1. Introduction

Every year, 15 million people worldwide suffer a stroke, resulting in 5 million deaths and 5 million individuals with significant disabilities for the remainder of their lives [

1]. In 2021, it was estimated that 795,000 people in the United States would experience a stroke, with 85% of cases being ischemic [

2]. The underlying causes of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) are not always easily identified. Nevertheless, the identification of its etiology is crucial for the management of patients, given that it is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality on a global scale. The etiology of AIS is diagnosed based on a combination of analytical and clinical parameters, cardiological testing, and parameters derived from qualitative analysis of radiological images. The TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) criteria were developed to determine the origin of thrombi causing AIS and divides their probable etiology into five different groups: cardioembolic, atherothrombotic, lacunar infarct, unusual origin, and indetermined origin [

3]. Whilst the diagnosis of a lacunar or unusual stroke is relatively straightforward, the classification of an AIS as either a cardioembolic or atherothrombotic event is not always straightforward and is of significant clinical importance. In the context of secondary prevention management, patients with an atheromatous etiology will typically be administered antiplatelet therapy, whereas those with a cardioembolic origin will generally be provided with anticoagulant therapy. In many cases, patients may exhibit features associated with both etiological groups, resulting in an unknown etiology, or an 'indetermined' classification according to the TOAST criteria. This hinders the formulation of effective secondary prevention strategies for these patients.

Furthermore, the molecular composition of a thrombus varies depending on the underlying cause [

5]. Thrombi of atherothrombotic origin contain a greater proportion of red blood cells in comparison to those resulting from other etiologies classified within the TOAST system. In contrast, thrombi of cardiogenic origin exhibit a higher proportion of fibrin and platelets compared to those caused by other factors [

6,

7,

8]. This difference in molecular composition may therefore be a reason for a potentially different radiological behavior of these two types of thrombi. There have been reports of radiological differences between cardioembolic and atherothrombotic thrombi. The thrombi of cardioembolic origin have been shown to exhibit greater density and attenuation on Non-Contrast Computed Tomography. (NCCT) [

9,

10]. This finding indicates that the radiological manifestation of the thrombus is contingent on its molecular composition, and consequently, its origin. Nevertheless, despite the molecular and radiological differences observed, no molecular or radiological criterion related to clots is utilized in the classification of the etiology of acute AIS.

Radiomics is a field of radiology that focuses on the extraction and analysis of a large number of quantitative data from radiological images that correlate with the underlying pathophysiology [

11]. Numerous studies have been conducted on this tool, with a particular focus on oncological pathology. These studies have demonstrated a correlation between radiomic data and various molecular patterns, genetic mutations, and other biological phenomena. However, recent studies using this technique outside oncological settings, particularly for neurologic diseases, have become increasingly common [

12]. Given the established differences in the molecular composition and radiological appearance of thrombi between etiologies of AIS, radiomics may provide further insight into these differences by analyzing quantitative data from images of thrombi. There are already a few recently published articles showing that radiomic data can provide important information to determine the different origin of thrombi in patients with AIS [

13,

14].

The hypothesis of this study is that the different molecular composition of thrombi of atherothrombotic and cardioembolic origin will result in a disparate radiomic pattern of thrombi from these two etiology groups on brain NCCT. This may provide valuable information in determining the etiology of AIS. Therefore, the objective of this article is to employ a machine learning model based on radiomic data obtained from thrombi in NCCT scans of patients with AIS, for the purpose of classifying them as cardioembolic or atherothrombotic etiology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective case-control study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association (2008) and approved by the local Ethics Committee of Santiago-Lugo (code 2023/299). The patients were selected from the database of patients with suspected AIS who were treated at University Hospital of Santiago de Compostela, a public third level hospital, between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2021 (with a total of 882 patients). Informed consent was obtained from each patient after a full explanation of the procedures. All patients received treatment from expert neurologists and neuroradiologists from the Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela (Spain) in accordance with national and international guidelines.

2.2. Patients

The study's inclusion criteria were limited to: (1) patients with AIS caused by thrombi in the internal carotid artery (ICA) and middle cerebral artery (MCA) (M1 and proximal M2 segments); (2) patients with NCCT performed using a slice thickness of less than 1 mm; (3) patients with visible clot on NCCT; and (4) follow-up visits three months after a stroke in living patients. The study's exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) AIS patients who had undergone NCCT and computed tomography angiography (CTA) in a different hospital; (2) patients with AIS resulting from other procedures, such as aneurysmal or tumor embolization; (3) patients with more than one occluded intracranial vessel or tandem occlusion; (4) patients with etiology other than cardioembolic or atherothrombotic according to TOAST criteria; and (5) patients with dual cardioembolic and atherothrombotic etiology according to TOAST criteria; (6) patients suspected of having cardioembolic or atherothrombotic etiology but do not meet the main criteria defined by the TOAST system for each group; and (7) patients with occlusion of the distal middle cerebral artery (M3 or M4 segments).

