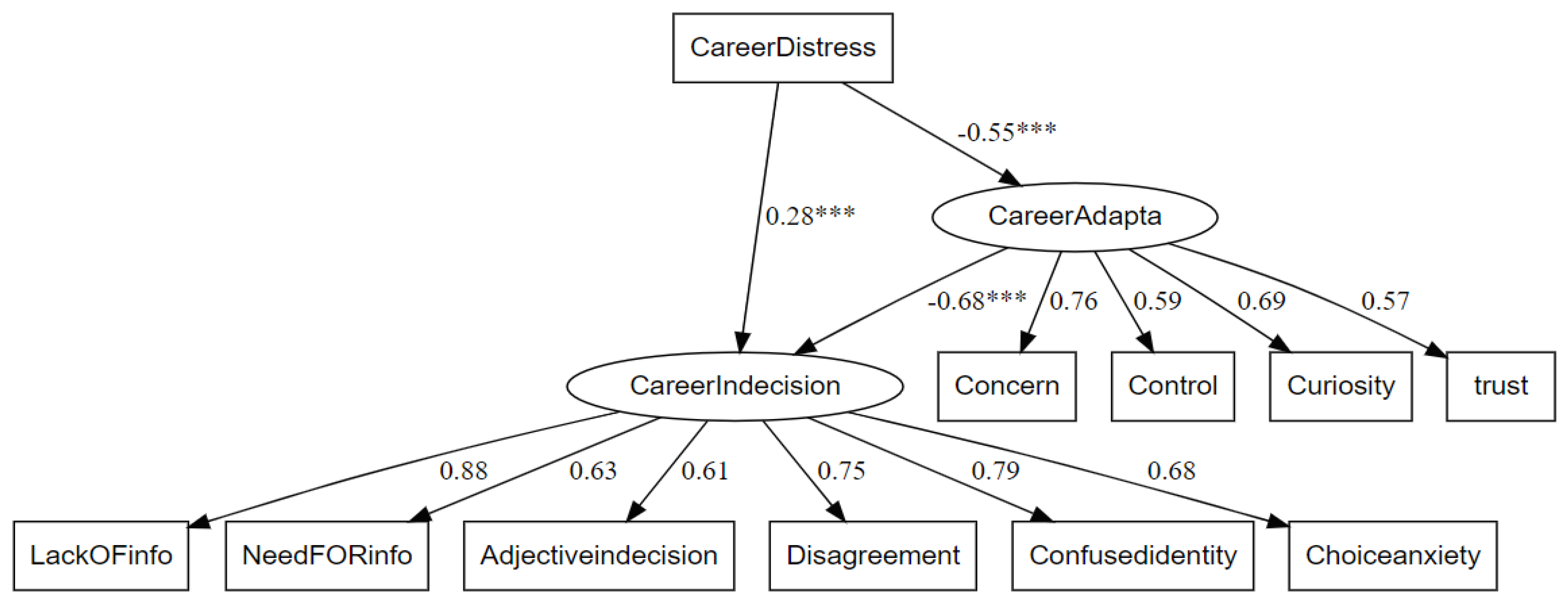

As shown in

Figure 1, the relationships between career adaptability and career distress in relation to career indecision were significant. Consistent with the research literature, there was a negative relationship between career adaptability and career indecision and a positive relationship between career distress and career indecision (Creed et al., 2016).

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the psychometric properties of the career distress scale and the effect of this construct on career indecision, with the mediating role of career adaptability in a sample of students. The findings support the mediating role of career adaptability (CA) in the relationship between career distress and career indecision. In other words, career distress indirectly affects career indecision through career adaptability.