2.3. Image Adquisition

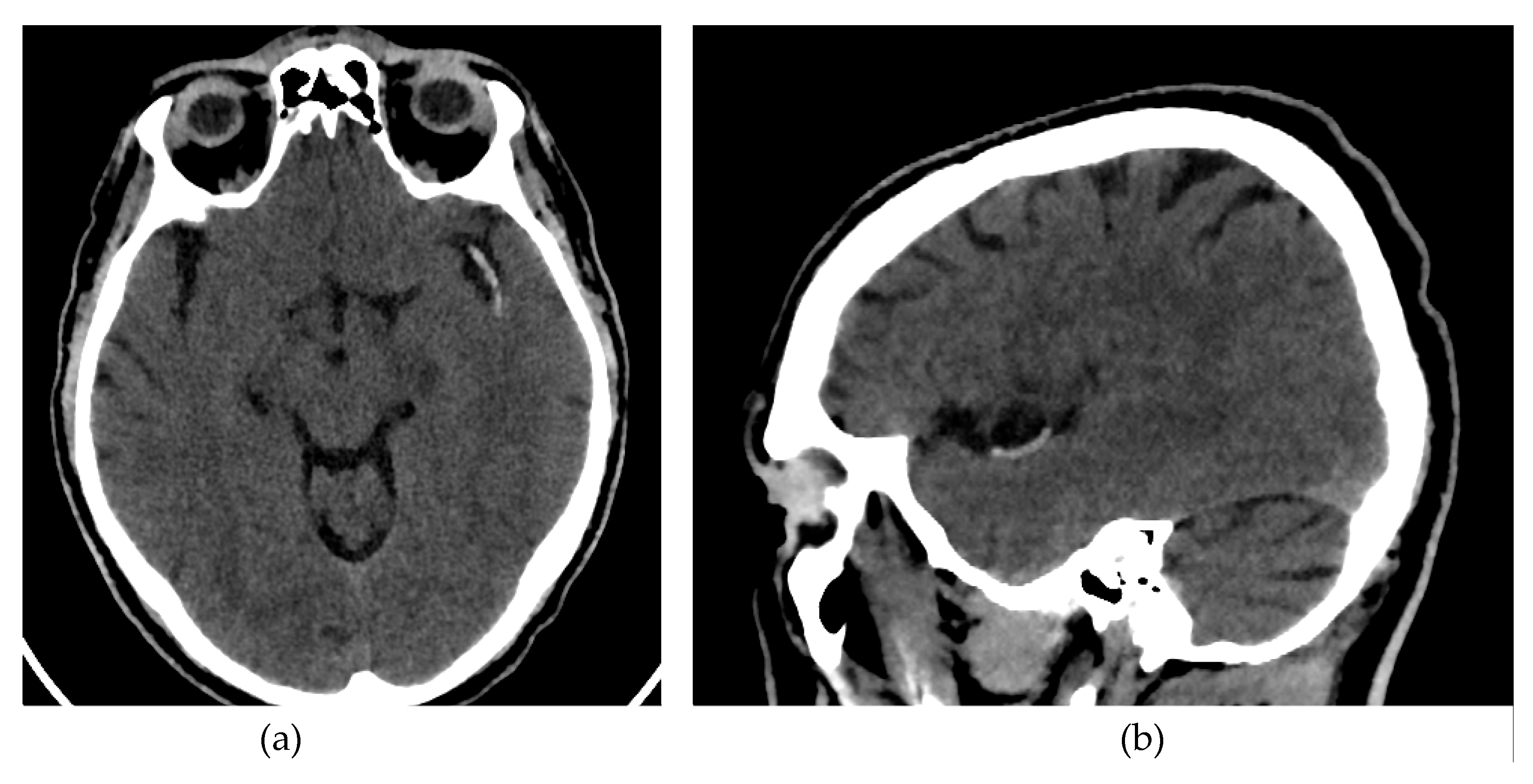

All patients enrolled in the study underwent a NCCT at our hospital using two different CT scanners (16 rows of detectors, 120 kV) of the same make and model (Phillips Ingenuity; Amsterdam, Netherlands) during the diagnosis process of AIS. Patients were randomly assigned to each scanner. The images obtained had a slice thickness of 0.625 mm. Although reconstructions with a thickness of 1 mm were available, they were not used for analysis. The window width and center were set at 80 and 40 Hounsfield units, respectively (

Figure 1).

2.4. Segmentation, Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

Two interventional neuroradiologists and a radiology resident who had undergone specialized training performed semi-automated segmentation of each thrombus. The segmentation was conducted using the open-access software 3D Slicer (version 5.2.2, Massachusetts, USA) [

17]

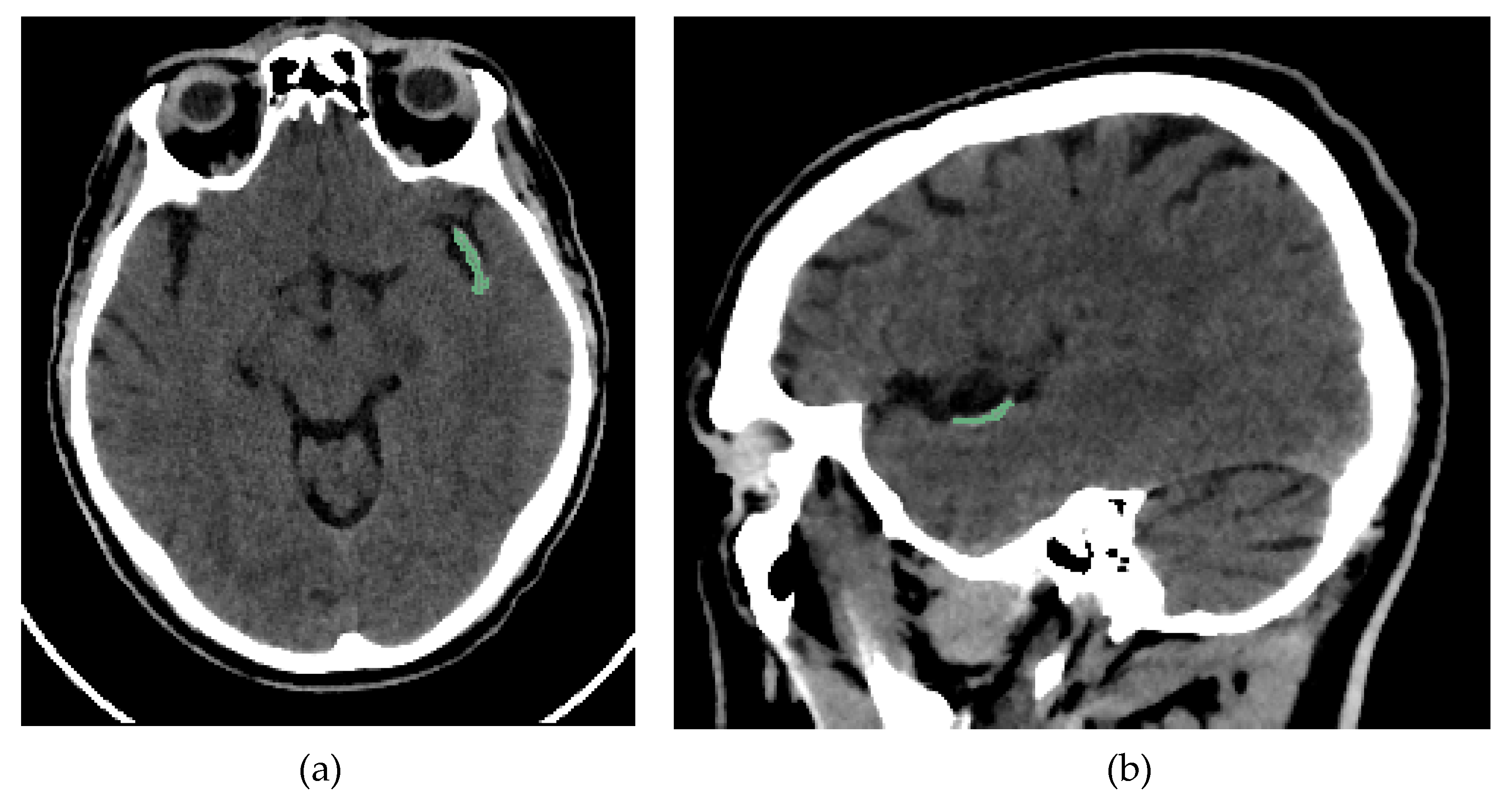

. The software includes a segmentation tool (Level Tracing tool) that enables semi-automatic segmentation based on automatic edge detection. The region of interest segmented was the clot visible on NCCT in patients with AIS (

Figure 2). Segmentation was performed in all three spatial planes (

Figure 3). The window width and center were set to 100 and 50 HU, respectively.

Radiomic features were obtained using the Slicer Radiomics tool, which is also available in 3D-Slicer [

18]. This application uses the computational classes implemented in the Pyradiomics library. During the feature extraction process, 3D-Slicer allows image voxel resampling and kernel size modification. These parameters were not modified. Conversely, the images were normalized by smoothing with a Gaussian filter and a fixed value of 25 for the grey bin width, and wavelet-based features were also extracted. The complete set of features available in 3D Slicer was extracted, encompassing the following: first order, GLCM, GLDM, GLRLM, GLSZM, NGTDM, and shape-based features. A total of 32,110 RF were obtained, with 845 RF for each patient included in the study.

The radiomics quality score (RQS) was developed to measure the quality of radiomic studies [

15]. Our study received a score of 19 out of 36 (52.78%) (

Appendix A). Furthermore, the preparation of this article adheres to the CheckList for EvaluAtion of Radiomics research (CLEAR) guidelines [

16] (see supplemental materials).

The segmentation, extraction of RF, and analysis of the results were performed using a system with an Intel CORE i7 processor (Santa Clara, California, USA), 16 GB RAM, 1 TB hard disk, and Microsoft Windows 11 operating system (Redmond, Washington, USA).

2.5. Clinical Data

The study also recorded the median Hounsfield units (HU) of the clot for each etiological group. Other clinical data were also recorded, including age, gender, the presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, alcohol and drug use, and smoking. In addition to these data, information is available on the tPA administration, the laterality of the thrombus, the ASPECTS score and the degree of collaterality following the ASITN/SIR collateral grading scale [

19]. The patient's condition is measured before and after treatment using the modified Ranking Scale (mRS) and NIHSS scale.

2.6. Stadistical Analysis

The RF selection and the analysis of RF and clinical variables was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics (SPSS) (version 21., IBM. Armonk, New York, EEUU) [

20]. Firstly, a multivariate analysis was conducted, employing a logistic regression model to ascertain the variables associated with the two etiologies of AIS, with a 95% confidence interval. The multivariate analysis incorporated 845 RFs and 9 clinical variables (age; gender; arterial hypertension; drug, alcohol or smoke consumption; diabetes; dyslipidemia and Hounsfield units). In order to select significant variables, the p-value must fall below 0.05. With regard to the remaining clinical data, the administration of tPA was not considered due to its occurrence subsequent to the NCCT procedure, thereby rendering the radiomic data antecedent to this administration. The ASPECTS score and the patient's functional status were not considered in the analysis due to the fact that the focus of the segmentation is exclusively on the thrombus, excluding the brain parenchyma.