The findings of the present study showed that the direct effect of career distress on career indecision is significant. This result is consistent with the findings of Lipshitz-Braziler et al. (2016), who showed that career distress disrupts the career decision-making process. Although many studies consider career distress a byproduct of many job-related activities such as career indecision (Lipshitz-Braziler et al., 2016), career compromise (Creed & Hughes, 2013), job problems, job transitions, and inadequate career preparation (Creed et al., 2015). However, it can be argued that these two constructs have a circular relationship and reinforce each other. Career distress means experiencing uncomfortable impacts during the career decision-making process and avoiding choosing a specific profession, and this condition can lead to a range of negative impacts on individuals (Şensoy & Siyez, 2018). A high level of career distress can cause a wide range of issues, such as career indecision, dissatisfaction with the chosen career path, perceiving internal or external barriers to career growth, and having too much or too little career information to empower the individual to make productive decisions (Creed et al., 2015).

To explain this finding, it can be argued that career distress can disrupt the career decision-making process by creating negative emotions and anxiety in individuals. In this regard, Larson et al. (1994) have indicated that career distress includes a wide range of negative feelings such as helplessness, depression, stress, lack of purpose, anxiety, blame, and despair and can be highly debilitating. These feelings can lead to doubts about choosing a job, fear of failure, and lack of self-confidence. As a result, instead of making decisive decisions, the individual avoids choosing and exploring career options. This situation, in turn, causes the individual to remain in a cycle of indecision and confusion and fail to reach a specific career path. Indeed, career distress occurs when an individual is unable to properly manage normal career development tasks (Creed et al., 2015). This type of distress can, in turn, suppress and limit other career development processes, such as career exploration and decision-making, and hinder ongoing career development (Skorikov, 2007). In fact, these two factors (lack of exploration and career planning) are among the mechanisms by which distress impacts career indecision. Career exploration involves self-reflection and environmental exploration and is an important channel for students to acquire career opportunities and resources. Several studies have shown that career exploration helps individuals to increase their knowledge of themselves and the world of work (Cheung & Jin, 2016; Lent et al., 2017), achieve their career goals (Hu et al., 2020), and achieve personal identity (Zikic & Hall, 2009), thereby helping to reduce indecision. Obviously, in the absence of these factors as a result of the creation of distress, the individual’s indecision is exacerbated.

Consistent with the findings of the present study, the findings of other studies such as Nilforooshan (2020), Hamzah et al. (2021), Stead et al. (2021), and Lee and Jung (2022) also indicate a significant correlation between career adaptability (CA) and variables related to the career decision-making domain, including career decision-making self-efficacy (CDMSE). The research of Hirschi et al. (2015) showed that career adaptability has a relationship with career decision-making difficulties and that increased attention to the various dimensions of adaptability predicts fewer decision-making problems. Furthermore, Karacan-Ozdemir (2019) confirmed that higher levels of career adaptability lead to reduced decision-making difficulty. Additionally, Turan & Çelik (2023) showed that career adaptability psycho-educational programs can have a positive impact on facing career indecision and adaptability. To explain this finding, it can be argued that individuals with lower adaptability may have difficulty analyzing and evaluating options due to reduced problem-solving ability and may become confused when faced with changes in the work environment or new conditions and are unable to make effective decisions. Research findings suggest that career decision-making difficulties (e.g., lack of career assessments and lack of career choice) are determinants of career indecision (Phang et al., 2020). Also, the lack of adaptability may create feelings of insecurity and anxiety in individuals, which can in turn disrupt the decision-making process. In line with this, research findings have shown that anxiety is one of the determining factors of career indecision (Şeker, 2020; Priyashantha et al., 2023).

Regarding the mediating role of career adaptability in this study, various studies have examined the mediating role of career adaptability (CA) in the relationship between other variables within the framework of the career construction model of adaptation (Lee & Jung, 2022). For example, Nilforooshan and Salimi (2019) found a mediating effect of career adaptability in the relationship between personality and career engagement. Öztemel and Akyol (2010) also found that CA has a mediating effect on self-esteem and career construction behavior. Chen et al. (2022) proposed career adaptability as a key mediator that can reduce the negative effects of career distress on career decision-making processes. Rudolph et al. (2017) used meta-analysis in their study to examine career adaptability, and the results indicated a mediating role of career adaptability between adaptive ability and adaptive responses, including problems in career decision-making. These findings support the relationship between career adaptability and career decision-making difficulties. Jia et al. (2020), using this theoretical framework, studied the relationship between personality traits (adaptive ability), career adaptability (adaptive resources), and decision-making difficulties (adaptive response). The results showed that career adaptability acts as a mediator between personality traits and decision-making challenges. Therefore, adaptability is essential in facing daily career challenges (Rosier et al., 2012) and is considered a positive personal-psychological resource. According to the results of the present study, an individual who experiences career distress receives a low score on the four components of career adaptability (concern, curiosity, control, and confidence), which causes students to be deprived of the necessary resources to cope with career development tasks, career transitions, individual career planning, career exploration, and career self-efficacy (Parmentier et al., 2021), which in turn increases career indecision (Kin & Ramli, 2020) and reduces career preparation (Creed et al., 2015).

Conclusions

The results showed that the career distress scale is a good psychometric measure for use in a student population. The findings also showed that career distress has both a direct and indirect effect on career indecision in students through career adaptability.

References

- Akkermans, J., Paradniké, K., Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M., & De Vos, A. (2018). The best of both worlds: The role of career adaptability and career competencies in students’ well-being and performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. [CrossRef]

- Akmal, S. Z., Hood, M., & Creed, P. A. (2023). Career distress scale (cds). In C. U. Krägeloh, M. Alyami, & O. N. Medvedev (Eds.), International handbook of behavioral health assessment (pp. 1–13). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Andrich, D. (1978). A rating scale formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika, 43, 561–573. Bagchi, U., & Reddy, K. J. (2023). Current trends in career decision in youth:. [CrossRef]

- Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [CrossRef]

- Bloch, C., Graversen, E., & Pedersen, H. (2014). Competitive research grants and their impact on career performance. Minerva, 52, 77–96. [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (2019). A social cognitive view of career development and guidance. In J. A. Athanasou & H. N. Perera (Eds.), International handbook of career guidance (pp. 147–166). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Browning, M., & Heinesen, E. (2012). Effect of job loss due to plant closure on mortality and hospitalization. Journal of Health Economics, 31 (4), 599–616. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with amos: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Second Edition (2nd ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Chambel, M., & Curral, L. (2005). Stress in academic life: Work characteristics as predictors of student well-being and performance. Applied Psychology, 54, 135–147. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Fang, T., Liu, F., Pang, L., Wen, Y., Chen, S., & Gu, X. (2020). Career adaptability research: A literature review with scientific knowledge mapping in web of science. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (16). [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Pang, L., Liu, F., Fang, T., & Wen, Y. (2022). “be perfect in every respect”: The mediating role of career adaptability in the relationship between perfectionism and career decision-making difficulties of college students. BMC psychology, 10 (1), 137. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R., & Jin, Q. (2016). Impact of a career exploration course on career decision making, adaptability, and relational support in Hong Kong. Journal of Career Assessment, 24(3), 481-496.

- Ching, G. (2021). Academic identity and communities of practice: Narratives of social science academics career decisions in taiwan. Education Sciences, 11, 388. [CrossRef]

- Creed, P. A., & Hughes, T. (2013). Career development strategies as moderators between career compromise and career outcomes in emerging adults. Journal of Career Development, 40(2), 146-163.

- Creed, P. A., Hood, M., Praskova, A., & Makransky, G. (2016). The career distress scale: Using Rasch measurement theory to evaluate a brief measure of career distress. Journal of Career Assessment, 24(4), 732-746.

- Creed, P. A., Hood, M., Praskova, A., & Makransky, G. (2016). The career distress scale: Using Rasch measurement theory to evaluate a brief measure of career distress. Journal of Career Assessment, 24(4), 732-746.