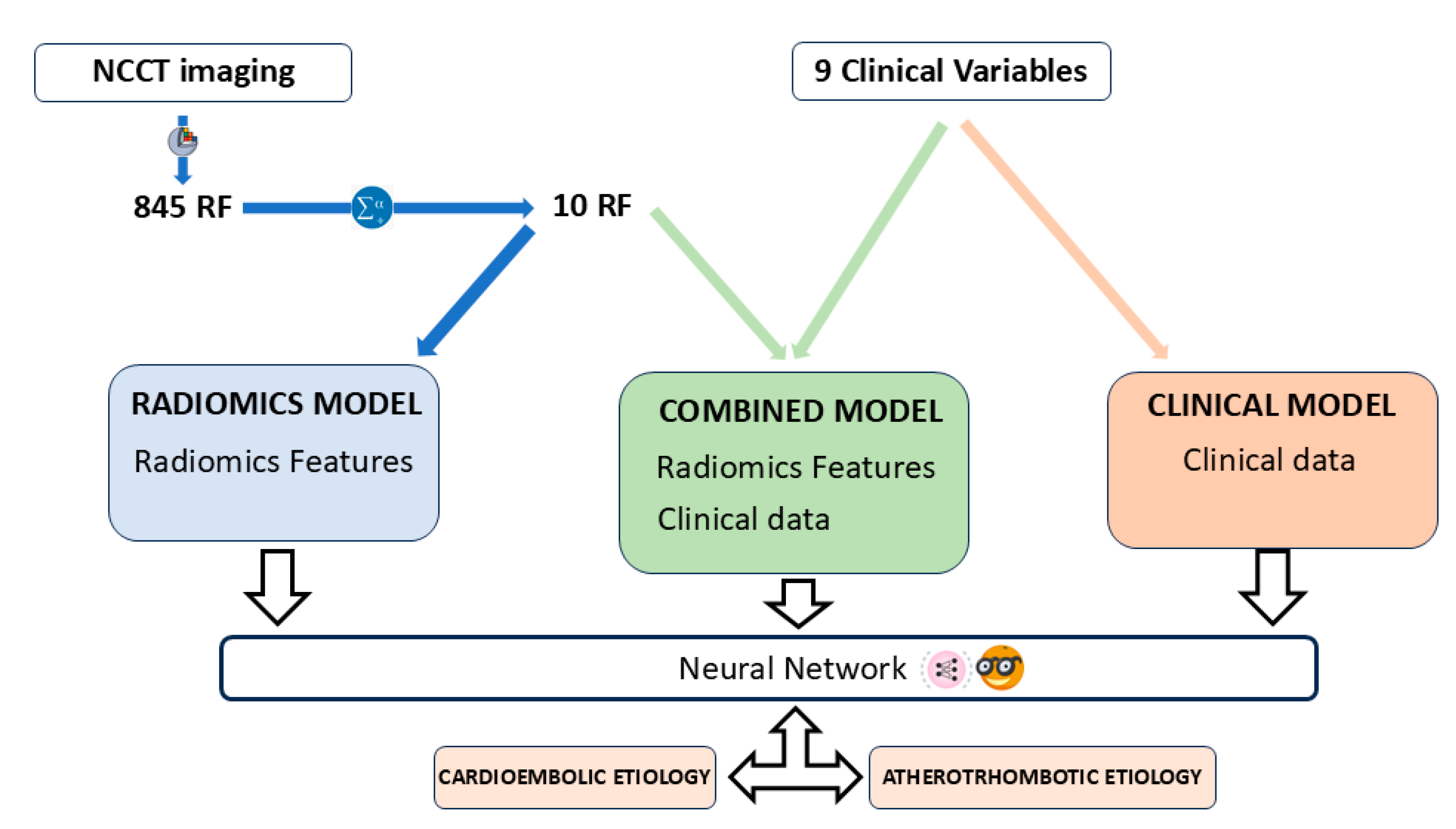

The predictive models were constructed with the open access software Orange: Data Mining Toolbox in Python (version 3.33.0, Ljubljana, Slovenia) [

21]. A total of three predictive models were constructed, namely: (i) a Radiomics model, based on the RF that emerged as the most statistically significant according to the multivariate analysis; (ii) a clinical model, comprising solely clinical variables; and (iii) a combined model that incorporated both the selected RF and the clinical variables (

Figure 4). The automatic classifier utilized was Neural Network, a multi-layer perception algorithm also available from Orange Data Mining [

22,

23]. The Orange software suite facilitates the modification of parameters associated with Neural Networks classifier. The configuration parameters for the classifier are as follows: 100 neurons per hidden layer, the ReLu activation function for the hidden layer, a stochastic gradient-based optimizer (Adam) for weight optimization, and 200 maximal iterations.

The Orange application employed for the evaluation of the performance of the classification model is "Test and Score". Test and Score permits the implementation of diverse sampling methodologies. In this instance, the sampling method that was employed was leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV). The LOOCV method selects

n-1 patients for the training group, with the remaining patient being allocated to the test group. This process is repeated

n times, with a different patient being assigned to the test group on each occasion. LOOCV method is particularly recommended for evaluating the performance of machine learning models, when the number of datasets is limited [

24]. Test and Score also permits the observation of the classifier performance measures. The classification accuracy and area under the curve (AUC) of the predictive models were calculated with this application. In addition to the aforementioned functionality, the application facilitates the integration of supplementary widgets, including "confusion matrix" widget, which serves to provide a visual representation of the confusion matrix of the classifiers, and "box plot" widget, which quantifies the concordance between the classifier results and the actual classification by employing a chi-square test and a 95% confidence interval.

The classifier´s performance in the three models is measured using the Cohen's kappa coefficient (K), the AUC, the Accuracy, the sensitivity (Se) and the specificity (Sp), with a 95% confidence interval. The Kappa coefficient is a statistical measure of the extent to which the true and predicted categories are aligned, excluding the possibility of agreement by chance. Its value is more conservative and statistically more valid than the balanced accuracy or AUC. The confusion matrix is a graphical representation of the relationship between the predictions made by Neural Networks (represented by the columns of the matrix) and the TOAST criteria-based classification (represented by the rows of the matrix) (

Table 1). The true positive (TP) is defined as the number of atherothrombotic AIS patients correctly identified as such. The false positive (FP) is defined as the number of atherothrombotic AIS patients incorrectly identified as cardioembolic AIS patients. The true negative (TN) is defined as the number of cardioembolic AIS patients correctly identified as such. Finally, the false negative (FN) is defined as the number of cardioembolic AIS patients incorrectly identified as atherothrombotic AIS patients.

The Kappa coefficient (in %) is defined for classification problems with two categories, in our case Atherothrombotic AIS and Cardioembolic AIS, as

were and . The Se is defined as the classifier's ability to correctly detect patients with atherothrombotic AIS, while the Sp is defined as the classifier's ability to correctly detect patients with cardioembolic AIS. The Se, Sp and Accuracy are defined by

3. Results

3.1. Patient Selection

Out of 882 patients, only 41 were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. These patients were divided into two groups using the TOAST system: cardioembolic (29 patients) and atherothrombotic (12 patients) etiology (

Table 2).

3.2. Feature Reduction

In the multivariate analysis performed with SPSS, of the 845 RFs extracted, only 10 were statistically significantly associated with cardioembolic and atherothrombotic etiology of AIS (p-value < 0.05) (

Table 3). The features that were selected for inclusion in the study included one shape feature (Sphericity) and 9 texture features: 4 Gray Level Dependence Matrix (GLDM), 2 Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), 2 Gray-Level Run Length Matrix (GLRLM) and 1 Neighborhood Gray Tone Difference Matrix (NGTDM). The shape features describe morphological aspects of the region of interest. The GLDM features are responsible for determining the dependency of voxels in a given neighborhood on a single center voxel. The GLCM features calculate the frequency with which adjacent pixels of each grey level value co-occur. The GRLM features are metrics that quantify the number of lines of a specific grey level and length that occur in a given direction. Finally, The NGTDM features are metrics which analyze the difference between the grey value of a pixel and that of its immediate vicinity [

25].

Of the clinical variables included in the multivariate analysis, none were shown to have a statistically significant association with the cardioembolic and atherothrombotic etiology of AIS (p-value > 0.05) (

Table 4).

3.3. Prediction Models

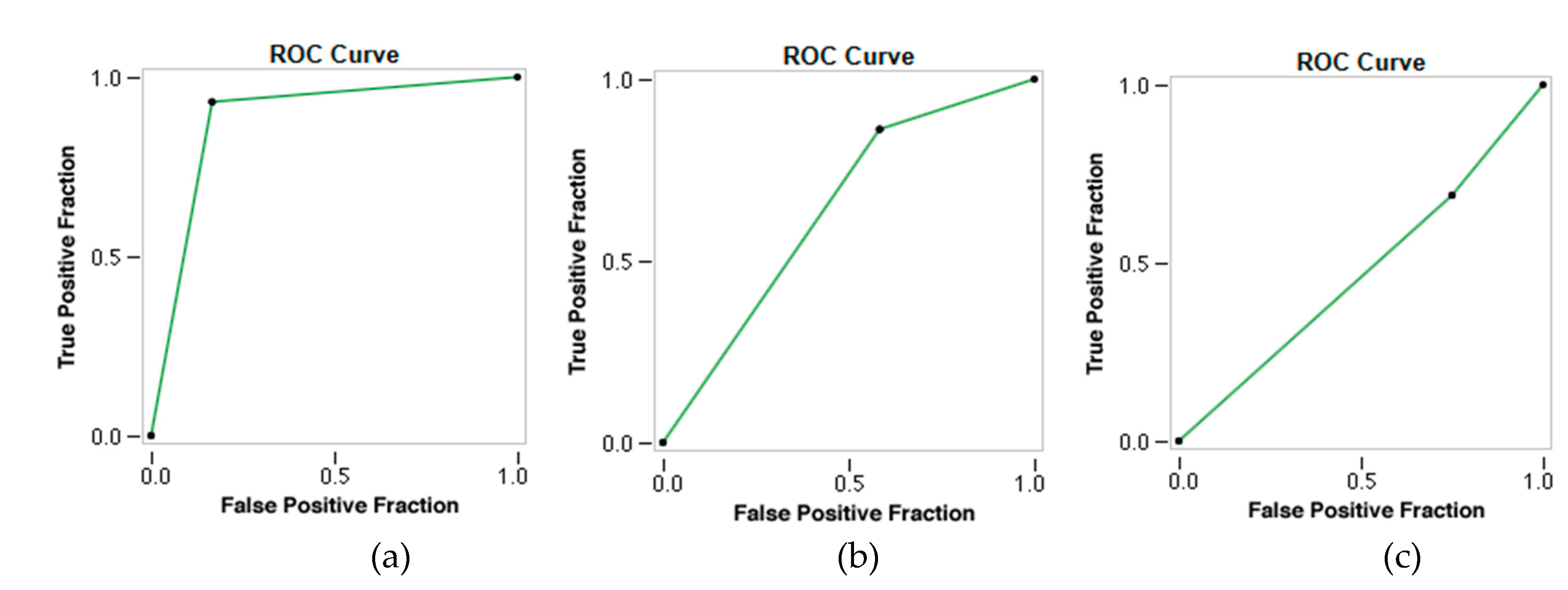

The radiomic model demonstrated the capacity to differentiate between the two types of thrombi and accurately predict the patients' cardioembolic and atherothrombotic etiology of AIS. The accuracy, AUC, Se and Sp for predicting stroke etiology were 0.902, 0.842, 0.833 and 0.931 respectively (p-value 0.000), with Kappa = 76.43%.