- Creed, P., Hood, M., Praskova, A., & Makransky, G. (2016). The career distress scale: Using rasch measurement theory to evaluate a brief measure of career distress. Journal of Career Assessment, 24, 732–746. [CrossRef]

- Creed, P., Wong, O., & Hood, M. (2009). Career decision-making, career barriers and occupational aspirations in chinese adolescents. International Journal fo educational and Vocational Guidance, 9, 189–203. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, L., Stewart, T., Stupnisky, R., Perry, R., & LoVerso, T. (2011). Relieving career anxiety and indecision: The role of undergraduate students’ perceived control and faculty affiliations. Social Psychology of Education, 14, 409–426. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L., Sgaramella, T. M., Santilli, S., & Di Maggio, I. (2017). Career adaptability and career resilience: The roadmap to work inclusion for individuals experiencing disability. In K. Maree (Ed.), Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience (pp. 415–431). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X., Xin, X., Zhou, W., & Jepsen, D. M. (2019). Combine your “will” and “able”: Career adaptability’s influence on performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, M. C., Di Maggio, I., Santilli, S., Sgaramella, T. M., Nota, L., & Soresi, S. (2018). Career adaptability, resilience, and life satisfaction: A mediational analysis in a sample of parents of children with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 43(4), 473-482.

- Hamzah, S. R. A., Kai Le, K., & Musa, S. N. S. (2021). The mediating role of career decision self-efficacy on the relationship of career emotional intelligence and self-esteem with career adaptability among university students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 26(1), 83-93.

- Hartung, P. J., & Cadaret, M. C. (2017). Career adaptability: Changing self and situation for satisfaction and success. In K. Maree (Ed.), Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience (pp. 15–28). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Hartung, P. J., & Savickas, M. L. (2023). Career adapt-abilities scale (caas). In C. U. Krägeloh, M. Alyami, & O. N. Medvedev (Eds.), International handbook of behavioral health assessment (pp. 1–18). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Hengen, K. M., & Alpers, G. W. (2021). Stress makes the difference: Social stress and social anxiety in decision-making under uncertainty. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S., Hood, M., Creed, P. A., & Shen, X. (2022). The relationship between family socioeconomic status and career outcomes: A life history perspective. Journal of Career Development, 49(3), 600-615.

- Jemini - Gashi, L., Hyseni Duraku, Z., & Kelmendi, K. (2021). Associations between social support, career self-efficacy, and career indecision among youth. Current Psychology, 40, 4691–4697. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y., Hou, Z. J., Zhang, H., & Xiao, Y. (2022). Future time perspective, career adaptability, anxiety, and career decision-making difficulty: Exploring mediations and moderations. Journal of Career Development, 49(2), 282-296.

- Judd, C. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1981). Process analysis: Estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Evaluation Review, 5 (5), 602–619. [CrossRef]

- K. Maree (Ed.), Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience (pp. 65–82). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Karacan-Ozdemir, N. (2019). Associations between career adaptability and career decision-making difficulties among Turkish high school students. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 19, 475-495.

- Katerina, A., Kaliris, A., Charokopaki, A., & Panagiota, K. (2021). Coping with career indecision: The role of courage and future orientation in secondary education students from greek provincial cities, 671–696.

- Kin, L. W., & Rameli, M. M. (2020). Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) personality and career indecision among malaysian undergraduate students of different academic majors. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(5A), 40-45.

- Laditka, J., Laditka, S., Arif, A., & Adeyemi, O. (2023). Psychological distress is more common in some occupations and increases with job tenure: A thirty-seven year panel study in the united states. BMC Psychology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Larson, L. M., Toulouse, A. L., Ngumba, W. E., Fitzpatrick, L. A., & Heppner, P. P. (1994). The development and validation of coping with career indecision. Journal of Career Assessment, 2(2), 91-110.

- Lee, A., & Jung, E. (2022). University students’ career adaptability as a mediator between cognitive emotion regulation and career decision-making self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 896492.

- Lee, W. C. (2004). Validating a model of the career indecision construct: A confirmatory study on three career indecision instruments (Doctoral dissertation, Purdue University).

- Lent, R. W., Ireland, G. W., Penn, L. T., Morris, T. R., & Sappington, R. (2017). Sources of self-efficacy and outcome expectations for career exploration and decision-making: A test of the social cognitive model of career self-management. Journal of vocational behavior, 99, 107-117.