However, when the RF and the clinical variables (combined model) was employed, the accuracy, AUC, Se and Sp for predicting stroke etiology decreased to 0.732, 0.655, 0.556 and 0.781 respectively (p-value 0.040), with a Kappa = 30.07%.

The clinical model showed the worst performance in predicting the etiology of AIS, with statistically non-significant results, with an accuracy of 0.561, an AUC of 0.402, a Se of 0.300 and a Sp of 0.710 (p-value 0.993), with a Kappa = -6.03%.

Table 6.

The following confusion matrix illustrates the performance of the combined model (utilizing RF and clinical variables) with the automatic classifier Neural Network.

Table 6.

The following confusion matrix illustrates the performance of the combined model (utilizing RF and clinical variables) with the automatic classifier Neural Network.

| |

|

Neural Network (Combined Model) |

∑ |

| |

|

Atherothrombotic |

Cardioembolic |

|

| TOAST |

Atherothrombotic |

5 |

7 |

12 |

| Cardioembolic |

4 |

25 |

29 |

| ∑ |

|

9 |

32 |

|

Table 7.

Confusion matrix of clinical model (utilizing only clinical variables), also with the automatic classifier Neural Network.

Table 7.

Confusion matrix of clinical model (utilizing only clinical variables), also with the automatic classifier Neural Network.

| |

|

Predicted with Neural Network |

∑ |

| |

|

Atherothrombotic |

Cardioembolic |

|

| TOAST |

Atherothrombotic |

3 |

9 |

12 |

| Cardioembolic |

9 |

20 |

29 |

| ∑ |

|

12 |

29 |

|

4. Discussion

The present study has demonstrated the capacity of radiomics to differentiate between cardioembolic and atherothrombotic thrombi. The molecular differences between these two types of clots also reflect a difference in imaging representation, thus establishing a correlation between the RF of NCCT images and the atherothrombotic and cardioembolic etiology of AIS. A total of 845 RFs were analyzed; however, only a subset of 10 RFs that were statistically associated with these two etiological groups (p<0.05) were selected for further investigation. Multivariate analysis revealed no statistically significant association between these two etiologies of AIS and the clinical variables investigated, including clot density, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking, alcoholism, drug use, age and sex (p-value > 0.05). Three predictive models were developed: one based on RF alone, one based on clinical variables alone, and a third model based on the combination of RF with clinical variables. An automatic classifier based on neural networks (Neural Network) has been used. The radiomic model performed very well, with an AUC of 0.842, an accuracy of 0.902, a Se of 0.833 and an Sp of 0.931. The model's performance, as measured by Cohen's Kappa index (K = 76.43%), demonstrated substantial agreement with the TOAST criteria, which are recognized as the gold standard for the etiological classification of AIS. However, when clinical variables were introduced into the model, its predictive performance was found to deteriorate, with the clinical model demonstrating the most unfavorable outcomes.

The present findings are consistent with those reported in two other articles published on the subject of the prediction of the etiology of AIS. Chen et al. obtained an AUC of 0.9018 and an accuracy of 0.8929 in differentiating between cardioembolic and atherothrombotic etiology using radiomic features based on CTA images [

13]. The most notable difference between the two studies is the source of the radiomic data. In the present work, the radiomic data are obtained from the NCCT, while in the referenced article they are obtained from the CTA. A further distinction between our work and the referenced article is that we perform a semi-automatic segmentation, while they employed a manual segmentation. The semi-automated segmentation performed is based on automatic edge detection, with the radiologist responsible for ensuring that the segmentation includes as much of the thrombus area as possible. In patients with arterial clot visible on NCCT, the contrast between the region of interest and the rest of the brain parenchyma is sufficiently remarkable to be easily detected by the automatic edge detection method, with the radiologist only intervening to accept or correct the segmentation performed. This made the segmentation faster and included the entire thrombi. Finally, the aforementioned article does not incorporate clinical variables within the radiomic analysis, in contrast to the approach employed in the present article.

Regarding the other published article, Jiang J et al. obtained an AUC of 0.838 in predicting the cardioembolic etiology of AIS in a sample of 403 patients, also using manual segmentation. They used NCCT-based radiomic features of AIS patients [

14]. As far as this article is concerned, the main difference lies in the fact that in our case we are trying to predict both etiological atherothrombotic and cardioembolic groups, instead of limiting ourselves to predicting only one of them. The segmentation process is also manual, as described by Chen et al. Furthermore, this article makes no mention of clinical variables in the context of radiomic analysis. On the other hand, the images used in this case are also from NCCT, which also gives good results in predicting the cardioembolic group, supporting our findings that there is a correlation between the radiomic data obtained from NCCT and the etiology of thromboembolic events in patients with AIS. Therefore, this article also concluded that radiomics could be helpful in determining the etiology of AIS.

Regarding the limitations of our study, the first one is that it is a retrospective study. In this regard, since there is not much literature available, we believe that the first step to investigate whether radiomics can contribute something to the diagnosis of the etiology of AIS is to perform a retrospective study, as it is the one that involves the least ethical conflicts, as well as not delaying or altering the usual management of these patients. Having shown that the association appears to exist with a retrospective study, we believe that the next step is to confirm these findings with a prospective study. Another classic limitation of radiomic studies is external validity. In our case, images from two different CT scanners of the same make and model were used. In this sense, it is necessary to include images from scanners of different manufacturers and from other hospitals to increase the external validity of these studies. For this reason, we believe that multicenter studies are also needed, because single-center studies seem to show that such an association exists. Finally, another limitation of radiomic studies is the difference in methodology between study groups in data processing and analysis of radiomic variables. In this case, it is necessary to publish in detail the steps carried out in order to increase the available bibliography in this field and to share methodologies that can be reproduced by other research groups, with the aim of unifying the analytical processes as much as possible. In terms of specific limitations of our study, it is important to note that we had a lower number of subjects in comparison to previous studies. In our case, in addition to a significantly shorter recruitment period, the fact that only patients with clot visible on NCCT and pure occlusion of the distal ICA or proximal branches of the MCA were selected meant that the N was not higher. With this in mind, a sampling method recommended for low N studies was used (LOOCV). Further patient recruitment is needed to increase the sample size and to include other patient groups not analyzed in the current article.

Determining the etiology of AIS is crucial for effective therapeutic management and early implementation of appropriate secondary prevention measures [

26]. The classification of a stroke as lacunar or of infrequent etiology using the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) criteria is well protocolized. However, in cases of cardioembolic and atherothrombotic etiology, the boundaries may be less clearly defined, resulting in a significant number of patients being labelled as having an 'undetermined etiology'. In other cases, the information for etiology determination is only available after the acute onset of stroke, leading to delayed identification of the cause of AIS. The intention of this study to utilize radiomics in order to provide additional information which will assist in the classification of patients who meet the criteria for both etiological groups, or whose etiology has been incompletely studied (classified as “indetermined” according to the TOAST criteria). However, thrombi of atherothrombotic and cardioembolic origin exhibit divergent molecular compositions [

5,

6,

7,

8], yet this specific molecular data remains inaccessible in the acute care setting for these patients. Conversely, radiomic data derived from NCCT is obtainable early in the management of AIS patients. The present study makes a significant contribution to the extant literature by demonstrating that radiomics also has the capacity to differentiate thrombi of atherothrombotic origin from those of cardioembolic origin. These findings may assist in the timely and accurate diagnosis of the etiology of stroke in such patients.

In summary, the present article confirms the hypothesis that molecular differences between thrombi of cardioembolic and atherothrombotic origin also translate into radiomic differences between these two etiology groups. This provides significant data that may facilitate the classification of the etiology of AIS.

5. Conclusions

Radiomic features can help classify patients with AIS into cardioembolic or atherothrombotic etiology, with consequent benefit in patient management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. The CheckList for EvaluAtion of Radiomics research (CLEAR) guidelines are attached as supplementary material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.A., A.J.M.M., J.M.F. and M.S.B.; methodology, J.P.A. and A.J.M.M.; software, J.P.A. and A.J.M.M.; validation, A.J.M.M., J.M.F., M.B.U., R.G.F., M.S., E.R.C. and M.S.B.; formal analysis, M.B.U., R.I.R., P.H.L., R.G.F. and M.S.B.; investigation, J.P.A., A.J.M.M. and M.S.B.; resources, M.S., E.R.C., R.G.F. and M.S.B.; data curation, J.P.A. and A.J.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.A., A.J.M.M. and P.V.P.; writing—review and editing, J.M.F., J.L.T.A., M.B.U., M.S., E.R.C., R.I.R., P.H.L., R.G.F. and M.S.B.; visualization, J.M.P. and M.T.M.; supervision, A.J.M.M., R.G.F., M.S.B.; project administration, A.J.M.M.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Santiago-Lugo (protocol code 2023/299; approved 31/05/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Spanish Society of Neuroradiology (SENr). In addition, we would like to acknowledge the training provided by Dr Eva Cernadas (Centro Singular de Investigación en Tecnoloxías Intelixentes da USC [CiTIUS], Universidade de Santiago de Compostela; eva.cernadas@usc.es), Dr Manuel Fernández Delgado (Centro Singular de Investigación en Tecnoloxías Intelixentes da USC [CiTIUS], Universidade de Santiago de Compostela; manuel.fernandez.delgado@usc.es) and Dr Víctor González-Castro (Department of Electrical, Systems and Automation Engineering, Universidad de León; victor.gonzalez@unileon.es).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIS |

Acute Ischemic Stroke |

| AUC |

Area Under Curve |

| ASITN/SIR |

American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology/Society of Interventional Radiology |

| ASPECTS |

Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| CTA |

Computed Tomography Angiography |

| FN |

False Negative |

| FP |

False Positive |

| GLCM |

Gray-Level Cooccurrence Matrix |

| GLDM |

Gray-Level Dependence Matrix |

| GLRLM |

Gray-Level Run Length Matrix |

| GLSZM |

Gray-Level Size Zone Matrix |

| HU |

Hounsfield Units |

| ICA |

Interna Cerebral Artery |

| K |

Cohen´s Kappa index |

| LOOCV |

Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation |

| MCA |

Middle Cerebral Artery |

| mRS |

modified Ranking Scale |

| NCCT |

Non-Contrast Computed Tomography |

| NGTDM |

Neighborhood Gray Tone Difference Matrix |

| NIHSS |

National Institute of Health Stroke Scale |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