- Lipshits-Braziler, Y., Gati, I., & Tatar, M. (2016). Strategies for coping with career indecision. Journal of Career Assessment, 24 (1), 42–66. [CrossRef]

- Lipshits-Braziler, Y., Gati, I., & Tatar, M. (2016). Strategies for coping with career indecision. Journal of Career Assessment, 24(1), 42-66.

- Mampuru, M., Mokoena, B., & Isabirye, A. (2024). Training and development impact on job satisfaction, loyalty and retention among academics. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 22, e1–e10. [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, L., Amundsen, C., & Turner, G. (2014). Identity-trajectory: Reframing early career academic experience. British Educational Research Journal, 40 (6), 952–969. [CrossRef]

- Milot-Lapointe, F., Savard, R., & Le Corff, Y. (2020). Effect of individual career counseling on psychological distress: Impact of career intervention components, working alliance, and career indecision. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20 (2), 243–262. [CrossRef]

- Müceldili, B., Tatar, B., & Erdil, O. (2023). Career anxiety as a barrier to life satisfaction among undergraduate students: The role of meaning in life and self-efficacy. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Nästesjö, J. (2021). Navigating uncertainty: Early career academics and practices of appraisal devices. Minerva, 59. [CrossRef]

- Nilforooshan, P. (2020). From adaptivity to adaptation: Examining the career construction model of adaptation. The Career Development Quarterly, 68(2), 98-111.

- Nilforooshan, P., & Salimi, S. (2016). Career adaptability as a mediator between personality and career engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 1-10.

- Opoku, E. N., Van Niekerk, L., & Jacobs-Nzuzi Khuabi, L.-A. (2020). Exploring the factors that affect new graduates’ transition from students to health professionals: A systematic integrative review protocol. BMJ Open, 10 (8). [CrossRef]

- Opportunities and challenges. In S. Deb & S. Deb (Eds.), Handbook of youth development: Policies and perspectives from india and beyond (pp. 223–235). Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Öztemel, K., & Akyol, E. Y. (2021). From adaptive readiness to adaptation results: Implementation of student career construction inventory and testing the career construction model of adaptation. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 54-75.

- Parmentier, M., Pirsoul, T., & Nils, F. (2021). Career Adaptability Profiles and Their Relations with Emotional and Decision-Making Correlates among Belgian Undergraduate Students. Journal of Career Development, 1-17.

- Parola, A., & Marcionetti, J. (2024). Profiles of career indecision: A person-centered approach with italian late adolescents. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14 (5), 1437–1450. [CrossRef]

- Patton, W., & Creed, P. (2007). The relationship between career variables and occupational aspirations and expectations for australian high school adolescents. Journal of Career Development, 34, 127–148. [CrossRef]

- Peng, P., Song, Y., & Yu, G. (2021). Cultivating proactive career behavior: The role of career adaptability and job embeddedness. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Phang, A., Fan, W., & Arbona, C. (2020). Secure attachment and career indecision: the mediating role of emotional intelligence. Journal of Career Development, 47(6), 657-670.

- Pordelan, N., Sadeghi, A., Abedi, m. r., & Kaedi, M. (2020). Promoting student career decision-making self-efficacy: An online intervention. Education and Information Technologies, 25, 985–996. [CrossRef]

- Praskova, A., & McPeake, L. (2022). Career goal discrepancy, career distress, and goal adjustment: Testing a dual moderated process model in young adults. Journal of Career Assessment, 30 (4), 615–634. [CrossRef]

- Priyashantha, K. G., Dahanayake, W. E., & Maduwanthi, M. N. (2023). Career indecision: a systematic literature review. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences, 5(2), 79-102.

- Priyashantha, K., Dahanayake, W., & Maduwanthi, M. (2023). Career indecision: A systematic literature review. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences, 5 (2), 79–102. [CrossRef]

- Qazi, W., Qazi, Z., Raza, S. A., Hakim, F., & Khan, K. (2023). Students’ employability confidence in covid-19 pandemic: Role of career anxiety and perceived distress. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 16, 120–133. [CrossRef]

- Rossier, J., Ginevra, M. C., Bollmann, G., & Nota, L. (2017). The importance of career adaptability, career resilience, and employability in designing a successful life. In.