| RF |

Radiomics Features |

| RQS |

Radiomics Quality Score |

| Se |

Sensitivity |

| Spe |

Specificity |

| TOAST |

Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment |

| TN |

True Negative |

| TP |

True Positive |

| tPA |

tissue Plasminogen Activator |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Radiomics Quality Score (RQS)

| Questions |

Answers |

| Image protocol quality |

Protocols well documented and public |

| Multiple segmentations |

Yes |

| Phantom study |

No |

| Imaging at multiple time points |

No |

| Feature reduction |

Either measure is implemented |

| Multivariable analysis with non-RFs |

Yes |

| Detect and discuss biological correlates |

Yes |

| Cut-off analyses |

No |

| Discrimination statistics |

Discrimination statistic and its significance

Resampling method applied |

| Calibration statistics |

Calibration statistic and its significance

Resampling method applied |

| Prospective study |

No |

| Validation |

Validation on dataset of same institute |

| Comparison to “gold standard” |

Yes |

| Potential clinical utility |

Yes |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis |

No |

| Open science and data |

The code is open sourced |

| Total Score |

19 (52.78%) |

References

- World Health Organization. Stroke, Cerebrovascular accident. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/stroke-cerebrovascular-accident/introduction.html (accessed on 08 February 2024).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Stroke Facts. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm (accessed on 08 February 2024).

- Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35-41. [CrossRef]

- Staessens S, François O, Brinjikji W, et al. Studying Stroke Thrombus Composition After Thrombectomy: What Can We Learn? Stroke. 2021;52(11):3718-3727. [CrossRef]

- Joundi RA, Menon BK. Thrombus Composition, Imaging, and Outcome Prediction in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neurology. 2021 Nov 16;97(20 Suppl 2):S68-S78. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald S, Rossi R, Mereuta OM, et al. Per-pass analysis of acute ischemic stroke clots: impact of stroke etiology on extracted clot area and histological composition. J Neurointerv Surg. 2021;13(12):1111-1116. [CrossRef]

- Jabrah D, Rossi R, Molina S, et al. White blood cell subtypes and neutrophil extracellular traps content as biomarkers for stroke etiology in acute ischemic stroke clots retrieved by mechanical thrombectomy. Thromb Res. 2024;234:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Hund HM, Boodt N, Hansen D, et al. MR CLEAN Registry Investigators. Association between thrombus composition and stroke etiology in the MR CLEAN Registry biobank. Neuroradiology. 2023;65(5):933-943. [CrossRef]

- Schartz D, Akkipeddi SMK, Chittaranjan S, et al. CT hyperdense cerebral artery sign reflects distinct proteomic composition in acute ischemic stroke thrombus. J Neurointerv Surg. 2023;15(12):1264-1268. [CrossRef]

- Boodt N, Compagne KCJ, Dutra BG, et al. Coinvestigators MR CLEAN Registry. Stroke Etiology and Thrombus Computed Tomography Characteristics in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A MR CLEAN Registry Substudy. Stroke. 2020;51(6):1727-1735. [CrossRef]

- Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology. 2016;278(2):563–77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porto-Álvarez, J.; Mosqueira, A.; Martínez Fernández, J.; et al. How Can Radiomics Help the Clinical Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke? Appl. Sci. 2023;13;10061. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, He Y, Jiang Z, et al. Ischemic stroke subtyping method combining convolutional neural network and radiomics. J Xray Sci Technol. 2023;31(2):223-235. [CrossRef]

- Jiang J, Wei J, Zhu Y, et al. Clot-based radiomics model for cardioembolic stroke prediction with CT imaging before recanalization: a multicenter study. Eur Radiol. 2023;33(2):970-980. [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P. , Leijenaar, R., Deist, T. et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, B. , Baessler, B., Bakas, S. et al. CheckList for EvaluAtion of Radiomics research (CLEAR): a step-by-step reporting guideline for authors and reviewers endorsed by ESR and EuSoMII. Insights Imaging, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(9):1323-41. [CrossRef]

- van Griethuysen JJM, Fedorov A, Parmar C, et al. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):e104-e107. [CrossRef]

- Guo B, Moga C, Tjosvold L. Technological Safety and Effectiveness. In: Endovascular Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke [Internet]. Edmonton (AB): Institute of Health Economics; 2017 Aug. TABLE T.2, ASITN/SIR collateral grading scale. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549072/table/sectionthree.

- IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. I: Armonk, NY.

- Demsar J, Curk T, Erjavec A, et al. Orange: Data Mining Toolbox in Python, Journal of Machine Learning Research 2013;14:2349−2353. http://jmlr.org/papers/v14/demsar13a.

- Neural networks models (supervised). Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/neural_networks_supervised.html (accessed on 30 Dec 2024).

- Manuel Fernández-Delgado, Eva Cernadas, Senén Barro, et al. Do we need hundreds of classifiers to solve real world classification problems? J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014;15(1):3133–3181. [CrossRef]

- LOOCV for Evaluating Machine Learning Algorithms. Available online: https://machinelearningmastery.com/loocv-for-evaluating-machine-learning-algorithms/#:~:text=The%20Leave-One-Out%20Cross-Validation%2C%20or%20LOOCV%2C%20procedure%20is%20used,on%20data%20not%20used%20to%20train%20the%20model (accessed on 06 Jan 2025).

- Radiomics Features. Avaliable online: https://worc.readthedocs.io/en/latest/static/features.html (accessed on 04 Jan 2025). (accessed on 04 Jan 2025).

- Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021;52(7):e364-e467. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).