- Rossier, J., Zecca, G., Stauffer, S. D., Maggiori, C., & Dauwalder, J. P. (2012). Career Adaptabilities Scale in a French-speaking Swiss sample: Psychometric properties and relationships to personality and work engagement. Journal of Vocational behavior, 80(3), 734-743.

- Rudolph, C. W., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Career adaptability: A meta-analysis of relationships with measures of adaptivity, adapting responses, and adaptation results. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 98, 17-34.

- Sarsıkoğlu, A. F. (2023). The relationship between time perspective and career decision-making difficulties. Current Psychology, 43, 2544–2554. [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. The Career Development Quarterly, 45 (3), 247–259. [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (2020). Career construction theory and counseling model. In Career development and counseling (pp. 165–199). John Wiley; Sons, Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of vocational behavior, 80(3), 661-673.

- Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J.-P., Duarte, M. E., Guichard, J., Soresi, S., Van Esbroeck, R., & van Vianen, A. E. (2009). Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75 (3), 239–250. [CrossRef]

- Schilbach, M., Baethge, A., & Rigotti, T. (2023). How past work stressors influence psychological well-being in the face of current adversity: Affective reactivity to adversity as an explanatory mechanism. Journal of Business and Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S., Kraimer, M., & Heslin, P. (2016). Developing career resilience and adaptability. Organizational Dynamics, 45, 245–257. [CrossRef]

- Şeker, G. (2020). Well-Being and career anxiety as predictors of career indecision. Pamukkale University Journal of Education, 5(1), 262-275.

- Şensoy, G., & Siyez, D. M. (2019). The career distress scale: structure, concurrent and discriminant validity, and internal reliability in a Turkish sample. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 19, 203-216.

- Sharapova, N., Zholdasbekova, S., Arzymbetova, S., Zaimoglu, O., & Bozshatayeva, G. (2023). Efficacy of school-based career guidance interventions: A review of recent research. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 10, 215–222. [CrossRef]

- Skorikov, V. B. (2007). Adolescent career development and adjustment. In Career development in childhood and adolescence (pp. 237-254). Brill.

- Stead, G. B., LaVeck, L. M., & Hurtado Rua, S. M. (2022). Career adaptability and career decision self-efficacy: Meta-analysis. Journal of Career Development, 49(4), 951-964.

- Sullivan, D., & von Wachter, T. (2009). Job Displacement and Mortality: An Analysis Using Administrative Data*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124 (3), 1265–1306. [CrossRef]

- Toomey, E. (2022). Networking and collaborating in academia: Increasing your scientific impact and having fun in the process. In D. Kwasnicka & A. Y. Lai (Eds.), Survival guide for early career researchers (pp. 89–98). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Turan, M. E., & Çelik, E. (2023). The effect of a career adaptability psycho-educational programme on coping with career indecision and career adaptability: A pilot study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 23(3), 709-717.

- Welch, A. G., Bolin, J., & Reardon, D. (2019). Mid-career faculty: Trends, barriers, and possibilities. Brill.

- Wright, B. D. (1994). Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Meas Transac, 8, 370.

- Xu, H., & Bhang, C. H. (2019). The structure and measurement of career indecision: A critical review. The Career Development Quarterly, 67 (1), 2–20. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Yu, X., & Liu, X. (2022). Do i decide my career? linking career stress, career exploration, and future work self to career planning or indecision. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., ShouChen, Z., & Hong, W. (2024). Impact of multiple job demands on chinese university teachers’ turnover intentions. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Zuo, T., Lai, Y., Zhao, S., & Qu, B. (2021). The associations between coping strategies, psychological health, and career indecision among medical students: A cross-sectional study in china. BMC Medical Education, 21 (1), 334. [CrossRef]

- Zikic, J., & Hall, D. T. (2009). Toward a more complex view of career exploration. The Career Development Quarterly, 58(2), 181-191.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).